Abstract

Natural biodegradable polymers such as chitosan are gaining increasing importance due to their favorable mechanical properties. Conversely, their limited antimicrobial and antioxidant activity requires enhancement with bioactive components. This study investigated the effect of Teucrium montanum L. hydrolate on the functional properties of chitosan films. The hydrolate was obtained as a by-product of hydrodistillation, and films were prepared with 0.6% (CH-TMh1), 0.8% (CH-TMh2), and 1.2% (CH-TMh3) hydrolate, along with a control film without hydrolate (CH). Hydrolate-enriched films exhibited greater thickness and elongation at break, with the highest values observed in CH-TMh3. The addition of hydrolate reduced moisture content (from 30.09% in CH to 12.25% in CH-TMh3), solubility, and swelling degree. Antioxidant activity increased significantly, with CH-TMh2 showing the highest free radical scavenging activity (92.9%) and total polyphenol content (38.78 mg GAE/g). Films containing hydrolate also displayed pronounced antimicrobial activity, with the largest inhibition zones against S. aureus ATCC 25923 (16.33 mm). Moderate activity was observed against B. subtilis, while there was no activity against C. albicans ATCC 2091. These results confirm that chitosan films enriched with T. montanum L. hydrolate possess improved mechanical, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties, making them promising for potential application in the packaging of specific food products.

1. Introduction

Food packaging plays a key role in preserving the freshness, quality, and safety of products, protecting them from harmful physical, chemical, and microbiological influences during storage, transport, and distribution. Modern packaging solutions enable the global distribution of food, extending its shelf life and availability to consumers across different geographical locations [1,2]. Although conventional packaging materials, most often plastic derived from fossil sources, successfully meet the technical requirements for product preservation, their low biodegradability and negative impact on the environment represent a significant ecological concern [3]. In response to these challenges, recent research has increasingly focused on biodegradable materials of plant and animal origin, which are being developed as sustainable alternatives to traditional plastic materials. In this context, biodegradable films and coatings based on natural polymers, such as polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids, represent environmentally friendly solutions for primary food packaging [4].

Among natural polymers, chitosan stands out due to its exceptional physicochemical and biological properties, including non-toxicity, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and the ability to form flexible, elastic films with antimicrobial activity [4]. Chitosan is a natural aminopolysaccharide obtained by the deacetylation of chitin, a compound present in the exoskeletons of crustaceans and insects [5]. Structurally, chitosan is composed of glucosamine, 2-amino-2-deoxy-β–D-glucose, or (1-4)-2-amino-2-deoxy-D-glucose [6]. Chitosan based films show potential for application in food packaging, but due to limited antioxidant and bacteriostatic properties, they are not effective enough in preventing oxidation and microbiological spoilage [4]. To enhance the functional properties of chitosan films, they are often enriched with natural bioactive components. For example, Bajić et al. [7] used plant extracts of hops and oak, while Gradinaru et al. [8] incorporated sage and St. John’s wort extracts.

Mountain germander (Teucrium montanum L.) has traditionally been used in folk medicine due to its pronounced antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties. This plant is rich in phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and sesquiterpenes, which contribute to its biological activity confirmed by modern chemical analysis methods [9,10]. The plant’s high antimicrobial activity is often attributed to the presence of sesquiterpenes, such as δ-cadinene and α-selinene, while phenolic acids and flavonoids further contribute to its antioxidant properties. Additionally, phenolic compounds in methanolic extracts of Teucrium montanum L. have demonstrated antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects [11].

Hydrolates offer several process-level advantages over extracts and essential oils: (a) no organic solvents are required, reducing purification steps and environmental burden; (b) hydrolates are by-products of essential oil distillation, contributing to waste valorization; (c) they are water-based systems, ensuring better compatibility with hydrophilic polymer matrices such as chitosan, without emulsifiers; and (d) hydrolates allow direct incorporation into aqueous film-forming solutions, simplifying scale-up and reducing energy input.

The aim of this research was to evaluate the effect of Teucrium montanum L. hydrolate, a water-based by-product of essential oil distillation, on the functional properties of chitosan-based films, with emphasis on its potential for sustainable material development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The plant material is the same as used in the research of Sailović et al., [10]. It was collected on the Ozren mountain (Bosnia and Herzegovina) in 2020, identified based on morphological characteristics (Svjetlana Zeljković) and dried in the shadow. Dried material was stored in a cool and dark place until use [10].

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

The following chemicals and reagents were used in this study: chitosan with a molecular weigth (Mw) of 100,000–300,000 g/mol (Janssen Pharmaceuticalaan, Geel, Belgium), lactic acid with a molecular weight (Mw) of 90.08 g/mol (CentroHem, Stara Pazova, Serbia), glycerol (Zorkapharm, Šabac, Serbia), ethanol (SaniHem, Novi Sad, Serbia), DPPH solution (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), sodium carbonate solution (Na2CO3), (Zdravlje, Leskovac, Serbia), nutrient agar and Sabouraud maltose agar (Torlak, Belgrade, Serbia).

2.3. Preparation of Plant Extract

The hydrolate of Teucrium montanum L., was initially prepared and analyzed in the study by Sailović and colleagues [10]. Subsequently, it was used as an additive in chitosan films for further evaluation and testing. The hydrolate was obtained as a by-product of essential oil isolation through hydrodistillation using a Clevenger-type apparatus. The hydrolate was subsequently separated by filtration and evaporated to dryness. An aqueous solution of the dried hydrolate was prepared at a concentration of 200 mg/mL, which was further used for film preparation.

2.4. Preparation of Films

Films were prepared on a laboratory level according to the method previously described [12]. Briefly, 1.5% chitosan solution (3 g) (Janssen Pharmaceuticalaan, Geel, Belgium) was prepared by dissolving in 1% lactic acid (190 mL). Subsequently, 1 mL of 85% glycerol, (Zorkapharm, Šabac, Serbia) was added to 190 mL of the solution, and the mixture was stirred for 15 min on a magnetic stirrer (SCILOGEX SCI280-Pro, Rocky Hill, CT, USA) at 50 °C and 500 rpm. The prepared solution was divided into four portions of 45 mL each, and different concentrations of Teucrium montanum L. hydrolate were added: 0% (CH), 0.6% (CH-TMh1), 0.8% (CH-TMh2), and 1.2% w/v (CH-TMh3) calculated based on the dry matter content of extract per volume of chitosan solution. The solutions were homogenized, poured into 9 cm diameter Petri dishes, and allowed to dry for 48 h at room temperature.

2.5. Determination of Mechanical Properties of the Films

Determination of the mechanical properties of the films was carried out following previously described methods [12,13]. The thickness of each film was measured at five different points using a digital micrometer (INSIZE 2364-10, Precision Measurement, China) according to ISO 4593:1993 [14] to obtain a representative average value. Tensile strength (MPa) and elongation at break (%) were determined using a texture analyzer (TA.XT plus, Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, UK), following the method used by Dordevic et al., [12]. For testing, film strips of 7 cm × 1 cm were prepared and tested following the ASTM D882-02 standard [15]. During testing, the strips were clamped with an initial grip separation of 5 cm.

2.6. Determination of Water Content, Solubility, and Swelling Degree of Films

For the analysis, all film samples were cut into 2 cm × 2 cm squares, and the initial mass of each sample was measured using an analytical balance (JOANLAB, Analytical Balance, China) and marked as W1. The samples were then dried in a laboratory oven (Sutjeska, Belgrade, Serbia) for 2 h at 105 °C, after which the mass W2 was determined. Subsequently, the films were immersed in 25 mL of distilled water and left for 24 h. After this period, the samples were carefully blotted with filter paper and their mass measured and marked as W3. The films were then dried again for 24 h at 105 °C, and the final mass was marked as W4. Each experimental procedure was performed in triplicate. Based on the measured masses, the water content, solubility, and swelling degree were calculated according to the following Equations (1)–(3) reported in the research [16]:

Water content (%) = [(W1 − W2)/W1] × 100

Solubility (%) = [(W2 − W4)/W2] × 100

Degree of swelling (%) = [(W3 − W2)/W2] × 100

2.7. Determination of Free Radical Scavenging Activity Using DPPH (2,2–Diphenyl–1–Picrylhydrazyl)

The degree of free radical scavenging was determined by the DPPH method. For the analysis, 0.1 g of each film sample was weighed and added to 20 mL of ethanol. The samples were then stirred for 30 min and subsequently filtered. From the obtained filtrate, 3 mL aliquots were mixed with 1 mL of 0.1 mM DPPH solution (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), which was prepared the previous day by dissolving DPPH in ethanol. The prepared mixtures were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark, after which the absorbance was measured at 517 nm [17]. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The antioxidant activity was calculated according to the corresponding Equation (4):

where AbsDPPH—absorbance of DPPH solution, Abs sample—sample absorbance.

DPPH scavenging activity [%] = [(AbsDPPH − Abs sample)/AbsDPPH] × 100

2.8. Content of Antioxidant Compounds in Films

The total polyphenols on the film samples were determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method. For analysis, 0.1 g of the film sample was weighed and added to 4 mL of distilled water. The samples were mixed for about 10 min, after which 0.2 mL of extract was separated and mixed with 1 mL of previously diluted Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (1:10, v/v) and 0.8 mL of 7.5% sodium carbonate solution (Na2CO3) were added. The mixtures were then incubated in the dark for 30 min, after which the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 765 nm. A blank sample was prepared by replacing 0.2 mL of the sample with the distilled water. All analyses were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of sample (mg GAE/g) [18].

2.9. Determination of Antimicrobial Activity of Films

The antimicrobial activity of the films was tested using a modified disk diffusion method, in accordance with the recommendations of the European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). The test was conducted against seven bacterial strains: Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, Proteus vulgaris ATCC 8427, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603, Bacillus cereus, as well as one yeast strain: Candida albicans ATCC 2091. The inoculum concentration was adjusted to approximately 1–2 × 108 CFU/mL, corresponding to a turbidity of 0.5 McFarland standard. The inoculum was applied to the surface of nutrient agar (Torlak, Belgrade, Serbia) for bacteria, and Sabouraud maltose agar (Torlak, Belgrade, Serbia) for yeast, using a sterile cotton swab. Disks with a diameter of 6 mm were, cut from films and exposed to UV radiation (260 nm) for disinfection. After disinfection, the films were placed on agar plates previously inoculated with the corresponding microorganisms. The plates were incubated for 18 h at 35–37 °C, after which the diameter of the inhibition zone around each disk was measured and expressed in millimeters. The appearance of a zone of inhibition or the absence of microbial growth directly under the disk was considered a positive result.

2.10. Attenuated Total Reflection (FTIR—Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy) Analysis

The infrared (FTIR) spectra of the film samples were recorded using a spectrometer BOMEM MB-100 (Hartmann & Braun, Brampton, ON, Canada). The samples were previously ground and homogenized with potassium bromide (KBr), an inert material that does not absorb IR radiation. The obtained mixture was pressed into IR-transparent pellets, which were then placed in the appropriate holder for analysis. Spectroscopic measurements were carried out by averaging 16 scans per sample, with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and a data interval of 0.5 cm−1.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed for three values of each experiment by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test within the software SPSS 21.0 (IBM, New York, NY, USA, SAD). The results were labeled as statistically different when the p value was lower than 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Film

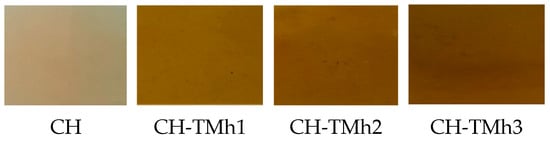

The addition of mountain germander hydrolate to the chitosan film led to significant changes in the visual characteristics of the obtained films (Figure 1). The control sample (CH), without the addition of hydrolate, was the brightest, while the incorporation of hydrolate resulted in a gradual darkening of the films depending on the concentration. The most pronounced change was observed in the sample with the highest concentration (CH-TMh3—1.2%), which showed the darkest shade of brown. These changes indicate the presence of phenolic compounds and other bioactive hydrolate components that contribute to the coloration of the films and the reduction in transparency. Similar results were reported in a study by Wang and coworkers [19], where the incorporation of honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica T.) flower extract into chitosan films caused darkening in accordance with increasing extract concentration. Also, Wang and coworkers [4] showed that the addition of pine bark extract (Pinus spp.) leads to a visible decrease in transparency and the appearance of a darker shade of the films. In the research of Silva and colleagues [20], the application of Coffea arabica leaf extract resulted in greenish-brown films, which further confirmed that natural plant extracts significantly affect the visual appearance and optical properties of chitosan films. These results clearly confirm that the incorporation of plant extracts and hydrolates, rich in polyphenolic compounds, can change the visual properties of films, whereby color and transparency depend on the type of extract used and its concentration.

Figure 1.

Appearance of films based on chitosan without and with the addition of mountain germander hydrolate; CH—chitosan-based film without added hydrolate; CH-TMh1, CH-TMh2, CH-TMh3—chitosan-based films with the addition of mountain germander hydrolate in a concentration of 0.6%, 0.8%, and 1.2%, respectively.

3.2. Mechanical Properties of the Films

Table 1 shows the textural and mechanical properties of chitosan films with the addition of different concentrations of mountain germander hydrolate, which provides an insight into their potential applicability in the field of sustainable food packaging.

Table 1.

Textural properties of edible films based on chitosan with the addition of mountain germander hydrolate.

Significant differences in film thickness were observed between the control sample and the samples with the addition of mountain germander hydrolate. The largest difference was recorded between the CH and CH-TMh3 samples, while CH-TMh1 and CH-TMh2 samples did not show significant differences between each other. These findings confirm that increasing the hydrolate concentration leads to an increase in film thickness. Similar results were reported by Nxumalo et al. [21], where the thickness of the pure chitosan film was 0.128 mm, while the addition of Lippia javanica extract increased it to 0.189 mm at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 1%. Mechanical properties represent a key factor in evaluating the functionality of films for food packaging applications [22]. Parameters such as elongation at break and tensile strength reflect the ability of the film to withstand mechanical stress and maintain structural integrity. The elongation at break of the control sample (CH), as well as the CH-TMh1 and CH-TMh2 samples, was at a similar level, with differences of 3–4%. However, the CH-TMh3 sample showed significantly higher elongation (98.93%), representing a 13% increase compared to the control sample (85.53%). This indicates that a higher concentration of hydrolate positively influences the flexibility of the film. These results are in accordance with the study by Nxumalo et al. [21], where extracts of Lippia javanica, Syzygium cordatum, and Ximenia caffra were used. The baseline elongation of the pure chitosan film was 25.4%, while the addition of extracts increased it to 41.9%, 35.3%, and 29.2%, respectively. Similar effects were observed in the study by Bajić et al. [7], where chestnut bark (Castanea sp.) extract was used, leading to an increase in film elongation from 5.1% to 10.3%. Liu et al. [23], used rose essential oil, which increased the elongation of chitosan films for 3.8%. The tensile strength of the control film was 5.66 MPa, which is higher compared to the films with hydrolate addition. Among the hydrolate-containing samples, CH-TMh2 showed the highest strength (4.17 MPa), while CH-TMh3 reached 4.12 MPa. The differences in tensile strength can be attributed to the reduction in cohesiveness and the disruption of compact structure due to interactions between chitosan and bioactive components from the hydrolate. The obtained results are consistent with the findings of Nxumalo et al., [21], where the tensile strength of pure chitosan film was 23.4 MPa, while the addition of plant extracts (Lippia javanica, Syzygium cordatum, and Ximenia caffra) decreased it to 17.7 MPa, 14.1 MPa, and 14.3 MPa, depending on the type of extract. A similar effect was noted in the study by Wang et al., [19], where the addition of an aqueous extract of Lonicera japonica T. into chitosan films reduced the tensile strength from 23.4 MPa in the control film to 17.7 MPa in the extract containing film. It is evident that the mechanical characteristics of enriched films largely depend on the type and origin of the added extract. Differences among the control films were also noticed, indicating that the type of chitosan and acid used, as well as the method of film preparation, influence the final mechanical characteristics of chitosan-based films.

3.3. Water Content, Solubility, and Swelling Degree of Films

Table 2 shows the results for water content, solubility, and degree of swelling of chitosan-based edible films with the addition of mountain germander hydrolate.

Table 2.

Water content, solubility and degree of swelling of edible chitosan-based films with the addition of mountain germander hydrolate.

It is evident that the incorporation of hydrolat significantly reduces the water content. The control sample (CH) exhibited the highest water content (30.09%), whereas the hydrolate-enriched films showed markedly lower values. The lowest water content was recorded in the sample with the highest hydrolate concentration (CH-TMh3), amounting to 12.25%. These results indicate that increasing the concentration of hydrolate leads to a decrease in water content, which is consistent with previous studies [12,21]. Kahya et al. [24] demonstrated that the application of aqueous extracts of sage and rosemary also resulted in reduced water content in chitosan films. A similar trend was reported by Nxumalo et al. [21], where extracts of Lippia javanica, Syzygium cordatum, and Ximenia caffra decreased the water content of the films. In the study by Bajić et al. [7], the incorporation of oak and hop extracts led to a significant reduction in water content (21.5% and 23.6%, respectively) compared to pure chitosan (29.6%). The control sample (CH) had the highest solubility (42.27%) (Table 2). The sample with the lowest hydrolate concentration (CH-TMh1) showed similar values, while increasing concentrations of hydrolate progressively reduced solubility. The lowest solubility was observed in CH-TMh3 (37.79%). Bajić and colleagues [7], demonstrated a similar effect, showing that the addition of oak and hop extracts reduced the solubility of chitosan films from 25.3% to 23.5% and 23.8%, respectively. This is probably the consequence of the presence of hydroxyl and carboxyl groups of phenolic compounds, which form stronger interactions with chitosan, thereby reducing its binding affinity for water. Films with lower water content and reduced solubility are more suitable for application in food packaging of moisture sensitive products [25]. The swelling degree of chitosan films with and without mountain germander hydrolate is also shown in Table 2. Swelling of chitosan films arises from the presence of hydroxyl and amino groups in the aminopolysaccharide structure, which enable interactions with water molecules [26]. The highest swelling degree (30.26%) was observed in the control sample (CH), while the hydrolate-enriched films exhibited a gradual decrease in this parameter. The lowest swelling degree (12.79%) was recorded in the sample with the highest hydrolate concentration (CH-TMh3). These findings are consistent with the study of Dordevic et al. [12], where the incorporation of plant extracts from blueberry, red grape, and parsley also led to reduced swelling of the films. Conversely, Moradi et al. [27], reported the opposite effect and increase in solubility and swelling upon incorporation of grape seed extract. Interestingly, in the same study, the combination of grape seed extract with Zataria multiflora essential oil reduced swelling, indicating that the hydrophobic components of essential oils may modulate water absorption capacity. These results confirm that the type and chemical composition of plant extracts directly influence the hydrophilicity and structural properties of chitosan films, with polyphenols and hydrophobic molecules exerting opposite effects on water absorption [27].

3.4. Antioxidant Activity of Films

Table 3 shows the results of the degree of neutralization of free radicals and the content of total polyphenols in chitosan films. These parameters are essential for evaluating the antioxidant properties of films, which is especially important in the context of their application in food protection and extending their shelf life.

Table 3.

The degree of neutralization of free radicals and the total content of polyphenols in the samples of films based on chitosan with the addition of mountain germander hydrolate.

The control sample (CH) contained the lowest total phenolic content (2.40 mg GAE/g film). It exhibited the expected but limited antioxidant activity, which is consistent with the well-known ability of chitosan to inhibit reactive oxygen species and slow down lipid oxidation [12]. This value probably originates from the reduction reaction of the amino/hydroxyl groups of chitosan with Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, and not from the phenolic compounds themselves. Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, although widely used to estimate total phenolic content, is known to react with a wide range of reducing species in complex matrices, including amino and hydroxyl functional groups present in polysaccharide matrices such as chitosan [28,29,30]. In contrast, films enriched with mountain germander hydrolate displayed significantly higher antioxidant activity. The most pronounced effect was observed in sample CH-TMh2, which demonstrated the highest radical scavenging capacity (92.90%) and the highest total phenolic content (38.78 mg GAE/g film). Interestingly, the sample with a lower amount of hydrolate (CH-TMh2) showed higher antioxidant activity compared to the sample with the highest hydrolate concentration (CH-TMh3). Accordingly, the antioxidant response of chitosan–polyphenol films is influenced not only by the total phenolic content, but also by the molecular interactions (nature of polyphenol–polymer interactions) and aggregation phenomena within the chitosan matrix. The enhanced antioxidant activity of hydrolate-enriched films can be attributed to the presence of bioactive phenolic compounds in the hydrolate, such as gallic acid, caffeic acid, epicatechin, ferulic acid, naringin, and rutin [10]. In the study conducted by Sailović and colleagues [10], in which the phenolic content, antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory potentials of Teucrium montanum hydrolate were analyzed, a high level of total polyphenols (109.11 mg GAE/g DW, i.e., per gram of dry weight) and strong radical scavenging capacity (IC50 = 35.70 mg/mL) were reported.

3.5. Antimicrobial Activity of Films

Improving the antimicrobial activity of the chitosan film is achieved by adding a suitable extract, which has better antimicrobial activity [26]. The results of testing the antimicrobial activity of chitosan-based films with the addition of mountain germander hydrolate are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Antimicrobial activity of chitosan-based films with the addition of mountain germander hydrolate expressed as the diameter of inhibition zones (mm).

Based on the obtained results, it can be concluded that the control sample (CH) ex-hibited antimicrobial activity against P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, P. vulgaris ATCC 8427, and B. subtilis ATCC 6633, while no activity was observed against the other tested micro-organisms, including E. coli ATCC 25922, S. aureus ATCC 25923, K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603, B. cereus, and the yeast C. albicans ATCC 2091. In contrast, the films supplemented with mountain germander hydrolate demonstrated pronounced antimicrobial activity, confirming their potential for bioprotective applications. The strongest effect was observed against S. aureus ATCC 25923, where the CH-TMh2 and CH-TMh3 samples achieved the largest inhibition zones (16.33 mm), while moderate activity was observed against B. subtilis ATCC 6633 (12.1–12.17 mm). The CH-TMh2 sample exhibited the highest efficiency against E. coli ATCC 25922 (12.33 mm), whereas the greatest effect against B. cereus was observed for CH-TMh3 (11 mm). For K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603, CH-TMh1 and CH-TMh2 showed similar results (11–11.33 mm), while the hydrolate addition did not exhibit antimicrobial activity against C. albicans ATCC 2091. The antibacterial activity can be directly attributed to the presence of bioactive compounds in the hydrolate of mountain germander. In a study conducted by Sailović and colleagues [10], during the examination of the aqueous extract of the same plant, the presence of numerous bioactive components was recorded, including phenylethanoid glycosides (caerulescenoside, echinacoside, verbascoside, and isoverbascoside), flavonoids, and phenolic acids as the most dominant. These substances have been identified as compounds with pronounced antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties [31]. The water solubility of these compounds can explain their abundance in the hydrolate [32]. Antimicrobial mechanism of phenylethanoid glycosides are most possibly the consequence of the presence of phenolic hydroxyls and their affinity with proteins in the microbial cells [33]. The obtained results confirm that the incorporation of hydrolate into chitosan films significantly enhances their antimicrobial efficacy, in agreement with previous studies demonstrating a similar effect of plant extracts on the properties of chitosan films [12]. On the other hand, films showed no effect against C. albicans ATCC 2091. This can be explained by the formation of biofilm which cause fungal cells aggregation and formation of microcolonies which are extremely tolerant of antimicrobial agents [34]. Additionally, the high resistance of the fungal strain can be the result of cell morphology and multilayer cell wall [35].

3.6. Attenuated Total Reflection (FTIR—Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy)

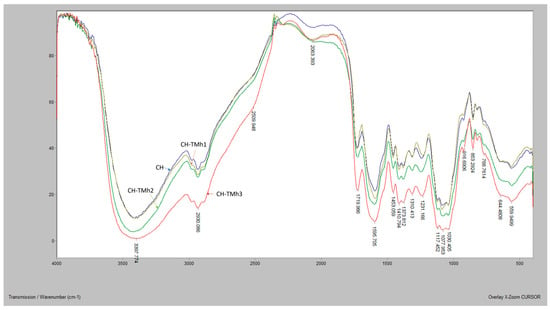

FTIR spectra of chitosan films, with and without the addition of mountain germander hydrolate, are presented in Figure 2. The spectrum of the control sample (CH) displays characteristic vibrations of chemical bonds present in the chitosan structure. A broad absorption band in the range of 3751–3658 cm−1 is attributed to O–H stretching, while the peak at 3398 cm−1 corresponds to hydroxyl groups of phenols and alcohols. C–H bond vibrations in vinyl and alkyl groups were observed at 2930 cm−1. The absorption at 1720 cm−1 indicates the presence of carbonyl (C=O) groups, whereas C=C bond vibrations were detected at 1595 cm−1. The peak at 1453 cm−1 is assigned to C–C aliphatic stretching, and the peak around 1117 cm−1 corresponds to C–N stretching. Vibrations around 1230 cm−1 are associated with combined C–O, C–C, and C–O–C groups. Additionally, C–H deformation in aryl and vinyl groups is observed at 888 cm−1 and 620 cm−1. These findings are consistent with previous studies [4,36]. The FTIR spectrum of sample CH-TMh1 (lowest hydrolate concentration) did not show significant changes compared to the control, although peaks at 1117 cm−1 (C–N stretching) and 1453 cm−1 (C=C vibrations in aromatic groups) were observed. For samples CH-TMh2 and CH-TMh3, with higher hydrolate concentrations, more pronounced changes in the spectra were evident. The most notable are peaks in the range of 1720–1595 cm−1, indicating the presence of C=O groups. Vibrations in the range of 1437–1489 cm−1 suggest the presence of aromatic compounds. The appearance of new and intensified peaks in these samples indicates interactions between hydrolate components and the chitosan matrix, in agreement with previous findings [9].

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of chitosan films supplemented with mountain germander hydrolate CH—chitosan-based film without added hydrolate; CH-TMh1, CH-TMh2, CH-TMh3—chitosan-based films with the addition of mountain germander hydrolate in concentrations of 0.6%, 0.8%, and 1.2%, respectively.

4. Conclusions

Based on the conducted study, it can be concluded that the addition of Teucrium montanum L. hydrolate significantly modifies the properties of chitosan films. The changes in mechanical properties confirm interactions between bioactive components and the polymer matrix. Mechanical properties, including elongation and tensile strength, are also modulated by the hydrolate addition, with the concentration of the additive playing a key role. The reduction in water content, solubility, and swelling degree suggests improved film stability, whereas the increase in total polyphenols and enhanced antioxidant activity confirms the potential of the hydrolate for functional enrichment of the films. Antimicrobial properties, particularly against certain bacterial strains, further support the applicability of these films in active food packaging. These results highlight the potential of Teucrium montanum L. hydrolate as a natural additive for enhancing chitosan films, contributing to the development of sustainable and functional materials for the food industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D. and P.S.; methodology, D.D.; software, I.K.; validation, B.D., D.D. and I.K.; formal analysis, L.Ž., K.C. and J.M.; investigation, J.M.; resources, D.D.; data curation, K.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Ž.; writing—review and editing, B.D.; visualization, I.K.; supervision, B.D., project administration, I.K.; funding acquisition, D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovations of the Republic of Serbia, grant numbers 451-03-136/2025-03/200050.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Popović, S.Z.; Lazić, V.L.; Hromiš, N.M.; Šuput, D.Z.; Bulut, S.N. Biopolymer Packaging Materials for Food Shelf-Life Prolongation. In Biopolymers for Food Design; Academic Press: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2018; pp. 223–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, T.; Biswas, D.; Rhim, J.W. Antimicrobial Nanofillers Reinforced Biopolymer Composite Films for Active Food Packaging Applications. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2022, 32, e00353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kola, V.; Carvalho, I.S. Plant Extracts as Additives in Biodegradable Films and Coatings in Active Food Packaging. Food Biosci. 2023, 54, 102860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yin, J.; Cong, M.; Qi, Y.; Wan, K.; Jiang, G.; Liu, X. Characterization of Chitosan Film Incorporated with Pine Bark Extract and Application in Carp Slices Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čalija, B.; Milić, J.; Krajišnik, D.; Račić, A. Karakteristike i Primena Hitozana u Farmaceutskim/Biomedicinskim Preparatima. Arh. Farm. 2013, 63, 347–364. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, M.; Naviglio, D.; Caruso, A.A.; Ferrara, L. 13-Applications of Chitosan as a Functional Food. In Nanotechnology in the Agri-Food Industry: Novel Approaches of Nanotechnology in Food; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 425–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajić, M.; Ročnik, T.; Oberlintner, A.; Scognamiglio, F.; Novak, U.; Likozar, B. Natural Plant Extracts as Active Components in Chitosan-Based Films: A Comparative Study. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 21, 100365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradinaru, L.M.; Barbalata-Mandru, M.; Enache, A.A.; Rimbu, M.C.; Badea, I.G.; Aflori, M. Chitosan Membranes Containing Plant Extracts: Preparation, Characterization and Antimicrobial Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šeremet, D.; Vojvodić Cebin, A.; Mandura, A.; Komes, D. Valorisation of Teucrium montanum as a Source of Valuable Natural Compounds: Bioactive Content, Antimicrobial and Biological Activity. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2021, 15, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailović, P.; Odžaković, B.; Bodroža, D.; Vulić, J.; Čanadanović-Brunet, J.; Zvezdanović, J.; Danilović, B. Polyphenolic Composition and Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antihyperglycemic Activity of Different Extracts of Teucrium montanum from Ozren Mountain. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastić, N.; Švarc-Gajić, J.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Morais, S.; Barroso, M.F.; Moreira, M. Subcritical Water Extraction of Antioxidants from Mountain Germander Teucrium montanum L. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 138, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordevic, S.; Dordevic, D.; Sedláček, P.; Kalina, M.; Tešíková, K.; Antonić, B.; Tremlová, B.; Treml, J.; Nejezchlebová, M.; Vapěnka, L.; et al. Incorporation of Natural Blueberry, Red Grapes and Parsley Extract By-Products into the Production of Chitosan Edible Films. Polymers 2021, 13, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, K.; Chang, W.; Chiou, B.S.; Chen, M.; Liu, F. Regulating the Physicochemical Properties of Chitosan Films through Concentration and Neutralization. Foods 2022, 11, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HRN ISO 4593:1993; Plastics-Film and Sheeting-Determination of Thickness by Mechanical Scanning. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993.

- ASTM D882-02; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2002.

- Souza, V.G.L.; Fernando, A.L.; Pires, J.R.A.; Rodrigues, P.F.; Lopes, A.A.S.; Fernandes, F.M.B. Physical Properties of Chitosan Films Incorporated with Natural Antioxidants. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 107, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adilah, A.N.; Jamilah, B.; Noranizan, M.A.; Hanani, Z.A.N. Utilization of Mango Peel Extracts on the Biodegradable Films for Active Packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomadoni, B.; Cassani, L.; Ponce, A.; Moreira, M.R.; Aguero, M.V. Optimization of Ultrasound, Vanillin and Pomegranate Extract Treatment for Shelf-Stable Unpasteurized Strawberry Juice. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 72, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Q.; Tong, J.; Zhou, J. Physiochemical Properties of Chitosan Films Incorporated with Honeysuckle Flower Extract for Active Food Packaging. J. Food Process Eng. 2015, 40, e12305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.; dos Santos Valle, A.B.; de Oliveira Lemos, A.S.; Campos, L.M.; Fabri, R.L.; Costa, F.F.; Gomes da Silva, J.; Pinto Vilela, F.M.; Tavares, G.D.; Rodarte, M.P.; et al. Development and Characterization of Chitosan Film Containing Hydroethanolic Extract of Coffea arabica Leaves for Wound Dressing Application. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 108503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nxumalo, K.A.; Fawole, O.A.; Aremu, A.O. Development of Chitosan-Based Active Films with Medicinal Plant Extracts for Potential Food Packaging Applications. Processes 2024, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Deshmukh, R.K.; Gaikwad, K.K.; Negi, Y.S. Physicochemical Characterization of Antioxidant Film Based on Ternary Blend of Chitosan and Tulsi-Ajwain Essential Oil for Preserving Walnut. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Shi, J.; Zhang, R.; Tang, H.; Xie, C.; Wang, F.; Han, J.; Jiang, L. Chitosan/Esterified Chitin Nanofibers Nanocomposite Films Incorporated with Rose Essential Oil: Structure, Physicochemical Characterization, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Properties. Food Chem. 2023, 18, 100714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahya, N.; Kestir, M.S.; Oztruk, S.; Jolak, A.; Torlak, E.; Kalajdžioglu, Z.; Akin-Evingur, G.; Erim, B.F. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Chitosan Films Enriched with Aqueous Sage and Rosemary Extracts as Food Coating Materials: Characterization of the Films and Detection of Rosmarinic Acid Release. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 217, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Jiang, W. Development of Antioxidant Chitosan Film with Banana Peels Extract and Its Application as Coating in Maintaining the Storage Quality of Apple. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 1205–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, D.; Lal, J.S.; Devaky, K.S. Release Studies of the Anticancer Drug 5-Fluorouracil from Chitosan-Banana Peel Extract Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, M.; Tajik, H.; Razavi Rohani, S.M.; Oromiehie, A.R.; Malekinejad, H.; Aliakbarlu, J.; Hadian, M. Characterization of Antioxidant Chitosan Film Incorporated with Zataria multiflora Boiss Essential Oil and Grape Seed Extract. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edo, G.I.; Ndudi, W.; Ali, A.B.M.; Yusif, E.; Zainulabdin, K.; Akpogelie, P.O.; Isodje, E.F.; Igbuku, U.A.; Opiti, R.A.; Esagah, A.E.A.; et al. Chitosan: A review of its properties, solubility, functional technologies, applications in food and health. Carbohydr. Res. 2025, 550, 109409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everette, J.D.; Bryant, Q.M.; Green, A.M.; Abbey, Y.A.; Wangila, G.W.; Walker, R.B. Thorough study of reactivity of various compound classes toward the folin-Ciocalteu reagent. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 8139–8144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikawa, M.; Schaper, T.D.; Dollard, C.A.; Sasner, J.J. Utilization of folin-ciocalteu phenol reagent for the detection of certain nitrogen compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1811–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Georgiev, M.I.; Cao, H.; Nahar, L.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Sarker, S.D.; Xiao, J.; Lu, B. Therapeutic potential of phenylethanoid glycosides: A systematic review. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 1585–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Z.; Yang, B. Phenylethanoid Glycosides: Research Advances in Their Phytochemistry, Pharmacological Activity and Pharmacokinetics. Molecules 2016, 21, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusky, D.; Keen, N.T. Involvement of preformed antifungal compounds in the resistance of subtropical fruits to fungal decay. Plant Dis. 1993, 77, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandai, D.; Tabana, Y.M.; Ouweini, A.E.; Ayodeji, I.O. Resistance of Candida albicans Biofilms to Drugs and the Host Immune System. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2016, 9, e37385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenardon, M.D.; Sood, P.; Dorfmueller, H.C.; Brown, A.J.P.; Gow, N.A.R. Scalar nanostructure of the Candida albicans cell wall: A molecular, cellular and ultrastructural analysis and interpretation. Cell Surf. 2020, 6, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhowmik, S.; Agyei, D.; Ali, A. Enhancement of Mechanical, Barrier, and Functional Properties of Chitosan Film Reinforced with Glycerol, COS, and Gallic Acid for Active Food Packaging. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 41, e01092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.