A CVaR-EIGDT-Based Multi-Stage Rolling Trading Strategy for a Virtual Power Plant Participating in Multi-Level Coupled Markets

Abstract

1. Introduction

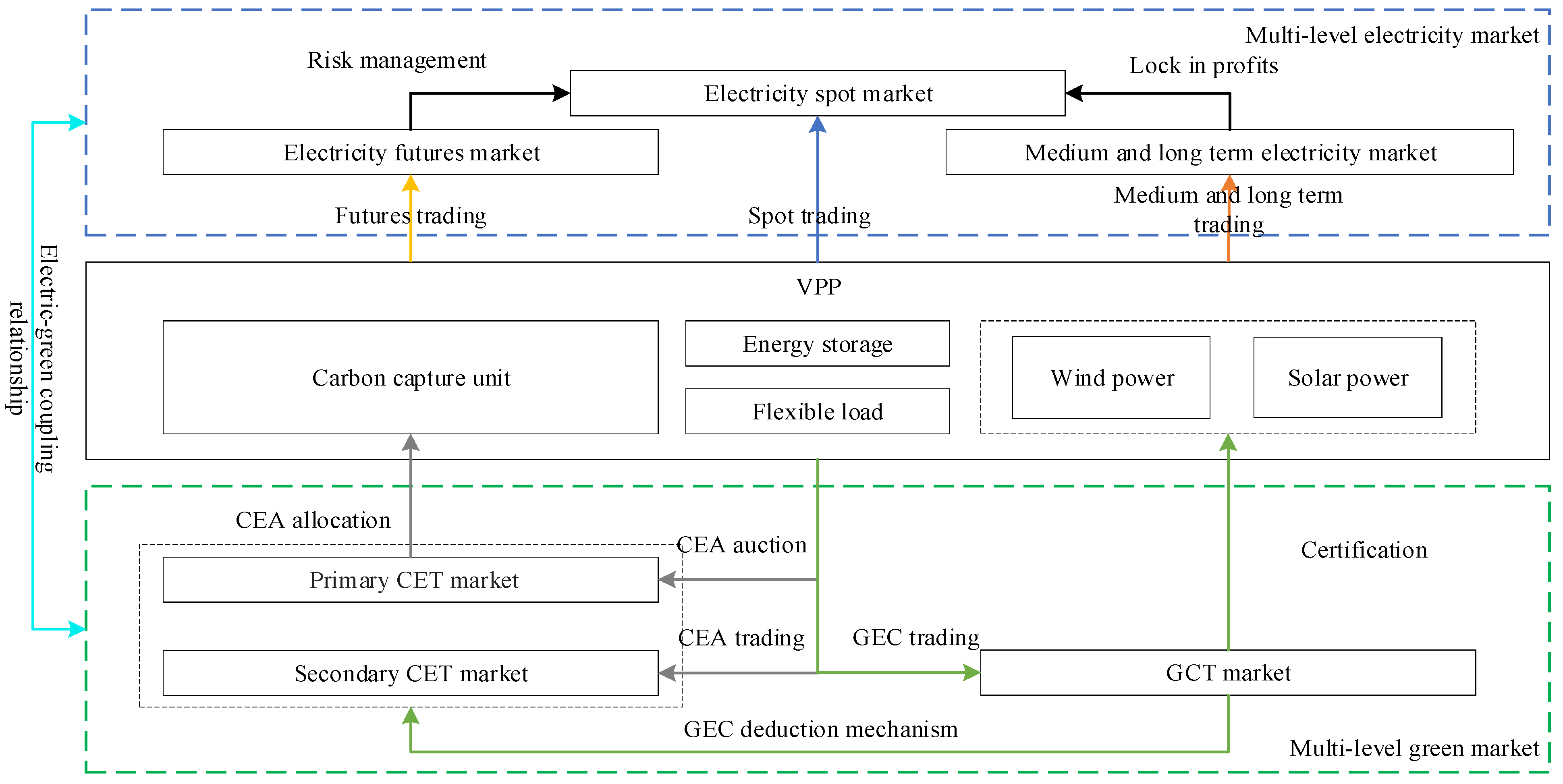

2. The Multi-Level Coupled Market Framework Involving VPP Participation

2.1. Coupling Relationship of Spot, Futures, Medium-, and Long-Term Market

2.2. Coupling Relationship of Electricity, CET, and GCT Markets

2.3. Market Assumptions

2.3.1. Price Taker Assumption

2.3.2. VPP Assumption

3. VPP Deterministic Trading Model in a Multi-Level Coupled Market

3.1. Objective Function

3.2. Constraints

3.2.1. Annual Constraints

- Constraints of annual electricity energy contract

- Constraints of the primary CET market before the year:

- Constraints of signing for electricity futures:

- Constraints of year-end green market compliance:

3.2.2. Monthly Constraints

- Constraints of medium- and long-term electric energy contracts:

- Constraints of monthly green market transactions divided into parts:

- Constraint of monthly power generation capacity of carbon capture unit.

3.2.3. Daily Constraints

- Constraints of flexible load

- Constraints of spot market trading:

- Constraints of carbon capture unit:

- Constraints of carbon capture system:

- Constraints of upper and lower limits of renewable energy outputs:

- Constraints of energy storage:

- Constraint of VPP energy balance:

- Constraint of dispatching cost

- Constraint of futures-delivery profit:

- Constraint of CEAs daily trading:

- Constraint of GECs’ daily trading:

4. VPP Multi-Stage Transaction Decision-Making Model and Solution Based on CVaR-EIGDT

4.1. Uncertainty Modeling Based on CVaR-EIGDT

4.1.1. Modeling Uncertainty in Renewable Energy Outputs with CVaR

4.1.2. Modeling Uncertainty in Market Prices Uncertainty with EIGDT

4.1.3. Uncertainty Independence Based on CVaR-EIGDT

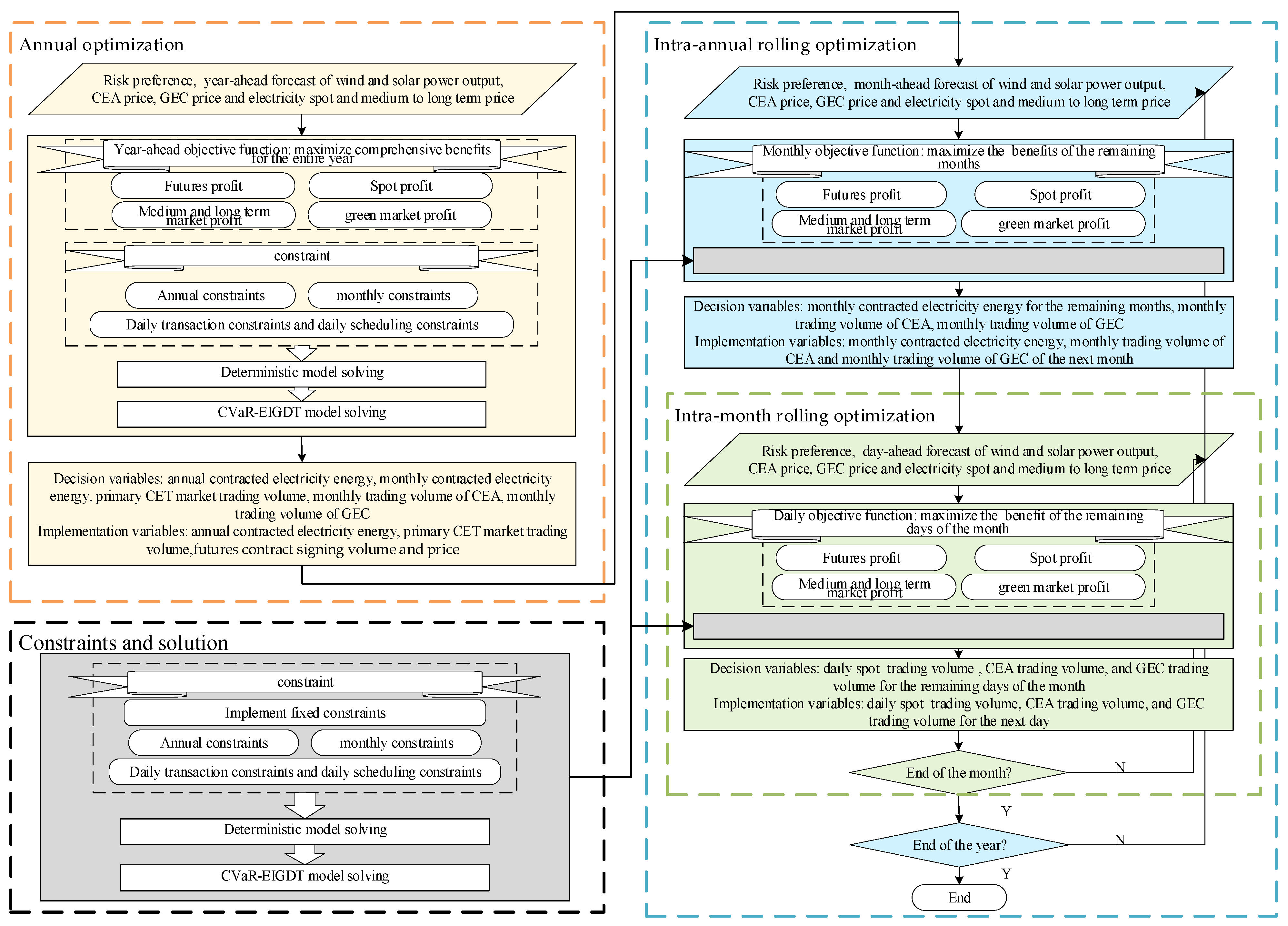

4.2. Multi-Stage Rolling Decision-Making Method

4.3. Model Solution

5. Case Study Analysis and Comparative Discussions

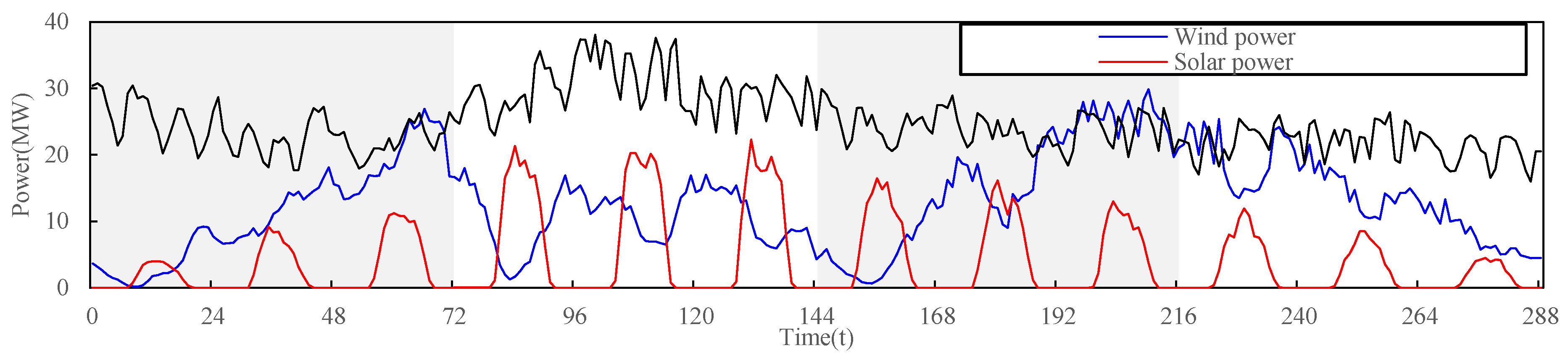

5.1. Case Introduction

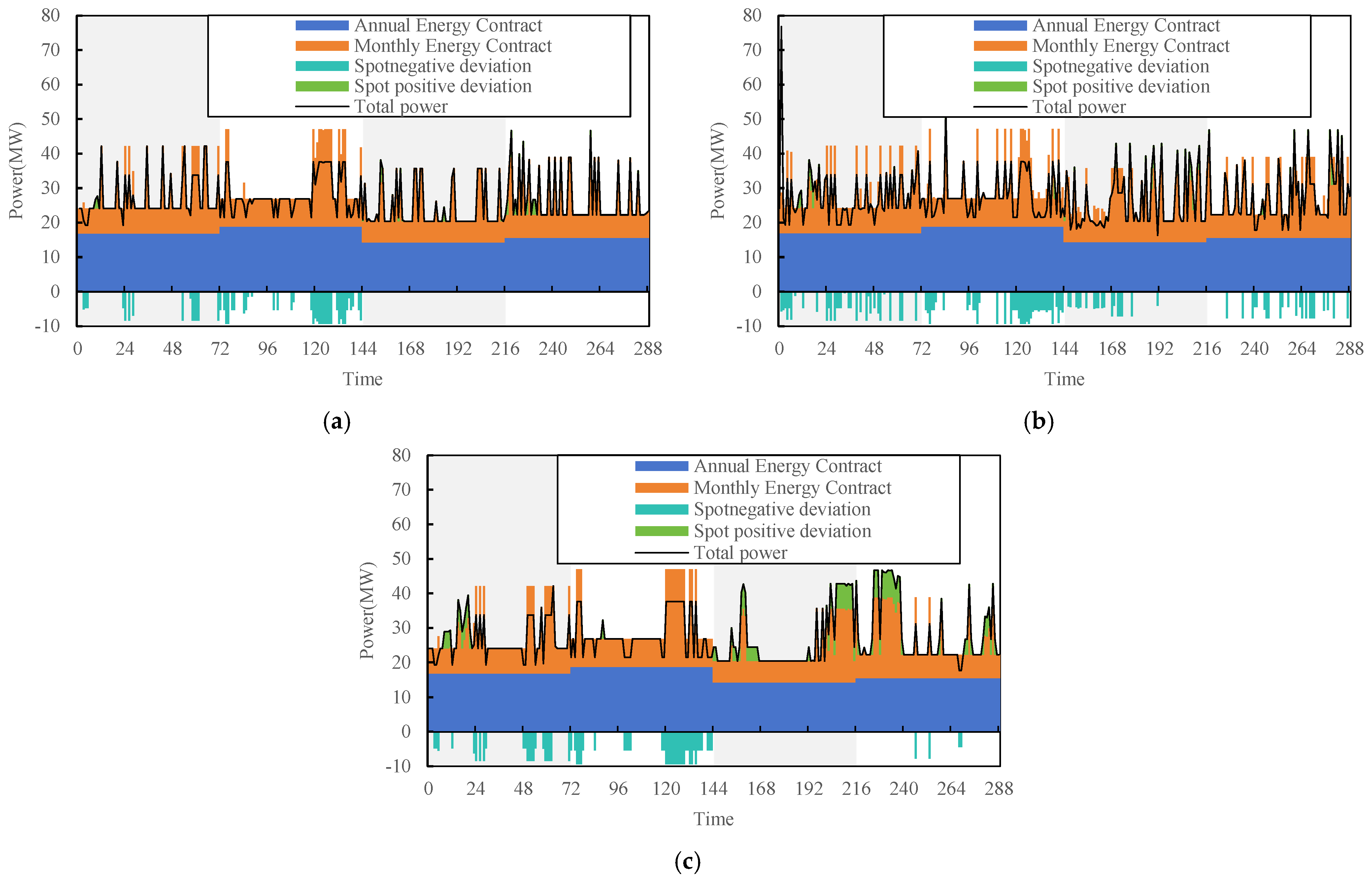

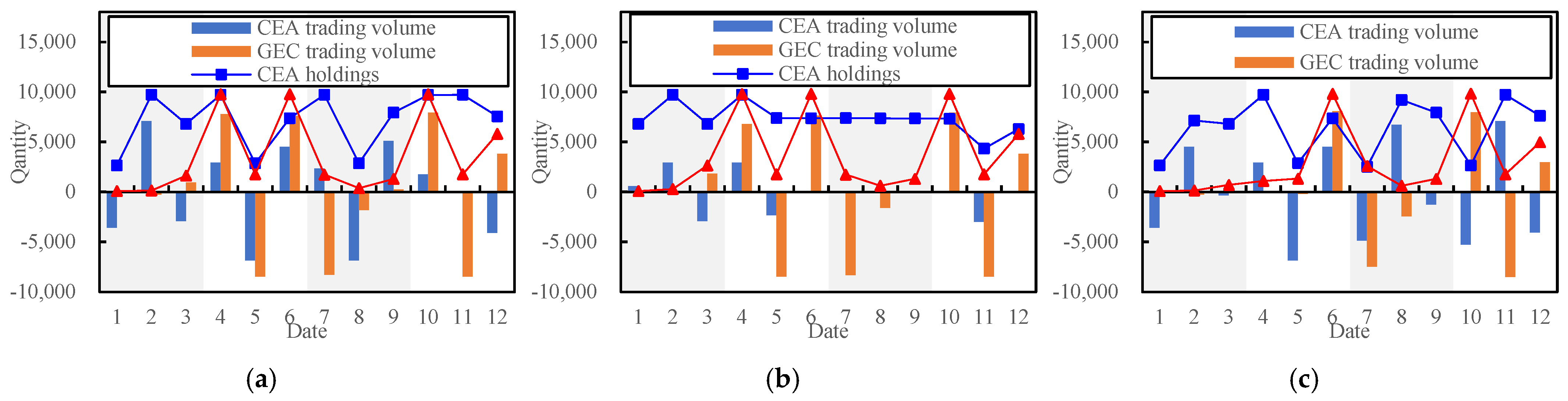

5.2. Analysis of Different Risk Decision

5.3. Analysis of Different Market Participation Situations

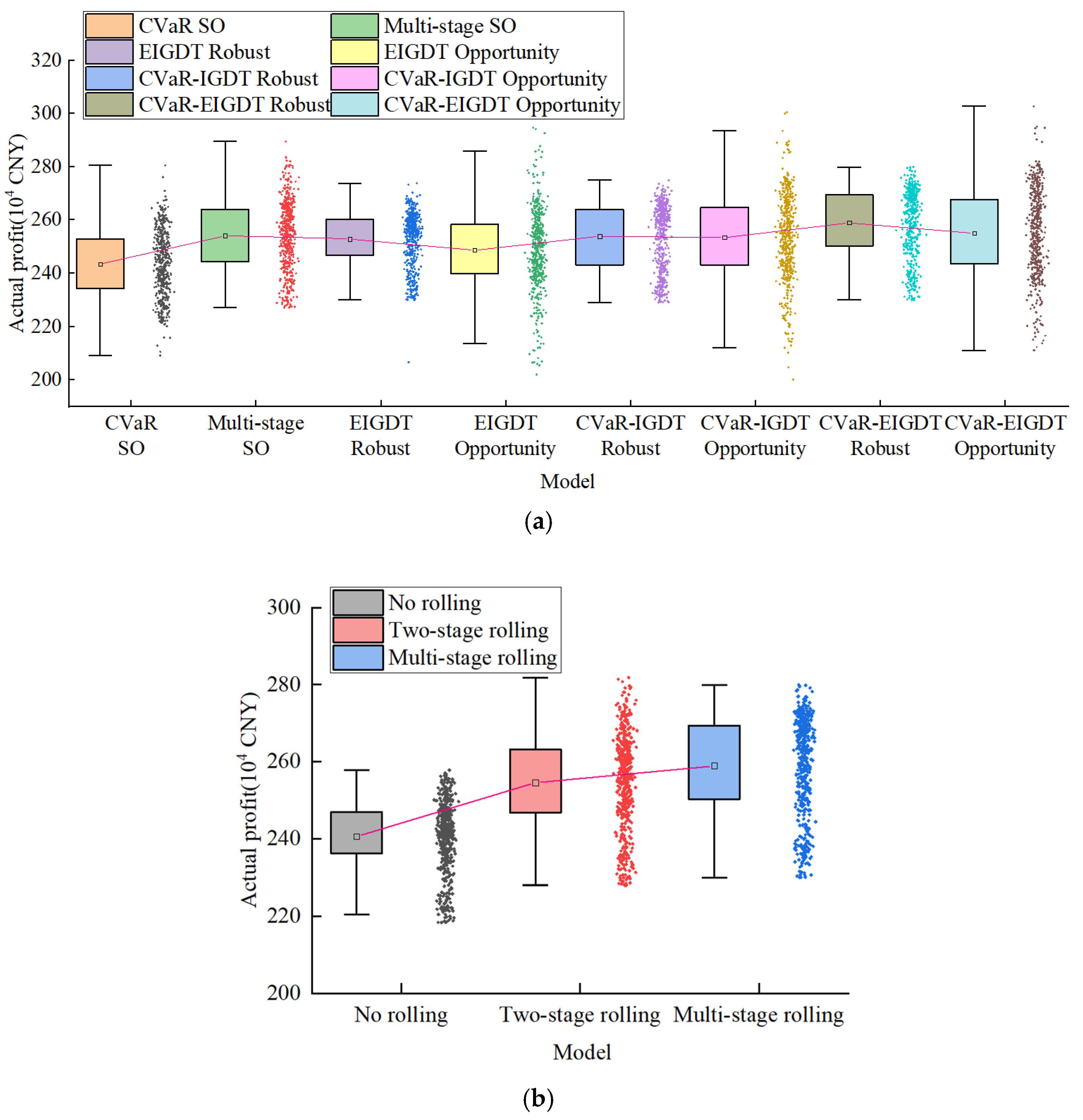

5.4. Analysis of Different Decision-Making Models

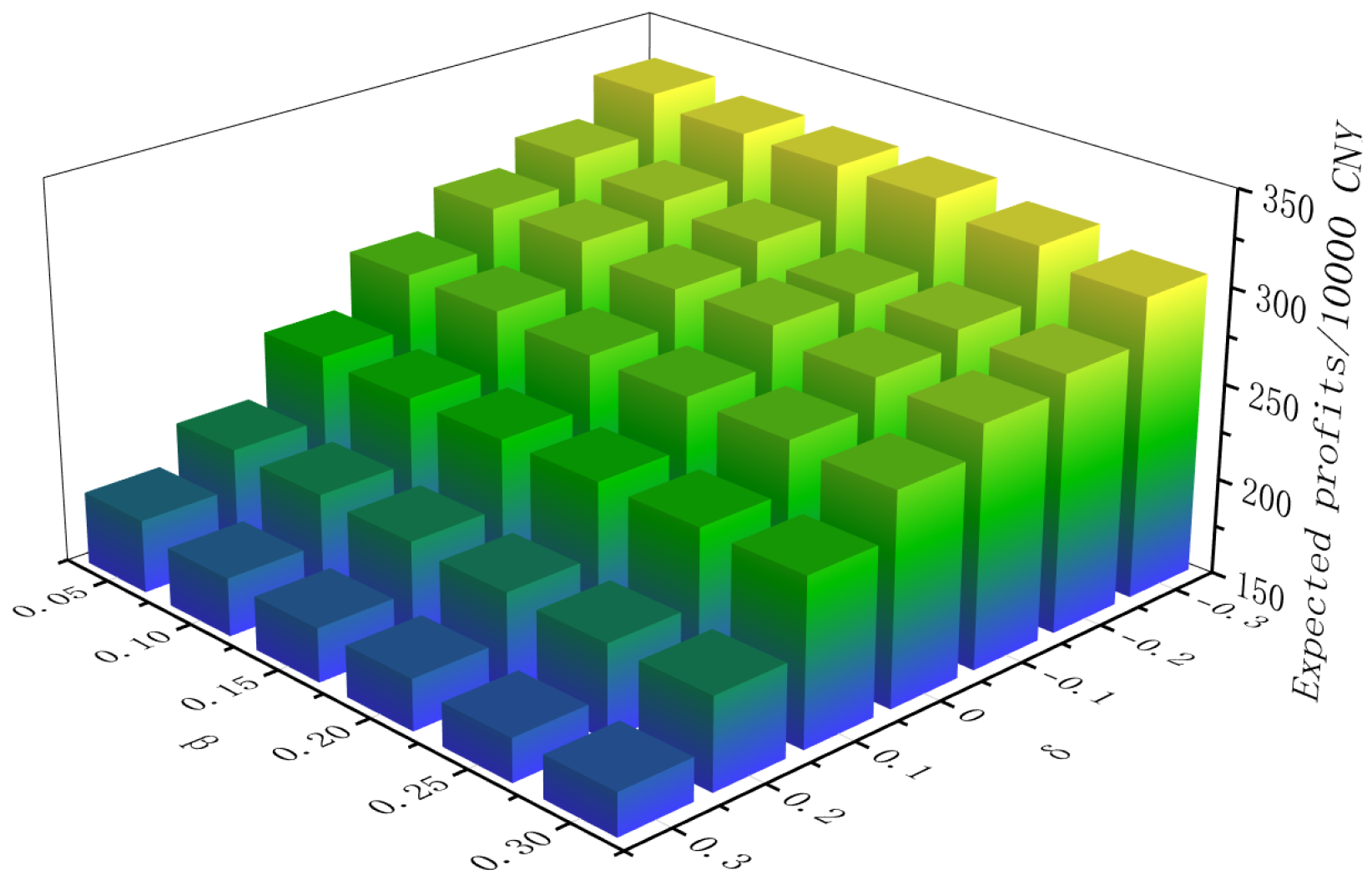

5.5. Sensitivity Analysis on Risk Parameters δ and β

5.6. Analysis of Linearization Efficiency

5.7. Analysis of Applicability Across Different VPP Resource Scales

5.8. Sensitivity Analysis of Different Regulatory Parameters

5.9. Analysis of Case for Annual Time Scales

5.10. Comparative Discussions with State-of-the-Art Methods

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Energy Administration. 2024 Annual Report on the Development of China’s Electricity Market. Available online: https://www.nea.gov.cn/20250717/54ae0fdb11f04b39a5b670999c04ef81/c.html (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Development Report on China’s Green Electricity Certificates. 2024. Available online: https://www.nea.gov.cn/20250421/adcc933deed143dbbbfad982eacfc624/c.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Progress Report of China’s National Carbon Market. 2025. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/ydqhbh/wsqtkz/202509/t20250927_1128352.shtml (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Liu, W. Guangzhou Municipal Local Financial Supervision and Administration Bureau: Support the Guangzhou Futures Exchange in Advancing Carbon Futures Research. Futures Daily. 2024. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.28619/n.cnki.nqhbr.2024.000321 (accessed on 11 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, W. Review and Prospect of Coupled Electricity-Carbon-Renewable Portfolios Trading. Electr. Power Constr. 2023, 44, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Wei, Z.; Lan, S.; Shi, S.; Su, P. Market-Wide Revenue Optimization Model of Power Generation Company Considering Electricity Futures Trading. Electr. Power Constr. 2024, 45, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hongliang, W.; Benjie, L.; Daoxin, P.; Ling, W. Virtual Power Plant Participates in the Two-Level Decision-Making Optimization of Internal Purchase and Sale of Electricity and External Multi-Market. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 133625–133640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, J.; De, G. Research on Trading Optimization Model of Virtual Power Plant in Medium- and Long-Term Market. Energies 2022, 15, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Chen, K.; Sun, G.; Lin, S.; Jiang, C. Bidding Strategy for the Virtual Power Plant Based on Cooperative Game Participating in the Electricity-Carbon Joint Market. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 163, 110325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, J.; Sun, G.; Han, H.; Zang, H.; Wei, Z. A Two-Stage Robust Trading Strategy for Virtual Power Plant in Multi-Level Electricity-Carbon Market. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2024, 48, 1838–1846. [Google Scholar]

- Rockafellar, R.T.; Uryasev, S. Optimization of Conditional Value-at-Risk. J. Risk 2000, 2, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedeh-Barhagh, S.; Abapour, M.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Shafie-Khah, M.; Laaksonen, H. Optimal Scheduling of a Microgrid Based on Renewable Resources and Demand Response Program Using Stochastic and IGDT-Based Approach. J. Energy Storage 2024, 86, 111306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajehvand, M.; Fakharian, A.; Sedighizadeh, M. A Risk-Averse Decision Based on IGDT/Stochastic Approach for Smart Distribution Network Operation under Extreme Uncertainties. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 107, 107395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Guan, L. Hybrid Optimization for Collaborative Bidding Strategy of Renewable Resources Aggregator in Day-Ahead Market Considering Competitors’ Strategies. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 145, 108681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.A.; Nazari-Heris, M.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Zare, K.; Marzband, M.; Shafie-Khah, M.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A.; Catalão, J.P.S. Network-Constrained Joint Energy and Flexible Ramping Reserve Market Clearing of Power- and Heat-Based Energy Systems: A Two-Stage Hybrid IGDT–Stochastic Framework. IEEE Syst. J. 2021, 15, 1547–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliasghari, P.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Abapour, M. Risk-Based Scheduling Strategy for Electric Vehicle Aggregator Using Hybrid Stochastic/IGDT Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, T.; Yao, Y.; Ma, G.; Li, X.; Yu, X.; Xu, W.; Wang, J. IGDT-Based Two-Layer Optimization of Trading Strategies in Multi-Energy Markets. Energy 2025, 333, 137374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Liao, S.; Ke, D.; Yao, L.; Mao, B. Bidding Strategies of Load Aggregators for Day-Ahead Market with Multiple Uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 2786–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, S.; Lin, Z.; Wen, F.; Yang, L.; Wang, Q. A Mixed CVaR-Based Stochastic Information Gap Approach for Building Optimal Offering Strategies of a CSP Plant in Electricity Markets. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 85772–85783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaloie, H.; Vallee, F.; Lai, C.S.; Toubeau, J.-F.; Hatziargyriou, N. Day-Ahead and Intraday Dispatch of an Integrated Biomass-Concentrated Solar System: A Multi-Objective Risk-Controlling Approach. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 37, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission Notice on Completing the Full Coverage of Renewable Energy Green Electricity Certificates and Promoting the Consumption of Renewable Energy Electricity. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xwdt/tzgg/202308/t20230803_1359093.html (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Tian, Y.; Qin, Z.; Huang, Z. Day-Ahead Operational Strategy for Virtual Power Plant Considering Green Certificate Classification in Coupled Market. Electr. Power Constr. 2025, 46, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Huang, W. Overview of Global Electricity Futures Market and Analysis of Contract Characteristics. Secur. Futures China 2018, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggins, F.A.V.; Ejeh, J.O.; Brown, S. Going, Going, Gone: Optimising the Bidding Strategy for an Energy Storage Aggregator and Its Value in Supporting Community Energy Storage. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 10518–10532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. Notice on Completing the Allocation and Liquidation of National Carbon Emission Rights Trading Quotas for the Power Generation Industry in 2023 and 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202410/content_6981938.htm (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Ke, D.; Liao, S.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y. Bi-Level Stochastic Optimization for A Virtual Power Plant Participating in Energy and Reserve Market Based on Conditional Value at Risk. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 2502–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianyuan, W.; Chengcheng, G.; Kechen, L. Anomaly Electricity Detection Method Based on Entropy Weight Method and Isolated Forest Algorithm. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 984473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.V.; Granville, S.; Fampa, M.H.C.; Dix, R.; Barroso, L.A. Strategic Bidding under Uncertainty: A Binary Expansion Approach. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2005, 20, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, R.J.; Waddell, L.A. Modeling Using Logical Constraints. In Encyclopedia of Optimization; Pardalos, P.M., Prokopyev, O.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-3-030-54621-2. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Yin, X.; Chung, C.Y.; Rayeem, S.K.; Chen, X.; Yang, H. Managing Massive RES Integration in Hybrid Microgrids: A Data-Driven Quad-Level Approach with Adjustable Conservativeness. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 7698–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangdong Power Exchange Center. Available online: https://pm.gd.csg.cn/portal/#/home (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- National Carbon Market Information Network. Available online: https://www.cets.org.cn/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- China Green Electricity Certificate Trading Platform. Available online: https://www.greenenergy.org.cn/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Ding, T.; Hu, Y.; Bie, Z. Multi-Stage Stochastic Programming with Nonanticipativity Constraints for Expansion of Combined Power and Natural Gas Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, W.; Chen, H.; Yu, Z.; Hu, L.; Huang, Y. Optimal Scheduling Strategy for Virtual Power Plants with Aggregated User-Side Distributed Energy Storage and Photovoltaics Based on CVaR-Distributionally Robust Optimization. J. Energy Storage 2024, 86, 110770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, J.; Kong, X. Multi-Agent Simulation for Strategic Bidding in Electricity Markets Using Reinforcement Learning. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 9, 1051–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Market Entity | Market Frameworks | An Independent Entity in Each Market |

|---|---|---|---|

| [6] | Thermal power | Futures market, medium- and long-term market, spot market | Yes |

| [7] | VPP | Internal and external electricity retail markets, CET, and GCT markets | No |

| [8] | VPP | CFD market and GCT market | No |

| [9] | VPP | Electricity market and CCER market | Yes |

| [10] | VPP | “Medium- and long-term + spot” electricity market and the “primary + secondary” CET market | No |

| This paper | VPP | “futures + medium- and long-term + spot” multi-level electricity market and “primary CET + secondary CET + GCT” multi-level green market | Yes |

| Reference | Method | Uncertainty | Applicable Entity | Applicable Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | IGDT | Load | Integrated Energy System | Multi-energy markets |

| [18] | SO-IGDT | Electricity prices, distributed energy outputs | Load aggregator | Electricity Market |

| [19] | CVaR-IGDT | CSP output, electricity prices | CSP Plant | Electricity Market |

| [20] | CVaR-IGDT | System outputs, electricity prices | Integrated Biomass–CSP System | Electricity Market |

| This paper | CVaR-EIGDT | Renewable energy outputs, electricity prices, green market prices | VPP | Multi-level electricity–green coupled market |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0.26, 0.29, 0.22, 0.24) | α | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | |||

| Ki | 0.85 | 0.25 | 0.4231 | 0.25 | |||

| 2160 | −2160 | 10,060 | (0.2, 0.29, 0.31, 0.2) × | ||||

| 60 | 30 | −30 | θ | 0.27 | |||

| 30 | 13.5 | 0.9 | 0.9 | ||||

| 25 | 10 | 40 | 15 | ||||

| 25 | 30 | 0.1 | g | 1.2 |

| Profits or Cost (104 CNY) | Robust Model | Deterministic Model | Opportunity Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expected profits | 239.3 | 270.2 | 291.5 |

| Primary CET market profits | −4.0 | −4.0 | −4.0 |

| Secondary CET market profits | 21.4 | 20.8 | 35.5 |

| GCT market profits | 22.7 | 25.0 | 25.0 |

| Medium-to-long-term profits | 336.9 | 352.4 | 383.9 |

| Futures profits | 3.3 | 0.0 | 5.4 |

| Spot profits | −11.9 | 4.2 | −9.7 |

| Average total costs | 128.1 | 128.2 | 129.2 |

| Average dispatching costs | 2.2 | 2.0 | 3.2 |

| Average Electricity Energy/MW·h | Robust Model | Deterministic Model | Opportunity Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power generation | Carbon capture unit | 10,157.3 | 10,160.9 | 10,159.7 |

| Wind power | 3677.3 | 3683.4 | 3693.4 | |

| Solar power | 1213.3 | 1218.5 | 1221.3 | |

| Traded electricity Energy | Annual energy contract | 4715.6 | 4715.6 | 4715.6 |

| Monthly energy contract | 3146.3 | 3202.7 | 3557.1 | |

| Spot negative deviation | 339.4 | 428.6 | 700.0 | |

| Spot positive deviation | 72.7 | 422.3 | 194.4 | |

| Total spot deviation | 412.1 | 850.8 | 894.4 | |

| Indicator | Robust Model | Deterministic Model | Opportunity Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year-end CEAs holdings | 6291 | 7551 | 7614 |

| Year-end GECs holdings | 5804 | 5804 | 4973 |

| Offset amounts of GECs | 863 | 863 | 509 |

| Annual carbon capture volume/tCO2 | 1196.3 | 0.0 | 508.7 |

| Modes | Multi-Level Electricity Market | Multi-Level Green Market | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Futures Market | Medium- and Long-Term Market | Spot Market | Primary CET Market | Secondary CET Market | GCT Market | |

| M1 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| M2 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - |

| M3 | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| M4 | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| M5 | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| M6 | - | √ | - | √ | √ | √ |

| M7 | - | - | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Modes | Robust Model Profits (104 CNY) | Deterministic Model Profits (104 CNY) | Opportunity Model Profits (104 CNY) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 239.3 | 270.2 | 291.5 |

| M2 | 196.3 | 219.9 | 238.8 |

| M3 | 194.5 | 217.1 | 235.5 |

| M4 | 238.7 | 270.8 | 289.8 |

| M5 | 212.4 | 262.6 | 261.4 |

| M6 | 239.4 | 266.2 | 290.5 |

| M7 | 235.8 | 262.6 | 266.9 |

| Model Profits (104 CNY) | No Rolling | Two-Stage Rolling | Multi-Stage Rolling |

|---|---|---|---|

| CVaR SO model | 279.2 | 281.5 | 280.8 |

| Multi-stage SO model | 281.6 | 286.3 | 285.1 |

| EIGDT robust model | 244.3 | 242.9 | 241.9 |

| EIGDT opportunity model | 298.6 | 294.6 | 286.1 |

| CVaR-IGDT robust model | 243.3 | 243.0 | 239.0 |

| CVaR-IGDT opportunity model | 312.9 | 302.3 | 294.9 |

| CVaR-EIGDT robust model | 243.2 | 242.9 | 239.3 |

| CVaR-EIGDT opportunity model | 298.2 | 296.7 | 291.5 |

| Profits or Cost (104 CNY) | CVaR-EIGDT | CVaR-IGDT | Multi-Stage SO Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robust Model | Opportunity Model | Robust Model | Opportunity Model | ||

| Expected profits | 239.3 | 291.5 | 239.0 | 294.9 | 285.1 |

| Primary CET market profits | −4.0 | −4.0 | −4.0 | −4.0 | −4.0 |

| Secondary CET market profits | 21.4 | 35.5 | 6.9 | 72.8 | 20.5 |

| GCT market profits | 22.7 | 25.0 | 21.0 | 2.9 | 26.0 |

| Medium-to-long-term profits | 336.9 | 383.9 | 339.7 | 369.0 | 350.7 |

| Futures profits | 3.3 | 5.4 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 5.3 |

| Spot profits | −11.9 | −9.7 | 2.0 | −15.6 | −1.5 |

| Average total costs | −128.1 | −129.2 | −127.7 | −133.0 | −112.0 |

| Average dispatching costs | 2.2 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 5.7 | 2.7 |

| Indicator | Before Linearization | After Linearization | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robust Model | Opportunity Model | Robust Model | Opportunity Model | |

| Total Solver time/s | 2924.6 | 726.6 | 1241.0 | 635.1 |

| Expected profit/CNY | 2,388,931 | 2,904,848 | 2,393,498 | 2,915,466 |

| Resources | Carbon Capture Unit | Wind Power | Solar Power | Energy Storage | Flexible Load | Expected Profit/104 CNY | Total Solver Time/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 239.3 | 1241.0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 55.7 | 1494.5 | |

| 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 681.9 | 757.1 | |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 259.1 | 3496.3 | |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 742.6 | 2088.8 |

| Expected Profits/104 CNY | K0 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8049 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | ||

| KGCT | 0.25 | 239.3 | 226.9 | 218.0 | 207.5 | 194.1 | 180.3 |

| 0.35 | 237.7 | 229.3 | 217.3 | 205.6 | 193.3 | 180.6 | |

| 0.45 | 237.2 | 226.3 | 214.6 | 206.5 | 194.6 | 178.2 | |

| Indicator | Annual Optimization | Intra-Annual Rolling Optimization | Intra-Month Rolling Optimization | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Month | Average | First Day | Average | ||

| Solver time/s | 11,549.3 | 10,350.9 | 1263.3 | 9887.7 | 1052.6 |

| Expected profit/104 CNY | 6972.1 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeng, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, S. A CVaR-EIGDT-Based Multi-Stage Rolling Trading Strategy for a Virtual Power Plant Participating in Multi-Level Coupled Markets. Processes 2026, 14, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010077

Zeng H, Chen H, Zhang S. A CVaR-EIGDT-Based Multi-Stage Rolling Trading Strategy for a Virtual Power Plant Participating in Multi-Level Coupled Markets. Processes. 2026; 14(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Haodong, Haoyong Chen, and Shuqin Zhang. 2026. "A CVaR-EIGDT-Based Multi-Stage Rolling Trading Strategy for a Virtual Power Plant Participating in Multi-Level Coupled Markets" Processes 14, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010077

APA StyleZeng, H., Chen, H., & Zhang, S. (2026). A CVaR-EIGDT-Based Multi-Stage Rolling Trading Strategy for a Virtual Power Plant Participating in Multi-Level Coupled Markets. Processes, 14(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010077