Abstract

Nowadays, consumer demand for functional foods with health benefits has grown significantly. In response to this trend, a variety of potentially probiotic foods have been developed—most notably kefir and kefir-like beverages, which are highly appreciated for their tangy flavor and health-promoting properties. Traditionally, kefir is made by fermenting cow’s milk with milk kefir grains, although milk from other animals—such as goats, ewes, buffalo, camels, and mares—is also used. Additionally, non-dairy versions are made by fermenting plant-based milks (such as coconut, almond, soy, rice, and oat) with the same type of grains, or by fermenting fruit and vegetable juices (e.g., apple, carrot, fennel, grape, tomato, prickly pear, onion, kiwifruit, strawberry, quince, pomegranate) with water kefir grains. Despite their popularity, many aspects of kefir production remain poorly understood. These include alternative production methods beyond traditional batch fermentation, kinetic studies of the process, and the influence of key cultivation variables—such as temperature, initial pH, and the type and concentration of nutrients—on biomass production and fermentation metabolites. A deeper understanding of the fermentation process can enable the production of kefir beverages tailored to meet diverse consumer preferences.

1. Introduction

Recently, consumer interest in functional foods enriched with bioactive components that promote health and longevity has risen markedly [1]. Among these, particular attention has been directed toward products containing probiotics (live beneficial microorganisms), prebiotics (substrates that selectively stimulate beneficial gut microbes), and synbiotics (strategic combinations of probiotics and prebiotics). These categories of functional foods are increasingly incorporated into everyday diets as convenient vehicles for modulating gut health and overall well-being [1,2,3,4].

A growing body of evidence suggests that regular consumption of probiotic, prebiotic, and synbiotic products may confer multiple health benefits through their antibacterial, anticancer, anti-allergic, and immune-modulatory activities. Reported outcomes include improvements in gastrointestinal function, restoration and maintenance of a balanced gut microbiota, enhancement of mucosal immune responses, and support of systemic homeostasis. In addition, these products have been associated with reduced blood cholesterol and glucose levels, improved nutrient absorption, attenuation of inflammatory bowel conditions, and mitigation of various immunopathological states [2,3,4].

Fermented foods, which frequently serve as delivery matrices for such bioactive microorganisms and substrates, have also been extensively investigated in this context. Regular intake of fermented dairy and non-dairy products has been linked with symptom relief in disorders such as ulcerative colitis, diarrhea, and constipation, as well as with a lower risk of colorectal carcinogenesis [2,3,4]. Collectively, these observations underscore the potential of functional and fermented foods as adjuncts in strategies aimed at maintaining gut health and preventing chronic disease.

The recommended daily intake of dairy products varies by age, sex, and country, but most major health organizations suggest 2–3 servings per day for adults. For example, the USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend 3 servings of low-fat or fat-free dairy per day for adults and children over 9 years old, with slightly lower amounts for younger children and some regional variation. A serving is typically defined as 1 cup (240–250 mL) of milk, ¾–1 cup of yogurt, or 30–40 g of cheese. Many European guidelines also recommend 2–4 servings per day, with some countries specifying 250 mL of milk or equivalent and 20–40 g of cheese daily for adults. The World Health Organization does not set a universal daily dairy recommendation, but recognizes dairy as an important source of protein and nutrients, especially for vulnerable populations. Lower-fat dairy options are generally advised for adults and children over 2 years to support heart health and weight management [5].

Although yogurt remains the best-known fermented dairy product worldwide, kefir gained popularity during the 20th century—particularly among populations in the Caucasus region, where it was traditionally made from sheep’s milk [6]. In regions such as Russia, Central Asia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, kefir has been consumed for centuries. Today, its popularity is spreading to Europe, Japan, and the United States, largely due to its nutritional and therapeutic properties. Reports from different sources support this statement [7,8,9,10], although the data provided vary depending on the source. For example, in 2024, the global kefir market was estimated at USD 2155.31 million by the IMARC Group [8] and at USD 1305.40 million by Future Market Insights, Inc. [9], while another report from Grand View Horizon, Inc. [10] indicated a size of USD 1259.30 million.

In 2024, Europe led the global kefir market with significant revenue of USD 600.4 million, while the United States accounted for USD 208.2 million and Japan for USD 53.1 million [8]. According to the same source, the kefir market in Europe, the United States, and Japan is expected to reach revenues of USD 798.6 million, USD 281.0 million, and USD 74.5 million, respectively, by 2030 [8].

Kefir is widely recognized as an excellent source of probiotics with significant health-promoting properties. Probiotics may be defined as live microorganisms that, when consumed in sufficient quantities, provide a health benefit to the host [11]. To achieve probiotic effects, a beverage must contain viable cells at a concentration of at least 106–107 colony-forming units (CFU) per mL or gram [12,13]. Elie Metchnikoff, a Nobel Prize-winning scientist and pioneer in innate immunology, proposed this concept in the early 20th century. He suggested that consuming dairy products containing “beneficial bacteria” could allow these microorganisms to colonize the gut, thereby improving health and potentially extending lifespan [14].

The term “kefir” is derived from the Turkish word keyif, meaning “to feel good,” reflecting the pleasant sensation experienced by consumers. Historically, among the inhabitants of the Caucasus Mountains, kefir grains were considered “a gift from Allah” and were regarded as part of a family’s wealth [14].

The Codex Alimentarius Standard for Fermented Milks (CXS 243-2003) [15] describes kefir as a fermented dairy beverage that is lightly carbonated and contains low levels of alcohol and acetic acid, produced from cow’s milk inoculated with kefir grains. This nutritionally rich, health-promoting food has been associated with numerous benefits, including immune system stimulation, blood pressure regulation, inhibition of tumor growth, enhanced digestion (especially in lactose-intolerant individuals), suppression of pathogenic bacteria responsible for gastrointestinal disorders and vaginal infections, and cholesterol reduction [16,17,18,19].

Kefir can be produced using either traditional or industrial methods. The traditional (artisanal) method involves inoculating milk with 2–10% (w/v) milk kefir grains, followed by static fermentation for 18–28 h at 20–25 °C. The industrial (Russian) method uses a commercial starter culture (2–8%, w/v), with fermentation carried out for 18–28 h at 18–24 °C, followed by maturation for 12 h at 8–10 °C [20,21,22]. For non-dairy kefir beverages made from fruits, vegetables, and spices, the substrates are pasteurized, cooled, inoculated with water kefir grains, and fermented at 20–37 °C, away from direct sunlight, for 20–25 h [23] or for 48–96 h, depending on the formulation and desired characteristics [24,25].

Although commercial kefir production remains predominantly based on cow’s milk [7], goat kefir is also currently available on the market. For example, kefir products found in some supermarkets across Spain (Table 1) are fermented milk-based foods produced using kefir lactic ferments, although this is not always clearly specified. These products are either unsupplemented (natural kefir) or supplemented with fruit purées, flavoring ingredients, sugar, modified corn starch, salt, colorants, stabilizers, and preservatives. Since the base of most of these products is pasteurized milk (Table 1), they should be classified as flavored kefir beverages rather than fruit-based kefir beverages.

Table 1.

Composition of selected commercial kefir products from various supermarkets in Spain.

As shown in Table 1, the use of kefir lactic acid bacteria in the production of natural kefir, instead of traditional kefir grains, indicates the use of defined starter cultures (freeze-dried) rather than conventional grains. This choice sacrifices microbial diversity in favor of stability.

In the case of kefir supplemented with fruit purees, the addition of modified corn starch and xanthan gum suggests that fermentation did not produce enough exopolysaccharide (kefiran) to provide adequate texture, or that the fruit interferes with the gel’s rheology.

Finally, for coconut-based kefir-like beverages, the inclusion of corn starch and thickeners (such as gellan gum and pectin) suggests the need for exogenous texturizing agents. This is probably because the plant-based matrix (coconut drink and coconut water) lacks casein, which is necessary to form the traditional gel network.

The ubiquitous labeling of “generic lactic acid bacteria” in these commercial products, rather than the explicit mention of kefir grains, highlights the main challenge of industrialization: the difficulty of scaling production based on physical kefir grains. These grains grow slowly and are difficult to separate mechanically on a large scale without damage. Consequently, the industry has shifted to using “Russian-style kefir” or fermentation assisted by isolated cultures, which could alter the final product’s sensory and microbiological profile.

Beyond cow and goat milk, a variety of other animal milks—including buffalo, camel, mare, ewe, and, more recently, donkey milk—have been explored as substrates for kefir production [26,27].

In addition, a wide range of fruits and vegetables and whey have been investigated for the development of kefir-like beverages [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. In these cases, both milk kefir grains [28,29,35,36,38,39,40] and water kefir grains [32,33,36,37], or cultures of microorganisms isolated from them [30,31,34,35,36], have been used as inocula.

Utilizing non-dairy substrates provides multiple benefits: it allows the formulation of kefir-style probiotic beverages accessible to lactose-intolerant consumers, supports the valorization of otherwise low-value agricultural produce (such as fruits or vegetables), and offers potential economic returns for farmers. Moreover, it facilitates the development of new production processes and introduces novel, health-promoting probiotic beverages to the market [21,24,25].

Kefir grains harbor a symbiotic community of bacteria and yeasts [41]. While this microbiota may remain relatively stable when properly maintained [42], research indicates that its composition, as well as the resulting metabolic and volatile-compound profiles, are influenced by the grain’s origin and the processing parameters [21,43,44]. Therefore, understanding the key characteristics of the production process and how culture conditions and fermentation parameters affect the microbial, chemical, and sensory properties of kefir-like beverages is essential for their successful development.

Accordingly, the present work aims to provide valuable insights into the characteristics of kefir-like beverages, with particular emphasis on how fermentation conditions influence the properties of these probiotic-rich fermented products.

2. Kefir Grains

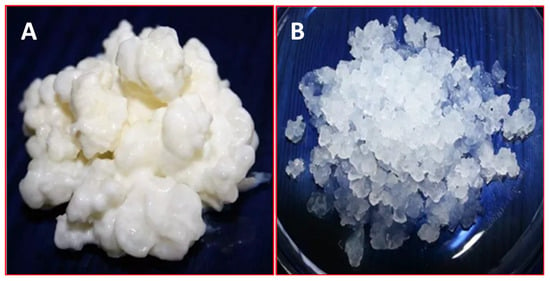

Morphologically, milk kefir grains (Figure 1A) range from 0.3 to 3.0 cm in diameter and vary from white to pale yellow. They have an irregular, multilobular structure with a firm, elastic, and viscous texture resembling small cauliflowers, popcorn, coral, or cottage cheese [14,45]. Although water is their principal component, they also contain proteins (27% insoluble, 6% soluble, and 5.6% free amino acids), kefiran [46], fats, mucopolysaccharides, vitamins B and K, tryptophan, and the minerals calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium [18].

Figure 1.

Milk (A) and water (B) kefir grains from Kefiralia (Burumart Commerce S.L., Arrasate, Guipúzcoa, Spain). Source: Kefiralia (https://www.kefiralia.es/).

Water kefir grains (Figure 1B), or sugary kefir grains, are used to ferment sugar-containing solutions and are consumed widely across Asia, Europe, and South America [23,24]. They consist of a polysaccharide matrix primarily composed of dextran, synthesized mainly by Lactobacillus species such as Lb. casei, Lb. nagelii, Lb. hordei, and Lb. hilgardii, as well as by Leuconostoc mesenteroides [47]. Smaller amounts of levan, a β-(2→6)-linked fructan with β-(2→1) branches, may also be present [48,49,50,51].

Morphologically, water kefir grains exhibit a gelatinous and elastic structure resembling cauliflower, with a crystal-like, jelly-like, or gummy texture and a clear to translucent appearance. Their clarity is typically maintained when fermenting sugar solutions prepared with refined white sugar; however, the grains tend to darken when used to ferment naturally pigmented substrates, such as Aronia melanocarpa juice [52].

Microbiologically, kefir grains contain a complex community of approximately 30 species of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), acetic acid bacteria (AAB), and yeasts living in symbiosis within the grain matrix [36,41,43,49,53,54,55]. These microorganisms collectively produce vitamins, degrade milk proteins, and comsume lactose, contributing to kefir’s nutritional and functional qualities [20]. Microbial composition varies with grain origin, fermentation substrate, and culture maintenance conditions [18].

LAB dominate both milk and water kefir, while bifidobacteria appear in lower proportions [56]. Nonetheless, the two grain types differ markedly in microbial composition. Lactobacillus species are most abundant in both, but Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, other bacterial genera (e.g., Bifidobacterium, Enterobacter, Gluconobacter, Pseudomonas, Serratia, Zymomonas), and various yeasts (e.g., Pichia, Lachancea, Hanseniaspora, Zygosaccharomyces) are more prevalent in water kefir. Conversely, milk kefir grains typically contain higher proportions of Acetobacter, Streptococcus, and Candida species. Strains of Kazachstania, Kluyveromyces, and Saccharomyces occur in similar amounts in both grain types [21,23].

3. Kefiran Production

Kefiran, the main exopolysaccharide (EPS) present in milk kefir grains, is responsible for binding the microorganisms together within the grain structure [57]. Morphologically, it forms an elastic, gelatin-like matrix that is both resilient and protective, shielding the embedded microbiota from adverse environmental factors, heavy metals, and desiccation [45].

This branched EPS, composed of equal amounts of glucose and galactose, is a water-soluble glucogalactan produced by Lb. kefiranofaciens, Lb. kefir, Lb. kefirgranum, Lb. parakefir, Lb. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, and Lb. plantarum. Its synthesis is stimulated by the presence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, demonstrating the symbiotic relationship between bacteria and yeasts within the grains [21,58,59,60,61,62,63].

Kefiran, known for its antitumor, antibacterial, and antifungal activities [21,58,64,65,66], represents approximately 45% of the dry weight of kefir grains. However, its molecular weight remains controversial, with reported values ranging from 5.5 × 104 Da to 1.0 × 107 Da [63,67]. This EPS can also form edible films similar to other water-soluble polysaccharides such as alginate, chitosan, carrageenan, cellulose derivatives, pectin, and starch [46,68].

In addition to its technological applications as an emulsifier, stabilizer, thickener, and gelling agent [68,69,70,71,72], kefiran exhibits various bioactivities, including healing, anti-inflammatory, antitumoral, immunomodulatory, hypocholesterolemic, and hypotensive effects [73,74,75,76]. Despite limited studies on its practical use in the food industry, kefiran offers several advantages compared with other low-cost gelling and film-forming polysaccharides:

- It is produced by food-grade lactic acid bacteria with GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) status [72];

- Its incorporation into food products provides additional health benefits, allowing it to be classified as a functional food component [46,77];

- Being microbially produced, kefiran can be synthesized in commercially available culture media, independent of agricultural raw material availability, which may be affected by seasonal or market fluctuations [63,78];

- Its chemical structure suggests potential prebiotic functionality [73,74,75,76].

Kefiran production has been investigated in laboratory-scale studies using pure cultures of Lb. kefiranofaciens grown in MRS broth [46,78]. However, lactic acid accumulation inhibits bacterial growth and reduces EPS synthesis, as kefiran is produced as a primary metabolite [72,78]. The use of continuous culture systems with separation techniques, such as membrane filtration or electrodialysis, to remove inhibitory acids has been rejected due to high cost and mechanical complexity [79].

An alternative approach involves mixed cultures of Lb. kefiranofaciens and S. cerevisiae, in which the yeast assimilates lactic acid produced by the bacterium and likely generates metabolites that enhance kefiran production [69,79,80,81]. Moreover, aerobic conditions, low agitation rates, and intermittent addition of fresh medium containing lactose and yeast extract have been shown to stimulate EPS synthesis in these mixed cultures [79,80,81].

Despite these promising results, scaling up either process for industrial kefiran production remains challenging. The main limitations are the high cost of the complex culture medium—typically modified MRS with lactose replacing glucose—and the fact that only capsular and excreted forms of kefiran can be obtained in the absence of kefir grains, rather than the grain-embedded form.

Currently, the main obstacles limiting industrial exploitation of kefiran in food and other sectors are low production yield and limited efficiency of product recovery [77]. These challenges could be addressed through optimized bioprocess technologies and improved fermentation strategies.

Several studies have demonstrated that kefir grains can ferment alternative, low-cost substrates such as whey [72,82,83], rice extract-based media [55], and sago starch [84]. However, most investigations have focused primarily on evaluating the suitability of these substrates for kefiran production [72] or assessing the functional properties of the resulting EPS [63,68,70], without addressing the feasibility of large-scale kefiran production using these alternative media.

4. Kefir and Kefir-like Beverages

Kefir is produced by inoculating various types of milk—whole, skimmed, or semi-skimmed—with milk kefir grains at a concentration of 5–10% (w/v). This inoculation rate can influence the sensory properties of the final product [85,86].

This beverage contains a wide range of amino acids, essential minerals, and vitamins, whose quantities depend on the quality of the milk used as the substrate, the preparation method, and the specific microorganisms present in the kefir grains [87,88,89]. For example, the vitamin contents (mg/100 g) in kefirs produced from cow, ewe, goat, and mare milks were 0.019, 0.057, 0.044, and 0.043 (B1); 0.151, 0.128, 0.059, and non-detectable (B2); 0.090, 0.261, 0.218, and 0.182 (B3); 0.449, 0.316, 0.364, and 0.450 (B5); 0.021, 0.030, 0.066, and 0.013 (B6); 1.35, 0.59, 1.22, and 0.19 (B7); 3.96, 4.30, 3.69, and 2.23 (B9); 0.27, 0.46, 0.17, and 0.27 (B12); and 5.97, 0.94, 1.29, and 0.07 (B13), respectively [90]. On the other hand, the contents (mg/100 g) of vitamins A, E, B1, B2, B3, B6, and C in goat kefir samples ranged From 2.82 To 6.52, 0.025–0.198, 0.041–0.047, 0.116–0.193, 0.239–0.244, 0.029–0.038, and 1.88–2.29, respectively, whereas cow milk kefir exhibited values of 3.56, 0.034, 0.052, 0.151, 0.159, 0.024, and 0.13, respectively [87].

Turker et al. [91] comparatively characterized the mineral composition of goat and cow milk kefirs. The results showed that both kefirs contained (mg/L), respectively, 1793.0 and 1674.5 (calcium), 1354.4 and 1265.8 (phosphorus), 1117.5 and 1016.5 (potassium), 395.4 and 342.3 (sodium), 175.8 and 111.3 (magnesium), 1.9 and 3.5 (copper), 3.2 and 18.1 (iron), and 4.6 and 6.9 (zinc). Similarly, the mineral contents (mg/100 g) in goat kefir samples ranged from 120.5 to 140.8 (calcium), 27.2–35.1 (sodium), 153.3–202.1 (potassium), 13.5–16.1 (magnesium), 93.8–114.6 (phosphorus), 0.14–0.52 (iron), 0.02–0.04 (copper), 0.50–0.76 (zinc), 2.12–2.50 (manganese), and 0.011–0.027 (selenium). In comparison, the contents (mg/100 g) of calcium, sodium, potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, iron, copper, zinc, manganese, and selenium in cow milk kefir were 104.2, 31.7, 143.3, 10.5, 80.9, 0.27, 0.02, 0.46, 1.51, and 0.011, respectively [87].

Regarding amino acid composition, milk kefir has been reported to contain (mg/100 mL): 0.03 (aspartic acid), 1.30 (threonine), 0.48 (serine), 6.21 (glutamic acid), 0.63 (glycine), 1.04 (alanine), 1.01 (valine), 0.09 (methionine), 0.88 (isoleucine), 1.04 (leucine), 0.53 (tyrosine), 0.52 (phenylalanine), 0.67 (lysine), 1.07 (histidine), 0.10 (arginine), and 5.31 (proline) [92]. According to Setyawardani et al. [93], the amino acid content (mg/100 g) in milk kefir was 0.36 (aspartic acid), 0.16 (threonine), 0.20 (serine), 1.09 (glutamic acid), 0.09 (glycine), 0.19 (alanine), 0.28 (valine), 0.09 (methionine), 0.22 (isoleucine), 0.44 (leucine), 0.15 (tyrosine), 0.19 (phenylalanine), 0.11 (histidine), 0.39 (lysine), and 0.10 (arginine).

Milk kefir is characterized by its mildly acidic taste, creamy texture, and distinctive flavor, which result from various fermentation by-products, including lactic acid, acetic acid, ethanol, CO2, and aromatic compounds such as acetaldehyde and acetoin [23].

In contrast, water kefir is a kefir-like beverage that is sour, slightly alcoholic, and fruity. It is produced through the fermentation of a sugary substrate containing sucrose, a slice of lemon or fresh ginger, dried fruits or dates, and a pinch of NaCl, using water kefir grains [53,94,95]. Alternatively, other substrates, including fruit or vegetable juices, can also be used to produce this type of beverage [25,28,29,30,31,38].

Water kefir is typically characterized by a hazy, slightly viscous consistency; a blond to yellowish color; a uniform, effervescent texture; an acidic flavor (containing approximately 2% lactic acid); a mild yeasty note (with less than 1% alcohol); and a subtle hint of sweetness. It is also rich in B-complex vitamins (B2, B6, B7, and B12), amino acids, glucose-containing polysaccharides such as glucans and levans, and essential minerals including calcium, copper, sodium, and magnesium, all of which play important roles in supporting human health [24,25].

As fermented beverages, the physical properties, as well as the chemical, microbiological, and aromatic profiles of kefir and kefir-like beverages depend on the type and composition of the substrate, the type and amount of the inoculum, and the fermentation conditions employed [39,89,96,97,98]. For example, the viscosities of full-fat UHT cow’s milk samples inoculated with 1% or 5% (w/w) kefir grains and incubated for 24 h were 425 and 501 mPa·s, respectively [89]. Additionally, the viscosities of kefir produced from cow’s milk incubated with milk kefir grains (2%, w/v) or a natural kefir starter culture (3%, w/v) for 22 h were 225.0 and 312.7 mPa·s, respectively [97].

Another study showed that the viscosities (measured at 50 s−1) of kefir produced from goat’s milk incubated with a freeze-dried kefir starter culture (0.01%, w/v) for 11 h or with milk kefir grains (2%, w/v) for 21 h were 80.0 and 60.0 mPa·s, respectively [98]. However, the addition of polymerized whey protein and low-methoxyl pectin to the goat’s milk increased the viscosity of the beverages fermented with milk kefir grains or with the kefir starter culture to 170.0 and 130.0 mPa·s, respectively.

Similarly, Sabokbar et al. [39] observed that the viscosity of an apple juice– and whey-based novel beverage inoculated with different amounts of milk kefir grains (2–8%, w/v) and incubated at various fermentation temperatures (20–30 °C) ranged from 1.55 to 2.33 mPa·s. The maximum viscosity (2.33 mPa·s) was obtained at 25 °C with 8% (w/v) kefir grains, compared with the unfermented substrate (1.44 mPa·s). This positive effect of specific fermentation conditions on kefir viscosity appears to be related to the production of kefiran, a viscous exopolysaccharide produced by the microflora present in kefir grains [39].

This observation is supported by the findings of Ismaiel et al. [96], who examined the production of milk kefir beverages under various fermentation conditions, including incubation time (1–10 days), initial substrate pH (2.0–9.0), temperature (15–50 °C), kefir grain/substrate ratio (1–10%, w/v), and agitation (static or 50–250 rpm). The resulting beverages were compared in terms of final pH, titratable acidity, viscosity, biomass (dry weight), and lactic acid and kefiran contents. Notably, the conditions that yielded the highest kefiran production (5 days, initial pH 6.0, 30 °C, 5% initial MKGW, static) were also those that resulted in the highest viscosity [96].

Unlike yogurt, kefir grains can be recovered after fermentation, and their biomass gradually increases throughout the process [58]. In recent years, the production of kefir-like beverages using various substrates—including animal and plant-based milks, food by-products such as whey and honey, as well as vegetable and fruit juices—has been investigated (Table 2).

Table 2.

Examples of substrates, fermentation conditions, and maximum yields of ethanol and organic acids during the production of various dairy and non-dairy kefir-like beverages without optimization studies.

5. Characteristics of Kefir Production

Kefir production involves a complex fermentation process influenced by several operational parameters, including temperature, the type and amount of inoculum (milk or water kefir grains, or microorganisms—mainly lactic acid bacteria and yeasts—isolated from these grains), fermentation time, agitation, and the type and initial composition of the substrate (Table 3).

However, the effects of these parameters on kefir fermentation are considerably more complex than those observed in pure-culture fermentations of bacteria or yeasts [29,96,110,111,112], owing to the heterogeneous microbiota present in kefir grains. Careful optimization of these operational factors is therefore essential to enhance microbial biomass production and viability, promote the synthesis of key metabolites (e.g., organic acids, ethanol, antimicrobial compounds, and exopolysaccharides such as kefiran, dextran, and levan), and ensure desirable sensory and nutritional properties in the final kefir-like beverage.

5.1. Fermentation Parameters

The influence of several fermentation parameters—such as temperature, initial pH, substrate concentration, inoculum amount, agitation rate, and fermentation time—on kefir production has been investigated both collectively, using response surface methodology (RSM), and independently, through the one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) approach (Table 3).

When using a substrate of defined chemical composition (e.g., milk or plant- and fruit-based juices), the main variables influencing fermentation include incubation temperature, inoculum type and concentration (milk kefir grains, water kefir grains, or microorganisms isolated from them), agitation, and fermentation time [29,30,31,106].

5.1.1. Fermentation Temperature

Kefir-like beverages have been produced at either unspecified room temperatures or defined incubation temperatures typically ranging from 20 °C to 25 °C (Table 2 and Table 3). Few studies, however, explicitly justify their choice of temperature.

Temperature directly affects the metabolic activity of the key microbial groups present in kefir grains—lactic acid bacteria (LAB), acetic acid bacteria (AAB), and yeasts. The optimal temperature for the growth and metabolism of these microorganisms varies depending on species and strain. For example, LAB grow optimally between 15 °C and 45 °C [113,114], AAB thrive at 25–35 °C [115], and most laboratory and industrial yeasts exhibit maximum growth between 20 °C and 30 °C [116,117,118,119,120]. Consequently, defining a single “optimal” temperature for all three microbial groups often requires a compromise.

The broad overlap in the optimal growth ranges of LAB and yeasts [113,114,116,117,118,119,120]—both recognized for their probiotic potential [3]—encompasses the range commonly referred to as room temperature in scientific and industrial contexts (20 °C ± 5 °C) [121]. Moreover, the lower limit of the optimal temperature range for AAB growth (25 °C) coincides with the upper boundary of typical room temperature [115]. These biological compatibilities, together with traditional and cultural practices [122], likely explain why room temperature is widely used for both kefir grain activation and substrate fermentation (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 3.

Examples of the effects and optimal values of culture variables on microbiological, physicochemical, and functional characteristics in kefir and kefir-like beverage production were determined using optimization experiments (response surface methodology or the one-variable-at-a-time approach).

Table 3.

Examples of the effects and optimal values of culture variables on microbiological, physicochemical, and functional characteristics in kefir and kefir-like beverage production were determined using optimization experiments (response surface methodology or the one-variable-at-a-time approach).

| Substrate and Inoculum | Culture Variables | Dependent Variables | Optimal Conditions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kiwifruit juice and MKG | A = 25–147 rpm; MKGW = 0.79–2.81 g/60 mL substrate; three MKGP transferred into fresh juice every 24 h | TSc, CAc, and QAc; LAB, AAB, and Y; X, LA, AA, EtOH, GOH; AntA | TSc: 125 rpm; 2.81 g MKGW, 3rd MKGP; CAc: 147 rpm; 2.04 g MKGW, 1st MKGP; QA): 147 rpm; 2.13 g MKGW, 1st MKGP; LA): 25 rpm; 1.80 g MKGW, 2nd MKGP; AAB: 147 rpm; 1.80 g MKGW, 1st MKGP; Y: 147 rpm; 1.80 g MKGW, 3rd MKGP; X: 147 rpm; 1.80 g MKGW, 3rd MKGP; LA: 128 rpm; 2.81 g MKGW, 1st MKGP; AA: 147 rpm; 2.81 g MKGW, 3rd MKGP; EtOH: 76 rpm; 2.81 g MKGW, 3rd MKGP; GOH: 147 rpm; 1.80 g MKGW, 3rd MKGP; AntA: 132 rpm; 2.68 g MKGW, 3rd MKGP | [29] |

| Pumpkin (C. pepo) puree and 5% (w/v) WKG | PP: 20–30% (w/v); BS: 0–10% (w/v); T = 22–32 °C | FTpH4.5, OA, EtOH, Lb, AAB, Y | Lowest FTpH4.5: PP 30%, BS 5%, 32 °C; OA: PP 20%, BS 10%, 27 °C; EtOH: PP 30%, BS 10%, 27 °C; Lb: PP 25%, BS 10%, 32 °C; AAB: PP 30%, BS 5%, 32 °C; Y: PP 30%, BS 5%, 32 °C | [32] |

| Lentil flour and 5% (w/v) WKG | T = 20–36 °C; A = 0–150 rpm; t = 0–12 h | TAA | 28 °C, 75 rpm, 4 h | [33] |

| Concentrated apple juice diluted with whey to 14 °Bx (pasteurized at 60 °C/30 min) and MKG | T = 17.93–32.07 °C; MKGW = 0.76–9.24% (w/v); t = 48 h | Final pH, Ac, [Kef], LA, V, Lb, YC, OA | Lowest final pH, highest Ac, LA, highest V, Lb, and Y: 25 °C and 9.24% MKGW; [Kef]: 20 °C and 8.0% MKGW; OA: 25 °C, 5% MKGW | [39] |

| Date whey-based substrate and MKG | DS = 0–50% (w/v); WP = 0–5% (w/v); MKGW = 2–5% (w/v); T = 25 °C; t = 24 h | Final pH, LAB, Y, TPC, TAA, OA | DS: 36.76%, WP: 2.99%, and MKGW: 2.08% for all response variables | [40] |

| * Pasteurized skimmed cow milk and MKG | T = 15–50 °C; initial MKGW = 1–10% w/v; A = 0–250 rpm; t = 1–10 d; initial pH 2–9 | Ac, MKGW, LA, [Kef], V | Ac and LA: 6 d, initial pH 5.5, 35 °C, 4% initial MKGW, static conditions; MKGW, [Kef], and V: 5 d, initial pH 6.0, 30 °C, 5% initial MKGW, static | [96] |

| UHT full-fat cow milk and 4.2% (w/v) MKG | T = 25–43 °C; A = 0–160 rpm; carbon sources (G, F, Suc, and Lact); nitrogen sources (Trypt, ME, NH4Cl, and NH4NO3); vitamins (YE, C, B1, and B3); minerals (KCl, CaCl2, FeCl3, MgSO4); t = 24 h | MKGW, [Kef] | MKGW: 37 °C, 80 rpm; Lact; Trypt; no added vitamins and minerals; [Kef]: 25 °C, 80 rpm; Lact; no nitrogen source; B1; FeCl3 | [110] |

| UHT skim milk and 4.5% (w/v) MKG | T = 20–32 °C; A = 100–200 rpm or magnetic stirring; t = 4–72 h, carbon source (G, G:Gal mixture, Lact, G:Suc); nutrients (MgSO4·H2O:MnSO4·H2O), Trypt, YE, B-complex | MKG growth rate | 25 °C, 24 h, 125 rpm, no nutrient addition | [111] |

| Whey and 4.2% (w/v) MKG | Carbon source (G, Gal, Lact, and Suc): 5–20% (w/v); T = 25–35 °C; A = 50–90 rpm; t = 12–36 h | [Kef] | 15% G, 30 °C, 10 h, static | [112] |

| * High temperature pasteurized full-fat cow milk and 4.2% (w/v) MKG | T = 15–31 °C; A = 60 rpm (1 min every h); t = 24 h | MKGW, EtOH, Lb, St, Y | MKGW and EtOH: 31 °C; Lb: 27–31 °C; St: 19 °C; Y: 25 °C | [123] |

| UHT bovine milk and MKG | Fat = 0–3.5% (w/w); MKGW = 1–7% (w/w); T = 22 °C; t = 22 h | Final pH, Lc, Lb, Y | Lowest pH: 3.5% fat, MKGW = 7%; Lc: 0% fat, MKGW = 1%; Lb: 0% fat, MKGW = 7%; Y: 1.5% fat, MKGW = 7% | [124] |

| Cheese whey and MKG | Lact = 20–100 g/L; YE = 0–24 g/L; initial pH = 3.5–7.5; T = 15–35 °C; t = 120 h | MKGW | 88.4 g Lact/L, 21.3 g YE/L, initial pH: 5.2, 20 °C | [125] |

| Skim milk and MKG | Skim milk = 23.2–56.8% (w/v); T = 21.6–38.4 °C; MKGW = 0.32–3.68% (w/v); t = 16–24 h; A = 0–150 rpm | MKGW | 41.6% skim milk; 30 °C, 1.86% MKGW, 20 h, static | [126] |

| Whey (5% (w/v) lactose) enriched with additives and 1.5% (w/v) MKG | T = 17–37 °C; MKGW = 2.5–7.5% (w/v); t = 24 h | MKGW | 27 °C, 5.0% MKGW | [127] |

| Full-fat milk and 2.0% (w/v) MKG | T = 25–35 °C; five MKGP into fresh milk every 24 h | MKGW | 25 °C, fifth MKGP | [128] |

| Goat milk and 5% (v/v) milk kefir starter | Room temperature or 37 °C; t = 24 or 48 h | LA, final pH, V | LA and V: 37 °C, 48 h; lowest pH: room temperature, 48 h | [129] |

| Reconstituted whole milk (10%, w/v), pasteurized (90 °C/20 min) and 0.07% (w/v) CLKC | T = 17 or 32 °C; P = 0.1–50 MPa; t = 28 h | Fermentation rate, Ac, LA, AA | Faster fermentation rate and Ac: 32 °C, 15 MPa; LA and AA: 32 °C, 0.1 MPa | [130] |

| Full-fat and skim milk and 10% (v/v) MKG | Milk type (NFM or FFM); T = 25 or 37 °C; A = 0 or 80 rpm; t = 24–120 h | [Kef] | FFM, 37 °C, 80 rpm, 48–120 h | [131] |

| Pasteurized (63 °C/30 min) camel milk and MKG | MKGW = 2–10% (w/v); T = 25 °C; t = 18 h | Final pH, Ac, V, fat, protein, Lact, LAB, Y | Lowest pH and highest Ac, V, and protein at 10% MKGW; Lact, fat, and LAB and yeast counts unchanged | [132] |

* Pasteurization conditions not specified. Abbreviations: A, agitation speed; AA, acetic acid produced; AAB, acetic acid bacteria counts; Ac, acidity; AntA, antibacterial activity; BS, brown sugar; CAc, citric acid consumed; CLKC, commercial lyophilized kefir culture; DS, date syrup; EtOH, ethanol; F, fructose; FFM, full-fat milk; FTpH4.5, fermentation time to pH 4.5; G, glucose; Gal, galactose; GOH, glycerol; [Kef], kefiran concentration; KGM, kefir grain mass; LA, lactic acid; LAB, lactic acid bacteria; Lact, lactose; Lb, lactobacilli; Lc, lactococci; ME, meat extract; MKGP, milk kefir grain passage; MKGW, milk kefir grain weight; NFM, non-fat milk; OA, overall acceptability; PP, pumpkin purée; QAc, quinic acid consumed; St, streptococci; Suc, sucrose; T, temperature; TAA, total antioxidant activity; TPC, total phenolic content; Trypt, tryptone; TSc, total sugars consumed; V, viscosity; WKG, water kefir grains; WP, whey permeate; X, biomass; Y, yeast counts; YE, yeast extract.

Using room temperature fermentation also offers practical advantages: it eliminates the need for active heating or cooling systems, thereby lowering production costs and simplifying equipment requirements. Before being used as starter cultures for fermenting various substrates, kefir grains are generally activated at room temperature, which effectively supports the growth and reactivation of LAB, AAB, and yeasts [16,106,133].

Several studies have examined the effects of both moderate (room temperature or approximately 15–37 °C) and elevated (37–50 °C) incubation temperatures on fermentation performance and on the microbiological, chemical, and functional characteristics of kefir (Table 3). However, investigations specifically addressing the influence of temperature on the individual growth dynamics of LAB, AAB, and yeasts within the kefir grain microbiota remain limited [39,123,124].

Available data (Table 3) indicate that maximum lactobacilli counts are typically achieved within the 27–32 °C range, both in traditional milk kefir [123] and in kefir-like beverages derived from apple juice, whey [39], and pumpkin-based substrates [32]. In contrast, lactic streptococci show peak growth at lower temperatures, around 19 °C [123], while AAB populations reach their highest levels at approximately 32 °C [32]. Regarding yeasts, maximum growth has been reported at either 25 °C [39,123] or 32 °C [32], depending on the substrate type and composition.

When kefir-like beverages are produced at room temperature (approximately 20 °C), the viable counts of LAB are generally similar to or even higher than those of yeasts, depending on the composition of the culture medium [30,31,92,102,134,135]. Both microbial groups demonstrate robust growth at 20–25 °C, attaining viable cell concentrations exceeding 107 CFU/mL, the minimum threshold generally considered necessary to confer beneficial probiotic effects [105,136,137].

An illustrative study by Tzavaras et al. [135] evaluated kefir production over 20 consecutive fermentation cycles (each lasting 24 h) using high-heat-treated long-life milk inoculated with kefir grains from the previous cycle. Fermentations were conducted under three temperature regimes: nine cycles at 25 °C, six at ambient temperature (19–26 °C), and five at 20 °C. While the highest sugar consumption occurred at 25 °C, no significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed among beverages produced at different incubation temperatures with respect to lactate, acetate, or ethanol production. Final LAB counts remained comparable across all temperatures, although yeast populations were slightly lower at 25 °C. These findings highlight the adaptive metabolic behavior of the kefir microbiota, which maintains consistent fermentation performance across a relatively broad temperature range.

Given the complex symbiotic interactions among LAB, AAB, and yeasts, identifying a single “optimal” temperature for kefir production is challenging. Instead, incubation temperature should be selected based on the desired characteristics of the final product, including microbiological balance, chemical composition, volatile profile, sensory properties, and technological constraints.

5.1.2. Type and Amount of Inoculum Used

As shown in Table 2 and Table 3, heterogeneity among studies investigating the effects of various factors on specific response parameters in kefir-like beverage production prevents definitive conclusions for process optimization.

Regarding the inoculum, substrates have been inoculated with microorganisms isolated from water or milk kefir grains [100,130], as well as with whole milk kefir grains [28,29,38,96,106,107,126,138,139] or whole water kefir grains [32,94,140,141]. The weight of kefir grains increases during successive subculturing in milk due to the proliferation of the microorganisms embedded within the matrix and the synthesis of kefiran [58].

Studies investigating the effect of kefir grain quantity have used widely varying inoculum levels and response variables, making direct comparisons challenging. For example, Ismaiel et al. [96] examined the influence of initial kefir grain weight (KGW) on titratable acidity, kefir biomass, and concentrations of lactic acid and kefiran. Gao et al. [126] and Apar et al. [127] focused exclusively on kefir grain biomass growth, whereas Magra et al. [124] measured final pH and microbial counts—specifically lactococci, lactobacilli, and yeasts. Sabokbar et al. [39] assessed KGW effects on pH reduction, acidity, microbial counts, kefiran and lactic acid concentrations, viscosity, and overall sensory acceptability. Bazán et al. [29] evaluated the combined effects of agitation speed and KGW on 12 response variables, including sugar and organic acid consumption, LAB, AAB, and yeast counts, production of free biomass, lactic acid, acetic acid, ethanol, glycerol, and antibacterial activity (Table 3).

These studies demonstrate high variability in the optimal amount of kefir grains required for a given response variable, indicating that outcomes depend on the type of kefir grains, substrate composition, and incubation time. For instance, maximum kefir grain biomass growth was observed when the substrate was inoculated with 5.0% (w/v) KGW at an initial pH of 6.0 and incubated at 30 °C for 5 days [96]. Similarly, Apar et al. [127] reported enhanced biomass growth when initial kefir grain concentration increased from 2.5% to 5.0% in enriched whey after 24 h of fermentation, whereas a further increase to 7.5% reduced growth. Gao et al. [126] found an optimal KGW of 1.86% (w/v) for maximum growth of Tibetan kefir grains during 20 h; both lower (1% w/v) and higher (3% w/v) inoculum levels resulted in reduced growth rates.

Higher inoculum amounts increase the initial microbial load, leading to rapid nutrient depletion, which limits kefir grain growth and metabolic activity and reduces kefiran production. Thus, the inhibitory effect of increasing KGW has been attributed to substrate limitation [89,127].

Some studies report that increasing KGW enhances LAB and yeast growth and lactic acid production [39,40,142,143], whereas others observed no significant differences across different inoculum levels [132]. Bazán et al. [29] found that increasing KGW to 3% (w/v) enhanced microbial growth in kiwi juice, but further increases likely led to excessive microbial migration, intensified nutrient competition, and accumulation of inhibitory metabolites such as ethanol, glycerol, lactic acid, acetic acid, and bacteriocins. These findings underscore that the relationship between KGW and microbial activity depends on specific experimental conditions.

The microbial composition of starter cultures derived from microorganisms isolated from water or milk kefir grains, as reported in various studies, typically consists of declared or undeclared proportions of LAB and yeast strains. For example, one starter culture isolated from milk kefir grains contained approximately 109 CFU/g LAB, including Lb. fermentum (Acc. No. KT633923), Lb. kefiri (Acc. No. KT633919), L. lactis (Acc. No. KT633921), and Leuc. mesenteroides (Acc. No. KT633927), along with the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Acc. No. KT724951) [30,31]. In contrast, other starter cultures derived from milk kefir grains contained undeclared microbial counts but were reported to include LAB belonging to the genera Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, Lactobacillus [100,130], and Streptococcus [130]. The yeast components of these cultures comprised strains of the genera Kluyveromyces [100,130] and Saccharomyces [130].

Compared with the complex and diverse microbiota present in whole milk and water kefir grains—which naturally consist of interacting populations of LAB, AAB, and yeasts—these isolated starter cultures display markedly reduced microbial diversity. Consequently, beverages produced using such simplified cultures should not be considered true kefir, as they lack the intricate metabolic interactions and synergistic activities inherent to whole-grain fermentation systems.

5.1.3. Agitation Speed

The use of different agitation speeds during the production of kefir-like beverages has yielded contradictory results, both regarding the necessity of agitation and the identification of optimal agitation rates. For instance, incubation without shaking has been reported as the most favorable condition for producing certain kefir-like beverages [96]. In contrast, other studies have demonstrated that agitation is essential for enhancing kefir biomass growth [74,111], organic acid production [74], total antioxidant activity [33], and kefiran concentration [131]. Agitation has also been associated with increased consumption of total sugars, citric acid, and quinic acid, as well as higher counts of AAB and yeasts, and greater production of free biomass, lactic acid, acetic acid, ethanol, glycerol, and antibacterial compounds in the fermented beverage [29].

Similarly, Güzel-Seydim et al. [144] reported that agitation speeds between 75 and 100 rpm were required to stimulate the growth of LAB and yeasts in whole milk. Conversely, Blandón et al. [112] observed that increasing the agitation speed from 60 to 90 rpm significantly reduced kefir grain growth, although this change did not notably affect kefiran production in whey. High agitation speeds may also exert detrimental effects, as demonstrated by Bazán et al. [29], who found that agitation beyond the optimal level negatively impacted LAB counts.

The positive effect of increasing agitation up to its optimal value has been attributed to improved oxygen dissolution in the fermentation medium [145,146]. Enhanced oxygen transfer facilitates cellular oxygen uptake and promotes the exchange of gases and metabolites between the cells and the substrate. However, when agitation speed exceeds the optimal threshold, it can damage microbial cell walls, leading to cell disruption and the release of intracellular components into the fermentation medium [147,148,149].

5.1.4. Fermentation Time

Fermentation time is another crucial variable in the production of kefir-like beverages, as it determines the successful progression of the fermentation process depending on the response variable of interest [106]. Although not always explicitly justified, different fermentation durations—either fixed or within a defined range—are commonly employed in the production of kefir-like beverages (Table 3). When a fixed fermentation time is selected, the purpose is typically to assess the microbiological, chemical, and volatile profiles of the beverages [28,29,30,31,38,106]. In contrast, when a range of fermentation times is used, the aim is to evaluate its impact on specific response variables (Table 3).

For example, kefir-like beverages produced from vegetable juices (carrot, fennel, melon, onion, tomato, and strawberry) [30] or fruit juices (apple, quince, grape, kiwifruit, prickly pear, and pomegranate) [31] were statically incubated with a commercial water kefir microbial preparation for 48 h at 25 °C. Although the authors did not justify this specific duration, it appears to allow higher concentrations of volatile compounds than a 24 h fermentation, as also observed by Bazán et al. [38].

In fermentations of whole milk with kefir grains for 24 or 48 h, the number and total concentration of volatile compounds were either higher or significantly lower than those in unfermented milk [106]. The reduction in volatile compound concentrations in kefir samples has been attributed to their conversion into other volatile molecules [150,151,152]. For example, the oxidation of hydrocarbons leading to methyl ketone synthesis, as well as the enzymatic conversion of aldehydes and ketones into alcohols, has been reported during the fermentation of Thai fermented sausage by a Lactobacillus strain [150]. Additionally, ester hydrolysis at low pH values, the oxidation or esterification of alcohols to form organic acids or esters, and the esterification of organic acids have been described in various fermentation processes [151,152,153].

Bazán et al. [106] further attributed the reduction in volatile compound concentrations in 48 h fermented beverages to overacidification of the milk compared to 24 h kefir. This overacidification promotes increased protein precipitation and coagulation, which facilitates the release of a greater proportion of volatile compounds from the fermented beverage into the air.

5.2. Metabolite Production

Organic Acid and Alcohol Production

As shown in Table 3, organic acid and alcohol concentrations in kefir-like beverages vary widely depending on substrate composition, fermentation conditions, and starter culture. Although kefir grains and their consortia contain high counts of LAB, AAB, and yeasts, the resulting beverages consistently display lower metabolite levels than fermentations with pure cultures [28,29,30,31,42,100,105,106,107,154].

Pure LAB cultures can produce high lactic acid concentrations, e.g., L. lactis ssp. lactis ATCC 19435 (86.0 g/L) in whole-wheat flour [155] or Lb. casei MT682513 (44.9 g/L) in whey permeate [156]. In milk, individual LAB strains yielded 7.33–9.30 g/L lactic acid, with measurable acetic acid only in Leuc. citreum 2BC7 and Lb. paracasei VI-19 [157]. Several yeasts also produced moderate lactic and acetic acid levels, while cocultures (e.g., Leuc. citreum 2BC7 with C. pararugosa 3AD19, or Lb. paracasei VI-19 with Debaryomyces hansenii 3AD24) achieved the highest acid concentrations.

In a three-stage fermentation, Wang et al. [158] demonstrated that ethanol accumulated by S. cerevisiae (48.0 g/L) was subsequently oxidized by Acetobacter pasteurianus CICC7015 to 52.51 g/L acetic acid, illustrating efficient yeast–AAB cross-feeding.

Homofermentative LAB are the primary lactic acid producers via the Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas pathway [159,160] (Figure S1), whereas yeasts generate lactic acid only as a minor by-product [161,162]. Heterofermentative LAB produce lactic acid along with acetic acid, ethanol, and CO2 (Figure S2) [115]. Under glucose limitation or alternative-sugar conditions (e.g., maltose, galactose, lactose), LAB may shift to mixed-acid fermentation, forming ethanol, 2,3-butanediol, acetolactate, acetate, and formate (Figure S3) [163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170]. Such shifts are unlikely in kefir-like beverages, as formate is absent and fruit substrates contain ample sugars [28,29,30,31].

Acetic acid is primarily produced by AAB [115,171] (Figure S4) and heterofermentative LAB [172] (Figure S2). Ethanol and glycerol originate mainly from yeasts [28,30,31,42,99,100,105,106,154,173] (Figure S5), although heterofermentative LAB may also produce ethanol [172]. Some Lactobacillus strains further metabolize lactic acid to acetic acid and CO2 under aerobic or carbohydrate-limited conditions, or to 1,2-propanediol and trace ethanol under anaerobic conditions, via enzymes such as lactate dehydrogenase, lactate oxidase, and pyruvate oxidase [167,169,170,174,175]. AAB can also convert lactate to acetoin or 2,3-butanediol [171,176] (Figure S4).

Certain yeasts—including non-lactose-fermenting Saccharomyces spp., D. hansenii, and C. guilliermondii—can assimilate lactic and/or acetic acid produced by LAB and AAB [81,152,154,177,178]. Some AAB (e.g., Acetobacter, Gluconobacter, Gluconacetobacter) convert glycerol to dihydroxyacetone [171,176] (Figure S4), while heterofermentative LAB may produce lactic acid or 1,3-propanediol via 3-hydroxypropionaldehyde under anaerobic, sugar-limited conditions [179,180].

Together, these findings indicate that lactic acid, acetic acid, and ethanol levels in kefir-like beverages are regulated by metabolic interactions among LAB, AAB, and yeasts, preventing excessive accumulation and supporting microbial community stability [106,172]. Although kefir inocula contain yeasts, ethanol concentrations in the final beverages are often low (Table 3), consistent with ethanol oxidation by AAB to acetic acid [102,152,153,158,171,176,181]. This may also explain ethanol-free beverages, such as chestnut-based kefir [107] or milk kefir [130].

However, this hypothesis does not account for the low ethanol levels observed in fruit- and vegetable-based kefir beverages [30,31], as the commercial water kefir inocula used in those studies lacked AAB strains. Consequently, the variation in ethanol levels among kefir beverages (Table 3) can be attributed primarily to differences in the initial substrate composition.

5.3. Volatile Profile

The sensory profile of foods and beverages destined for human consumption is a key attribute to consider before commercialization, as it is closely linked to their chemical composition, volatile fraction, and sensory evaluation. The volatile profile of fermented beverages is typically complex, comprising numerous compounds that differ between products in both presence and concentration; moreover, the same volatiles are not always detected across all beverages [28,30,31,106,108,120,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189].

Most kefir studies rely on a relatively limited but well-established set of analytical techniques for volatile profiling, primarily headspace extraction coupled with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) or direct-injection mass spectrometry [38,185,190]. Headspace-based extraction is the principal sample-preparation strategy because it minimizes matrix interferences and preserves labile aroma compounds, with the main variants being: static headspace (HS), in which equilibrated sealed vials are sampled from the headspace and injected into GC systems to quantify relatively abundant volatiles such as ethanol, acetaldehyde, and diacetyl; headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME), where a sorbent-coated fiber (e.g., PDMS, CAR/PDMS, DVB/CAR/PDMS) is exposed to the headspace over kefir and then thermally desorbed in the GC injector, currently the most widely adopted technique for volatilome profiling in milk, plant-based, and lactose-free kefirs [38,108,185,191]; and dynamic headspace/purge-and-trap, in which volatiles are stripped with an inert gas and trapped on adsorbent materials that are subsequently thermally desorbed for GC analysis, improving sensitivity for low-abundance aroma compounds in fermented dairy matrices [99].

Solvent-based methods are preferred when the analytical objective is targeted quantification or when semi-volatile compounds must be included [99]. Typical approaches include liquid–liquid extraction (LLE), where kefir is extracted with organic solvents (e.g., dichloromethane, pentane) and the organic phase is analyzed by GC with flame ionization or MS detection for key flavor compounds [99], and solid-phase extraction (SPE) or related sorptive techniques, in which volatiles and semi-volatiles are retained on cartridges or polymeric phases and eluted with small solvent volumes to achieve preconcentration before GC analysis [30,31,61,106,183,184,185]. Gas chromatography is the core separation technique for kefir volatile analysis and is usually coupled with flame ionization or mass spectrometric detection. GC–FID is used for routine, targeted measurements of ethanol, acetaldehyde, diacetyl, acetoin, and selected esters when compound identity is known and accurate quantification is required [99,108]; one-dimensional GC–MS remains the standard platform for comprehensive profiling, enabling identification of a wide spectrum of acids, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, esters, terpenes, and sulfur compounds using retention indices and spectral libraries [30,31,38,106,183,184,185,191]; comprehensive two-dimensional GC (GC × GC–MS) has been used in dairy and fermentate studies to increase peak capacity and resolve coeluting compounds in complex volatilomes, and is applicable to kefir matrices when greater separation is needed [61]; comprehensive two-dimensional GC coupled to time-of-flight MS (GC × GC–TOFMS) employs two columns of different selectivity and a modulator to provide high resolving power, with the first dimension usually separating by volatility and the second adding an orthogonal polarity- or shape-based separation, while TOFMS delivers fast full-scan spectra for detailed characterization of acids, alcohols, esters, ketones, and other metabolite classes in reconstituted kefir consortia and fermented beverages [187,190]; Headspace SPME–GC–TOFMS–FID is a solvent-free, two-step method that first concentrates volatiles from the kefir headspace onto a coated fiber and then separates and detects them by GC with dual detectors, enabling both mapping of the full volatile profile and accurate quantification of key aroma compounds [182].

Selected-ion flow-tube mass spectrometry (SIFT-MS) is a direct-injection technique in which reagent ions (e.g., H3O+, NO+, O2+) react with trace VOCs in a flow tube under controlled conditions, and product ions are measured at specific m/z values; because reaction rate constants are known, this allows real-time, calibration-free quantification of target volatiles, including off-flavor compounds, and has been applied to monitor and mitigate undesirable aroma notes in kefir after processing steps such as freeze-drying or vacuum evaporation [190]. Headspace GC–high temperature ion mobility spectrometry (HS–GC–HTIMS) combines GC separation of VOCs with ion mobility spectrometry at atmospheric pressure, providing rapid, highly sensitive, and largely non-targeted fingerprinting of complex volatilomes; following headspace sampling, VOCs are separated on a GC column, ionized (typically by a soft ionization source), and introduced into a drift tube, where ions are separated according to their mobility in an electric field, yielding two-dimensional data (retention time vs. drift time) suitable for pattern recognition and classification of traditional versus commercial kefirs and related fermented milks [192]. Direct-injection mass spectrometry more broadly enables rapid, often real-time monitoring of kefir volatilomes without chromatographic separation, for example, via proton-transfer-reaction time-of-flight MS (PTR-ToF-MS), which supports online, highly time-resolved volatilome profiling during fermentation by detecting hundreds of m/z features and capturing dynamic changes in VOC release in both milk and cereal-based kefirs, and via other flow-tube-based MS platforms adapted for process control and rapid screening [190].

Post-acquisition data processing is essential to convert instrumental outputs into meaningful descriptions of kefir aroma [38,190]. Volatiles are typically identified and quantified using mass spectra and retention indices compared with commercial libraries and authentic standards, together with internal standards (e.g., 3-octanol) and calibration curves for semi-quantitative or quantitative determinations. Odor activity values (OAVs), obtained by relating compound concentrations to odor thresholds, help identify the main aroma-active components responsible for kefir’s characteristic flavor. Chemometric methods such as principal component analysis, hierarchical clustering, response surface methodology, and other multivariate tools are employed to relate volatile profiles to kefir type, inoculum level, shaking rate, fermentation time, and starter composition, and to integrate volatilome data into broader multi-omic frameworks [38,190,193]. Collectively, these methodological families—headspace-based extraction, solvent-based extraction, GC-based platforms, direct-injection mass spectrometry, and chemometric/sensory integration—constitute the current toolbox for analyzing and interpreting the volatile profile of kefir and kefir-like beverages [38,185,190].

Because different studies use diverse analytical methods and reporting units [28,30,31,106,108,120,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189], direct comparison of absolute concentrations of individual volatile compounds across fermented beverages is challenging. In this context, focusing on the occurrence and relative importance of major chemical families—such as organic acids, alcohols, aldehydes, esters, and ketones—may be more informative than comparing individual compound concentrations alone.

The volatile profile of kefir and kefir-like beverages is broadly similar in terms of chemical families (organic acids, alcohols, aldehydes, esters, ketones), but their relative abundance and sensory impact differ because of the substrate (milk vs. fruit/vegetable juices) and the activity of the kefir microbiota [30,31,38].

5.3.1. Volatile Organic Acids

In traditional milk kefir, volatile organic acids such as acetic, propionic, butyric, and pyruvic acids arise primarily from lactose fermentation by heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and citrate metabolism by acetic acid bacteria and yeasts, with acetic acid often dominating and contributing a sharp, vinegary note to the profile. Levels vary with milk type (e.g., higher acetic and succinic acids in organic milk kefir) and fermentation conditions, but total volatile acids typically range from 0.1 to 0.2 g/kg. In kefir-like beverages from fruits (e.g., grape, kiwi) or vegetables (e.g., carrot, tomato), fermentation elevates total organic acids beyond baseline levels, with acetic acid consistently present across substrates and novel acids (e.g., isovaleric) emerging de novo, though some like 4-methylpentanoic acid may disappear due to microbial consumption [30,31,38,99,184,194].

5.3.2. Volatile Alcohols

Milk kefir features higher alcohols like ethanol (often >1% v/v), 1-propanol, 2- and 3-methyl-1-butanol, and phenylethanol, produced mainly by yeasts via amino acid catabolism (Ehrlich pathway) and sugar fermentation, imparting fusel, malty, and solvent-like aromas that increase during extended fermentation. Ethanol dominates, reflecting yeast-LAB symbiosis. In fruit- and vegetable-based kefir-like beverages, fermentation boosts total alcohols beyond those in raw matrices (e.g., hexanol, benzyl alcohol from plants), though pH influences yields—e.g., 1.38-fold higher at pH 5.99 vs. 3.99 in grape kefir—due to modulated yeast activity amid LAB and acetic acid bacteria interactions [28,38,99,190,194].

5.3.3. Volatile Aldehydes

Volatile aldehydes form primarily through amino acid transamination, Strecker degradation, glycolytic reactions [195], and lipid metabolism [183]. Because of their high chemical reactivity, these compounds are transient intermediates that tend to be further reduced to alcohols or oxidized to fatty acids as fermentation proceeds [120].

Milk kefir typically contains aldehydes such as acetaldehyde, hexanal, and Strecker aldehydes formed from amino acid and lipid metabolism; these compounds are often transient and can decrease over time as they are reduced to alcohols or oxidized to acids. In kefir-like beverages, aldehydes from the fresh plant material (e.g., hexanal, (E)-2-hexenal, benzaldehyde) are prominent at the start and may be partially transformed during fermentation, so their persistence or disappearance reflects both the initial matrix and the specific kefir consortium [38,99,184,190].

5.3.4. Volatile Esters

Esters are highly volatile molecules that play a crucial role in shaping the aroma of fermented beverages, often imparting pleasant fruity and floral notes due to their low odor thresholds [195]. They are commonly generated through carbohydrate metabolism [183] or by esterification between alcohols and organic acids [195]. Therefore, in kefir-type beverages, the final concentration of volatile organic acids reflects the combined influence of pre-existing acids in the raw material, those newly synthesized during fermentation, and the fraction consumed in ester production.

In kefir, esters (e.g., ethyl acetate, ethyl butyrate, isoamyl acetate, and ethyl hexanoate) are produced by yeast and bacterial esterification of organic acids with alcohols, imparting fruity and floral notes that can soften the acidic profile of fermented milk. In kefir-like beverages, ester formation is often more pronounced because of the richer pool of precursor alcohols and acids in fruit and vegetable juices, leading to more complex fruity aromas and, in some cases, appearance of esters not detected in the unfermented substrates [38,99,184,194].

5.3.5. Volatile Ketones

Ketones, known for their sharp and distinctive aromas, contribute notably to the sensory character of fermented beverages. Their occurrence in kefir-like drinks is primarily linked to carbohydrate and lipid metabolism [183] and to the decarboxylation or oxidation of fatty acids, sugars, and amino acids by LAB [196,197]. Consequently, their final concentration after fermentation represents both the residual amount from the starting substrate and the portion newly produced during microbial activity.

Milk kefir typically contains ketones such as acetoin and 2,3-butanedione (diacetyl) and acetoin from citrate–lyase pathways in LAB (e.g., Lactococcus, Leuconostoc), delivering buttery, creamy sensations at optimal concentrations, with levels increasing over fermentation time. In kefir-like beverages, ketones can also form from carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, but their relative contribution to aroma is often lower than in milk kefir because fruity esters and plant-derived aldehydes and alcohols dominate the sensory profile [38,99,184,190].

6. Advances and Future Challenges in the Production of Kefir-like Beverages

Recent advances in the production of kefir-like beverages have significantly expanded the range of functional products available to consumers, yet several challenges remain to be addressed for further progress. The chemical, microbiological, and volatile profiles of these beverages have been extensively studied [28,29,30,31,38], but continued innovation and optimization are essential to ensure consistent quality, safety, and health benefits.

A major trend in kefir-like beverage development is the incorporation of functional additives such as plant extracts, fruit pulps, soy milk, agro-industrial by-products, essential oils, and prebiotics like inulin. These additions not only enhance the health-promoting properties of the beverages but also diversify their sensory profiles [198,199]. The growing demand for plant-based options has led to the use of non-dairy substrates such as soy, almond, coconut, oat, and rice milks, which are fermented with either traditional kefir grains or selected starter cultures [55,92,142,200]. Nutrient fortification with calcium and vitamins B12 and D3 helps to approximate the nutritional profile of dairy kefir, making these alternatives particularly appealing to health-conscious consumers [201,202]. Moreover, plant-based kefir production often utilizes agricultural by-products, thereby supporting more sustainable food systems and reducing environmental impact. The inclusion of plant extracts and by-products in kefir fermentation can improve the volatile compound profile, probiotic activity, and sensory acceptance, while also mitigating undesirable plant-derived odors [203,204,205].

Producing plant-based kefir-like beverages offers several advantages over traditional milk kefir, as highlighted in recent scientific literature. Plant-based kefir alternatives are suitable for individuals with lactose intolerance, dairy allergies, or those adhering to vegan diets, thereby reaching a wider consumer base. These beverages can be produced from substrates such as apricot seed extract, soy, oat, and coconut milk, which provide diverse nutritional profiles and bioactive compounds, including higher antioxidant and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory (ACE-i) activities than those reported for milk kefir [203,205,206]. From a health perspective, plant-based kefir beverages have demonstrated probiotic properties, immune-modulatory effects, and the capacity to generate bioactive compounds such as exopolysaccharides, peptides, and organic acids, comparable to their dairy counterparts. The versatility of substrate selection and the potential for targeted fortification make plant-based kefir a promising strategy for expanding functional food offerings while simultaneously addressing health, ethical, and environmental concerns [203,205,206].

Advances in genomic and metagenomic technologies have provided deeper insights into the complex microbial networks within kefir grains, enabling the identification and targeted manipulation of beneficial strains. This knowledge opens the door to engineering microbial consortia for tailored fermentation processes, resulting in beverages with specific flavor profiles, enhanced probiotic functions, and improved stability [56,207,208]. Strains isolated from kefir have demonstrated notable probiotic properties, including antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and gut-modulating effects in both laboratory and clinical studies [24,49,88,105]. Kefir-like beverages are also characterized by low levels of alcohol, sugars, and acids, as well as the presence of bioactive compounds such as peptides, exopolysaccharides (notably kefiran), and bacteriocins, all of which contribute to their health-promoting potential [25,28,29,85,105].

Technological innovations, such as the immobilization of kefir grains on inert supports, have improved their reusability and facilitated better control over fermentation processes [209,210,211,212]. The integration of smart bioreactors and real-time pH/redox monitoring systems is further enhancing process consistency and the quality of commercial production [213,214,215].

Despite these advances, the production of kefir-like probiotic beverages faces several challenges. Ensuring reproducibility in technological processes is critical for delivering products with consistent microbiological, chemical, and volatile profiles. An ideal kefir-like beverage should contain viable microbial populations (mainly LAB and yeasts) above the minimum threshold (106–107 CFU/mL or g) required for probiotic effects, exhibit a favorable chemical profile with low sugar and ethanol content, and display a complex volatile profile derived from substrate, fermentation, and maturation processes. Achieving these targets requires careful optimization of fermentation parameters such as inoculum size, incubation temperature, and agitation speed.

Standardization and quality control remain significant hurdles, as natural kefir grains can vary widely in microbial composition, making batch-to-batch consistency difficult to achieve. Maintaining probiotic viability and functionality during processing, storage, and distribution is technically demanding, and high production costs can limit market accessibility and affordability. Regulatory and labeling considerations are also important, particularly in international markets where health claims require robust scientific substantiation, and the use of the term “kefir” for plant-based products raises nomenclatural and regulatory questions.

Looking ahead, opportunities exist for integrating kefir production with personalized nutrition strategies, leveraging nutrigenomics and individual microbiome profiling to create tailored fermented beverages for specific health needs. Additionally, adopting a circular economy approach—by utilizing agricultural by-products such as okara, whey permeate, or surplus fruits and vegetables as fermentation substrates—can enhance sustainability, reduce food waste, and add value to underutilized materials [2,3,200]. These developments promise to further advance the field and expand the availability of innovative, functional kefir-like beverages.

7. Conclusions

Kefir-like beverages are emerging as a versatile platform for the delivery of probiotics and bioactive compounds. Despite notable advances in fermentation science, microbiology, and food technology, challenges remain regarding standardization, consumer acceptance, and regulatory frameworks. Overcoming these obstacles will require close interdisciplinary collaboration among microbiologists, food technologists, nutritionists, and policymakers.

In parallel, well-structured kinetic studies are essential to deepen our understanding of the complex interactions among LAB, AAB, and yeasts present in kefir grains and kefir-like beverages. Such studies should integrate molecular biology techniques to trace microbial migration from kefir grains into different substrates and to monitor their evolution during fermentation in response to key cultivation variables, including pH, nutrient availability, and the accumulation of metabolic products.

This knowledge will facilitate the development of optimized fed-batch fermentation processes for the sustainable production of kefir-like beverages with functional (probiotic and health-promoting) properties. These processes should ensure strict hygienic standards while maintaining desirable sensory and aromatic characteristics for consumers. Furthermore, these advances will also support artisanal-scale production of kefir-like beverages using natural and/or commercial fruit juices, thereby bridging traditional fermentation practices with modern biotechnological innovations.

Based on the findings presented in this review, our research team is currently investigating the production, characterization, and storage conditions of kefir-like beverages made from various fruit juices. This research aims to generate additional knowledge that will contribute to the development of new kefir-like beverage varieties.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr14010073/s1, Figure S1: Homolactic fermentation by LAB (Reproduced from Axelsson [216]); Figure S2: Heterolactic fermentation by LAB (Reproduced from Axelsson [216]); Figure S3: Mixed acid fermentation by LAB (Reproduced from Cocaign-Bousquet y col. [163]); Figure S4: Degradation of sugars by acetic acid bacteria bacteria (Reproduced from De Vuyst et al. [171] and Arai et al. [217]); Figure S5: Metabolism of glucose by yeast (Reproduced from De Vuyst et al. [171]).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.P.G. and E.B.O.; methodology, N.P.G. and E.B.O.; software, N.P.G. and E.B.O.; validation, N.P.G., E.B.O. and M.A.J.; formal analysis, N.P.G. and M.A.J.; investigation, N.P.G., E.B.O. and M.A.J.; resources, N.P.G. and E.B.O.; writing—original draft preparation, N.P.G., E.B.O. and M.A.J.; writing—review and editing, N.P.G.; visualization, N.P.G., E.B.O. and M.A.J.; supervision, N.P.G.; project administration, N.P.G.; funding acquisition, N.P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work forms part of the activities of the Group with Competitive Reference (GRC-ED431C 2024/24) funded by the Xunta de Galicia (Spain). We thank Adriana Pérez Rey for her assistance in preparing the Graphical Abstract and Figures.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bintsis, T.; Papademas, P. The Evolution of Fermented Milks, from Artisanal to Industrial Products: A Critical Review. Fermentation 2022, 8, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Habsi, N.; Al-Khalili, M.; Haque, S.A.; Elias, M.; Al Olqi, N.; Al Uraimi, T. Health Benefits of Prebiotics, Probiotics, Synbiotics, and Postbiotics. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, D.; Nigam, P.S. Antibiotic-Therapy-Induced Gut Dysbiosis Affecting Gut Microbiota-Brain Axis and Cognition: Restoration by Intake of Probiotics and Synbiotics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannerchelvan, S.; Rios-Solis, L.; Wasoh, H.; Sobri, M.Z.M.; Faizal Wong, F.W.; Mohamed, M.S.; Mohamad, R.; Halim, M. Functional Yogurt: A Comprehensive Review of its Nutritional Composition and Health Benefits. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 10927–10955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comerford, K.B.; Miller, G.D.; Boileau, A.C.; Schuette, S.N.M.; Giddens, J.C.; Brown, K.A. Global Review of Dairy Recommendations in Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 671999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yépez, A.; Russo, P.; Spano, G.; Khomenko, I.; Biasioli, F.; Capozzi, V.; Aznar, R. In Situ Riboflavin Fortification of Different Kefir-like Cereal-based Beverages using Selected Andean LAB Strains. Food Microbiol. 2019, 77, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teijeiro, M.; Pérez, P.F.; De Antoni, G.L.; Golowczyc, M.A. Suitability of Kefir Powder Production using Spray Drying. Food Res. Int. 2018, 112, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IMARC Group. Kefir Market Size, Share, Trends and Forecast by Nature, Category, Product Type, Distribution Channel, and Region, 2025–2033. Available online: https://www.imarcgroup.com/kefir-market (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Future Market Insights Inc. (FMI). Kefir Market Analysis by Form, Category, Application, Distribution Channel, Region and Other Product Types Through 2035. Outline of Important Trends Shaping the Kefir Business Progress. Available online: https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/kefir-market (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Grand View Horizon Inc. Global Kefir Market Size & Outlook, 2025–2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/horizon/outlook/kefir-market-size/global (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Korbekandi, H.; Abedi, D.; Maracy, M.; Jalali, M.; Azarman, N.; Iravani, S. Evaluation of Probiotic Yoghurt Produced by Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. tolerans. J. Food Biosci. Technol. 2015, 5, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sayes, C.; Leyton, Y.; Riquelme, C. Probiotic Bacteria as an Healthy Alternative for Fish Aquaculture. In Antibiotic Use in Animals, 1st ed.; Savić, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; Volume 1; pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallina, D.A.; Menezes Barbosa, P.P.; Celeste Ormenese, R.C.S.; Garcia, A.O. Development and Characterization of Probiotic Fermented Smoothie Beverage. Rev. Ciência Agronômica 2019, 50, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivo, D.; Galván, M.; López-Rodríguez, G.; Suárez-Diéguez, T.; González-Unzaga, M.; Anaya-Cisneros, L.; López-Piña, D. Actividad Biológica y Potencial Terapéutico de los Probióticos y el Kefiran del Grano de Kefir. Rev. Iberoam. Cienc. 2017, 4, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- CXS 243-2003; Codex Alimentarius Commission: Standard for Fermented Milks. FAO: Rome, Italy; WHO: Rome, Italy, 2003; Amended 2022, 2024.

- Chen, H.C.; Wang, S.Y.; Chen, M.J. Microbiological Study of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Kefir Grains by Culture-Dependent and Culture-Independent Methods. Food Microbiol. 2008, 25, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]