Abstract

Biochar has emerged as a promising material for carbon storage, exhibiting properties analogous to those of activated carbon. Biochar has a particularly high absorbance due to its high porosity, surface area, and functional groups, although these parameters depend on the feedstock and pyrolysis conditions. The sorbent properties of biochar make it suitable for many applications, including the biological treatment of organic waste. In the context of composting, biochar addition seems to positively impact the process performance and the final compost characteristics. Furthermore, it reduces greenhouse gas and odor emissions, which is a crucial step in preventing the full implementation of composting. The objective of this review is to provide a comprehensive description of the effects of biochar on composting emissions and the reported mechanisms, highlighting the limitations of current research. In summary, the use of biochar in composting is still in its early stages and requires further research and consensus on fundamental issues, such as the optimal biochar dosage and mitigation mechanisms. Moreover, there is a significant lack of full-scale implementation. Accordingly, future work should focus on overcoming these critical challenges to take a step forward towards a consistent and complete picture of the environmental impacts and a rigorous economic analysis of the use of biochar in composting.

Keywords:

biochar; composting; gaseous emissions; ammonia; greenhouse gases; odors; volatile organic compounds 1. Introduction

In the context of modern organic waste management, strategies based on biotechnological processes are playing an increasingly important role due to their lower environmental impact compared to other physicochemical alternatives [1]. Furthermore, biotechnologies for waste management are directly related to the circular economy, as they involve the valorization of waste into new biodegradable materials or renewable bioenergy [2]. Many of these strategies are also closely related to critical Sustainable Development Goals promoted by the United Nations [3].

Composting and anaerobic digestion, in particular, play a predominant role in today’s overall organic waste management picture [4]. These technologies are implemented worldwide and have seen exponential growth in recent years due to the scarcity of materials and energy from traditional sources. It is also important to highlight that these two approaches are highly complementary [5]. Thus, the increase in anaerobic digestion is focused on methane production; however, it also involves the generation of large quantities of digested materials that are ideal for composting, resulting in a stable, odorless, non-phytotoxic organic amendment for use in sustainable agriculture [6]. Similarly to composting, solid-state fermentation enables the production of added-value bioproducts from organic waste, changing the concept of waste to resource and treatment plants to biorefineries [7].

Apart from the obvious benefits of composting and aerobic treatment of organic waste in general, there are some problems associated with large-scale facilities. Focusing on gaseous emissions, there can be a significant environmental impact due to undesired Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions, such as methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) [8]. In this case, carbon dioxide (CO2) can be considered a biogenic emission given that the organic matter present in the substrate would inherently decompose into CO2. Moreover, other gases are emitted during the composting process that can cause odor nuisance [9]. In the case of ammonia (NH3), excessive release decreases the quality of the compost as an organic amendment and its potential to substitute mineral fertilizers [10].

In this context, biochar is presented in many research publications as an additive for composting with several advantages in terms of both the performance of the composting process and the quality of the compost [11]. Specifically, one of the most frequently reported phenomena is the reduction in emissions when composting a wide range of organic waste in the presence of biochar [12]. This material is produced by pyrolyzing lignocellulosic waste, typically forestry biomass; therefore, it represents a sustainable and circular approach with applications in several fields beyond waste management [13]. However, the limitations of the reported studies often prevent a correct interpretation of the effects of biochar and its underlying mechanisms. Some important drawbacks have been identified addressing basic issues, such as the absence of proper controls, incomplete biochar characterization, and incorrect gaseous emission determination, a technique which requires a substantial degree of intricacy to ensure satisfactory performance [14,15]. The lack of large-scale experiments is a matter of concern. Composting is a very complex process and the effect of biochar can only be understood in its totality when all factors are considered. A multitude of factors must be taken into consideration, including but not limited to the decrease in compaction and the increase in temperature [16]. Many of these factors are not observable when working at smaller scales.

Therefore, the objective of this critical review is to compile recent results on the use of biochar in organic waste composting. The primary focus is the reduction of emissions of gases such as ammonia, methane, nitrous oxide and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), as well as odors (as determined by olfactometry). The results presented in the literature will be analyzed in terms of their robustness and scientific applicability. Currently, it is essential to establish whether the existing results on this topic are sufficiently consistent to enable a rigorous environmental and economic assessment.

2. What Is Biochar (Beyond the General Concept)?

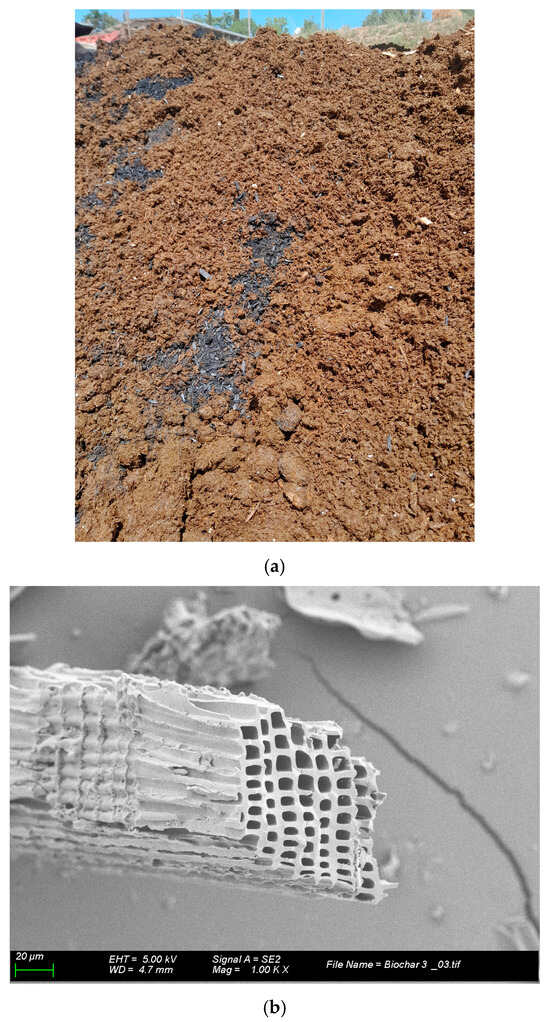

According to the UK Biochar Research Centre, “Biochar is a form of charcoal created by heating organic material, known as biomass, in an environment without oxygen at temperatures of 400 °C or higher. This process, called pyrolysis, produces energy-rich gases and liquids as well as a solid product—biochar” [17]. Although similar definitions of biochar can be found in scientific articles and provided by institutions, it is in fact a wide range of materials with different properties and, consequently, different behavior in its applications. This is due to two main reasons: the feedstock used in the pyrolysis process and the specific conditions of this process, with temperature being the main factor [18,19]. Figure 1 presents the visual appearance and microscopic SEM (scanning electron microscope) images of biochar obtained from the pyrolysis of wood waste.

Figure 1.

Macroscopic (a) and microscopic (b) SEM (scanning electron microscope) images from woody biochar (Figure 1a is of biochar in a manure composting pile).

Despite this being outside the scope of this paper, the following brief summary outlines solids coming from equivalent processes with similar properties and by-products of pyrolysis. This should provide some clarity over the terminology used in scientific publications.

2.1. Pyrolysis By-Products and Other Materials of Thermal Treatments

According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), biochar is the union of the prefix ‘bio-’, which refers to a biomass-based material, and the suffix ‘-char’, which refers to the carbonization process of the biomass [20]. When this broad definition is followed, the term “biochar” can bring confusion with other related terms commonly used in the literature. Despite the similarities in production or properties, the following terms should not be confused with biochar.

Hydrochar: it is produced by the low-temperature, pressurized thermal conversion of biomass in a process known as hydrothermal carbonization. This involves heating the feedstock in water under subcritical conditions, resulting in a product with a higher carbon content and lower nitrogen and sulfur levels than the original feedstock [17,21]. While hydrochar has been shown to be superior to biochar in certain applications, the requirement for high-pressure conditions increases the complexity and cost of the process in economic and environmental terms [22].

Gasification char: It comes from gasification instead of pyrolysis, the objective of which is the production of syngas [23]. In this case, the residual char is considered waste rather than a product. Although it contains mainly carbon, its uses are very limited.

Bio-tar or Bio-oil: It is a liquid by-product generated during the pyrolysis of biomass. The ratio of bio-oil to biochar depends heavily on the process temperature. It is characterized by its complex composition, high viscosity, and the presence of several liquid phases (aqueous and organic) [24].

Activated carbon: Not being strictly biochar, it can be derived from any biomass or even fossil coal via further activation treatments, and it is mainly used for filtering or sorption applications [25].

Apart from these biochar-like materials, which are obtained from a unique process, it is important to highlight that some recent studies have focused on the use of combined products. These are typically biochar and hydrochar [26], but can also include more exotic products such as compochar. This is a combination of biochar and compost which is used to enhance microbial activity and nutrient retention in soils [27].

2.2. Feedstocks for Pyrolysis

In the scientific literature, the range of feedstocks used for pyrolysis that result in biochar practically includes all materials with a high carbon content and, preferably, a low moisture content. According to the International Biochar Initiative, biomass waste materials appropriate for biochar production include crop residues, yard waste, food waste, forestry waste, animal manure and, to a lesser extent, wastewater sludge [28]. Agricultural residues are probably the main raw material for pyrolysis because they are inexpensive, relatively toxin-free, and have a high carbon content [29]. In this case, the availability of biomass is another important factor. In fact, economic issues imply that biomass resources must be available in the area of biochar production.

In any case, research has clearly demonstrated that the feedstock plays a dominant role in the properties of the biochar obtained [30,31]. Among these properties, the specific surface area is the most important factor in processes because of the strong interactions among the phases involved in composting (gas, liquid and solid) [32]. Table 1 presents recent examples of feedstocks used in pyrolysis and the temperature reached. The pyrolysis temperature highly influences the main characteristics of the resulting biochar, which determine its subsequent applications. This table is only a summary, as a complete picture showing the relationship between feedstock, pyrolysis and biochar would be unwieldy and instantly out of date. It is also important to note the general trend of incorporating new materials into the pyrolysis process with the aim of integrating this technology into waste-based biorefineries, which typically have biological processes such as wastewater treatment (activated sludge), anaerobic digestion or composting [4].

Table 1.

Examples of feedstocks used in pyrolysis, the production temperatures and their consequent variety in characteristics.

3. Biochar Co-Composting as a Gaseous Emissions Mitigation Strategy

3.1. Application Dosage

Table 2 shows some very recent scientific publications in which biochar made from different types of feedstock has been used to reduce gaseous emissions from composting. The main targets are ammonia and greenhouse gases. Apart from the results achieved in each experiment, which in some cases are very high (in the range of 10–60% for ammonia and even higher for methane, as presented later), the main objective of Table 2 is to show that the biochar/waste ratio is presented in different forms in the scientific literature. This makes it difficult to reproduce the published results and to draw significant conclusions. Articles that do not specify the mass fraction to which they refer are the most ominous. From Table 2, it can be seen that the misleading use of the biochar/waste ratio in total wet matter is widespread. As the moisture content of both biochar and organic waste materials changes for multiple reasons, this ratio is neither informative nor reproducible and should be avoided in future studies.

Table 2.

Examples of ratios of biochar used for composting organic waste with the aim of reducing gas emissions. Note the variety of units used.

In this sense, a consensus should be reached on the units in which biochar dosage is reported, in order to facilitate comparison between studies [48]. Additionally, as a carbon-sequestering agent, biochar can play a key role in reducing the carbon footprint of the waste management sector [49]. Therefore, any sustainability assessment will have an important source of error if the biochar/waste ratio is not consistently known. The same will be true of any economic analysis that considers biochar as composting and compost additive.

Hence, for the sake of reproducibility, standardizing dosage units is imperative. Given that biochar is an inorganic compound, the most reasonable units are dry mass of biochar by dry mass of organic waste composted; alternatively, it could be expressed asa total dry matter percentage [32]. Indeed, the provision of organic matter (OM) from the compostable substrate would yield valuable insights. However, it is more pertinent to maintain the same parameter on both sides of the fraction, and measuring the OM of biochar is a risky endeavor. Biochar is produced at similar temperatures as the most common way of measuring OM. However, it should be noted that the production process is performed in anoxic conditions. Consequently, the attempt to measure OM would result in the oxidation of the material. All OM was transformed into an inorganic solid during the pyrolysis process.

Another issue arising from Table 2 is the wide range of biochar/organic waste ratios used, regardless of the units employed to express this ratio. This is another drawback for the commercial application of biochar in composting, since this ratio is critical for any sustainability assessment. The disparity in biochar ratios is mainly due to the lack of knowledge regarding the mechanism by which biochar reduces emissions in composting, as discussed in Section 4.

3.2. Ammonia

Ammonia is the main gas emitted during the composting process, and its emissions are highly dependent on the composition and temperature of the composting mass [50,51]. Accordingly, any study investigating the impact of additives such as biochar on ammonia emissions during composting must consider the scale of the process. As there is a clear lack of large-scale composting trials in the scientific literature, any results obtained at a laboratory scale must be analyzed carefully and critically. This issue sometimes makes published scientific articles very difficult to interpret, especially if the biochar/organic waste ratio is not clearly expressed. Table 3 presents some examples of the wide disparity in ammonia reduction during the composting process at different scales and ratios.

Table 3.

Examples of the decrease in ammonia emissions observed in some composting experiments using biochar as an additive.

Table 3 only presents a few examples and no systematic review containing more compiled data on this topic has been found in the recent literature, hence leading to the following conclusion: when studying the effect of biochar on composting ammonia emissions, the biochar ratio (expressed in a reproducible way) and experiment scale are factors intimately related to these emissions. Therefore, results should not be presented without this information, as it can lead to confusion and make comparisons difficult. This point is particularly important when emissions are presented as emission factors throughout an entire composting experiment (in terms of the mass of ammonia emitted per mass unit of organic waste), as these emission factors are often used for advanced calculations relating to environmental impact, such as Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) [57].

3.3. Greenhouse Gases: Methane and Nitrous Oxide

Following the issue of performing reliable LCAs, the potential of biochar to mitigate greenhouse gases during composting has been the subject of recent literature. Methane is the main greenhouse gas studied, although some scientific publications have also presented results on nitrous oxide due to its powerful global warming potential, which is around 278 times that of carbon dioxide over a 100-year time scale. According to the IPCC, this number is around 27 for methane [58]. A comprehensive review of this topic has recently been published [12]. This latter paper considers some critical aspects related to biochar, such as its characteristics, ratio and chemical composition, as well as its porosity, in an attempt to determine the mechanism by which biochar can significantly reduce methane and nitrous oxide emissions. However, from a composting perspective, other crucial phenomena define the amount of these emissions, and these differ for each compound, as explained below.

As composting is a fully aerobic process, methane in composting emissions can only originate from anaerobic zones in the composting matrix [9]. This is a direct consequence of a lack of porosity in the mixture, which also causes unpleasant odors [8]. Therefore, the effect of biochar on methane emissions is inextricably linked to a rigorous adjustment of the initial mixture’s porosity. Unfortunately, porosity is rarely measured precisely in composting using advanced methods, beyond some rules of thumb or using the assumption that bulking agent is accurately correlated to porosity [59]. This results in a wide range of values when consulting methane reduction in composting emissions, from no reduction to unreliable values close to total reduction. Further research is clearly necessary to study methane emissions from composting in relation to porosity and its key role in maintaining aerobic conditions in any composting process. Furthermore, this is even more pertinent given that it is well known that biochar increases the porosity of organic matrices [60], causing confusion when interpreting the effects of biochar on methane emissions.

The case of nitrous oxide is even more complex. This compound is formed through the partial denitrification of nitrates, and in a composting environment, its formation is closely related to the equilibrium and transformation of different nitrogen forms [61]. In composting, the formation of nitrous oxide means that two things must happen: firstly, nitrification is compulsory, as the nitrogen in organic waste is mainly in reduced forms, and secondly, although only partially, denitrification must also occur. These two situations can only be found simultaneously in the final stage of composting, when the temperature decreases to a level that allows nitrification to occur [62]. This should be coupled with the presence of zones with limited oxygen, as denitrification is an anoxic process and the presence of nitrifying and denitrifying microorganisms is necessary [63]. In addition to this evident biological complexity, nitrous oxide is often detected at concentrations close to the detection limit, which makes interpreting experimental data very difficult, especially on a large scale, where the aforementioned effects of biochar, such as temperature retention and increased porosity or heterogeneity of the composting mass, must be considered [32].

3.4. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC)

Volatile Organic Compounds include an immense variety of molecules exhibiting diverse characteristics, including terpenes, aromatic compounds and sulfur-containing compounds. Furthermore, the measurement of total VOC is performed with different standards, such as iso-butylene. In addition to this, the measurement of specific VOC has been undertaken. A still-limited body of research demonstrates biochar efficacy in mitigating a variety of VOC emissions during the composting process, mainly during the thermophilic phase [32,64,65]. However, not all VOC showed the same behavior in previous works, as is the case with unpleasant odor compounds such as methyl mercaptan and carbon disulfide. Moreover, given the disparity in the VOC measured, further consensus is necessary regarding the most pertinent VOC to report. This thorough selection is particularly important given the high cost of VOC analysis.

The study of VOC is typically conducted in conjunction with ammonia emissions, given their odor-causing effect. However, the presence of odorous emissions does not directly correspond with the concentration of individual gases. Consequently, dynamic olfactometric analysis is imperative to comprehensively assess the potential impact on the population. Despite the prevalence of literature employing the concept of odors or analogous terms in describing their research, a significant proportion of these studies methodically quantify gas emissions in isolation. This methodological approach fails to consider the impact of combined emissions on the human nose, thereby compromising a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter. Very few dynamic olfactometry analyses have been published in the literature regarding large-scale composting. This scarcity is even more pronounced when biochar has been applied [32]. Quantifying the odorous impact is highly relevant for full-scale applications, since it will determine the post-treatment requirements of the composting plant (i.e., the measures necessary to mitigate the societal impact of the plant) and its implications for design and operational costs.

4. Potential Mechanisms for Emissions Mitigation

According to previous results, it is evident that biochar can be an effective additive for reducing the inherent gaseous emissions from organic waste composting. Understanding the mechanisms behind this reduction is essential for the commercial implementation of using biochar in composting, which is known to have other significant benefits, such as improving the quality of compost [11]. Although important efforts are being made to understand these mechanisms, there is still a clear lack of knowledge about them, particularly given that some of the phenomena described in this text exhibit obvious interactions that are not usually considered. Table 4 illustrates a synopsis of the predominant mechanisms most supported by the extant literature. These mechanisms are subsequently examined in greater detail in the following subsections.

Table 4.

Mechanisms for main gaseous emission reduction during biochar co-composting.

4.1. Physicochemical Mechanisms

Despite the inherent variabilities of composting substrate and biochar characteristics, most biochar types have shown a conjunction of physicochemical characteristics (high porosity, large surface area, and high ion exchange capacity) that make them excellent adsorbent materials for NH3 and VOC, although adsorption is not the only mechanism for the reduction of these compounds, as discussed in the following section. When large-scale experiments have been performed, biochar has widely been reported to increase the temperature of the composting process given its thermal properties [70]. However, many bench-scale experiments reporting gaseous emissions have been performed at controlled temperatures. This is particularly misguiding for NH3 emissions, which are exponentially dependent on the temperature of the process, as previously mentioned. Moreover, lower pH values have been shown to increase ammonium (NH4+) concentration, thus preventing ammonia emissions, thus affecting the chemical equilibrium of NH3/NH4+ [71].

In the case of CH4, its emissions are reduced by the increased porosity which improves oxygen transport, thus limiting the activity of methanogenic bacteria [73]. Therefore, biochar’s physicochemical characteristics have been shown to influence the consortium of microorganisms present in the composting matrix. New metadata studies indicate that there are boundaries under or over which a decrease in emissions is negligible for the different parameters. For example, GHG emissions can be reduced by half under most conditions but are limited by acidic environments [74]. These results bring us closer to defining the correlations between physicochemical parameters and gaseous emissions, but equivalent research is needed to better understand the effect on microbial interactions. Regarding gaseous interactions, CH4 and CO2 sorption in biochar have been studied in other research fields, showing a preferential selectivity of CO2 over CH4 [75]. Despite the numerous studies where these two gases have been measured during composting, the effect of this potential selectivity has not been discussed.

The challenge of defining VOC mitigation mechanisms stems from the extensive number of compounds classified within this group. The utilization of biochar has been demonstrated to be an effective measure in mitigating VOC emissions during the storage of kitchen waste prior to its composting. This approach has shown a substantial reduction in emissions, with a documented 70% decrease in VOC emissions observed [72]. However, further research is required to understand which physicochemical parameters exert an influence on VOC emissions. Moreover, a microbiological analysis in addition to a comprehensive quantification of VOC is necessary to discern the potential mitigation mechanisms caused by alterations in the microbial community.

Ion exchange capacity in composting has been reported to increase with biochar presence [76]. Similarly, biochar’s large surface area has been correlated with an emission decrease [77]. All of the above have an impact on Direct Interspecies Electron Transfer (DIET). However, to the authors’ knowledge, DIET has only been reported once in reference to biochar co-composting [78]. This is particularly surprising given the relevance the DIET phenomenon has gained in explaining the impact of biochar during the analogous process of anaerobic digestion [79,80].

4.2. Microbiology

As described, it is challenging to discern the mechanisms of biochar’s effect, not only because of the lack of large-scale data or variations within biochar characteristics but also because the mechanistic pathways are interrelated. The clearest example is found with CH4. Biochar increases the porosity, thus improving the oxygen availability within the composting pile. These conditions make it unfavorable for methanogenic bacteria, thus preventing CH4 emissions are [66]. However, further research has shown that, consequently, there is also a change in the methane oxidation genes and a reduction in methanogenic bacteria [67].

NH3 and N2O emissions are linked by the nitrogen cycle of nitrification/denitrification. Biochar presence enhances full denitrification to N2, therefore avoiding N2O emissions. The ionic concentration in solid samples of NH4+, nitrate (NO3−) and nitrite (NO2−) is measured to understand which steps of the nitrogen cycle are affected by biochar’s presence, and the subsequent effect on the microbial community. The correlations found to date are not conclusive, and further research is still needed to fully understand biochar’s effect [68,69]. Ammonia becomes an undesired gas to emit not only due to its odorous impact but also due to its role as an indirect greenhouse gas, leading to N2O generation [81] and the reduction of nutrients in the final compost [10]. However, results seem to indicate that its emissions are controlled by physicochemical parameters such as temperature and pH [71,82].

Some research explores the possibility of pre-treating biochar to improve the mitigation of gaseous emissions. These alternatives range from oxidation to iron loading [83,84]. Composting has maintained its important role in the waste treatment industry thanks to its straight-forward management and low economic costs. This is a characteristic these novel treatments do not safeguard. Hence, a full cycle analysis will need to be conducted to account for the economic and environmental aspects. This will clarify the economic-technical feasibility of such sophisticated modifications. For this, the post-treatment of gaseous emissions should be considered. The decrease in demand for reagents for chemical neutralization or the extended duration of a biofilter’s lifetime are indeed positive aspects to account for.

5. Limitations, Challenges and Future Work

Biochar is an emerging material with great potential for capturing and storing carbon. In this sense, all its applications will have a positive effect on reducing the overall carbon footprint, particularly in areas such as waste management.

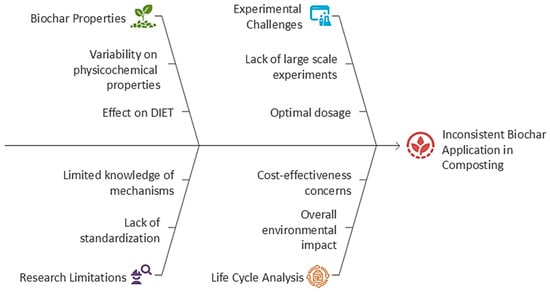

However, there are several unknowns regarding the application of biochar in different processes, including the biological treatment of organic waste and its consequent emissions. The first area of disagreement concerns the optimal dosage or application rate of a material that is often not well characterized. It is important to regulate the dosage as well as the physicochemical properties of the biochar and the operational conditions of the process, to avoid undesirable effects. Typically, biochar is added at the start of the process and mixed simultaneously with the bulking agent. Limited research has been conducted on the benefits, challenges and realistic possibilities of integrating the biochar gradually or at different moments of the process [85]. Another important issue is the absence of works conducted at full- and large-scale, which is a critical aspect of composting, as scaling up changes the temperature profiles in the composting mass [32,51] and, consequently, the emission patterns of almost all gases emitted during composting [8,9]. The mitigation of gaseous emissions brings a sustainability benefit; however, it might not compensate if an extensive pretreatment of biochar is needed. Figure 2 summarizes these knowledge limitations and their consequences for the full development of biochar as a composting additive, as is the case with its use in anaerobic digestion [86].

Figure 2.

Challenges in biochar use for composting regarding gaseous emissions.

Accordingly, future work on using biochar to reduce undesirable composting emissions should focus on these two requirements: i. using consistent and reproducible biochar dosages, which must be thoroughly characterized, and ii. performing composting experiments at representative scales. This information should form the basis for proposing reliable mechanisms to understand the effects of biochar on the composting mass. This would result in a proper design of abatement units for gas emissions and providing a database for reliable LCA and economic studies to facilitate the implementation of this strategy in full-scale composting. The results of this analysis will be considerably influenced by several factors, including, but not limited to, the types of waste used, the composting plant configuration (aeration regime or type of bulking agent), the presence (or absence) of gas emissions abatement units, regional gas emission legislation and certification options for carbon capture. A comprehensive evaluation of biochar co-compost should encompass not only its performance in the process, but also its production impact, as well as consideration regarding transport, storage and post-application. Particularly given the extensive research that has been performed on biochar co-compost to improve soil quality [11,87].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.O.-B., D.G. and A.S.; formal analysis, A.S.; investigation, E.O.-B., D.G. and A.S.; resources, E.O.-B. and D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.O.-B. and D.G.; writing—review and editing, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Frigerio, J.; Bertacchi, S.; Mecca, S.; Digiovanni, S.; Molteni, T.; Mapelli, V.; Beverina, L.; Lotti, M.; Croci, E.; Branduardi, P.; et al. From urban trash to city cash: Technologies for sustainable development of cities through the valorisation of urban organic waste in Europe. Waste Manag. Bull. 2025, 3, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukare, A.; Yadav, R.; Kautkar, S.; Kuppusamy, P.; Sharma, K.; Shaikh, A.; Pawar, A.; Gadade, A.; Vigneshwaran, N.; Saxena, S.; et al. Waste to wealth: Microbial-based sustainable valorization of cotton biomass, processing waste and by-products for bioenergy and other value-added products to promote circular economy. Waste Manag. Bull. 2024, 2, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Molina-Peñate, E.; Sánchez, A. An Overview of the Technological Evolution of Organic Waste Management over the Last Decade. Processes 2025, 13, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucina, M. Integrating anaerobic digestion and composting to boost energy and material recovery from organic wastes in the Circular Economy framework in Europe: A review. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023, 24, 101642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, Đ.; Lončarić, Z.; Jović, J.; Samac, D.; Popović, B.; Tišma, M. Digestate Management and Processing Practices: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artola, A.; Font, X.; Moral-Vico, J.; Sánchez, A. The role of solid-state fermentation to transform existing waste treatment plants based on composting and anaerobic digestion into modern organic waste-based biorefineries, in the framework of circular bioeconomy. Front. Chem. Eng. 2024, 6, 1463785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.; Artola, A.; Font, X.; Gea, T.; Barrena, R.; Gabriel, D.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Roig, A.; Cayuela, M.L.; Mondini, C. Greenhouse gas emissions from organic waste composting. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2015, 13, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, D.; Gabriel, D.; Sánchez, A. Odors Emitted from Biological Waste and Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Mini-Review. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jin, C.; Sun, S.; Yang, D.; He, Y.; Gan, P.; Nalume, W.G.; Ma, Y.; He, W.; Li, G. Recognizing the challenges of composting: Critical strategies for control, recycling, and valorization of nitrogen loss. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 198, 107172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Cayuela, M.L.; Sánchez-García, M.; Vandecasteele, B.; D’Hose, T.; López, G.; Martínez-Gaitán, C.; Kuikman, P.J.; Sinicco, T.; Mondini, C. Agronomic Evaluation of Biochar, Compost and Biochar-Blended Compost across Different Cropping Systems: Perspective from the European Project FERTIPLUS. Agronomy 2019, 9, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Yang, C.; Li, M.; Zheng, Y.; Ge, C.; Gu, J.; Li, H.; Duan, M.; Wang, X.; Chen, R. Research progress and prospects for using biochar to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions during composting: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 149294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkolu, M.; Gundekari, S.; Omvesh; Palla, V.C.S.; Kumar, P.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Vinodkumar, T. Recent Advances in Biochar Production, Characterization, and Environmental Applications. Catalysts 2025, 15, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, S.G.; McGinn, S.M.; Hao, X.; Larney, F.J. Techniques for measuring gas emissions from a composting stockpile of cattle manure. Atmos. Environ. 2004, 38, 4643–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, D.; Barrena, R.; Moral-Vico, J.; Irigoyen, I.; Sánchez, A. Addressing the gaseous and odour emissions gap in decentralised biowaste community composting. Waste Manag. 2024, 178, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Akdeniz, N. Mathematical modeling of biochar’s role in elevating co-composted poultry carcass temperatures. Waste Manag. 2024, 173, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is Biochar? UK Biochar Research Centre. Available online: https://www.biochar.ac.uk/what_is_biochar.php (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Li, S.; Harris, S.; Anandhi, A.; Chen, G. Predicting biochar properties and functions based on feedstock and pyrolysis temperature: A review and data syntheses. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Amirahmadi, E.; Neugschwandtner, R.W.; Konvalina, P.; Kopecký, M.; Moudrý, J.; Perná, K.; Murindangabo, Y.T. The Impact of Pyrolysis Temperature on Biochar Properties and Its Effects on Soil Hydrological Properties. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glossary of Terms Used in Biochar Research (IUPAC Technical Report). IUPAC (The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry). Available online: https://iupac.org/project/2015-056-3-600 (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Davies, G.; El Sheikh, A.; Collett, C.; Yakub, I.; McGregor, J. Catalytic carbon materials from biomass. In Emerging Carbon Materials for Catalysis, 1st ed.; Sadjadi, S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Chapter 5; pp. 161–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambo, H.S.; Dutta, A. A comparative review of biochar and hydrochar in terms of production, physico-chemical properties and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 45, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, A.; Benedetti, V.; Villot, A.; Patuzzi, F.; Gerente, C.; Baratieri, M. Innovative Pathways for the Valorization of Biomass Gasification Char: A Systematic Review. Energies 2023, 16, 4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jia, J.; Huo, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, Z. Preparation of bio-carbon by polymerization of bio-tar: A critical review on mechanisms, processes, and applications. Biochar 2025, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, M. How Activated Carbon Can Help You—Processes, Properties and Technological Applications. Technologies 2023, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufian, J.; Babaakbari, M.; Avanes, A.; Moradi, S. Investigating the Effect of Activated Chlorella vulgaris Algae Biochar and Hydrochar on the Distribution and Bioavailability of Cadmium in Soil. Iran J. Soil Water Res. 2025, 55, 2191–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudek, P.; Langhansová, L.; Dvořáková, M.; Revutska, A.; Petrová, Š.; Hirnerová, A.; Bouček, J.; Trakal, L.; Hošek, P.; Soukupová, M. The impact of the application of compochar on soil moisture, stress, yield and nutritional properties of legumes under drought stress. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biochar Feedstocks. International Biochar Initiative. Available online: https://biochar-international.org/about-biochar/how-to-make-biochar/biochar-feedstocks/ (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Jindo, K.; Mizumoto, H.; Sawada, Y.; Sanchez-Monedero, M.A.; Sonoki, T. Physical and chemical characterization of biochars derived from different agricultural residues. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 6613–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Camps-Arbestain, M.; Lehmann, J. Biochar: A Guide to Analytical Methods, 1st ed.; CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Mehejabin, F.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Almomani, F.; Khan, N.A.; Badruddin, I.A.; Kamangar, S. Biochar produced from waste-based feedstocks: Mechanisms, affecting factors, economy, utilization, challenges, and prospects. GCB Bioenergy 2024, 16, e13175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera-Begué, E.; González, D.; Kaal, J.; Camps-Arbestain, M.; Sánchez, A. Commercial-scale co-composting of wood-derived biochar with source-selected organic fraction of municipal solid waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 431, 132595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Reddy, N.G.; Huang, X.; Chen, P.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lin, P.; Garg, A. Effects of pyrolysis temperature, feedstock type and compaction on water retention of biochar amended soil. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiaorong, L.; Yan, Y.; Shaopeng, L.; Hongliang, M.; Ren, G.; Yunfeng, Y. Effects of Biochar Feedstock and Pyrolysis Temperature on Soil Organic Matter Mineralization and Microbial Community Structures of Forest Soils. Front. Env. Sci. 2021, 9, 717041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Aguiar, E.; Méndez, A.; Gascó, G.; Lado, M.; Paz-González, A. The Effects of Feedstock, Pyrolysis Temperature, and Residence Time on the Properties and Uses of Biochar from Broom and Gorse Wastes. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akca, M.O.; Bozkurt, P.A.; Gokmen, F.; Akca, H.; Yağcıoğlu, K.D.; Uygur, V. Engineering the biochar surfaces through feedstock variations and pyrolysis temperatures. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 218, 118819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wystalska, K.; Grosser, A. Sewage Sludge-Derived Biochar and Its Potential for Removal of Ammonium Nitrogen and Phosphorus from Filtrate Generated during Dewatering of Digested Sludge. Energies 2024, 17, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourgkogiannis, N.; Nikolopoulos, I.; Kordouli, E.; Lycourghiotis, A.; Kordulis, C.; Karapanagioti, H.K. The Influence of Biowaste Type on the Physicochemical and Sorptive Characteristics of Corresponding Biochar Used as Sustainable Sorbent. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, V.; Ashiq, A.; Ramanayaka, S.; Wijekoon, P.; Vithanage, M. Biochar from municipal solid waste for resource recovery and pollution remediation. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.G.; Iwuozor, K.O.; Emenike, F.C.; Ajala, O.J.; Ogunniyi, S.; Muritala, K.B. Thermochemical co-conversion of biomass-plastic waste to biochar: A review. Green Chem. Eng. 2024, 5, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Han, D.; Chen, H. Pyrolysis of Waste Tires: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Herrera, D.; Prost, K.; Kim, D.-G.; Yimer, F.; Tadesse, M.; Gebrehiwot, M.; Brüggemann, N. Biochar addition reduces non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions during composting of human excreta and cattle manure. J. Environ. Qual. 2023, 52, 814–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, B.P.; Moo, Z.; Perez-Agredano, E.; Gao, S.; Zhang, X.; Ryals, R. Biochar-composting substantially reduces methane and air pollutant emissions from dairy manure. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 014081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, B.P.; Gao, S.; Thao, T.; Gonzales, M.L.; Williams, K.L.; Scott, N.; Hale, L.; Ghezzehei, T.; Diaz, G.; Ryals, R.A. Methane and nitrous oxide emissions during biochar-composting are driven by biochar application rate and aggregate formation. GCB Bioenergy 2023, 16, e13121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, S.; Rivier, P.A.; Joner, E.J.; Coutris, C.; Budai, A. Co-composting of digestate and garden waste with biochar: Effect on greenhouse gas production and fertilizer value of the matured compost. Environ. Technol. 2022, 44, 4261–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Song, L.; Jin, Y.; Liu, S.; Shen, Q.; Zou, J. Linking N2O emission from biochar-amended composting process to the abundance of denitrify (nirK and nosZ) bacteria community. AMB Express 2016, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-García, M.; Alburquerque, J.A.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Roig, A.; Cayuela, M.L. Biochar accelerates organic matter degradation and enhances N mineralisation during composting of poultry manure without a relevant impact on gas emissions. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 192, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Prats, M.; Olivera-Begué, E.; González, D.; Sánchez, A. Biochar: An emerging material for the improvement of biological treatment of organic waste. Waste Manag. Bull. 2024, 2, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Teng, F.; Chen, M.; Du, Z.; Wang, B.; Li, R.; Wang, P. Exploring negative emission potential of biochar to achieve carbon neutrality goal in China. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagans, E.; Barrena, R.; Font, X.; Sánchez, A. Ammonia emissions from the composting of different organic wastes. Dependency on process temperature. Chemosphere 2006, 62, 1534–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena, R.; Canovas, C.; Sánchez, A. Prediction of temperature and thermal inertia effect in the maturation stage and stockpiling of a large composting mass. Waste Manag. 2006, 26, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ming, R.; Liu, D.; Qiao, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Ren, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. Biochar Effectively Reduced N2O Emissions During Heap Composting and NH3 Emissions During Aerobic Composting. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczak, D.; Malińska, K.; Czekała, W.; Cáceres, R.; Lewicki, A.; Dach, J. Biochar to reduce ammonia emissions in gaseous and liquid phase during composting of poultry manure with wheat straw. Waste Manag. 2017, 66, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, R.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yang, L.; Li, Z. The Effects of Different Types of Biochar on Ammonia Emissions during Co-composting Poultry Manure with a Corn Leaf. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2019, 28, 3837–3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.L.; Yang, J.N.; Qin, S.W.; Jiang, W.; Yang, S.J. Influencing mechanisms of different additives on ammonia–nitrogen emission during aerobic composting. J. Mater Cycles Waste Manag. 2025, 27, 4252–4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Akdeniz, N.; Yi, S. Biochar-amended poultry mortality composting to increase compost temperatures, reduce ammonia emissions, and decrease leachate’s chemical oxygen demand. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 315, 107451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colón, J.; Cadena, E.; Pognani, M.; Barrena, R.; Sánchez, A.; Font, X.; Artola, A. Determination of the energy and environmental burdens associated with the biological treatment of source-separated Municipal Solid Wastes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 5731–5741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Direct Global Warming Potentials. Available online: https://archive.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/ch2s2-10-2.html (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Ruggieri, L.; Gea, T.; Artola, A.; Sánchez, A. Air filled porosity measurements by air pycnometry in the composting process: A review and a correlation analysis. Bioresour. Technol 2009, 100, 2655–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebahire, F.; Faridullah, F.; Irshad, M.; Bacha, A.U.R.; Hafeez, F.; Nduwamungu, J. Effect of Biochar on Composting of Cow Manure and Kitchen Waste. Land 2024, 13, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Inamori, Y.; Mizuochi, M.; Kong, H.; Iwami, N.; Sun, T. Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Aerated Composting of Organic Waste. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 2347–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáceres, R.; Malińska, K.; Marfà, O. Nitrification within composting: A review. Waste Manag. 2018, 72, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, L.; Song, X.; Tang, Y.; Qi, H.; Cao, H.; Wei, Z. Denitrification during composting: Biochemistry, implication and perspective. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2020, 153, 105043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Sánchez-García, M.; Alburquerque, J.A.; Cayuela, M.L. Biochar reduces volatile organic compounds generated during chicken manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 288, 121584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosik, J.; Kosiorowska, K.E.; Tomczyk, K.; Domińska, M.; Hamal, K.; Stegenta-Dąbrowska, S. Compost’s biochar as a practical odor mitigation strategy for the composting industry. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 32, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Monedero, M.A.; Cayuela, M.L.; Roig, A.; Jindo, K.; Mondini, C.; Bolan, N. Role of biochar as an additive in organic waste composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 247, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, R.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Kong, Y.; Jiang, T.; Chang, J.; Yao, S.; Yuan, J.; Li, G.; Wang, G. Biochar reduces gaseous emissions during poultry manure composting: Evidence from the evolution of associated functional genes. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmino, M.V.; Trémier, A. Nitrogen Losses Mitigation by Supplementing Composting Mixture with Biochar: Research of the Ruling Parameters. Waste Biomass Valorization 2023, 15, 959–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Ji, Z.; Qin, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Huang, H. Different types of biochar reduce N2O emissions by mediating the interplay of multiple factors during composting. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 119381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottani, F.; Parenti, M.; Pedrazzi, S.; Moscatelli, G.; Allesina, G. Impacts of gasification biochar and its particle size on the thermal behavior of organic waste co-composting process. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 153022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmino, M.V.; Trémier, A.; Couvert, A.; Szymczyk, A. New insights into biochar ammoniacal nitrogen adsorption and its correlation to aerobic degradation ammonia emissions. Waste Manag. 2024, 178, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosik, J.; Łyczko, J.; Marzec, Ł.; Stegenta-Dąbrowska, S. Application of Composts’ Biochar as Potential Sorbent to Reduce VOCs Emission during Kitchen Waste Storage. Materials 2023, 16, 6413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.K.; Lin, C.; Hoang, H.G.; Sanderson, P.; Dang, B.T.; Bui, X.T.; Nguyen, N.S.H.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Tran, H.T. Evaluate the role of biochar during the organic waste composting process: A critical review. Chemosphere 2022, 299, 134488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xiong, Z. Biochar amendments mitigate trace gas emissions in organic waste composting: A meta-analysis. Nitrogen Cycl. 2025, 1, e005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Liu, S.; Zhang, K.; Xia, K. Competitive sorption of CH4 and CO2 on coals: Implications for carbon geo-storage. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prost, K.; Borchard, N.; Siemens, J.; Kautz, T.; Séquaris, J.-M.; Möller, A.; Amelung, W. Biochar affected by composting with farmyard manure. J. Environ. Qual. 2013, 42, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jindo, K.; Sonoki, T.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A. Stabilizing organic matter and reducing methane emissions during manure composting with biochar to strengthen the role of compost in soil health. Soil Environ. Health 2025, 3, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, J. Magnetic biochar accelerates microbial succession and enhances assimilatory nitrate reduction during pig manure composting. Environ. Int. 2024, 184, 108469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Wang, G.; Hu, C.; Zhou, S.; Clough, T.J.; Wrage-Mönnig, N.; Luo, J.; Qin, S. Electron shuttle potential of biochar promotes dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium in paddy soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 172, 108760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, M.T.; Luo, G.; Zhang, S.; Białowiec, A. Direct interspecies electron transfer mechanisms of a biochar-amended anaerobic digestion: A review. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2023, 16, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yang, T.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, T.; Zheng, C. Effects of biochar carried microbial agent on compost quality, greenhouse gas emission and bacterial community during sheep manure composting. Biochar 2023, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Xu, M.; Chen, Y.; Dong, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Zheng, G.; Liu, J. Revealing GHG-NH3 emission mechanisms: A comparison of food waste composting and biogas residue composting. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 32, 102318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, H.; Ding, J.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, S.; Feng, Q.; Xu, P. Potential of novel iron 1,3,5-benzene tricarboxylate loaded on biochar to reduce ammonia and nitrous oxide emissions and its associated biological mechanism during composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 396, 130424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Gao, P.; Lu, Y.; Cui, X.; Peng, F. Hydrogen peroxide-aged biochar mitigating greenhouse gas emissions during co-composting of swine manure with rice bran. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 374, 126255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rahim, M.G.M.A.; Dou, S.; Xin, L.; Xie, S.; Sharaf, A.; Moussa, A.A.; Eissa, M.A.; Mustafa, A.-R.A.; Ali, G.A.M.; Hamed, M.H. Effect of biochar addition method on ammonia volatilization and quality of chicken manure compost. Zemdirbyste-Agriculture 2021, 108, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manga, M.; Aragón-Briceño, C.; Boutikos, P.; Semiyaga, S.; Olabinjo, O.; Muoghalu, C.C. Biochar and Its Potential Application for the Improvement of the Anaerobic Digestion Process: A Critical Review. Energies 2023, 16, 4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Bolan, N.; Jospeh, S.; Anh, M.T.L.; Meier, S.; Kookana, R.; Borchard, N.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Jindo, K.; Solaiman, Z.M.; et al. Complementing compost with biochar for agriculture, soil remediation and climate mitigation. Adv. Agron. 2023, 179, 1–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.