Assessment of Karacadağ Basalt as a Sustainable Material for Eco-Friendly Road Infrastructure

Abstract

1. Introduction

Geological and Cultural Context of Basalt Use in Diyarbakır

2. Materials and Methods

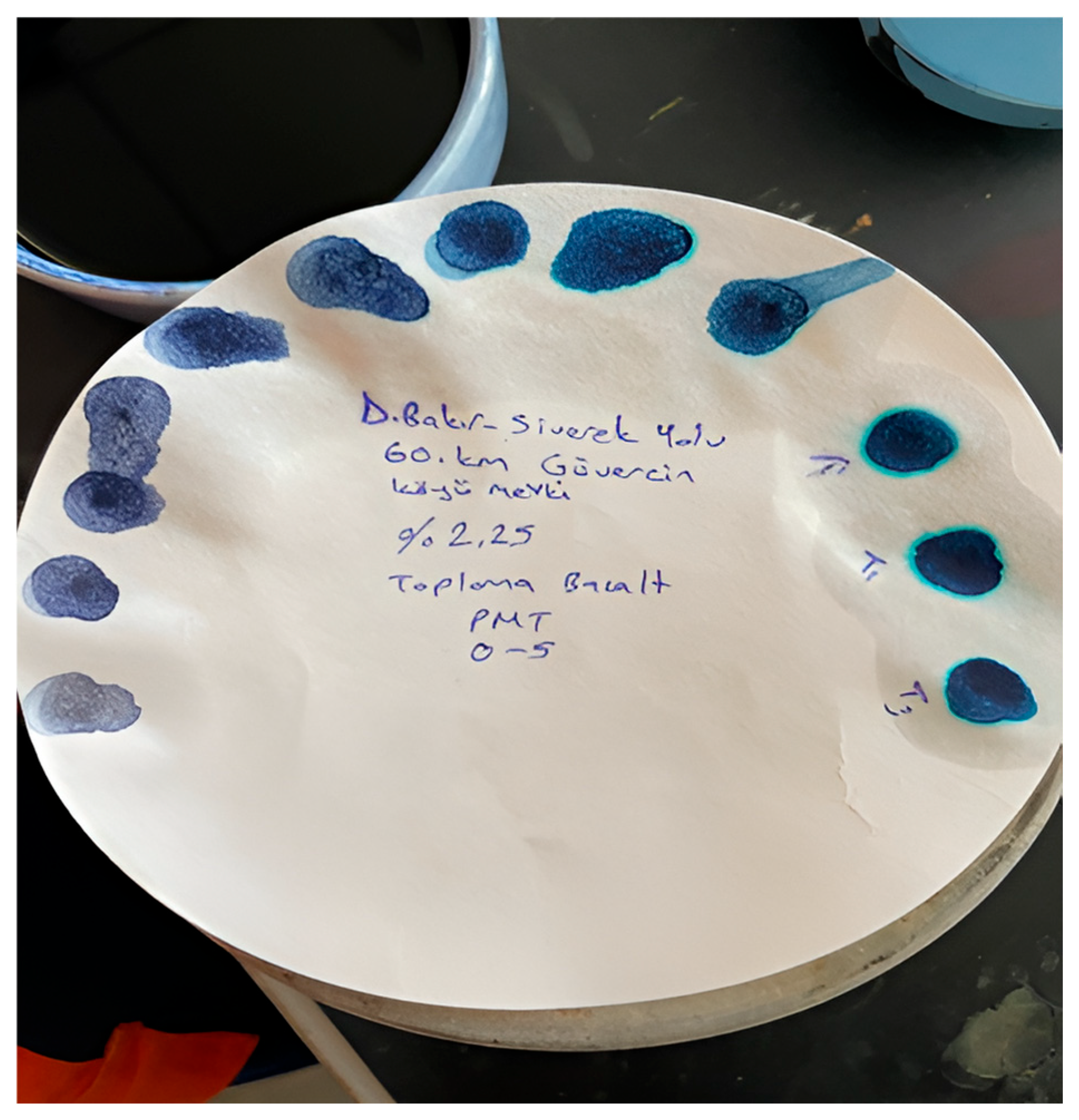

2.1. Methylene Blue Test

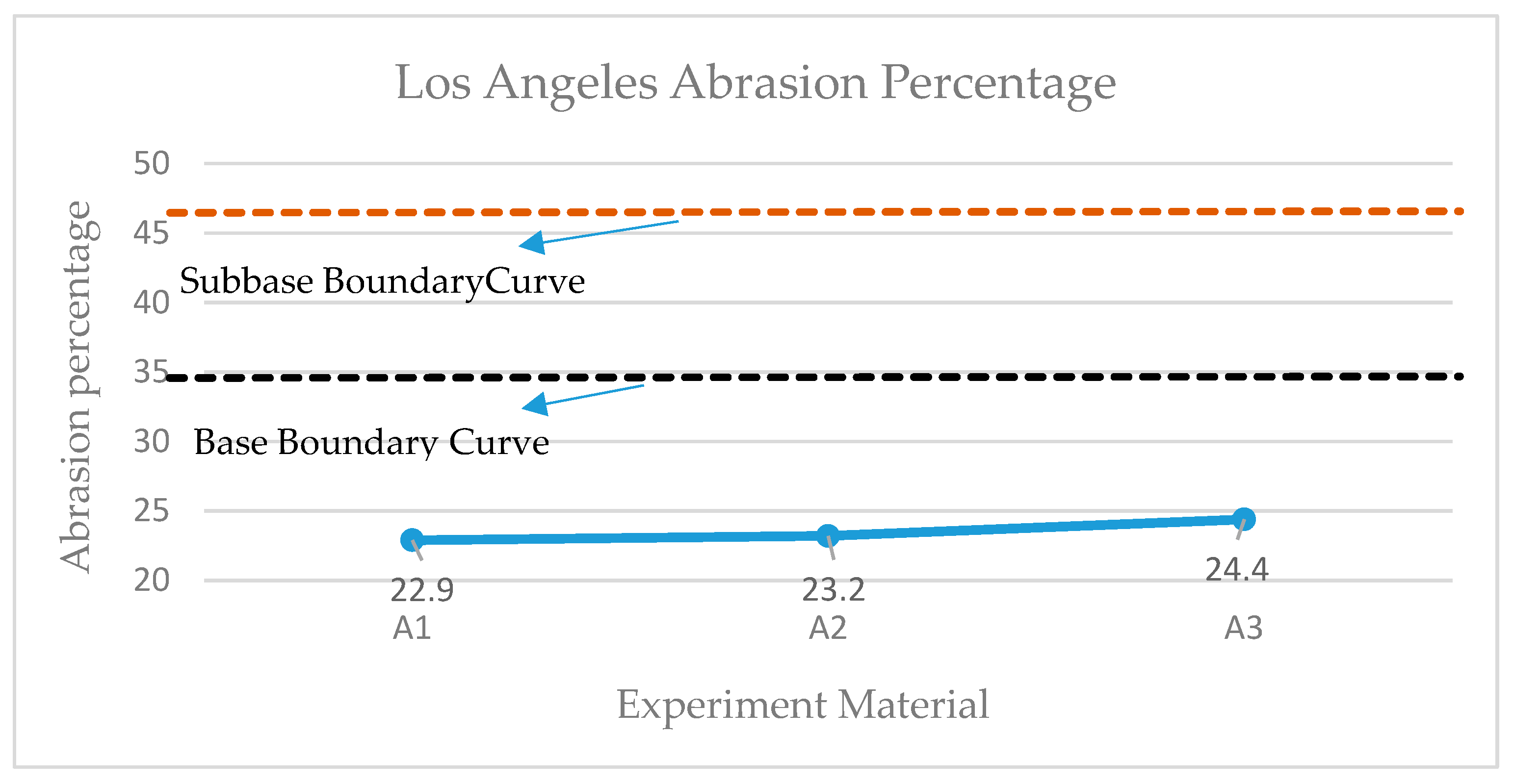

2.2. Los Angeles Abrasion Test

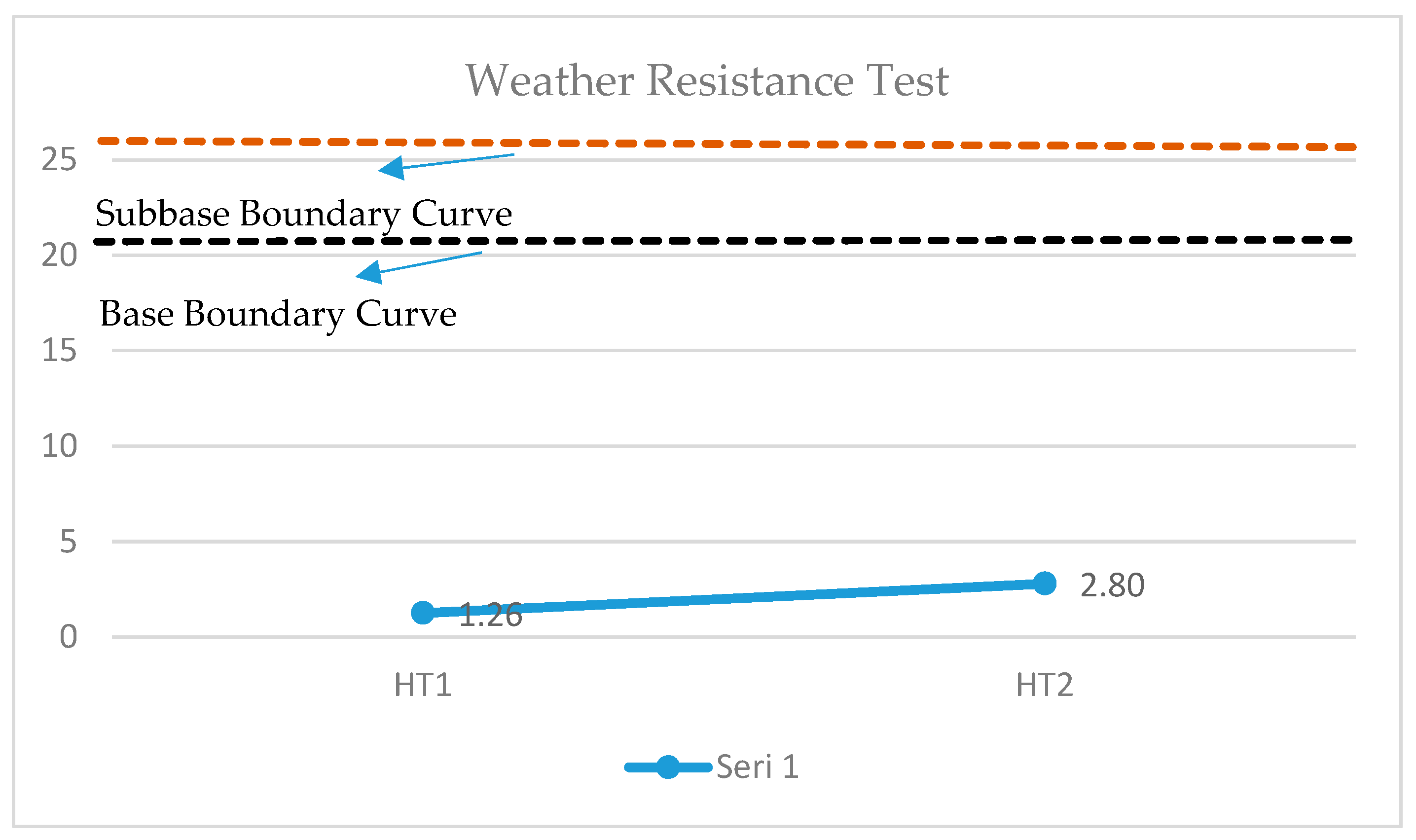

2.3. Weather Resistance Test (MgSO4)

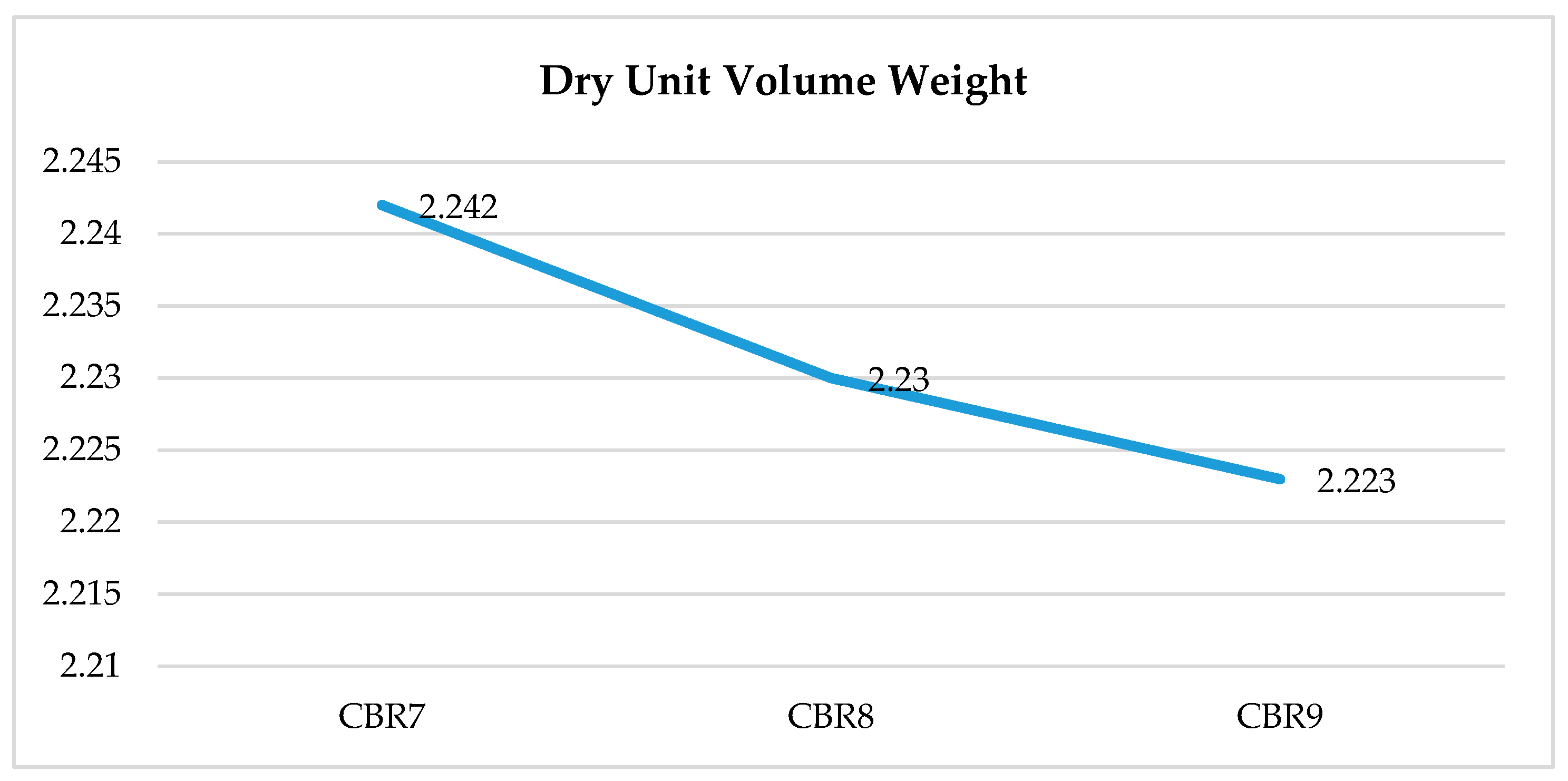

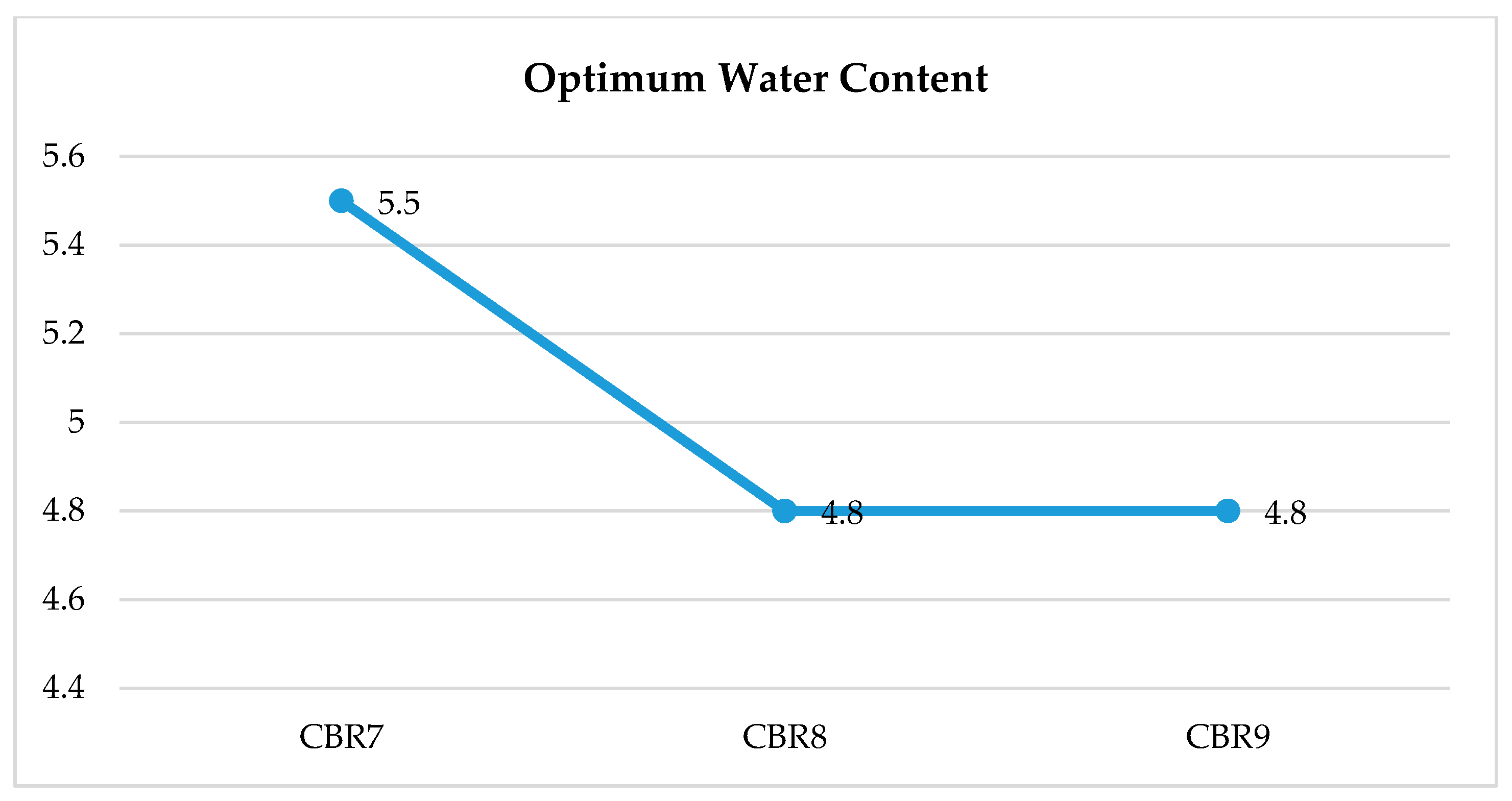

2.4. California Bearing Ratio (CBR) Test

2.5. Geological Setting and Sampling Location

3. Results

Aggregate Processing Flow of Karacadag Basalt

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanical and Durability Implications

4.2. Environmental and Energy Aspects of Basalt Processing

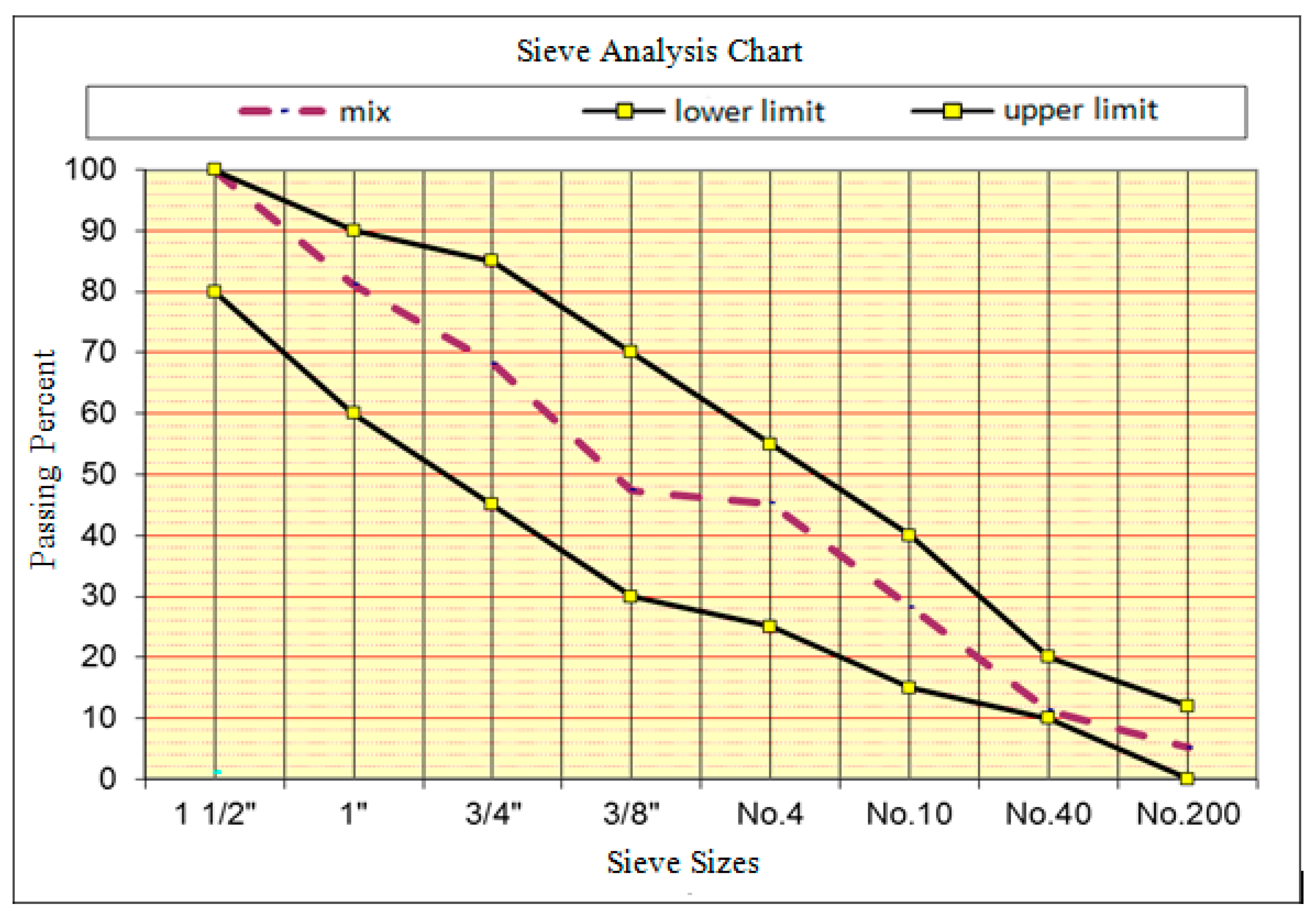

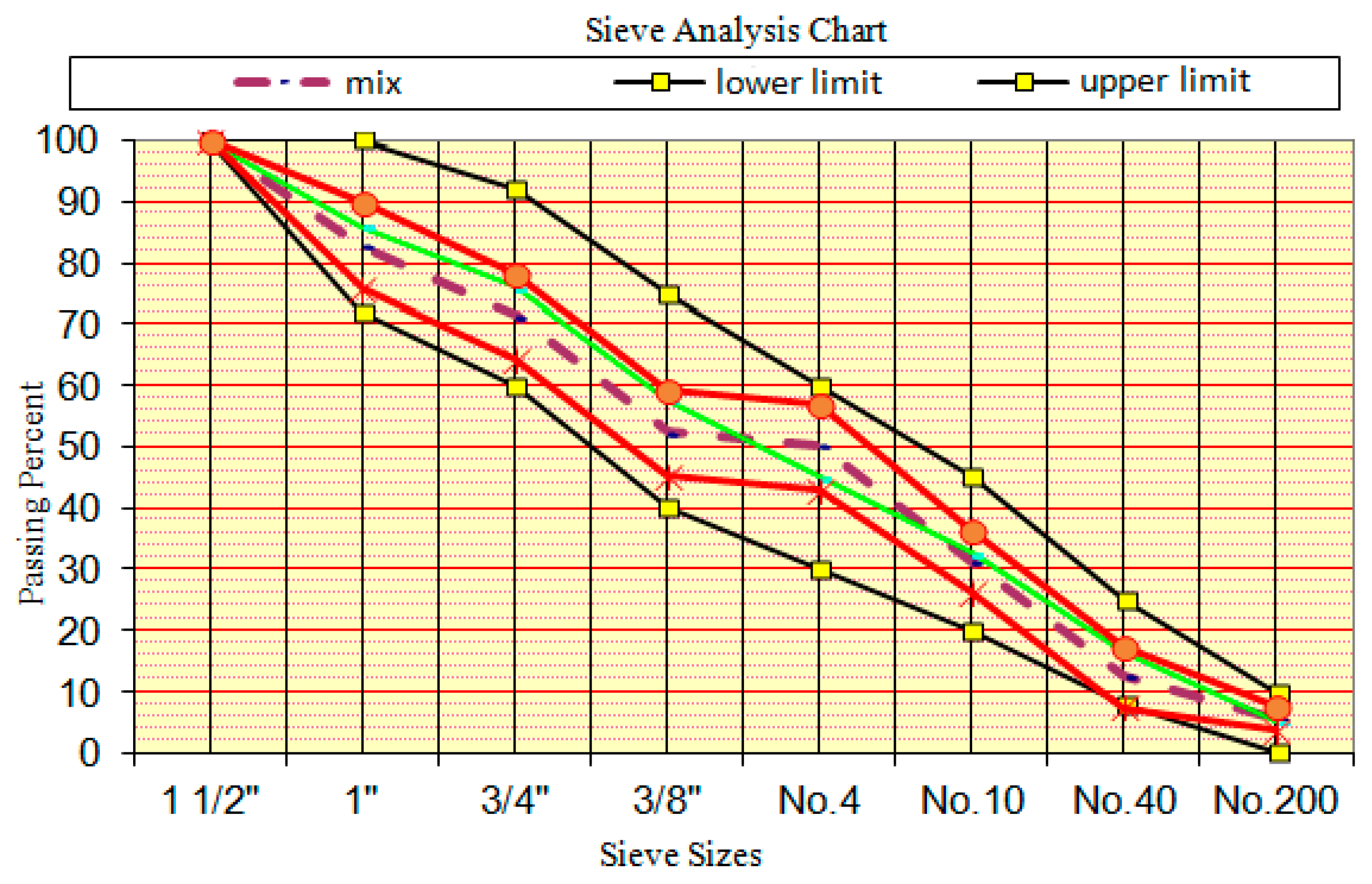

4.3. Optimization Perspective for Mixture Design

4.4. Future Prospects and Process Simulation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acar, M. Chemical and Mineralogical Properties of Karacadağ Basalt. J. Geol. Sci. 2002, 15, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Daniş, A. Diyarbakır ve Çevresindeki Bazaltların Beton Agregası Olarak Değerlendirilmesi. İnşaat Malzemeleri Derg. 2019, 8, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Mohajerani, A.; Giustozzi, F.; Kurmus, H. Sustainability assessment of using recycled aggregates in road pavements. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijerathne, D.; Wahala, S.; Illankoon, C. Impact of Crushed Natural Aggregate on Environmental Performance in Sri Lanka. Builings. 2024, 14, 2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bortoli, A. Understanding the environmental impacts of virgin aggregates: Critical literature review and primary comprehensive Life Cycle Assessments. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.10457. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Global Material Flows and Resource Productivity: Assessment Report for the UNEP International Resource Panel; United Nations Environment Programme: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sözen, M. Diyarbakır Surları: Tarihsel ve Yapısal Değerlendirme. Tarih Toplum Derg. 1971, 5, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kanat, T. Diyarbakır Surlarında Kullanılan Taş Malzeme ve Teknik Özellikleri. Restorasyon Derg. 1996, 3, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gümüşçü, S.; Turgut, P. Investigation of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Karacadağ Basalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 34, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefond, S.J. Industrial Rocks and Minerals; American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Dağtekin, E. Diyarbakır Kenti Kimliğinde Bazalt Taşının Rolü ve Korunması. Mimar. Kent Araştırmaları Derg. 2017, 4, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kilumile, M.; Fernández, L.; Segarra, M. Recycled Aggregates in Historical Repair Mortars: Performance in Hydraulic Lime Binders. Materials 2020, 13, 3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uz, A. Sert Taşların Sınıflandırılması ve Özel Kullanım Alanları. MTA Derg. 1990, 111, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Karadağ, H.; Fırat, S.; Işık, N.S. Utilization of steel slag as road base and subbase material. J. Polytech. 2020, 23, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünsal, A. Türkiye’de Volkanik Kayaçların Yayılışı ve Özellikleri. Türkiye Jeol. Bülteni 1993, 36, 289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Dursun, F.; Topal, T. Material Properties of Basalt Used in the Diyarbakır City Walls. In Les Jardins de l’Hevsel, Paradis Intranquilles; Assénat, M., Ed.; Institut Français D’études Anatoliennes: Beyoğlu, Türkiye, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, M.; Tuncer, K.; Güler, H. Geotechnical Evaluation of Local Volcanic Aggregates. Geomech. J. 2020, 18, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lu, H.; Qing, G.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y. Evaluating the Anti-Skid Performance of Asphalt Pavements with Basalt and Limestone Composite Aggregates: Testing and Prediction. Buildings 2024, 14, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, A. Engineering properties of basalt aggregates in terms of use in granular layers of flexible pavements. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C837-09; Standard Test Method for Methylene Blue Index of Clay. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- Lagaly, G. Methylene Blue Test for Characterization of Clay Minerals and Their Surfaces. Clay Miner. 1993, 28, 387–395. [Google Scholar]

- Jepsen, R.A.; Lick, W.; McNeil, J. Estimating Clay Content in Fine Aggregates Using Methylene Blue Test. J. Test. Eval. 2003, 31, 283–289. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C131/C131M-20; Standard Test Method for Resistance to Degradation of Small-Size Coarse Aggregate by Abrasion and Impact in the Los Angeles Machine. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- EN 1097-2; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates—Part 2: Resistance to Fragmentation. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- ASTM C88/C88M-18; Standard Test Method for Soundness of Aggregates by Use of Sodium Sulfate or Magnesium Sulfate. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- EN 1367-2; Tests for Thermal and Weathering Properties of Aggregates—Part 2: Magnesium Sulfate Test. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2009.

- ASTM D1883-16; Standard Test Method for CBR (California Bearing Ratio) of Laboratory-Compacted Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- General Directorate of Highways (KGM). Highway Construction Technical Specifications; Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure: Ankara, Türkiye, 2022.

- American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). Standard Specification for Materials for Aggregate and Soil–Aggregate Subbase, Base, and Surface Courses (AASHTO M 147); AASHTO: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Uğur, İ.; Polat, H.; Arslan, M. Mechanical Performance of Volcanic Rocks in Infrastructure Applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 305, 124735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, C.R.; Glass, S.V.; Zelinka, S.L. Moisture Redistribution in Full-Scale Wood-Frame Wall Assemblies: Measurements and Engineering Approximation. Buildings 2020, 10, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuğrul, A.; Zarif, I.H. Correlation of Mineralogical and Textural Characteristics with Engineering Properties of Selected Granitic Rocks from Turkey. Eng. Geol. 1999, 51, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özaydın, K.; Topçu, İ.B. Don Olaylarının Yol Yapılarındaki Etkileri Üzerine Laboratuvar Değerlendirmesi. Yapı Teknol. Elektron. Derg. 2013, 9, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, Z. Stabilizasyon Malzemelerinin Yol Üstyapısındaki Uygulamaları Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme. İnşaat Mühendisliği Derg. 2018, 25, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Çoban, A.; Demir, M.; Sezer, A. Weathering Resistance of Natural Stones in Freeze–Thaw Environments. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2019, 165, 102793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Code | Description | Mixture Type | Purpose/Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| HT1 | Basalt aggregate, prepared by primary/secondary crushing | PMT | Weather resistance (MgSO4) |

| HT2 | Basalt aggregate, prepared by primary/secondary crushing | PMAT | Weather resistance (MgSO4) |

| CBR7 | Basalt mixture—compacted sample | PMT | CBR test |

| CBR8 | Basalt mixture—compacted sample | PMAT | CBR test |

| CBR9 | Basalt mixture—compacted sample | PMAT | CBR test |

| SIEVE GAPS | Material Percentage, % | Weight of Percentage in Substitution | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3/4 | 3/8 | 49.804 | 2988.22 |

| 3/8 | No.4 | 4.936 | 296.8 |

| No. 4 | 0 | 45.260 | 2715.60 |

| TOTAL | 6000.00 | ||

| Sample Name | Weight Before Experiment (g) | Weight After Experiment (g) |

|---|---|---|

| HT1 | 498.1 | 491.8 |

| HT2 | 499.6 | 485.4 |

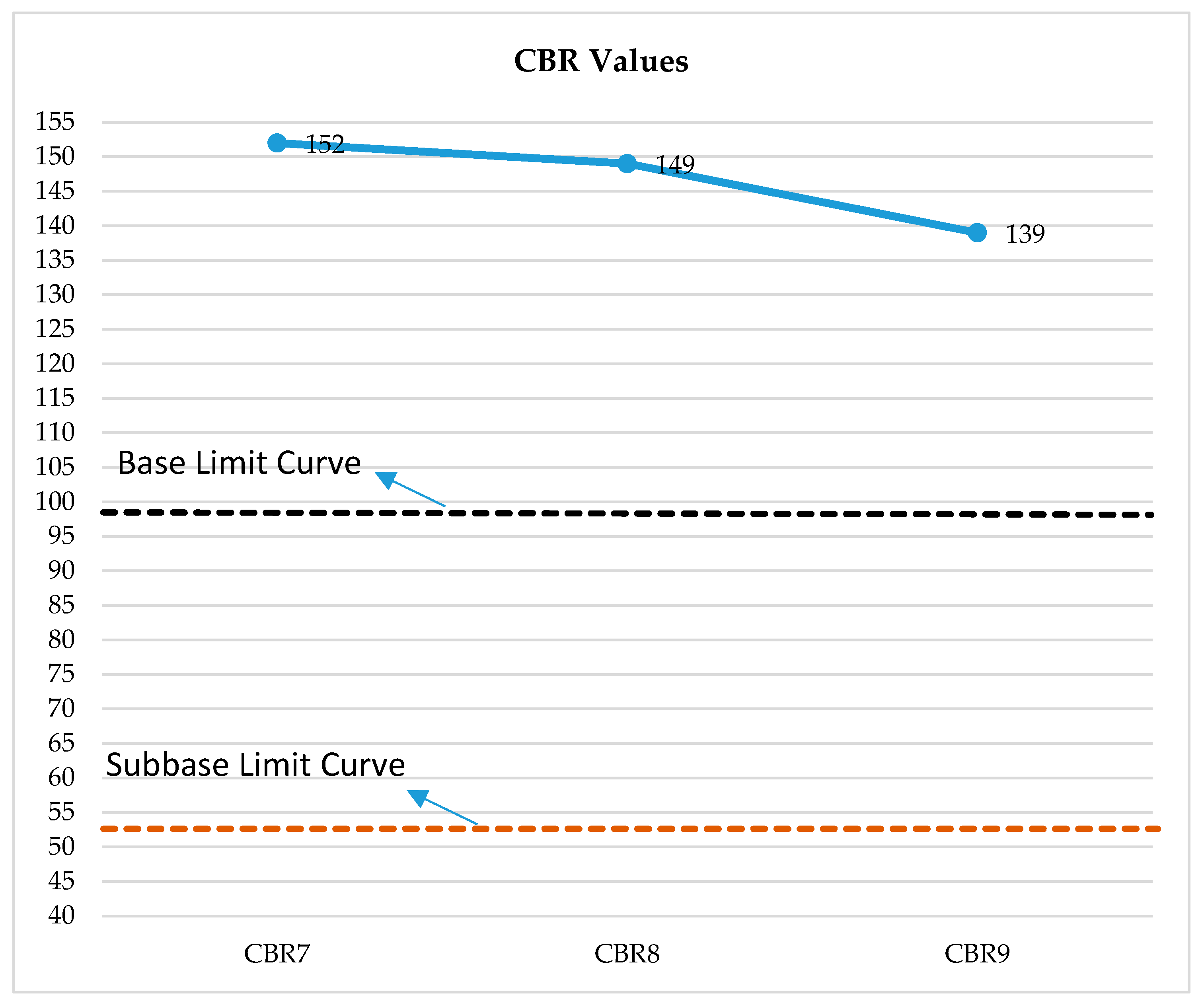

| Material Name | CBR Value | Optimum Water Content (%) | Dry Unit Volume Weight (kN/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBR7 | 152 | 5.5 | 2.242 |

| CBR8 | 149 | 4.8 | 2.230 |

| CBR9 | 139 | 4.8 | 2.223 |

| Property | Value | Standard Limit (Base/Sub-Base) |

|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles abrasion (%) | 23.3 | ≤35/≤45 |

| MgSO4 soundness loss (%) | 1.26–2.80 | ≤20/≤25 |

| Methylene blue index (MB) | 2.25 | ≤4.5/≤5.5 |

| CBR (2.5 mm, soaked) | 139–152 | ≥100/≥50 |

| Maximum dry density (g/cm3) | 2.24 | — |

| Optimum moisture content (%) | 6.5 | — |

| Swelling ratio (%) | 0.0 | ≤0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Türk, M.E.; Akyıldız, M.H. Assessment of Karacadağ Basalt as a Sustainable Material for Eco-Friendly Road Infrastructure. Processes 2025, 13, 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13093022

Türk ME, Akyıldız MH. Assessment of Karacadağ Basalt as a Sustainable Material for Eco-Friendly Road Infrastructure. Processes. 2025; 13(9):3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13093022

Chicago/Turabian StyleTürk, Muhammed Enes, and Mehmet Hayrullah Akyıldız. 2025. "Assessment of Karacadağ Basalt as a Sustainable Material for Eco-Friendly Road Infrastructure" Processes 13, no. 9: 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13093022

APA StyleTürk, M. E., & Akyıldız, M. H. (2025). Assessment of Karacadağ Basalt as a Sustainable Material for Eco-Friendly Road Infrastructure. Processes, 13(9), 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13093022