Abstract

The development of efficient strategies for optimizing and controlling nonlinear bioprocesses remains a significant challenge due to their complex dynamics and sensitivity to operating conditions. This work addresses the problem by proposing a two-step methodology applied to a laboratory-scale fed-batch bioethanol process. The first step employs a dynamic optimization approach based on Fourier parameterization and orthonormal polynomials, which generates smooth and continuous substrate-feed profiles using only three parameters instead of the ten required by piecewise approaches. The second step introduces a controller formulated through basic linear algebra operations, which ensures accurate trajectory tracking of the optimized state variables. Simulation results demonstrate a increase in ethanol concentration at the end of the process, together with an accumulated tracking error of only under nominal conditions. In addition, the closed-loop strategy outperforms open-loop implementation when the initial conditions deviate from their nominal values. These findings highlight that the proposed methodology reduces mathematical complexity and computational effort while producing continuous control profiles suitable for practical application. The combination of optimization and algebraic control thus provides a promising alternative for improving the efficiency of bioethanol-production processes.

1. Introduction

The demand for better and more versatile products, combined with the need for flexible and intelligent manufacturing processes, has driven the development of tools that provide rapid solutions [1]. Process engineering is the scientific discipline that integrates scales and components to describe the behavior of physicochemical systems. It focuses on developing systematic techniques for modeling, designing, and controlling processes, which are then applied in various fields. These procedures enable the resolution of complex problems through process optimization and product design, and their importance has grown in response to global challenges like climate change and sustainable resource management [2,3]. Among the different applications of process engineering, bioethanol production has gained particular relevance due to its role as a renewable fuel alternative and its contribution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. However, achieving efficient and stable large-scale bioethanol production still requires advances in optimization and control strategies [4,5,6,7].

One of the greatest challenges in process engineering is working with non-linear systems. These processes are characterized by complex dynamics involving many time-dependent variables that are difficult to measure online, imprecise mathematical models, parametric uncertainties, and sensitivity to external disturbances [8,9]. Bioprocesses clearly exemplify these challenges, particularly with the increasing demand for large-scale production of fermentation-derived products, such as bioethanol, biogas, and organic acids, which are vital across sectors including biofuels, nutrition, health, and pharmaceuticals [10,11,12]. Since these processes involve living organisms, it is crucial to ensure suitable operating conditions to prevent cell inhibition, loss of viability, and the production of undesirable metabolites [13]. Consequently, the development of advanced strategies for process optimization and control has become increasingly critical to the quest to guarantee both high productivity and process stability [14].

In recent years, the focus of nonlinear process optimization has increasingly shifted towards open-loop optimal control techniques [15]. These approaches aim to identify the control profile that either minimizes or maximizes a specific performance index. Once these optimal profiles are obtained, they must be implemented through a closed-loop control method [16]. Some researchers have explored the use of machine learning in both optimization and control. However, these techniques face certain limitations when applied to bioprocesses that must be addressed before the desired outcomes can be achieved [17,18]. In addition, open-loop solutions are highly sensitive to modeling errors and disturbances, whereas most machine learning-based approaches still lack transparency and robustness for industrial implementation. These limitations highlight the need for alternative methodologies that combine mathematical simplicity, reduced parameterization, and reliable trajectory tracking.

Optimal-control problems are generally addressed using two primary types of methods: analytical and numerical. Analytical approaches involve segmenting the time axis into intervals and obtaining symbolic expressions for the control inputs, but these approaches quickly become impractical for nonlinear or large-scale systems due to the complexity of the resulting equations. Numerical methods, in contrast, convert infinite-dimensional problems into finite-dimensional ones through discretization, which makes them more suitable for engineering applications with nonlinear dynamics. These methods are further classified into indirect methods, direct methods, and dynamic programming, with direct methods being the most widely applied in practice [16]. However, even direct approaches often require fine discretization and a large number of decision variables, leading to high computational costs and difficulties in tuning when they are applied to bioprocesses such as bioethanol production [19]. This motivates the search for alternative formulations capable of reducing the number of parameters while still ensuring accurate trajectory tracking.

In control systems, a significant challenge is the limited data often available during process development. The level of process understanding is directly related to the performance and reliability of the chosen control strategy [13]. Accordingly, many approaches have been suggested. Open-loop control (OLC), a straightforward and traditional technique, does not require online measurements, as it relies on predefined operating conditions, but it is generally ineffective for complex and time-varying bioprocesses [19,20]. Closed-loop control (CLC) systems overcome these limitations by incorporating feedback mechanisms, with the proportional–integral–derivative (PID) controller remaining the most widely used solution due to its simplicity and ease of tuning. Nevertheless, PID controllers are best suited for linear systems and show limited performance in tracking nonlinear trajectories [13,21]. To address these issues, researchers have explored advanced strategies such as model predictive control (MPC), neural networks, fuzzy logic, and hybrid methods, among others [17,22,23,24]. Although they are promising, these techniques often require extensive computational resources, large datasets for training, or complex tuning, which restricts their adoption in industrial bioprocesses. This situation highlights the need for alternative controllers that are mathematically simple, parameter-efficient, and capable of accurately tracking nonlinear trajectories in real applications.

In general, system optimization is typically performed independently of system control, with the two considered as two distinct stages in process design. However, several advanced frameworks attempt to integrate optimization and control simultaneously, most notably through formulations of optimal control and dynamic optimization. While such integrated approaches can enhance system responsiveness and overall performance, they are frequently accompanied by significant mathematical and computational complexity, which limits their practical applicability in nonlinear bioprocesses such as bioethanol production [19,25]. In particular, most formulations require detailed mechanistic models, fine discretization, and large numbers of decision variables, which hinder their direct use in industrial environments. This gap underscores the need for alternative strategies that can combine optimization and control in a computationally efficient manner while reducing the number of required parameters.

This work proposes a two-step strategy that integrates dynamic optimization with closed-loop control in a computationally efficient manner. Unlike previous approaches that rely on numerous parameters or generate discontinuous signals, our method produces smooth control profiles with a reduced number of decision variables that are directly applicable to physical systems without post-processing. The first step performs dynamic optimization using Fourier series and orthonormal polynomials as a compact parameterization scheme, allowing the use of static optimization tools for dynamic problems while reducing mathematical complexity. The second step introduces a nonlinear controller based on fundamental linear algebra concepts that accurately tracks time-varying reference signals through simple matrix operations. Parameter selection and tuning are performed using a hybrid algorithm that combines Monte Carlo, Genetic Algorithms, and Gradient Descent. This strategy addresses the limitations of existing optimization–control approaches (high dimensionality, sensitivity to uncertainties, and lack of practical applicability), providing an efficient and adaptable framework for bioprocesses and other nonlinear systems.

2. Mathematical Model of Bioethanol Production

The following equations describe a fed-batch process for bioethanol production using the microorganism Saccharomyces diastaticus and a feed stream consisting of equal proportions of glucose and fructose [26]. This system is classified as SIMO (Single Input, Multiple Outputs), where the input is the substrate feed flow rate (U, manipulated variable) and the outputs are the concentrations of cells (X), ethanol (), glycerol (), glucose (), and fructose () within the reactor (state variables).

To develop this model, the temperature was controlled at 35 °C, the airflow rate was set to 1.5 vvm, and the pH was maintained at . Biomass concentration was measured using spectrophotometry at 540 nm, and cell dry weight was determined through a calibration curve. The remaining variables were analyzed via high-performance liquid chromatography. The authors then applied a two-phase run-to-run optimization procedure. The results obtained will be compared with those generated using the strategy proposed in this work. Furthermore, in Equations (1) and (2), and represent the specific growth rates of yeast cells on glucose and fructose, respectively. and denote the specific ethanol-production rates from glucose and fructose, while and represent the specific glycerol-production rates. These terms describe the metabolic activity of the microorganism and link substrate consumption with product formation. The dilution terms, , account for the effect of the feeding strategy on the state variables in the fed-batch process. Equations (1) and (2) define the mathematical model of the process, which has been experimentally validated by Hunag et al. [26] and is used here as a benchmark for testing the proposed strategies. A detailed description, including parameter values and initial conditions, can be found in references [8,26].

where

3. Proposed Strategies

This section provides a detailed step-by-step explanation of the methodologies developed for optimizing and controlling the nonlinear system described in the previous section. It includes the theoretical foundations, algorithmic procedures, and implementation details necessary to achieve the desired performance and stability of the system.

3.1. Dynamic Optimization

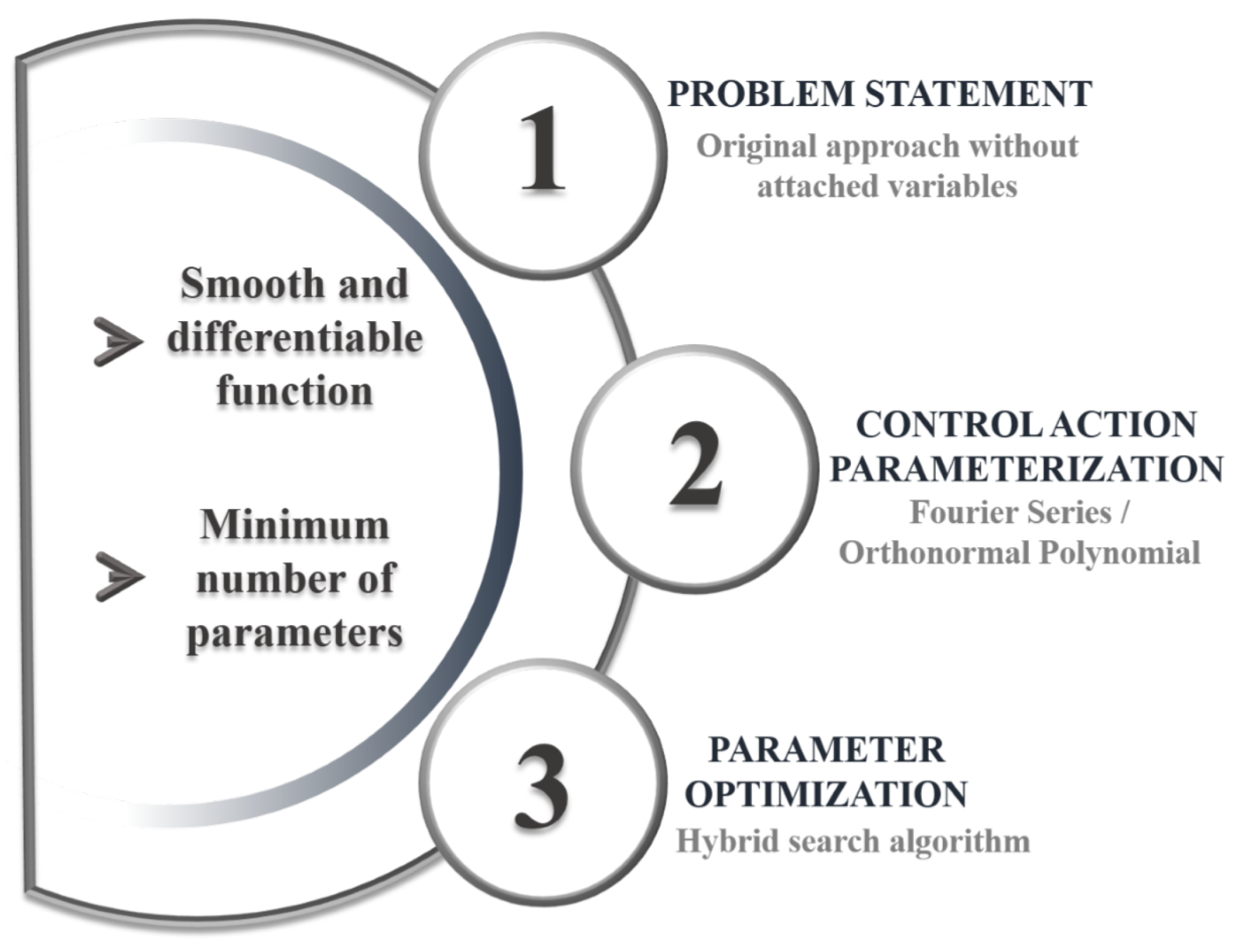

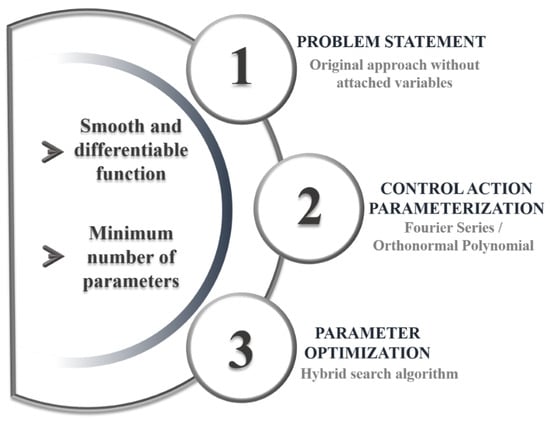

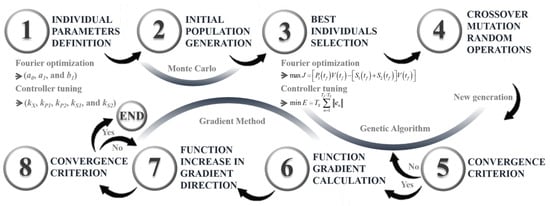

The sequential direct approach is employed here [16], preserving the original formulation of the Optimal Control Problem without the need for adjoint variables. As shown in Figure 1, the method is divided into three key phases. External disturbances are excluded at this stage, which focuses only on identifying the optimal reactor feed strategy to meet the defined objectives.

Figure 1.

Dynamic optimization-strategy diagram.

3.1.1. Optimization Problem Statement

This approach aims to determine the optimal feed-flow-rate profile (U) to achieve a specific objective. In a previous analysis [27], two different strategies were employed for dynamic process optimization: one where the control action was constrained to avoid saturation and another where saturation was allowed when the limits were exceeded. Three optimization criteria were evaluated in each case: (i) maximizing ethanol concentration at the final reaction time, (ii) maximizing ethanol production at the final time, and (iii) maximizing ethanol production while minimizing the amount of residual substrate at the final time. The analysis concluded that the best results were obtained when control action saturation was allowed, particularly under the third performance criterion (J). This objective function is selected based on industrial efficiency criteria, aiming to maximize ethanol production while minimizing residual substrates, thereby reflecting an optimal use of feedstock and reactor capacity. Combining these two goals in a single performance index ensures that both high yield and resource efficiency are achieved; these are key targets in large-scale bioethanol production. Accordingly, this work builds on that outcome, adopting the same approach.

where denotes the final time of the process, corresponding to 15.7 h [26].

The objective function will be evaluated subject to the equality constraints from the mathematical process model (see Equations (1) and (2)); the initial values of the state variables, as shown in Equation (4); and the inequality constraints on the process variables (see Equation (5)). These initial and boundary conditions are taken from the experimental data reported by Hunag et al. [26] and reflect the practical operating ranges of the fed-batch process. They ensure that the optimization respects realistic and experimentally validated process constraints.

3.1.2. Parameterization of Control Actions

The strategy proposed for parameterizing the reactor feed rate, as originally described in [28], assumes that the optimal profile exists and can be expressed as a function within the Hilbert space , where is the total duration of the process. Since is an infinite-dimensional space, its basis elements must be independent, infinite, and complete [29]. Therefore, the function representing the optimal feed rate can be expressed as a linear combination of basis elements. One such basis is the Fourier trigonometric basis (Equation (6)), which is particularly useful for representing periodic functions and capturing the cyclical nature of many practical processes. Additionally, the orthonormal polynomial basis (Equation (7)) enhances the accuracy and efficiency of function representation and analysis within the space.

where (for ) are derived through the Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization and normalization of the basis and depend on . Additionally,

where represents the inner product. Therefore, it is assumed that with these two bases, any piecewise continuous function can be generated, including the feed rate to be optimized. In the Hilbert space, the inner product between two functions x, y∈ is defined as [30]:

If it is assumed that the optimal control profile, , is represented by a continuous function, it can be approximated by a linear combination of the orthonormal basis P:

where is the approximated optimal control vector, are the polynomial coefficients, and l is its order. When the polynomial coefficients are found, the optimization problem is solved. Since the control action must be smooth and continuous, a good approximation can be achieved with only the first few terms of the Fourier series (low-frequency content), involving a limited number of parameters [30]. Consequently, this approach leverages the Fourier series’s characteristics to approximate effectively through a linear combination of the mentioned basis functions. For a continuous or piecewise continuous function, , the Fourier series expansion is given by [31]:

where h is an integer representing the number of trigonometric terms in the series and , , are its parameters. For each truncated series expansion with its respective parameters, there is a unique polynomial of order l with coefficients ; that polynomial represents a specific . Thus, the coefficients in Equation (10) are obtained by matching Equations (10) and (11):

Thus, by finding the Fourier parameters that construct the control action vector Equation (10) to maximize the objective function, Equation (3), the initially stated optimization goal is achieved.

The described procedure can be summarized in the following steps:

- Specify the number of Fourier terms to use, m, and define the number of parameters as (for a smooth and continuous signal, three terms are sufficient); coincides with the number of coefficients in the polynomial of Equation (10), thereby setting its order, l.

- Establish the range of values the Fourier parameters can take, assuming these values lie within the bounds of the control vector (see Equation (5)). Assign initial values to the parameters, within the defined limits, using any random search algorithm (e.g., Monte Carlo).

- Perform orthogonalization of the basis P using the Gram–Schmidt process over the time interval , then perform normalization.

- Optimize the Fourier parameters using a chosen algorithm.

Steps 4, 5, and 6 are repeated iteratively until the results converge. Finally, the optimal control action for the given problem is obtained. It is worth noting that this dynamic optimization strategy is not limited to smooth function searches, as non-uniform (but still continuous) profiles can be obtained by adding terms to the Fourier series and consequently increasing the polynomial order. The overall procedure of the dynamic optimization strategy is schematically illustrated in Figure 1.

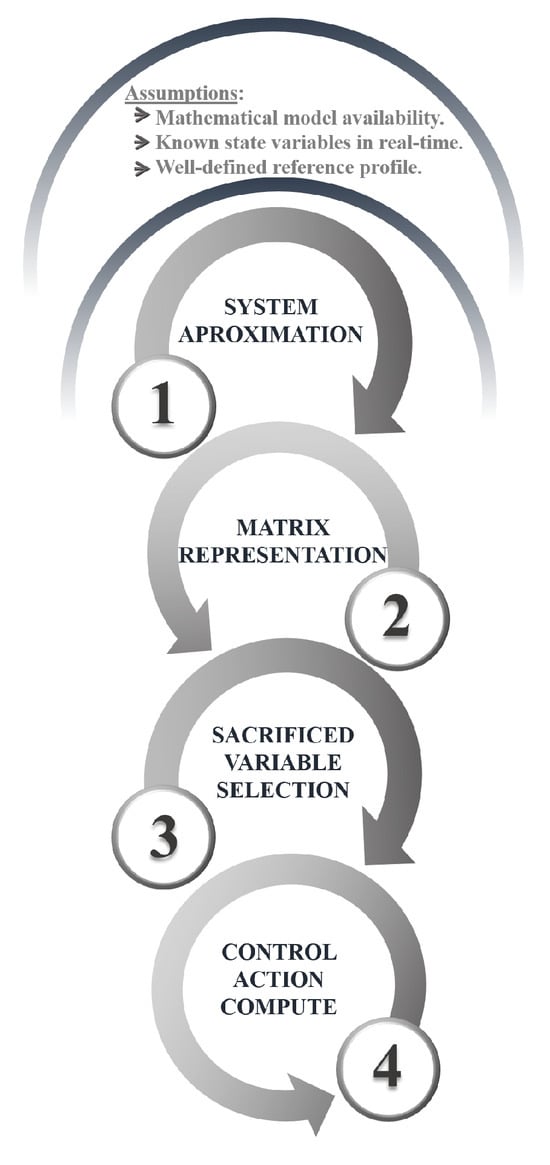

3.2. Non-Linear Control

Once the optimal-feed profile for the reactor is obtained, it is crucial to have a robust control system that ensures precise tracking of this profile. To achieve this, a control methodology based on linear algebra and numerical methods is implemented [32]. Rather than applying open-loop control actions obtained from optimization, the controller uses the optimized state variables as reference signals for CLC. This strategy is based on three key assumptions: (i) the availability of a mathematical model that accurately represents the dynamic behavior of the system, (ii) the ability to measure all relevant state variables in real time, and (iii) the existence of a well-defined reference profile (in this case, the one obtained through the previously described optimization). This approach ensures precise control and adaptability to potential disturbances or variations in operating conditions. The control-implementation process is outlined below.

First, the differential equations of the mathematical model are presented in a general form, with each state variable represented by . Then, these equations are solved using numerical integration with an appropriate method. At this stage, there is no need to employ highly complex numerical methods; even the Euler method, known for its simplicity, yields satisfactory results while minimizing computational effort. This choice ensures process efficiency without sacrificing the accuracy of the results.

In Equation (13), n is the current measurement instant, while denotes the next. represents the sampling time, which is set at 0.1 h, following the recommendations of [33]. This value ensures that no significant events are missed while minimizing errors and maintaining a balance with computational cost. The process takes 15.7 h to complete, during which time the sampling intervals allow for precise monitoring and control.

Since the state variables at are unknown, they are approximated using a function of the error at time n. This approach expresses the unknown variables, , in terms of the known quantities: ; the references () at times n and ; and a constant, (different for each state), determined by tuning the controller using parameter search strategies, which will be explained in Section 3.3:

Combining Equations (13) and (14), it is possible to approximate the differential equations of the mathematical model.

If Equation (15) is substituted into Equation (1), the non-linear system is represented by linear equations. Additionally, it can be expressed in matrix form by representing the state variables as functions of U, simplifying the calculation of the control action (see Equation (16)).

To facilitate the analysis, Equation (16) will be expressed as follows:

If U is to be determined, the system needs to have an exact solution. That is to say, b must be a linear combination of the columns of A [34,35], meaning A and b must be parallel, so the angle between A and b must be zero.

In Equation (18), the symbols and represent the inner product and the norm of vectors in the space, respectively. Then, to solve Equation (18), a sacrificed variable, denoted by the subscript , is introduced. The sacrificed variable is specific in the system whose desired value is not its reference value but is instead adjusted to ensure that the system of equations has an exact solution. Unlike other variables, which aim to reach their reference values, the sacrificed variable adapts dynamically to balance the system. Once the system reaches the reference point for the other variables, the desired value of the sacrificed variable gradually converges to its reference value. Choosing this variable requires careful consideration of each variable’s role in the process. In bioprocesses, the substrate concentration, which can be controlled by adjusting the flow rate, has a direct impact on the rate of substrate consumption, cell growth, and the production of products or byproducts [36]. In this case, interactions between two types of sugars, glucose and fructose, are taken into account. However, several studies indicate that glucose has a more significant effect than fructose. Therefore, was selected as the sacrificed variable.

By replacing with in Equation (16) and applying the parallelism condition from Equation (18), the sacrificed variable can be identified and the control action () can then be computed at any sampling time using the least squares method [34].

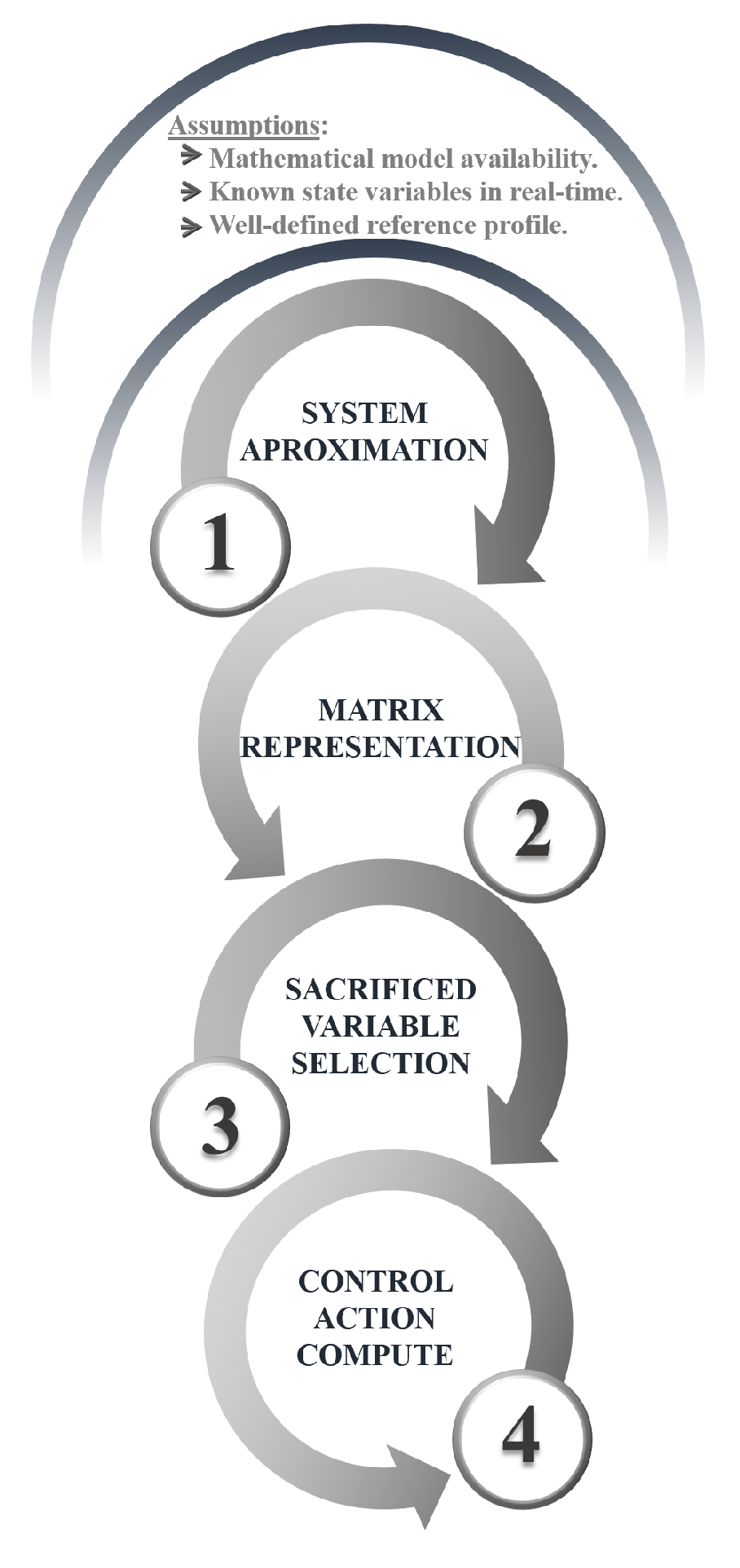

It is important to highlight that a key advantage of this technique is its versatility, as it can be applied to various systems, including both single-input multiple-output (SIMO) and multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) configurations, provided the necessary information is available. Figure 2 summarizes the steps for implementing the linear-algebra-based controller.

Figure 2.

Procedure for a linear-algebra-based controller.

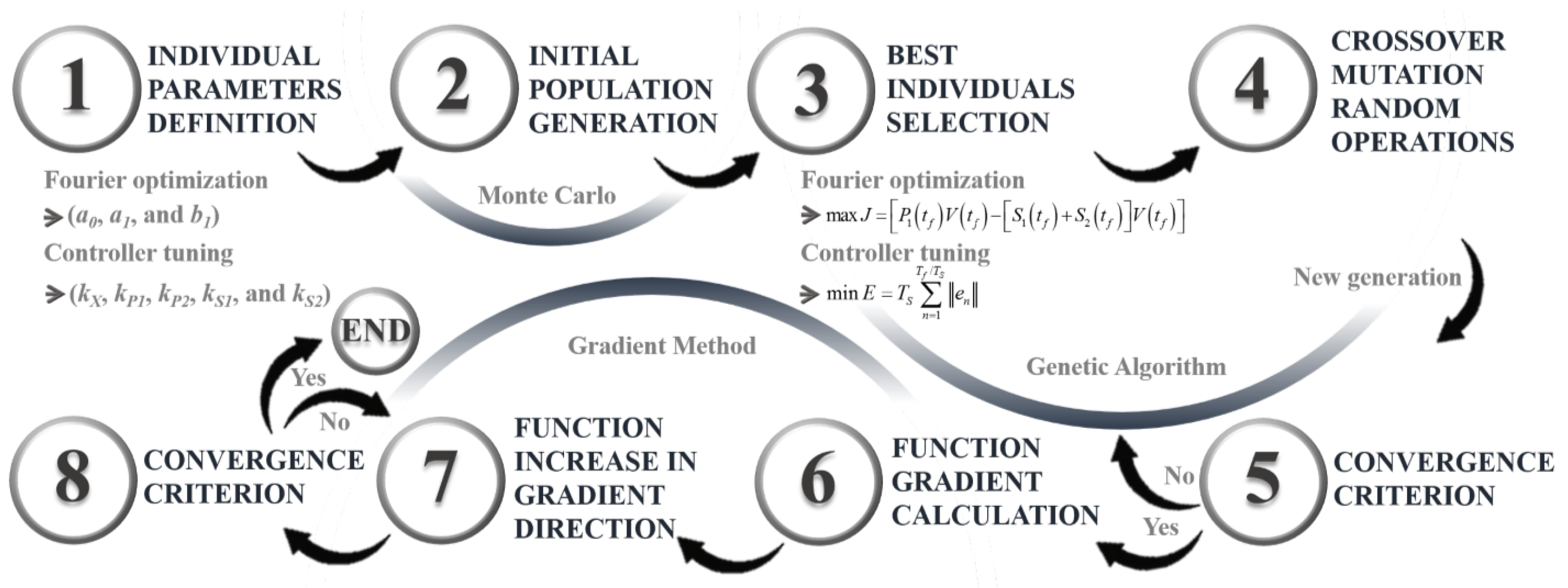

3.3. Tuning Hybrid Search Algorithm

An improvement to a hybrid algorithm presented in a previous work [37] is proposed. This algorithm combines the Monte Carlo random method with Genetic Algorithms and the Gradient method. This procedure is used to find the parameters that describe the optimal feed-rate profile for the bioreactor (U; see equations Equations (10)–(12)), as well as to tune the linear-algebra-based controller. In this context, an “individual” represents either the set of Fourier parameters (, , and ) or the set of controller parameters (, specifically: , , , , and ).

Monte Carlo is a simulation and statistical analysis technique used to solve complex problems and estimate results through random sampling [37]. In this context, it is employed to generate the initial population of individuals for the genetic algorithm. An elitist methodology is applied to select the most capable individuals. The general procedure involves forming random sets of parameters, where each set (individual) is evaluated by simulating the process and calculating the corresponding objective function (Equation (3) for Fourier optimization and Equation (20) for controller tuning).

where is the control tracking error, calculated as follows:

In Equation (21), the prefix “max” represents the maximum value of the reference variables, ensuring that each term in the sum has equivalent dimensions and that all variables hold equal importance in the minimization process.

The Genetic Algorithm is an optimization-and-search technique based on principles of biological evolution and genetics, inspired by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and genetic reproduction [37]. In its implementation, the set of individuals generated by Monte Carlo is used, and a smaller group (the initial population) consisting of individuals with the best objective function values is selected. Once the individuals are chosen, crossover and mutation operations are performed. A single-point crossover is applied, where a random crossover point is identified before the parents are split to produce offspring by swapping their tails. The goal of the crossover is to improve the fitness of the offspring compared to their parents. During mutation, a random position in the chromosome is selected and its value is randomly changed. Additionally, at each iteration, a series of random individuals is introduced to prevent convergence to a local extreme. Each individual in the population is evaluated based on the objective function, and the best-performing ones are selected in each generation. These steps are repeated for a set number of iterations or until a convergence criterion is met.

The gradient method is an optimization technique used to find local or global extrema of a function [38]. Since the gradient of a function is a vector that points in the direction of maximum growth at a given point, this technique follows the gradient direction in each iteration to locate an extreme. In this case, the procedure starts with the best individual obtained from the genetic algorithm, reducing the likelihood of converging to a local extreme. The gradient of the function at this point is calculated using partial derivatives, and the individual is updated by multiplying the gradient by a learning factor. This process is repeated until a convergence criterion is satisfied. Figure 3 provides a step-by-step summary of this parameter-optimization process using a hybrid search algorithm.

Figure 3.

Hybrid search algorithm.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. System Optimization

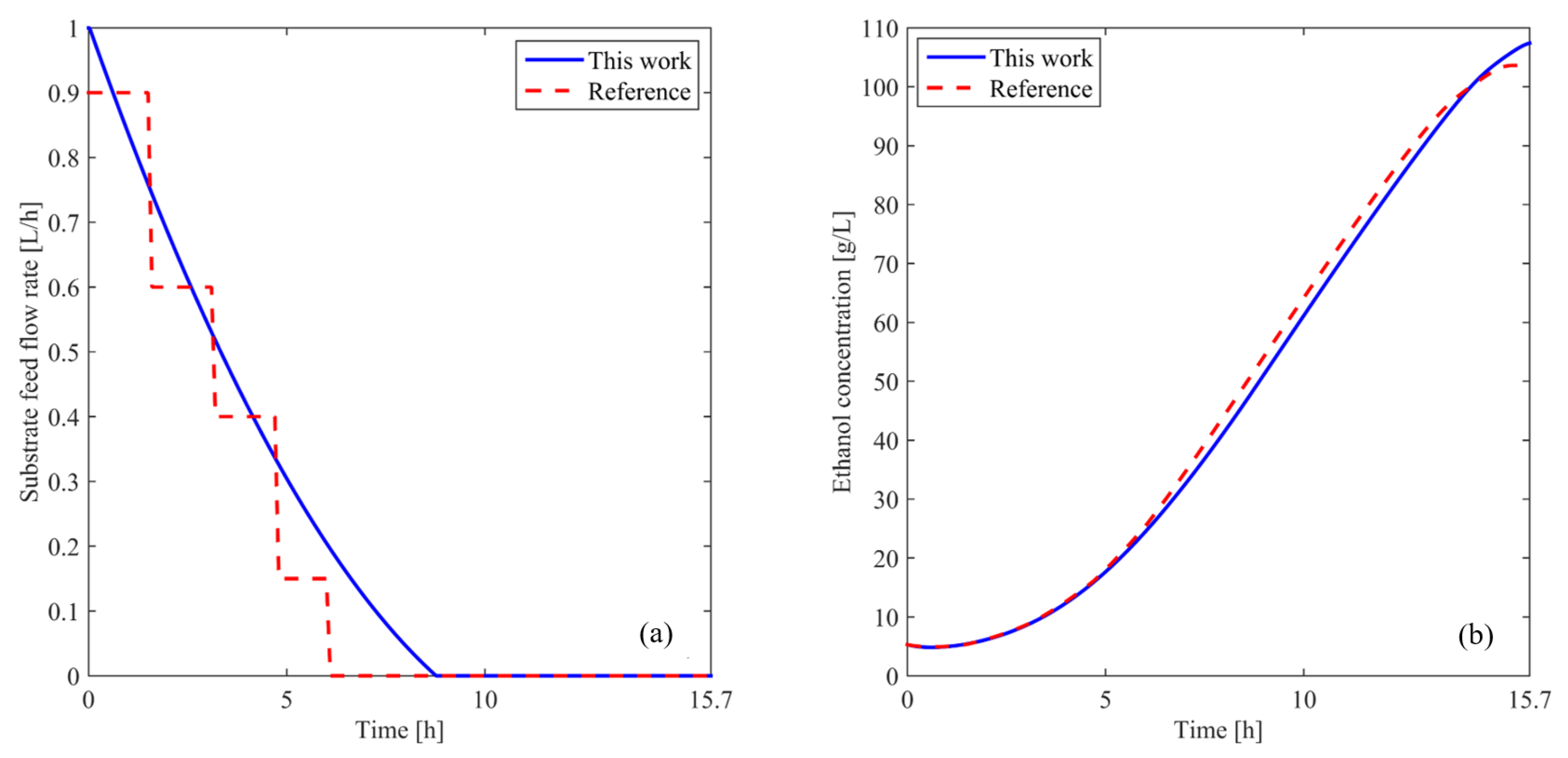

To optimize bioethanol production, the described algorithms were simulated using MATLAB® R2020 and Simulink®. A comparison was then made between the obtained results and those presented in [26]. Notably, to ensure a fair comparison, the same final time, constraints, model parameters, and initial conditions from the referenced study were used.

In [26], the authors implement a two-phase run-to-run optimization procedure. During the first phase, the kinetic parameters of the model are identified, while in the second phase, the optimal feed rate, glucose and fructose concentrations, and fermentation time to maximize ethanol production are determined. To approximate the substrate feed rate, they use a piecewise parameterization approach, normalizing the reaction time and dividing it into 10 subintervals. In each subinterval, a constant optimal value for the control vector is obtained. The methodology used to determine these parameters is a hybrid differential evolution algorithm. The main drawbacks of this approach are the large number of parameters that need to be optimized and the extensive number of simulations required. Additionally, the optimal profile is not smooth, requiring a post-processing smoothing step for practical implementation in a real system, which leads to a suboptimal solution. The optimal ethanol yield reported in [26] was 103.63 g/L.

In this research, the substrate feed flow rate was parameterized following the procedure outlined in Section 3.1.2. Subsequently, using the hybrid algorithm developed in Section 3.3, the parameters , , and were optimized, varying these parameters within the control action limits as an initial adjustment. To evaluate each algorithm iteration, the objective function defined in Equation (3) was used; this function maximizes ethanol production while minimizing residual glucose and fructose in the reactor at the end of the process.

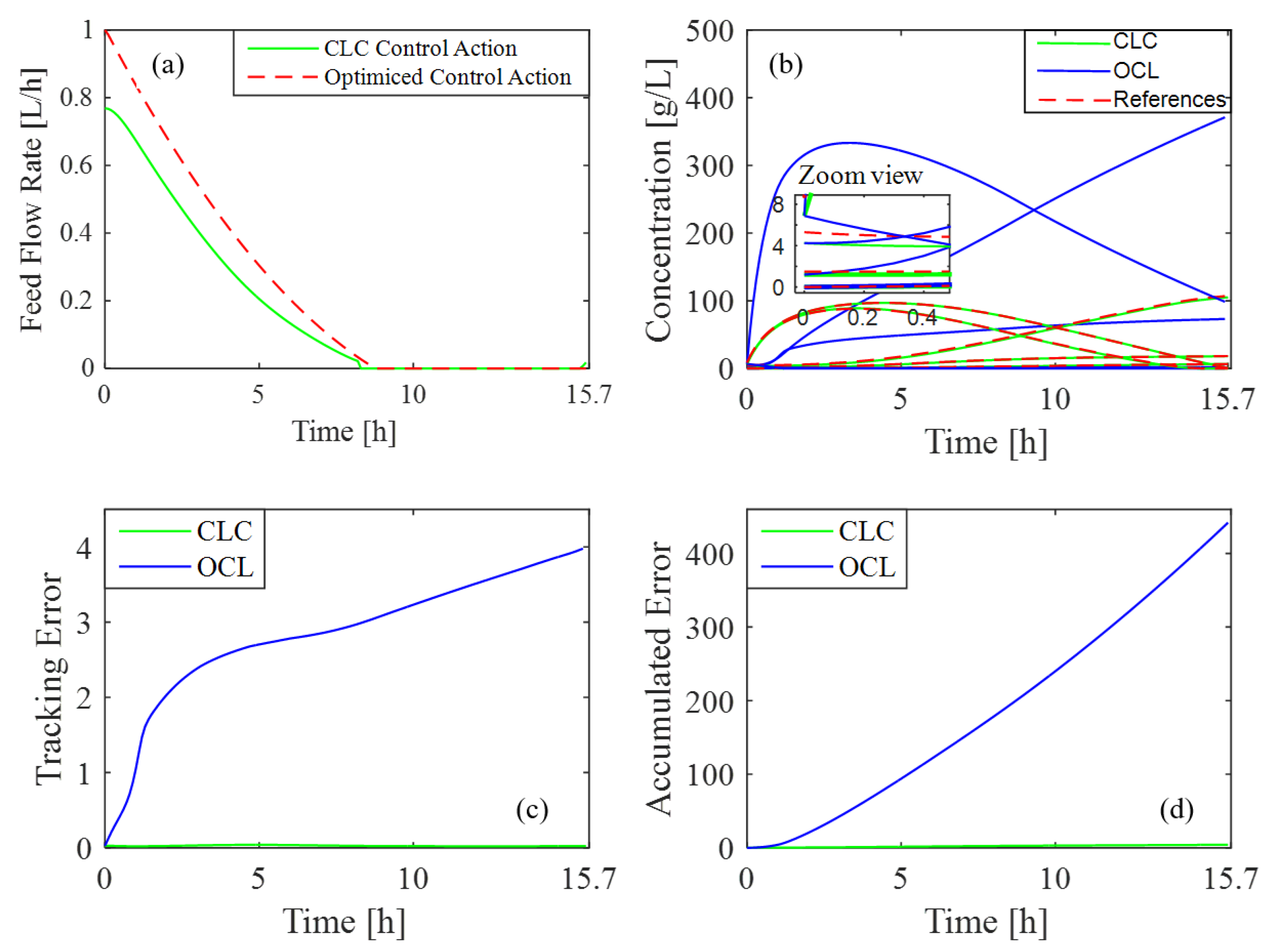

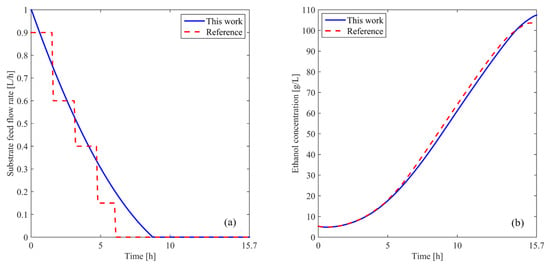

Figure 4a shows the obtained substrate feed rate compared with the one reported in the reference. As can be seen, the result achieved with the proposed strategy presents a smooth and continuous profile, allowing its direct application in the real system without the need for signal-smoothing filters. Moreover, only three parameters are used for optimization, whereas [26] employs at least ten, demonstrating the efficiency and simplicity of the approach. It is worth noting that the entire proposed algorithm involves approximately 3500 iterations, with a simulation time of around 3 min, highlighting the computational feasibility of the method.

Figure 4.

(a) Optimal substrate feed flow rate. (b) Ethanol concentration in the reactor. The blue solid line represents the results from this work, while the red dashed line shows the reference data.

Figure 4b illustrates the ethanol-concentration profile obtained after simulating Equations (1) and (2) using the control actions shown in Figure 4a in comparison with the reference [26]. An improvement in the final ethanol concentration of can be observed when the Fourier technique is used. The proposed strategy enhances ethanol yield under varying operational conditions, making it adaptable to different scales of bioethanol-production processes. These results strongly support the efficiency, precision, and practical applicability of the proposed approach for solving the established problem. The improvements observed in the results are attributed to a more precise implementation of the algorithms and a deeper understanding of the system dynamics, which allow for enhanced performance compared to previous analyses [27].

4.2. System Control

4.2.1. Evaluation of the Controller Under Normal Operating Conditions

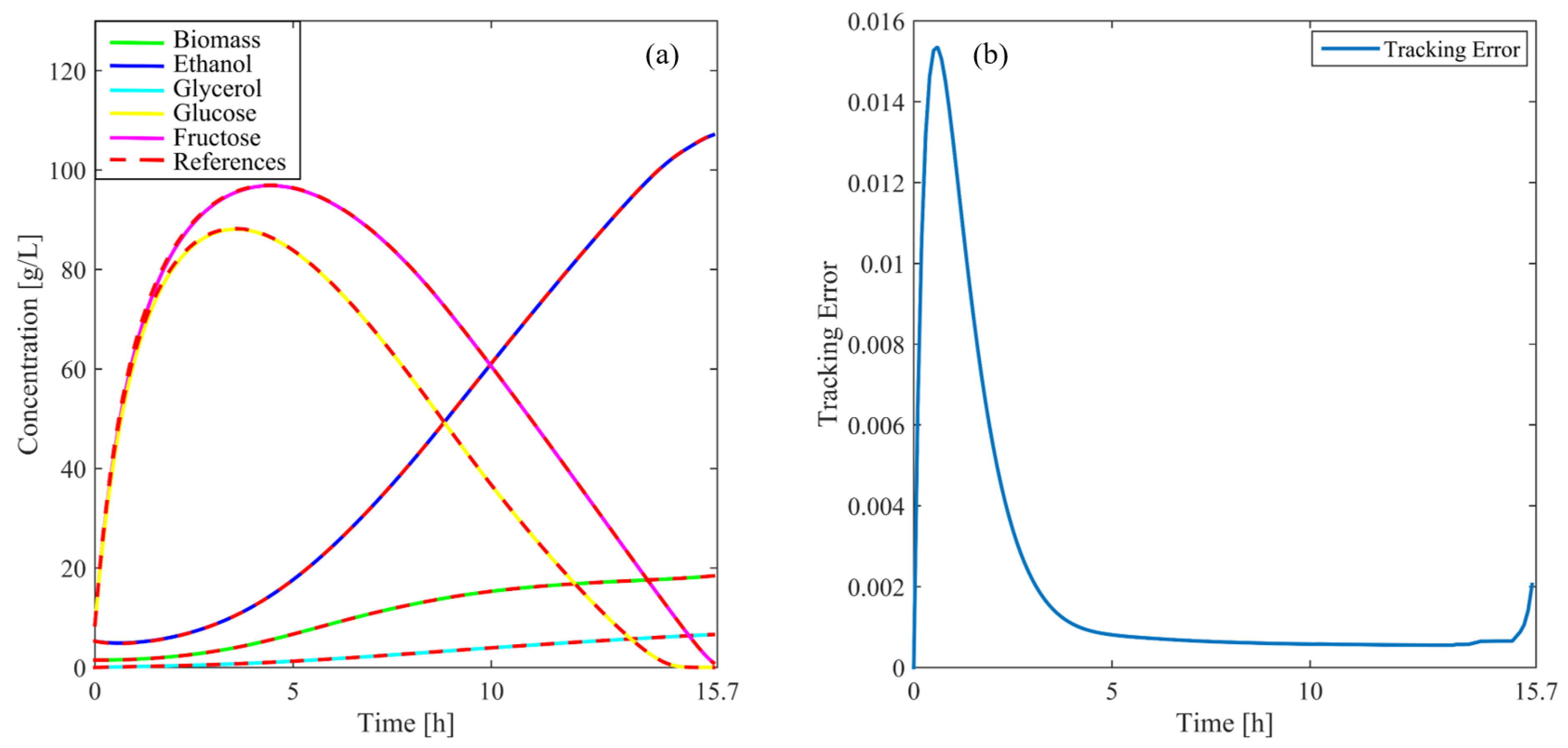

At this stage, the performance of the controller under normal conditions was assessed through a closed-loop simulation of the process, utilizing data from Equation (1) and Figure 4a, with no external disturbances affecting the system. The primary objective of this simulation was to evaluate the behavior of the controller under ideal conditions and establish a reference for future comparisons.

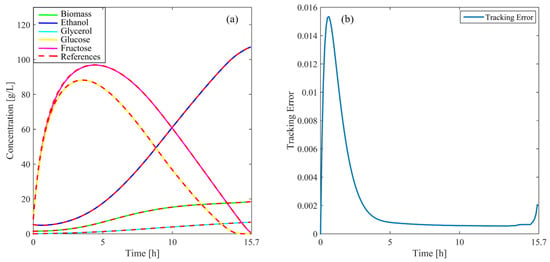

Figure 5 illustrates the concentration profiles for cells, ethanol, glycerol, and fructose throughout the simulation. These profiles closely follow the reference values, showcasing the precise ability of the controller to track the state variables of the system. The high degree of accuracy achieved highlights the capacity to maintain stable and efficient process control. Moreover, Figure 5 displays the evolution of the tracking error (, Equation (21). As the process advances, the error decreases steadily, remaining within very low limits. This indicates that the controller effectively minimizes deviations from the reference, continuously tending toward the target values as the simulation progresses. The low magnitude of the tracking error underscores the stability and robustness of the controller under nominal conditions. Additionally, the smooth adaptation to system dynamics demonstrates its capacity to maintain optimal performance without compromising control precision.

Figure 5.

(a) variables of the process compared with reference values under normal operating conditions, (b) tracking error over time.

These findings confirm that the controller not only successfully meets the desired set points but also efficiently manages any inherent fluctuations within the system. The performance observed under normal conditions provides a strong foundation for additional evaluations under more challenging scenarios, such as those involving the introduction of disturbances, parameter variations, or unexpected fluctuations in the feed flow rate. These scenarios, previously tested in [24], have also yielded excellent results, further validating the robustness and versatility of the controller.

4.2.2. Controller Evaluation with Perturbations in the Initial Conditions

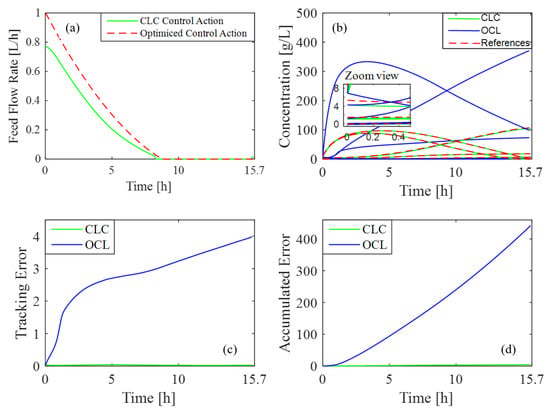

As previously mentioned, the application of open-loop control actions derived from optimization is quite common. In contrast, the proposed controller adopts a different approach, using optimized state variables as reference signals for CLC. To demonstrate the advantages of this controller over the OLC alternative, a comparison is presented between the outcomes of OLC and CLC, incorporating a disturbance applied to the system’s initial conditions.

An optimal feed rate is established based on specific initial system conditions. A common challenge, however, is that these initial conditions can vary between processes, which may prevent the system from reaching a steady state. This test demonstrates that the same results can be achieved even with changing initial conditions. This is possible because the controller continuously adjusts the feed-rate profile to achieve the desired concentration profiles.

In this test, the initial conditions of the process are reduced by to assess whether the controller can appropriately adjust the reactor feed rate to align with target references. Figure 6b shows how the desired concentration profiles meet the reference values under these altered initial conditions. Figure 6a highlights the necessary variations in feed rate to sustain accuracy. Additionally, Figure 6c and Figure 6d illustrate the differences in tracking and accumulated error achieved in CLC and OLC, respectively. The disparity in errors is evident and is primarily due to the feedback mechanism in CLC, which continuously adjusts the control action based on real-time system output. In contrast, OLC lacks this corrective feature, and this difference results in higher error accumulation. Furthermore, the total error achieved with CLC is , while in the case of OLC, it is .

Figure 6.

Controller response to a modification of the initial conditions: (a) feed rate variation; (b) concentration profiles vs. reference values; (c) tracking error in CLC and OLC; (d) accumulated error in CLC and OLC.

4.3. Discussion

The results demonstrate that the proposed control strategy achieves smooth and continuous feed-rate profiles, allowing direct application in real systems without post-processing, unlike previous approaches [26]. Compared with the reference, the method reduces the number of optimization parameters from ten to three while improving ethanol yield by , highlighting its efficiency and simplicity. Furthermore, the controller effectively adapts to variations in initial conditions, showing robust performance and low tracking error.

Overall, the analysis provides a comprehensive understanding of system behavior and illustrates the potential of the strategy for optimization and practical implementation in bioethanol-production processes.

5. Conclusions

This work presents a hybrid approach combining Fourier-based dynamic optimization and a linear-algebra-based controller for fed-batch bioethanol production. From a scientific standpoint, the proposed methodology simplifies the optimization and control of nonlinear systems by reducing the number of parameters from ten to three while maintaining high performance.

In practical terms, the approach generates smooth and continuous substrate-feed profiles that can be directly applied in industrial bioprocesses, avoiding microorganism stress, minimizing tracking errors, and ensuring accurate reference tracking. The methodology also allows continuous adjustment of control actions based on real-time process signals, which enhances adaptability to varying operational conditions.

Finally, the proposed strategy provides a scalable framework that can be extended to other SIMO or MIMO bioprocesses, demonstrating its potential applicability beyond bioethanol production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.F., M.N.P. and G.S.; methodology, M.C.F., M.N.P. and G.S.; software, M.C.F.; validation, M.C.F. and G.S.; formal analysis, M.C.F., M.N.P. and G.S.; investigation, M.C.F., M.N.P., L.R. and G.S.; resources, M.C.F.; data curation, M.C.F., M.N.P. and G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.F., M.C.G. and M.L.M.; writing—review and editing, M.C.F., M.C.G. and M.L.M.; visualization, M.C.F., M.N.P. and L.R.; supervision, L.R. and G.S.; project administration, M.C.F.; funding acquisition, M.C.F., M.N.P. and G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the manuscript. No additional datasets were generated or analyzed.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out with the support of the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) and the Institute of Chemical Engineering (IIQ) at the National University of San Juan (UNSJ). The authors also acknowledge assistance in language editing by AI-based tools.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Negri, V. Life Cycle Assessment and Optimization of Carbon Dioxide Mitigation and Removal Technologies. Ph.D. Thesis, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pistikopoulos, E.N.; Barbosa-Povoa, A.; Lee, J.H.; Misener, R.; Mitsos, A.; Reklaitis, G.V.; Venkatasubramanian, V.; You, F.; Gani, R. Process systems engineering—The generation next? Comput. Chem. Eng. 2021, 147, 107252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslanbay Guler, B.; Gurlek, C.; Sahin, Y.; Oncel, S.S.; Imamoglu, E. Renewable bioethanol for a sustainable green future. In A Sustainable Green Future: Perspectives on Energy, Economy, Industry, Cities and Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 449–480. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Verma, A. Recent advances in bioethanol: Current scenario, sources and production techniques. In Microbiology-2.0 Update for a Sustainable Future; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 331–349. [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane, G.; Acharya, A.; Poudel, D.K.; Aryal, B.; Gyawali, N.; Niraula, P.; Phuyal, S.R.; Budhathoki, P.; Bk, G.; Parajuli, N. Recent advances in bioethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass. Int. J. Green Energy 2021, 18, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fansuri, H.; Purwandari, U.; Putra, S.; Adhiksana, A.; Junianto, I.D.; Oktavian, R.; Cordiner, J. A review of the technological aspects and process optimization of bioethanol production from corn stover biomass: Pretreatment process, hydrolysis, fermentation, purification process, and future perspective. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2024, 34, e22336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyia, M.A.K.; Ahmad, M.; Chen, Y.F.; Mustaqeem, M.; Ali, A.; Abbas, A.; Gondal, M.A. Trends and advances in sustainable bioethanol production technologies from first to fourth generation: A critical review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 321, 119037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.C.; Pantano, M.N.; Machado, R.A.F.; Ortiz, O.A.; Scaglia, G.J. Nonlinear multivariable tracking control: Application to an ethanol process. Int. J. Autom. Control 2019, 13, 440–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.S.; Xiao, D. Advanced Process Control. In Process Control: Engineering Analyses and Best Practices; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 169–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ceaser, R.; Montané, D.; Constantí, M.; Medina, F. Current progress on lignocellulosic bioethanol including a technological and economical perspective. In Environment, Development and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bisht, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, N.; Singh, H.; Kumar, P. Biofuel Production by Using Biomass and Its Application. In Renewable Energy and Green Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hammadi, M.; Anadol, G.; Martín-García, F.J.; Moreno-García, J.; Keskin Gündoğdu, T.; Güngörmüşler, M. Scaling bioethanol for the future: The commercialization potential of extremophiles and non-conventional microorganisms. Front. Energy Res. 2025, 13, 1565273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, A.S.; Mishra, S.; Nikita, S.; Priyanka, P. Bioprocess control: Current progress and future perspectives. Life 2021, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broda, M.; Yelle, D.J.; Serwańska, K. Bioethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass—Challenges and solutions. Molecules 2022, 27, 8717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Wang, S.; Zhong, J.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J. A review on evolutionary multitask optimization: Trends and challenges. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2021, 26, 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, M.N.; Fernández, M.C.; Amicarelli, A.; Scaglia, G.J. Evolutionary algorithms and orthogonal basis for dynamic optimization in L2 space for batch biodiesel production. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 177, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, P.P.; Galodha, A.; Verma, V.K.; Singh, V.; Show, P.L.; Awasthi, M.K.; Lall, B.; Anees, S.; Pollmann, K.; Jain, R. Review on machine learning-based bioprocess optimization, monitoring, and control systems. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 370, 128523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleckes, L.M.; Hemmerich, J.; Wiechert, W.; von Lieres, E.; Grünberger, A. Machine learning in bioprocess development: From promise to practice. Trends Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsa, Z.; Dhib, R.; Mehrvar, M. Dynamic modelling, process control, and monitoring of selected biological and advanced oxidation processes for wastewater treatment: A review of recent developments. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoodi, M.; Nassireslami, E. Control algorithms and strategies of feeding for fed-batch fermentation of Escherichia coli: A review of 40 years of experience. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 52, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, V.; Goud, H.; Sharma, P.C. Role of PID control techniques in process control system: A review. In Data Engineering for Smart Systems: Proceedings of SSIC 2021, Online, 16 October 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 659–670. [Google Scholar]

- Bannazadeh, F. Model Predictive Control for Dissolved Oxygen and Temperature to Study Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Production in Bioreactor. Ph.D. Thesis, Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hille, R.; Brandt, H.; Colditz, V.; Classen, J.; Hebing, L.; Langer, M.; Kreye, S.; Neymann, T.; Krämer, S.; Tränkle, J.; et al. Application of model-based online monitoring and robust optimizing control to fed-batch bioprocesses. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 16846–16851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benattia, S.E.; Tebbani, S.; Dumur, D. Linearized min-max robust model predictive control: Application to the control of a bioprocess. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2020, 30, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashedi, M.; Khodabandehlou, H.; Demers, M.; Wang, T.; Garvin, C. Model predictive controller design for bioprocesses based on machine learning algorithms. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunag, W.H.; Shieh, G.S.; Wang, F.S. Optimization of fed-batch fermentation using mixture of sugars to produce ethanol. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2012, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, C.; Pantano, N.; Groff, C.; Gil, R.; Scaglia, G. Bioethanol production optimization by direct numerical methods and evolutionary algorithms. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2024, 22, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, M.N.; Fernández, M.C.; Ortiz, O.A.; Scaglia, G.J.; Vega, J.R. A Fourier-based control vector parameterization for the optimization of nonlinear dynamic processes with a finite terminal time. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2020, 134, 106721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, W.E.; DiPrima, R.C.; Meade, D.B. Elementary Differential Equations; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kreyszig, E. Introductory Functional Analysis with Applications; Jonh Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Nagle, R.K.; Saff, E.B.; Snider, A.D. Ecuaciones Diferenciales y Problemas con Valores en la Frontera; Pearson Educación: Rading, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Scaglia, G.; Serrano, M.E.; Albertos, P. Linear Algebra Based Controllers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, D.V.; Smith, I.M. Numerical Methods for Engineers; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Strang, G. Linear Algebra and Its Applications; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Capito, L.; Proaño, P.; Camacho, O.; Rosales, A.; Scaglia, G. Experimental comparison of control strategies for trajectory tracking for mobile robots. Int. J. Autom. Control 2016, 10, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, S.; Calik, P.; Özdamar, T.H. Fed-batch biomolecule production by Bacillus subtilis: A state of the art review. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, C.; Pantano, N.; Godoy, S.; Serrano, E.; Scaglia, G. Optimización de parámetros utilizando los métodos de Monte Carlo y Algoritmos Evolutivos. Aplicación a un controlador de seguimiento de trayectoria en sistemas no lineales. Rev. Iberoam. Autom. Inform. Ind. 2019, 16, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, I.E. Challenges in the new millennium: Product discovery and design, enterprise and supply chain optimization, global life cycle assessment. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2004, 29, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).