Abstract

This study investigates the feasibility of adding gold nanoparticles (Au-NPs) to vanadium oxide (V2Ox) serving the hole transport layer (HTL) material oin polymer solar cells to enhance cell performance. The first part of this study used Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) as a baseline and optimized the parameters of this HTL material. Then, the V2Ox was substituted as the HTL material, and its parameters were optimized again. The second part involved incorporating an aqueous solution of gold nanoparticles (Au-NPs) with an average particle size of approximately 80 nm into V2Ox. Due to the excitation of localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) by Au-NPs, the addition of Au-NPs to the V2Ox layer can enhance the absorption efficiency of the P3HT:PCBM blended film. Therefore, compared with V2Ox alone, the solar cells with Au-NPs incorporated into the V2O5 hole transport layer demonstrate improved power conversion efficiency (PCE).

1. Introduction

Renewable energy is currently receiving widespread international attention. Among the many available energy sources, solar energy is inexhaustible and has greater potential than other renewable energy sources [1]. Based on their material properties, solar cells can be classified into silicon, inorganic, and organic solar cells. Many different types of solar cells have been extensively studied, including dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) [2], small molecule solar cells [3,4,5,6,7], and polymer solar cells [8,9,10,11].

Single-layer organic solar cells are the foundation of early solar cell research. The structure typically comprises two metal electrodes with an organic semiconductor material sandwiched between them. The electrodes are generally composed of ITO glass and low-work-function metals, and the structure is quite simple. However, this type of cell generally has low metal transmittance (only about 50%). In addition, the electrode also deactivates the excitons and the surface state of the electrode becomes the binding center of the electron hole, resulting in a smaller fill factor for this type. To improve these defects, organic P-N type and hybrid heterostructure solar cells have been developed.

The light-absorbing layer of an organic solar cell with double-layer heterojunction structure is composed of two layers. Compared with single-layer organic solar cells, the advantage of this structure is that the electrons and holes can be effectively separated at the donor/acceptor interface, and allowing the electrons and holes to be independently transmitted by the ITO and aluminum layers, effectively reducing the recombination of electrons and holes and promoting correctly contact with the electrode. However, the donor/acceptor interface is only a thin layer, it is difficult for the excitons far away from the interface to come into contact with the interface; therefore, they cannot be successfully separated into electrons and holes.

In 1995, A. J. Heeger’s team first added PCBM [(6,6)-phenyl-C61-butyricacid methyl ester] to MEH-PPV (poly(2-methoxy-5-(2′-ethyl-hexyloxy)-1,4-phenylene vinylene) as the active layer to form a hybrid heterostructure [12]. Its efficiency was close to 1%, which was much greater than that of the monolayer structure of MEH-PPV. This also became the precedent for the fabrication of bulk-heterojunction (BHJ) organic solar cells. After years of research, P3HT:PCBM has been widely adopted as the active layer material for organic solar cells [13,14]. Many important factors influence the performance of solar cells, such as the efficiency of solar light capture, the photocurrent conversion efficiency, and the charge transport capacity. The active layer material has the most direct influence on these factors. The charge transport capacity of the hole transport layer (HTL) is a further key factor directly affecting the performance of polymer solar cells, and the photoelectric conversion efficiency of solar cells can be improved by modifying the HTL material. While PEDOT:PSS is the most common HTL material, PEDOT:PSS has several drawbacks: for example, its acidity can cause corrosion and degradation at the interface between the indium-tin-oxide (ITO) conductive layer and the PEDOT:PSS HTL. In the literature on organic solar cells, many hole transport layer materials have been proposed and studied in depth [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

For thin film polymer solar cells, the thickness of the active layer must be smaller than the excitonic diffusion length. The optimal thickness of the active layer is on the order of 100~200 nm, or possibly less. Therefore, the photon absorption efficiency is limited. Plasmonics has emerged as a promising method to improve solar light harvesting for inorganic and organic solar cells [11,24,25,26]. Plasmons are the oscillations of free electrons due to the generation of a dipole into particles caused by the interaction with the light, and a resonance phenomenon arises when the frequency of the light matches the oscillation frequency of the electrons. For metallic nanoparticles, this condition is defined as localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), which increases light harvesting and thus improves the characteristics of solar cells.

To preserve the distribution of the organic molecules of the active layer, appropriately sized metallic nanoparticles are incorporated into the hole transport layer to increase light absorption.

This study is based on the commonly used conventional structure of ITO/PEDOT:PSS/P3HT:PCBM/Ga/Al. This research aims to improve the transport capacity of the hole transport layer, using V2Ox to address the shortcomings of PEDOT:PSS. V2O5 has a lower sensitivity to oxygen ions, which can reduce the oxygen ion damage to the active layer, thereby increasing the photoelectric conversion efficiency of the solar cell. To increase carrier transport efficiency, 80 nm gold nanoparticles (Au-NPs) are then incorporated into the hole transport layer, thereby enhancing the power conversion efficiency (PCE) of polymer solar cells.

2. Materials and Methods

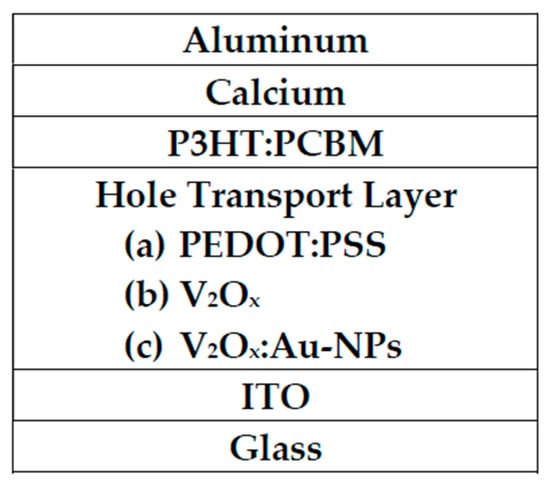

The architecture of this device presented in this study is mainly divided into three parts. Starting from the indium-tin-oxide (ITO)-coated glass, its structure from bottom to top was a hole transport layer (50 nm), a P3HT:PCBM active layer (200 ± 10 nm), and calcium (20 nm), and aluminum (100 nm). ITO was used as the transparent conducting anode while aluminum was used as the cathode due to its low work function. Figure 1 shows the structure of a polymer solar cell using PEDOT:PSS, V2Ox, or V2Ox:Au-NPs as the hole transport layer.

Figure 1.

Three polymer solar cells with different hole transport layers studied herein.

The process steps of the experiment are as follows.

2.1. Cleaning and Etching of ITO Substrates

The ITO glass substrate was cut into 2 cm × 2 cm size with a diamond knife. Acid-resistant Teflon tape was used to stick half of the ITO glass, following which the ITO glass was soaked in a solvent with hydrochloric acid. The other half of the ITO at a temperature ranging from 50 to 80 °C, followed which it was clean with DI water. The acid-resistant Teflon tape. was removed and was soaked the ITO substrate in DI water, acetone, and isopropyl alcohol (IPA); treated in an ultrasonic oscillator (DC300, DELTA, ULTRASONIC Co., Ltd., New Taipei City, Taiwan) for 30 min; and then placed it in an oven to dry. The surface resistance and work function of the ITO glass were about 44 Ω/sqand 4.6 eV, respectively.

2.2. Fabrication of Hole Transport Layer

The baked ITO glass was placed in a clean glass container. After being treatment in the UV ozone for about 15 min, it was placed in a spin coater and coated with a hole transport layer (PEDOT:PSS or V2Ox) at different speeds. After all coating is completed, the specimen was placed on a hot plate and annealed at different temperatures for 10 min. The thickness of the resulting hole transport layer was about 50 nm.

For the first reference device (PEDOT:PSS solar cell), the hole transport layer in this experiment was based on PEDOT:PSS. Spin coating was conducted at 4000 rpm, followed by backing in the air at a heating plate temperature of 100 °C for 10 min, and in this way, a polymer solar cell was obtained as a reference.

For the second device (V2Ox solar cell), the rotation speeds and hot-plate temperatures used to obtain the V2Ox layers were studied. After mixing V2Ox and anhydrous isopropanol (IPA) at a volume percentage of 1:40, they were then spin-coated at 2500, 3000, 3500, and 4000 rpm for 30 s, then annealed in the air at a hot plate temperature of 120, 140, and 160 °C. Then, the changes in the characteristics of the resulting polymer solar cell were assessed. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis showed that the formed vanadium oxide film here was mainly composed of V2O5, with a small amount of VO2., similar to results previously reported in the literature for solution-processed vanadium oxide films [27].

For the third device (V2Ox:Au-NPs solar cell), V2Ox and IPA were mixed at a volume percentage of 1:40. Then, gold nanoparticles were added and mixed at a volume percentage of 1:1 or 2:1. The sources of Au-NPs were in two forms: Au-NPs in aqueous solution or PEG (polyethylene glycol)-coated Au-NPs both purchases from Nanocs Inc. (New York, NY, USA). These nanoparticles have a very narrow particle size distribution and in this study, three sizes of gold nanoparticles (with average sizes of 20 nm, 50 nm, and 80 nm, respectively) were used.

Spin-coating at a of 3500, 4000, or 4500 rpm was carried out for 30 s, followed by anneal in the air at a hot plate temperature of 100, 140, or 180 °C. Finally, polymer solar cells were obtained to assess their characteristics.

2.3. Fabrication of Active Layer

After the hole transport layer had been completed, the active layer was then fabricated. To deposit the photoactive layer, P3HT and PCBM were dissolved in 1,2-dichlorobenzene (DCB). The studied devices were put into a glove box and coated with P3HT:PCBM at 800 rpm for 30 s. After they completely dried, they were placed on a hot plate and annealed at 130 °C for 10 min. The active lyyer thickness was about 200 ± 10 nm.

2.4. Fabrication of Electron Transport Layer and Cathode

After the active layer had been completed, the electron transport layer was fabricated. Calcium powder was placed on the evaporator after the annealed specimen had cooled. The chamber was closed and evacuated until the pressure reached 10−6 torr. Then, the calcium powder was evaporated at a rate of 0.5 Å/s to a thickness of 20 nm. Finally, the electrode was made: the electrode metal and calcium powder were placed in the evaporator together, and the aluminum ingot was evaporated at a rate of 2 Å/s to a thickness of 100 nm, thus forming the electrode.

2.5. Measurements

The UV–vis absorption spectrum was recorded using a UV–vis–NIR spectrophotometer (UV-670/FP-6600) (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). The current–voltage curves of the devices were measured using a Keithley 2400 Source Measure Unit. The illumination intensity was 1 sun (100 mW/cm2). The photocurrent was received under illumination from an Oriel 150 W Xenon Lamp 6255 solar simulator with Newport Supply 69907. The above-mentioned equipment was purchased from Forter Tech. (Taichung, Taiwan). The surface morphology on the surface was measured by an atomic force microscope (AFM) system (P47, NT-MDT, Moscow, Russa).

3. Results

3.1. Using PEDOT:PSS as the Hole Transport Layer

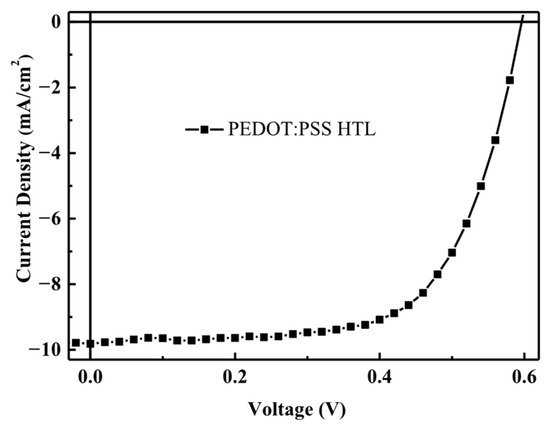

First, we consider solar cell with a standard device structure (Glass/ITO/PEDOT:PSS/P3HT:PCBM/Ca/Al), as shown in Figure 1. After the hole transport layer and the active layer coatings had been added, they were annealed once. The annealing results of the standard devices can be observed. For coating with PEDOT:PSS as the hole transport layer, Spin-coating at 3500 rpm was performed for 30 s. After irradiation with a simulated light source (AM1.5 G) at an intensity of 100 mW/cm2, the short-circuit current density (JSC) is 9.82 mA/cm2, the open-circuit voltage (VOC) was 0.60 V, the fill factor (FF) was 0.64, and the power conversion efficiency (PCE) was 3.80%, which were the optimal parameters (as shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

J–V characteristic curves of polymer solar cell fabricated with PEDOT:PSS as hole transport layer.

3.2. Using V2Ox as the Hole Transport Layer

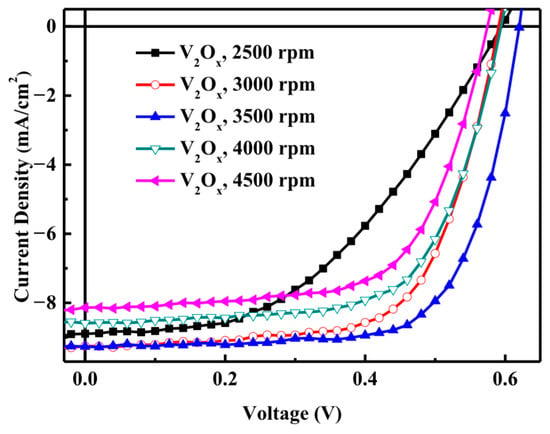

Next, we assesses the V2Ox device structure obtained when adjusting the spin-coating rotation speed as the speed determines the thickness of the material [28]. Figure 3 shows the J–V characteristics of polymer solar cells with a V2Ox hole transport layers fabricated at different rotation speeds. When the rotation speed was too low, the V2Ox was found to be too thick. After the active layer was illuminated, the separated holes could not be easily conducted to the anode.

Figure 3.

J–V characteristics of polymer solar cells with V2Ox hole transport layer fabricated at different the rotation speeds.

As shown in Table 1, when the rotation speed increased from 2500 to 3500 rpm, JSC also increased, and VOC and FF great increased. However, when the speed further increased from 3500 to 4500 rpm, it was found that the current value increased, and the VOCS and FFs values also became smaller. Thus compared with the other rotation speeds, the optimal JSC (9.26 mA/cm2), VOC (0.62 V), FF (0.70), and PCE (4.00%) values can be obtained when the speed is 3500 rpm.

Table 1.

Comparison of the properties of polymer solar cells with V2Ox hole transport layers fabricated at different rotation speeds.

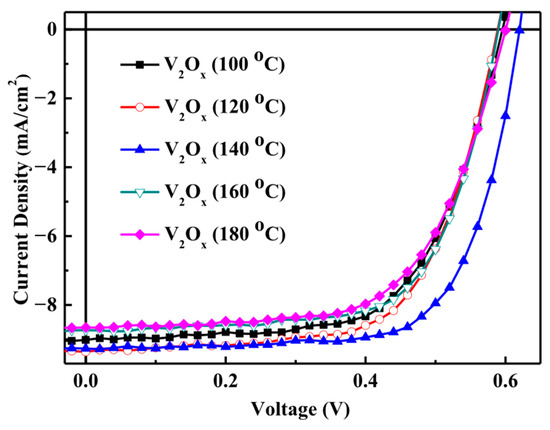

After the optimal rotation speed test, the device coated with a hole transport layer at the optimal rotation speed were annealed at different temperatures for 10 min in a glove box. Figure 4 shows the J–V characteristics of the V2Ox polymer solar cells annealed at different temperatures, these experimental results tabulated in Table 2. It can be seen that, when the annealing temperature increased from 100 to 140 °C, the short-circuit current density increased; however, when the annealing temperature further increased from 140 to 180 °C, JSC decreased

Figure 4.

J–V characteristics of V2Ox polymer solar cells at the annealing temperature of.

Table 2.

Comparison of the properties of polymer solar cells annealed made from V2Ox (without Au-NP) annealed at different temperatures.

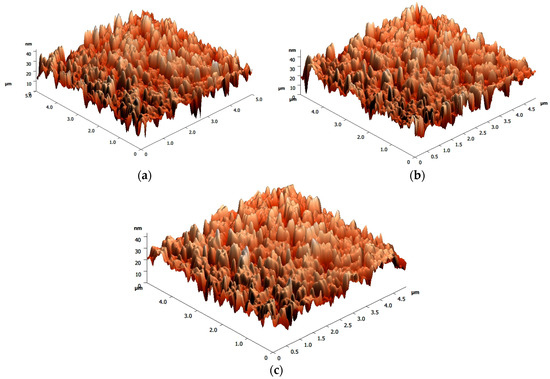

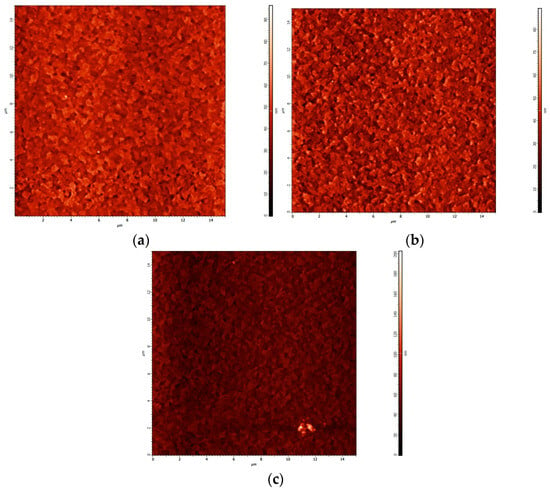

Figure 5 shows the AFM images of V2Ox annealed at different temperatures (i.e., 100, 140, and 180 °C). It can be clearly seen that when the annealing temperature increased from 100 to 140 °C, the root-means-square (rms) roughness of the surface increased from 5.17 nm to 5.75 nm, effectively decreasing the distance of hole transmission. Therefore, the electron hole recombination rate can be reduced and the photocurrent can be increased, thus improving the efficiency [29]. However, when the annealing temperature decreased from 140 °C to 180 °C, due to the increase in annealing temperature, the rms roughness decreases from 5.75 nm to 5.12 nm (as shown in Figure 5), thus decreasing JSC.

Figure 5.

AFM images of V2Ox after annealing at (a) 100 °C, (b) 140 °C, and (c) 180 °C.

3.3. Using V2Ox:Au-NPs as the Hole Transport Layer

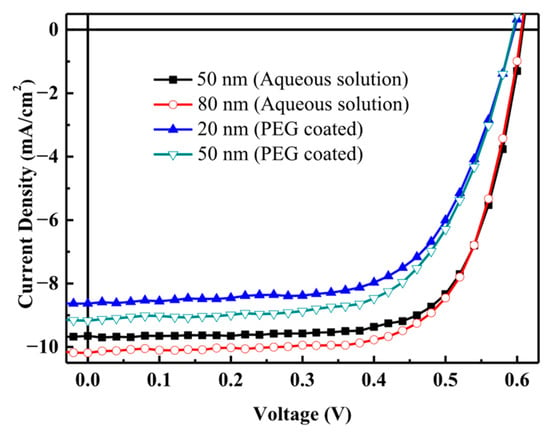

To study the effects of incorporating Au-NPs into V2Ox, V2Ox and Au-NPs of different sizes and sources were mixed in a 1:1 volume ratio. After shaking evenly using an oscillator, they were then applied to the cleaned ITO glass substrate via spin coating, then developed into solar cell materials. Figure 6 depicts the J–V characteristics of solar cells obtained by mixing V2Ox with Au-NPs of different sizes and sources, and Table 3 lists the relevant parameters. Compared with solar cells made with PEG-coated Au-NPs, those made with aqueous Au-NPs exhibited higher VOC, FF, and PCE values. The solar cells made with an aqueous solution of 80 nm Au-NPs exhibited the highest PCE.

Figure 6.

J–V characteristics of polymer solar cells made from V2Ox mixed with Au-NPs. Different curves represent Au-NPs of different sizes and preparation methods.

Table 3.

Comparison of the properties of solar cells made from V2Ox mixed with Au-NPs of different average sizes and sources.

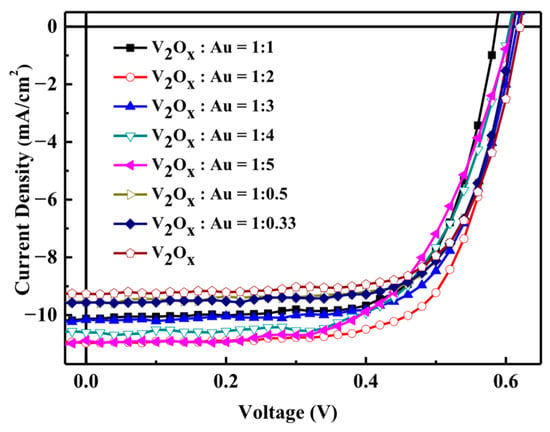

After determining the optimal Au-NP size for V2Ox, the next step was to adjust the ratio of V2Ox to Au-NPs, which directly affects the number of Au-NPs; furthermore, more Au-NPs means less V2Ox in the hole transport layer, resulting in a more transparent structure.

V2Ox:Au-NPs (aqueous solution) were mixed at volume ratios of 1:0, 1:0.33, 1:05, 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 1:4, and 1:5. After being shaken evenly, the mixtures were was spin-coated onto cleaned ITO glass substrate as the material for incorporation into the hole transport layer. Figure 7 shows the J–V characteristics of the solar cells made from V2O5 with 80 nm Au-NPs aqueous solutions at various volume ratios. Table 4 lists a comparison of the characteristics of polymer solar cells made with different V2Ox:Au-NPs ratios. The solar cell fabricated with a pure V2Ox hole transport layer exhibited a JSC of 9.26 mA/cm2, while adding Au-NPs significantly increased the JSC. A V2Ox:Au-NPs volume ratio of 1:2 resulted in the highest JSC, and PCE values.

Figure 7.

Characteristic curves of polymer solar cells made using V2Ox and 80 nm Au-NP aqueous solution mixtures with different volume ratios.

Table 4.

Comparison of the characteristics of V2Ox polymer solar cells without Au-NPs and with different proportions of Au-NPs.

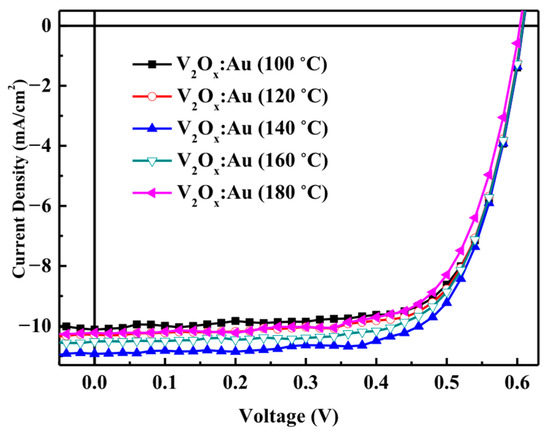

Figure 8 shows the J–V characteristics of polymer solar cells made of V2Ox mixed with Au-NPs and annealed at different temperatures. The V2Ox and Au-NPs were mixed at the optimal volume ratio of 1:2 and shaken uniformly. The resulting mixture was then spin-coated onto a cleaned ITO glass substrate and annealed in a glove box at temperatures of 100, 120, 140, 160, or 180 °C for 10 min. Solar cells were then fabricated and their properties were compared.

Figure 8.

J–V characteristics of polymer solar cells made with V2Ox mixed with Au-NPs and annealed at different temperatures.

The properties of the solar cell including V2Ox mixed with Au-NPs and annealed at different temperatures are listed in Table 5, from which it can be seen that the only significant change was in the JSC value. In particular, increasing the annealing temperature from 100 to 140 °C resulted in a gradual increase in JSC, while a further increase increasing from 140 to 180 °C insulted in a decrease in the current. The VOC and FF values remained relatively stable with increasing temperature.

Table 5.

Comparison of properties of polymer solar cells made of V2Ox mixed with Au-NPs and annealed at different temperatures.

Figure 9a, Figure 9b and Figure 9c show AFM images of the V2Ox film incorporating Au-NPs after annealing at 100, 140, and 180 °C, respectively. The AFM measurements clearly show that the rms roughness increased from 7.04 to 8.58 nm when the temperature increased from 100 to 140 °C. This is significantly rougher than the V2Ox without Au-NPs. As mentioned above, this increased roughness effectively shortens the distance that holes travel, reducing the electron-hole recombination rate and increasing the photocurrent, thereby improving efficiency. However, when the temperatures further increased from 140 to 180 °C, it was found that the increased annealing temperature causes the Au-NPs to gain energy and agglomerate, resulting in a decrease in the JSC.

Figure 9.

AFM images of V2Ox:Au-NP after annealing at (a) 100 °C, (b) 140 °C, and (c) 180 °C.

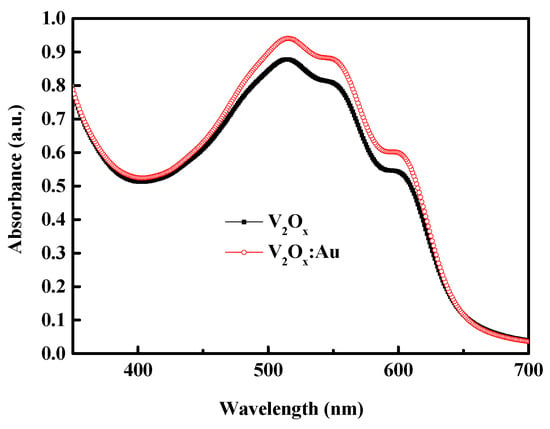

Table 6 compares the characteristics of V2Ox polymer solar cells with and without Au-NPs, where the same rotational speed (3500 rpm) and annealing temperature (140 °C) were used for layer development. The short-circuit current increased from 9.26 to 10.92 mA/cm2. To investigate the properties of V2Ox thin films incorporating Au-NPs, the prepared solution was coated onto an ITO glass substrate for UV–vis absorption spectroscopy measurements; in particular, the structure was ITO/V2Ox:Au-NPs/P3HT:PCBM. Figure 10 shows the absorbance spectra of the P3HT:PCBM blended film with pristine V2Ox and with Au-NPs incorporated into the V2Ox. The UV–vis absorption spectra clearly shows that incorporating Au-NPs enhances the absorption intensity of the P3HT:PCBM blended film.

Table 6.

Comparison of solar cell characteristics with and without Au-NPs in the V2Ox hole transport layer.

Figure 10.

Absorbance spectra of P3HT:PCBM blended film with different hole transport layers; namely V2Ox and V2Ox:Au.

When a light source is incident on an ITO glass substrate with an ITO/V2Ox:Au-NPs/P3HT:PCBM structure, two possible mechanisms can affect the absorption efficiency of the active layer [11] the light scattering effect and the light LSPR effect. Generally speaking, the scattering efficiency of Au-NPs only exceeds their absorption efficiency when the particle size is greater than 100 nm. As the average size of Au-NPs was less than 100 nm in our experiment. It can be considered that the absorption efficiency was primarily driven by the LSPR effect; namely the LSPR effect induced by the addition of the considered Au-NPs enhances light collection in the active region.

Our experiments show that the addition of Au-NPs to V2Ox increases absorption between 500 and 600 nm, leading to an increase in the JSC. There may be a little mismatch between optical absorption and electrical output, possibly due to increased recombination or parasitic absorption. The VOC remains unchanged, while the FF value increases slightly. Overall, the PCE increased from 4.00% to 4.65%.

4. Conclusions

Polymer solar cells using V2Ox as the hole transport layer were successfully fabricated. The PCE values of polymer solar cells using PEDOT:PSS and V2Ox as hole transport layers were 3.80% and 4.00%, respectively. When 80 nm gold nanoparticles were incorporated into V2Ox, the PCE further improved to 4.65%. This was attributed to the gold nanoparticles increasing the surface roughness of the V2Ox and inducing the LSPR effect. The results of this study demonstrate the great potential of our proposed V2Ox:NPs for the development of improved hole transport layer materials.

Author Contributions

Investigation, Y.-S.L.; Data curation, S.-M.S.; Writing—original draft, Y.-S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science and Technology Council, grant number NSTC 113-2221-E-259-006.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Priya, P.; Stonier, A.A. Emerging innovations in solar photovoltaic (PV) technologies: The perovskite solar cells and more. Energy Rep. 2025, 14, 216–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.S.; Chen, W.H. Dye-sensitized solar cells with modified TiO2 scattering layer produced by hydrothermal method. Materials 2025, 18, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Zhu, Y.F.; Ye, L.; Miao, C.Y.; Lin, Y.Z.; Zhang, S.M. Nonfullerene all-small-molecule organic solar cells: Prospect and Limitation. Sol. RRL 2020, 4, 2000258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Kim, Y.; Na, Y.H.; Baek, N.S.; Jung, J.W.; Choi, Y.; Cho, N.; Kim, T.D. Efficient inverted solar cells using benzotriazole-based small molecule and polymers. Polymers 2021, 13, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.N.; Zhang, J.Q.; Tian, C.Y.; Shen, Y.F.; Wang, T.; Zhang, H.; He, C.; Qiu, D.D.; Shi, Y.N.; Wei, Z.X. Efficient large area all-small-molecule organic solar cells fabricated by slot-die coating with nonhalogen solvent. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2300778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Ma, R.J.; Dela Pena, T.A.; Yan, C.Q.; Li, H.X.; Li, M.J.; Wu, J.Y.; Cheng, P.; Zhong, C.; Wei, Z.H.; et al. Efficient all-small-molecule organic solar cells processed with non-halogen solvent. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.M.; Wang, C.X.; Deng, D.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.L.; Zhang, J.Q.; Yang, Y.P.; Wei, Z.X. Small molecule donors design rules for non-halogen solvent fabricated organic solar cells. Small 2024, 20, 2309042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balawi, A.H.; Kan, Z.P.; Gorenflot, J.; Guarracino, P.; Chaturvedi, N.; Privitera, A.; Liu, S.J.; Gao, Y.J.; Franco, L.; Beaujuge, P.; et al. Quantification of photophysical processes in all-polymer bulk heterojunction solar cells. Sol. RRL 2020, 4, 2000181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.E.; Cho, S.H.; Lee, S.M. Embedded plasmonic nanoprisms in polymer solar cells: Band-edge resonance for photocurrent enhancement. APL Mater. 2020, 8, 041116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.Y.A.; Mola, G.T. Nanocore shells for effective collection of photocurrent in polymer solar cell. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2025, 2500215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.L.; Chen, F.C.; Hsiao, Y.S.; Chien, F.C.; Chen, P.L.; Kuo, C.H.; Huang, M.H.; Hsu, C.S. Surface plasmonic effects of metallic nanoparticles on the performance of polymer bulk heterojunction. solar cells. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Gao, J.; Hummelen, J.C.; Wudl, F.; Heeger, A.J. Polymer photovoltaic cells: Enhanced efficiencies via a network of internal donor-acceptor heterojunctions. Science 1995, 270, 1789–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosekar, I.C.; Patil, G.C. Review on performance analysis of P3HT:PCBM-based bulk heterojunction organic solar cells. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2021, 36, 045005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Petoukhoff, C.E.; Jurado, J.P.; Aldosari, H.; Jiang, X.Y.; Váry, T.; Al Nasser, H.; Dahman, A.; Althobaiti, W.; Lopez, S.P.G.; et al. Influence of thermal annealing on microstructure, energetic landscape and device performance of P3HT:PCBM-based organic solar cells. J. Phys. Energy 2024, 6, 025013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terán-Escobar, G.; Pampel, J.; Caicedo, J.M.; Lira-Cantú, M. Low-temperature, solution-processed, layered V2O5 hydrate as the hole-transport layer for stable organic solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 3088–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.C.; Zhu, Q.Q.; Wang, T.; Guo, J.; Yang, C.P.; Yu, D.H.; Wang, N.; Chen, W.C.; Yang, R.Q. Simple O2 Plasma-processed V2O5 as an anode buffer layer for high-performance polymer solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 7613–7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.; Yun, J.Y.; Kim, D.H. Highly stable inverted organic photovoltaic cells with a V2O5 hole transport layer. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 34, 1504–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.B.; Zhang, R.; Ye, X.Q.; Wen, Z.Y.; Xia, J.B.; Lu, X. In-situ synthesis of organic-inorganic hybrid thin film of PEDOT/V2O5 as hole transport layer for polymer solar cells. Sol. Energy 2019, 190, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.F.; Qin, J.C.; Liu, X.P.; Ren, M.L.; Tong, J.F.; Zheng, N.; Chen, W.C.; Xia, Y.J. Enhanced organic photovoltaic performance through promoting crystallinity of photoactive layer and conductivity of hole-transporting layer by V2O5 doped PEDOT:PSS hole-transporting layers. Sol. Energy 2020, 211, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkarsifi, R.; Ackermann, J.; Margeat, O. Hole transport layers in organic solar cells: A review. J. Met. Mater. Min. 2022, 32, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anrango-Camacho, C.; Pavón-Ipiales, K.; Frontana-Uribe, B.A.; Palma-Cando, A. Recent advances in hole-transporting layers for organic solar cells. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniruzzaman, M.; Abdur, R.; Sheikh, M.A.K.; Singh, S.; Lee, J.G. Conductive MoO3–PEDOT:PSS composite layer in MoO3/Au/MoO3–PEDOT:PSS multilayer electrode in ITO-Free organic solar cells. Processes 2023, 11, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Xu, B.W.; Ye, F.F. Recent advance in solution-processed hole transporting materials for organic solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2310865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarianni, M.; Vernon, K.; Chou, A.; Aljada, M.; Liu, J.Z.; Motta, N. Plasmonic effect of gold nanoparticles in organic solar cells. Sol. Energy 2014, 106, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, D.A.; Ali, A.M.; Khayyat, M.M.; Boustimi, M.; Loulou, M.; Seoudi, R. A study of the influence of plasmonic resonance of gold nanoparticle doped PEDOT: PSS on the performance of organic solar cells based on CuPc/C60. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phengdaam, A.; Phetsang, S.; Jonai, S.; Shinbo, K.; Kato, K.; Baba, A. Gold nanostructures/quantum dots for the enhanced efficiency of organic solar cells. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 3494–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancox, I.; Rochford, L.A.; Clare, D.; Walker, M.; Mudd, J.J.; Sullivan, P.; Schumann, S.; McConville, C.F.; Jones, T.S. Optimization of a high work function solution processed vanadium oxide hole-extracting layer for small molecule and polymer organic photovoltaic cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashtoush, N.M.; Sheiab, A.; Jafar, M.; Momani, S. Determining optical constants of sol-gel vanadium pentoxide thin films using transmittance and reflectance spectra. Int. J. Phys. Stud. Res. 2019, 2, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shrotriya, V.; Huang, J.S.; Yao, Y.; Moriarty, T.; Emery, K.; Yang, Y. High-efficiency solution processable polymer photovoltaic cells by self-organization of polymer blends. Nat. Mater. 2005, 4, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).