Abstract

Understanding the deformation–failure process of sandstone is essential for energy extraction and stability assessment. Here, laboratory mechanical tests and discrete element simulations are combined to resolve how grain size controls deformation, cracking, and failure. Under uniaxial compression, fine-grained sandstone shows the highest strength (60.85–65.37 MPa) yet undergoes an abrupt brittle transition to axial splitting at a small peak axial strain of 0.41–0.42%; coarse-grained sandstone exhibits lower strength (26.94–28.67 MPa) but fails at peak axial strains of 0.44–0.53%, on average about 17% higher than those of FGS, indicating enhanced ductility; medium-grained sandstone lies in between in both strength (41.15–43.79 MPa) and peak axial strain (0.42–0.45%). With confining pressure, fine- and medium-grained sandstones display pronounced process evolution toward ductility, whereas coarse-grained sandstone shows limited pressure sensitivity. DEM results link microcrack evolution with the macroscopic response: under uniaxial loading, fine-grained sandstone is dominated by intergranular tensile cracking, while coarse-grained sandstone includes more intragranular cracks. Increasing confinement controls the cracking process, shifting fine- and medium-grained rocks from intergranular tension to mixed intragranular tension–shear, thereby enhancing ductility; in contrast, coarse-grained sandstone at high confinement localizes shear bands and remains relatively brittle. Normalized microcrack aperture distributions and fragment identification capture a continuous damage accumulation process from micro to macro scales. These process-based insights clarify the controllability of failure modes via grain size and confinement and offer optimization-oriented guidance for design parameters that mitigate splitting and promote stable deformation in deep sandstone reservoirs and underground excavations.

1. Introduction

Sandstone, one of the most widely distributed sedimentary rocks, is crucial in deep energy exploitation, subsurface reservoir utilization, and the stability assessment of underground engineering structures [1]. Multiple factors, including mineral composition, pore structure, grain arrangement, and grain size, govern the mechanical behavior of rocks. The grain size effect has been recognized as a key factor controlling rocks’ mechanical properties and failure modes [2]. However, compared with porosity and mineralogical composition, the influence of grain size has not yet been systematically understood, which constrains a comprehensive interpretation of sandstone deformation and failure processes.

Early experimental investigations have already highlighted the critical role of grain-scale characteristics in rock mechanical responses. For instance, uniaxial compression tests on granite demonstrated that the nucleation and propagation of microcracks are strongly linked to grain arrangement and grain size [3]. Systematic reviews of microcrack characteristics showed that the crack initiation stress negatively correlates with grain size [4]. Additional studies emphasized the role of grain size in subcritical crack growth, and micromechanical analyses confirmed that rocks with finer grains exhibit higher strength but more pronounced brittleness [5,6]. Subsequent observations revealed that finer grains promote intergranular cracking, whereas coarser grains are more prone to intragranular cracking due to stronger stress concentration effects [7]. These findings provide important experimental evidence for understanding the effects of grain size.

In addition to crystalline rocks, extensive experimental work has examined the micromechanical behavior of cemented and porous sandstones. Micro-CT imaging and in situ deformation tests on weakly to strongly cemented sandstones have shown that the progressive rupture of cement bridges, pore-scale strain localization, and grain rearrangement govern the transition from distributed microcracking to macroscopic failure [8]. Laboratory tests on artificially cemented granular materials also reveal that tensile debonding of cement bridges, followed by limited intragranular fracturing and fragment rearrangement, controls the post-peak softening behavior [9]. These experimental observations collectively highlight that the interplay between grain size, cementation and pore–grain geometry is fundamental to the failure of reservoir sandstones.

Building on these observations, further work explored the regulating influence of confining pressure. It was shown that microcrack development transitions from tensile opening along grain boundaries to shear-dominated localization with increasing confining pressure, resulting in enhanced macroscopic ductility [10,11]. Subsequent triaxial tests confirmed that fine-grained rocks exhibit significant ductility enhancement under confining pressure, while coarse-grained rocks display lower sensitivity to pressure, with only limited ductility gain [12,13]. These results indicate that grain size effects determine the strength and failure mode under uniaxial conditions and govern the ductility evolution under high confinement.

With the advancement of computational methods, the discrete element method [DEM] has become a powerful tool for investigating grain size effects. A classical bonded-particle model [BPM] was proposed to represent rock mechanical behavior through bonded particle networks, allowing for the simulation of crack initiation, propagation, and post-peak responses [14]. This approach has proven particularly effective in capturing microcrack evolution and failure localization. Later developments extended DEM to reproduce acoustic emission signals corresponding to microcrack activity and to incorporate grain interlocking effects, improving the physical realism of simulated fracture processes [15,16].

In recent years, grain-based models (GBMs) that explicitly incorporate mineral grains have been widely applied in rock mechanics studies [17,18,19,20,21]. Due to their capability of representing grain size explicitly, the GBM has become the mainstream approach for analyzing grain size effects in crystalline and polymineralic rocks [22]. Systematic studies have demonstrated that the ratio of grain size to numerical element size significantly influences microcracking behavior: smaller numerical elements can more faithfully reproduce crack evolution but at much higher computational cost [23]. Other investigations showed that fine-grained models generally exhibit higher peak strength, while coarse-grained models tend to fail through shear localization [24]. Moreover, grain size distributions strongly control rock salt’s mechanical and creep behavior [25].

Parallel to these advances, significant progress has also been made in understanding damage mechanics and crack evolution. A classical theoretical framework of brittle damage mechanics was developed to explain how microcrack accumulation leads to macroscopic failure [26]. Further studies revealed that pore–grain interactions strongly influence failure modes under compression [27]. Earlier investigations highlighted the significance of tracking spatiotemporal microcrack evolution for understanding brittle failure processes in heterogeneous rocks [28]. More recently, numerical studies have systematically examined the spatiotemporal evolution of microcracks in laminated shales. At the same time, grain boundary weakening models revealed that fine-grained rocks tend to develop pervasive tensile fractures. In contrast, coarse-grained rocks are more prone to localized shear failure [29,30].

Previous studies demonstrate that both experimental observations and numerical simulations have significantly improved our understanding of grain size-controlled failure in brittle rocks. However, most calibrated grain-based model applications to date have concentrated on crystalline lithologies such as granite and rock salt or on synthetic/idealized rock analogs, and systematic experimental–numerical studies that use GBM calibrated against laboratory tests on natural reservoir sandstones with different grain sizes under confining pressure remain scarce. In this study, we combine triaxial laboratory tests on three sandstones with distinct grain sizes and a calibrated grain-based discrete element model to link macroscopic strength–ductility evolution with grain-scale crack types, crack apertures, and fragment development. This process-based framework provides a novel perspective on why coarse-grained sandstone shows limited ductility enhancement under confinement compared with fine- and medium-grained sandstones, and it offers practical implications for stability assessment and failure-mode control in deep sandstone reservoirs.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the mechanical characterization of sandstones with different grain sizes based on comprehensive laboratory testing, emphasizing the effects of grain size on strength, deformation behavior, and failure patterns. Section 3 employs the discrete element method (DEM) to construct grain-based digital sandstone models and investigate the micromechanical failure behavior of sandstones with different grain sizes, focusing on the correspondence between macroscopic mechanical responses, microcrack evolution, and the spatiotemporal development of failure modes. Section 4 summarizes the main findings and implications of this study.

2. Mechanical Characterization of Sandstones with Different Grain Sizes

2.1. Grain Size Characteristics of the Sandstone Samples

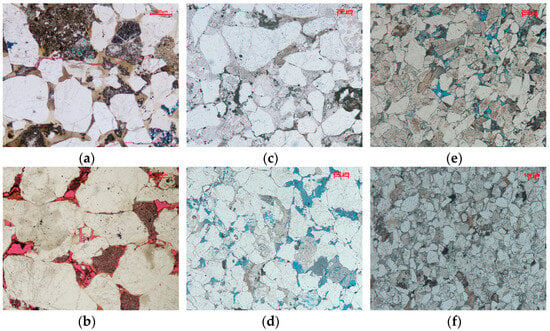

The cored intervals used in this study are mainly located at burial depths of approximately 1600–2400 m, and the sampling wells are distributed across the [central and northern] part of the Ordos Basin. The majority of the tested sandstone samples were obtained from the YC Formation in this basin, with a smaller subset taken from adjacent reservoir intervals. These wells provide basin-scale coverage of the target sandstone reservoir interval rather than a single local cluster. Based on detailed geological descriptions, three representative sandstone types were identified: coarse-grained sandstone (CGS), medium-grained sandstone (MGS), and fine-grained sandstone (FGS). Representative specimens from each category were prepared as thin sections for petrographic analysis under a polarizing microscope. Figure 1 presents the single-polarized light photomicrographs of the three sandstone types. In this study, the grain size classes follow standard sandstone grain size divisions, such that CGS, MGS, and FGS correspond approximately to mean grain sizes larger than 0.5 mm, between 0.25 and 0.5 mm, and less than 0.25 mm, respectively.

Figure 1.

Representative single-polarized light photomicrographs of sandstones from the Ordos Basin: (a) CGS1; (b) CGS2; (c) MGS1; (d) MGS2; (e) FGS1; (f) FGS2.

Microscopic observations reveal that the coarse-grained sandstone contains relatively large mineral grains (>0.5 mm), predominantly sub-angular to sub-rounded quartz and feldspar particles, exhibiting a grain-supported framework. The cement is mainly ferruginous and clay-rich, with localized pore spaces partially infilled by iron oxides. Some feldspar grains display pronounced alteration and cleavage fractures, while lithic fragments are rare. Overall, the sorting is poor (see Figure 1a,b). The medium-grained sandstone exhibits grain sizes in the 0.25–0.5 mm range, composed mainly of sub-rounded quartz, plagioclase, and minor lithic fragments. Sorting is moderate, with intergranular cement dominated by calcite and clay, locally infilling pore spaces. Limited ferruginous cement occurs in concentrated patches, and grain contacts are primarily point–line types. The overall compaction and density are greater than those of the coarse-grained sandstone (see Figure 1c,d). In contrast, the fine-grained sandstone consists of smaller grains (<0.25 mm), characterized by high roundness and good sorting, dominated by quartz with minor feldspar and lithic fragments. The cement is mainly calcitic and clayey, with minor ferruginous components. Porosity is markedly reduced, and the rock exhibits a mixed matrix-grain-supported fabric. Grain contacts are tight, and the overall compaction and density are the highest among the three types (see Figure 1e,f). Bulk X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses were not acquired for these cores; in this study, approximate mineralogical consistency among the three sandstone types is therefore inferred from thin-section petrography, which indicates quartz-dominated framework grains with minor feldspar and lithic fragments, rather than quantitatively demonstrated by bulk modal analysis.

2.2. Size Dependence of Triaxial Strength and Deformation Behavior

Cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 25 mm and a length of 50 mm were prepared from the recovered subsurface cores. For each of the three representative sandstone types, ultrasonic velocity measurements were first conducted to select specimens with relatively uniform elastic properties, thereby minimizing the influence of sample heterogeneity on the mechanical test results. Subsequently, rock mechanical tests were performed on the selected specimens under three confining pressure conditions: uniaxial compression, a fixed confining pressure of 10 MPa, and a confining pressure of approximately 20 MPa corresponding to the estimated in situ stress at the sampling depth.

It should be noted that the three sandstone types were obtained from different wells and stratigraphic intervals. To minimize the potential bias introduced by differences in in situ stress conditions, specimens were selected from intervals with comparable burial depths (typically in the range 2200–2400 m). This selection ensured that the confining pressures corresponding to the in situ stress conditions differed by less than 1 MPa among the three sandstone types. Based on the above specimen selection and loading scheme, rock mechanical tests were carried out on the three sandstone types under uniaxial compression, a confining pressure of 10 MPa, and confining pressures equivalent to the estimated in situ stress conditions. The experiments were conducted using a 600 kN servo-controlled uniaxial/triaxial rock mechanics testing system, with a pressure control accuracy of ±0.01 MPa and a displacement measurement accuracy of ±0.001 mm.

Confining pressure was applied incrementally at a 5 MPa/min rate for the triaxial tests until the target value was reached. Once stabilized, axial displacement was applied at a constant rate of 0.1 mm/min until specimen failure. The same axial displacement rate was applied directly until failure in the uniaxial tests.

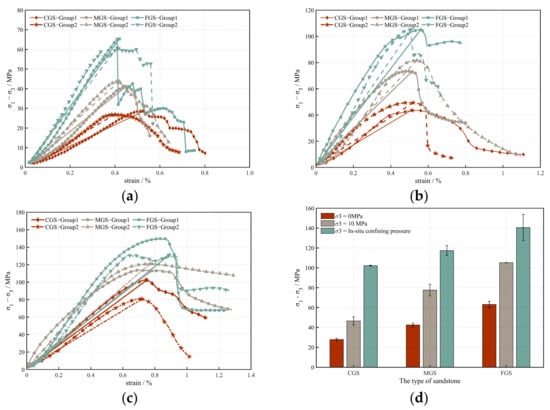

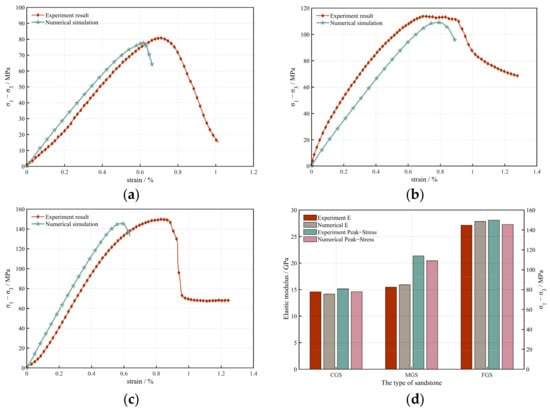

Figure 2 presents the stress–strain responses of the three sandstone types under different confining pressures. Overall, marked differences are observed in peak strength, ductility, and post-peak decay patterns, with each rock type showing a distinct sensitivity to confining pressure. For fine-grained sandstone (FGS), the uniaxial compression (UCS) curves exhibit the highest peak strength and largest elastic modulus among the three types, followed by a rapid stress drop after the peak, indicative of a pronounced brittle failure behavior in a relative sense. Medium-grained sandstone (MGS) under UCS conditions shows a slightly lower post-peak decay rate and a higher residual strength than FGS, suggesting a somewhat greater load-carrying capacity after instability. When the confining pressure increases to 10 MPa, FGS and MGS substantially increase peak strength, causing slower post-peak decay and an extended plastic deformation stage. This indicates that confining pressure effectively delays rapid crack propagation, promoting an enhancement in relative ductility. Under in situ stress conditions, the ductility of both sandstones is further improved, with post-peak curves displaying prolonged descending branches. Such behavior generally implies that the instantaneous formation of a single through-going fracture does not govern failure. Instead, crack propagation is suppressed by confining pressure, with local cement gradually breaking down. At the same time, grains undergo slow relative sliding along contacts or weak cementation planes, accompanied by minor rotations, interlocking, or rearrangements. These progressive structural adjustments help sustain load capacity and retard rapid stress release, producing the smooth post-peak segments characteristic of enhanced ductility.

Figure 2.

Stress-strain curves of the three sandstone types under different confining pressures: (a) uniaxial compression; (b) 10 MPa confining pressure; (c) in situ confining pressure; (d) peak strength and elastic modulus statistics.

In contrast, coarse-grained sandstone (CGS) shows stress–strain features distinctly different from the above two sandstones. Under UCS conditions, CGS records the lowest peak strength but a more gradual post-peak decay, exhibiting a relatively more ductile behavior. This laboratory-scale ductile response is interpreted as being closely related to its large grain size, poor sorting, and heterogeneous cementation: in the laboratory specimens, at low confining pressures, large pores and pre-existing microcracks can gradually close during loading, while rough fracture surfaces hinder shear slip, preventing rapid sliding along failure planes. Consequently, a certain load capacity is maintained after the peak, delaying stress release. At a confining pressure of 10 MPa, CGS exhibits markedly divergent post-peak behavior: in some specimens, the post-peak branch remains relatively flat, retaining ductility, whereas in others, stress drops sharply, indicating a more brittle instability in relative terms. In addition, the serrated features of the CGS stress–strain curves in Figure 2a–c mainly reflect intermittent micro-failure events within the highly heterogeneous coarse-grained fabric. This variability suggests that, at moderate confining pressures, the failure mechanism of CGS is strongly influenced by the distribution of local structural defects, leading to an inconsistent ductility enhancement. Under in situ stress conditions, CGS generally shows a faster post-peak decay and reduced ductility, with a tendency toward relative brittleness. This can be attributed to the near-complete closure of pores and microcracks early in loading, eliminating the buffering effect observed at low confining pressures. Moreover, the coarse-grain framework, once cement bonds are broken, cannot readily develop new stable load-bearing structures through fine-scale grain sliding and rearrangement as in FGS and MGS; instead, it is more prone to large-scale block displacement or localized pulverization, concentrating strain energy release within a short interval.

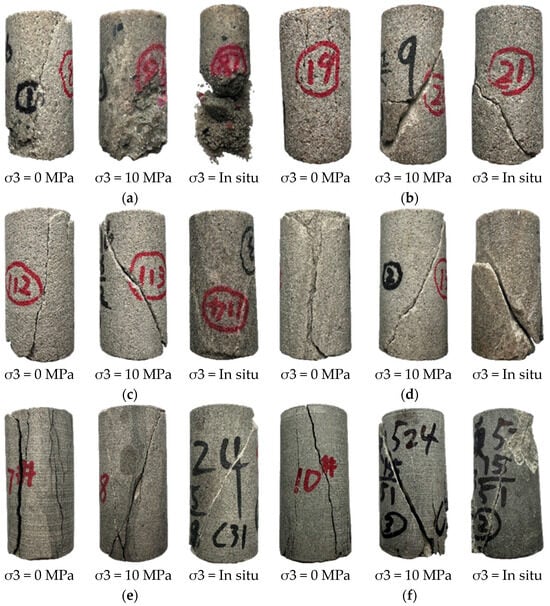

Figure 3 shows the post-test failure morphologies, which closely correspond to the observed stress–strain features. Under UCS conditions, FGS typically fails through straight axial splitting with concentrated, parallel cracks, occasionally accompanied by secondary fractures. MGS also fails mainly by splitting, but with a greater number of cracks and more frequent branching. CGS, in contrast, develops one or more irregular splitting bands with dispersed crack distribution, accompanied by extensive grain detachment and local disintegration; the rough fracture surfaces match its gradual post-peak decay and higher residual strength.

Figure 3.

Post-test failure morphologies of the three sandstone types under different confining pressures: (a) CGS-Group1; (b) CGS-Group2; (c) MGS-Group1; (d) MGS-Group2; (e) FGS-Group1; (f) FGS-Group2.

At 10 MPa confining pressure, the failure mode of FGS and MGS shifts from pure splitting to inclined shear banding, with highly concentrated and more through-going cracks, consistent with the observed increase in ductility. CGS again shows two distinct patterns: in some specimens, no clear main shear plane develops, and failure proceeds mainly by progressive grain detachment, leading to a slow post-peak stress drop; in others, a single shear band forms near the specimen’s mid-height, accompanied by block fragmentation, causing a rapid post-peak stress decline. These contrasting patterns reaffirm that, at moderate confining pressure, CGS failure is strongly dependent on local grain arrangements and cementation heterogeneity.

Under in situ stress conditions, FGS and MGS form highly continuous main shear bands accompanied by a number of secondary cracks. Failure is concentrated, with pronounced shear features, while post-peak ductility remains high. CGS, however, exhibits two typical failure manifestations: in some specimens, one end undergoes severe pulverization, resulting in abrupt post-peak stress loss; in others, the main shear band displays distinct curvature, with its path circumventing harder grains or more strongly cemented zones, leading to a rapid stress drop followed by a brief, less steep decline. These observations confirm that CGS, unlike FGS and MGS, lacks the capacity for progressive grain sliding and rearrangement under high confining pressure. Consequently, the confining pressure effect is limited. CGS is more prone to localized failure and rapid energy release, making it difficult for ductility to continue increasing and sometimes causing a reversion toward relative brittleness.

In summary, FGS and MGS display a consistent and monotonic enhancement in ductility with increasing confining pressure, with their failure mode transitioning steadily from splitting to shear banding, and the confining pressure effect being highly uniform among specimens. In contrast, CGS shows a non-monotonic ductility–confining pressure relationship, with failure modes heavily controlled by local structural defects. CGS may exhibit ductile, brittle, or mixed responses depending on the confining pressure and structural configuration. The underlying cause lies in the combined influence of grain size, sorting, cementation characteristics, and pore–microcrack structure on crack initiation, propagation, and instability: the dense, uniformly cemented structures of FGS and MGS favor progressive failure under confining pressure, while the coarse grains, heterogeneous cementation, and complex void structures of CGS make its response more dependent on local structural conditions and more susceptible to abrupt brittle failure at high confinement.

These trends are broadly consistent with previous experimental observations on grain size–controlled strength and failure in crystalline rocks and sandstones. Earlier studies reported that decreasing grain size generally increases peak strength and promotes more pronounced brittle splitting under uniaxial conditions, whereas coarser grains favor earlier shear localization and show a more limited ductility enhancement under confining pressure [8,9,10,11]. Our triaxial data on reservoir sandstones from the Ordos Basin confirm this general grain size dependence, but also extend it by showing that coarse-grained sandstone can even exhibit a reversion toward relatively brittle behavior at near in situ confining pressures. This behavior reflects the strong heterogeneity of the coarse-grained fabric and suggests that coarse-grained reservoir sandstones may remain susceptible to abrupt failure even under elevated confining pressure. For the coarse-grained sandstone, the 25 mm specimen diameter spans only a few tens of grain diameters, so the tested volumes are sensitive to local variations in packing and cementation. The two distinct failure patterns observed for CGS at 10 MPa are therefore interpreted as expressions of this limited specimen size relative to grain size rather than evidence for multiple intrinsic failure modes. Consequently, the CGS results at 10 MPa should be regarded as qualitatively illustrative and not strictly representative of reservoir-scale behaviors.

3. Micromechanical Failure Behavior of Sandstones with Different Grain Sizes

3.1. Construction and Validation of Digital Rock Models

To gain deeper insight into the failure mechanisms of sandstones with different grain sizes at the microscale, experimental observations alone are insufficient to fully capture the complex interactions among grains and the evolution of cracks. Therefore, building upon the experimental results, this study introduces the discrete element method (DEM) to construct grain-based digital sandstone models. These models allow the micromechanical responses at the grain scale to be simulated under controlled conditions, complementing the laboratory tests and providing grain-scale micromechanical information under controlled loading conditions that complements the laboratory observations.

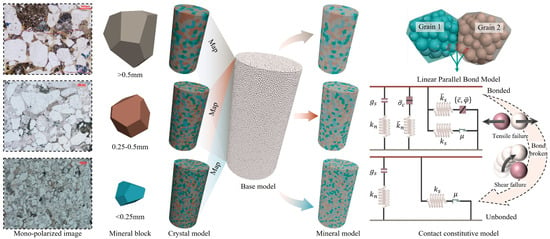

Figure 4 illustrates the workflow for constructing GBM-based digital sandstones with different grain sizes. The modeling procedure begins with the extraction of representative grain size ranges for coarse-grained sandstone (CGS), medium-grained sandstone (MGS), and fine-grained sandstone (FGS), based on the thin-section observations described earlier. Using the Voronoi tessellation technique, a crystal model is generated to reproduce the characteristic grainsize distributions of each sandstone type. On this basis, mineralogical heterogeneity is incorporated by assigning mineral phases to individual grains through a spatial mapping scheme constrained by petrographic estimates of modal fractions from thin-section observations. In this way, three types of GBM-based digital sandstone models are established; the essential distinction lies in the characteristic grain size, thereby enabling explicit investigation of grainsize effects on the overall mechanical response.

Figure 4.

Workflow for constructing GBM-based digital sandstone models of different grain sizes.

In the numerical simulations, each sandstone type was represented by a cylindrical specimen with the same diameter and height as the laboratory samples described in Section 2.2, so that the numerical boundary conditions and stress paths are directly comparable to the physical tests. The model domain was discretized into polygonal grains by a grain-based tessellation. For the CGS, MGS and FGS models, the target mean grain sizes were chosen to be consistent with the petrographic classification in Section 2.1, such that the numerical grains fall predominantly into the coarse-, medium- and fine-grained ranges, respectively. Grain-scale mechanical interactions were represented by a linear bonded-contact law between adjacent grains.

The treatment of grain–grain bonding follows the approach of Peng et al. [23] in which the contact parameters across grain boundaries are deliberately weakened to represent the relatively fragile nature of mineral intergranular cementation. It should be noted that pores are not geometrically represented in the GBM; instead, pore-related effects are incorporated in a homogenized manner by adjusting the contact parameters and grain packing, so that the synthetic models exhibit an overall degree of mechanical heterogeneity comparable to that of the natural sandstones while capturing only the effective influence of porosity on bulk stiffness and strength, not the explicit geometry or collapse of individual pores. The linear parallel bond model (PBM), widely adopted in discrete element modeling, describes intra-grain and inter-grain interactions. This model allows the simultaneous representation of normal and shear responses at grain contacts. Bond breakage is triggered once the stress exceeds the bond strength threshold, corresponding to tensile or shear failure. The use of PBM thus provides a robust framework to simulate the progressive failure of sandstones at the grain scale and to capture the transition from distributed microcracking to macroscopic fracture.

Accurate input parameters are essential to ensure the reliability of discrete element simulations. In this study, parameter assignment was carried out by integrating experimental data with published results, followed by iterative calibration and validation through comparison with laboratory tests.

For the mechanical properties of mineral grains, nanoindentation measurements reported in previous studies were adopted to assign elastic and strength parameters to individual mineral phases, ensuring a realistic representation of their intrinsic behavior [31,32]. The assignment of grain-boundary parameters was then developed on this basis. We analyzed the dataset Tang et al. [33]. reported, which provides intragranular and intergranular strength measurements on granite. A physically informed relationship was established through comparative analysis linking intergranular strength to the properties of the contacting mineral grains. This relationship, formulated according to Wang et al. [34] (Equation (1)), was implemented in the numerical model to provide a consistent and mechanistically grounded representation of mineral grain boundaries.

where x is a parameter in the LPBM; x′ is the intergranular coefficient; n1 and n2 represent the number of contacts at the ends of particles A and B, respectively; and represent the sum of the values of parameter x in the contacts of particles A and B, respectively.

We adopted the empirical grain size-dependent weakening approach of Peng et al., in which the intergranular bond parameters are scaled according to Equation (1) to represent the observed reduction in effective bonding strength with increasing grain size [7]. These coefficients effectively modulate the strength of grain-to-grain bonds and thus reproduce the distinct cementation characteristics of coarse-, medium-, and fine-grained sandstones.

Figure 5 compares the experimental and simulated stress–strain curves of the three sandstone types under in situ confining pressures. Figure 5a presents the calibration result, in which the micro-parameters of the grain-based DEM were iteratively adjusted to match the laboratory stress–strain curve of the reference sandstone. The calibrated model successfully reproduces the elastic modulus and peak strength of the reference sandstone, with relative errors below 5% for these key mechanical parameters, and provides a reasonable match to the initial yield behavior. Figure 5b,c then apply the same calibrated micro-parameters to the medium- and coarse-grained models, with only the grain size-related weakening coefficients adjusted to account for the inherent reduction in intergranular bonding associated with increasing grain size. Under this unified parameter framework, the simulated mechanical responses of the three grain size classes reproduce the main features of the corresponding laboratory curves, particularly the pre-peak stiffness and peak strength, although the post-peak softening of CGS is captured in a more gradual manner than observed experimentally. This two-step strategy—calibrating the base micro-parameters using a representative sample (Figure 5a), and subsequently applying grain size-dependent weakening to reproduce the behavior of other sandstones (Figure 5b,c)—demonstrates that the adopted parameterization can reliably differentiate grain size-controlled deformation and failure. In this context, the different interphase values listed in Table 1 for MGS and CGS are not independently tuned parameter sets, but are obtained by applying the grain size-dependent weakening coefficients to the same calibrated base micro-parameters used for the reference sandstone. The robustness of the numerical model provides a solid foundation for the micromechanical analyses presented in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3. The complete set of input micro-parameters is summarized in Table 1.

Figure 5.

Experimental and simulated stress−strain curves of sandstones with different grain sizes under in situ confining pressure: (a) uniaxial compression; (b) 10 MPa confining pressure; (c) in situ confining pressure; (d) peak strength and elastic modulus statistics.

Table 1.

Mesoscopic parameters for digital rock.

3.2. Mechanical Responses and Microcrack Evolution in Sandstones with Different Grain Sizes

On the basis of the previously constructed and calibrated digital rock models, the discrete element method was applied to simulate the mechanical response of the three sandstone types under varying confining pressures, with particular focus on the evolution of microcracks during loading. Simulations were carried out under three representative conditions: uniaxial compression (0 MPa), 10 MPa, and 20 MPa, consistent with the laboratory testing program. To isolate the role of grain size, all models were assigned identical mineralogical compositions, while particle size was varied to represent coarse-, medium-, and fine-grained sandstones. Differences in cementation strength among sandstone types were further captured by applying weakening factors to the intergranular contacts, following the parameterization scheme described earlier.

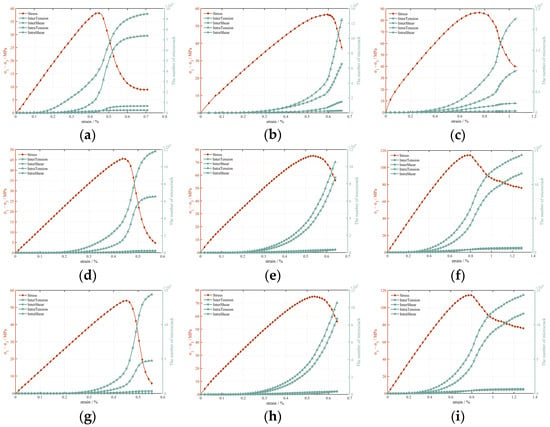

A total of nine simulations were conducted. During loading, both the macroscopic stress–strain response and the initiation and growth of microcracks were continuously recorded. Four categories of cracks were distinguished: intragranular tensile, intragranular shear, intergranular tensile, and intergranular shear. These classifications reflect distinct failure modes within mineral grains and at grain boundaries, thereby enabling a systematic characterization of damage processes at the grain scale. Figure 6 illustrates the stress–strain responses and the concurrent evolution of microcrack numbers, highlighting the correspondence between macroscopic deformation behavior and grain-scale damage processes in the three sandstone types under different confining pressures.

Figure 6.

Stress–strain curves and corresponding microcrack evolution of sandstones with different grain sizes under varying confining pressures: (a) CGS−0 MPa; (b) CGS−10 MPa; (c) CGS−20 MPa; (d) MGS−0 MPa; (e) MGS−10 MPa; (f) MGS−20 MPa; (g) FGS−0 MPa; (h) FGS−10 MPa; (i) FGS−20 MPa.

The numerical simulations consistently reproduce the principal experimental trends observed in the laboratory. Specifically, coarse-grained sandstones exhibit relatively low sensitivity of stress–strain behavior to confining pressure, whereas medium- and fine-grained sandstones display pronounced enhancement in plasticity with increasing confinement. It should be noted that, due to differences in mineralogical composition between the numerical models and the actual rock specimens, the simulated peak strength and elastic modulus are not identical to experimental values. Nevertheless, the overall mechanical response is highly consistent, confirming that the model captures the essential grainsize-dependent characteristics of sandstone deformation and failure under confining pressure.

The evolution of crack numbers is closely coupled with the stress–strain response at critical stages of loading. In the initial phase, cracks are virtually absent, corresponding to the linear elastic segment of the curve. As stress accumulates, microcracks begin to nucleate sporadically, and rapid crack proliferation occurs immediately prior to the peak, coinciding with the attainment of maximum stress and the onset of curve turning. Post peak, cracks continue to accumulate, but at a reduced rate, consistent with the gradual stress drop. This strong correspondence demonstrates that the simulations reliably capture the macro–micro coupling between deformation and damage evolution.

Under uniaxial compression, crack types are dominated by intergranular tensile cracks, followed by intragranular tensile cracks, while intergranular and intragranular shear cracks remain scarce. This indicates that failure is primarily controlled by debonding along grain boundaries without confinement, with tensile separation across interfacial weak planes being the dominant mode. As the confining pressure increases to 10 and 20 MPa, a marked shift occurs: intragranular tensile cracks increase significantly and gradually surpass intergranular cracks, indicating that confinement suppresses tensile debonding along grain boundaries and drives failure into the mineral grains. Confinement restricts relative displacement between grains, reducing the accumulation of tensile stress at interfaces while amplifying stress concentration within grains. Simultaneously, the proportion of shear cracks rises under higher confinement, reflecting more diverse crack propagation paths and partial release of strain energy through shear displacement. Correspondingly, the stress–strain curves exhibit a slower post-peak stress drop and enhanced ductility. This transition is consistent with experimental observations of a shift from tensile splitting to shear-dominated failure.

Comparisons among the three sandstone types highlight the grain size dependence of crack evolution. Fine-grained sandstones, with the smallest grain size and the most significant number of grains, contain the most densely distributed grain-boundary contacts. These abundant potential weak planes give rise to a predominance of intergranular tensile cracks under uniaxial compression, resulting in strongly brittle behavior. Medium-grained sandstones represent a transitional state, where intergranular cracking remains dominant but to a lesser extent, with increasing contribution from intragranular cracking. In coarse-grained sandstones, the small number of grains leads to fewer boundary contacts, so stress is more readily concentrated within the grains, producing a higher proportion of intragranular tensile cracks and a correspondingly more ductile response at the macroscopic scale.

With increasing confinement, intragranular cracks progressively dominate across all three sandstones. For fine- and medium-grained sandstones, the post-peak crack growth rate decreases, stress–strain curves gradually decline, and ductility is markedly enhanced. In contrast, coarse-grained sandstones show a different response: post-peak crack growth remains relatively high, and damage localizes in regions of heterogeneous cementation strength, leading to rapid strain energy release and steep post-peak stress drops. This non-monotonic behavior explains why coarse-grained sandstones in experiments exhibit only limited ductility enhancement, and in some cases, even renewed brittleness, with increasing confining pressure.

3.3. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Damage and Failure Modes in Sandstones of Different Grain Sizes

In Building on the preceding analysis of stress–strain responses and crack number evolution, which revealed the macroscopic mechanical behavior and fracture development of different sandstones under varying confining pressures, it remains clear that such aggregate measures cannot fully capture the spatial propagation of microcracks nor their correspondence with macroscopic failure patterns. To further elucidate the continuous transition from micro-scale damage accumulation to macro-scale instability, the present study incorporates the spatiotemporal evolution of crack apertures and sample fragments as key descriptors. Crack apertures were monitored in real time through secondary development of the code and normalized before visualization, thereby highlighting the relative intensity of crack activity and clarifying the dominant propagation paths during loading. Sample fragments were identified by re-clustering particles following bond breakage, with color-coded fragments representing discrete blocks that had lost cohesive bonding with surrounding grains. This representation directly characterizes the structural reorganization accompanying pre-peak damage nucleation and post-peak disintegration. Together, these two metrics provide a robust framework for capturing the spatiotemporal evolution of microcracks while clarifying the mechanisms underpinning macroscopic failure modes.

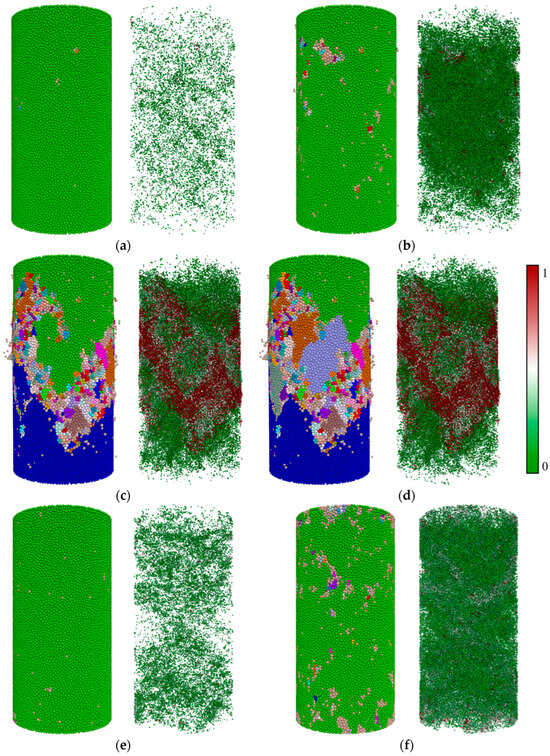

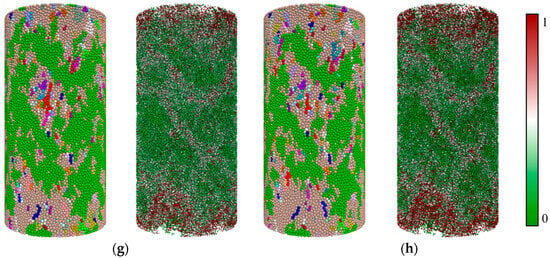

Figure 7 presents two representative cases: the evolution of fine-grained sandstone under uniaxial compression, and that of coarse-grained sandstone under a confining pressure of 20 MPa, thereby enabling a direct comparison of failure processes in low- versus high-confinement regimes across contrasting grain size classes.

Figure 7.

Representative spatiotemporal evolution of microcracks and fragments in digital sandstone models: (a) FGS—0 MPa—elastic stage; (b) FGS—0 MPa—pre-peak; (c) FGS—0 MPa—peak stress; (d) FGS—0 MPa—post-peak; (e) CGS—20 MPa—elastic stage; (f) CGS—20 MPa—pre-peak; (g) CGS—20 MPa—peak stress; (h) CGS—20 MPa—post-peak.

As shown in Figure 7, the spatiotemporal evolution of microcracks and sample fragments was captured for two representative sandstones at four characteristic loading stages (elastic stage, pre-peak, peak, and post-peak). During the elastic stage, no apparent macroscopic failure was observed, although a number of microcracks were already distributed within the specimen. These cracks exhibited extremely small apertures, scattered without clear orientation, reflecting the early-stage damage accumulation in the material. At this point, the macroscopic stress–strain curve remained in its linear regime, indicating that the influence of microcrack damage on the global mechanical response was still negligible. In the pre-peak stage, the number and aperture of microcracks increased significantly. In Figure 7, the 0–1 color scale represents the normalized time of microcrack occurrence, where 0 denotes the formation of the first microcrack in the specimen and 1 corresponds to the last recorded microcrack, with intermediate values indicating the relative time of formation. The normalized microcrack aperture revealed zones where local apertures enlarged markedly, forming concentrated damage regions. These regions with higher crack aperture tended to develop spatial continuity, thereby delineating potential failure bands. This transition corresponded closely to the stress–strain curve deviation from linearity as the specimen approached peak strength.

At the peak stage, distinct differences in failure modes were observed. Under uniaxial compression, the fine-grained sandstone exhibited a typical tension-dominated failure mode. The crack aperture increased sharply along the loading direction and penetrated through the specimen, with a clearly defined dominant fracture path forming a macroscopic splitting plane. Fragment identification further indicated that numerous independent blocks emerged along this splitting surface, demonstrating a rapid and brittle collapse [8]. In contrast, the coarse-grained sandstone under 20 MPa confining pressure displayed a dual failure characteristic: first, the crack aperture increased markedly along an inclined zone in the specimen center, forming a shear band; second, additional high-aperture crack clusters developed near the specimen ends, leading to end-region fragmentation. These two failure features are highly consistent with experimental observations under comparable loading conditions.

In the post-peak stage, both fine- and coarse-grained sandstones exhibited further in-creases in crack aperture, and fragment boundaries became more distinct, indicating progressive disintegration of the specimen. However, no new large-scale failure patterns emerged compared to the peak stage. For the fine-grained sandstone, post-peak evolution was dominated by the widening of the main splitting fracture, reflecting a pronounced brittle behavior. For the coarse-grained sandstone, the post-peak response was characterized by continued growth of the shear band and end fragmentation, accompanied by an increase in fragment number [9]. Nevertheless, the overall failure mechanism remained similar to that at peak, still reflecting a predominantly brittle mode of behavior.

The simulated grain size dependence of microcrack patterns and macroscopic responses is also consistent with published grain-based DEM studies. Previous numerical investigations have shown that fine-grained models tend to develop more pervasive intergranular tensile cracking and higher peak strength, whereas coarse-grained models favor mixed-mode cracking and the formation of localized shear zones at lower stresses [26,27]. Our calibrated grain-based models reproduce these general features for reservoir sandstones and, in addition, explicitly link the transition from intergranular to mixed intra- and intergranular cracking with the experimentally observed evolution from brittle splitting to more ductile responses in fine- and medium-grained sandstones, and the limited ductility enhancement in coarse-grained sandstone under confinement. Nevertheless, it should be recognized that the adopted GBM calibration strategy does not represent a pure geometric grain size sweep. A common base set of micro-parameters is first calibrated against a reference sandstone, and empirical grain size-dependent weakening factors are then applied to the grain-boundary bonds of the medium- and coarse-grained models to reproduce their stress–strain responses. The three numerical realizations therefore correspond to three calibrated sandstone classes rather than a single material with only its grain size varied, and the simulations should be regarded primarily as mechanistic, interpretive models constrained by the laboratory tests, reproducing the observed grain size dependence of strength and failure because the empirically calibrated bond weakening is imposed, rather than providing an independent proof of the underlying causality. Finally, it should be emphasized that both the experiments and the GBM simulations presented here pertain to dry, isothermal mechanical loading conditions; the potential influence of pore fluids and thermal effects on grain size-dependent deformation and failure is not addressed in this study and remains an important topic for future work.

4. Conclusions

This study integrates laboratory testing with discrete element simulations to systematically elucidate sandstones’ deformation and failure mechanisms with varying grain sizes under different confining pressures, from macroscopic mechanical response to microcrack evolution and spatiotemporal fracture patterns. The findings not only validate the reliability of the numerical model but also provide deeper insights into the grain size-controlled damage and failure processes of sandstones. These insights further offer practical implications for stability assessment and safer design in deep energy extraction and subsurface engineering applications. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Laboratory results show clear grain size control on strength and ductility. Under uniaxial compression, fine-grained sandstone exhibits the highest strength but the most pronounced brittleness; coarse-grained sandstone shows lower strength but greater axial strain at peak (on average about 17% higher than that of FGS) and a more gradual post-peak response; medium-grained sandstone lies between these two end-members. With increasing confining pressure, fine- and medium-grained sandstones undergo a marked transition toward more ductile behavior, whereas coarse-grained sandstone exhibits only limited ductility enhancement, indicating weak confinement sensitivity.

- (2)

- The calibrated DEM simulations reproduce these macroscopic trends and clarify the link between crack evolution and mechanical response. Under uniaxial loading, fine-grained sandstone is dominated by intergranular tensile cracking, leading to splitting-type failure along grain boundaries, whereas coarse-grained sandstone develops a higher proportion of intragranular cracks associated with more distributed deformation. Intragranular cracks account for about 22.1%, 34.7% and 42.8% of the total number of microcracks in FGS, MGS and CGS, respectively. As confining pressure increases, the failure process evolves from intergranular tension-dominated behavior to a mixed intragranular tension–shear mechanism, accompanied by progressive enhancement in macroscopic ductility.

- (3)

- Analyses of crack aperture distributions and fragment development reveal a continuous transition from microscopic damage accumulation to macroscopic instability. Fine-grained sandstone under uniaxial compression rapidly develops a through-going tensile fracture band, and fragments separate along a distinct splitting plane, characteristic of brittle failure. In contrast, coarse-grained sandstone at high confinement forms central shear bands combined with localized end failure; although post-peak cracking continues, the response remains governed by early shear localization and retains an overall brittle nature.

Author Contributions

R.Y.: Formal Analysis (equal), Data Curation (equal), Project Administration (equal). S.L., G.L. (Gaoren Li) and W.N.: Validation (equal); X.Z. and J.Z.: Methodology (equal); X.Y.: Software, Writing—Original Draft Preparation (equal); G.L. (Gao Li): Funding Acquisition, Methodology (equal), Validation (equal). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51674217).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Ronghui Yan, Sanjun Liu, Xiaogang Zhang, Gaoren Li, Wancai Nie and Jibin Zhong were employed by the PetroChina Changqing Oilfield Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Jaeger, J.C.; Cook, N.G.W.; Zimmerman, R. Fundamentals of Rock Mechanics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hallbauer, D.K.; Wagner, H.; Cook, N.G.W. Some observations concerning the microscopic and mechanical behaviour of quartzite specimens in stiff, triaxial compression tests. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1973, 10, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapponnier, P.; Brace, W.F. Development of stress-induced microcracks in Westerly granite. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1976, 13, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, R.L. Microcracks in rocks: A review. Tectonophysics 1983, 100, 449–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, B.K. Subcritical crack growth in geological materials. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1984, 89, 4077–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrich, J.T.; Evans, B.; Wong, T.F. Effect of grain size on brittle and semibrittle strength: Implications for micromechanical modelling of failure in compression. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1990, 95, 10907–10920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wong, L.N.Y.; Teh, C.I. Influence of grain size heterogeneity on strength and microcracking behavior of crystalline rocks. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2017, 122, 1054–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J.; Bésuelle, P.; Viggiani, G. Micromechanisms of inelastic deformation in sandstones: An insight using x-ray micro-tomography. Géotech. Lett. 2013, 3, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Nardelli, V.; Coop, M.R. Micro-mechanical behaviour of artificially cemented sands under compression and shear. Géotech. Lett. 2017, 7, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brace, W.F.; Bombolakis, E.G. A note on brittle crack growth in compression. J. Geophys. Res. 1963, 68, 3709–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.; Baud, P. The brittle-ductile transition in porous rock: A review. J. Struct. Geol. 2012, 44, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heap, M.J.; Baud, P.; Meredith, P.G.; Bell, A.F.; Main, I.G. Time-dependent brittle creep in Darley Dale sandstone. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2009, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, P.; Meredith, P.; Townend, E. Permeability evolution during triaxial compaction of an anisotropic porous sandstone. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potyondy, D.O.; Cundall, P.A. A bonded-particle model for rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2004, 41, 1329–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzard, J.F.; Young, R.P. Simulating acoustic emissions in bonded-particle models of rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2000, 37, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtès, L.; Donzé, F.V. A DEM model for soft and hard rocks: Role of grain interlocking on strength. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2013, 61, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Li, Z.; Feng, J.; Wang, K. Mesoscopic modeling approach and application based on rock thin slices and nanoindentation. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 165, 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Song, X.; Geng, J. Heterogeneity indexes of unconventional reservoir shales: Quantitatively characterizing mechanical properties and failure behaviors. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2023, 171, 105577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Kwok, C.Y.; Duan, K. Size effects on crystalline rock masses: Insights from grain-based DEM modeling. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 171, 106376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Zhao, L.; Song, X.; Tang, J.; Zhang, F. Fracability evaluation model for unconventional reservoirs: From the perspective of hydraulic fracturing performance. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2024, 183, 105912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Kuang, X. Mechanical Properties and Crack Evolution Characteristics of Sandstone Under Tensile Stress Based on DIC and Digital Simulation Technology. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yu, L.; Peng, Y.; Ju, M.; Yin, Q.; Wei, J.; Jia, S. Influence of grain size and basic element size on rock mechanical characteristics: Insights from grain-based numerical analysis. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wong, L.N.Y.; Teh, C.I. Effects of grain size-to-particle size ratio on micro-cracking behavior using a bonded-particle grain-based model. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2017, 100, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wong, L.N.Y.; Teh, C.I. Influence of grain size on strength of polymineralic crystalline rock: New insights from DEM grain-based modeling. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 13, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Xie, L.Z.; He, B.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, W. Effects of grain size distributions on the macro-mechanical behavior of rock salt using micro-based multiscale methods. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2021, 138, 104592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.F.; Sammis, C.G. The damage mechanics of brittle solids in compression. Pure Appl. Geophys. 1990, 133, 489–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammis, C.G.; Ashby, M.F. The failure of brittle porous solids under compressive stress states. Acta Metall. 1986, 34, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, C.H. The frequency-magnitude relation of microfracturing in rock and its relation to earthquakes. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1968, 58, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Zhao, L.; Lu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, F. Quantifying the effects of laminae on mechanical and damage characteristic of shale: Numerical investigation on digital rock models. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2025, 194, 106218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tao, M.; Ranjith, P.G. Novel insights into grain size effect of stressed crystalline rock using weakened grain boundary model. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2025, 189, 106098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Rutqvist, J.; Hu, M.S.; Wang, Z.Z.; Tang, X.H. Thermally induced microcracks in granite and their effect on the macroscale mechanical behavior. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2023, 128, e2022JB024920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Feng, G.; Lyu, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Tang, X. Upscaling mechanical properties of shale obtained by nanoindentation to macroscale using accurate grain-based modeling (AGBM). Energy 2025, 314, 134126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Rutqvist, J.; Hu, M.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Q. Determining Young’s modulus of granite using accurate grain-based modeling with microscale rock mechanical experiments. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2022, 157, 105167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Huang, H.; Zhang, F.; Han, Y. DEM-continuum mechanics coupled modeling of slot-shaped breakout in high-porosity sandstone. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 98, 103348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).