Research on the Prediction of Cement Precalciner Outlet Temperature Based on a TCN-BiLSTM Hybrid Neural Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

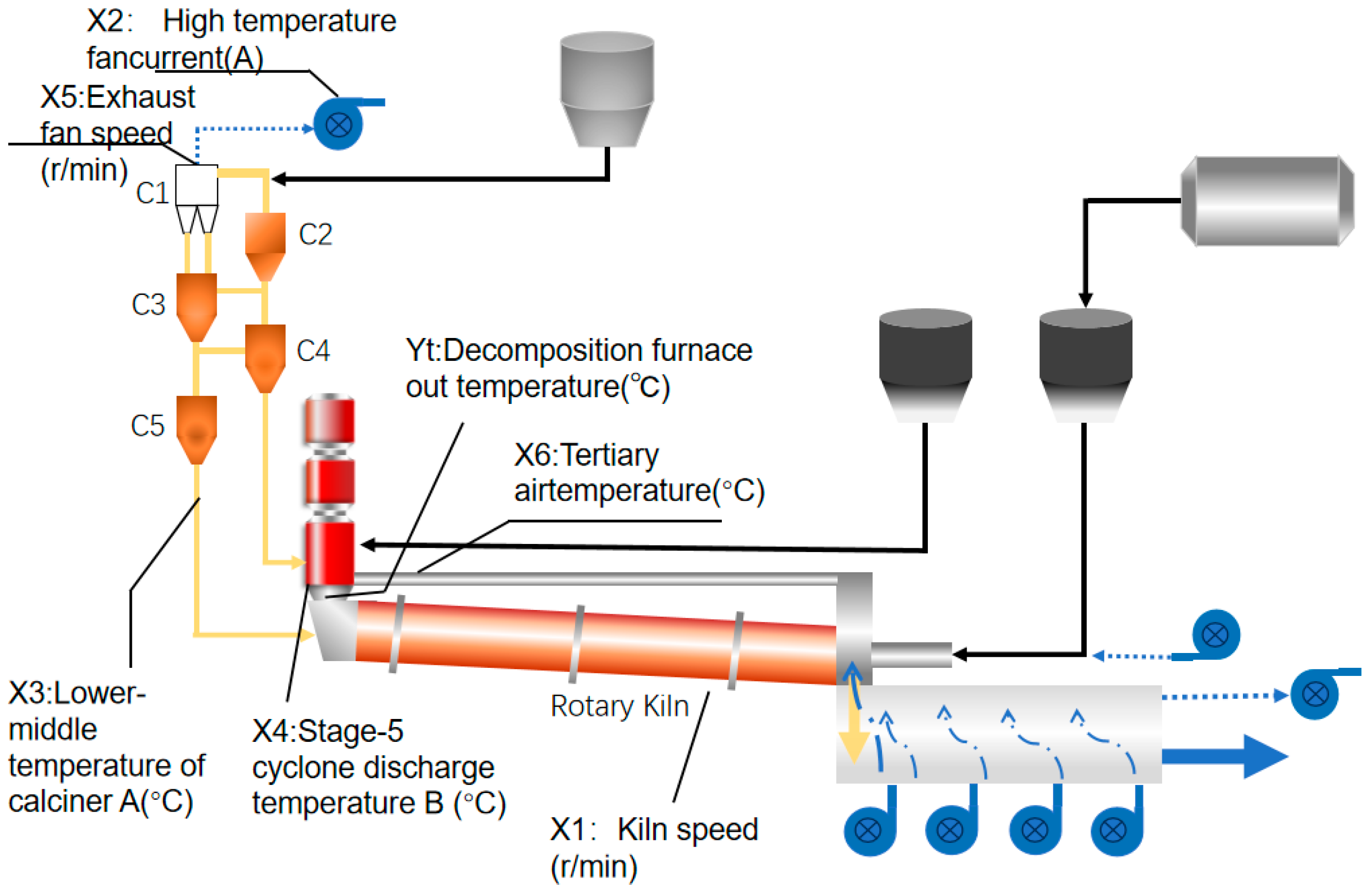

2. Process Description and Variable Selection

2.1. The Precalciner Kiln Process

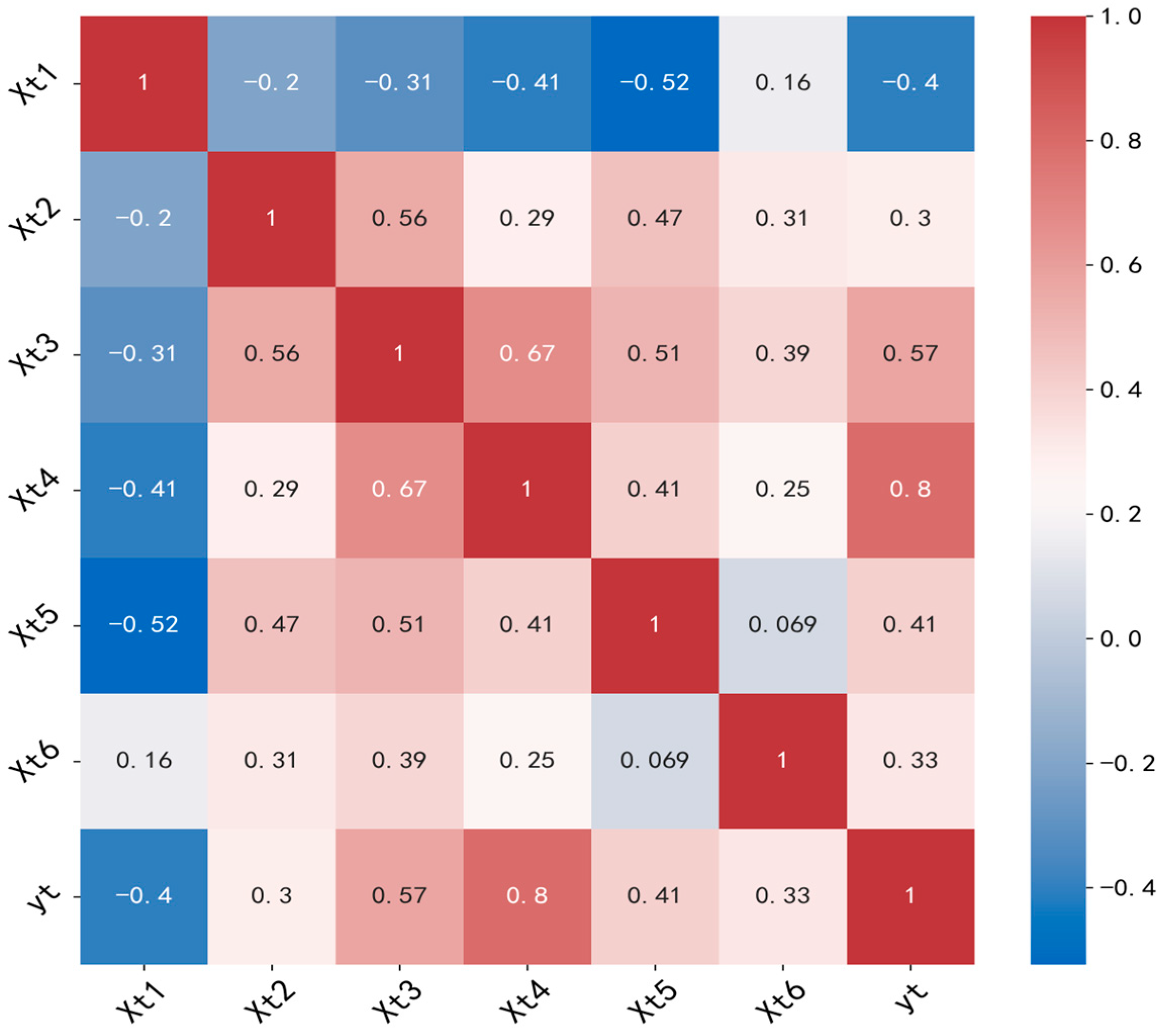

2.2. Variable Screening Using Spearman’s Rank Correlation

2.3. Sensitivity Analysis

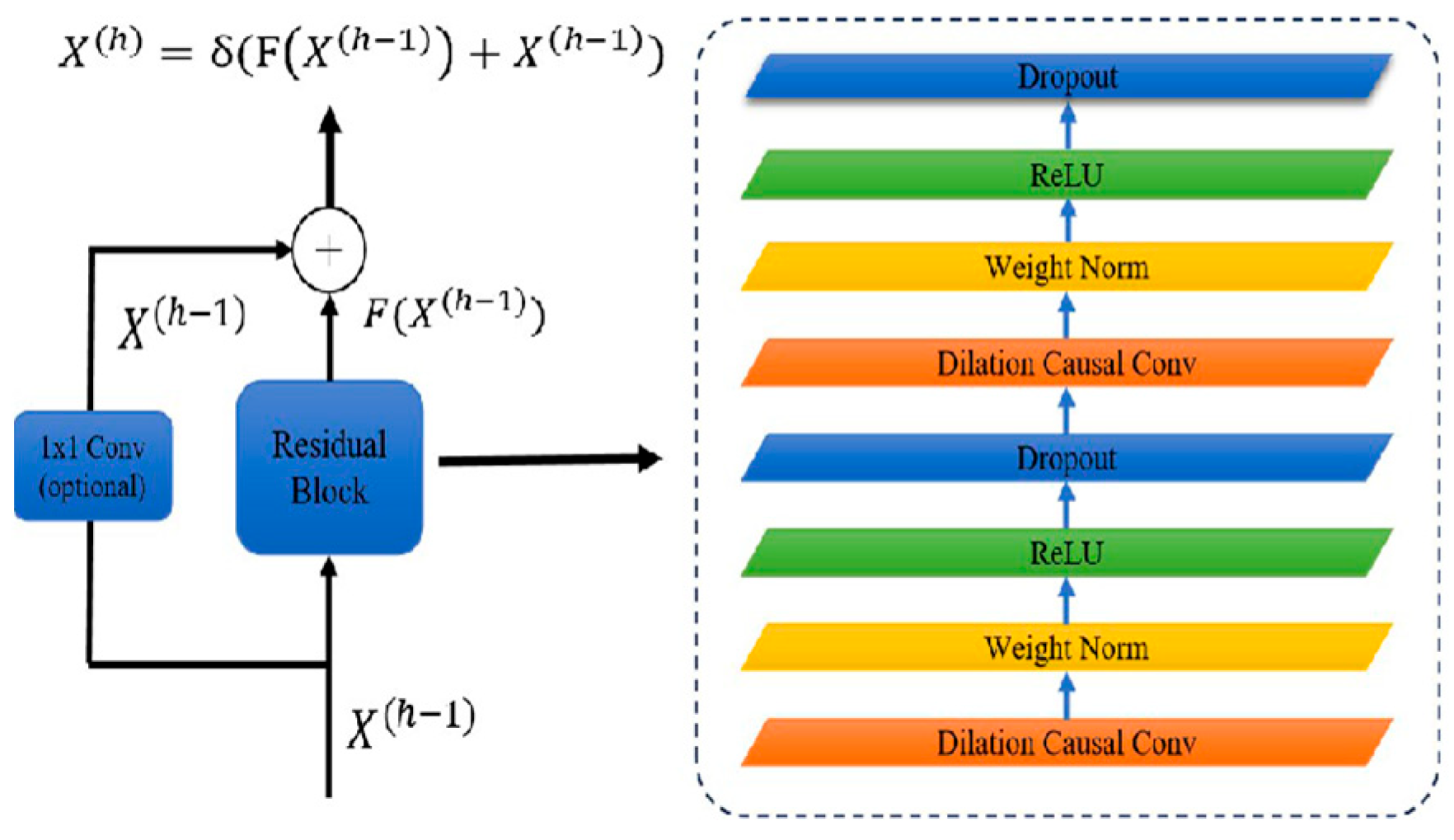

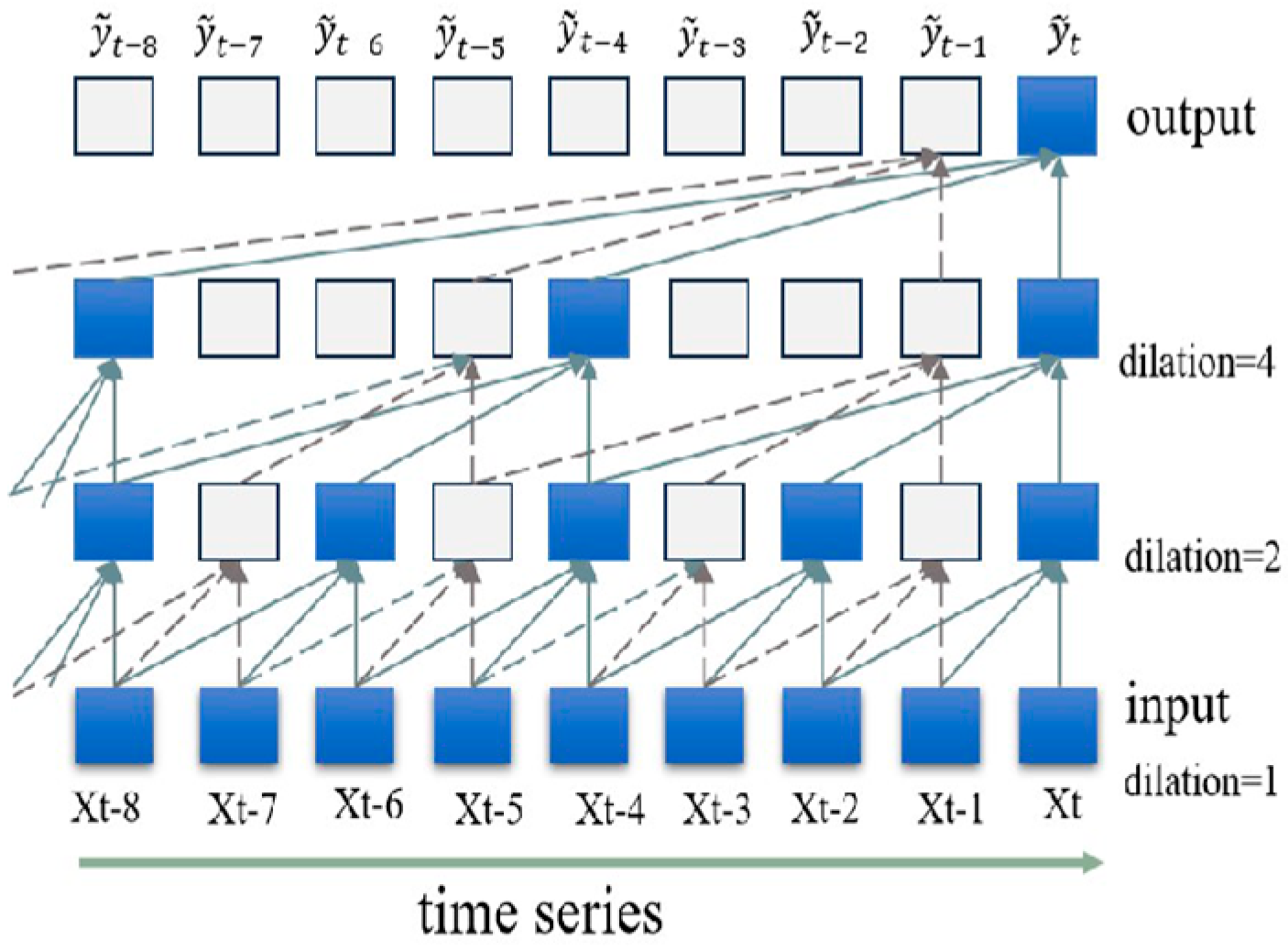

3. TCN-BiLSTM Model Construction

3.1. Residual Blocks and Causal Dilated Convolution

3.2. BiLSTM and TCN-BiLSTM

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Data Source and Preprocessing

- First, the data underwent cleaning to handle missing and anomalous values. Regarding outlier handling, model prediction residuals were analyzed, and 22 samples (5.2%) with residuals exceeding the 95th percentile were identified as outliers. After removal, RMSE decreased by 16.5%, and MAE decreased by 12.0%. Linear interpolation was applied to fill the outliers, ensuring data continuity while significantly improving the model’s prediction accuracy under normal operating conditions.

- Following this, the data were standardized using the formula:

- 3.

- Finally, the dataset is partitioned. To ensure the fairness of model evaluation and adhere to the causal nature of industrial time-series data, a strictly chronological dataset partitioning method is employed. The first 80% of the samples are allocated for model training, while the remaining 20% are reserved as an independent dataset that does not participate in training, serving to evaluate the model’s final generalization performance. To further optimize model hyperparameters and prevent overfitting, 10% of the training set is sequentially partitioned as a validation set.

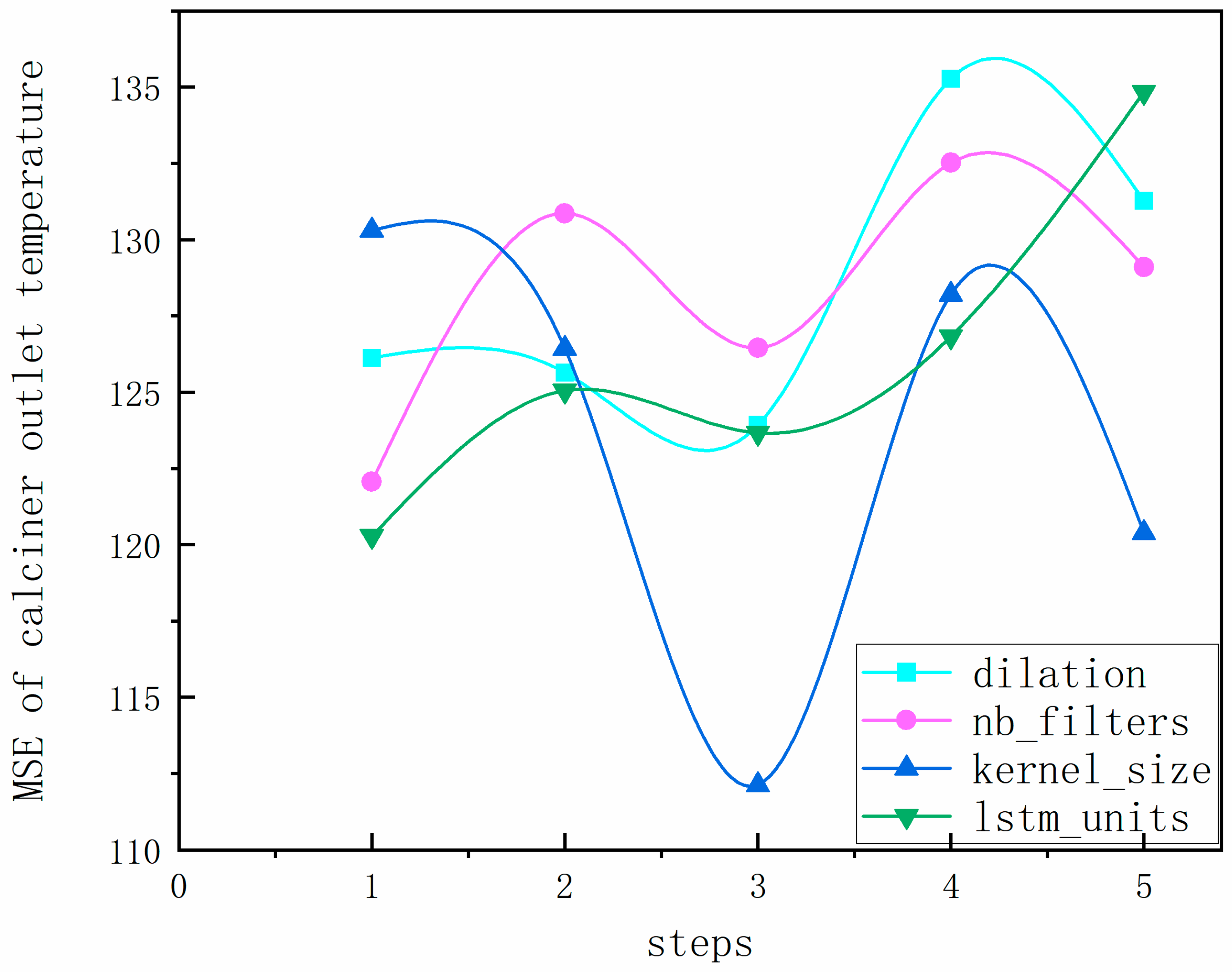

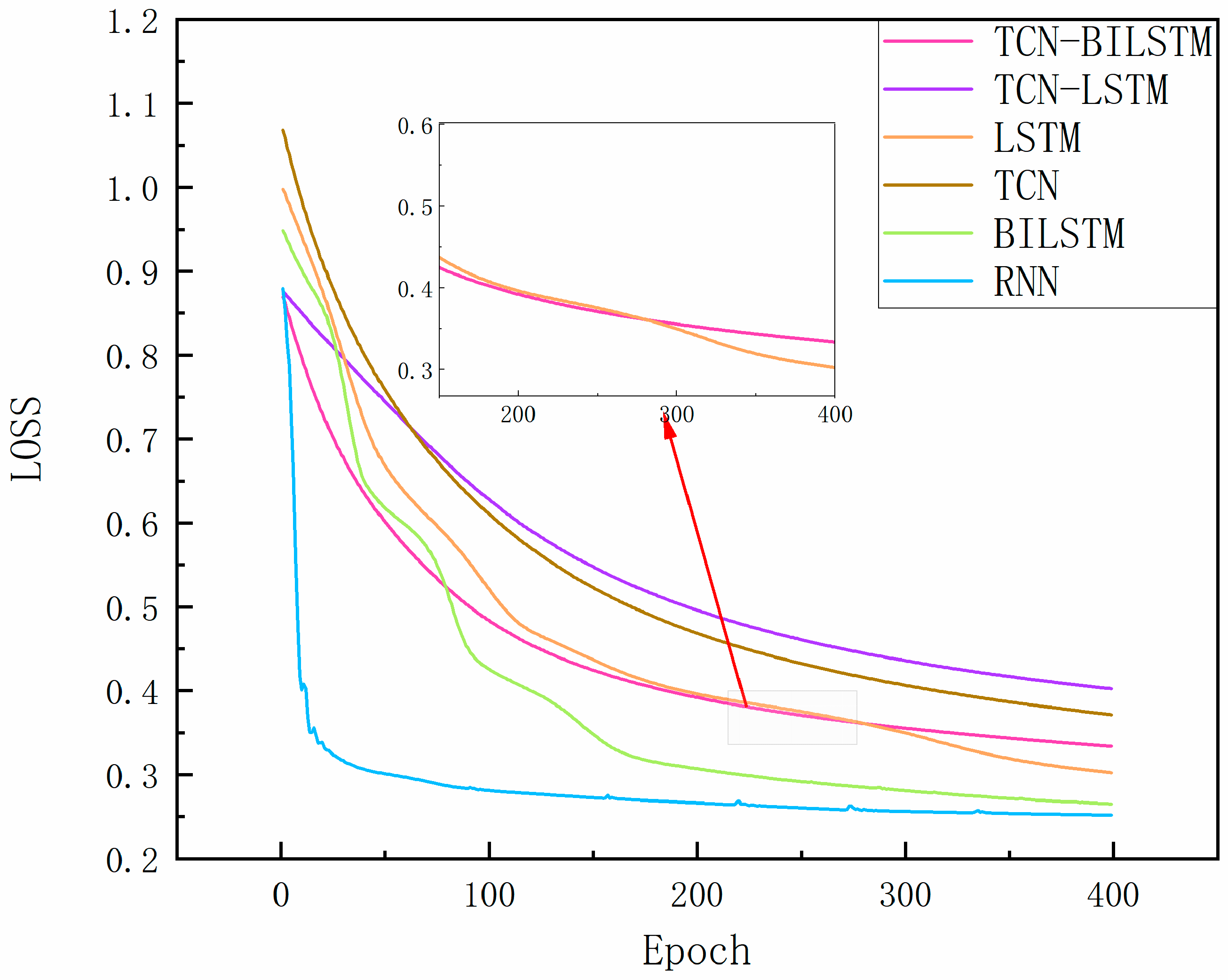

4.2. Selection of Optimization Algorithm and Model Parameters

4.3. Prevention of Temporal Data Leakage

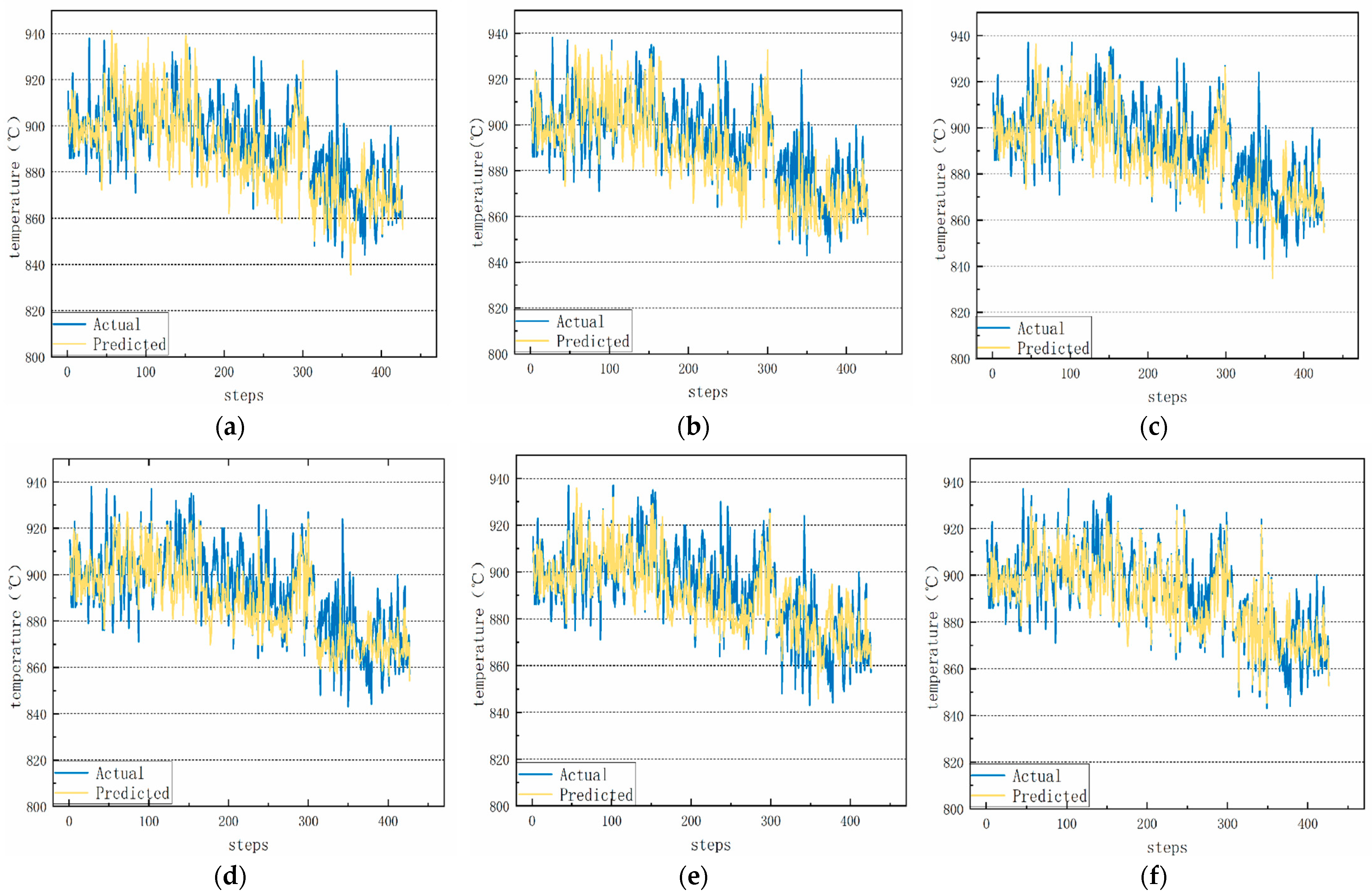

4.4. Comparative Analysis of Predictions

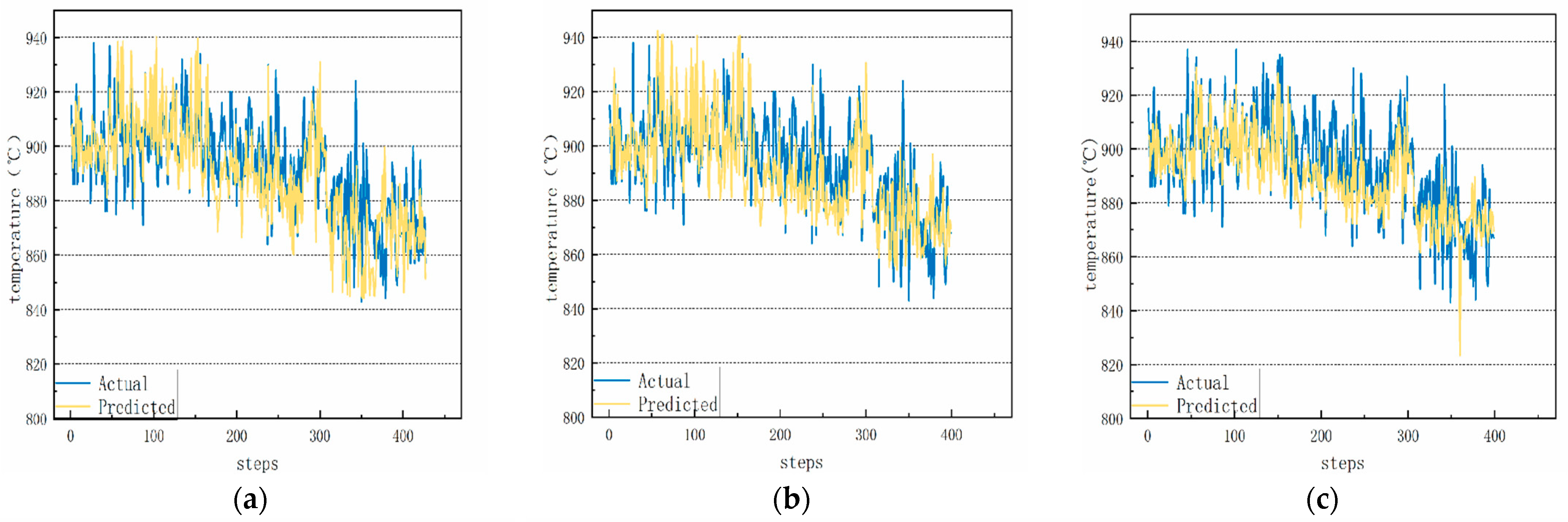

4.4.1. Short-Term Forecasting Analysis

4.4.2. Medium-Term Forecasting Analysis

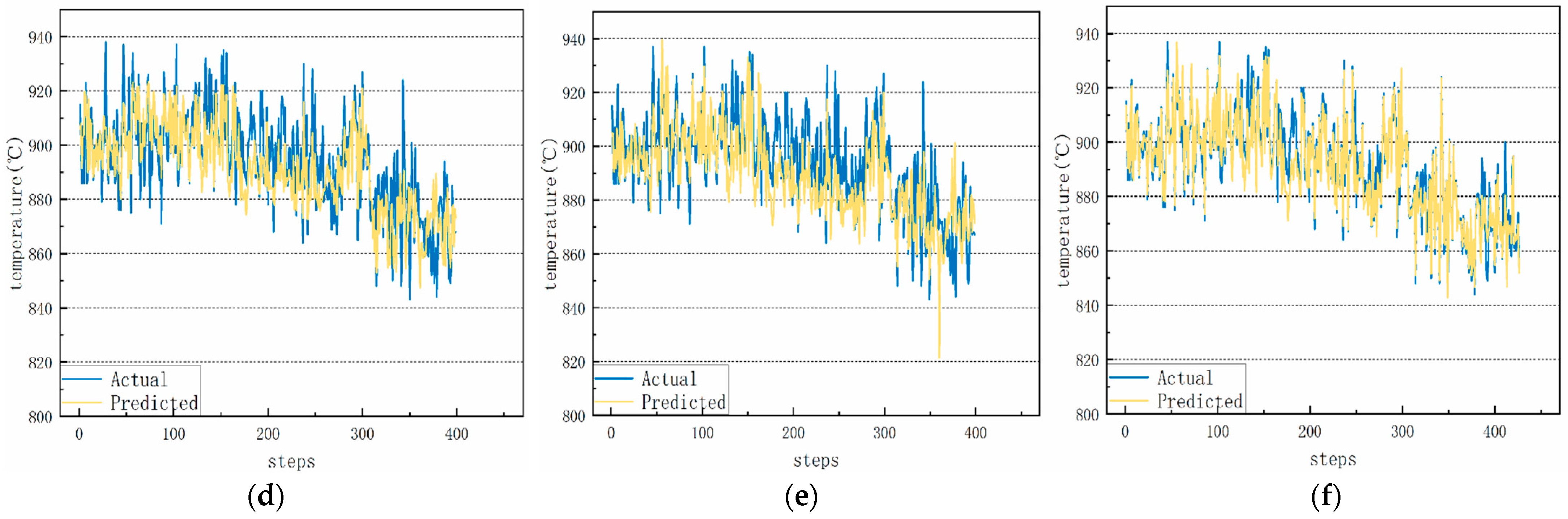

4.4.3. Long-Term Forecasting Analysis

5. Discussion

- (1)

- This study innovatively proposes a causally constrained TCN-BiLSTM hybrid architecture, which achieves synergistic enhancement through TCN’s long-term trend capture and BiLSTM’s bidirectional contextual modeling. The Spearman correlation coefficient is employed for key variable selection, ensuring predictive causality while providing a new reliable method for industrial time series forecasting.

- (2)

- The model enables high-precision, minutes-ahead temperature prediction for decomposition furnace operations, which can be directly applied to optimize real-time fuel and air distribution. This stabilizes thermal conditions, improves clinker quality, reduces energy consumption, and offers a feasible technical solution for intelligent control in cement production.

- (3)

- The current model’s performance relies on high-quality historical data, and its robustness to sensor anomalies or major process changes requires further validation. As a purely data-driven model, its integration with process mechanisms is insufficient, and its lightweight deployment in practical DCS systems necessitates additional research.

- (4)

- Future efforts will focus on developing self-learning models capable of adapting to operational condition changes, exploring deeper integration of data-driven and mechanistic models, and promoting the lightweight deployment and long-term operational validation of the model in edge computing environments.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Xu, K.; Sun, L.; Wu, Q.; et al. Modeling and control of the clinker calcination process in rotary kilns: A review. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 225, 115752. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdowski, W.; Duszak, S. Influence of precalciner temperature on free lime content and clinker phase composition in cement production. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 103, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, T.; Xu, L.; Zhou, W. Over-burning effect in cement clinker: Microstructure and grindability analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 218, 497–506. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An empirical evaluation of generic convolutional and recurrent networks for sequence modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Paliwal, K.K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1997, 45, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.A.; Zhang, T.; Lu, Y. PINN-CHK: Physics-informed neural network for high-fidelity prediction of early-age cement hydration kinetics. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 13665–13687. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Liu, P.; Guo, H.; Di, Y.; Xu, Q.; Hao, X. Control of Precalciner Temperature in the Cement Industry: A Novel Method of Hammerstein Model Predictive Control with ISSA. Processes 2023, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Mehmood, A.; Kim, H. Multivariate CNN with attention mechanism for rotary kiln temperature prediction. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 189, 116682. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Wang, K.; Hao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Q. SA-LSTMs: A new advance prediction method of energy consumption in cement raw materials grinding system. Energy 2022, 241, 122768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoji, A.I.; Anozie, A.N.; Omoleye, J.A.; Taiwo, A.E.; Babatunde, D.E. Evaluation of adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system-genetic algorithm in the prediction and optimization of NOx emission in cement precalcining kiln. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 54835–54845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Meng, P.; Liang, Y.; Li, J.; Miao, S.; Pan, Y. Research on lime rotary kiln temperature prediction by multi-model fusion neural network based on dynamic time delay analysis. Therm. Sci. 2024, 28, 2703–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, M. Nonlinear modeling of cement rotary kiln based on BP neural network with adaptive learning rate. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2019, 15, 3254–3262. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, S.; Chen, W.; Zhou, T.; Xu, F.; Sun, H. Hybrid RNN-attention model for delayed process variables prediction in cement kilns. Control Eng. Pract. 2021, 112, 104812. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Kamal, K.; Ratlamwala, T.A.H.; Sheikh, M.F.; Arsalan, M. Power prediction of waste heat recovery system for a cement plant using back propagation neural network and its thermodynamic modeling. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 9162–9178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Oliveira, R.; Costa, L. Deep reinforcement learning for rotary kiln temperature control in cement production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 6782–6790. [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi, G.; Ben Taieb, S.; Le Borgne, Y.A. Machine learning strategies for time series forecasting. In European Business Intelligence Summer School; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Atmaca, A.; Yumrutaş, R. Thermodynamic and exergoeconomic analysis of a cement plant. Energy 2014, 64, 454–468. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Shen, W.; Wu, C.Q.; Lyu, X. Optimizing Temperature Setting for Decomposition Furnace Based on Attention Mechanism and Neural Networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 9754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Chen, D.; Zhao, R.; Sun, P.; Li, J. Digital twin-driven temperature prediction for cement kilns using TCN-BiLSTM with attention mechanism. Appl. Energy 2023, 331, 120389. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, K.; Cao, S.; Li, J.; Xu, C. Prediction of neutralization depth of R.C. bridges using machine learning methods. Crystals 2021, 11, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veit, A.; Wilber, M.; Belongie, S. Residual networks behave like ensembles of relatively shallow networks. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 5–10 December 2020; pp. 550–558. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 12, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Cao, X.; Fan, Y.; Duan, Q. Simulation of future dissolved oxygen distribution in pond culture based on sliding-window temporal convolutional network and trend surface analysis. Aquacult. Eng. 2021, 95, 102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zhang, K.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, B. Parallel spatio-temporal attention-based TCN for multivariate time series prediction. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 13109–13118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Si, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J. A review of recurrent neural networks: LSTM cells and network architectures. Neural Comput. 2019, 31, 1235–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Shi, Y. Bi-directional LSTM with hierarchical attention for text classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 187, 115905. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Yang, Z.; Huang, J.; Deng, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y. A Landslide Displacement Prediction Model Based on the ICEEMDAN Method and the TCN-BiLSTM Combined Neural Network. Water 2023, 15, 4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Label | Physical Meaning | Symbol | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | Kiln speed | KS | rpm |

| X2 | High-temperature fan speed | HTFS | rpm |

| X3 | Mid-lower temperature of precalciner (A) | Tpml | °C |

| X4 | Stage-5 cyclone discharge temperature B | T5t | °C |

| X5 | Exhaust fan speed | EFS | rpm |

| X6 | Tertiary air temperature | Tta | °C |

| Yt | Outlet temperature of precalciner | Tout | °C |

| Input Variables | Maximum | Minimum | Average | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kiln rotation speed: X1 (r/min) | 4.73 | 2.41 | 4.069263602 | 0.309318701 |

| High-temperature fan speed: X2 (r/min) | 915 | 654 | 872.7514071 | 25.32727357 |

| Lower-middle temperature of calciner A: X3 (°C) | 951 | 739 | 879.1749531 | 27.37702543 |

| Outlet temperature of 5-stage cyclone B: X4 (°C) | 914 | 685 | 868.6266417 | 14.20531897 |

| Exhaust gas fan speed: X5 (r/min) | 627 | 472 | 524.2523452 | 31.48491656 |

| Tertiary air temperature of calciner: X6 (°C) | 1200 | 873 | 989.5206379 | 43.72847244 |

| decomposer exit outlet temperature: Yt (°C) | 938 | 837 | 887.1669794 | 16.66492248 |

| Parameters\Code | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kernel size | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| dilation | [1, 2, 4] | [1, 2, 4, 8] | [1, 2, 4, 8, 16] | [1, 2,…, 32] | [1, 2,…, 64] |

| filter size | 18 | 36 | 54 | 72 | 90 |

| Lstm_units | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 |

| Model | Parameter | MSE | RMSE | MRE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNN | hidden size = 8 | 145.6715 | 12.0695 | 0.0105 | 9.3536 |

| BILSTM | hidden size = 8 | 141.5709 | 11.8984 | 0.0105 | 9.3994 |

| TCN-LSTM | hidden size = 8 | 127.1515 | 11.2762 | 0.0098 | 8.7467 |

| LSTM | hidden size = 8 | 120.0579 | 10.9777 | 0.0096 | 8.6183 |

| TCN | dilation = [1, 2, 4, 8, 16], kernel size = 8 | 116.3618 | 10.7871 | 0.0092 | 8.2340 |

| TCN-BiLSTM | dilation = [1, 2, 4, 8, 16], kernel size = 8 | 112.1317 | 10.5892 | 0.0091 | 8.1598 |

| Model | Parameter | MSE | RMSE | MRE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNN | hidden size = 8 | 146.5660 | 12.1065 | 0.0108 | 9.6102 |

| BILSTM | hidden size = 8 | 143.9566 | 11.9982 | 0.0107 | 9.5764 |

| TCN-LSTM | hidden size = 8 | 130.3299 | 11.4162 | 0.0099 | 8.8382 |

| LSTM | hidden size = 8 | 129.0236 | 11.3589 | 0.0099 | 8.9034 |

| TCN | dilation = [1, 2, 4, 8, 16], kernel size = 8 | 128.6165 | 11.3409 | 0.0098 | 8.7304 |

| TCN-BiLSTM | dilation = [1, 2, 4, 8, 16], kernel size = 8 | 115.8858 | 10.7650 | 0.0094 | 8.4366 |

| Model | Parameter | MSE | RMSE | MRE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNN | hidden size = 8 | 150.3014 | 12.2599 | 0.0105 | 9.3184 |

| BILSTM | hidden size = 8 | 144.0579 | 12.0024 | 0.0104 | 9.3361 |

| TCN-LSTM | hidden size = 8 | 138.5509 | 11.7708 | 0.0102 | 9.2987 |

| LSTM | hidden size = 8 | 137.9496 | 11.7452 | 0.0102 | 9.2074 |

| TCN | dilation = [1, 2, 4, 8, 16], kernel size = 8 | 134.9029 | 11.6148 | 0.0097 | 8.6997 |

| TCN-BiLSTM | dilation = [1, 2, 4, 8, 16], kernel size = 8 | 118.5796 | 10.8894 | 0.0095 | 8.5002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, M.; Kao, H. Research on the Prediction of Cement Precalciner Outlet Temperature Based on a TCN-BiLSTM Hybrid Neural Network. Processes 2025, 13, 4068. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124068

Deng M, Kao H. Research on the Prediction of Cement Precalciner Outlet Temperature Based on a TCN-BiLSTM Hybrid Neural Network. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4068. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124068

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Mengjie, and Hongtao Kao. 2025. "Research on the Prediction of Cement Precalciner Outlet Temperature Based on a TCN-BiLSTM Hybrid Neural Network" Processes 13, no. 12: 4068. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124068

APA StyleDeng, M., & Kao, H. (2025). Research on the Prediction of Cement Precalciner Outlet Temperature Based on a TCN-BiLSTM Hybrid Neural Network. Processes, 13(12), 4068. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124068