Abstract

This study developed a process for producing prebiotic-fortified instant rice macaroni to diversify rice-based convenience foods. Resistant starch (RS) rice flour from three varieties—IR504 and two pigmented, anthocyanidin-rich rice cultivars (Huyet Rong and MS2019)—was blended with wheat flour and fixed ingredients (tapioca starch, salt, and vegetable oil at a ratio of 9g:1g:1g), together with hot water. The instant rice macaroni with the highest RS content (11.64%) was obtained using IR504 RS and wheat flour (44:6), gelatinized at 100 °C for 20 min, microwaved at 36 W/g for 30 s, retrograded at 4 °C for 24 h, and sterilized at 115 °C for 15 min. For anthocyanidin-containing macaroni, the combination of Huyet Rong RS and wheat flour (39:11) yielded 9.47% RS under similar retrogradation and sterilization conditions, but with a shorter gelatinization step (100 °C, 15 min) and longer microwave treatment (50 s at 27 W/g). The other optimized colored-RS formulation was based on MS2019 RS and wheat flour (21:29) processed under similar conditions. All optimized formulations exhibited lower estimated glycemic index (eGI) values of 64.1, 65.7, and 68.2, which were significantly lower than those of the control instant rice macaroni (78.2–85.9, p < 0.05). This study confirms the potential of developing instant rice macaroni rich in RS to enhance prebiotic effects that support the growth of beneficial intestinal bacteria, strengthen immune function, and improve nutritional quality through the incorporation of anthocyanidin-rich rice varieties and a processing procedure combining heat–moisture treatment with microwave heating.

1. Introduction

Macaroni is one of the most popular convenience foods due to its sensory qualities, nutritional value, and ease of preparation [1]. Approximately 14.3 million tons of pasta are produced annually worldwide, with Italy, the United States, Brazil, Türkiye, and Russia being the main producers [2]. Traditional macaroni is manufactured in Italy using durum wheat (Triticum durum), whereas in many other countries, pasta is produced from soft wheat or other cereal flour [1]. Pasta plays an important role in the Mediterranean diet. The WHO (World Health Organization) and the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) have described pasta as a healthy, sustainable, and high-quality dietary model [3]. Its success largely stems from its nutritional profile; macaroni is generally nutritious because of its low fat content and easily digestible carbohydrates [4]. Furthermore, pasta can serve as a vehicle for healthy components such as dietary fiber and prebiotics [5,6]. Its low cost and long shelf life make it accessible to a wide range of consumers [7].

Vietnam, a country with a long history of rice cultivation where rice remains a staple food, continues to face challenges in achieving high profitability despite large production volumes. In the third quarter of 2025, Vietnam exported nearly 6.8 million tons of rice, generating USD 3.5 billion (General Department of Vietnam Customs). However, the average price was only USD 0.47 per kg, significantly lower than global value-added products [8,9]. Therefore, the development of instant rice macaroni through the partial substitution of wheat flour with resistant starch (RS)-rich rice flour represents a promising strategy to enhance the value of Vietnam’s abundant rice resources. Unlike traditional wheat-based macaroni, which is largely composed of rapidly digestible starch, RS-fortified rice macaroni offers functional advantages, including a lower glycemic index, prebiotic potential, and reduced cooking time. In the context of a rice industry dominated by raw milling with limited economic returns, the advancement of RS-enriched products containing bioactive antioxidant compounds such as anthocyanidins represents a strategic shift toward high-value functional foods with strong global market potential.

Regarding digestibility, starch is typically divided into three fractions: rapidly digestible starch (RDS), slowly digestible starch (SDS), and resistant starch (RS) [10]. RDS and SDS are hydrolyzed into dextrins by α-amylase within 20 to 120 min after consumption. RS, in contrast, is defined as the starch fraction that escapes enzymatic digestion in the small intestine after 120 min [11]. It subsequently moves to the colon, where it serves as a nutrient source for beneficial gut bacteria [12]. The amount of RS in food varies among individuals due to differences in gastrointestinal motility, endogenous digestive enzyme levels, gastric juice viscosity, and characteristics of the food matrix itself [10].

RS has attracted considerable interest for its ability to modulate postprandial glycemic responses and promote gut health. Among various modification approaches, heat–moisture treatment (HMT) has been extensively studied as an effective method to enhance RS content in cereal starches [13]. HMT performed under controlled conditions—temperatures of 100–120 °C, moisture content of 20–30%, and durations of 2–12 h—has been shown to enhance RS content, particularly in high-amylose rice [14]. This increase is accompanied by physicochemical changes such as reduced solubility, decreased swelling power, and elevated gelatinization temperatures [15], which collectively contribute to a lower glycemic index [16]. Similarly, microwave irradiation, a non-ionizing radiation technique, induces partial gelatinization and structural modifications through localized heating and pressure under appropriate moisture contents [17,18]. While combined with retrogradation, microwave treatment facilitates the reorganization of amylose chains into type-3 resistant starch (RS3) [19]. However, studies combining the application of HMT, microwave treatment, and retrogradation to enhance RS content in instant rice macaroni derived from specific Vietnamese rice cultivars such as IR504, red rice (Huyet Rong), and purple rice (MS2019) have not yet been fully optimized for these particular cultivars.

Although low-glycemic foods have gained increasing attention, research applying the combined HMT, microwave, and retrogradation process to produce instant rice macaroni from Vietnamese rice varieties is still scarce. To address this gap, the present study investigated three rice cultivars with distinct amylose levels—MS2019 (8.46%), Huyet Rong (19.48%), and IR504 (21.92%) [20]. The objective is to optimize formulation and processing parameters to maximize RS content while maintaining desirable physicochemical and sensory properties, thereby offering a viable, high-value solution for the rice-processing industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The raw materials used in this study included RS obtained from rice of three cultivars (IR504, Huyet Rong, and MS2019). The rice was cleaned and soaked in 0.15 M citric acid using a thermostatic water bath (WNB15, Memmert, Schwabach, Germany) at 55 °C for 1 h. The treated rice was then subjected to wet-grinding using Goodfor (MQXN-Đ, Manh Quan Electromechanical Production & Trading Co., Ltd., Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam) grinder equipment to obtain rice flour. The rice flour slurry was heated at 70 °C for 15 min in an electric steamer (YW-FT-D3, Changhe, Ningbo, China) until complete gelatinization. The gelatinized flour mixture was cooled to 50 °C and treated with pullulanase enzyme under the following conditions: substrate concentration of 30%; enzyme activity of 30 U/g (0.71 mL of pullulanase at 3000 U/g for 30 g sample) in a pH 5 buffer solution. Hydrolysis was carried out in a thermostatic water bath (WNB15, Memmert, Schwabach, Germany) at 50 °C for 50 min. Following hydrolysis, the flour rice slurry was retrograded at 4 °C for 24 h in a refrigerator (VH-408WL, Sanaky, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam). The retrograded rice flour was washed with distilled water and centrifuged. The obtained rice flour was subsequently dried in an oven (UN55, Memmert, Schwabach, Germany) at 45 °C until the moisture content reached <13%. After the process of increasing RS, MS2019 rice flour has the following traits: lipids, 0.73 g/100 g; protein, 12.4 g/100 g; starch, 65.4 g/100 g; amylose, 31.43%. Huyet Rong rice flour has the following traits: lipids, 0.72 g/100 g; protein, 6.60 g/100 g; starch, 65.5 g/100 g; amylose, 49.76%. IR504 rice flour has the following traits: lipids, 1.14 g/100 g; protein, 9.67 g/100 g; starch, 70.6 g/100 g; amylose, 66.87%.

Other ingredients were also purchased from Bach Hoa Xanh supermarket (Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam) and used to prepare macaroni samples, including tapioca starch (≥70% glucides, ≤20% moisture); wheat flour (12.5% protein, ≥75% glucides); iodized salt with NaCl content > 97%; iodine content (20/40 mg/kg salt); insoluble impurity content < 0.3%; and vegetable oil with a minimum iodine index (Wijs) of 57.

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

The chemicals used were acetic acid (CH3COOH), sodium acetate (CH3COONa), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), 95% and 99% ethanol (C2H5OH), maleic acid, potassium hydroxide, and citric acid, all of which were purchased from Shantou, China. The pullulanase enzyme (pullulan 6-α-glucanohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.41) was derived from the non-genetically modified Pullulanibacillus naganoensis AE-PL strain and supplied by Amano Enzyme Inc. (Nagoya, Japan). In addition, a resistant starch test kit was provided by Megazyme, Bray, Ireland.

2.3. Processing

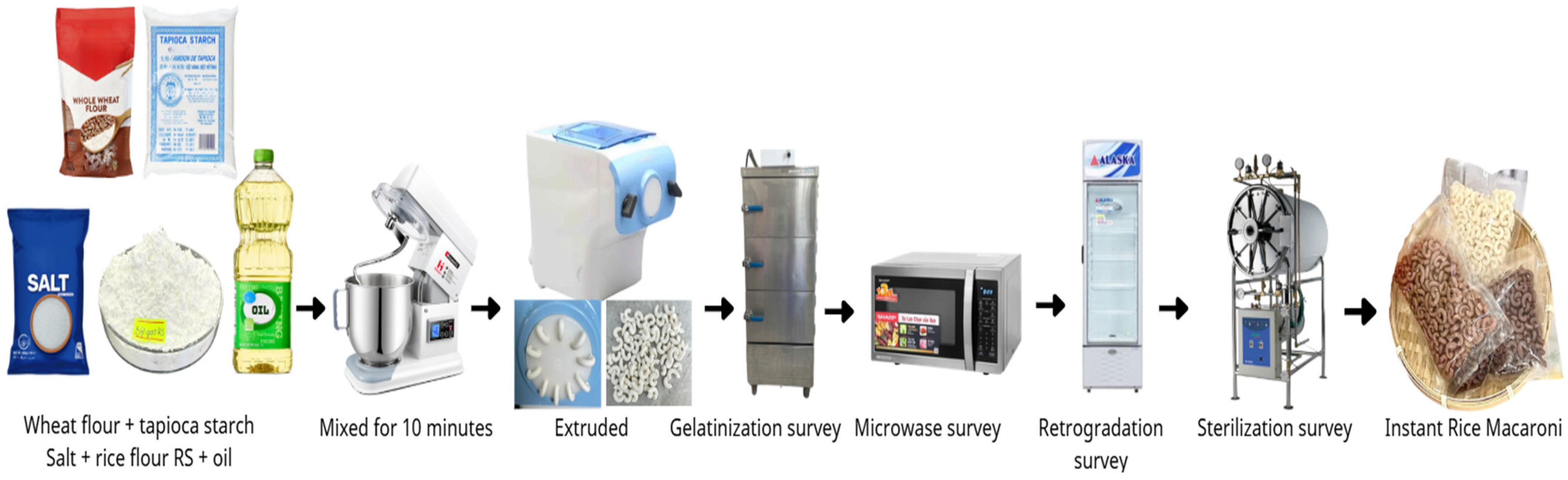

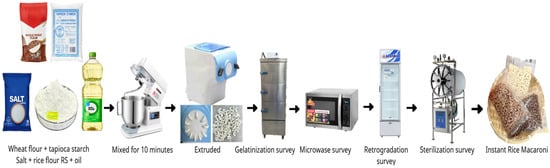

This preliminary survey establishes the processing parameters for producing prebiotic instant rice macaroni as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Scheme of prebiotic instant rice macaroni production.

The ingredients were mixed in a Dough Mixer (5KPM5EWH, KitchenAid, Greenville, USA) according to the ratios presented in Table 1, yielding dough moisture contents of 30–42%. A Philips extruder (HR2330, Philips, Zhuhai, China) was used to shape the dough into rice macaroni under a compressive force of 720kg, using a shaping die with an orifice diameter of 4 mm. The dough was extruded through the shaping die by the combined action of dough mass and pressure at the screw tip, ensuring uniformity and structural consistency. Gelatinization was carried out by steaming the macaroni after extrusion in an electric steamer (YW-FT-D3, Changhe, Ningbo, China), with steaming time evaluated at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 min. The microwave treatment parameters in a Microwave Oven (R-G728XVN-BST, Sharp, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam) were varied by both time (10, 30, 50, 70, and 90 s) and power (9, 18, 27, 36, and 45 W/g). Retrogradation was investigated using a 312-L Alaska freezer model (BCD 5068C, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam) at three temperatures (−18 °C, 4 °C, and 30 °C) and five durations (6, 12, 18, 24, and 30 h). For sterilization, temperatures of 105, 110, 115, 120, and 125 °C and times of 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 min were examined using a horizontal autoclave (MEDSOURCE TC–409A, Sturdy, Taichung, Taiwan).

Table 1.

Effect of mixing ratio on dough moisture.

2.4. Effect of Mixing Ratio on RS Content

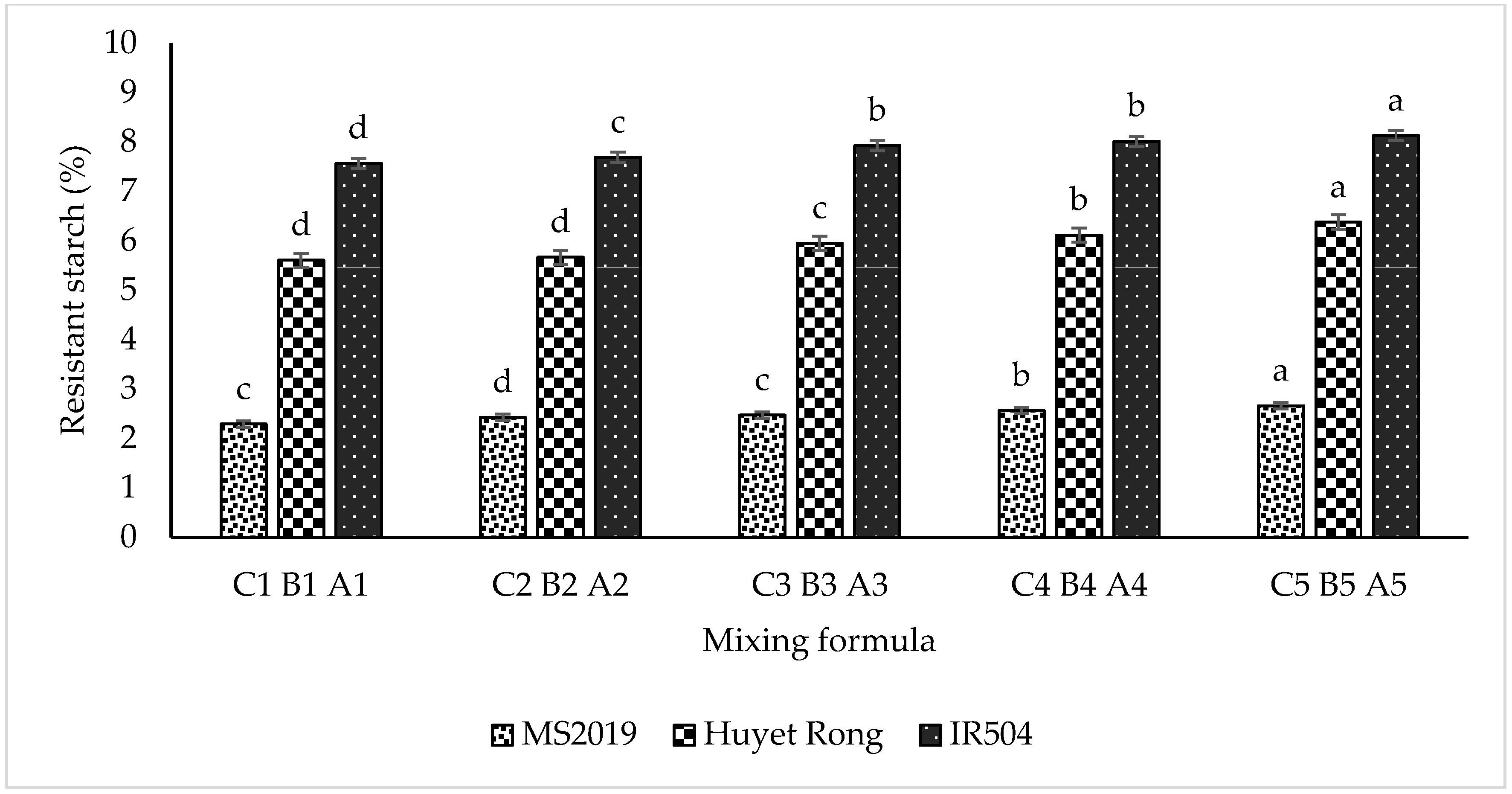

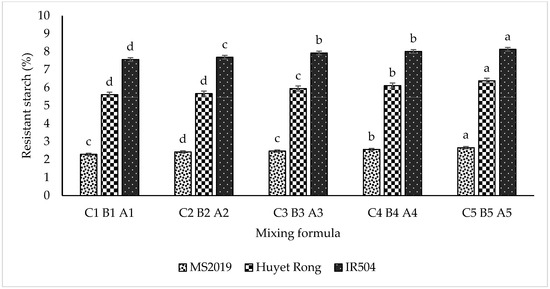

The three types of rice flour with enhanced resistant starch (RS), as shown in Figure 2, used in this study are IR504 (RS: 20.08 ± 1.055 g/100 g), Huyet Rong (RS: 15.87 ± 0.968 g/100 g), and MS2019 (RS: 10.75 ± 0.987 g/100 g), each evaluated with five different mixing ratios. For RS-rich IR504 rice starch, the ratios examined were A1 (35:15), A2 (38:12), A3 (41:9), A4 (44:6), and A5 (47:3) (RS rice flour–wheat flour, %). For RS-rich Huyet Rong rice flour, the ratios were B1 (30:20), B2 (33:17), B3 (36:14), B4 (39:11), and B5 (42:8). Similarly, for RS-rich MS2019 rice flour, the ratios were tested C1 (15:35), C2 (18:32), C3 (21:29), C4 (24:26), and C5 (27:23) (RS rice flour–wheat flour, %). In all formulations, the fixed ingredients included 9 g of tapioca starch, 1 g of salt, 1 g of vegetable oil, and an appropriate amount of hot water to achieve a dough moisture content ranging from 30 to 42%, ensuring desirable shape retention and structural integrity of the instant rice macaroni. The ingredients were mixed in a Phillips macaroni maker for 15 min, extruded, steamed at 100 °C for 10 min, dried at 50 °C for 3 h until the moisture content was <12%, and then ground and sieved through a 0.125 mm mesh to prepare samples for RS analysis. The results of this experiment were used to determine the optimal blending formula for subsequent stages of the research.

Figure 2.

Process for increasing RS content in rice flour (IR504, Huyet Rong, and MS2019).

2.5. Effect of Starch Gelatinization Time on RS Content

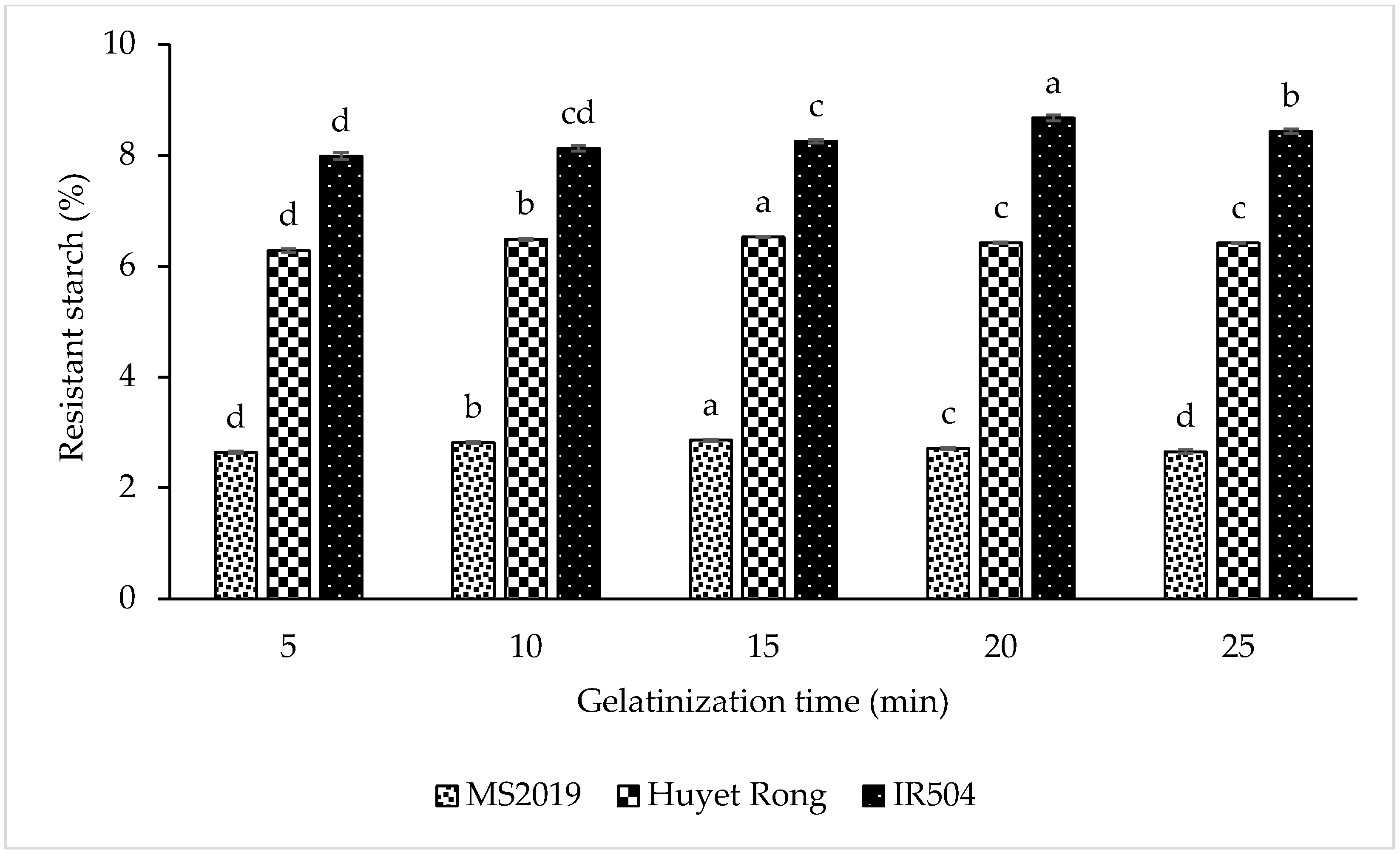

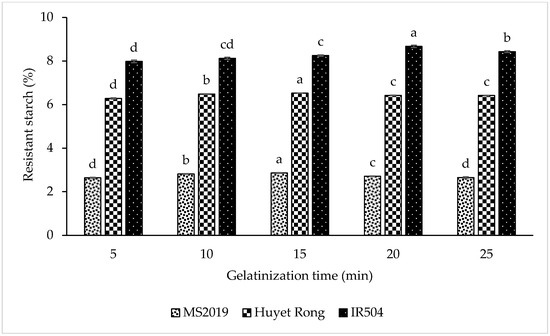

The experiment investigating the effect of gelatinization time on RS content was conducted at five time intervals referenced from previous studies: 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 min [21]. During gelatinization, the combined action of heat and moisture increases the mobility of starch chains, promoting interactions between amylose and amylopectin that facilitate the formation of resistant starch 3 (RS3). The results indicated that gelatinization time significantly affected RS content in the rice varieties studied. Specifically, RS content increased as gelatinization time increased, reaching a maximum at 20 min for IR504 and at 15 min for both Huyet Rong and MS2019, followed by a slight decline, which occurred with prolonged heating. Therefore, the optimal gelatinization time selected for subsequent experiments was 20 min for IR504 and 15 min for the other two varieties.

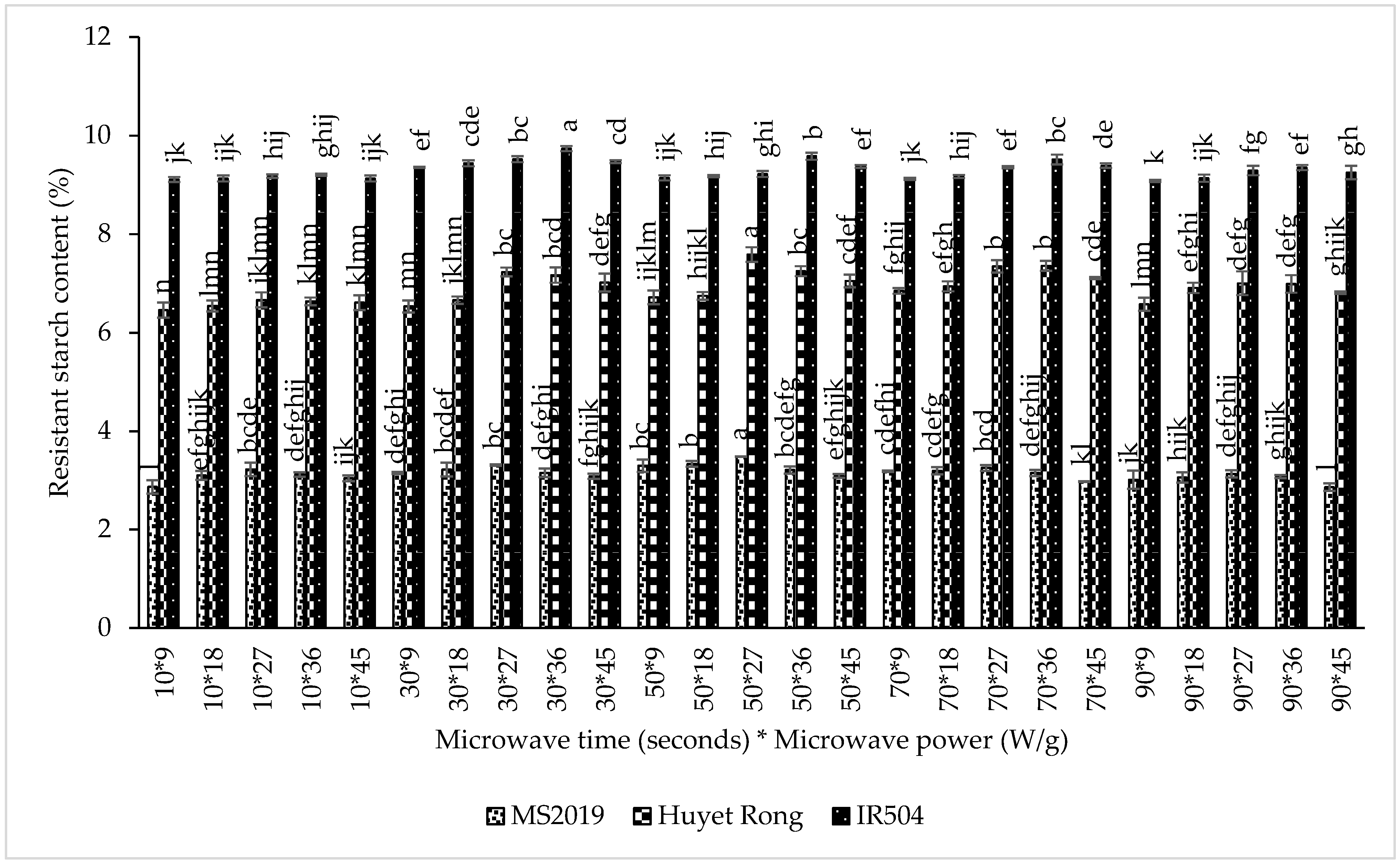

2.6. Effect of Microwave Processing on RS Content

Microwave treatments can rearrange starch molecular structures, resulting in changes in digestibility, water absorption, solubility, viscosity, gel strength, and gelatinization parameters [22]. The microwave power levels were 9, 18, 27, 36, and 45 (W/g) corresponding to 90 W, 180 W, 270 W, 360 W, and 450 W/10 g of instant rice macaroni for the IR504, Huyet Rong, and MS2019 varieties [23,24,25]. Treatment times were 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 s, respectively [22,26]. After microwave treatment, the samples were cooled, dried, milled, and analyzed for RS content. The results showed that moderate microwave power, combined with shorter exposure times, increased RS content, likely due to the partial gelatinization and structural reorganization of starch molecules that favored RS3 formation. However, excessive power or prolonged exposure decreased RS content due to RS structural retrogradation. Optimal microwave conditions were identified for each rice variety to maximize RS content and were subsequently applied in later processing stages.

2.7. Effect of Retrogradation Processing on RS Content

In this study, a hydrothermal treatment (HT) was applied using a post-gelatinization retrogradation process to determine the optimal temperature for maximizing RS content [27]. The tested retrogradation temperatures were −18 °C, 4 °C, and room temperature (≈30 °C), while the retrogradation durations were 6, 12, 18, 24, and 30 h [28]. The experiment followed a factorial combination of both factors to evaluate their effects on RS content.

2.8. Effect of Sterilization Processing on RS Content

The general mechanism of hydrothermal treatment involves applying heat and moisture to starch granules for a defined duration to increase the mobility of starch chains. This enhanced mobility facilitates interactions between amylose and amylopectin, leading to structural rearrangements within the amorphous regions and partial disruption of crystalline domains. Upon cooling and retrogradation, these molecular changes promote the formation of type 3 resistant starch (RS3). The extent of these modifications depends on the starch composition and structure, as well as the moisture content and temperature applied during treatment. Sterilization was conducted to ensure microbiological safety and to evaluate the thermal stability of the RS structures previously formed [29]. The samples were autoclaved at 105, 110, 115, 120, and 125 °C for 10, 15, and 20 min.

2.9. Microbiological Analysis

Identification of Bacillus cereus according to ISO 7932:2004: Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuff—horizontal method for the enumeration of presumptive Bacillus cereus—colony-count technique at 30 °C.

Identification of Salmonella spp. according to ISO 6579-1:2017: Microbiology of the food chain—horizontal method for the detection, enumeration, and serotyping of Salmonella—Part 1: Detection of Salmonella spp.

Identification of total aerobic microorganisms according to ISO 4833-1:2013: Microbiology of the food chain—horizontal method for the enumeration of microorganisms—Part 1: Colony count at 30 °C by the pour plate technique.

Identification of yeasts and molds according to ISO 21527-2:2008: Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs—horizontal method for the enumeration of yeasts and molds—Part 2: Colony-count technique in products with water activity less than or equal to 0.95.

Identification of Staphylococcus aureus according to AOAC 987.09: Staphylococcus aureus in foods. Most probable number method for isolation and enumeration.

Identification of Escherichia coli according to ISO 16649-2:2001: Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs—horizontal method for the enumeration of β-glucuronidase-positive Escherichia coli—Part 2: Colony-count technique at 44 °C using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-glucuronide.

Identification of Coliforms according to ISO 4832:2007: Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs—horizontal method for the enumeration of Coliforms—colony-count technique.

Identification of Clostridium botulinum according to AOAC 977.26: Clostridium botulinum and its toxins in foods. Microbiological method.

Identification of Clostridium perfringens according to ISO 7937:2004: Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs—horizontal method for the enumeration of Clostridium perfringens—colony-count technique.

2.10. Determine the Color of Macaroni

A Minolta CR410 colorimeter (Konica Minolta Co., Tokyo, Japan) was used to measure the color of the samples under illuminant D65 with a 10° viewing angle. Color parameters were expressed in the CIELAB color space, where L* represents lightness, a* represents the red–green axis, and b* represents the yellow–blue axis. Whiteness Index (WI) was calculated according to the following equation [30]:

2.11. Textural Measurement of Macaroni by TPA

Hardness of the sterilized instant rice macaroni was measured using a Brookfield CT3 Texture Analyzer (Brookfield Engineering Laboratories, Inc., Middleboro, MA, USA) equipped with a TA10 cylindrical probe (12.7 mm diameter). The samples were placed on a testing platform, and a two-cycle compression test (Texture Profile Analysis) was performed under the following conditions: pre-test speed, 1.0 mm/s; test and return speed, 1.5 mm/s; trigger force, 0.1 N; and compression strain, 60%. Measurements were collected from samples taken from three positions within each retort pouch, with three independent replicates for each condition [31].

2.12. In Vitro Determination of Glycemic Index (GI)

An accurately weighed 0.05 g sample was dissolved in HCl-KCl buffer (0.1 M; pH 1.5) and incubated with 0.2 mL pepsin solution (1 g/10 mL HCl-KCl, 220 U/mL) at 40 °C for 1 h to simulate the gastric phase and minimize protein–starch interactions. The reaction mixture was then adjusted to pH 6.9 by adding 25 mL of Tris-maleate buffer (0.1 N) to inactivate pepsin and provide optimal conditions for the intestinal digestion phase. Subsequently, a 5 mL aliquot was collected to represent the 0 min time point. Additional aliquots (5 mL each) were collected at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min. Each aliquot was placed in a centrifuge tube and heated in a boiling water bath (100 °C) for 5 min to terminate enzymatic activity and then cooled to room temperature. For glucose determination, 1 mL of the digested sample was mixed with 3 mL of sodium acetate buffer (0.4 M, pH 4.75) and 60 μL of amyloglucosidase (3300 U/mL). The mixture was incubated at 60 °C for 45 min and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min. The resulting supernatant was diluted 11-fold by mixing 100 μL of the supernatant with 1 mL of sodium acetate buffer (0.4 M, pH 4.75) in a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube. The released glucose concentration was quantified using the glucose oxidase–peroxidase (GOPOD) enzyme assay following the procedure used for resistant starch determination [32].

2.13. Data Analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent measurements (Microsoft Excel 2019 software, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate differences among treatments, and mean separations were conducted using Fisher’s least significant difference test at a significance level of p < 0.05. Pearson correlation coefficient, least-squares regression, and first-order regression analyses were carried out using Minitab (version 20, State College, PA, USA). The area under the hydrolysis curve (AUC) was calculated using GraphPad Prism (version 8.4.2, USA).

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Mixing Ratio on Rice Macaroni Dough Moisture and Resistant Starch Content

The results of the five mixing formulations for each rice flour variety (IR504, SR20, and MS2019) are presented in Table 1, illustrating the relationship between the RS rice flour-to-wheat flour ratio and the resulting dough moisture content.

Specifically, for the IR504 variety, RS content increased progressively from samples A1 to A5, with values of 7.565%, 7.693%, 7.929%, and 8.017% and a maximum of 8.132% (Figure 3). A similar trend was observed in the Huyet Rong variety, where RS content increased from 5.61% in sample B1 to 6.381% in sample B5. In contrast, the MS2019 variety exhibited significantly lower RS values, ranging from 2.29% to 2.66% across samples C1 to C5. This increasing trend is consistent with the higher proportion of RS-enriched starch incorporated into the formulations [33]. Furthermore, differences in RS content among varieties can be attributed to genetic factors, starch molecular structure, and the specific mechanisms governing RS formation. Varieties such as IR504 and Huyet Rong have higher amylose (AM) content, which favors RS development due to amylose’s strong tendency to retrograde and resist enzymatic hydrolysis. Conversely, MS2019 contains a higher proportion of amylopectin (AP), which retrogrades poorly and, therefore, contributes less to RS formation [34,35]. These findings highlight that intrinsic starch characteristics—particularly the amylose–amylopectin ratio—play a critical role in RS formation. The high RS content in IR504 is considered beneficial to health, notably in blood glucose regulation, digestive support, and reducing the risk of intestinal diseases. Additionally, the varieties contain significant quantities of anthocyanidins (cyanidin-3-glucoside), red rice—Huyet Rong (0.10 g/100 g), and purple rice—MS2109 (0.11 g/100 g), which are potent antioxidants that may help reduce cardiovascular risk, provide anti-inflammatory effects, and aid in cancer prevention [36]. As shown in Table 1, the resistant starch (RS) content increased with the proportion of RS-enriched rice starch in the formulation. The most structurally suitable rice macaroni products, based on physical and textural characteristics, are presented in Table 1. Specifically, formulations A4 and B4 were found to be optimal for the IR504 and Huyet Rong rice cultivars, whereas formulation C3 demonstrated better compatibility with the MS2019 cultivar.

Figure 3.

Effect of blending ratio on resistant starch content. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of 3 replicates. Different letters within the same column indicate statistically significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

3.2. Effect of Starch Gelatinization Time on RS Content

Heat–moisture treatment alters starch granules by exposing them to controlled levels of heat and moisture for a defined period, thereby increasing the mobility of starch chains. This enhanced mobility promotes interaction between AM and AP, resulting in structural rearrangements within the amorphous regions and partial disruption of crystalline domains. Upon cooling and retrogradation, these molecular changes facilitate the formation of type 3 resistant starch (RS3). The extent of these modifications depends on starch composition and structure, as well as the moisture content and temperature applied during treatment [29]. However, the effect on resistant starch content varies with treatment duration [37].

The results showed that the RS content increased progressively as gelatinization time was extended (Figure 4). For the IR504 variety, RS content rose from 7.981% at 5 min to 8.123% (10 min) and 8.251% (15 min), and it reached a maximum of 8.670% at 20 min. A similar pattern was observed in the Huyet Rong variety, where RS content increased from 6.281% (5 min) to 6.482% (10 min) and 6.522% (15 min). In the MS2019 variety, RS content also increased during the first 15 min of gelatinization, from 2.640% to 2.815% and 2.858%. The initial rise in RS content can be attributed to granule swelling and gelatinization in the presence of water, which enhances amylose leaching and promotes amylose chain reorganization during cooling, thereby facilitating RS3 formation [38,39]. However, extending gelatinization beyond the optimal point resulted in a reduction in RS content. For IR504, RS content decreased to 8.427% at 25 min. In Huyet Rong, RS content declined slightly to 6.420% (20 min) and 6.416% (25 min). In MS2019, RS content decreased significantly from 2.858% (15 min) to 2.710% (20 min) and 2.650% (25 min). This decline is likely due to excessive granule disruption and excessive amylose leaching under prolonged heating, which reduces the starch’s ability to retrograde and form RS3 [40]. A similar study indicated that the RS content of canna starch was affected by gelatinization time [41]. Overall, significant differences were observed among the varieties. The RS content was arranged in the following order: IR504 (8.670%) > Huyet Rong (6.522%) > MS2019 (2.858%). Therefore, gelatinization for 20 min (IR504) and 15 min (Huyet Rong and MS2019) gave the highest RS value, which was selected for further studies.

Figure 4.

Effect of gelatinization time on resistant starch content. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of 3 replicates. Different letters within the same column indicate statistically significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

3.3. Effect of Microwave Processing on RS Content

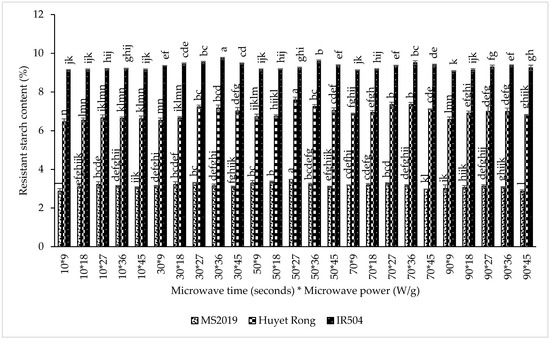

The results indicated that microwave power had a significant influence on RS content. In the IR504 variety, RS content increased from 9.161% at 9 W/g to a maximum of 9.477% at 36 W/g. A similar upward trend was observed for Huyet Rong, where RS content increased from 6.625% to 7.165% at 27 W/g, and for MS2019, from 3.101% to 3.279% at the same power level. These findings are consistent with previous reports on lotus seed starch and arrowroot starch, where moderate microwave energy enhanced RS development [42,43]. The increase in RS with increasing microwave power can be attributed to the disruption of intramolecular hydrogen bonds and partial unwinding of double helices, accompanied by cleavage of α-1,6 linkages, which increases molecular mobility and facilitates subsequent amylose reorganization during cooling [19,25]. The increase in RS with increasing microwave power can be attributed to the disruption of intramolecular hydrogen bonds and partial unwinding of double helices, accompanied by cleavage of α-1,6 linkages, which increases molecular mobility and facilitates subsequent amylose reorganization during cooling. Microwave exposure time also affected RS content. For IR504, RS levels increased from 9.149% at 10 s to 9.505% at 30 s. In Huyet Rong, RS increased from 6.581% at 10 s to 7.118% at 70 s, while MS2019 showed an increase from 3.069% to 3.281% between 10 and 50 s. This trend suggests that short- to medium-duration microwave treatment promotes the formation of shorter amylose chains and enhances molecular rearrangement, enabling double-helix formation and increasing RS content [25,27]. Prolonged exposure, however, results in water evaporation and structural collapse, thereby reducing RS formation.

However, when the microwave exposure time exceeded the optimal range, RS content began to decline (Figure 5). For IR504, RS decreased from 9.505% at 30 s to 9.221% at 90 s. A similar reduction was observed in Huyet Rong, where RS decreased from 7.118% at 70 s to 6.856% at 90 s. In MS2019, RS content dropped to 3.026% after 90 s of microwave treatment. Prolonged microwave exposure likely caused excessive structural disruption, including extensive granule breakdown and excessive amylose fragmentation, which reduced the ability of amylose chains to reassociate into double helices during cooling, resulting in lower RS formation [44]. Based on these results, the optimal microwave conditions identified for subsequent experiments were 36 W/g for 45 s for the IR504 variety and 27 W/g for 50 s for both the Huyet Rong and MS2019 varieties.

Figure 5.

Effect of microwaving on resistant starch content in instant rice Acacia prebiotics (IR504, Huyet Rong, MS2019). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of 3 replicates. Different letters within the same column indicate statistically significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

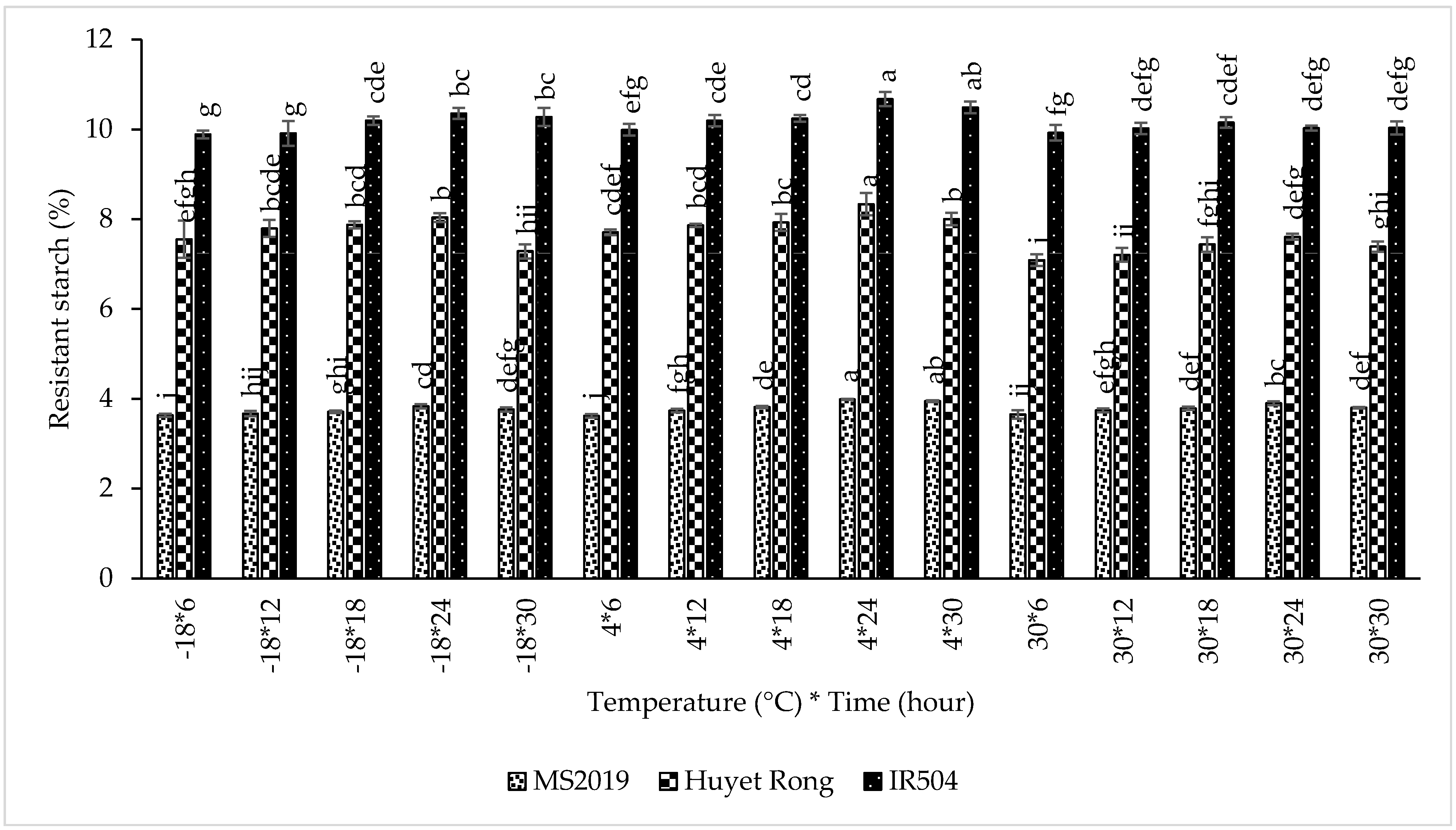

3.4. Effect of Retrogradation Processing on RS Content

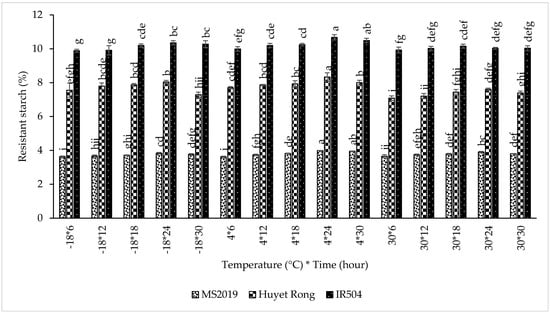

This study examined the retrogradation of linear amylose chains through microwave treatment and enzymatic hydrolysis, focusing on their reassociation into double-helical structures. The primary objective was to determine the optimum retrogradation temperature that yields the highest RS content. This experiment was conducted on the microwave-treated samples from the previous stage. Retrogradation was evaluated at three temperatures (−18 °C, 4 °C, and room temperature) for durations ranging from 6 to 30 h to assess their effects on RS formation. The results confirmed that retrogradation temperatures strongly influenced RS development. When the retrogradation was carried out at 4 °C, RS content increased markedly in all varieties. In IR504, RS content increased from 10.032% at −18 °C to 10.319% (4 °C). Similarly, RS increased from 7.346% to 7.968% in Huyet Rong and from 3.723% to 3.822% in MS2019. Some previous studies have likewise reported that cooling at 4 °C promotes greater RS formation than freezing at −18 °C, as amylose molecules in gelatinized and partially fragmented starch undergo more effective reassociation and double-helix formation during cold storage, thereby enhancing RS3 development [45,46].

Next, the effect of retrogradation time was evaluated. RS content increased as retrogradation time was extended (Figure 6). For the IR504 variety, RS content rose from 9.935% at 6 h to a maximum of 10.352% at 24 h, followed by a slight decrease to 10.266% at 30 h. However, the difference between 24 h and 30 h was not statistically significant. A similar increasing pattern was observed in the Huyet Rong variety, where RS content increased from 7.449% to 7.993%, and in MS2019, where RS increased from 3.636% to 3.907%. These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting that RS levels in bread increased during the first 3–4 days of storage at 4–20 °C due to progressive amylose retrogradation [45]. Likewise, freezing at −18 °C was shown to increase RS levels during the initial storage period, with minimal changes thereafter [47]. Overall, retrogradation at 4 °C for 24 h produced the highest RS content across all three rice varieties and was, therefore, selected as the optimal condition for subsequent experiments.

Figure 6.

Effect of retrogradation processing on RS content in prebiotic-like instant rice macaroni (IR504, Huyet Rong, MS2019). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of 3 replicates. Different letters within the same column indicate statistically significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

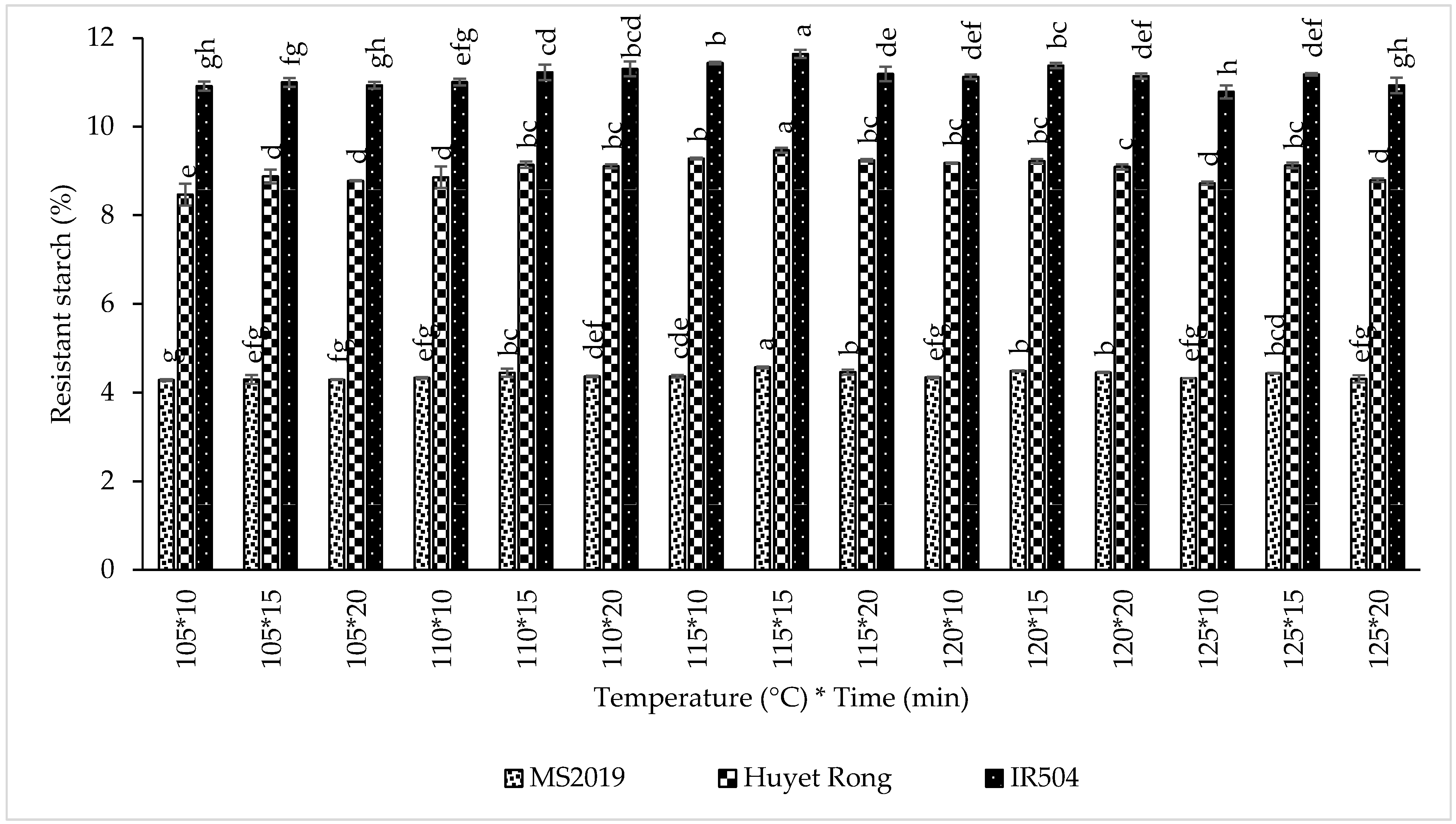

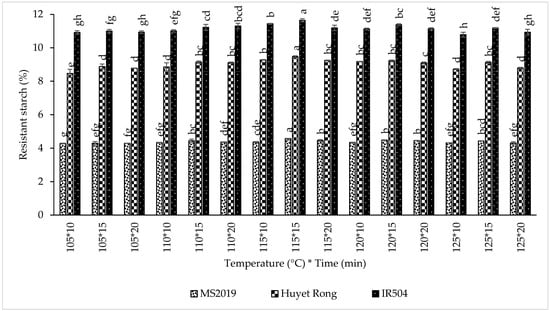

3.5. Effect of Sterilization Processing on RS Content

When comparing sterilization temperatures, RS content followed the same ranking across all varieties: 115 °C > 120 °C > 110 °C > 125 °C > 105 °C. For IR504, RS content increased in the order 11.424% > 11.215% > 11.179% > 10.967% > 10.951%, respectively. Similar trends were observed for Huyet Rong (9.329% > 9.166% > 9.036% > 8.880% > 8.708%) and MS2019 (4.468% > 4.429% > 4.382% > 4.358% > 4.291%). The results showed that the sample sterilization at 115 °C produced the highest RS content in all three varieties [48]. The increase in RS with rising sterilization temperature is consistent with previous studies. In one study, high-temperature sterilization of corn starch at 121 °C produced greater RS yields than treatment at 100 °C, and RS yield in wheat starch increased from 2.5% at 100 °C to 9% at 134 °C [49]. This enhancement is attributed to stronger gelatinization and greater amylose leaching at elevated temperatures. As reported in sorghum starch, approximately 96% of amylose was released during sterilization at 120 °C compared to 88% at 100 °C [50]. Increased amylose availability promotes retrogradation and RS3 formation during subsequent cooling. However, sterilization at excessively high temperatures (>115 °C) may negatively affect product quality and sensory attributes and, therefore, must be balanced with RS optimization.

Sterilization time also significantly influenced RS formation In IR504, RS increased from 11.055% at 10 min to 11.286% at 15 min (Figure 7). Likewise, RS rose from 8.903% to 9.167% in Huyet Rong and from 4.331% to 4.448% in MS2019 over the same time range. Previous studies on corn and rice starch have similarly reported increases in RS content with prolonged sterilization due to enhanced gelatinization and amylose release [51,52]. The stronger gelatinization at longer heating times facilitates amylose leaching, and these chains subsequently reassociate during cooling, thereby increasing RS3 formation [53]. Overall, sterilization at 115 °C for 15 min yielded the highest RS content across all three rice varieties and was, therefore, selected as the optimal condition for further experiments. After sterilization processing, the samples were cooled, dried, milled, and analyzed for RS content.

Figure 7.

Effect of sterilization on resistant starch content in prebiotics instant rice Acacia products (IR504, Huyet Rong, MS2019). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of 3 replicates. Different letters within the same column indicate statistically significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

To optimize the sterilization of macaroni rice, the Fo value is key. It indicates the time (in min) needed at 121 °C to achieve equivalent microbial inactivation. A minimum Fo of 3 min ensures a 12D reduction in Clostridium botulinum spores [54]. Microbiological and mycotoxin assessments further demonstrated that all parameters were below the respective limits of detection (LOD), thereby confirming full compliance with food safety regulations. Moreover, stringent control of water activity (Aw)—0.87 for IR504, 0.86 for Huyet Rong, and 0.85 for MS2019—combined with optimized thermal processing, was identified as a critical factor in maintaining microbial stability and ensuring the overall safety of the resistant-starch-enriched instant rice macaroni.

Bacillus cereus (<10 CFU/g; ISO 7932:2004), Clostridium botulinum (absent in 2 g; AOAC 977.26), and Clostridium perfringens (<1.1 CFU/g; ISO 7937:2004) were undetected. Coliforms and Escherichia coli were also absent in 1 g (LOD: 1 CFU/g; ISO 4832:2007 and ISO 16649-2:2001), as were Staphylococcus aureus (<10 CFU/g; ISO 6888-1:2001) and Salmonella spp. in 25 g (ISO 6579-1:2017). Total yeast and mold (<10 CFU/g; ISO 21527-2:2008) and aerobic microorganisms (<1 CFU/g; ISO 4833-1:2013) were undetectable. No aflatoxins (B1, B2, G1, G2) were found (LOD: 0.5 µg/kg; NIFC. 04. M. 038 with LC-MS/MS).

Fungal and general microbial loads were similarly negligible, with total yeast and mold counts below the LOD of 10 CFU/g (ISO 21527-2:2008), and total aerobic microorganisms were undetectable at a LOD of 1 CFU/g (ISO 4833-1:2013). Additionally, no aflatoxins (B1, B2, G1, or G2) were detected in the product, with a combined LOD of 0.5 µg/kg, as determined using the NIFC.04.M.038 method with LC-MS/MS.

These findings confirm that strict hygiene protocols effectively prevent microbiological and mycotoxin contamination, demonstrating the facility’s robust quality management system and ensuring product safety. Thus, we can evaluate the quality of prebiotic instant rice macaroni products.

3.5.1. Nutritional Ingredients

Prebiotic macaroni exhibited a nutritional profile comparable to that of conventional rice macaroni but contained markedly higher RS content, ranging from 3- to 5-fold increases (11.64 g/100 g in IR504, 9.47 g in Huyet Rong, and 4.57 g in MS2019). These levels exceed the average daily RS intake in the US (3–8 g/day) and approach that of the Chinese population (14.9 g/day), suggesting that the product provides RS at or above commonly recommended dietary levels [55]. Therefore, the results presented in Table 2 demonstrate that the prebiotic macaroni formulations successfully meet functional RS intake requirements.

Table 2.

Nutritional composition of the prebiotic macaroni products.

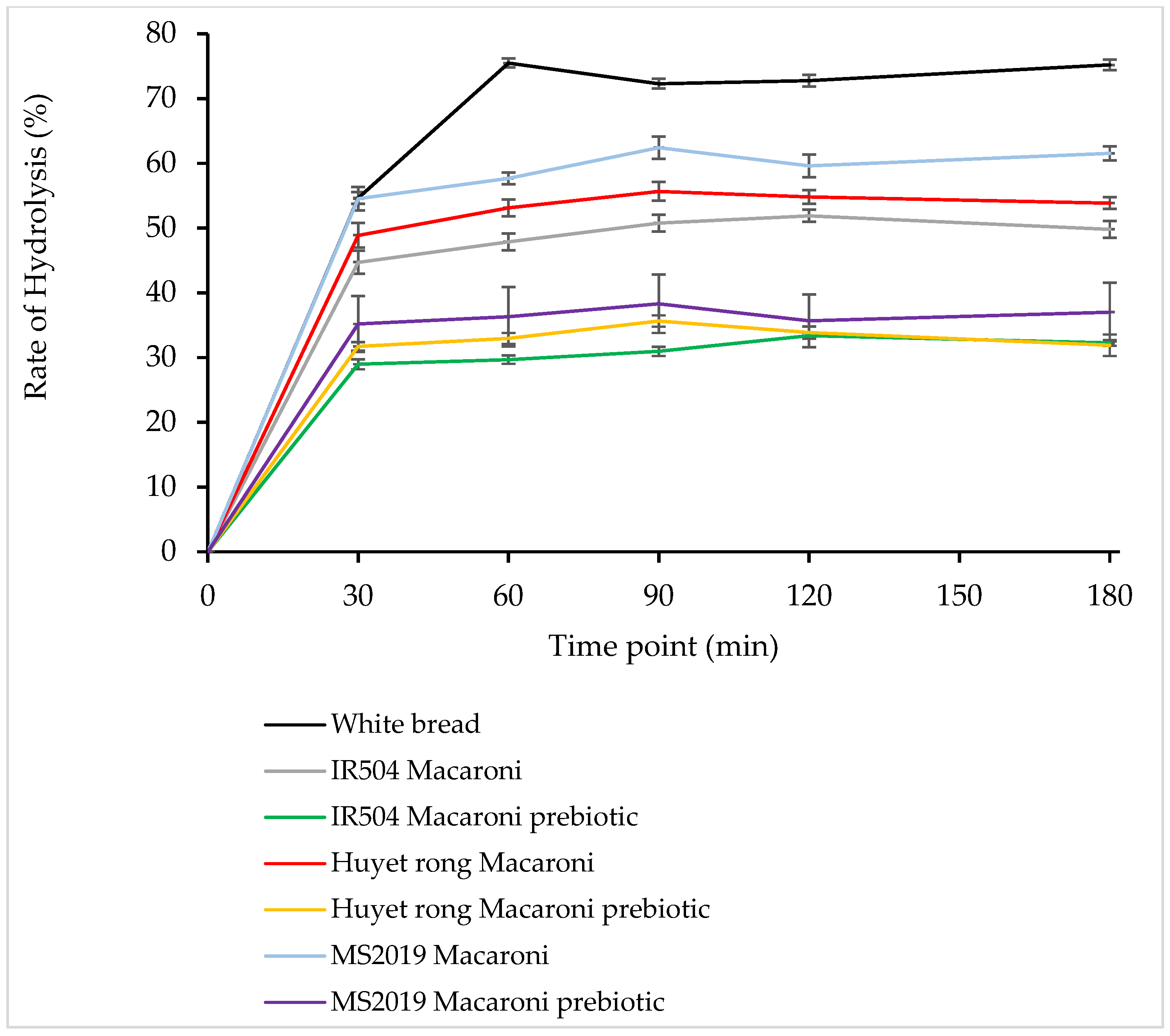

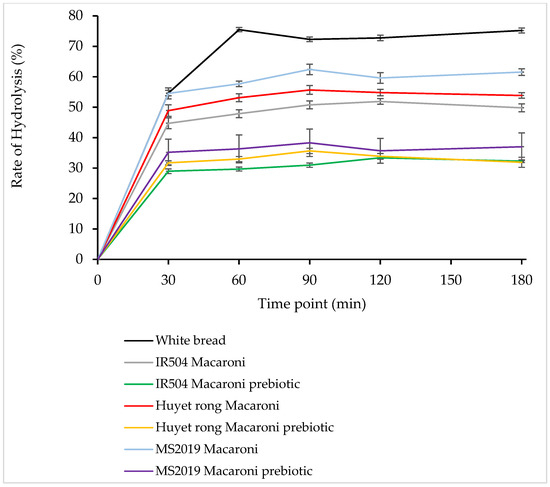

3.5.2. Effect of RS Content on Glycemic Index (GI)

According to Figure 8, most rice-flour-based products analyzed showed irregular patterns of starch hydrolysis, with increases and decreases varying depending on the specific sample type, notably, white bread 75.46% (at 60 min), MS 2019 macaroni 62.39% (at 90 min), Huyet Rong macaroni 58.65% (at 90 min), IR504 macaroni 51.88% (at 120 min), MS 2019 macaroni prebiotic 38.31% (at 90 min), Huyet Rong macaroni prebiotic 35.64% (at 90 min), and IR504 macaroni prebiotic 33.37% (at 120 min).

Figure 8.

Starch hydrolysis (%) of analyzed rice macaroni.

As illustrated in Figure 8, among the rice samples analyzed, the MS2019 variety exhibited the highest rate of starch hydrolysis following the white bread reference. This was followed by the Huyet Rong variety, whereas the IR504 variety showed the lowest hydrolysis rate observed among the tested samples.

Rice-based products typically have a high glycemic index (GI), which varies by cultivar. Among the samples tested, MS2019 had the highest GI, followed by Huyet Rong, while IR504 showed the lowest GI, with white bread as the reference (Table 3). The enrichment of these products with resistant starch—recognized as a prebiotic—resulted in a statistically significant reduction in GI values (p < 0.05). This outcome highlights the critical role of amylose content in modulating glycemic response. Specifically, cultivars with higher amylose content tend to form greater amounts of resistant starch (RS), which is less susceptible to enzymatic digestion and, therefore, slows postprandial glucose absorption [56]. Collectively, these findings support the inverse relationship between amylose/resistant starch content and the glycemic index, suggesting that targeted enhancement of resistant starch in rice-based products may offer a viable strategy for managing glycemic response.

Table 3.

Model parameters, area under starch hydrolysis over time curve (AUC), hydrolysis index (HI), and estimated glycemic index (GI) of the macaroni (IR504, Huyet Rong, MS2019) and white bread.

3.5.3. Color Measurement Results

The macaroni samples were cooled to room temperature after sterilization. The prepared samples were measured by placing them flat and precisely onto the instrument’s measuring port. The color characteristics of the product were evaluated using the CIE L*, a*, and b* color parameters, with whiteness (WI) also calculated. As shown in Table 4, the negative a* value indicates a slight greenish hue, while the positive b* value reflects a yellow tint. These color attributes suggest that the inclusion of resistant starch (RS) in the formulation contributes to the product’s subtle yellow appearance.

Table 4.

Color measurement results in rice macaroni.

The prebiotic instant macaroni showed lower lightness (L*) and a lower whiteness index (WI) but higher yellowness (b*) compared to conventional macaroni, while a* values were similar. These differences suggest that resistant starch incorporation leads to a darker, yellower product, likely due to the color of RS-rich ingredients and Maillard reactions during processing.

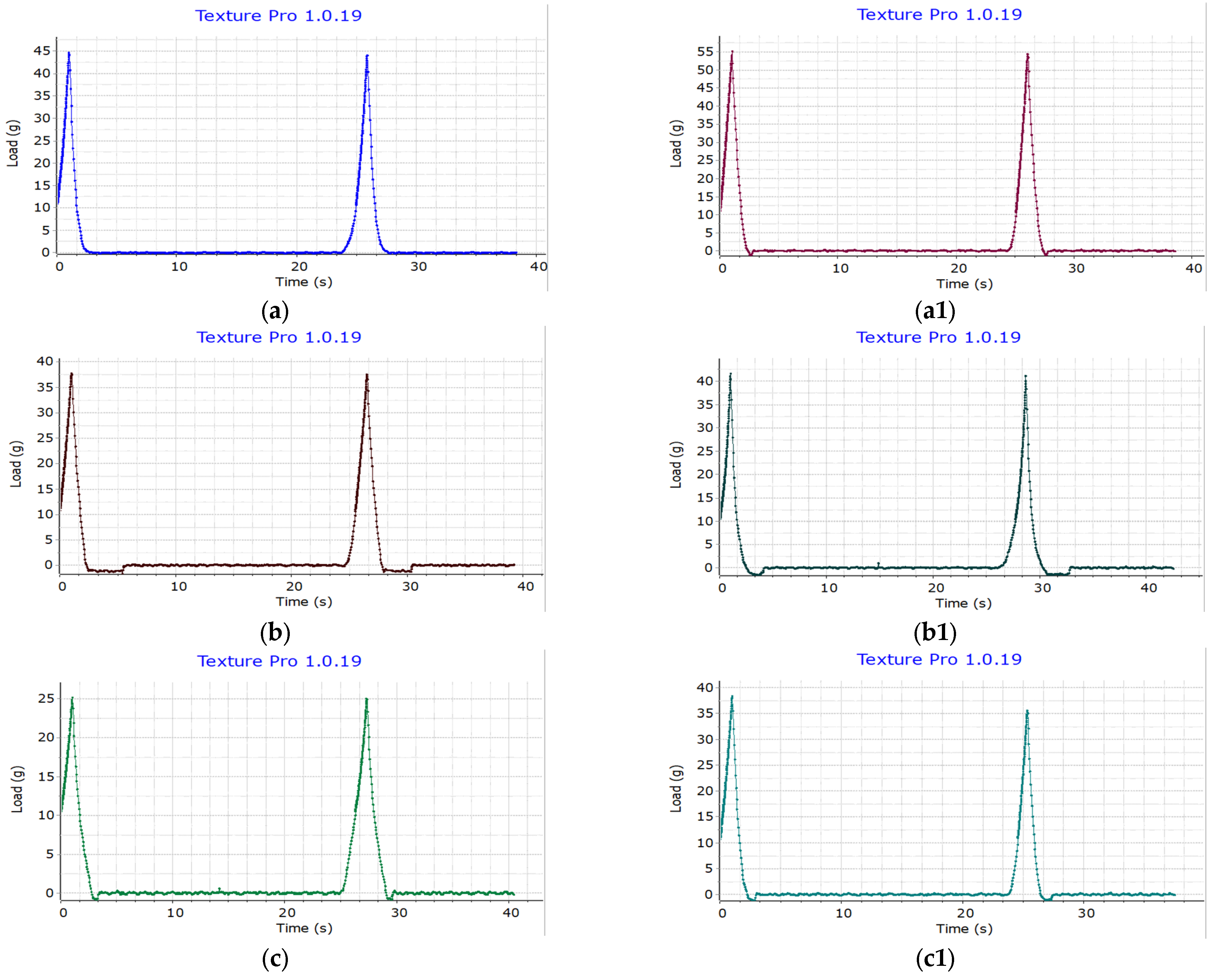

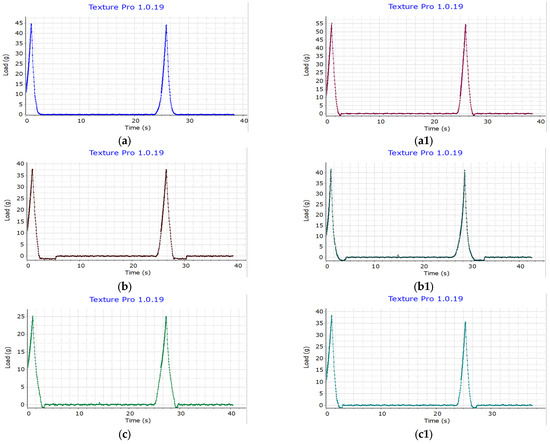

3.5.4. Hardness Measurement Results

The hardness analysis results (Figure 9) reveal variations in hardness between the prebiotic instant rice macaroni samples and the control rice macaroni samples under repeated measurements. For IR504 macaroni (a), the hardness is 44.70 g, while the hardness of its prebiotic rice macaroni counterpart (a1) increased to 55.10 g. Similarly, Huyet Rong macaroni (b) and Huyet Rong macaroni prebiotic (b1) showed hardness values of 37.70 g and 41.60 g, respectively. MS2019 (c) hardness was 25.10 g, and MS2019 prebiotic (c1) hardness was 38.30 g. Prebiotic rice macaroni with higher resistant starch content showed increased hardness across all rice cultivars. IR504-based macaroni had the highest hardness, followed by Huyet Rong and MS2019, reflecting their respective RS levels. These results suggest a positive correlation between resistant starch content and product structural strength [57].

Figure 9.

Hardness of IR504 macaroni (a), Huyet Rong macaroni (b), MS2019 macaroni (c), IR504 macaroni prebiotic (a1), Huyet Rong macaroni prebiotic (b1), MS2019 macaroni prebiotic (c1).

4. Conclusions

This study focused on the development of food products with high resistant starch (RS) content, using three different rice flour varieties: IR504, Huyet Rong, and MS2019. Each variety utilized RS rice flour combined with other ingredients such as wheat flour, tapioca starch, salt, and vegetable oil. The dough for each variety had a moisture content of 36–38%, and the products underwent a series of treatments, including gelatinization, microwave heating, retrogradation, and sterilization. The final RS content varied across the three varieties: 11.64% for IR504 macaroni prebiotic, which reduced the estimated glycemic index (eGI) by 17.98% compared to the control IR504 macaroni sample; 9.47% for Huyet Rong macaroni prebiotic, which showed a 19.31% reduction in eGI compared to the Huyet Rong macaroni sample; and 4.57% for MS2019 macaroni prebiotic, which resulted in a 20.69% reduction in eGI compared to the MS2019 macaroni sample. The study concluded that adding RS rice starch to pasta formulations increased the RS content, and physical methods further enriched it. This research provides insights into formulating RS-rich food products and lays the groundwork for future studies on the nutritional benefits of RS rice starch. Future studies should include in vivo clinical trials to confirm glycemic control, as well as shelf-life stability studies, to evaluate product quality and RS retention during storage.

Author Contributions

A.H.N.: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; P.T.N.: conceptualization, methodology; T.T.P.: software, validation, formal analysis; U.H.L.: writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; D.D.N.L.: visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Data Availability Statement

All the data is available within this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ho Chi Minh City University of Industry and Trade, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, which provided the facilities required to carry out this work. We acknowledge Nguyen Tat Thanh University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, for supporting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Giacco, R.; Vitale, M.; Riccardi, G. Pasta: Role in Diet. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, A.; Pagani, M.A.; Marti, A. Pasta-Making Process: A Narrative Review on the Relation between Process Variables and Pasta Quality. Foods 2022, 11, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, V.; Boccacci Mariani, M.; Marini, F.; Biancolillo, A. Effects of thermal treatments on durum wheat pasta flavour during production process: A modelling approach to provide added-value to pasta dried at low temperatures. Talanta 2021, 225, 121955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dello Russo, M.; Spagnuolo, C.; Moccia, S.; Angelino, D.; Pellegrini, N.; Martini, D. Nutritional quality of pasta sold on the italian market: The food labelling of italian products (FLIP) study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelino, D.; Martina, A.; Rosi, A.; Veronesi, L.; Antonini, M.; Mennella, I.; Vitaglione, P.; Grioni, S.; Brighenti, F.; Zavaroni, I.; et al. Glucose- and Lipid-Related Biomarkers Are Affected in Healthy Obese or Hyperglycemic Adults Consuming a Whole-Grain Pasta Enriched in Prebiotics and Probiotics: A 12-Week Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1714–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciccoritti, R.; Taddei, F.; Nicoletti, I.; Gazza, L.; Corradini, D.; D’Egidio, M.G.; Martini, D. Use of bran fractions and debranned kernels for the development of pasta with high nutritional and healthy potential. Food Chem. 2017, 225, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliviero, T.; Fogliano, V. Food design strategies to increase vegetable intake: The case of vegetable enriched pasta. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Jiang, H.; Sang, S.; McClements, D.J.; Jiang, L.; Wen, J.; Jin, Z.; Qiu, C. Research advances in origin, applications, and interactions of resistant starch: Utilization for creation of healthier functional food products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 148, 104519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Sun, Y. Influencing factor of resistant starch formation and application in cereal products: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, J.H.; Liu, Q.; Yada, R.Y. Methodologies for Increasing the Resistant Starch Content of Food Starches: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 1219–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englyst, H.N.; Kingman, S.M.; Cummings, J.H. Classification and measurement of nutritionally important starch fractions. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1992, 46, S33–S50. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1330528 (accessed on 1 October 1992).

- Ellis, R.P.; Cochrane, M.P.; Dale, M.F.B.; Duffus, C.M.; Lynn, A.; Morrison, I.M.; Prentice, R.D.M.; Swanston, J.S.; Tiller, S.A. Starch production and industrial use. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998, 77, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojarczuk, A.; Skąpska, S.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Marszałek, K. Health benefits of resistant starch: A review of the literature. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 93, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-S.; Chung, H.-J. Enhancing Resistant Starch Content of High Amylose Rice Starch through Heat–Moisture Treatment for Industrial Application. Molecules 2022, 27, 6375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Rosa Zavareze, E.; Mello El Halal, S.L.; de los Santos, D.G.; Helbig, E.; Pereira, J.M.; Guerra Dias, A.R. Resistant starch and thermal, morphological and textural properties of heat-moisture treated rice starches with high-, medium- and low-amylose content. Starch 2012, 64, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hung, P.; Binh, V.T.; Nhi, P.H.Y.; Phi, N.T.L. Effect of heat-moisture treatment of unpolished red rice on its starch properties and in vitro and in vivo digestibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, D.; Sit, N. Dual modification of taro starch by microwave and other heat moisture treatments. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 92, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denchai, N.; Suwannaporn, P.; Lin, J.; Soontaranon, S.; Kiatponglarp, W.; Huang, T. Retrogradation and Digestibility of Rice Starch Gels: The Joint Effect of Degree of Gelatinization and Storage. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Ma, S.; Ma, W.; Liu, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H. Effect of microwave on lamellar parameters of rice starch through small-angle X-ray scattering. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 35, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwannaporn, P.; Pitiphunpong, S.; Champangern, S. Classification of Rice Amylose Content by Discriminant Analysis of Physicochemical Properties. Starch 2007, 59, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuy, N.M.; Van Tai, N. Effect of different cooking conditions on resistant starch and estimated glycemic index of macaroni. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ouyang, J. Effect of microwave irradiation-retrogradation treatment on the digestive and physicochemical properties of starches with different crystallinity. Food Chem. 2019, 298, 125015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górecki, A.R.; Błaszczak, W.; Lewandowicz, J.; Le Thanh-Blicharz, J.; Penkacik, K. Influence of High Pressure or Autoclaving-Cooling Cycles and Pullulanase Treatment on Buckwheat Starch Properties and Resistant Starch Formation. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2018, 68, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.D.; Xu, T.C.; Xiao, J.X.; Zong, A.Z.; Qiu, B.; Jia, M.; Liu, L.N.; Liu, W. Efficacy of potato resistant starch prepared by microwave–toughening treatment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 192, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Kuang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Sun, X. Materials Today Nano Microwave chemistry, recent advancements, and eco-friendly microwave-assisted synthesis of nanoarchitectures and their applications: A review. Mater. Today Nano 2020, 11, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, W.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, S.; Du, H. Structure and Physicochemical Properties of Resistant Starch Prepared by Autoclaving-Microwave. Starch 2018, 70, 1800060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, V.J. Starch gelation and retrogradation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1990, 1, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, Q.H.; Hoàng, T.M.; Tuyên, A.D.; Vu, T.T.; Luong, N.H. Effect of some factors on the hydrolysis process of sweet potato starch by spezyme alpha to produce isomaltooligosaccharide (IMO). Vietnam J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 60, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, R.; Hughes, T.; Chung, H.J.; Liu, Q. Composition, molecular structure, properties, and modification of pulse starches: A review. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Hwang, C.-C.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Huang, Y.-T. Development and pasteurization of in-packaged ready-to-eat rice products prepared with novel microwave-assisted induction heating (MAIH) technology. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, K.; Yu, W.; Prakash, S.; Gilbert, R.G. Investigating cooked rice textural properties by instrumental measurements. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2020, 9, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulung, N.K.; Aziss, N.A.S.M.; Kutbi, N.F.; Ahadaali, A.A.; Zairi, N.A.; Mahmod, I.I.; Sajak, A.A.B.; Sultana, S.; Azlan, A. Validation of in vitro glycaemic index (eGI) and glycaemic load (eGL) based on selected baked products, beverages, and canned foods. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 3, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Too, B.C.; Thuy, N.M. Effect of partial replacement of wheat flour with flour/starch containing resistant starch on macaroni quality. Food Res. 2023, 7, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahariza, Z.A.; Sar, S.; Hasjim, J.; Tizzotti, M.J.; Gilbert, R.G. The importance of amylose and amylopectin fine structures for starch digestibility in cooked rice grains. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.J.; Liu, Q.Q.; Wilson, J.D.; Gu, M.H.; Shi, Y.C. Digestibility and physicochemical properties of rice (Oryza sativa L.) flours and starches differing in amylose content. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Monica Giusti, M. Anthocyanins: Natural colorants with health-promoting properties. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 1, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isra, M.; Andrianto, D.; Setiarto, R.H.B. Effect heat moisture treatment for resistant starch levels and prebiotic properties of high carbohydrate food: Meta-analysis study. Food Res. 2023, 7, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, K.L.; Brand-Miller, J.; Copeland, L. Glycemic effect of potatoes. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 1230–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarič, L.; Minarovičová, L.; Lauková, M.; Karovičová, J.; Kohajdová, Z. Pasta noodles enriched with sweet potato starch: Impact on quality parameters and resistant starch content. J. Texture Stud. 2020, 51, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, M.; Tang, A.; Jane, J.L.; Dhital, S.; Guo, B. RS Content and EGI value of cooked noodles (I): Effect of cooking methods. Foods 2020, 9, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juansang, J.; Puttanlek, C.; Rungsardthong, V.; Puncha-Arnon, S.; Uttapap, D. Effect of gelatinisation on slowly digestible starch and resistant starch of heat-moisture treated and chemically modified canna starches. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Chen, B.; Zeng, H.; Guo, Z.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, B. Effect of Microwave Irradiation on the Physicochemical and Digestive Properties of Lotus Seed Starch. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 2442–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, F.; Liu, F.; Wang, Z.W. Study on structural changes of microwave heat-moisture treated resistant Canna edulis Ker starch during digestion in vitro. Food Hydrocoll. 2010, 24, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, S.; Kahraman, K.; Öztürk, S. Optimization of resistant starch formation from high amylose corn starch by microwave irradiation treatments and characterization of starch preparations. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 95, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, O.; Guerreiro, C.S.; Gomes, A.; Cravo, M. Resistant starch production in wheat bread: Effect of ingredients, baking conditions and storage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2016, 242, 1747–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Escobedo, R.; Osorio-Díaz, P.; García-Rosas, M.I.; Bello-Pérez, A.; Hernández-Unzón, H. Changes in selected nutrients and microstructure of white starch quality maize and common maize during tortilla preparation and storage. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2004, 10, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borczak, B.; Sikora, E.; Sikora, M.; Kapusta-Duch, J. The influence of prolonged frozen storage of wheat-flour rolls on resistant starch development. Starch 2014, 66, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwongchai, W.; Sa-ingthong, N.; Phothiset, S.; Saenubon, C.; Thitisaksakul, M. Resistant starch formation and changes in physicochemical properties of waxy and non-waxy rice starches by autoclaving-cooling treatment. Int. J. Food Prop. 2024, 27, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, C.S. Resistant starch: Formation and measurement of starch that survives exhaustive digestion with amylolytic enzymes during the determination of dietary fibre. J. Cereal Sci. 1986, 4, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Du, X.; Chen, P.; Guo, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, X. Morphologies and gelatinization behaviours of high-amylose maize starches during heat treatment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milasinovic, M.; Radosavljevic, M.; Dokic, L. Effects of autoclaving and pullulanase debranching on the resistant starch yield of normal maize starch. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2010, 75, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Huang, M.; Li, B.; Zhou, B. The effect of three gums on the retrogradation of indica rice starch. Nutrients 2012, 4, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, P.C.-K.; Chau, C.-F. Changes in the Dietary Fiber (Resistant Starch and Nonstarch Polysaccharides) Content of Cooked Flours Prepared from Three Chinese Indigenous Legume Seeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Park, J.; Kim, D.; Kim, D. Resistant starch and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Clinical perspective. J. Diabetes Investig. 2024, 15, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Hu, X.; Boye, J.I. Research advances on the formation mechanism of resistant starch type III : A review Research advances on the formation mechanism of resistant starch type III: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 60, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasoveanu, M.; Nemtanu, M.R. Behaviour of starch exposed to microwave radiation treatment. Starch 2014, 66, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birt, D.F.; Boylston, T.; Hendrich, S.; Jane, J.-L.; Hollis, J.; Li, L.; McClelland, J.; Moore, S.; Phillips, G.J.; Rowling, M.; et al. Resistant Starch: Promise for Improving Human Health. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).