Scaling Up a Heater System for Devulcanization of Off-Spec Latex Waste: A Two-Phase Feasibility Study

Abstract

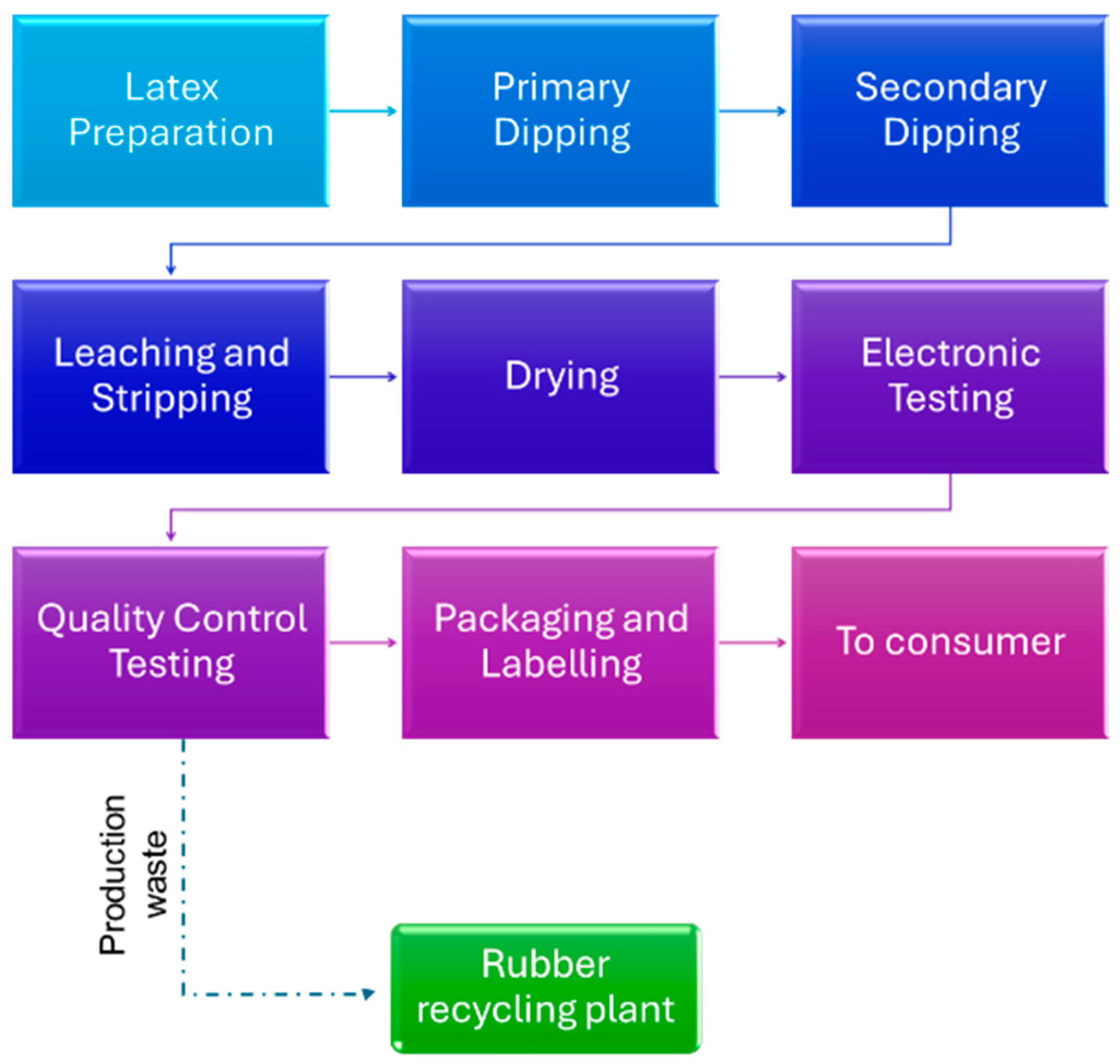

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Lab-Scale Testing

Devulcanization of Rubber in a Lab-Scale Setup

Scaled-Up Configuration of the Waste Rubber Machine for Rubber Devulcanization

2.2.2. Devulcanization of Rubber in Modified-Waste Rubber Machine

Characterization

- Gel content analysis

- b.

- Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

- c.

- Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA)

- d.

- Gel permeation chromatography (GPC)

- e.

- Dispersity (Ð)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Laboratory-Scale Devulcanization

3.1.1. Effect of Temperature on Devulcanization Process

3.1.2. Effect of Time on Devulcanization Process

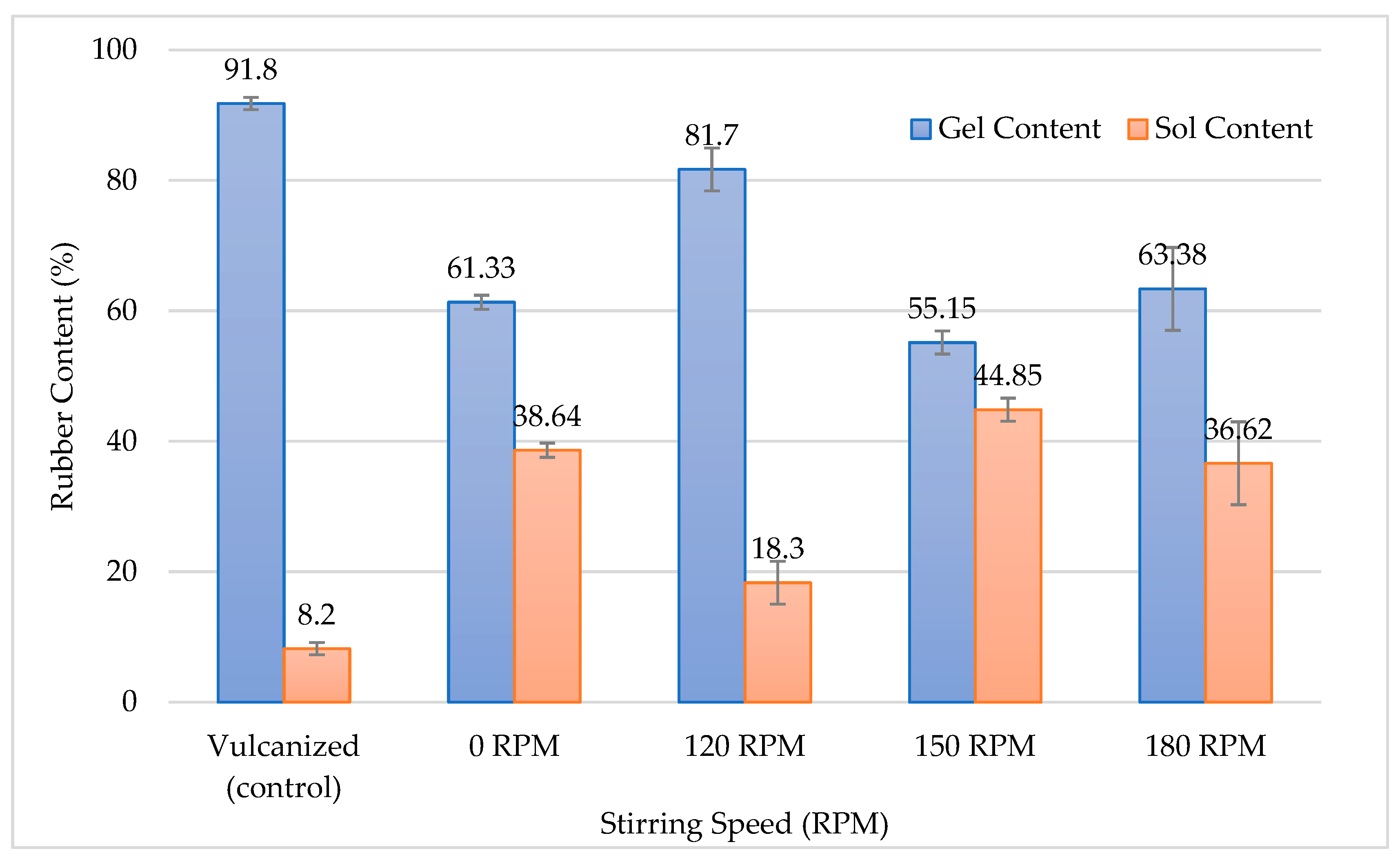

3.2. Pilot-Scale Devulcanization: Modification of Waste Rubber Tank

3.2.1. Physical Appearance

3.2.2. Gel and Sol Content Analysis

3.2.3. Thermal Analysis

3.2.4. Molecular Weight Distribution

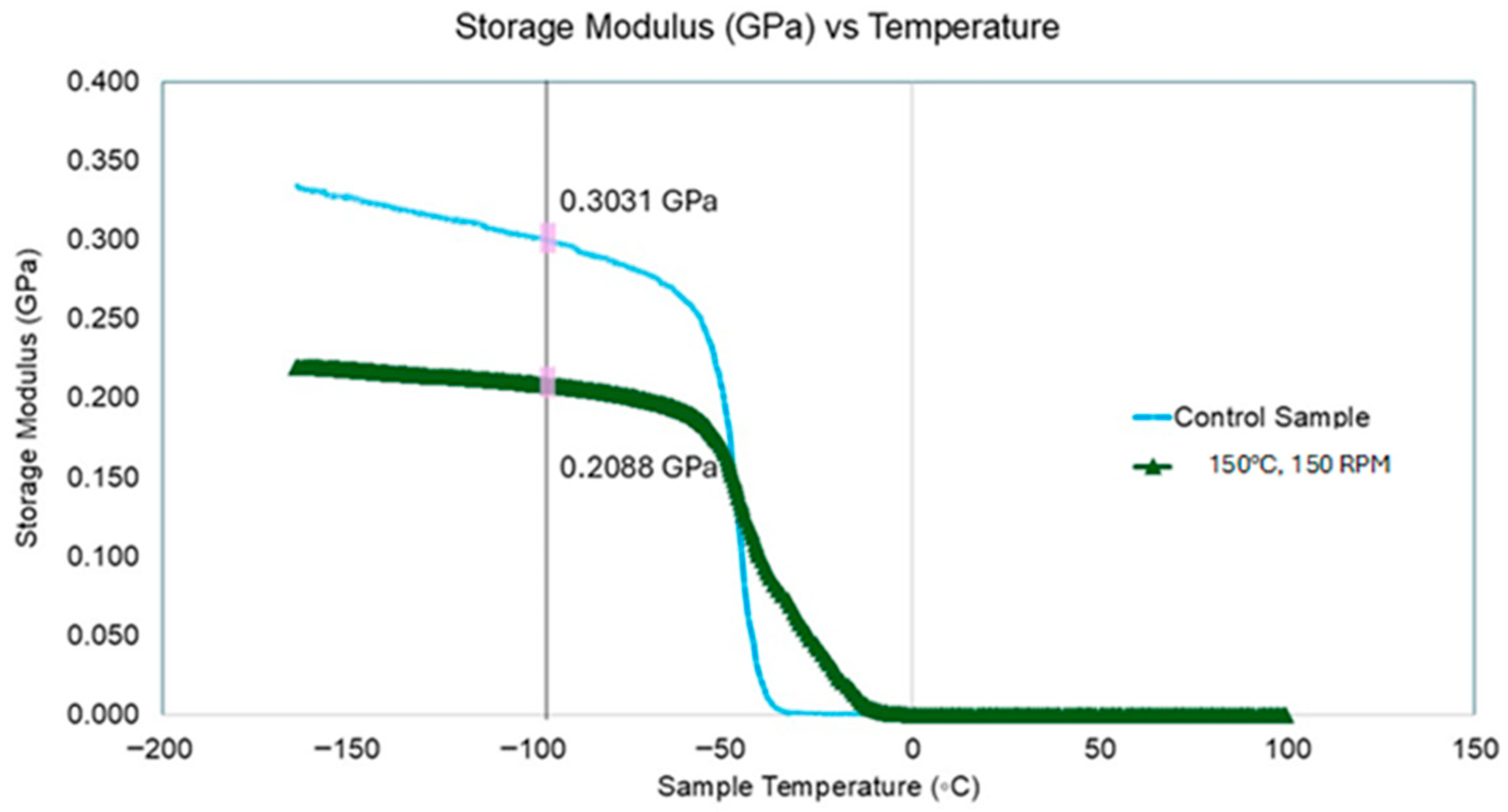

3.2.5. Dynamics Mechanical Properties of Devulcanized Rubber

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NR | Natural rubber |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| GPC | Gel permeation chromatography |

| DMA | Dynamic mechanical analysis |

| D | Dispersity |

| DTG | Derivative thermogravimetry |

References

- Umeswara, S.S. Towards a Circular Economy Waste Management in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the MEA 12MP Kick-Off Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1–4 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Growth Within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competitive Europe. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/growth-within-a-circular-economy-vision-for-a-competitive-europe (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Tono, T.; Nakazawa, Y.; Sato, K.; Hashimoto, M.; Aizawa, M.; Ikeda-Fukazawa, T. Effects of thermal history of silica composite polyisoprene rubber on structure of contact water. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2024, 847, 141373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaysian Rubber Council. World Rubber Production, Consumption and Trade. Available online: https://www.myrubbercouncil.com/industry/world_production.php (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Jawjit, W.; Pavasant, P.; Kroeze, C.; Tuffey, J. Evaluation of the potential environmental impacts of condom production in Thailand. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2021, 18, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markl, E.; Lackner, M. Devulcanization technologies for recycling of tire-derived rubber: A review. Materials 2020, 13, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, J. Dynamic pyrolysis behaviors, products, and mechanisms of waste rubber and polyurethane bicycle tires. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 123516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maga, D.; Aryan, V.; Blömer, J. A comparative life cycle assessment of tyre recycling using pyrolysis compared to conventional end-of-life pathways. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 199, 107255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunella, V.; Aresti, V.; Romagnolli, U.; Muscato, B.; Girotto, M.; Rizzi, P.; Luda, M.P. Recycling of EPDM via Continuous Thermo-Mechanical Devulcanization with Co-Rotating Twin-Screw Extruder. Polymers 2022, 14, 4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.Á.; Bárány, T. Microwave Devulcanization of Ground Tire Rubber and Its Improved Utilization in Natural Rubber Compounds. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 1797–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, S.; Linforth, S.; Kashani, A.; Liu, X.; Ngo, T. Effect of recycled rubber aggregate size on fracture and other mechanical properties of structural concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceretti, D.V.A.; Edeleva, M.; Cardon, L.; D’hooge, D.R. Molecular Pathways for Polymer Degradation during Conventional Processing, Additive Manufacturing, and Mechanical Recycling. Molecules 2023, 28, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candau, N.; Leblanc, R.; Maspoch, M.L. A comparison of the mechanical behaviour of natural rubber-based blends using waste rubber particles obtained by cryogrinding and high-shear mixing. Express Polym. Lett. 2023, 17, 1135–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzyka, R.; Mumtaz, H.; Sobek, S.; Werle, S.; Adamek, J.; Semitekolos, D.; Charitidis, C.A.; Tiriakidou, T.; Sajdak, M. Solvolysis and oxidative liquefaction of the end-of-life composite wastes as an element of the circular economy assumptions. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 478, 143916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evergreen Corporate Sdn Bhd. Evergreen Corporate Making the World a Better Place. Available online: https://www.evergreencorporate.com/ (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Xiao, Z.; Pramanik, A.; Basak, A.K.; Prakash, C.; Shankar, S. Material recovery and recycling of waste tyres—A review. Clean. Mater. 2022, 3, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wang, C.; Lv, D.; Ren, D.; Zhai, T.; Sun, C.; Liu, H. Rubber reclamation with high bond-breaking selectivity using a low-temperature mechano-chemical devulcanization method. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirityi, D.Z.; Bárány, T.; Pölöskei, K. Recycling of EPDM rubber via thermomechanical devulcanization: Batch and continuous operations. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 230, 111014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschwind, L.; Jordan, C.S.; Vennemann, N. Devulcanization of ethylene-propylene-diene monomer rubber waste. Effect of diphenyl disulfide derivate as devulcanizing agent on vulcanization, and devulcanization process. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 52141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, F. Thermochemistry of Sulfur-Based Vulcanization and of Devulcanized and Recycled Natural Rubber Compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 32623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, M.; Jamshidi, M. Recycling NR/SBR waste using probe sonication as a new devulcanizing method; study on influencing parameters. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 26264–26276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamarpoor, R.; Jamshidi, M. Synergistic effect of microwave assisted devulcanization of waste NBR rubber and using superhydrophobic/superoleophilic silica nanoparticles on oil-water separation. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 69, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, N.; Sheng, Z.; Qin, L.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, J. Devulcanization of ground tire rubber using a plasma-assisted fluidized-bed system. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 684, 161784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghowsi, M.A.; Jamshidi, M. Recycling waste nitrile rubber (NBR) and improving mechanical properties of Re-vulcanized rubber by an efficient chemo-mechanical devulcanization. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2023, 6, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costamagna, M.; Brunella, V.; Luda, M.P.; Romagnolli, U.; Muscato, B.; Girotto, M.; Baricco, M.; Rizzi, P. Environmental assessment of rubber recycling through an innovative thermo-mechanical devulcanization process using a co-rotating twin-screw extruder. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 348, 131352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom, X.; Cañavate, J.; Formela, K.; Shadman, A.; Saeb, M.R. Assessment of the devulcanization process of EPDM waste from roofing systems by combined thermomechanical/microwave procedures. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2021, 183, 109450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SSH Recycling. Available online: https://sshrecyclingltd.org.uk/our-process/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Tyromer Inc. Technology Rubber Devulcanization. Available online: https://tyromer.com/technology/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Asaro, L.; Gratton, M.; Poirot, N.; Seghar, S.; Hocine, N.A. Devulcanization of natural rubber industry waste in supercritical carbon dioxide combined with diphenyl disulfide. Waste Manag. 2020, 118, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiwari, S.; Nobnop, S.; Bueraheng, Y.; Thitithammawong, A.; Hayeemasae, N.; Salaeh, S. Segregated MWCNT Structure Formation in Conductive Rubber Nanocomposites by Circular Recycling of Rubber Waste. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 7463–7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3616-95(2024); Standard Test Method for Rubber—Determination of Gel, Swelling Index, and Dilute Solution Viscosity. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- Ge, M.; Zheng, G. Fluid–Solid Mixing Transfer Mechanism and Flow Patterns of the Double-Layered Impeller Stirring Tank by the CFD-DEM Method. Energies 2024, 17, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walvekar, R.; Afiq, Z.M.; Ramarad, S.; Khalid, S. Devulcanization of Waste Tire Rubber Using Amine Based Solvents and Ultrasonic Energy. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 152, 01007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Country | Production of Natural Rubber in 2024 (Million Tons) |

|---|---|

| Thailand | 5.02 |

| Indonesia | 2 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 1.8 |

| Vietnam | 1.3 |

| China | 0.88 |

| India | 0.88 |

| Cambodia | 0.53 |

| Malaysia | 0.39 |

| Laos | 0.35 |

| Myanmar | 0.33 |

| Rubber Reclaiming Process | Details | Advantages | Disadvantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrolysis | Convert rubber waste into smaller molecular mass products under high temperatures and a low-oxygen environment | Reduce landfill storage, obtain high-quality products of pyrolysis oil, carbon black, gas for electricity generation, and metal cord for the metallurgical industry. | High energy usage | [7,8] |

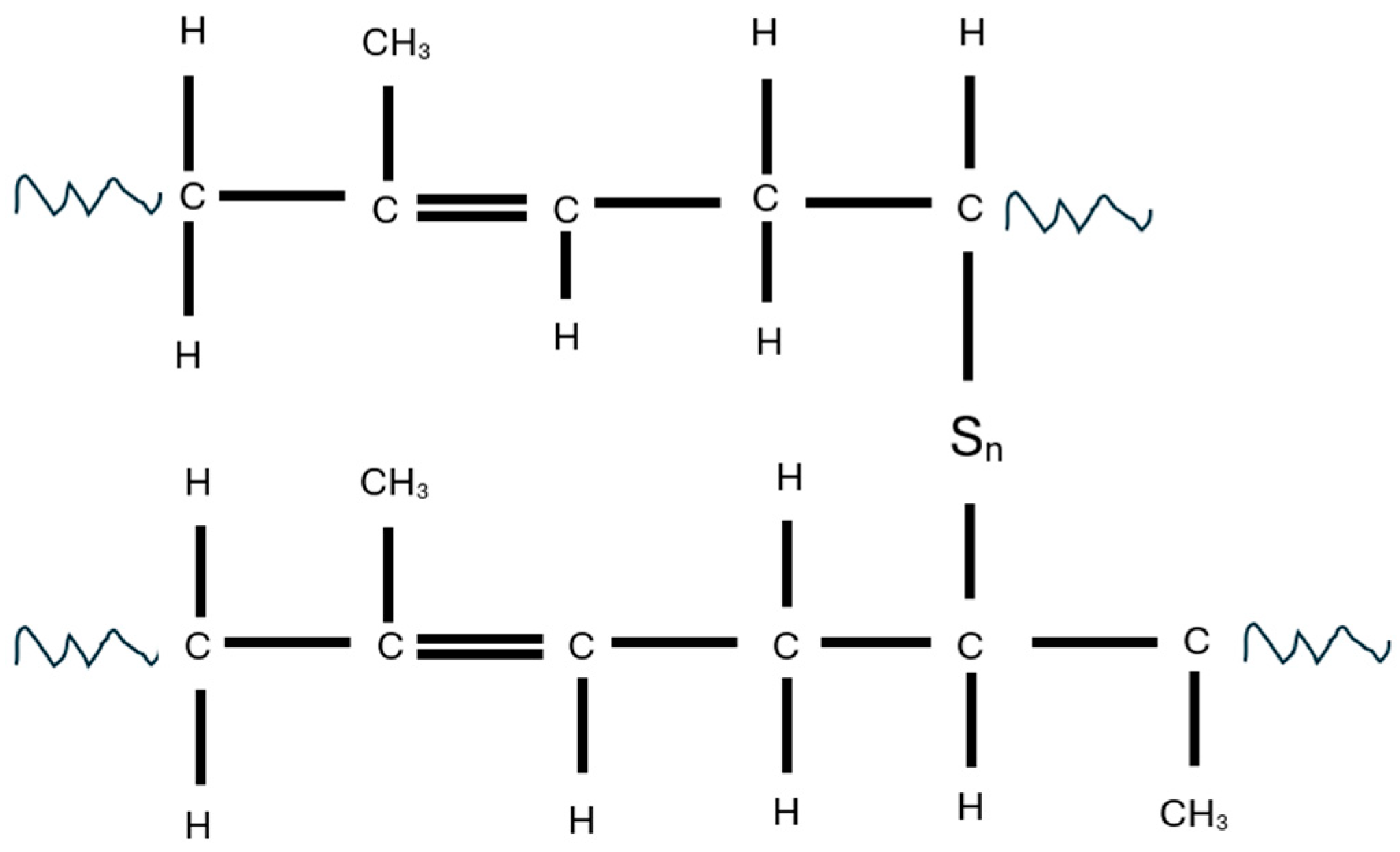

| Devulcanization | Breaking the sulfur crosslinks in vulcanized rubber | Process using heat, chemical agents, and mechanical shears to produce devulcanized rubber, which retains its natural properties of rubber | Process may break the main C-C polymer in addition to breaking the sulfur crosslinks, which will weaken the mechanical properties of devulcanized rubber | [9,10] |

| Mechanical recycling | Using mechanical processes such as grinding and shredding to produce smaller particles of rubber | Cost-effective components such as steel wires, textile fibers recovery, versatility of end products | Degradation of mechanical properties and inconsistent product quality | [11,12,13,14] |

| Devulcanization Process | Details | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical |

| [17] |

| Thermal |

| [18] |

| Chemical |

| [19,20] |

| Ultrasonication |

| [21] |

| Microwave-assisted |

| [22] |

| Combination of methods |

| [23,24,25,26] |

| Sample | Temperature (°C) | Time (Minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 30 |

| 2 | 150 | 30 |

| 3 | 200 | 30 |

| 4 | 250 | 30 |

| 5 | 150 | 10 |

| 6 | 150 | 20 |

| 7 | 200 | 10 |

| 8 | 200 | 20 |

| Run | T (°C) | Speed (RPM) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 130 | 120 |

| 2 | 130 | 150 |

| 3 | 130 | 180 |

| 4 | 140 | 120 |

| 5 | 140 | 150 |

| 6 | 140 | 180 |

| 7 | 150 | 120 |

| 8 | 150 | 150 |

| 9 | 150 | 180 |

| Temperature (°C) | Time (Minute) | Gel Content (%) | Sol Content (%) | Onset Degradation Temperature (°C) | Tmax (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 0 | 84.09 ± 1.3 | 15.91 ± 1.3 | 345.0 | 377.17 |

| 100 | 30 | 79.36 ± 8.4 | 20.64 ± 8.41 | 339.11 | 375.33 |

| 150 | 58.43 ± 6.2 | 41.57 ± 6.2 | 340.31 | 377.33 | |

| 200 | 0.91 ± 3.7 | 99.09 ± 3.7 | 339.53 | 377.17 | |

| 250 | 0.37 ± 2.2 | 99.63 ± 2.2 | 339.10 | 376.33 |

| Temperature (°C) | Time (Minute) | Gel Content (%) | Sol Content (%) | Tmax (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 150 | 10 | 87.36 ± 2.2 | 12.64 ± 2.2 | 376.83 |

| 20 | 52.15 ± 2.2 | 47.85 ± 2.2 | 375.17 | |

| 30 | 58.43 ± 6.2 | 41.57 ± 6.2 | 377.33 | |

| 200 | 10 | 26.59 ± 7.0 | 73.41 ± 7.0 | 376.50 |

| 20 | 3.53 ± 1.4 | 96.47 ± 1.4 | 376.67 | |

| 30 | 0.91 ± 3.7 | 99.09 ± 3.7 | 377.17 |

| Sample | Temperature | Speed (RPM) | Tmax (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vulcanized (Control) | 25 | 0 | 375.8 |

| Pre-modification | 150 | 0 | 376.8 |

| Post-modification | 150 | 150 | 374.3 |

| Sample | Mn | Mw | Ð |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 6850 | 13,460 | 1.97 |

| Lab scale: 150 °C, 20 min | 7240 | 16,420 | 2.27 |

| Pilot plant: 150 °C, 150 RPM | 62,440 | 109,900 | 1.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alias, D.; Ramarad, S.; Ng, L.Y.; Andiappan, V.; Low, J.B.C.; Leng, F.P.; Leam, J.J.; Ng, D.K.S. Scaling Up a Heater System for Devulcanization of Off-Spec Latex Waste: A Two-Phase Feasibility Study. Processes 2025, 13, 4062. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124062

Alias D, Ramarad S, Ng LY, Andiappan V, Low JBC, Leng FP, Leam JJ, Ng DKS. Scaling Up a Heater System for Devulcanization of Off-Spec Latex Waste: A Two-Phase Feasibility Study. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4062. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124062

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlias, Dalila, Suganti Ramarad, Lik Yin Ng, Viknesh Andiappan, Jason B. C. Low, Fook Peng Leng, Jia Jia Leam, and Denny K. S. Ng. 2025. "Scaling Up a Heater System for Devulcanization of Off-Spec Latex Waste: A Two-Phase Feasibility Study" Processes 13, no. 12: 4062. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124062

APA StyleAlias, D., Ramarad, S., Ng, L. Y., Andiappan, V., Low, J. B. C., Leng, F. P., Leam, J. J., & Ng, D. K. S. (2025). Scaling Up a Heater System for Devulcanization of Off-Spec Latex Waste: A Two-Phase Feasibility Study. Processes, 13(12), 4062. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124062