Abstract

Resource-based cities generally have large carbon-emission, and their carbon balance status is receiving more attention. Land use is a key factor in regulating regional carbon balance. To explore the relationship between land use patterns and carbon balance in resource-based cities, we selected nine cities in Anhui, a major energy province, as the research object. Based on the land use data (2000–2020) and the carbon emission coefficient method, we calculated the carbon emissions, carbon sequestration, and net carbon emissions to show their spatiotemporal evolution. The Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) method was employed to explore the driving factors of carbon emissions. The results indicated the following: (1) Net carbon emissions increased by 149.60%, and the growth rate had slowed down since 2015. Forestland constituted the primary carbon sink, whereas cropland was the dominant carbon source. The spatial distribution of carbon emissions and carbon sequestration was uneven. (2) The economic development level and energy consumption density were the principal factors of emission increases. Conversely, carbon emission intensity and land use economic efficiency served as the key mitigating factors.

1. Introduction

Global warming has emerged as a significant challenge to global sustainable development. The goals of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality have charted the course for greenhouse gas emission reduction and have become a core component of China’s ecological civilization construction. Land, as the core carrier of economic and social activities, is also the main source of carbon emissions. The changes in the type and intensity of land use will have an impact on natural elements and human activities, thereby influencing the carbon cycle process. Mineral resource exploitation, production, and processing in resource-based cities may lead to significant changes in land use patterns, including surface subsidence, damage to cultivated land, occupation of ecological land, and the expansion of construction land. Furthermore, the processes of energy production and consumption also contribute to the increase in carbon emissions. These factors make resource-based cities key areas in the process of achieving carbon peaking and carbon neutrality. Anhui Province is the largest energy base in eastern China and a core area for undertaking industrial transfer from the Yangtze River Delta region. The land use of Anhui’s resource-based cities and the associated carbon emissions are under multiple pressures, such as resource exploitation, industrial scale expansion, and rapid urbanization.

Anhui is a crucial pillar in ensuring China’s energy supply, especially the energy security of the Yangtze River Delta region. Compared with some other major energy-producing provinces in China, the mineral industry in Anhui has its own characteristics. In terms of the types and output of mineral resources, the main energy resources of this province are coal. The total coal output in this province was 112 million tons, ranking 6th in China in 2023. Additionally, the production of metals such as iron and copper, as well as non-metallic minerals like sulfuric iron ore and limestone used for cement, is also very large. In terms of mineral resource transfer, the amount of coal transferred from Anhui accounts for approximately 40% of its production, mainly supplying the regions of Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shanghai. The amount of coal transferred from Shanxi Province is as high as 50–60%, and it is supplied to more than 25 provincial administrative regions in China. Although the coal production in the northeastern region of China is relatively large, it has long been below local consumption levels. This demonstrates the significant role of Anhui in providing energy to the Yangtze River Delta region. The data of 2023 show that the operating income of mining enterprises in Anhui Province accounted for 3.24% of the total operating income of all industrial enterprises. The corresponding figures of Liaoning, Heilongjiang, and Shanxi were 4.47%, 20.51% and 40.33%, respectively. In the same year, the proportion of employment in the mining industry of the total employment in Anhui Province was 2.16%, while the figures for Liaoning, Heilongjiang, and Shanxi were 3.60%, 7.92% and 19.77%, respectively. These, to some extent, indicate that the reliance on the mining industry of Anhui Province is relatively low. At present, Anhui Province is in an important stage of energy structure transformation to green and low-carbon. And it is vigorously promoting the construction of new energy projects such as photovoltaic and wind power. Meanwhile, due to the requirements of the regional integration development strategy of China, Anhui Province has become the main region for undertaking industrial transfer from the Yangtze River Delta. This accelerates the process of a diversified industrial structure. In addition, the resource-based cities in this province are mostly mature, declining, or regenerative resource cities. They have a strong demand for seeking green substitute and alternative industries and achieving sustainable development.

Based on the above background, this study aims to clarify the spatial-temporal evolution patterns of carbon emissions under the influence of land use changes in resource-based cities in Anhui Province. It will further identify the key influencing factors of carbon emissions within the region. This study can provide a theoretical basis for optimizing land use structures and formulating differentiated emission reduction policies for such cities.

Due to the concentration of population and economic activities, cities are regions with higher carbon emissions, and their carbon neutrality has attracted extensive attention from scholars. In terms of the implementation measures for urban carbon neutrality, Seto et al. proposed carbon reduction plans from the perspectives of emission reduction measures within the city, decarbonization of cross-regional supply chains, and utilization of urban landscapes [1]. Ziozias et al. emphasized the use of digital technologies, green information and communication technologies, and changes in citizens’ behaviors to achieve carbon neutrality [2]. Luo et al. summarized the schemes for enhancing the carbon sink function of urban ecological space from the aspects of vegetation carbon pool, soil carbon pool, and spatial layout [3]. In terms of the assessment of urban carbon neutrality levels, Zhu et al. evaluated the spatial variations in carbon metabolism and analyzed the impact of land use types on carbon metabolism balance in different scenarios [4]. Li et al. found that the distribution of carbon neutrality rates in cities of different industrial types was uneven, and the influencing factors were different [5]. Some scholars have also made predictions on the trend of urban carbon neutrality. For instance, Chen and Yang predicted the time of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality in the Yangtze River Delta region [6].

Compared with other cities, resource-based cities are under greater pressure regarding carbon emissions. At present, the research on carbon emissions in resource-based cities mainly focuses on the impacts of policies and markets, the differences in carbon emissions among various resource-based cities, the influencing factors of carbon emissions, and simulation predictions: Hou et al. and Feng et al. examined the effects and mechanism of national policies on carbon emission reduction at the city level and the enterprise level [7,8]. The research conducted by Wang et al. indicates that there is a positive correlation between the intensity of environmental regulations and the efficiency of factor market allocation and the improvement of carbon emission performance [9]. Liao et al. discovered that there were significant regional differences in carbon emissions in China’s resource-based cities, and the main source of carbon emissions was industrial energy carbon emissions [10]. Wang et al. constructed five carbon emission systems, including economy, energy, etc., and through multi-scenario simulations, they explored the optimal path and policy regulations for achieving the carbon peak in resource-based cities [11].

In recent years, scholars have conducted in-depth studies on carbon emissions from land use. The main methods used to calculate carbon emissions from land use include direct measurement, life cycle assessment, emission coefficient approach, material balance, and remote sensing estimation [12,13,14,15]. Different methods vary in their principles, data requirements, and operational characteristics, and thus are suitable for different application scenarios. Li et al. employed life cycle assessment to simulate the impact of different agricultural management practices on greenhouse gas emissions in China’s wheat–maize rotation systems [16]. Kong et al. utilized remote sensing estimation in their research to clarify the extent and pathways of human activity and climate change influences on aboveground carbon storage in Northwest China’s grasslands [17]. Research scales have also been explored, ranging from national, provincial, and municipal levels to watersheds [18,19,20]. Marchi et al. constructed a regional carbon cycle simulation framework and estimated the carbon budget of the Siena province in Italy [21]. Jiang et al. used nighttime light data to analyze the spatiotemporal patterns and heterogeneity of carbon emissions in the Yangtze River Basin [22]. Yang et al. developed a modified IPAT model to forecast land use carbon emissions under various scenarios in Quzhou County [23]. For identifying influencing factors of carbon emissions, studies often employ methods like the LMDI decomposition model, Kaya identity, and STIRPAT model to structure the linear relationships between influencing factors and carbon emissions [24,25]. Zhang et al. applied the Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) method to analyze land use carbon emissions. Their findings identified economic development and energy efficiency as the primary promoting and inhibiting factors, respectively [26]. Li et al. combined the STIRPAT model with a GA-BP model, using coal consumption, population, energy intensity, etc., as independent variables and setting different growth rate scenarios to predict the carbon peak year [27]. Pan et al. discovered that the driving factors for land use carbon emissions vary among coal resource cities at different development stages [28].

Studies on carbon emissions, carbon neutrality, and land use carbon emissions in cities have become increasingly abundant. Scholars have explored these issues through different perspectives and methods, thus forming a diversified research framework. However, most of the existing studies focus on the carbon emission situations or carbon neutrality paths of provinces, basins, or individual cities. Studies on resource-based cities mainly focus on comparing the carbon emissions of different resource-based cities across the country or analyzing the impact of different industries on carbon emissions. However, studies analyzing the carbon source and carbon sink characteristics of land use in resource-based cities are relatively rare. Anhui is a province where resource-based cities are densely distributed in eastern China. Such resource-based cities are crucial for the healthy development of the economy and the coordinated development of regions. Most of these cities belong to mature, declining, and regenerative cities, which are in a critical period of transformation and undertaking industrial transfer. Therefore, their land use and carbon neutralization problems face multiple challenges.

This research takes the nine resource-based cities in Anhui Province as the research objects, uses the carbon emission coefficient method to calculate the carbon sources and carbon sinks of different land use types, and analyzes the spatio-temporal evolution characteristics of carbon emissions. The LMDI model is used to identify the key factors influencing carbon emissions. We further analyze the spatiotemporal evolution of carbon emissions and employ a Monte Carlo simulation to model emission variations under ±20% perturbations of carbon emission coefficients, thereby assessing the reliability of the emission estimates. The results can provide a basis for the planning of land space in resource-based cities in Anhui Province, and offer references for formulating differentiated policies on carbon emission reduction and economic development.

Compared with existing research, this study provides three main contributions. First, by combining carbon emission coefficient accounting, LMDI-based driver decomposition, and Monte Carlo simulation, it establishes an integrated analytical framework that links land use change, the spatiotemporal distribution of carbon sources and sinks, and the decomposition of driving mechanisms. This framework enables a process-based characterization of how carbon emissions are generated in resource-based cities. Second, drawing on empirical evidence from resource-based cities in Anhui Province, the study clarifies the intrinsic relationship between land use transitions and regional carbon balance. It offers a representative case that can support the exploration of sustainable development pathways for resource-based cities in central China. Third, from the perspective of land use structural heterogeneity, the study identifies a distinct spatial mismatch between carbon sources and carbon sinks, with higher emissions in the northern part of the region and lower emissions in the south. On the basis of this pattern, the nine resource-based cities in Anhui are categorized into high-emission core areas, transformation demonstration areas and high carbon sink conservation areas. This classification provides a scientific foundation for designing differentiated emission reduction strategies.

2. Study Area

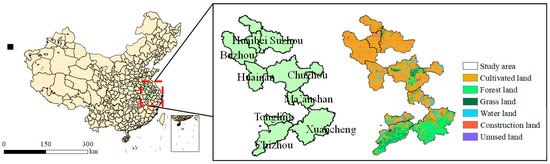

Anhui Province is an important mineral resource base in China. This study focuses on its nine resource-based cities, Huaibei, Bozhou, Suzhou, Huainan, Chuzhou, Ma’anshan, Tongling, Xuancheng, and Chizhou, as illustrated in Figure 1. The landform types in this area are diverse. The northern part lies on the southern fringe of the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, where land use is dominated by cultivated land and industrial/mining construction land. The south transitions into the Jianghuai hilly region and the mountainous areas of Southern Anhui, which exhibit more extensive forest coverage. The total area of these cities spans approximately 58,000 km2, accounting for about 41.5% of Anhui’s total area, and serves as a crucial energy and raw material supply zone for the Yangtze River Delta region. These resource-based cities supply over 70% of the province’s coal, steel, and non-ferrous metal production at present. However, they also face severe challenges such as resource depletion, ecological rehabilitation, and industrial transformation. In 2020, the per capita disposable income of urban residents in Anhui Province was CNY 39,442.1. Among these resource-based cities, only Ma’anshan, Xuancheng, and Tongling exceeded this provincial average. Therefore, it is urgent to study the spatiotemporal evolution of land use carbon emissions in these resource-based cities and to analyze the interaction mechanisms between carbon emissions with socio-economic factors (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the study area and types of land use.

3. Materials and Methods

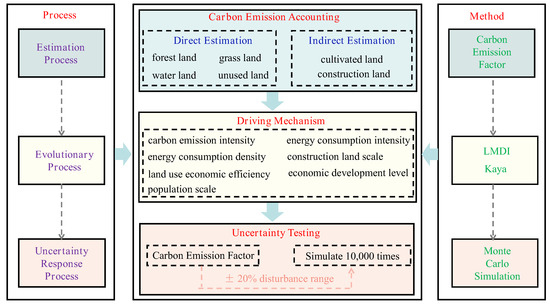

Figure 2 illustrates the overall analytical framework and technical pathway adopted in this study. We establish a process-oriented framework comprising three sequential components: “carbon emission generation, driver-induced evolution, and robustness verification”. This framework extends beyond the characterization of the spatiotemporal patterns of carbon emissions to emphasize the underlying formation mechanisms, evolutionary pathways, and uncertainty response processes.

Figure 2.

Research framework diagram.

First, during the carbon emission estimation stage, land use categories are classified into those suitable for direct measurement and those requiring indirect estimation. Forests, grasslands, water bodies, and unused land are assessed using direct accounting methods to quantify carbon sequestration and emissions. In contrast, cropland and construction land, which accommodate more intensive human activities, are evaluated using indirect estimation methods. The carbon emission coefficients associated with these land use types provide the fundamental input to the estimation system and constitute the initial phase of the carbon emission generation process.

Second, on this basis, the analysis proceeds to the decomposition of emission drivers. A multidimensional set of influencing factors is constructed around carbon emission intensity, energy consumption intensity, energy consumption density, construction land expansion, land use economic efficiency, economic development level, and population size. Using the Kaya identity and the Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) model, we perform index decomposition to quantify the contribution of each factor to changes in carbon emissions and to trace their temporal trajectories. This component captures the evolution of carbon emissions from observed outcomes to underlying drivers, underscoring the causal pathways that shape emission dynamics.

Third, a closed-loop verification process is developed to ensure the credibility of the results. A Monte Carlo simulation is employed to conduct robustness testing, wherein a ±20% perturbation range is applied to carbon emission coefficients. A total of 10,000 random simulations are performed to evaluate the sensitivity of the estimation results to parameter fluctuations and to assess the stability of carbon emission estimates under uncertainty. This module represents the “disturbance–response” process within the evaluation system, thereby ensuring the reliability of the study’s findings and the scientific soundness of the resulting policy recommendations.

3.1. Carbon Emission Measurement

Carbon emissions from forest land, grass land, water land, and unused land were quantified using the direct measurement approach. In contrast, for cultivated land and construction land, which support intensive and multifaceted anthropogenic activities, the direct method introduces significant estimation errors. Consequently, an indirect measurement methodology was employed for these land use categories to enhance accounting accuracy [29].

- Direct Measurement Approach

Carbon emissions from forest land, grass land, water land, and unused land were quantified using the direct coefficient method. The calculation follows this equation:

where Ei denotes the total direct carbon emissions; ei represents the carbon emissions attributable to the i land use category; Si signifies the area of the i land use type; and δi corresponds to the carbon emission coefficient for the i category. The resource-based cities in Anhui Province covered by this study span diverse eco-geographical units. Northern cities, such as Huaibei and Bozhou, are situated on the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, a region characterized by intensive agricultural activity where forest cover predominantly consists of plantation forests. In contrast, southern cities, including Xuancheng and Chizhou, are located within the mountainous terrain of southern Anhui, where there are more abundant resources of subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forest. This heterogeneity in underlying surface conditions implies that the application of a uniform carbon coefficient may introduce a degree of uncertainty when estimating absolute carbon budgets. To mitigate this potential source of error and enhance the validity of the selected parameters, this study prioritized coefficients derived from research conducted in analogous ecological contexts, specifically the Eastern Monsoon Region of China and other subtropical climatic zones. Consequently, the core forest carbon sink coefficient adopted herein is primarily sourced from empirical measurements of forest ecosystems in Eastern China, an area that exhibits a high degree of ecological similarity to the southern part of our study region [30,31]. The specific carbon emission coefficients for forest land, grass land, water land, and unused land are −0.644 t·hm−2·a−1, −0.021 t·hm−2·a−1, −0.0248 t·hm−2·a−1, and −0.0005 t·hm−2·a−1, respectively [32].

- Indirect Measurement Approach

Carbon emissions from cultivated land were estimated indirectly using the following indicators: irrigated area, total crop sown area, total agricultural machinery power, agricultural plastic film usage, and pure fertilizer application. The calculation follows this equation:

where Eq represents the total carbon emissions from cultivated land; Ei denotes the carbon emissions from the i category of agricultural activity; ei corresponds to the activity level of the i agricultural practice; and θi signifies the carbon emission coefficient for the i agricultural activity. The carbon emission coefficients for irrigated area, total crop sown area, total agricultural machinery power, agricultural plastic film usage, and pure fertilizer application are 266.48 kg/hm2, 3.13 kg/hm2, 0.18 kg/kW, 5.18 kg/kg, and 4.93 kg/kg, respectively [33].

For provincial-level construction land carbon emissions, eight energy sources were selected for indirect calculation: raw coal, coke, crude oil, gasoline, kerosene, diesel, natural gas, and fuel oil. The energy consumption data were derived from the final energy consumption figures for each city. Owing to insufficient energy data availability at the prefectural city level within Anhui Province, carbon emissions from construction land at the municipal scale were estimated using an energy consumption per unit of GDP approach [34]. The calculation follows this equation:

where Ep denotes the total carbon emissions from construction land; Ej represents the carbon emissions generated by the j energy type; ej corresponds to the consumption of the j energy type; θj signifies the standard coal conversion coefficient for the j energy type; and βj indicates the carbon emission coefficient for the j energy type. Furthermore, Ec represents the construction land carbon emissions for the j region; Ep denotes the total construction land carbon emissions for Anhui Province; GDPj signifies the Gross Domestic Product of the j region; and Dj represents the energy consumption per unit of GDP for the j region. The standard coal conversion coefficients were obtained from the China Energy Statistical Yearbook, while the carbon emission coefficients were sourced from the emission factors published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Carbon emission coefficients for energy sources.

3.2. LMDI Model

Based on the fundamental form of the Kaya identity, the carbon emissions from resource-based cities in Anhui Province are decomposed as follows [35,36]:

where the variables C, GDP, E, LC, L, and P denote total carbon emissions, regional gross domestic product, total energy consumption, construction land area, total land area, and total population, respectively. Furthermore, CEI, EI, EUD, BLA, LEE, EDL, and PS represent carbon emission intensity, energy consumption intensity, energy consumption density, construction land scale, land use economic efficiency, economic development level, and population scale, respectively. These variables collectively characterize the influencing factors of carbon emissions.

Factor decomposition models for carbon emissions primarily comprise index decomposition analysis and structural decomposition analysis. Among these, the logarithmic mean Divisia index model, a specific form of index decomposition analysis, effectively disaggregates total carbon emissions into a multiplicative combination of several key influencing factors. This approach elucidates the specific contribution and evolutionary trajectory of each factor to carbon emissions [37]. Consequently, this study employs the additive decomposition form of the LMDI method to decompose the influencing factors of carbon emissions in resource-based cities within Anhui Province. The calculation follows this equation:

where t represents time t, and 0 denotes the base period. The term ∆C represents the change in agricultural carbon emissions from the base period to time t. The variables ∆CEI, ∆EI, ∆EUD, ∆BLA, ∆LEE, ∆EDL, and ∆PS correspond to the respective contribution values of carbon emission intensity, energy consumption intensity, energy consumption density, construction land scale, land use economic efficiency, economic development level, and population scale to the change in carbon emissions between the base period and time t. According to the LMDI decomposition methodology. The calculation follows the equations below:

3.3. Data Sources

The land use data for Anhui Province from 2000 to 2020 utilized in this study were obtained from the Annual China Land Cover Dataset (CLCD) produced by Professor Huang Xin at Wuhan University, which has a spatial resolution of 30 m (https://essd.copernicus.org/articles/13/3907/2021/ accessed on 9 August 2025.). Energy consumption data were sourced from the China Energy Statistical Yearbook (2001–2021). Concurrently, based on relevant data from the China Statistical Yearbook and Anhui Statistical Yearbook (2001–2021), socio-economic data for Anhui Province from 2000 to 2020, including population and GDP, were collated and compiled.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Land Use Carbon Emission Changes

4.1.1. Temporal Variation Characteristics of Land Use Carbon Emissions

Table 2 shows the carbon emissions based on land use of resource-based cities in Anhui Province from 2000 to 2020. During this period, the carbon sink system of resource-based cities in Anhui Province was mainly composed of forest land. The overall carbon absorption capacity exhibited an increase, with the total carbon absorption rising from 9.7 × 105 t to 9.82 × 105 t. In contrast, the carbon sequestration function of grass land experienced a continuous weakening, with a substantial decline of 68.53%. The absorption capacity of water land demonstrated a non-linear trend, increasing initially until an inflection point around 2015, after which it began to decrease. The carbon source system comprised cultivated land and construction land. The total carbon emissions from these sources increased by 143.60% over the two decades. Cultivated land has long been the primary source of carbon. Consequently, net carbon emissions increased by 149.60%. After 2015, the growth rate of carbon emissions slowed down, and the amounts of carbon sources and carbon sinks showed a trend of “weak balance”.

Table 2.

Net carbon emissions of resource-based cities in Anhui Province from 2000 to 2020.

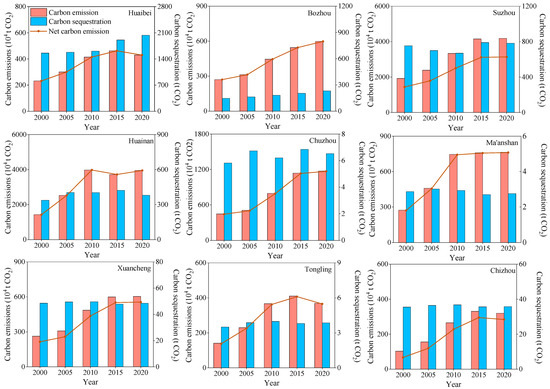

Figure 3 illustrates the carbon budget based on land use of the nine resource-based cities in Anhui Province from 2000 to 2020. During this period, the total carbon emissions of these cities exhibited a characteristic of “sustained growth with a decelerating rate.” From the perspective of carbon emissions of each city, the regional differences exhibit a gradient differentiation feature. Chuzhou had consistently ranked first in terms of total carbon emissions, which increased from 4.47 × 106 t in 2000 to 1.17 × 107 t in 2020, an increment of 7.28 × 106 t over the two decades. This is closely linked to its developmental role as a key energy base and industrial agglomeration zone in eastern Anhui. Suzhou and Bozhou followed, both with emissions exceeding 8 × 106 t in 2020. These cities, dominated by coal resource exploitation and coal chemical industries, have long sustained high energy consumption intensity. In contrast, Chizhou, while having the smallest emissions, experienced the most rapid growth rate, surging from 1.03 × 106 t in 2000 to 3.20 × 106 t in 2020—an increase of 210.78%. This reflects the carbon emission pressure faced by such resource-based cities during their industrialization process. It is worth noting that the carbon emission situation in traditional high-energy-consuming cities has undergone significant changes. Huainan, a nationally significant energy base, saw its emissions peak at 5.97 × 106 t in 2010 before slightly declining to 5.93 × 106 t by 2020. This trend correlates with local efforts to promote low-carbon upgrades in the coal power industry and develop Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) technologies. Tongling, a non-ferrous metal resource-based city, reached an emission peak of 4.10 × 106 t in 2015, after which emissions began to decline, demonstrating the role of industrial transformation in driving emission reduction.

Figure 3.

Temporal trends in carbon emissions, carbon absorption, and net carbon emissions of resource-based cities in Anhui Province from 2000 to 2020.

The carbon absorption data show that the ecological carbon sequestration capacity of resource-based cities in Anhui Province remained stable from 2000 to 2020, and its change trend was highly coupled with the evolution trend of forest land area, which serves as the core carbon sink. This reveals the stability of regional ecological functions and the pressure faced by some areas. (Figure 3, Table S2)

From the perspective of temporal evolution, in cities with stable carbon sink functions, the amount of forest resources remained stable or even increased. The carbon absorption in Xuancheng fluctuated slightly within the range of −4.85 × 105 t to −4.96 × 105 t, while the forest area remained stable at a high level of 74.05 million m2 to 76.93 million m2. The carbon absorption capacity of Chizhou remained stable between 3.55 × 105 t and 3.68 × 105 t, and the forest area also consistently stayed within the range of 55.18 million m2 to 56.96 million m2. These reflected that the complete forest ecosystem of the resource-based cities in southern Anhui Province served as the guarantee for their strong and stable carbon sequestration capacity.

In contrast, the changes in carbon sinks in some cities clearly demonstrated the encroachment of human activities on ecological space. The carbon absorption capacity of cities in the northern region, such as Huaibei and Huainan, had shown a slow downward trend, which decreased by about 30.5% and 12.5%, respectively, over these 20 years. This trend was directly related to the increase in the area of construction land: the forest area in Huaibei had changed from 22.2 million m2 to 29.23 million m2, and that in Huainan had changed from 18.62 million m2 to 21.86 million m2. Although the forest land area in these two cities had increased, the growth rate was much lower than that of the expanded construction land. This indicated that during the rapid urbanization and industrialization process, the new forest land had not been able to fully compensate for the carbon sink loss caused by the transformation of ecological land, reflecting the cumulative effect of the continuous occupation of ecological space by the expansion of construction land.

The net carbon emissions (the difference between total carbon emissions and carbon sequestration) characterizes the carbon balance status. From 2000 to 2020, the net emissions of Anhui’s resource-based cities overall followed an evolutionary trend of “rapid growth–tending to be stable”, increasing from 2.07 × 107 t in 2000 to 4.94 × 107 t in 2020—a rise of 138.6%. However, after 2015, the growth rate decelerated markedly from an annual average of 8.2% to just 1.1%, demonstrating the effects of emission reduction policies and technological innovation. According to the net emission characteristics, the cities can be classified into three types. (1) High emission–strong growth type: This includes Bozhou and Suzhou, with net emissions reaching 7.97 × 106 t and 8.36 × 106 t, respectively, in 2020, and increases exceeding 118% over the period. These cities are still at the peak of resource exploitation, where economic growth and carbon emissions have not yet decoupled. (2) High emission–stabilizing type: This is represented by Chuzhou and Ma’anshan, where the growth rate of net emissions fell below 3% after 2015. In 2020, the net emissions in Chuzhou reached 1.17 × 107 t. Although it was the highest in the region, it had shown a characteristic of “stabilizing total emissions”. (3) Medium–low emission–stabilizing or declining type: This includes Tongling and Huainan, where net emissions peaked in 2015 and 2010, respectively, and have since begun to decrease. This demonstrates the emission reduction effectiveness of transformation in resource-based cities. For example, Huainan had achieved the goal of absorbing 1.8 × 105 t of CO2 annually by developing the carbon dioxide-based new material industry. This had effectively improved the balance of carbon emissions and absorption.

4.1.2. Classification of Urban Carbon Balance Types Based on Emission–Sequestration Characteristics

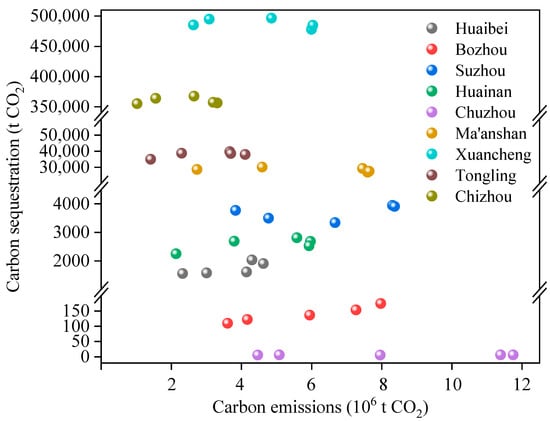

To illustrate the different situations of carbon balance in each city more clearly and provide a basis for regional carbon reduction policies, we designed a two-dimensional scatter plot with carbon emissions as the X-axis and carbon sequestration as the Y-axis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Classification of carbon emission and carbon sequestration levels of resource-based cities in Anhui Province.

The carbon emission characteristics of Chuzhou, Suzhou, and Bozhou are “high emissions–low carbon sinks”, so these three cities can be defined as core high-emission areas. In 2020, the total carbon emissions of these three cities reached 2.81 × 108 t, accounting for 58.5% of the total for the entire region. However, the total carbon absorption of these three cities was only 4.09 × 103 t, which was less than 0.5% of the total amount of the whole area. This severe “source–sink imbalance” situation indicates that these cities are the regions with the greatest pressure and the most urgent task of carbon emission reduction.

Huaibei, Huainan, Tongling, and Ma’anshan belong to the type of “high emission–high carbon sink” and “moderate–low emission–low carbon sink”, which can be defined as the transformation demonstration area. The total carbon emissions of these cities were 1.54 × 107 t, accounting for 32.0% of the entire region. The total carbon absorption was 1.09 × 105 t, accounting for 11.4% of the entire region. Both the carbon emissions and carbon absorption levels were at a moderate level. Among them, Ma’anshan had the characteristic of “high emissions–high carbon sink”. This city faces significant pressure from industrial carbon emissions, but its abundant forest resources also provide a strong carbon sink capacity. The carbon emissions of Huaibei, Huainan, and Tongling had shown a characteristic of “moderately low emissions–low carbon sink”, and their carbon emissions had dropped from the historical peak, indicating the initial success of industrial transformation. However, the carbon absorption capacity of all these areas was below 4 × 103 t, indicating that the restoration of the ecosystem and the enhancement of carbon sink capacity remain significant weaknesses. Therefore, we define these cities as “transformation demonstration zones”, aiming to highlight that they are at a crucial stage of transitioning from the traditional development model to the low-carbon development model. They need to explore a comprehensive development path that balances economic growth, significant emission reduction, and ecological restoration.

The carbon emission characteristics of Xuancheng and Chizhou are “low carbon emissions–high carbon sinks”. These cities play a crucial role as the “ecological lungs” of the region and can be defined as high-carbon-sink areas. In 2020, the total carbon emissions of the two cities amounted to 9.24 × 108 t, accounting for only 9.6% of the total emissions of the entire region; however, their carbon absorption volume reached 8.42 × 105 t, accounting for 88.4% of the total amount of the entire region. These data indicate that the ecosystems of these cities have achieved significant net carbon sink benefits, playing an irreplaceable pivotal role in maintaining the regional carbon balance.

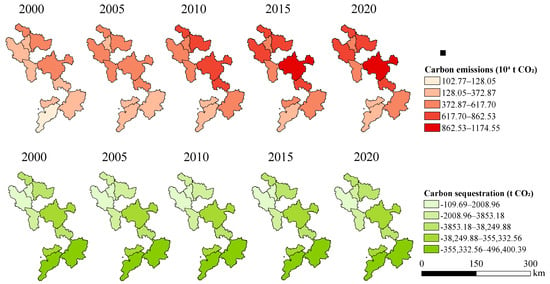

4.1.3. Spatial Variation Characteristics of Land Use Carbon Emissions

Figure 5 presents the spatial distribution of the carbon budget of Anhui’s resource-based cities from 2000 to 2020. The analysis of the results, from the perspective of spatial heterogeneity and synergistic evolution between carbon emissions and absorption, reveals the dynamic characteristics of the regional carbon source–sink structure. Carbon emissions in these cities exhibited a pattern of “core agglomeration with gradient diffusion.” In 2000, high-emission zones were concentrated only in some parts of Chuzhou. From 2015 to 2020, the high-emission agglomeration zone had expanded continuously, and secondary high-value zones had formed in Suzhou City and Bozhou. In contrast, traditional resource-based cities like Huaibei and Huainan maintained high emission intensity but showed relatively stable spatial extents. This spatial structure was highly consistent with regional industrial layout: Chuzhou, as an industrial and energy hub in eastern Anhui, experienced industrial land expansion and consequent carbon emission agglomeration following industrial transfer. Suzhou and Bozhou, reliant on coal resource development and coal chemical industries, formed growth poles for carbon emissions along the resource belt. Regarding the evolutionary trend, the spatial agglomeration of carbon emissions intensified significantly. From 2000 to 2020, the spatial connectivity of high-emission areas increased by 42%, while low-emission areas became more fragmented. This change reflects the “Matthew Effect” of industry and population concentrating in core areas during the industrialization of resource-based cities.

Figure 5.

Spatial patterns of carbon emissions and carbon sequestration in resource-based cities of Anhui Province from 2000 to 2020.

The spatial distribution of carbon sequestration demonstrated characteristics of “strength in the south, weakness in the north, and solidified pattern.” Southern cities, Xuancheng and Chizhou, consistently maintained high sequestration levels, directly attributable to their land use structures dominated by forest land. Conversely, northern cities like Huaibei and Bozhou exhibited very weak sequestration capacity, where the dominance of cultivated and construction land limited ecological carbon sequestration functions. Between 2000 and 2020, the spatial pattern of carbon sequestration did not change markedly; the spatial differentiation coefficient between high- and low-carbon-sink areas remained stable above 0.7. This indicates a strong path dependency in the ecological functions of regional land use, suggesting that fundamental alterations to the carbon sink are difficult to achieve through short-term human intervention.

Regarding the synergistic relationship within the carbon budget, a spatial mismatch is evident: “high-emission areas suffer from insufficient carbon sinks, while high-sink areas have limited emissions.” In core emission zones like Chuzhou and Suzhou, the carbon sequestration capacity amounted to only 5–8% of total emissions. In contrast, high-sink areas like Xuancheng and Chizhou had emission intensities less than 30% of those in the core zones. This spatial mismatch has led to a high concentration of regional carbon emission reduction pressure in a few cities, and has also weakened the carbon offsetting effect of ecological carbon sinks.

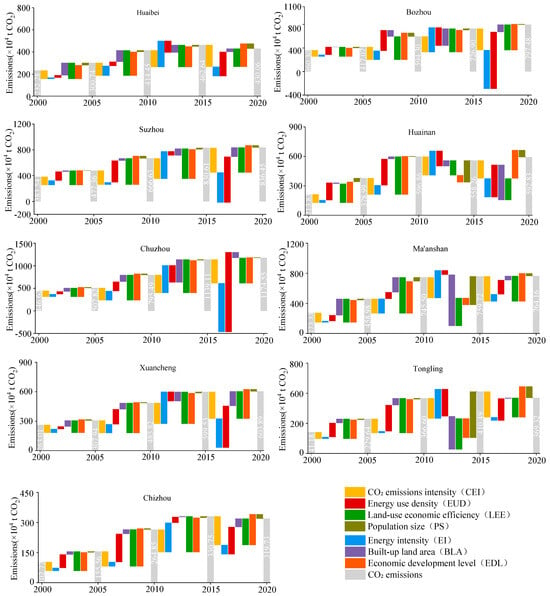

4.2. Driving Factors of Carbon Emissions

The LMDI method was employed to find the driving factors of carbon emissions in the nine resource-based cities of Anhui Province from 2000 to 2020. We analyzed the dynamic evolution mechanism from seven dimensions: CEI, EI, EUD, BLA, LEE, EDL, and PS. Figure 6 and Table S1 present the driving effects of these different influencing factors on each city.

Figure 6.

Contribution effects of driving factors for carbon emissions in resource-based cities of Anhui Province from 2000 to 2020.

(1) Emission reduction factors: CEI and LEE. CEI was the most significant inhibiting factor. Its average negative contribution to carbon emission of the nine cities increased from −9.39 × 106 t in 2000–2005 to −2.29 × 106 t in 2015–2020, a cumulative enhancement of 143.86%, indicating substantial achievements in technological emission reduction. The negative contribution of CEI in Chuzhou was the most significant. From 2015 to 2020, the contribution value of CEI reached −5.27 × 106 t. Due to the elimination of 1.2 × 106 t of backward chemical production capacity in this city after 2015, the carbon emission per unit of GDP decreased by 42% compared to 2010. In contrast, Chizhou exhibited the weakest negative CEI contribution (−1.43 × 106 t in 2015–2020), due to its smaller industrial scale and consequently limited potential for technological emission reductions. LEE consistently exerted a negative contribution, with its average inhibitory effect on carbon emission of the nine cities expanding by 85.2% in 2000–2020. The negative contribution of LEE was generally greater in northern Anhui cities than in southern ones, reflecting more pronounced effects of land intensification policies under greater pressure from construction land expansion in the north.

(2) Emission promoting factors: EDL, EUD, and BLA. EDL was a positive driver. Its average contribution increased from 1.34 × 106 t in 2000–2005 to 3.15 × 106 t in 2015–2020, a cumulative rise of 135.0%, establishing it as the core driver of carbon emission growth. After 2015, the average annual growth rate of EDL decreased from 12% to 5%, indicating that resource-based cities began to explore the “low-carbon growth” model and achieved certain results. EUD made a positive overall contribution to carbon emissions. From 2000 to 2020, the average contribution of EUD of the nine cities increased from 7.46 × 105 t to 3.58 × 106 t, with a cumulative increase of 380.6%. The calculation results show that during the period from 2000 to 2020, the total energy consumption in the study area increased by 4.8 times, while the area of construction land only expanded by 0.9 times. The proportion of coal consumption remained above 65%. In 2020, the proportion of renewable energy in this region was only 8.2%, lower than the average level of Anhui Province. Natural gas accounted for only 10% of the total energy consumption. These indicate that the process of converting between new and old energy sources is lagging behind. Take the typical city of Chuzhou as an example. Its energy consumption had increased by nearly 10 times, but the construction land had only increased by 1.3 times. This had led to a sharp increase in the energy consumption intensity per unit of land. This imbalance between energy and land use efficiency indicates that economic growth is still highly dependent on the extensive input of energy, which is a direct manifestation of “high-carbon lock-in” at the land use level. Notably, during 2010–2015, the contribution of EUD turned negative for most cities due to increased hydropower output following extreme precipitation events, which temporarily reduced coal consumption. BLA mainly contributed positively, but in some years for certain cities, BLA had a negative contribution. The contribution of BLA of Huainan from 2015 to 2020 was −3.59 × 106 t. Due to the governance of coal mining subsidence areas in Panji District of this city, the construction land was converted into ecological land, which temporarily suppressed the growth of carbon emissions. Similarly, in Ma’anshan (2010–2015), BLA contributed −6.81 × 106 t following the relocation of a steel plant and the subsequent reclamation of the old site into forest land, reducing emissions from construction land.

(3) The contribution directions of EI and PS had changed with a relatively weak overall influence. The contribution direction of EI showed a significant reversal trend. During the period 2000–2010, it acted as a positive driver, with a mean contribution of 1.56 × 106 t. However, it transitioned to a negative inhibitory effect after 2015, yielding a mean contribution of −2.86 × 106 t. A notable exception was Ma’anshan, where the EI contribution remained positive at 9.44 × 105 t from 2015 to 2020. Although energy-saving retrofits were implemented in its steel industry, the resulting gains in energy efficiency were partially offset by the increased output of crude steel.

The contribution intensity of PS on carbon emissions was substantially lower than that of other factors, with a mean value of only 1.23 × 105 t and exhibiting directional change. For example, Huainan had the contribution of PS of 2.22 × 106 t between 2010 and 2015. This was attributable to the expansion of coal mining operations, which introduced nearly 120,000 new miners and their dependents, whose associated increase in residential energy consumption accounted for 18% of the city’s total emission growth in that period. Conversely, Tongling exhibited a negative PS contribution of −7.53 × 105 t from 2015 to 2020. Due to the depletion of copper resources and the outflow of labor force, the decline in population had become a factor contributing to the reduction of carbon emissions.

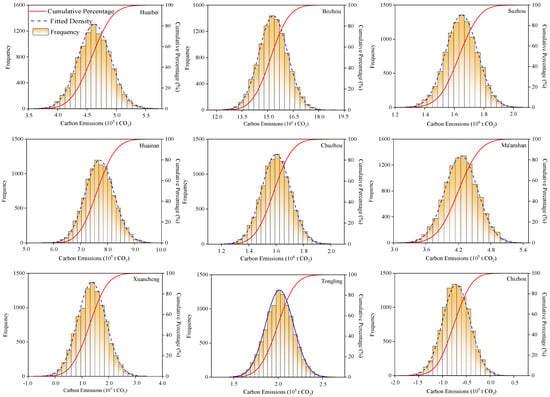

4.3. Instability Test of Carbon Emission Calculation

To evaluate the sensitivity of agricultural carbon emission estimates to the specification of emission coefficients, a ±20% perturbation was applied to the carbon sink coefficients for forests, grasslands, water bodies, and unused land as used in the preceding analysis (Figure 7). A Monte Carlo simulation with 10,000 iterations was conducted to assess the impact of these parameter variations. The results indicate that the simulated mean and median values for each city are highly consistent, with negligible relative deviations. For instance, in Huaibei, the simulated mean is 46.26 × 104 t, while the median is 46.25 × 104 t, showing near-perfect agreement and indicating that the point estimate is not affected by extreme values. Moreover, the skewness coefficients for all cities range between −0.030 and 0.075, and the kurtosis values approximate the standard for a normal distribution.

Figure 7.

Monte Carlo simulation results of carbon emissions for resource-based cities in Anhui Province from 2000 to 2020.

To further characterize the range of emission variability and potential risk, cumulative probability distributions were constructed, and the 5% and 95% percentiles were taken as confidence bounds. The results demonstrate that high-emission cities exhibit relatively stable emission intervals. In Bozhou, for example, there is a 90% probability that emissions fall within the range [139.60, 167.30] × 104 t, indicating that its high-emission characteristic persists even under the most conservative and aggressive scenarios. Critical cities display higher sensitivity: although Xuancheng has a positive mean value, its 5% scenario is only 5.01 × 104 t, revealing that its net emissions are vulnerable to parameter changes. In contrast, carbon sink cities show remarkable robustness; in Chizhou, the 95% remains −2.32 × 104 t, demonstrating that it retains a net carbon sink status even under the most adverse parameter combinations, thereby providing statistical support for its role as a regional ecological buffer.

From a system robustness perspective, the coefficient of variation (CV) confirms the model’s error-damping capacity. Excluding Xuancheng and Chizhou, whose CVs are slightly elevated due to offsetting effects between sources and sinks, the remaining seven cities maintain CVs within the 5.48–7.83% range. Considering that input parameter uncertainty was set as high as 20%, the observed relative fluctuation of approximately 6% in outputs demonstrates that the model possesses significant error attenuation capability and overall robustness.

5. Discussion

- Spatio-temporal differentiation and driving mechanisms of carbon emissions

This study systematically reveals the spatio-temporal evolution patterns and driving mechanisms of carbon emissions based on land use in resource-based cities in Anhui Province from 2000 to 2020. In temporal terms, net carbon emissions exhibit an overall increasing trend over the twenty-year period, although the growth rate slows markedly after 2015 and enters a clear plateau phase. This key turning point was highly consistent with the relevant policies issued intensively during the same period [38]. In 2015, the National Development and Reform Commission of China made it clear that China would further promote the pilot programs for carbon emission rights trading and strive to achieve the carbon peak target by 2030. The State Council of China issued the first document specifically dedicated to ecological civilization construction, with energy conservation and emission reduction as its main tasks. At the same time, Anhui Province put forward carbon emission reduction requirements for 1031 specific projects of 14 different types. From a spatial perspective, resource-based cities in Anhui Province exhibit a pronounced “core–periphery” structure together with a clear mismatch between carbon sources and carbon sinks. Cities in the northern part of the province, including Chuzhou, Suzhou, and Bozhou, constitute the high-emission core area. Industrial land accounts for approximately 35% to 42% of their urban land, and industrial energy consumption represents about 45% of total provincial energy use, resulting in a strong concentration of carbon sources. By contrast, southern cities such as Xuancheng and Chizhou display forest coverage rates of 45% to 52% and industrial land proportions of less than 15%, forming a stable carbon sink zone. This spatial configuration implies that regional carbon balance is heavily dependent on a limited number of ecological function areas. High-emission cities lack sufficient local carbon sinks to offset their carbon outputs, thereby intensifying the overall emission reduction pressure. These findings underscore the importance of regional zoning management and the protection of key ecological function zones. It would take measures such as early warnings and restricting new construction projects for regions with poor carbon emission reduction effects [39]. In terms of spatial distribution, the carbon emissions of resource-based cities in Anhui Province showed a typical “core–periphery” structure and “source–sink mismatch” characteristics. Carbon emissions were highly concentrated in cities such as Chuzhou, Suzhou, and Bozhou in the north, while most of the carbon sink areas were distributed in cities like Xuanzhou and Chizhou in the south. This spatial pattern implied that the regional carbon balance was highly dependent on a few ecological functional areas. Moreover, the carbon sink capacity of the high-carbon emission areas was insufficient to offset their massive carbon emissions, thereby increasing the overall pressure for carbon reduction.

The results of the driving factors analysis further revealed the dilemma of “high-carbon lock-in” and the potential for “transformation breakthrough” in resource-based cities in Anhui Province. The economic development level (EDL) is the most core positive driving factor for the growth of carbon emissions, with its cumulative contribution reaching 42.3%. This indicates that during the study period, there was no decoupling between regional economic development and energy consumption, and the economic growth still highly relied on resource consumption. Between 2000 and 2019, total carbon emissions in Anhui Province increased at an average annual rate of approximately 4.9%. Over the same period, the share of emissions generated by energy consumption rose from 77.3% to 91.1%. This shift demonstrates that energy use, and particularly the consumption of fossil fuels, became the dominant driver of carbon emission growth in the province. The significant positive contribution rate (an increase of 380.6%) of energy consumption density (EUD) not only reflects the increase in total energy consumption, but also reveals the “high-carbon-density” feature of the regional industrial structure and the “high-carbon-lock-in” state of the energy structure. This pattern is consistent with a provincial statistical report highlighting the achievements of the past decade. During this period, the carbon emission intensity per unit of GDP in Anhui Province declined by 21.3%, and energy consumption per unit of GDP fell by 31%. Although these improvements indicate progress in emission intensity and energy efficiency performance, they have not been sufficient to reverse the overall upward trajectory of total carbon emissions. It is worth noting that the improvements of two key efficiency factors, i.e., carbon emission intensity (CEI) and energy consumption intensity (EI), constitute the main factors that inhibit carbon emissions, but their mechanisms of action are different. The cumulative contribution rate of carbon emission intensity reached −35.2%. The decline of this indicator indicates that the carbon emissions generated for each unit of GDP have decreased. The core significance of this indicator’s change lies in reducing the “carbon cost” of economic growth. It mainly reflects the achievements of “energy structure optimization” and “terminal decarbonization technologies”. The fact that the energy consumption intensity turned negative after 2015 indicates an overall improvement in the “energy efficiency of the economic system”. The improvement in this indicator means that more GDP can be produced with each unit of energy consumed, indicating an increase in overall energy efficiency and the optimization of the industrial structure. This suggests that the dependence of economic growth on energy is beginning to decrease. The improvement of these two types of driving factors is closely linked to the measures taken by the national and local governments around 2015, such as the mandatory elimination of backward production capacity and the promotion of energy-saving technologies.

- 2.

- Characteristics of carbon emissions in the study area

The research results show that the total carbon emissions of resource-based cities in Anhui Province continued to increase from 2000 to 2020, but the growth rate slowed down. This trend is consistent with the overall growth trend of carbon emissions of China [40,41]. However, compared with the growth rates of 256%, 339% and 245% in the developed regions of Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei, Yangtze River Delta, and Pearl River Delta during the period from 2000 to 2019, the growth rate of carbon emissions in this study area was relatively lower [42]. This difference had been particularly evident after 2015. The contribution rate of the economic development level had significantly slowed down, reflecting the transformation predicament faced by resource-based cities when the traditional industries had weakened, and the new industries had not yet formed.

From the perspective of driving mechanisms, the LMDI decomposition results of this study show that carbon emission intensity and land use economic efficiency are the main emission reduction factors, while economic development level and energy consumption density are the main promoting factors. This finding is consistent with the research results of Xu et al. [43].

Different from agriculture-based areas affected by fertilizer use and energy consumption of agricultural machinery, and rapid urbanization areas affected by population growth and urban expansion, the carbon emissions of resource-based cities in Anhui Province are mainly influenced by the development of the resource industries and the process of transformation [30,44]. It is worth noting that the contribution rate of energy consumption intensity became negative after 2015. This transformation is consistent with the characteristics of developed regions such as Jiangsu and Zhejiang, indicating that these resource-based cities have made significant progress in breaking the “high-carbon lock-in”. The comparison with international research further reveals the differences in carbon emission reduction paths among countries or regions at different development stages. Through measures such as low-carbon transportation and low-carbon housing, the United Kingdom managed to reduce its carbon emissions from 6.88 × 108 t to 3.98 × 108 t between 1995 and 2017 [45,46,47]. Developed countries such as the Czech Republic and Germany mainly rely on improving carbon productivity to promote emission reduction. Emerging economies like South Korea and Turkey emphasize the “development + emission reduction” model and are gradually transitioning to a high-carbon productivity model. In contrast, the resource-based cities in southwestern China, with their abundant clean energy resources and the “West-to-East Power Transmission” project, had a turning point in carbon emissions in 2013, earlier than the study area [48]. For instance, Panzhihua has achieved continuous reduction in its total carbon emissions and intensity by establishing a diversified new energy framework [49]. This provides useful reference for the transformation of resource-based cities. It is particularly noteworthy that the impact of the population on carbon emissions varies significantly among different types of cities. Service-oriented cities experience an enhanced carbon emission effect due to population concentration. In contrast, the population decline caused by resource depletion in this study area has a carbon emission reduction effect, which reveals the challenge of urban shrinkage faced by resource-based cities. These findings indicate that the low-carbon transformation of resource-based cities requires the establishment of a new type of urbanization model that is compatible with the trend of population mobility.

While the findings provide scientific support for regionally differentiated and synergistic emission reduction, this study has several limitations. (1) The carbon emission coefficient method often employs or adapts widely used coefficients. Variations in local topography, forest, and grassland types necessitate future research to fully account for land differences, refine these coefficients, and explore a more comprehensive accounting system for land use carbon emissions. (2) The LMDI method decomposes emission changes into the independent contributions of several pre-defined factors, yet complex interactions exist between these factors. Subsequent research should aim to uncover the non-linear feedback mechanisms among influencing factors and excavate the underlying structural drivers. (3) It is difficult to achieve the overall goal of CCUS (Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage) solely by relying on the natural carbon sequestration capabilities of ecosystems such as forests. In future research, it is worthwhile to incorporate the carbon sequestration effects of technologies like CO2 capture and geological storage into the carbon budget accounting framework, and assess their synergy with land use carbon management.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Conclusions

This study, focusing on resource-based cities in Anhui Province from a land use perspective, provides a detailed analysis of carbon emissions, carbon sequestration, carbon source–sink structures, and spatial patterns from 2000 to 2020. By applying the LMDI method to explore driving factors from seven dimensions and characterizing the imbalance curve between carbon emissions and economic development, it constructs a dynamic model of the carbon emission driving mechanism, offering a theoretical basis for formulating scientific land use and coordinated development policies for such cities.

(1) Temporal evolution of carbon emissions displayed distinct characteristics of “increasing total amount, slowing down growth rate, and stabilizing in the later stage”. Net carbon emissions increased nearly 1.5 times during the study period, but the growth rate slowed significantly after 2015. The net carbon emissions were high, but the growth rate was relatively stable. Spatially, high-emission areas agglomerated around Chuzhou as a core and expanded to coal-rich areas in northern Anhui, like Suzhou and Bozhou. Meanwhile, the carbon sink function areas remained stably distributed in southern Anhui cities like Xuancheng and Chizhou, which are rich in forest land. The carbon sequestration capacity in high-emission zones could only offset 5–8% of their total emissions, while the emission intensity in high-sink areas was less than 30% of that in core emission zones. This mismatch in the regional distribution of carbon emission and absorption capabilities has led to a relatively weak effect of carbon reduction.

(2) The LMDI analysis results reveal that the economic development level and energy consumption density were identified as the primary drivers of emission growth. Conversely, reductions in carbon emission intensity and improvements in land use economic efficiency emerged as the most substantial countervailing factors. Although the influences of energy consumption intensity and population size were comparatively modest, their effects exhibited distinct phase-specific variations. Overall, this decomposition analysis suggests that these cities continue to be influenced by the lock-in effects of their established industrial and energy structures. Within this context, technological advancement and the transition towards more intensive land use patterns have become the dominant forces underpinning recent emission reductions.

(3) The resource-based urban agglomeration in Anhui Province exhibits marked spatial differentiation in its carbon emission condition. Chuzhou, Suzhou, and Bozhou constitute a high-emission core zone, where intensive industrialization and energy-dependent industries create the province’s most pressing carbon mitigation challenge. Designated as transition demonstration areas, Huaibei, Huainan, Tongling, and Ma’anshan are undergoing industrial restructuring, resulting in a dual characteristic of maintaining carbon source functions while preserving measurable carbon sink capacity. In contrast, Xuancheng and Chizhou form a high-carbon-sink conservation area, distinguished by well-preserved ecosystems with robust sequestration potential, where economic activities generate relatively low emissions, thereby functioning as the region’s critical ecological reserve.

6.2. Policy Implications

Based on the results of this research, the following policy recommendations are proposed:

(1) The carbon sink system of resource-based cities in Anhui Province is mainly composed of forest land, while the main carbon source systems include cultivated land and construction land. Therefore, it is necessary to reduce carbon emissions and enhance carbon sink levels through measures such as protecting forest resources, optimizing farming methods, and rationally planning construction land: Protect existing forest resources, strictly implement the quota cutting system, and reduce the occupation of forest land to ensure the stability of the forest area. Expand the forest area, carry out artificial afforestation and degraded forest restoration projects in major carbon sink areas such as northern Anhui to build a more powerful carbon sequestration ecosystem. Take various measures to reduce carbon emissions of cultivated land, such as reducing the usage of fertilizers and pesticides, increasing the recovery rate of discarded agricultural films and pesticide packaging, and enhancing the comprehensive utilization rate of straw. Enhance the carbon sequestration potential of crops by adopting precise fertilization, water-saving irrigation, straw returning to the fields, and other techniques. Strengthen urban space management and promote the intensive and efficient use of land. Strictly control the occupation of carbon sink forests and high-quality cultivated land by construction land. Scientifically plan the utilization of urban land, control the scale of new construction land, and actively renovate areas such as coal mining subsidence zones and abandoned industrial and mining lands. Expand the green space area in construction land, promote the transformation of unused and idle land into land types with stronger carbon sequestration functions, such as forest land and grassland, and enhance the regional ecological carbon sequestration capacity.

(2) In the study area, the spatial distribution of carbon emissions and carbon sinks is uneven. Therefore, a precise emission reduction strategy based on zoning and classification is needed to alleviate the problem of spatial mismatch. High-emission core zones (Chuzhou, Suzhou, Bozhou): Enforce dual control over both total emissions and intensity. Prioritize technological transformation of traditional industries like chemicals and coal power towards intensification and environmental friendliness. Transition demonstration zones (Huaibei, Huainan, Tongling, Ma’anshan): Promote the upgrading and greening of industries. Strengthen the reuse and regional collaborative planning of land. Prioritize the planning of low-carbon projects as new economic growth points. High-carbon sink conservation zones (Xuancheng, Chizhou): Balance conservation and development. Establish ecological carbon sink compensation mechanisms, strictly protect forest and wetland resources, and prevent expansion of construction land from encroaching on carbon sink spaces. Encourage the development of industries such as ecotourism and understory economy, while exploring carbon sink trading mechanisms, in order to transform ecological advantages into economic benefits.

(3) At present, the agglomeration of high-carbon-emission areas has significantly increased, while low-carbon-emission areas have become more dispersed. The spatial distribution of carbon sequestration areas shows the characteristic of “strong in the south and weak in the north, with a fixed pattern”. For areas with high carbon emissions, stricter control over carbon emissions and intensity should be implemented. Efforts should be made to promote the transformation of the energy structure, develop clean energy, and carry out energy-saving renovations. For low-emission zones, it is necessary to plan the layout of green and low-carbon industries in advance and restrict high-energy consumption and high-carbon-emission projects. In the high-carbon-sink areas in the south, strict measures for ecosystem protection should be implemented to consolidate and enhance the existing carbon sequestration capacity of the ecosystem. In the low-carbon-sink areas in the north, in addition to promoting ecological restoration and landscape projects, efforts should also be made to develop technologies such as carbon capture, utilization, and storage. Furthermore, it is also extremely necessary to establish a cross-city ecological compensation and cooperative governance mechanism based on spatial mismatch. In regions with high emissions but low carbon sinks, economic compensation can be provided to regions with low emissions but high carbon sinks through means such as fiscal transfer payments and the purchase of carbon sink indicators, so as to internalize ecological externalities.

(4) The LMDI analysis results indicate that the level of economic development and energy consumption density are the main driving factors for the increase in carbon emissions, while reducing carbon emission intensity and improving the economic efficiency of land utilization are the main reasons for the reduction in carbon emissions. Based on these key influencing factors, the corresponding countermeasures can be drawn as follows: On one hand, the economic structure should be optimized, and the industrial green transformation should be promoted to reduce the proportion of industries with high energy consumption and high carbon emissions. It is also necessary to promote energy-saving technologies and strengthen supervision over key energy-consuming industries. On the other hand, these resource-based cities should further transform the way of energy utilization and increase the proportion of clean energy, such as solar and wind power. They should also promote the application of technologies like carbon capture, utilization, and storage in high-carbon emission industries. At the same time, it is necessary to optimize the urban spatial layout, implement an intensive urban land use model, and enhance the economic output per unit of land and energy utilization efficiency.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr13124047/s1, Table S1: Contributions of Various Driving Factors Based on the LMDI Model; Table S2: Forest Land Area in Resource-Based Cities of Anhui Province from 2000 to 2020 (million m2).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.B.; methodology, K.B.; software, R.X.; validation, K.B., and R.X.; formal analysis, S.Z.; investigation, K.B.; resources, K.B.; data curation, R.X.; writing—original draft preparation, K.B.; writing—review and editing, R.X.; visualization, S.Z.; supervision, K.B.; project administration, R.X.; funding acquisition, K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Research Start-up Funding for Introduced Talents of Anhui University of Science & Technology (NO.2022yjrc16); and the University Research Projects of the Education Department of Anhui Province (NO.2022AH050795).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Seto, K.C.; Churkina, G.; Hsu, A.; Keller, M.; Newman, P.G.; Qin, B.; Ramaswami, A. From low-to net-zero carbon cities: The next global agenda. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 377–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziozias, C.; Kontogianni, E.; Anthopoulos, L. Carbon-neutral city transformation with digitization: Guidelines from international standardization. Energies 2023, 16, 5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.W.; Wang, F.; Tan, X.J.; Sun, Y.; Chen, T.; Rui, D.L. Research Progress on the Path to Enhancing Carbon Sink Capacity in Urban Ecological Spaces. Environ. Pollut. Control 2025, 47, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Cao, M.Y.; Wang, W.Y.; Zhang, T.Y. Spatial Evolution and Scenario Simulation of Carbon Metabolism in Coal-Resource-Based Cities Towards Carbon Neutrality: A Case Study of Jincheng, China. Energies 2025, 18, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shen, Y.; Rong, Y.J.; Fu, X.; Tang, M.F.; Deng, H.B.; Wu, G. Industrial characteristics and drivers of urban carbon cycle: From an analysis of typical cities in China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Yang, L. Research on Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality Scenarios in the Yangtze River Delta Region. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2024, 33, 2260–2270. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Yang, M.; Li, Y. Coordinated effect of green expansion and carbon reduction: Evidence from sustainable development of resource-based cities in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.L.; Gao, B.R.; Tan, Y.; Xiao, K.Y.; Zhai, Y.J. Resource-based transformation and urban resilience promotion: Evidence from firms’ carbon emissions reductions in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 468, 143118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.M.; Lin, C.Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Wang, S.W. Environmental Regulation, Factor Marketisation Allocation and Carbon Emissions Performance: Empirical Evidence from Resource-Based Cities in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Li, P.; Roosli, R.B.; Liu, S.B.; Zhang, X.P.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wu, L.; Yao, H. Carbon emission characteristics of resource-based cities in China. Iran. J. Sci. Technol.-Trans. Civ. Eng. 2022, 46, 4579–4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Xu, Z.J.; Yue, X.; Yang, L.Q.; Wang, R.J.; Chen, Y.L.; Ma, H.Q. Carbon emission scenario simulation and policy regulation in resource-based provinces based on system dynamics modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 460, 142619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Z.; Sun, X.; Zhu, Q.K.; Shang, Y.T. A Review of Quantification Methods for Carbon Dioxide Emissions in China. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 33, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Yue, S.; Chen, H. Carbon emission efficiency of China’s industry sectors: From the perspective of embodied carbon emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 283, 124655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.K.; Qi, S.J.; Jrade, A. Simulation and Assessment of Whole Life-Cycle Carbon Emission Flows from Different Residential Structures. Sustainability 2016, 8, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, T.Q.; Zhang, P.Y.; Zhu, H.R.; Jiang, L.; Li, Y.Y.; Liu, Z.Y. Spatial correlation evolution and prediction scenario of land use carbon emissions in China. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 71, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qiu, J.J.; Wang, L.G.; Tang, H.J.; Li, C.S.; Van Ranst, E. Modelling impacts of alternative farming management practices on greenhouse gas emissions from a winter wheat-maize rotation system in China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010, 135, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, R.; Zhang, Z.X.; Zhang, F.Y.; Tian, J.X.; Zhu, B.; Zhu, M.; Wang, Y.M. Spatiotemporal Variation of Forest Carbon Storage and Its Driving Factors in the Yangtze River Basin. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 27, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.Y.; Tu, J.J.; Xiao, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y. Fine-scale Accounting of Carbon Budget and Monitoring of Driving Factors in Territorial Space of Chengdu-Chongqing Urban Agglomeration. J. Nat. Resour. 2025, 40, 1294–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Du, Y.; Lv, T. Land Use Carbon Budget and Carbon Balance Zoning Based on Social Network Analysis: A Case Study of 84 Districts and Counties in the Weihe River Basin. China Land Sci. 2025, 39, 114–126. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=X84Xx1LLloJ90izrMsaDVhNHTkRW_QA3PKhQjvoYr0m6WAZFWwndlGVdd5FYOlh6Bd69zUM-0JTMR14aWyQC3KIELuOuJpEU-WZu5yG0H9ejDUBxSi3HFsOQ3gkFPxJzLJU8HB29cK4uF4iRFehhzrxndKtAiBLwcZEQCHsmbljRBNr7U6FFGA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Yang, Y.; Su, Y. Spatiotemporal Differentiation Characteristics of Carbon Budget and Driving Factors of Carbon Balance in Guanzhong Plain Urban Agglomeration. China Environ. Sci. 2025, 45, 4034–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, M.; Jorgensen, S.E.; Pulselli, F.M.; Marchettini, N.; Bastianoni, S. Modelling the carbon cycle of Siena Province (Tuscany, central Italy). Ecol. Model. 2012, 225, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.Z.; Xu, J.H.; Zhao, T. Spatiotemporal Patterns and Heterogeneity of Carbon Emissions in the Yangtze River Basin Based on Nighttime Light Data. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2024, 33, 2004–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.Q.; Hao, J.M.; Zhang, J.Y.; Wu, Z.H.; Sun, Y.H. Calculation and Scenario Prediction of Land Use Carbon Emissions in Quzhou County. J. China Agric. Univ. 2024, 29, 160–175. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=X84Xx1LLloL6Zc3PWKaw95Xz3-sqWnkFMopL7yhTUsTMsp5UeYvP_mEyM0Us-_ICWNxbczNOv6apaI8lDMWVHc-6VeUfj0PiQ_IAytexqaMHgIUM9w-xDtN-Z9KQc5JCqkNixPKcNSMUv6r5AKepoB-DF2_uitWpWCOdyZVaS-SV6VGx9o7kXA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Xu, S.C.; He, Z.X.; Long, R.Y. Factors that influence carbon emissions due to energy consumption in China: Decomposition analysis using LMDI. Appl. Energy 2014, 127, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.Q.; Su, D.H.; Shi, S.X. Carbon Peak Prediction in Fujian Province Based on STIRPAT and CNN-LSTM Hybrid Model. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Xia, N.; Tang, Y.Q.; Sun, S.F.; Xu, Z.J.; Ma, Y.G. Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Land Use Carbon Emissions in China at Different Spatial Scales. J. Environ. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Du, L. Assessment Framework of Provincial Carbon Emission Peak Prediction in China: An Empirical Analysis of Hebei Province. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2019, 28, 3753–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.S.; Yang, X.Y.; Chen, L.G.; Liu, L.C.; Wang, C.Y. Land use carbon emissions in China’s coal-resource-based cities: Quantitative measurement and drivers analysis. Urban Clim. 2025, 64, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, M.X.; Tang, Z.P.; Mei, Z.A. Urbanization, Land Use Change, and Carbon Emissions: Quantitative Assessments for City-Level Carbon Emissions in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 66, 102701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Y.; Lin, Y.; Chen, L.G.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.Q.; Wang, X.Y. Analysis of Land Use Carbon Emissions and Influencing Factors in Provincial Urban Agglomerations: A Case Study of Jiangsu Province. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2025, 34, 1972–1986. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=X84Xx1LLloKhsE-Ojd5Tibvq7-19mqj46uL9TKjT8cisnrY0s2xF8T03ciVtFw2vbfPmgKO3jxwKlTrI4ACnp0lDjhd579kVmwZjaJBSQ4bRnc-LyYE4Nqs_njUUbys5HpapSRJyfmsEpH9_439EjULDSldQFZwldm1KpEngH0LoDMpxkOqgVA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Shen, R.; Wang, L.; Jiang, Y.H.; Yang, Y.N.; Wang, Y. The spatio-temporal differentiation of carbon budget and carbon balance zoning in the Yangtze River Delta region. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 48, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.C.; Mei, Z.X.; Ma, J.J.; Wang, X.Y. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Influencing Factors of Land Use Carbon Emissions in Guangzhou City. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 31, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.Y.; Sun, X.J.; Yu, F.B.; Yang, L.S. Spatial Correlation Pattern and Influencing Factors of Carbon Productivity in China’s Planting Industry. China Pop. Res. Environ. 2020, 30, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.X.; Liu, X.R.; Shi, X.C.; Cai, C.M. Spatiotemporal Differences and Carbon Compensation of Provincial Carbon Emissions in China Based on Land Use Change. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 39, 1955–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, T.; Ma, Y.; Cai, W.; Liu, B.; Mu, L. Will the urbanization process influence the peak of carbon emissions in the building sector? A dynamic scenario simulation. Energy Build. 2020, 232, 110590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, B.W. LMDI decomposition approach: A guide for implementation. Energy Policy 2015, 86, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]