Abstract

This study investigates the influence of Cr2O3-bearing fluxes on the transfer behavior of O and Cr during the submerged arc welding process. A series of fluxes with varying Cr2O3 content are prepared and applied in submerged arc welding. A cross-zone model is developed to separately evaluate the transfer of O and Cr in both droplet and weld pool zones. The results reveal significant O enrichment in the droplet zone due to the decomposition of Cr2O3 under arc heating, followed by deoxidation in the weld pool. Cr transfer is found to be inhibited by the high oxygen potential in the droplets and further affected by evaporation loss. A comparison of predicted ΔCr values shows that the gas–slag–metal equilibrium model overestimates Cr transfer level, while the cross-zone model provides predictions more consistent with experimental results. This study highlights the critical role of Cr2O3 in regulating transfer behaviors O and Cr and provides valuable insights for flux design aimed at achieving precise compositional control and improved weld quality in welding applications.

1. Introduction

Submerged arc welding (SAW) is recognized as a highly flexible and efficient automated arc welding process. SAW is extensively utilized in heavy industrial fields due to its remarkable deposition rate and operational stability [1,2,3]. During the SAW process, intense chemical interactions occur among different consumables, including the slag, base metal (BM), molten droplets, etc. [4,5,6,7]. Given the significance of weld metal (WM) composition control in achieving high-quality welds, it is essential to understand the underlying mechanisms that govern compositional variations in the submerged arc welded metal [8,9,10,11].

The flux performs several essential functions for SAW [12]. Apart from stabilizing the plasma and facilitating slag formation and detachment, the WM composition is also governed by the flux through complex chemical interactions with the molten pool and arc plasma [13,14,15,16]. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the elemental transfer mechanisms during the SAW process is vital for accurate compositional control, which in turn governs submerged arc welded metal’s mechanical properties [17,18].

Cr2O3 is an essential component of flux, particularly in applications where enhanced corrosion resistance and hardness of the WM are required [19,20,21,22,23,24]. To investigate the effects of Cr2O3 on element transfer behavior during welding, several studies have been conducted. Mitra et al. [19] performed SAW using Cr2O3-containing flux and conducted thermodynamic analysis of the associated chemical reactions. Quintana et al. [25] examined the transfer efficiency of alloying elements during SAW with Cr2O3-bearing flux. Zhang et al. [26], on the other hand, designed a series of Cr2O3-containing fluxes and developed a method capable of constraining the transfer behavior of essential elements.

However, previous studies on Cr2O3-bearing fluxes have mainly concentrated on the weld pool zone. Although these studies conducted a systematic quantitative analysis of element transfer behavior, the role of molten droplets in influencing element transfer during the SAW process has been overlooked [19,26,27].

The contributions of SiO2 and FeO to the O potential have been well documented, whereas the role of Cr2O3 has received far less attention. Cr2O3 is of particular interest because its high-temperature decomposition can generate lower-valence chromium oxides (e.g., CrO) and release O2, thereby producing an O potential comparable to—or even higher than—that of SiO2 or FeO. As a result, Cr2O3 can exert a substantial influence on the O potential under SAW conditions [12,19,28,29].

The previous model only considered the weld pool zone, which led to considerable prediction errors [7]. In contrast, the cross-zone model proposed in this study accounts for the significant O enrichment in the droplet zone and its influence on element transfer, while also considering possible metal evaporation during the SAW process.

In the present study, a series of fluxes are prepared with progressively increasing Cr2O3 content. By quantifying the transfer behavior of elements in different zones and incorporating thermodynamic simulations, this work aims to comprehensively elucidate the mechanisms by which Cr2O3 in the flux affects elemental transfer, with particular attention to O and Cr elements, thereby enhancing the understanding of its role in controlling WM composition and guiding the optimization of flux design for improved weld quality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Flux Preparation

For each designed flux composition, 1 kg of analytical-grade powders was weighed according to the formulations shown in Table 1; apart from Cr2O3, CaF2 was introduced as an oxygen-free non-oxide diluent; the powders were then thoroughly blended in a V-type mixer operating at 0.5 Hz for one hour; after mixing, a 150 g sodium silicate solution was added as a binder, introducing SiO2 and Na2O, which improve slag removal and arc stability [26]. The bonded mixture was subsequently pelletized and dried in a muffle furnace at 973 K for three hours; finally, the sintered material was crushed and sieved to obtain particles between 14 and 100 mesh [26,30]. It should be noted that, in this study, the term flux refers to the raw material before SAW, whereas slag denotes the molten or solidified flux formed during or after the SAW process [12]. The flux samples were characterized for their elemental composition through X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis with an S4 Explorer spectrometer; the analytical compositions of the fluxes are presented in Table 1, while the procedures for determining the chemical compositions of the metal have been described in detail in previous work [26,31].

Table 1.

Measured compositions of fluxes (wt pct) [26].

The ΔO and ΔCr values were obtained under stable welding conditions after the submerged arc welded metal composition reached a steady state [30]. Because these values were measured after the metal composition reached a stable state, they reflect the steady elemental transfer of O and Cr under controlled welding conditions. As a result, repeated experiments and statistical indicators (e.g., standard deviation or standard error) are not applicable, which is consistent with previous studies in this field [1,12,26,28,32]. A single arc heat input and one BM grade (Q345A) were used to avoid adding unnecessary variables. This allows the study to focus purely on the influence of Cr2O3 on the transfer behavior of O and Cr, which is the major objective. This approach aligns with established practices in related studies [1,12,26,28,32].

2.2. Welding Experiment

The base material used in this study was Q345A, a widely applied low-alloy structural steel. Bead-on-plate welding was conducted via a single-pass, double-electrode SAW process (Lincoln Electric Power Wave AC/DC 1000 SD, Lincoln Electric, Cleveland, OH, USA) under a total heat input of 60 kJ/cm. The current and voltage settings were DC 850 A/32 V for the leading electrode and AC 625 A/36 V for the trailing one, with a travel velocity of 500 mm/min.

Specifically, 60 kJ/cm was chosen because it represents a typical high heat-input level in SAW, and Q345A is widely used and compositionally stable, making it a representative BM [12,26,32]. Using one heat input and one BM grade reduces unnecessary variability and allows the essential thermodynamic trends to be identified more clearly, which is appropriate for generalizing the underlying mechanisms [19,32].

2.3. Chemical Composition Analysis

The concentrations of metallic elements were measured using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), while the O content was analyzed with a LECO analyzer (LECO Corporate, St. Joseph, MI, USA). The chemical compositions of both the electrode and BM are listed in Table 2. Data on metal content measurements can be found in our previous publication [26]. The measured Δ value (the contribution of the flux to elemental transfer) for O and Cr is summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Measured chemical compositions of BM and electrode (wt pct) [26].

Table 3.

Quantified Δ values of O (ppm) and Cr (wt pct) [26].

3. Thermodynamic Calculation

In our previous work, a thermodynamic analysis of SAW using Cr2O3-bearing fluxes was conducted [26]. However, previous study focused solely on the local thermodynamic behavior within the weld pool zone, neglecting the reactions occurring in the molten droplet zone. Furthermore, when quantifying element transfer level, the prior analysis only considered compositional changes in the weld pool relative to the original materials (i.e., BM and electrode), which may lead to misinterpretation of the underlying transfer mechanisms.

To address the limitations of previous studies, the SAW process will be simulated using our previously proposed “cross-zone model.” This model enables separate quantification of element transfer behavior in both the droplet and weld pool zones, with particular attention to O and Cr elements [32].

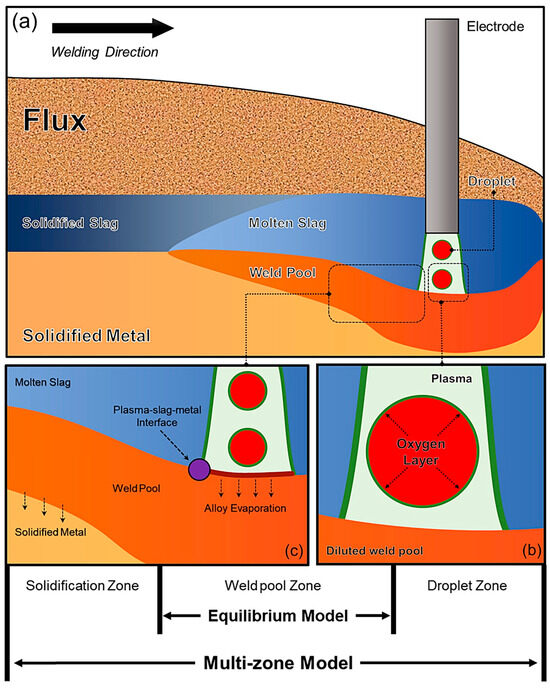

Figure 1 illustrates the essential reaction interfaces involved in the metallurgical process of SAW process. A comparison reveals that conventional thermodynamic equilibrium models consider only the localized equilibrium within the weld pool, whereas the multi-zone model accounts for cross-zone element transfer, particularly the significant O enrichment in the droplets under the arc [32].

Figure 1.

Reaction zones influencing WM content: (a) Schematic diagram of the SAW process; (b) Chemical reactions in the droplet zone; (c) Chemical reactions in the weld pool zone [32].

In the present work, the thermodynamic modeling was carried out using FactSage 7.3, a software platform grounded in the CALPHAD methodology [33,34]. This program integrates several functional modules that enable the processing of thermodynamic information from a variety of databases. For phase-specific modeling, the Fstel, FactPS, and FToxide modules were applied to represent steel phases, gaseous phases, and slag or flux phases, respectively [33,34]. Chemical equilibrium states were calculated using the Equilib module, which estimates the distribution of chemical species when the system reaches thermodynamic equilibrium [32].

In thermodynamic studies of the SAW process, researchers commonly use the so-called “effective equilibrium temperature” to perform calculations [1,12]. This temperature does not correspond to the actual measured equilibrium temperature in SAW but rather represents the temperature at which the experimental mass action index equals the equilibrium constant. In the present study, the SAW process temperature for the droplet zone and weld pool zone was selected based on previous literature [1,12,32].

3.1. Droplet Zone

Equilib module of FactSage was employed to conduct the thermodynamic modeling subject to the Droplet Zone. The databases FToxid, Fstel, and FactPS were selected to represent the relevant phases [34]. In the thermodynamic calculations, the molten slag and steel systems were represented using the ASlag-liq (all oxides), S (FToxid-SLAGH), and LIQUID (Fstel-Liqu) solution phases [32].

- The equilibrium temperature in the submerged arc welding (SAW) process was taken as approximately 2500 °C, corresponding to the typical temperature of the arc plasma.

- The chemical composition of the BM served as the input for the metallic phase.

- An equilibrium simulation was carried out using Fe and O as the representative input elements to estimate the O concentration in the droplet zone. During this calculation, the O partial pressure PO2 (The O2 partial pressure obtained from the previous step) is fixed according to the values listed in Table 4. The resulting O concentrations and simulated PO2 values are also presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Simulated results for the oxygen partial pressure (PO2, atm) and oxygen content (O, ppm) in the droplet.

Table 4. Simulated results for the oxygen partial pressure (PO2, atm) and oxygen content (O, ppm) in the droplet.

- 4.

- It is well known that metal evaporation tends to occur during the SAW process due to the presence of arc plasma. As noted by Kou [13], thermodynamic analysis alone cannot fully predict such losses. Given that detailed metal evaporation models are still limited in the literature, a recent empirical approach was applied to estimate metal evaporation. As such, the relationships used in Equations (1) and (2) were adopted here to approximate the evaporation behaviors of Mn and Si under high-temperature SAW conditions, which is consistent with previous papers [32,35]. The extent of metal evaporation was evaluated using Equations (1) and (2), as proposed by Zhu et al. [36], where η represents the burn-off ratio of the metal subject to the droplet zone.

- 5.

- Based on the above calculations, the metal input composition for thermodynamic simulation of the weld pool zone is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5. Data of nominal compositions used for modeling.

Table 5. Data of nominal compositions used for modeling.

3.2. Weld Pool Zone

After completing the simulation of the droplet zone, the weld pool is subsequently modeled. At this stage, MN is introduced to represent the dilution effect of the droplet on the weld pool, as described in our previous work. MN refers to the nominal composition, which reflects dilution effects of the droplet and weld pool [1,30,37]. The gas–slag–metal equilibrium was simulated using the Equilib module of FactSage considering mass ratio of slag to WM [26]:

- The thermodynamic databases FToxid, Fstel, and FactPS were applied in this work.

- The molten slag and steel systems were described through the solution models ASlag-liq (all oxides), S (FToxid-SLAGA), and LIQUID (Fstel-Liqu).

- The equilibrium temperature in SAW of 2000 °C was set. All other settings were kept consistent with our previous work.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Transfer of O

In submerged arc welding, O plays a key role in determining the WM microstructure and its resulting mechanical properties [1,12,28,30]. It is well known that excessive O reduces toughness and hardenability, whereas insufficient O suppresses acicular ferrite formation, resulting in degraded toughness [12].

Traditional basicity index model and gas-slag-metal model consider only chemical interactions in the weld pool zone [12]. However, numerous experimental studies have shown that the O content is significantly higher in the molten droplets. For instance, Lau et al. [14,15] conducted extensive work demonstrating that O reaches its peak concentration in the droplets, which are subsequently diluted by the BM during welding.

In the following section, the transfer behavior of O across different zones is quantitatively analyzed. The calculation is based on standard industry formulas. Equations (3) and (4) are applied to evaluate the O transfer level, where MDO and MWO correspond to the O levels within the droplet and weld pool zones. ΔDO refers to the amount of O transferred in the droplet zone and ΔWO denotes the transfer occurring in the weld pool zone. MNO means the nominal composition of O element [35].

Table 6 shows the data of ΔDO and ΔWO.

Table 6.

Simulated transfer behavior of O (ppm) subject to droplet zone and weld pool zone.

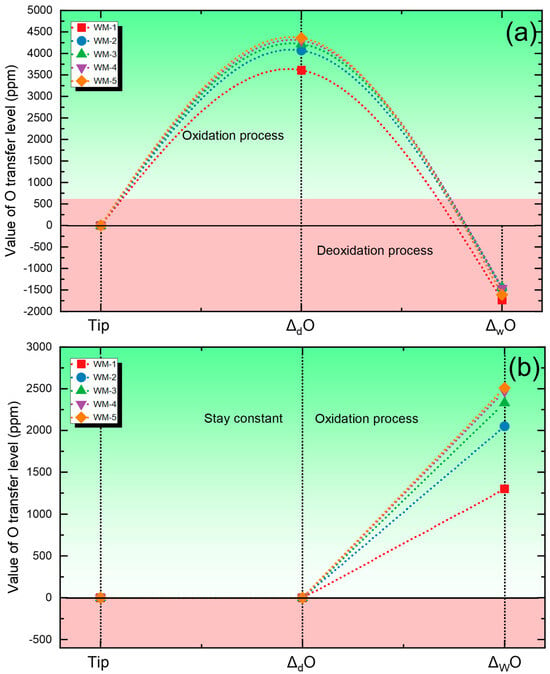

Figure 2 presents the quantified levels of O transferred across different zones. In Figure 2a, the predicted values are obtained using the multi-zone model. A considerable transfer of O into the metal occurs in the droplet zone, after which deoxidation takes place in the weld pool. In contrast, Figure 2b shows the results predicted by the equilibrium-based model, which does not account for the strong oxidation effect occurring in the droplet zone. This model assumes that oxidation takes place solely within the weld pool zone. Tip means the tip of electrode.

Figure 2.

Cross-zone transfer behavior of O: (a) Predicted O transfer using the multi-zone model; (b) Predicted O transfer using the conventional gas–slag–metal equilibrium model [26].

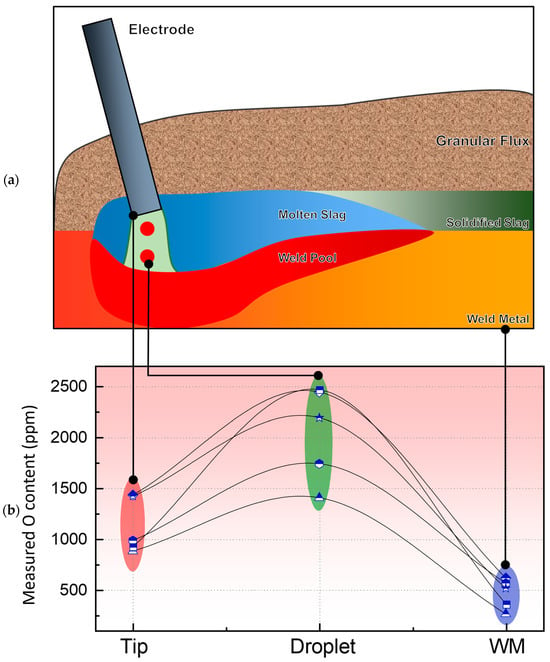

In fact, Lau et al. [14,15] experimentally confirmed the high O content in droplets by extracting and analyzing them. Similarly, Sengupta et al. [1] emphasized the elevated O levels in droplets in their review. Figure 3 describes the typical cross-zone transfer behavior of O. A comparison between Figure 2 and Figure 3 clearly indicates that Figure 2a provides a more realistic representation of the O transfer pathway during the SAW process.

Figure 3.

Variation of O content at various stages of the SAW process (ppm): (a) Schematic diagram of the SAW; (b) Typical cross-regional variation of O [1,14,15,38].

Among various arc welding techniques, SAW exhibits a relatively high degree of O enrichment due to the involvement of flux. According to Chai et al. [5,28,39], The high temperature of the welding arc causes the oxides in the flux to decompose, releasing O2, significantly increasing the O content in the metal. Based on the thermodynamic modeling, Cr2O3 and CrO are identified as the primary chromium-containing oxides in the slag. Therefore, it can be inferred that Cr2O3 decomposes into CrO and O2 under arc heating, leading to a substantial rise in O content within the droplets [28].

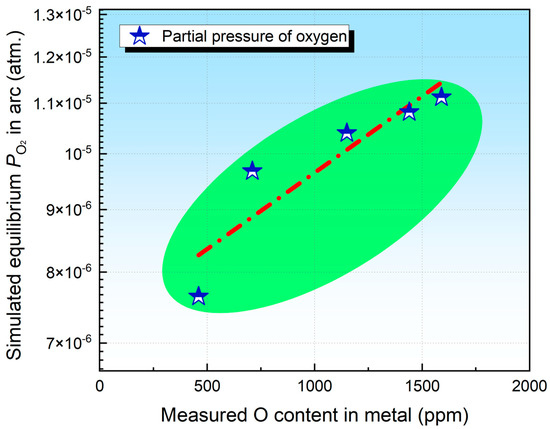

Lau et al. [14,15] further suggested that the partial pressure of O2 within the arc reflects the O potential of the flux-i.e., the flux’s capacity to supply O to the metal. To validate this hypothesis, a comparison was made between the measured O content and the simulated O partial pressure. As shown by Figure 4, the O2 partial pressure increases with rising Cr2O3 content in flux.

Figure 4.

Illustration showing the correlation between O content in the WM and the partial pressure of O2 (ppm).

4.2. Transfer of Cr

The subsequent discussion focuses on the transfer characteristics of chromium. According to the preceding analysis, chromium transfer in Cr2O3-containing fluxes is mainly controlled by Reactions (6) and (7) [19,26].

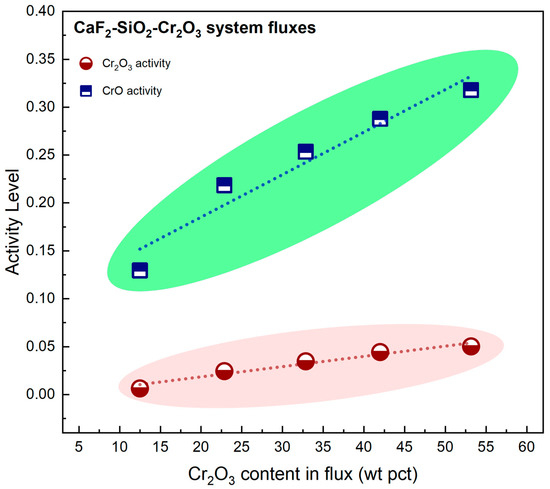

Figure 5 shows the relationship between Cr2O3 content in the flux and the activities of Cr2O3 and CrO. Figure 5 illustrates that the activities of Cr2O3 and CrO both rise as the Cr2O3 content in the flux increases.

Figure 5.

Variation of chromium oxide activity as a function of Cr2O3 content in the flux.

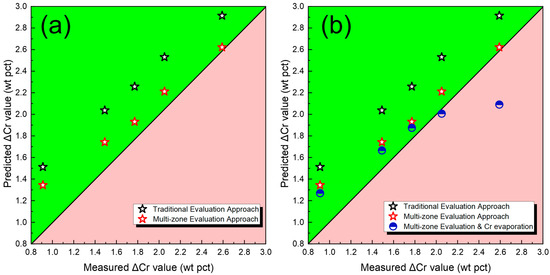

Nevertheless, focusing solely on oxide activity cannot adequately account for the chromium transfer behavior [21,22,23]. Given the relatively high O potential of Cr2O3 and the increased O concentration in the droplet region, chromium transfer may be partially hindered. Figure 6a displays the predicted ΔCr values derived from both the traditional gas–slag–metal equilibrium model and the proposed cross-zone approach. The black symbols denote the ΔCr results from the conventional model, whereas the red symbols correspond to those obtained by the cross-zone model. When the O enrichment in the droplet is considered, the predicted ΔCr values exhibit markedly better agreement with the experimental data.

Figure 6.

ΔCr predicted by different models. (a) Predicted ΔCr via traditional and multi-zone models; (b) Predicted ΔCr via traditional model, multi-zone model, and multi-zone model considering evaporation of Cr.

In addition to thermodynamic factors, Cr evaporation also occurs during the SAW process [19,27]. This phenomenon is closely related to the interaction between the high-temperature arc and the molten metal. Currently, no model is available to accurately predict the amount of Cr evaporation, and the underlying mechanism remains not fully understood. In this study, the evaporation loss of Cr was further estimated based on mass balance calculations to refine the prediction of ΔCr [26]. As shown in Figure 6b, the accuracy of the predicted ΔCr values is further improve, except the level of Cr2O3 is higher than 50 wt pct. Therefore, future work should focus on developing a more advanced metal evaporation model to further improve the overall accuracy of the simulation [9,40]. In addition, the model should be further optimized to clarify the relationships between the thermodynamic model and element transfer, element evaporation, and the thermodynamic behavior during solidification, thereby improving the model’s accuracy and general applicability [41,42,43,44,45,46].

5. Conclusions

This work investigates the impact of Cr2O3-containing fluxes on the elemental transfer of O and Cr during the SAW process. The following conclusions can be drawn:

- A multi-zone thermodynamic model is established to simulate element transfer in the droplet and weld pool zones. Compared to the conventional gas–slag–metal equilibrium model, this approach more accurately reflected the actual distribution and evolution of O and Cr during welding.

- The results revealed that O is significantly enriched in the molten droplet zone due to the decomposition of Cr2O3 under high-temperature arc conditions. This O enrichment leads to subsequent deoxidation reactions in the weld pool, which were well captured by the proposed cross-zone model.

- The transfer behavior of Cr was found to be strongly influenced by both thermodynamic factors and evaporation Cr loss. While the activities of Cr2O3 and CrO increase with rising Cr2O3 content in the flux, the accompanying increase in O potential within the droplet zone tends to inhibit Cr transfer into the weld metal. Incorporating evaporation loss into the cross-zone model further improved the accuracy of ΔCr prediction.

It is noted that the contribution of Cr evaporation is estimated from mass balance and empirical formulas rather than direct measurements; therefore, it should be regarded as a probable (or significant) contributor rather than a definitively established mechanism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z., J.F. and D.Z.; funding acquisition, J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Suqian Sci&Tech Program (Grant No. K202519), Research Project on Industry-Education-Science Integration by the China Mechanical Engineering Education Association (Grant No. ZJJX24CY097), Suqian City Guiding Science and Technology Project (Grant No. Z2024011), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 50474085).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sengupta, V.; Havrylov, D.; Mendez, P. Physical Phenomena in the Weld Zone of Submerged Arc Welding—A Review. Weld. J. 2019, 98, 283–313. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, L.; Chhibber, R.; Kumar, V.; Khan, W.N. Element Transfer Investigations on Silica-Based Submerged Arc Welding Fluxes. Silicon 2023, 15, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.V.; Trinh, N.Q.; Tashiro, S.; Suga, T.; Kakizaki, T.; Yamazaki, K.; Lersvanichkool, A.; Murphy, A.B.; Tanaka, M. Individual Effects of Alkali Element and Wire Structure on Metal Transfer Process in Argon Metal-Cored Arc Welding. Materials 2023, 16, 3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, C.; Eagar, T. Prediction of Weld-metal Composition during Flux-shielded Welding. J. Mater. Energy Syst. 1983, 5, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.; Eagar, T. Slag-metal Equilibrium during Submerged Arc Welding. Metall. Trans. B 1981, 12, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.; Liu, S.; Frost, R.; Edwards, G.; Fleming, D. Nature and Behavior of Fluxes Used for Welding. ASM Int. ASM Handb. 1993, 6, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua-Mercado, A.M.; López-Hirata, V.M.; Muñoz, M.L.S. Influence of the Chemical Composition of Flux on the Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Submerged-Arc Welds. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2005, 169, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Fang, T.; Zhao, L.; Cui, H.; Lu, F. Effect of Trace Element on Microstructure and Fracture Toughness of Weld Metal. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2020, 33, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Artinov, A.; Bachmann, M.; Rethmeier, M. Numerical and Experimental Investigation of Thermo-Fluid Flow and Element Transport in Electromagnetic Stirring Enhanced Wire Feed Laser Beam Welding. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 144, 118663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Shandley, R.; Kumar, A. Optimization of Agglomerated Fluxes in Submerged Arc Welding. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 5049–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Khan, Z.A.; Siddiquee, A.N.; Maheshwari, S. Effect of CaF2, FeMn and NiO Additions on Impact Strength and Hardness in Submerged Arc Welding Using Developed Agglomerated Fluxes. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 667, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shao, G.; Fan, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, D. A Review on Parallel Development of Flux Design and Thermodynamics Subject to Submerged Arc Welding. Processes 2022, 10, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, S. Welding Metallurgy, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 22–122. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, T.; Weatherly, G.; McLean, A. Gas/metal/slag Reactions in Submerged Arc Welding Using CaO-Al2O3 Based Fluxes. Weld. J. 1986, 65, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, T.; Weatherly, G.; McLean, A. The Sources of Oxygen and Nitrogen Contamination in Submerged Arc Welding using CaO-Al2O3 Based Fluxes. Weld. J. 1985, 64, 343–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kanjilal, P.; Pal, T.; Majumdar, S. Combined Effect of Flux and Welding Parameters on Chemical Composition and Mechanical Properties of Submerged Arc Weld Metal. J. Mater. Process. Technol 2006, 171, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, S.; Chhibber, R.; Mehta, N. Effect of Flux Constituents and Basicity Index on Mechanical Properties and Microstructural Evolution of Submerged Arc Welded High Strength Low Alloy Steel. Mater. Sci. Forum 2013, 738–739, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viano, D.; Ahmed, N.; Schumann, G. Influence of Heat Input and Travel Speed on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Double Tandem Submerged Arc High Strength Low Alloy Steel Weldments. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2000, 5, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, U.; Eagar, T. Slag Metal Reactions during Submerged Arc Welding of Alloy Steels. Metall. Trans. A 1984, 15, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, U. Kinetics of Slag Metal Reactions During Submerged Arc Welding of Steel. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, U.; Eagar, T. Slag-Metal Reactions During Welding: Part II. Theory. Metall. Trans. B 1991, 22, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, U.; Eagar, T. Slag-Metal Reactions During Welding: Part I. Evaluation and Reassessment of Existing Theories. Metall. Trans. B 1991, 22, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, U.; Eagar, T. Slag-Metal Reactions During Welding: Part III. Verification of the Theory. Metall. Trans. B 1991, 22, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, U.; Sutton, R.; Eagar, T. Comparison of Theoretically Predicted and Experimentally Determined Submerged Arc Weld Deposit Compositions. Metall. Trans. B 1983, 14, 510–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, R.; Cruz, A.; Perdomo, L.; Castellanos, G.; García, L.L.; Formoso, A.; Cores, A. Study of the Transfer Efficiency of Alloyed Elements in Fluxes during the Submerged Arc Welding Process. Weld. Int. 2003, 17, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, Q. Probing Element Transfer Behavior During the Submerged Arc Welding Process for CaF2–SiO2–Na2O–Cr2O3 Agglomerated Fluxes: A Thermodynamic Approach. Processes 2022, 10, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block-Bolten, A.; Eagar, T.W. Metal Vaporization from Weld Pools. Metall. Trans. B 1984, 15, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.; Eagar, T. Slag-Metal Reactions in Binary CaF2–Metal Oxide Welding Fluxes. Weld. J. 1982, 61, 229–232. [Google Scholar]

- Indacochea, J.E.; Blander, M.; Christensen, N.; Olson, D.L. Chemical Reactions during Submerged Arc Welding with FeO-MnO-SiO2 Fluxes. Metall. Trans. B 1985, 16, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalie, C.A.; Olson, D.L.; Blander, M. Physical and Chemical Behavior of Welding Fluxes. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1986, 16, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Chhibber, R. Design of TiO2–SiO2–MgO and SiO2–MgO–Al2O3-Based Submerged Arc Fluxes for Multipass Bead on Plate Pipeline Steel Welds. J. Press. Vessel Technol. 2019, 141, 041402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, P.; Zhang, D. Advancing Manganese Content Prediction in Submerged Arc Welded Metal: Development of a Multi-Zone Model via the Calphad Technique. Processes 2023, 11, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, C.W.; Chartrand, P.; Degterov, S.; Eriksson, G.; Hack, K.; Mahfoud, R.B.; Melançon, J.; Pelton, A.; Petersen, S. FactSage Thermochemical Software and Databases. Calphad 2002, 26, 189–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, C.W.; Bélisle, E.; Chartrand, P.; Decterov, S.; Eriksson, G.; Gheribi, A.; Hack, K.; Jung, I.-H.; Kang, Y.-B.; Melançon, J. Reprint of: FactSage Thermochemical Software and Databases, 2010–2016. Calphad 2016, 55, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D. Advancing Methodologies for Elemental Transfer Quantification in The Submerged Arc Welding Process: A Case Study of CaO-SiO2-MnO Flux. Processes 2024, 12, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Shi, H.; Huang, L.; Mao, Z. Element Loss Behavior and Compensation in Additive Manufacturing of Memory Alloys. Trans. China Weld. Inst. 2022, 43, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, A.; Thewlis, G.; Whiteman, J. Nature of Inclusions in Steel Weld Metals and Their Influence on Formation of Acicular Ferrite. Mater. Sci. Technol. 1987, 3, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Liu, P. Thermodynamic Nature of SiO2 and FeO in Flux O Potential Control Subject to Submerged Arc Welding Process. Processes 2023, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.-S. Slag-Metal Reactions During Flux-Shielded Arc Welding. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Minh, P.S.; Nguyen, V.-T.; Nguyen, V.T.; Uyen, T.M.T.; Do, T.T.; Nguyen, V.T.T. Study on the Fatigue Strength of Welding Line in Injection Molding Products under Different Tensile Conditions. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuschkel, J. Composition Controlled, High-Strength, Ductile, Tough Steel Weld Metals. Weld. J. 1964, 43, 361s–384s. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, W.; Faulkner, G.; Rieppel, P. F Flux and Filler Wire Developments for Submerged Arc Welding HY80 steel. Weld. J. 1961, 40, 337s–340s. [Google Scholar]

- Dowden, J.; Kapadia, P. Plasma Arc Welding: A Mathematical Model of the Arc. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1994, 27, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nart, E.; Celik, Y. A Practical Approach for Simulating Submerged Arc Welding Process Using FE Method. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2013, 84, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönmaier, H.; Krein, R.; Schmitz-Niederau, M.; Schnitzer, R. Influence of the Heat Input on the Dendritic Solidification Structure and the Mechanical Properties of 2.25 Cr-1Mo-0.25 V Submerged-Arc Weld Metal. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 7138–7151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanie, J.; Oguocha, I.; Yannacopoulos, S. Effect of Submerged Arc Welding Parameters on Microstructure of SA516 Steel Weld Metall. Can. Metall. Q. 2012, 51, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).