Abstract

This study proposes an optimization framework based on Multi-agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MADRL), conducting a systematic exploration of FJSP under dynamic scenarios. The research analyzes the impact of two types of dynamic disturbance events—machine failures and order insertions—on the Dynamic Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem (DFJSP). Furthermore, it integrates process selection agents and machine selection agents to devise solutions for handling dynamic events. Experimental results demonstrate that, when solving standard benchmark problems, the proposed multi-objective DFJSP scheduling method, based on the 3DQN algorithm and incorporating an event-triggered rescheduling strategy, effectively mitigates disruptions caused by dynamic events.

1. Introduction

Manufacturing, as a crucial national industry, holds a pivotal position in global economic development. Serving as a pillar industry in China, manufacturing is a vital component underpinning China’s economic growth. Currently, the manufacturing sector is undergoing a profound transformation from traditional models towards digitization and servitization. Enterprises are confronted with not only technical challenges such as reducing production cycles and controlling costs but also structural shifts in market demand towards greater product diversity and smaller batch sizes. Against this backdrop, production scheduling technology has emerged as an increasingly significant means for optimizing manufacturing systems [1].

As an extension of the traditional Job Shop Scheduling Problem (JSP), the Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem (FJSP) breaks through the limitation of single-machine processing, allowing operations to be flexibly allocated within a set of alternative machines. This approach enhances both machine utilization and production flexibility while enabling rapid responses to dynamic disturbances such as machine failures. These characteristics align with the demands of modern discrete manufacturing, making FJSP a focal point of research in both industry and academia over the past decade [2]. Recent advancements in FJSP research exhibit a multidimensional development trend: shifting from the sole pursuit of minimizing makespan or total machine load to a comprehensive consideration of energy consumption management, dynamic event response, and multi-objective optimization [3]. Additionally, the application scope of FJSP has expanded to encompass complex systems across diverse domains, including transportation and healthcare.

MAS (Multi-Agent System) is a complex system composed of multiple intelligent agents with autonomous decision-making capabilities, interacting through protocols and organizational rules. MADRL (Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning) is a fusion technology combining Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) with MAS. Its core lies in enabling multiple autonomous agents to collaborate or compete in dynamic environments, achieving global optimization for complex tasks. FJSP (Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem), as a typical NP-hard combinatorial optimization problem, requires simultaneous solutions for process sequencing, machine allocation, and resource coordination across multiple decision dimensions. MADRL demonstrates computational efficiency and solution quality advantages in addressing such problems based on hierarchical architectures [4].

In conclusion, the flexible shop floor scheduling problem based on deep reinforcement learning holds significant research value and practical implications. By thoroughly investigating this issue, we can provide robust support for smart factory development, enhance production efficiency, reduce manufacturing costs, adapt to dynamic environments, and drive the advancement of intelligent manufacturing. To achieve these objectives, this study establishes a dynamic event-driven FJSP mathematical optimization model to systematically analyze disturbance impacts. Based on the advantages demonstrated by MADRL in solving FJSP, we designed a 3DQN-based multi-agent collaborative framework that decouples process prioritization from machine allocation decisions. Furthermore, through comparative analysis of right-shift rescheduling and full rescheduling strategies, we validate their effectiveness across various operational scenarios. The research results provide theoretical and methodological support for intelligent factories to balance production flexibility and efficiency in real-time scheduling decisions, and promote intelligent manufacturing systems to a higher level of autonomous optimization.

2. Current Research Status

2.1. FJSP Current Research Status

FJSP is a significant extension of traditional JSP [5], with its core feature being the breakthrough of single-device constraints. By introducing machine flexibility, it significantly enhances the adaptability of production systems. This concept was first proposed by Bruker et al. in 1990 [6]. Existing research primarily employs multi-objective optimization algorithms and DRL frameworks. Hou et al. [7] addressed multi-objective distributed flexible workshop scheduling by proposing a collaborative evolution framework (CEGA-DRL), which for the first time deeply integrated DRL with NSGA-III at the genetic level. Tang et al. [8] focused on minimizing the makespan and total carbon emissions. To optimize the objectives, a hybrid integer programming model was established, and an improved Q-learning-based artificial bee colony algorithm was proposed. A hybrid population initialization method was also introduced to enhance the quality of initial solutions and the convergence performance of the algorithm. Wei et al. [9] proposed a hybrid algorithm combining distribution estimation and tabu search (H-EDA-TS). Three probability models were designed for sampling generation. The study proposes five neighborhood structures tailored for optimization objectives to generate neighborhood solutions. Comparative experiments on instances of varying scales demonstrate the superiority of the proposed algorithm. These findings further highlight the significant advantages of hybrid optimization algorithms and intelligent search strategies in multi-objective flexible shop floor scheduling, driving algorithmic innovation in this field. Through hybrid architecture design, objective decomposition strategies, and efficient search mechanisms, breakthroughs have been achieved in solution quality, computational efficiency, and industrial applicability. However, further exploration is needed to enhance real-time responsiveness under dynamic perturbations and cross-shop generalization capabilities.

From a methodological perspective, the a priori approach struggles to effectively obtain Pareto optimal solution sets that reflect trade-offs between objectives, exhibiting theoretical limitations in solution diversity and decision space coverage. Further analysis reveals that while the a posteriori method can generate approximate solution sets through population evolution mechanisms, it still faces critical challenges in algorithm design: existing research predominantly focuses on improving global exploration strategies, while lacking systematic investigation into neighborhood-based local search mechanisms. This results in difficulties in achieving dynamic equilibrium between convergence accuracy and population diversity.

2.2. Necessity and Core Challenges of Dynamic Scheduling

In dynamic manufacturing environments, production systems frequently encounter unexpected challenges such as machine failures, urgent order interventions, and real-time responsiveness demands in large-scale computing scenarios. These operational pressures increasingly expose the limitations of traditional static scheduling methods. Fixed-rule-based heuristic algorithms and data-dependent meta-heuristics struggle to effectively manage real-time updates of operational data streams, particularly when handling frequent order changes or fluctuating resource availability. This often results in a trade-off between solution quality and computational efficiency—a classic efficiency dilemma in modern manufacturing systems.

To meet the real-time responsiveness requirements of scheduling systems in dynamic manufacturing environments, research has focused on developing advanced scheduling strategies and intelligent algorithms. Current research on Flexible Job Shop Scheduling (FJSP) has made significant progress using meta-heuristic methods such as particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithms. Pezzella et al. [10] developed a genetic algorithm (GA) with dual-layer encoding for operations and machines, using an elite retention strategy to speed up convergence. Lei et al. [11] proposed an improved genetic algorithm that improves solution quality through non-dominated sorting and crowding distance calculations. Ge et al. [12] applied co-evolutionary principles to optimize both operation sequences and machine assignments. Zhang et al. [13] introduced enhanced crossover operators, such as priority-based crossover, to greatly reduce invalid solutions. Xing et al. [14] incorporated domain knowledge, like critical path analysis, into pheromone update rules to better guide process sequencing. However, these single-objective approaches often struggle to handle multidimensional constraints and dynamic uncertainties in real-world production environments. Consequently, Dynamic Multi-objective Flexible Workshop Scheduling Problem (DM-FJSP) has emerged as a cutting-edge research frontier, with its core challenges lying in How to coordinate the optimal balance of total completion time, equipment loads balancing, energy consumption and other objectives in real time under random disturbances such as machine failure and emergency order insertion.

2.3. Current Research Status of Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning

Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning effectively addresses challenges such as high constraints, dynamic disturbances, and multi-objective optimization by introducing a collaborative mechanism among distributed agents. Significant progress has been made in the research of multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for flexible workshop scheduling, with scholars proposing various innovative methods tailored to different scenarios. Zhang et al. [15] proposed a cooperative scheduling method based on multi-agent non-cooperative-evolutionary game theory to address resource conflicts and suboptimal solutions in machine-AGV (Automated Guided Vehicle) coordination scheduling for flexible production workshops. Jiang et al. [16] addressed the optimization challenge of minimizing delivery delays in machine tool mixed-flow assembly lines by proposing a dual-value network with parameter sharing technology to solve non-stationary problems, while introducing global/local reward functions to mitigate reward sparsity. Liu et al. [17] tackled scalability challenges in large-scale workshop scheduling by proposing a hierarchical multi-agent architecture and distributed training framework, enhancing algorithm adaptability in complex scenarios through communication topology optimization. Li et al. [18] proposed an attention-based multi-agent reinforcement learning method for cooperative-competitive hybrid game scenarios in workshop scheduling, effectively coordinating heterogeneous intelligent systems. The strategic learning process of the system. Ma et al. [19], addressing the spatiotemporal randomness in taxi supply-demand matching within dynamic traffic networks, implemented a static transformation of cross-period vehicle scheduling tasks through variable learning rates and adaptive reward mechanisms within the Wolf-PHC deep reinforcement learning framework. Zhang et al. [20], tackling the multi-objective scheduling challenge of low-orbit constellation beam resources, innovatively developed a hybrid expert-model-driven multi-agent deep reinforcement learning framework. By adopting a divide-and-conquer strategy for multi-dimensional resource coordination scheduling, they established an algorithmic paradigm for energy-efficiency and efficiency multi-objective optimization in flexible workshop multi-process routes. By integrating game theory, distributed learning and deep reinforcement learning, these studies significantly improve the optimization performance and decision-making efficiency of flexible workshop scheduling in dynamic environment.

However, traditional optimization methods face a critical trade-off between improving solution set quality and computational efficiency, particularly prone to dimensionality issues in large-scale scenarios. Moreover, existing scheduling models predominantly rely on static environment assumptions, lacking real-time responsiveness to dynamic disturbances like equipment failures and order modifications. The absence of a systematic dynamic scheduling framework has severely constrained the engineering applicability of FJSP solutions in smart manufacturing environments.

Notably, DRL technology offers innovative solutions to these challenges through its environmental interaction capabilities and self-optimizing strategies. By establishing a closed-loop learning mechanism of state-action-reward, it enables autonomous evolution of scheduling strategies while effectively capturing nonlinear correlations between dynamic events and scheduling decisions through end-to-end training. Building on this foundation, this study focuses on deep integration of DRL and FJSP, targeting breakthroughs in key technologies such as adaptive scheduling strategy generation under dynamic environments and multi-objective collaborative optimization mechanisms. The ultimate goal is to develop an intelligent scheduling methodology system that combines theoretical innovation with practical engineering applicability. Specifically, By designing a hierarchical reinforcement learning architecture and a hybrid reward function, the global optimization goal and dynamic constraints are mapped together, thus providing a new methodological support for real-time scheduling decisions in complex manufacturing environments.

3. Problem Overview and Theoretical Analysis

3.1. Mathematical Model for the FJSP

FJSP, serving as an extension of the classic job shop scheduling problem, is characterized by its core features: machine flexibility and routing flexibility in the processes, along with the necessity to meet corresponding constraints. To establish a mathematical optimization model for the FJSP, the following provides explanations for the pertinent parameter symbols and decision variables.

: Total number of jobs;

: Total number of machines;

: The number of processes for job ;

: Job index, ;

: Process index, ;

: Machine index; ;

: The th operation of Job ;

: Collection of jobs, ;

: Machine Collection, ;

: Process set of job , ;

: Completion time of job ;

: Start time of processing on machine for process ;

: End time of processing on machine for process ;

: The processing time of process on machine ;

: The power consumption of the th track of job on machine ;

: The processing time of the th track of job on machine ;

: Makespan;

: A sufficiently large positive number;

: The energy consumption of the th track of job on machine ;

: Total energy consumption;

;

.

This article establishes a rigorous mathematical optimization model with the objectives of minimizing the maximum completion time, total energy consumption, and overall mechanical load. The precise formulation of the objective function is outlined as follows:

- (1)

- Minimize Makespan [21]:

- (2)

- Minimize Total Energy Consumption [22]:

- (3)

- Minimize Total Mechanical Load [23]:

Constraints:

- (1)

- Job Sequence Constraint: Ensures that each subsequent operation of a job commences only after the preceding operation has been completed.

- (2)

- Machine Assignment Uniqueness: Each operation must be exclusively assigned to a single candidate machine.

- (3)

- Resource Non-Conflict Constraint: The processing time intervals of any two operations assigned to the same machine must not overlap.

- (4)

- Processing Time Association: Operations are processed without interruption; processing is non-preemptive.

- (5)

- Non-Negative Time Constraint: All start times, processing times, and completion times must be non-negative.

3.2. FJSP Solving Model Based on 3DQN Algorithm

DQN [24] is a paradigm of deep reinforcement learning based on value function. It parameterizes action value functions through neural networks, with its core mechanisms including: the Experience Replay mechanism that breaks temporal correlations, the Target Network that stabilizes training processes, and the Double DQN [25] architecture that mitigates overestimation bias.

Traditional DQN employs experience replay to train two neural networks—the main network and the target network—aiming to approximate the action value function. The algorithm’s action value function is expressed in Equation (12).

where and represents the state and action at time ; is the discount factor; is the reward and penalty signal received by the agent from the environment; is the neural network parameters.

In the DQN algorithm architecture, the main network is parameterized as , Update and iterate the main network value in real time. Parameterize the target network as . Update the iteration every cycle to speed up the convergence of the system. The DQN algorithm updates the table by maximizing bias, which can easily lead to overestimation of values . Double DQN addresses this issue by employing the main network to select actions and the target network to update values , with the action value function defined in Equation (13).

The Double DQN algorithm updates neural network parameters by leveraging the combined value of states and actions , without separately considering the deep value of each component. When actions have minimal impact on states, the neural network struggles to accurately update action values. To address this, this chapter introduces the Dueling Network framework. It first decouples states and actions to predict the value of the current environmental state and the value of each action under that state. The combined state-action value is then formed by integrating these two components. The optimal advantage value function is expressed as Equations (3)–(14).

where represents the optimal state-action value function; represents the optimal state value function.

To prevent the interference output from having the same amplitude and opposite direction, which may lead to suboptimal neural network training results, a reference vector is added to the right side of the Equation. Simultaneously, the maximum value of the action is taken, represented as:

Based on Equations (14)–(16), the action-value function of 3DQN is expressed in Equation (17).

During the th iteration of the 3DQN-based reinforcement learning algorithm, experience is uniformly sampled from the experience pool to update the loss function (18).

The minimized loss function after gradient descent is given by Equation (19).

Priority experience replay prioritizes replaying experiences with higher learning value based on TD error magnitude. The TD error itself reflects the gap between the current estimate and the target value, which is influenced by the reward. Therefore, the reward function directly affects the TD error magnitude, thereby influencing the priority score.

In summary, 3DQN is an optimization algorithm that combines the strengths of Dueling DQN and Double DQN. Double DQN addresses the overestimation issue in classical DQN by separating action and value computations: the main network selects actions while the target network calculates value functions, thereby enhancing valuation stability. Dueling DQN further splits the target network’s output into two components—the environment’s state value function and the action’s value function—allowing the agent to better distinguish between state value and action value. By integrating these dual advantages, 3DQN enables the agent to More accurate estimates can also lead to more stable training.

3.3. Description and Analysis of the Flexible Job Shop Dynamic Scheduling Problem

In recent years, MADRL has demonstrated unique advantages in addressing the DFJSP, owing to its distributed decision-making capabilities. By mapping shop-floor entities (machines, jobs) to autonomous agents, MADRL facilitates the construction of a hierarchical collaborative decision-making architecture: bottom-layer agents are responsible for local state perception and action execution, while a top-level coordinator achieves global goal decomposition and conflict resolution. This paper establishes a multi-agent collaborative dynamic scheduling system architecture, forming a closed-loop optimization mechanism based on dynamic event response and multi-agent collaborative decision-making. Building upon the foundation of the FJSP, the model introduces two types of disruptive events—machine breakdowns and order insertions. Algorithmic enhancements are further developed to account for the resultant temporal shifts along the scheduling timeline caused by these dynamic event disturbances.

To address potential uncertainty factors within the production process, two typical categories of dynamic events are introduced for analysis: machine failures and order insertions. Accordingly, corresponding notations are supplemented in the original scheduling model, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Dynamic event-related notations.

Machine failures are typically triggered by equipment aging or overload operation. Such events may occur at unpredictable intervals and are inherently difficult to forecast. To model this stochastic nature, this paper employs two key parameters: failure occurrence probability and repair duration. The random occurrence of failures is simulated using a Poisson distribution, with its probability remaining constant per unit time. The probability of a failure occurring within a given unit time is expressed by Equation (20).

where denotes the failure rate (average number of failures per unit time), whose value can be calibrated using historical maintenance data.

The repair duration can be randomly generated according to the uniform distribution specified in Equation (21).

where and denote the minimum and maximum repair times, respectively.

For machine failure events, in addition to the aforementioned constraints, the machine failure constraint specified in Equation (22) must be incorporated: if machine fails within the time interval , no tasks can be assigned to it.

To simulate scenarios involving urgent order insertion in the workshop, it is assumed that an urgent order is inserted at fixed intervals T. Since urgent orders cannot be scheduled immediately upon insertion and must await the completion of the current task on the target machine, Constraint (23) is introduced.

where denotes the order insertion time, represents the earliest available time of machine .

The DFJSP studied in this chapter focuses on real-time optimization requirements during continuous production, with its dynamic nature characterized by responsiveness to external perturbations. The scheduling objective is to generate an available machine set and operation sequence for the pending operations set at each rescheduling decision point, based on real-time system state information, thereby minimizing the multi-objective optimization function expressed in Equation (24).

where denotes the makespan, represents the total energy consumption and indicates the total machine load.

3.4. Transformation of Dynamic Flexible Job-Shop Scheduling Problems

3.4.1. Dynamic Rescheduling Strategy

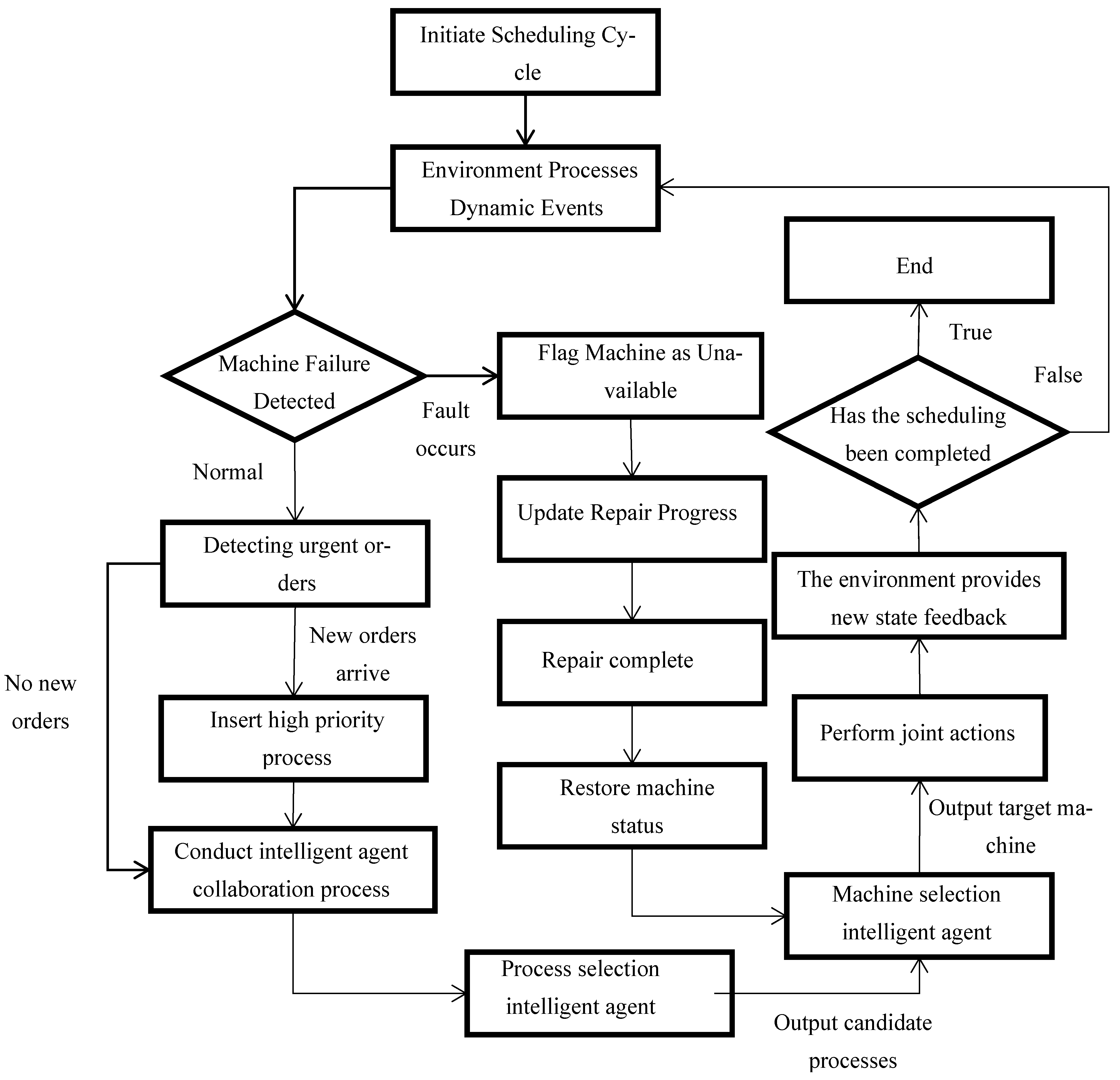

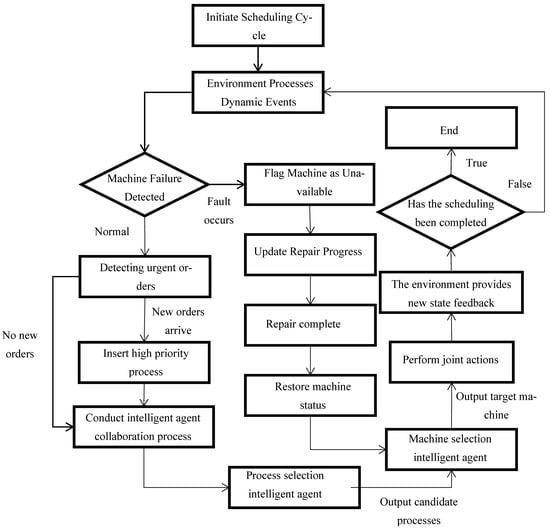

Figure 1 shows the architecture of a dynamic scheduling system based on multi-agent collaboration, whose core processes can be divided into dynamic event response and multi-agent collaborative decision-making. After the system starts the scheduling cycle, it will monitor the real-time operation status of machines and order insertion in the workshop. Upon detecting a machine failure, it immediately marks the faulty machine as “unavailable”, pause the current processing task, and update the machine’s status based on the estimated repair time; After the fault repair is completed, the machine will be restored to normal and the pending processing tasks will be reassigned. For urgent order insertion, insert it into the high priority queue and trigger the rescheduling algorithm to generate an optimized production plan; If there are no urgent orders with high priority, they will be executed according to regular scheduling until the next scheduling cycle begins.

Figure 1.

Multi-Agent Collaborative Dynamic Scheduling Flowchart.

Dynamic scheduling first initializes the parameters and environmental state space, triggering decisions only when both the pending process and idle machines are present to avoid resource waste. The process agent prioritizes scheduling urgent orders, the machine selects the agent to allocate available equipment, and finally updates the environmental state space. When an urgent order is inserted, the list of pending processes is immediately updated, and the process agent recalculates the priority; When the machine malfunctions, immediately mark the faulty machine as unavailable, pause the associated process, and enable it again after the repair is completed. During this period, update the list of available machines in real time. Through multiple iterations, the intelligent agent gradually learns the optimal strategy.

3.4.2. Dynamic Scheduling Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning

This section proposes a multi-agent deep reinforcement learning training strategy based on 3DQN to address the dynamic characteristics of machine failures and urgent order insertion in DFJSP. Through the collaborative optimization of process selection and machine selection, combined with dynamic event response mechanism and reward design, scheduling optimization is achieved.

Firstly, a centralized training distributed execution structure is adopted. During the training phase, the strategies of each agent are optimized based on global state information, while during the execution phase, each agent relies only on local states for decision-making. As shown in Table 2, the intelligent agent for process selection in this chapter dynamically adjusts the processing sequence based on process priority. The input includes equipment load, remaining process time, and emergency order status, and the output is the process scheduling strategy; The machine selection agent allocates processing tasks based on machine availability, failure probability, and energy consumption indicators. The input is the machine state vector, and the output is the -value distribution of the machine selection action.

Table 2.

Intelligent agent information.

To coordinate interactions between the two agents, a joint experience replay buffer is introduced to store global state-action-reward tuples. A hierarchical prioritized sampling mechanism is designed to refine the algorithmic training architecture based on the dynamic scheduling framework.

Regarding the handling of machine breakdown perturbations, the procedure involves calculating a rescheduling index according to Equation (25). This index integrates the pre-failure processing time, transfer time, repair time, and post-repair processing time when machine breakdowns lead to extended operation durations.

where denotes the rescheduling index of operation ; represents the estimated completion time of operation after machine breakdown; indicates the standard completion time of operation ; and signifies the disturbance tolerance coefficient of operation . The disturbance tolerance coefficient is a reasonable tolerance threshold determined by analyzing the frequency, duration, and impact range of machine failures in historical scheduling data.

For dynamic events related to urgent order insertion processing, the order insertion rescheduling strategy determines the priority of new orders (taking into account delivery time, profit contribution, and maximum completion time) and compares it with the priority of the current processing task. If the priority of the new order is higher, trigger rescheduling and generate a new plan; Otherwise, add it to the waiting queue. The process includes initial scheduling execution, dynamic priority determination, and rescheduling decisions to ensure priority response for urgent tasks.

During the training phase, the agent selects actions based on a certain probability. Specifically, a random number with a value range of [0, 1] is generated at each scheduling point. When it is less than , the agent randomly selects an action; On the contrary, choose the action with the highest value . The purpose of this design is to balance exploration and utilization during the training process. As the number of training rounds increases, it gradually decreases, which prompts the agent to be more inclined to choose the best action to improve its decision-making performance.

4. Experimental Design and Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

Experiments were conducted on an Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-11320H processor with 16 GB RAM using the PyTorch 2.0 framework to implement multi-agent deep reinforcement learning algorithms. The Brandimarte benchmark dataset was selected to validate the proposed method’s effectiveness. Key parameters for the 3DQN algorithm included learning rate , discount factor , experience replay buffer capacity of 1024, batch size 128, target network update period , soft update coefficient , and the iteration count is 500. Time units were measured in hours (h), energy consumption in kilowatt-hours (kWh), and load in kilowatts (kW).

4.2. Experimental Design

To address dynamic machine failures and order insertion events, this chapter comparatively analyzes right-shift rescheduling and full rescheduling strategies, aiming to reveal their optimization efficacy and applicability boundaries in multi-objective dynamic flexible job shop scheduling. The core distinction between these strategies lies in adjustment authority over operations: right-shift rescheduling only permits delaying affected processes, whereas full rescheduling globally reconstructs subsequent workshop schedules. Using the MK01 instance from the Brandimarte dataset, we first validated the algorithm’s scheduling effectiveness under dynamic event perturbations. Subsequently, we benchmarked solution set quality against DoDQN and DuDQN algorithms for multi-objective dynamic scheduling performance.

4.3. Results Analysis

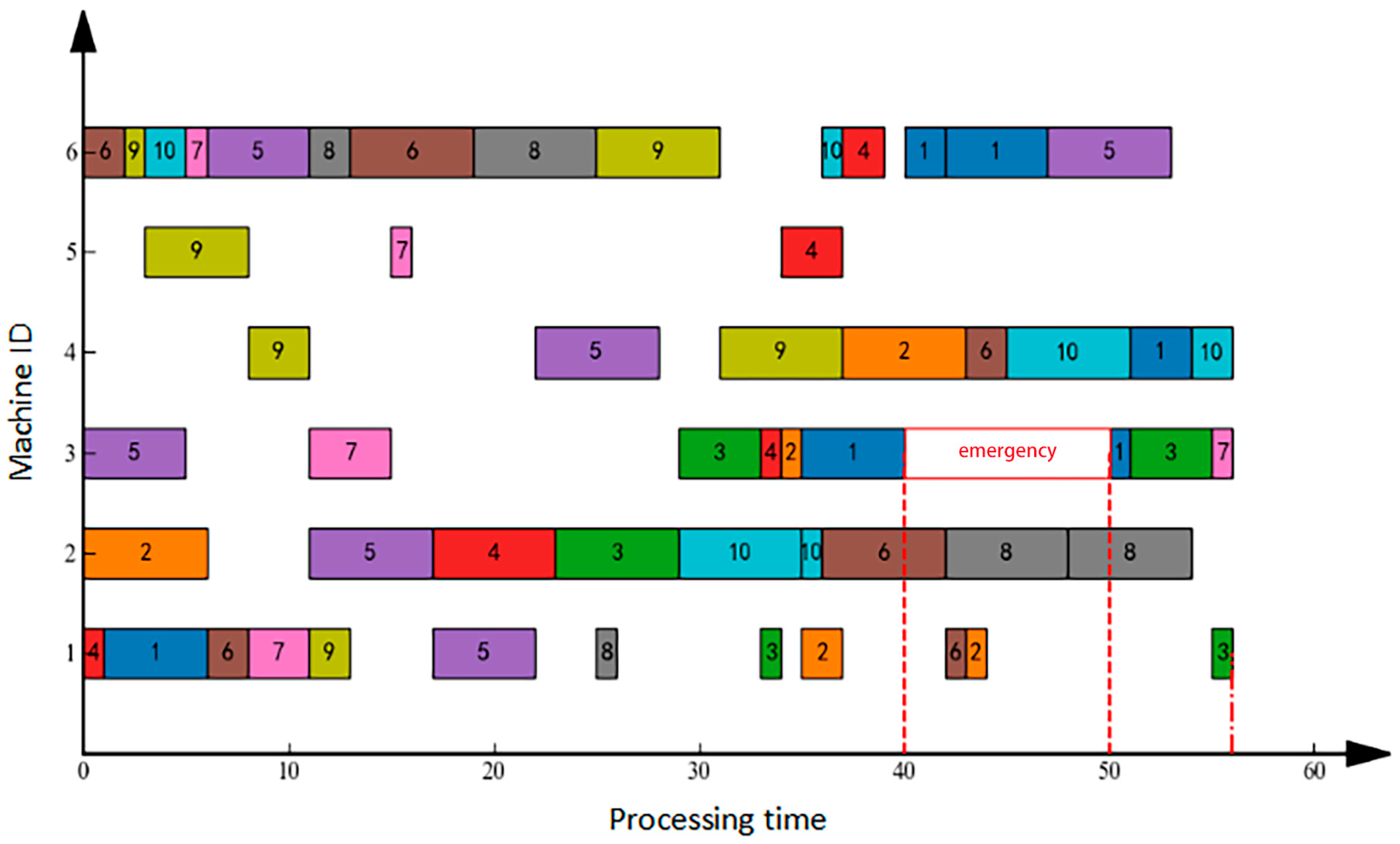

4.3.1. Machine Failure Rescheduling Experiment

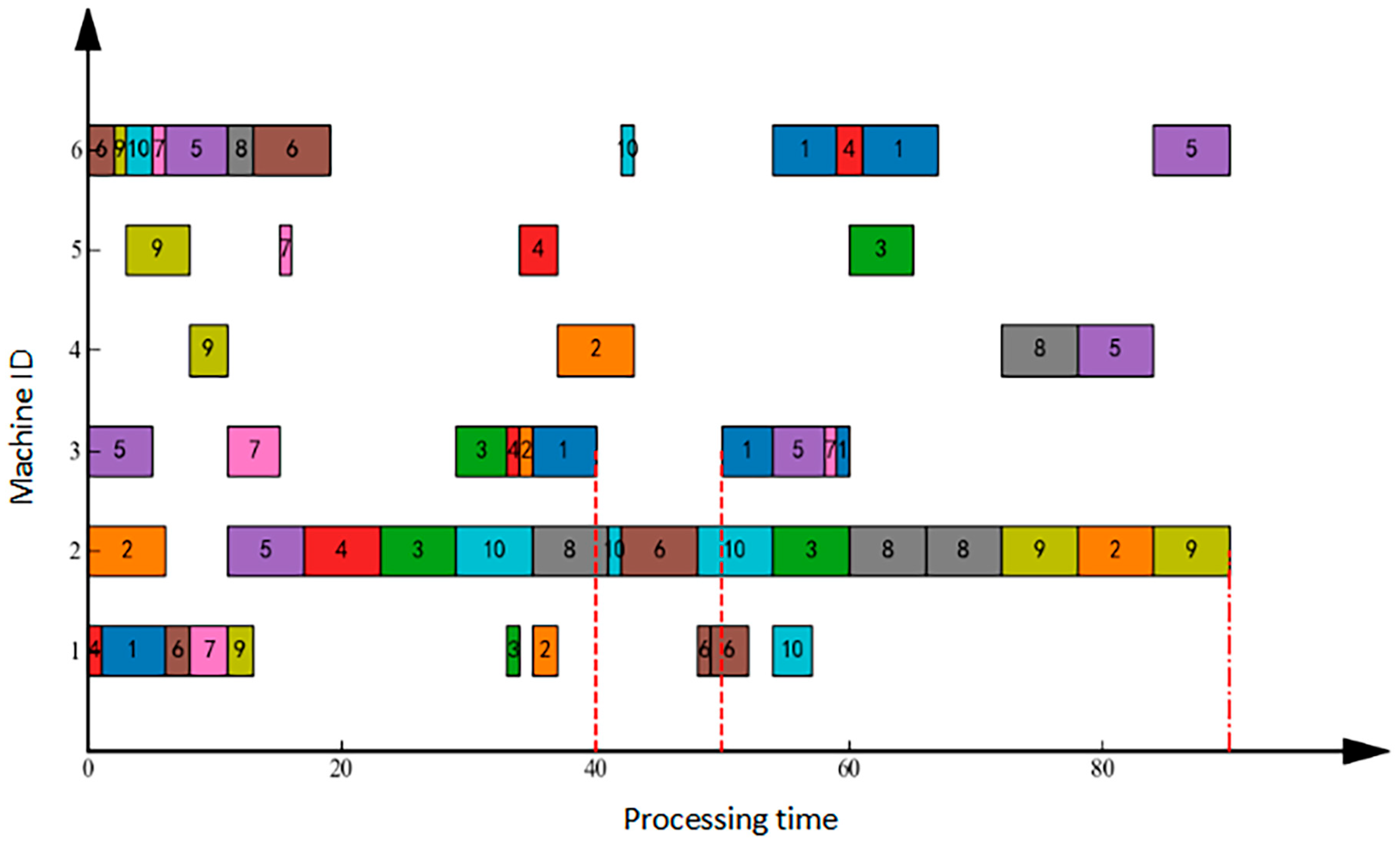

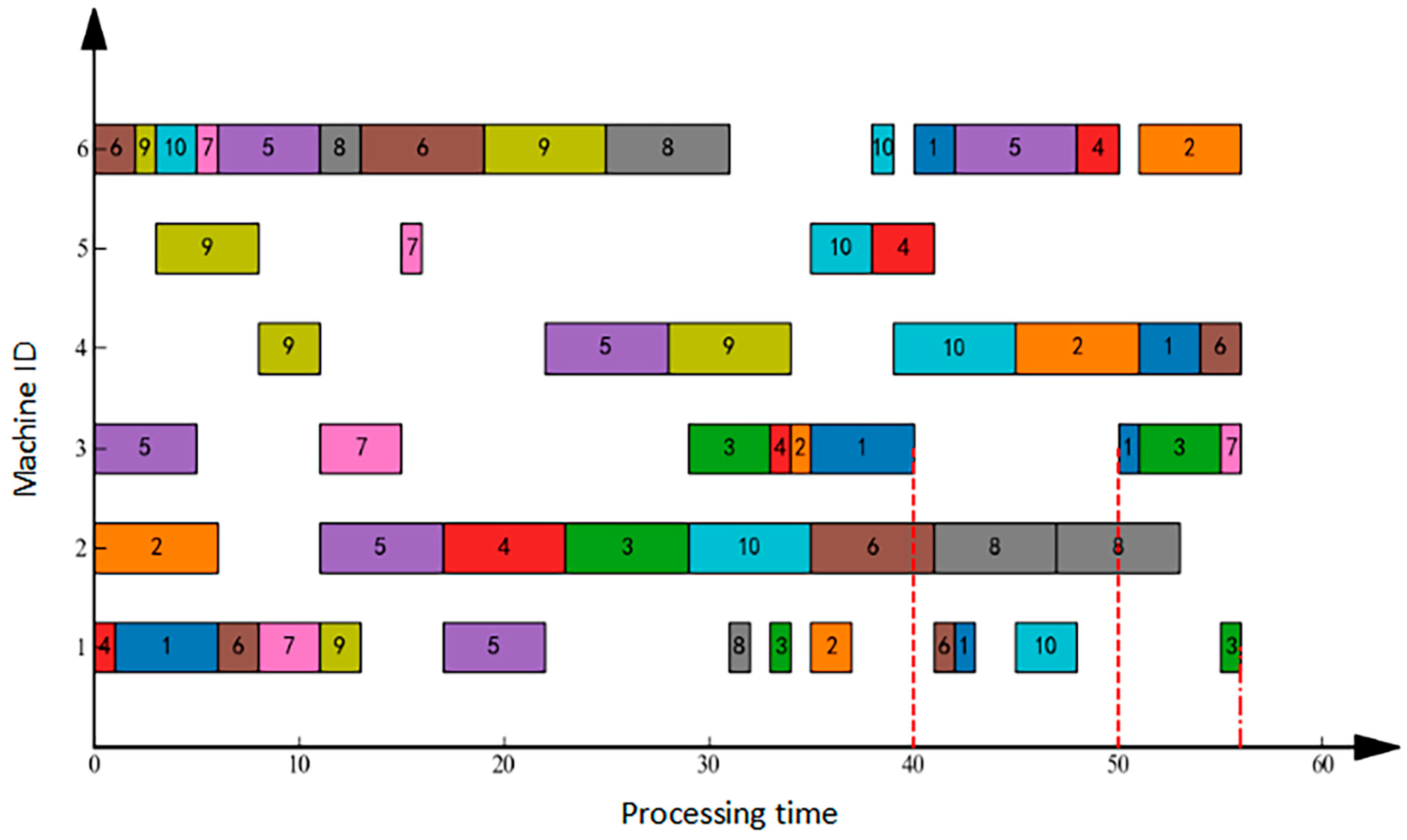

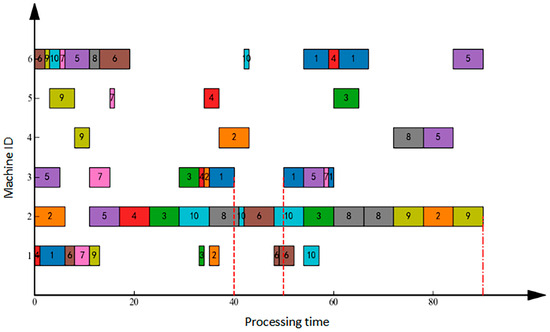

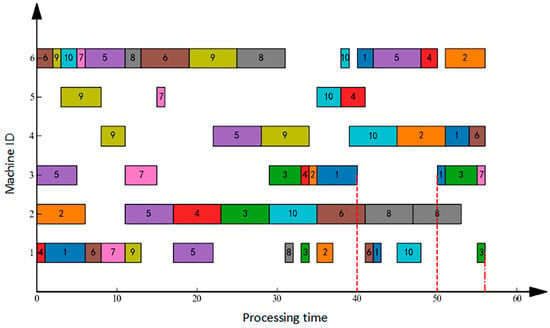

Machine failure refers to an unexpected breakdown of equipment during scheduling, necessitating production task reassignment. In this scenario, after implementing the initial schedule, the workshop operated normally until time T = 40 when Machine 3 failed, with an expected recovery time of 10 units. Figure 2 illustrates the right-shift rescheduling solution: the failure occurred at T = 40, was resolved by T = 50, and resulted in a final makespan of 90 units. Conversely, Figure 3 demonstrates the full rescheduling approach: the same failure event (onset T = 40, resolution T = 50) achieved a significantly reduced makespan of 56 units. Comparative analysis confirms that for sudden machine failures, full rescheduling outperforms right-shift rescheduling by delivering shorter completion times.

Figure 2.

Gantt Chart for Machine Failure Right-Shift Rescheduling.

Figure 3.

Gantt Chart for Machine Failure Full Rescheduling.

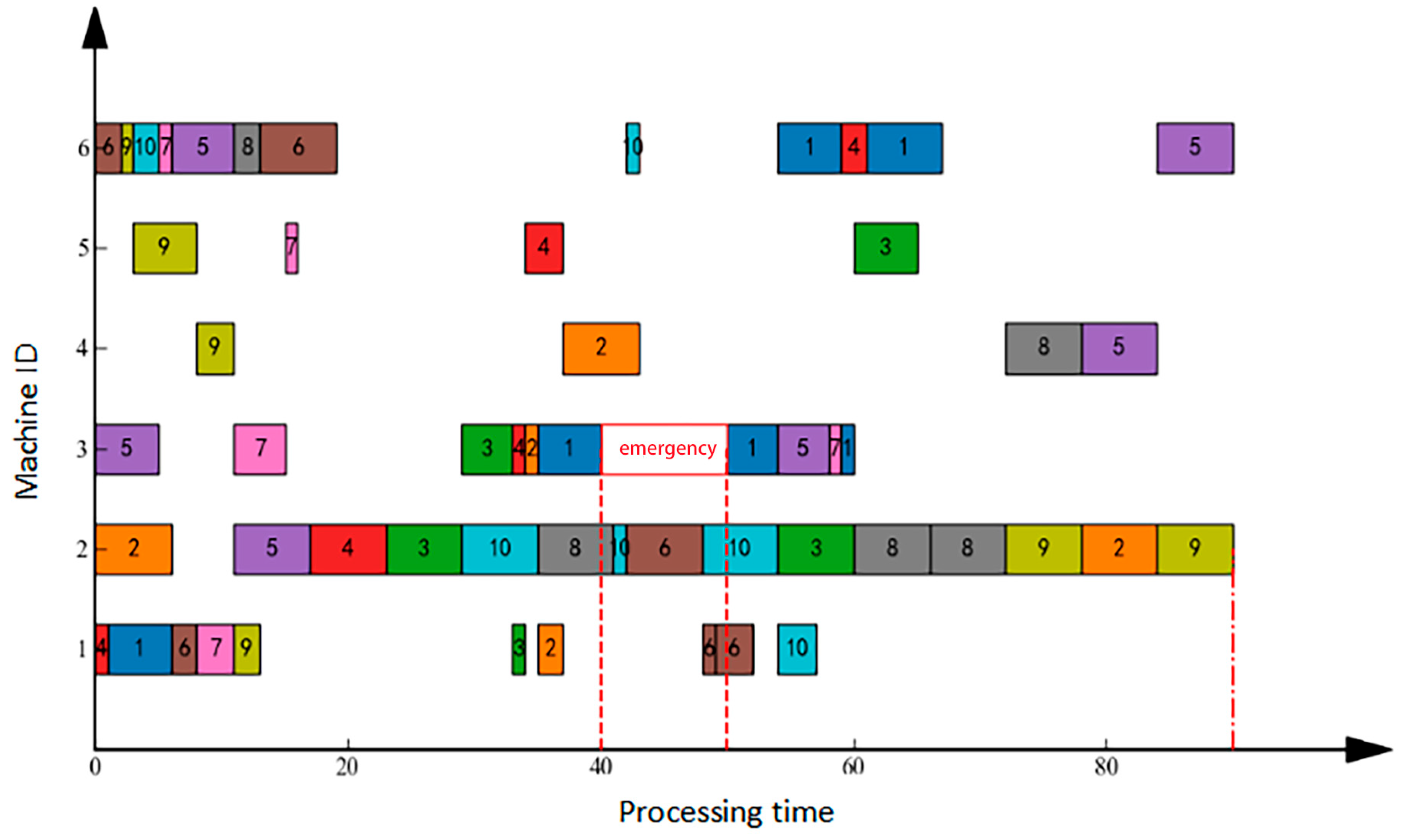

4.3.2. Order Insertion Rescheduling Experiment

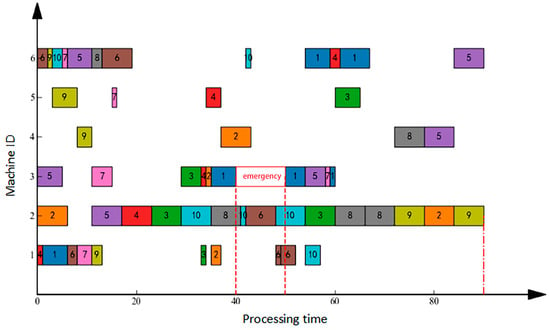

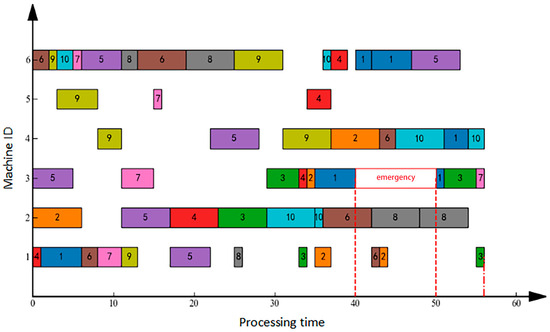

Urgent order insertion denotes the abrupt integration of a new production order into the scheduling system requiring immediate processing. Under the initial schedule, a new order was inserted at approximately T = 40, conceptually analogous to a specialized machine failure scenario. Figure 4 and Figure 5, respectively, illustrate the right-shift rescheduling and full rescheduling approaches applied to this event. Analysis of Figure 4 indicates that right-shift rescheduling displaced all subsequent tasks post-insertion, extending the makespan to 90 units—while ensuring new order processing, this significantly compromises existing order deliveries. Conversely, Figure 5 demonstrates that full rescheduling comprehensively re-optimized the production plan, achieving a refined makespan of 56 units through strategic task reassignment across machines and resequencing; this minimizes original schedule disruption while accommodating the urgent order. Gantt chart analysis confirms enhanced machine load balance and superior temporal efficiency in full rescheduling, with resource utilization visibly optimized versus right-shift rescheduling, conclusively demonstrating full rescheduling’s superiority for urgent order insertion via holistic schedule reconfiguration.

Figure 4.

Gantt Chart for Order Insertion Right-Shift Rescheduling.

Figure 5.

Gantt Chart for Order Insertion Full Rescheduling.

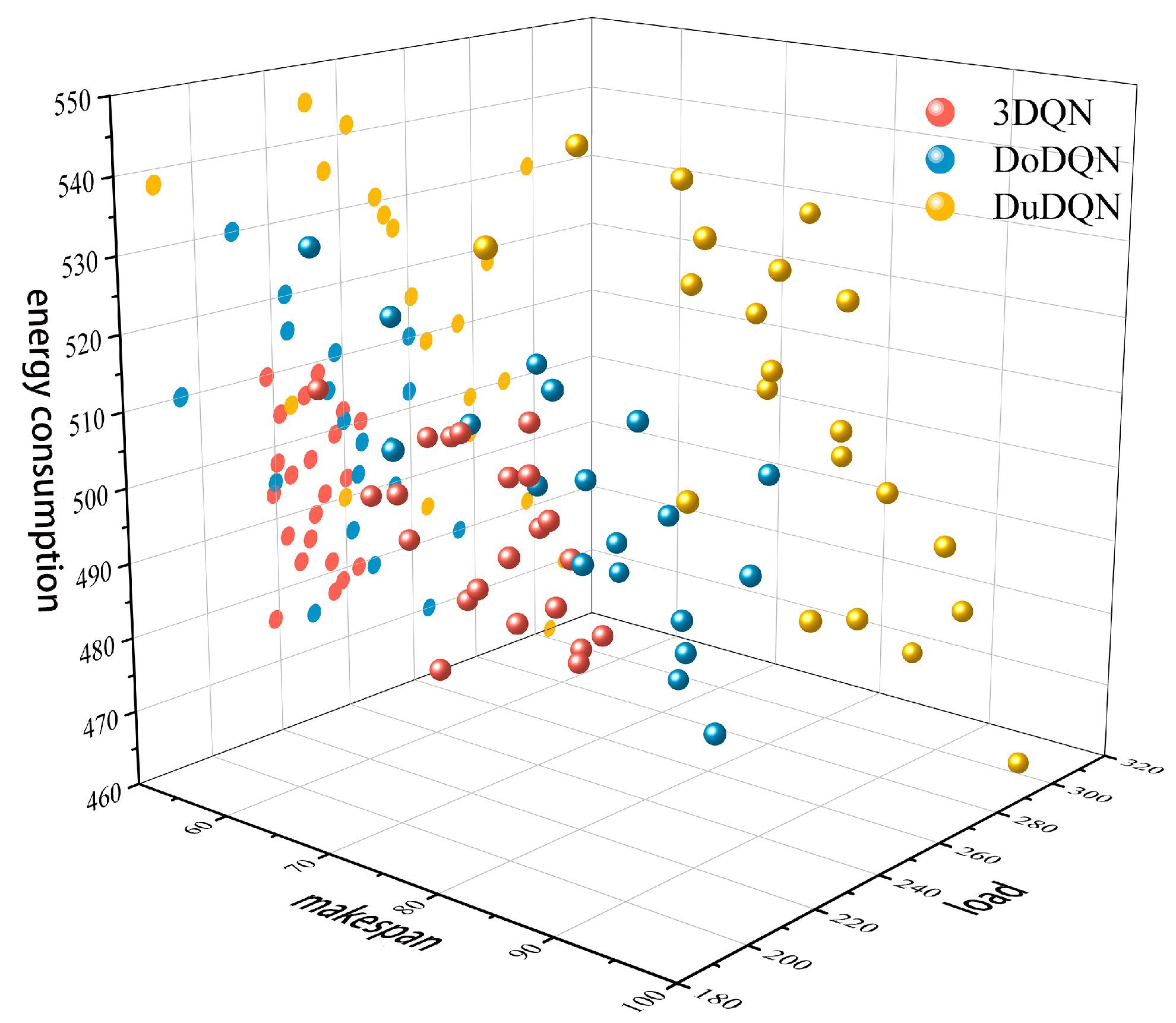

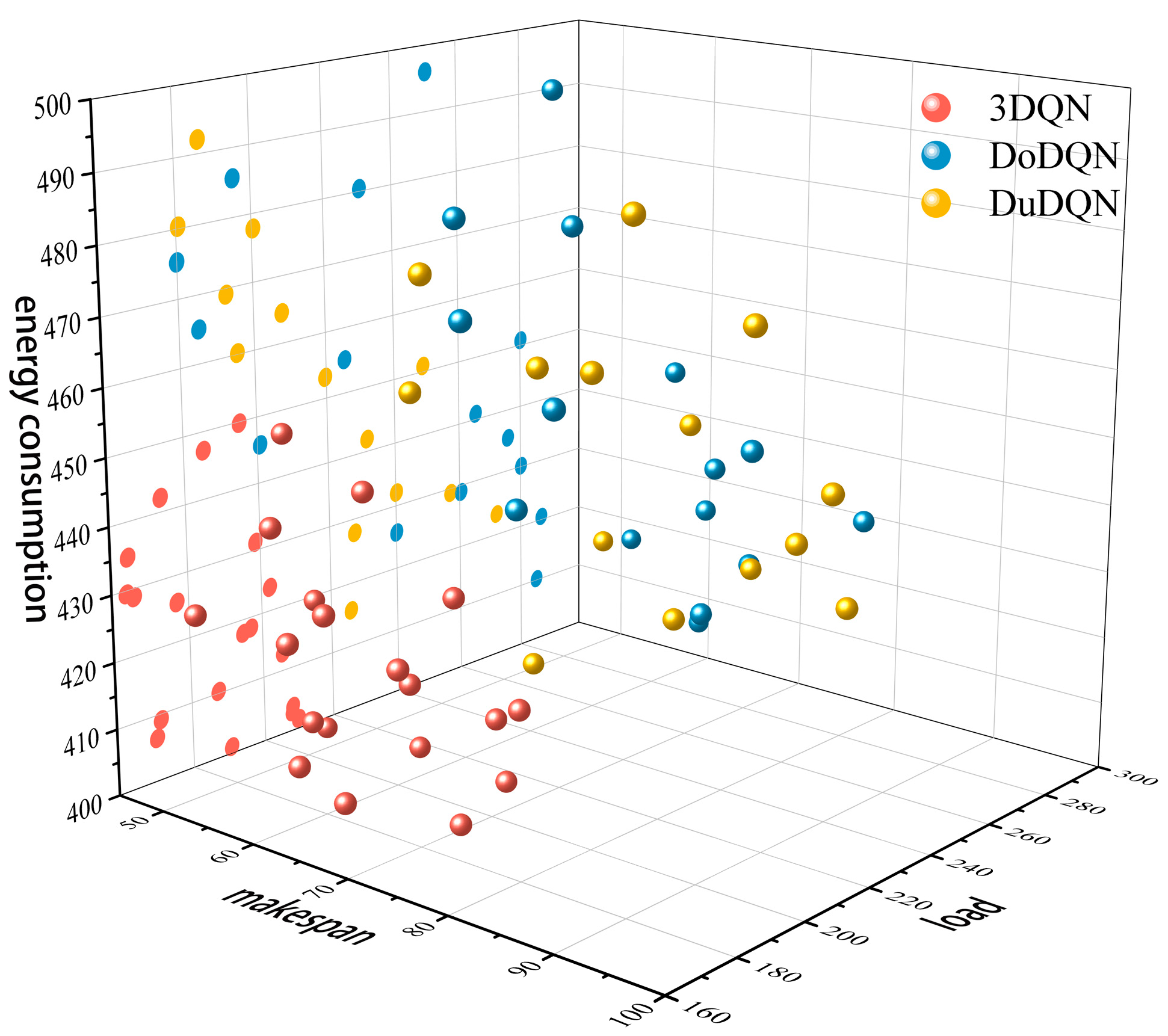

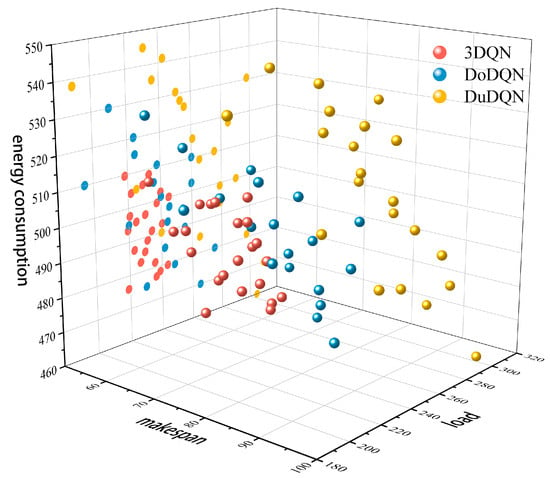

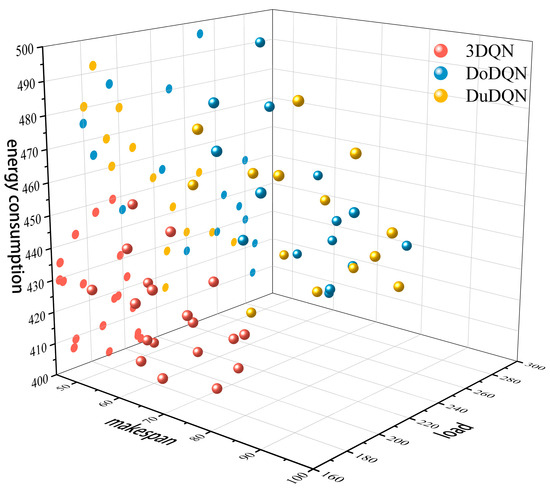

To further validate the effectiveness of the multi-agent deep reinforcement learning algorithm proposed in this chapter for solving multi-objective dynamic scheduling problems, comparative experiments incorporating dynamic perturbation events were conducted based on DoDQN and DuDQN algorithms. Figure 6 and Figure 7 display the Pareto front solutions of three algorithms on the MK01 benchmark instance after introducing dynamic perturbations. The figure demonstrates that under mechanical fault disturbances, the 3DQN algorithm exhibits superior convergence and uniform distribution of solution sets in both energy consumption and maximum completion time dimensions. Its solution points are concentrated and evenly distributed, indicating the algorithm’s effective balance between energy efficiency and task completion time during mechanical failures. In contrast, the solution sets of DoDQN and DuDQN algorithms show relatively dispersed characteristics. When subjected to order insertion disturbances, the 3DQN algorithm maintains high convergence and uniform distribution. Its solution points exhibit balanced distribution across energy consumption and completion time dimensions, with overall performance outperforming the other two algorithms. In summary, the 3DQN algorithm demonstrates high convergence and uniform distribution when dealing with two dynamic disturbances: mechanical failures and order insertions. This indicates that the 3DQN algorithm exhibits strong robustness and adaptability, confirming the proposed solution for dynamic scheduling in this chapter has superior robustness. It can effectively optimize energy consumption and maximize completion time in complex dynamic environments.

Figure 6.

MK01 Instance Pareto-Front Diagram—Machine Failure.

Figure 7.

MK01 Instance Pareto-Front Diagram—Order Insertion.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically investigates multi-objective optimization and dynamic disturbance response in flexible workshop scheduling, employing deep reinforcement learning theory for detailed analysis. Through theoretical modeling, algorithmic refinement, and experimental validation, it provides innovative solutions for real-time scheduling decisions in intelligent manufacturing environments. Key achievements include:

- (1)

- This study optimizes maximum completion time, minimizes total energy consumption, and reduces overall mechanical load by introducing dynamic events (such as machine failures and order insertions) and implementing event-triggered rescheduling strategies. Two approaches, right-shift rescheduling and full rescheduling, are employed to address these challenges, achieving dynamic decoupling of scheduling decisions and global optimization.

- (2)

- A multi-agent collaboration mechanism was designed to decouple the strong coupling between process prioritization and machine allocation through division of labor between workpiece selection agents and machine assignment agents. The 3DQN algorithm was introduced to optimize Q-value function estimation, combining the state-action decoupling advantage of DuDQN with DoDQN’s capability to prevent overestimation of Q-values. Hierarchical experience replays and target network synchronization mechanisms were adopted to enhance the stability of the algorithm training process.

- (3)

- Simulation experiments demonstrate that the 3DQN algorithm outperforms traditional DoDQN and DuDQN algorithms in Pareto frontier solution distribution across standard test cases for scenarios involving machine failures and emergency order insertions, particularly when combined with event-triggered rescheduling strategies (right-shift rescheduling and full rescheduling). The results indicate that the full rescheduling strategy can significantly reduce completion time under sudden disturbances, achieving a balance between production flexibility and efficiency.

Future research can be extended to more complex production environments, such as multi-plant collaborative scheduling and incorporating dynamic disturbances like raw material shortages or equipment aging. We should explore more efficient deep reinforcement learning algorithms and optimization strategies, such as integrating transfer learning and federated learning, to enhance the convergence speed and generalization capability of algorithms in large-scale complex scheduling problems. This will further improve the real-time responsiveness and robustness of scheduling systems. By validating the effectiveness and practicality of these algorithms through real-world production cases and optimizing them based on application feedback, we can drive advancements in intelligent manufacturing and boost production efficiency. and resource utilization efficiency.

Author Contributions

Validation, Q.W.; Formal analysis, J.W. and Q.W.; Data curation, Q.W.; Writing—original draft preparation, Q.W. and J.W.; Writing—review and editing, R.L. and J.W.; Supervision, R.L.; Project administration, R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province] grant number [2023C01213].

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The study primarily utilized standard benchmark problems for the Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem (FJSP) as described in the literature, which are publicly available in the scheduling research community. The processed data and experimental results generated during this study are also available upon request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/research, the author utilized [Quark AI, version 4.7.0] for text translation and polishing. The author has reviewed and edited the content of this publication and takes full responsibility for it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Zhou, J. Intelligent manufacturing—Main direction of “Made in China 2025”. China Mech. Eng. 2015, 26, 2273–2284. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. Research on Multi-Objective Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Model and Evolutionary Algorithm. Master’s Thesis, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China, 2018; pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bragin, M.A.; Luh, P.B.; Yan, J.H.; Yu, N.; Stern, G.A. Convergence of the surrogate Lagrangian relaxation method. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2015, 164, 173–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xu, J.; Ge, J.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Z. Multi-task multi-agent reinforcement learning for real-time scheduling of a dual-resource flexible job shop with robots. Processes 2023, 11, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Qiu, B.; Shan, J.; Long, Q. Vehicle routing optimization and algorithm research considering driver fatigue. Ind. Eng. 2023, 26, 132–140, 184. [Google Scholar]

- Brucker, P.; Schlie, R. Job-shop scheduling with multi-purpose machines. Computing 1990, 45, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Liao, X.; Chen, G.; Chen, Y. Co-evolutionary NSGA-III with deep reinforcement learning for multi-objective distributed flexible job shop scheduling. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 203, 110990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Lei, D.M.; Wang, K.P. An enhanced Q-learning-based artificial bee colony algorithm for green scheduling in distributed flexible assembly workshops. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2024, 29, 166–179. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.; Ye, C. A hybrid distribution estimation algorithm is proposed to solve the distributed flexible shop floor scheduling problem. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2024, 33, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pezzella, F.; Morganti, G.; Ciaschetti, G. A genetic algorithm for the flexible job-shop scheduling problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 2008, 35, 3202–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J. Research on Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Method Based on Multi-Agent. Master’s Thesis, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei, China, 2023; pp. 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, T.Z. Flexible Job Shop Energy Efficiency Scheduling Optimization Based on DQN Cooperative Coevolution Algorithm. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2023; pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Gao, L.; Shi, Y. An effective genetic algorithm for the flexible job-shop scheduling problem. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 3563–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.N.; Chen, Y.W.; Wang, P.; Zhao, Q.S.; Xiong, J. A knowledge-based ant colony optimization for flexible job shop scheduling problems. Appl. Soft Comput. 2010, 10, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.W.; Hu, M.Z.; Li, J.W.; Zhang, J. Machine-AGV collaborative scheduling in flexible job shop based on multi-agent non-cooperative evolutionary game. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 41, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.Y.; Chen, J.Q.; Wang, L.Q.; Xu, W.H. Scheduling optimization of mixed-model assembly lines for machine tools based on deep multi-agent reinforcement learning. Ind. Eng. J. 2025, 10, 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.F.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.L. Research progress on multi-agent deep reinforcement learning and its scalability. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2025, 61, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Liu, Z.J.; Hong, Y.T.; Wang, J.C.; Wang, J.R.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y. A survey on games based on multi-agent reinforcement learning. Acta Autom. Sin. 2025, 51, 540–558. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.Y. Optimization of cruising taxi scheduling strategy based on multi-agent deep reinforcement learning mechanism. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2024, 53, 778. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, Y.W.; Li, W.J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, G.X. Research on LEO constellation beam hopping resource scheduling based on multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. J. Commun. 2025, 46, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblet, D.; Thevenin, S.; Dolgui, A. Makespan estimation in a flexible job-shop scheduling environment using machine learning. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 3654–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, H.; Hijazi, M.; Brahmia, M.E.A.; Idrees, A.K.; AlAkkoumi, M.; Jaber, A.; Abouaissa, A. An intelligent mechanism for energy consumption scheduling in smart buildings. Clust. Comput. 2024, 27, 11149–11165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.G.; Zhang, L.H.; Wang, X.Y.; Wang, J.B. Single machine scheduling proportionally deteriorating jobs with ready times subject to the total weighted completion time minimization. Mathematics 2024, 12, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Huang, J. An improved DQN path planning algorithm. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 616–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Noguchi, N.; He, Y. Obstacle avoidance method based on double DQN for agricultural robots. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 204, 107546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).