Abstract

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are characterized by their ability to repel both grease and water, properties that led to their initial development as surfactants and surface protectors. As novel PFAS alternatives emerge and are detected in the environment, these substances present significant challenges related to environmental media, human exposure, and health risk assessments. This article reviews current knowledge on the origins of PFAS and their pathways from production facilities and PFAS-containing products to environmental organisms and humans and summarizes existing data on toxicity and toxicological mechanisms in laboratory animals and examines associated adverse health outcomes in humans through various epidemiological studies. Although risk assessments of PFAS alternatives are complicated by unclear chemical structures and complex effects, quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) models and prioritization approaches offer potential strategies for PFAS management. A comprehensive understanding of the environmental behavior and toxicology of novel PFAS will enhance their management and improve human health risk assessments.

1. Introduction

The history of fluorinated compounds, known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), began in the 1940s [1]. The chemistry industry developed surfactant compounds with a unique ability to repel both grease and water due to their carbon chains being enveloped in fluorine atoms. The carbon–fluorine bond is the most stable bond known in nature, contributing to the durability of PFAS [2]. Consequently, PFAS are found in many everyday items, such as non-stick pans, raincoats, packaging of food, firefighting foams, and various stain-resistant coatings [1,3]. By the 21st century, increased concentrations of two prominent fluorochemicals—perfluorooctanic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), and 8:2 fluorotelomer alcohol (8:2 FTOH), the precursor of PFOA—raised concerns regarding health issues, including cancers [4] and pregnancy complications [5]. Since 2005, legislation and regulation of PFOA and PFOS have been continuously strengthened, with industry phase-out and revised safety limits. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) now recommends a combined Tolerable Weekly Intake (TWI) of 4.4 ng/kg bw/week for the sum of PFOA, PFOS, perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), and perfluorohexane sulfonic acids (PFHxS), according to its 2024 Scientific Opinion [6]. Today, the challenge is not only to regulate traditional PFAS but also to further investigate the environmental behavior and health toxicity of emerging PFAS.

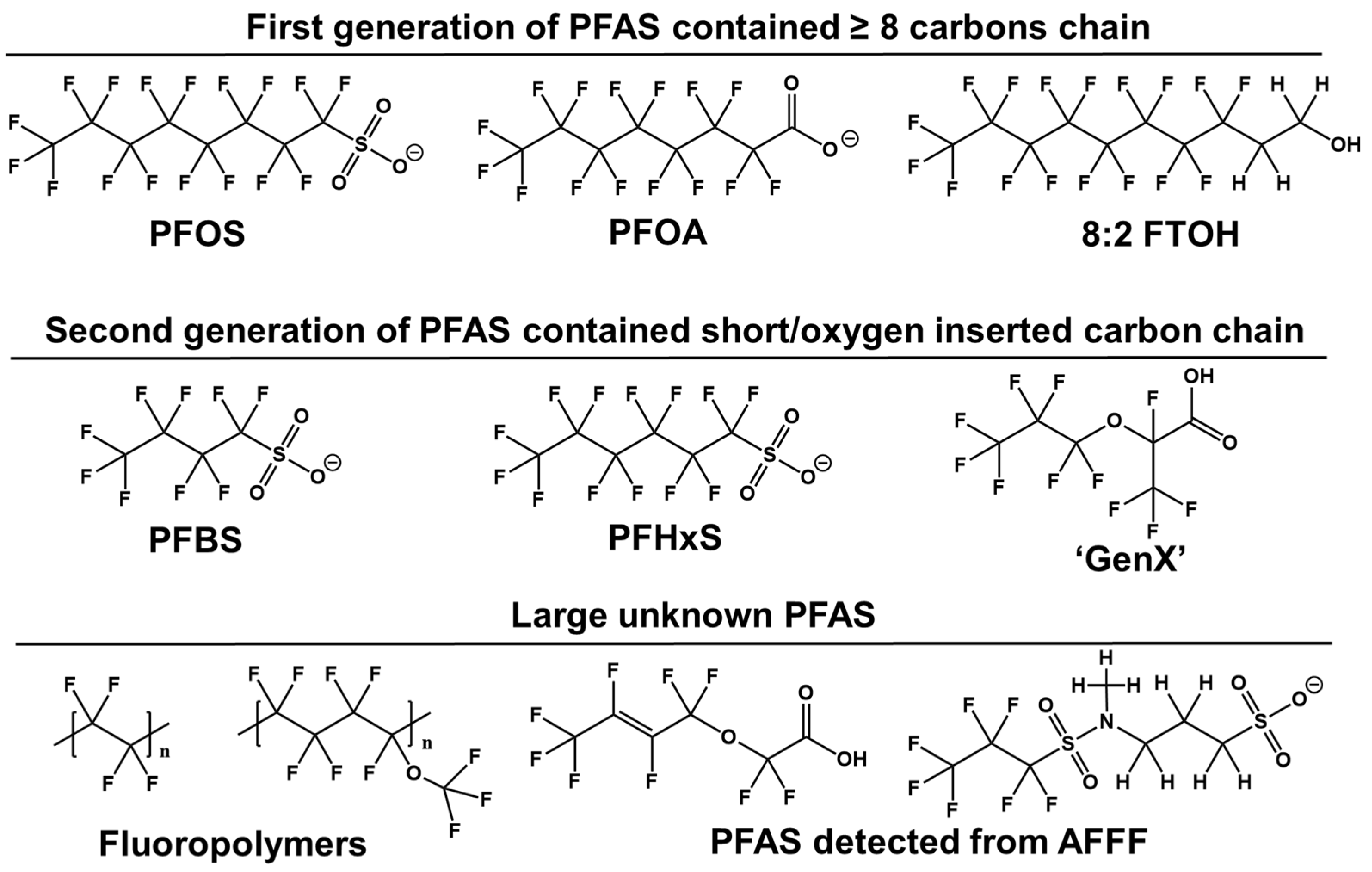

Novel PFAS molecules exhibit diverse structures, which chemical firms assert are less problematic than PFOA or PFOS (Figure 1). Research indicates that reducing the persistence and bioaccumulation of PFAS can be achieved by shortening the perfluorocarbon chain length or inserting oxygen atoms in the fluorinated carbon chain [7]. This includes compounds such as six-carbon PFHxS, four-carbon perfluorobutane sulfonic acids (PFBS), and an oxygen-containing hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (GenX). These structural modifications can enhance solubility and degradability, facilitating faster clearance from the bloodstream and accelerating perfluoroalkyl breakdown [8]. Both manufacturing and environmental degradation processes have led to an increase in perfluoroalkyl compounds with varied structures. However, PFAS with known structures detected in the environment represent only a fraction of the perfluoroalkyl family. Many unidentified substances remain, necessitating non-target analysis (NTA) [9]. Furthermore, limited communication between researchers and PFAS-producing companies complicates the identification of these compounds as either intended ingredients, residual intermediates, by-products, or degradation products from fluoropolymers.

Figure 1.

Structural characteristics of the perfluorinated compounds.

Water systems, airborne particulate matter, soil, and the food supply are significant sources of residual PFOA/PFOS and emerging PFAS contaminants [7]. Additionally, firefighting foams used at fire scenes and training areas often contain complex formulations with hundreds of PFAS compounds [10,11]. The widespread application of high-resolution spectrometers over the past decade has revealed an increasing number of previously unrecorded PFAS types in the environment. By detecting PFAS at their sources, in environmental media, and at various levels in the food chain, we can trace the exposure history of specific PFAS as they transition from industry sources to ecosystem and humans. It has been reported that adults primarily encounter PFAS through ingestion of dust and food, inhalation of air, and consumption of drinking water [12,13]. In addition, fetuses and infants can be exposed to PFAS via transplacental transfer during pregnancy and through breastfeeding during early life [14,15,16].

Bioaccumulation is a critical characteristic of PFAS, particularly concerning humans who are at the top of the food chain. To fully comprehend PFAS behavior within the body, it is essential to understand their biodistribution, target organs, tissues, and individual cells. Unlike traditional lipophilic pollutants, which primarily accumulate in body fat, hydrophobic and oil-phobic PFAS tend to accumulate in the blood and liver [17]. In toxicology, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα)-mediated signaling pathway is a well-established mechanism of action [18]. However, this pathway does not adequately account for all the toxic effects of long-chain PFAS (with eight or more carbons). Consequently, many conclusions need to be re-evaluated for novel PFAS alternatives, particularly regarding their altered properties. While the incorporation of oxygen atoms and the shortening of the perfluoroalkyl chain have been suggested to reduce persistence and clearance time in vivo [19,20]. The bioaccumulation and toxicity of these modified PFAS still require further investigation.

The risk assessment and characterization of PFAS alternatives should be conducted urgently. The use of such replacements, without a thorough understanding of the environmental fate and transformation of PFAS in vivo, poses significant potential problems. Historically, replacements for banned or phased-out chemicals have often involved structurally similar compounds. For instance, chlorinated paraffins replaced polychlorinated biphenyls, halogenated flame retardants replaced polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and bisphenol S partially replaced bisphenol A in certain applications. While these straightforward replacement strategies can be cost-effective in the short term, they may lead to unforeseen issues if the alternatives prove to be as toxic as their predecessors. Unlike the relatively few known chemical pollutants, such as 209 polychlorinated biphenyls and 75 dioxins, the development of PFAS alternatives presents a much larger challenge. Studies have shown that the fluorine-containing compounds of these substitutes are difficult to degrade and may form persistent end-conversion products, such as certain perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs) and perfluoroalkanesulfonic acids (PFSAs) [21,22,23]. Many short-chain PFAS (with fewer than eight carbons) are still unidentified due to unclear sources, which could include degradation products or by-products [24,25]. This uncertainty complicates the assessment of the toxicity of short-chain PFAS, particularly regarding long-term effects. Additionally, the sustained release of these compounds suggests that side effects may occur.

Several authors have reviewed the toxicological effects and epidemiological studies of PFAS [26,27,28,29,30]. However, most of these reviews focus primarily on PFOA and PFOS, examining their exposure pathway, toxicological effect, and the health risk assessment. Given the uncertainty surrounding novel PFAS alternatives, there is a need for comprehensive summaries and corresponding mitigation strategies. In this article we review the current understanding of PFAS alternatives, including their exposure pathways, potential mechanisms of toxicity, and risk assessment approaches. Due to the limited data on PFAS alternatives, some findings related to PFOS and PFOA are also used to support summarization and prediction analyses.

2. Why PFAS Are Termed “Forever Chemicals”?

PFAS and their alternatives have been widely, but controversially [31], used in virtually every recognized industry over the past century, including adhesives, ammunition, cleaning products, construction, electronics, fertilizers, firefighting foam, manufacturing, medical devices, mining, oil and gas, paints, pesticides, propellants, refrigerants, semiconductors, textiles, transportation, varnish, and much more [32]. However, these chemicals have long half-lives in various degradation studies and can be persistent in the environment for long periods of time. Therefore, they are colloquially known as “forever chemicals” [33]. This part examines several reasons why PFAS persist and accumulate, focusing on their structural properties, active production, and passive generation.

2.1. The Structural Properties of PFAS

The presence of one or more -CF2- moieties is the most distinctive feature of PFAS, contributing to their high persistence in natural conditions [34]. The small size and high electronegativity of the fluorine atom lead to significant bond strength and spatial occupancy when forming carbon–fluorine bonds and perfluoroalkyl chains (CnF2n+1−, F-alkyl). For a certain chain length, a liner F-alkyl chain has approximately 50% more cross-section area than an alkyl chain (27–30 Å2, vs. 18–21 Å2) [34]. The C-F bond with a bond dissociation energy of about 485 kJ·mol−1 is the strongest single bond known in organic chemistry [34], compared to C-H bond at approximately 413 kJ·mol−1. Additionally, the high polarization caused by fluorine’s electronegativity makes C-C bonds significantly stronger in fluorocarbons than in hydrocarbons, contributing to the chemical, thermal, and biological stability of PFAS [34]. Although short-chain fluorinated carbon chains and fluorinated chains with inserted oxygen atoms can partially degrade in the environment and biota, they will transform into more stable end products that accumulate in favoring mediums [35,36,37]. These compounds have been widely detected in the environment in recent years, raising health concerns [38,39,40,41].

Water solubility is another critical feature of certain PFCAs and PFSAs, as water currents and aerosols serve as effective carriers for their long-distance transport. A few fluorochemical companies contribute a large proportion of the global emissions of specific PFAS. Studies have highlighted emissions from fluoropolymer production facilities, with elevated PFAS levels detected in communities located hundreds of miles downstream of plants, such as those along the Ohio River [38]. The use of PFAS-containing aqueous film-forming (AFFF) for fire suppression or training at military facilities and airports has contaminated many aquatic and terrestrial environments [10,11,39]. Wastewater treatment plants receive PFAS through discharged and inflowing treated biosolids and waste [40]. For instance, higher concentration of PFAS in the U.S. public drinking supplies have been significantly associated with the number of sewage treatment plants within a watershed [41].

Certain ionic PFAS exhibit high solubility and protein-binding characteristics, facilitating their bioaccumulation. Unlike traditional lipophilic organic pollutants, which tend to accumulate in adipose tissue, ionic PFAS typically bind with blood proteins such as albumin and liver fatty acid binding protein (L-FABP). Beyond this shared ionic behavior, recent mechanistic studies show that the polar functional group modulates tissue distribution, with PFSAs exhibiting higher liver–blood partition coefficients and bioaccumulation potentials than PFCAs of similar chain length [42]. Bioaccumulation is further influenced by the length of the perfluorocarbon chain. Evidence suggests that reducing the number of the perfluorocarbon units can accelerate PFAS elimination and decrease the accumulation in vivo. These findings have increased interest in developing PFAS alternatives with fewer fluorinated carbons. Although short-chain PFAS are marketed as a better choice due to their reduced persistence in tissues, subsequent toxicological studies have shown that they are equally persistent in the environment [43], more mobile [28], and more difficult to remove from water system [44,45] compared to long-chain PFAS.

2.2. The Demand and Development of Novel Products

As Halden said, “The irony is that the polyfluorinated chemistry is kind of magic. If they weren’t that useful, it’d be easy to say goodbye.” It is evident that PFAS are a potentially toxic class of chemicals associated with several serious health conditions. Despite this, they are ubiquitous in daily life. PFAS serve various functions, including repelling water and oil, acting as surfactants, providing lubrication, and preventing corrosion. Consequently, they are extensively used in consumer products such as nonstick pans, raincoats, food packaging, firefighting foams, and various stainproof coatings [1,3].

PFAS are manufactured for direct use in commercial products and for use in industrial processes [8,46]. However, information about PFAS emissions from manufacturing or processing facilities is often unavailable due to trade secrets. Significant efforts and resources have been invested to identify, understand, and, in some cases, control exposure to long-chain PFAS [47]. As a result, after more than 50 years of production, PFOA, PFOS, and their precursors have been phased out.

Driven by urgent demand and economic considerations, various replacements to traditional PFAS have been developed. Currently, replacements to PFAS include two main categories: short-chain PFAS, including perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA), PFBS, perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), and other short-chain analogs, which have greater persistence and mobility in aquatic systems compared to long-chain PFAS, posing a greater potential threat to human and environmental health [48,49,50,51]. Another type is the insertion of oxygen or chlorine atoms into the fluorocarbon chains: GenX, a representative member of perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids (PFECAs), is widely used as a high-performance alternative to PFOA [52]; chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonates (Cl-PFESA) have been widely used as an anti-fogging agent in the chrome plating industry in China as one of the alternatives to PFOS [53].

2.3. The Passive Generation of PFAS By-Products

The primary challenge is the lack of comprehensive information regarding the passive generation of PFAS by-products. In environmental media, fewer than 50 individual PFAS (often fewer than 10) are commonly measured [1]. Most PFAS chemicals remain poorly understood. By-products from the production process and degradation products of PFAS in the environment, including the shedding and evolution of fluoropolymer side chains, further complicate efforts to fully understand PFAS structures and quantities.

Fluoropolymers with high molecular weight consist of molecular segments (monomers) that may be linked together, sometimes resulting in polymers with hundreds of thousands of linked monomers. They pose a particularly challenging case: fluorochemical producers assert that fluoropolymers should be separated from PFAS for threat assessment and are considered relatively safe. However, the manufacture of fluoropolymers contributes significantly to environmental PFAS contamination, including releases of both intentionally added processing aids and accidental PFAS by-products [54,55,56]. Estimations suggest that approximately 80% of PFCA in the environment have originated from fluoropolymer production and use [57]. During emulsion polymerization, long- and short-chain PFAAs or ether-based alternatives (e.g., PFOA, PFNA, and GenX [57]) have been widely used as polymerization aids, and incomplete polymerization can leave residual monomers, oligomers, and other synthesis by-products that are emitted with wastewater and off-gases from manufacturing sites [55,58,59,60,61]. Additional low-molecular-weight PFAS, including PFAAs and various ether acids, can leach from finished fluoropolymer products during processing and use, leading to contamination of food and drinking water [62]. At the end of the product life cycle, disposal by landfilling and incomplete combustion further releases and transforms fluoropolymers into smaller, highly mobile PFAS, such as short-chain PFCAs, thereby extending and perpetuating their contribution to global PFAS pollution [63,64].

Fluoropolymer analysis currently relies on a combination of techniques, including pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (PyGC-MS), high-resolution mass spectrometry, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to identify polymers, quantify organically bound fluorine, and characterize degradation or by-product species [65,66,67]. However, these approaches are fragmented, technically demanding, not yet suitable for routine large-scale monitoring, and often sacrifice molecular-level resolution and comprehensive coverage across diverse fluoropolymer chemistries and matrices. As a result, the lack of standardized, widely applicable analytical methods severely limits exposure assessment and health-risk quantification for fluoropolymers and their by-products and undermines the development of coherent regulatory frameworks, including decisions on whether fluoropolymers should be treated as “polymers of low concern” or as part of the broader PFAS class.

3. Environmental and Health Concerns

3.1. Environmental Exposure and Transmission

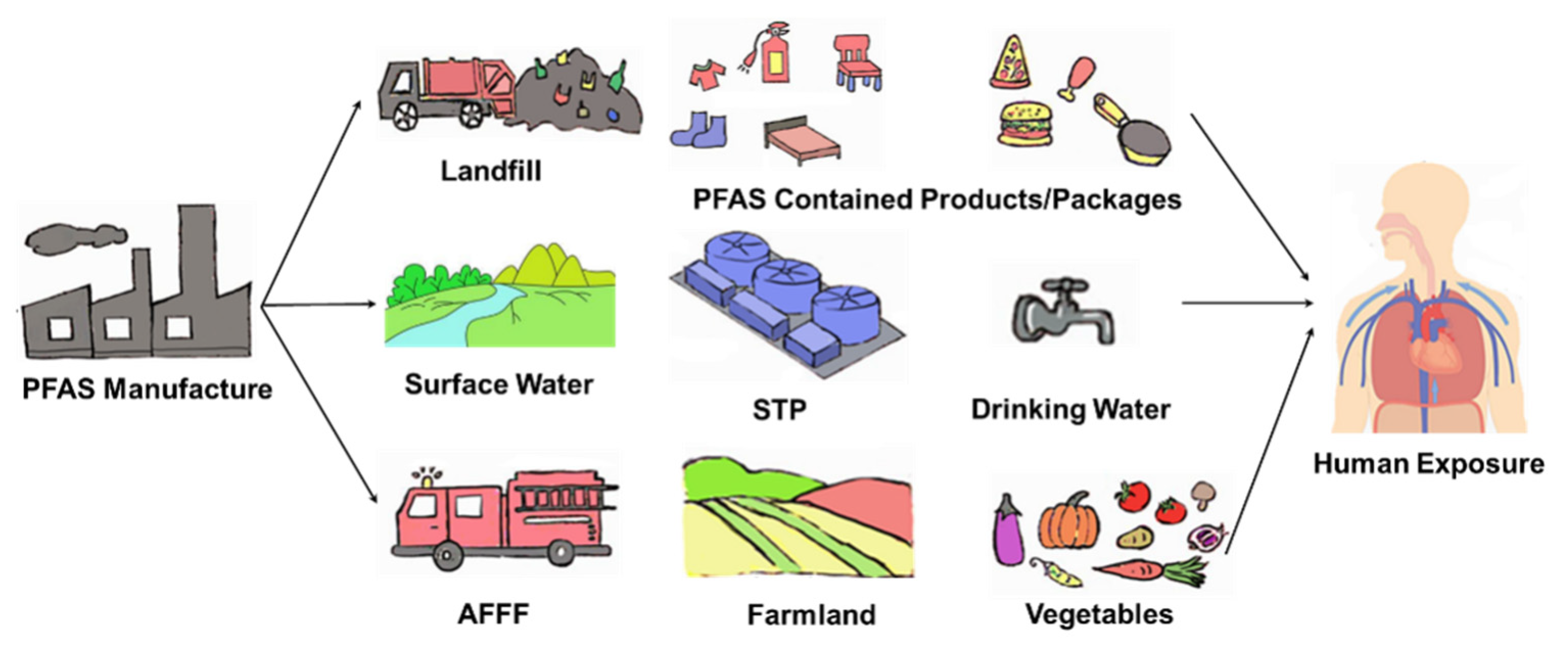

Persistence is a fundamental characteristic of PFAS, rendering them highly stable in both the environment and living organisms. Global emission estimates suggest that high molecular weight perfluoroalkanes have lifetimes spanning hundreds of years [68]. Although long-chain PFAS, such as PFOS and PFOA, have been phased out or restricted, they continue to be detected in environmental and biological media worldwide, including serum samples from the general population [69]. Replacement PFAS, including PFBA, PFBS, and GenX, are also commonly found in surface water and groundwater [45,52,56]. Contaminated soil and water lead to the accumulation of these chemicals in plants [70], vegetables [40], and food crops [71]. The transfer of PFAS through the food chain posed a significant threat to higher predators, such as bears, whales, and humans [72,73,74,75,76]. Over time, once the toxic threshold is reached, PFAS exposure can become a serious health issue [77] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PFAS exposure pathway from the technosphere and contamination sources to humans. AFFF, aqueous film-forming foam. STP, sewage treatment plant.

Ionized PFAS can adhere to sediment and atmospheric particles or dissolve in ocean water, facilitating long-distance transport via monsoons and ocean currents [78,79,80]. High concentrations of PFAS have been detected in polar bears [76]. Their high aqueous solubility and extreme persistence make removal from water particularly challenging. Advanced treatment technologies such as granular activated carbon, ion exchange resins, reverse osmosis, and novel functionalized sorbents can substantially reduce PFAS concentrations in water and are particularly effective for long-chain legacy PFAS [81]. However, their performance is generally poorer for the increasingly detected, more hydrophilic short-chain and emerging PFAS, and implementation can still be constrained by cost and operational complexity [82]. As a result, PFAS can pass through treatment systems and continue to be transported within and between environmental compartments, sustaining long-term environmental exposure.

3.2. Adverse Health Outcomes

The extreme persistence and solubility of PFAS lead to their continuous accumulation in both organisms and humans, potentially resulting in adverse health effects. Exposure pathways include the ingesting of contaminated food and drinking water, inhalation of dust and fine particulate matter containing PFAS, and dermal contact with cleaning or personal care products [83,84]. Due to the lack of in vivo biomarkers, blood serum concentration is used to assess exposure levels. Elevated PFAS concentrations have been detected in the serum of factory workers and residents living near perfluoroalkyl facilities compared to the general population [85]. A correlation between indoor exposure media and serum PFAS concentration can provide insights into “background” exposure levels in the general population, which are crucial for risk assessments and human health studies.

The primary toxicity effects of PFAS observed in laboratory animals include liver toxicity [86], developmental toxicity [87], and immune toxicity [14,88]. In terms of liver toxicity, both PFOA and its substitute GenX exhibit hepatotoxic effects, although with distinct mechanisms [89]. PFOA exposure is associated with liver damage through activation of liver stress-related genes and metabolic dysregulation, while GenX exposure leads to similar hepatotoxic effects but with more pronounced changes in bile acid metabolism and additional metabolic pathway alterations. Both compounds result in liver enlargement, increased serum liver enzymes, and histopathological liver changes in offspring, but GenX exposure also shows increased DNA damage and cell cycle disruption. PFOS and its substitute, Cl-PFESAs (commercially known as F-53B), display broad endocrine-disrupting potential, encompassing estrogen receptor activation, sex-hormone imbalance, gonadal pathology, and wider perturbations of hormonal regulatory systems that collectively contribute to developmental and neurological impairments [90,91]. Emerging evidence indicates that Cl-PFESAs possess stronger and more persistent endocrine toxicity than PFOS [92]. Regarding immunotoxicity, PFAS-induced responses increased with carbon chain length, as evidenced by elevated macrophage and neutrophil numbers, weakened antibacterial defense, and activation of the TLR/MyD88/NF-κB pathway [93].

While the cellular mechanisms underlying hepatic effects have been extensively studied, data on mechanisms for other effects are limited. Comprehensive analysis of toxicological data indicated that PFAS induce [94] a range of adverse effects by activating the PPARα [95]. However, some adverse effects of PFAS occur through PPARα-independent mechanisms, such as activation of other nuclear receptors, increased oxidative stress, dysregulation of mitochondrial function, and inhibition of gap junction intercellular communication. These toxic mechanisms and related effects are summarized in Table 1. Notably, high levels of 6:2 FTOH metabolites have been detected in human organs [96], challenging the notion that short-chain PFAS lack accumulation capacity and suggesting differences in metabolism between humans and rodents. This discrepancy highlights a significant limitation in using animal data to assess PFOS risk. Additionally, evidence suggests that short-chain PFAS may be more bioaccumulative in humans than previously thought, potentially impacting preliminary safety assessment [97]. Given the variability and uncertainty in PFOS toxicity across species and research types, traditional risk assessment methods face multiple challenges. Establishing a robust probabilistic risk assessment framework that accounts for interspecific and inter-experimental variation and deriving the human equivalent dose (HED) and reference dose of PFOS is crucial. Mechanism-driven information is essential for developing a comprehensive toxicological profile and facilitating in vitro to in vivo extrapolation, which enhances the risk assessment process [98]. Studies have demonstrated specific bioaccumulation of PFAS in the human brain [94,99] and significant effects of PFOA exposure during neurodopaminergic differentiation, underscoring the need for investigation methods directly related to chemical risk assessment [100].

Epidemiological studies have been utilized to investigate the associations between PFAS exposure and adverse health outcomes in highly exposed occupational cohorts, communities living near PFAS manufacturing sites, and general populations with background-level exposure. The available epidemiological evidence indicates associations between the PFAS exposure and several health outcomes, including hepatic toxicity, developmental and reproductive toxicity, immunotoxicity, neurotoxicity, endocrine disruption, and carcinogenicity. Most of these studies were observational. For instance, one cross-sectional study conducted from 1999 to 2000 found that elevated levels of PFOA in adult serum (n = 2216, PFOA: 354 ng·mL−1) were associated with increased liver enzyme levels [101]. Another cross-sectional study found that both behavior regulation and metacognition impairment were linked to serum PFOS levels (12.3 ng·mL−1) in a cohort of 256 mother–child pairs [102]. Longitudinal studies also provide valuable insights; one study examined the association between reduced female birth weight at 20 months and mothers’ prenatal PFOS exposure (n = 447, PFOS: 19.6 ng·mL−1) from 1991 to 1992 [103]. Additionally, prenatal and early infancy exposure to PFAA (median serum level: PFOS 4.7 ng·mL−1, PFOA 2.2 ng·mL−1, PFNA 1.1 ng·mL−1, PFDA 0.3 ng·mL−1, and PFHxS) was associated with impaired antibody responses in a cohort of 490 children born between 2007 and 2009 at the National Hospital of Faroe Island. Finally, a case–control study of 31 breast cancer cases (2000–2003) from various Greenlandic districts revealed an association with median serum levels of PFOS (31.6 ng·mL−1) and PFOA (2.5 ng·mL−1) [104].

In summary, current evidence indicates that legacy PFAS and their alternatives (e.g., GenX, Cl-PFESAs, and short-chain homologues) can elicit comparable or even greater liver, endocrine, and immune toxicities through distinct yet overlapping mechanisms. Some epidemiological findings on PFAS align with results from toxicological findings. However, these findings have limitations. First, most health outcomes were only linked to serum concentrations of PFAS, particularly PFOA and PFOS [105]. Strengthening the correlation between internal exposure dose and effect on target organs is necessary. Second, the predominance of observational studies limits the generalizability and accuracy of conclusions due to methodological constraints and sample sizes. As the number of PFAS increases, research must also address the associations between health outcomes and PFAS mixtures. Additionally, it is essential to investigate how genetic characteristics, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, susceptible population, and underlying conditions might influence the risk for PFAS-related health outcomes.

Table 1.

The toxic mechanisms and related effects caused by PFAS.

Table 1.

The toxic mechanisms and related effects caused by PFAS.

| Mechanisms | Related PFAS | Toxic Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPARα | PPARα Receptor Activation [106,107,108,109,110] | PFOA, PFBA, PFOS, PFUA, PFHpA, PFDoA, ADONA | Hepatocellular hypertrophy, Peroxisomal fatty acid β oxidation, Cytochrome 450-mediated ω hydroxylation of lauric acid, lipid metabolism abnormal |

| PPARα-Dependent Gene Expression Changes [111,112,113] | PFOA, PFNA, GenX, ADONA | Gene expression changed of fatty acid metabolism, cell cycle control, peroxisome biogenesis, proteasome structure and organization, decreasing cell viability and proliferation | |

| PPARα-Independent | Activation of Other Nuclear Receptors [92,114,115,116,117,118,119] | PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, PFHxS, PFDA, Cl-PFESAs, GenX | The activation of PPARγ, CAR, ERα, PXR, FXR, VDR, and LXRα, impairment of bile acid mechanism |

| Oxidative Stress [120,121,122,123,124,125] | PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, PFBS, PFHxA | DNA damage, tumor promotion, perturbation of lipid homeostasis, stimulation of inflammation | |

| Gap Junction Intercellular Communication Inhibition [125,126,127,128,129] | PFOA, PFOS | Influences on the maintenance of tissue homeostasis, intercellular transmission of regulatory signals, and metabolic cooperation | |

| Impaired Mitochondrial Function [130,131,132,133] | PFOS, PFOA, PFBuS, PFHxA | Cellular respiration, mitochondrial membrane potential, Mitochondrial proliferation, oxidative phosphorylation | |

| DNA Methylation Disruption [90] | F-53B | Endocrine barrier disruption | |

PFUA: perfluoroundecanoic acid; PFHpA: perfluoroheptanoic acid; PFDoA: perfluorododecanoic acid; ADONA: 4,8-dioxa-3H-perfluorononanoic acid; PFDA: perfluorodecanoic acid; PFBuS: Perfluorobutane sulfonate.

4. Human Health Risk Assessment Related to PFAS

4.1. Non-Targeted Analysis

The continued development of alternatives to PFAS and the lack of relevant data have resulted in a wide range of industrial products and their by-products and degradation products containing PFAS, but only a few dozen are routinely monitored in the environment [12]. Together, legacy and alternative PFAS influence the health risks to humans and the environment [134,135]. Therefore, chemical analysis technology for monitoring and identifying PFAS is crucial for understanding their environmental fate and impact, as well as enhancing environmental supervision and treatment. Targeted analysis is suitable for routine environmental monitoring but is limited in the types of PFAS it can identify and monitor. NTA allows screening for unknown PFAS in the absence of authentic standards. By analyzing mass spectral fragments and comparing screening databases to deduce the structure of unknown PFAS, NTA has become a key technique for screening and identifying PFAS [136]. Non-targeted screening by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) is increasingly being used to complement traditional target analysis to detect unknown PFAS in a variety of environmental samples [137,138,139]. However, due to the lack of reliable references, the interference of complex matrix components, and the time-consuming data analysis and processing, the detection of non-targeted PFAS in biota samples is still challenging [140], and it is difficult to provide sufficient toxicological information for regulatory decision-making. There is an urgent need for a new approach to link NTA to toxicological evaluations.

4.2. Effect-Directed Analysis

Effect-Directed Analysis (EDA) has emerged as a tool that effectively links analytical detection to biological activity [141]. Unlike NTA, which generates a list of chemical features without identifying which may cause toxic effects, EDA begins by fractionating the sample into discrete chemical components. These fractions are then tested in vitro for biological activity, and the results guide further analysis using HRMS to identify the chemicals responsible for the observed effects.

Currently, only a few PFAS are routinely monitored using targeted chemical analyses, and it is practically impossible to target all relevant PFAS in the environment. EDA is particularly suitable for emerging PFAS because it circumvents the need for comprehensive standards and toxicological data by focusing analytical efforts on bioactive fractions, thereby enabling causal links between unknown PFAS and adverse effects to be established [142]. For example, an EDA of PFAS-contaminated sediments identified five novel transthyretin-binding PFAS based on transthyretin binding activity.

4.3. Exposure Method

Humans can be exposed to PFAS via three principal routes: oral, inhalation, and dermal. For the general population, ingestion of contaminated drinking water and food is regarded as the dominant pathway, whereas inhalation of PFAS-containing aerosols or dust and dermal contact with PFAS-containing consumer products may be important in specific occupational or microenvironmental settings. Quantitative, route-specific exposure data for humans are still limited; so much of the current understanding of exposure–response relationships comes from animal studies.

In experimental toxicology, PFAS have been administered to rodents via all three routes, and the external doses required to elicit measurable effects span several orders of magnitude (Table 2). Oral studies typically employ mg/kg body-weight doses, covering from 1.13 to 113 mg/kg/day in normal, pregnant, or allergic asthmatic murine animals [143,144,145,146]. Recently, exposure to environmentally relevant level of PFAS (ng-μg/L) in drinking water [147,148,149] has also attracted increasing attention. Inhalation experiments usually use brief but high airborne concentrations, for example, single exposures to 130–140 mg/m3 perluoroisobutylene (PFIB) for 5 min [150], or nose-only exposures to 0.5 mg GenX per animal for 1 or 14 days [151]. Dermal studies, by contrast, rely on relatively high surface doses (e.g., 12.5–50 mg/kg/day PFOA for 4 or 14 days, or 93.8–375 mg/kg PFBA for up to 28 days) [152,153] to overcome limited percutaneous absorption [154]. Together, these studies illustrate how the nominal external doses associated with adverse effects differ systematically across oral, inhalation, and dermal routes.

Table 2.

Exposure Pathways and Levels of PFAS Compounds.

These route- and dose-specific patterns highlight that external dose alone is an imperfect descriptor of PFAS toxicity. Because PFAS can cause specific toxic effects, the relationship between the administered dose and toxic response is not straightforward, and this relationship is partly defined by adsorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) [155]. Studies have shown that PFAS are absorbed through oral, inhalation, and dermal exposure [156,157], and because it is not possible to quantify partial absorption after inhalation or dermal exposure, most animal studies have been conducted with orally administered PFAS [143,158,159]. Biodistribution studies have shown that PFAS can be widely detected in the body, with the highest concentrations of PFAS found in the liver [144], kidneys [160], and blood [161]. In the blood, PFAS mainly bind to albumin and other proteins [162] and can be transferred to the fetus during pregnancy and to nursing infants. Available oral studies indicate that PFAS are not metabolized or chemically modified in the body. PFCAs, such as PFOA, are cleared predominantly via renal excretion into urine, whereas PFSAs, such as PFOS, undergo extensive enterohepatic circulation and show a greater contribution of biliary and fecal excretion [163]. Small fractions of both PFCAs and PFSAs have also been reported in breast milk [164]. However, the ADME of PFAS varies with genetic characteristics, race/ethnicities, socioeconomic statuses, susceptible populations, and underlying disease. These factors can affect conclusions about toxicity, interspecies extrapolations, and risks to human health and the environment. Therefore, it is crucial to consider substitution strategies for chemicals with similar modes of action but differing ADME properties. To advance understanding of intrinsic toxicity and improve animal-to-human extrapolation in PFAS risk assessment, internal dose, such as the amount of PFAS in the blood or at the target tissue, should be considered as dose descriptors.

4.4. Method Evaluation In Vitro

Dut to the discrepancies between the toxicity kinetics predicted by animal models for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances and the results from human studies, it is essential to evaluate the potential health effects of short-chain perfluorooctane sulfonate thoroughly. To achieve this, relevant data on the health effects of short-chain perfluorooctane sulfonate were obtained using high-throughput method supported by in vitro human cell models [165]. Data from these in vitro models, which are affected by interspecies variability, may serve as a better indicator of human response and can be used for the preliminary risk assessment of PFAS with limited toxicity data. The methods employed include cytotoxicity analysis, biotransformation, cell reaction and metabolism, and developmental toxicity. Although in vitro tests can identify the hazards of PFOS, the concentrations used may not accurately reflect potential in vivo effects, necessitating extrapolation to estimate the equivalent dose in vivo.

4.5. Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship

As a widely used synthetic chemical, PFAS are ubiquitous and are currently detected in soil, water, and a variety of food and food contact materials [166,167]. However, PFAS have been shown to be toxic to wildlife and humans; most data on PFAS toxicity are largely limited to PFOA and PFOS, whereas over 4700 different PFAS have been identified [166,167]. This diversity of PFAS compounds makes traditional risk assessment methods (i.e., evaluating each substance individually) time-consuming and expensive [167]. Therefore, the construction of quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models based on in vitro high-throughput screening data can help address the problem of a lack of PFAS bioactivity data.

Computer simulation modeling is a validated method for predicting toxicity and evaluating the mode of action (MOA) of specific endpoints [168,169,170]. As one of the computational methods widely used in virtual screening, QSAR modeling is based on the fact that the molecular structure of a chemical contains information about its biological properties, and it can be used to predict the biological properties of a chemical without the need for experiments, significantly reducing the time and cost associated with conducting biological experiments [170]. In a previous study QSAR was used to assess the change in toxicity of mixtures of single and binary PFAS and then to understand the MOA of the toxicity of the mixtures based on their synergism and additivity [137]. Experimental studies have shown that mixtures may have higher potential toxicity than simple sums of PFAS. QSAR modeling also confirms that carbon chain length plays a critical role in determining the toxic potency of PFAS [137]. In summary, the use of QSAR modeling has accelerated the toxicity assessment of emerging contaminants prevalent in the environment.

4.6. Prioritization Approach for PFAS Control

Given the large number of different PFAS present in the environment, there is a need to establish a risk-based guidance methodology for the toxicity assessment of PFAS to facilitate health assessments of PFAS. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Toxicology Program (NTP) have developed a prioritization approach based on chemical classes and have selected 75 PFAS for tiered toxicity and toxicokinetic testing [171]. To identify high-risk PFAS, Hu et al. developed a risk-based prioritization model to rank identified PFAS in surface water by combining hazard effects reflected in a toxicological prioritization index (ToxPi) with environmental exposure. The final list of prioritized PFAS includes legacy PFOA due to its high exposure and high hazard, and 10 PFAS were identified as medium priority that include PFOS, PFHpA, hydrogen-substituted perfluoroheptanoic acid (H-PFHpA), PFHxA, N-methyl perfluorobutane sulfonamidoacetic acid (MeFBSAA), sodium p-perfluorous nonenoxybenzene sulfonate (OBS), PFNA, PFBS, hydrogen-substituted perfluorodecanoic acid (H-PFDA), and hydrogen-substituted perfluoropentanoic acid (H-PFPeA) [172]. Prioritizing PFAS management based on observed or predicted toxicological properties and environmental fate is critical to developing effective risk management practices. For example, McDougall et al. evaluated 11 PFAS used in aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF) in firefighting training areas, using this rating calculation methodology, which showed that PFHxS, PFHpA, and 8:2 FTS were more hazardous than the other PFAS in AFFF [173]. This hazard rating system facilitates the selection and/or development of site management or remediation strategies.

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

The risk evaluation and exposure pathways of PFAS alternatives are reviewed in this research. Due to the widespread use of PFAS and their varying degrees of biotoxicity, numerous alternatives have been developed. However, the production and utilization of PFAS and their alternatives inevitably generate by-products and degradation products that may threaten ecological environment health due to their long half-lives, poor metabolisms profiles, and ability to persist over long distances within living organisms. Consequently, this review focuses primarily on assessing the risks posed by PFAS to human health. Although HRMS-based studies have revealed the complexity of the “PFAS world,” identifying novel PFAS through non-targeted HRMS analysis remains a significant challenge. It is crucial to acknowledge that the entirety of the “PFAS world” is poorly understood, and the known risks associated with PFAS are likely underestimated. Currently, most PFAS lack comprehensive toxicity data, necessitating further elucidation of new toxicity endpoints and mechanisms.

Given the substantial number of PFAS and the labor-intensive nature of traditional health risk assessment methods, this review proposes a machine learning (ML)-based QSAR approach. As an effective method for assessing PFAS risk that integrates human health and ecotoxicity, QSAR utilizes computational modeling to rapidly predict the toxicity of new chemicals. This capability aids policymakers and researchers in evaluating potential risks and ensuring compliance and safety. Furthermore, QSAR can facilitate clear prioritization of PFAS control and toxicity prediction, establishing a risk-based framework for PFAS toxicity evaluation and health assessment. Collectively, these efforts contribute to advancing research on PFAS-related health impacts and promoting public action to mitigate exposure effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. (Yin Liu); literature investigation, Z.Z., H.L., X.Y., and Y.L. (Ya Liu); writing—original draft, Y.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.L. (Yin Liu) and K.Z.; project administration, Y.L. (Yin Liu) and K.Z.; supervision, Y.L. (Yin Liu) and K.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.L. (Yin Liu) and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Shandong Engineering Research Center of Underground Resources and Environment High Precision Detection/Shandong Provincial Engineering Research Center for Geological Prospecting Open Fund Program (KY2025003) and the Research Funds of Hangzhou Institute for Advanced Study (2023HIASY015).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, Z.; DeWitt, J.C.; Higgins, C.P.; Cousins, I.T. A Never-Ending Story of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs)? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 2508–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapp, R. Fluorine. Encyclopedia of Toxicology, 2nd ed.; Wexler, P., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 343–346. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.S.; Buck, R.C.; Cousins, I.T.; Weis, C.P.; Fenton, S.E. Estimating Environmental Hazard and Risks from Exposure to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs): Outcome of a SETAC Focused Topic Meeting. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordner, A.; De La Rosa, V.Y.; Schaider, L.A.; Rudel, R.A.; Richter, L.; Brown, P. Guideline Levels for PFOA and PFOS in Drinking Water: The Role of Scientific Uncertainty, Risk Assessment Decisions, and Social Factors. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savitz, D.; Stein, C.; Dougan, M. Serum PFOA and PFOS and Pregnancy Outcome. Epidemiology 2009, 20, S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.T.; Shen, P.; Ang, W.M.; Lim, I.R.L.; Yu, W.Z.; Wu, Y.; Chan, S.H. Tap vs Bottled: Assessing PFAS Levels and Exposure Risks in Singapore’s Drinking Water. ACS EST Water 2025, 5, 4395–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chang, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, P. A review of sources, multimedia distribution and health risks of novel fluorinated alternatives. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 182, 109402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glüge, J.; Scheringer, M.; Cousins, I.T.; DeWitt, J.C.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lohmann, R.; Ng, C.A.; Trier, X.; Wang, Z.Y. An Overview of the Uses of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Environ. Sci.-Process. Impacts 2020, 22, 2345–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, N.; Qian, Y.; Shi, W.; Zhang, X.; Geng, J.; Yu, H.; Wei, S. Non-target and Suspect Screening of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Chinese Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water Res. 2020, 183, 115989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.H.; Long, G.C.; Porter, R.C.; Anderson, J.K. Occurrence of Select Perfluoroalkyl Substances at U.S. Air Force Aqueous Film-forming Foam Release Sites Other Than Fire-training Areas: Field-validation of Critical Fate and Transport Properties. Chemosphere 2016, 150, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzen-Hanson, K.A.; Roberts, S.C.; Choyke, S.; Oetjen, K.; McAlees, A.; Riddell, N.; McCrindle, R.; Ferguson, P.L.; Higgins, C.P.; Field, J.A. Discovery of 40 Classes of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Historical Aqueous Film-Forming Foams (AFFFs) and AFFF-Impacted Groundwater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 2047–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Silva, A.O.; Armitage, J.M.; Bruton, T.A.; Dassuncao, C.; Heiger-Bernays, W.; Hu, X.C.; Kärrman, A.; Kelly, B.; Ng, C.; Robuck, A.; et al. PFAS Exposure Pathways for Humans and Wildlife: A Synthesis of Current Knowledge and Key Gaps in Understanding. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 631–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, J.L.; Nadal, M. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Food and Human Dietary Intake: A Review of the Recent Scientific Literature. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, K.; Mielke, H.; Fromme, H.; Volkel, W.; Menzel, J.; Peiser, M.; Zepp, F.; Willich, S.N.; Weikert, C. Internal Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) and Biological Markers in 101 Healthy 1-year-old Children: Associations Between Levels of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Vaccine Response. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 2131–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balk, F.G.P.; Winkens Putz, K.; Ribbenstedt, A.; Gomis, M.I.; Filipovic, M.; Cousins, I.T. Children’s Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Acids—A Modelling Approach. Environ. Sci.-Process. Impacts 2019, 21, 1875–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fangninou, F.F.; Yu, Z.Y.; Li, W.Z.; Xue, L.; Yin, D.Q. Metastatic Effects of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) on Drosophila melanogaster with Metabolic Reprogramming and Dysrhythmia in a Multigenerational Exposure Scenario. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappazzo, K.M.; Coffman, E.; Hines, E.P. Exposure to Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances and Health Outcomes in Children: A Systematic Review of the Epidemiologic Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlezinger, J.J.; Puckett, H.; Oliver, J.; Nielsen, G.; Heiger-Bernays, W.; Webster, T.F. Perfluorooctanoic Acid Activates Multiple Nuclear Receptor Pathways and Skews Expression of Genes Regulating Cholesterol Homeostasis in Liver of Humanized PPARα Mice Fed an American Diet. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2020, 405, 115204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Beesoon, S.; Zhu, L.; Martin, J.W. Biomonitoring of Perfluoroalkyl Acids in Human Urine and Estimates of Biological Half-life. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 10619–10627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.X.; Luo, X.J.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, C.H.; Feng, Q.J.; Zeng, Y.H.; Mai, B.X. Sex-Specific Bioaccumulation, Maternal Transfer, and Tissue Distribution of Legacy and Emerging Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Snakes (Enhydris chinensis) and the Impact of Pregnancy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 4481–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateia, M.; Van Buren, J.; Barrett, W.; Martin, T.; Back, G.G. Sunrise of PFAS Replacements: A Perspective on Fluorine-Free Foams. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 7986–7996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Sim, W.J.; Lee, E.S.; Lee, J.H.; Oh, J.E. Evaluation of the Fate of Perfluoroalkyl Compounds in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water Res. 2010, 44, 3476–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rand, A.A.; Rooney, J.P.; Butt, C.M.; Meyer, J.N.; Mabury, S.A. Cellular Toxicity Associated with Exposure to Perfluorinated Carboxylates (PFCAs) and Their Metabolic Precursors. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2014, 27, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, N.Y.; Zhu, X.B.; Guo, H.W.; Jiang, J.G.; Wang, X.B.; Shi, W.; Wu, J.C.; Yu, H.X.; Wei, S. Suspect and Nontarget Screening of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Wastewater from a Fluorochemical Manufacturing Park. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 11007–11016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Gong, X.Y.; Wan, R.N.; Gan, Z.W.; Lu, Y.; Sun, H.W. Application of an Immobilized Ionic Liquid for the Passive Sampling of Perfluorinated Substances in Water. J. Cheromatography A 2017, 1515, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendel, S.; Fetter, É.; Staude, C.; Vierke, L.; Biegel-Engler, A. Short-chain Perfluoroalkyl Acids: Environmental Concerns and a Regulatory Strategy under REACH. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2018, 30, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, A.F.; Peng, C.; Ng, J.C. Assessing the Human Health Risks of per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: A Need for Greater Focus on Their Interactions as Mixtures. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 407, 124863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, A.B.; Strynar, M.J.; Libelo, E.L. Polyfluorinated Compounds: Past, Present, and Future. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 7954–7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Song, B.; Xiao, R.; Zeng, G.; Gong, J.; Chen, M.; Xu, P.; Zhang, P.; Shen, M.; Yi, H. Assessing the Human Health Risks of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate by in vivo and in vitro Studies. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Gao, P.; Xiang, P.; Zhang, X.; Cui, X.; Ma, L.Q. Molecular Mechanisms of PFOA-induced Toxicity in Animals and Humans: Implications for Health Risks. Environ. Int. 2017, 99, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.; Bons, J.; Kumar, A.; Kabir, M.H.; Liang, H. Forever Chemicals, Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS), in Lubrication. Lubricants 2024, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, L.G.T. Historical and Current Usage of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): A Literature Review. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2023, 66, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunn, H.; Arnold, G.; Koerner, W.; Rippen, G.; Steinhaeuser, K.G.; Valentin, I. PFAS: Forever Chemicals-persistent, Bioaccumulative and Mobile. Reviewing the Status and the Need for Their Phase out and Remediation of Contaminated Sites. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, M.P.; Riess, J.G. Selected Physicochemical Aspects of Poly- and Perfluoroalkylated Substances Relevant to Performance, Environment and Sustainability—Part One. Chemosphere 2015, 129, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ren, C.; Wang, B.; Sun, H.; Alder, A.C.; Kannan, K. Multimedia Distribution and Transfer of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) Surrounding Two Fluorochemical Manufacturing Facilities in Fuxin, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 8263–8271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evich, M.G.; Davis, M.J.B.; McCord, J.P.; Acrey, B.; Awkerman, J.A.; Knappe, D.R.U.; Lindstrom, A.B.; Speth, T.F.; Tebes-Stevens, C.; Strynar, M.J.; et al. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the Environment. Science 2022, 375, eabg9065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M.J.B.; Evich, M.G.; Goodrow, S.M.; Washington, J.W. Environmental Fate of Cl-PFPECAs: Accumulation of Novel and Legacy Perfluoroalkyl Compounds in Real-World Vegetation and Subsoils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 8994–9004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrick, R.L.; Buckholz, J.; Biro, F.M.; Calafat, A.M.; Ye, X.; Xie, C.; Pinney, S.M. Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Exposure in the Mid-Ohio River Valley, 1991–2012. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 228, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salice, C.J.; Anderson, T.A.; Anderson, R.H.; Olson, A.D. Ecological Risk Assessment of Perfluooroctane Sulfonate to Aquatic Fauna from a Bayou Adjacent to Former Fire Training Areas at a US Air Force Installation. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 2198–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semerád, J.; Hatasová, N.; Grasserová, A.; Černá, T.; Filipová, A.; Hanč, A.; Innemanová, P.; Pivokonský, M.; Cajthaml, T. Screening for 32 Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Including GenX in Sludges from 43 WWTPs Located in the Czech Republic—Evaluation of Potential Accumulation in Vegetables after Application of Biosolids. Chemosphere 2020, 261, 128018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.C.; Andrews, D.Q.; Lindstrom, A.B.; Bruton, T.A.; Schaider, L.A.; Grandjean, P.; Lohmann, R.; Carignan, C.C.; Blum, A.; Balan, S.A.; et al. Detection of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in U.S. Drinking Water Linked to Industrial Sites, Military Fire Training Areas, and Wastewater Treatment Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2016, 3, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, D.; Feng, X.; Yu, X.; Shan, G.; Zhu, L. Insights into the Competitive Mechanisms of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Partition in Liver and Blood. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6192–6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, A.; Aro, R.; Wang, T.; Yeung, L.W.Y. Towards a Comprehensive Analytical Workflow for the Chemical Characterisation of Organofluorine in Consumer Products and Environmental Samples. Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 123, 115423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, I.T.; Vestergren, R.; Wang, Z.; Scheringer, M.; McLachlan, M.S. The Precautionary Principle and Chemicals Management: The Example of Perfluoroalkyl Acids in Groundwater. Environ. Int. 2016, 94, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Arevalo, E.; Strynar, M.; Lindstrom, A.; Richardson, M.; Kearns, B.; Pickett, A.; Smith, C.; Knappe, D.R.U. Legacy and Emerging Perfluoroalkyl Substances Are Important Drinking Water Contaminants in the Cape Fear River Watershed of North Carolina. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2016, 3, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.G.; Jones, K.C.; Sweetman, A.J. A First Global Production, Emission, And Environmental Inventory For Perfluorooctane Sulfonate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cousins, I.T.; Scheringer, M.; Buck, R.C.; Hungerbuhler, K. Global Emission Inventories for C4-C14 Perfluoroalkyl Carboxylic Acid (PFCA) Homologues from 1951 to 2030, Part I: Production and Emissions from Quantifiable Sources. Environ. Int. 2014, 70, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Cousins, I.T.; Scheringer, M.; Hungerbühler, K. Fluorinated Alternatives to Long-chain Perfluoroalkyl Carboxylic Acids (PFCAs), Perfluoroalkane Sulfonic Acids (PFSAs) and Their Potential Precursors. Environ. Int. 2013, 60, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Cousins, I.T.; Scheringer, M.; Hungerbuehler, K. Hazard Assessment of Fluorinated Alternatives to Long-chain Perfluoroalkyl Acids (PFAAs) and Their Precursors: Status Quo, Ongoing Challenges and Possible Solutions. Environ. Int. 2015, 75, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Ruan, T.; Jiang, G. Progress on Analytical Methods and Environmental Behavior of Emerging Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2017, 62, 2724–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Sheng, N.; Wang, J.; Dai, J. The Current Research Status of Several Kinds of Fluorinated Alternatives. Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 2017, 12, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.T.; Zhang, H.X.; Cui, Q.Q.; Sheng, N.; Yeung, L.W.Y.; Sun, Y.; Guo, Y.; Dai, J.Y. Worldwide Distribution of Novel Perfluoroether Carboxylic and Sulfonic Acids in Surface Water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 7621–7629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.W.; Huang, J.; Yang, Y.; Hui, Y.M.; Ge, Y.X.; Larssen, T.; Yu, G.; Deng, S.B.; Wang, B.; Harman, C. First Report of a Chinese PFOS Alternative Overlooked for 30 Years: Its Toxicity, Persistence, and Presence in the Environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 10163–10170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strynar, M.; Dagnino, S.; McMahen, R.; Liang, S.; Lindstrom, A.; Andersen, E.; McMillan, L.; Thurman, M.; Ferrer, I.; Ball, C. Identification of Novel Perfluoroalkyl Ether Carboxylic Acids (PFECAs) and Sulfonic Acids (PFESAs) in Natural Waters Using Accurate Mass Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (TOFMS). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 11622–11630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, S.; McMahen, R.; Stoeckel, J.A.; Chislock, M.; Lindstrom, A.; Strynar, M. Novel Polyfluorinated Compounds Identified Using High Resolution Mass Spectrometry Downstream of Manufacturing Facilities near Decatur, Alabama. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 1544–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebbink, W.A.; van Asseldonk, L.; van Leeuwen, S.P.J. Presence of Emerging Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in River and Drinking Water near a Fluorochemical Production Plant in the Netherlands. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 11057–11065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prevedouros, K.; Cousins, I.T.; Buck, R.C.; Korzeniowski, S.H. Sources, Fate and Transport of Perfluorocarboxylates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameduri, B.; Hori, H. Recycling and the End of Life Assessment of Fluoropolymers: Recent Developments, Challenges and Future Trends. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 4208–4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandsma, S.H.; Koekkoek, J.C.; van Velzen, M.J.M.; de Boer, J. The PFOA Substitute GenX Detected in the Environment near a Fluoropolymer Manufacturing Plant in the Netherlands. Chemosphere 2019, 220, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Cai, Y.; Shi, Y. Atmospheric Emission of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from a Fluoropolymer Manufacturing Facility: Focus on Emerging PFAS and the Potential Contribution of Condensable PFAS on their Atmospheric Partitioning. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 9709–9720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Vestergren, R.; Shi, Y.; Huang, J.; Cai, Y. Emissions, Transport, and Fate of Emerging Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances from One of the Major Fluoropolymer Manufacturing Facilities in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 9694–9703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmann, R.; Cousins, I.T.; DeWitt, J.C.; Gluge, J.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lindstrom, A.B.; Miller, M.F.; Ng, C.A.; Patton, S.; et al. Are Fluoropolymers Really of Low Concern for Human and Environmental Health and Separate from Other PFAS? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 12820–12828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, D.A.; Mabury, S.A.; Martin, J.W.; Muir, D.C.G. Thermolysis of Fluoropolymers as a Potential Source of Halogenated Organic Acids in the Environment. Nature 2001, 412, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Chen, L.; Shao, L.; Zhang, H.; Lu, F. Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) Landfill: A Source of Microplastics? -Evidence of Microplastics in Landfill Leachate. Water Res. 2019, 159, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, Y.; Yang, P.; Huang, T.; Green, S.; Luong, J. Defluorination and Derivatization of Fluoropolymers for Determination of Total Organic Fluorine in Polyolefin Resins by Gas Chromatography. Anal. Methods 2025, 17, 3746–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, A.L.; Jobst, K.J.; Mabury, S.A.; Reiner, E.J. Using Mass Defect Plots as a Discovery Tool to Identify Novel Fluoropolymer Thermal Decomposition Products. J. Mass Spectrom. 2014, 49, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skedung, L.; Savvidou, E.; Schellenberger, S.; Reimann, A.; Cousins, I.T.; Benskin, J.P. Identification and Quantification of Fluorinated Polymers in Consumer Products by Combustion Ion Chromatography and Pyrolysis-gas Chromatography-mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2024, 26, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivy, D.J.; Rigby, M.; Baasandorj, M.; Burkholder, J.B.; Prinn, R.G. Global Emission Estimates and Radiative Impact of C4F10, C5F12, C6F14, C7F16 and C8F18. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 7635–7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, G.W.; Mair, D.C.; Lange, C.C.; Harrington, L.M.; Church, T.R.; Goldberg, C.L.; Herron, R.M.; Hanna, H.; Nobiletti, J.B.; Rios, J.A.; et al. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in American Red Cross Adult Blood Donors, 2000–2015. Environ. Res. 2017, 157, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Shi, Q.; Gan, J. Uptake, Accumulation and Metabolism of PFASs in Plants and Health Perspectives: A Critical Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 51, 2745–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Song, X.; Jones, K.; Sweetman, A.J.; Johnson, A.C.; Zhang, M.; Lu, X.; Su, C. Multiple Crop Bioaccumulation and Human Exposure of Perfluoroalkyl Substances around a Mega Fluorochemical Industrial Park, China: Implication for Planting Optimization and Food Safety. Environ. Int. 2019, 127, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.C.; Ikonomou, M.G.; Blair, J.D.; Surridge, B.; Hoover, D.; Grace, R.; Gobas, F.A.P.C. Perfluoroalkyl Contaminants in an Arctic Marine Food Web: Trophic Magnification and Wildlife Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 4037–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomy, G.T.; Budakowski, W.; Halldorson, T.; Helm, P.A.; Stern, G.A.; Friesen, K.; Pepper, K.; Tittlemier, S.A.; Fisk, A.T. Fluorinated Organic Compounds in an Eastern Arctic Marine Food Web. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 6475–6481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Simon, K.L.; Best, D.A.; Bowerman, W.; Venier, M. Novel and Legacy Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Bald Eagle Eggs from the Great Lakes Region. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 113811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dassuncao, C.; Hu, X.C.; Nielsen, F.; Weihe, P.; Grandjean, P.; Sunderland, E.M. Shifting Global Exposures to Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) Evident in Longitudinal Birth Cohorts from a Seafood-Consuming Population. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 3738–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tartu, S.; Bourgeon, S.; Aars, J.; Andersen, M.; Lone, K.; Jenssen, B.M.; Polder, A.; Thiemann, G.W.; Torget, V.; Welker, J.M.; et al. Diet and Metabolic State are the Main Factors Determining Concentrations of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Female Polar Bears from Svalbard. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 229, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cousins, I.T.; Ng, C.A.; Wang, Z.; Scheringer, M. Why is High Persistence alone a Major Cause of Concern? Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2019, 21, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdo, C.J.; Ellis, D.A.; Webster, E.; Butler, J.; Christensen, R.D.; Reid, L.K. Aerosol Enrichment of the Surfactant PFO and Mediation of the Water-Air Transport of Gaseous PFOA. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 3969–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, L.; Shoeib, M.; Harner, T.; Lee, S.C.; Guo, R.; Reiner, E.J. Wastewater Treatment Plant and Landfills as Sources of Polyfluoroalkyl Compounds to the Atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 8098–8105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joerss, H.; Xie, Z.; Wagner, C.C.; von Appen, W.J.; Sunderland, E.M.; Ebinghaus, R. Transport of Legacy Perfluoroalkyl Substances and the Replacement Compound HFPO-DA through the Atlantic Gateway to the Arctic Ocean-Is the Arctic a Sink or a Source? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 9958–9967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calore, F.; Badetti, E.; Bonetto, A.; Pozzobon, A.; Marcomini, A. Non-conventional Sorption Mmaterials for the Removal of Legacy and Emerging PFAS from Water: A Review. Emerg. Contam. 2024, 10, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Fu, K.; Fang, Z.; Luo, J. Enhanced Selective Removal of PFAS at Trace Level using Quaternized Cellulose-functionalized Polymer Resin: Performance and Mechanism. Water Res. 2025, 272, 122937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poothong, S.; Padilla-Sánchez, J.A.; Papadopoulou, E.; Giovanoulis, G.; Thomsen, C.; Haug, L.S. Hand Wipes: A Useful Tool for Assessing Human Exposure to Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) through Hand-to-Mouth and Dermal Contacts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1985–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Choi, K.; Lee, H.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Park, N.-Y.; Kim, S.; Kho, Y. Elevated Levels of Short Carbon-chain PFCAs in Breast Milk among Korean Women: Current Status and Potential Challenges. Environ. Res. 2016, 148, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Pan, Y.; Sheng, N.; Su, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Dai, J. Novel Perfluoroalkyl Ether Carboxylic Acids (PFECAs) and Sulfonic Acids (PFESAs): Occurrence and Association with Serum Biochemical Parameters in Residents Living Near a Fluorochemical Plant in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 13389–13398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, N.; Pan, Y.; Guo, Y.; Sun, Y.; Dai, J. Hepatotoxic Effects of Hexafluoropropylene Oxide Trimer Acid (HFPO-TA), A Novel Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) Alternative, on Mice. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 8005–8015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, J.M.; Lambright, C.S.; Evans, N.; McCord, J.; Strynar, M.J.; Hill, D.; Medlock-Kakaley, E.; Wilson, V.S.; Gray, L.E. Hexafluoropropylene Oxide-dimer Acid (HFPO-DA or GenX) Alters Maternal and Fetal Glucose and Lipid Metabolism and Produces Neonatal Mortality, Low Birthweight, and Hepatomegaly in the Sprague-Dawley Rat. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonough, C.A.; Ward, C.; Hu, Q.; Vance, S.; Higgins, C.P.; DeWitt, J.C. Immunotoxicity of an Electrochemically Fluorinated Aqueous Film-Forming Foam. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 178, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Xu, L.L.; Zhong, M.T.; Chen, Y.K.; Lai, M.Q.; Wang, Q.; Xie, X.L. Gestational GenX and PFOA Exposures Induce Hepatotoxicity, Metabolic Pathway, and Microbiome Shifts in Weanling Mice. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 168059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Sun, Y.; Duan, J.; Zhang, T.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Zhong, W.; Zhu, L. Impacts of Gestational F-53B Exposure on Fetal Neurodevelopment: Insights from Placental and Thyroid Hormone Disruption. Environ. Health 2025, 3, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; An, Z.; Lv, J.; Xiao, F.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Duan, W.; Guo, M.; Zeng, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Tissue Accumulation and Hepatotoxicity of 8:2 Chlorinated Polyfluoroalkyl Ether Sulfonate: A Multi-omics Analysis Deciphering Hepatic Amino Acid Metabolic Dysregulation in Mice. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 483, 136668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Wan, B.; Yu, B.; Fan, Y.; Chen, D.; Guo, L.H. Chlorinated Polyfluoroalkylether Sulfonic Acids Exhibit Stronger Estrogenic Effects than Perfluorooctane Sulfonate by Activating Nuclear Estrogen Receptor Pathways. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3455–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Xu, B.; Magnuson, J.T.; Xu, E.G.; Wu, M.; Zheng, C. Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances Induce Immunotoxicity via the TLR Pathway in Zebrafish: Links to Carbon Chain Length. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 6139–6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, T.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, W. Critical Evaluation and Meta-Analysis of Ecotoxicological Data on Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Freshwater Species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 17555–17566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issemann, I.; Green, S. Activation of a Member of the Steroid Hormone Receptor Superfamily by Peroxisome Proliferators. Nature 1990, 347, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, D.W.; Parkinson, L.V.; Boucher, J.M.; Muncke, J.; Geueke, B. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Food Packaging: Migration, Toxicity, and Management Strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 5670–5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, I.T.; DeWitt, J.C.; Glüge, J.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lohmann, R.; Ng, C.A.; Scheringer, M.; Wang, Z.Y. The High Persistence of PFAS is Sufficient for Their Management as a Chemical Class. Environ. Sci.-Process. Impacts 2020, 22, 2307–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.C.; Lin, Z.M. Probabilistic Human Health Risk Assessment of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) by Integrating in vitro, in vivo Toxicity, and Human Epidemiological Studies using a Bayesian-based Dose-response Assessment Coupled with Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling Approach. Environ. Int. 2020, 137, 105581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nisio, A.; Pannella, M.; Vogiatzis, S.; Sut, S.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Santa Rocca, M.; Antonini, A.; Porzionato, A.; De Caro, R.; Bortolozzi, M.; et al. Impairment of Human Dopaminergic Neurons at Different Developmental Stages by Perfluoro-octanoic Acid (PFOA) and Differential Human Brain Areas Accumulation of Perfluoroalkyl Chemicals. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foguth, R.M.; Flynn, R.W.; de Perre, C.; Iacchetta, M.; Lee, L.S.; Sepúlveda, M.S.; Cannon, J.R. Developmental Exposure to Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) Selectively Decreases Brain Dopamine Levels in Northern Leopard Frogs. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2019, 377, 114623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.Y.; Lin, L.Y.; Chiang, C.K.; Wang, W.J.; Su, Y.N.; Hung, K.Y.; Chen, P.C. Investigation of the Associations Between Low-Dose Serum Perfluorinated Chemicals and Liver Enzymes in US Adults. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 1354–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, A.M.; Yolton, K.; Webster, G.M.; Sjödin, A.; Calafat, A.M.; Braun, J.M.; Dietrich, K.N.; Lanphear, B.P.; Chen, A. Prenatal Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether and Perfluoroalkyl Substance Exposures and Executive Function in School-age Children. Environ. Res. 2016, 147, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisonet, M.; Terrell Metrecia, L.; McGeehin Michael, A.; Christensen Krista, Y.; Holmes, A.; Calafat Antonia, M.; Marcus, M. Maternal Concentrations of Polyfluoroalkyl Compounds during Pregnancy and Fetal and Postnatal Growth in British Girls. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 1432–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisari, M.; Eiberg, H.; Long, M.; Bonefeld-Jorgensen, E.C. Polymorphisms in Phase I and Phase II Genes and Breast Cancer Risk and Relations to Persistent Organic Pollutant Exposure: A Case-control Study in Inuit Women. Environ. Health 2014, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Yang, R.; Yu, Y.; Yang, C.; He, L.; Wang, Z.; Jin, H.; Liu, D. Exposure Characteristics and Health Risk Assessment of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Their Typical Isomers in Human Serum. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2024, 44, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjork, J.A.; Wallace, K.B. Structure-Activity Relationships and Human Relevance for Perfluoroalkyl Acid–Induced Transcriptional Activation of Peroxisome Proliferation in Liver Cell Cultures. Toxicol. Sci. 2009, 111, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjork, J.A.; Butenhoff, J.L.; Wallace, K.B. Multiplicity of Nuclear Receptor Activation by PFOA and PFOS in Primary Human and Rodent Hepatocytes. Toxicology 2011, 288, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, D.C.; Moore, T.; Abbott, B.D.; Rosen, M.B.; Das, K.P.; Zehr, R.D.; Lindstrom, A.B.; Strynar, M.J.; Lau, C. Comparative Hepatic Effects of Perfluorooctanoic Acid and WY 14,643 in PPAR-alpha Knockout and Wild-type Mice. Toxicol. Pathol. 2008, 36, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, C.J.; Schmid, J.E.; Lau, C.; Abbott, B.D. Activation of Mouse and Human Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor-alpha (PPARα) by Perfluoroalkyl Acids (PFAAs): Further Investigation of C4-C12 Compounds. Reprod. Toxicol. 2012, 33, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.T.; Eken, Y.; Wilson, A.K. Binding of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances to the Human Pregnane X Receptor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 15986–15995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.B.; Abbott, B.D.; Wolf, D.C.; Corton, J.C.; Wood, C.R.; Schmid, J.E.; Das, K.P.; Zehr, R.D.; Blair, E.T.; Lau, C. Gene Profiling in the Livers of Wild-type and PPARalpha-null Mice Exposed to Perfluorooctanoic Acid. Toxicol. Pathol. 2008, 36, 592–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Klaassen, C.D. Critical Role of PPAR-alpha in Perfluorooctanoic Acid- and Perfluorodecanoic Acid-induced Downregulation of Oatp Uptake Transporters in Mouse Livers. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 106, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, K.; Li, W.; Chai, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chu, B.; Li, N.; Yan, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y. Varied Thyroid Disrupting Effects of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Its Novel Alternatives Hexafluoropropylene-oxide-dimer-acid (GenX) and Ammonium 4,8-dioxa-3H-perfluorononanoate (ADONA) in vitro. Environ. Int. 2021, 156, 106745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.B.; Lee, J.S.; Ren, H.; Vallanat, B.; Jie, L.; Waalkes, M.P.; Abbott, B.D.; Lau, C.; Corton, J.C. Toxicogenomic Dissection of the Perfluorooctanoic Acid Transcript Profile in Mouse Liver: Evidence for the Involvement of Nuclear Receptors PPAR Alpha and CAR. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 103, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, M.B.; Schmid, J.R.; Corton, J.C.; Zehr, R.D.; Lau, C. Gene Expression Profiling in Wild-Type and PPARα-Null Mice Exposed to Perfluorooctane Sulfonate Reveals PPARα-Independent Effects. PPAR Res. 2010, 2010, 794739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, M.B.; Das, K.P.; Rooney, J.; Abbott, B.; Lau, C.; Corton, J.C. PPARα-independent Transcriptional Targets of Perfluoroalkyl Acids Revealed by Transcript Profiling. Toxicology 2017, 387, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.; Vallanat, B.; Nelson, D.M.; Yeung, L.; Guruge, K.S.; Lam, P.; Lehman-Mck Ee Man, L.D.; Corton, J.C. Evidence for the Involvement of Xenobiotic-responsive Nuclear Receptors in Transcriptional Effects upon Perfluoroalkyl Acid Exposure in Diverse Species. Reprod. Toxicol. 2009, 27, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ren, X.M.; Wan, B.; Guo, L.H. Structure-dependent Binding and Activation of Perfluorinated Compounds on Human Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor γ. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014, 279, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.J.; Pyo, M.C.; Rhee, K.H.; Lim, J.M.; Yang, S.A.; Yoo, M.K.; Lee, K.W. Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Hexafluoropropylene Oxide-dimer Acid (GenX): Hepatic Stress and Bile Acid Metabolism with Different Pathways. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 259, 115001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shimpi, P.; Armstrong, L.; Salter, D.; Slitt, A.L. PFOS Induces Adipogenesis and Glucose Uptake in Association with Activation of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2016, 290, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.-c.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.-y.; Wang, Y.-j.; Xia, W.; Lin, Y.; Wei, J.; Xu, S.-q. Inflammation-like Glial Response in Rat Brain Induced by Prenatal PFOS Exposure. NeuroToxicology 2011, 32, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, A.; Sai, K.; Umemura, T.; Hasegawa, R.; Kurokawa, Y. Short-term Exposure to the Peroxisome Proliferators, Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorodecanoic Acid, Causes Significant Increase of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine in Liver DNA of Rats. Cancer Lett. 1991, 57, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Liu, W.; Song, J.; Yu, H.; Jin, Y.; Oami, K.; Sato, I.; Saito, N.; Tsuda, S. A Comparative Study on Oxidative Damage and Distributions of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) in Mice at Different Postnatal Developmental Stages. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2009, 34, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, K.T.; Raaschou-Nielsen, O.; Sørensen, M.; Roursgaard, M.; Loft, S.; Møller, P. Genotoxic Potential of the Perfluorinated Chemicals PFOA, PFOS, PFBS, PFNA and PFHxA in Human HepG2 Cells. Mutat. Res./Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2010, 700, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corton, J.C.; Cunningham, M.L.; Hummer, B.T.; Lau, C.; Meek, B.; Peters, J.M.; Popp, J.A.; Rhomberg, L.; Seed, J.; Klaunig, J.E. Mode of Action Framework Analysis for Receptor-mediated Toxicity: The Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor Alpha (PPARα) as a Case Study. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2014, 44, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Jones, P.D.; Upham, B.L.; Trosko, J.E.; Lau, C.; Giesy, J.P. Inhibition of Gap Junctional Intercellular Communication by Perfluorinated Compounds in Rat Liver and Dolphin Kidney Epithelial Cell Lines In Vitro and Sprague-Dawley Rats In Vivo. Toxicol. Sci. 2002, 68, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upham, B.L.; Deocampo, N.D.; Wurl, B.; Trosko, J.E. Inhibition of Gap Junctional Intercellular Communication by Perfluorinated Fatty Acids is Dependent on the Chain Length of the Fluorinated Tail. Int. J. Cancer 1998, 78, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham Brad, L.; Park, J.-S.; Babica, P.; Sovadinova, I.; Rummel Alisa, M.; Trosko James, E.; Hirose, A.; Hasegawa, R.; Kanno, J.; Sai, K. Structure-Activity–Dependent Regulation of Cell Communication by Perfluorinated Fatty Acids Using In Vivo and In Vitro Model Systems. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, H.-T.; Mruk, D.D.; Wong, C.K.C.; Cheng, C.Y. Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) Perturbs Male Rat Sertoli Cell Blood-Testis Barrier Function by Affecting F-Actin Organization via p-FAK-Tyr407: An In Vitro Study. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]