Abstract

Carbon dots (CDs) have recently emerged as a novel class of eco-friendly and multifunctional corrosion inhibitors owing to their nanoscale dimensions, tunable surface functionalities, and sustainable synthesis pathways. This review summarizes the latest progress in CD-based inhibitors, focusing on synthesis methods, applications, and inhibition mechanisms. Various strategies—including hydrothermal/solvothermal treatment, microwave irradiation, pyrolysis, electrochemical synthesis, and chemical oxidation—have been employed to obtain CDs with tailored size, heteroatom doping, and surface groups, thereby enhancing their inhibition efficiency. CDs have demonstrated remarkable applicability across diverse corrosive environments, including acidic, neutral chloride, CO2-saturated, microbiologically influenced, and alkaline systems, often achieving inhibition efficiencies exceeding 90%. Mechanistically, their performance arises from strong adsorption and compact film formation, heteroatom-induced electronic modulation, suppression of anodic and cathodic reactions, and synergistic effects of particle size and structural configuration. Compared with conventional inhibitors, CDs offer higher efficiency, environmental compatibility, and multifunctionality. Despite significant progress, challenges remain regarding precise structural control, scalability of synthesis, and deeper mechanistic understanding. The effectiveness of CDs inhibitors is highly dependent on factors such as pH, temperature, inhibitor concentration, and exposure time, which should be tailored for specific applications to maximize performance. Future research should focus on integrating sustainable synthesis with rational heteroatom engineering and advanced characterization to achieve long-term, cost-effective, and environmentally benign corrosion protection solutions. Compared to earlier reviews, this review discusses the emerging trends in the field of CDs as corrosion inhibitors.

1. Introduction

Corrosion, as a pervasive global issue, severely threatens the durability and service life of metal structures in sectors ranging from infrastructure and transportation to emerging fields such as aerospace, renewable energy, and electronic devices [1,2]. According to the National Association of Corrosion Engineers, the worldwide cost of corrosion exceeds USD 2.5 trillion annually, reflecting both economic and environmental impacts, including intensified greenhouse gas emissions [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. To address this challenge, various strategies have been developed, including corrosion inhibitors [9,10,11], self-assembled films [12,13], surface spraying or passivation [14,15,16], and electrochemical protection [17,18]. Among these, corrosion inhibitors are particularly attractive due to their high efficiency, low cost, and compatibility with diverse metals, effectively reducing corrosion rates with minimal dosage [9,10,19].

Traditional inhibitors are generally classified as inorganic or organic compounds [9,20,21]. While inorganic inhibitors such as phosphate, nitrite, and chromate exhibit effectiveness, their toxicity, instability, and environmental hazards limit practical application [22,23,24]. Organic inhibitors, typically containing heteroatoms (N, O, S) with lone-pair electrons, provide better biodegradability and adsorb strongly onto metal surfaces [25,26,27]. However, challenges remain, including poor solubility [28], complicated preparation [29,30,31], and the use of hazardous solvents [31,32]. Thus, there is an urgent demand for novel inhibitors combining high solubility, environmental friendliness, and excellent inhibition efficiency.

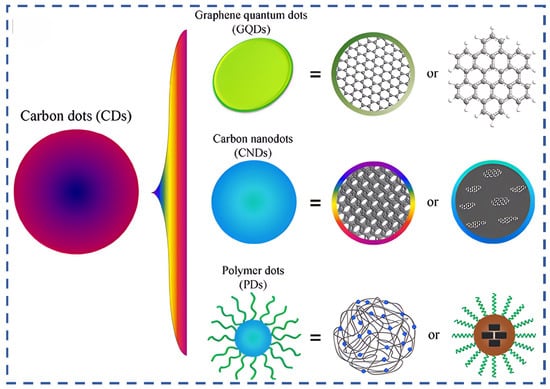

CDs, a new class of zero-dimensional fluorescent nanomaterials, offer unique properties such as nanoscale size, high water solubility, tunable surface functionality, large specific surface area, and low toxicity [33,34,35,36,37,38]. These advantages have enabled wide applications in biomedicine, optoelectronics, catalysis, chemical sensing, lubrication, and civil engineering [39,40,41,42,43,44]. Structurally, CDs can be categorized into graphene quantum dots (GQDs), carbon nanodots (CNDs), and polymer dots (PDs), each with distinct morphologies and electronic properties (Figure 1) [45]. Importantly, CDs have recently emerged as promising, eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors for various metals across environments such as acidic, chloride-rich, CO2-saturated, microbiologically influenced, and alkaline media [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53].

Figure 1.

The classification of CDs [54].

Despite this progress, existing reviews on CD inhibitors remain limited. Elsadek et al. mainly discussed GQDs as additives in protective coatings [55], while Quraishi et al. highlighted the superiority of CDs over conventional nanomaterials but provided only shallow analysis due to limited literature coverage [56]. Berdimurodov et al. systematically examined CDs under harsh conditions, yet offered insufficient mechanistic insights [51]. More recently, Wang et al. focused on CDs as smart additives in coatings rather than as standalone inhibitors [57]. Therefore, gaps remain in the systematic review of synthetic strategies, application scenarios, and inhibition mechanisms of CDs.

To fill these gaps, this review provides a comprehensive overview of the recent progress in CDs as corrosion inhibitors, with emphasis on their synthesis strategies, application scenarios, and inhibition mechanisms. To ensure a comprehensive review, we performed a literature search using the keywords “CDs”, “carbon dot*”, “graphene quantum dot*”, “GQDs”, “carbon nanodot*”, “polymer dot*”, “PDs” and “Corrosion inhibitor*” for studies published between 2015 and 2025. High-impact and highly cited studies were included, and the search was conducted using the Web of Science database. Section 2 highlights the synthesis methods—including hydrothermal/solvothermal, microwave-assisted, pyrolysis, electrochemical, and chemical oxidation routes—and demonstrates how these approaches regulate particle size, heteroatom doping, and surface functionalization to optimize inhibition performance in diverse environments such as acidic, neutral, CO2-saturated, microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC), and alkaline systems. Section 3 elucidates the underlying mechanisms, emphasizing adsorption-driven film formation, heteroatom-enhanced coordination, electrochemical modulation of anodic and cathodic reactions, and the synergistic effects of particle size, structure, and sustainable synthesis pathways. Collectively, these discussions underline the versatility, efficiency, and eco-friendly potential of CDs, while pointing toward future directions in scalable, low-energy synthesis and rational structural design for next-generation multifunctional inhibitors.

2. Synthesis and Applications of CDs as Corrosion Inhibitors

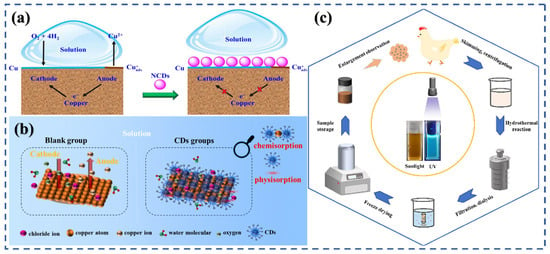

The structural diversity of CDs arises from differences in raw materials and synthesis strategies, which in turn dictate their corrosion inhibition performance. Generally, CDs are prepared via top-down or bottom-up approaches. The former breaks down bulk carbon materials such as graphene or carbon nanotubes into nanoscale CDs, while the latter relies on the polymerization and carbonization of small molecules or polymers. Common techniques include hydrothermal/solvothermal treatment, microwave irradiation, pyrolysis, electrochemical synthesis, and chemical oxidation. Owing to these versatile methods, CDs with diverse surface functionalities have been obtained, enabling tailored inhibition properties. Since the first report in 2015 confirming their efficiency in acidic media, CDs-based inhibitors have been explored in chloride solutions, CO2-saturated solutions, MIC, and alkaline environments, highlighting their broad applicability. This section will specifically focus on the synthesis and applications of CDs as corrosion inhibitors.

2.1. Acid Solutions

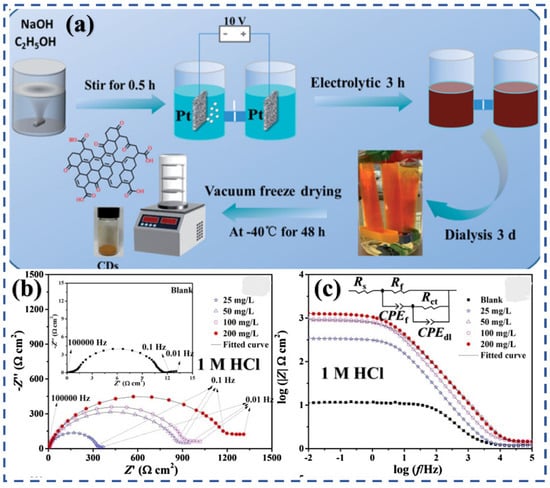

Acid-induced corrosion is widely encountered in descaling, pickling, and oil well acidification, where aggressive H+ ions cause severe dissolution of steel and non-ferrous alloys [50,58,59]. The first application of carbon-based nanomaterials in this field was reported in 2015, when graphene quantum dots (GQDs) achieved an inhibition efficiency (η) of 71.7% at 300 mg/L for carbon steel in 1 M HCl solution [60]. Shortly after, Zhao’s group synthesized N-doped CDs (N-CDs) via a solvothermal method using aminosalicylic acid (200 °C, 18 h), yielding ~3 nm particles enriched with O and N functional groups, which significantly improved performance (η = 90.9% at only 10 mg/L) [46]. E et al. synthesized N-CDs with varying nitrogen contents via a hydrothermal method and investigated their corrosion inhibition performance on Q235 carbon steel in HCl solution (Figure 2). The results revealed a nonlinear relationship between the level of nitrogen doping and the η values. Their results indicated that inhibition performance reached a maximum efficiency of 95.27% at a nitrogen content of 18.52% [61]. Since then, hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis has become the most common strategy, as it allows controlled heteroatom doping and particle size regulation. Figure 2a illustrates a typical process of hydrothermal synthesis. Using precursors such as imidazole, n-butylamine, ethylenediamine, and methionine, numerous N- and N, S-CDs have been reported, often achieving η values close to 100% for carbon steel [62,63,64,65,66,67]. Similar results have been observed for copper and aluminum, demonstrating the versatility of this approach [63,68,69,70,71]. In these acidic environments, the adsorption of CDs typically follows the Langmuir adsorption isotherm, as seen in studies where CDs showed high corrosion inhibition efficiency [65].

Figure 2.

The preparation and performance evaluation of N-doped CDs (N-CDs) for corrosion inhibition in acidic media: (a) Synthesis process of N-CDs via hydrothermal method [61]; (b) EIS analysis of N-CDs in 1 M HCl; (c) Effect of N-CDs on corrosion inhibition efficiency (η) at varying concentrations in HCl solution [63].

To enhance sustainability, biomass-derived CDs obtained from litchi leaves [65], grapefruit peels [72], mango pulp [73], melon seed shells [74], and chicken protein via hydrothermal treatment exhibited η values above 95%, confirming their potential as green inhibitors [66]. Beyond hydrothermal methods, pyrolysis synthesis has been employed to decouple the effects of particle size and nitrogen configuration (pyrrolic-N, amino-N, quaternary-N), providing insight into structure–performance relationships [75,76]. Microwave-assisted synthesis offers ultrafast preparation (minutes) with η values exceeding 90% [77], although reproducibility and precise surface control remain challenges. Electrochemical synthesis, though environmentally friendly, generally yields oxygen-rich GQDs with lower inhibition performance compared to hydrothermal CDs [68,78]. Importantly, chemical oxidation and in situ approaches have recently gained attention. For instance, glucose and concentrated H2SO4 enabled the rapid preparation of CD-containing acidic inhibitors in just 3 min at room temperature, reaching high inhibition efficiencies without tedious post-treatment [67].

In acidic solutions such as 1 M HCl, surface morphology is typically examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) [79]. SEM is used to observe morphology changes after corrosion. AFM evaluates surface roughness. XPS provides the chemical states of surface elements. Without CDs, SEM reveals severe corrosion with clear pits and cracks. After adding CDs, the surface becomes smoother and the number of corrosion pits decreases markedly [80]. SEM-EDS analysis further shows that, without CDs, the surface composition is dominated by Fe (37.25%) and Cl (8.71%), indicating significant chloride attack. However, with the addition of CDs, the Fe content increases to 76.47%, while the Cl content decreases to 0.14%, showing that CDs effectively inhibit chloride-induced corrosion [80]. AFM results show that the surface roughness increases significantly without CDs (Ra = 230 nm), while the roughness is greatly reduced after their addition (Ra = 40.1 nm), confirming the inhibiting effect of CDs [80]. XPS analysis further shows that the amount of surface oxides decreases after adding CDs. The CDs help limit the attack of acidic corrosive media on the metal surface [80].

Quantum chemical calculations and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are commonly used to reveal the corrosion mechanism of CDs in acid solutions [81]. Quantum chemical calculations often rely on density functional theory (DFT) to obtain the HOMO–LUMO band gap of the inhibitor molecules, while MD simulations are used to calculate their adsorption energy (Ebinding) on the metal surface. DFT results show that CDs have a small HOMO–LUMO gap. This indicates strong interactions with the metal surface through electron donation and back-donation, which enhances their inhibition performance [82]. MD simulations further show that CDs exhibit high adsorption energies in 1 M HCl, suggesting the formation of stable adsorption structures that effectively reduce proton-induced corrosion [80]. Anton et al. have reported no significant correlation between the simulated basic electronic parameters of inhibitor molecules, such as ionization potential, electron affinity, HOMO–LUMO gap, and dipole moment, and the experimental inhibition efficiency (IE). The main reason is that the MEPTIC approach is not suitable for molecules with fundamentally different structures [82]. Molecular-Electronic Properties To Inhibition-efficiency Correlation (MEPTIC) relies on two assumptions. The first is that basic electronic parameters are meaningful reactivity indicators that can predict the adsorption tendency of inhibitors. The second is that stronger binding between inhibitor molecules and the metal surface leads to better inhibition performance. This assumption is based on a simplified idea that IE is equivalent to the surface coverage (θ). Therefore, this approach should be used with caution [82].

Overall, the synthesis route dictates the functional chemistry of CDs and, consequently, their efficiency in acid media. Hydrothermal methods ensure tunable surface doping and high reproducibility, biomass-derived pathways enhance sustainability, while emerging in situ strategies point toward scalable, energy-efficient solutions for industrial pickling and acidizing applications.

2.2. Alkaline Environments

Chloride-contaminated alkaline environments, such as the pore solutions of reinforced concrete, present a unique corrosion scenario where the passive film on steel is destabilized by Cl− ions despite the high alkalinity [53]. Protecting rebar under these conditions requires inhibitors that can adsorb strongly and remain stable in highly alkaline media.

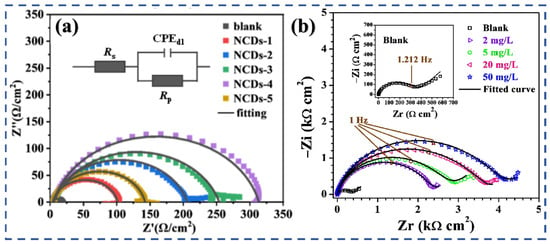

Hydrothermal synthesis has been widely applied to prepare biomass-derived CDs with promising results. For example, litchi-leaf, melon seed shell, and chicken protein precursors yielded N- or N, S-doped CDs with η values exceeding 90% in simulated pore solutions [65,66,74]. The hydrothermal route allows the incorporation of heteroatoms and abundant oxygen-containing functional groups, which enhance electrostatic and coordination interactions with steel surfaces, forming dense protective films that block both chloride ingress and electrochemical activity (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

EIS analysis of biomass-derived CDs in alkaline chloride environments: (a) Nyquist plots of N-CDs at varying concentrations [74]; (b) EIS results for N-CDs [70].

In addition to hydrothermal methods, chemical oxidation approaches have been employed to produce O- and N-rich CDs, which exhibit strong adsorption in alkaline media. The presence of surface –COOH and –OH groups, introduced during oxidation, improves hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions in high-pH environments, thereby reinforcing the stability of inhibitor films (Figure 3b) [70].

A particularly innovative approach is the room-temperature Schiff base reaction, where p-benzoquinone and o-phenylenediamine react under mild conditions to produce N-CDs with Schiff base structures [83,84,85,86]. These CDs reached η values close to 99% at 400 mg/L in alkaline chloride media, while avoiding the high energy consumption typical of hydrothermal or pyrolytic synthesis. This method exemplifies the potential of in situ or near-room-temperature synthesis, which reduces processing complexity and energy costs while yielding CDs with excellent adsorption and stability in concrete pore solutions.

Mechanistically, the effectiveness of CDs in alkaline systems is attributed to their ability to form strong chemisorption bonds (via amino and imine groups) and compact films that resist chloride penetration. Nitrogen functionalities in particular enhance bonding to Fe atoms, while oxygen-rich groups provide additional hydrogen bonding, creating multilayered protection. Thus, synthesis methods that maximize heteroatom incorporation and functional group density—especially hydrothermal biomass strategies and Schiff base chemistry—are key to developing sustainable, scalable inhibitors for reinforced concrete applications.

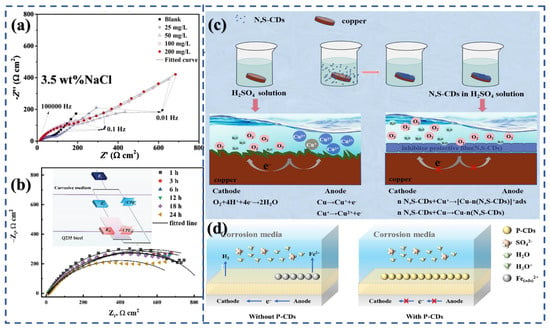

2.3. Neutral Solutions

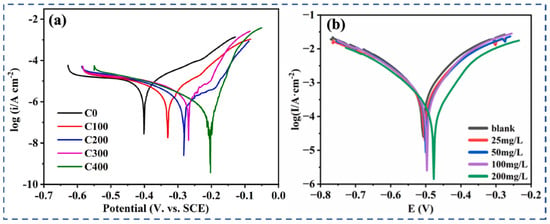

Neutral solutions, mainly chloride-induced corrosion, present a major challenge in marine and atmospheric environments due to the high aggressiveness of Cl− ions, which initiate localized pitting and accelerate metal degradation [51,69]. Early efforts by Zhao’s group employed a two-step hydrothermal method combined with ionic liquid modification to prepare imidazole-functionalized CDs (IM-CDs), which achieved an η value of 85.7% for carbon steel in 3.5 wt% NaCl at 200 mg/L (Figure 4a) [87]. Although effective, the relatively complex preparation and high cost limited large-scale applicability. To overcome these drawbacks, Ye’s group developed low-cost N-CDs via a one-step hydrothermal method, raising inhibition efficiency to 88.96% under the same conditions (Figure 4b) [47].

Figure 4.

EIS analysis and mechanism of CDs in neutral chloride solutions: (a) Nyquist plots of N-CDs in 3.5 wt% NaCl [88]; (b) EIS analysis of corrosion inhibition performance for Q235 steel in NaCl solution over time [47]; (c) Schematic illustration of N,S-CDs as corrosion inhibitors for copper in H2SO4 solution [89]; (d) Mechanism of corrosion inhibition with and without P-CDs in chloride media [90].

Subsequent studies emphasized the role of heteroatom doping. Zhang’s team increased the nitrogen content of hydrothermally synthesized CDs up to 23.95%, achieving η = 96.1% for copper in NaCl solution [91]. Similarly, Yang prepared N, S-CDs by introducing thiourea as a precursor, and these reached 96.5% for Q235 steel (Figure 4c) [89]. Comparative analyses suggest that nitrogen doping provides the primary contribution to inhibition, while sulfur acts as a secondary enhancer, offering only marginal gains relative to N-CDs but adding synthetic complexity [92].

Beyond hydrothermal methods, microwave synthesis has been applied to produce N-CDs within minutes [77]. Although the rapid preparation is attractive, reproducibility and control of surface chemistry remain challenges. Polymer- and biomass-derived CDs synthesized hydrothermally have further extended the scope of applications, demonstrating both corrosion inhibition and multifunctionality. For example, Wang’s group reported dual-functional CDs with η = 94.01% in 3.5 wt% NaCl, which also acted as fluorescent probes for Cr (VI) detection with a detection limit of 24 nM (Figure 4d) [90].

In neutral solutions, the adsorption of CDs typically follows the Langmuir adsorption isotherm, demonstrating a high efficiency of corrosion inhibition in NaCl environments. The adsorption process involves both physical and chemical interactions between CDs and the metal surface, enhancing the overall corrosion protection.

In NaCl solution, surface morphology is also examined using SEM and AFM. SEM is used to observe changes in surface features under chloride attack, while AFM measures variations in surface roughness [53]. Without CDs, SEM images show clear corrosion pits and surface peeling, indicating severe chloride-induced damage. After adding CDs, the metal surface becomes smoother, and both the number and depth of corrosion pits decrease significantly, demonstrating that CDs effectively slow the corrosion process in NaCl solution [53]. SEM-EDS analysis further supports these observations, showing that after 20-day immersion in NaCl solution without CDs, the surface composition was dominated by Fe (38.98%) and Cl (5.47%), indicating significant chloride adsorption and corrosion product formation. However, with the addition of CDs, the Fe content on the surface increased to 75.76%, and the Cl content decreased to 0.13%, demonstrating that CDs efficiently inhibit chloride-induced corrosion and protect the metal surface [53]. AFM results also show that the surface roughness is high without the inhibitor, whereas the roughness is reduced after adding CDs, confirming the improved corrosion resistance of the metal surface [53,88].

Similar to the situation in acidic solutions, in NaCl solutions, CDs help evaluate the corrosion inhibition ability by focusing on the HOMO–LUMO band gap through quantum chemical calculations and estimating the adsorption energy (Ebinding) via MD simulations. The DFT results show that CDs maintain a small HOMO–LUMO gap in NaCl solution [53,87]. The rationality of such calculations is similarly questioned [82]. MD simulations also show high adsorption energies for CDs in NaCl environments, confirming their ability to form stable protective films on the metal surface. This film reduces chloride attack and effectively suppresses corrosion [91].

Collectively, these results indicate that the synthetic strategy directly governs the performance of CDs in neutral solutions. Hydrothermal/solvothermal methods remain the most reliable for achieving high inhibition efficiencies, while microwave synthesis offers ultrafast preparation. Doping regulation, particularly nitrogen enrichment, plays a decisive role in enhancing Cl− resistance, positioning CDs as promising, eco-friendly alternatives for marine corrosion control.

2.4. CO2-Saturated Solutions

CO2-saturated solutions present a particularly aggressive corrosive environment due to the combined effects of acidification, chloride attack, and the formation of carbonic acid, which accelerates the dissolution of protective oxide films [51]. This scenario is highly relevant to the oil and gas industry, where pipeline steels are continuously exposed to CO2-containing saline waters.

Initial studies by Li’s group demonstrated that microwave-synthesized N-CDs could provide moderate protection for N80 steel in CO2-saturated 3% NaCl solution, but the inhibition efficiencies remained relatively low (η ≈ 83.5–83.7%) even at concentrations as high as 600 mg/L [52,87]. This limitation reflects the challenge of ensuring sufficient active sites and robust adsorption when using rapid synthesis routes such as microwave treatment.

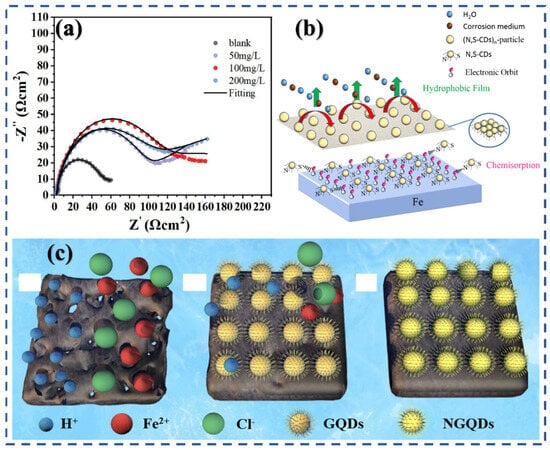

To address this, Chen’s group adopted a hydrothermal synthesis strategy with nitrogen and sulfur precursors, producing N, S-CDs that delivered markedly improved performance, achieving η = 93% at only 50 mg/L [48]. The incorporation of sulfur not only increased the density of active functional groups but also enhanced the ability of CDs to coordinate with Fe2+/Fe3+ ions on the steel surface, thereby stabilizing the adsorbed film. Li further demonstrated that hydrothermally prepared N, S-CDs retained excellent stability at elevated temperatures, maintaining η = 94.6% at 70 °C with a dosage of 200 mg/L (Figure 5a) [88]. This thermal robustness is critical for downhole and high-temperature oilfield applications.

Figure 5.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis and corrosion inhibition mechanism of N,S-doped CDs (N,S-CDs) in CO2-saturated solutions: (a) Nyquist plots of N,S-CDs at varying concentrations in CO2-saturated 3% NaCl solution [88]; (b) Schematic of N,S-CDs coordination with Fe2+/Fe3+ ions and the formation of a protective film; (c) Mechanism of corrosion inhibition by GQDs and NGQDs in CO2-saturated solutions [75,77].

Mechanistically, the superior performance of hydrothermal/solvothermal-derived heteroatom-doped CDs can be attributed to their abundant N and S sites, which promote strong chemisorption through electron donation and back-donation interactions [93,94]. These CDs form compact, protective films that effectively suppress both anodic metal dissolution and cathodic hydrogen evolution in CO2-acidified saline media. By contrast, CDs derived from microwave or pyrolysis routes tend to lack the same surface functional richness, explaining their lower inhibition performance despite faster synthesis (Figure 5 b,c) [75,77].

In summary, the effectiveness of CDs in CO2-saturated solutions is highly dependent on the synthesis method. Hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis, particularly with controlled N, S-doping, provides a rational pathway for producing robust, temperature-resistant inhibitors, underscoring their potential in CO2-rich oilfield conditions.

2.5. Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion

MIC is a critical issue in marine, pipeline, and industrial systems, where microbial activity accelerates metal degradation by generating corrosive metabolites and forming biofilms [49,68,95]. Traditional organic inhibitors often lack antimicrobial activity, which limits their ability to mitigate MIC. In contrast, CDs synthesized via tailored methods can simultaneously inhibit electrochemical corrosion and suppress microbial growth.

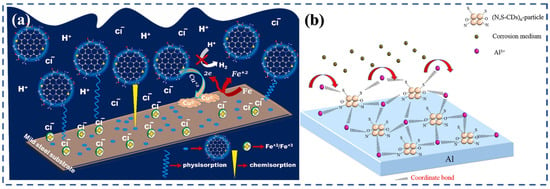

Hydrothermal synthesis has been widely applied to prepare heteroatom- and metal-doped CDs for MIC scenarios. For instance, Ce, N-CDs obtained by hydrothermal treatment displayed enhanced inhibition efficiency compared to undoped CDs, owing to the strong complexation ability of Ce with steel surfaces and its synergistic antibacterial effect [68]. Similarly, Cu, N-CDs showed improved film formation and bactericidal properties, though the gain in η compared to N-CDs was relatively modest (Figure 6a) [78]. This suggests that while metal doping can provide additional antimicrobial benefits, its contribution to corrosion inhibition is less significant than nitrogen doping, and environmental/cost factors should be considered carefully.

Figure 6.

Mechanism of corrosion inhibition and antimicrobial activity of heteroatom-doped CDs in MIC environments: (a) Hydrothermal synthesis of Cu, N-CDs for enhanced corrosion inhibition and bacterial growth suppression [78]; (b) The role of heteroatom doping (N, S, Al) in promoting strong adsorption and dual inhibition effects in NaCl solutions [70].

Chemical oxidation routes have also been employed to prepare multifunctional CDs. N, S-CDs synthesized from gum Arabic and elemental sulfur via oxidation exhibited excellent performance in NaCl solutions, where the abundant O, N, and S functional groups facilitated strong adsorption onto steel and simultaneously disrupted microbial adhesion (Figure 6b) [48,70]. The presence of such heteroatoms increases electron density and enhances interactions with both the metal substrate and bacterial cell membranes, leading to dual inhibition effects.

Mechanistically, the multifunctional behavior of CDs in MIC environments arises from their surface-rich functional chemistry. O- and N-containing groups promote adsorption and protective film formation, reducing anodic dissolution and cathodic reactions, while heteroatom or metal dopants disrupt microbial metabolism and biofilm growth. The synergy between corrosion inhibition and antimicrobial activity positions CDs as unique candidates for marine pipelines and industrial systems where MIC is prevalent.

In summary, the choice of synthesis strategy is crucial: hydrothermal methods allow versatile doping (N, S, Ce, Cu), enhancing both anticorrosion and antimicrobial properties, while chemical oxidation approaches generate heteroatom-rich CDs that combine strong adsorption with biocidal effects. Future development should focus on balancing performance, scalability, and environmental safety in order to optimize CDs for practical MIC mitigation.

In summary, the synthesis route plays a decisive role in determining the surface chemistry, functional group density, and ultimately the corrosion inhibition performance of CDs across different corrosive environments. Hydrothermal and solvothermal methods remain the most reliable strategies, enabling precise control over heteroatom doping and particle size, and consistently yielding high efficiencies in both acidic and chloride-rich media. Biomass-derived CDs further demonstrate the potential of sustainable synthesis for practical applications. Microwave-assisted and pyrolytic methods provide rapid or mechanistic insights, though their reproducibility and scalability require improvement. Chemical oxidation and emerging room-temperature in situ routes offer simplified and energy-efficient preparation, particularly attractive for industrial acidizing and reinforced concrete systems. The diverse application scenarios—from acidic and saline to CO2-saturated, microbiologically influenced, and alkaline environments—highlight the versatility of CDs as green and multifunctional inhibitors. Future research should focus on integrating scalable, low-energy synthesis with rational heteroatom doping to achieve long-term stability, multifunctionality, and environmental compatibility, thereby advancing CDs from laboratory exploration toward real-world corrosion protection.

3. Mechanisms of Corrosion Inhibition by CDs

Understanding the inhibition mechanisms of CDs is essential for elucidating the relationship between their structural features and corrosion protection performance. Unlike conventional organic inhibitors, CDs exhibit multifunctional characteristics arising from their nanoscale dimensions, abundant surface functionalities, and tunable electronic structures through heteroatom doping. These unique features enable CDs to adsorb strongly onto metal substrates, regulate interfacial electron transfer, and provide additional functionalities such as antimicrobial activity. This section systematically discusses the underlying mechanisms of CDs as corrosion inhibitors, focusing on adsorption and film formation, the role of heteroatom doping, electrochemical inhibition pathways, and the synergistic influence of particle size, structural configuration, and sustainable synthesis routes.

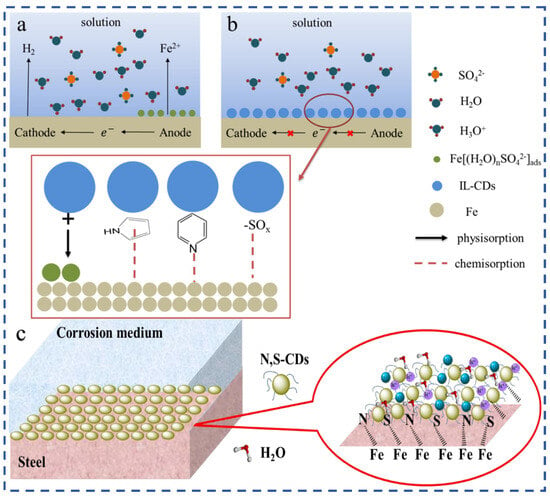

3.1. Adsorption and Film Formation

The fundamental inhibition mechanism of CDs is attributed to their strong adsorption onto metal surfaces, where they assemble into a compact and adherent protective film that effectively isolates the substrate from aggressive ions such as Cl−, SO42−, and H+ [50,58,59]. This adsorption is facilitated by abundant surface functional groups, including –NH2, –OH, –COOH, and –C=O, which serve as active sites for coordination with Fe2+/Fe3+ ions, resulting in robust chemisorption and enhanced interfacial stability (Figure 7a,b) [46,62,63]. Beyond simple physical adsorption, CDs interact through donor–acceptor electron transfer, forming stable complexes with surface metal atoms. Heteroatom doping further enhances this process by introducing electron-rich centers, enabling stronger π–d orbital interactions with vacant d-orbitals of Fe and other transition metals (Figure 7c) [75,76,92].

Figure 7.

Adsorption and film formation mechanism of CDs in corrosion inhibition: (a) Adsorption of IL-CDs on metal surfaces and the formation of a protective film in acidic media; (b) Mechanism of chemisorption and coordination of functional groups with Fe2+/Fe3+ ions [62,63]; (c) Structure of N,S-CDs and their interaction with Fe atoms on steel surfaces in corrosion media [76].

Such adsorption-driven film formation significantly reduces anodic metal dissolution while simultaneously retarding cathodic reactions, including hydrogen evolution in acidic media [47] and oxygen reduction in neutral or alkaline environments [46,90,96]. EIS studies have consistently shown that CDs increase charge transfer resistance (Rct) and reduce double-layer capacitance (Cdl), supporting the formation of dense, continuous films that impede electrolyte penetration. In addition, surface-sensitive techniques such as XPS and AFM reveal the presence of N- and O-rich functional layers that tightly adhere to the metal surface, corroborating the chemisorption model [62,63].

Modern surface analytical techniques, such as XPS, SEM, and AFM, have been widely used to study the interaction between CDs and the metal surface. These techniques provide valuable insights into the formation of protective films and the adsorption mechanisms of CDs, which play a key role in their corrosion inhibition performance.

Recent computational studies have employed modern tools such as DFT, Molecular Dynamics Simulation (MDS), and Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) to explore the inhibition mechanism of CDs. These advanced methods offer insights into the molecular interactions between CDs and metal surfaces, providing a deeper understanding of the underlying inhibition processes and helping to predict the efficiency of CDs as corrosion inhibitors.

Importantly, the film morphology and compactness are closely related to the structural features of CDs. Smaller-sized CDs provide higher surface coverage due to their large surface area, while graphitic domains and π–π conjugated structures contribute to stronger electronic interactions with the substrate [75,76]. Biomass-derived CDs, rich in O- and N-functionalities, not only form robust adsorption layers but also enhance hydrophilicity and film uniformity, further improving inhibition efficiency [65,66,74]. Collectively, these findings establish adsorption and protective film formation as the cornerstone of CD-based corrosion inhibition, enabling durable and broad-spectrum protection across diverse corrosive conditions.

3.2. Influence of Heteroatom Doping and Electronic Structure

Heteroatom doping plays a decisive role in regulating the electronic structure and surface chemistry of CDs, thereby enhancing their corrosion inhibition capability. Among them, nitrogen doping has been most extensively studied, as pyridinic-N, graphitic-N, and amino-N species can significantly increase electron density and facilitate coordination with Fe atoms through π–d orbital interactions [62,75,76]. Such effects improve adsorption strength and result in compact, protective films with high inhibition efficiencies in both acidic and chloride media [46,65,66]. Sulfur doping further contributes to performance enhancement, as the larger atomic radius and higher polarizability of S atoms promote strong binding with metallic surfaces, particularly in CO2-saturated environments [48,88,97]. However, excessive S incorporation may not always be beneficial, since it can alter the balance of surface functional groups and reduce inhibition effectiveness [92]. Oxygen-containing moieties, such as –OH and –COOH, also play a critical role by improving hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions in alkaline systems, reinforcing film stability in highly basic pore solutions [66,70,74]. In addition, metal doping with Ce or Cu has been shown to improve biofilm resistance and antibacterial activity under MIC, while only moderately enhancing film compactness compared to N-CDs (Figure 8) [68,78]. Collectively, the incorporation of heteroatoms tailors the surface electronic properties of CDs, strengthening chemisorption, improving film integrity, and enabling multifunctionality across diverse corrosive environments.

Figure 8.

Influence of heteroatom doping and electronic structure on corrosion inhibition performance of CDs: (a) Adsorption mechanism of N-doped CDs on steel surfaces and coordination with Fe atoms; (b) Schematic of the synergistic effects of N doping on enhancing adsorption and film formation in corrosion media [68,83].

3.3. Electrochemical Inhibition Pathways

Electrochemical studies consistently demonstrate that CDs function as mixed-type inhibitors, simultaneously suppressing anodic metal dissolution and cathodic reduction reactions [46]. In acidic environments, CDs adsorb strongly onto the steel surface, retarding the anodic oxidation of Fe to Fe2+, while also reducing the kinetics of the cathodic hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) [50,58,59]. This dual suppression mitigates the aggressive attack of H+ ions, leading to significantly reduced corrosion current densities (Icorr) and improved inhibition efficiencies. Potentiodynamic polarization (PDP) curves frequently show parallel shifts in both anodic and cathodic branches, confirming the mixed-type inhibition behavior of CDs [46,66]. As shown in Figure 9a, the PDP curves exhibit a pronounced decrease in corrosion current density and a clear shift in both anodic and cathodic branches toward lower current regions, indicating that prolonged exposure leads to the development of a more protective surface layer and stable inhibition behavior [53].

Figure 9.

(a) PDP results of carbon steel after 20-day immersion in chloride-contaminated simulated concrete pore solution [53]; (b) PDP in various situations of CDs [80].

In neutral chloride solutions, CDs effectively protect against localized pitting corrosion by forming compact films that act as physical barriers to Cl− penetration. At the same time, they reduce the rate of the cathodic oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), which is the dominant cathodic process in aerated saline environments [90,91,96]. Potentiodynamic polarization analysis further shows that the addition of CDs markedly lowers the corrosion current density and shifts both anodic and cathodic branches toward lower current regions (Figure 9b), indicating a strong inhibitory effect and the formation of a more stable interfacial film [80]. The incorporation of heteroatoms such as N and S further enhances these effects by improving electron transfer resistance and stabilizing the adsorbed film.

In CO2-saturated saline environments, CDs suppress both anodic and cathodic currents, but their impact on the hydrogen evolution reaction is particularly important [48,52,88]. By reducing HER kinetics, CDs mitigate the synergistic corrosive effects of carbonic acid and chloride ions, thereby preserving the stability of passive films [98,99]. Notably, temperature-dependent studies have shown that heteroatom-doped CDs can maintain high inhibition efficiencies even at elevated temperatures, highlighting their robustness for oilfield and downhole applications [88].

In alkaline environments such as concrete pore solutions, CDs primarily hinder the cathodic oxygen reduction reaction and reduce chloride-induced depassivation at anodic sites [66,70]. Functional groups such as –OH and –COOH enhance electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions with Fe hydroxides, reinforcing the passive film and stabilizing the metal–solution interface.

Overall, PDP and EIS analyses consistently indicate that CDs increase Rct, decrease Icorr, and reduce Cdl across different environments, confirming their ability to block electron transfer processes and suppress both anodic and cathodic reactions [46,66,96]. Mechanistically, this dual inhibition is attributed to their unique surface chemistry, nanoscale dimensions, and strong adsorption capability, which collectively enable CDs to act as versatile and effective corrosion inhibitors.

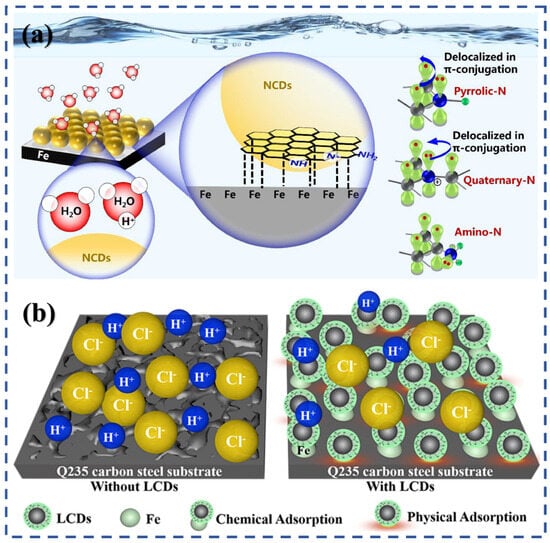

3.4. Synergistic Effects of Size, Structure, and Sustainability

The inhibition performance of CDs is not determined by a single factor but rather by the synergistic interplay among their size, structural features, and sustainability-related advantages. At the nanoscale, the ultra-small size and high surface-to-volume ratio of CDs allow them to disperse uniformly and adsorb effectively on steel surfaces, minimizing defects and ensuring dense surface coverage (Figure 10a) [46,63]. This characteristic improves their ability to block active sites and inhibit both uniform and localized corrosion, especially in chloride-rich and acidic environments. Furthermore, their quantum confinement effect imparts excellent electron-transfer capabilities, which enhance charge redistribution at the metal–solution interface, thereby strengthening the inhibition of both anodic and cathodic processes [90,96].

Figure 10.

Synergistic effects of size, structure, and sustainability of CDs in corrosion inhibition: (a) Adsorption and film formation mechanism of N, S-CDs on steel surfaces [63]; (b) Surface functional groups and heteroatom doping enhancing corrosion inhibition and film stability [58]; (c) Synthesis process and sustainable production of CDs from biomass and natural precursors [66].

The structural features of CDs, particularly surface functional groups and heteroatom doping, strongly influence their adsorption and film-forming properties. Oxygen-rich groups (–OH, –COOH, –C=O) facilitate hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions with metal hydroxides, while N- and S-containing groups donate lone-pair electrons to the metal d-orbitals, enhancing chemisorption and film stability (Figure 10b) [58,70,96]. Additionally, graphitic domains within CDs improve their electron-delocalization ability, contributing to high Rct observed in EIS studies. These structural attributes, when combined, lead to the formation of compact, robust protective films capable of resisting aggressive ionic penetration and sustaining inhibition performance under dynamic conditions [48,52].

Beyond electrochemical efficiency, the sustainability aspect of CDs offers unique advantages compared to conventional inhibitors. Many CDs can be synthesized from renewable biomass, natural polymers, or benign organic precursors, reducing both production cost and environmental impact. Figure 10c illustrates a sustainable synthesis strategy for CDs. Unlike heavy-metal-based inhibitors, CDs are generally non-toxic, biodegradable, and compatible with green chemistry principles, making them suitable for applications in concrete, oilfield, and marine environments where environmental regulations are increasingly stringent. The ability to design CDs with tailored properties via green synthesis routes further supports their potential as next-generation eco-friendly inhibitors.

Taken together, the nanoscale size, versatile structure, and sustainable origin of CDs act synergistically to deliver high η values, long-term stability, and environmental compatibility. This integrated performance profile distinguishes CDs from conventional inhibitors and underscores their promise for widespread practical application in diverse corrosive environments.

In summary, the corrosion inhibition of CDs originates from a combination of adsorption-driven film formation, heteroatom-enhanced coordination, and modulation of anodic and cathodic reactions at the metal–solution interface. Nitrogen, sulfur, and oxygen doping significantly tailor the electronic structure, thereby improving adsorption strength and film compactness, while metal doping introduces additional antimicrobial functionality in microbiologically influenced environments. Electrochemical studies consistently confirm that CDs act as mixed-type inhibitors, effectively reducing both anodic dissolution and cathodic reduction across diverse corrosive systems. Furthermore, particle size, graphitic structure, and sustainable synthesis pathways exert synergistic effects that determine overall efficiency and practical applicability. Collectively, these mechanistic insights not only rationalize the superior performance of CDs but also provide a foundation for the rational design of next-generation, eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors with multifunctional capabilities.

4. Conclusions and Future Prospects

In conclusion, this review summarizes the recent progress of CDs as corrosion inhibitors, focusing on synthesis strategies, application scenarios, and inhibition mechanisms. Hydrothermal and solvothermal methods remain the most reliable synthesis routes, offering precise control over heteroatom doping and particle size, while biomass-derived and in situ strategies highlight the potential for sustainable and scalable applications. CDs have demonstrated broad-spectrum efficiency across diverse corrosive environments, including acidic, neutral chloride, CO2-saturated, alkaline, and microbiologically influenced systems, with particularly high performance in acidic and CO2-rich conditions. Mechanistically, their inhibition originates from strong adsorption onto metal surfaces, heteroatom-enhanced electronic interactions, and the suppression of both anodic and cathodic reactions through compact protective film formation. Despite these advances, several challenges remain:

(1) Absence of precise synthesis control. Current methods struggle to finely regulate particle size, structure, and heteroatom doping, often resulting in CDs with impurities such as amorphous carbon or residual polymers, which lowers inhibition consistency.

(2) Lack of standardized testing protocols. Reported inhibition efficiencies are obtained under varied exposure times and conditions, making direct comparisons across studies difficult.

(3) Inefficient development strategies. Trial-and-error approaches dominate the design of CDs inhibitors, which is both time-consuming and environmentally costly. Integrating computational tools such as machine learning could accelerate the screening of high-performance CDs while reducing experimental workload.

(4) Incomplete mechanistic understanding. Although adsorption-driven film formation is widely proposed, direct structural evidence remains limited, and the undefined structures of CDs further complicate interpretation. Advanced surface characterization techniques and theoretical modeling are therefore needed to elucidate precise structure–function relationships.

Future research should prioritize the development of scalable green synthesis methods for industrial production and explore the environmental impact and cost-effectiveness of CDs in practical applications, particularly in concrete, marine, and oilfield environments. Collectively, addressing these challenges through scalable green synthesis, standardized evaluation, and advanced mechanistic investigations will accelerate the transition of CDs from laboratory studies to practical, industrially viable corrosion inhibitors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H.; methodology, T.H.; software, S.Z.; validation, Y.W.; formal analysis, S.S.; formal analysis, J.H.; methodology, S.W.; investigation, C.L.; writing—review and editing, C.H.; supervision, visualization, funding acquisition, H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the 2024 Construction Research Projects of the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (No. 2024K061 and 2024K062), and the ‘Pioneer’ and ‘Leading Goose’ R&D Program of Zhejiang (2023C03135).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kebin Li for his valuable theoretical guidance on the molecular dynamics and quantum chemistry calculations during the revision of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yin Hu, Tianyao Hong, Sheng Zhou, Chuang He were employed by the company Wenling Construction Engineering Quality Inspection Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The company had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CDs | Carbon dots |

| GQDs | Graphene quantum dots |

| CNDs | Carbon nanodots |

| PDs | Polymer dots |

| MIC | Microbiologically influenced corrosion |

| N-CDs | N-doped CDs |

References

- Hou, B.; Li, X.; Ma, X.; Du, C.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, M.; Xu, W.; Lu, D.; Ma, F. The cost of corrosion in China. npj Mater. Degrad. 2017, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, C.; Ebenso, E.E.; Bahadur, I.; Quraishi, M.A. An overview on plant extracts as environmental sustainable and green corrosion inhibitors for metals and alloys in aggressive corrosive media. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 266, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, C.; Olasunkanmi, L.O.; Ebenso, E.E.; Quraishi, M.A. Substituents effect on corrosion inhibition performance of organic compounds in aggressive ionic solutions: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 251, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Malviya, M.; Verma, C.; Quraishi, M.A. Aminoazobenzene and diaminoazobenzene functionalized graphene oxides as novel class of corrosion inhibitors for mild steel: Experimental and DFT studies. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 198, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Malviya, M.; Verma, C.; Gupta, N.K.; Quraishi, M.A. Pyridine-based functionalized graphene oxides as a new class of corrosion inhibitors for mild steel: An experimental and DFT approach. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 39063–39074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhashem, S.; Rashidi, A.; Vaezi, M.R.; Bagherzadeh, M.R. Excellent corrosion protection performance of epoxy composite coatings filled with amino-silane functionalized graphene oxide. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 317, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; Huang, T.-C.; Peng, C.-W.; Yeh, T.-C.; Lu, H.-I.; Hung, W.-I.; Weng, C.-J.; Yang, T.-I.; Yeh, J.-M. Novel anticorrosion coatings prepared from polyaniline/graphene composites. Carbon 2012, 50, 5044–5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannuzzi, M.; Frankel, G.S. The carbon footprint of steel corrosion. npj Mater. Degrad. 2022, 6, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.-G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wan, S.; Song, L.-F.; Liao, B.-K.; Guo, X.-P. Modified nano-lignin as a novel biomass-derived corrosion inhibitor for enhanced corrosion resistance of carbon steel. Corros. Sci. 2024, 227, 111705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A.; Farhadian, A.; Berisha, A.; Shaabani, A.; Varfolomeev, M.A.; Mehmeti, V.; Zhong, X.; Yousefzadeh, S.; Djimasbe, R. Novel sucrose derivative as a thermally stable inhibitor for mild steel corrosion in 15% HCl medium: An experimental and computational study. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 136938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Qiang, Y.; Zhao, W. Designing novel organic inhibitor loaded MgAl-LDHs nanocontainer for enhanced corrosion resistance. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 408, 127367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioč, E.K.; Gretić, Z.H.; Ćurković, H.O. Modification of cupronickel alloy surface with octadecylphosphonic acid self–assembled films for improved corrosion resistance. Corros. Sci. 2018, 134, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Wang, C.; Yang, M.; Zou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Q.; Wang, X.; Shao, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Ju, J.; et al. Self-assembly Zn-containing layer on PEO-coated Mg with enhanced corrosion resistance, antibacterial activity, and osteogenic property. Corros. Sci. 2023, 226, 111674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daroonparvar, M.; Khan, M.U.F.; Saadeh, Y.; Kay, C.M.; Kasar, A.K.; Kumar, P.; Esteves, L.; Misra, M.; Menezes, P.; Kalvala, P.R.; et al. Modification of surface hardness, wear resistance and corrosion resistance of cold spray Al coated AZ31B Mg alloy using cold spray double layered Ta/Ti coating in 3.5 wt % NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2020, 176, 109029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Cui, M.; Liu, C.; Wang, L. A comprehensive review on ultrathin, multi-functionalized, and smart graphene and graphene-based composite protective coatings. Corros. Sci. 2023, 212, 110939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Chen, X.; Mei, S.; Ren, S. Bioinspired polydopamine nanosheets for the enhancement in anti-corrosion performance of water-borne epoxy coatings. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.-J.; Liu, W.; Zhu, C.; Liu, F.; Li, W. Confinement assembly of a novel Nb2O5&ZnIn2S4 photoanode and its highly efficient and sensitive photoelectrochemical cathodic protection performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 463, 142233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, L.; Xu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yang, C. Efficient self-powered cathodic corrosion protection system based on multi-layer grid synergistic triboelectric nanogenerator and power management circuits. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, A.; Bahlakeh, G.; Ramezanzadeh, B.; Ramezanzadeh, M. Potential role of a novel green eco-friendly inhibitor in corrosion inhibition of mild steel in HCl solution: Detailed macro/micro-scale experimental and computational explorations. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 245, 118464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Gao, L. Excellent performance of dodecyl dimethyl betaine and calcium gluconate as hybrid corrosion inhibitors for Al alloy in alkaline solution. Corros. Sci. 2022, 207, 110556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Hu, J.; Eliaz, N.; Zhou, L.; Yuan, X.; Zhong, X. Mercaptopropionic acid-modified oleic imidazoline as a highly efficient corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in CO2-saturated formation water. Corros. Sci. 2022, 194, 109930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; An, L.; Wang, J.; Gu, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, X. Frontiers and advances in N-heterocycle compounds as corrosion inhibitors in acid medium: Recent advances. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 321, 103031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, I.; Moriarty, M.; House, K.; Sui, J.; Cullen, W.R.; Saper, R.B.; Reimer, K.J. Bioaccessibility of lead and arsenic in traditional Indian medicines. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 4545–4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schem, M.; Schmidt, T.; Gerwann, J.; Wittmar, M.; Veith, M.; Thompson, G.E.; Molchan, I.S.; Hashimoto, T.; Skeldon, P.; Phani, A.R.; et al. CeO2-filled sol–gel coatings for corrosion protection of AA2024-T3 aluminium alloy. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 2304–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Jin, M.; Yan, Y.; Tang, J.; Jin, Z. A review of organic corrosion inhibitors for resistance under chloride attacks in reinforced concrete: Background, Mechanisms and Evaluation methods. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 433, 136583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsani, A.; Mahjani, M.G.; Hosseini, M.; Safari, R.; Moshrefi, R.; Shiri, H.M. Evaluation of Thymus vulgaris plant extract as an eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor for stainless steel 304 in acidic solution by means of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, electrochemical noise analysis and density functional theory. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 490, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, M.; Fadhil, A.A.; Fu, C.; Chen, T.; Chen, M.; Khadom, A.A.; Mahood, H.B. Preparation characterization, and corrosion inhibition performance of graphene oxide quantum dots for Q235 steel in 1 M hydrochloric acid solution. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 627, 127209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhang, R.; Tan, B.; Li, W.; Liu, H.; Wu, S. Locust Bean Gum as a green and novel corrosion inhibitor for Q235 steel in 0.5 M H2SO4 medium. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 310, 113239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustin, M.; Maciuk, A.; Salvin, P.; Roos, C.; Lebrini, M. Corrosion inhibition of C38 steel by alkaloids extract of Geissospermum laeve in 1M hydrochloric acid: Electrochemical and phytochemical studies. Corros. Sci. 2015, 92, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourya, P.; Banerjee, S.; Singh, M.M. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in acidic solution by Tagetes erecta (Marigold flower) extract as a green inhibitor. Corros. Sci. 2014, 85, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Xiang, B.; Zhang, S.; Qiang, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, S.; He, J. Papaya leaves extract as a novel eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor for Cu in H2SO4 medium. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 582, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Guo, L.; She, Y. Insight on the corrosion inhibition performance of Psidium guajava linn leaves extract. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 346, 117858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Tang, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Zhong, H.; Yu, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, C.; Jiang, Q.; Ye, Y.; et al. A green and effective anti-corrosion and anti-microbial inhibitor of citric acid-based carbon dots: Experiment and mechanism analysis. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 32, 2149–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Gong, X. The Emerging Star of Carbon Luminescent Materials: Exploring the Mysteries of the Nanolight of Carbon Dots for Optoelectronic Applications. Small 2024, 20, e2400107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Wang, J.H.; Mao, Q.; Chen, X. Tunable Organelle Imaging by Rational Design of Carbon Dots and Utilization of Uptake Pathways. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 14465–14474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Sun, T.; Wang, X.; He, H.; E, S. Development of high-dispersion CLDH/carbon dot composites to boost chloride binding of cement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 152, 105669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Shuang, E.; Lu, D.; Hu, Y.; Yan, C.; Shan, H.; He, C. Deciphering size-induced influence of carbon dots on mechanical performance of cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 425, 136030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Bai, R.; Huang, J.; Bian, X.; Fu, Y. Machine learning-assisted carbon dots synthesis and analysis: State of the art and future directions. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2025, 184, 118141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, S.; Xing, Y.Z.; Du, S.; Liu, A.M.; Gao, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Xuan, Y.; Zhao, Y.N.; Chen, X.W.; Zhang, S.B. Shape Control of Carbon Nanoparticles via a Simple Anion-Directed Strategy for Precise Endoplasmic Reticulum-Targeted Imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202311008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Bai, J.; Yang, G.; Qin, F.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Yao, Y.; Tang, X.; Ren, L. Regulation of the unconventional luminescence behaviors of phenylenediamine-based carbon dots with high PLQY values. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 160342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Raj, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Wang, K.; Lin, L.; Hou, W.; Zhang, J.; Wu, M.; Wu, J.; et al. Synergistic Effects of Amine Functional Groups and Enriched-Atomic-Iron Sites in Carbon Dots for Industrial-Current–Density CO2 Electroreduction. Small 2024, 20, 2311132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; Liu, C.; Nan, X.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, L.; Lin, X.; Zhang, H.; Yang, M.; Fang, X.; Luo, Y.; et al. Carbon dots-based electrochemical and fluorescent biosensors for the detection of foodborne pathogens: Current advance and challenge. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 529, 216457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; E, S.; Yan, H.; Li, X. Structural engineering design of carbon dots for lubrication. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 2693–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Zhao, J.; He, H.; Wang, B. A comprehensive review on the applications of carbon dots in civil engineering materials. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 3227–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Song, Y.; Zhao, X.; Shao, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, B. The photoluminescence mechanism in carbon dots (graphene quantum dots, carbon nanodots, and polymer dots): Current state and future perspective. Nano Res. 2015, 8, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Ren, S.; Xue, Q.; Zhao, H.; Wang, L. Carbon dots as new eco-friendly and effective corrosion inhibitor. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 726, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zou, Y.; Chen, H.; Guo, S.; Yang, Q.; Chen, L. Evaluation of the inhibition behavior of carbon dots on carbon steel in HCl and NaCl solutions. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 43, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, H.; Chen, Z.; Guo, X. N, S co-doped carbon dots as effective corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in CO2-saturated 3.5% NaCl solution. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2019, 99, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalajahi, S.T.; Rasekh, B.; Yazdian, F.; Neshati, J.; Taghavi, L. Green mitigation of microbial corrosion by copper nanoparticles doped carbon quantum dots nanohybrid. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 40537–40551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ansari, K.R.; Chauhan, D.S.; Quraishi, M.A.; Lgaz, H.; Chung, I.-M. Comprehensive investigation of steel corrosion inhibition at macro/micro level by ecofriendly green corrosion inhibitor in 15% HCl medium. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 560, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdimurodov, E.; Verma, D.K.; Kholikov, A.; Akbarov, K.; Guo, L. The recent development of carbon dots as powerful green corrosion inhibitors: A prospective review. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 349, 118124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lv, J.; Fu, L.; Tang, M.; Wu, X. New Ecofriendly Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots as Effective Corrosion Inhibitor for Saturated CO2 3% NaCl Solution. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2020, 93, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.-J.; Li, X.-Q.; Zheng, S.-Y.; He, C. A novel effective carbon dots-based inhibitor for carbon steel against chloride corrosion: From inhibition behavior to mechanism. Carbon 2023, 218, 118708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, C.; He, C. Research progress of carbon dots as novel corrosion inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1334, 141894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jahdaly, B.A.; Elsadek, M.F.; Ahmed, B.M.; Farahat, M.F.; Taher, M.M.; Khalil, A.M. Outstanding Graphene Quantum Dots from Carbon Source for Biomedical and Corrosion Inhibition Applications: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, C.; Alfantazi, A.; Quraishi, M.A. Quantum dots as ecofriendly and aqueous phase substitutes of carbon family for traditional corrosion inhibitors: A perspective. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 343, 117648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.W.J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhang, D. Research progress of carbon dots in the field of metal corrosion and protection. Surf. Technol. 2024, 53, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Wu, R.; Luo, Y.; Guo, L.; He, Z. Green and high-efficiency corrosion inhibitors for metals: A review. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2022, 37, 1501–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panossian, Z.; Almeida, N.L.D.; Sousa, R.M.F.D.; Pimenta, G.D.S.; Marques, L.B.S. Corrosion of carbon steel pipes and tanks by concentrated sulfuric acid: A review. Corros. Sci. 2012, 58, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, L.; Zhou, T.-Y. Inhibition Behavior of Graphene Quantum Dots for Carbon Steel in HCl Solution. Corros. Prot. 2015, 36, 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- S, E.; Gao, Z.; Cong, X.; He, C.; Gao, L.; Yin, Z. Novel green corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel: A comprehensive analysis of the effect of nitrogen content on corrosion inhibition performance. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 320, 122394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Ren, S.; Zhao, H.; Wang, L.; Xue, Q. Novel nitrogen doped carbon dots for corrosion inhibition of carbon steel in 1 M HCl solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 443, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, H.; Tan, B.; Wang, L. Enhanced anticorrosion performance of copper by novel N-doped carbon dots. Corros. Sci. 2019, 161, 108193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Yang, D.; Chen, H. A green and effective corrosion inhibitor of functionalized carbon dots. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 2243–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.-J.; Li, X.-Q.; Yu, Y.; He, C. Green synthesis of biomass-derived carbon dots as an efficient corrosion inhibitor. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 360, 119522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, R.; Sun, X.; Aslam, R.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, C.; Sun, Y.; Yan, Z.; Li, X. Protein-derived carbon dots as green corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in sulfuric acid solution. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 145, 111135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Li, X.-Q.; Feng, G.-L.; Long, W.-J. A universal strategy for green and in situ synthesis of carbon dot-based pickling solution. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 5842–5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Huang, W.; Liu, L.; Li, H.; Meng, H.; Zeng, T.; Ye, X.; Jiang, Q.; Ye, Y.W.; Liu, Y. Study on structure and molecular scale protection mechanism of green Ce,N-CDs anti-bacterial and anti-corrosive inhibitor. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 28, 3865–3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Chen, H.; Liao, B.; Guo, X. Adsorption and anticorrosion mechanism of glucose-based functionalized carbon dots for copper in neutral solution. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2021, 129, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Z.; Guo, X. Carbon dots as effective corrosion inhibitor for 5052 aluminium alloy in 0.1 M HCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2019, 161, 108197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Lian, Y.; Qiao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Meng, X.; Ma, K.; Zhu, D.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H. N-doped carbon quantum dots as corrosion inhibitor for ultra-high voltage etched Al foil. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 476, 130240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Feng, L.; Hu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhu, H.; Ma, X. Study on the corrosion inhibition of biomass carbon quantum dot self-aggregation on Q235 steel in hydrochloric acid. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Gan, Y.; Zeng, J.; Chen, J.; Fu, A.; Zheng, X.; Li, W. Green synthesis of functionalized fluorescent carbon dots from biomass and their corrosion inhibition mechanism for copper in sulfuric acid environment. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ren, H.; Gong, Z.; Tan, B.; Lan, W.; Dai, Q.; Zheng, X.; Guo, L.; Alobaid, A.A.; Warad, I. Melon seed shell synthesis N, S-carbon quantum dots as ultra-high performance corrosion inhibitors for copper in 0.5 M H2SO4. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 137, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xu, H. The effect of pyrrolic nitrogen on corrosion inhibition performance of N-doped carbon dots. Surf. Interfaces 2023, 44, 103740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cao, S.; Sun, Y.; Liu, D.; Pan, S.; Ma, A.; Kuvarega, A.T.; Mamba, B.B.; Gui, J. Ionic liquid-assisted preparation of N, S-rich carbon dots as efficient corrosion inhibitors. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 356, 118943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Shi, J.; Yu, S.; Yang, J.; Xu, K.; He, C.; Li, X. Exploring green and efficient zero-dimensional carbon-based inhibitors for carbon steel: From performance to mechanism. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 411, 134334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhan, S.; Rout, T.K.; Nair, U.G. N-doped carbon dots as corrosion inhibitor for mild steel corrosion in acid medium. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 653, 129905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Tang, M.; Qiang, Y.; Deng, S.; Li, X. High-value utilization of renewable biofuel tree species waste: Inhibition mechanism of carbon steel in trichloroacetic acid by Jatropha curcas L. cake meal carbon dots. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 729, 138847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; He, H.; Qiao, H.; Wang, S.; He, C.; Xiang, T. Carbon dot aggregates: A new strategy to promote corrosion inhibition performance of carbon dots. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 1479–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wei, G.; Deng, S.; Li, X. Valorization strategy of invasive weed: Interfacial corrosion inhibition of steel in 1.0 M HCl media by Erigeron canadensis extract. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 6363–6380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokalj, A.; Lozinšek, M.; Kapun, B.; Taheri, P.; Neupane, S.; Losada-Pérez, P.; Xie, C.; Stavber, S.; Crespo, D.; Renner, F.U.; et al. Simplistic correlations between molecular electronic properties and inhibition efficiencies: Do they really exist? Corros. Sci. 2021, 179, 108856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, C.; Yu, K.; Luo, Q.; Long, W. Facile Preparation and Characterization of Carbon Dots with Schiff Base Structures Toward an Efficient Corrosion Inhibitor. Surf. Technol. 2023, 52, 229. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, G.; Xue, S.; Zhao, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Ye, Q.; Zhou, F. N-doped carbon dots based nano-composite coatings with ultra-low coefficient of friction and superior corrosion resistance. Friction 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooja, K.; Kumari, K.; Kumar, M.R.; Mahendra, Y. Synthesis of novel carbon dots as efficient green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in an acidic environment: Electrochemical, gravimetric, and XPS analysis. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 209, 109561. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.; Zhao, P.; Guo, L.; Zhu, L.; Lgaz, H.; Adam, A.M.M. Spent coffee grounds-derived N-doped carbon dots as efficient green corrosion inhibitors for Q235 steel in acidic environment. Prog. Org. Coat. 2026, 210, 109700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, J.; Lv, J.; Deng, C.; Yang, L. Novel Carbon Dots for Corrosion Inhibition of N80 Carbon Steel in 3% Saturated CO2 Saline Solution. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2021, 94, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, J.; Deng, C.; Yang, L.; Lv, J.; Fu, L. Novel carbon dots as effective corrosion inhibitor for N80 steel in 1 M HCl and CO2-saturated 3.5 wt% NaCl solutions. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1250, 131897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Li, D.; Chen, Z.; Yin, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, W. Sulfur dots corrosion inhibitors with superior antibacterial and fluorescent properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 654, 878–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Wang, Q.; Yang, S.; Tang, Y.; Liu, X.; Lu, S. Hydrothermal route upcycling surgical masks into dual-emitting carbon dots as ratiometric fluorescent probe for Cr (VI) and corrosion inhibitor in saline solution. Talanta 2024, 275, 126070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, D.; Wu, P.; Gao, L. Corrosion inhibition of high-nitrogen-doped CDs for copper in 3wt% NaCl solution. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2022, 138, 104462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Cheng, X.; Chen, X.; Zhong, C.F.; Xie, H.; Ye, Y.W.; Zhao, H.C.; Li, Y.; Chen, H. The effect of N and S ratios in N, S co-doped carbon dot inhibitor on metal protection in 1 M HCl solution. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2021, 127, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qu, W.; Su, H.; Li, M.; Cui, N.; Sun, S.; Fu, Y.; Hu, S. Ce-doped carbon dots enhanced by ionic liquids: A potent corrosion shield for N80 steel in aggressive 1M HCl environment. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 709, 136132. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, R.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Yan, Z. Fabrication, characterization and corrosion inhibition performance of sustainable metal-organic framework nanocomposite. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 720, 137095. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Jin, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Liu, H.; Yuan, X.; Fan, S.; Liu, H. Insights into the hydrophobic coating with integrated high-efficiency anti-corrosion, anti-biofouling and self-healing properties based on anti-bacterial nano LDH materials. Corros. Sci. 2024, 231, 111995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Ye, Y.; Su, Y.; Liu, S.; Gong, D.; Zhao, H. Functionalization of citric acid-based carbon dots by imidazole toward novel green corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswat, V.; Yadav, M. Carbon Dots as Green Corrosion Inhibitor for Mild Steel in HCl Solution. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 7347–7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Li, X.; Tan, B.; Yang, S.; Deng, S. Hydrothermal synthesis of peanut shell-derived carbon dots as the novel efficient inhibitor for the corrosion of steel. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2026, 728, 138517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Deng, S.; Qiang, Y.; Li, X. Nature’s nano-shield: Jatropha curcas fruit seeds meal derived carbon dots as potent green inhibitor. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 262, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).