Abstract

In deep coal mining, fault slip-type rockbursts occur frequently. Understanding the shear mechanical properties of bedded coal seams and their intrinsic mechanisms is crucial. This study used PFC2D7.0 numerical simulation to systematically investigate the shear mechanical behavior and micro-mechanisms of bedded coal under different normal stresses (1, 2, 3, 4 MPa). The research results show that: (1) The shear stress-displacement curves of bedded coal show three stages: elastic rise, strain softening, and residual stability. Both peak and residual shear strengths increase with the rise in normal stress. The peak strength shows nonlinear growth, while the residual strength exhibits a good linear relationship. Higher normal stress significantly reduces the strength reduction rate and effectively inhibits the brittleness of coal. (2) The failure mode consistently manifests as shear failure along the preset weak bedding plane, forming a distinct shear zone. Crack evolution analysis shows that shear cracks within the bedding are the primary form of damage, with minimal contribution from tensile cracks. (3) Force chain analysis shows that an increase in normal stress significantly enhances the density and connectivity of compressive force chains within the shear zone. It also effectively inhibits tensile force chains, with the bedding plane consistently serving as the primary area for stress concentration and transfer. This study provides important theoretical references for understanding the shear instability mechanism of bedded coal, predicting its mechanical response, and preventing fault slip-type rockbursts in deep coal mines.

1. Introduction

Coal is the cornerstone of China’s energy structure. It provides important support for promoting national economic development and ensuring energy security. However, with the gradual depletion of shallow coal resources, mining activities have expanded to deep underground [1,2]. The mining depth of coal mines is increasing at an annual rate of 10–15 m [3], and the exploitation of deep well resources at the kilometer level has become the norm. Deep coal mining faces prominent problems such as high ground stress, high gas content, high temperature, and strong mining disturbance [4]. These problems pose great challenges to the safe exploitation of coal resources.

During the mining process of deep coal seams, rockburst disasters occur frequently. According to the occurrence mechanism of rockbursts, they can be divided into three types [5,6]: coal compression-type rockburst, floor-fracture-type rockburst, and fault-slip-type rockburst. Among them, fault-slip-type rockburst covers a wide range and causes extremely severe damage. Fault-slip-type rockburst refers to shear instability failure caused by dislocation between faults and coal, which is affected by mining activities [7,8]. Therefore, the shear failure of coal is one of the core mechanical mechanisms inducing this disaster. Scholars at home and abroad have conducted numerous systematic studies on the shear mechanical properties of coal. They have revealed the laws and mechanisms of coal shear behavior from different perspectives. Song et al. [9] studied the mechanical responses of dry coal and water-immersed coal in underground coal mines under complex normal and shear stresses through experiments. They analyzed the effects of stress paths, water immersion, and frequency on deformation, energy dissipation, and other aspects. Wu et al. [10] investigated the mechanical properties and microcrack fracture behavior of coal samples under compression-shear coupling at different dip angles and loading rates. They found that dip angle and loading rate have significant effects on peak stress, failure mode, and crack initiation and damage thresholds. He et al. [11] studied the mechanical properties and microcrack propagation of coal samples under quasi-static compression-shear combined loads using an improved rock performance testing system and acoustic emission technology. They found that the dip angle of the sample affects its failure mode and peak strength and suggested considering coal strength under compression-shear loads in the pillar strength formula. Tang et al. [12] researched the shear failure and crack propagation of coal samples with different water contents. They found that increased water content reduces mechanical parameters such as shear strength and divided the crack evolution stages with the help of acoustic emission and CT technologies. Shen et al. [13] proposed a nonlinear shear strength model considering uniaxial compressive strength and confining pressure. This model can estimate Mohr-Coulomb parameters and has good prediction performance.

Coal, as a sedimentary rock, has obvious bedding structures [14,15]. The cementation strength of bedding is lower than that of the coal matrix. It significantly weakens the continuity and integrity of the coal mass. Affected by the weak cementation property of bedding planes, coal exhibits typical anisotropic characteristics in deformation, strength, permeability, and crack evolution [16,17]. Many scholars have conducted extensive research on this. Huang et al. [18] analyzed the mechanical properties, acoustic emission characteristics, and energy evolution law of bedded coal through uniaxial compression tests. They revealed its damage anisotropy mechanism and established a uniaxial damage evolution model, providing theoretical support for coal pillar stability evaluation. Gao et al. [19] used the Split-Hopkinson-Pressure-Bar (SHPB) system to explore the mechanical response and seepage characteristics of gas-bearing coal with different bedding angles under impact loads. The established damage-seepage model is consistent with the experiment. Tan et al. [20] simulated the SHPB test of coal samples with bedding planes at different angles using Particle Flow Code 2D(PFC2D). They found that bedding planes weaken the mechanical properties of coal, and the weakening effect is most significant at 30° or 45°. In addition, energy characteristics are positively correlated with strength and failure mode. Liu et al. [21] studied the effect of bedding on coal deformation and permeability evolution through experiments under true triaxial stress conditions. They established a stress–strain analysis model and a permeability model for bedded coal, quantified the effect of bedding, and verified the model reliability. Liu et al. [15] studied the deformation field evolution of coal samples with parallel bedding under vertical and parallel bedding loading via the digital image correlation method. They defined damage variables and established a damage constitutive model, revealing the effect of bedding on deformation localization and damage characteristics. Du et al. [22] researched the cracking mode and damage evolution characteristics of coal with bedding structures under liquid nitrogen cooling. They found that liquid nitrogen promotes thermal crack development, and bedding angle affects the failure mode and damage degree. They suggested conducting liquid nitrogen fracturing along bedding planes to improve the permeability of low-permeability coal seams. Duan et al. [14] pointed out that different bedding angles and true triaxial stress states significantly affect the mechanical and seepage properties of coal seams. An increase in bedding angle reduces peak stress and enhances permeability, while the stress state affects the failure mode by changing shear stress and normal stress.

In summary, existing studies have explored the shear mechanical properties of coal seams and the influence of bedding structures from various aspects, providing important references for understanding the mechanical behavior of coal seams and the mechanisms of engineering hazards. However, current research still has limitations. The investigation into the mechanical response of bedded coal seams under shear loading is not yet systematic, particularly lacking quantitative correlations among shear strength parameters, failure modes, and energy evolution under the coupled effects of multiple factors such as bedding angle and stress state. To address these issues, the study focuses on the shear mechanical properties of bedded coal seams. Through experiments and theoretical analysis, it aims to reveal the influence of bedding characteristics on coal shear strength, failure modes, and energy dissipation, thereby clarifying the mechanical mechanisms of shear instability in bedded coal.

2. Numeric Simulation Scheme

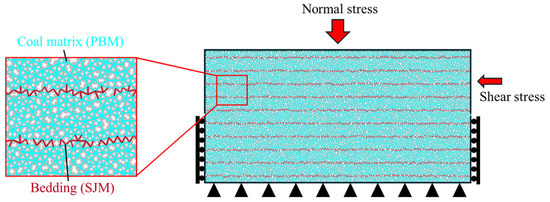

This study uses PFC2D 7.0 software to establish a numerical model of bedded coal, as shown in Figure 1. In the model, the coal matrix is represented in blue, while the red horizontal thin lines indicate the bedding planes. The test model consists of two parts: the coal sample and the shear box. The coal model has a height of 100 mm and a width of 200 mm. The outer shear box is composed of wall elements. The lower part of the shear box remains fixed, while the upper part can be subjected to shear and normal stresses. The loading scheme applies normal stresses of 1, 2, 3, and 4 MPa, with a shear velocity of 0.2 mm/s. Instead of using servo-controlled normal stress, constant normal stresses of 1–4 MPa were applied to the model. During the shear process, dilation may cause minor fluctuations in normal stress due to specimen expansion, but these fluctuations are minimal compared to the continually increasing shear stress. As a result, the impact of these fluctuations on the shear stress–displacement behavior is negligible, and the overall reliability of the results remains unaffected by the lack of servo control.

Figure 1.

Numerical model of direct shear of layered coal.

Since the PFC2D model with different bedding angles developed by Ou [23] has demonstrated good applicability, this study adopts the same micromechanical parameters as those in Ref. [23], as listed in Table 1. The particle radius in the coal model is set to 0.3–0.5 mm, with a total of 32,728 particles. The global damping coefficient is set to 0.1, and the particle size follows a uniform distribution. The particle density is 1400 kg·m−3.

Table 1.

Microscopic mechanical parameters of coal [23].

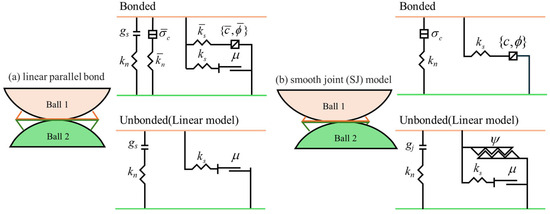

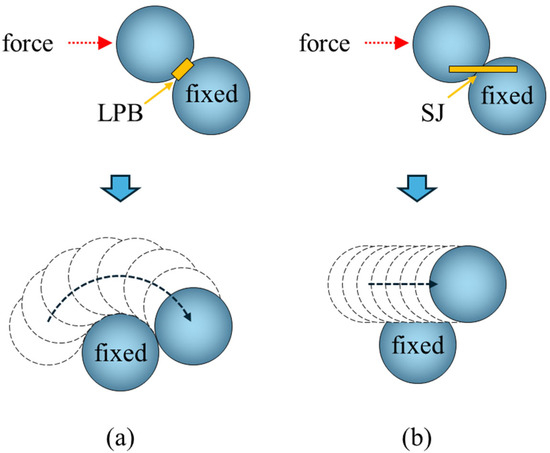

In PFC2d, particles are rigid and can move and rotate relative to one another. By bonding particles together and assigning specific mechanical parameters, a complete numerical rock model is obtained. However, there are significant differences in mechanical parameters between the coal matrix and bedding plane. To accurately reflect the characteristics of the coal matrix and bedding plane, the parallel bonding model linear parallel bond (LPB) [24] is used for coal matrix particles, and the smooth joint model smooth joint (SJ) [25] is used for bedding matrix particles. The constitutive model of LPB is shown in Figure 2a. The LPB model provides friction interfaces capable of withstanding forces and interfaces capable of withstanding both forces and torques. As shown in Figure 3a, when the LPB model fractures under shear stress, particle 1 moves around particle 2. The constitutive model of SJ is shown in Figure 2b, where the simulated plane provides linear elastic and expansive bonding or friction interfaces. The SJ model simulates the behavior of planar interfaces. When the SJ model fractures under shear, as shown in Figure 3b, particles can move along the relevant joint plane. The relevant parameter settings for the contact model are shown in Table 1. To prevent abnormal damage to the model boundaries during loading, which could affect the test results, the bonding strength between particles and boundaries was set to 10 times the normal strength.

Figure 2.

Behavior and rheological components of (a) LPB and (b) SJ contacts.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of contact models (a) LPB model (b) SJ model (adapted from Hu [26]).

3. Simulation Results and Analysis

3.1. Shear Stress-Displacement Characteristics

During the calculation process, the shear stress (τ) was determined by dividing the applied shear force (F) by the effective shear area of the model. The effective shear area was computed by considering the contact area between particles within the shear zone. For simplicity, we assumed a specimen thickness of 1 unit, which allowed the conversion of the calculated internal forces into shear stresses in “MPa”.

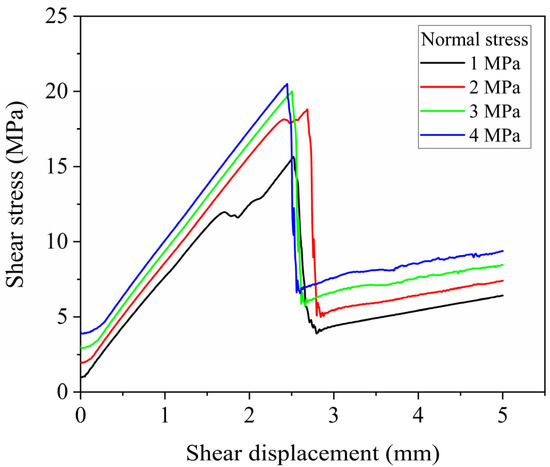

Figure 4 shows the shear stress versus shear displacement curves of the model specimen under normal stresses of 1, 2, 3, and 4 MPa, representing the direct shear test results under different normal stress levels. From Figure 4, it can be observed that the curves exhibit similar characteristics under different normal stresses, divided into three stages: elastic ascent, strain softening, and residual stability. In the initial loading phase, which corresponds to the shear displacement range of 1–2.5 mm, all curves display a linear elastic response, with shear stress increasing approximately linearly with shear displacement. Notably, as the normal stress increases, the peak shear strength shows a significant enhancement. It is well known from Equation (1) that shear strength increases approximately linearly with normal stress. Here, this relation is mentioned only to qualitatively illustrate the proportional trend between τ and σ.

Figure 4.

Relationship between shear stress and shear displacement under different normal stresses.

After reaching the peak shear stress, the coal undergoes brittle fracture, and the shear stress drops sharply. After the fracture, within a lower shear displacement range, the shear stress exhibits temporary fluctuations, which may be related to the sliding of bedding planes. As shear displacement continues to increase, the coal enters the residual shear stage, where shear stress tends to stabilize and remains influenced by normal stress. The relatively high residual shear-to-normal stress ratios (τr/σ) observed in our simulations can be attributed to the combined effects of high interparticle friction, rolling resistance, pronounced interlocking along bedding planes, and the reduction in effective shear area due to dilation. These factors together result in τr/σ ratios slightly greater than 1, which is reasonable for rough and anisotropic bedded coals.

3.2. Shear Strength Characteristics

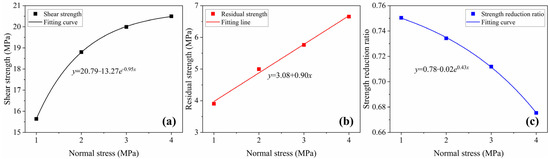

For a deeper analysis of the shear mechanical properties of coal, Figure 5 presents the peak strength, residual strength, and strength reduction ratio derived from Figure 4. The strength reduction ratio is defined as (peak strength minus residual strength) divided by peak strength. Figure 5a shows that the shear strength increases nonlinearly with normal stress, following the fitted equation y = 20.79 − 13.27exp(−0.95x). As the normal stresses increase, the growth rate slows. The growth rate is represented by the derivative of the function y = 20.79 − 13.27 exp(−0.95x), which is 12.6065 exp(−0.95x). This indicates that, at higher normal stresses, the growth rate decreases over time. Figure 5b reveals a strong linear relationship between the residual strength and normal stress, indicating that the frictional resistance along the shear surface remains strongly governed by the normal stress after failure. The fitted relationship is y = 3.08 + 0.90x. This demonstrates that normal stress has a significant influence on the residual strength, highlighting its dominant role in controlling the frictional behavior in the post-failure stage. In Figure 5c, the strength reduction ratio decreases with increasing normal stress. The fitted relationship is y = 0.78 − 0.02e0.43x. This suggests that under high normal stress, coal experiences relatively smaller strength loss after reaching peak strength. This phenomenon may result from the suppression of crack propagation by high normal stress and enhanced interlocking effects along the shear surface, allowing the material to maintain higher load-bearing capacity post-failure and exhibit either ductile behavior or reduced brittleness. Normal stress plays a significant regulatory role in the peak strength, residual strength, and brittle characteristics of bedded coal.

Figure 5.

Patterns of mechanical properties of layered coal with changes in normal stress: (a) shear strength, (b) residual strength, and (c) strength reduction rate.

3.3. Macroscopic and Microscopic Fracture Modes

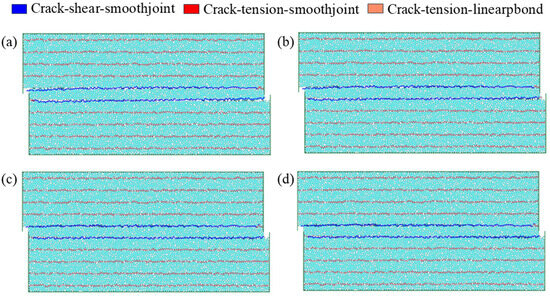

Figure 6 shows the crack propagation paths in bedded coal after shear tests under different normal stresses. The results demonstrate that under all normal stress conditions, the failure mode is dominated by shear failure along bedding planes (blue smooth-joint shear cracks). Cracks primarily propagate along the pre-existing weak bedding planes, forming a distinct and roughly parallel shear band. Although increased normal stress significantly enhances the shear strength of coal (as concluded in Section 3.2), it has little influence on the path and pattern of major shear cracks. The cracks consistently tend to follow the weakest bedding planes for shear sliding. The absence of red (smooth-joint tensile cracks) or orange (linear-contact tensile cracks) in the images indicates that within the tested normal stress range, failure occurs mainly through shear. The failure pattern is predominantly controlled by the inherent anisotropy of the bedding structure. This observation highlights the dominant role of bedding structure in governing coal’s failure behavior. Even under varying stress levels, this structural anisotropy determines both the location and propagation path of shear bands.

Figure 6.

Failure modes of layered coal under different normal stresses (a) normal stress 1 MPa (b) normal stress 2 MPa (c) normal stress 3 MPa (d) normal stress 4 MPa.

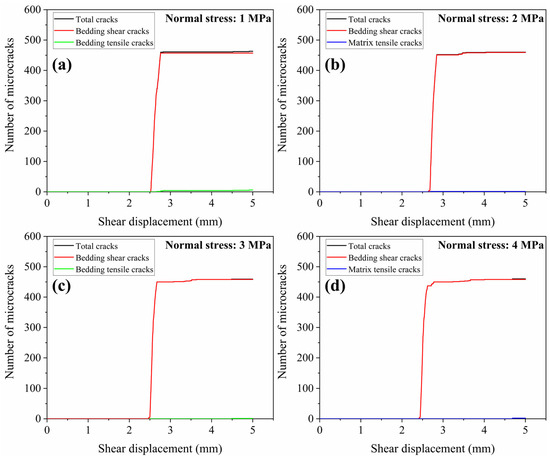

Figure 7 presents the evolution of microcrack counts with shear displacement. The results clearly show that under all normal stress conditions, crack initiation exhibits significant hysteresis. Microcrack counts remain nearly zero until shear displacement reaches a certain threshold, corresponding to the elastic phase of the material described in Section 3.1. Once this threshold is exceeded, the number of shear cracks along bedding planes (red curve) increases sharply, forming a steep rising segment that marks the rapid development of macroscopic shear failure. Regardless of normal stress magnitude, bedding-plane shear cracks consistently dominate the failure mode, significantly outnumbering other crack types. The near absence of tensile cracks (green curve) or matrix tensile cracks (blue curve) further confirms that shear-dominated failure characterizes the bedded coal under these loading conditions, with negligible contribution from tensile failure. While normal stress substantially affects shear strength and the stress level required for failure, its influence on post-failure microdamage accumulation within the shear band appears relatively limited. The formation of macroscopic shear surfaces is primarily governed by the inherent characteristics of the bedding structure.

Figure 7.

Evolution of crack number in layered coal under shear stress as a function of normal stress (a) normal stress 1 MPa (b) normal stress 2 MPa (c) normal stress 3 MPa (d) normal stress 4 MPa.

3.4. Characteristics of Force Chain

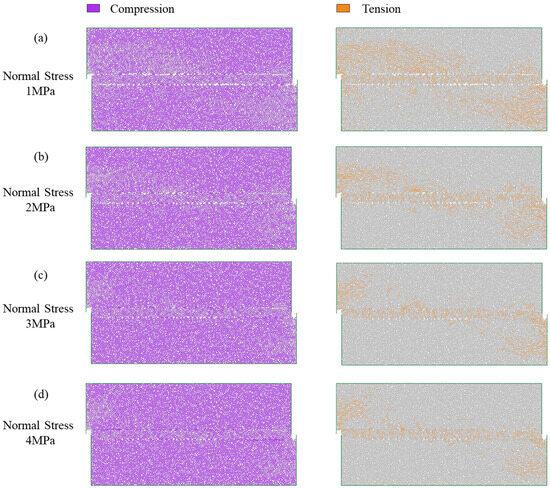

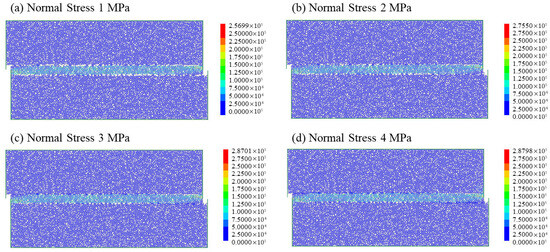

Figure 8 presents the force chain distribution after specimen shear failure, revealing the evolution of micromechanical behavior in bedded coal under different normal stresses, particularly the development of compressive and tensile force chains. The compressive force chain diagrams (left) demonstrate that increasing normal stress significantly enhances both the density and connectivity of compressive force chains along the predefined shear band (horizontal bedding interface). This forms a more continuous and stable skeletal structure, indicating that higher normal stress effectively strengthens interparticle contact forces and interlocking effects. Consequently, the material develops a denser and more efficient compressive force network to transfer external loads, substantially improving shear resistance. In contrast, the tensile force chain diagrams (right) show a different trend. Under lower normal stresses, tensile force chains appear relatively dispersed near the shear band, reflecting localized tensile stresses from particle rotation, sliding, or separation during shearing. However, with increasing normal stress, tensile force chains become more localized and sparse, particularly within the shear band, suggesting effective suppression of their development. These tensile chains mainly concentrate in localized stress concentration zones (e.g., specimen edges or crack tips). These observations confirm that high normal stress effectively restrains both the dilatancy behavior and potential tensile microcrack propagation in granular materials during shearing—phenomena that typically precede macroscopic shear failure.

Figure 8.

Effect of normal stress on the distribution and evolution of the force chain in bedded coal (a) normal stress 1 MPa (b) normal stress 2 MPa (c) normal stress 3 MPa (d) normal stress 4 MPa.

Figure 9 shows the contact force magnitude (contact_force_mag) distribution. The results demonstrate that under all normal stress conditions, the maximum force chains consistently concentrate along the predefined horizontal bedding interface (shear band) in the specimen’s central region. Surrounding particles bear negligible contact forces, clearly indicating this bedding plane serves as the structural weak surface where primary shear deformation and mechanical responses occur. As normal stress increases from 1 MPa (Figure 9a) to 2 MPa (Figure 9b) and 3 MPa (Figure 9c,d), the force chain colors within the shear band progressively shift from light blue/green to yellow/orange and even red. This color evolution directly reflects significant enhancement in both average and maximum interparticle contact forces. The observations confirm that higher normal stress strengthens normal contacts between particles, thereby improving interlocking and frictional effects. Consequently, the shear band develops denser and higher-strength force chain networks capable of transmitting greater shear stresses. Notably, Figure 9c,d exhibit similar force chain distributions and intensities, suggesting the force chain network reaches a relatively stable, high-strength transmission state under sufficient normal stress. This may indicate the system attains a stable load-bearing configuration after certain shear deformation.

Figure 9.

Contact force magnitude (a) Normal stress 1 MPa (b) Normal stress 2 MPa (c) Normal stress 3 MPa (d) Normal stress 4 MPa.

4. Conclusions

This study employs PFC2D7.0 numerical simulations to investigate the shear mechanical behavior and micro-mechanisms of bedded coal under different normal stresses (1\2\3\4 MPa), providing important theoretical insights for understanding fault-slip type rock bursts in deep coal mining. The results of the study indicate that:

(1) The shear stress-displacement curves exhibit three characteristic stages: elastic ascent, strain softening, and residual stabilization. Both peak and residual shear strengths increase significantly with normal stress, though peak strength shows nonlinear growth while residual strength maintains a linear relationship. Notably, the strength reduction ratio decreases with increasing normal stress, indicating that high normal stress effectively suppresses brittle characteristics and helps maintain post-failure load-bearing capacity.

(2) The failure analysis shows that shear failure consistently occurs along the bedding planes under all normal stress conditions. Cracks primarily propagate along these predefined weak bedding planes, forming distinct shear bands, which highlights the significant role of bedding structure in controlling the failure process. Additionally, crack evolution analysis confirms that shear cracks along bedding planes are the dominant damage mechanism, with minimal contribution from tensile cracks. Furthermore, crack initiation exhibits clear hysteresis, providing additional insight into the failure behavior.

(3) Force chain analysis at the particle scale reveals the underlying mechanisms. Increasing normal stress enhances compressive force chain density and connectivity within shear bands, forming more stable skeletal structures that effectively transfer loads and improve shear strength. Meanwhile, tensile force chains become suppressed and localized under high normal stress, demonstrating effective restraint of dilatancy behavior and potential tensile microcrack propagation. The force chain distribution further emphasizes bedding planes as structural weak zones that concentrate mechanical responses, though their contact force intensity increases significantly with normal stress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.F. and J.O.; resources, J.O.; software, X.F.; writing—original draft preparation, X.F.; writing—review and editing, J.O., Y.T., X.H. and B.W.; funding acquisition, J.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2024YFC3015805).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xinchuan Fan was employed by the company China Pingmei ShenMa Group. Author Yanjun Tong was employed by the company Pingdingshan Tian’an Coal Mining Co., Ltd. Author Xiaojun He was employed by the company Fangshan Xinjing of Pingyu Coal and Electricity Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The companies had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Gao, M.; Xie, J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, C.; Yang, B.; Liu, J.; Xie, H. Mechanical Behavior of Coal under Different Mining Rates: A Case Study from Laboratory Experiments to Field testing Mechanical Behavior of Coal under Different Mining Rates: A Case Study from Laboratory Experiments to Field Testing. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2021, 31, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, M.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, D.; Hu, J.; Cheng, T. Granite Strain bursts Induced by True Triaxial Transient Unloading at Different Stress Levels: Insights from Excess Energy ΔE. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, M.; Qiao, Y.; Cheng, T.; Han, Z. Assessing Burst Proneness and Seismogenic Process of Anisotropic Coal Via the Realistic Energy Release Rate (RERR) Index. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 2999–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; He, M.; Li, H.; Cheng, T.; Tao, Z.; Liu, D.; Peng, D. Control Effect of Negative Poisson’s Ratio (NPR) Cable on Impact-Induced Rockburst with Different Strain Rates: An Experimental Investigation. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 5167–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Wu, K.; Wang, Q.; Kang, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, C. Development of Physical Model Test System for Fault-Slip Induced Rockburst in Underground Coal mining Development of Physical Model Test System for Fault-Slip Induced Rockburst in Underground Coal Mining. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 2227–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; He, M.; Li, H.; Tao, Z.; Liu, D.; Cheng, T.; Peng, D. Rockburst Hazard Control Using the Excavation Compensation Method (ECM): A Case Study in the Qinling Water Conveyance Tunnel. Engineering 2024, 34, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pan, Y.; Hai, L. Instability Criterion of Fault Rockburst Based on Gradient-Dependent Plasticity. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2004, 23, 588–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Zhang, C.; Canbulat, I.; Huang, W. Numerical Investigation into Impacts of Major Fault on Coal Burst in Longwall Mining—A Case study Numerical Investigation into Impacts of Major Fault on Coal Burst in Longwall Mining—A Case Study. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2021, 147, 104907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.Y.; Dang, W.G.; Bai, Z.C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, P.T.; Yang, Z. Mechanical Responses and Fracturing Behaviors of Coal under Complex Normal and Shear Stresses, Part I: Experimental Results. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Mao, X.; Pu, H.; Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W. Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties and Microcrack Fracture of Coal Specimens under the Coupling of Loading Rate and Compression–Shear Loads. Int. J. Geomech. 2022, 22, 04022028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, C. Microcrack Fracturing of Coal Specimens under Quasi-Static Combined Compression-Shear Loading. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2020, 12, 1014–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Yao, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ju, M. Experimental Study of Shear Failure and Crack Propagation in Water-Bearing Coal Samples. Energy Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 2193–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wan, L.; Zuo, J. Non-Linear Shear Strength Model for Coal Rocks. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 4123–4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Jiang, C.; Guo, X.; Yang, K.; Tang, J.; Yin, Z.; Hu, X. Experimental Study on Mechanics and Seepage of Coal under Different Bedding Angle and True Triaxial Stress State. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, J.; Su, B. The Effect of Bedding on Deformation Localization and Damage Constitutive Modeling in Coal Specimens. Mech. Time-Depend. Mater. 2024, 28, 3139–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, J.; Huang, X.; Yu, B.; Nie, Z.; Yang, D. Low Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Experimental Study on Gas Adsorption of High-Rank Coals with Different Beddings. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 18752–18760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortezaei, R.; Mohammadi, S.D.; Sarfarazi, V.; Moayedi Far, A. Investigation of Shear Behavior of Notched Bedding Rock Containing Welded Interface between Hard and Soft Layers; an Acoustic Emission-Based Approach. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2023, 127, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, B.; Li, C.; Wu, B.; Wang, J. Research on Anisotropic Characteristics and Energy Damage Evolution Mechanism of Bedding Coal under Uniaxial Compression. Energy 2024, 301, 131659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhao, H.; Liu, H. Mechanical Response Mechanism and Seepage Characteristics of Gas-Bearing Bedding Coal under Impact Loading. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 326, 111425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Ren, T.; Yang, X.; He, X. A Numerical Simulation Study on Mechanical Behaviour of Coal with Bedding Planes under Coupled Static and Dynamic Load. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yin, G.; Li, M.; Shang, D.; Deng, B.; Song, Z. Deformation and Permeability Evolution of Coals Considering the Effect of Beddings. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2019, 117, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Gao, F.; Zheng, W.; Su, S.; Li, P.; Sang, S.; Gao, X.; Hou, P.; Wang, S. Cracking Patterns and Damage Evolution Characteristics of Coal with Bedding Structures under Liquid Nitrogen Cooling. Nat. Resour. Res. 2024, 33, 2193–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Niu, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, J.; Lyu, B.; Zhan, B.; Ma, Y. Numerical Simulation of Coal’s Mechanical Properties and Fracture Process under Uniaxial Compression: Dual Effects of Bedding Angle and Loading Rate. Processes 2024, 12, 2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Zhai, C.; Yu, X.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Cong, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y. Dynamic Brazilian Splitting Experiment of Bedding Shale Based on Continuum-Discrete Coupled method Dynamic Brazilian Splitting Experiment of Bedding Shale Based on Continuum-Discrete Coupled Method. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2022, 168, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Kwok, C.Y.; Duan, K.; Wang, T. Parametric Study of the Smooth-Joint Contact Model on the Mechanical Behavior of Jointed Rock. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2018, 42, 358–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Gutierrez, M.; Yan, Z. Heterogeneities of Grain Boundary Contact for Simulation of Laboratory-Scale Mechanical Behavior of Granitic rocks Heterogeneities of Grain Boundary Contact for Simulation of Laboratory-Scale Mechanical Behavior of Granitic Rocks. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 16, 2629–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).