Femtosecond Laser Filament-Induced Discharge at Gas–Liquid Interface and Online Measurement of Its Spectrum

Abstract

1. Introduction

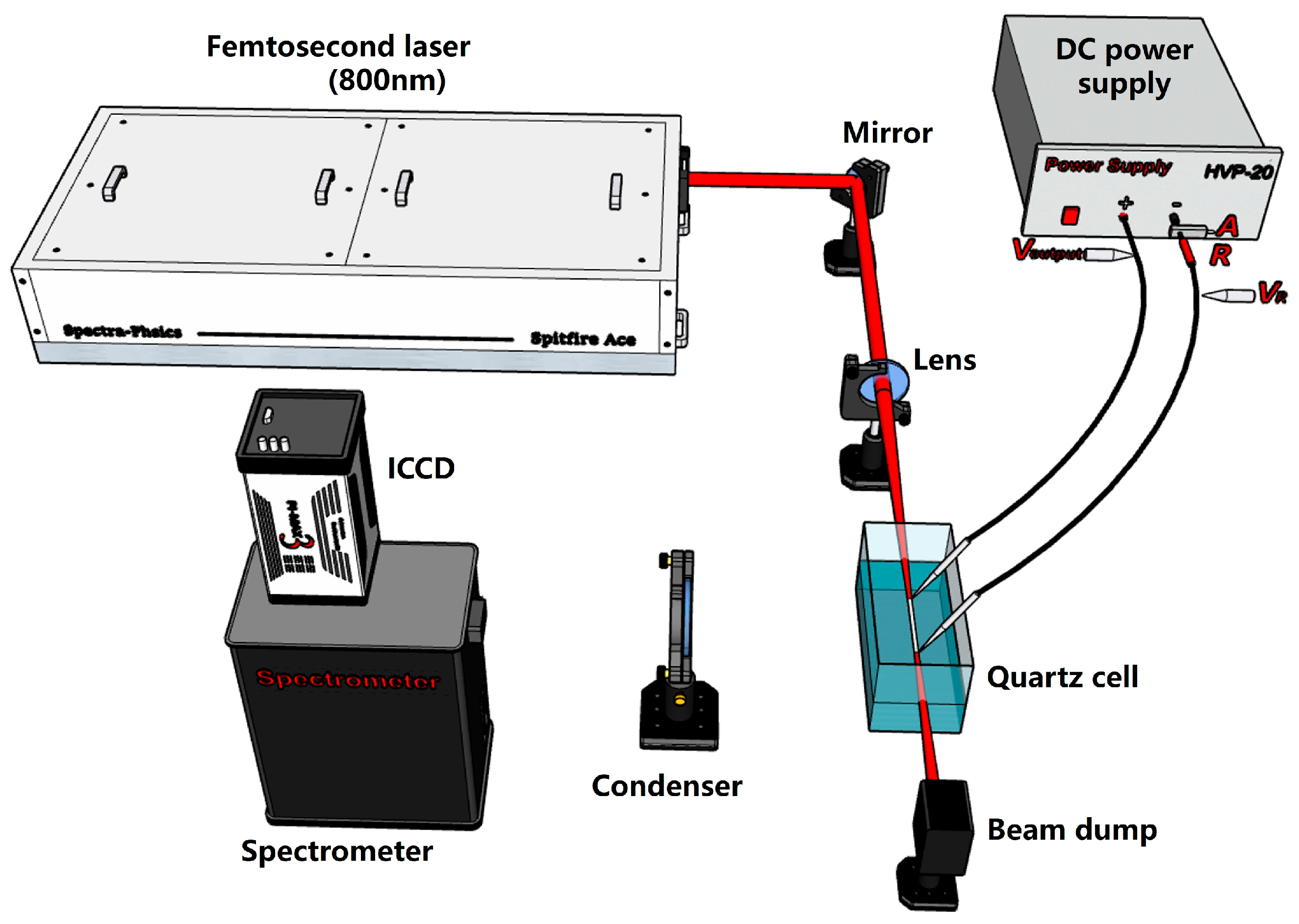

2. Experimental

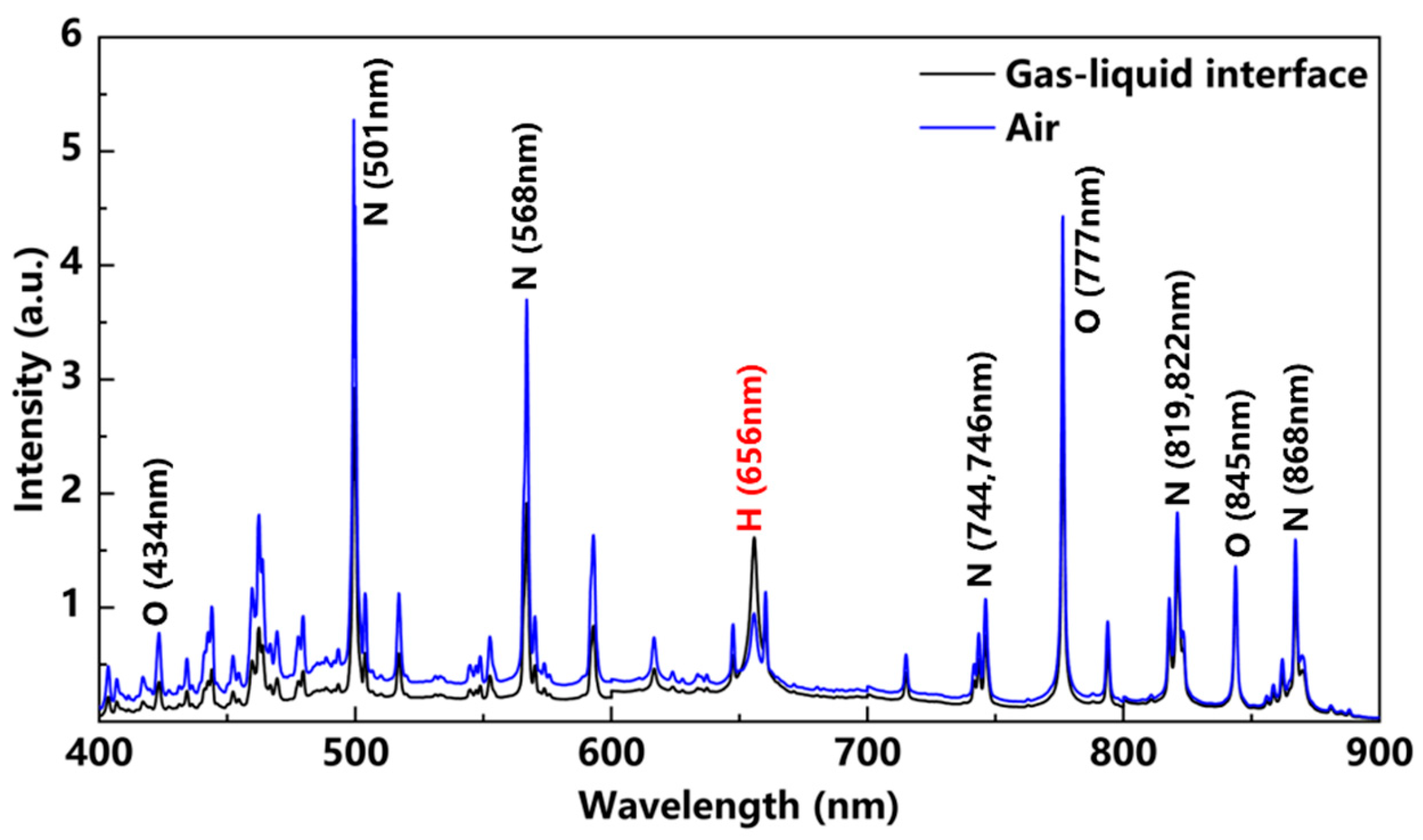

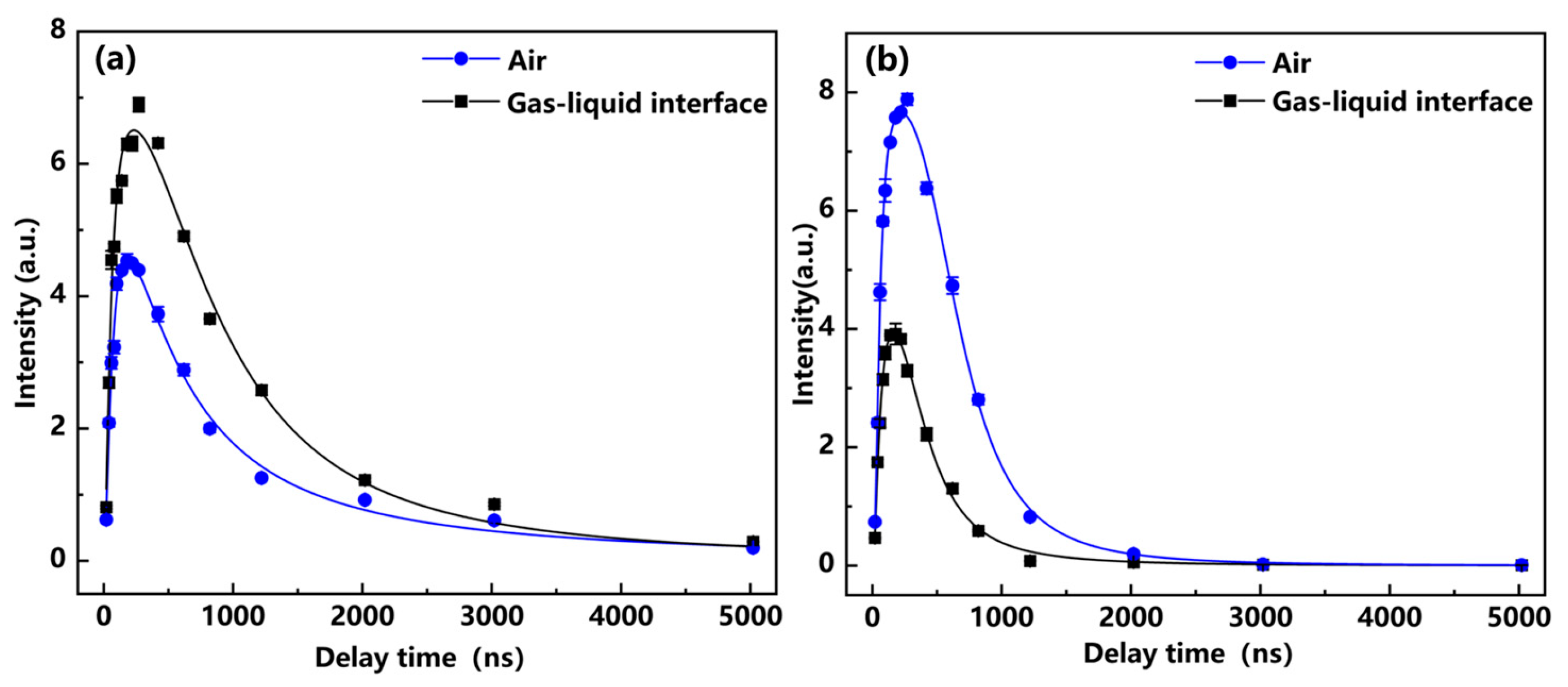

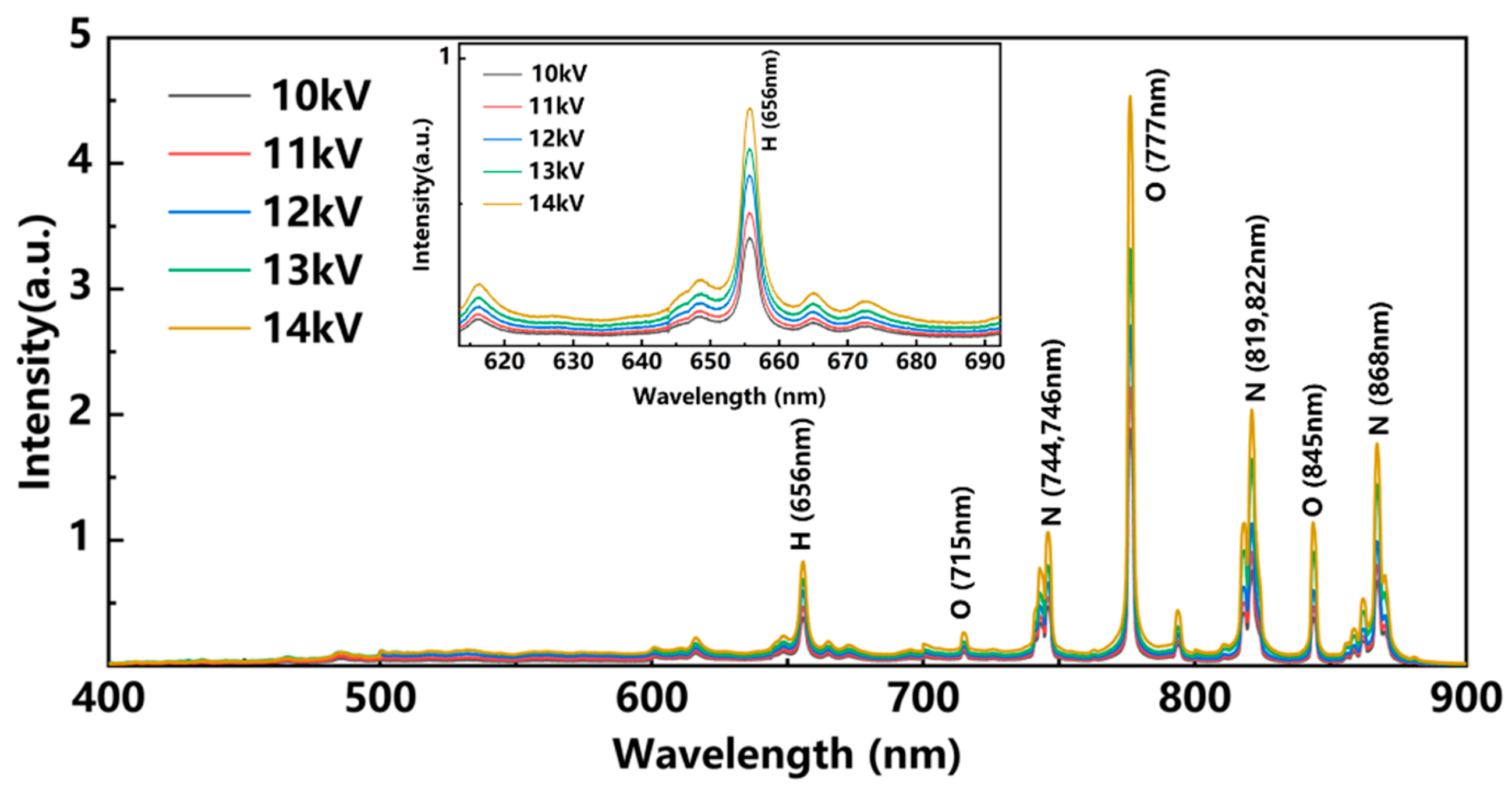

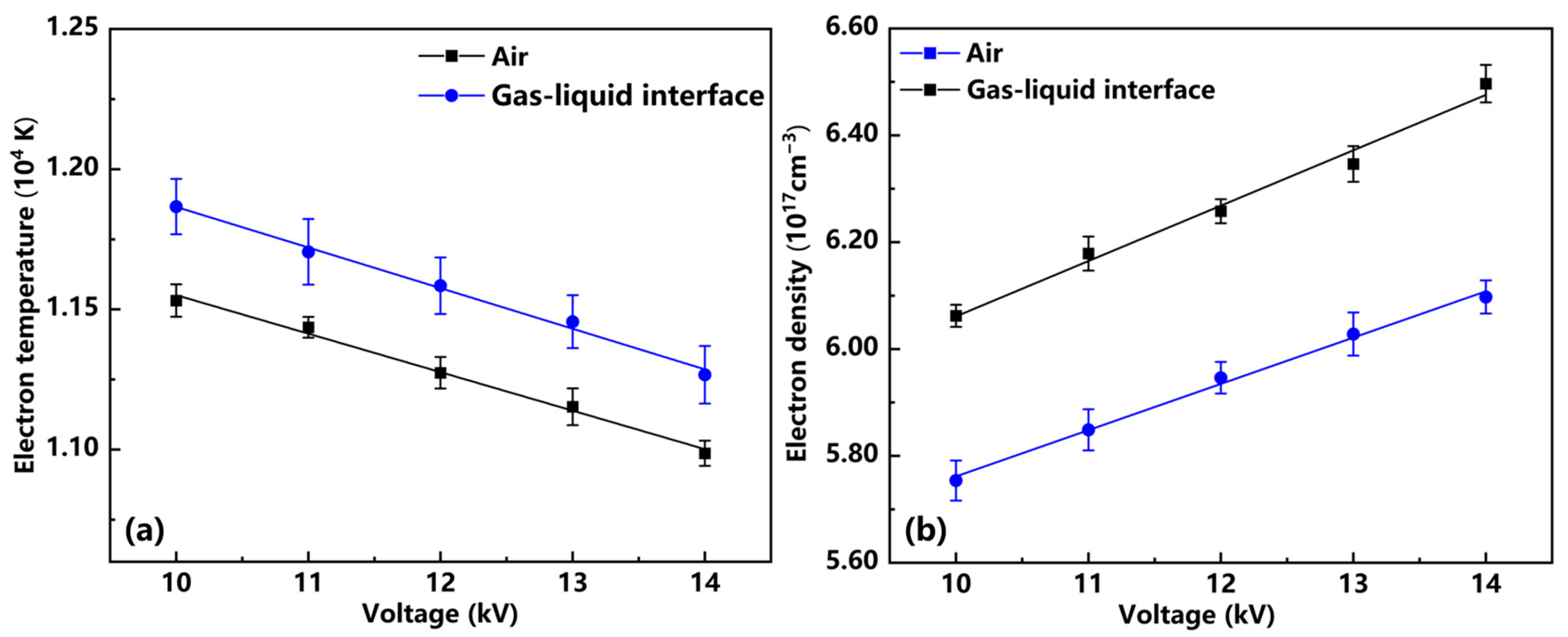

3. Results and Discussion

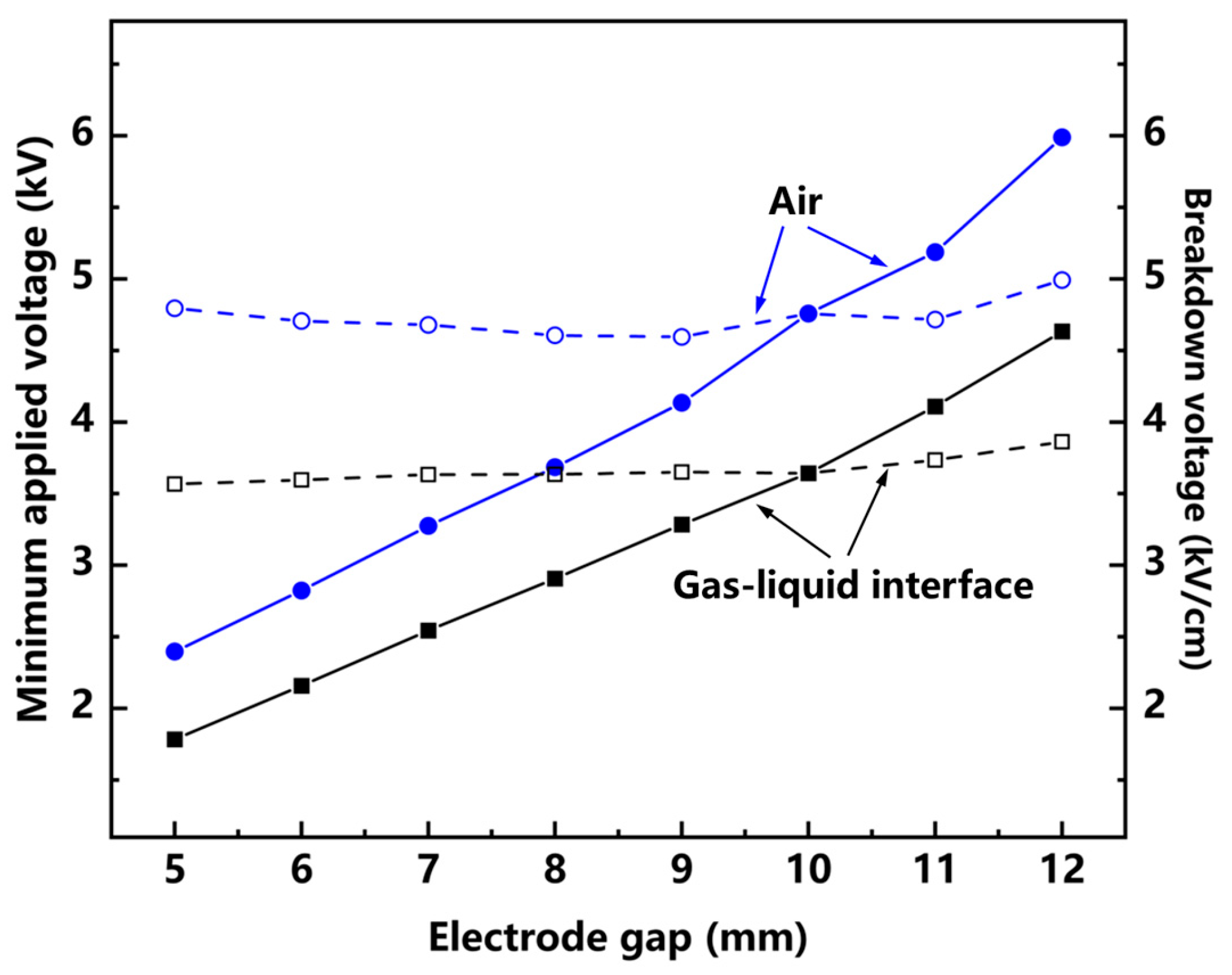

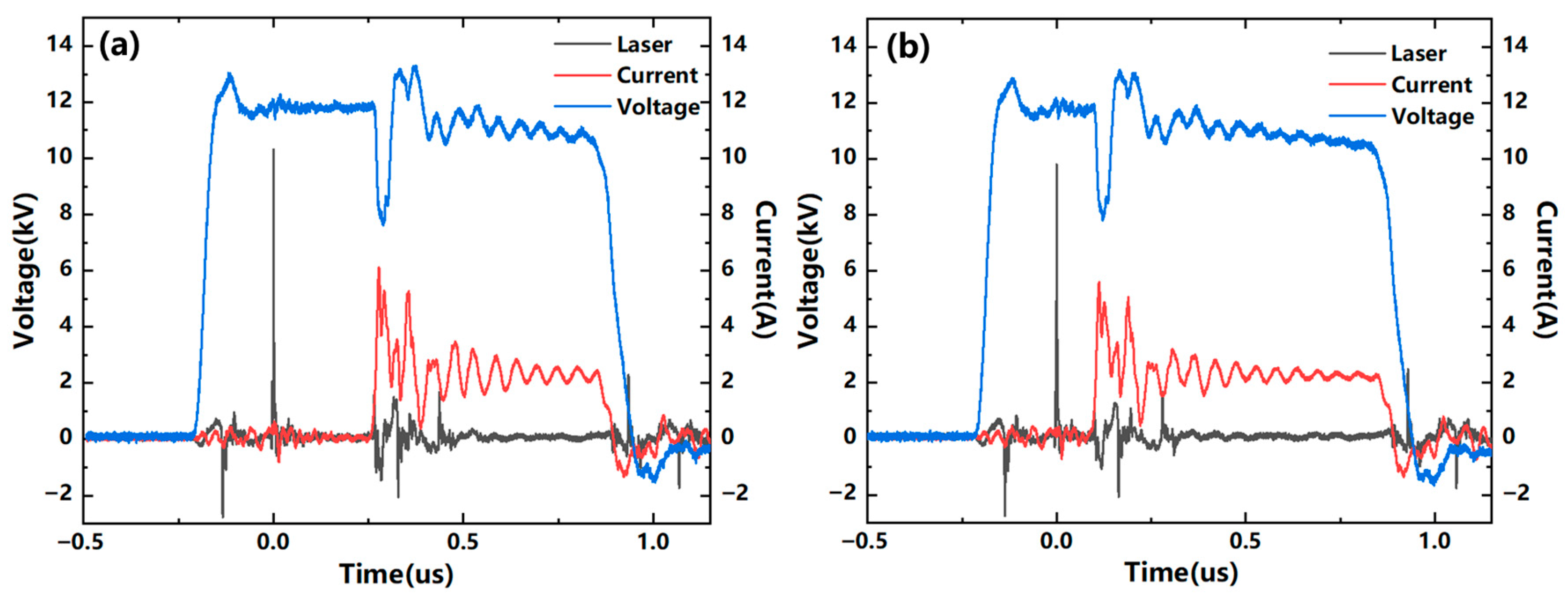

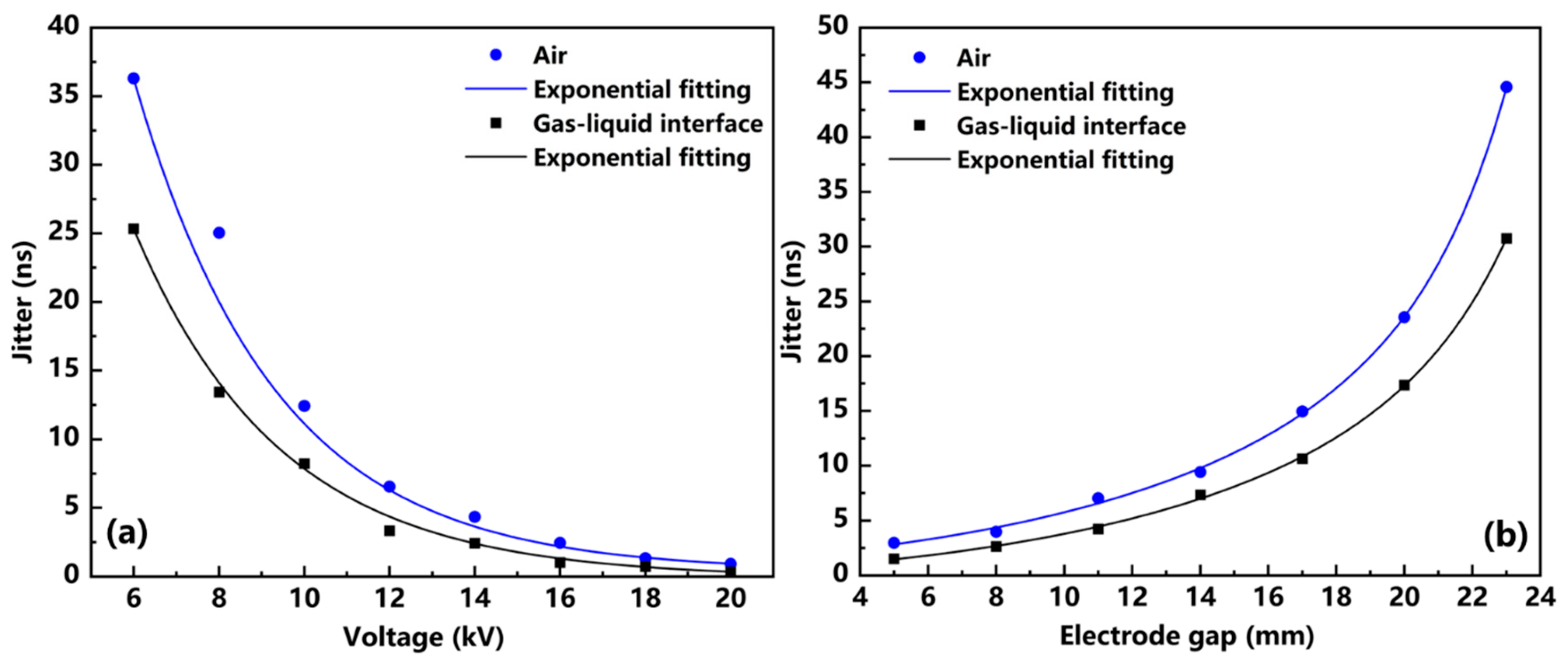

3.1. Study of Discharge Control

3.2. Study of Spectral Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, Y.T.; Zhou, R.W.; Hong, L.F.; Chen, B.H.; Sun, J.; Zhou, R.S.; Liu, Z.J. Efficient synthesis of CO and H2O2 via nanosecond pulsed CO2 bubble discharge. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2024, 57, 375204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Wada, Y.; Xu, K.J.; Onoe, K.; Hiaki, T. Enhanced generation of active oxygen species induced by O3 fine bubble formation and its application to organic compound degradation. Environ. Technol. 2022, 43, 3661–3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.H.; Dai, S.L.; Li, X.D.; Tu, X.; Liu, Y.N.; Cen, K.F. Emission spectroscopy diagnosis of the radicals generated in gas-liquid phases gliding arc discharge. Spectrosc. Spect. Anal. 2008, 28, 1851–1855. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, Z.L.; Cheng, C.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Z.M.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, W.D.; Chu, P.K. Characteristics of DC gas-liquid phase atmospheric-pressure plasma and bacteria inactivation mechanism. Plasma Process. Polym. 2015, 12, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakov, V.S.; Kiris, V.V.; Nevar, A.A.; Nedelko, M.I.; Tarasenko, N.V. Combined gas-liquid plasma source for nanoparticle synthesis. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 2016, 83, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wei, Z.P.; Quan, L.; Hu, Y.W.; Qiao, M.T.; Shao, M.X.; Xie, K. Controlled plasma-droplet interactions: Two-phase flow millifluidic system. Phys. Plasmas 2025, 32, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Chang, D.L.; Liang, J.P.; Lu, K.; Cui, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, D.Z. Ammonia nitrogen removal by gas-liquid discharge plasma: Investigating the voltage effect and plasma action mechanisms. Water 2023, 15, 3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggeman, P.J.; Frontiera, R.R.; Kortshagen, U.; Kushner, M.J.; Linic, S.; Schatz, G.C.; Andaraarachchi, H.; Chaudhuri, S.; Chen, H.T.; Clay, C.D.; et al. Advances in plasma-driven solution electrochemistry. J. Chem. Phys. 2025, 162, 070901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; He, Z.H.; Gao, Z.W.; Tan, F.L.; Yue, X.G.; Chang, J.S. Research on the influence of conductivity to pulsed arc electrohydraulic discharge in water. J. Electrostat. 2014, 72, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelmashuk, V.; Prukner, V.; Kolacek, K.; Tuholukov, A.; Hoffer, P.; Straus, J.; Frolov, O.; Jirasek, V. Optical emission spectroscopy of underwater spark generated by pulse high-voltage discharge with gas bubble assistant. Processes 2022, 10, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeva, N.Y.; Berry, R.S.; Naidis, G.V.; Smirnov, B.M.; Son, E.E.; Tereshonok, D.V. Kinetic and electrical phenomena in gas-liquid systems. High Temp. 2016, 54, 745–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorval, A.; Stafford, L.; Hamdan, A. Spark discharges at the interface of water and heptane: Emulsification and effect on discharge probability. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2024, 57, 015203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.W.; Gao, Y.X.; Naitoc, T.; Oinumac, G.; Inanagac, Y.; Yang, M. Rapid removal of polyacrylamide from wastewater by plasma in the gas-liquid interface. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 83, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, K.B. Degradation of microcystin-LR by gas-liquid interfacial discharge plasma. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2013, 15, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arantchouk, L.; Honnorat, B.; Thouin, E.; Point, G.; Mysyrowicz, A.; Houard, A. Prolongation of the lifetime of guided discharges triggered in atmospheric air by femtosecond laser filaments up to 130 μs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 171103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksson, M.; Daigle, J.F.; Théberge, F.; Châteauneuf, M.; Dubois, J. Laser guiding of Tesla coil high voltage discharges. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 12721–12728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lu, X.; Hao, Z.Q.; Zhang, S.C.; Zhang, D.D.; Wang, Z.H.; Ma, Y.Y.; Yan, P.; Zhang, J. Laboratory simulation of femtosecond laser guided lightning discharge. Acta Phys. Sin. 2007, 56, 5293–5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lu, X.; Liang, W.X.; Hao, Z.Q.; Zhou, M.L.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhang, J. Triggering and guiding of high voltage discharge by using femtosecond laser filaments with different parameters. Chin. Phys. B 2009, 18, 1136–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Gu, J.P.; Zhang, D.Y.; Gao, Q.; Li, B. Equivalence ratio measurements in CH4/Air gases based on the spatial distribution of the emission intensity of femtosecond laser-induced filament. Processes 2021, 9, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergé, L.; Skupin, S.; Nuter, R.; Kasparian, J.; Wolf, J.P. Ultrashort filaments of light in weakly ionized, optically transparent media. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2007, 70, 1633–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, M.; Skrodzki, P.J.; Nees, J.; Jovanovic, I. Electrical conductance of near-infrared femtosecond air filaments in the multi-filament regime. Opt. Lett. 2018, 43, 5520–5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionin, A.A.; Seleznev, L.V.; Sunchugasheva, E.S. Formation of plasma channels in air under filamentation of focused ultrashort laser pulses. Laser Phys. 2015, 25, 035301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosareva, O.G.; Mokrousova, D.V.; Panov, N.A.; Nikolaeva, I.A.; Shipilo, D.E.; Mitina, E.V.; Koribut, A.V.; Rizaev, G.E.; Couairon, A.; Houard, A.; et al. Remote triggering of air-gap discharge by a femtosecond laser filament and postfilament at distances up to 80 m. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 119, 041101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, S.B.; Firsov, A.A.; Shurupov, M.A.; Michael, J.B.; Shneider, M.N.; Miles, R.B.; Popov, N.A. Femtosecond laser guiding of a high-voltage discharge and the restoration of dielectric strength in air and nitrogen. Phys. Plasmas 2012, 19, 123505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zhu, Z.F.; Li, B.; Han, L.; Li, Z.S. Spatiotemporally resolved spectra of gaseous discharge between electrodes triggered by femtosecond laser filamentation. Appl. Phys. B Lasers Opt. 2022, 128, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Li, B.; Feng, Z.Y.; Gao, Q. One-dimensional measurement of metal elements in aerosols based on femtosecond laser-extended electrode discharge spectroscopy (FEEDS) technique. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2025, 27, 085501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.F.; Li, B.; Gao, Q.; Zhu, J.J.; Li, Z.S. Spatiotemporal control of femtosecond laser filament-triggered discharge and its application in diagnosing gas flow fields. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2022, 24, 025401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.Y.; Han, L.; Gao, Q.; Liu, Z.H.; Li, B. One-dimensional temperature measurement of gases based on femtosecond laser-extended electrode discharge spectroscopy (FEEDS). Opt. Laser Eng. 2024, 178, 108209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahoon, E.M.; Almirall, J.R. Quantitative analysis of liquids from aerosols and microdrops using laser induced breakdown spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 2239–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tang, M.; Zhang, H.C.; Lu, J. Optical breakdown during femtosecond laser propagation in water cloud. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 8456–8475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Y.; Guo, L.B.; Li, J.M.; Yi, R.X.; Hao, Z.Q.; Shen, M.; Zhou, R.; Li, K.H.; Li, X.Y.; Lu, Y.F.; et al. Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy of liquid solutions: A comparative study on the forms of liquid surface and liquid aerosol. Appl. Opt. 2016, 55, 7406–7411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Wang, W.C.; Wang, S.; Ren, C.S.; Wang, Y.N. The study of active atoms in high-voltage pulsed coronal discharge by optical diagnostics. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2005, 7, 2851–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarova, E.; Dias, F.M.; Ferreira, C.M. Hot hydrogen atoms in a water-vapor microwave plasma source. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 9585–9590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, J.A.; Bengoechea, J.; Aragón, C. Curves of growth of spectral lines emitted by a laser-induced plasma: Influence of the temporal evolution and spatial inhomogeneity of the plasma. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2003, 58, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Gragston, M.; Patnaik, A.K.; Hsu, P.S.; Shattan, M.B. Measurement of electron density and temperature from laser-induced nitrogen plasma at elevated pressure (1–6 bar). Opt. Express 2019, 27, 33780–33789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferioli, F.; Buckley, S.G. Measurements of hydrocarbons using laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Combust. Flame 2006, 144, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, R.S. Excited-state equilibration and the fluorescence-absorption ratio. Acta Phys. Pol. 1999, 95, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Bernhardt, J.; Theberge, F.; Châteauneuf, M.; Dubois, J. Spectroscopic characterization of femtosecond laser filament in argon gas. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 102, 033111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Z.; Li, B.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, T.; Zhang, L.; Jiao, H.; Gao, Q. Femtosecond Laser Filament-Induced Discharge at Gas–Liquid Interface and Online Measurement of Its Spectrum. Processes 2025, 13, 4003. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124003

Lu Z, Li B, Li X, Zhu Z, Wu T, Zhang L, Jiao H, Gao Q. Femtosecond Laser Filament-Induced Discharge at Gas–Liquid Interface and Online Measurement of Its Spectrum. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4003. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124003

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Zheng, Bo Li, Xiaofeng Li, Zhifeng Zhu, Tengfei Wu, Lei Zhang, Hujun Jiao, and Qiang Gao. 2025. "Femtosecond Laser Filament-Induced Discharge at Gas–Liquid Interface and Online Measurement of Its Spectrum" Processes 13, no. 12: 4003. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124003

APA StyleLu, Z., Li, B., Li, X., Zhu, Z., Wu, T., Zhang, L., Jiao, H., & Gao, Q. (2025). Femtosecond Laser Filament-Induced Discharge at Gas–Liquid Interface and Online Measurement of Its Spectrum. Processes, 13(12), 4003. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124003