Abstract

Spectroscopic techniques offer significant potential for investigating ligand–protein interactions, particularly for assessing conformational modifications and binding affinity. In the present study, a complementary approach combining near-UV circular dichroism (CD) and second-derivative fluorescence spectroscopy was applied to evaluate how two representative nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs—phenylbutazone (PHB, a marker of Sudlow’s site I) and ketoprofen (KP, a marker of Sudlow’s site II)—influence the tertiary structure of human serum albumin in its native form (HSA) and after glycation by glucose (gHSAGLC), fructose (gHSAFRC), and glucose–fructose syrup (gHSAsyrup). The results demonstrate that glycation substantially modifies the tertiary structure of HSA and decreases its drug-binding capacity at Sudlow’s sites I and II, with the most pronounced conformational changes observed for gHSAFRC, confirming fructose as the most reactive glycation agent. PHB induced distinct conformational rearrangements, including a characteristic increase in ellipticity near ~290 nm, indicating perturbations in the chiral microenvironment surrounding Trp214 within Sudlow’s site I. By contrast, KP induced weaker, site-specific structural changes, primarily within Phe-rich hydrophobic domains of site II. Glycation consistently increased the polarity and solvent exposure of aromatic residue microenvironments—particularly within Tyr-rich regions—while the local environment of Trp214 remained comparatively stable. These findings suggest that PHB and KP modulate the conformational flexibility of glycated HSA predominantly by reorganizing Tyr-rich regions rather than directly perturbing Trp214. Overall, the study shows that glycation heterogeneity significantly influences protein–drug interactions, with important implications for altered pharmacokinetics in diabetes and metabolic disorders. The combined application of near-UV CD and second-derivative fluorescence spectroscopy offers a sensitive and complementary strategy for distinguishing structural differences between non-glycated and glycated HSA and for characterizing drug–albumin interactions at the tertiary structural level of the macromolecule.

1. Introduction

Human serum albumin (HSA), the most abundant plasma protein, with a molecular mass of ~66.5 kDa, accounts for 55–60% of the total serum proteins [1]. It is synthesized exclusively in the liver at a rate of 12–25 g per day and is continuously secreted into the bloodstream [2]. HSA fulfills multiple essential physiological and pharmacological functions, making it an ideal candidate for clinical and biotechnological applications. These functions include (i) maintaining oncotic pressure and plasma pH, thereby regulating fluid distribution between the vascular and interstitial compartments [3], (ii) transporting a wide variety of endogenous (e.g., fatty acids, hormones) and exogenous (e.g., drugs, toxins) compounds via multiple specific binding sites [4,5], with ligand binding potentially influencing their bioavailability, distribution, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, (iii) exerting antioxidant activity, primarily through the single free thiol group of Cys34, which efficiently scavenges reactive oxygen and nitrogen species [6], and (iv) displaying enzymatic activities, including esterase- and peroxidase-like hydrolysis, which may contribute to drug metabolism and prodrug activation [7].

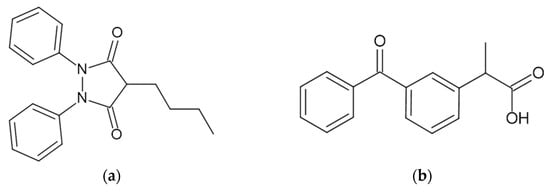

Structurally, HSA is a monomeric, non-glycosylated polypeptide composed of 585 amino acid residues, organized into three homologous α–helical domains (I–III), each further divided into subdomains A and B: domain I (residues 1–195; IA: 1–108, IB: 109–195), domain II (residues 196–383; IIA: 196–297, IIB: 298–383), and domain III (residues 384–585; IIIA: 384–502, IIIB: 503–585) [8]. Each domain generates a series of structurally flexible ligand-binding pockets that can accommodate a wide variety of endogenous and exogenous molecules [9,10]. The best-characterized high-affinity drug-binding regions on HSA are Sudlow’s site I, located in subdomain IIA, and Sudlow’s site II, in subdomain IIIA [11,12,13,14]. Site I is a large, hydrophobic cavity that partially overlaps with fatty acid binding site FA2 and preferentially accommodates bulky heteroaromatic anions [3]. Phenylbutazone (PHB), a model site I ligand (Figure 1a), inserts its n-butyl side chain deep into the hydrophobic core of the pocket, while its phenyl rings engage in extensive hydrophobic contacts with surrounding nonpolar residues, including Leu238, Ile264, and Leu260 [13]. PHB is further stabilized by hydrogen bonds between its carbonyl oxygen and Tyr150, as well as between its pyrazolidinedione ring and Arg257, resulting in an association constant in the range of ~105–106 L·mol−1 [3,13]. Crystallographic and spectroscopic studies indicate that strong hydrophobic interactions predominate in Sudlow’s site I, with additional stabilization from polar contacts and shape complementarity [14]. Sudlow’s site II is a smaller, elongated hydrophobic pocket overlapping fatty acid binding site FA4, which accommodates aromatic carboxylic acids such as ketoprofen (KP, Figure 1b) [14]. KP buries its aromatic rings deeply within the hydrophobic core, where they interact with residues such as Leu387 and Val433, and establishes hydrogen bonds with Tyr411 and Lys414. The binding affinity is typically in the order of ~105 L·mol−1 [15]. At Sudlow’s Site II, the dominant stabilizing forces are dipole–dipole interactions, van der Waals contacts, and hydrogen bonding, while hydrophobic effects contribute to ligand positioning and specificity [3,12,16]. In addition to these sites, HSA contains additional fatty acid binding pockets (FA1–FA9) distributed across all six subdomains [17,18], a high-affinity N-terminal metal-binding site for Cu2+ and Ni2+, a Cys34-proximal metal-binding site for Zn2+ and Cd2+ [19], and a heme-binding region in subdomain IB, often referred to as site III [14,20].

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of (a) phenylbutazone (PHB) and (b) ketoprofen (KP). The molecular structures were drawn using ChemSketch software, version 12.1.0.31258.

Under both in vivo and in vitro conditions, albumin undergoes various non-enzymatic post-translational modifications that can substantially alter its stability, biological activity, physicochemical properties, and physiological functions [9,21,22]. Oxidative modifications of Cys34 and methionine residues modulate the protein’s redox state and affect its ligand-binding affinities [23]. Glycation—the covalent attachment of reducing sugars to the ε–amino groups of lysine and/or arginine residues—initiates a cascade of Maillard-type reactions, ultimately leading to advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), a structurally heterogeneous group of irreversible, often cross-linked derivatives with profound consequences for protein conformation and function [21,24]. This process can impair proper protein folding, reduce α–helical content, and alter the accessibility of binding pockets [21,25]. Site-specific glycation at Lys199 and Arg222—key residues within Sudlow’s site I—reduces the binding affinity for bulky heteroaromatic anions such as warfarin and PHB by approximately 30–50%, whereas glycation at Lys414 in Sudlow’s site II decreases its affinity for aromatic carboxylic acids such as ibuprofen and KP by about 25–40% [26,27]. These structural perturbations can have profound pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic implications, such as changing the unbound (free) fraction of drugs in plasma, weakening the protein’s antioxidant defense, and accelerating the progression of complications in metabolic disorders, particularly diabetes mellitus. However, despite extensive studies on drug binding to native and glucose-glycated HSA, comprehensive comparative analyses evaluating the effects of different glycation agents on ligand-induced tertiary structure changes in HSA are still lacking.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy is a well-established and highly sensitive biophysical technique for probing the conformational properties of proteins under a wide range of physicochemical conditions, including changes induced by ligand binding, pH shifts, temperature variations, or post-translational modifications [28,29]. In the far-UV spectral region (190–250 nm), CD signals primarily arise from electronic transitions of the peptide backbone and provide quantitative insight into the content of α-helices, β-sheets, and unordered structural elements. This spectral range enables the assessment of unfolding/refolding processes, as well as structural stability, under varying physicochemical conditions [29]. In contrast, the near-UV region (250–320 nm) provides valuable information about the tertiary structure, as it is shaped by the asymmetric environment of aromatic side chains—mainly phenylalanine (Phe), tyrosine (Tyr), and tryptophan (Trp214)—as well as disulfide bonds. Subtle changes in this region often reflect rearrangements in the local microenvironment of aromatic chromophores, induced by ligand–protein interactions, conformational adaptation, or chemical modification [30]. HSA, which contains 31 Phe residues, 18 Tyr residues, a single Trp residue (Trp214, located in subdomain IIA), and 17 pairs of disulfide bonds [1,31], shows distinct near-UV CD profiles that serve as a sensitive indicator of ligand-induced conformational rearrangements.

Another well-established and widely applied technique for studying proteins and their interactions with ligands at the molecular level is fluorescence spectroscopy. This method allows for the determination of binding constants, identification of binding sites, and characterization of structural changes based on fluorescence intensity, spectral shifts, fluorescence lifetime, anisotropy, or energy transfer [32]. The conformational effects of ligand binding on HSA can be reliably monitored using second-derivative fluorescence spectroscopy applied to albumin and its ligand/-s complexes. This method improves spectral resolution, thereby enabling precise identification of peak positions and intensities [33,34]. Furthermore, the derivative method is less affected by sample turbidity and selectively emphasizes changes in the microenvironment of aromatic residues—particularly Trp214—making it more effective than classical fluorescence spectroscopy for detecting subtle tertiary-structure changes.

The present study aimed to analyse the interactions of two model drugs—PHB (Figure 1a) and KP (Figure 1b), used as selective markers of Sudlow’s site I and II, respectively—with non-modified (HSA) and glycated human serum albumin (gHSAGLC, gHSAFRC, gHSAsyrup), using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy in the near-UV region (250–310 nm) and the second-derivative of fluorescence spectra. The innovative aspect of this work lies in the simultaneous application of two independent spectroscopic techniques to assess tertiary structure changes in HSA induced by drug binding, which, to date, has not been described in the context of glycation with glucose, fructose, and glucose–fructose syrup. In particular, the potential of near-UV CD spectroscopy was demonstrated across a broad wavelength range, and the use of the second-derivative of the albumin emission spectrum was proposed as a sensitive method for detecting local conformational changes. The obtained results not only expand the current understanding of ligand-protein interactions but also highlight the structural and functional consequences of glycation for albumin binding capacity. These findings provide molecular insights into how post-translational modifications such as glycation may affect pharmacokinetics and drug–protein interactions under hyperglycemic and metabolic conditions. Although the spectroscopic methods employed are well-established, their integrated application to a comparative analysis of glycation effects on albumin structure and ligand binding represents a novel and meaningful contribution to the field of bioanalytical and biophysical research.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Assessment of the Tertiary Structure of Albumins by Near-UV CD Spectroscopy

A variety of biophysical and analytical techniques are applied to investigate the influence of ligands on protein structure and stability [35]. However, each technique presents intrinsic limitations, which may stem from specific requirements regarding sample purity and stability, the physicochemical properties of solvents, applicable concentration ranges, as well as high instrumentation costs and time-consuming measurement procedures. Therefore, modern experimental studies increasingly combine several independent techniques or methods to obtain a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of ligand–protein interactions and the associated conformational changes. CD spectroscopy is a valuable and increasingly applied technique for analysing the interactions between macromolecules and ligands, including pharmacologically relevant compounds [29,36]. In particular, near-UV CD spectroscopy provides detailed insights into the tertiary structure of HSA (Figure 2) and enables detection of subtle conformational changes induced by ligand binding [30].

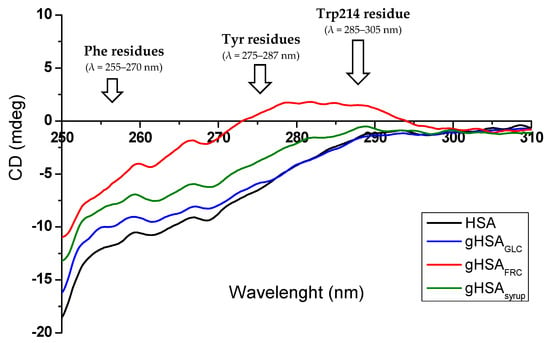

Figure 2.

Near-UV CD spectra of HSA, gHSAGLC, gHSAFRC, and gHSAsyrup (1.30 × 10−5 mol∙L−1) in the range of λ 250–310 nm, with the characteristic spectral regions corresponding to Phe, Tyr, and Trp214 residues.

In the near-UV region, the CD spectrum of albumin reflects the chiroptical contribution of individual aromatic residues, each of which corresponds to signals in a characteristic wavelength range (Figure 2). The side chains of Phe generate signals within the 255–270 nm range, Tyr within 275–287 nm, while Trp214 is responsible for signals in the 285–305 nm region, arising from asymmetrically perturbed electronic transitions in the indole ring [28,29,30]. Additionally, disulfide bridges present in the HSA molecule produce broad, weak signals across the entire near-UV region, with a characteristic low-energy “broad negative tail” extending from approximately 295 nm to 315 nm [30]. As shown in Figure 2, the near-UV CD spectra of non-modified (HSA) and glycated albumin (gHSAGLC, gHSAFRC, gHSAsyrup) exhibit three characteristic spectral regions. In the first region, two distinct minima are observed at (261.8 ± 0.2) nm and (268.4 ± 0.2) nm, which are attributed to the phenyl groups of Phe residues. The second region (270–290 nm) is characterized by a spectral bulge, subtle in the case of HSA, gHSAGLC, and gHSAsyrup, but markedly pronounced in gHSAFRC, primarily arising from the contributions of Tyr residues. Finally, the third region (295–310 nm) displays an almost linear trend with a constant negative ellipticity, reflecting the combined contributions of disulfide bonds and Trp214-related signals. The observed changes in ellipticity values and band shape of HSA in the wavelength range between 250 nm and 310 nm (Figure 2) indicate tertiary structural alterations induced by glycation, with the most pronounced effects observedin HSA modified by fructose (gHSAFRC). This marked structural impact of “fructation” is consistent with previous literature reports highlighting fructose as a particularly reactive glycating agent capable of inducing greater conformational changes in serum albumin compared to other reducing sugars [37,38,39].

As demonstrated by Muzammil et al. [40], changes in ellipticity and the fine structure of near-UV CD spectra serve as sensitive and reliable indicators of tertiary structure alterations in fatty acid-free human serum albumin. The observed reduction in signal intensity, along with the loss of characteristic bands at 275 nm and 292 nm, was attributed to disruptions of the chiral microenvironment surrounding the aromatic residues. Similarly, Zarina Arif et al. [22] reported that nitroxidation of HSA caused a substantial decrease in near-UV CD signal intensity, including the loss of characteristic minima at 262 nm and 268 nm, as well as the tyrosine-specific band at 275 nm. At the same time, far-UV spectra showed comparatively minor changes, indicating that the protein’s secondary structure remained largely intact. These findings confirm that near-UV CD spectroscopy is a particularly sensitive method for detecting subtle conformational rearrangements and monitoring the disruption of the local environment of HSA’s aromatic residues.

Near-UV CD spectroscopy has also been applied as a sensitive tool for rapidly assessing ligand-induced changes in the microenvironment of aromatic amino acid residues (Phe, Tyr, Trp214) within the HSA molecule [41,42]. Using near-UV CD spectroscopy, Kabir et al. [41] demonstrated that lapatinib (LAP), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor used in cancer therapy, affects the tertiary structures of HSA. Their results showed that the CD spectrum of the drug–HSA complex differs significantly from that of unbound HSA, indicating that LAP induces substantial conformational rearrangements in HSA. Similarly, Musa et al. [42] reported that lumefantrine, an antimalarial drug, alters the tertiary structure of HSA upon complex formation. Overall, changes in the shape and/or position of the near-UV CD spectral signals provide direct evidence for ligand-induced modifications in HSA conformation and, consequently, may influence its potential functions [41,42,43].

In the present study, the use of phenylbutazone (PHB, Figure 1a) and ketoprofen (KP, Figure 1b) as markers for Sudlow’s binding sites I and II, respectively, enabled the identification of CD spectral changes and structural alterations in non-modified and glycated albumins within ligand–protein complexes. Figure 3a–d and Figure 4a–d present representative near-UV CD spectra of albumins recorded in the absence of ligands (HSA (a), gHSAGLC (b), gHSAFRC (c), gHSAsyrup (d)) and the presence of PHB (Figure 3a–d) or KP (Figure 4a–d). Tables S1–S3 summarize the mean ellipticity values and corresponding standard deviations (mean ± SD, mdeg) derived from the near-UV CD spectra for HSA, gHSAGLC, gHSAFRC, gHSAsyrup, as well as for the complexes (PHB–albumin)complex—PHB and (KP–albumin)complex—KP, within three spectral wavelength ranges: 255–270 nm (a), 275–287 nm (b), and 285–305 nm (c). Based on preliminary studies, nine wavelengths were selected for comparative spectral analysis. These were as follows: for the Phe residue region—258.4 nm, 262.2 nm, and 268.0 nm (Tables S1a–S3a); for Tyr—275.8 nm, 279.2 nm, and 283.4 nm (Tables S1b–S3b); and for Trp214—286.0 nm, 290.2 nm, and 302.0 nm (Tables S1c–S3c). Complete data, along with the results of statistical tests, is available in the Supplementary Materials.

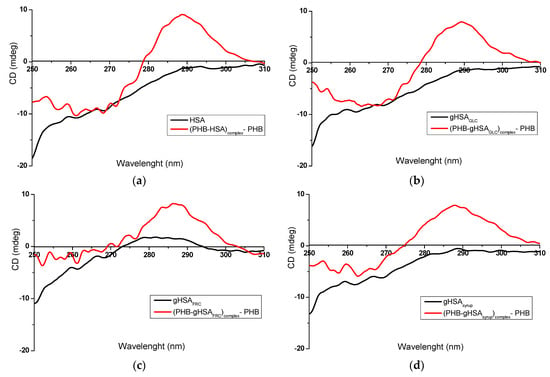

Figure 3.

Near-UV CD spectra of (a) non-glycated HSA and (b–d) glycated albumins, in the absence and presence of PHB, at a ligand/albumin molar ratio of ~8:1.

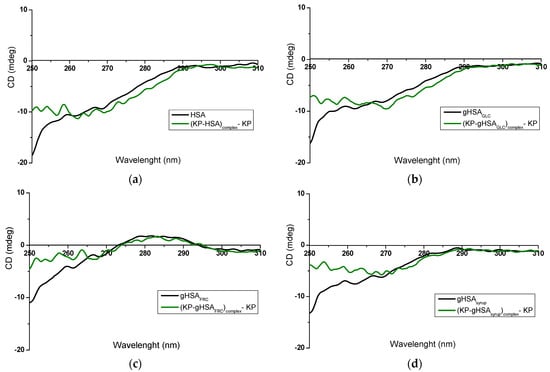

Figure 4.

Near-UV CD spectra of (a) non-glycated HSA and (b–d) glycated albumins, in the absence and presence of KP at a ligand/albumin molar ratio of ~8:1.

Figure 3 presents distinct differences in both the intensity and shape of the near-UV CD spectra recorded for free serum albumin (“albumin”) and its complexes with phenylbutazone (“(PHB–albumin)complex—PHB”). These spectral changes are noticeable for the non-modified HSA (Figure 3a) as well as for modified HSA, regardless of the glycation agent used: gHSAGLC (Figure 3b), gHSAFRC (Figure 3c), and gHSAsyrup (Figure 3d). The formation of the KP–albumin complex also induced changes in the near-UV CD spectra compared to free albumin (Figure 4a–d); however, the magnitude of these changes was smaller than that observed for the PHB–albumin complexes.

Based on the data presented in Table S1a–c, statistically significant differences were found between the CD ellipticity values recorded for free albumin and its complexes with PHB and KP. These differences were observed for at least one wavelength within each of the analysed spectral regions: (a) 255–270 nm, (b) 275–287 nm, and (c) 285–305 nm.

In the wavelength range of 255–270 nm, characteristic for phenylalanine (Phe) residues, statistically significant differences between HSA and (PHB–HSA)complex—PHB (p = 0.0015), as well as between HSA and (KP–HSA)complex—KP (p = 0.0067), were observed exclusively at λ 258.4 nm. Similar differences were also noted for glycated albumins. These results suggest that both PHB and KP, in complexes with either non-modified or glycated HSA, can induce conformational changes in Phe-rich regions, indicating their potential involvement in the binding process. Several of these residues—Phe206, Phe211, Phe223, Phe228, Phe229, and Phe254 in subdomain IIA, and Phe373, Phe374, Phe376, and Phe404 in subdomain IIIA [31]—are located within hydrophobic cores that make a significant contribution to the near-UV CD signal. Even subtle changes in the orientation, packing, or polarity of the microenvironment around these aromatic chromophores can markedly alter the CD spectral profiles. In the wavelength range of 275–287 nm, associated with tyrosine residues (Tyr), and 285–305 nm, characteristic for Trp214, numerous statistically significant differences were also observed between spectra recorded for free albumin and its ligand complexes, especially for the PHB complex (Figure 3). The most pronounced changes were found in the 286–290 nm range, which may indicate alterations in the tertiary structure of albumin, particularly in the vicinity of Trp214, which is located within Sudlow’s site I (subdomain IIA of HSA). In many cases, the level of statistical significance was very high (p < 0.0001), further confirming the importance of the observed changes.

PHB binds to HSA with a high association constant (Ka = 1.5 × 106 L∙mol−1) at Sudlow’s site I in subdomain IIA, while also binding to a secondary site—Sudlow’s site II in subdomain IIIA [9,44]. This ligand–protein interaction is mainly driven by electrostatic forces, with hydrophobic contacts providing additional stabilization [45]. Simultaneous binding at both sites can perturb the tertiary structure and alter the chiral environment of aromatic residues, leading to changes in the near-UV CD signal, observed as higher ellipticity across all three examined spectral regions (Figure 3a: HSA vs. (PHB–HSA)complex—PHB; Figure 3b: gHSAGLC vs. (PHB–gHSAGLC)complex—PHB; Figure 3c: gHSAFRC vs. (PHB–gHSAFRC)complex—PHB; Figure 3d: gHSAsyrup vs. (PHB–gHSAsyrup)complex—PHB). These spectral modifications indicate partial alteration of the tertiary structure and a local loosening of the conformational packing [43]. The slight bulge characteristic of HSA, gHSAGLC, and gHSAsyrup is replaced by a distinct peak with a maximum positive ellipticity in the vicinity of 290 nm (with the peak for gHSAFRC shifted towards shorter wavelengths, Figure 3a–d), most likely reflecting strong PHB binding within Sudlow’s site I, near Trp214. Chignell [46] attributed this effect to π–π interactions between the aromatic moieties of PHB and hydrophobic regions within the albumin binding pocket, leading to a positive Cotton effect. Similar observations were reported by Bertozo et al. [47] using induced circular dichroism (ICD) spectroscopy. Their study aimed to evaluate the impact of oxidative modification of Trp214 and Lys199 on PHB’s affinity for Sudlow’s site I. The authors analysed the tertiary structure of native and oxidized albumin (HSAOX), before and after PHB binding. In both albumins, PHB binding produced a pronounced induced ellipticity peak at ~290 nm (within the 280–300 nm range). The appearance of this peak at ~290 nm provides further evidence for the formation of a stable PHB–albumin complex [48].

KP is a well-established marker of Sudlow’s site II, binding to HSA with association constants of Ka = (2.79 ± 0.36) × 105 L∙mol−1 and Ka = (2.81 ± 0.42) × 105 L∙mol−1 for the R– and S–enantiomers, respectively [15]. Its primary high-affinity site is located in subdomain IIIA (Sudlow’s site II). However, KP can also interact with secondary sites in subdomains IB and IIA, reflecting the presence of multiple classes of binding sites within the protein [9,49]. Binding in these regions can affect not only the structural arrangement of the main binding pocket but also its surrounding microenvironment, generating additional spectral contributions or altering existing ones. The most pronounced near-UV CD differences between free albumin and the (KP–albumin)complex—KP occurred in the 255–270 nm range, dominated by contributions from phenylalanine residues with smaller but still detectable changes in the regions associated with Tyr and Trp214 (Figure 4). The observed spectral changes, consistent for both non-modified and glycated albumin, indicate that KP binding most strongly perturbs the local environment of Phe residues—likely due to their prevalence within the hydrophobic core of subdomain IIIA and their significant contribution to the near-UV CD signal.

The presented results confirm the usefulness of CD spectroscopy as a sensitive tool for monitoring local structural changes in albumin induced by the binding of PHB and KP, which are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and represent markers of Sudlow’s site I and II, respectively. Table S2 presents the CD ellipticity values for complexes of non-modified and glycated albumin with phenylbutazone ((PHB–albumin)complex—PHB). These data indicate that glycation significantly affects the interaction between PHB and HSA, with the most pronounced CD signal changes observed for albumin glycated by fructose (gHSAFRC). This may indicate more extensive disturbances in the tertiary structure of albumin, especially in regions containing Tyr and Trp214 residues. Consequently, glycation appears to alter HSA conformation and its binding affinity for PHB substantially. Similarly to the effects reported by Graciani and Ximenes [48] for pH-induced conformational transitions, such perturbations in the chiral environment of aromatic residues and disulfide bridges can markedly alter near-UV CD spectral profiles, reflecting structural loosening and changes in domain packing. Conversely, the data shown in Table S3, describing the interaction of albumin with ketoprofen ((KP–albumin)complex—KP), reveal less pronounced changes in CD ellipticity signals than those observed for PHB (Table S2). The most considerable statistically significant differences relative to HSA were observed for complexes with gHSAFRC and gHSAsyrup at 275–287 nm and 285–305 nm, suggesting an influence of KP on the local environment of Tyr and Trp214 residues in modified albumin, although to a lesser extent than PHB. The near-UV CD spectra revealed distinct alterations in ellipticity between non-glycated and glycated albumin, particularly in the presence of PHB, indicating ligand-induced perturbations in the microenvironment of aromatic residues. In the near-UV region, these spectral variations may partly reflect induced circular dichroism (ICD) effects arising from coupling between ligand and protein transition moments. Nevertheless, since all spectra were recorded under identical experimental conditions and corrected for the free ligand contribution, the differences can be interpreted as consistent ligand-induced perturbations within the aromatic microenvironment of the macromolecule. This interpretation aligns with previous reports that used near-UV CD spectroscopy to monitor tertiary conformational changes in HSA–ligand complexes [41,42,50].

2.2. Assessment of the Tertiary Structure of Albumins by Second-Derivative Fluorescence Spectra

Based on the obtained results, second-derivative spectroscopy of “differential” fluorescence spectra was selected as a complementary reference method to near-UV CD spectroscopy (Section 2.1). This approach enables a more precise comparison between albumin in its free form (“albumin”) and its ligand–bound complexes (“(ligand–albumin)complex—ligand”). Enhancing spectral resolution and minimizing background interference allows the detection of subtle conformational changes in the vicinity of aromatic residues (particularly Tyr and Trp214) [51]. Such differences, often invisible in classical fluorescence spectra, become especially evident when assessing structural rearrangements induced by ligand binding or by structural modifications of HSA, such as glycation.

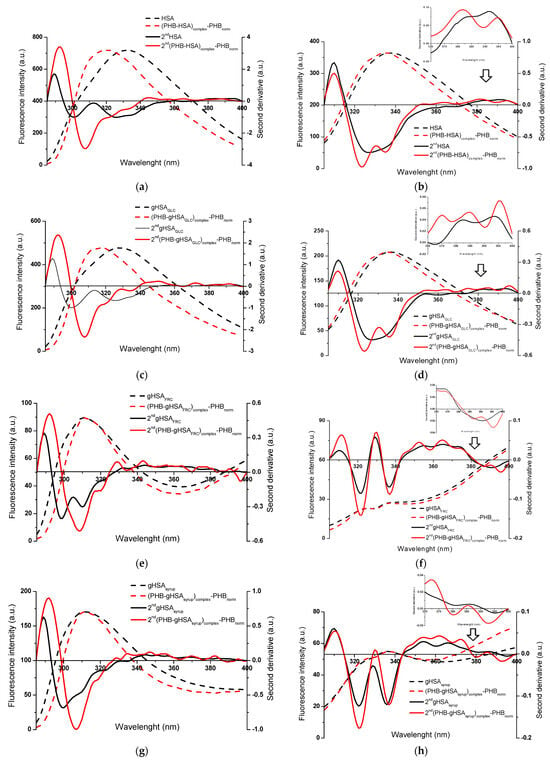

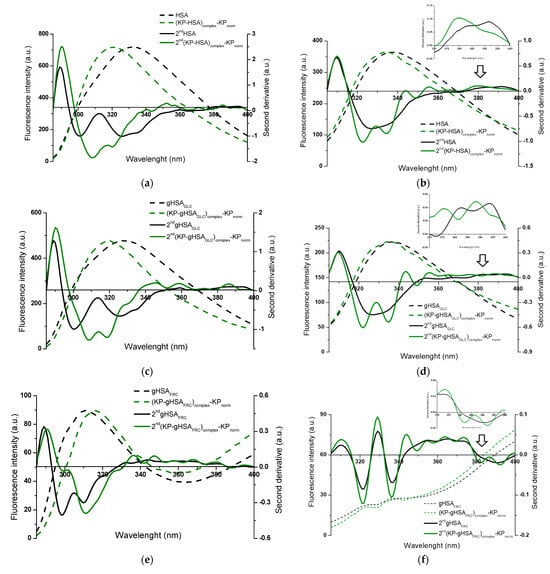

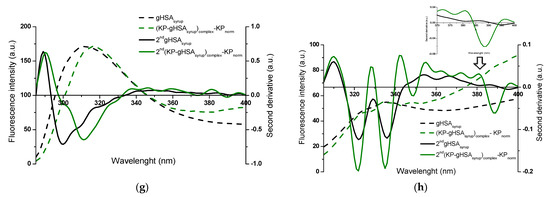

The diagrams below illustrate fluorescence emission and the second-derivative spectra of native and glycated albumins, free or complexed with PHB (Figure 5) and KP (Figure 6). Prior to obtaining the second-derivative spectra (2nd (ligand–albumin)complex—ligandnorm), the fluorescence spectra of each (ligand–albumin)complex—ligand were normalized to the corresponding maximum fluorescence intensity of free albumin.

Figure 5.

Fluorescence emission spectra of (PHB–albumin)complex—PHBnorm normalized to the maximum fluorescence intensities of albumin, with the corresponding second-derivative spectra (2nd) for (a,b) HSA and (c–h) glycated albumins; λex 275 nm (left panels) and λex 295 nm (right panels). Insert: detail of the Trp214 region (370–400 nm); ligand-to-albumin molar ratio of ~15:1.

Figure 6.

Fluorescence emission spectra of (KP–albumin)complex—KPnorm normalized to the maximum fluorescence intensities of albumin, with the second-derivative flu spectra (2nd) for (a,b) HSA and (c–h) glycated albumins; λex 275 nm (left panels) and λex 295 nm (right panels). Insert: detail of the Trp214 region, covering the 370–400 nm wavelength range; ligand-to-albumin molar ratio of ~15:1.

The alterations observed in the second-derivative spectra within the 370–400 nm range and below 320 nm indicate structural reorganization in the microenvironment of albumin, specifically around tryptophan (Trp214) and the seventeen tyrosyl residues distributed across the hydrophobic subdomains IA (Tyr138, Tyr140), IB (Tyr150, Tyr161), IIA (Tyr263, Tyr319, Tyr332, Tyr334, Tyr341, Tyr353), IIB (Tyr401, Tyr452), IIIA (Tyr411, Tyr497, Tyr510), and IIIB (Tyr520, Tyr527), respectively [31,33,34]. This highlights the advantage of second-derivative spectroscopy over classical emission fluorescence spectra, where distinguishing between Tyr- and Tpr214-derived signals is considerably more demanding.

Based on Figure 5 and Figure 6, differences in specific regions of the second-derivative fluorescence spectra were observed between albumin in the absence (“2nd albumin”) and in the presence of ligands (“2nd (ligand–albumin)complex—ligandnorm”). These changes were evident for native albumin (2nd HSA: Figure 5a,b and Figure 6a,b) and its glycated forms (2nd gHSAGLC: Figure 5c,d and Figure 6c,d; 2nd gHSAFRC: Figure 5e,f and Figure 6e,f; 2nd gHSAsyrup: Figure 5g,h and Figure 6g,h), in complexes with PHB (Figure 5a–h) as well as KP (Figure 6a–h). The observed alterations reflect modifications in the microenvironment of aromatic residues induced by ligand binding. Moreover, the differences between HSA and its glycated forms—particularly pronounced for albumin glycated with fructose and syrup—indicate that glycation substantially contributes to the structural reorganization of albumin. To quantify these spectral variations and provide a sensitive indicator of polarity changes in the vicinity of aromatic residues, the empirical H parameter (relative peak contribution) defined by Mozo-Villarias [34] was applied. This parameter, determined by the peak-to-peak method as the distance between the positive peak maximum and the negative peak minimum in the spectrum, enables precise monitoring of structural rearrangements around Trp214 and Tyr residues. For λex 295 nm, the parameter H295nm represents the difference between the minimum and maximum values within the 370–400 nm range of the second-derivative fluorescence spectra. In contrast, for λex 275 nm, H275nm is defined as the difference between the minimum and maximum values below 320 nm [52,53]. The calculated values of the H parameter for non-glycated and glycated albumins, in their free forms and complexes with PHB or KP, at λex 275 nm and λex 295 nm are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Parameter H determined for non-glycated albumin (HSA), glycated albumins (gHSAGLC, gHSAFRC, gHSAsyrup), and their complexes with PHB and KP; λex 275 nm and λex 295 nm.

Table 2.

Values of parameter H determined for complexes of HSA and gHSAGLC, gHSAFRC, gHSAsyrup) with PHB and KP at λex 275 nm and λex 295 nm.

Aromatic residues, such as Phe, Tyr, and Trp214, play a crucial role in determining the structural and functional properties of HSA. Changes in their microenvironment can provide important insights into the protein’s conformational changes caused by ligand binding. When using λex 275 nm, which excites both Trp214 and Tyr residues and thus represents the global environment of the aromatic chromophores, statistically significant differences in H parameter values were observed between free albumin and its complexes with PHB or KP, for both the native and glycated forms of HSA (Table 1). It should be noted that empirical H values greater than 1 indicate a less polar (more hydrophobic) microenvironment of aromatic residues, whereas H values below 1 reflect increased local polarity and greater solvent accessibility. The presence of PHB resulted in increased H values, indicating a more hydrophobic microenvironment. This suggests that the region surrounding the aromatic residues becomes more rigid and ordered. Conversely, the effect of KP varied depending on glycation: for native HSA and gHSAGLC, the H value decreased, suggesting a more polar environment. However, for gHSAFRC and gHSAsyrup, the H value increased, indicating enhanced hydrophobicity. In contrast, for λex 295 nm, which selectively excites the microenvironment of Trp214, no statistically significant differences in H values were detected between free albumin and ligand–albumin complexes, except for gHSAsyrup vs. KP–(gHSAsyrup)complex—KPnorm (Table 1). This indicates that neither PHB nor KP substantially modifies the hydrophobicity near Trp214 in most cases.

It is noteworthy that both tyrosine and tryptophan residues are located within the main drug-binding regions of HSA. Sudlow’s site I (subdomain IIA) contains Tyr263, Tyr319, Tyr332, Tyr334, Tyr341, Tyr353 and Trp214, whereas Sudlow’s site II (subdomain IIIA) includes Tyr411, Tyr497, Tyr510 [31]. Ligand-induced alterations in the H parameter at λex 275 nm, therefore, most likely reflect interactions within one or several of these sites. In addition, other Tyr residues (e.g., Tyr138, Tyr161, and Tyr401 in fatty acid binding regions, and Tyr84 near the Cys34 site) may further contribute to these changes [54]. Trp214 is highly responsive to alterations in its microenvironment and typically reflects ligand binding to Sudlow’s site I; however, the generally stable H parameter at λex 295 nm suggests that PHB and KP did not significantly affect the hydrophobicity of its surroundings.

Glycation itself had a pronounced effect on the aromatic microenvironment. Compared with native HSA, the glycated forms displayed markedly lower H values at λex 275 nm, consistent with a more polar, solvent-exposed environment of aromatic residues (Table 1). Ligand binding further modulated these glycation-related changes: PHB enhanced hydrophobicity in native HSA, but this effect was strongly attenuated in glycated proteins, especially in gHSAFRC and gHSAsyrup. KP exerted opposite effects, decreasing H in native HSA and gHSAGLC, but increasing it in gHSAFRC and gHSAsyrup. These findings indicate that glycation not only shifts the baseline polarity of aromatic residues but also reshapes the mode of ligand interaction with the protein. Overall, glycation primarily perturbs global structural domains of HSA, particularly Tyr-rich regions, while the Trp214 pocket remains relatively stable. Consequently, ligands such as PHB and KP act upon an already altered conformational background, with their impact depending on the glycation agent. These findings highlight that glycation-related heterogeneity must be taken into account when evaluating albumin–drug interactions and their consequences for drug binding, distribution, and pharmacological activity.

Based on the analyses presented in Section 2.1 and Section 2.2, the combined use of near-UV circular dichroism (CD) and second-derivative fluorescence spectroscopy at the preliminary stage provides a rapid and comprehensive approach for assessing ligand–albumin interactions. These techniques enable the identification of specific interaction regions—particularly the microenvironments of Phe, Tyr, and Trp214 residues—and the evaluation of how protein structural modifications affect these interactions. In fact, similar perturbations of the aromatic microenvironment have been reported by Chudzik et al. [52], who demonstrated that molecular ageing of serum albumin leads to oxidation-induced structural rearrangements detectable, among other methods, by second-derivative fluorescence spectroscopy.

It should be emphasized that the present investigation focused on tertiary structure changes. The absence of far-UV CD measurements limits the direct assessment of secondary structural elements such as α-helices and β-sheets. As discussed by Arif et al. [22] and Kelly and Price [28], rearrangements in tertiary and secondary structures may occur independently. While additional far-UV CD data could enhance the interpretation of the results, this analysis was beyond the aims of the present study. Future research will integrate far-UV CD, near-UV CD, spectrofluorimetry, UV-Vis, and nano-ITC methods to provide a more complete understanding of how modification/glycation and ligand binding affect the structural and functional properties of human serum albumin.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Reagents

ImmunO Human Serum Albumin, fraction V (HSA, Lot No. 8234H) and ketoprofen (KP, Lot No. 7213J) were provided by MP BiomedicalsTM (Illkirch-Graffenstaden, France); phenylbutazone (PHB, Lot No. 78H1117) and sodium azide (NaN3, Lot No. BCBD6941V) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (Darmstadt, Germany); D(−)-fructose (FRC, Lot No. A0282904) and D(+)-glucose (GLC, Lot No. A0299881) were gained from POCH S.A. (Gliwice, Poland); di-Potassium hydrogen phosphate pure p.a. (K2HPO4) and sodium dihydrogen phosphate dehydrate (NaH2PO4 × 2H2O) were purchased from Eurochem BGD Sp. z o.o. (Tarnów, Poland). The stock solution of KP and PHB were prepared by dissolving appropriate amounts in methanol from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany, Lot No. 32373611/18). All chemicals and reagents used in this study were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Sample Preparation

HSA Glycation Process: Prior to in vitro glycation of human serum albumin (HSA), all glassware and spatulas were sterilized to prevent bacterial contamination. Glycated albumins (gHSAGLC, gHSAFRC, gHSAsyrup) were prepared by incubating HSA solutions (2 × 10−5 mol∙L−1) with D(+)-glucose (GLC, 0.05 mol∙L−1), D(−)-fructose (FRC, 0.05 mol∙L−1), or glucose–fructose syrup (GFS, 0.05 mol∙L−1; 55% GLC + 45% FRC) in phosphate buffer (0.05 mol∙L−1, pH = 7.4 ± 0.1) containing sodium azide (0.015 mol∙L−1) as preservative. The mixtures were incubated in sterile closed tubes at 37 °C for 21 days. A native, control sample (HSA) was prepared analogously, without the addition of reducing sugars. After incubation, both non-glycated HSA and glycated albumins were extensively dialyzed against phosphate buffer for 24 h to remove unbound sugars and subsequently filtered through sterile Millex-GP syringe filters with 0.2 μm pores (Merck Millipore Ltd., Tullagreen, Carrigtwohill, Co. Cork, Ireland). The absorbance ratio (A255/A280) was <0.5 for all preparations, confirming the purity of the albumin solutions.

Investigating Ligand–Albumin Interactions: PHB and KP stock solutions were prepared by dissolving the appropriate amounts in methanol, ensuring that MeOH did not exceed 1% (v/v) in the final concentration. The stock concentration of ligands was 1 × 10−2 mol∙L−1, while albumin solutions (HSA, gHSAGLC, gHSAFRC, and gHSAsyrup) were ~1.30 × 10−5 mol∙L−1. For spectropolarimetric measurements (near-UV CD), ligand-to-albumin molar ratio of 8:1 was applied, whereas for spectrofluorimetric experiments, the ratio was 15:1. All measurements were conducted after 90 min incubation of the ligand–albumin and ligand–buffer mixtures.

3.2.2. Circular Dichroism (CD) and Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Near-UV CD Measurements: Near-UV CD spectra of native and glycated albumins, as well as phosphate buffer in the absence or presence of PHB and KP, were recorded on a JASCO J-1500 CD spectropolarimeter (JASCO International Co., Ltd., Hachioji, Tokyo, Japan) at 37 °C under a constant nitrogen purge. Spectra were measured in a 10 mm path length quartz cuvette over the range of 250–310 nm, using a wavelength interval of 0.2 nm, a bandwidth of 2.0 nm, a digital integration time (D.I.T.) of 2 s, and a scan speed of 50 nm/min. For reliable interpretation, ellipticity values (mdeg) were analyzed within three characteristic wavelength intervals: 255–270 nm, 275–287 nm, and 285–305 nm. In addition, mean ellipticity values were compared at nine selected wavelengths corresponding to aromatic residues of albumin: 258.4 nm, 262.2 nm, 268.0 nm, 275.8 nm, 279.2 nm, 283.4 nm, 286.0 nm, 290.2 nm, and 302.0 nm. The buffer blank spectrum was subtracted from all CD measurements. Difference spectra, labeled as “(PHB–albumin)complex—PHB and (KP–albumin)complex—KP”, were obtained by mathematically subtracting the CD signal of the free ligand (PHB–buffer or KP–buffer) from that of the corresponding ligand–albumin complex. Although this procedure does not eliminate induced circular dichroism (ICD) signals arising from ligand binding, it allows for relative comparisons between native and glycated albumin recorded under identical experimental conditions and ligand concentrations.

Fluorescence Analysis: Fluorescence spectra were measured at 37 °C using a JASCO FP-6500 spectrofluorimeter (JASCO International Co., Ltd., Hachioji, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Peltier thermostat (∆t ± 0.2 °C) and quartz cuvettes with dimensions of 1.0 cm × 1.0 cm × 4.0 cm. Spectra corresponding to Trp214 and Tyr residues of non-glycated HSA and glycated albumins (gHSAGLC, gHSAFRC, gHSAsyrup), as well as their complexes with PHB and KP, were collected at λex 295 nm (λem 305–400 nm) and λex 275 nm (λem 285–400 nm), respectively. Measurements were performed with spectral bandwidths of 3 nm (excitation) and 5 nm (emission), a scanning speed of 100 nm/min, “Medium” signal sensitivity, and a response time of 2 s. Difference emission spectra of albumin and its ligand mixtures were obtained by mathematical subtraction of the corresponding free ligand spectra. Subsequently, the Savitzky–Golay algorithm (15 points) was applied to calculate the second-derivative of the fluorescence spectra, from which the empirical H parameter (relative peak contribution) was determined. Prior to second-derivative analysis (2nd (ligand–albumin)complex—ligandnorm), the zero-order spectra of each (ligand–albumin)complex—ligand were arithmetically normalized to the corresponding maximum fluorescence intensity of free albumin.

All fluorescence and near-UV CD spectra presented in this study were smoothed using the Savitzky and Golay method with a convolution width of 11 (Spectra Analysis software, version 1.53.07, JASCO, Easton, MD, USA) and subsequently visualized with OriginPro 8.5 SR1 (Northampton, MA, USA).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3), and results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD). Statistical comparisons between two groups—albumin vs. (PHB–albumin)complex—PHBnorm or albumin vs. (KP–albumin)complex—KPnorm—were carried out for non-glycated (HSA) and glycated albumin (gHSAGLC, gHSAFRC, gHSAsyrup). Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk W test, complemented by inspection of frequency histograms. The homogeneity of variances was evaluated with Levene’s test. When both assumptions were satisfied, Student’s t-test was applied to identify statistically significant differences between groups. For comparisons involving more than two groups (e.g., (ligand–albumin)complex—ligandnorm), one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used under the assumptions of normal distribution and homogeneity of variances, with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test applied for pairwise comparisons. When at least one of these assumptions was violated, the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA by multiple comparisons of mean ranks (MCT) was followed. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistica software, version 13.3 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The complete near-UV CD dataset, together with the results of statistical analyses, is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

4. Conclusions

This study provides the first integrated spectroscopic comparison of human serum albumin (HSA) in its non-glycated and glycated by glucose, fructose, and glucose–fructose syrup forms, achieved by combining near-UV CD with second-derivative fluorescence spectroscopy. The complementary use of these two techniques enabled a sensitive and detailed characterization of glycation-induced alterations in tertiary structure and their impact on ligand binding.

- (i)

- Glycation significantly alters the tertiary structure of HSA and reduces its drug-binding capacity at Sudlow’s sites I and II. Fructose-glycated HSA showed the most pronounced structural changes, confirming fructose as the most reactive glycation agent.

- (ii)

- PHB induced distinct structural rearrangements, manifested by a characteristic enhancement of the ellipticity peak at ~290 nm, which indicates perturbations in the chiral environment near Trp14 within Sudlow’s site I.

- (iii)

- KP caused weaker, site-specific conformational perturbations, primarily within hydrophobic domains enriched in Phe residues.

- (iv)

- Glycation reduces the hydrophobicity of the aromatic residue environment, making it more exposed and polar, whereas the microenvironment of Trp214 remained relatively stable.

- (v)

- Ligands modulate the conformational flexibility of glycated albumin mainly through the reorganization of Tyr-rich domains, rather than by directly affecting the surroundings of the single Trp214.

- (vi)

- The findings demonstrate that glycation heterogeneity significantly influences drug binding, a finding relevant to pharmacokinetics in diabetes and other metabolic disorders.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr13124000/s1, Table S1: Data obtained from the near-UV CD spectra in the following ranges: (a) 255–270 nm, (b) 275–287 nm, (c) 285–305 nm, for non-glycated (HSA) and glycated albumin (gHSAGLC, gHSAFRC, gHSAsyrup) and mixtures (ligand–albumin)complex after substraction of the spectrum of the free ligand ((PHB–HSA)complex—PHB and (KP–albumin)complex—KP); Table S2: Data obtained from the near-UV CD spectra in the following ranges: (a) 255–270 nm, (b) 275–287 nm, (c) 285–305 nm, for complexes of non-glycated (HSA) and glycated albumin (gHSAGLC, gHSAFRC, gHSAsyrup) with phenylbutazone ((PHB–albumin)complex—PHB), after subtraction of the spectrum of the free ligand (PHB); Table S3: Data obtained from the near-UV CD spectra in the following ranges: (a) 255–270 nm, (b) 275–287 nm, (c) 285–305 nm, for complexes of non-glycated (HSA) and glycated albumin (gHSAGLC, gHSAFRC, gHSAsyrup) with ketoprofen ((KP–albumin)complex—KP), after subtraction of the spectrum of the free ligand (KP).

Funding

This research was funded by the Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland (Grant No. BNW-2-013/K/3/F and BNW-1-049/N/4/F).

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying the findings of this study are accessible upon reasonable request to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AGEs | Advanced glycation end-products |

| CD | Circular dichroism |

| FRC | D(−)-fructose |

| GLC | D(+)-glucose |

| GFS | Glucose–fructose syrup |

| HSA | Human serum albumin |

| gHSAFRC | Human serum albumin glycated by fructose |

| gHSAGLC | Human serum albumin glycated by glucose |

| gHSAsyrup | Human serum albumin glycated by glucose–fructose syrup |

| KP | Ketoprofen |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| PHB | Phenylbutazone |

References

- Peters, T. All About Albumin. In Biochemistry, Genetics, and Medical Applications; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 9–19,228–234. [Google Scholar]

- Fasano, M.; Curry, S.; Terreno, E.; Galliano, M.; Fanali, G.; Narciso, P.; Notari, S.; Ascenzi, P. The extraordinary ligand binding properties of human serum albumin. IUBMB Life 2005, 57, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, K.; Chuang, V.T.G.; Maruyama, T.; Otagiri, M. Albumin–Drug Interaction and Its Clinical Implication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1830, 5435–5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Heath, R.J. Structural and Biochemical Features of Human Serum Albumin Essential for Eukaryotic Cell Culture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragh-Hansen, U. Human Serum Albumin: A Multifunctional Protein with Multiple Binding Sites for Endogenous and Exogenous Ligands. Biol. Chem. 2016, 397, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Sitar, M.E.; Aydin, S.; Cakatay, U. Human serum albumin and its relation with oxidative stress. Clin. Lab. 2013, 59, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.M.; Ho, J.X.; Ruble, J.R.; Rose, J.; Ruker, F.; Ellenburg, M.; Murphy, R.; Click, J.; Soistman, E.; Wilkerson, L.; et al. Structural studies of several clinically important oncology drugs in complex with human serum albumin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1830, 5356–5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Carter, D. Atomic structure and chemistry of human serum albumin. Nature 1992, 358, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbani, G.; Ahn, S.N. Structure, enzymatic activities, glycation and therapeutic potential of human serum albumin: A natural cargo. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 123, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, F.; Shareghi, B.; Farhadian, S.; Momeni, L. Structural insights into the binding behavior of favonoids naringenin with human serum albumin. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 349, 118431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudlow, G.; Birkett, D.J.; Wade, D.N. The characterization of two specific drug binding sites on human serum albumin. Mol. Pharmacol. 1975, 11, 824–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Bahrami, S.; Ravari, S.B.; Zangabad, P.S.; Mirshekari, H.; Bozorgomid, M.; Shahreza, S.; Sori, M.; Hamblin, M.R. Albumin nanostructures as advanced drug delivery systems. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2016, 13, 1609–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghuman, J.; Zunszain, P.A.; Petitpas, I.; Bhattacharya, A.A.; Otagiri, M.; Curry, S. Structural basis of the drug-binding specificity of human serum albumin. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 353, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czub, M.P.; Handing, K.B.; Venkataramany, B.S.; Cooper, D.R.; Shabalin, I.G.; Minor, W. Albumin-Based Transport of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Mammalian Blood Plasma. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 6847–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, N.; Lapicque, F.; Magdalou, J.; Abiteboul, M.; Netter, P. Stereoselective binding of the glucuronide of ketoprofen enantiomers to human serum albumin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994, 48, 1693–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaeean, B.; Kabiri, M.; Iranfar, H.; Saberi, M.R.; Chamani, J. Binding Effect of Common Ions to Human Serum Albumin in the Presence of Norfloxacin: Investigation with Spectroscopic and Zeta Potential Approaches. J. Solut. Chem. 2012, 41, 1777–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, J.R.; Zunszain, P.A.; Hamilton, J.A.; Curry, S. Locating of high and low affinity fatty acid binding sites on human serum albumin revealed by NMR drug-competition analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 361, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.A.; Grüne, T.; Curry, S. Crystallographic Analysis Reveals Common Modes of Binding of Medium and Long-Chain Fatty Acids to Human Serum Albumin. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 303, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragh-Hansen, U.; Brennan, S.O.; Minchiotti, L.; Galliano, M. Modified high-affinity binding of Ni2+, Ca2+ and Zn2+ to natural mutants of human serum albumin and proalbumin. Biochem. J. 1994, 301, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otagiri, M.; Chuang, V.T.G. Albumin in Medicine: Pathological and Clinical Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi, S.; Saraswathi, N.T. Non-enzymatic glycation mediated structure–function changes in proteins: Case of serum albumin. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 90739–90753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Z.; Arfat, M.; Ahmad, J.; Zaman, A.; Islam, S.; Khan, M. Relevance of Nitroxidation of Albumin in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Biochemical and Clinical Study. J. Clin. Cell. Immunol. 2015, 6, 1000324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oettl, K.; Stauber, R.E. Physiological and pathological changes in the redox state of human serum albumin critically influence its binding properties. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 151, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaklai, N.; Garlick, R.L.; Bunn, H.F. Nonenzymatic glycosylation of human serum albumin alters its conformation and function. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 3812–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetter, S.W.; Indurthi, V.S. Moderate glycation of human serum albumin affects folding, stability, and ligand binding. Clin. Chim. Acta 2011, 412, 2105–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguizola, J.; Matsuda, R.; Barnaby, O.S.; Hoy, K.S.; Wa, C.; DeBolt, E.; Koke, M.; Hage, D.S. Review: Glycation of human serum albumin. Clin. Chim. Acta 2013, 425, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mötzing, M.; Blüher, M.; Grunwald, T.; Hoffmann, R. Immunological Quantitation of the Glycation Site Lysine-414 in Serum Albumin in Human Plasma Samples by Indirect ELISA Using Highly Specific Monoclonal Antibodies. Chembiochem 2024, 25, e202300550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.M.; Price, N.C. The Use of Circular Dichroism in the Investigation of Protein Structure and Function. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2000, 1, 349–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, B.; Gill, P. Circular Dichroism Techniques: Biomolecular and Nanostructural Analyses—A Review. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2009, 74, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zsila, F. Circular Dichroism Spectroscopic Detection of Ligand Binding Induced Subdomain IB Specific Structural Adjustment of Human Serum Albumin. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 10798–10806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.C.; Ho, J.X. Structure of Serum Albumin. Adv. Protein Chem. 1994, 45, 153–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocz, G.; Ross, J. Fluorescence Techniques in Analysis of Protein–Ligand Interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 1008, 169–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, V.K.; Kalonia, D.S. Second derivative tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy as a tool to characterize partially unfolded intermediates of proteins. Int. J. Pharm. 2005, 294, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozo-Villarías, A. Second derivative fluorescence spectroscopy of tryptophan in proteins. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 2002, 50, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P. Modern Biophysical Approaches to Study Protein–Ligand Interactions. Biophys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 13, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekmat, A.; Hajebrahimi, Z.; Motamedzade, A. Structural Changes of Human Serum Albumin (HSA) in Simulated Microgravity. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 3941–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkudlarek, A.; Sułkowska, A.; Maciążek-Jurczyk, M.; Chudzik, M.; Równicka-Zubik, J. Effects of Non-Enzymatic Glycation in Human Serum Albumin. Spectroscopic Analysis. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2016, 152, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkudlarek, A.; Pentak, D.; Ploch, A.; Pożycka, J.; Maciążek-Jurczyk, M. In Vitro Investigation of the Interaction of Tolbutamide and Losartan with Human Serum Albumin in Hyperglycemia States. Molecules 2017, 22, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaman, A.; Arif, Z.; Moinuddin; Alam, K. Fructose–Human Serum Albumin Interaction Undergoes Numerous Biophysical and Biochemical Changes before Forming AGEs and Aggregates. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 109, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzammil, S.; Kumar, Y.; Tayyab, S. Molten Globule-Like State of Human Serum Albumin at Low pH. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 266, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.Z.; Mukarram, A.K.; Mohamad, S.B.; Alias, Z.; Tayyab, S. Characterization of the Binding of an Anticancer Drug, Lapatinib to Human Serum Albumin. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 160, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, K.A.; Ridzwan, N.F.W.; Mohamad, S.B.; Tayyab, S. Exploring the Combination Characteristics of Lumefantrine, an Antimalarial Drug and Human Serum Albumin through Spectroscopic and Molecular Docking Studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dockal, M.; Carter, D.C.; Rüker, F. Conformational Transitions of the Three Recombinant Domains of Human Serum Albumin Depending on pH. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 3042–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamasaki, K.; Maruyama, T.; Kragh-Hansen, U.; Otagiri, M. Characterization of Site I on Human Serum Albumin: Concept about the Structure of a Drug Binding Site. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1996, 1295, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russeva, V.; Mihailova, D. Binding of Phenylbutazone to Human Serum Albumin. Characterization and Identification of Binding Sites. Arzneimittelforschung 1999, 49, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chignell, C.F. Optical Studies of Drug–Protein Complexes II. Interaction of Phenylbutazone and Its Analogues with Human Serum Albumin. Mol. Pharmacol. 1969, 5, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertozo, L.C.; Tavares Neto, E.; Oliveira, L.C.; Ximenes, V.F. Oxidative Alteration of Trp-214 and Lys-199 in Human Serum Albumin Increases Binding Affinity with Phenylbutazone: A Combined Experimental and Computational Investigation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciani, F.S.; Ximenes, V.F. Investigation of Human Albumin-Induced Circular Dichroism in Dansylglycine. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoharan, P.; Wong, Y.H.; Tayyab, S. Stabilization of Human Serum Albumin against Urea Denaturation by Diazepam and Ketoprofen. Protein Pept. Lett. 2015, 22, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogóż, W.; Owczarzy, A.; Kulig, K.; Maciążek-Jurczyk, M. Ligand–Human Serum Albumin Analysis: The Near-UV CD and UV–Vis Spectroscopic Studies. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 3119–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrieri, C.; Colonna, G.; Giovane, A.; Irace, G.; Servillo, L. Second- Derivative Spectroscopy of Proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 1978, 90, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudzik, M.; Maciążek-Jurczyk, M.; Pawełczak, B.; Sułkowska, A. Spectroscopic Studies on the Molecular Ageing of Serum Albumin. Molecules 2017, 22, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szkudlarek, A. Effect of Palmitic Acid on Tertiary Structure of Glycated Human Serum Albumin. Processes 2023, 11, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanali, G.; di Masi, A.; Trezza, V.; Marino, M.; Fasano, M.; Ascenzi, P. Human Serum Albumin: From Bench to Bedside. Mol. Asp. Med. 2012, 33, 209–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).