Abstract

Accurate estimation of regional sewage generation is essential for designing reliable and resource-efficient treatment facilities. This study developed an ensemble machine-learning framework to estimate annual sewage generation (SG) as the primary output variable, using a combination of demographic, socioeconomic, and environmental indicators across multiple regions in Korea. The proposed Voting Regressor model, trained using data from four highly urbanized regions (Regions A–D), effectively captured nonlinear interactions among variables such as population, business establishments, economically active population, rainfall, and gross regional domestic product (GRDP). A generalization test on an unseen region (Region E) confirmed the model’s robustness and transferability, demonstrating that the framework can reliably adapt to regions with different demographic and industrial characteristics. Comparative analyses showed that the model outperformed both the Random Forest and the conventional per capita unit-load (GU) method in terms of the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE). SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) analysis further identified business establishments and GRDP as the dominant contributors to sewage generation. Moreover, model-based capacity estimations incorporating a 20% safety factor are closely aligned with actual facility capacities, revealing that conventional design standards often apply excessively conservative margins. The findings demonstrate that the proposed machine learning framework can quantitatively assess design adequacy and prevent structural overestimation while maintaining sufficient operational reserves. This data-driven approach provides an interpretable and adaptable foundation for future sewage infrastructure planning and rational capacity design under evolving socioeconomic and environmental conditions.

1. Introduction

Rapid urbanization and climate change have introduced persistent challenges to the planning and operation of sewage treatment facilities [1]. Sewage inflow behaves nonlinearly over time, affected by various socioeconomic and environmental factors such as population composition, industrial activity, lifestyle, and rainfall [2]. For sustainable sewage treatment plant operation and rational capacity design, these non-linear factors must be quantitatively reflected. Reliable estimation of influent load plays a critical role in process optimization, design safety margins, chemical and energy management, and the formulation of adaptive operation strategies under climate variability [3].

Conventionally, the influent load of sewage treatment facilities has been calculated using the per capita unit-load method [4]. Although this approach is simple and widely used in preliminary design, its dependence on population size limits its ability to reflect regional heterogeneity, such as industrial structure, demographic aging, or local rainfall intensity. Facilities designed using a single fixed coefficient often face discrepancies between projected and actual inflow volumes, leading to inefficiencies in process operation, unstable treatment performance, and misaligned design capacities.

As demographic and socioeconomic structures evolve, the reliability of fixed-coefficient load estimation has been further diminished [5]. Changes in household composition, aging populations, and regional economic disparities introduce distinct water use behaviors and discharge profiles [6]. Moreover, irregular rainfall and seasonal inflow fluctuations caused by climate change have increased the temporal uncertainty of influent loading [7]. These multidimensional factors indicate that simple coefficient-based estimation is inadequate for guiding process design or operational management in modern sewage systems.

Recently, data-driven modeling approaches such as ensemble regression have been applied to improve the estimation of influent loads for sewage facilities [8]. These models can account for multiple interacting variables and nonlinear dependencies, thereby complementing the structural weaknesses of the traditional unit-load approach. However, most prior studies have focused primarily on predictive performance without discussing how such models can support design decisions or quantify the influence of key factors affecting influent variation [9].

However, despite recent applications of machine-learning models, existing studies still exhibit three unresolved limitations. First, most prior works focus on predictive accuracy and provide limited interpretability regarding how socioeconomic factors contribute to influent variability. This pattern is well documented in ML-based wastewater and hydrological studies, where model development generally prioritizes error minimization over interpretability [8,9]. Second, the design relevance of ML-based estimations has not been evaluated, and previous studies have rarely examined whether model outputs can support capacity determination or facility planning. Earlier ensemble-model research similarly lacked discussion on the engineering applicability of predicted influent loads [10,11]. Third, regional transferability remains largely unexplored, as models have typically been trained and validated within the same region without testing on unseen areas. Prior works have noted that most data-driven models show limited inter-regional generalizability unless validated across independent regions [12,13,14].

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the applicability of multivariate data-driven models for estimating regional influent loads as a basis for sewage treatment facility design. Using socioeconomic indicators such as total population, economically active population, number of business establishments, and gross regional domestic product (GRDP), ensemble regression models Random Forest (RF) and Voting Regressor were developed to represent the nonlinear relationships between regional characteristics and influent volume. The models were trained using datasets from four representative regions in Korea (Regions A–D) and subsequently validated on an unseen region (Region E) to assess their generalization performance.

By comparing estimation performance with the traditional unit-load approach and applying SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanations) analysis, this study identifies the key determinants of influent variability and provides a framework for rational capacity assessment and process design under uncertain operating conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Input Variable Framework

The proposed model in this study was developed using datasets from four representative regions in Korea (Regions A–D) with the objective of estimating sewage generation (SG). The variable composition was designed not only to move beyond a simple population-based approach but also to reflect the influence of socioeconomic activities, industrial structures, and regional economic levels on sewage generation, as summarized below.

Dependent variable: sewage generation (SG).

Independent variables: Total population (PP), number of business establishments (BE), economically active population (NP), waste generation (WG), rainfall (RF), and gross regional domestic product (GRDP).

In addition, unit sewage generation (GU) was included as a comparative indicator based on the conventional per capita unit-load method [15].

The data used in this analysis were collected from the Korean Government Public Data Portal. During data preprocessing, numerical variables were selected, and a hierarchical clustered heatmap was generated to identify the structural relationships among variables and to visualize their mutual similarity and clustering patterns [16]. For variables with high correlation coefficients, a network-based visualization was additionally applied to explore potential multicollinearity and possible interaction effects among variables [17].

2.2. Prediction Framework and Experimental Design

This study utilized annual observations from 2017 to 2023 for all regions (A–D), resulting in seven data points per region. Although the dataset is limited in length, the socioeconomic indicators used as predictors exhibit strong structural trends over time, enabling the models to capture meaningful regional patterns even with small sample sizes.

The research procedure consisted of four stages: exploration, visualization, prediction, and evaluation. In the exploration stage, correlation analysis and variable network mapping were performed to identify interrelationships and grouping patterns among the independent variables. The baseline of unit sewage generation (GU) was pre-calculated in advance to allow direct comparison with the predicted results. The per capita unit-load (GU) values were calculated following the Korean Ministry of Environment’s Guidelines for Sewage Treatment Facility Design. Annual GU was computed as the product of the standard per capita sewage generation coefficient (L/person·day) and the total population of each region. This served as the baseline model for comparison with the multivariate machine-learning estimations.

In the visualization stage, a dual-axis time-series graph was employed to intuitively compare long-term trends, abrupt changes at specific time points, and over- or under-predicted intervals [18]. This approach facilitated a clear understanding of both temporal continuity and local deviations within the prediction outcomes. In the prediction stage, four regions were analyzed independently to preserve regional characteristics. Model training was conducted only for the years in which sewage generation (SG) was observed, and predictions were produced for all years within the same region. The same set of variables—total population (PP), business establishments (BE), economically active population (NP), waste generation (WG), rainfall (RF), and gross regional domestic product (GRDP)—and identical learning procedures were applied to all regions to ensure fairness and reproducibility of results [19].

In the evaluation stage, the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean squared error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE) were used as performance metrics [20]. All metrics were calculated from the same observation-year samples to enable a fair comparison between the unit-load approach (GU) and the multivariate model.

2.3. Model Configuration, Tuning, and Learning–Evaluation Pipeline

2.3.1. Model Description

In this study, the Random Forest (RF) and Voting Regressor (VR) methods were adopted to estimate regional sewage generation (SG) based on multiple contextual variables. All statistical analyses and machine-learning modeling were conducted using Python 3.10 (Python Software Foundation).

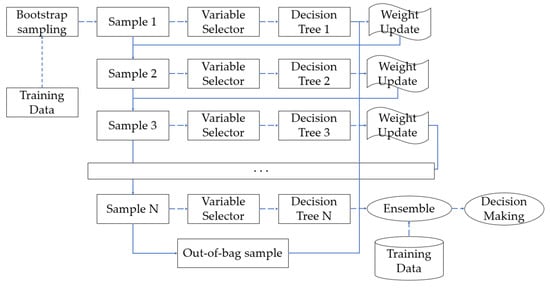

The Random Forest algorithm constructs an ensemble of multiple decision trees and aggregates their outputs. This approach effectively captures nonlinear relationships and demonstrates strong robustness against outliers and changes in the distribution of input variables (Figure 1) [21].

Figure 1.

Random Forest model structure.

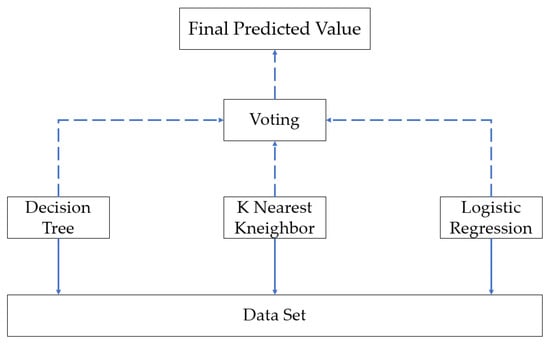

The Voting Regressor method (Figure 2) integrates the results of heterogeneous base models through either simple or weighted averaging. By combining different learners, this technique compensates for the bias of individual models and reduces the overall variance, thereby enhancing stability and generalization [22].

Figure 2.

Voting-based ensemble structure.

Both models used continuous independent variables such as year, gross regional domestic product (GRDP), total population (PP), number of business establishments (BE), economically active population (NP), waste generation (WG), and rainfall (RF). These variables were selected to reflect the structural, socioeconomic, and environmental factors influencing regional sewage generation [23].

2.3.2. Hyperparameter Tuning

To ensure the generalization performance of the model, key hyperparameters were systematically explored rather than fixed at default values, allowing sensitivity assessment. The tuning process was performed through 5-fold cross-validation within the training dataset [24]. A combination of grid search and random search methods was applied within rationally constrained parameter ranges determined through literature review and preliminary tests [25]. Random seeds were fixed to guarantee reproducibility. Considering the limitations of time and data, excessive hyperparameter searches were avoided, and the same tuning procedure was applied to all regions for fair comparison.

For the Random Forest (RF) model, the following parameters were incrementally examined: the number of trees (n_estimators), maximum tree depth (max_depth), minimum samples for node splitting (min_samples_split), minimum samples per leaf (min_samples_leaf), feature selection criterion (max_features), split criterion (criterion), and the use of bootstrapping. The number of trees was adjusted gradually to balance the increased variance at small values and the computational cost at large values. The max_depth parameter was tested under both unlimited and restricted settings to assess overfitting risk. Additionally, configurations with slightly increased min_samples_split and min_samples_leaf values were evaluated to mitigate noise learning. For max_features, three strategies ‘sqrt’, ‘log2’, and continuous fractions (0.6–1.0) were compared to assess the bias–variance trade-off [26].

For the Voting Regressor (VR), since it combines outputs from multiple models, the focus was placed on the effect of the weight vector on overall estimation stability. Each individual model used fixed, pre-tuned parameters for consistency. Both equal weighting and non-equal weighting schemes were evaluated using cross-validation, and the combination yielding the lowest average RMSE was selected (Table 1).

Table 1.

Final hyperparameters used for the Random Forest and Voting Regressor models.

2.3.3. Learning and Evaluation Pipeline

To ensure the reliability and practical applicability of model predictions, this study designed a comprehensive pipeline encompassing data partitioning, model training, cross-validation, and performance evaluation [27]. The focus was placed on establishing a structural framework that guarantees regional comparability and real-world applicability of the results.

The dataset was independently constructed for each region, and model training was performed separately using regional sewage generation (SG) data. Predictions were then generated for the entire time span. Stable performance was verified across specific years and intervals. Given the limited sample sizes in some regions, the validation folds were designed to be temporally dispersed, ensuring better generalization over time [28].

Three complementary performance metrics, the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean squared error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE), were used. R2 represents the explanatory power of predictions, while RMSE and MAE measure the magnitude and consistency of errors, enabling a multi-faceted evaluation of model behavior [29]. The goal was to validate predictive adequacy from diverse perspectives rather than relying on a single indicator. Based on the combination showing the most stable cross-validation performance, the final model was retrained using the entire dataset. This ensured fair comparison and reproducibility between predictive models while confirming their practical applicability. Considering the inclusion of multiple regions and temporal variability, the evaluation framework emphasized consistency and interpretability of performance measures.

2.4. Validation Framework Using an Unseen Region (Region E)

This section describes the validation framework designed to assess the inter-regional transferability and generalization capability of the proposed models. Model training was performed using data from four representative regions (Regions A–D), while an unseen region (Region E) was designated as an independent validation dataset under the same variable framework and learning procedure. The purpose of this design was to examine whether the trained models could be applied to a region with distinct demographic and industrial characteristics without relying on the statistical properties of the training regions.

The validation process was structured as follows. Optimal hyperparameters were determined using the integrated dataset from Regions A–D, and the final models were trained accordingly. Subsequently, the trained Random Forest (RF) and Voting Regressor (VR) models were directly applied to the independent dataset of Region E without additional retraining or parameter adjustment.

Model performance was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), in comparison with the conventional per capita unit-load (GU) approach to enable consistent performance benchmarking. This validation framework serves as a methodological component within the overall learning–evaluation structure, ensuring both regional independence of data and reproducibility of the evaluation environment.

3. Results

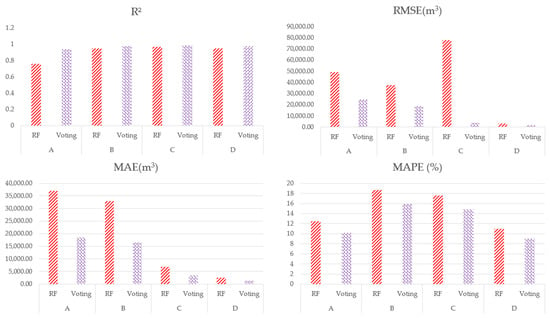

3.1. Evaluation Metrics

To quantitatively compare the performance of different models, this study constructed a common reference dataset by integrating sewage generation (SG) data from the four regions. The Random Forest (RF) model, Voting Regressor (VR), and the traditional per capita unit-load (GU) method were aligned to the same time periods for analysis [19]. The model evaluations were conducted based on three core performance metrics.

Table 2 shows the regional performance comparison results. Overall, the Voting model demonstrated the most consistent and stable performance. In terms of R2, it achieved the highest explanatory power in most regions, while RMSE and MAE values were the lowest, indicating reduced absolute and mean errors. In particular, in Regions B and D, the RMSE values decreased by nearly half, confirming the robustness and reliability of the Voting model. It is worth noting that Region C exhibited an unusually large gap between RMSE (≈77,700) and MAE (≈6800) for the RF model. This discrepancy is primarily caused by a single-year structural increase in sewage generation observed in Region C, which generates an extreme deviation that disproportionately inflates RMSE due to its squared-error formulation. In contrast, MAE being a linear metric remains influenced by the majority of years that show relatively small deviations. Thus, the RMSE–MAE gap reflects both the statistical sensitivity of RMSE to outliers and real-world conditions specific to Region C. This discrepancy indicates the presence of one or more extreme annual deviations that disproportionately inflate RMSE, which squares large errors, while most yearly errors remained relatively small as reflected by the lower MAE. The small sample size for Region C further amplifies the influence of such outliers. In contrast, the Voting model showed much smaller RMSE–MAE differences, demonstrating greater stability against extreme observations.

Table 2.

Regional Performance Comparison of RF, Voting, and GU Models Based on SG Estimation.

To ensure clarity and interpretability, visualization strategies were employed in conjunction with the numerical metrics. These included Taylor diagrams that simultaneously reflect standard deviation, correlation, and centered RMSE [30]; region-wise radar plots to display the relative performance of each model across R2, RMSE, and MAE; and scatter plots for modeled versus observed values [31].

As shown in Table 2, the Voting model displayed partially comparable results to the traditional per capita unit-load (GU) approach for specific indicators in certain regions.

The Random Forest (RF) model exhibited superiority in terms of mean absolute error (MAE) in some regions; however, it did not outperform the other models consistently across all three metrics. The Voting model was the primary modeling framework, while Random Forest outputs were used as supplementary references in cases where distinctive regional features were evident.

In this context, RMSE reflects the magnitude of large annual deviations because squared errors amplify the effect of peak anomalies, whereas MAE represents the average yearly deviation and is less sensitive to extreme values. Therefore, high RMSE with low MAE indicates the presence of one or two atypical years rather than consistent model inaccuracy.

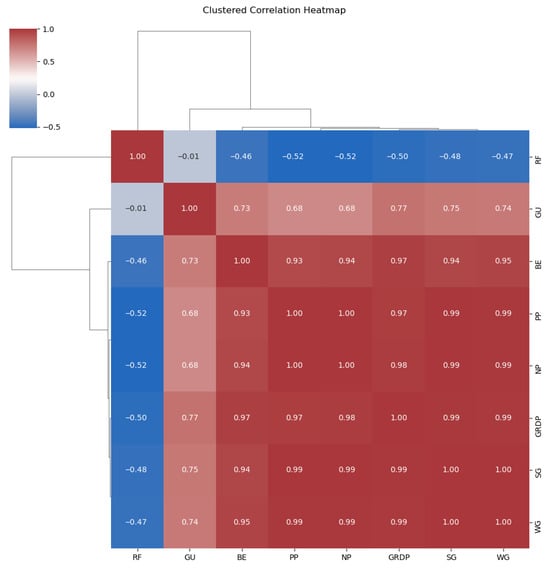

3.2. Correlation Analysis and Variable Interactions

This visualization (Figure 1) was included to justify the selection of input variables and to assess the underlying correlation structure prior to modeling, ensuring that the chosen predictors are conceptually coherent and statistically interpretable within the multivariate framework [32]. Figure 3 illustrates the degree of similarity and correlation among variables through color tones and the dendrogram branch patterns. In the upper-left cluster, rainfall (RF) and unit load (GU) are grouped together, while the right-side cluster includes the key variables sewage generation (SG), total population (PP), economically active population (NP), gross regional domestic product (GRDP), number of business establishments (BE), and waste generation (WG) densely connected. The cluster interiors are predominantly shaded in deep red tones, indicating generally high correlations across the variables. Strongest relationships are observed between SG–GRDP, SG–PP, and SG–WG pairs, while rainfall (RF) shows relatively weak correlations with other major variables [33]. In the dendrogram structure, RF and GU are separated first, followed by the formation of a single integrated cluster among the remaining variables [34].

Figure 3.

Clustered Correlation Matrix of SG and Input Variables.

These results indicate that several socioeconomic indicators particularly PP, NP, BE, and GRDP share extremely high pairwise correlations because they represent overlapping dimensions of regional demographic and economic scale. As such, multicollinearity is structurally unavoidable within these variables. Although multicollinearity does not degrade the performance of tree-based ensemble models used in this study, it has implications for interpretability. Because SHAP distributes contributions among correlated predictors, the importance attributed to PP, NP, BE, and GRDP should be interpreted as reflecting their shared influence on regional scale rather than independent causal effects.

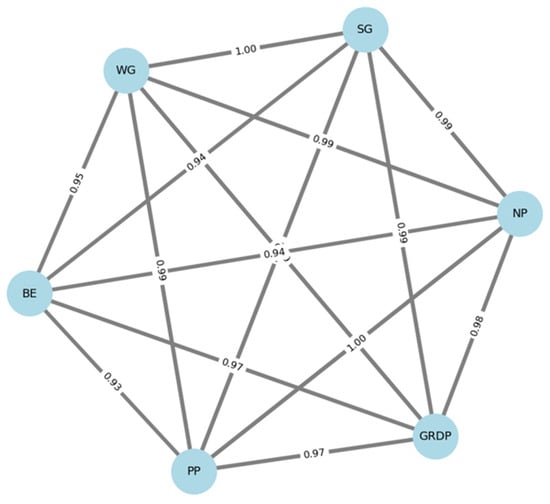

Figure 4 expands on this by providing a clustered correlation heatmap, quantifying the degree of linear association among variables [35]. It reveals that the correlations between explanatory variables (e.g., PP, NP, GRDP, BE, WG) are extremely high, typically exceeding 0.95. Sewage generation (SG) is also highly correlated with population-based and economic variables, confirming their relevance as predictors [36]. In contrast, rainfall (RF) and unit-load (GU) metrics show weak or negative correlations with the rest of the variables, reinforcing their peripheral placement in the hierarchical clustering. These findings justify the selection of contextual indicators (population, economic activity, and waste-related variables) as primary modeling inputs, while also explaining the relatively poor performance of the GU method in complex regional scenarios [10].

Figure 4.

Network Visualization of Inter-Correlations among Major Variables.

These findings provide three key insights:

- Variables related to population, economic activity, and industrial discharge exhibit strong interdependencies and direct correlations with sewage generation.

- Rainfall (RF) operates along an independent axis, functioning more as a short-term fluctuation factor rather than part of a long-term structural trend.

- The unit-load (GU) method generally follows the overall pattern but shows weak predictive precision. Therefore, an integrated multivariate modeling framework that captures variable interactions is required for accurate sewage estimation [10].

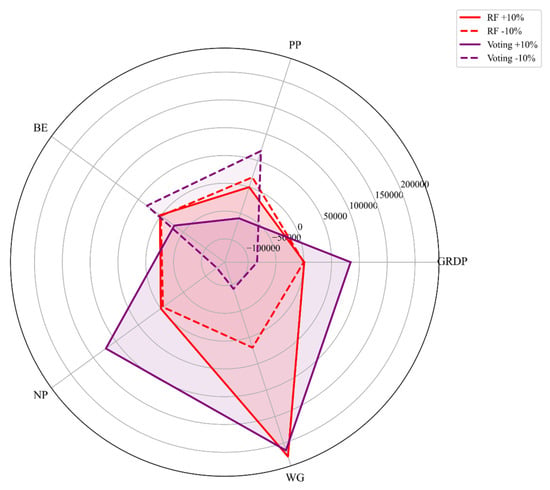

3.3. Scenario-Based Input Perturbation Analysis for Nonlinear Models

To quantitatively assess the influence of major independent variables on model predictions, this study conducted a what-if sensitivity analysis by applying ±10% variations to each variable [37]. Figure 5 illustrates the results of visualizing the changes in predicted sewage generation (SG) when five key variables (GRDP, PP, BE, NP, WG) are each altered by ±10%, using a radar chart centered on the first observation (row = 0) for a representative region. The analysis was conducted for both the Random Forest and Voting Regressor models. The magnitude of change can be comparatively assessed by the radial distance in the chart. The Random Forest (RF) results are shown in red solid lines (+10%) and dashed lines (−10%), while the Voting model results are displayed in purple solid lines (+10%) and dashed lines (−10%).

Figure 5.

What-If Sensitivity Analysis of Key Variables on Sewage Generation Predictions Using RF and Voting Models. Red solid/dashed lines represent the RF model under +10%/−10% perturbations, while purple solid/dashed lines represent the Voting Regressor under the same conditions.

The radar chart reveals that the WG (waste generation) variable exhibits the highest sensitivity overall; a ±10% change in this variable led to substantial variation in predicted SG values. Other variables such as NP (economically active population), BE (number of business establishments), and GRDP also showed moderate influence, whereas PP (total population) had a relatively limited effect [38].

Of particular note is that the predictive response to the same variable varied between models. For example, in the case of BE or NP, the RF model showed a relatively modest change, while the Voting model exhibited a larger fluctuation. This suggests that the Voting model, which integrates multiple base learners, may respond more sensitively to certain input variations [39].

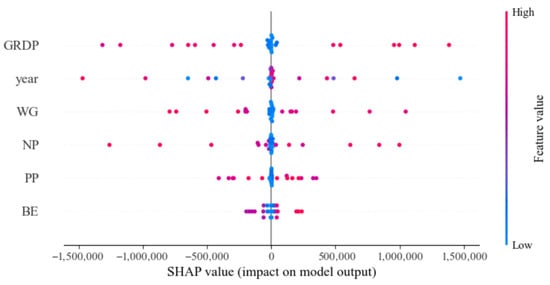

To conduct a sensitivity analysis, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values were used to evaluate feature importance and model interpretability [11]. Figure 6 presents the SHAP summary plot for the Voting Regressor model, visualizing the impact of each variable on model output. Each dot represents one observation, colored according to the value of the feature (from low to high). The horizontal spread indicates the magnitude and direction of influence on predicted SG.

Figure 6.

Tree SHAP for Voting Regressor summary plot showing the influence of each variable on the model output for sewage generation. Variables like GRDP and WG had the strongest impact, with color indicating the magnitude of each feature.

Notably, variables such as WG and NP not only exhibit high SHAP value ranges, confirming their dominant contribution to model output, but also reveal nonlinear effects where both high and low values can exert positive or negative influence depending on context [40]. Conversely, variables like BE and PP show relatively narrower SHAP spreads, aligning with the findings from the radar-based what-if analysis. This dual approach scenario-based perturbation and SHAP-driven interpretability provides complementary perspectives: the former emphasizes potential outcome sensitivity, while the latter focuses on actual attribution based on learned patterns, thereby offering robust grounds for policy interpretation and model transparency [22].

3.4. Comparative Analysis and Integrated Interpretation of Regional Prediction Results

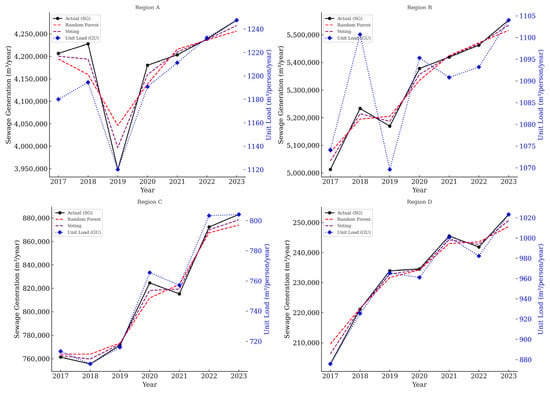

A regional comparison of sewage generation modeling performance revealed that both the Random Forest and Voting Regressor models consistently outperformed the traditional per capita (GU) estimation method. The degree of model responsiveness and accuracy varied depending on regional characteristics and trend volatility. Grouping regions by similarity in their temporal patterns enables a more systematic interpretation, as summarized below.

3.4.1. Regions with Trend Shifts and Abrupt Changes: Regions A and C

Regions A and C presented distinctive inflection points in sewage generation trends, offering a robust scenario to evaluate the adaptability of the models [41]. In Region A, sewage generation showed a sudden decline followed by a rapid recovery. Both models successfully accommodated these fluctuations. The Voting model, in particular, exhibited smoother transitions in both the downward and upward phases, while the GU method lagged in capturing trend reversals and frequently deviated from observed values due to over- or under-adjustments.

Region C experienced a sharp increase in sewage generation starting in 2020. Both models correctly captured the shift in level, and the Voting model’s results progressively converged with the actual values, achieving the closest alignment during 2022–2023 [12]. The GU approach followed the broad trend but overreacted to short-term fluctuations, leading to persistent overestimations during spike periods.

As shown in Figure 7, these patterns are visually evident. In Region A, the actual sewage output rebounded sharply after 2019, and both models successfully followed this change, whereas the GU method displayed delayed adjustment and diverged from the actual trajectory. In Region C, the Voting model gradually converged toward the observed trend, showing superior consistency during 2022–2023.

Figure 7.

Regional comparison of actual, model-based, and unit load (GU) sewage generation estimates from 2017 to 2023.

The what-if sensitivity analysis further revealed that variables such as waste generation (WG), economically active population (NP), and number of business establishments (BE) exerted a significant influence on the outputs in these regions. The Voting model exhibited greater variability in response to specific variable changes than the Random Forest, suggesting that the ensemble structure exhibits differentiated sensitivity to key drivers [42].

3.4.2. Regions with Gradual or Stable Trends: Regions B and D

Regions B and D exhibited relatively stable or gradually increasing trends in sewage generation, offering an appropriate basis for evaluating the robustness and long-term learning capacity of the models [43]. In Region B, the volume of sewage generated increased from 2017 to 2018, followed by a temporary decline in 2019, and then showed a consistent upward trend thereafter. Both models effectively smoothed these fluctuations and progressively narrowed the gap between the modeled and actual values. The Voting model, in particular, demonstrated a smoother response trajectory and yielded lower estimation errors than the Random Forest model throughout this period.

Region D maintained a steady upward trajectory in sewage generation without significant anomalies. Both models captured this trend effectively, with low error variance and high stability. The Voting model consistently outperformed the others in terms of accuracy and reliability [44]. As shown in Figure 8, these patterns are visually evident. In both Region B and Region D, the Voting model maintained a closer fit to the observed data compared to the GU baseline and Random Forest model, particularly during periods of minor fluctuation or continuous growth.

Figure 8.

Regional comparison of RF and Voting models across four performance metrics.

The results of the what-if sensitivity analysis further revealed that these regions exhibited smaller changes in model outputs in response to input variable perturbations. This suggests that the models successfully learned the underlying generation trends. The Voting model provided more balanced and stable responses than the Random Forest, maintaining alignment with observed values while minimizing unnecessary variability [45].

3.4.3. Quantitative Comparison by Region

Quantitative comparison based on performance metrics supports these findings. As shown in Table 2, the Voting model achieved the highest coefficient of determination (R2) across all regions, along with the lowest root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), particularly in regions with high variability [46]. The Random Forest model also performed well across regions, with only marginal differences from the Voting model in most cases [47]. Conversely, the GU-based estimation consistently showed lower explanatory power and significant prediction errors near inflection points. It either delayed its response or overreacted to shifts, thereby amplifying the deviation from actual values. These results highlight the structural limitation of a single-coefficient estimation method, which cannot flexibly capture temporal volatility or inter-variable interactions [48].

A deeper breakdown of model performance also revealed region-specific patterns. In Regions A and D, the Random Forest slightly outperformed the Voting model in terms of R2. Region B showed a clear advantage for the Voting model, while Region C exhibited negligible differences between the two. When considering RMSE, the Voting model consistently showed lower errors in Regions A, B, and D, while performance was nearly identical in Region C.

In terms of MAE (Table 2), the Voting model demonstrated lower or comparable error values in all regions, indicating robust accuracy. Given the multi-regional context, MAPE becomes especially important for assessing proportional error. Region A had larger absolute errors due to its overall high generation volume, but showed stable performance in percentage terms. Region B recorded the lowest MAPE among all, and Region C yielded the best overall prediction performance. Region D had the lowest RMSE but relatively higher MAPE, likely due to its smaller volume of generation.

3.4.4. Integrated Interpretation

In summary, the integrated interpretation of what-if sensitivity analysis (Figure 5) and modeling outputs confirms that multivariate machine learning models can effectively capture the complex structures and temporal dynamics of sewage generation. Among them, the Voting Regressor exhibited both high adaptability and computational stability through ensemble-based processing, serving as a robust tool for region-specific sewage planning and management.

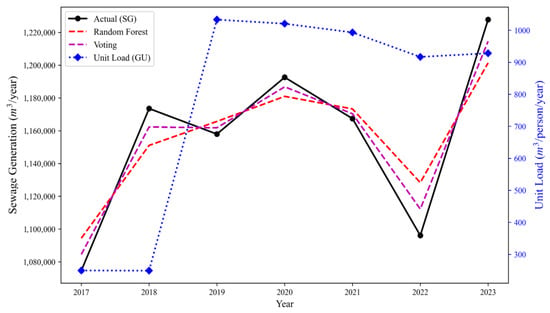

3.5. Generalization Performance Evaluation in a New Region (Region E)

To examine whether the model-based approach can be extended beyond prediction and serve as a foundational tool for estimating demand and designing sewage treatment facilities, a generalization performance test was conducted using Region E, which was excluded from the training dataset [13]. Figure 9 presents the time-series comparison of sewage generation (SG) against the estimates produced by the Random Forest model, the Voting Regressor, and the traditional unit-load (GU) method [14]. Table 3 shows the quantitative indicators R2, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE.

Figure 9.

Annual sewage generation trends in Region E calculated by Random Forest, Voting, and unit-load models (2017–2023).

Table 3.

Regional modeling performance of the Voting model based on R2, RMSE (m3), and MAPE (%).

Figure 9 Annual sewage generation trends in Region E calculated by the Random Forest, Voting, and unit-load (GU) models during 2017–2023. The figure illustrates the generalization performance of model-based approaches in an unseen region excluded from training, showing that both ensemble models capture temporal variations in sewage generation more effectively than the conventional unit-load method.

These findings suggest that machine learning-based multivariate models can serve as effective tools for future regional sewage infrastructure planning and demand estimation. In particular, the Voting Regressor, which integrates multiple base models, effectively accommodates inter-regional heterogeneity and demonstrates both predictive stability and high responsiveness [49].

Consistent with the regional analyses discussed earlier, this study confirms that the Voting-based approach can maintain strong explanatory power and reliability even when applied to unseen regions, underscoring its potential utility as a quantitative decision-making aid in sewage infrastructure development and expansion.

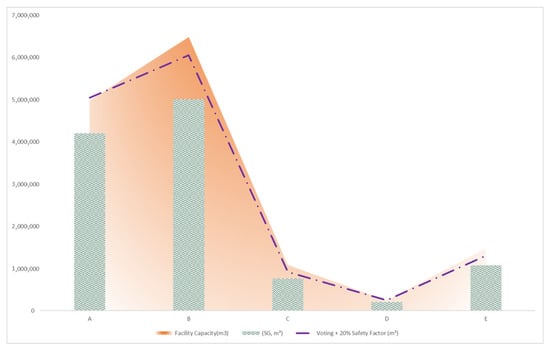

Figure 10 illustrates the comparative relationship among the mean annual sewage generation (2017–2023), the model-based estimated design capacity (Voting + 20% safety factor), and the existing facility capacity across the five study regions (A–E). The 20% safety factor applied in this study corresponds to the mid-range of the 10–30% design allowance commonly recommended in wastewater infrastructure guidelines and prior studies, reflecting standard engineering practice for accounting for temporal variability, data uncertainty, and potential socioeconomic growth. The chart reveals that, although the installed capacities are consistently higher than the observed sewage volumes, the magnitude of the overestimation varies substantially by region. Regions A and B, which correspond to highly urbanized areas with dense populations and strong economic activity, exhibit design capacities exceeding the model-derived values by approximately 10–20%. Conversely, in the relatively small-scale Regions C–E, the differences are considerably larger, indicating that the existing facilities were likely designed with overly conservative assumptions on per capita unit loads or future demand growth.

Figure 10.

Comparison of facility capacity, mean annual sewage generation (2017–2023), and model-based estimated capacity (Voting + 20% safety factor) by region.

The machine learning–based estimation incorporating a 20% safety factor produces capacity levels that remain within a realistic design margin for all regions. These results demonstrate that the proposed model is capable of quantitatively reproducing regional sewage generation characteristics while providing more balanced design criteria than conventional approaches. In particular, the inclusion of socioeconomic variables such as population structure, industrial density, and gross regional product allows the model to capture long-term behavioral trends that are typically ignored in traditional unit-load calculations. To account for model uncertainty, all model-based influent estimates were complemented with uncertainty ranges derived from cross-validation variability (mean ± one standard deviation). These ranges reflect the expected dispersion of model predictions under different training subsets and provide a more conservative basis for design-related interpretation. It should be noted that mean annual sewage generation is not equivalent to design loading, as facility design typically incorporates peak flow conditions such as seasonal maxima, rainfall-induced inflow, and short-term surges. The comparison performed in this study therefore reflects average operational loads rather than full peak design criteria [50].

Therefore, using the model-based capacity estimation (Voting + 20% SF) enables engineers and planners to determine facility sizes that are technically sufficient yet economically rational. This approach not only mitigates the risk of excessive design and underutilized infrastructure but also promotes data-driven decision-making for sustainable water infrastructure planning.

Table 4 presents the relative deviation of both the model-estimated and actual facility capacities from the observed sewage generation baseline (SG = 0%). The results reveal that the model incorporating a 20% safety factor provides a balanced and consistent margin across all regions, with deviations ranging from +6% to +21%. In contrast, the existing facility design capacities show wider variability, ranging from +4% to +34%, indicating that traditional design standards generally apply more conservative assumptions than are operationally required.

Table 4.

Region E modeling performance of the Voting model based on R2, RMSE (m3), and MAPE (%).

Table 5 demonstrates that region-specific comparisons further substantiate this observed pattern. Regions A and B showed only marginal differences between the model-based estimations and the actual capacities, suggesting that the Voting + 20% SF model effectively represents realistic facility sizing in densely populated urban contexts. However, in Regions C and E, the actual facility capacities exceed the model-estimated design load by more than 15%, implying potential over-sizing caused by outdated or generalized design coefficients. Conversely, Region D shows the smallest deviation, demonstrating that the model’s estimation can capture even low-volume regional dynamics with adequate accuracy.

Table 5.

Relative deviation of model-estimated and actual facility capacities from the observed sewage generation (SG = 0%) across regions.

Overall, these findings confirm that the proposed model not only reproduces the general magnitude of facility demand but also delineates regional variability more rationally than conventional per capita design methods. By explicitly quantifying the deviation from the actual sewage generation, the Voting-based estimation framework offers a data-driven standard for determining appropriate design margins preventing excessive over-design while maintaining sufficient reserve capacity for operational stability.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that multivariate ensemble learning can serve not only as a data-driven estimation tool but also as a framework that offers engineering-relevant insights for sewage infrastructure planning. Several important implications emerge from the findings.

First, the results confirm that sewage generation in urban regions is governed by joint socioeconomic dynamics rather than population alone. While previous studies typically emphasized predictive accuracy, the present work highlights how model outputs can be interpreted in the context of facility design. The integration of variables such as business establishments, economically active population, and GRDP revealed structural patterns that are concealed in traditional coefficient-based methods, providing a basis for evaluating whether current design capacities reflect real demand conditions. This aligns with the increasing need for adaptive infrastructure planning under demographic change and economic restructuring. The pronounced discrepancy between RMSE and MAE in Region C further highlights the role of short-term structural changes in influencing model evaluation metrics. The sharp increase in sewage generation after 2020 created an isolated spike that the models captured, but this single anomaly magnified RMSE significantly while having minimal impact on MAE. This indicates that RMSE can overrepresent infrequent but large deviations, whereas MAE more accurately reflects the dominant year-to-year error structure, reinforcing the need to interpret both metrics jointly when assessing regional model performance.

Second, the SHAP-based interpretability analysis indicates that the influence of key variables operates through shared regional characteristics rather than isolated causal effects. This finding has practical significance: design engineers can use attribution ranges to understand which socioeconomic sectors contribute most to inflow variability and which factors may amplify uncertainty under future growth scenarios. Moreover, the perturbation-based scenario exploration complements SHAP by quantifying how modest changes in individual drivers can propagate into capacity requirements, thereby supporting risk-aware decision-making.

Third, the generalization test in Region E demonstrates that the proposed framework can maintain robustness even when applied to unseen regional contexts, which is essential for developing scalable, multi-regional design tools. The ability to transfer structural relationships across regions suggests that a unified modeling platform could support national-level planning, particularly in areas lacking long-term flow monitoring data.

Fourth, the comparison between model-based capacity estimation and existing facility capacities suggests that some treatment plants may have been over-designed due to the reliance on static per capita coefficients. While this study does not aim to replace regulatory design standards, the results provide a quantitative basis for re-evaluating safety margins—particularly in regions where conservative assumptions lead to inefficiencies in capital cost allocation and operational energy use.

Finally, the study highlights several methodological considerations for future work. Expanding the dataset to include climate-driven inflow anomalies, industrial discharge profiles, and temporal indicators such as peak ratios would allow a more comprehensive assessment of uncertainty. In addition, integrating partial dependence analysis or model-agnostic residual diagnostics may further strengthen interpretability. As Korea’s design guidelines continue to evolve under climate-resilient infrastructure initiatives, combining regulatory coefficients with machine-learning-derived insights offers a promising hybrid direction for both research and practice. Overall, this study underscores the value of interpretable ensemble learning not simply as a forecasting tool, but as a decision-support system capable of improving design rationality, reducing structural overestimation, and enhancing regional comparability in modern sewage infrastructure planning.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed a data-driven framework for estimating sewage treatment facility capacities using machine learning models that integrate demographic, socioeconomic, and environmental indicators. By redefining the conventional population-based unit-load approach into a multivariate and nonlinear formulation, the proposed method provides a more realistic reflection of regional sewage generation behavior. This paradigm shift enables the design of sewage infrastructure to move from empirical assumptions toward evidence-based computation grounded in observed data patterns.

Unlike conventional design practices that rely on fixed coefficients or conservative unit-load factors, the proposed model dynamically adjusts the design allowance in response to local sewage generation characteristics. This adaptability makes it possible to determine design capacities that are technically sufficient without excessive oversizing, ensuring both operational stability and economic efficiency. In particular, by embedding the relationships among population structure, business activity, and regional economic growth, the framework identifies design margins that correspond closely with actual sewage generation dynamics.

From an engineering standpoint, this approach introduces a quantitative criterion for evaluating and calibrating design margins at regional scales. By directly linking the estimated facility capacities to measurable socioeconomic variables, it provides planners and decision-makers with a transparent and reproducible method for assessing whether existing facilities are appropriately scaled or overdesigned. This not only reduces unnecessary capital expenditure but also supports long-term sustainability in infrastructure investment and management.

The broader implication of this work lies in integrating machine learning into the design phase of sewage infrastructure planning. The results demonstrate that statistical modeling can evolve from being merely predictive to serving as a practical tool for rational design decision-making. Additionally, coupling the model with optimization and simulation tools may enable real-time capacity planning and policy-oriented applications, reinforcing its role as a cornerstone for data-driven and adaptive infrastructure design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-S.L., C.-H.K., and D.-C.S.; methodology, J.-S.L. and C.-H.K.; software, J.-S.L.; validation, J.-S.L. and D.-C.S.; formal analysis, J.-S.L., C.-H.K., and D.-C.S.; investigation, J.-S.L. and C.-H.K.; data curation, C.-H.K.; visualization, J.-S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-S.L.; writing—review and editing, D.-C.S.; supervision, D.-C.S.; project administration, D.-C.S.; funding acquisition, D.-C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a Korea Agency for Infrastructure Technology Advancement (KAIA) grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport’s DNA+ Convergence Technology Specialized Graduate School Development Project; Project number: RS-2025-00260001).

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained from official governmental databases, including the Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS) and the Korea Environment Corporation (K-eco). According to the Act on the Provision and Use of Public Data and the data providers’ terms of use, redistribution of these datasets is not permitted. Therefore, the datasets cannot be shared directly. However, the same data can be accessed from the original sources, and the authors can provide the official access links upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Gao, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Q. Climate change impacts on wastewater infrastructure: A systematic review and typological adaptation strategy. Water Res. 2023, 242, 120282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Barberá, A.; Iserte, S.; Castillo, M.; Luis-Gómez, J.; Martínez-Cuenca, R.; Monrós-Andreu, G.; Chiva, S. Machine Learning-Based Forecasting of Wastewater Inflow During Rain Events at a Spanish Mediterranean Coastal WWTPs. Water 2025, 17, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, J. Model-Based Construction of Dynamic Influent Loads for Wastewater Treatment Plant Simulations. Water 2024, 16, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Ministry of Environment. Guidelines for Sewage Treatment Facility Design; Korean Ministry of Environment: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021; Available online: https://kosis.kr/index/index.do (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Kim, K.; Kang, M.S.; Song, J.H.; Park, J. Estimation of LOADEST coefficients according to watershed characteristics. J. Korea Water Resour. Assoc. 2018, 51, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, C.; Lescop, B.; Nguyen-Vien, G.; Rioual, S. The Deutsches Museum Spacesuit Display: Long-Term Preservation and Atmospheric Monitoring. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, S.D.; Ryan, P.; Nuyts, S.; Nolan, P.; Clifford, E. Impacts of Projected Future Changes in Precipitation on Wastewater Treatment Plant Influent Volumes Connected by Combined Sewer Collection Systems. Climate Serv. 2024, 35, 100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourani, V.; Elkiran, G.; Abba, S.I. Wastewater treatment plant performance analysis using artificial intelligence—An ensemble approach. Water Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 2064–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, F.B.; Li, J. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Models and Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Predicting Wastewater Treatment Plant Variables. Adv. Environ. Eng. Res. 2024, 5, 020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, L.C.C.; Turci, L.F.R.; Moura, R.B. Statistical Evaluation of Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Effluent at a University. Res. Soc. Dev. 2023, 12, e19112640515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.07874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhang, X.; Xie, J.; Zuo, G.; Luo, F.; Zhang, X.; Jin, T.; Yang, X. Prediction of Non-Stationary Daily Streamflow Series Based on Ensemble Learning: A Case Study of the Wei River Basin, China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2025, 39, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, R.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, X. Hydrological Prediction in Ungauged Basins Based on Spatiotemporal Characteristics. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0313535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabu, P.; Alluhaidan, A.S.; Aziz, R.; Basheer, S. AquaFlowNet: A machine-learning based framework for real-time wastewater flow management and optimization. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesdaghinia, A.; Nasseri, S.; Mahvi, A.H.; Tashauoei, H.R.; Hadi, M. The estimation of per capita loadings of domestic wastewater in Tehran. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2015, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancusa, V.M.; Trusculescu, A.A.; Constantinescu, A.; Burducescu, A.; Fira-Mladinescu, O.; Manolescu, D.L.; Traila, D.; Wellmann, N.; Oancea, C.I. Temporal Trends and Patient Stratification in Lung Cancer: A Comprehensive Clustering Analysis from Timis County, Romania. Cancers 2025, 17, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzenfrei, R. Using complex network analysis for water quality assessment in large water distribution systems. Water Res. 2021, 201, 117359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.; Costa, M. A Time Series Model Comparison for Monitoring and Forecasting Water Quality Variables. Hydrology 2018, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Shin, D.-C. Prediction of Waste Generation Using Machine Learning: A Regional Study in Korea. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Jurman, G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgiu, M.; Drăguţ, L. Random Forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 114, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, R.; Kumar, A.; Priyadharsini, C.; Naik, M.M.; Choudhury, M.; Khan, N.A. Predicting Water Quality Index Using Stacked Ensemble Regression and SHAP-Based Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Sun, G.; Zhang, H. Does Urban Economic Development Increase Sewage Discharge Intensity? A Case Study of 288 Cities in China. Water 2025, 17, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.-T. Performance evaluation of classification algorithms by k-fold and leave-one-out cross-validation. Pattern Recognit. 2015, 48, 2839–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, F.; Prieto, C.; Álvarez, C. Hyperparameter optimization of regional hydrological LSTMs by random search: A case study from Basque Country, Spain. J. Hydrol. 2024, 626, 132003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, P.; Wright, M.N.; Boulesteix, A.-L. Hyperparameters and tuning strategies for random forest. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2019, 9, e1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, Y.; Song, G.; Lee, J.; Cho, M. Deep learning methods for predicting tap-water quality in a large water supply system: A nationwide dataset in South Korea. Water 2022, 14, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Liu, X.; Igou, T.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y. Using Hybrid Machine Learning to Predict Wastewater Effluent Quality and Ensure Treatment Plant Stability. Water 2025, 17, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, T.; Draxler, R.R. Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE)?—Arguments against avoiding RMSE in the literature. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014, 7, 1247–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.E. Summarizing multiple aspects of model performance in a single diagram. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2001, 106, 7183–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, N.L.; Sahoo, M.; Biwalkar, N. Machine learning approaches for assessing groundwater quality and its implications for water conservation in the sub-tropical capital region of India. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2025, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, Z.; Horvat, M.; Pastor, K.; Bursić, V.; Puvača, N. Multivariate analysis of water quality measurements on a river reach of the Danube River. Water 2021, 13, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Eils, R.; Schlesner, M. Complex heatmap visualization reveals patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2847–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, J.; Liu, W.; Pan, Z.; Ling, K. Comparative Study of Hydrochemical Classification Based on Different Hierarchical Cluster Analysis Methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasaruddin, N.; Masseran, N.; Idris, W.M.R.; Ul-Saufie, A.Z. A SMOTE-PCA-HDBSCAN approach for enhancing water quality classification in imbalanced datasets. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 97248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.R.; van Vliet, M.T.H.; Qadir, M.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Country-level and gridded estimates of wastewater production, collection, treatment and reuse. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasić, M.V.; Awoyera, P.O.; Fadugba, O.G.; Barišić, I.; Netinger Grubeša, I. Advanced Machine-Learning Models for the Prediction of Ceramic Tiles’ Properties During the Firing Stage. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, K.J.; Kimes, R.V. Empirical characterization of Random Forest variable importance measures. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2008, 52, 2249–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarela, M.; Jauhiainen, S. Comparison of Feature Importance Measures as Explanations for Classification Models. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Li, D.; Sun, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, B. Unraveling Nonlinear Effects of Environmental Features on Urban Vitality: A SHAP-based Machine Learning Approach. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 81451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghakouchak, A.; Cheng, L.; Mazdiyasni, O.; Farahmand, A. Global warming and changes in risk of concurrent climate extremes: Insights from time series analysis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 8847–8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, F.U.; Khan, A.U.; Khan, A.W.; Ullah, B.; Khan, M.R.; Javed, I. Comparative Analysis of Ensemble Learning Algorithms in Water Quality Prediction. J. Hydroinform. 2024, 26, 3041–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.K.; Munmun, T.H.; Paul, C.R.; Haque, M.P.; Al-Ansari, N.; Mattar, M.A. Improving Forecasting Accuracy of Multi-Scale Groundwater Level Fluctuations Using a Heterogeneous Ensemble of Machine Learning Algorithms. Water 2023, 15, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Wang, B.; Chen, J.; Fan, Y.; Mo, R.; Xu, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Zhong, P.-A. An explainable ensemble deep learning model for long-term streamflow forecasting under multiple uncertainties. J. Hydrol. 2025, 636, 133968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zounemat-Kermani, M.; Batelaan, O.; Fadaee, M.; Hinkelmann, R. Ensemble Machine Learning Paradigms in Hydrology: A Review. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.J.; Matsuura, K. Advantages of the mean absolute error (MAE) over the root mean square error (RMSE) in assessing average model performance. Clim. Res. 2005, 30, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, G.; Yassine, G.; Hamza, B.; Tachi, S.E.; Hasnaoui, Y.; Ammar, M. Assessment and prediction of irrigation water quality using machine learning techniques: A case study from the Bouhamdane Basin, Guelma Region, Eastern Algeria. Water Supply 2025, 25, 1465–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulfotoh, A.; Heikal, G. Estimation of Per Capita Loading and Treated Wastewater Quality Index in Sharkia Governorate, Egypt. J. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 23, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Zhang, R.; Jian, Z.; Liu, W.; Sun, T.; Pang, W.; Han, L.; Qin, H. Using Ensemble Machine Learning to Predict and Understand Spatiotemporal Water Quality Variations across Diverse Watersheds in Coastal Urbanized Areas. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 113976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lin, M.; Feng, Y. Improved grey water footprint model based on uncertainty analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).