Abstract

The transition towards a circular bioeconomy drives the search for sustainable valorization routes for agricultural waste streams. In this context, lignocellulosic residues from avocado tree prunings (Persea americana Mill.), with a reported high extractives content, represent a promising resource for pyrolytic valorization; however, their thermal behavior remains scarcely studied. This work characterized the chemical composition of whole branches (including bark) by FTIR and evaluated thermal degradation by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) at five heating rates (10–30 °C/min) in an inert atmosphere. Kinetic analysis of the TGA data employed Friedman, FWO, KAS, Coats–Redfern, and Kissinger models. The Avrami model determined a reaction order of n ≈ 0.28. Among the methods, Coats–Redfern, applied with this n, provided the most consistent description, achieving the best average fit (R2 ≈ 0.9878) and the narrowest range of pre-exponential factors (1012–1016 s−1). The Friedman model showed greater dispersion (1012–1022 s−1). Average activation energies ranged from 185 to 210 kJ/mol (Kissinger: 171.3 kJ/mol). The thermodynamic parameters confirmed a non-spontaneous, endothermic process (ΔH = 166.4–205.9 kJ/mol; ΔG = 178.8–179.8 kJ/mol). The entropy change (ΔS from –33.8 to 194.1 J/mol·K) reflects the complex solid-to-volatiles transition during pyrolysis. This study establishes a tailored kinetic framework for avocado branch pyrolysis, providing a reliable kinetic description for this biomass and identifying the Avrami–Coats–Redfern method as the most suitable for its accurate modeling.

1. Introduction

Agroindustries in Mexico produce significant volumes of lignocellulosic residues, but valorizations of this material are currently limited or null, especially for prunings from fruit trees. Inadequate disposal of these residues raises operating costs and contributes to environmental contamination [1,2]. Among these residues, those derived from avocado cultivation (Persea americana Mill.) stand out due to their volume and economic importance, since Mexico is the world’s largest producer with over 268,000 hectares planted, according to Mexico’s Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera (SIAP) [3]. Regular prunings generate lignocellulosic biomass that constitutes a potential resource for evaluating thermochemical processes, such as pyrolysis, with the goal of obtaining biocarbon, biooils, and combustible gases [4,5].

Previous studies have focused on byproducts of P. americana like seeds [6], but its woody residues present differentiated chemical and structural compositions characterized by a higher proportion of lignocellulose and lower extractive content. These properties suggest a more stable, homogeneous thermochemical behavior that makes them especially adequate for obtaining high-quality biochar, though this constitutes only one possible route of valorization, so it is necessary to explore other alternatives for products derived from thermochemical transformation.

Despite pyrolysis’ high potential for valorizing lignocellulosic residues, implementation on an industrial scale faces technical and economic limitations, such as low product yield and high operating costs. These restrictions underscore the need to optimize both the design of reactors and their operating conditions, based on reliable experimental data to improve process efficiency [7,8,9]. Other significant challenges for industrial scaling are the intrinsic variability of the physicochemical properties of biomass and the lack of standardized experimental procedures.

In this context, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) complemented by its derivative (DTG), constitutes a fundamental tool for characterizing the thermal stability of biomass, identifying the stages of degradation, and determining critical process temperatures [10]. Data obtained through TGA–DTG make it possible to estimate the essential kinetic parameters of thermal degradation; namely, activation energy (Ea), which represents the energy barrier of the reaction, the pre-exponential factor (A) that reflects the frequency of molecular collisions with an adequate orientation, and the reaction order (n), which describes the relation between the reaction velocity and degree of conversion, thus mirroring the complexity of the entire process [4,11,12]. Although the experimental conditions for TGA do not reproduce the heating rates or thermal regimens of industrial processes, results constitute an essential tool for understanding thermal stability, the stages of degradation, and the kinetic dynamics of lignocellulosic materials. This experimental information also supports the application of kinetic focuses for analyzing and modeling thermal degradation processes.

Researchers in this field have developed iso-conversional kinetic methods, like the Friedman, Flynn–Wall–Ozawa (FWO) and Kissinger–Akahira–Sunose (KAS) approaches, that do not require assuming a specific reaction model [13], as well as non-iso-conversional methods (Kissinger, Coats–Redfern), which do assume a defined reaction model and are recognized as providing reliable estimates of kinetic parameters [14]. Avrami’s model is widely used to describe the reaction kinetics of heterogeneous materials [15]. Our work team has applied it recently in thermal analyses of woody biomass from Ceiba aesculifolia [12]. It is important to note, finally, that the Coats–Redfern method has shown reliable adjustment with distinct biomasses, including woody ones [16,17,18].

Thermodynamic analysis complements kinetic characterizations by providing information on the energy and viability aspects of the process. Parameters like activation enthalpy (ΔH), Gibbs free energy (ΔG), and entropy (ΔS) allow us to evaluate the energy efficiency and spontaneity of reactions [19]. Integrating this with kinetic data, as recommended, ensures a more complete characterization of the thermochemical behavior of biomass [20].

In light of its reported composition, which includes relatively high extractives content, a detailed investigation of the pyrolysis kinetics of this specific biomass is warranted. The present study was conceived to characterize the woody residues of P. americana by FT-IR spectroscopy to identify the predominant functional groups and evaluate their thermal behavior during pyrolysis using TGA and DTG at five heating rates. These data were used to determine kinetic and thermodynamic parameters in order to provide rigorous technical information that supports the valorization of this residual biomass as a renewable resource in thermochemical processes.

To establish the technical foundation for this valorization pathway, this study focuses on P. americana pruning residues—an abundant yet under-characterized biomass whose reported composition, including a relatively high extractives content, may distinctly influence its thermal decomposition. Consequently, this work aims to characterize the biomass’s functional groups via FT-IR spectroscopy, analyze its thermal degradation behavior using TGA/DTG at multiple heating rates, and determine the associated kinetic and thermodynamic parameters. This integrated analysis provides the rigorous data necessary to support the efficient valorization of this residual biomass as a renewable resource in thermochemical processes.

2. Materials and Methods

The sample materials were gathered after pruning in six orchards in the municipality of Salvador Escalante, Michoacán, Mexico. During collection, the branches—the principal fraction of interest—were separated and the leaves discarded. Branches were analyzed with their bark to reflect the typical composition of pruning waste. The selected material was transported to the laboratory for pre-drying, followed by grinding in a model K20F mill (Micron S.A. de C.V., Mexico) and sieving through a ROTAP device (model RX-29, W.S. Tyler, U.S.) equipped with a standard ASTM No. 40 mesh (425 µm). The physicochemical properties of the woody fraction of prunings of P. americana have been determined previously [21]. Table 1 shows the results of that characterization.

Table 1.

Reference data for avocado pruning branches from a previous study by Soria-González et al. [21], including higher heating value, proximate analysis, elemental composition, and basic chemical composition.

2.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

The functional characterization was conducted by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy in transmission mode, using a Spectrum 400 spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Samples of P. americana were dried at 105 °C for 24 h, pulverized, and mixed with potassium bromide (KBr) to form pellets. Spectra were recorded in the interval of 4000–500 cm−1, at a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 16 scans per sample.

2.2. Thermal, Kinetic, and Thermodynamic Analyses

2.2.1. Thermal Analysis (TGA–DTG)

The ground, sieved samples of biomass were dried to a constant weight at 105 °C, then stored in hermetic recipients. TGA was performed on an STA 6000 analyzer (PerkinElmer Inc., USA). Samples (30 ± 5 mg of dried material) were analyzed in triplicate in a 99.99% N2 atmosphere. The sample mass used here exceeds the amount typically recommended to minimize the influence of transport phenomena on the reaction rate. It was chosen to ensure a representative signal, which leads to the determination of apparent kinetic parameters that represent the effective global behavior of the system. The flow rate was 30 mL/min, adjustable according to the heating velocity. The thermal program consisted in heating from room temperature (~25 °C) to 900 °C with a final isotherm of 10 min, at five speeds: 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 °C/min (10–30 K/min). The thermogravimetric data (TGA) were processed with OriginPro (trial version) software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA) to generate the decomposition data of the biomass and its derivatives (DTG) and then represent them in graphs.

2.2.2. Kinetic Analysis

Kinetic parameters were determined on the basis of the TGA–DTG results using, initially, the Friedman, Flynn–Wall–Ozawa (FWO), Kissinger–Akahira–Sunose (KAS), and Coats–Redfern iso-conversional methods, as well as Kissinger’s non-iso-conversional approach, adjusted to the experimental data obtained at the five heating velocities (10–30 °C/min). The aim was to simultaneously estimate Ea and A under a defined reaction model. Later, Avrami’s model was applied to describe the reaction order (n). Graphs were generated in OriginPro, respecting the theoretical foundations and equations reported in the literature, as described in detail below.

To estimate the kinetic parameters, conversion (α) was determined on the basis of mass loss during pyrolysis, according to Equation (1) [22]:

where is the initial weight loss from the biomass, represents the weight loss at a specific temperature, and is the final weight of the biomass.

The kinetic models employed to determine these parameters are based on the general equation for the reaction velocity reported in the literature [22], as shown in Equation (2):

where is the change in the degree of advance with respect to time, is the pre-exponential factor, (s−1), Ea is the activation energy (kJ/mol), is the universal constant of the ideal gases, is the absolute temperature in Kelvin (), and represents the reaction model of the pyrolysis process.

Because the thermal decomposition of lignocellulosic biomass involves multiple reactions, it entails a multistep process. Vyazovkin et al. [13], however, hold that in a condensed phase process, the kinetics of multiple steps can approach with precision those of a one-step process. The challenge involved in identifying the reaction models intensifies when adjustment is made on experimental data obtained from a non-isothermal assay at a single heating velocity, β. Nonetheless, when the temperature varies lineally with time under non-isothermal conditions, Equation (3) can be applied:

Using this ratio, Friedman’s differential method [23]—described in Equation (4)—is initially based on Arrhenius’ modified equation. In this method, the dependence of time on the degree of conversion (dα/dt) from Equation (2) is replaced by the temperature/time ratio (dT/dt) from Equation (3). This allows for the derivation of an expression that uses different β values [22,23]:

To apply Friedman’s method, it is assumed that the function of the reaction mechanism f(α) remains constant for a fixed value of α. This approach did not require a predefined reaction model to calculate Ea from the data obtained by thermogravimetry (TGA–DTG) at the five heating rates. The general equation of Friedman’s method is derived by simplifying and applying the natural logarithm to both sides of Equation (4) to generate Equation (5) [22,23]:

Kissinger’s method [24] is a kinetic technique used to estimate Ea from the temperature that corresponds to the maximum reaction rate, or maximum peak, found in a thermogravimetric analysis at distinct heating rates. This focus does not require previous knowledge of the reaction mechanism, so it is especially useful for studying materials with complex structures. Estimates of Ea depend on the mathematical relation expressed in Equation (6), which represents the characteristic formulation of this method [22,24]. Ea is calculated from the slope of the straight line in the graph, which is equal to .

FWO is a widely used iso-conversional method, one of the first traditional integral approaches. Equation (7) presents the mathematical expression that describes FWO [4,25].

where is obtained by introducing the integral function of into Equation (5) to generate Equation (8), shown below [4,25]:

KAS is another iso-conversional method. It is a function of the integral of temperature expressed in Equation (9) [4,26]:

Avrami’s kinetic model [15] is used to determine the reaction order (n). The general formulation of this model was reported previously by Alvarado-Flores et al. [12]. It is expressed in Equation (10):

where k(T) is the temperature-dependent velocity constant and n is the reaction order. Equation (11) is obtained by applying double natural logarithms to the original equation and then performing an algebraic reorganization. Equation (11) is used experimentally to determine the parameter n, which corresponds to the reaction order:

Values of n are obtained by means of the graphic representation of against at a constant temperature.

Avrami’s model makes it possible to estimate the reaction order, n, which was used as the basis for applying Coats–Redfern’s integral method. This combination allowed us to estimate the dominant kinetic mechanism in the interval analyzed. In our work, we utilized the integral function g(α), shown in Equation (12), which corresponds to the reaction order calculated previously by adapting the normalized Coats–Redfern equation [27]:

where represents the integral function of the assumed kinetic model.

The experimental data obtained at five heating rates (10, 15, 20, 25, 30 °C/min) are represented graphically as against 1000/T. This procedure allowed us to evaluate the concordance of the model with the thermal behavior of the biomass and generate robust estimates of the kinetic parameters. To compare these findings to distinct β values in the thermogravimetric assays, the method was applied assuming a regimen of linear heating that explicitly incorporated the term β into the equation to normalize its effect and allow direct comparisons among different experiments. A model of order n was also assumed in accordance with earlier studies of woody biomass that have reported an adequate adjustment using this approach [17]. In addition, the integral function that corresponds to a model of the reaction order, n, was utilized with the expression in Equation (13):

where n corresponds to the estimated value achieved with Avrami’s model.

The decision to use the experimental value of the reaction order (n), derived from the Avrami model, made it possible to avoid assigning an arbitrary theoretical order and to maintain consistency between the adjusted parameters and the available experimental information. The methodological strategy included the parallel application of iso-conversional methods (FWO, KAS, and Friedman) and non-iso-conversional methods (Kissinger), together with the Coats–Redfern integral method, in accordance with the recommendations of the ICTAC Kinetics Committee, which suggest combining and comparing different approaches for the kinetic analysis of complex, multistep systems [20]. This integrated approach provides a solid basis for determining global and conversion-dependent kinetic parameters, avoiding dependence on a single model or prior assumptions.

Table 2 presents a summary of the kinetic methods applied and highlights their key features, including type of method, main assumptions, and the variables utilized to graph the data required to determine the kinetic parameters. It also displays an overview of the methods selected to analyze the thermal degradation of P. americana, described above.

Table 2.

Kinetic methods applied in this study (P. americana).

2.2.3. Estimates of the Thermodynamic Parameters

To estimate the thermodynamic parameters associated with pyrolysis, we applied transition state theory (Eyring’s theory), which makes it possible to calculate changes in enthalpy (ΔH), Gibbs free energy (ΔG), and entropy (ΔS) based on kinetic parameters obtained previously (Ea, A). This procedure is widely accepted in thermoanalytic studies of biomass [19,20]. Equations (14)–(16) are the mathematical expressions employed to perform this calculation:

where is the temperature at the maximum velocity of mass loss, is Boltzman’s constant (1.381 × 10−23 ), is the temperature, and is Plank’s constant (6.626 × 10−34 ).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

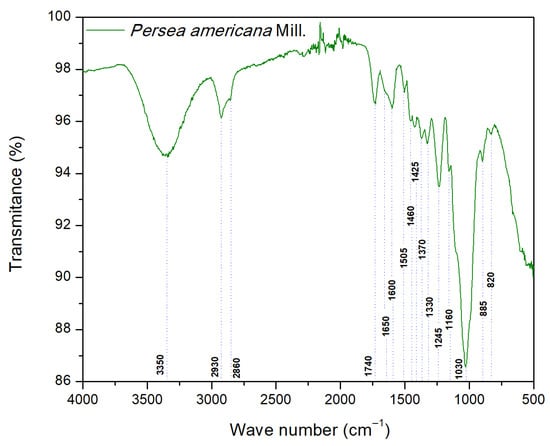

Figure 1 displays the FT-IR spectra with absorption bands assigned to the functional groups typical of lignocellulosic biomass.

Figure 1.

Fourier transform infrared spectra of Persea americana.

The FTIR spectra of branches of P. americana showed ample vibration coupled with medium-intensity signals in the 3700–2800 cm−1 region that evidence the presence of predominant O-H and C-H bonds. The broad, intense absorption identified around 3350 cm−1 corresponds to O-H stretching vibrations of hydroxyl groups in the alcohols, and carboxylic acids present in cellulose [28,29]. The 2930–2860 cm−1 region registered vibrations associated with C-H stretching of methyl and methylene groups [30,31], while around 2860 cm−1 a signal attributable to C–H vibrations of methylene groups was observed, which is particularly interesting, since in recent comparative studies consulted, this band was not reported for other woods such as Ceiba aesculifolia or Prosopis laevigata [12,32]. This absorption could be partly related to the content of certain extractable components in the biomass; relatively high levels of extractables (~17%) have been reported for P. americana [21] and other studies have identified compounds such as fatty acids (e.g., oleic and palmitic) in branches or other parts of the tree [33,34]. Nevertheless, given that this study did not include the characterization of these fractions, the possible link between the extractables and the band at 2860 cm−1 should be understood solely as an interpretation based on comparison with the recent references indicated above. The literature indicates that, in some biomass systems, lipid components can affect the onset of thermal degradation and the distribution of products in the early stages of the process [35].

The middle region of the spectra (1800–1300 cm−1) showed predominantly well-defined absorptions of high and moderate-to-low intensity that allowed us to distinguish specific contributions of lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose. The vibration at 1740 cm−1 was linked to C=O stretching of carbonyl groups, mainly associated with hemicellulose, reported between 1750 and 1720 cm−1 [28,29]. At 1650 cm−1, a low-intensity signal was observed and attributed to conjugated C=O, absorbed O-H, and conjugated C-O that, like the dominant signal recorded around 1600 cm−1, were associated with aromatic structures common in lignin [28]. The low-intensity absorptions at 1505 and 1460 cm−1 correspond, respectively, to skeletal aromatic vibrations of C=C of lignin and asymmetric deformations of -CH3 and -CH2 groups in hemicellulose and lignin [28,29,31].

At 1425 cm−1, we identified vibrations attributed to flexion vibrations of the CH2 group, associated primarily with structures in cellulose and lignin [29,31]. The absorptions at 1370 and 1330 cm−1, clearly differentiated as individual vibrations, were attributed to flexion CH2, symmetric C-H deformation (1370 cm−1), and C-H deformation and flexion on the C-O-H plane (1330 cm−1), mainly associated with cellulose and hemicellulose [28,29], but also related to lignin in the 1320–1316 cm−1 zone [28,36].

Observations for the 1245–820 cm−1 region showed well-resolved absorptions of variable intensity that allowed us to clearly identify contributions by hemicellulose (silane), cellulose, and lignin. The vibration at 1245 cm−1 was related to C-H flexions and C-O stretching in cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [12,31,32], while the signal at 1160 cm−1 was attributed to C-O-C stretching in pyranose rings and C-O stretching in cellulose and hemicellulose [29,31]. The strong vibration at 1030 cm−1 was characteristic of lignin, associated with C-H and C-O deformations [29,37]. A low-intensity vibration at 885 cm−1 was related to C-H vibrations in cellulose [29,31]. Finally, there was a vibration around 820 cm−1. These two results were associated with vibrations outside the C-H plane of lignin [28].

The FTIR analysis of the branches of P. americana confirmed the presence of the typical functional groups of woody lignocellulosic biomass, associated with cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, findings that are consistent with those reported for other woody biomasses. A signal was also observed around 2860 cm−1, which constitutes a distinguishing feature of this species according to the literature. This chemical particularity could impact the initial or intermediate stages of thermal degradation and the distribution of pyrolytic products, so it complements the interpretation of the results obtained through TGA-DTG and the kinetic and thermodynamic analyses.

3.2. Thermal, Kinetic, and Thermodynamic Analyses

3.2.1. Thermal Analysis (TGA–DTG)

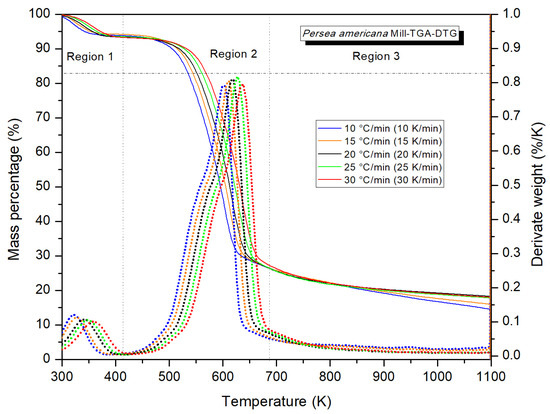

Figure 2 presents the TGA–DTG curves obtained at the five heating rates. For graphical clarity, the temperatures are shown in °C, while absolute temperatures in Kelvin were used in the kinetic analysis. Observations showed a progressive reduction in mass as temperatures increased, with a more pronounced loss between 250 °C and 380 °C. As the heating rate increased, the curves shifted toward higher temperatures, while the final residual mass showed an almost constant trend with slight variations among the different rates. A detailed examination of the DTG curves indicates that the residue was slightly higher at the lowest rate compared to the highest. Two well-defined peaks were identified in the DTG curves, characteristic of the thermal degradation of lignocellulosic biomass. They correspond to distinct stages of the decomposition of the principal components. The first one, between 26 and 150 °C, intensified at 30 °C/min and was related to moisture loss and the release of volatiles.

Figure 2.

TGA–DTG curves of Persea americana under N2 at different heating rates.

The second peak, broader and more intense, extended from 180 to 430 °C with more accelerated degradation between 330 and 380 °C. It was attributed to the decomposition of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin. In addition to the shift of the principal peak toward higher temperatures as the velocity increased, we observed a rightward horizontal movement of the curves.

The maximum degradation temperature (Tp) (Figure 2) increased with the heating rate, reflecting a thermal shift characteristic of processes limited by heat transfer. This behavior, consistent with studies of similar lignocellulosic biomasses, is often attributed to the lower availability of time for reactions to occur at low temperatures, as this demands higher temperatures to achieve an equivalent degradation [38]. The absence of widening of the DTG peaks suggests that the shifts respond mainly to thermokinetic phenomena that reflect a uniform thermal decomposition of the material with no evidence of fractions with differentiated behaviors. The overlap in the curves at 15 and 20 °C/min between 120 and 200 °C indicates that those thermal transformations had low dependence on the heating rate. This concurs with reports on similar lignocellulosic biomasses and reveals that the effects of β are more important in advanced stages of volatilization [38,39].

Figure 2 highlights three principal regions. Region 1 is characterized by a slight loss of mass, attributed mainly to the elimination of residual moisture and low-molecular-weight volatile compounds, including some extractables [40].

In region 2, the active phase of pyrolysis begins at around 200 °C and maintains a predominantly endothermic behavior up to 330–400 °C that corresponds to the decomposition of the structural components of the biomass [41]. Here, we observe the greatest mass loss, with a main peak that intensified between 315 and 360 °C and an inflexion in the DTG curve that shifted from 280 to 340 °C with increases in the heating rate. This reflects the active stage of pyrolysis. This behavior is related to the joint decomposition of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin, according to descriptions in the literature, where cellulose degrades predominantly between 250 and 380 °C, with a maximum near 345 °C, while lignin presents a wider range (200–500–527 °C) with a maximum around 400 °C [42,43,44]. In contrast to those reports, however, in the present study the greatest intensity of decomposition was determined for the interval 315–360 °C, indicating accelerated degradation of the structural components with intense molecular fragmentation. This stage, which is crucial for energy conversion, was characterized by the release of volatile compounds like condensable hydrocarbons, tars, and gases [45]. Kan et al. [35] pointed out that this is the range of greatest interest for examining the fundamental chemical mechanisms of the process. Osman et al. [46] added that the formation of unstable intermediates begins around 240 °C. Through dehydration and rupturing, they produce CO2, H2O, and CO. Those authors affirm that demethylation occurs at temperatures ˃300 °C with CH4 formation. This concurs with the observations in our work regarding the generation of volatile products and their contribution to syngas production.

Region 3 of the DTG curves shows a gradual degradation beginning at 400 °C, with less mass loss at high heating rates. This generates a relatively greater residual fraction and shows that part of the lignin does not decompose completely, so it fosters formation of carbonous residue. This tendency agrees with findings from earlier studies which state that the slow kinetics of lignin limit the release of volatiles and promote recombination reactions that generate carbon (char) with high superficial reactivity and notable thermal stability, associated with condensed aromatic networks [47,48]. Our work further identified tendencies that concur with those in Mishra & Mohanty [18], which suggest that lower heating rates foster the volatilization of organic compounds that could impact yields and the composition of biooil. Finally, this stage was characterized by condensation, dehydrogenation, and deoxygenation reactions that stabilized the char and strengthened its potential as a precursor of activated carbon [49].

The TGA–DTG analysis of the branches of P. americana evaluated at heating rates of 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 °C/min showed that active pyrolysis occurs primarily between 315 and 360 °C, the maximum decomposition peaks. At temperatures above 400 °C, degradation proceeds more slowly and fosters the formation of a stable carbonous residue. These results confirm the suitability of this biomass for thermochemical processes and the importance of controlling temperature and heating rate to optimize efficiency and the quality of the products obtained.

3.2.2. Kinetic Analysis

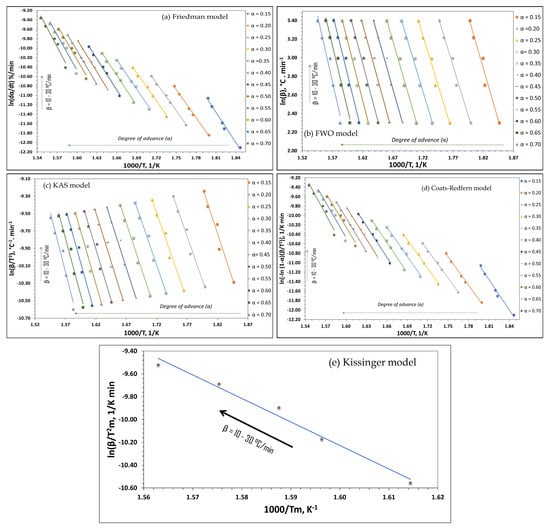

The kinetic analysis of P. americana was conducted using the thermoanalytic data, considering the conversion range α = 0.15–0.70, which corresponds to the principal stage of thermal decomposition where greatest mass loss occurs due to degradation of the predominant structural components (Figure 3). It is important to mention that one of the parameters that allows us to consider the calculation of activation energy and the pre-exponential factor, is the correlation coefficient (R2). In this research, we considered this parameter to be valid when it was above 0.95. In this sense, alpha (α) ranges lower than 0.15 and higher than 0.70 were not considered because the R2 value was very low. This range was selected because it represents the “active stage” of pyrolysis, where biomass decomposition allows for more representative kinetic parameters to be obtained. The initial and final stages were excluded because they present less uniform kinetic phenomena, which could introduce variability in the adjustments. This selection is consistent with recent studies on lignocellulosic biomass, where the kinetic parameters are more stable and suitable for modeling within this conversion range [11].

Figure 3.

Linear fittings obtained from the applied kinetic methods: (a) Friedman, (b) Flynn–Wall–Ozawa (FWO), (c) Kissinger–Akahira–Sunose (KAS), (d) Coats–Redfern and (e) Kissinger. Graphs (a–d) correspond to different degrees of conversion (α = 0.15–0.70) and heating rates (β), while graph (e) is based on Tmax at different β. Note: β values are expressed in °C/min. Calculations were performed using absolute temperature (K).

Results of the Friedman, FWO, KAS, Coats–Redfern and Kissinger (Figure 3a–e) kinetic methods confirm the applicability of each model to the biomass of P. americana since they generated reliable estimates of the kinetic parameters without assuming any specific reaction mechanism. The Friedman, FWO, and KAS methods produced shifts in the curves as conversion increased, reflecting the multistage nature of thermal degradation and progressive variations in Ea associated with the decomposition of the structural components of the biomass [19,50]. The curves for the intermediate conversion intervals are grouped, show less variation in Ea but a relatively constant behavior during high conversions. The graph of Kissinger’s method supports the finding that the principal reaction occurred during a dominant step. This allowed us to estimate Ea reliably within the velocity ranges analyzed.

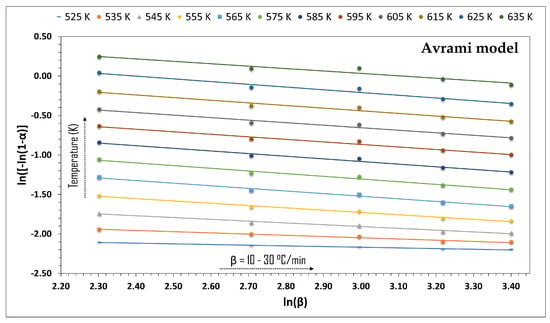

To present results of the application of Avrami’s model to the thermal degradation kinetics of the residues of the pruning of P. americana, Figure 4 shows the adjustment of the model to the TGA data in the range of ~252–362 °C. This range was selected because it corresponds to the stage with the greatest degradation of the structural components of the biomass, including hemicellulose, cellulose, and some of the lignin. The graph shows a well-defined linear relation between ln[−ln(1 − α)] and ln(β) for each temperature analyzed, and indicates an adequate correspondence of the model with the experimental data from pyrolysis for the distinct β values. This linear behavior suggests that, for the temperature range evaluated, the kinetics of the process can be described by a consistent mechanism with no significant changes in the type of reaction as temperature varied.

Figure 4.

Avrami model fitting to TGA data of P. americana pruning residues.

The analysis of Figure 4 shows that as the temperature increased, the values of ln[−ln(1 − α)] also increased at the same heating rate. This result confirms a greater thermal conversion of the biomass. The similar slopes of the straight lines suggest that the reaction order, n, presented minimal variations, which indicate that the principal decomposition mechanism was conserved virtually constant across the temperature range evaluated. The increase in β, meanwhile, translates into a progressive reduction in ln[−ln(1 − α)] that manifests the influence of thermal residence time on the advance of the reaction. Taken together, these tendencies support the applicability of Avrami’s model to describe the global kinetics of the thermal degradation of biomass, while the numerical values in Table 3 below permit a more detailed, quantitative interpretation of the kinetic behavior of the system that includes the temperatures analyzed, the linear adjustment slopes, the values for the reaction order, n, and the correlation coefficients obtained.

Table 3.

Fractional order and fittings of the Avrami model for the thermal degradation of P. americana.

The results of Avrami’s model show a high adjustment level indicative of its suitability for describing the global kinetics of the thermal degradation of lignocellulosic biomass (Table 3). The temperature range analyzed (~252–362 °C) covers the main stages of the decomposition of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin, and spans both the initial and advanced stages of the process. The parameter n shows a progressive increase with temperature, as the low values (0.0855–0.2267) in the lower interval reflect a gradual degradation of hemicellulose, while the maximum values (0.3455) in the upper interval indicate more complex kinetics associated with the simultaneous decomposition of residual cellulose, lignin, and intermediate products. This behavior, evidenced in the variability of n, is explained by the differentiated distribution of the activation energy and the heterogeneous nature of reactivity among the components of the biomass, as Cai et al. reported [51], supported by the usefulness of Avrami’s model as an empirical tool to represent the global kinetics of a multistage process. These results suggest that degradation does not occur through one simple, elemental mechanism but, rather, is modulated by phenomena of diffusion, mass and heat transfer, and the superposition of thermochemical processes, including fragmentation of the structure, the release of intermediate volatiles, and the formation of solid residues [52]. Consequently, the kinetic analysis yields apparent parameters that describe this effective global behavior. The specific composition of the biomass, with high cellulose (46.8%) and hemicellulose (20.6%) content, moderate lignin content (14.5%), and high extractable fractions (~17%) (see Table 1), contributes to both the diversity of reactive routes and thermal heterogeneity, while also differentiating its kinetic behavior from that of other lignocellulosic biomasses, such as the wood of Ceiba aesculifolia, which shows greater uniformity due to its high cellulose content and lower proportions of hemicellulose, lignin, and extractables [12].

The consistency of the adjustments justifies using the average value of the fractional reaction order (n = 0.2824) when applying the Coats–Redfern method to estimate the kinetic parameters Ea and A (Table 4). Figure 3e presents the results of applying this model. The linear adjustments obtained reveal a high correlation that confirms its pertinence for describing the thermal degradation of biomass.

Table 4.

Kinetic parameters of P. americana branches determined using iso-conversional methods (Friedman, FWO, and KAS), the Kissinger method, and the Coats–Redfern integral method applied in this study at different heating rates (β = 10–30 °C/min).

That figure also shows that as the degree of conversion increases (α = 0.15–0.70), the curves shift progressively toward lower 1/T values. This indicates that the more advanced stages of the process occur at higher temperatures. Moreover, the grouping of the curves in the left region of the graph reflects a lower variation in the activation energy in these phases, while the slight differences in the slopes suggest that this parameter does not remain constant throughout conversion. This behavior is consistent with both the multicomponent nature of the biomass and the scaled degradation of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin.

The quantitative values derived from the models applied (Coats–Redfern, Friedman, FWO, KAS, and Kissinger) are shown in Table 4. Results include the values of Ea, the factor A, and the correlation coefficient (R2) for the conversion interval α = 0.15–0.70. For Kissinger’s method, we report a single derived value of Tp for each heating rate.

The Friedman, FWO, and KAS iso-conversional methods all showed a progressive increase in Ea as the degree of conversion increased (α = 0.15–0.70) with ranges of 174.6–302.3, 167.4–225.9, and 166.7–227.1 kJ/mol, respectively. Kissinger’s method provided a single value of 171.3 kJ/mol that corresponded to Tp. The factors A relate proportionally to Ea, as they reached values between 1012 and 1016 s−1 with a maximum of 1.16 × 1022 s−1, determined by Friedman’s model for α = 0.70. Every method displayed a robust adjustment with correlation coefficients (R2) ˃ 0.97.

Regarding the pre-exponential factor, Friedman showed the greatest dispersion, with values between 4.21 × 1012 and 1.16 × 1022 s−1, while FWO and KAS presented tighter and more consistent intervals. Coats–Redfern achieved the best average fit (R2 ≈ 0.9878) and a mean A value lower than the iso-conversional methods, even though its variability was not the lowest. Kissinger, for its part, provided a single pair (Ea, A) associated with the maximum of the DTG signal, with A lower than the average of the differential and integral methods. The wide dispersion observed in A, particularly in Friedman, is consistent with the complexity of biomass pyrolysis and with what has been reported in the literature, where free-model methods tend to generate more dispersed values due to the superposition of multiple reactions [11].

The Coats–Redfern analysis generated Ea values of 163.8–221.0 kJ/mol and A values between the orders 1012 and 1016 s−1, with R2 of 0.9607–0.9978 (average 0.9878). The ascending tendency of Ea and A in the final stages reflects the transition of the more reactive components, like hemicellulose and cellulose, toward more stable fractions, such as lignin and condensed aromatic structures. This variation is consistent with the sequential decomposition of lignocellulosic pseudo-components: hemicellulose degrades at lower temperatures, cellulose in intermediate stages, and lignin at higher temperatures, due to differences in their molecular structure, crystallinity, and type of bonds, as has been documented in studies of pure components [47]. The progressive increase in Ea with α observed with the iso-conversional and Coats–Redfern methods confirms the multistage nature of the pyrolysis of biomass, characterized by the sequential degradation of more reactive fractions toward more recalcitrant components [19,53].

The proportional correlation between Ea and A evidences an effect of kinetic compensation consistent with transition state theory [20] and suggests related reaction mechanisms during the process. This behavior coincides with observations reported in experimental studies and reviews on biomass pyrolysis, where the linear relationship between A and Ea has been attributed to the kinetic compensation effect and the consistency of the predominant mechanisms in each reaction stage [11,44].

The values for the factor A are within the ranges reported for other lignocellulosic biomasses (with orders up to 1023 s−1) [11]. Their increase toward higher degrees of conversion reflects greater energy demand and molecular dynamics in the final stages of degradation. The greater variability observed in the results of Friedman’s method are interpreted as a manifestation of its sensitivity, which allowed us to identify in greater detail the stages of conversion that present significant kinetic changes, consistent with the multicomponent nature of the material [19]. In contrast, the FWO, KAS, and Coats–Redfern methods provided more uniform estimates that facilitate global, consolidated comparisons of the kinetic parameters. The single Kissinger value near the initial values of α = 0.15–0.30 estimated with Coats–Redfern) confirms that this method reflects mainly Ea at point Tp and is coherent with the other approaches for purposes of global comparison.

The upward tendency of energy, Ea, seen observed herein relates to the scaled degradation of the lignocellulosic components of the prunings from avocado trees, which contain high percentages of cellulose (46.8%) and hemicellulose (20.6%), but a moderate contribution of lignin (14.4%) (Table 1). The kinetic parameters determined with the Friedman, FWO, KAS, Coats–Redfern, and Kissinger methods show a coherent evolution of Ea and the factor A that provide evidence of similar mechanisms during the process and reflect the transition from more reactive fractions (amorphous hemicellulose and cellulose) toward more recalcitrant components (lignin and condensed aromatic structures) [54]. The high volatile material content (83.8%) and low ash level (1.2%) reinforce the idea that the initial phase is dominated by the rapid release of organic compounds, followed by more complex stages where fragmentation and recombination reactions predominate to produce carbonous residues. Overall, results show that the degradation dynamics of the branches is strongly conditioned by their chemical composition, and provide specific, quantitative information that is useful for analyzing and modeling pyrolytic processes of biomass in its natural state.

In addition to the multistage thermal behavior observed in the TGA and kinetic analyses, the physicochemical properties of the prunings of avocado trees support their potential for thermochemical conversion. The HHV (19.6 MJ/kg) lies in the range of woody biomasses of interest for energy studies and is particularly important in relation to the quality of the products of pyrolysis since high values favor obtaining liquid and gas fractions with good energy content and generating biochar that could be exploited as a solid fuel or an added-value input. However, the kinetic parameters determined (Ea up to ~302 kJ/mol; A up to 1022 s−1) reveal a significant energy barrier that limits the thermal reactivity of this material. As a result, the heating potential identified does not translate automatically into an efficient conversion under conventional pyrolysis conditions. It is, therefore, essential to integrate kinetic criteria with the energy criteria when designing and optimizing processes in order to define strategies that will make it possible to overcome the material’s thermal resistance and more effectively exploit its capacity to generate products with energy value.

The increasing tendency of Ea observed can be explained by the lignocellulosic composition of the material, where the scaled decomposition of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin generated a multistage behavior. In this sense, the functional characterization by FTIR supports the kinetic evolution since the signals associated with hemicellulose carbonyls (1740 cm−1), polysaccharides (1245–1030 cm−1), and aromatic lignin structures (160–1460 cm−1) evidence an overlapping decomposition of these components. During the active phase (280–360 °C), when the largest increases of Ea were recorded, the spectrum confirms the transition from more reactive fractions toward more stable structures, a finding consistent with the growing participation of lignin. In advanced stages (>400 °C), the appearance of condensed aromatic signals (820 cm−1) concurs with the formation of fixed carbon observed in the TGA and strengthens the relation between the thermal stability and chemical composition of the residue.

In previous studies under combustion conditions, the woody fraction of prunings of avocado trees presented Ea between 143.9 and 211.0 kJ/mol [55], values close to the ones obtained herein for pyrolysis (163.8–227.0 kJ/mol). This similarity indicates that the global thermal resistance of the material is comparable despite the distinct atmospheres. Pyrolysis, however, has the advantage of orienting the conversion process toward condensable, carbonous fractions of great interest for the field of energy. This underscores the importance of this focus for valorizing lignocellulosic residues.

In contrast, the studies of avocado seeds under pyrolytic conditions by Malagón-Romero et al. [6] reported Ea values by FWO and KAS of 24–226 kJ/mol, while the woody biomass of prunings evaluated in our work show higher, more consistent values (166–227 kJ/mol, FWO and KAS) that reflect greater thermal stability associated with their high lignocellulosic fraction. As was to be expected given the more homogeneous nature of the woody fraction compared to the heterogeneous composition of seeds, these results from a broad range of heating rates (10–30 °C/min) permit a more robust estimate of the kinetic parameters and stress the predictability of the thermal behavior of the branches for pyrolysis processes.

The kinetic results for the pyrolysis of branches of avocado wood present values above those reported for the woody biomasses of Mangifera indica (143.0–176.5 kJ/mol, Sharma & Mohanty [56]) and Ceiba aesculifolia (118–156 kJ/mol, Alvarado-Flores et al. [12]), suggesting that the thermal decomposition of the biomass of avocado prunings has higher energy requirements. When comparing kinetic parameters with chemical composition, it is revealed that the trend in activation energies is not strictly governed by lignin content. Although Mangifera indica has the highest content of this polymer (23.8%), it does not exhibit the highest Ea values, suggesting the decisive influence of other components. The branches of P. americana, which have the highest extractive content (~17%), are distinguished by their kinetic complexity, evidenced by the very wide range of their pre-exponential factors (1012–1022 s−1). This behavior is consistent with more diverse and complex decomposition pathways facilitated by these non-structural compounds. In contrast, the tighter ranges of Mangifera indica (1010–1013 s−1) and Ceiba aesculifolia (104–1011 s−1) reflect more uniform decomposition mechanisms, typical of the main lignocellulosic matrices. The lower Ea and A values in Ceiba aesculifolia are also consistent with its cellulose-dominated composition (66.2%) and low lignin content (10.8%). Taken together, these findings support the notion that the higher energy demand for the pyrolysis of P. americana is not dictated by a single biopolymer, but probably results from the synergistic interaction between its structural (intermediate lignin) and non-structural (high extractives) components, a perspective that constitutes a key contribution of this study.

Studies of the pyrolysis of agricultural residues and hardwoods report Ea values that fluctuate from approximately 74 to over 300 kJ/mol. In contrast, under combustion conditions some woody and fruit materials show even higher values (up to 370–420 kJ/mol). This reflects the influence of chemical composition, structure, and reaction atmosphere on thermal kinetics. The combination of these relatively high Ea values with high A factors tells us that the biomass of avocado prunings presents significant kinetic barriers, and suggests the importance of carefully adjusting operating parameters like temperature and residence time to achieve effective conversion. These results emphasize that the biomass of avocado prunings generates a complex dynamic reaction, one that requires stricter thermal conditions or prolonged residence times to achieve efficient conversion. However, they present more stable thermal behavior and more predictable kinetics, two especially important properties for biochar production.

The kinetic analysis of the branches of P. americana showed that thermal resistance increased with the degree of conversion. The Friedman, FWO, and KAS iso-conversional methods, together with the Kissinger and Coast–Redfern approaches, provided estimates of highly reliable kinetic parameters (R2 > 0.95) that are consistent with the literature on lignocellulosic biomasses. This was especially true for the FWO, KAS, and Coats–Redfern methods. Activation energy (Ea) was determined between 163.8 and 302.3 kJ/mol, while the frequency factors (A) ranged from 1012 to 1022 s−1, indicative of Arrhenius-type kinetic compensation. The non-linear, multiphase kinetics described by Avrami’s model (average order n = 0.2824; R2 = 0.9711) reflected the simultaneity of the degradation mechanisms of cellulose, lignin, and intermediate products, whose n value was later used to calculate parameters using Coats–Redfern (R2 = 0.9878). The coherence among the various models validates the solidity of our results, confirms the multistage character of the process, and places avocado biomass in a medium-to-high range of thermal stability.

3.2.3. Estimates of Thermodynamic Parameters

Table 5 displays the thermodynamic parameters of the thermal decomposition of P. americana (ΔH, ΔG, ΔS) obtained through the kinetic models applied at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. These values, calculated as a function of α, and their interpretation, are based on transition state theory [20], which establishes the formation of a high-energy, activated complex conditioned by Ea that makes it possible to representatively characterize the thermal and energy behavior of this biomass during pyrolysis.

Table 5.

Thermodynamics parameters of Persea americana Mill at different heating rates.

Overall enthalpy values (ΔH) were high, indicating that the biomass requires considerable energy input to reach the activated state. As mentioned above, the combination of high ΔH values with high A factors reveals that this residue presents significant kinetic barriers. Hence, the design of pyrolysis processes to valorize energy requires careful control of the operating conditions, especially reaction temperature and residence time, to foster efficient, stable conversion. The behavior observed supports this residue’s potential for applications that produce biocarbon, due to its relative resistance to thermal degradation and the possibility of modulating reactivity through adequate operating conditions.

The ΔH values obtained for P. americana (160.6–297.0 kJ/mol) place this material in the upper reaches of the range reported for other lignocellulosic biomasses, such as Mangifera indica (~150–180 kJ/mol, Sharma & Mohanty [56]) and Ceiba aesculifolia (≈65–152 kJ/mol, Alvarado-Flores et al. [12]). The ΔH of prunings of avocado trees is relatively low in the initial stages of pyrolysis, but increases as conversion advances, suggesting that later phases of the process require greater energy inputs.

The positive, stable ΔG values (176.8–180.0 kJ/mol) confirm that pyrolysis of P. americana does not occur spontaneously, but requires a constant energy supply, as Van de Velden et al. [57] reported previously, plus the influence of resistant lignocellulosic components like lignin and carbonaceous materials [20,58]. These conditions foment the formation of stable biocarbon that has potential applications for carbon sequestration [58,59]. These ΔG values also exceed those recorded for sawdust from Mangifera indica (~151 kJ/mol, Sharma & Mohanty, [56]) and are slightly higher than those of Ceiba aesculifolia wood (~175 kJ/mol; Alvarado-Flores et al. [12]). These findings suggest greater thermodynamic stability attributable to structural differences. Such comparisons must, however, be interpreted in light of the specific experimental conditions employed (heating rate, reaction atmosphere), for they can significantly impact reported values.

Entropy (ΔS) showed marked variations, with values ranging from −33.8 to 194.0 J/mol·K. During the initial stages of conversion (α = 0.15–0.40), we observed negative ΔS values, typical of a more ordered state of the system and lower reactivity. As pyrolysis advanced, ΔS acquired positive values, reaching a maximum of ~194 J/mol·K at α ≈ 0.70, indicative of an increased structural disorder and a higher reaction velocity associated with the fragmentation of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin [4].

For biomasses like Mangifera indica, negative ΔS values were determined for the initial stages, but turned positive in the intermediate intervals (−34.3 to +34.0 J/mol·K) [56], though a study of Ceiba aesculifolia generated only negative ΔS values (−34.8 to −185.6 J/mol·K) [12]. This was also the case of olive and palm leaves and wheat straw, which generated negative ΔS values (−183 to −192 J/mol·K) [19].

In conjunction with the relatively high ΔH and ΔG values obtained for the branches of P. americana, which are at the upper end of the ranges reported for Mangifera indica and Ceiba aesculifolia, the evolution of ΔS toward positive values in intermediate and advanced stages reinforces the idea of a thermal conversion process that requires greater energy inputs and exhibits a progressive increase in structural disorder. This response could be associated with the combination of an intermediate lignin content and a high proportion of extractives, factors that may favor more diverse decomposition processes and thermodynamic behavior different from that observed in biomasses of more conventional composition. Considering the evolution of ΔS together with ΔH and ΔG is essential for understanding the thermal conversion of this biomass and for improving the kinetic and thermodynamic modeling approaches applied to its pyrolysis.

The pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass presents marked variation in thermodynamic and kinetic parameters that depends on the chemical composition, heating rate, degree of conversion, and calculation methodology applied [4]. This heterogeneity underscores the need to evaluate each type of biomass individually in relation to its thermochemical nature in order to optimize processes designed to obtain products with energy or chemical value [4,9,60].

The thermodynamic parameters obtained support the tendencies observed in the kinetic analysis and confirm that pyrolysis of avocado prunings is a non-spontaneous, endothermic process. Activation enthalpy (ΔH) ranged from 160.6 to 297.0 kJ/mol and increased with the degree of conversion (α). This indicates greater energy demand in advanced stages of the process. The fact that Gibbs free energy (ΔG) remained around 170 kJ/mol identifies the process as non-spontaneous. Entropy (ΔS), in turn, presented negative values for α = 0.15–0.40 but positive ones from α = 0.45, with a total range of −158 to 194 J/mol·K. These results reveal a transition toward more disordered states as degradation advanced.

The thermodynamic parameters determined for P. americana branches show relatively high values of ΔH and ΔG compared to similar biomass, reflecting the thermal resistance of this waste and its potential to promote conversion to biochar. These values indicate that pyrolysis requires a controlled energy input, allowing temperature profiles and residence time to be adjusted to optimize the formation of a stable carbonaceous solid fraction, minimizing the volatilization of less resistant components. The positive progression of ΔS with the degree of conversion suggests a structural transition towards more disordered states, associated with the gradual release of volatiles and the stabilization of aromatic structures in the biochar. Taken together, these findings reinforce the importance of kinetic and thermodynamic parameters in designing efficient pyrolysis strategies and maximizing recalcitrance and carbon retention in biochar [57,59].

Since this study focuses on the valorization of pruning residues, the kinetic parameters obtained reflect an apparent behavior inherent to realistic processing conditions, where heat and mass transfer effects are significant. This effective kinetics provides a highly applicable foundation for reactor-scale modeling and process optimization. Consequently, the results deliver a robust and practical characterization that directly supports the experimental scaling of pyrolysis, the evaluation of value-added products, and the development of predictive tools for designing more efficient thermochemical valorization pathways for lignocellulosic residues.

4. Conclusions

The thermal decomposition of Persea americana pruning residues showed that the maximum degradation rate is concentrated within a lower (315–360 °C) and narrower interval compared to the typical ranges reported for isolated components (cellulose ~345 °C, lignin ~400 °C). This evidence indicates a synergistic and accelerated decomposition of the structural components. This overlap suggests that the pyrolysis of this biomass is dominated by interactive reactions that concentrate the greatest mass loss within a reduced thermal window, favoring an intense and early release of volatiles.

Kinetic analysis demonstrated that the combined Avrami–Coats–Redfern approach is the most suitable for describing this process. The Avrami model yielded a low reaction order (n ≈ 0.28), and applying this value in the Coats–Redfern model provided the best fit (R2 ≈ 0.9878) and the narrowest range of pre-exponential factors (A = 1012–1016 s−1), indicating greater parametric consistency. The activation energies (Ea between 185 and 210 kJ/mol) lie at the upper end of the range reported for other lignocellulosic biomasses, suggesting a higher inherent thermal stability for this biomass.

The estimated thermodynamic parameters (ΔH = 166–206 kJ/mol; ΔG ≈ 179 kJ/mol), positioned at the upper range of those reported for other woody biomasses, indicate a thermal conversion process that requires a relatively high energy input. This trend suggests that the structure of this biomass exhibits moderately high thermal stability against degradation. The observed entropy increase (ΔS up to 194 J/mol·K), while consistent with that documented for comparable woods, reflects the transition toward more disordered activated states without revealing atypical behavior.

This kinetic–thermodynamic profile explains why slow to intermediate pyrolysis regimes are optimal for this biomass: they allow overcoming its high energy barrier and controlling the intense release of volatiles, thereby maximizing biochar yield. The study establishes a specific and comparative reference framework for P. americana, validating the effectiveness of the Avrami–Coats–Redfern model and providing distinctive parameters for process design.

A limitation of the study is the absence of identification and quantification of the extractive fractions of P. americana, which prevented the evaluation of their potential contribution to certain FT-IR bands (such as the one observed at ≈2860 cm−1) and a more precise determination of their influence on the observed thermochemical behavior. Given that the composition of extractives can modify both certain spectroscopic responses and aspects of thermal decomposition, it is considered pertinent for future work to incorporate their characterization to elucidate their role in the thermal evolution of this biomass.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.S.-G., J.J.A.-F., J.G.R.-Q., M.L.Á.-R. and J.V.A.-V.; methodology, J.A.S.-G., J.J.A.-F., J.G.R.-Q., M.L.Á.-R. and J.V.A.-V.; software, J.J.A.-F.; validation, J.A.S.-G., J.J.A.-F., J.G.R.-Q., R.H.-B., J.V.A.-V., M.L.Á.-R., L.B.L.-S. and E.G.-M.; formal analysis, J.A.S.-G., J.J.A.-F., J.G.R.-Q., R.H.-B., J.V.A.-V., M.L.Á.-R., L.B.L.-S. and E.G.-M.; investigation, J.A.S.-G., J.J.A.-F., J.V.A.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.S.-G., J.J.A.-F., J.G.R.-Q., R.H.-B., J.V.A.-V., L.B.L.-S., M.L.Á.-R. and E.G.-M.; writing—review and editing, J.A.S.-G. and J.J.A.-F.; visualization, R.H.-B., J.V.A.-V., M.L.Á.-R., L.B.L.-S.; and E.G.-M.; supervision, J.J.A.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The author José Alberto Soria González thanks Secretaría de Ciencias, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI) for the financial support provided during his studies in the Doctorado en Ciencias y Tecnología de la Madera program at the UMSNH. The authors thank the coordination of scientific research (CIC) program for supporting this research through the Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carrillo-Parra, A.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Ríos-Saucedo, J.C.; Ruiz-García, V.M.; Ngangyo-Heya, M.; Nava-Berumen, C.A.; Núñez-Retana, V.D. Quality of Pellet Made from Agricultural and Forestry Waste in Mexico. Bioenergy Res. 2022, 15, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauro, R.; Manrique, S.; Franch, I.; Juan, P.; Medellin, F.C. Spatial Expansion of Avocado in Mexico: Could the Energy Use of Pruning Residues Offset Orchard GHG Emissions? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 27325–27350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera, (SIAP) Avance de Siembras y Cosechas: Resumen Nacional Por Estado, Perennes, Agosto 2025. Available online: https://nube.agricultura.gob.mx/avance_agricola/ (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Zadeh, Z.E.; Abdulkhani, A.; Aboelazayem, O.; Saha, B. Recent Insights into Lignocellulosic Biomass. Processes 2020, 8, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Luo, L.; Yellezuome, D.; Rahman, M.M.; Zou, J.; Hu, H.; Cai, J. Insight into Kinetic and Thermodynamic Analysis Methods for Lignocellulosic Biomass Pyrolysis. Renew. Energy 2023, 202, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malagón-Romero, D.H.; León-Caballero, N.D.; Velasco-Peña, M.A.; Arrubla-Vélez, J.P.; Quintero-Naucil, M.; Aristizábal-Marulanda, V. Pyrolysis of Hass Avocado (Persea Americana) Seeds: Kinetic and Economic Analysis of Bio-Oil, Gas, and Biochar Production. Bioenergy Res. 2025, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, S.; Rosha, P.; Kumar, S. Recent Modeling Approaches to Biomass Pyrolysis: A Review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 7406–7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potnuri, R.; Suriapparao, D.V.; Rao, C.S.; Kumar, T.H. Understanding the Role of Modeling and Simulation in Pyrolysis of Biomass and Waste Plastics: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 20, 101221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelela, D.; Saleh, H.; Attia, A.M.; Elhenawy, Y.; Majozi, T.; Bassyouni, M. Recent Advances in Biomass Pyrolysis Processes for Bioenergy Production: Optimization of Operating Conditions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Pareek, V.; Zhang, D. Biomass Pyrolysis—A Review of Modelling, Process Parameters and Catalytic Studies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 1081–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado Flores, J.J.; Alcaraz Vera, J.V.; Ávalos Rodríguez, M.L.; López Sosa, L.B.; Rutiaga Quiñones, J.G.; Pintor Ibarra, L.F.; Márquez Montesino, F.; Aguado Zarraga, R. Analysis of Pyrolysis Kinetic Parameters Based on Various Mathematical Models for More than Twenty Different Biomasses: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 6524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado Flores, J.J.; Pintor Ibarra, L.F.; Mendez Zetina, F.D.; Rutiaga Quiñones, J.G.; Alcaraz Vera, J.V.; Ávalos Rodríguez, M.L. Pyrolysis and Physicochemical, Thermokinetic and Thermodynamic Analyses of Ceiba aesculifolia (Kunth) Britt and Baker Waste to Evaluate Its Bioenergy Potential. Molecules 2024, 29, 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S. Isoconversional Kinetics of Thermally Stimulated Processes; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; ISBN 9783319141756. [Google Scholar]

- Bongomin, O.; Nzila, C.; Igadwa Mwasiagi, J.; Maube, O. Comprehensive Thermal Properties, Kinetic, and Thermodynamic Analyses of Biomass Wastes Pyrolysis via TGA and Coats-Redfern Methodologies. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 24, 100723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrami, M. Kinetics of Phase Change. I General Theory. J. Chem. Phys. 1939, 7, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supee, A.H.; Zaini, M.A.A. Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Thermal Decomposition Behavior of Palm Oil Empty Fruit Bunch, Coconut Shell, Bamboo, and Cardboard Pyrolysis: An Integrated Approach Using Coats–Redfern Method. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.G.; Kim, M.J.; Eom, C.D. Kinetic Study of Torrefied Woody Biomass via TGA Using a Single Heating Rate and the Model-Fitting Method. Bioresources 2022, 17, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Mohanty, K. Kinetic Analysis and Pyrolysis Behavior of Low-Value Waste Lignocellulosic Biomass for Its Bioenergy Potential Using Thermogravimetric Analyzer. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2021, 4, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, S.A.; Khass, T.M.; Mostafa, M.E. Thermal Degradation Behaviour and Chemical Kinetic Characteristics of Biomass Pyrolysis Using TG/DTG/DTA Techniques. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 17779–17803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Burnham, A.K.; Criado, J.M.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Popescu, C.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. ICTAC Kinetics Committee Recommendations for Performing Kinetic Computations on Thermal Analysis Data. Thermochim. Acta 2011, 520, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-González, J.A.; Tauro, R.; Alvarado-Flores, J.J.; Berrueta-Soriano, V.M.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G. Avocado Tree Pruning Pellets (Persea Americana Mill.) for Energy Purposes: Characterization and Quality Evaluation. Energies 2022, 15, 7514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, C.T.; Mong, G.R.; Ng, J.H.; Chong, W.W.F.; Ani, F.N.; Lam, S.S.; Ong, H.C. Pyrolysis Characteristics and Kinetic Studies of Horse Manure Using Thermogravimetric Analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 180, 1260–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H.L. Kinetics of Thermal Degradation of Char-Forming Plastics from Thermogravimetry. Application to a Phenolic Plastic. J. Polym. Sci. Part. C Polym. Symp. 1964, 6, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, H.E. Reaction Kinetics in Differential Thermal Analysis. Anal. Chem. 1957, 29, 1702–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, T. Kinetic Analysis of Derivative Curves in Thermal Analysis. J. Therm. Anal. 1970, 2, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akahira, T.; Sunose, T. Method of Determining Activation Deterioration Constant of Electrical Insulating Materials. Res. Rep. Chiba Inst. Technol. 1971, 16, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Coats, A.W.; Redfern, J.P. Kinetic Parameters from Thermogravimetric Data. Nature 1964, 201, 68–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musule, R.; Alarcón-Gutiérrez, E.; Houbron, E.P.; Bárcenas-Pazos, G.M.; del Rosario Pineda-López, M.; Domínguez, Z.; Sánchez-Velásquez, L.R. Chemical Composition of Lignocellulosic Biomass in the Wood of Abies Religiosa across an Altitudinal Gradient. J. Wood Sci. 2016, 62, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonultas, O.; Candan, Z. Chemical Characterization and Ftir Spectroscopy of Thermally Compressed Eucalyptus Wood Panels. Maderas Cienc. Y Tecnol. 2018, 20, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Salim, R.; Asik, J.; Sarjadi, M.S. Chemical Functional Groups of Extractives, Cellulose and Lignin Extracted from Native Leucaena Leucocephala Bark. Wood Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musule, R.; Núñez, J.; Bonales-Revuelta, J.; García-Bustamante, C.A.; Vázquez-Tinoco, J.C.; Masera-Cerutti, O.R.; Ruiz-García, V.M. Cradle to Grave Life Cycle Assessment of Mexican Forest Pellets for Residential Heating. Bioenergy Res. 2022, 15, 1733–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintor-Ibarra, L.F.; Alvarado-Flores, J.J.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Alcaraz-Vera, J.V.; Ávalos-Rodríguez, M.L.; Moreno-Anguiano, O. Chemical and Energetic Characterization of the Wood of Prosopis Laevigata: Chemical and Thermogravimetric Methods. Molecules 2024, 29, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Das, S.; Kharya, M. The Phytochemical and Pharmacological Profile of Persea Americana Mill. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- René, B.S. Estudio Químico de La Madera Del Tocón, Fuste y Ramas de Persea Americana, de La Región de Uruapan, Michoacán; Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo: Morelia, Mexico, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kan, T.; Strezov, V.; Evans, T.J. Lignocellulosic Biomass Pyrolysis: A Review of Product Properties and Effects of Pyrolysis Parameters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 1126–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.; Schöpper, C.; Vos, H.; Kharazipour, A.; Polle, A. FTIR-ATR Spectroscopic Analyses of Changes in Wood Properties during Particleand Fibreboard Production of Hardand Softwood Trees. Bioresources 2009, 4, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, B.; Marques, A.V.; Domingos, I.; Pereira, H. Chemical Changes of Heat Treated Pine and Eucalypt Wood Monitored by FTIR. Maderas. Cienc. Y Tecnol. 2013, 15, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efika, C.E.; Onwudili, J.A.; Williams, P.T. Influence of Heating Rates on the Products of High-Temperature Pyrolysis of Waste Wood Pellets and Biomass Model Compounds. Waste Manag. 2018, 76, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Q. Effects of Heating Rate on Slow Pyrolysis Behavior, Kinetic Parameters and Products Properties of Moso Bamboo. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 169, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, H.C.; Chen, W.H.; Singh, Y.; Gan, Y.Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Show, P.L. A State-of-the-Art Review on Thermochemical Conversion of Biomass for Biofuel Production: A TG-FTIR Approach. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 209, 112634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, D.; Xie, X.; Zhang, H.; Sun, H.; Hu, X.; Zhang, S. Fundamental Advances in Biomass Autothermal/Oxidative Pyrolysis: A Review. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 11888–11905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado Flores, J.J.; Rutiaga Quiñones, J.G. Estudio de Cinética En Procesos Termogravimétricos de Materiales Lignocelulósicos. Maderas. Cienc. Y Tecnol. 2018, 20, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anca-Couce, A.; Tsekos, C.; Retschitzegger, S.; Zimbardi, F.; Funke, A.; Banks, S.; Kraia, T.; Marques, P.; Scharler, R.; de Jong, W.; et al. Biomass Pyrolysis TGA Assessment with an International Round Robin. Fuel 2020, 276, 118002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, D.; Urueña, A.; Piñero, R.; Barrio, A.; Tamminen, T. Determination of Hemicellulose, Cellulose, and Lignin Content in Different Types of Biomasses by Thermogravimetric Analysis and Pseudocomponent Kinetic Model (TGA-PKM Method). Processes 2020, 8, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, A.V. Review of Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass and Product Upgrading. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 38, 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Ihara, I.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Ayyad, A.; Mehta, N.; Ng, K.H.; Abd El-Monaem, E.M.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Hosny, M.; et al. Materials, Fuels, Upgrading, Economy, and Life Cycle Assessment of the Pyrolysis of Algal and Lignocellulosic Biomass: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1419–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Cen, K.; Zhuang, X.; Gan, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. Insight into Biomass Pyrolysis Mechanism Based on Cellulose, Hemicellulose, and Lignin: Evolution of Volatiles and Kinetics, Elucidation of Reaction Pathways, and Characterization of Gas, Biochar and Bio-oil. Combust Flame 2022, 242, 112142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, S.A.; Mostafa, M.E. Kinetic Parameters Determination of Biomass Pyrolysis Fuels Using TGA and DTA Techniques. Waste Biomass Valorization 2015, 6, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahirul, M.I.; Rasul, M.G.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Ashwath, N. Biofuels Production through Biomass Pyrolysis- A Technological Review. Energies 2012, 5, 4952–5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayón, R.; García-Rojas, R.; Rojas, E.; Rodríguez-García, M.M. Assessment of Isoconversional Methods and Peak Functions for the Kinetic Analysis of Thermogravimetric Data and Its Application to Degradation Processes of Organic Phase Change Materials. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 13879–13899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; He, Y.; Yu, X.; Banks, S.W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Liu, R.; Bridgwater, A.V. Review of Physicochemical Properties and Analytical Characterization of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiola-Sadiq, T.; Zhang, L.; Dalai, A.K. Thermal and Kinetic Studies on Biomass Degradation via Thermogravimetric Analysis: A Combination of Model-Fitting and Model-Free Approach. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 22233–22247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikegwu, U.M.; Okoro, N.M.; Ozonoh, M.; Daramola, M.O. Thermogravimetric Properties and Degradation Kinetics of Biomass during Its Thermochemical Conversion Process. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 2163–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Huang, M.Y.; Chang, J.S.; Chen, C.Y.; Lee, W.J. An Energy Analysis of Torrefaction for Upgrading Microalga Residue as a Solid Fuel. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 185, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, S.; Reyes, S.; Lima, F.; Pilipenko, N.; Calvo, L.F. Combustion of Avocado Crop Residues: Effect of Crop Variety and Nature of Nutrients. Fuel 2021, 291, 119660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Mohanty, B. Thermal Degradation of Mango (Mangifera indica) Wood Sawdust in a Nitrogen Environment: Characterization, Kinetics, Reaction Mechanism, and Thermodynamic Analysis. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 13396–13408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Velden, M.; Baeyens, J.; Brems, A.; Janssens, B.; Dewil, R. Fundamentals, Kinetics and Endothermicity of the Biomass Pyrolysis Reaction. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Patra, B.R.; Podder, J.; Dalai, A.K. Synthesis of Biochar from Lignocellulosic Biomass for Diverse Industrial Applications and Energy Harvesting: Effects of Pyrolysis Conditions on the Physicochemical Properties of Biochar. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 870184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Cao, X.; Mašek, O.; Zimmerman, A. Heterogeneity of Biochar Properties as a Function of Feedstock Sources and Production Temperatures. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 256–257, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igliński, B.; Kujawski, W.; Kiełkowska, U. Pyrolysis of Waste Biomass: Technical and Process Achievements, and Future Development—A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).