Prediction Research of Wellbore Fractures and the Impact on Drilling Fluid Leakage

Abstract

1. Introduction

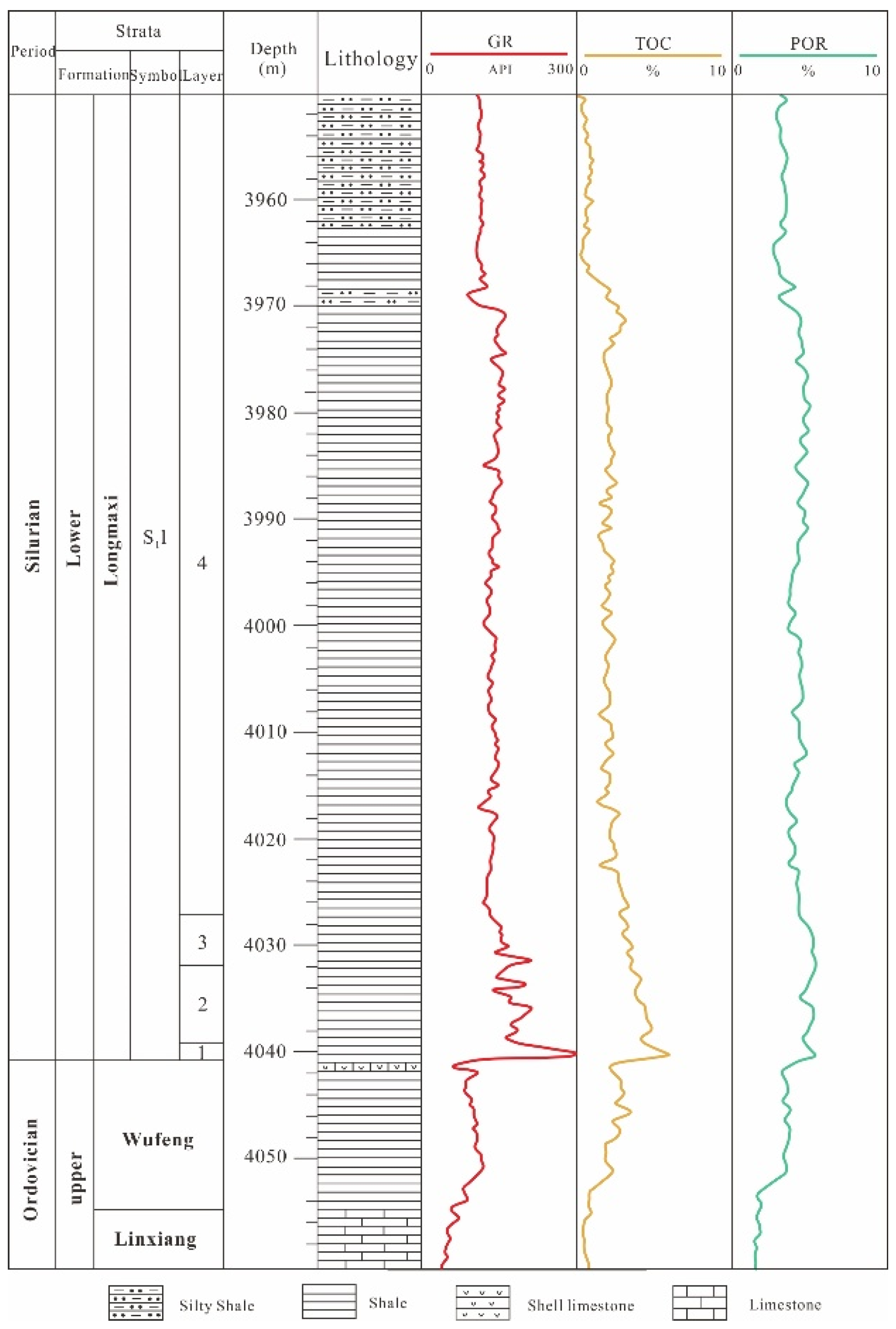

2. Geological Setting

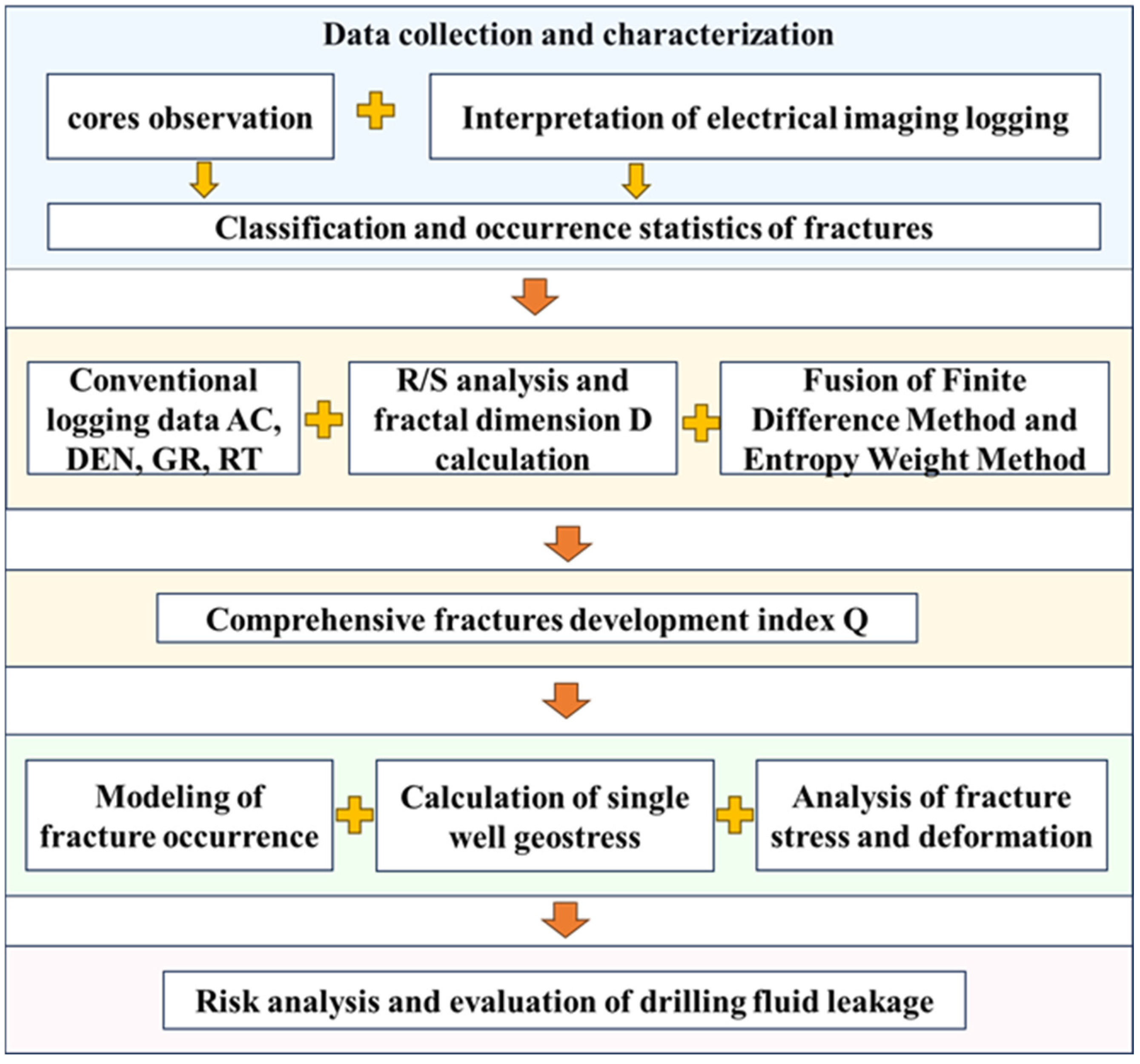

3. Fracture Characteristics and Numerical Modeling

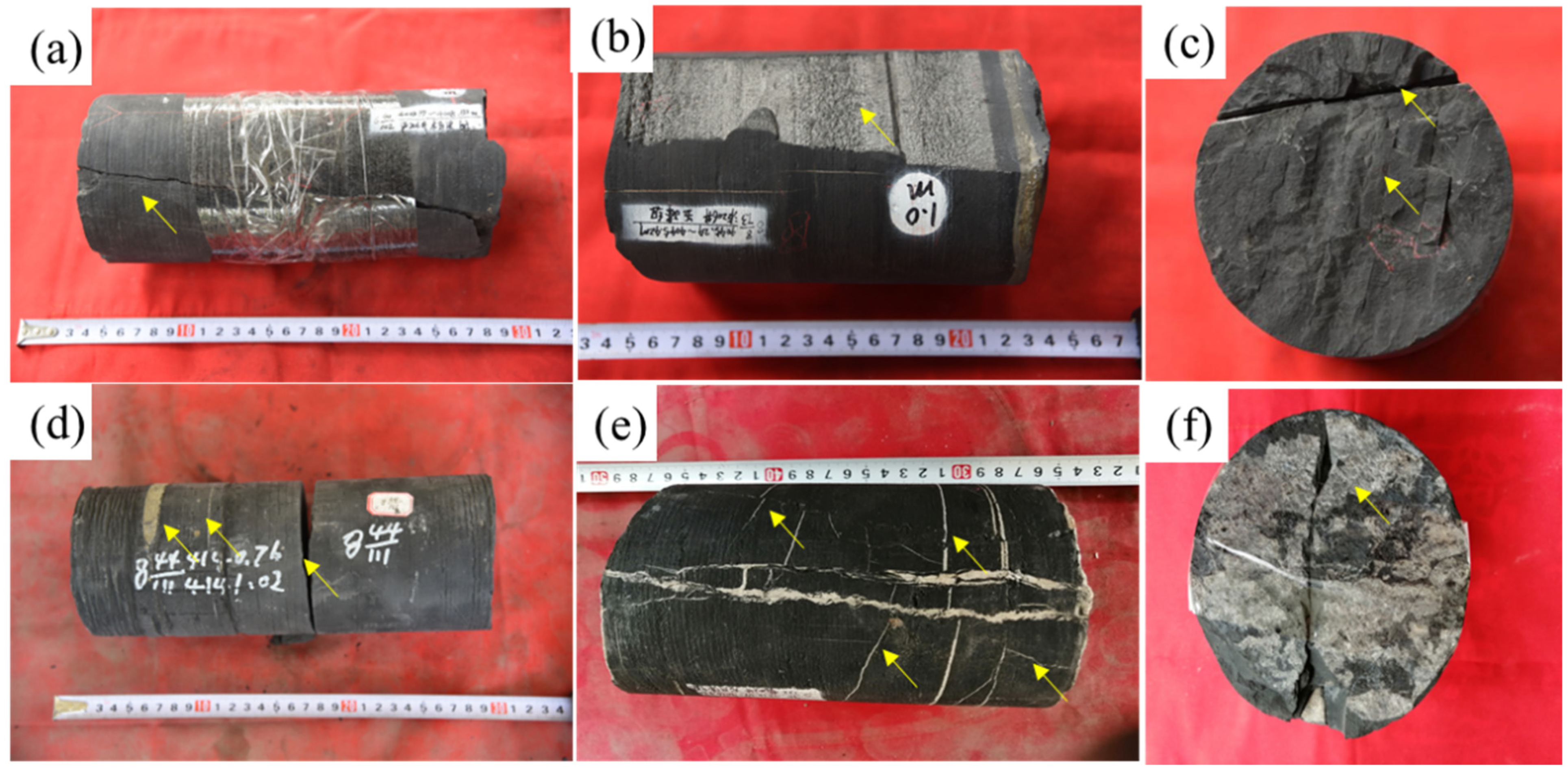

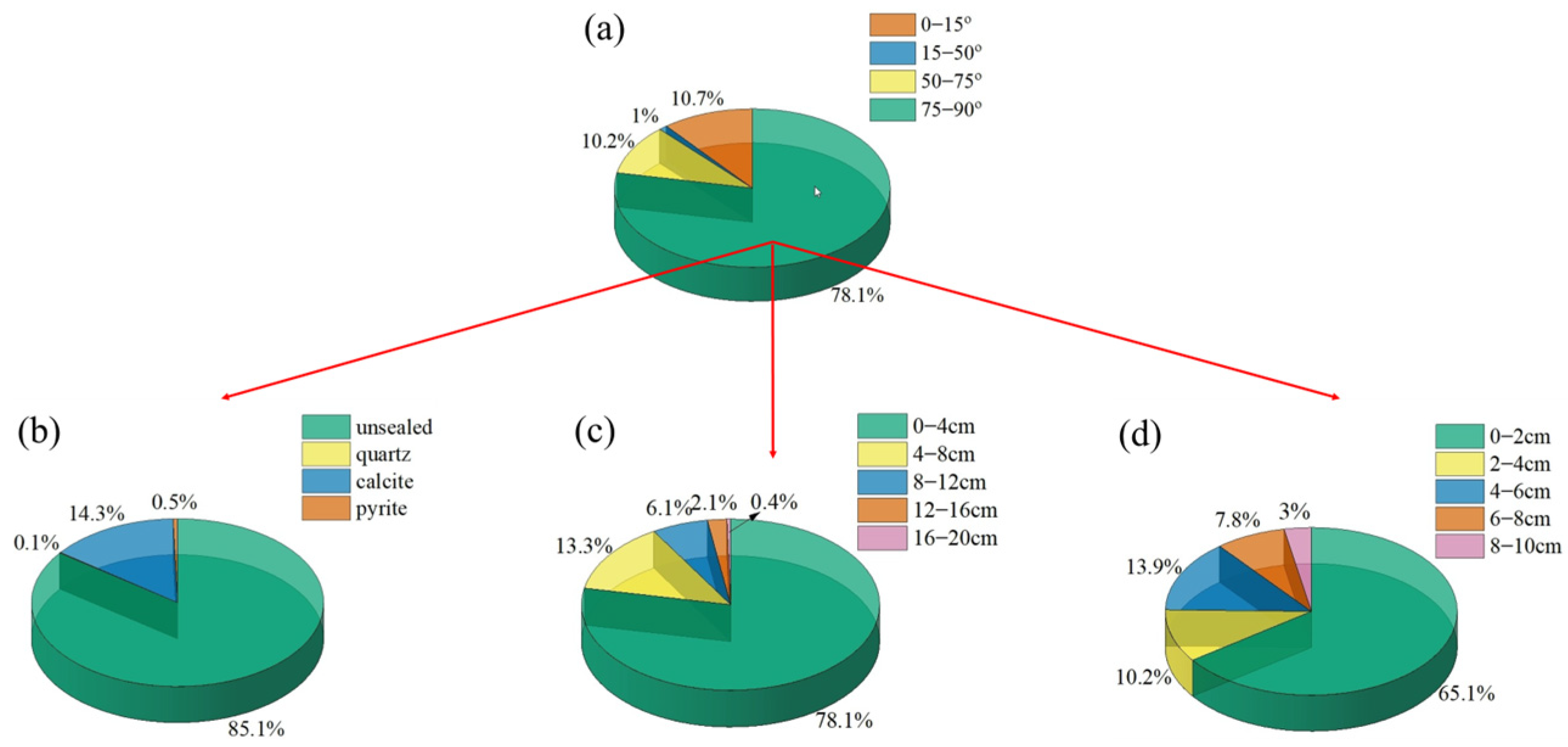

3.1. Fracture Characteristics in Cores

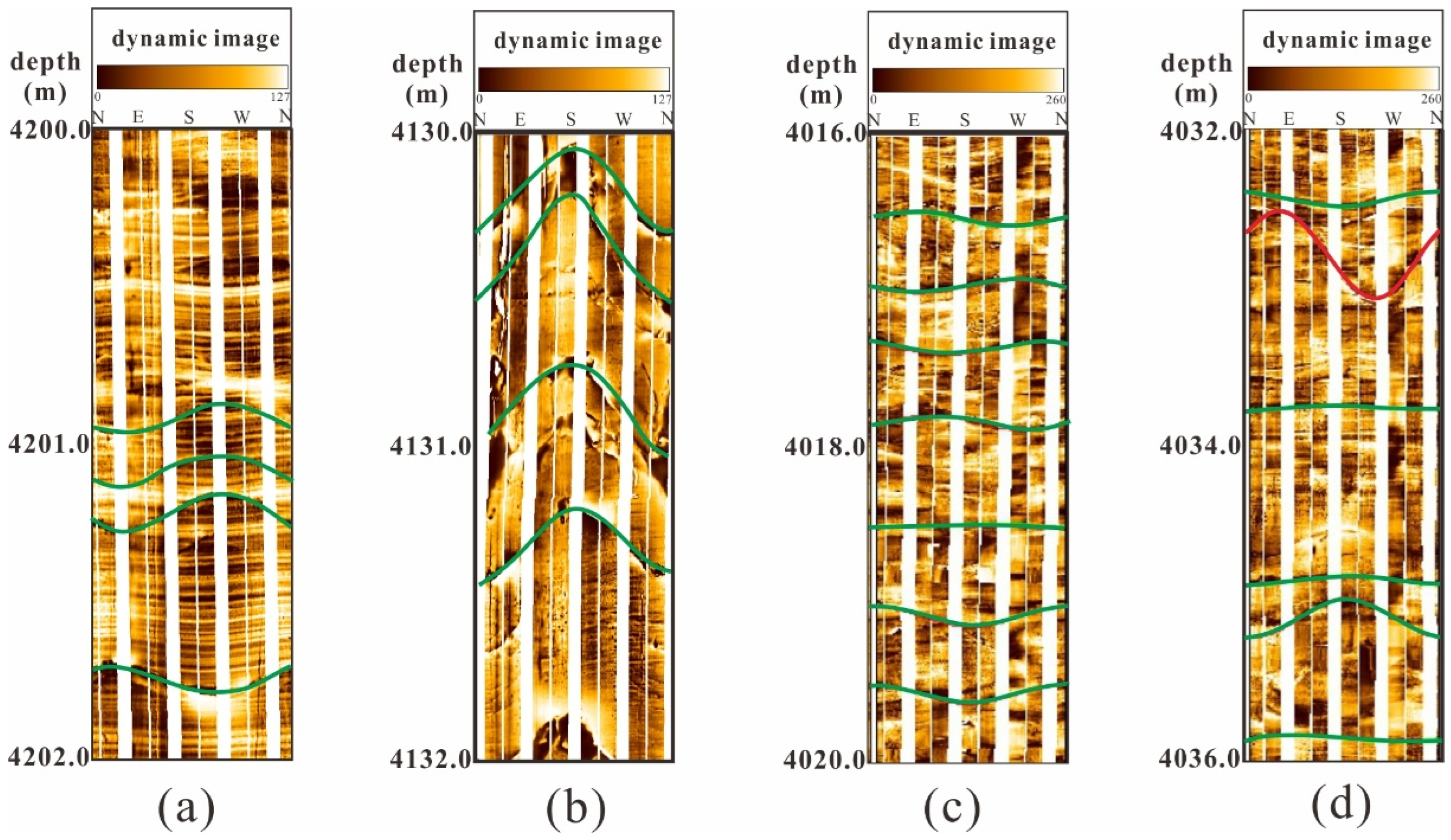

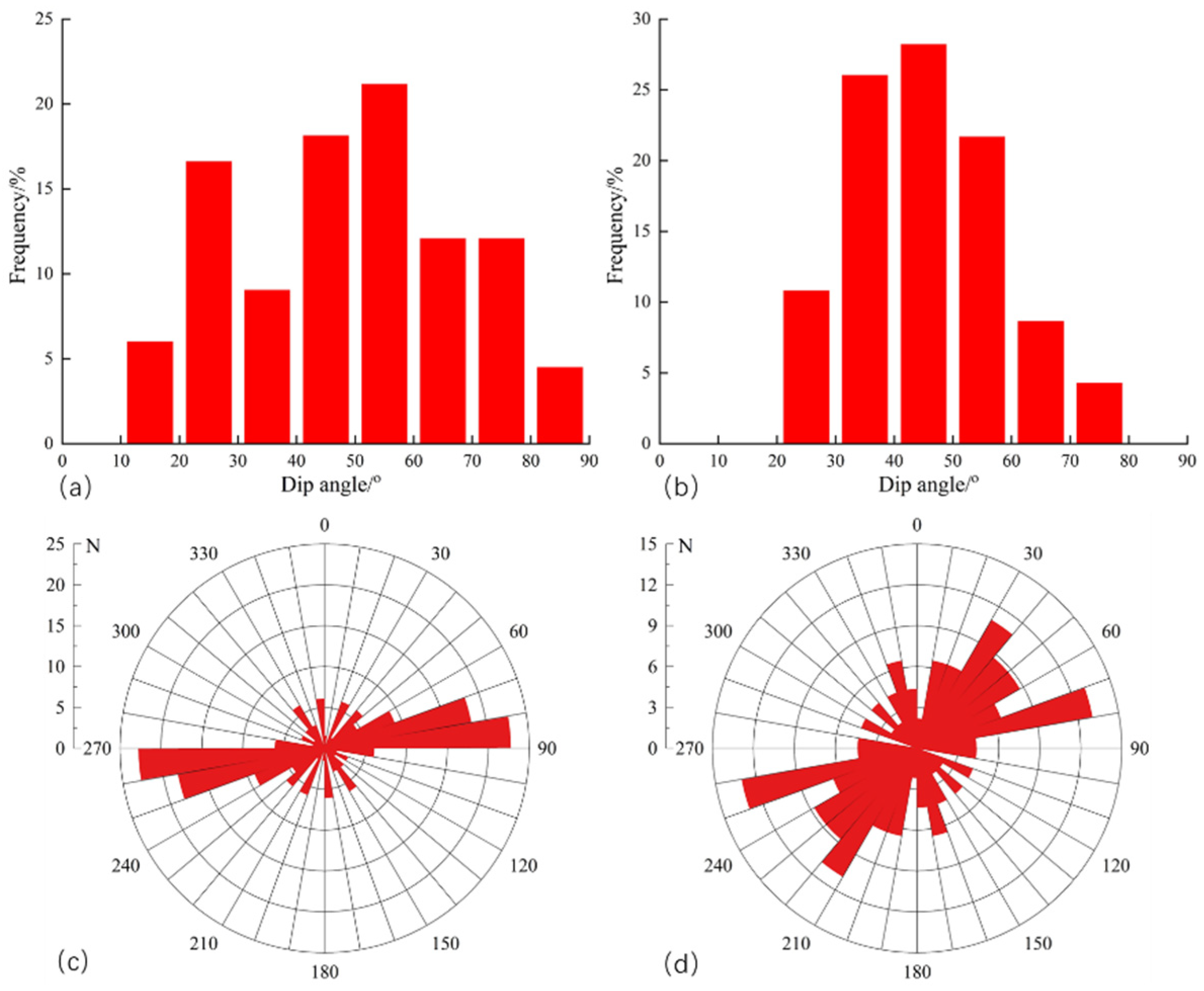

3.2. Fracture Characteristics of Image Logs

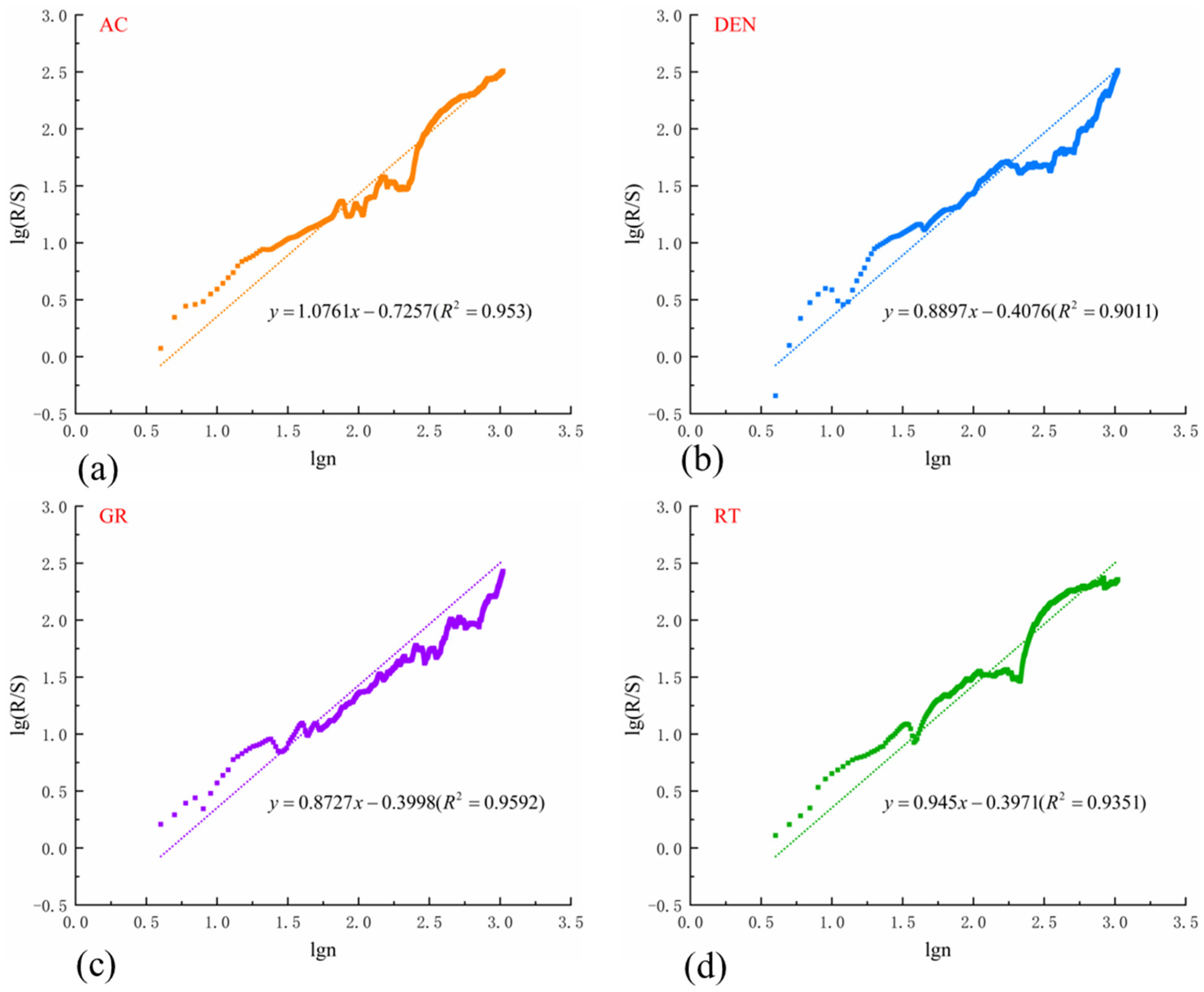

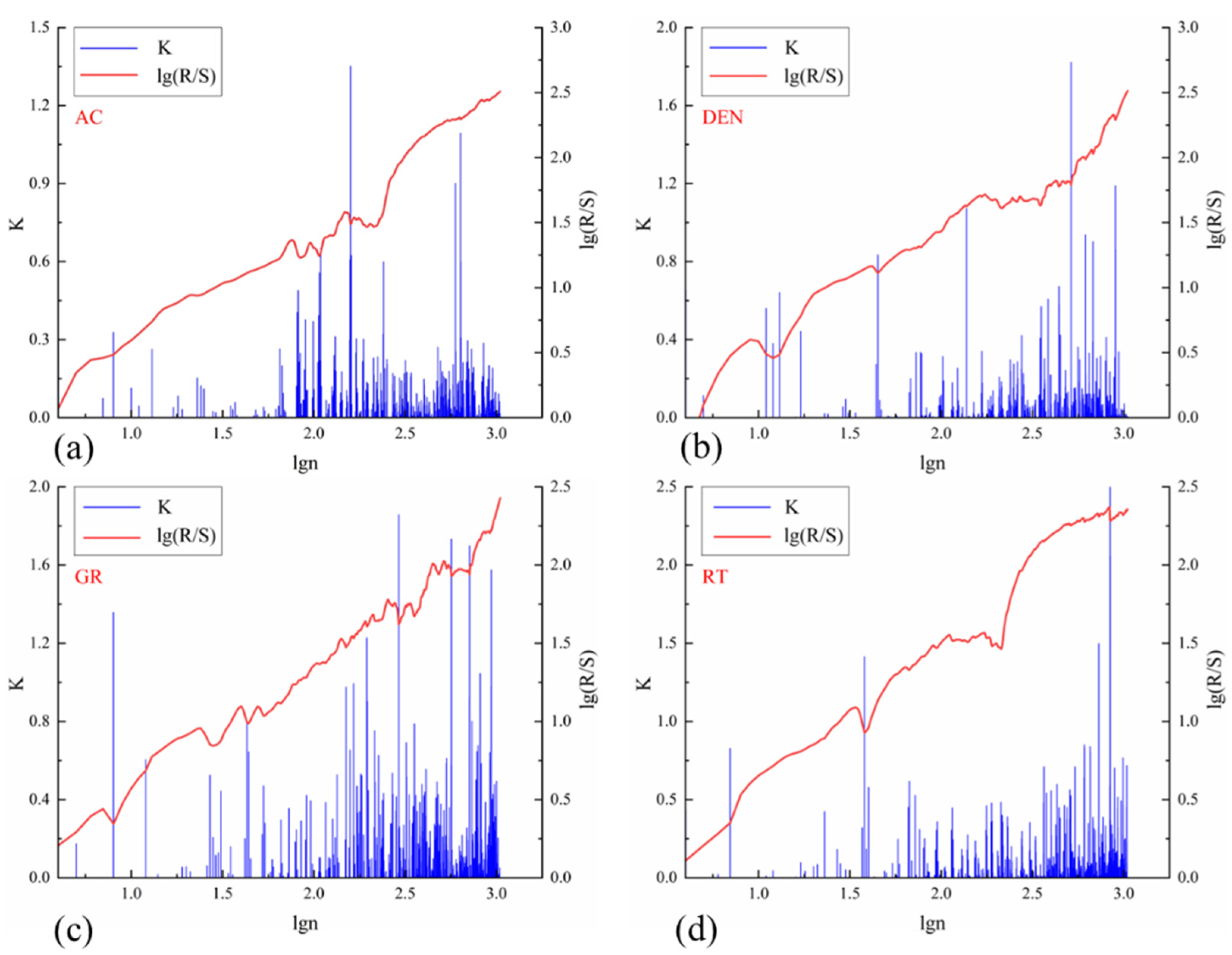

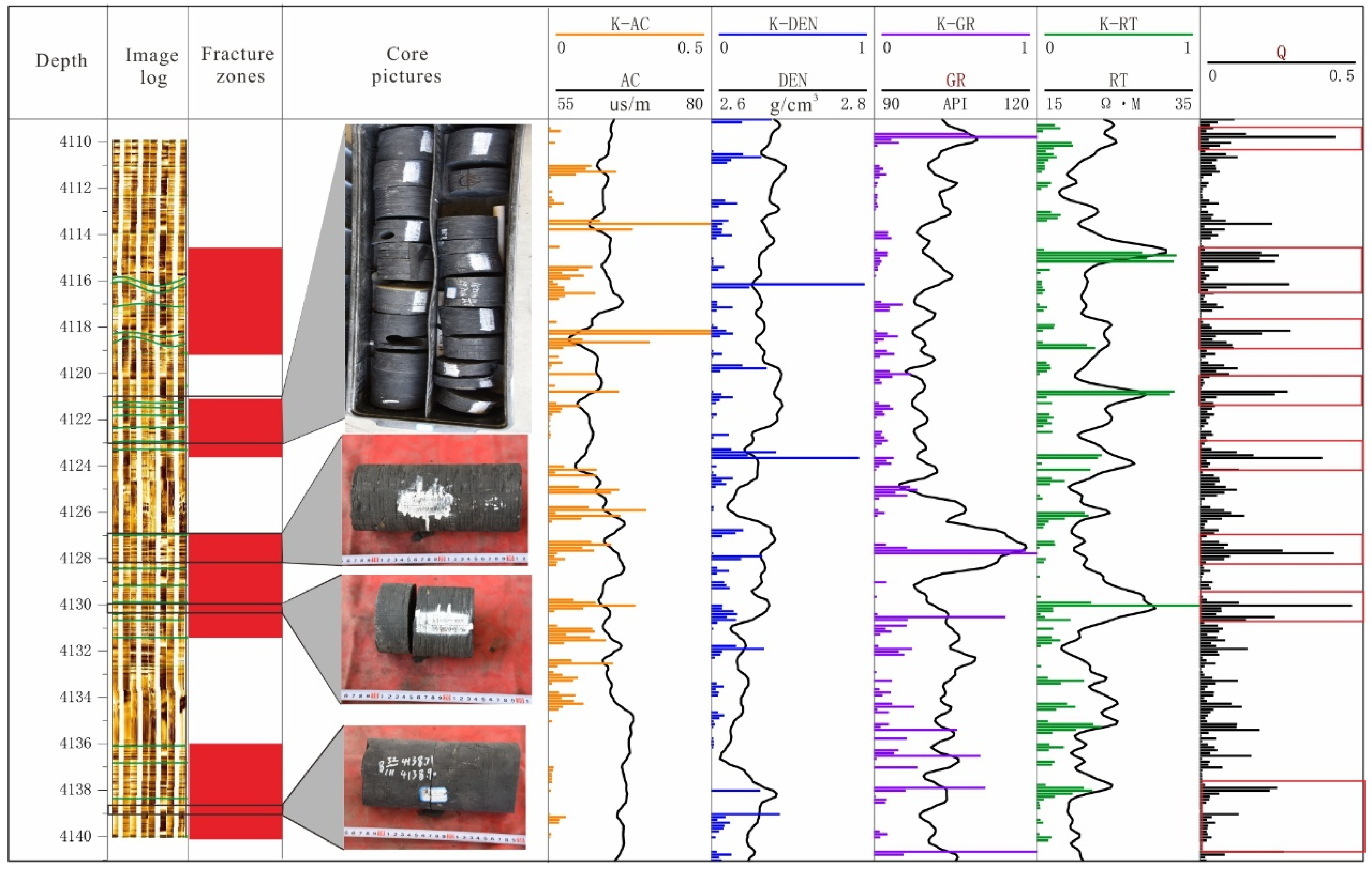

3.3. Prediction Results of Fracture Development

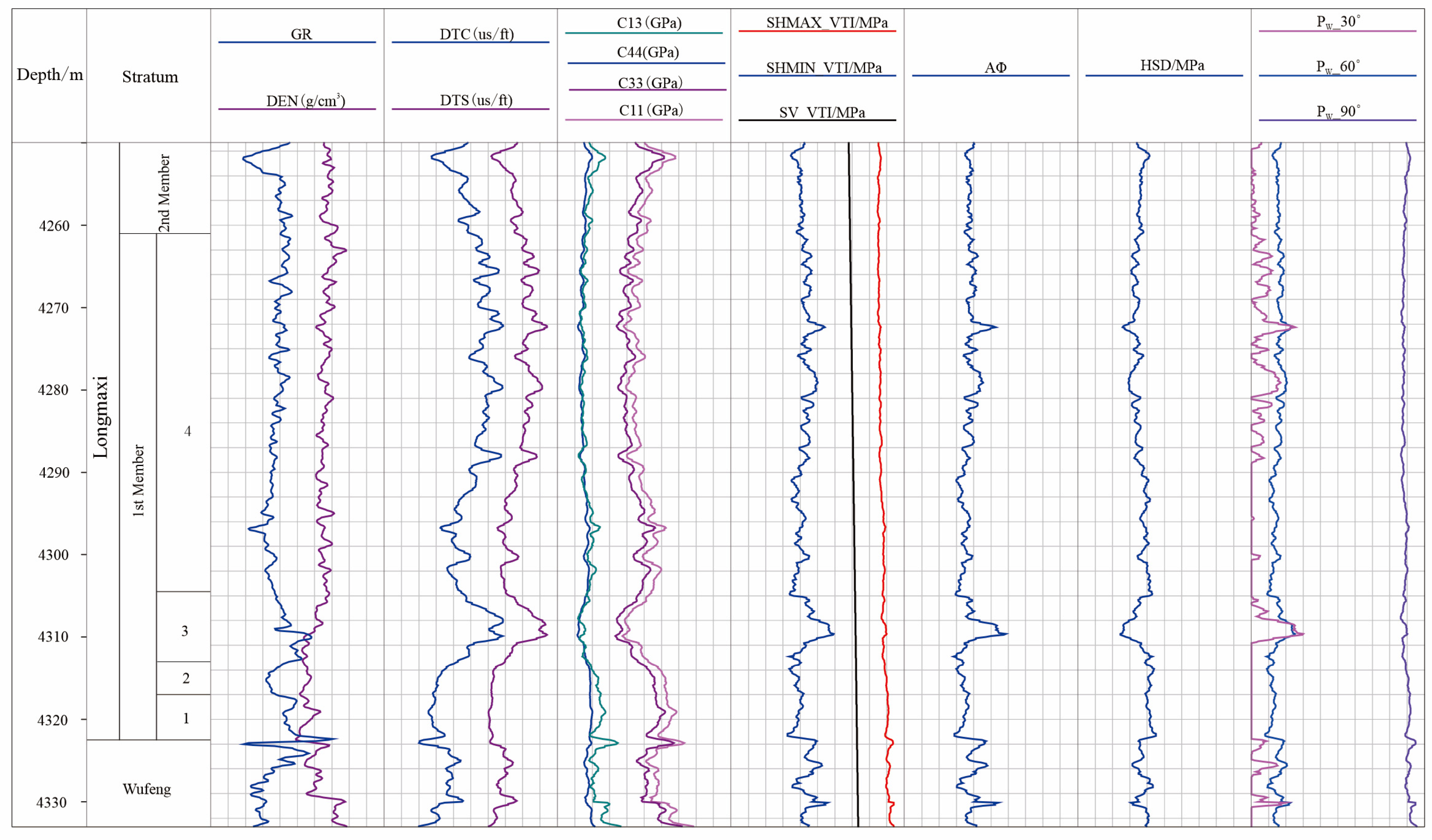

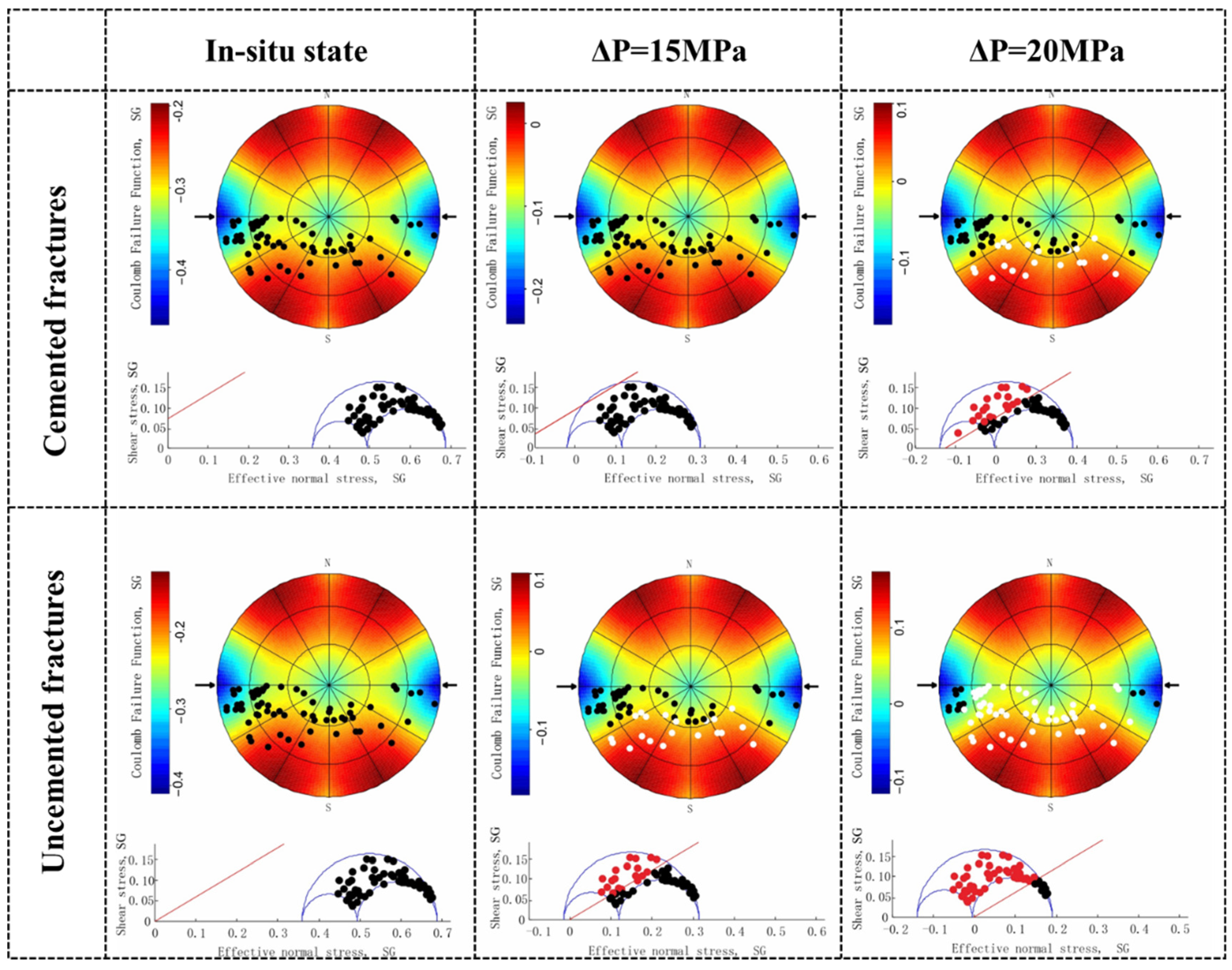

3.4. Analysis of Fracture Stress and Activity

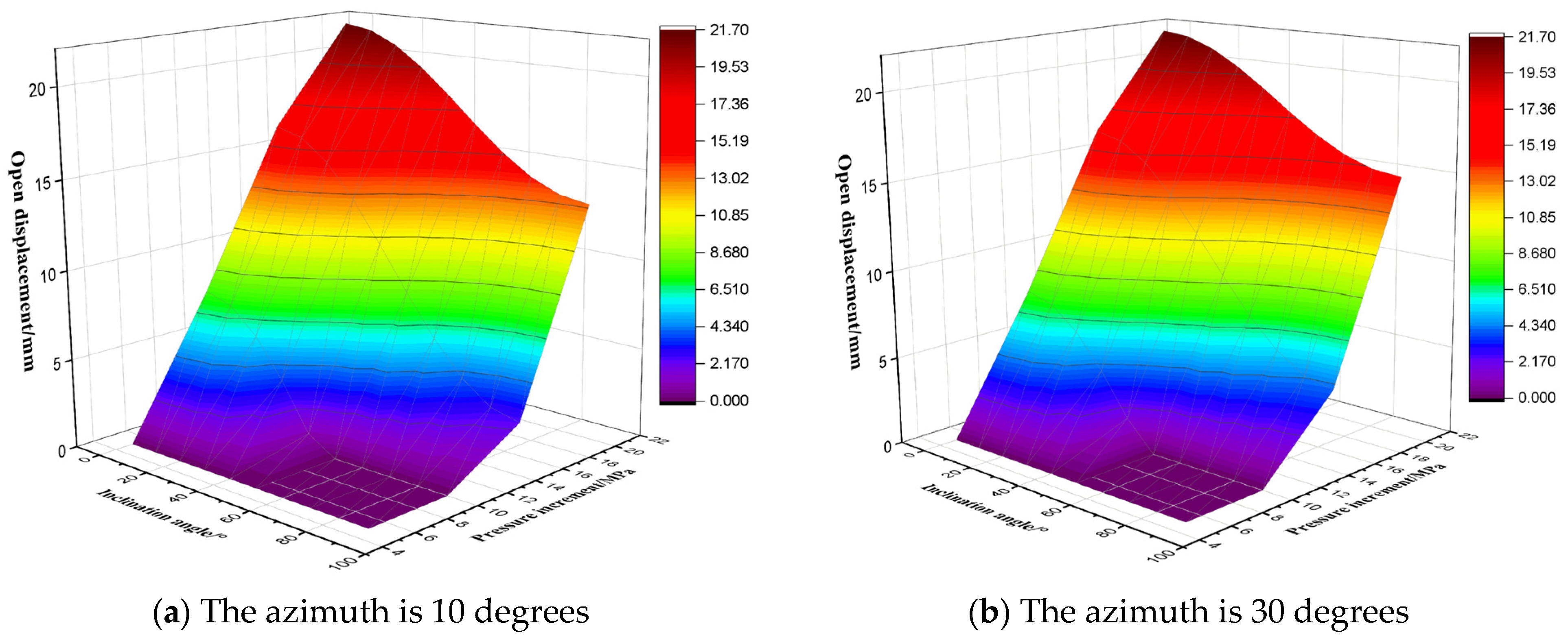

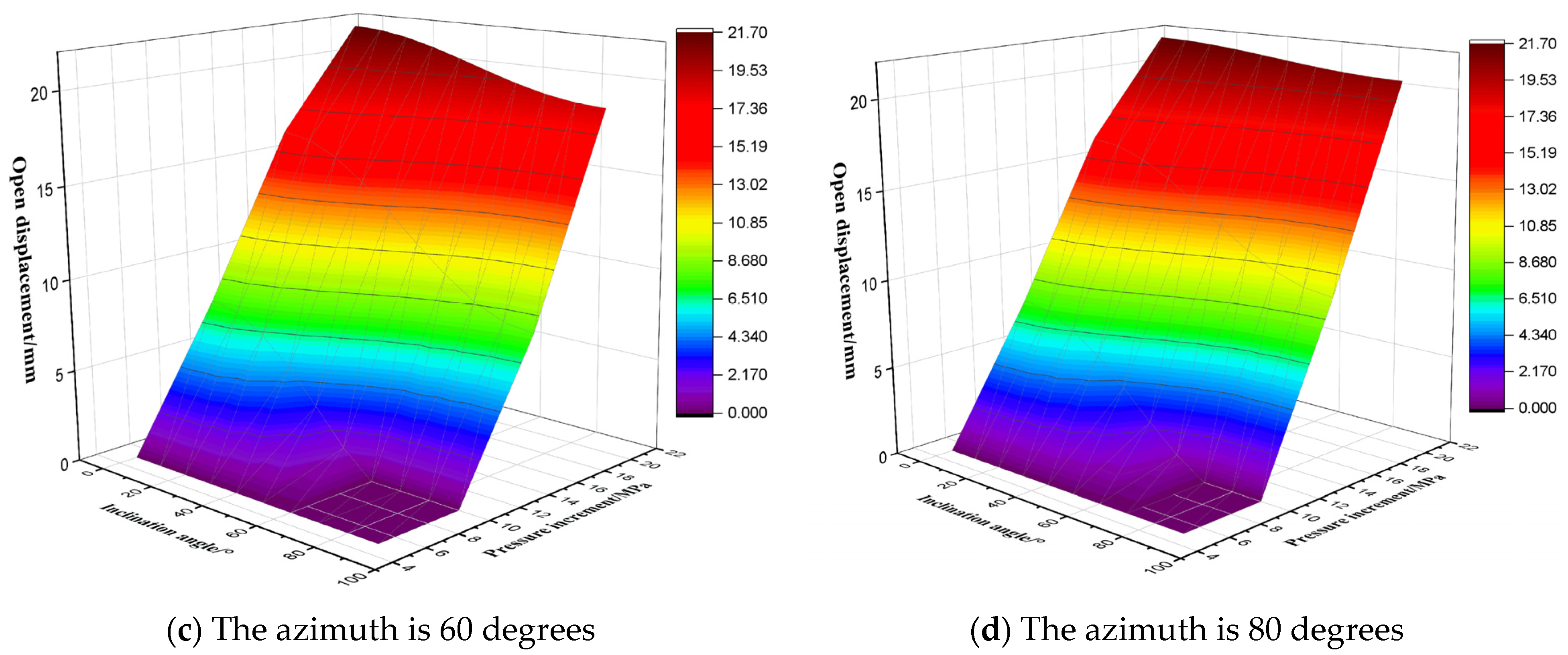

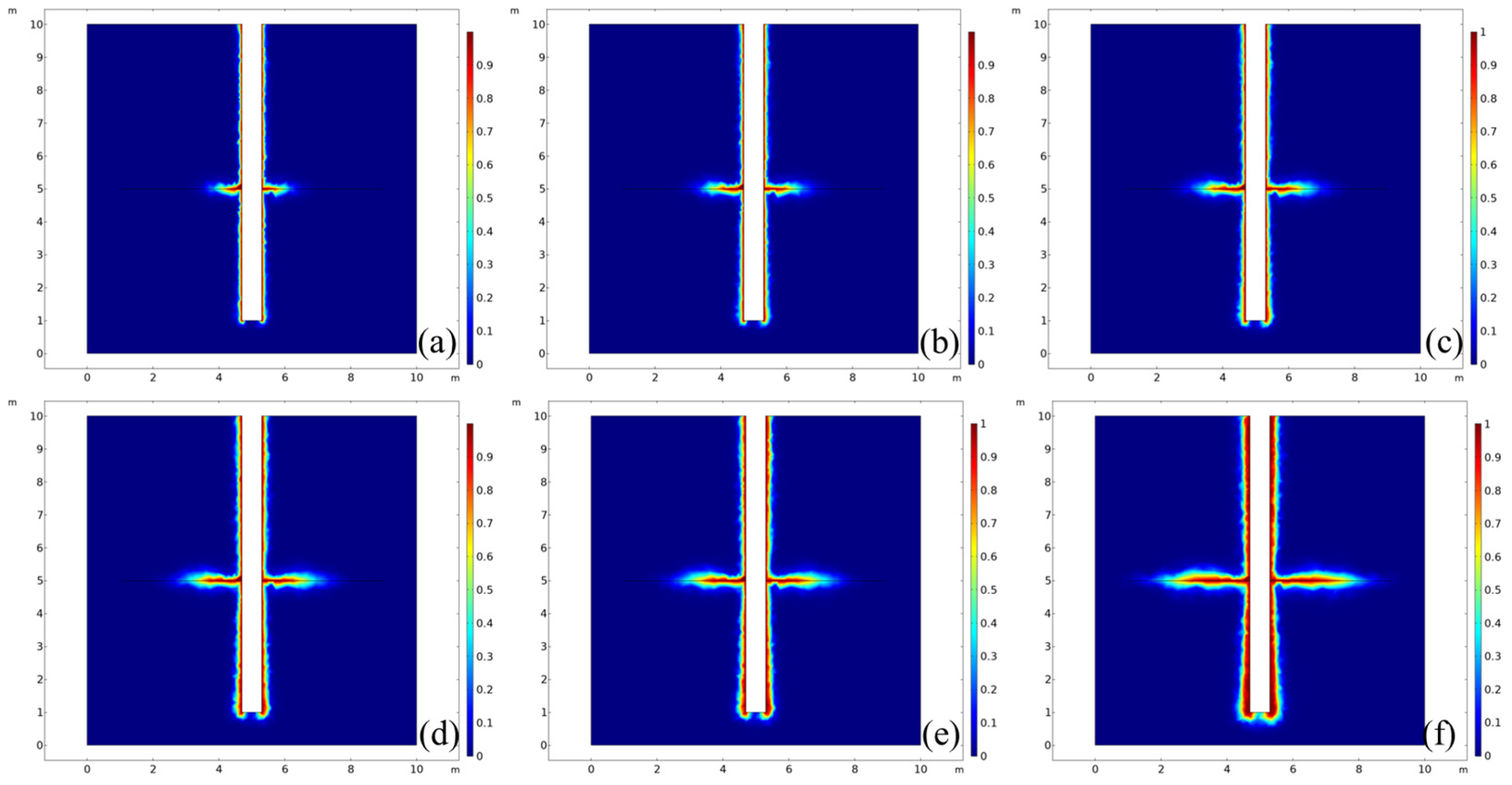

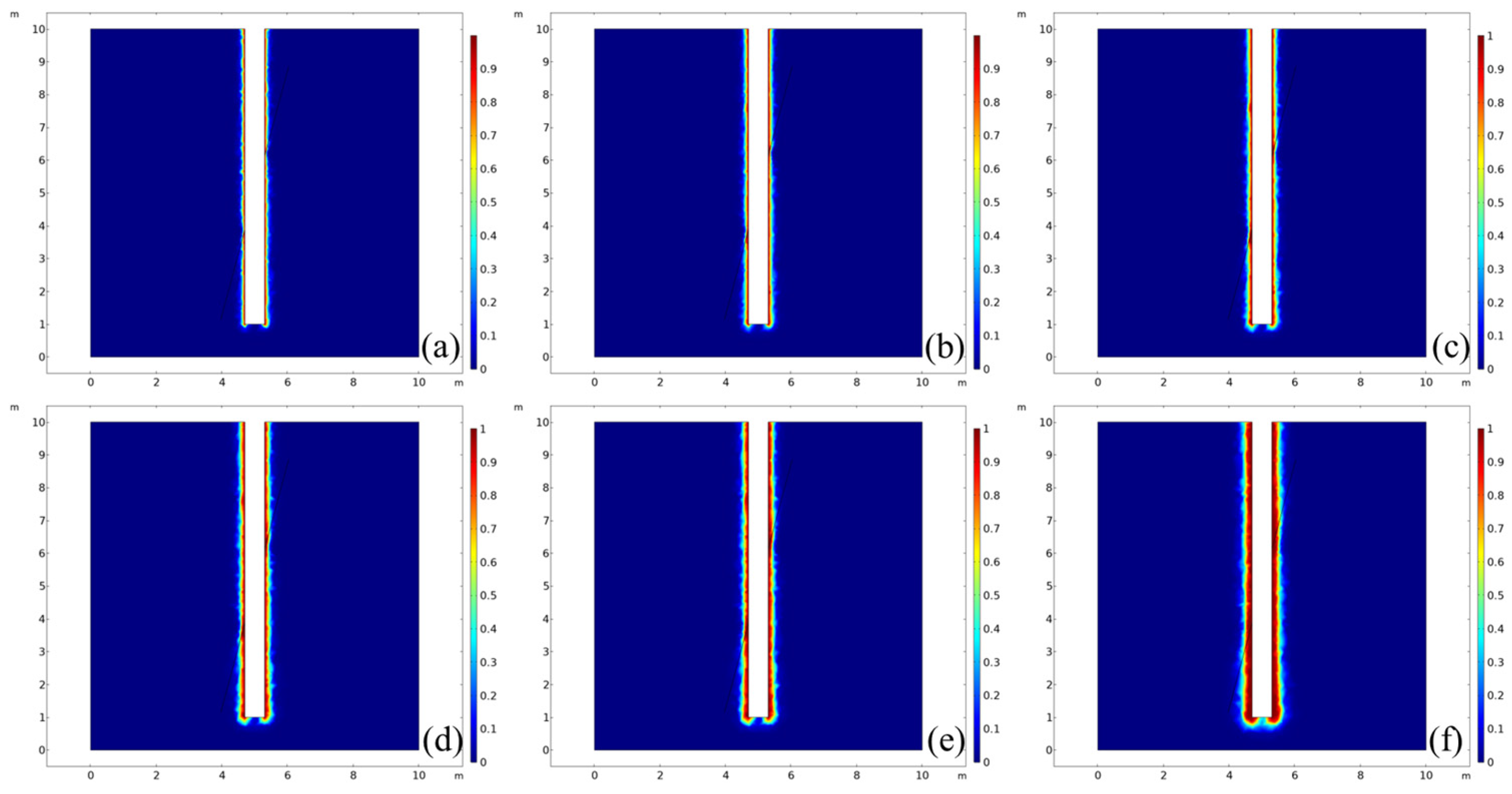

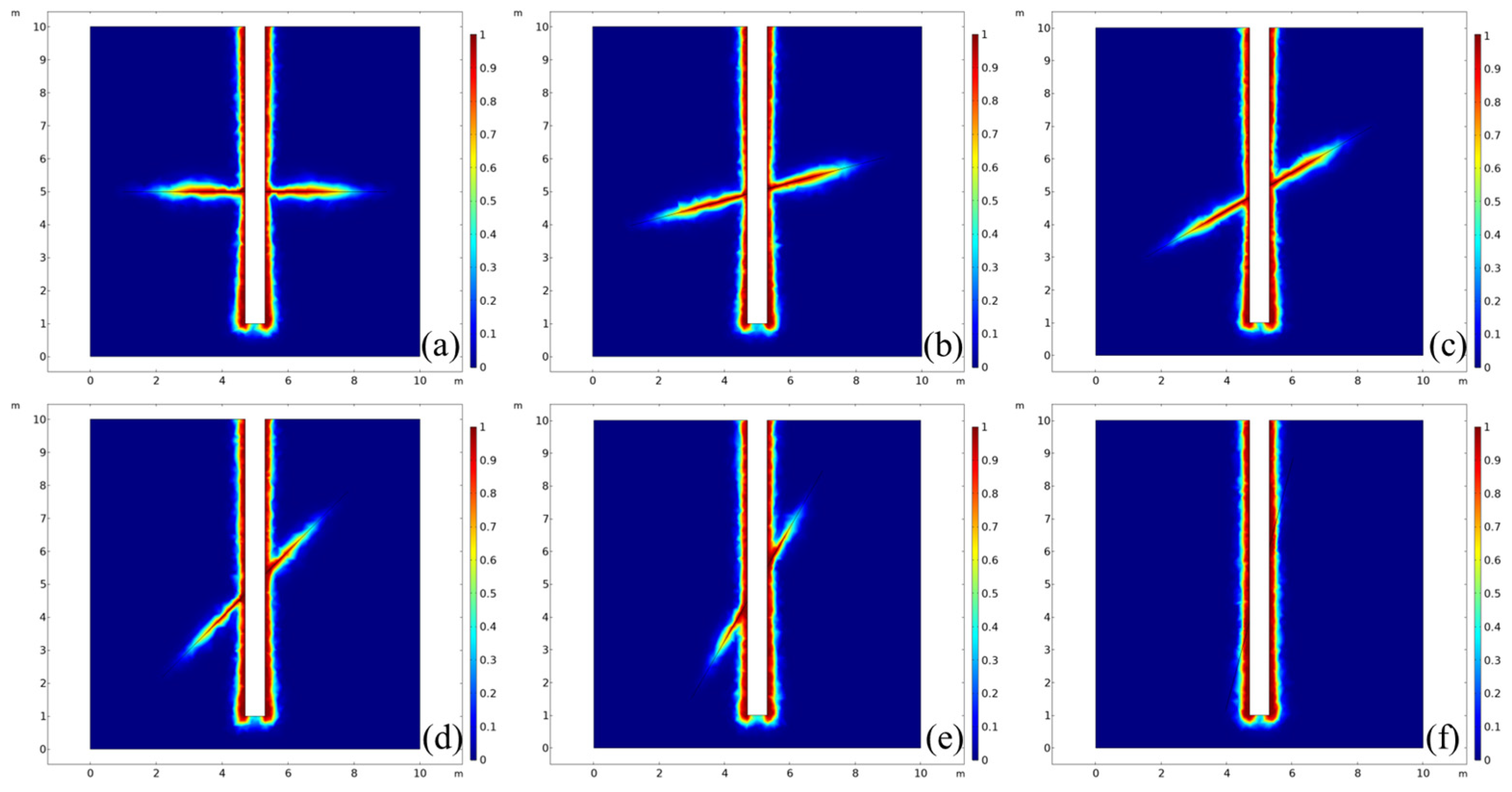

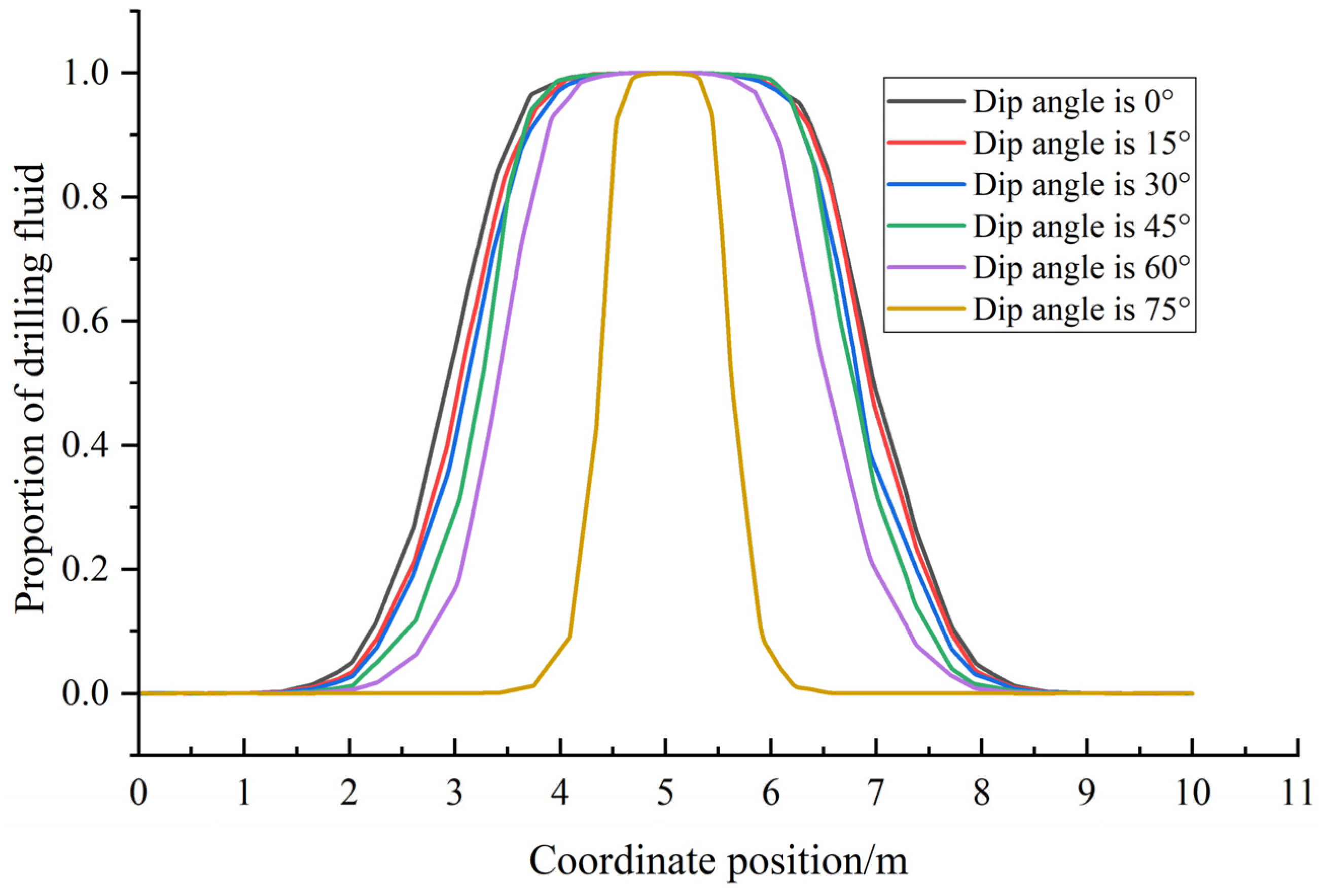

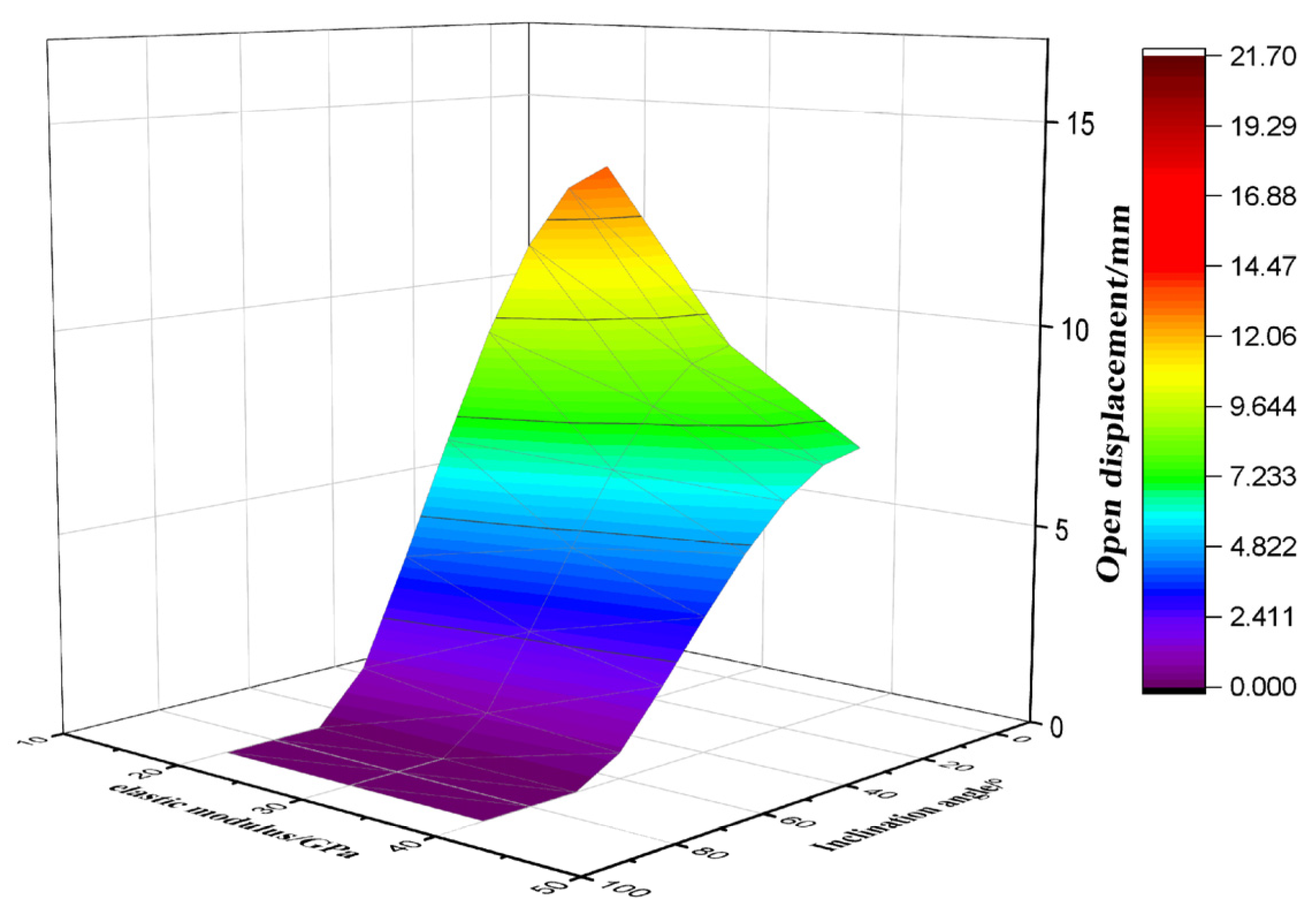

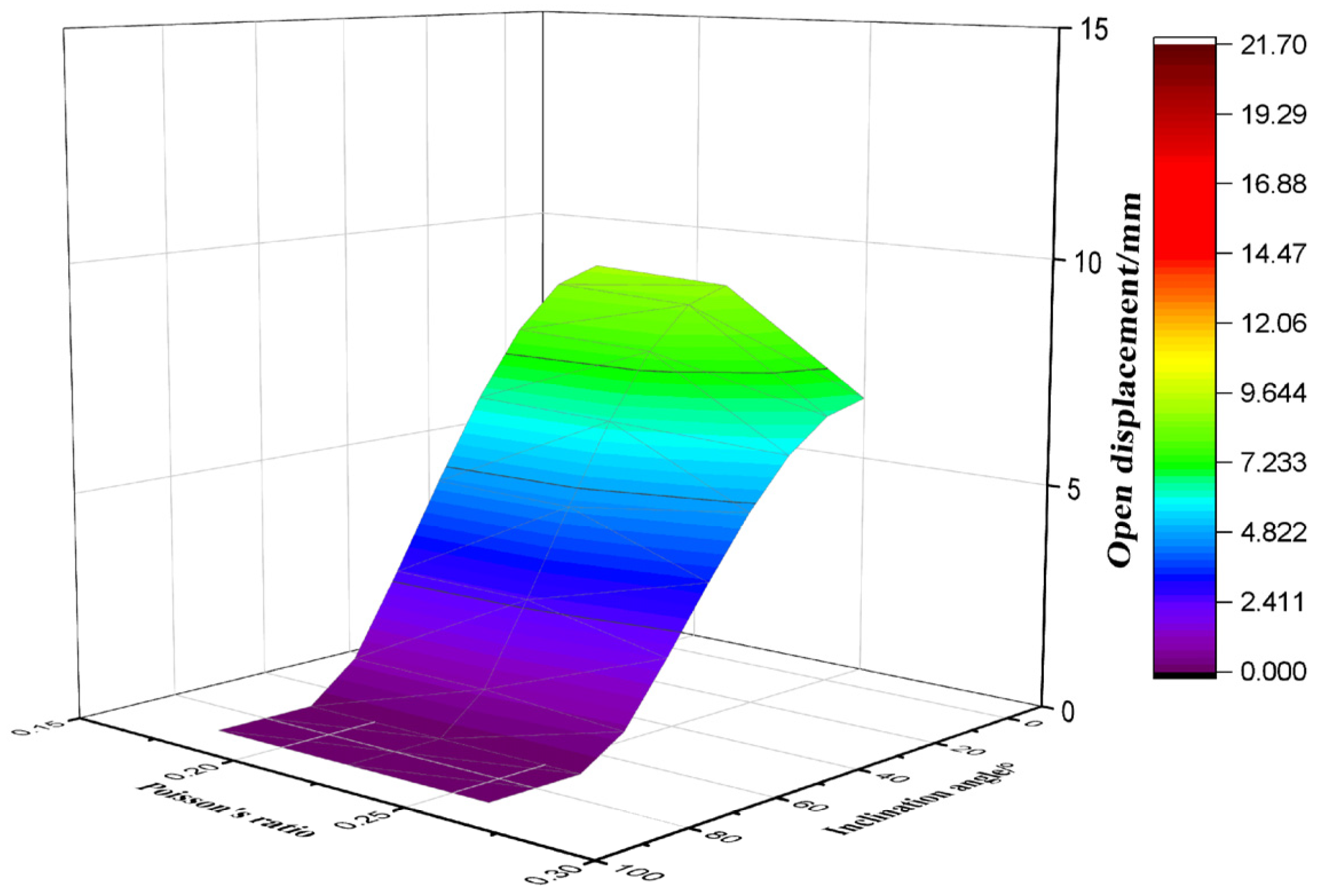

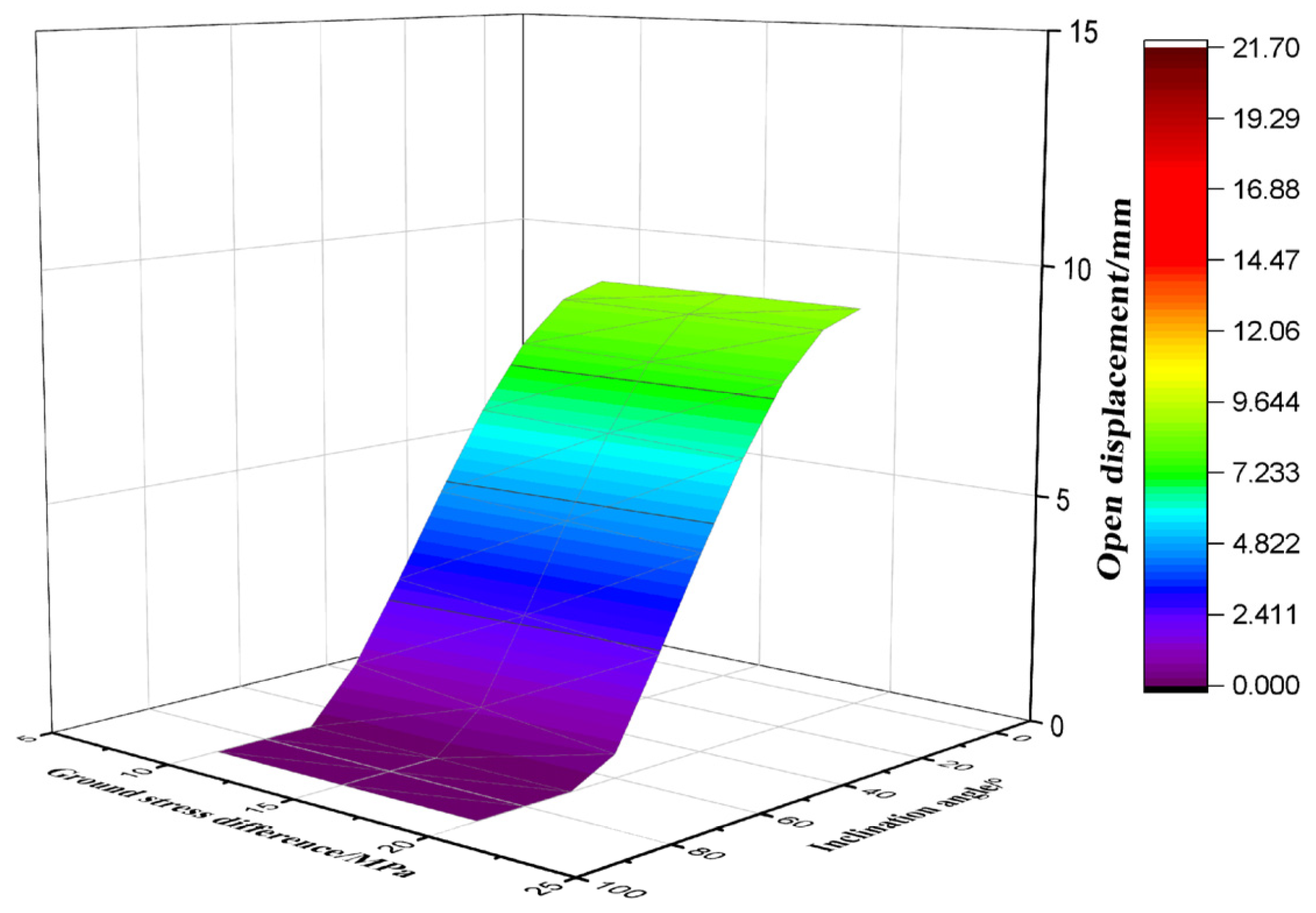

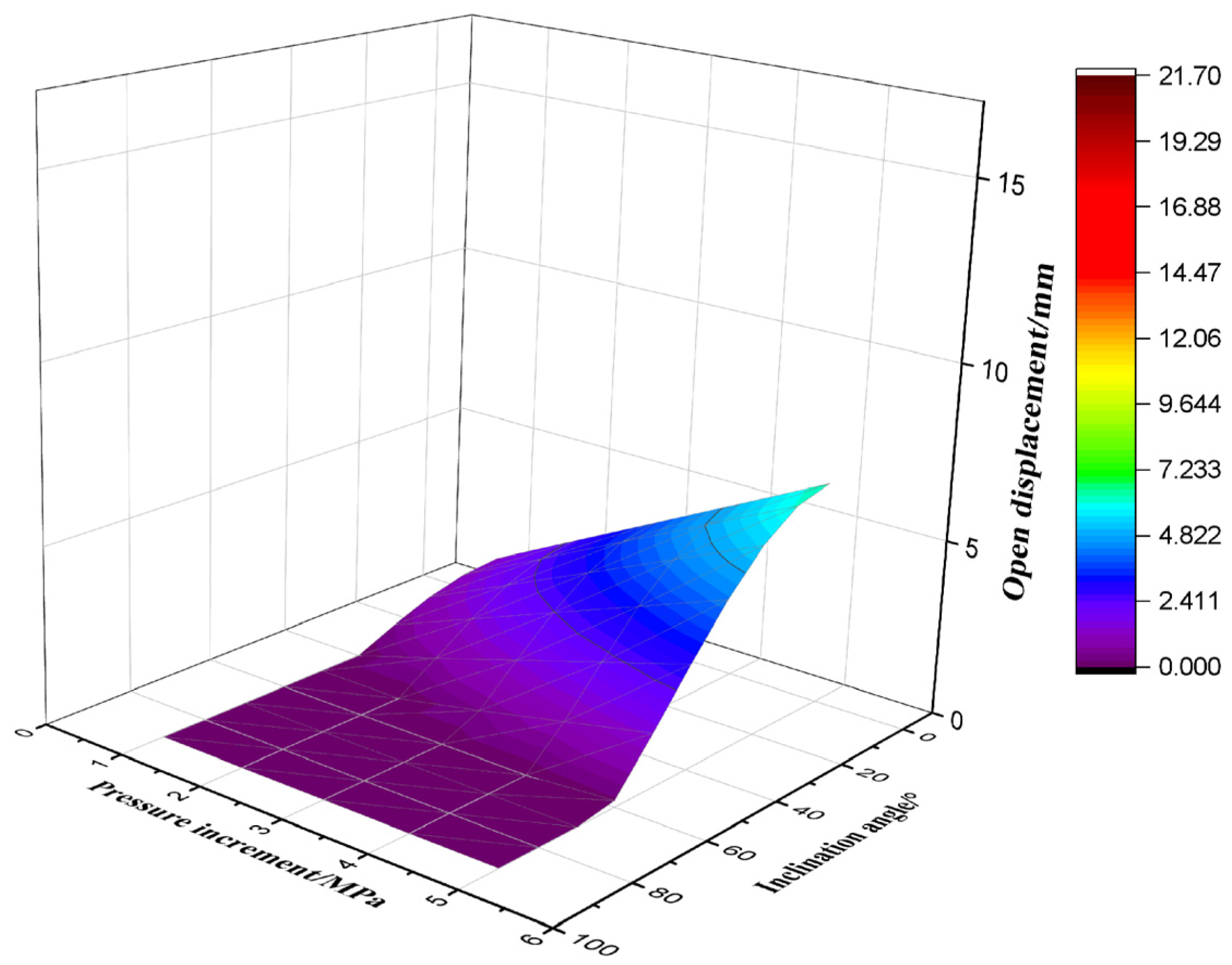

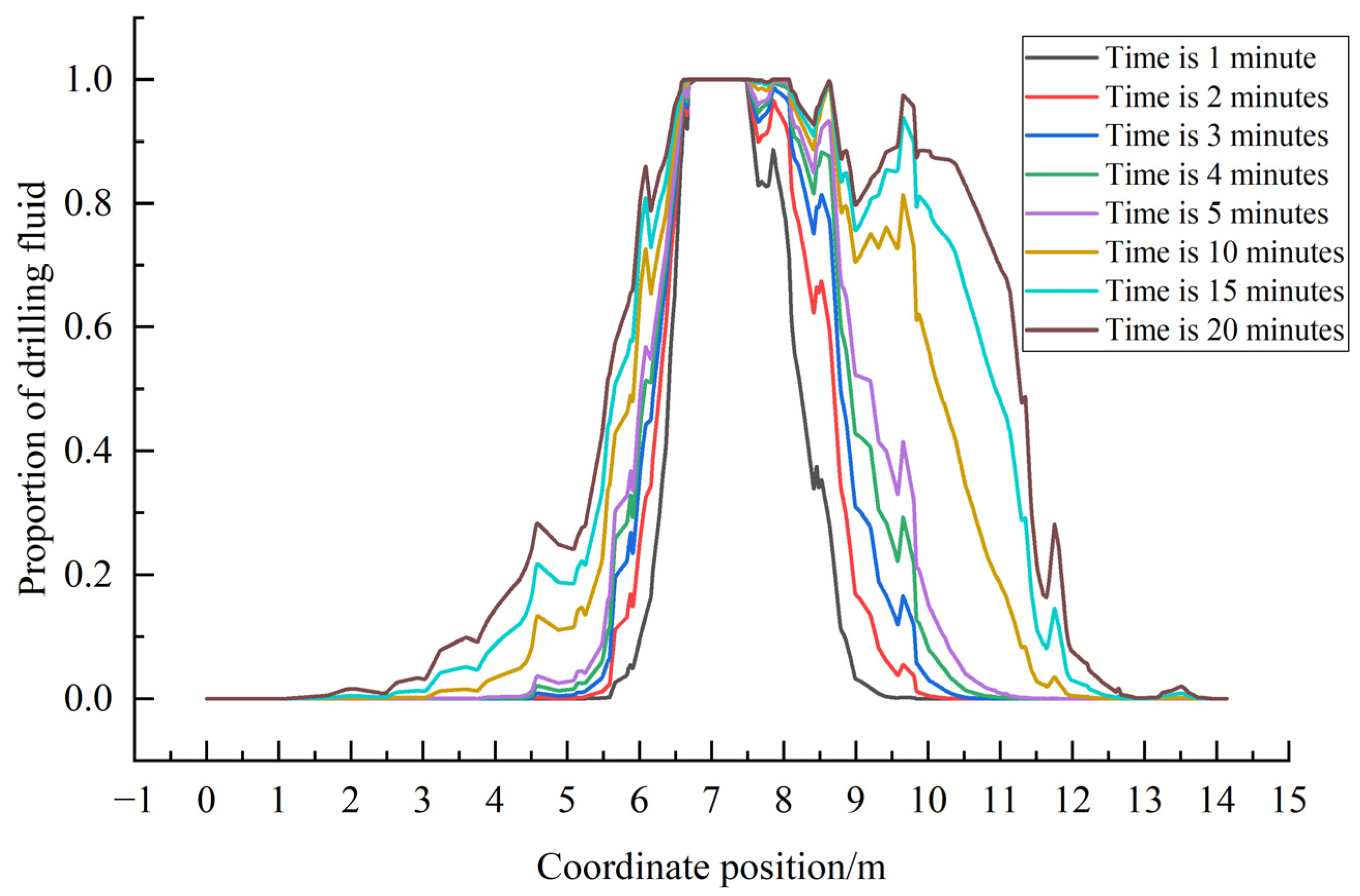

3.5. Evaluation of Displacement of the Activated Fractures

3.6. Discussion

4. Results

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The observation results of the core of Longmaxi Formation in the Luzhou Block show that a large number of vertical fractures are developed in this area, with short longitudinal extension and small opening, accounting for 78.1%. Due to the limited accuracy of imaging logging identification, this type of fracture cannot be accurately identified. The fractures are mainly characterized by high-angle fractures (51.79%) and low-angle fractures (44.64%), and most of them are unfilled, and the fracture strike is mainly NE-SW and ~E-W. This characterization offers a geological basis for understanding the potential pathways for drilling fluid invasion in the Luzhou Block.

- (2)

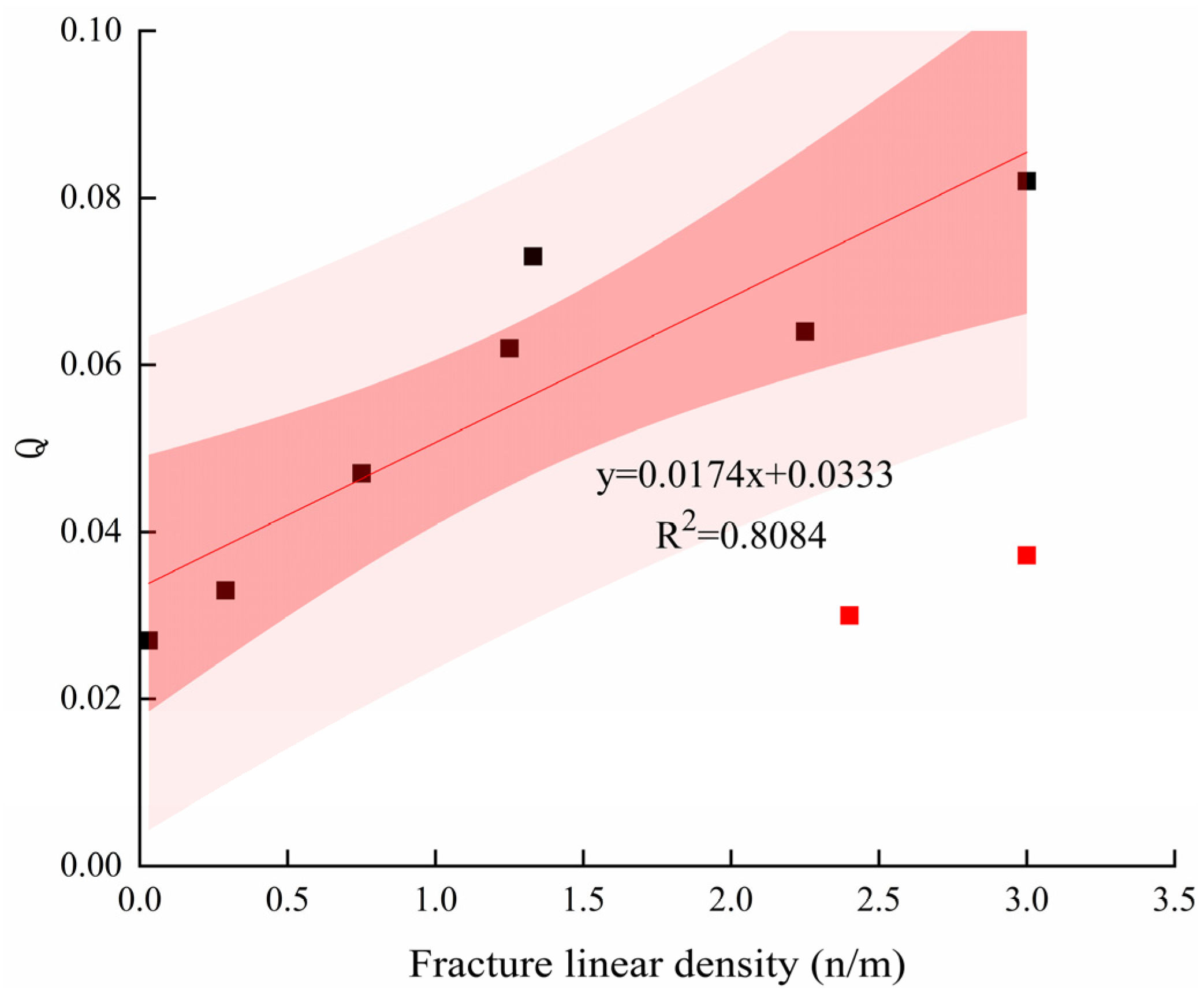

- The R/S analysis method mainly determines the fracture development location by detecting the mutation points on conventional logging curves, and further obtains the fracture development index Q by combining the FDM and entropy weight method. The results show that the value of this parameter ranges from 0 to 0.6 in the Longmaxi Formation. The linear relationship between parameter Q and fracture linear density is obvious, and the correlation coefficient can reach 80.84%, indicating that the fracture development index can represent the degree of fracture development. This method provides a cost-effective alternative for preliminary fracture identification when image logs are unavailable.

- (3)

- In the Fuji syncline, two groups of natural fractures dominate: Set A (~NE-SW trending) and Set B (~NW-SE trending), and NW-SE direction is the dominant fracture orientation, When drilling or fracturing, pore pressure increment larger than 15–20 MPa is easy to maintain a high natural fracture opening ratio of the reservoir, which is conducive to shale gas production and efficiency while the unfavorable to lead to the risk incident of drilling fluid loss and wellbore collapse. This pressure window serves as a critical reference for managing bottomhole pressure to balance productivity and safety.

- (4)

- Based on the results of imaging logging, the error analysis of the R/S fracture identification results is carried out. It is concluded that the reasons for the mismatch of R/S fracture identification results mainly lie in the longitudinal heterogeneity of the reservoir, the occurrence of fractures, and the interpretation accuracy of identification methods. However, the R/S method is still a convenient and effective way to identify the degree of reservoir fracture development, because the conventional logging parameters are easy to obtain and have strong continuity, and the entropy weight method can combine multiple logging parameters to comprehensively analyze and predict reservoir fractures. Therefore, it presents a practical and cost-efficient approach for preliminary fracture evaluation in areas with limited data availability.

- (5)

- The activity of fractures varies with the occurrence of fractures and the degree of cementation. With the parameters of research block geostress, the degree of cementation, north–south fractures, and fracture angle between 30°~45° have poorer fracture activity and are more stable. These results establish a foundational understanding for evaluating the geomechanical stability of fractured shale reservoirs.

- (6)

- Under the action of increasing geostress and fluid pressure inside the fracture, the displacement of fracture opening varies with the dip angle and fracture azimuth, resulting in significant differences in the rate and degree of drilling fluid leakage. The risk of high-angle fracture leakage is in the low value zone. This understanding is crucial for informing the strategic design of drilling fluid systems in complex fractured formations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shen, W.; Ma, T.; Li, X.; Sun, B.; Hu, Y.; Xu, J. Fully coupled modeling of two-phase fluid flow and geomechanics in ultra-deep natural gas reservoirs. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 43101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tao, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Jiang, S.; Wang, D.; Zhao, X. Prospect of deep shale gas resources in China. Nat. Gas Ind. 2021, 41, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, S.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, L. Deep shale gas in China: Geological characteristics and development strategies. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 1903–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Li, X.; Guo, W.; Ju, W.; Cui, Y.; Liu, Z.; Qian, C.; Shen, W. Characteristics and Dominant Factors for Natural Fractures in Deep Shale Gas Reservoirs: A Case Study of the Wufeng-Longmaxi Formations in Luzhou Block, Southern China. Lithosphere 2022, 2022, 9662175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Pan, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, F.; Han, L.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Y.; Li, H.; Li, W. Study on the effect of cemented natural fractures on hydraulic fracture propagation in volcanic reservoirs. Energy 2022, 241, 122845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Duan, R. Numerical simulation of pressure evolution and migration of hydraulic fracturing fluids in the shale gas reservoirs of Sichuan Basin, China. J. Hydrol. 2020, 588, 125082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.I.; Oyeneyin, B.; Bartlett, M.; Njuguna, J. Prediction of casing critical buckling during shale gas hydraulic fracturing. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 185, 106655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Lyu, W.; Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Weng, J.; Yue, F.; Zu, K. Natural fractures and their influence on shale gas enrichment in Sichuan Basin, China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Li, C.; Li, C.; Xu, C.; Jiu, K.; Zeng, W.; Wu, L. Fracture development in shale and its relationship to gas accumulation. Geosci. Front. 2012, 3, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, W.; Hu, Q.; Zhai, G.; Wang, R.; Xu, X.; Meng, F.; Liu, Y.; Bai, L. Developmental characteristics and controlling factors of natural fractures in the lower paleozoic marine shales of the upper Yangtze Platform, southern China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 76, 103191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Nie, H.; Zhang, Y. The main factors of shale gas enrichment of Ordovician Wufeng Formation-Silurian Longmaxi Formation in the Sichuan Basin and its adjacent areas. Earth Sci. Front. 2016, 23, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yang, H.; Wei, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yang, H.; Yan, W.; Fu, L. Wellbore instability in naturally fractured formations: Experimental study and 3D numerical investigation. Gas Sci. Eng. 2024, 124, 205265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Schmitt, D.; Li, W. A program to forward model the failure pattern around the wellbore inelastic and strength anisotropic rock formations. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2022, 151, 105035. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Ding, W.; Xiao, Z.; Dai, J. Advances in comprehensive characterization and prediction of reservoir fractures. Prog. Geophys. 2019, 34, 2283–2300. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Ju, W.; Niu, X.; Feng, S.; You, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, S.; Luan, W. Prediction of natural fracture in shale oil reservoir based on R/S analysis and conventional logs. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 15, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ju, W.; Yin, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Yang, H.; Xu, K.; Luan, W. Natural fracture prediction in Keshen 2 ultra-deep tight gas reservoir based on R/S analysis, Kuqa Depression, Tarim Basin. Geosci. J. 2021, 25, 525–536. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Zhao, S.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Xia, Z.; Wu, T.; Luo, C.; Fan, T.; Yu, L. Main controlling factors of enrichment and high-yield of deep shale gas in the Luzhou Block, southern Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2019, 39, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Tang, X.; Wu, W.; Li, Z.; Xue, Z.; Shi, X.; Guo, J. Coupling key factors of shale gas sweet spot and research direction of Geology-engineering integration in southern Sichuan. Earth Sci. 2022, 48, 110–129. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Ding, W.; Tian, Q.; Xu, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, B.; Jiao, B. Developmental characteristics and dominant factors of natural fractures in lower Silurian marine organic-rich shale reservoirs: A case study of the Longmaxi formation in the Fenggang block, southern China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 192, 107277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, W.; Sun, W. Tectonic fractures in the Lower Cretaceous Xiagou Formation of Qingxi Oilfield, Jiuxi Basin, NW China Part one: Characteristics and controlling factors. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2016, 146, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ding, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; He, J.; Zeng, W.; Dai, P. Analysis of developmental characteristics and dominant factors of fractures in Lower Cambrian marine shale reservoirs: A case study of Niutitang formation in Cen’gong block, southern China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2016, 138, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Ding, W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Tian, L.; Liu, J.; Shi, S.; Jiao, B.; Cui, L. Fracture development characteristics and controlling factors for reservoirs in the Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation marine shale of the Sangzhi block, Hunan Province, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 184, 106470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Li, X. Fractures in sandstone reservoirs with ultra-low permeability: A case study of the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin, China. AAPG Bull. 2009, 93, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Li, F.; Yang, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Chen, L.; Du, Z. Development characteristics of fractures in Jurassic tight reservoir in Dibei area of Kuqa depression and its reservoir-controlling mode. Acta Pet. Sin. 2015, 36, 102–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhao, S.; Fan, C.; Xia, Z.; Ji, C.; Zhang, C.; Cao, L. Fracture characteristics of the Longmaxi Formation shale and its relationship with gas-bearing properties in Changning area, southern Sichuan. Acta Pet. Sin. 2021, 42, 428–446. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Weng, J.; Lyu, W. The significance and characteristics of natural fractures of the Shale in Changning area, Sichuan province. Geol. Surv. Res. 2016, 39, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Zeng, L.; Shi, X.; Wu, W.; Tian, H.; Xue, M.; Luo, L. Characteristics and main controlling factors of natural fractures in marine shale in Luzhou area, Sichuan Basin. Earth Sci. 2022, 48, 2630–2642. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, H.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Ba, D.; Wang, Q. Quantitative fracture evaluation method based on core-image logging: A case study of Cretaceous Bashijiqike Formation in ks2 well area, Kuqa depression, Tarim Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2016, 43, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H. Application of imaging well logging data in prediction of structural fractures. Nat. Gas Ind. 2006, 26, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gou, Q.; Xu, S.; Hao, F.; Lu, Y.; Shu, Z.; Wang, Y. Research on mud shale fractures based on image logging: A case study of Jiaoshiba area. Bull. Geol. Sci. Technol. 2020, 39, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Cui, H.; Han, L.; Hou, L.; Bai, J.; Wang, C.; Zhan, H. Determination and Application of Stress States Based on Finite Element Techniques: A Case Study of the Longmaxi Formation in the Luzhou Block, Sichuan Basin. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 44347–44364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Ding, W.; Liu, J.; Tian, M.; Yin, S.; Zhou, X.; Gu, Y. A fracture identification method for low-permeability sandstone based on R/S analysis and the finite difference method: A case study from the Chang 6 reservoir in Huaqing oilfield, Ordos Basin. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 174, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, A.; Roman, H.E.; Raicich, F.; Crisciani, F. Long-time correlations of sea-level and local atmospheric pressure fluctuations at Trieste. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2005, 347, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.G.V.; Andrade, R.F.S. Rescaled Range analysis of pluviometric records in Northeast Brazil. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 1999, 63, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; North, C.P. Fractals and their applicability in geological wireline log analysis. J. Pet. Geol. 1996, 3, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Li, L.; Chen, W.; He, Y. Application of the variable scale fractal technique in fracture prediction and reservoir evaluation. Oil Gas Geol. 2008, 29, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, L.; Liang, W. Application of R/S analysis method in reservoir fracture prediction: A case study of Chang-73 reservoir in Dingbian Dongrengou. Unconv. Oil Gas 2020, 7, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z. Application of R/S analysis in the evaluation of vertical reservoir heterogeneity and fracture development. Exp. Pet. Geol. 2000, 22, 382–386. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Duan, G.; Wan, Y.; Guo, X.; Guo, W.; Cui, Y. Influencing factors and prevention measures of casing deformation in deep shale gas wells in Luzhou block, southern Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Well | Top (m) | Bottom (m) | Thick (m) | Number | Linear Density (m/m2) | Q |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y7 | 4115 | 4119 | 4 | 5 | 1.25 | 0.062 |

| 4121 | 4123.5 | 2.5 | 6 | 2.40 | 0.034 | |

| 4127 | 4131.5 | 4.5 | 6 | 1.33 | 0.073 | |

| 4136 | 4140 | 4 | 3 | 0.75 | 0.047 | |

| L2 | 4288 | 4295 | 7 | 2 | 0.29 | 0.033 |

| 4295 | 4296 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0.082 | |

| 4203 | 4310 | 7 | 3 | 0.03 | 0.027 | |

| 4299 | 4301 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 0.037 | |

| 4313 | 4317 | 4 | 9 | 2.25 | 0.064 |

| Parameters | Value | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fracture length | 10 m | Formation pressure | 80 MPa |

| Elasticity modulus of rock | 35 GPa | Vertical stress | 101 MPa |

| Poisson’s ratio of rock | 0.23 | Maximum horizontal principal stress | 108 MPa |

| Cohesion strength of fracture | 0 MPa | Minimum horizontal principal stress | 93 MPa |

| Parameters | Value | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| density (g/cm3) | 1.85 | dynamic shear (Pa) | 61.5 |

| funnel viscosity (s) | 40~60 | plastic viscosity (mPa∙s) | 50 |

| cake thickness (mm) | 0 | fluid compressibility (Pa−1) | 7.58 × 10−10 |

| Parameters | Value | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| σH (MPa) | 108 | elastic modulus (GPa) | 30 |

| σh (MPa) | 93 | Poisson’s ratio | 0.22 |

| σv (MPa) | 101 | pore pressure (MPa) | 80 |

| drilling fluid column pressure (MPa) | 95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Tong, Z.; Cui, H. Prediction Research of Wellbore Fractures and the Impact on Drilling Fluid Leakage. Processes 2025, 13, 3991. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123991

Wang C, Li S, Liu Z, Xu Y, Zheng X, Tong Z, Cui H. Prediction Research of Wellbore Fractures and the Impact on Drilling Fluid Leakage. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3991. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123991

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Chunhua, Shibin Li, Zhaoyi Liu, Yunlong Xu, Xiaoqing Zheng, Ziyang Tong, and Hanzhuo Cui. 2025. "Prediction Research of Wellbore Fractures and the Impact on Drilling Fluid Leakage" Processes 13, no. 12: 3991. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123991

APA StyleWang, C., Li, S., Liu, Z., Xu, Y., Zheng, X., Tong, Z., & Cui, H. (2025). Prediction Research of Wellbore Fractures and the Impact on Drilling Fluid Leakage. Processes, 13(12), 3991. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123991