Abstract

To address petroleum security concerns and improve its energy structure, China continues to expand its utilization of coal-to-liquid (CTL) technology. While integrating carbon capture and storage (CCS) is essential to reduce the CO2 emissions from CTL, the high CO2 abatement cost remains one major barrier to its large-scale implementation. Carbon pricing could improve the cost-effectiveness and competitiveness of CTL-CCS. The impacts of the upstream carbon tax and the downstream carbon price are discussed, considering two indirect coal liquefaction routes: a once-through synthesis process with electricity generation from unreacted syngas and a process with recycling unreacted syngas. The financial performance, with or without CCS, was evaluated using process simulation in Aspen Plus 11.1 and a cost estimation model. First, the product cost of recycling synthesis is consistently lower than of once-through synthesis, indicating better economic efficiency. Second, adopting CCS without a carbon price significantly undermines economic performance. To keep the product cost increase below 10%, the upstream carbon tax and the downstream carbon price should be less than 100 and 120 RMB/tCO2, respectively. Third, the upstream carbon tax can quickly increase product costs and reduces NPV and IRR, but fails to incentivize actual emissions reduction. Fourth, the downstream carbon price can effectively drive actual emissions reduction, particularly at a higher carbon price. Finally, without a sufficiently high carbon price, enterprises lack necessary incentive to implement CCS. When the carbon price reaches 196 RMB/tCO2 (approximately 30 USD/tCO2), CCS becomes a cost-effective option for the CTL process.

1. Introduction

China lacks sufficient domestic oil and natural gas resources, but is relatively rich in coal reserves. In 2023, the country imported 564 million tonnes of crude oil [1], and China’s foreign oil dependence has remained above 70% in recent years. This heavy reliance poses significant risks to the national oil security, economic security, and national security of the entire country in the event of import disruptions. Establishing a diversified oil supply system is therefore crucial to mitigating such risks. One key strategy is to actively develop substitutes for crude oil and vigorously promote coal-to-liquid (CTL) technology. In 2017, the National Energy Administration of China announced a target to achieve a CTL production capacity of 13 million tons/year by 2020 [2], and planned the construction of four CTL demonstration projects over the following five years. More recently, in 2024, six government departments jointly issued the Opinions on Strengthening the Clean and Efficient Utilization of Coal, emphasizing the construction of strategic CTL and the acceleration of gas bases, and calling for enhanced production capacity and technical reserves for CTL and gas production [3]. Despite these initiatives, one major challenge associated with CTL is its high CO2 emissions, especially under increasing emission reduction pressure.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) could be a vital choice for future clean energy production and climate change alleviation [4,5,6]. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) [7], CCS could contribute up to 12% of global CO2 reduction by 2050. CCS technologies are recognized to reduce carbon emissions under supportive policy frameworks in China [8]. Several CCS projects have been launched in recent years, including those in China. In 2022, China’s first million-tonne-per-year integrated CCS project entered full operation. Additionally, Hua Neng initiated a 1.5 Mtpa coal-fired power CCS project, and several other companies have announced CCS projects [9]. CCS is considered a key cost-effective technology to facilitate the economic decarbonization of China’s industry [10,11]. Similarly, CTL and CCS technology (CTL-CCS) could be integrated to reduce CO2 emissions [12,13]. However, high investment costs remain one of the major barriers to the deployment of CTL-CCS, as is the case with its applications in power plants and other large industrial sources of CO2, particularly in the absence of carbon pricing mechanisms [14].

To achieve a cost-effective commitment of peaking CO2 emissions before 2030, China has decided to resort to market-based approaches. China’s national carbon emissions trading system (ETS) was launched in 2017 and online trading was officially launched on 16 July 2021, initially covering only the power sector (coal and gas power). In the first compliance period, 2162 key emission entities were covered by China’s national ETS, covering approximately 4.5 billion tons of CO2 emissions [15]. As a result, China’s national ETS has become the world’s largest carbon market. Recent policy signals indicate that the national ETS will soon expand to cover other industries. However, among the more than 10 sub-industries currently under consideration, the CTL sub-industry has not yet been mentioned. In the chemical industry, only methanol, synthetic ammonia, and calcium carbide have been considered and discussed [16]. Whether CTL will be covered by the national ETS in the future remains unclear.

Table 1 summarizes the carbon prices of the major carbon emission trading markets in domestic and foreign regions. These markets vary significantly in their design features, including cap setting, coverage, allowance allocation methods, offset mechanisms, etc. Some experts believe that China’s carbon price will rise to approximately 200 yuan per ton by 2030 [17].

Table 1.

Carbon prices in different ETSs.

The carbon cost could be imposed either based on carbon emissions (as in downstream mechanisms like ETS) or on carbon consumption (as in upstream carbon taxes) [21]. Compared with the downstream carbon price, the upstream carbon tax generally requires less effort in design and implementation. Some Chinese scholars argue that an upstream carbon tax should be implemented to simplify the design and implementation [22,23]. In addition to the ETS, the policy Opinions on the Complete, Accurate and Comprehensive Implementation of the New Development Concept to do a good job of Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutral Work was published in 2021, which mentioned that tax policies for carbon emissions reduction should be studied [24]. Since the 1990s, both carbon taxes and ETS have been increasingly implemented across various jurisdictions with a wide range of carbon prices. Table 2 provides a brief overview of selected carbon tax systems worldwide. Looking ahead, China is also likely to use both in parallel in the future. ETS would mainly regulate enterprises in covered sectors, while the carbon tax is used to promote carbon emissions reduction in other industries or fields. In addition, CCS projects in the US could obtain financial support from the US section 45Q Tax Credit policy. In 2018, projects could receive 50 USD/tCO2 for geologic storage and 35 USD/tCO2 for enhanced oil recovery [25].

Table 2.

Comparison between practical situations of carbon tax in major countries [26,27,28].

CTL, as a technology utilized in the upstream fuel production process, will inevitably be covered by either the ETS or a carbon tax. The upstream carbon tax is typically levied on specific fuels such as oil, gas, and coal, whose derivative products are based on their carbon content. It is a flat tax on all carbon entering the plant. In contrast, the downstream carbon price is usually applied according to the actual carbon emissions. Different regulatory approaches have different implications for the CTL technology. A key related issue is whether the carbon removed via CCS will be exempt from carbon taxation or not, which will create various incentives for the utilization of CCS technology [29,30].

CCS is a vital choice for CTL to address growing CO2 emission reduction pressure, while high investment costs remain a major barrier. The carbon price—whether upstream or downstream—is expected to serve as a primary policy instrument to encourage CCS implementation. Based on the above current price levels in domestic and foreign carbon markets and carbon taxes, the carbon price is assumed to fluctuate between 0 and 200 RMB/tCO2 before 2030. However, the regulation path of CTL in China remains under discussion. The carbon cost could be imposed either based on carbon emissions or carbon consumed. Therefore, it is essential to analyze both regulation options and assess how different carbon price levels may affect the cost-effectiveness of CTL production, both with or without CCS.

2. Process Simulation

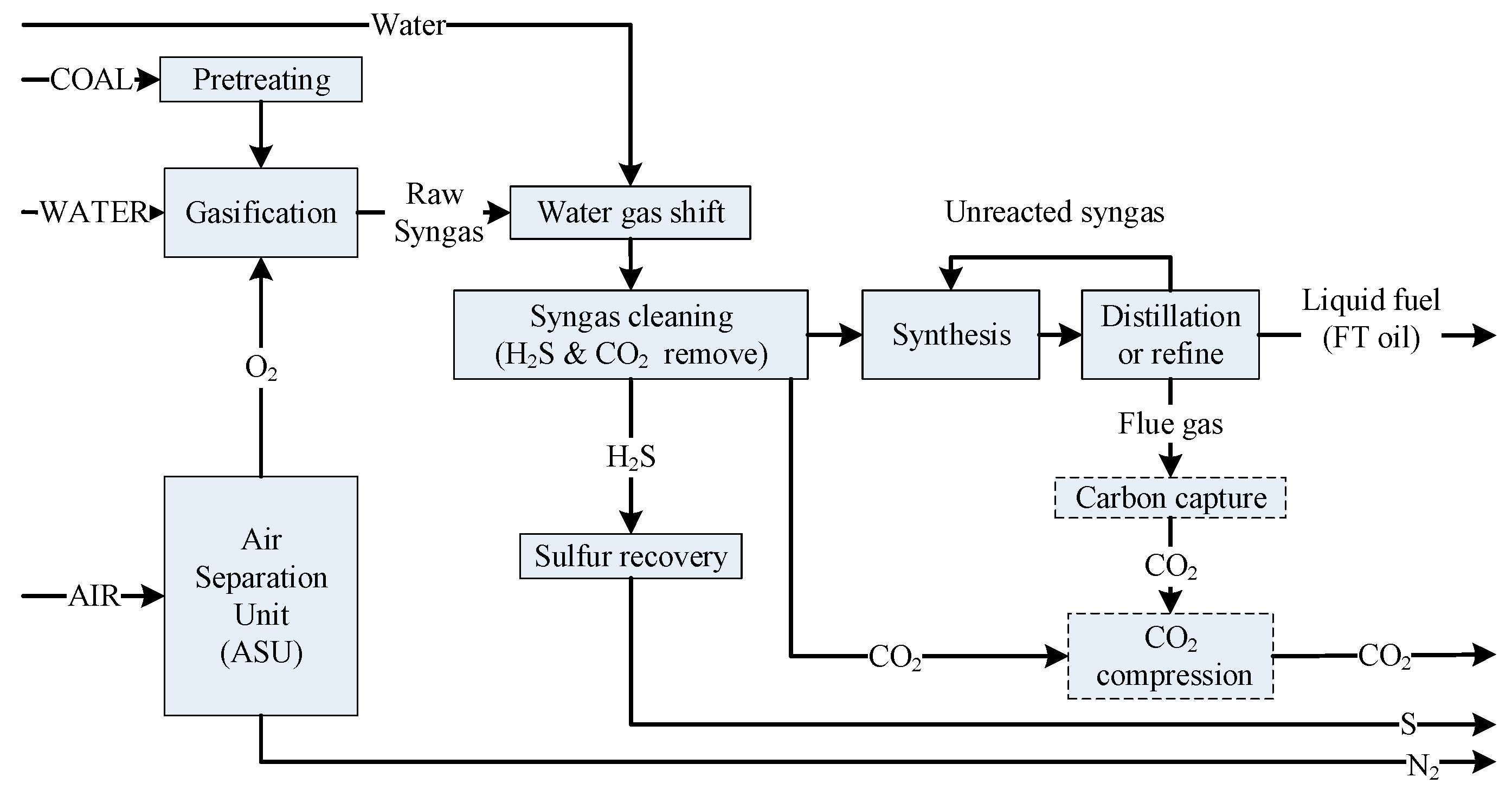

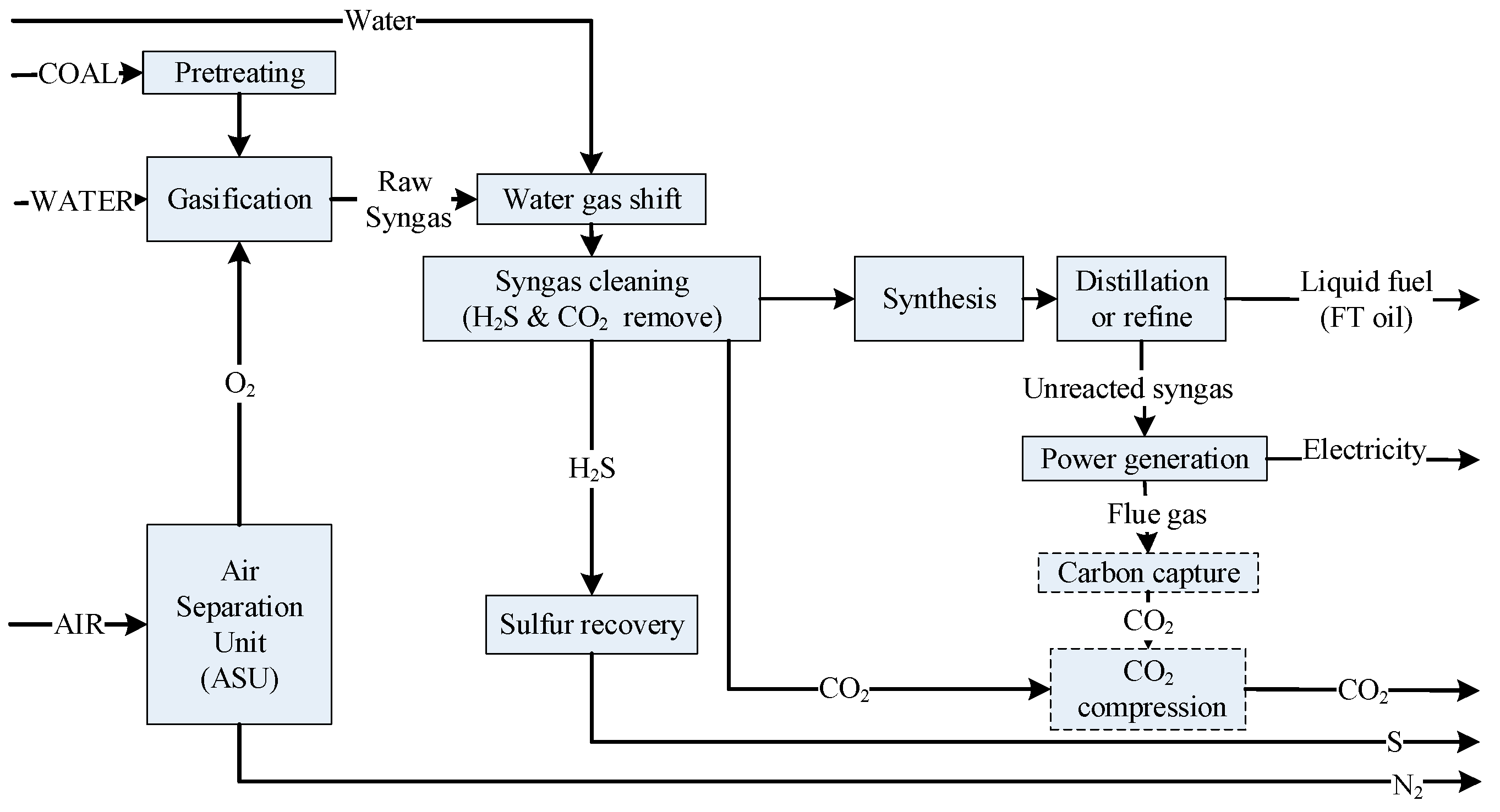

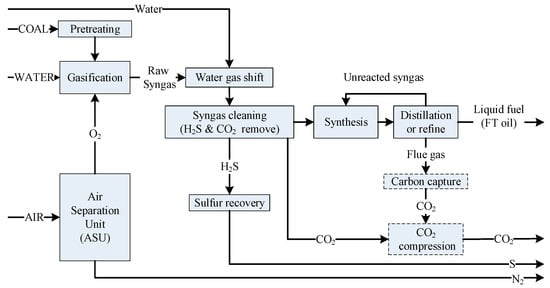

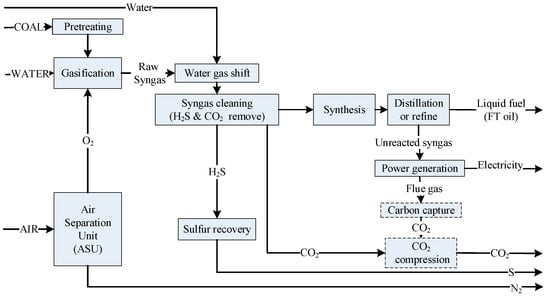

Until 2023, China had eight indirect liquefaction projects and one direct liquefaction project in operation. Four projects under construction were based on indirect liquefaction. Considering how indirect liquefaction technology is the dominant CTL technology in China, it was chosen to be simulated and analyzed. Figure 1 and Figure 2 present two configurations of indirect coal liquefaction using Fischer–Tropsch (FT) synthesis: one with recycling unreacted syngas (Figure 1) and the other with once-through synthesis combined with electricity generation from unreacted syngas (Figure 2). Each route can be integrated with or without CCS. Once-through synthesis with CCS is named FT-OT-CCS, while the one without CCS is named FT-OT. Similarly, the system that recycles unreacted syngas with CCS is named FT-RE-CCS, whereas that without CCS is named FT-RE.

Figure 1.

Indirect coal liquefaction with recycling unreacted syngas.

Figure 2.

Indirect coal liquefaction with once-through synthesis combined with electricity generation from unreacted syngas.

Table 3 shows the eight different scenarios in the analysis. They are categorized by the technical production route, which is either once-through synthesis or recycling unreacted syngas, with or without CCS, and further differentiated based on the carbon cost mechanism, which is represented by either the upstream carbon tax or the downstream carbon price.

Table 3.

Eight scenarios for analysis.

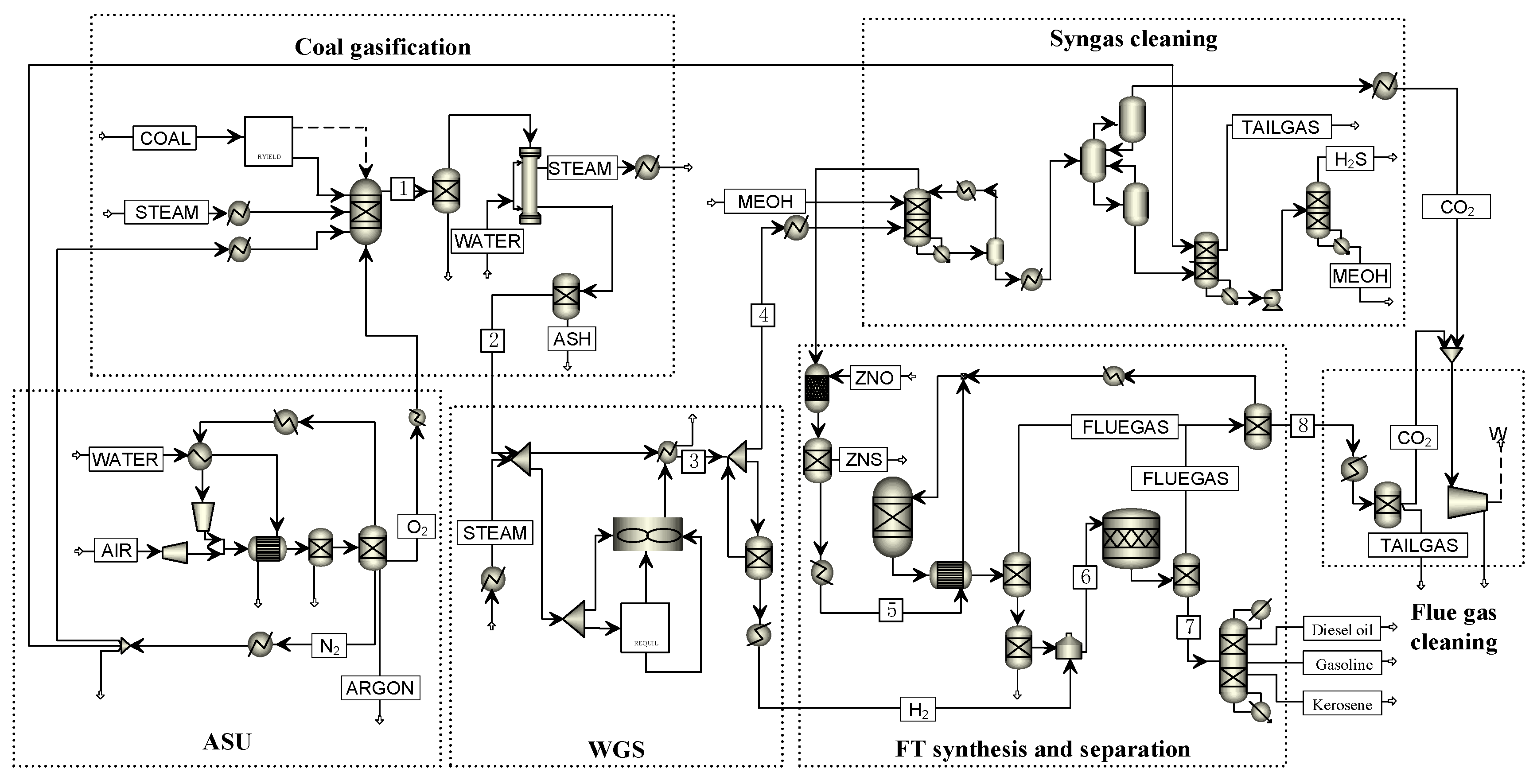

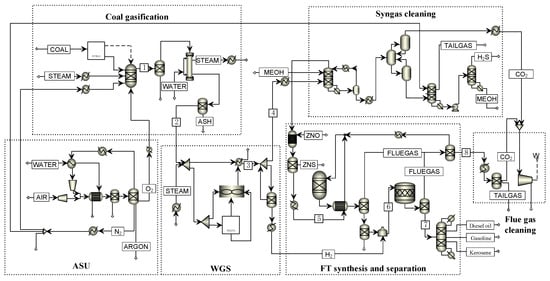

The technical route mentioned here has not yet been fully industrialized. Therefore, flow simulation is needed to obtain relative data and Aspen Plus 11.1 is adopted as a popular simulation software [31,32,33]. Figure 3 displays the simulation flowchart of the FT-RE-CCS production route. The main stream data in Figure 3 are listed in Supporting Information Table S1.

Figure 3.

Simulation flowchart for FT-RE-CCS, in which the numbers are the serial numbers of substreams.

The entire system could be subdivided into several key subsystems, including air separation unit (ASU), gasification, water gas shift (WGS), syngas cleaning, synthesis and distillation, flue gas cleaning, and power generation. Semi-mechanistic models, for each selected technology of the subsystems, were developed and are listed in Table 4 [34]. For model validation, the simulation data were compared with the literature data. The relative error for key parameters (e.g., temperature, pressure, flow, and gas composition) between the literature data and the simulation data must be less than 5%, and the overall average relative error for each unit must be below 10% [35,36].

Table 4.

Selected technologies of subsystems.

Anthracite coal or gas coal with a carbon content of 80–90% is primarily used in indirect CTL technology in China. One representative gas coal sample [42] from southwest China was selected as an example. The mass fractions of Ash, C, H, N, S, and O were 8.8%, 82.7%, 5.2%, 1.3%, 0.8%, and 5.4%, respectively. The mass fractions of water, fixed carbon, volatiles, and ash are 3.3%, 52.5%, 32.5%, and 8.8%, respectively. The main simulation results for a raw coal input of 1 kg/s are listed in Table 5 [34]. When producing the same annual oil product amount of 3 million tonnes, the product mass fraction distribution is 12% gasoline, 28% kerosene, and 60% diesel oil, respectively, while FT-OT-CCS and FT-OT pathways generate 670 and 652 kWh of electricity per year, and annual CO2 emissions from FT-OT-CCS, FT-OT, FT-RE-CCS, and FT-RE are 2.3, 12.6, 3.2, and 19.3 million tonnes, respectively.

Table 5.

Main simulation results.

3. Economic Analysis Model

The Electric Power Research Institute Technical Assessment Guide (EPRI TAG) cost estimation model [43] was used to calculate the total capital investment (CI). It was assumed that each technical route operates at a total capacity of 3 million tons of oil products per year, which means the output with a mix of gasoline, kerosene, and diesel was 3 million tons in total per year in each scenario. The basic calculation model, presented in Table 6, contains two parts: the total capital investment (CI) and the total operation and maintenance costs (OM) [44,45].

Table 6.

Basic assumptions of cost estimation model [34].

Total plant investment and OC are included in CI. The main parameters for calculating CI are main equipment investment and equipment contingency. Main equipment investment is calculated by adding estimated main equipment investment costs using the chemical engineering plant cost index (Equation (1)) [34]. Primary equipment investment costs for a production amount of 3 million tonnes of oil per year are calculated and shown in Supporting Information Table S2.

where IPE represents main equipment investment, I represents individual equipment investment costs, j represents the jth equipment, m represents the total amount of equipment, f represents the domestic factor, S represents the equipment production scale, b represents basic, and x represents the scale index. The scale index x and used for each piece of equipment are the same in the literature [34].

Equipment contingency is calculated by summing each equipment’s contingency. Each equipment’s contingency is calculated by multiplying each equipment’s investment cost and its contingency expense factor (Equation (2)) [34]. Contingency expense calculated is shown in Supporting Information Table S3 when the production amount is 3 million tonnes of oil per year.

where IEC is equipment contingency, FEC represents contingency expense factor for each piece of equipment.

Fixed expenses and variable expenses are included in OM. Table 7 shows the main assumption parameters for calculating fixed expenses in China.

Table 7.

Basic fixed expense assumption parameters [34,43].

The calculation of variable expenses, detailed in Table 6, is primarily based on the consumption of raw materials multiplied by their purchase prices, and the output of products multiplied by their respective selling prices in the Chinese market. Tax credits or carbon offsets were not considered in this study.

The estimated densities of diesel oil, gasoline, and kerosene oil are 0.86, 0.739, and 0.8 kg/dm3, respectively. Various agencies forecast that Brent oil prices could be in the range of USD 65 to USD 75 per barrel in 2025, and likely to continue to fall after 2025 [47,48]. Diesel oil, gasoline, and kerosene prices are estimated to be 7.1, 6.8, and 4.6 RMB/dm3 when the Brent crude oil price is about USD 65 per barrel. Then the price of oil is calculated as approximately 7500 RMB per tonne. As for carbon pricing, a range of 0–200 RMB/tCO2 is assumed. For the upstream carbon tax, the carbon pricing cost is calculated by multiplying the carbon price and the amount of CO2 converted from the carbon content of coal consumed. For the downstream carbon price, the carbon pricing cost is calculated by multiplying the carbon price and the amount of CO2 emission from syngas cleaning or flue gas. Reference carbon prices in several countries and major domestic and international emissions trading markets are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 8 shows the main parameters needed for calculating variable expenses.

Table 8.

Main variable expense parameters.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. The Product Cost

According to the economic estimation model, the product cost can be calculated using the equations

where C represents the product cost, CRF represents the capital recovery factor, a represents the discount rate, and n represents the plant lifetime, which is the total number of operation years. CI is the capital investment, P is the total output of system products, and is the total O&M costs per year.

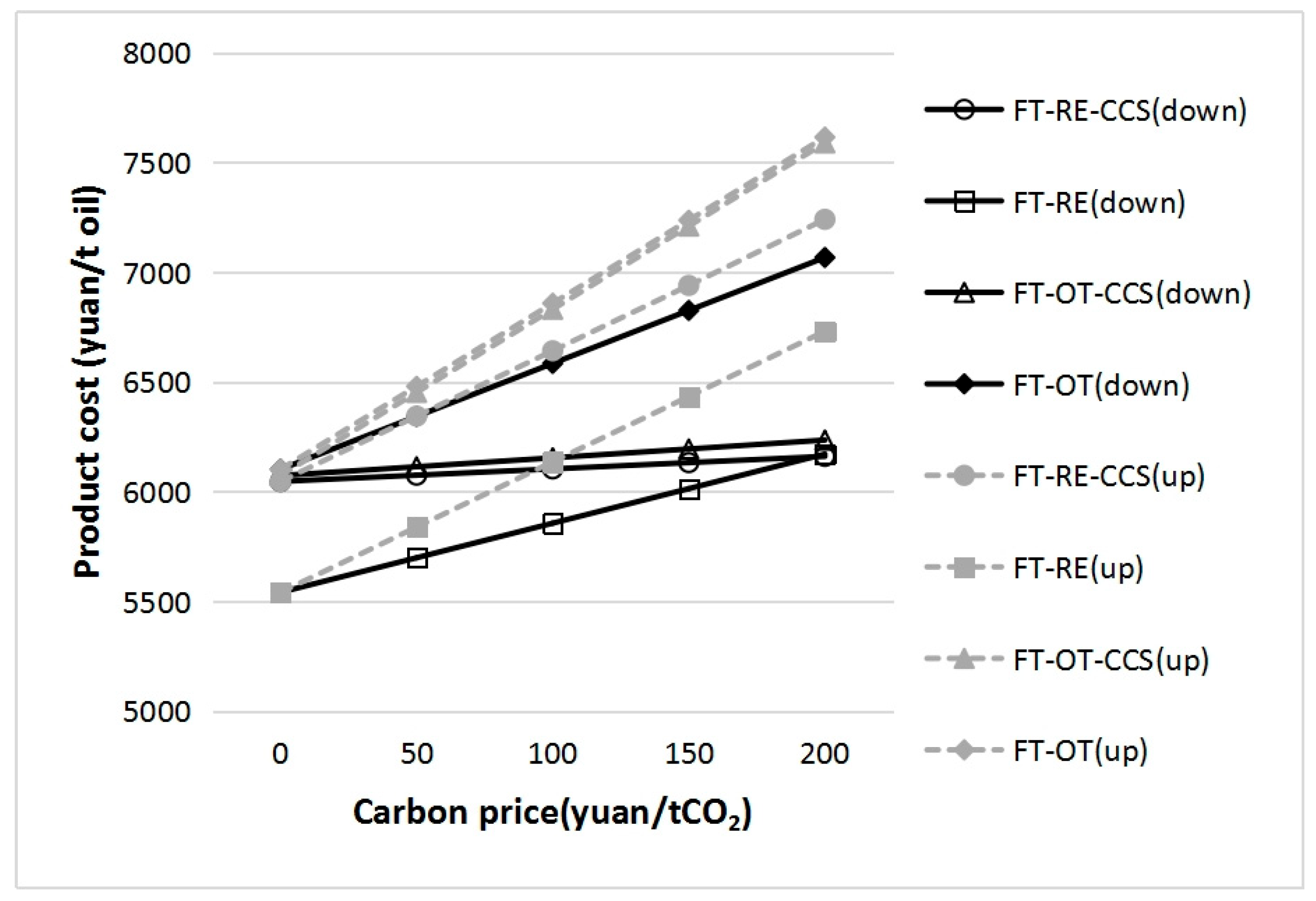

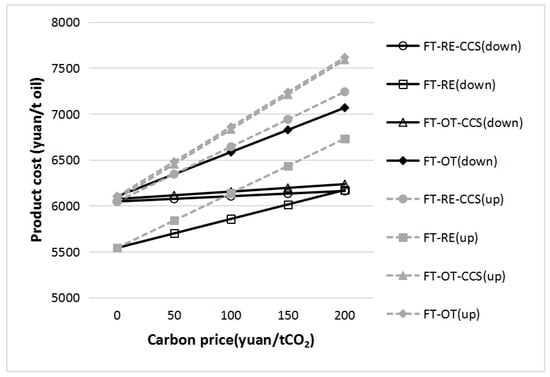

The effects of two levy methods, the upstream carbon tax or the downstream carbon price, and carbon prices on the oil cost under eight scenarios are listed in Figure 4. First, while an upstream carbon tax significantly increases product costs, it does not alter the relative cost differences between technologies. Consequently, it fails to incentivize enterprises to implement relative measures such as CCS technology to reduce emissions. In contrast, the downstream carbon price can reduce the additional product cost when adopting CCS. Especially for the FT-RE system, when the carbon price reaches 200 RMB/tCO2, adopting CCS technology can decrease the product cost. This indicates that the downstream carbon price is more conducive for reducing the emissions in production systems. Second, FT-RE consistently reveals a lower product cost than FT-OT, with or without CCS and under either carbon cost type, underscoring its superior economic performance. In addition, for systems with CCS, the downstream carbon price often has little impact on product cost due to their lower emissions. As the carbon price increases from 0 to 200 RMB/tCO2, the oil cost for the FT-RE-CCS and FT-OT-CCS systems increases by only about 2% and 3%, respectively, while the oil cost increases by about 11% and 16% for the FT-RE and FT-OT systems. In other words, regardless of the carbon cost implemented, the product cost will increase to some extent due to the current difficulty in rapidly deploying CCS in CTL systems. To limit the product cost increase to below 10%, the upstream carbon tax should not exceed 100 RMB/tCO2, while the downstream carbon price should remain below 120 RMB/tCO2. For a more stringent cap of a 5% cost increase, the upstream carbon tax should be kept under 40 RMB/tCO2, and the downstream carbon price under 60 RMB/tCO2.

Figure 4.

Effect of the carbon cost on the product cost. Down denotes downstream carbon price. Up denotes upstream carbon tax.

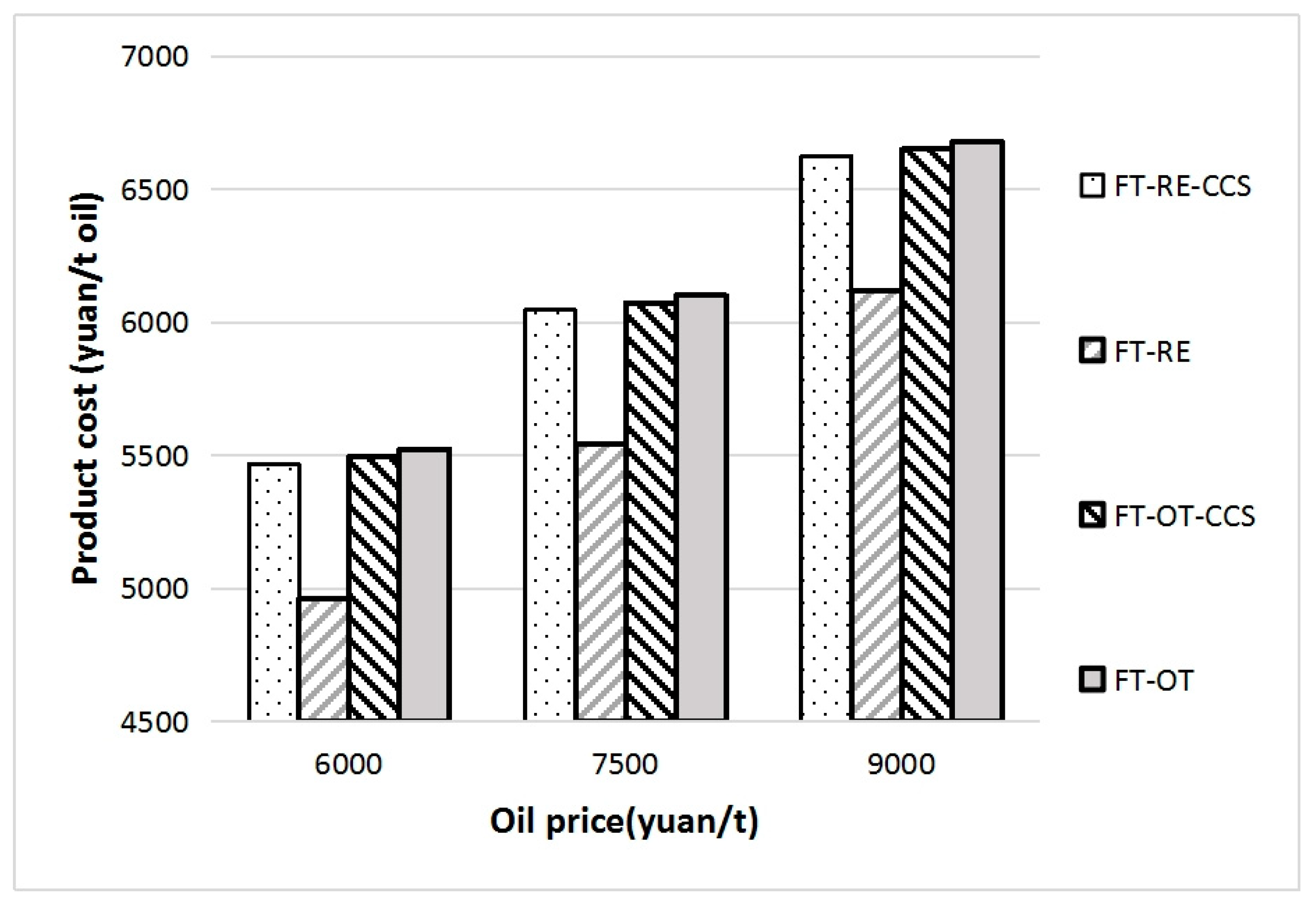

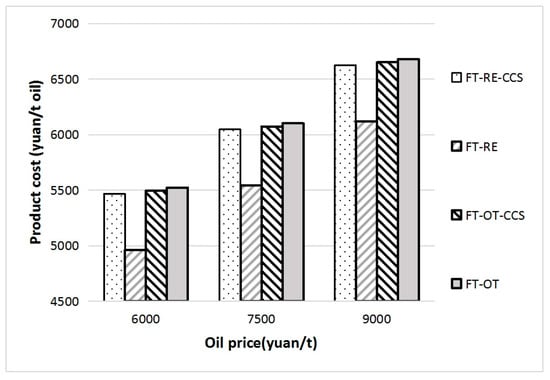

Given the volatility of global oil prices, a sensitivity analysis of product cost against varying oil prices is considered when there are no carbon prices, as shown in Figure 5. The higher the oil price, the higher the product cost. When the carbon price is higher, the relative product cost will increase with the same growth rate.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis of product cost against oil prices without carbon price.

4.2. IRR and NPV

The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) of a project means the discount rate when the total annual cash inflow accumulated during the entire economic life cycle (or within depreciation life) is equal to the total cash outflow. Therefore, during the calculation period, the discount rate of the Net Present Value (NPV) of the project is zero. The formulas are [54]

where NPV represents net present value, i represents the ith operation year, n represents the total number of operation years, a represents the discount rate, Vi represents the cash flow of a year, V0 represents the initial investment costs, and IRR is the internal rate of return.

IRR, which represents a project’s maximum profitability and the highest acceptable loan interest rate, should exceed the benchmark yield or bank lending rates. If the lending rate is higher than the IRR, then the project will incur a loss. Therefore, the IRR serves as a critical benchmark to determine the minimum requirements for accepting an investment program by analyzing the actual investment returns.

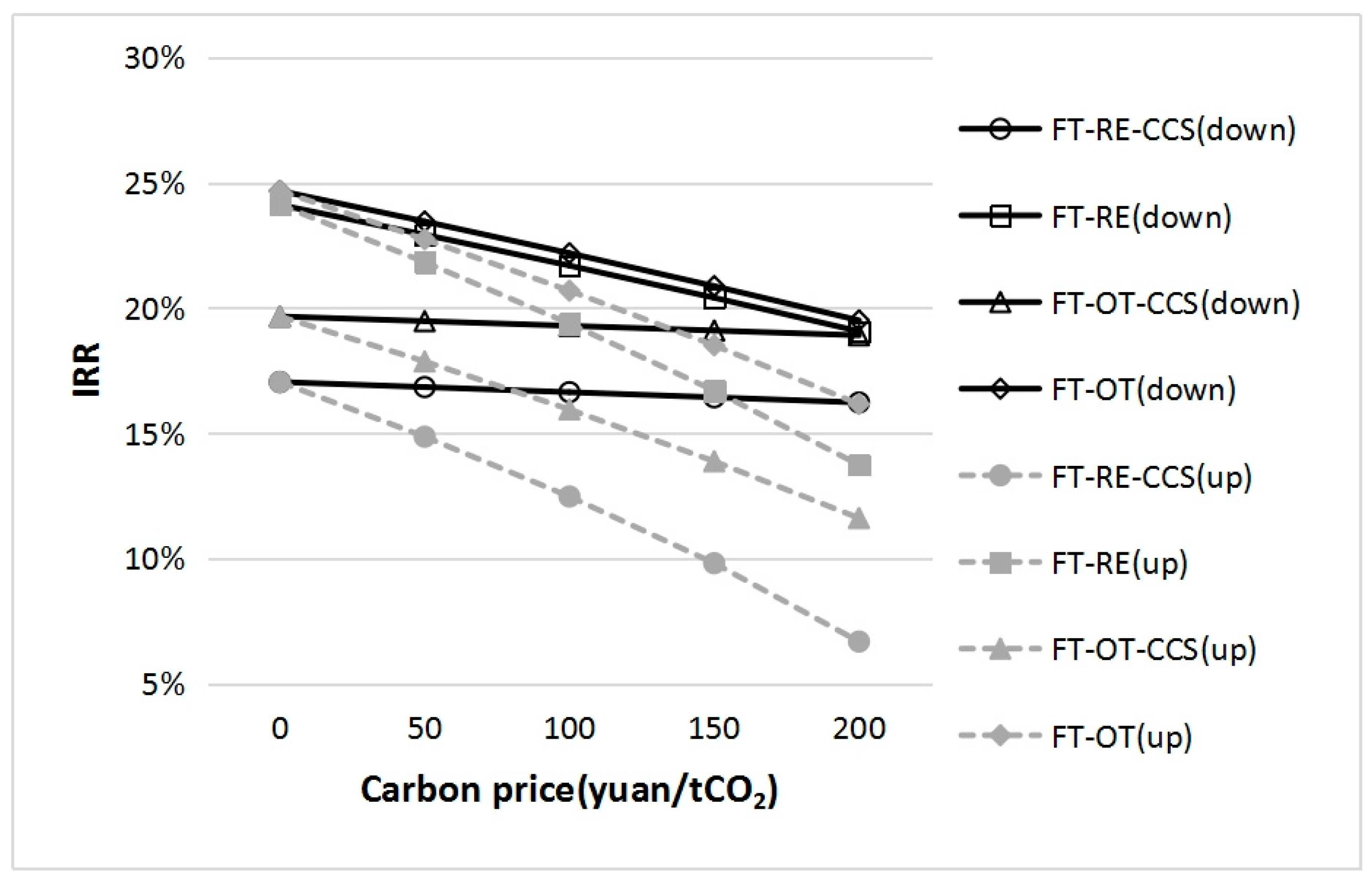

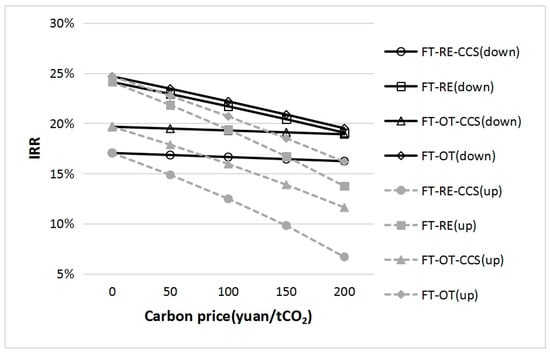

Figure 6 illustrates the impacts of different carbon pricing methods and price levels on the IRR across the eight scenarios. The upstream carbon tax shows a more substantial influence than the downstream carbon price, as evidenced by a significantly steeper decline in the IRR as carbon prices rise. Nevertheless, the influence of the downstream carbon price on systems with CCS remains relatively small, especially for FT-OT-CCS and FT-RE-CCS. Compared to those from FT-OT and FT-RE, the CO2 emissions from those two are significantly reduced from 13–19 Mt CO2 to only 2–3 Mt CO2 by coupling CCS. The influence of the downstream carbon price significantly declined at the same time. As the price increases, the difference in IRR caused by the adoption of CCS technology decreases. When the downstream carbon price increases from 0 to 200 RMB/tCO2, the IRR differences between FT-RE-CCS and FT-RE drops from 7% to 3%, and that between FT-OT-CCS and FT-OT drops from 5% to 1%, respectively. From the change trend in IRR, it could be found that if the downstream carbon price rises higher, to 300 RMB/tCO2 for example, the IRR of FT-OT-CCS will achieve the highest value, at nearly 19%.

Figure 6.

Effect of the carbon cost on IRR. Down denotes downstream carbon price. Up denotes upstream carbon tax.

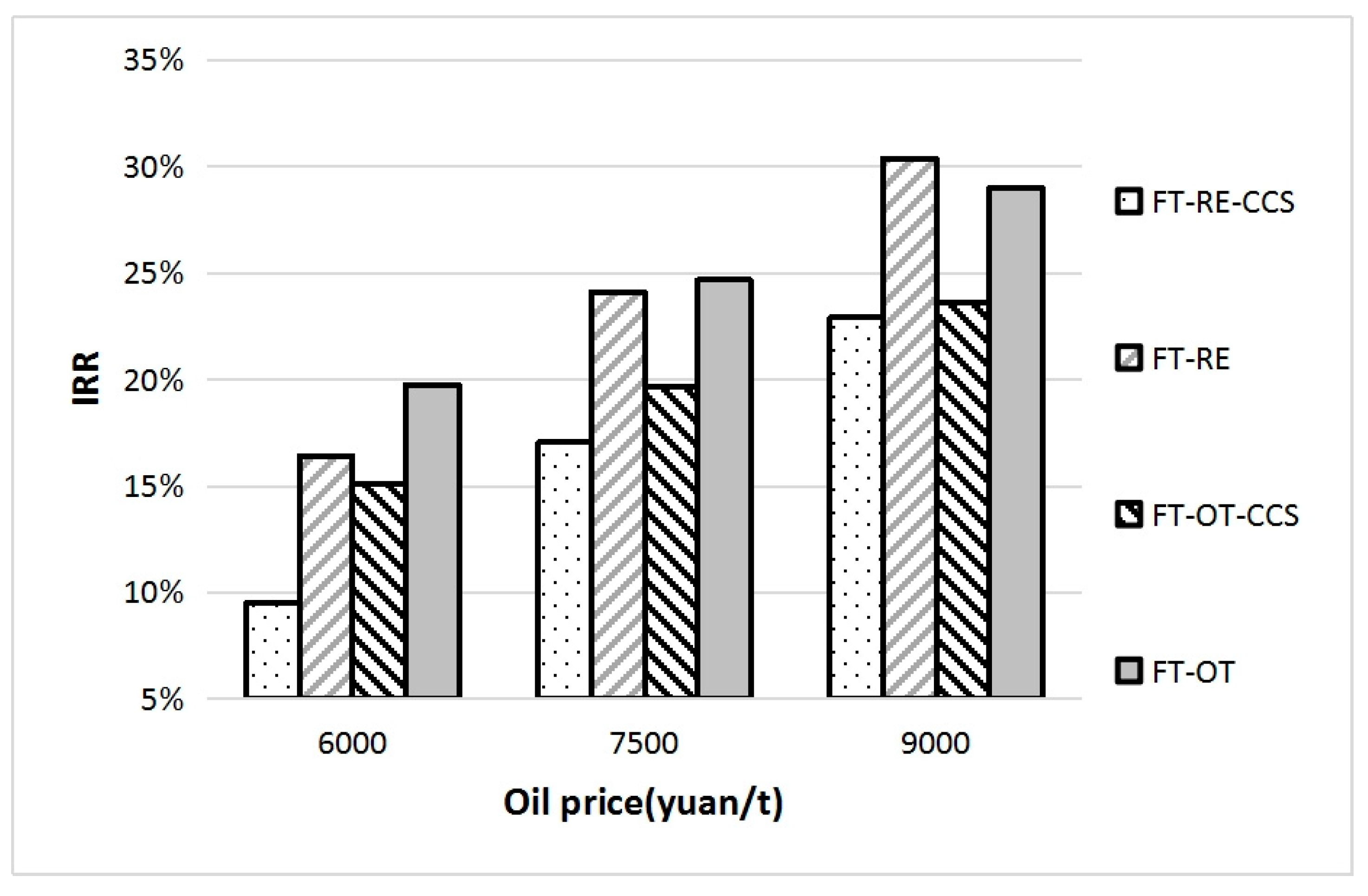

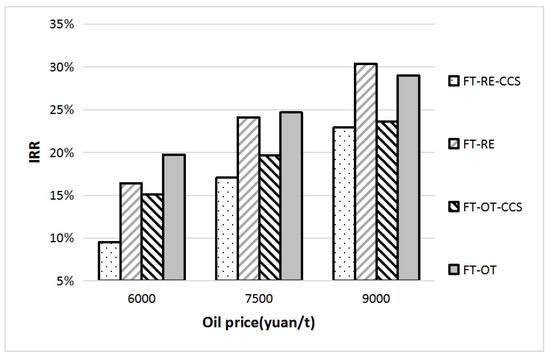

A sensitivity analysis of IRR against varying oil prices is considered when there are no carbon prices, as shown in Figure 7. The higher the oil price, the higher the IRR. When the carbon price is higher, the relative IRR will decrease with the same growth rate.

Figure 7.

Sensitivity analysis of IRR against oil prices without carbon price.

However, relying solely on IRR is insufficient for a comprehensive economic assessment of a technology. Both IRR and NPV are called discounted cash flow (DCF) methods because they both take into account the time value of money in evaluating capital investment projects. NPV is defined as the sum of the present value of the base year at the beginning of the calculation period, discounted by the annual net cash flow according to the industry benchmark discount rate or other prescribed discount rates during the project’s economic life (or depreciation period).

If its , a single project may be considered acceptable; if , the project should be rejected. The projects with are generally cost-effective. When comparing multiple projects, the larger the NPV, the better the project. This principle is also known as the Principle of Maximum Present Value.

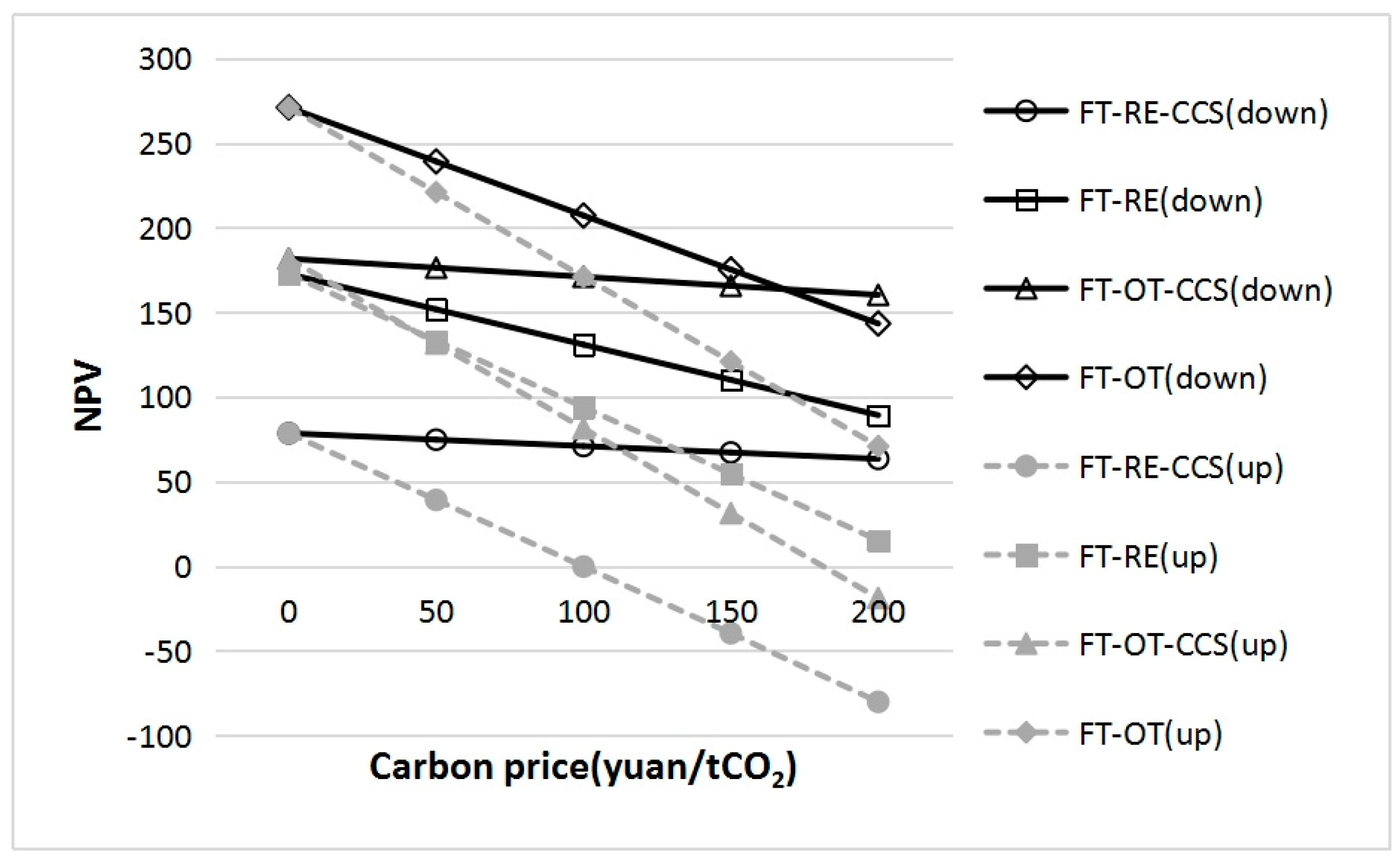

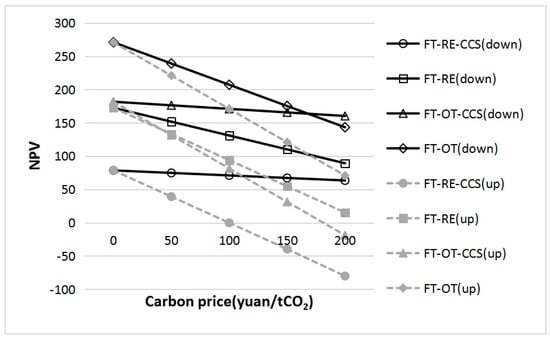

Figure 8 illustrates the impact of different carbon levy methods and price levels on the NPV. The upstream carbon tax has a greater effect than the downstream carbon price, reflected in a more rapid decline in NPV as carbon prices increase. In particular, the NPV of both FT-RE-CCS and FT-OT-CCS turns negative when the upstream carbon tax exceeds 100 and 180 RMB/tCO2, even though their IRR remains above 8%. In other words, when the upstream carbon tax is high enough, there will be no competitive economic advantage for the two technologies. In contrast, the impact of the downstream carbon price on a system with CCS is still relatively small. The output value of CCS is based on the carbon price. The smaller the gap between the cost of CCS technology application and the carbon cost, the smaller the impact of CCS application on NPV. Especially at a high carbon price, of 200 RMB/tCO2, adopting CCS technology has little influence on NPV for both FT-RE and FT-OT. Conversely, adopting CCS technology has more impact on NPV for both FT-RE and FT-OT at a lower carbon price. For example, when the downstream carbon price is 50 RMB/tCO2, adopting CCS technology can decrease NPV of FT-RE and FT-OT by 51% and 26%, respectively.

Figure 8.

Effect of the carbon cost on NPV. Down denotes downstream carbon price. Up denotes upstream carbon tax.

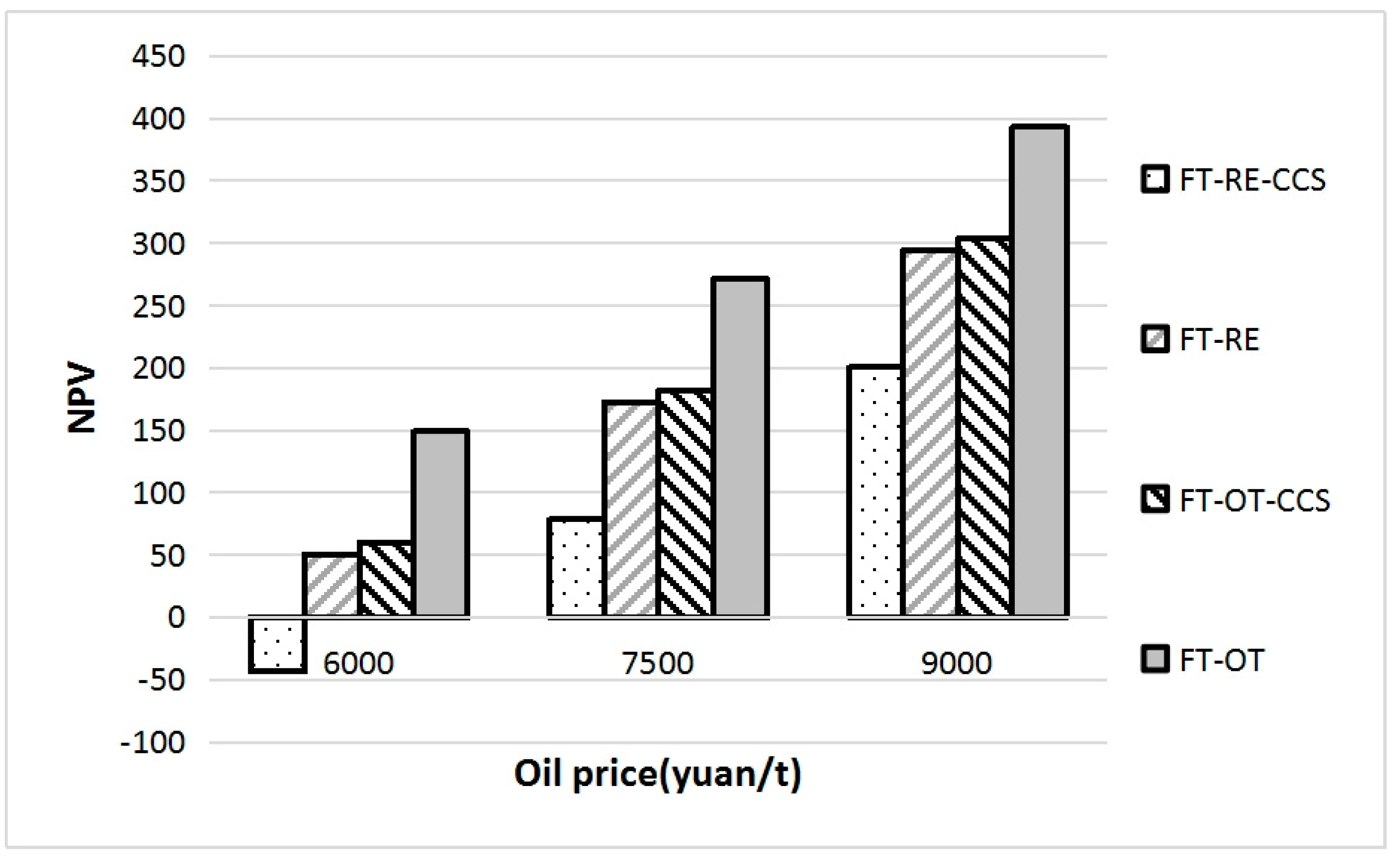

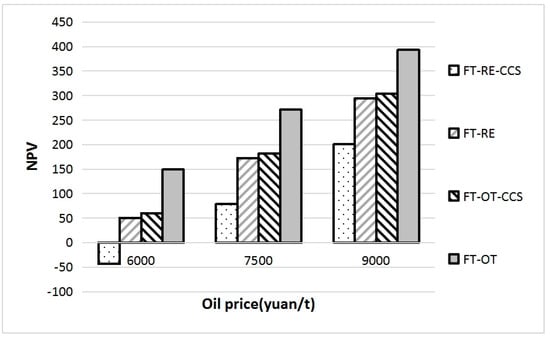

A sensitivity analysis of NPV against varying oil prices is considered when there are no carbon prices, as shown in Figure 9. The higher the oil price, the higher the NPV. When the carbon price is higher, the relative NPV will decrease with the same growth rate.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity analysis of NPV against oil prices without carbon price.

4.3. CO2 Emissions Abatement Cost

The cost of reducing CO2 emissions is defined as the additional cost incurred for capturing CO2 when implementing CCS, compared to a reference system without CCS, given the same amount of oil products. In this study, the system boundary for economic accounting and analysis is confined to the oil project production itself. Most of time, CO2 transportation and storage typically belong to downstream industries, that is, to other companies or projects. So, the calculated abatement cost includes only the capture cost and excludes expenses associated with CO2 transportation and storage. And the CO2 emissions abatement cost of the systems should be separated according to the product.

Thus, the abatement cost is calculated as

where RC is the CO2 emissions abatement cost of one FT synthesis (RMB/tCO2), CO2 is the amount of CO2 emissions from the production systems, P is the total output of system products, RE means recycling syngas, OT means once-through synthesis, and CCS represents CO2 capture technology.

When CO2 capture is adopted, the total CO2 emissions of FT-RE and FT-CO could be reduced from 12.6 and 19.3 million tons per year to 2.3 and 3.2 million tons per year, when producing 3 million tons of oil per year.

Table 9 shows the impact of two carbon levy methods and carbon price levels on emission abatement costs of FT-RE-CCS and FT-OT-CCS systems. The upstream carbon tax has a limited effect on the emission abatement cost. No matter how much CO2 is captured, the total upstream carbon tax is the same, as it is calculated by the carbon consumed. In contrast, as the price of the downstream carbon price increases, the cost of emissions reduction for both systems gradually decreases, making CCS more economically attractive. For the FT-OT-CCS system, the emission abatement cost is negative when there is no carbon cost. The core products of FT-CO or FT-CO-CCS are oil products and electricity, and all the system costs are calculated for the oil products. The introduction of CCS reduces electricity output, and subsequently causes a decrease in sales and profits. Due to the income tax being as high as 25%, the total income tax has been significantly reduced, and oil product cost is slightly lower than that of FT-CO. One main factor is the electricity selling price. If the electricity selling price is 0.3 RMB/kWh, which is lower than assumed, then the emission abatement cost will become positive. Another main factor is the income tax rate. If the income tax rate is 20% which is lower than assumed, then the emission abatement cost will also become positive. A higher carbon cost significantly lowers the abatement cost, indicating that CCS technology will bring in more revenue. For the FT-RE-CCS system, the abatement cost decreases by approximately 5% for every 10 RMB/tCO2 increase in the carbon price. When the carbon cost exceeds 196 RMB/tCO2, the emission abatement cost will turn negative. Therefore, these results demonstrate that the downstream carbon price can make great contributions to reduce the emission abatement cost, thereby creating a stronger economic incentive for enterprises to adopt CCS and other emission reduction technologies.

Table 9.

Effect of the carbon cost on the CO2 emission abatement cost.

5. Conclusions

Four possible technology configurations for CTL are simulated and two possible carbon pricing mechanisms are discussed. The CTL pathways include two indirect coal liquefaction options: once-through synthesis with electricity generation from unreacted syngas, and recycling unreacted syngas. Using Aspen Plus, four possible technology combinations, which are FT-RE, FT-RE-CCS, FT-OT, and FT-OT-CCS, were simulated to obtain detailed material flow data. The carbon cost could be implemented mainly in two forms according to the point of regulating emissions from the energy industries, i.e., the upstream carbon tax and the downstream carbon price. Based on a cost estimation model EPRI TAG and material flow data, the financial performance of these four systems is assessed considering carbon cost implemented in different forms.

The analysis leads to four main findings. First, adopting CCS without carbon pricing has a significant influence on economic performance of the four systems. It is clear that without the support of carbon pricing policies, enterprises lack the incentive to utilize CCS due to the economic losses even though the CCS can be scaled up. Second, the upstream carbon tax has a limited effect on the emission abatement cost, and fails to promote emissions reduction and encourage enterprises to utilize CCS. Third, the downstream carbon price could reduce the economic losses by adopting CCS, thus promoting emissions reduction in manufacturing systems under higher carbon price levels. The adoption of CCS technology will reduce the IRR by 3% and 1% and the NPV by 29% and 12%, respectively, for FT-RE and FT-OT. Forth, enterprises are willing to adopt CCS when the carbon price is sufficiently high. While the current price exceeds initial expectations, a stable and higher carbon price supported by long-term policy mechanisms needs to be stabilized in the future. Therefore, the introduction of CCS technology will gain benefits at such a high price. On the other hand, non-economic factors such as public image may be additional incentives for enterprises to introduce CCS technology under such conditions.

Although the downstream carbon price could help reduce the actual emissions reduction in CTL projects with CCS, it should be noted that the incentives provided by such policies will be very limited at low carbon price levels. Furthermore, the carbon cost will be more effective than the national carbon ETS in promoting the implementation of CCS technology in CTL systems due to the fact that free allowance allocation in ETS can mitigate the financial pressure on less efficient producers.

And it should also be noted that there are several uncertainties in the investment cost estimation. First, there will always be deviations between an actual project construction and the construction expectations. All the fixed expense assumption parameters in Table 7 and variable expense parameters in Table 8 will affect the results. Although such variations generally do not alter the relative comparison among various technical routes, they do influence the absolute values of the estimation results, sometimes by over 10%. As more accurate data become available, further study is needed to assess the possible impact of these uncertainties. Second, it should be noticed that only the carbon capture cost is considered in this study. The feasibility of CCS also depends on its transportation and storage costs. Pipeline transportation of CO2 will be the primary transportation mode for large-scale demonstration projects in the future, the cost of which is estimated to be 0.7 and 0.4 RMB/ton/km in 2030 and 2060, respectively. The CO2 storage cost will be 40–50 RMB/ton in 2030 and 20–25 RMB/ton in 2060 [55]. Therefore, a CTL project site selected near CCS sites will be economically beneficial; otherwise, it may reduce the project competitiveness with CCS.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr13123960/s1: Table S1. Simulated main stream data of FT-RE-CCS. Table S2. Primary equipment investment costs (Million yuan RMB). Table S3. Contingency expenses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and B.H.; methodology, L.Z.; software, L.Z.; formal analysis, L.Z.; investigation, B.H. and M.D.; resources, B.H.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Z. and B.H.; writing—review and editing, L.Z., B.H. and M.D.; visualization, L.Z. and B.H.; supervision, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received funding from The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72140004). The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing, or publication. Comments by the anonymous referees are greatly appreciated.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Bing Han was employed by the company CHN Energy Investment Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ASU | Air separation unit |

| BWR-LS | BWR Lee-Starling |

| CCS | Carbon capture and storage |

| CI | Total capital investment |

| CTL | Coal-to-liquid |

| DCF | Discounted cash flows |

| EPRI TAG | The Electric Power Research Institute Technical Assessment Guide |

| ETS | Carbon emissions trading system |

| FT | Fischer–Tropsch |

| HOE | Home office engineering |

| HRSG | Heat recovery steam generation |

| HTS | High temperature shift |

| IEA | The International Energy Agency |

| IRR | The Internal Rate of Return |

| NPV | The Net Present Value |

| OC | Owner costs |

| OM | Total operation and maintenance costs |

| OT | Once-through synthesis |

| PR-BM | Peng–Robinson with Boston–Mathias alpha function |

| PSRK | Predictive Redlich–Kwong–Soave |

| RE | Recycle unreacted syngas |

| SMDS | Shell middle distillate syntheses |

| UNIQUAC | The universal quasi-chemical |

| WGS | Water gas shift |

References

- National Bureau of Statistics. Energy Production in December 2023. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202401/t20240116_1946618.html (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- National Energy Administration of China. The Notice on Publishing the 13th Five-Year Plan for the Industrial Demonstration of Coal Deep Processing, 2017. Available online: http://zfxxgk.nea.gov.cn/auto83/201703/t20170303_2606.htm?keywords= (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- National Development and Reform Commission; Ministry of Industry and Information Technology; Ministry of Natural Resources; Ministry of Ecology and Environment; Ministry of Transport and National Energy Administration. Opinions of the National Development and Reform Commission and Other Departments on Strengthening Clean and Efficient Utilization of Coal, 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202410/content_6978315.htm (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Muhammad, A.H.; Shahid, H.; Amro, M.E. Strategic priorities and cost considerations for decarbonizing electricity generation using CCS and nuclear energy. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 2108–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; John, E.P.; Karen, R.P. The impact of future carbon prices on CCS investment for power generation in China. Energy Policy 2013, 54, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.Q.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Z.K.; Yan, X.; Qiu, B.; Xu, N. Integration of carbon emission reduction policies and technologies: Research progress on carbon capture, utilization and storage technologies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 343, 127153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Energy Technology Perspectives 2016; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.L.; Zhou, W.L.; Ding, Z.X.; Zhang, X. The substantial impacts of carbon capture and storage technology policies on climate change mitigation pathways in China. Glob. Environ. Change 2024, 86, 102847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GCCSI. Global Status of CCS 2022; Global CCS Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.L.; Li, Z.Z.; Li, K.; Zhang, X. Modelling plant-level abatement costs and effects of incentive policies for coal-fired power generation retrofitted with CCUS. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.L.; Duan, H.B.; Yuan, Y.N. Perspective for China’s carbon capture and storage under the Paris agreement climate pledges. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2022, 119, 103738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Fan, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, L.; Feng, L. Is it worth to invest?—An evaluation of CTL-CCS project in China based on real options. Energy 2019, 182, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.J.; Li, K.; Li, X.Q.; Hou, Y. Investment feasibilities of CCUS technology retrofitting China’s coal chemical enterprises with different CO2 geological sequestration and utilization approaches. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2023, 128, 103960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GCCSI. Economic Assessment of Carbon Capture and Storage Technologies; Global CCS Institute: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China, 2022. The Ministry of Ecology and Environment Held a Regular Press Conference for July. Available online: https://weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show?id=2309404793752773329037 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, X.L.; Tong, Q. Study on expanding the sectoral coverage of China’s national carbon market. Environ. Prot. 2024, 766, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, C. Achievements and Prospect of China’s National Carbon Market Construction. J. Beijing Inst. Technol (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 26, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Carbon Emissions Trading Network. K Line Trend Chart of China’s Seven Major Carbon Markets, 2017. Available online: http://www.tanpaifang.com/tanhangqing/ (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Carbon Market. National Carbon Market Daily Market, 2023. Available online: https://carbonmarket.cn/ets/cets/ (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- International Carbon Action Partnership. ICAP Allowance Price Explorer, 2024. Available online: https://icapcarbonaction.com/en/ets-prices (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Carbon Tax Guide: A Handbook for Policy Makers, 2017. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/26300 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Su, M.; Fu, Z.H.; Xu, W.; Wang, Z.G.; Li, X.; Liang, Q. The design and conception of China’s carbon tax policy under the new situation. Res. Local Financ. 2010, 1, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.X. Research on carbon tax legislative framework for addressing climate change. Law Sci. Mag. 2010, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhua News Agency. Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and The State Council on the Complete, Accurate and Comprehensive Implementation of the New Development Concept to Do a Good Job of Carbon Peak Carbon Neutrality, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-10/24/content_5644613.htm (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Lee, B. The US Section 45Q Tax Credit for Carbon Oxide Sequestration: An Update; Global CCS Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; He, J.K. The study and Enlightenment of the carbon tax policy of the Nordic countries. Int. Outlook 2008, 408, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.L.; Dong, Z.F.; Long, F. The Updated International Practice Progress of Carbon Tax Policy and References for China. Chin. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 4, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, N.; Yang, X.L. Practical Development and Experience of International Carbon Tax Policy. Financ. Econ. 2024, 571, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, O.; Amit, K. Techno-economic assessment of hydrogen production from underground coal gasification (UCG) in Western Canada with carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) for upgrading bitumen from oil sands. Appl. Energy 2013, 111, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Z.; Yu, P.W.; Xian, Y.J.; Fan, J.L. Investment benefit analysis of coal-to-hydrogen coupled CCS technology in China based on real option approach. Energy 2024, 294, 130293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijmensen, M.J.A. The Production of Fischer-Tropsch Liquids and Power Through Biomass Gasification; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Alie, C.F. CO2 Capture with MEA: Integrating the Absorption Process and Steam Cycle of an Existing Coal-Fired Power Plant. Master’s Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R.R.; Zhu, H.Y.; Wang, A.R.; Li, J.; Dong, H. A coal-based polygeneration system of synthetic natural gas, methanol and ethylene glycol: Process modeling and techno-economic evaluation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 320, 124122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, W.Y.; Zhang, X.L.; Qi, T.Y. Simulation and economic analysis of indirect coal-to-liquid technology coupling. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 9871–9878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Lee, S.J.; Yun, Y. Effect of air separation unit integration on integrated gasification combined cycle performance and NOx emission characteristics. Kor. J. Chem. Eng. 2007, 24, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaey, J.M. Exploring the power dimension. In Proceedings of the Custom Integrated Circuits Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 5–8 May 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shreiber, E. Air Separation Process Overview; Praxair Technology, Inc.: Danbury, CT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eurlings, J.T.G.M.; Ploeg, J.E.G. Process performance of the SCGP at Buggenum IGCC. In Proceedings of the Gasification Technologies Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–20 October 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.H.; Hu, S.; Chen, D.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L. System simulation of co-feed and co-generation system based on the syngas. Comput. Appl. Chem. 2006, 23, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Hu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Q. Study on co-feed and co-production system based on coal and natural gas for producing DME and electricity. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 136, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.H. Study on Co-feed and Co-Production Based on the Syngas. Master’s Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Hu, S.Y.; Li, Y.S.; Zhu, B.; Jin, Y. Study on systems based on coal and natural gas for producing DME. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 4101–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F. Technical and Economic Assessment for IGCC with CCS. Master’s Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, T.; Bravo, J.; Romero, C.E.; Lowe, T.; Driscoll, G.; Kreglow, B.; Schobert, H.; Yao, Z. Process design and techno-economic analysis of activated carbon derived from anthracite coal. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 355, 120525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostini, A.; Battini, F.; Padella, M.; Giuntoli, J.; Baxter, D.; Marelli, L.; Amaducci, S. Economics of GHG emissions mitigation via biogas production from Sorghum, maize and dairy farm manure digestion in the Po valley. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 89, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polaris Power Network News Center. The Nine Major Coal Chemical Projects in China Are All Big Projects, 2016. Available online: http://news.bjx.com.cn/html/20160108/699525.shtml (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Sina Finance. Bank of America: Crude Oil Prices May Come Under Pressure in 2025 Brent Crude Oil is Expected to Average $65/BBL, 2024. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1817491617421628998&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Hou, H. Downward Pressure on International Oil Prices Will Intensify. 2024. Available online: http://www.sinopecnews.com.cn/xnews/content/2024-12/06/content_7113185.html (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Price Center of Qinhuangdao Coal Net. Ring Bohai Power Coal Price Index (BSPI) Offshore Price of Qinhuangdao Port, 2017. Available online: http://www.cqcoal.com/exp/exponent.jsp (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Hua Law Network. How Much Is the Industrial Water, 2024. Available online: https://www.66law.cn/laws/519262.aspx (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Energy Storage Leader Alliance. The National Industrial and Commercial 10kv Agent Purchase Price Summary in August 2024. Available online: https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/711951700 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Polaris Power Network News Center. Coal Electricity Price of the Provinces in 2016. Available online: http://news.bjx.com.cn/html/20160912/771711-2.shtml (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Liao, K.C. Analysis of the Market Trend of Sulfur, 2023. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzA4MDIzNzQ4OA==&mid=2652545346&idx=1&sn=3818432fb7091806bec18b062811f003&chksm=8449479db33ece8b01f53db92e87c7ef3c42c3accb6f323694e21650e693cb9894e6786626ca&scene=27 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Zhou, C.Q.; Shi, H.Q.; Zheng, N. Techno-economic Analysis of Coal-fired Plant Integrated Carbon capture and Storage Considering Carbon Trading and Carbon Tax. J. Chin. Soc. Power Eng. 2023, 43, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qilu Petrochemical News. The Overall Scale of China’s CCUS Demonstration Projects is Relatively Small and the Cost is Relatively High, 2021. Available online: http://qlsh.sinopec.com/qlsh/media/fourth_edition/20211103/news_20211103_370417820921.shtml (accessed on 1 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).