Abstract

Microplastics (MPs) have emerged as persistent and ubiquitous contaminants in aquatic and terrestrial environments, yet existing reviews often focus narrowly on conventional removal methods and lack an integrated assessment of rapidly emerging technologies. This review addresses this critical gap by providing a comprehensive and comparative synthesis of both established and next-generation approaches for MP removal from water and wastewater systems. Conventional methods such as coagulation–flocculation, sedimentation, and filtration are compared with advanced approaches including membrane separation, adsorption using engineered biochar and nanomaterials, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), and biodegradation using microbial or enzymatic pathways. Particular emphasis is placed on hybrid and integrated systems, an area seldom summarized in prior reviews, highlighting their synergistic potential to enhance removal efficiency, reduce energy demand, and improve operational stability. Promising front-runner technologies including membrane filtration coupled with coagulation pretreatment and biochar-based magnetic adsorption systems have been identified based on a balanced performance across the key criteria of removal efficiency, scalability, energy demand, cost, byproduct risk, and environmental sustainability. The review concludes by outlining key research priorities such as standardized testing protocols, scalable biophysicochemical integration strategies, and sustainability-oriented life-cycle assessments to guide future innovation in MP management.

1. Introduction

Plastic production has soared over the past decades, exceeding 460 million tons in 2019 and projected to reach 1.1 billion tons by 2050 [1]. The inevitable fragmentation and degradation of plastic waste have generated vast quantities of microplastics (MPs, commonly defined as plastic particles sized 20–5000 µm) in aquatic environments [2]. These particles are now ubiquitous in freshwater systems, drinking-water supplies and wastewater streams.

Evidence shows that MPs are nearly impossible to avoid in water sources, where polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) dominate, with fibers and fragments being the most frequently detected forms [3]. For example, a global analysis of tap-water systems from 34 countries found that MPs were detected in 87% of 1148 samples, with concentrations spanning seven orders of magnitude (5th percentile: ~0.028 particles/L; median: ~4.5 particles/L; 95th percentile: ~728 particles/L) [4]. In a South African study of a major drinking-water supply, MPs ranged from 0.24 to 1.47 particles/L in source waters, and 0.56 to 0.90 particles/L after treatment, with little evidence of reduction across distribution [5]. In municipal wastewater influent in Poland, concentrations on the order of ~4.09 particles/L were reported [6]. These findings underscore the pervasive entry and persistence of MPs across water-resource systems.

Despite increasing awareness, effective removal of MPs presents multiple challenges. First, their heterogeneity in size (from micrometers to millimeters), shape (fragments, fibers, films, beads) and polymer type (PE, PP, PS, PET, PVC) leads to variable behaviors in water and treatment systems [4]. Second, many conventional water/wastewater treatment processes were not designed with MPs in mind, so capture efficiencies can be low or highly variable. Third, very small particles (especially <50 µm) dominate in many systems, yet are difficult to sample and remove consistently [4]. Fourth, the risk of secondary contamination (e.g., fragmentation into nanoplastics (typically defined as particles < 1 µm), release of additives or adsorbed pollutants) raises concerns about unintended consequences of an incomplete removal technology [7]. Altogether, these factors call for a systematic evaluation of possible treatment technologies.

Several reviews have summarized MP contamination and removal technologies, often with a broad scope covering occurrence, analysis, and fate [2,4,8]. Others have focused on specific categories, such as coagulation or adsorption [9,10,11,12]. However, many of these studies lack a structured, multi-criteria framework for direct cross-technology comparison, especially concerning scalability and sustainability for near-term deployment.

This review distinguishes itself by providing a systematic comparative evaluation focused specially on identifying “front-runner” technologies. It begins by examining the key characteristics of MPs that fundamentally govern their behavior and removal efficiency in treatment systems, as understanding these properties is prerequisite to evaluating any technology. The analysis then moves beyond reporting removal efficiencies to include a critical assessment of scalability, energy demand, cost, byproduct risk, and environmental sustainability. A novel feature of this work is the development of a comparative heat map (see Section 4) that visually synthesizes these performance criteria across all technologies. The discussion here highlights key research and technological gaps that must be addressed to enable scalable deployment of MP-removal solutions. The ultimate goal of this work is to offer a practical, decision-focused guide that helps researchers, industry practitioners, and policymakers prioritize the most promising technology pathways for scalable and sustainable MP removal.

2. Microplastic Characteristics Influencing Removal

2.1. Particle Size and Distribution

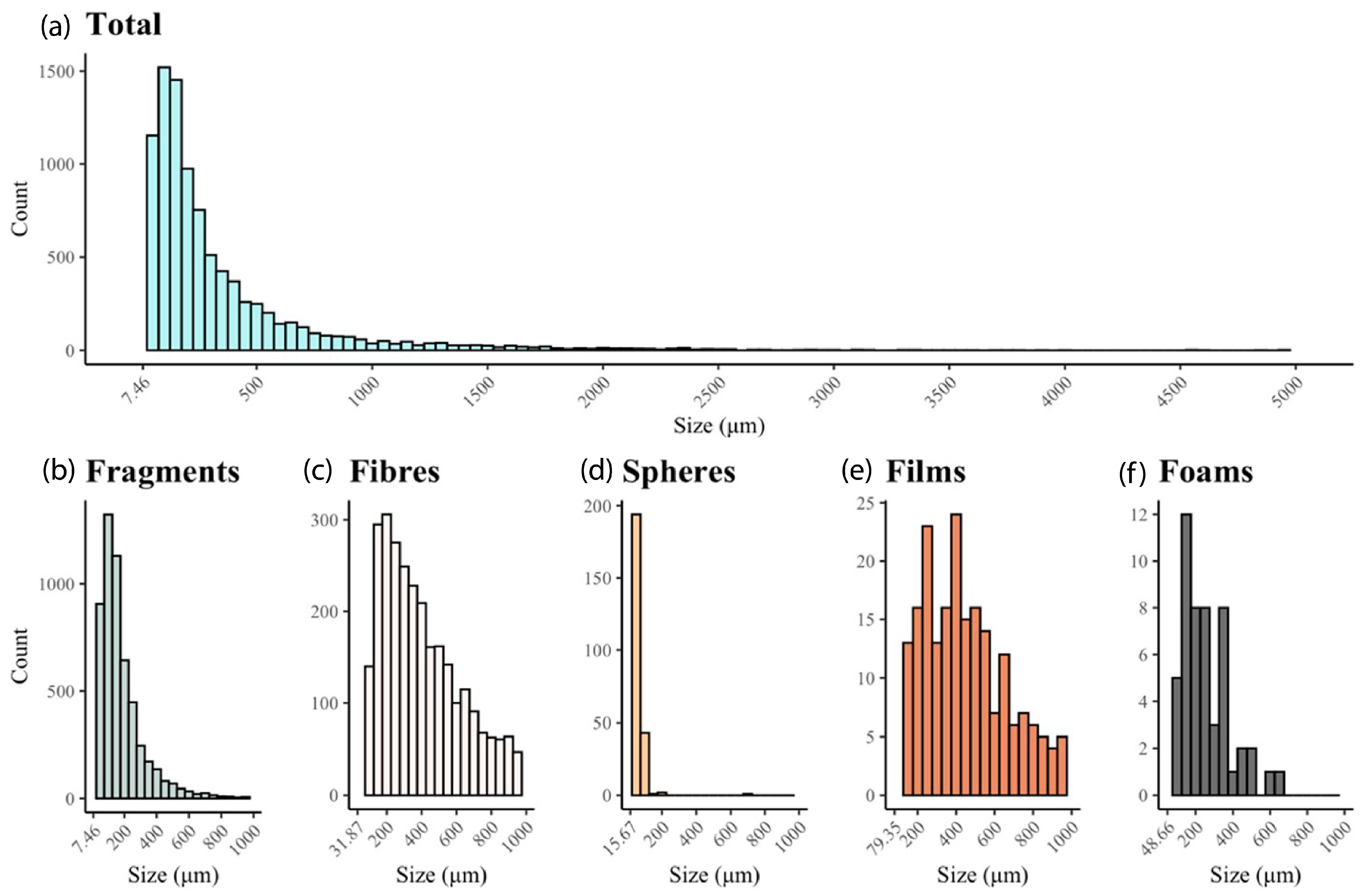

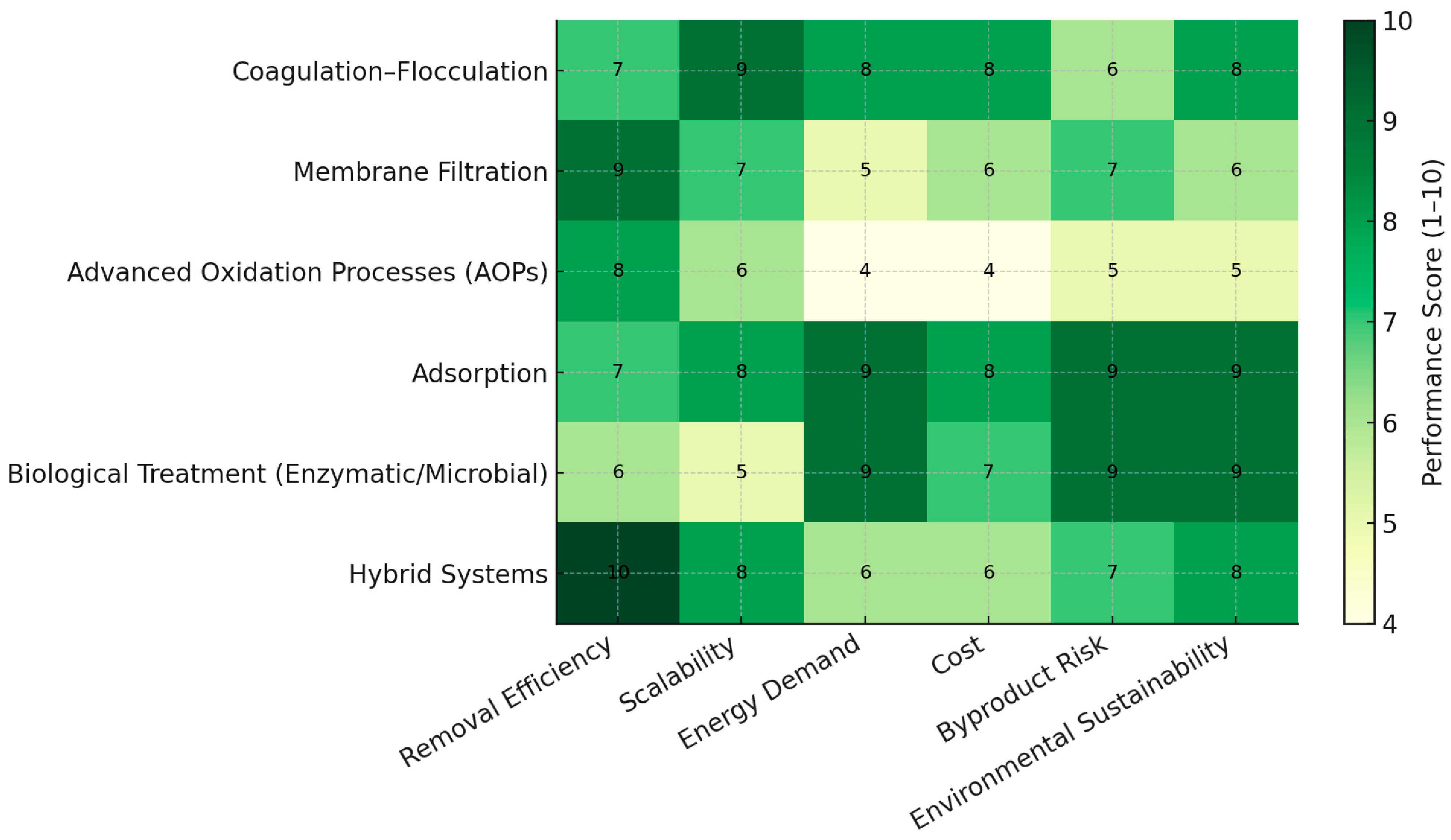

Particle size is the single most important predictor of how readily an MP is captured. Reported environmental size distributions range from millimeter-scale fragments and fibers down to micrometer and nanometer classes, with many studies now showing that a large fraction of particle counts occurs below 100 µm (Figure 1) [13]. Meanwhile, size distribution matters because it controls both collision efficiency and the stability of the nascent flocs: fine particles (<10–50 µm) present many more collision partners per unit mass and can be captured into flocs more readily when charge neutralization and bridging conditions are optimized, whereas large, low-density fragments and fibers resist aggregation and require different flocculation regimes or higher shear to incorporate into settleable flocs [14].

Figure 1.

Size distribution of (a) total microplastics (n = 9532), including (b) fragments (n = 5494), (c) fibers (n = 3502), (d) spheres (n = 247), (e) films (n = 236), and (f) foams (n = 53), identified in biosolid samples collected across Southern Ontario, Canada. Reprinted from Letwin et al. (2023) [13] with permission from the publisher.

In practice, the effectiveness of removal processes is predominantly determined by the size of MP particles. Mechanical and gravitational separation methods, such as screening and coarse settling, are primarily effective for capturing the largest MP particles, typically greater than 300–1000 µm. These processes rely on size exclusion and density differences, and therefore have limited impact on smaller particles that remain suspended in water [15].

Conventional sand filtration and rapid gravity filters extend the removal range to include sub-millimeter MPs. However, their performance decreases significantly for fine fractions smaller than 50 µm unless the system is enhanced through coagulation or followed by membrane polishing [9]. Reported removal efficiencies for sand filters vary widely among studies, ranging from approximately 74% to over 95% under optimized operating conditions, with higher efficiency typically observed for larger particle sizes [16]. This variability highlights the importance of particle size distribution, filter characteristics, and operational conditions in determining overall performance.

Membrane-based technologies, including microfiltration, ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, and reverse osmosis, offer more precise particle retention determined by the membrane’s pore size. Ultrafiltration and tighter membranes are particularly effective for small MP fractions, providing near-complete removal in some studies [17]. However, these advantages come at the cost of membrane fouling and higher energy demands, which limit large-scale implementation [18].

2.2. Particle Density

Polymer density (typical ranges: PE ≈ 0.91–0.97 g/cm3, PP ≈ 0.85–0.95 g/cm3, PET ≈ 1.33–1.45 g/cm3, PVC ≈ 1.3–1.6 g/cm3) strongly influences whether particles float, remain neutrally buoyant, or sink [15]. Low-density plastics (PE, PP) tend to remain near the surface and are less susceptible to processes relying on sedimentation, whereas higher-density polymers (PET, PVC) are amenable to settling or rapid sand filtration [17]. Quinn et al. (2017) validated several brine/density-separation approaches with spiked sediments and demonstrated that recovery rates (varying from ~40% to ~95%) depend strongly on the particle density, separation fluid density, and pre-treatment [19].

Nevertheless, because real environmental MPs are heterogeneous and often carry associated sediments or biofilms, effective removal cannot be inferred from MP density alone [20]. For example, experimental field and lab work by Amaral-Zettler et al. (2021) showed that biofouling increases the effective density of PP and PP particles and can turn buoyant plastics into sinking particles (i.e., surface area to volume ratios > 100), with measurable consequences for vertical transport and sediment accumulation [21].

Many current engineered removal tactics exploit buoyancy contrasts (e.g., surface skimming for buoyant MPs) or density increase (coagulation/flocculation followed by settling) rather than attempting to directly capture isolated buoyant particles without aggregation [10]. Considering the changes in the effective density of MP particles, single-density flotation protocols risk systematic under- or over-estimating certain polymer classes or size fractions. Therefore, future studies should (1) report or measure effective particle density where possible, (2) use pre-treatments (defouling/digestion) or multi-density separations, and (3) include spike-and-recovery controls to quantify method bias.

2.3. Particle Shape and Morphology

Particle shape and morphology exert a profound influence on how MPs interact with hydraulic flows, physical barriers, and treatment unit operations. Unlike near-spherical beads often used as laboratory surrogates, real environmental MPs include fibers, irregular fragments, thin films, and spheres, and these morphologies behave very differently in filtration, settling, and adsorption systems [15]. Among these, fibers and films are particularly challenging to remove due to their elongated or flexible structures.

Fibers tend to align with flow streamlines, allowing them to pass through filter pores smaller than their apparent length. Instead of being trapped by sieving, they may thread through pore throats or form transient bridges that detach under shear [22]. These irregular behaviors lead to variable removal efficiency compared to spheres, which typically form stable cake layers [23]. Similarly, thin films can deform and orient parallel to flow, slipping through filtration media or detaching after weak surface adhesion [23]. Moreover, hydrodynamic orientation further reduces capture efficiency. Due to their high aspect ratios, fibers and films often glide along streamlines rather than colliding with filter grains, resulting in lower interception probabilities [24]. This “hydrodynamic slip” increases their persistence in treated effluents.

Additionally, morphology also affects settling behavior. Because fibers and films have higher drag and lower effective densities than compact fragments, they settle much more slowly. Through a physical modeling study using 3D particle tracking of 24 nonbuoyant MP types (720 trajectories) in turbulent open-channel flow, Al-Zawaidah et al. (2024) showed that MPs exhibit transport modes similar to natural sediments (i.e., rolling, saltation, and suspension) governed by the transport stage (ratio of flow shear to settling velocity) [25]. Particle shape, particularly the low settling velocity of fibers, significantly affected transport behavior. Consequently, fibrous MPs can remain suspended under conditions where fragments have already settled, indicating that sedimentation-based processes are less effective unless aided by coagulants or flocculants that increase particle aggregation [25].

In membrane systems, fibrous MPs promote heterogeneous fouling. Their flexibility allows them to form web-like mats that cause uneven cake layers and localized bypass flow, lowering permeability and accelerating flux decline [26]. Although membranes can retain most fibers (>95%), the operational costs of cleaning fiber-laden feeds are considerably higher [27]. Field studies confirm that fibers dominate environmental MP samples, often accounting for 60–97% of total particles. While overall removal in conventional treatment exceeds 90%, fibers are consistently less efficiently removed than fragments or spheres (typically 81% versus 89% without coagulants). Coagulation improves both to ~96–97%, but shape-dependent challenges persist [28].

Given the dominance of fibrous MPs, monitoring and testing protocols must evolve to account for shape effects. Standard methods using spherical surrogates can overestimate removal efficiency. Advanced imaging and shape-sensitive analysis are essential for realistic assessment of treatment performance [29].

2.4. Surface Charge

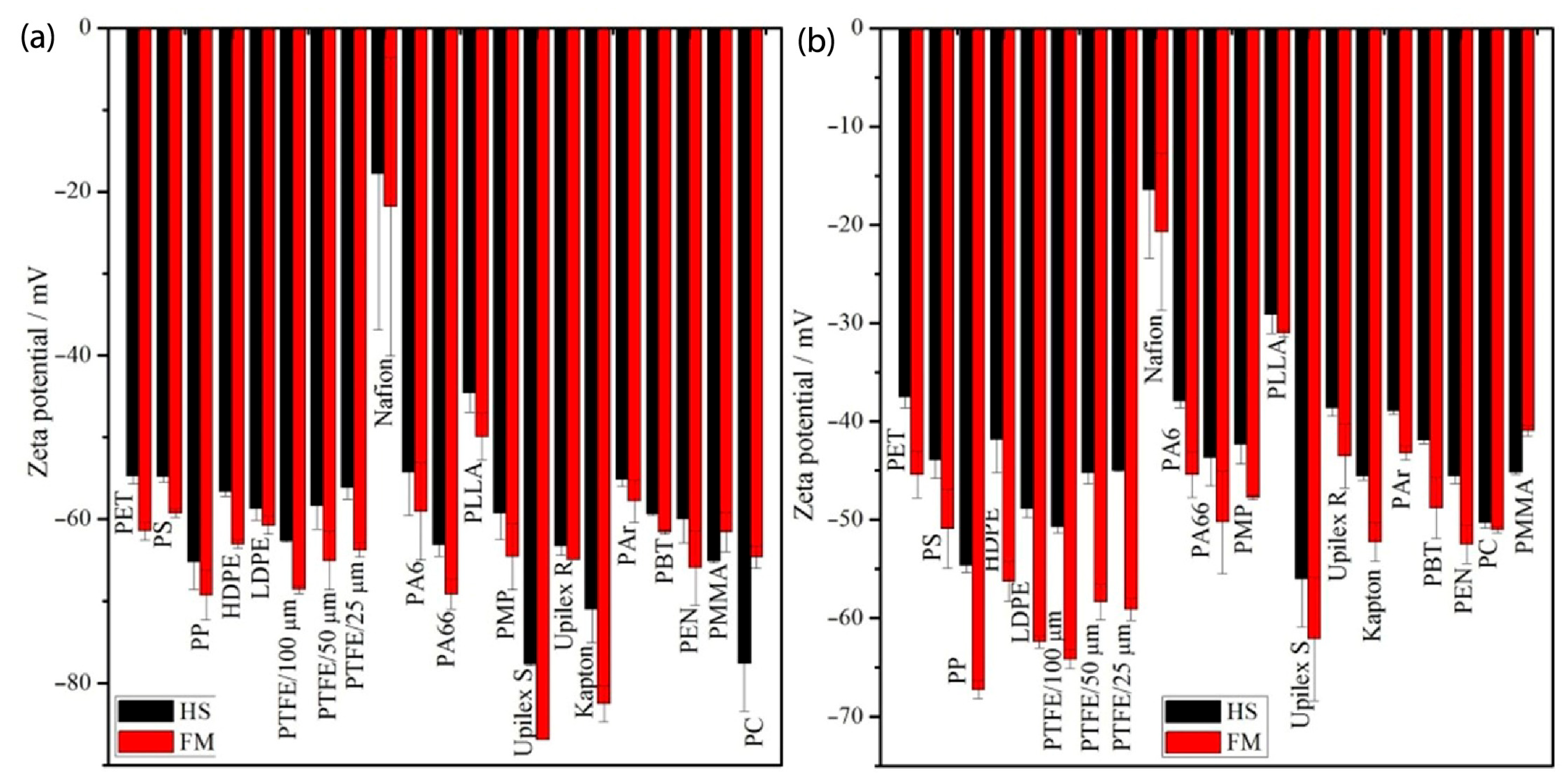

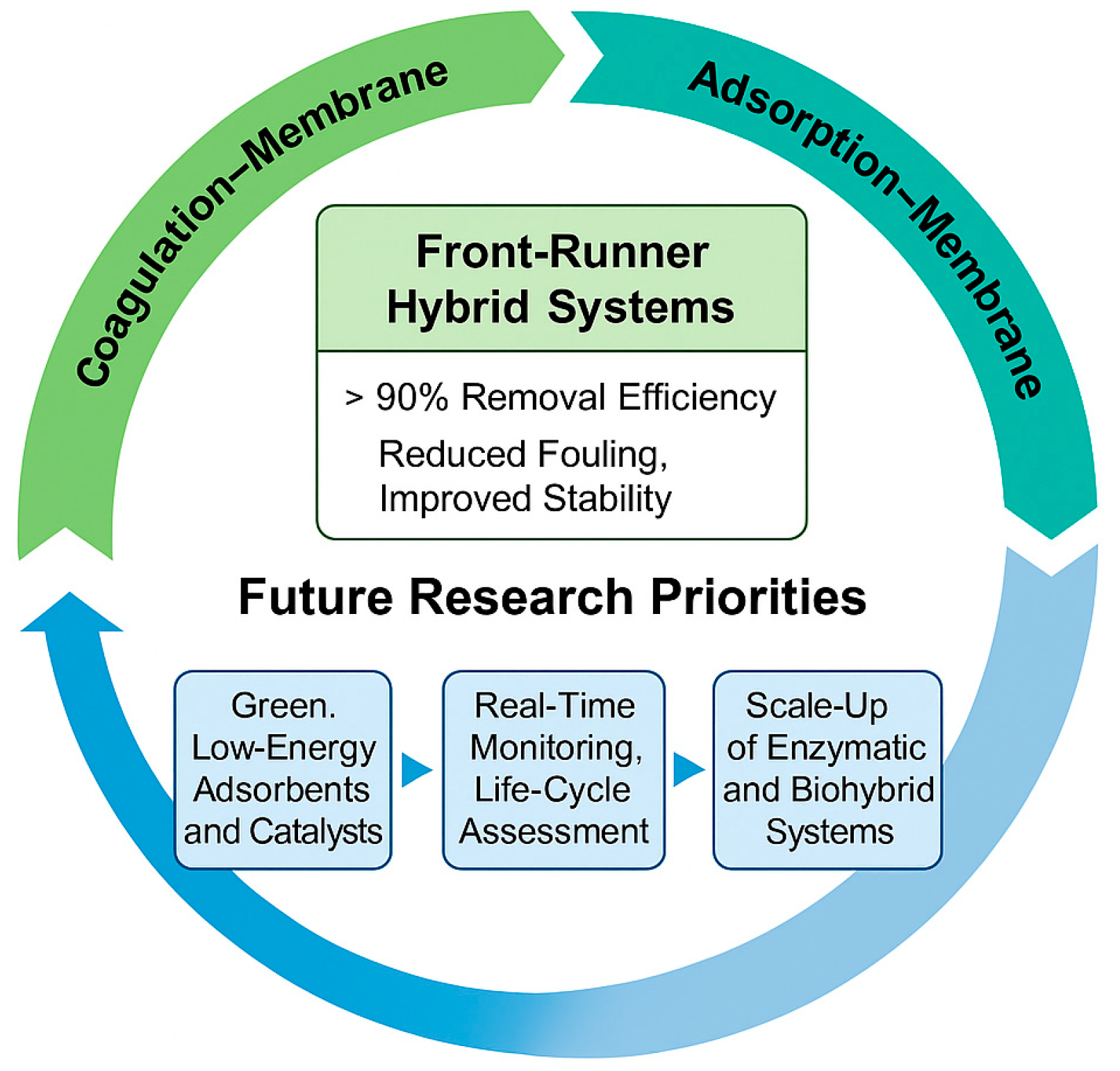

Most virgin plastic particles in aqueous environments exhibit a net negative surface charge (negative zeta potential), but this charge can be altered by adsorption of natural organic matter, oxidation, or surface functionalization [10]. Zeta-potential measurements for common MPs (e.g., PS microspheres) frequently report values in the negative tens of millivolts (Figure 2), and these electrostatic properties govern interactions with coagulants, flocculants, and charged adsorbents [30]. Notably, a recent study demonstrated that isoelectric point (IEP, ) can serve as a practical alternative to zeta potential () for assessing MP aggregation during coagulation [20]. Laboratory experiments and modeling showed strong correlations between IEP, attachment efficiency, and removal rates for PE and PVC, suggesting that using IEP could simplify field assessments of MP removal efficiency in water treatment [20].

Figure 2.

Zeta potential of (a) 21 polymer foils measured in 0.001 mol/L and (b) 0.005 mol/L KCl electrolyte, both calculated using the Helmholtz–Smoluchowski (HS, black) and Fairbrother–Mastin (FM, red) equations. Reprinted from Kolská et al. (2013) [31] with permission from the publisher.

Charge neutralization remains a principal mechanism in rapid coagulation–flocculation. Dosing with metal salts (Al/Fe) or polymeric coagulants reduces zeta potential toward zero, promoting aggregation of MPs into settleable flocs in many bench and pilot tests [32]. Removal efficiencies for specific lab or pilot systems often exceed 90% for target microbeads under controlled conditions [30].

2.5. Hydrophobicity

Hydrophobicity, arising from either polymer chemistry or surface aging, strongly influences the partitioning of MPs at air–water or oil–water interfaces and their capacity to sorb hydrophobic organic contaminants (HOCs). Hydrophobic polymers such as PE and PP exhibit a strong affinity for oil films and nonpolar contaminants, which can modify their environmental behavior and treatment outcomes [17]. For instance, studies have shown that aged MPs with oxidized surfaces can adsorb polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and other hydrophobic pollutants at higher rates due to increased surface roughness and oxygen-containing functional groups [8]. Such interactions can either facilitate or impede removal during treatment processes.

Hydrophobic particles may more readily attach to coagulant flocs under low-surfactant conditions, enhancing separation efficiency. Recent research found that weathering (via UV oxidation, mechanical abrasion, biofilm colonization, etc.) significantly enhances MP removal during coagulation and flocculation by increasing surface roughness and hydrophobicity [9]. Using Al-based coagulants and cationic polyacrylamide (PAM), removal efficiencies reached 97% for PEST fibers and 99% for weathered PE, while pristine large PE particles showed lower removal (82%) even under enhanced conditions, highlighting the key role of surface aging in improving treatment performance [9].

2.6. Biofilm Formation

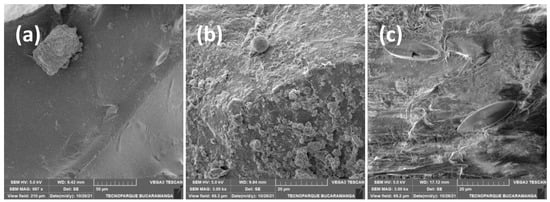

In environmental and engineered waters, MPs rapidly acquire conditioning films and biofilms (Figure 3). Biofilm colonization typically increases particle effective density and stickiness, promoting aggregation with other particulates and accelerating settling of originally buoyant fragments. Kooi et al. (2017) developed and validated a mechanistic model of how biofouling changes particle buoyancy and vertical dynamics [33]. At the same time, many laboratory and field studies have repeatedly shown that previously buoyant MPs (e.g., PE and PP fragments) can transition to net-sinking particles after biofilm development [17]. For instance, one recent study showed that biofilm growth can transform buoyant polypropylene MPs (~125–2000 μm) into sinking particles by increasing their density [21]. In freshwater simulations, 100% of small (125–212 μm) and intermediate, and 95% of large (1000–2000 μm) particles eventually sank, with corresponding increases in settling velocity and removability by sedimentation processes [34].

Moreover, biofilms can create specialized microenvironments capable of modifying and degrading plastic surfaces. Within these biofilms, microbial enzymes such as hydrolases, oxidases, and peroxidases first break large polymers into smaller subunits that microbes can metabolize [35]. The extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) matrix, composed of polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids, plays a key role in maintaining microbial structure, enhancing pollutant adsorption, and localizing enzymatic activity, all of which promote MP degradation [35].

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images illustrating biofilm formation on microplastic surfaces: (a) PE, (b) PS, and (c) PP. Reprinted from Porras-Rojas et al. (2023) [36] with permission from the publisher.

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images illustrating biofilm formation on microplastic surfaces: (a) PE, (b) PS, and (c) PP. Reprinted from Porras-Rojas et al. (2023) [36] with permission from the publisher.

Notably, biofilms on MPs may significantly influence the transport and fate of HOCs by both adsorbing and metabolizing them. These biofilm-coated plastics can accumulate persistent contaminants up to 106 times higher than surrounding seawater, with sorption driven by polymer–water partitioning behavior [37]. The EPS in biofilms act as both an additional sorptive phase and a diffusion barrier, slowing contaminant exchange by up to four orders of magnitude [37]. Therefore, while biofilms may reduce contaminant mobility, they also enhance microbial degradation of HOCs, highlighting a dual role in both pollutant accumulation and removal. These interactions complicate the risk assessment of MPs as vectors for chemical transport in aquatic environments.

2.7. Particle Load (Concentration)

High particle concentration strongly influences aggregation kinetics during coagulation–flocculation and directly affect downstream filtration behavior. At higher MP concentrations, the collision frequency between particles (and between particles and flocs) increases, accelerating aggregate growth and shifting the optimal coagulant dose [32]. Several experimental studies report that removal efficiencies and required coagulant doses change nonlinearly with MP load [10].

Similarly, empirical studies of drinking WTPs reveal large variability in overall microplastic removal efficiency. Combined coagulation–sedimentation processes have achieved removals ranging from approximately 40–55% for fiber-dominated samples to over 95% under optimized conditions for mixed microbead suspensions [38], highlighting how particle concentration, size distribution, and polymer composition collectively govern treatment performance.

In practice, elevated MP loads and particular size distributions accelerate filter head loss and clogging (increasing backwash frequency and operational cost) and can amplify membrane fouling when UF/MF polishing is used. Reviews and pilot studies note the practical need to (1) characterize both mass concentration and detailed size spectra upstream, (2) run spike-and-recovery tests during jar-testing to identify optimal coagulant/flocculant doses for the site-specific MP load, and (3) consider pre-treatment (pre-sedimentation, ballasted flocculation, or graded screens) to reduce particulate loads before fine filtration or membrane stages.

2.8. Polymer Type

Polymer type, or the chemical identity of the plastic, plays an important role in determining the fate and removal efficiency of microplastics in water and wastewater treatment systems. Different polymers possess distinct physicochemical properties, such as density, hydrophobicity, crystallinity, and surface energy, that govern how they interact with water, suspended solids, and treatment chemicals [2]. These intrinsic differences affect key processes including aggregation, settling, flotation, and sorption, ultimately influencing whether a particle is retained or escapes through treatment barriers [17].

For example, low-density polymers such as PE and PP tend to remain buoyant in water, reducing their likelihood of being removed by gravity-driven settling. In contrast, higher-density polymers such as PET and PS are more prone to sedimentation and aggregation with flocs [19]. This density contrast alone can create distinct separation behaviors under identical treatment conditions [32].

Beyond density, the surface chemistry of the polymer strongly affects hydrophobic interactions and sorption of coagulants or natural organic matter. Hydrophobic polymers such as PE and PP exhibit weaker electrostatic attraction to hydrophilic coagulants like aluminum or ferric salts, reducing floc attachment efficiency. Conversely, more polar polymers such as PET and PS often carry oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., ester, carbonyl, or hydroxyl groups) that enhance hydrogen bonding or van der Waals interactions with metal hydroxide flocs and dissolved organic matter. This difference in surface energy modulates not only coagulation and filtration efficiency but also the extent to which HOCs adsorb to the plastic surface, influencing their transport and risk potential in aquatic systems.

The characteristics discussed in this section (i.e., size, density, shape, surface chemistry, and biofilm formation) are critical determinants that directly influence the performance, optimization, and selection of the removal technologies evaluated in the subsequent sections.

3. Emerging and Advanced Technologies

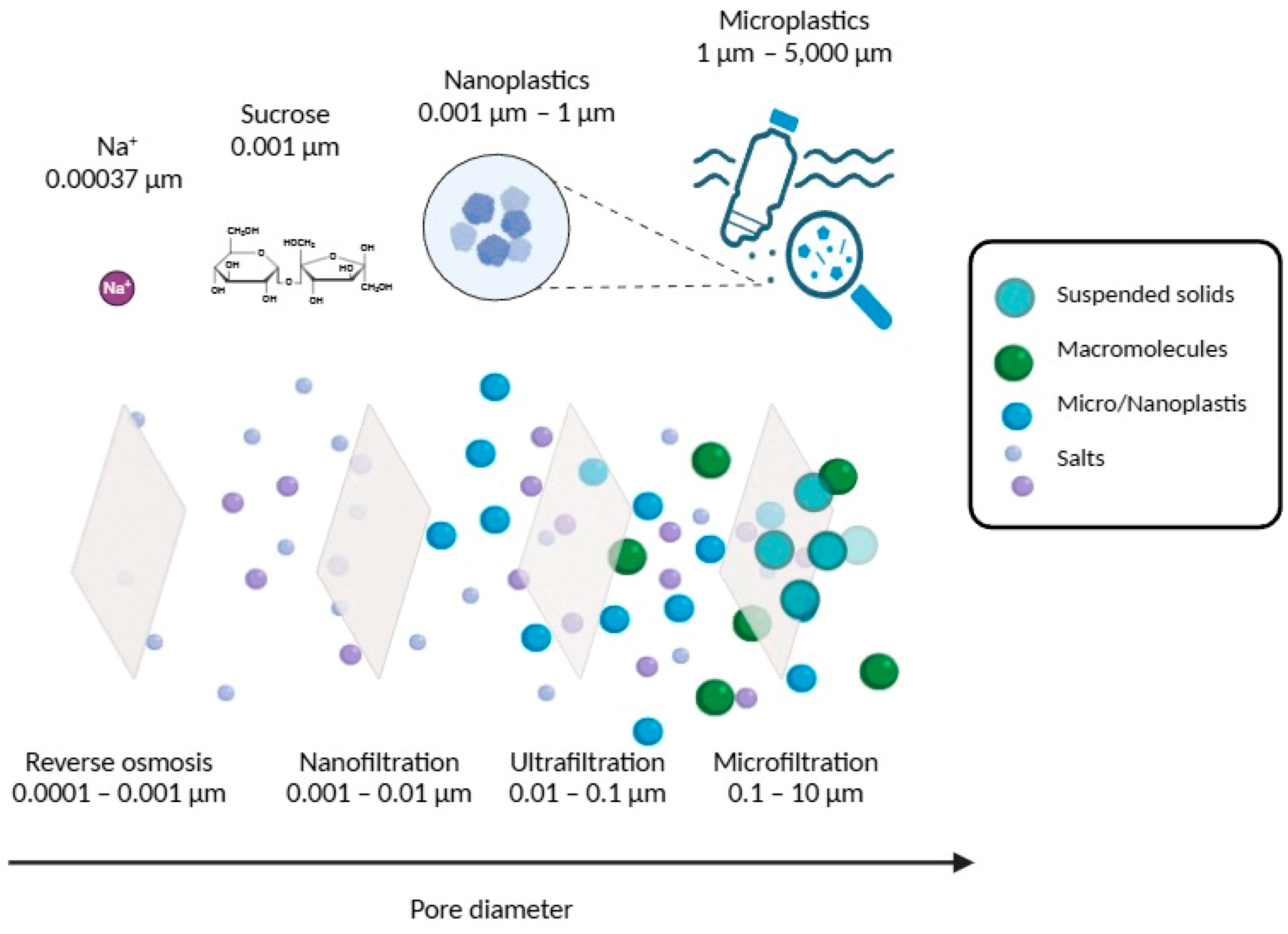

3.1. Membrane-Based Processes

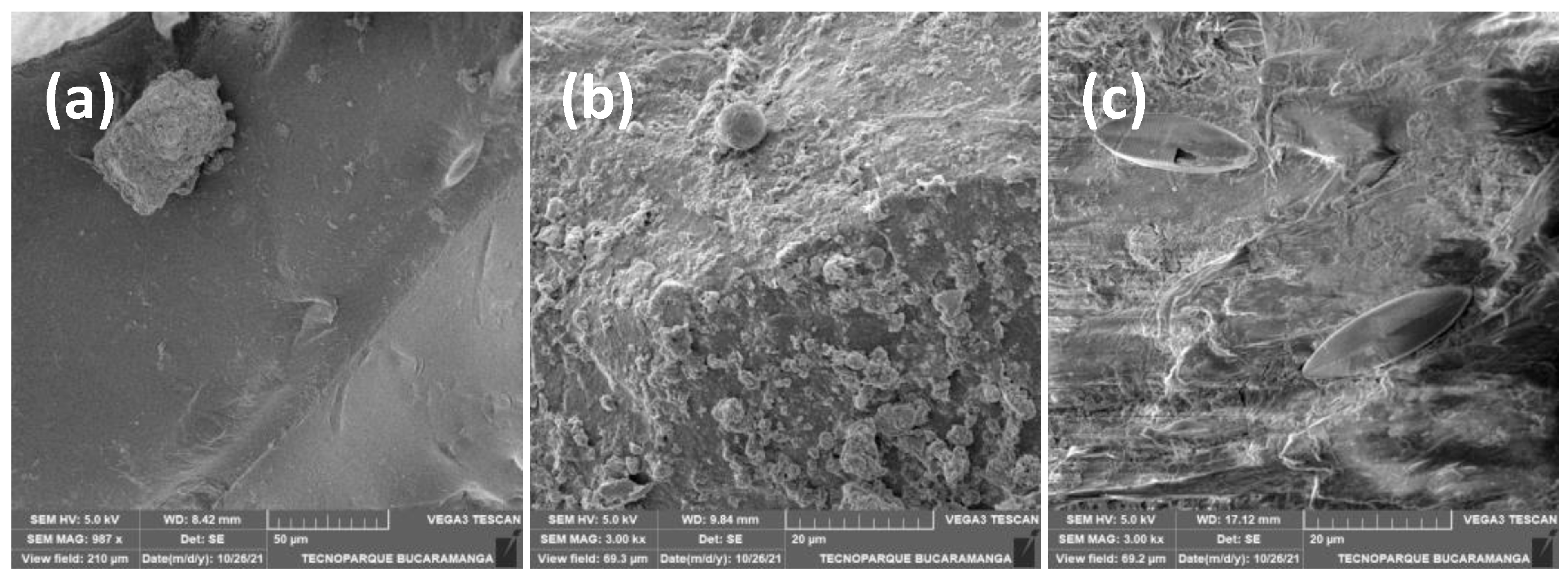

Pressure-driven membranes, including microfiltration (MF, pore sizes ~0.1–1 µm), ultrafiltration (UF, pore size ~ 0.01–0.1 µm), nanofiltration (NF, pore size < 1 nm), and reverse osmosis (RO, pore size < 1 nm), represent some of the most effective physical barriers for MP removal in both drinking water and wastewater treatment systems [39]. The primary removal mechanisms include size exclusion (sieving), interception, and adsorptive retention via physicochemical interactions between polymer surfaces and membrane materials, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Pressure-driven membrane processes illustrating the typical pore size ranges and corresponding examples of contaminants effectively removed at each membrane scale. Reprinted from Pinto et al. (2025) [40] with permission from the publisher.

In these systems, particles larger than the pore size are physically retained by the membranes. As operation proceeds, retained particles (including MPs, natural organic matter (NOM), and colloids) form a cake or fouling layer on the membrane surface [27]. This layer, though often undesirable as it increases hydraulic resistance, can also act as a dynamic secondary membrane reducing effective pore size and enhancing the capture of smaller or deformable MPs that would otherwise pass through [41]. Nevertheless, the fouling layer also leads to flux decline of 40–70% and requires frequent backwashing or chemical cleaning, which increases operational cost and maintenance demand [42].

Besides physical sieving, hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions influence removal efficiency. Hydrophobic polymers (e.g., PE and PP) exhibit greater adhesion to hydrophobic membrane materials (e.g., PVDF), leading to irreversible fouling but improved capture rates [43]. Moreover, surface charge of membranes can be tuned to attract oppositely charged MP surfaces, thus increasing attachment and improving removal efficiency. In a recent study, a layer-by-layer modified electrospun polyacrylonitrile (PAN) membrane with tunable surface charge achieved highly efficient nanoplastic removal, reaching 89.9% retention of 50 nm PS particles under low pressure (0.6 psi, or 4.14 kPa) [44]. The positively charged membrane combined ultrafiltration-level selectivity with high permeability (861 L/m2/h), where electrostatic attraction enhanced nanoplastic capture without causing significant fouling [44], demonstrating a scalable and energy-efficient solution for nanoplastic pollution control.

Additionally, surface modification, such as hydrophilic coatings, zwitterionic grafting, or TiO2 embedding, has been shown to reduce fouling and improve long-term flux stability [27]. For example, Golgoli et al. (2025) incorporated hybrid zwitterion/metal–organic framework (ZW/MOF, UiO-66-NH2) nanoparticles into forward osmosis (FO) membranes. This modification improved hydrophilicity by 73%, increased water flux by 28%, and reduced flux decline from 60% to 17% during fouling tests with microplastics and organic matter [45]. The modified membranes also achieved nearly 100% flux recovery, demonstrating strong antifouling and reversible performance [45], making them highly effective for treating wastewater containing emerging pollutants like MPs.

Pilot- and bench-scale studies repeatedly show that membrane processes achieve very high instantaneous particle retention across a wide size range (reported >90–99% for particles ≳ 0.1 µm in many pilot tests) [27]. For example, Tadsuwan and Babel (2022) found that, by adding a pilot-scale UF unit to a conventional WWTP, the removal of MPs increased from 86.14% to 96.97%, reducing MP count from 77.02 ± 7.21 particles/L in the influent to 2.33 ± 1.53 particles/L in the final effluent [46]. Although only a few studies have directly examined MP removal in full-scale treatment facilities, evidence from bench-scale experiments suggests that membrane-based systems can play a significant role in eliminating MPs [47]. Nevertheless, comprehensive field-scale investigations are still needed to confirm their effectiveness under real operational conditions.

While membrane processes are capable of achieving near-complete physical separation of MP particles down to the membrane pore size, providing predictable rejection for rigid or spherical particles, and allowing integration into modular treatment systems, these advantages are offset by several practical and environmental challenges. High energy consumption, especially in RO and NF units that operate at pressures up to 80 bar, can result in energy demands of 2–6 kWh/m3 depending on feedwater quality [48]. In addition, membrane fouling is often intensified by MP fibers and biofilm formation, while the management of MP-rich concentrates (brine) presents persistent operational concerns [27]. The retained MPs in the retentate stream require environmentally responsible disposal or subsequent treatment, such as advanced oxidation or coagulation, to ensure degradation or immobilization [49]. Moreover, the use of chemical cleaning agents (e.g., NaOCl, citric acid) to restore membrane permeability may dislodge trapped MPs, posing risks of secondary contamination if not properly managed [50].

3.2. Coagulation-Flocculation and Electrocoagulation

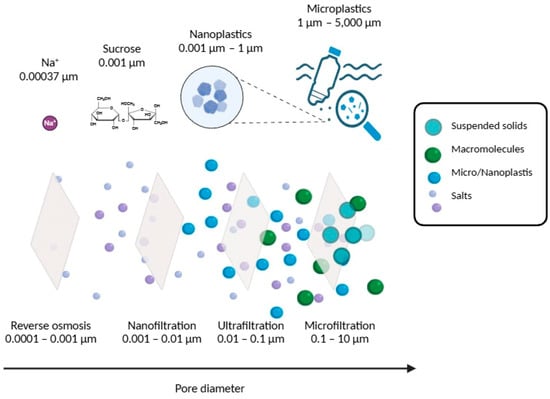

Coagulation and electrocoagulation, which rely on the neutralization of surface charge and interparticle bridging to form larger, denser flocs that can subsequently settle or float for separation [9], are among the most practical and scalable physicochemical techniques for MP removal in both drinking water and wastewater treatment systems. These processes

In chemical coagulation, trivalent metal salts such as aluminum sulfate (Al2(SO4)3), ferric chloride (FeCl3), or poly-aluminum chloride (PAC) hydrolyze in water to form metal hydroxide species (e.g., Al(OH)3, Fe(OH)3). These hydroxides neutralize the negative surface charge on MPs (typically −10 to −40 mV zeta potential) and create charge-neutral conditions conducive to aggregation. Once charge repulsion is reduced, polymeric or hydroxide bridges form, entrapping MPs and other colloids in amorphous flocs [9]. For example, Zhou et al. (2021) compared the removal efficiencies of PS and PE particles using PAC and FeCl3. The zeta potentials of PS (−15.77 mV) and PE (−14.55 mV) increased to −0.49 mV and 3.79 mV, respectively, after reaction with PAC, and to −0.57 mV and −7.76 mV after reaction with FeCl3. Over a broad pH range (5–9), the PAC system achieved higher removal efficiencies for both PS (75–80%) and PE (65–70%) compared to the FeCl3 system (55–65% and 57–63%, respectively) [51].

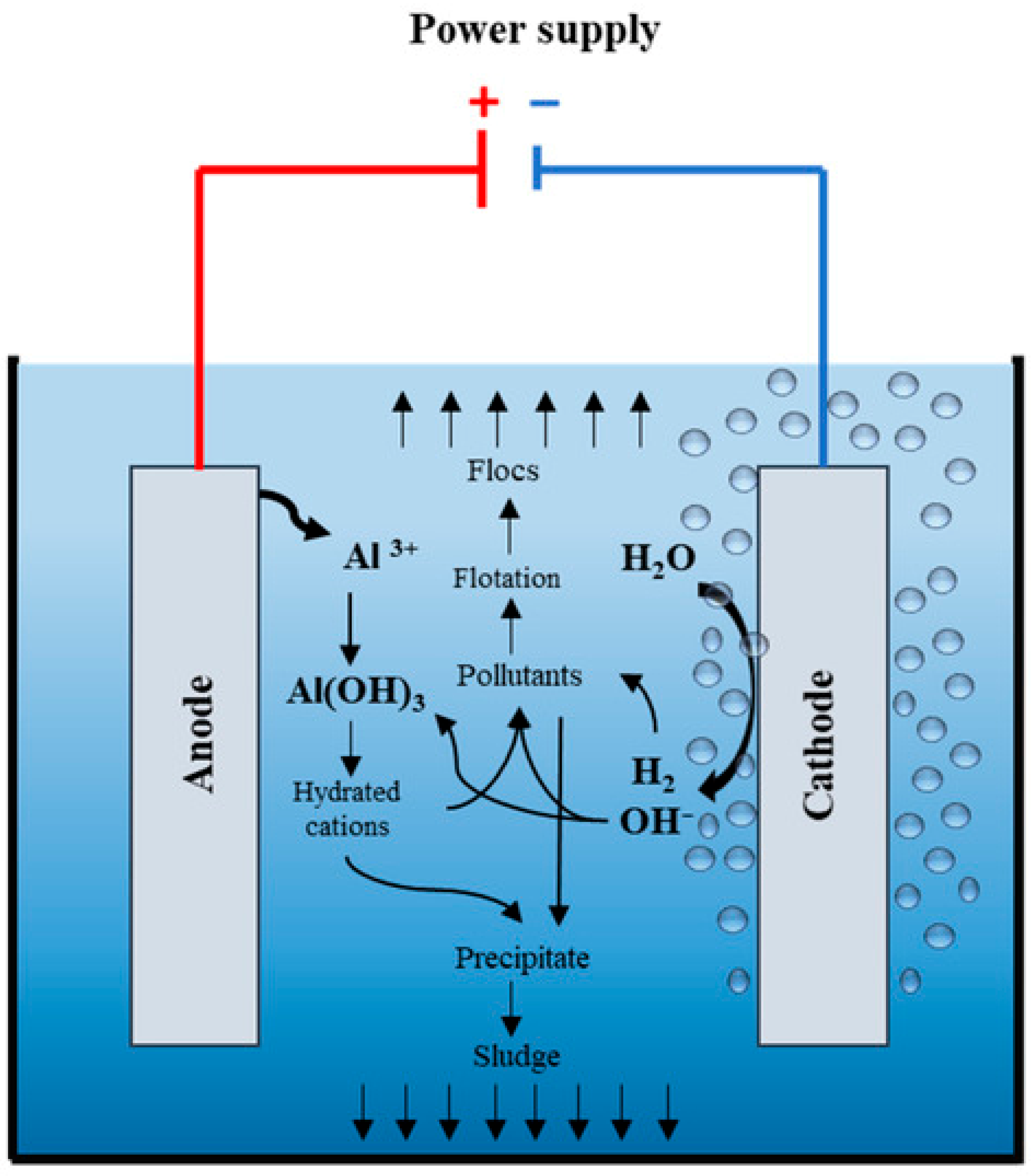

Electrocoagulation employs a similar principle but generates coagulant species in situ from sacrificial metal electrodes (Fe or Al), as shown in Figure 5. When an electric current passes through the solution, anodic dissolution produces Fe2+/Fe3+ or Al3+ ions that hydrolyze to form Fe(OH)2, Fe(OH)3, or Al(OH)3 flocs. These species not only neutralize particle charge but also adsorb and enmesh MPs via sweep flocculation. Gas bubbles (H2, O2) formed during electrolysis can aid in flotation and separation [52]. Jain et al. (2025) evaluated the performance of electrocoagulation using aluminum–aluminum (Al–Al) electrodes. The treatment achieved up to 95.54% microplastic removal at optimal conditions, with the highest efficiency (92.8%) at pH 8 and an optimal electrolyte concentration of 0.5 g/L. The system effectively removed particles sized 45–355 µm (89.8–94.1%) within 100 min [53]. The in situ coagulants were more effective due to their high surface area and freshly formed amorphous structure, enhancing MP capture.

Figure 5.

Illustration of the electrocoagulation mechanism showing in situ generation of metal hydroxide coagulants. Reprinted from Almukdad et al. (2021) [54] with permission from the publisher.

The polymer type and surrounding water chemistry play key roles in determining the efficiency of MP removal during coagulation processes [10]. The intrinsic hydrophobicity or polarity of MP polymers governs their interaction with metal hydroxide flocs [30]. Hydrophobic MPs such as PE and PP generally exhibit weak affinity for hydrophilic hydroxide flocs, resulting in limited aggregation and settling [32]. To improve removal, coagulant aids or polymeric bridging agents are often added to enhance flocculation and capture efficiency [52]. In contrast, more polar MPs (e.g., PVC) interact strongly with metal hydroxide flocs through hydrogen bonding and electrostatic attractions, which significantly improves removal rates compared with their nonpolar counterparts [30].

pH is another key factor influencing coagulation performance. Optimal removal typically occurs under near-neutral conditions (pH 6.5–8.0), where metal hydroxide precipitates (e.g., Al(OH)3 or Fe(OH)3) are most stable and effectively adsorb MP surfaces [10]. At higher pH values (>9), hydroxide species become increasingly soluble (e.g., Al(OH)4−), reducing the availability of solid flocs and thereby diminishing MP capture [32]. Similarly, at low pH, excessive protonation can hinder charge neutralization and reduce coagulation efficiency.

Additionally, water chemistry further modulates these interactions by altering the ionic environment. Elevated ionic strength, such as NaCl concentrations between 10 and 100 mM, compresses the electrical double layer surrounding MPs and hydroxide flocs, enhancing charge neutralization and aggregation [9]. However, under high turbulence or prolonged mixing, this same condition can destabilize flocs, leading to resuspension or re-entrainment of smaller MP aggregates [55]. These above findings underscore the intricate interplay between polymer properties, coagulant chemistry, and water matrix conditions that collectively dictate MP removal efficiency.

Coagulation and electrocoagulation offer several advantages for MP removal. These processes are simple, scalable, and compatible with existing clarification infrastructure, making them practical for integration into conventional WTPs and WWTPs [56]. When optimized for coagulant dosage and pH, they can effectively remove a wide range of MP types [30]. Electrocoagulation, in particular, eliminates the need for external chemical dosing and tends to produce less sludge compared with traditional coagulation [53].

However, several challenges remain. Conventional coagulation generates substantial volumes of MP-laden sludge that require dewatering and safe disposal; if this sludge is reused in agriculture or disposed of in landfills, MPs may re-enter the environment [57]. Electrocoagulation processes, while chemically efficient, can be energy-intensive, with reported energy demands ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 kWh/m3 depending on current density and electrode configuration [58]. Both methods struggle to remove nanoscale plastics (<1 µm), as their strong Brownian motion and small surface area hinder destabilization and floc attachment [56]. Additionally, electrocoagulation systems face electrode passivation due to oxide buildup, which lowers current efficiency and necessitates regular maintenance, cleaning, or polarity reversal [59].

3.3. Adsorption and Biochar-Based Removal

Engineered adsorbents, including activated carbon, magnetic biochar, and functionalized nanomaterials, have emerged as promising tools for MP removal due to their diverse interaction mechanisms and tunable surface properties [60]. These materials capture MPs primarily through hydrophobic interactions, van der Waals forces, electrostatic attraction, and mechanical entrapment within porous structures [60].

Activated carbon, with its high specific surface area (typically 500–2000 m2/g) and extensive pore network, effectively adsorbs hydrophobic polymers such as PE and PP, achieving removal efficiencies exceeding 90% under optimized conditions [61]. For example, a recent study used granular activated carbon (GAC) to adsorb PP from wastewater through physical interactions (pseudo-first-order kinetics, Freundlich isotherm). The adsorption achieved 43% removal at 0.5 g/L and up to 90% removal at 1.5 g GAC/L [12].

Biochar, derived from agricultural or municipal residues, offers an eco-friendly and low-cost alternative [62]. When magnetically modified (e.g., with Fe3O4 nanoparticles), biochar enables facile separation and recovery using external magnetic fields while maintaining high sorption capacity, up to 80–95% MP removal from secondary effluents has been reported [11]. Surface functionalization further enhances performance: oxygenated or nitrogen-doped groups improve affinity toward polar MPs such as polyamide (PA) and PVC via hydrogen bonding and dipole interactions [63]. The study by Subair et al. (2024) demonstrated that banana peel–derived biochar effectively removes PS from water, achieving up to 92.16% removal efficiency under optimal conditions (6 cm bed height, 3 mL/min flow rate, 0.05 g/L concentration, 150–300 µm MPs) [64]. As reported, the performance biochar is closely related to its physicochemical properties, ruled by the production conditions [65]. Zhang et al. (2024) found that London Plane bark biochar produced at 550 °C achieved the highest PS adsorption capacity (60.05 mg/L), with removal driven by physical trapping, surface complexation, hydrogen bonding, and π–π interactions [66].

Likewise, nanomaterials such as graphene oxide and TiO2 composites introduce additional binding mechanisms, combining adsorption with catalytic degradation under light irradiation [67]. By leveraging the structural multifunctionality and high reactivity of nanomaterials, researchers have demonstrated significant potential to overcome the limitations of conventional treatment technologies and advance sustainable microplastic remediation. For example, a recent study showed that graphene oxide–based metal oxide nanomaterials can effectively degrade PE under UV irradiation, achieving 35.7–50.5% mass loss after 480 min following pseudo–first-order kinetics [68]. In another study, researchers developed a novel Fe-based nanocatalyst (Fe0/FeS) that enhanced humic substance formation and accelerated MP degradation during composting. The catalyst increased humic acid content to 71.01 mg/kg and the humification index to 4.91, while reducing MP concentration from 22,792 to 9487 particles/kg. Fe0/FeS promoted the transformation of small (<50 µm) and large (>1000 µm) MPs into medium-sized (50–200 µm) particles through enhanced ·OH generation and microbial activity, offering an effective strategy for simultaneous MP mitigation and compost quality improvement [69].

As discussed above, engineered adsorbent-based methods have emerged as promising approaches for MP removal due to their low energy demand, versatility, and adaptability [17]. These processes offer tunable surface chemistry, allowing selective targeting of specific polymer types or particle sizes. The use of engineered or functionalized biochars enhances hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions, improving affinity toward diverse MP types [70]. Moreover, magnetic sorbents and magnetically modified biochars enable rapid post-treatment separation through magnetic recovery, minimizing filtration or sedimentation steps [11]. Another major advantage lies in the potential for sorbent regeneration using thermal or solvent treatments, extending material lifespan and reducing overall operational costs [71].

However, several challenges constrain the large-scale implementation of adsorbent-based MP removal. The sorption capacity of materials tends to decrease after multiple regeneration cycles, and the efficient capture of sub-10 µm particles remains difficult due to diffusion limitations and weak surface interactions [12]. Additionally, spent sorbents concentrate MPs, necessitating environmentally safe disposal or effective regeneration methods to prevent secondary contamination [16]. At the system level, scaling adsorption columns for high-flow municipal water or wastewater streams poses engineering and economic challenges, especially in maintaining long-term material stability and consistent performance [64]. Consequently, while adsorbent-based approaches are attractive for sustainable MP mitigation, further research is needed to optimize regeneration, enhance small-particle capture, and validate their durability under real-world treatment conditions.

3.4. Advanced Oxidation Processes

Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) represent a class of treatment technologies that rely on the in situ generation of highly reactive oxygen species (ROS), primarily hydroxyl radicals (·OH), ozone (O3), superoxide anions (O2·−), and singlet oxygen (1O2), to degrade persistent organic pollutants, including MPs. These radicals are non-selective and possess extremely high redox potentials (e.g., E°(·OH/H2O) = +2.8 V), enabling them to attack the carbon–carbon and carbon–hydrogen bonds in polymer chains through oxidation, chain scission, and, in advanced cases, partial mineralization to CO2 and H2O [72]. The fundamental mechanism involves radical-induced abstraction of hydrogen atoms from the polymer backbone, leading to the formation of carbon-centered radicals that undergo further oxidation or fragmentation [72]. Over time, this results in reduced molecular weight, increased surface roughness, and the introduction of oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., –COOH, –OH), which enhance polymer hydrophilicity and facilitate subsequent biodegradation or removal through coagulation and adsorption [17].

Various AOPs have been studied for MP degradation, including photocatalysis (e.g., TiO2/UV, ZnO/visible light), ozonation, Fenton and photo-Fenton reactions (Fe2+/H2O2, Fe3+/UV/H2O2), and electrochemical oxidation [72]. Photocatalytic oxidation using TiO2 or ZnO catalysts has shown significant potential due to its low chemical input and ability to harness solar energy. For instance, Aragón et al. (2025) reported that photocatalytic degradation using TiO2 offers a promising approach for breaking down PE under light irradiation, achieving 34% mass loss and a 58.5% increase in carbonyl index after 8 h. Consecutive treatment cycles further enhanced degradation to 54% mass loss, confirming mineralization through CO2 and short-chain acid formation, while toxicity tests showed the treated water remained suitable for irrigation [73]. Similarly, ozonation and O3/H2O2 treatments can alter the physical and chemical properties of MPs in WTPs, leading to increased dissolved organic carbon (0.8–28 mg/L) and leaching of harmful plasticizers such as phthalic acid esters. PE showed the highest degradation (up to 26.7% surface loss), but the oxidation processes also caused unfavorable changes in treated water quality [49], underscoring the need for greater awareness of MP–treatment interactions. Additionally, AOPs have potential to chemically degrade polymer chains and increase biodegradability, making them possible to be coupled with downstream biological polishing to remove oxidation products [72].

Despite their effectiveness, AOPs face notable challenges when applied to MP removal from real water matrices. One key limitation is the potential transformation of microplastics into nanoplastics, which are more difficult to separate and may pose higher ecotoxicological risks due to their enhanced mobility and reactivity [74]. Furthermore, radical generation efficiency can be suppressed in natural waters rich in radical scavengers such as bicarbonates and natural organic matter [72], reducing degradation performance. AOPs can also entail relatively high energy or chemical demand, as seen in UV-based and electrochemical systems [75], thus limiting their large-scale implementation. On the other hand, coupling AOPs with biological or membrane processes offers synergistic benefits. AOPs can oxidize and roughen MP surfaces, improving biofilm attachment and subsequent biodegradation [76].

3.5. Biodegradation and Biological Approaches

Microbial and enzymatic degradation represents an emerging and environmentally benign approach for microplastic MP removal, leveraging the natural ability of microorganisms and their enzymes to depolymerize synthetic polymers into smaller, biodegradable intermediates [17]. In this process, microbial consortia or purified enzymes attack polymer chains through hydrolytic or oxidative cleavage, producing oligomers and monomers that can subsequently be metabolized into CO2, H2O, and biomass [17]. Among the most studied enzymes are PETase and MHETase, initially discovered from Ideonella sakaiensis and known for their ability to degrade PET into terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol [77]. Laccases and peroxidases, produced by fungi such as Trametes versicolor and Phanerochaete chrysosporium, catalyze oxidation reactions that introduce ROS into the polymer surface, initiating chain scission in polymers like PE, PP, and PS [77,78,79].

Implementation strategies typically fall into three categories: (1) enzyme-treatment reactors, where purified or immobilized enzymes are applied under controlled conditions to depolymerize MPs; (2) bioaugmentation, which introduces MP-degrading microbes into water treatment systems; and (3) engineered microbiomes, where microbial consortia are optimized or genetically modified to enhance degradation rates [17]. For instance, Son et al. (2019) engineered a thermally stable IsPETase variant (S121E/D186H/R280A) to enhance PET biodegradation, showing an 8.81 °C increase in melting temperature and a 14-fold higher degradation activity at 40 °C compared to the wild type [80]. This advancement offers a significant step toward efficient enzymatic PET degradation under mild conditions. Aer et al. (2022) analyzed the kinetics of Ideonella sakaiensis PETase for PET degradation. Enhanced expression of the IsPETaseMut enzyme in E. coli was achieved through chaperone co-expression and fusion systems, yielding up to 80 mg/L of soluble enzyme, up to 12.5 times higher than standard expression. The NusA-fused IsPETaseMut exhibited improved PET adsorption and reduced product inhibition, leading to more efficient long-term PET degradation [81].

Notably, biological degradation of MPs remains relatively slow compared to physical or chemical removal methods. A recent study estimated that the degradation half-life of 11 different MPs ranges from 67 to 116 days, and the highest 30-day removal observed was only 13.4% [82]. In addition, enzymatic activity is often polymer-specific, and crystalline regions within plastics resist microbial attack due to their compact structure and limited surface accessibility [77]. Moreover, environmental conditions such as temperature, pH, and nutrient availability greatly influence degradation kinetics, making field-scale applications challenging [17]. Another concern lies in the incomplete degradation of MPs, which can yield smaller plastic fragments or soluble oligomers that persist in aquatic environments [83]. Nonetheless, biological and enzymatic degradation presents a sustainable and low-energy pathway for long-term mitigation of microplastic pollution, especially when integrated with physicochemical pretreatments (e.g., ozonation, UV irradiation) that enhance polymer surface accessibility [16]. Future research focuses on metabolic pathway optimization, synthetic microbial communities, and enzyme immobilization technologies to overcome current bottlenecks and enable scalable deployment in wastewater and water treatment systems [17].

3.6. Hybrid and Integrated Systems

Hybrid and integrated treatment systems represent a promising evolution in MP removal technologies, designed to harness the synergistic advantages of multiple processes while mitigating the limitations of each individual method [17]. The underlying principle is sequential or simultaneous coupling (e.g., coagulation–membrane, membrane–AOP, or adsorption–biological combinations) to enhance overall removal efficiency, reduce fouling, and improve effluent quality. These hybrid configurations can be tailored to specific water matrices (e.g., drinking water, wastewater, industrial effluents) and target MP characteristics such as size, shape, and polymer type [84].

A widely adopted integration is coagulation followed by membrane filtration, where coagulation serves as a pre-treatment step that destabilizes and aggregates MPs into larger flocs, thus mitigating membrane fouling and enhancing capture efficiency. For example, in a recent study, laundry wastewater containing 9000–11,000 MPs/L (mainly PE fibers) was effectively treated using combined coagulation and ultrafiltration, achieving up to 98.3% MP removal while extending membrane lifespan by reducing pore blocking and surface fouling [85]. Similarly, in water treatment systems, experimental results showed that coagulation achieved an optimal removal efficiency of 37.0–56.0% for the five types of MPs, while subsequent ultrafiltration nearly eliminated all remaining particles [86]. Additionally, Lin et al. (2024) evaluated electro-coagulation as a pretreatment to reduce nanofiltration membrane fouling during the reclamation of microplastic-contaminated secondary effluent. Optimized electro-coagulation (0.2 A) effectively mitigated microplastic-induced fouling and improved pollutant rejection, as supported by modeling and simulations showing strong humic-Fe complex formation that enhanced membrane performance [87].

Meanwhile, biochar-based adsorption–membrane hybrid systems seem to be one of the most promising frontiers for sustainable MP removal. These systems integrate the high adsorption capacity and tunable surface chemistry of engineered biochar with the precise physical separation of membrane filtration, achieving both pollutant capture and particle retention. When incorporated as a pre-filtration or in situ membrane layer, biochar minimizes membrane fouling by adsorbing MPs before pore blockage occurs, extending operational life and reducing energy demand [88]. Recent studies have reported complete MP removal from river water and sewage water by integrating biochar into sand filtration columns [89]. Hybrid biochar-filtration systems are particularly remarkable for their effectiveness in removing nanoplastics with significantly smaller particle sizes, achieving overall MP removal efficiencies exceeding 95% while maintaining lower transmembrane pressures [90]. Furthermore, biochar’s renewable and low-cost nature enhances the environmental and economic sustainability of these hybrids [71]. The ability to regenerate and reuse biochar adsorbents, coupled with the potential for modular integration into existing treatment trains, positions adsorption–membrane hybrids as a scalable, circular-solution pathway for next-generation MP mitigation in both municipal and industrial water systems [89].

Another effective configuration involves membrane–AOP coupling, where oxidation processes such as ozonation, photocatalysis, or electrochemical oxidation are applied upstream or within the membrane module. AOPs oxidize and fracture MPs into smaller fragments or introduce oxygen-containing functional groups that enhance their hydrophilicity and subsequent retention by membranes. For instance, Luo et al. (2022) showed that the electro-hybrid ozonation–coagulation process effectively removed over 90% of surfactants and microplastics from laundry wastewater under optimal conditions (15 mA·cm−2, 66.2 mg L−1 ozone) [91]. In addition, ROS generated during AOPs can suppress biofilm formation, offering dual benefits of contaminant degradation and membrane fouling control. However, process optimization is critical to minimize over-oxidation, which can transform MPs into nanoplastics or soluble organics [83].

Hybrid adsorption–biological systems have also gained attention for their potential to combine physical entrapment and biodegradation. Porous adsorbents such as biochar or activated carbon serve as scaffolds that both capture MPs and host microbial biofilms capable of enzymatic degradation. Zou et al. (2024) found that chicken manure–and wood waste–derived biochars significantly enhanced the degradation of polylactic acid MPs in soil over one year by increasing surface oxidation, fragmentation (<100 µm), and carbon loss. The mechanisms involved alkaline, oxidative, and microbial degradation pathways, with manure biochar promoting Fe2+-driven Fenton reactions and ammonolysis, while wood biochar facilitated nitrate reduction and surface radical oxidation [92]. Moreover, simultaneous MP degradation and adsorbent regeneration can be achieved through the integration of thermal treatment. Wang et al. (2021) developed Mg/Zn-modified magnetic biochars that achieved high removal efficiencies for 1 µm polystyrene microplastics—94.81% for MBC, 98.75% for Mg-MBC, and 99.46% for Zn-MBC—through electrostatic and chemical interactions. The materials also enabled simultaneous microplastic degradation and adsorbent regeneration via thermal treatment, maintaining >94% efficiency after five reuse cycles, demonstrating strong potential for sustainable microplastic removal [93].

At the pilot scale, integrated process trains, such as coagulation/flocculation followed by ultrafiltration or sedimentation combined with biofiltration, have demonstrated sustained removal efficiencies above 90%, with manageable fouling rates and moderate energy consumption (typically 0.8–1.5 kWh/m3) [94]. For example, Chishty et al. (2025) developed a pilot-scale integrated treatment system combining aeration, sedimentation, sand filtration, and reverse osmosis to remove microplastics, achieving removal efficiencies between 66% and 93% across different water types [95]. Transparent fibers (>90%) were the dominant microplastic type, and statistical analyses confirmed the system’s effectiveness and potential for mitigating microplastic pollution in aquatic environments [95]. These systems benefit from distributed stress among treatment stages: physical capture in early steps, oxidative or biological degradation in subsequent ones, and final polishing via adsorption or filtration. Nonetheless, challenges remain in scaling these systems to full operation, particularly concerning process control, energy optimization, and management of byproducts such as sludge or oxidized fragments.

As summarized in Table 1, hybrid systems offer a high-performance and adaptable framework for MP removal, often outperforming single-process technologies in both efficiency and resilience. Their ability to integrate coagulation, filtration, oxidation, and biodegradation mechanisms allows for multi-barrier protection against diverse MP pollutants. Future directions should emphasize process intensification, real-water validation, and techno-economic optimization to facilitate their adoption in full-scale municipal and industrial water treatment infrastructures.

Table 1.

Summary of the performance advantages of hybrid treatment systems for MP removal.

4. Comparative Evaluation of Technologies

A comprehensive evaluation of emerging and conventional technologies for MP removal must consider multiple performance criteria beyond simple removal efficiency. Factors such as scalability, energy demand, operational cost, byproduct risk, and overall environmental sustainability are crucial in determining real-world applicability. Although laboratory studies frequently report high removal efficiencies, translating these results into practical, large-scale systems involves tradeoffs that influence economic and environmental outcomes.

4.1. Removal Efficiency

Among the available technologies, membrane-based processes consistently achieve the highest removal efficiencies, typically ranging from 90 to 99% for MPs larger than 1 µm [27]. RO and NF are especially effective due to their small pore sizes and strong size-exclusion capability. However, performance can decline when fouling or concentration polarization occurs [17]. Coagulation–flocculation processes show moderate to high removal efficiencies (70–97%) depending on coagulant type, polymer charge, and pH [56]. Electrocoagulation often achieves comparable or better removal (~95%) by generating coagulant species in situ [58]. Adsorption methods remove MPs primarily through surface interactions and mechanical trapping, with efficiencies between 70 and 95% depending on adsorbent surface chemistry [17]. AOPs do not directly remove MPs but degrade or fragment them, achieving partial removal (40–80%) or transformation into smaller fragments or nanoplastics [72]. Biological degradation remains in early stages, typically showing low rates (<30% mass loss over weeks) due to slow enzyme kinetics and substrate accessibility [17]. Hybrid systems, combining coagulation, membrane, and/or AOPs, exhibit the highest overall performance (>95%), leveraging synergistic effects to enhance both physical removal and degradation [117].

4.2. Scalability

Scalability varies widely across technologies, with large differences in engineering compatibility, energy requirements, and operational reliability. Coagulation–flocculation is the most scalable, being easily integrated into existing water and wastewater treatment infrastructure with minimal retrofitting [10]. Full-scale plants already operate rapid-mix and flocculation basins, and MP removal efficiencies of 60–90% reported in municipal facilities demonstrate practical viability [56]. The primary constraint is increased sludge volume, typically 20–40% higher when optimized for MP capture [10]. Electrocoagulation is also scalable, with modular reactors that can be expanded linearly with flow. But it is limited by electrode lifespan and energy management requirements [17]. Membrane systems can scale to municipal capacities, as demonstrated in large UF and RO plants. However, membrane fouling increases sharply when exposed to MP-rich waters. Studies show 20–35% reductions in flux within days without aggressive backwashing. Replacement costs (USD 30–80/m2) and high pressure requirements (up to 1.5–2.5 kWh/m3 for RO) constrain widespread adoption [27]. Adsorption processes, especially those using low-cost biochars or magnetic composites, offer scalable solutions for decentralized or polishing applications, with performance maintained across pilot demonstrations treating 1–10 m3/day [71]. Biochar costs as low as USD 0.3–1.2/kg make them suitable for decentralized or polishing units, although saturation and regeneration remain operational limitations [16]. In contrast, AOPs and biological treatments face scalability constraints: AOPs due to high energy requirements (1–5 kWh/m3) and catalyst recovery issues, and biodegradation due to long residence times (24–72 h even under optimized lab conditions) and narrow substrate specificity that is difficult to maintain in flow-through systems [75]. Full-scale oxidation reactors are feasible, but for MP removal, AOPs often fragment plastics rather than fully mineralize them unless exposure times are long, increasing cost and energy burden [49]. Hybrid systems show strong potential but remain pre-commercial. For example, coagulation–membrane and magnetic adsorption–oxidation hybrids achieve >95% MP removal in pilot systems, yet require advanced process control and synchronized dosing algorithms. These complexities limit large-scale implementation of hybrid systems to pilot or semi-industrial stages thus far.

4.3. Energy Demand

Energy intensity is a critical determinant of sustainability. Membrane processes exhibit moderate to high energy demand, typically 0.8–2.5 kWh/m3, with RO at the upper end (3–4 kWh/m3) due to high transmembrane pressure requirements [118]. Nevertheless, recent research showed that this high energy demand can be significantly reduced using novel configurations such as closed-circuit RO instead [119]. Coagulation itself has low energy demand (<0.2 kWh/m3), but electrocoagulation requires 0.5–2.5 kWh/m3, depending on current density and electrode configuration [120]. Adsorption is energy-efficient during operation but can incur additional costs for adsorbent regeneration [93]. AOPs are among the most energy-intensive technologies, often exceeding 3–5 kWh/m3 due to UV lamps, ozone generation, or electrochemical oxidation [121]. Biological systems generally operate at low energy inputs but require long reaction times (weeks), making them less practical for continuous treatment. Hybrid systems can balance energy use by distributing load across stages, often achieving high performance with 1–2 kWh/m3 total consumption [122].

4.4. Cost

Operational and capital costs are decisive for large-scale feasibility. Coagulation–flocculation is the most cost-effective (typically $0.05–0.20/m3) due to widespread availability of reagents and equipment [103]. Membrane filtration incurs higher capital costs (up to $0.5–1.5/m3) due to membrane replacement and cleaning needs [123]. Electrocoagulation and AOPs are more expensive ($0.5–2.0/m3) due to electrical and chemical inputs [124]. Adsorption systems, depending on the sorbent, vary widely: activated carbon is relatively costly, while biochar derived from waste biomass provides a low-cost and sustainable alternative, particularly when produced through renewable energy sources such as solar radiation [125]. Biological systems are inexpensive in materials but slow, limiting cost-effectiveness in high-throughput operations [17]. Hybrid systems require higher initial investment but offer long-term economic benefits through reduced fouling, extended equipment lifespan, and minimized chemical usage [84].

4.5. Byproduct Risk

Coagulation–flocculation generates the highest residual burden, producing sludge containing entrapped MPs and coagulant–polymer complexes and raising concerns about secondary pollution during sludge disposal or reuse [16]. Full-scale studies show that 60–90% of MPs are transferred to sludge, which raises the risk of secondary release during land application or landfill leaching, particularly for small fibers (<300 µm) that may desorb under shear [56]. Electrocoagulation reduces synthetic chemical addition but produces metal-rich hydroxide sludge. Typical iron or aluminum accumulation reaches 1–4 g/L of sludge, requiring classification as industrial waste in many jurisdictions [87]. Electrode dissolution further introduces trace metals that complicate downstream disposal [58]. Membrane processes concentrate MPs in brine or retentate streams, often increasing MP mass per unit volume by 10–50× relative to influent, which must be managed to prevent re-release, particularly in plants lacking zero-liquid-discharge systems [27]. AOPs pose unique transformation risks. While capable of degrading polymers, incomplete oxidation can convert microplastics into nanoplastics, increasing mobility and toxicological uncertainty [117]. For example, UV/H2O2 and photocatalysis have been shown to reduce particle size by 40–70% without full mineralization, creating high-surface-area fragments that are more reactive and difficult to capture [94]. Adsorption technologies generate solid waste streams when spent sorbents are not regenerated. Biochar or magnetic composites can accumulate large MP loads (up to 100–500 mg MP per g sorbent in some studies), and regeneration requires thermal, chemical, or magnetic recovery processes that may not be feasible at scale [90]. Without proper regeneration infrastructure, spent sorbents may become secondary pollution sources. Biological treatments have the lowest byproduct risk, producing primarily CO2, water, and biomass. However, these systems operate slowly and may only partially degrade certain polymers, potentially leaving persistent oligomers that require additional treatment [83]. Hybrid systems can mitigate some byproduct risks by distributing the pollutant load across multiple capture mechanisms, e.g., combining coagulation and membrane filtration can reduce sludge volume and enhance capture of fragments before discharge [32].

4.6. Environmental Sustainability

From an environmental sustainability perspective, biochar adsorption and biological degradation stand out due to their use of renewable resources and low chemical inputs [71]. Life-cycle assessments (LCAs) show that biochar production from waste biomass can result in net-negative carbon footprints (−0.3 to −1.2 kg CO2-eq per kg biochar) due to carbon sequestration [126], while biological routes avoid chemical reagents and generate benign end products. However, biological processes are slow and often polymer-specific, limiting their standalone applicability [17]. Conventional coagulation–flocculation is moderately sustainable, with a relatively low operational carbon footprint (e.g., 0.05–0.15 kg CO2-eq/m3 treated, depending on coagulant dose). Yet its sustainability is offset by the environmental burden of sludge disposal and the upstream impacts of aluminum or iron salt production [56]. In many systems, sludge management contributes 40–60% of total GHG emissions, highlighting the need for improved recovery or reuse strategies [127]. Electrocoagulation and AOPs are less sustainable when powered by non-renewable electricity sources, though integration with renewable energy or waste-heat recovery could improve their footprint [128]. Membrane systems provide high-quality treated water but are resource-intensive, with significant embodied energy in membrane fabrication and high operational demand. LCA studies report 0.3–1.0 kg CO2-eq/m3 for RO-based systems when accounting for pumping energy and membrane replacement [129]. Sustainability improves when operated under optimized flux conditions or when powered by low-carbon electricity [129]. Hybrid systems show potential for sustainability when synergistically designed to minimize energy and material waste, combining complementary strengths (e.g., low-chemical coagulation with energy-efficient membranes or biologically active filtration). For example, biologically active filtration paired with low-pressure membranes further reduces chemical consumption while preserving effluent quality.

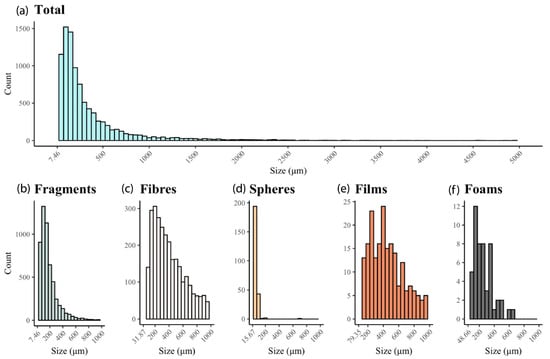

5. Front-Runner Technologies for Microplastic Removal

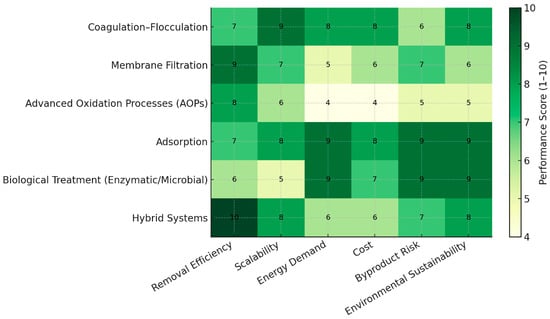

A comparative evaluation of MP removal technologies was conducted using a semi-quantitative scoring framework summarized in a heat map (Figure 6). The purpose of this scoring system is to integrate the large body of heterogeneous literature into an interpretable, side-by-side comparison of major technology classes, rather than to provide a prescriptive ranking. This assessment was based on a structured review of the performance data and trends reported in the literature cited throughout this review [17,27,56,58,71,72,84,93,117,122].

Figure 6.

Comparative heat map of microplastic removal technologies using a 1–10 performance scale.

Six criteria (discussed in Section 4.1, Section 4.2, Section 4.3, Section 4.4, Section 4.5 and Section 4.6) were evaluated for each technology: Removal Efficiency, Scalability, Energy Demand, Cost, Byproduct Risk, and Environmental Sustainability. Each criterion was scored on a 1–10 scale, where higher values represent more favorable performance. To ensure transparency and reproducibility, a standardized rubric was developed (Table 2) that maps observed performance ranges in the literature to defined score intervals. For example, technologies reporting removal efficiencies > 90% under typical operating conditions were assigned scores of 8–10, while those consistently <50% received scores of 1–3. Similar interval-based rubrics were defined for cost, energy intensity, scalability, and byproduct formation.

Table 2.

Scoring rubric for each evaluation criterion used in the comparative heat map (Figure 6).

Reported performance values vary across studies due to differences in feedwater characteristics, particle sizes, operating conditions, and analytical methods. To minimize bias:

- When quantitative data were available, median ranges from multiple studies were used.

- Conflicting findings were addressed by considering dominant performance trends across a minimum of 3 independent studies.

- Scores were normalized to the 1–10 scale using the predefined rubric (Table 2) to maintain consistency among criteria.

- All criteria were weighted equally because the review’s aim is descriptive comparison rather than decision optimization; this avoids imposing subjective value judgements on readers.

- Where numerical data were insufficient (e.g., sustainability or byproduct risk), expert informed qualitative synthesis was applied following the rubric categories. This approach aligns with accepted practices in multi-criteria review-based assessments.

- It should be noted that scores presented in Table 2 are inherently generalized and should not be interpreted as prescriptive or universally applicable, as performance can vary substantially depending on MP characteristics and operational settings.

The comparative heat map (Figure 6) highlights clear contrasts among MP removal technologies when evaluated across six standardized criteria. As previously discussed, no single approach provides a universal solution. Membrane-based and hybrid systems demonstrate the highest removal efficiencies but demand careful consideration of cost, energy use, and fouling control. In contrast, distinguished by their cost-effectiveness and ease of integration into existing facilities, coagulation and adsorption offer the most practical routes for near-term application. These methods achieve moderate to high MP removal with low operational complexity, though their performance depends strongly on coagulant dosage, particle properties, and sludge management requirements. On the other hand, AOPs offer complementary advantages by chemically degrading persistent polymeric particles, yet their energy intensity and potential generation of smaller nanoplastics necessitate downstream treatment. Lastly, biological and enzymatic approaches, while still in early development, provide environmentally benign pathways with minimal secondary pollution. However, their current limitations lie in slow reaction kinetics and substrate specificity, which hinder scale-up.

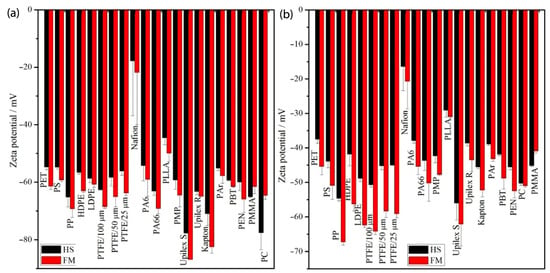

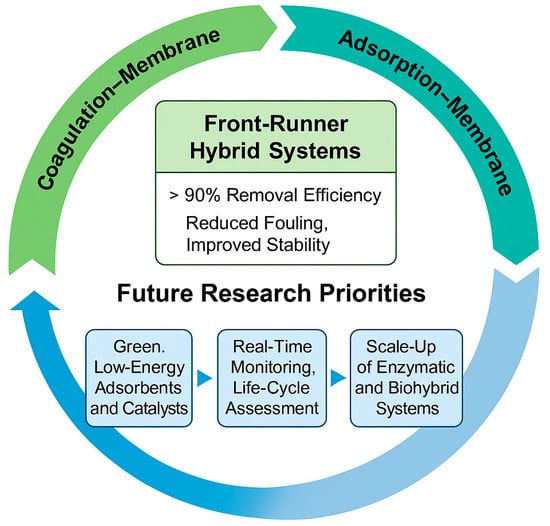

Conclusively, among the evaluated technologies, hybrid systems (especially those integrated with membrane filtration) emerge as leading candidates for effective MP removal. As shown in Figure 6, hybrid systems present the most balanced and scalable approach, combining high efficiency with manageable costs and reduced environmental trade-offs. Hybrid configurations deliver synergistic benefits by integrating mechanical capture, adsorption, and oxidative degradation, achieving over 95% removal in both pilot- and full-scale studies [85]. Their flexibility allows optimization for diverse wastewater compositions while mitigating fouling and enhancing long-term stability. Future research should focus on optimizing hybrid configurations and advancing low-energy membrane materials, bio-based adsorbents, and enzymatic polishing techniques. Such integrated, context-specific solutions will be essential for achieving sustainable and comprehensive MP removal at full scale (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Conceptual roadmap for advancing microplastic removal technologies.

6. Future Research and Technological Directions

Despite significant progress in identifying and testing physical, chemical, and biological methods for MP removal, challenges remain in achieving full-scale, cost-effective, and sustainable solutions. The next generation of MP treatment technologies should move beyond mere particle capture toward holistic, integrated, and circular approaches that address removal, degradation, and valorization concurrently.

6.1. Development of Next-Generation Membranes and Low-Fouling Materials

Future work should focus on advanced membrane materials with anti-fouling, self-cleaning, and selective functionalities. Nanocomposite and bio-inspired membranes (incorporating graphene oxide, zwitterionic coatings, or photocatalytic layers) can enhance hydrophilicity, reduce energy demand, and allow in situ degradation of MPs. Integration of membrane bioreactors (MBRs) with biological polishing or enzymatic coatings may further extend operational lifetimes while reducing the need for frequent chemical cleaning. Additionally, adaptive membrane modules, capable of dynamic pore-size regulation or responsive operation under changing flow conditions, could improve scalability and process control in large municipal and industrial systems.

6.2. Hybrid and Multi-Barrier Systems for Synergistic Removal

Hybrid configurations are expected to dominate the next generation of MP treatment technologies. Combining coagulation–membrane filtration, adsorption-membrane, AOP–adsorption, or biofiltration–membrane units can harness the complementary strengths of each process, including but not limited to rapid aggregation, physical retention, oxidative breakdown, and biological degradation. Research should focus on process optimization, understanding interfacial mechanisms between MPs and treatment media, and the long-term behavior of polymer residues in hybrid reactors. Pilot and full-scale studies are especially needed to assess the energy-to-removal ratio, operational stability, and environmental footprint under real wastewater conditions.

6.3. Advancing Enzymatic and Microbial Biodegradation Pathways

Biological degradation of MPs represents one of the most sustainable long-term strategies. However, its practical implementation requires substantial advances in enzyme discovery, microbial engineering, and reactor design. Future studies should focus on metagenomic screening and directed evolution to identify and optimize enzymes such as PETase, MHETase, cutinase, and laccase for enhanced catalytic efficiency under environmental conditions. Engineering synthetic microbial consortia with complementary metabolic pathways may enable complete mineralization of common polymers like PET, PS, and PE. Bioreactor designs that couple enzymatic pretreatment with biological polishing (e.g., in moving bed biofilm reactors or membrane bioreactors) could facilitate continuous, scalable operation.

6.4. Integration of Detection, Monitoring, and Smart Process Control

The future of MP management depends not only on removal but also on real-time detection and adaptive control. Current analytical methods (e.g., FTIR, Raman microscopy, pyrolysis-GC/MS) are accurate but slow and resource-intensive. Emerging optical sensing, microfluidic, and machine-learning–based approaches hold potential for in situ quantification and characterization of MPs during treatment. Integrating AI-assisted monitoring with treatment systems can enable feedback-controlled operation, where dosage, filtration rate, or oxidation intensity automatically adjusts to influent MP concentration or size distribution, improving both efficiency and resource use.

6.5. Addressing Secondary Pollution and Advancing Circular Approaches

A major barrier to MP treatment sustainability lies in the secondary pollution associated with sludge generation, nanoplastic fragments, and concentrated waste streams. Future research should aim to minimize these byproducts through process redesign, magnetic separation, and biochar-based adsorbent recovery. In addition, the valorization of captured MPs and composite sludge through thermal conversion (e.g., pyrolysis or hydrothermal carbonization) could convert waste into useful carbonaceous materials, aligning with circular economy principles. Life cycle assessment (LCA) and techno-economic analysis (TEA) should be integrated into all new technology development to ensure environmental and economic viability.

6.6. System-Level Optimization and Policy Integration

Future directions must also incorporate system-level optimization across treatment stages and scales. Municipal wastewater, stormwater, and industrial effluents each present distinct MP characteristics and treatment challenges. Research should evaluate treatment-train synergies and the cumulative removal efficiency across unit processes, rather than focusing on single technologies. Moreover, policy-driven research is essential to standardize testing methods, define permissible MP discharge limits, and incentivize adoption of high-efficiency, low-impact technologies. Collaboration between academia, utilities, and regulatory bodies will be crucial for scaling innovations from laboratory to full-scale operations.

6.7. Toward a Circular and Sustainable Framework

Ultimately, the future of MP removal must align with broader sustainability goals. Innovations should support a closed-loop approach that minimizes energy input, avoids secondary pollution, and promotes the recovery or transformation of polymeric residues into new materials or energy sources. Integrating MP treatment into wastewater resource recovery facilities (WRRFs), where water, energy, and nutrients are jointly recovered, thus further enhancing environmental performance. The convergence of advanced materials science, environmental biotechnology, and digital process control holds the potential to transform MP management from reactive mitigation into proactive, sustainable stewardship of aquatic environments.

7. Conclusions

Microplastics (MPs) have emerged as persistent and complex contaminants in aquatic environments, demanding integrated and efficient removal strategies. This review compared the latest physical, chemical, and biological technologies for MP mitigation across diverse water matrices. Among these, membrane-based filtration and coagulation–flocculation systems remain the most mature and scalable, achieving >90% removal under optimized conditions, though membrane processes can demand 0.8–2 kWh/m3 of energy. Adsorption using engineered biochars and magnetic composites provides a low-cost, sustainable approach with reported removal efficiencies of 80–95% but faces challenges in regeneration and selectivity. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) show promise in degrading MPs but pose risks of nanoplastic formation and high energy demand, often exceeding 3–5 kWh/m3. Biological and enzymatic degradation represents an emerging frontier, offering true mineralization potential but limited by slow kinetics and operational control.

Overall, hybrid systems (e.g., coagulation–membrane and adsorption–membrane combinations) stand out as front runners, leveraging synergistic effects to enhance capture efficiency and system longevity while reducing fouling and byproduct formation. Future research should focus on scaling these integrated processes, improving energy efficiency, and developing environmentally sustainable materials that minimize secondary pollution. A unified framework combining advanced treatment, monitoring, and life-cycle assessment will be critical to advancing real-world microplastic management toward circular and resilient water systems.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AOP | Advanced oxidation process |

| EPS | Extracellular polymeric substance(s) |

| FO | Forward osmosis |

| GAC | Granular activated carbon |

| HOC | Hydrophobic organic contaminant |

| MBR | membrane bioreactor |

| MF | Microfiltration |

| MP | Microplastic |

| NF | Nanofiltration |

| NOM | Natural organic matter |

| PA | Polyamide |

| PAC | Poly-aluminum chloride |

| PAH | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon |

| PAM | Polyacrylamide |

| PAN | Polyacrylonitrile |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PEST | Polyester |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| PVC | Polyvinyl chloride |

| RO | Reverse osmosis |