Abstract

In this study, we investigate the catalytic degradation of polystyrene (PS) in water at low temperature (90–110 °C, 1 atm) using a multiphase carbide–alloy catalyst obtained by mechanosynthesis. X-ray diffraction and scanning electron microscopy confirm a mixture of Mo–W carbides and Fe/Ni alloys, consistent with multiple types of active sites. High-resolution mass spectrometry (MS) is used to assign products by oligomer-series spacing (styrene repeat mass, 104.15 Da) and the residual mass for end-group identification. At 90 °C without catalyst, the spectrum shows PS fragments between –4618, consistent with thermal depolymerization. With catalyst at 90 °C, new lower- peaks emerge and long-chain signals diminish, indicating enhanced chain scission under mild conditions. Increasing the temperature to 100 and 110 °C yields even lighter ions (e.g., and 247.88), confirming stronger cracking and a larger number of distinct products. End groups inferred from include alkenes (C3–C7), alkanes (C4, C7), cyclic C6–C7 fragments, and alcohols, which are consistent with protolytic C–C bond cleavage (Haag–Dessau), oxidative dehydrogenation, and subsequent hydrogenation/hydration on metal/carbide sites. Overall, the results show that water-activated carbide–alloy catalysts can drive PS deconstruction at low temperature, shifting products toward shorter chains with useful functional groups, while a simple MS-based rule set provides a transparent and reproducible approach to product assignment.

1. Introduction

Plastic waste has become a major environmental issue because it is produced in large amounts and degrades very slowly in natural environments [1,2]. Throughout the twentieth century, the rapid development of the hydrocarbon industry was followed by a parallel growth of the plastics industry, which enabled technological advances through a wide variety of polymer types and applications. Today, large quantities of new plastics are produced daily and are found virtually everywhere on the planet, while global production continues to increase and generates massive amounts of mismanaged waste [1,2]. Polystyrene (PS) is a widely used commodity polymer in electrical and packaging applications, and it represents a substantial fraction of plastic debris in the environment [3]. From both ecological and economic perspectives, recovering and converting PS waste is a practical route to improve end-of-life management.

As plastic demand has not slowed down, it is expected that the associated waste problem will continue to grow. This makes it urgent to develop sustainable routes for plastic degradation and recycling. Ideally, such routes should (1) use the smallest possible amounts of auxiliary organic or inorganic materials, to avoid shifting the problem to new waste streams; (2) operate at relatively low energy input (especially low temperature), in order to reduce the overall environmental footprint and greenhouse-gas emissions; and (3) be simple enough to envision decentralized devices that could treat plastic waste near its point of generation, rather than allowing it to accumulate in the environment [1,2]. At the same time, many authors emphasize that understanding the underlying degradation mechanisms is essential to improve existing processes and to design catalytic systems that maximize conversion while minimizing secondary residues and enabling valorization of the products [1,2,3].

A broad range of physical, chemical, and biological methods has been explored for plastic degradation and conversion [1,2]. Among thermochemical routes, pyrolysis, liquefaction, gasification, and catalytic degradation have been widely studied as ways to transform plastic waste into fuels and chemicals [4,5,6]. Thermal degradation studies have examined the effect of temperature on product optimization and degradation mechanisms for mixed plastic streams [4], while liquefaction in supercritical water has been used to convert polyolefins such as polypropylene into oils [5]. Gasification of municipal solid waste has also been proposed as a route to energy recovery [6].

For PS and related polymers, catalytic routes often provide higher selectivity toward valuable products such as styrene. Early work showed that BaO converts PS to styrene at 400 °C [7]. Transition-metal catalysts tested under H2 or N2 at 375–400 °C also achieve high styrene yields, with Fe-based systems performing especially well [8]. HUSY zeolites (the proton form of ultra-stable Y; FAU aluminosilicate with strong Brønsted acidity and a high Si/Al ratio) in semi-batch reactors at 400–450 °C have been reported to give high selectivity to aromatic liquids and styrene yields above 50% [9]. More broadly, catalytic and thermal depolymerization studies on post-consumer polyethylene and other polyolefins confirm that most such processes operate at several hundred degrees Celsius, often above 300 °C, and frequently require controlled gas atmospheres and, in some cases, elevated pressures [7,9,10,11]. In addition, PS is known to be relatively stable and resistant to degradation, and many processes convert it into other intermediates and subproducts through multi-step, high-temperature reaction networks rather than direct low-temperature depolymerization [3,8].

Transition-metal carbides (TMCs) are attractive in hydrocarbon processing because they can display noble-metal-like catalytic behavior at lower cost [12]. Carbides such as WC, NiC, and MoWC have been used to reduce the viscosity of extra-heavy crude oils under aquathermolysis conditions [13,14]. In our previous work, an unsupported NiWMoC nanocatalyst produced by mechanical alloying was shown to be highly effective in the aquathermolysis of heavy oil at relatively low temperature and atmospheric pressure, significantly reducing the oil viscosity [13]. During those studies, we observed that the NiWMoC-based powders aggressively attacked plastic surfaces in contact with the catalyst; even plastic storage containers were perforated, and this effect was enhanced when Fe contamination from the milling media was present. These observations motivated us to examine a related Mo–W–Fe–Ni carbide–alloy system (with graphite) as a potential catalyst for PS degradation in hot water.

Traditionally, TMCs are obtained by carburization at high temperature and/or pressure [15,16]. Mechanical alloying has emerged as a lower-cost, solid-state route that affords good control over composition and microstructure, and yields nanostructured carbides and alloys with a high density of crystal defects that can act as active sites [14,17]. In the W–Mo–Ni–C system, mechanical alloying produces multiphase materials containing MoWC, Fe- and Ni-rich alloys, and iron carbides, which together form a heterogeneous catalytic network [14,17]. Unsupported, mechanically alloyed carbides/alloys thus offer a simple, solvent-free preparation method without additional supports or waste streams, while providing highly defective, nanostructured phases that are promising for hydrotreatment reactions [13,14].

Hydrotreating strategies for plastic degradation have also been explored using various nanocatalysts. Many studies rely on oxides (e.g., TiO2, ZnO, Ni- or Fe-based oxides) or rare-earth oxides, sometimes combined with photo- or electrochemical activation, and often operated at high temperatures and controlled atmospheres [7,8,9,10,11]. Carbon nanomaterials such as nanotubes have also been proposed as catalytic or photocatalytic supports for plastic conversion. However, these systems can be relatively costly or involve multi-step syntheses and additional supports. In contrast, the mechanically alloyed Mo–W–Fe–Ni carbide–alloy powders studied here are prepared in a single solid-state step, without solvents or supports, and their composition builds directly on previous heavy-oil hydrotreatment work [13,14].

In this study, we investigate a mechanosynthesized Mo–W–Fe–Ni carbide–alloy heterogeneous catalyst, operated in hot water/steam, to promote catalytic hydrotreatment of PS at low temperature (90–110 °C) and atmospheric pressure. Our objectives are to (1) demonstrate PS degradation under these mild, water-based conditions; (2) identify the main reaction products and end groups by mass spectrometry using an oligomer-series/end-group analysis [18,19,20]; and (3) propose the dominant reaction pathways consistent with the observed product distribution. We first establish the catalyst structure by X-ray diffraction and scanning electron microscopy, then quantify product families and end groups by mass spectrometry, and finally examine the temperature effect within the 90–110 °C window.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Elemental powders were used as precursors for mechanosynthesis: molybdenum (Mo, 1–5 m, 99.9% purity) and tungsten (W, 0.6–1 m, 99.9%) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); nickel (Ni, 3 m, 99.9%) and purified iron (Fe, 3–4 m, 97%) from Fermont (Monterrey, Mexico); and spectroscopic-grade graphite (SP-1-C, 3 m, 99%) from Union Carbide (Danbury, CT, USA). The powders were weighed to a target mass composition of 30 wt% Mo, 10 wt% W, 10 wt% Ni, 10 wt% Fe, and 40 wt% C.

Powder blending and milling were performed in a cylindrical stainless-steel vial with stainless-steel balls of 6 and 9 mm in diameter, using a ball-to-powder mass ratio (BPR) of 10:1. All loading operations were carried out inside an Ar-filled glovebox (99.999% Ar; and ppm). The mixture was processed in a SPARTAN low-energy vibratory mill for 250 h.

2.2. Microstructural Characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was conducted on a Bruker D8 diffractometer using Mo K radiation ( Å) over a range of 10–60° at a scan rate of 2° min−1. Phase identification was performed with the ICDD PDF-2 database (2003; International Centre for Diffraction Data, Newtown Square, PA, USA) and MatVis 2.0 software (2000; MatVis; McGraw–Hill, New York, NY, USA). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were acquired on a JEOL JSM-6701F operated at 5 kV with a probe current of 20 nA and a working distance of 12.2 mm, at nominal magnifications of and .

2.3. Catalytic Degradation

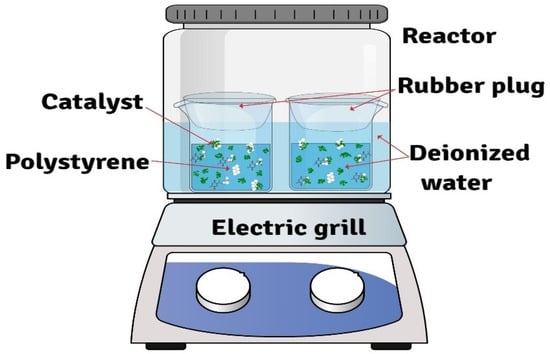

Catalytic degradation of polystyrene (PS) was carried out in a water–steam bath using a batch reactor. The sample was placed in a pewter well inside the reactor, loading 200 mg of PS, 20 mg of catalyst, and 30 mL of deionized water. The reactor was heated on an electric hot plate at set temperatures of 90, 100, and 110 °C for 24 h in separate experiments, as shown in Figure 1. The reaction time of 24 h was selected as a fixed reaction time long enough to achieve a clearly measurable extent of PS degradation and to generate sufficiently rich mass spectra for end-group analysis under these very mild conditions. We do not claim that thermodynamic equilibrium is reached; instead, the 24 h experiments are intended as representative snapshots that allow us to compare the blank and catalytic runs and to analyze the effect of temperature within the 90–110 °C window.

Figure 1.

Experimental arrangement for the catalytic degradation of polystyrene (PS): batch reactor with a pewter well containing 200 mg PS and 20 mg catalyst, immersed in 30 mL deionized water and heated on an electric hot plate to 90–110 °C for 24 h.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. X-Ray Diffraction

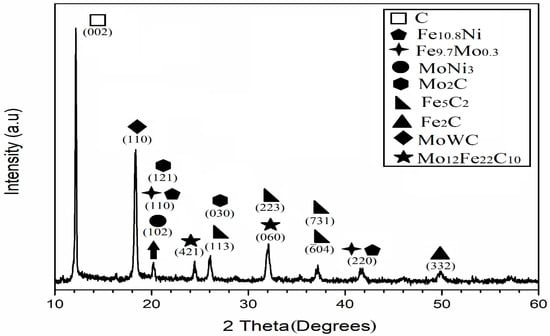

Figure 2 shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the heterogeneous catalyst after 250 h of mechanical processing. The diffractogram indicates a multiphase material made of carbides and metallic alloys. Reflections can be indexed to -Mo2C, Fe5C2, Fe2C, Mo12Fe22C10, MoWC, Fe9.7Mo0.3, Fe10.8Ni, and MoNi3. The coexistence of these constituents is typical of nonequilibrium routes such as mechanical alloying and results from solid-state reactions among Mo, W, Fe, Ni, and C together with interstitial diffusion of carbon into the metal lattices during microstructural evolution [17].

Figure 2.

X-ray diffraction pattern of the milled catalyst after 250 h of mechanosynthesis (Mo K, Å).

Using relative peak-area estimates (semi-quantitative), the largest contributions are graphite (∼40%; at ) and the bimetallic carbide MoWC (∼21%; at ). Phases present in notable proportions include Fe5C2 (∼12%; ) and Mo12Fe22C10 (∼9%; at ). These values are intended as qualitative/semi-quantitative indicators rather than absolute phase fractions and are consistent with heterogeneous catalytic behavior under the mild hydrotreatment conditions considered here.

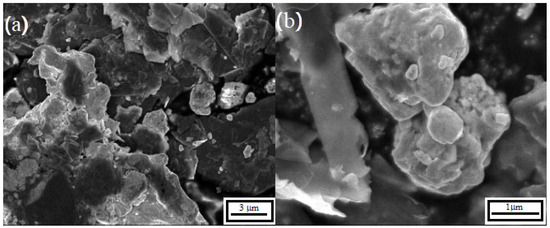

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

Figure 3 shows the characteristic morphology of the transition metal carbides and alloys at two magnifications: (a) (5 Kx) and (b) (20 Kx). In Figure 3a the field contains a heterogeneous network of irregular gray agglomerates attributed to transition metal alloys (Fe9.7Mo0.3, Fe10.8Ni, MoNi3), consistent with the phases identified by X ray diffraction in Section 3.1. These agglomerates are interspersed with dark graphite lamellae and lighter carbide lamellae, with typical lateral sizes larger than 1 m. Submicrometer agglomerates are also dispersed throughout the catalyst.

Figure 3.

Scanning electron micrographs of the catalyst after 250 h of synthesis: (a) 5 Kx and (b) 20 Kx.

Near the upper center of Figure 3a the lamellar morphology characteristic of MoWC is visible, forming stacks between alloy agglomerates and graphite lamellae, consistent with carbon diffusion during mechanical processing. Figure 3b shows a magnified view of the edge of a MoWC lamella together with a neighboring transition metal alloy particle, which together constitute the observed agglomerates. The contrast-based assignment of features is supported by the multiphase composition determined by X ray diffraction.

From a stability standpoint, the XRD and SEM data reported here correspond to the as-milled catalyst prior to its use in the aqueous degradation experiments. Given the mild reaction conditions employed in this work (90–110 °C, 24 h, water/steam at atmospheric pressure), no pronounced sintering or phase transformation is expected compared with the as-prepared state. This expectation is consistent with previous studies on related mechanically alloyed NiWMoC systems used for heavy-oil aquathermolysis at comparable or harsher conditions, where no drastic structural degradation was observed within similar timescales. Nevertheless, a systematic post-reaction characterization (XRD and SEM of spent catalysts after multiple cycles) will be required to directly confirm the long-term survival of the different carbide and alloy phases and to evaluate catalyst recyclability; this lies beyond the scope of the present study and will be the subject of future work.

3.3. Mass Spectrometry

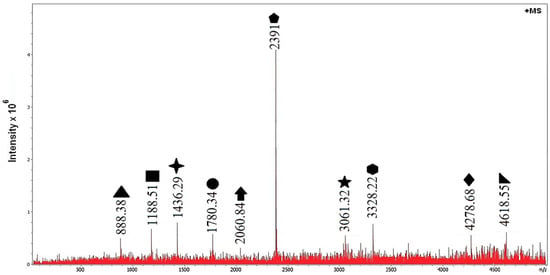

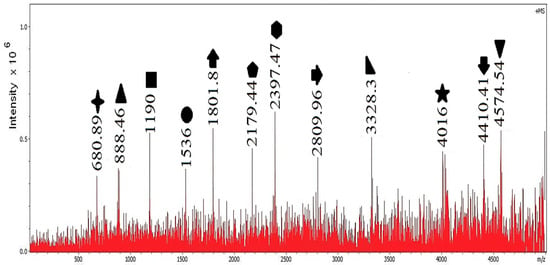

Mass spectrometry is a simple, direct, and low-cost way to characterize polymeric materials. We first analyze the products formed in water at 90 °C without catalyst (blank) and then compare them with those obtained in the catalytic run. As a reference, Royo and Brintzinger reported number-average molecular masses for polystyrene of – Da [18]. Figure 4 shows the mass spectrum for polystyrene degraded in water at 90 °C without catalyst.

Figure 4.

Mass spectrum of polystyrene degradation in water at 90 °C without catalyst (blank).

In the blank experiment, peaks spanning correspond to fragments of the original chain. This implies that chains present before degradation have , consistent with the reported range [18]. In polymer mass spectrometry, spectra typically show oligomer series separated by the monomer mass, and the series offset reveals the end group [19]. In our spectra the ions are predominantly singly charged (), so is numerically equal to the ion mass in daltons (Da). Accordingly, we take the styrene repeat mass as Da and report in Da.

To assign each peak, we model polystyrene as a chain of styrene repeat units, , with mass Da. Following the standard oligomer-series analysis [20], for a measured peak we calculate:

Here is the chain fragment, and is interpreted as the mass of a single end group (as reported for PS degradation [8] and routinely used in polymer MS [19]). When we name the end group as a neutral molecule (e.g., butene, C4H8), the attached group that contributes to mass is its radical form (e.g., C4H7) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Products of polystyrene degradation in water at 90 °C without catalyst (blank). Da. We use to propose a single end group.

Example 1.

For :

This is consistent with a C4 end group: neutral butene (C4H8); the attached group is C4H7.

This pattern matches thermal radical depolymerization in water at 90 °C (non-catalyzed) [21], giving chain fragments that carry alkane, alkene, or cyclic end groups.

Figure 5 shows the experiment at 90 °C with the catalyst. New peaks appear at lower (e.g., 680.89, 1536.00, 2809.96, 4016.00), and the intensity around (a major product in the blank) decreases. Both effects indicate more extensive chain scission at low temperature when the catalyst is present.

Figure 5.

Mass spectrum of polystyrene degradation in water at 90 °C in the presence of the catalyst.

Using Equations (1)–(3), Table 2 lists the assigned chain length n, the residual mass , and a consistent single end-group candidate for each peak. We report the neutral molecule name; the attached group that contributes to mass is its radical form.

Table 2.

Products of polystyrene degradation in water at 90 °C with catalyst. End-group candidates are chosen to match within typical MS tolerance.

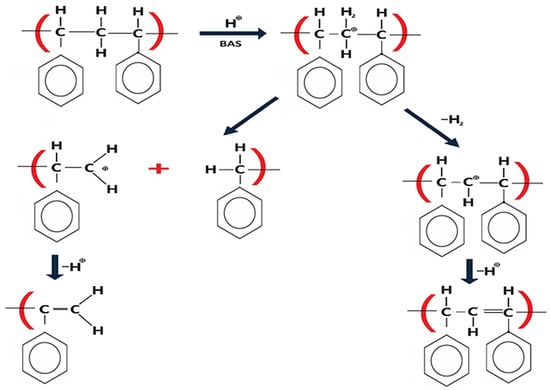

Overall, the catalyst shifts the distribution toward shorter chains and introduces end groups that include alkenes (C3–C7), alkanes (C4, C7), cyclic C6–C7 fragments, and alcohols such as CH3OH- and C6H14O-terminated chains. NiMo- and NiW-based systems are widely used in hydrotreating to improve petroleum streams by controlling S, N, and O through hydrodesulfurization (HDS), hydrodenitrogenation (HDN), and hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) [22,23]. In our end-group analysis we do not consider N-containing groups. In acid-catalyzed plastic cracking, solid acids can drive the Haag–Dessau protolytic scission: protonation of a double bond forms a carbocation, followed by C–C bond cleavage to give smaller alkenes [11,21]. In addition, oxidative dehydrogenation can form alkenes and H2 [23]. For our heterogeneous catalyst, transition-metal carbides and alloys of Mo, W, and Fe act as the active phases, while Ni alloys act as promoters [22,24]. The local H2 formed (and H adsorbed on the surface) can hydrogenate end groups [25,26], which helps explain the alkane-terminated fragments, and Ni is known to enhance hydrogenation [27]. In the presence of water, alkenes produced via these routes can undergo further hydrogenation and (tentative) hydration on metal/carbide sites, which offers a mechanistically consistent explanation for the alcohol end groups inferred from , although this hydration step is proposed rather than directly demonstrated here (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Proposed reaction pathways during catalytic PS degradation at 90 °C: (a) acid-catalyzed protolytic C–C scission (Haag–Dessau) to smaller alkenes; (b) oxidative dehydrogenation producing alkenes and H2; (c) surface hydrogenation of unsaturated end groups and hydration of alkenes to alcohols on metal/carbide sites (Mo, W, Fe) with Ni as promoter.

Temperature Effect

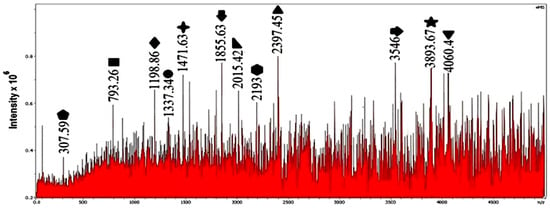

In this work, catalytic degradation experiments were performed at three temperatures in water, namely 90, 100, and 110 °C; no higher temperatures were explored. Figure 7 shows the mass spectrum for the catalytic degradation of polystyrene at 100 °C. Compared with 90 °C, the overall intensity distribution is shifted toward lower values and a new low- peak appears at , which is absent at 90 °C. Using Equations (1)–(3) with Da, this peak can be written as

Figure 7.

Mass spectrum of polystyrene degradation in water at 100 °C with catalyst.

Thus, it corresponds to a very short chain consisting of two styrene repeat units, , that carries a single end group with Da. This residual mass matches the C7H15 radical derived from neutral n-heptane (C7H16), and we therefore assign the ion as –C7H15. The appearance of this peak shows that at 100 °C the catalyst not only promotes extensive C–C bond scission (down to two styrene units) but also hydrogenates the terminal fragment to a saturated C7 segment, consistent with the hydrotreating behavior discussed above (Table 3).

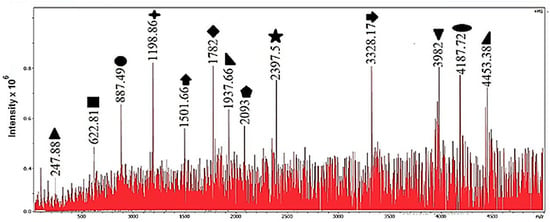

Figure 8 and Table 4 summarize the experiment at 110 °C. In addition to a broader set of fragments, an even lighter assignment appears at , which corresponds to with a cyclopropenyl end group (C3H3). Overall, raising the temperature from 100 to 110 °C increases the extent of cracking and the number of distinct products. From a mechanistic standpoint, increasing the temperature provides additional thermal energy to the polymer chains and radicals, so that a larger fraction of macroradicals can overcome the activation barrier for main-chain -scission and related rearrangements. As a consequence, each primary chain radical can undergo more successive scission events before termination, which shifts the product slate toward shorter oligomers and light fragments and generates a broader variety of end groups, as observed when comparing Figure 7 and Figure 8. This temperature-dependent move to lighter products and a wider product distribution is consistent with reports on thermal and catalytic cracking of polystyrene and other polyolefins, where higher cracking temperatures increase the yields of low-boiling liquids and gases at the expense of heavy waxes and long-chain residues [8,10,11,21]. In our low-temperature, water-based system, the same qualitative behavior is observed within the 100–110 °C window, with all reactions promoted by the Mo–W–Fe–Ni carbide–alloy catalyst.

Figure 8.

Mass spectrum of polystyrene degradation in water at 110 °C with catalyst.

Table 4.

Products of polystyrene catalytic degradation in water at 110 °C.

In order to provide a compact numerical description of these oligomer distributions, we also estimated approximate MS-based number- and weight-average degrees of polymerisation (DPn, DPw) and the corresponding apparent molar-mass averages (, ) by using the resolved series in the spectra and treating the normalised peak intensities as a semi-quantitative measure of relative abundance, following standard polymer mass-spectrometry procedures [28,29,30,31]. For each experiment we also report the dispersity (PDI = DPw/DPn) and the fraction of MS intensity associated with short oligomers (). The calculation procedure and the resulting values for the blank and the three catalytic runs are summarised in Table S1 of the Supplementary Information. As summarised in Table S1, all four experiments exhibit apparent values in the 2.0–2.5 kDa range and relatively narrow dispersities (PDI –1.37), while the fraction of MS intensity associated with short oligomers () increases from about 31–33% (blank and 90 °C) to ∼41% at 100 °C and remains higher than in the blank at 110 °C, consistent with more extensive chain scission and enrichment in short chains at higher temperature.

To make the location of alcohol end groups explicit, we point out several representative examples in the catalytic runs. At 90 °C with catalyst (Table 2), the ions at and 2809.96 are assigned to with a CH2OH end group (methanol-derived) and to with a C6H13O end group (hexanol-derived), respectively. At 100 °C (Table 3), oxygenated fragments such as –C3H7O (, propanol-type), –C5H11O (, pentanol-type), and –CH2OH (, methanol-type) are observed. At 110 °C (Table 4), the peaks at and 1937.66 correspond to –C6H13O (hexanol-type) and –C3H7O (isopropanol-type), respectively. These assignments highlight that alcohol-terminated chains are indeed present in the product mixtures and tend to become more abundant as the temperature increases within the 90–110 °C window.

Finally, we note that not all peaks listed in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 can be assigned unambiguously within the simple + single-end-group model adopted here. The entries marked with a dash in the Neutral name and Attached group columns are compatible with minor species that may carry two different end groups, correspond to ions that form adducts with water or alkali cations, or arise from less frequent fragmentation/recombination events during ionization. In addition, some of these signals may belong to overlapping oligomer series that cannot be uniquely deconvoluted within the mass accuracy of our instrument. These peaks are comparatively less intense and their chemical identity is not unique, so we do not attempt a detailed assignment and treat them as minor side products. Our mechanistic discussion therefore focuses on the dominant, well-resolved oligomer series and end groups, which capture the main trends in chain scission and functionalization; additional comments on these minor unassigned peaks are provided in Section S2 of the Supplementary Information.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Carbide-based Mo–W–Fe–Ni catalysts (including MoWC and related carbides/alloys) enable catalytic degradation of polystyrene in water at 90–110 °C, well below the >200 °C typically reported for conventional systems. The emergence of lighter chains and new low- peaks demonstrates catalytic activity under these mild, solvent-free conditions.

- (2)

- A simple end-group assignment method based on the styrene repeat mass ( Da) and the residual allows transparent determination of the chain length and a single end group for each detected ion. Because ions are predominantly singly charged, is numerically equal to the mass in daltons, which makes the analysis straightforward and reproducible.

- (3)

- The end groups inferred from include alkenes (C3–C7), alkanes (C4, C7), cyclic C6–C7 fragments, and alcohols (e.g., CH3OH, C6H14O). These products are consistent with acid-catalyzed protolytic C–C bond scission (Haag–Dessau), oxidative dehydrogenation that forms alkenes and H2, and subsequent surface hydrogenation and hydration of alkenes to alcohols on metal/carbide sites with Ni as promoter.

- (4)

- Temperature has a clear effect within the 90–110 °C window: increasing the temperature enhances main-chain scission and broadens the product distribution, leading to a higher fraction of short oligomers and light fragments. Practically, this behavior points to a low-temperature, water-based catalytic route for plastic deconstruction, in which the catalyst shifts the product slate toward shorter chains with functional end groups that could be leveraged in downstream upgrading.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr13123900/s1, Table S1: MS-based number- and weight-average degrees of polymerisation (DPn, DPw), apparent MS-based number- and weight-average molar masses (, ), dispersity (PDI), and fraction of MS intensity associated with short oligomers () for the blank and catalytic polystyrene degradation runs in water at 90, 100, and 110 °C.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.C.P., L.G.D.B.A. and J.N.R.O.; methodology, F.J.C.P., L.G.D.B.A., J.N.R.O. and I.C.-M.; software, Y.C.N. and F.J.C.P.; validation, F.J.C.P., I.C.-M. and J.N.R.O.; formal analysis, F.J.C.P. and J.N.R.O.; investigation, F.J.C.P., J.N.R.O. and Y.C.N.; resources, I.C.-M. and L.G.D.B.A.; data curation, Y.C.N. and F.J.C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, F.J.C.P. (lead) and J.N.R.O.; writing—review and editing, I.C.-M., L.G.D.B.A. and J.N.R.O.; visualization, F.J.C.P. and Y.C.N.; supervision, I.C.-M. and L.G.D.B.A.; project administration, I.C.-M.; funding acquisition, L.G.D.B.A. and I.C.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ESIQIE-IPN, Grant No. SIP-20250968 and TESI 14050.22-PD-2683.25-PD.

Data Availability Statement

All data and Supplementary Files supporting this work are openly available at Figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30674189 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the institutions SECIHTI, SNII, TESI and IPN for supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Niu, Y.; Pan, F.; Shen, K.; Yang, X.; Niu, S.; Xu, X.; Zhou, H.; Fu, Q.; Li, X. Status and Enhancement Techniques of Plastic Waste Degradation in the Environment: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Elsamahy, T.; Koutra, E.; Kornaros, M.; El-Sheekh, M.; Abdelkarim, E.A.; Zhu, D.; Sun, J. Degradation of conventional plastic wastes in the environment: A review on current status of knowledge and future perspectives of disposal. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 144719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valášková, M.; Madejová, J.; Inayat, A.; Matějová, L.; Ritz, M.; Leštinský, A.M.P. Vermiculites from Brazil and Palabora: Structural changes upon heat treatment and influence on the depolymerization of polystyrene. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 192, 105639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, R.; Ruj, B.; Sadhukhan, A.; Gupta, P. Thermal degradation of waste plastics under non-sweeping atmosphere: Part 1: Effect of temperature, product optimization, and degradation mechanism. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 239, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-T.; Jin, K.; Wang, N.-H.L. Use of supercritical water for the liquefaction of polypropylene into oil. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 3749–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qinglin, Z.; Liran, D.; Dikla, F.; Weihong, Y.; Wlodzmierz, B. Gasification of municipal solid waste in the Plasma Gasification Melting process. Appl. Energy 2012, 90, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukei, H.; Hirose, T.; Horikawa, S.; Takai, Y.; Taka, M.; Azuma, N.; Ueno, A. Catalytic degradation of polystyrene into styrene and a design of recyclable polystyrene with dispersed catalysts. Catal. Today 2000, 62, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijeñski, J.; Kaczorek, T. Catalytic degradation of polystyrene. Polimery 2005, 50, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tae, J.-W.; Jang, B.-S.; Park, K.-H.K.; Park, D.-W. Catalytic degradation of polystyrene using HUSY catalysts. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 2005, 84, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Liang, J.; Anderson, L.L. Thermal and catalytic degradation of high density polyethylene and commingled post-consumer plastic waste. Fuel Process. Technol. 1997, 51, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidhya, K.; Bryan, R.M.; Sriraam, R.C.; Nandakishore, R.; Sharma, B.K. Catalytic and thermal depolymerization of low value post-consumer high density polyethylene plastic. Energy 2016, 111, 884–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Marin-Flores, O.G.; Norton, M.G.; Ha, S. Molybdenum carbide supported nickel–molybdenum alloys for synthesis gas production via partial oxidation of surrogate biodiesel. J. Power Sources 2015, 294, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Olvera, J.N.; Gutiérrez, G.J.; Serrano, J.R.; Ovando, A.M.; Febles, V.G.; Díaz Barriga Arceo, L. Use of unsupported, mechanically alloyed NiWMoC nanocatalyst to reduce the viscosity of aquathermolysis reaction of heavy oil. Catal. Commun. 2014, 43, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Ruiz, M.; Rivera Olvera, J.; Morales Davila, R.; González Reyes, L.; Garibay Febles, V.; Garcia Martinez, J.; Díaz Barriga Arceo, L.G. Synthesis and characterization of mechanically alloyed, nanostructured cubic MoW carbide. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 9114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Ning, W.; Han, W.; Liu, H.; Huo, C. Preparation of iron carbides formed by iron oxalate carburization for Fischer–Tropsch synthesis. Catalysts 2019, 9, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneau, M.; Yaffe, D.; Liu, R.; Agwara, J.N.; Porosoff, M.D. Establishing tungsten carbides as active catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 16458–16466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plata, F.J.; Rivera Olvera, J.N.; Díaz Barriga, L.G. Thermodynamic analysis and microstructural evolution of the W–Mo–Ni–C system produced by mechanical alloying. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2022, 644, 414126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brintzinger, E.R.; Brintzinger, H.H. Mass spectrometry of polystyrene and polypropene ruthenium complexes: A new tool for polymer characterization. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002, 663, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jackson, A.T.; Jennings, K.R.; Scrivens, J.H. Generation of average mass values and end-group information of polymers by means of a combination of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry and liquid secondary ion-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1997, 8, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaudo, G.; Lattimer, R.P. Mass Spectrometry of Polymers; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Djinović, P.; Tomše, T.; Grdadolnik, J.; Božič, Š.; Erjavec, B.; Zabilskiy, M.; Pintar, A. Natural aluminosilicates for catalytic depolymerization of polyethylene to produce liquid fuel-grade hydrocarbons and low olefins. Catal. Today 2015, 258, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palafox, L.S. Importancia del estudio de catalizadores para la reducción de compuestos orgánicos de azufre en gasolinas y diésel. Pädi 2021, 8, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Bell, A.T. Catalytic Properties of Supported MoO3 Catalysts for Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Propane. In Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 136, pp. 507–512. Available online: http://iglesia.cchem.berkeley.edu/Publications/StudiesofSurfaceScienceandCatalysis_136_507_2001.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Corma, A.; Martínez, A. Zeolites in Refining and Petrochemistry. In Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 157, pp. 337–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergault, I.; Fouilloux, P.; Delmas, H. Kinetics and intraparticle diffusion modelling of a complex multistep reaction: Hydrogenation of acetophenone over a rhodium catalyst. J. Catal. 1998, 175, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicky, J.J.; Gut, G. Kinetics, poisoning and mass transfer effects in liquid-phase hydrogenations of phenolic compounds over a palladium catalyst. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1978, 33, 1363–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, L.G., Jr. Química Orgánica, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Mexico City, Mexico, 1993; ISBN 968880245X. [Google Scholar]

- Montaudo, G.; Scamporrino, E.; Vitalini, D.; Mineo, P. Novel procedure for molecular weight averages measurement of polydisperse polymers directly from MALDI-TOF mass spectra. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1996, 10, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shion, H.; Ellor, N. Polymer Analysis by MALDI-TOF MS. In Waters Application Note; Waters Corporation: Milford, MA, USA, 2007; Available online: https://www.waters.com/nextgen/us/en/library/application-notes/2007/polymer-analysis-by-maldi-tof-ms.html (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Wesdemiotis, C.; Williams-Pavlantos, K.N.; Keating, A.R.; McGee, A.S.; Bochenek, C. Mass spectrometry of polymers: A tutorial review. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2024, 43, 427–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, A.R.; Wesdemiotis, C. Rapid and simple determination of average molecular weight and composition of synthetic polymers via electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry and a Bayesian universal charge deconvolution. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2023, 37, e9478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).