Abstract

Thin films have become indispensable in shaping the landscape of modern and future technologies, offering versatile platforms where properties can be engineered at the atomic to microscale to deliver performance unattainable with bulk materials. Historically evolving from protective coatings and optical layers, the field has advanced into a highly interdisciplinary domain that underpins innovations in microelectronics, energy harvesting, optoelectronics, sensing, and biomedical devices. In this review, a structured approach has been adopted to consolidate the fundamentals of thin film growth and the governing principles of nucleation, surface dynamics, and interface interactions, followed by an in-depth comparison of deposition strategies such as physical vapor deposition, chemical vapor deposition, atomic layer deposition (ALD), and novel solution-based techniques, highlighting their scalability, precision, and application relevance. By critically evaluating experimental studies and technological implementations, this review identifies key findings linking microstructural evolution to device performance, while also addressing the pressing challenges of stability, degradation pathways, and reliability under operational stresses. The synthesis of evidence points to the transformative role of advanced deposition controls, in situ monitoring, and emerging AI-driven optimization in overcoming current bottlenecks. Ultimately, this work concludes that thin film technologies are poised to drive the next generation of sustainable, intelligent, and multifunctional devices, with emerging frontiers such as hybrid heterostructures, quantum materials, and bio-integrated systems charting the future roadmap.

1. Introduction

Thin films are solid layers with thickness ranging from a few nanometers to several micrometers deposited on a substrate, with their reduced dimensionality producing physical and chemical behaviors that can diverge markedly from bulk materials [1]. When one or more dimensions approach characteristic length scales such as the electron mean free path, exciton Bohr radius, or phonon mean free path, quantum confinement and interface-mediated phenomena control charge, heat, and mass transport [2]. The conventional operational regime for thin film science, therefore, spans from sub-monolayer coverages (atomic monolayers) up to micron-thick coatings, with the exact practical cutoff dependent on the property under study and the targeted application [3].

A defining characteristic of thin films is the surface-to-volume ratio: surfaces and buried interfaces dominate energetics, defect chemistry, and mechanical boundary conditions, producing growth pathways and steady-state structures that are set by interfacial free energies, epitaxial mismatch, and kinetic barriers rather than bulk thermodynamics alone [4]. When thickness is reduced to the nanometer scale, quantum-size effects—manifested as discrete subband formation, thickness-dependent bandgap shifts, and confinement-modified phonon spectra—become measurable and often determinative of optical and electronic performance [2]. Because of these combined surface and quantum effects, thin films commonly show electrical conductivity, optical constants (n and k), catalytic turnover rates, mechanical stiffness, and adhesion energies that differ substantially from their bulk counterparts, which compels the use of specialized, high-resolution characterization and multiscale modeling to establish reliable structure–property relations [5].

Historically, thin films have evolved from primitive protective and decorative coatings to enabling layers in the most advanced technologies, and contemporary examples include metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) gate dielectrics and diffusion barriers in microelectronics, antireflection and high-reflectance optical stacks, thin film photovoltaic absorbers and transparent conducting electrodes, as well as functional coatings for microelectromechanical systems (MEMS)/nanoelectromechanical systems (NEMS) and antimicrobial or anti-fouling surfaces. In energy and device engineering, thin films enable material-efficient architectures such as copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS), cadmium telluride (CdTe), and perovskite photovoltaics, conformal electrodes and thin solid electrolytes for batteries, and catalytically active nanometric coatings for electrochemical reactors [6]. Upscaling from laboratory demonstrations to industry-scale manufacturing depends on the chosen deposition family (physical vapor deposition (PVD), chemical vapor deposition (CVD), atomic layer deposition (ALD), pulsed laser deposition (PLD), or solution processing) and on the interplay between throughput, conformality, compositional precision, and environmental constraints [6]. Because a thin film’s functionality is set by its nanoscale structure, the discipline places heavy demands on a complementary set of characterization tools—from X-ray diffraction (XRD) and grazing-incidence X-ray diffraction (GIXRD) to scanning electron microscopy (SEM)/transmission electron microscopy (TEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), spectroscopic ellipsometry, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)/time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS), and in situ probes (reflection high-energy electron diffraction (RHEED), quartz crystal microbalance (QCM), substrate-curvature)—and data fusion strategies that combine imaging, spectroscopy, and electrical/optical testing [7].

Despite the breadth of the related literature, critical scientific and engineering challenges remain: controlling nucleation and early-stage growth to achieve desired texture and defect density across wafer-scale areas; understanding how deposition energy, flux, and chemical potential set microstructural evolution; and quantifying the origins and evolution of residual and growth stresses that impact device yield and lifetime [8]. Reliability and lifetime testing of thin film stacks—including thermal cycling, stress-induced delamination, ion-migration, and humidity-accelerated degradation—are unevenly reported across the literature, producing an urgent need for standardized test protocols and datasets that link process windows to long-term failure modes [4]. Environmental sustainability, embodied by the push for lower-temperature, lower-waste deposition chemistries and for recyclable materials/processes, is increasingly driving the choice of deposition strategy and materials engineering, yet methodical life-cycle analyses and green-manufacturing roadmaps for thin film production are still fragmentary [1]. The multidisciplinary interface between physics, chemistry, and manufacturing engineering—which is required to translate nanoscale understanding into robust industrial processes—therefore remains an active bottleneck in the commercial adoption of advanced thin films [3].

A survey of recent reviews shows a pattern of depth over breadth: there exist detailed, high-quality reviews devoted to individual method families (for example, ALD, pulsed laser deposition (PLD), and sputter-based physical vapor deposition (PVD)) or to specific application classes (transparent conductors, photovoltaic absorbers, magnetic thin films), yet there are relatively few integrative treatments that formally map nucleation/growth fundamentals to practical deposition windows, characterization workflows and industrial reliability metrics in a single, engineer-oriented framework [1]. This fragmentation leaves practitioners who must optimize across multiple constraints—e.g., conformality versus throughput, stress control versus deposition rate, or environmental footprint versus film quality—without an accessible, cross-referenced set of design rules and validated process templates [9]. Consequently, the literature contains disparate islands of knowledge (fundamentals, method optimization, metrology, and application case studies) that we argue would benefit strongly from systematic synthesis and machine-readable consolidation [4].

The novelty of the present review is therefore twofold: first, we construct a consolidated conceptual framework that links nucleation thermodynamics and kinetics to deposition parameters across the major tool families (Physical vapor deposition (PVD), Chemical vapor deposition (CVD)/Metal–organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD), ALD, pulsed layer deposition (PLD) and solution processing), and second, we map the resulting microstructures onto targeted characterization pathways and quantitative reliability metrics that are directly actionable for process engineers and device designers [4]. To achieve this we compile extensive, curated tables that unify nucleation parameters (e.g., critical nucleus size, adatom diffusion lengths, sticking coefficients), canonical growth modes (Volmer–Weber, Frank–van der Merwe, Stranski–Krastanov) and practical deposition windows (flux, substrate temperature, background pressure, energy per arriving species), thereby providing a searchable resource that is absent from most prior single-topic reviews [3]. Finally, we explicitly relate microstructural descriptors to industrial constraints—scalability, reproducibility, environmental impact, and in-service reliability—and point to AI/ML approaches for rapid optimization of multidimensional process parameter spaces as an emerging route to accelerate translation [1].

The scope and limitations are stated up front so the reader can interpret tables and recommendations correctly: the review emphasizes inorganic thin films (metals, oxides, nitrides, and chalcogenides) and their vacuum- and vapor-phase deposition variants, while polymeric organic and purely biological coatings are treated only when deposition physics or reliability considerations are directly analogous [9]. We cover the dominant process families—PVD (magnetron sputtering, evaporation, and PLD), CVD/MOCVD, ALD (including spatial and plasma-enhanced variants), and representative solution processing methods—and explicitly separate laboratory-scale procedures from wafer-scale, roll-to-roll, and High-Performance Coating (HPC) manufacturing constraints when providing process windows [1]. Limitations include the fact that per-material, long-term reliability datasets are heterogeneous in reporting standards and frequency; therefore, while we synthesize the best-available failure mode correlations, we do not claim to present a definitive industrial dataset. Instead, we provide standardized metric templates (stress, adhesion energy, T50 lifetime at specified stressors, activation energies for degradation) for the community to adopt and extend [4].

2. Historical Evolution

Thin films have a rich history that traces back to ancient civilizations, where artisans unknowingly utilized thin layers of materials for decorative and functional purposes, such as gold leaf applications in Egypt and Rome. The scientific foundation of thin film technology, however, began in the 17th century when Robert Boyle and later Michael Faraday explored optical phenomena in metal-coated glass, sparking interest in the correlation between film thickness and optical properties. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, thin films became integral to scientific instrumentation, particularly in optics, as advances in vacuum deposition methods allowed controlled preparation of metallic and dielectric coatings for mirrors, lenses, and scientific apparatus [10].

The modern era of thin films emerged during and after World War II, driven by the demands of electronics and materials science. Breakthroughs in vacuum evaporation, sputtering, and CVD enabled the precise fabrication of semiconductor devices, revolutionizing microelectronics and later nanotechnology. From the 1950s onward, thin films became central to the miniaturization of transistors and integrated circuits, leading to their dominance in fields such as optoelectronics, photovoltaics, superconductivity, and protective coatings. Today, thin films are at the core of cutting-edge research in flexible electronics, quantum devices, and energy harvesting, embodying a centuries-long evolution from decorative use to a cornerstone of advanced technology [11].

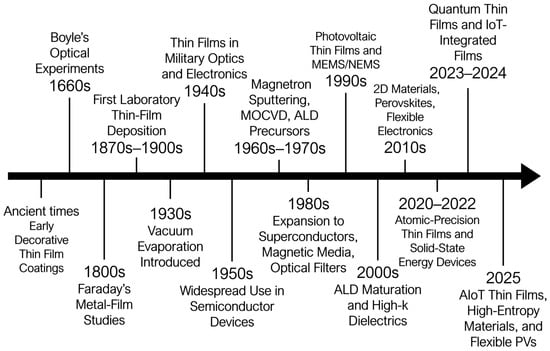

The evolutionary trajectory of thin film technology—from its early use in decorative coatings to its present role in advanced electronic, optoelectronic, and energy devices—is summarized in Figure 1. The timeline traces pivotal milestones, including the introduction of vacuum deposition in the 1930s, the development of chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and magnetron sputtering in the mid-20th century, and the subsequent expansion into semiconductor, photovoltaic, and flexible electronic applications. This progression underscores how thin films have transitioned from simple protective layers to essential functional materials in modern technology.

Figure 1.

Evolution of Thin Films.

3. Growth Fundamentals and Physics

3.1. Nucleation

In thin film growth, nucleation acts as a regulator of morphology because the density, spatial distribution, and early size distribution of nuclei formed during the onset of deposition governs the pathway to island coalescence, grain evolution, surface roughness, and ultimately intended functional properties of the film [3]. In general, the physicochemical state that promotes nucleation can be viewed as a competition between a thermodynamic driving force (chemical potential or supersaturation) that promotes the formation of a new phase and interfacial penalties that resist the formation of a new area and interface, such that formation is thermodynamically preferable only when clusters reach a critical compactness [12]. From an engineering perspective, this balance implies that the controllable process parameters—substrate temperature, vapor or flux rate, background pressure, and surface preparation—map directly to nucleation results, and subsequently map directly to device-relevant film performance metrics such as continuity, texture, and defect densities [13].

The hindrance, often indicated as ΔG*, represents the free-energy hill that a cluster must overcome before it can be a thermodynamically stable nucleus in classical definitions, which is dependent on both the supersaturation and the material specific surface energy and interfacial energy values; thereby, relatively small amounts of changes in deposition chemistry or substrate treatments can dramatically change nucleation rate and island density on relevant timescales for technology [14]. In practical terms, ΔG* appears as a kinetic sensitivity: high supersaturation or fast flux favors many small nuclei and rapid coalescence, while low supersaturation or increased surface mobility yields fewer, larger nuclei and smoother layer formation; this is why process engineers purposefully use ramped temperature or pulsed flux approaches to adjust early stages of microstructure without changing chemistry [3]. The classical, continuum view that produces a single ΔG* must be interpreted in concert with atomistic realities at surfaces, such as separate lattice sites, step edges, and fleeting adsorption states, as these affect local energetics and consequently lead to divergences from the simplest homogeneous predictions in actual deposition systems [15].

In thin film nucleation, the surface energy (γ) of the substrate and the depositing material significantly influences the value of ΔG* and the favored growth mode. Surface energy directly affects the wetting properties of the adatoms or clusters via the contact angle (θ), indicating how the deposited phase engages with the substrate surface [16]. When the substrate’s surface energy is significantly higher than that of the film, adatoms are inclined to disperse, leading to a reduced contact angle and a lower effective ΔG*, which promotes two-dimensional (layer-by-layer) or Frank–van der Merwe growth [17]. In contrast, if the film’s surface energy is greater than that of the substrate, inadequate wetting happens, marked by a significant contact angle and an increased nucleation barrier, favoring the three-dimensional island growth typical of Volmer–Weber morphology [18]. In intermediate scenarios, where partial wetting takes place, nucleation initiates as islands that later merge into continuous layers; this exemplifies the Stranski–Krastanov mode [19]. Consequently, the interaction among γ, θ, and ΔG* forms a physical connection between the thermodynamic driving force and the morphological development of the film. Modifying the substrate surface energy—via treatments, coatings, or interfacial engineering—can be an effective approach to influence nucleation energetics and manage the final growth mode without changing deposition chemistry [20].

The wetting angle, θ, is crucial in heterogeneous nucleation—the primary mechanism during thin film formation on solid substrates. It measures the extent of wetting between the deposited phase and the substrate, determined by the equilibrium of interfacial energies at the three-phase contact line, as outlined by Young’s equation:

where represents the substrate–vapor surface energy, denotes the substrate–film interfacial energy, and indicates the film–vapor surface energy. A reduced wetting angle signifies improved wetting and a lower ΔG* for nucleation, promoting two-dimensional (layer-by-layer) growth [21], whereas a larger wetting angle suggests poor wetting and an elevated ΔG*, resulting in three-dimensional (island) growth [3,22]. The physics of wetting behavior and contact angle provide a unified view of the thermodynamics of interfaces with macroscopic growth modes that are seen experimentally, such that the relative magnitudes of substrate–film, film–film, and substrate–film interfacial energies govern whether a film grows layer-by-layer, as three-dimensional islands, or as an initial wetting layer and then islands (Frank–van der Merwe, Volmer–Weber, and Stranski–Krastanov modes) and, if there is lattice mismatch, strain energetics will play a role in the processes [23]. From a materials engineering perspective, the wetting angle is not simply a geometric descriptor but a device to integrate chemical bonding, van der Waals dispersion interactions, elastic relaxation, and the local adsorption environment, and thus a useful design metric for tuning seed layer chemistries or adhesion layers to produce the targeted growth mode [13]. Additionally, intrusiveness or anisotropic surface energies can induce metastable wetting layers of finite thickness before three-dimensional islanding occurs which, in a heteroepitaxy framework, becomes the underlying origin of self-assembled quantum dot formation once elastic relaxation becomes energetically preferable past a critical thickness [24].

Within this framework, the nucleation energy barrier (ΔG*) is primarily determined by the interplay of the interfacial energies that characterize the wetting angle [25]. As ΔG* signifies the energy barrier that needs to be surpassed for a stable nucleus to develop, its value directly indicates the level of wetting: when the substrate’s surface energy is greater compared to the interfacial energy between the substrate and the film, the contact angle reduces, resulting in enhanced adhesion and a decreased ΔG*, which energetically promotes the creation of two-dimensional nuclei that extend over the surface [26]. On the other hand, if the interfacial energy between the substrate and film is high or the film–vapor surface energy prevails, the contact angle rises, signaling inadequate wetting and a higher ΔG*, thus promoting the formation of distinct three-dimensional clusters [27]. Consequently, by mediating the energy balance at interfaces, the wetting angle serves as a macroscopic signal of the microscopic energy dynamics that dictate nucleation. The relationship between γ, θ, and ΔG* offers a thermodynamic basis to explain how slight changes in surface treatments, surfactants, or substrate chemistry can significantly impact nucleation density and growth morphology, even when the deposition conditions remain the same [28].

Curvature-dependent thermodynamics—the Gibbs–Thomson effect—provides additional size dependence on the equilibrium chemical potential and consequently of the stability of nanoscale nuclei, with higher curvature (smaller radius) increasing the effective chemical potential and therefore depressing equilibrium condensation conditions relative to bulk; this provides the thermodynamic basis for phenomena like depressed melting temperatures, suppressed nucleation of very small clusters, and size-dependent solubility in confined geometries [29]. In thin film contexts, the Gibbs–Thomson contribution is fundamental to understanding Ostwald ripening and coarsening dynamics of an ensemble of islands because small islands are thermodynamically favored to dissolve and feed the larger islands unless kinetic barriers inhibit that exchange, thus putting diffusion length and adatom capture efficiencies front and center in scalable film engineering [30]. In terms of device manufacture, this indicates that nanoscale curvature effects manifest as practical constraints on allowable processing windows for features such as quantum dots, nanoparticles in a matrix, or ultrathin continuous films, and exploit surfactants, rapid quenching, or templated nucleation sites to stabilize small nuclei and alter the Gibbs–Thomson effect, promoting dissolution [14]. The Gibbs–Thomson effect presents an extra size-dependent thermodynamic factor by connecting the equilibrium chemical potential of a small particle or cluster to its curvature. This effect states that the equilibrium vapor pressure above a curved surface exceeds that above a flat surface because of the extra energy linked to surface curvature [31]. For a spherical nucleus with a radius r, the Gibbs–Thomson equation can be stated as:

where represents the change in chemical potential compared to the bulk, denotes the surface energy, and signifies the molar volume. In thin film nucleation, this implies that smaller nuclei necessitate greater supersaturation for stability due to their heightened curvature, raising their chemical potential. As a result, the Gibbs–Thomson effect establishes a minimum size for stable nuclei, thereby affecting both the rates of nucleation and the critical thickness required for stable film formation [32].

In general, heterogeneous nucleation on actual substrates will nearly always dominate over homogeneous nucleation, because surface defects, steps, impurities, and specifically designed seeding sites can lower the effective ΔG* by creating lower-energy interfaces or locally changing the wetting geometry. This means that engineers use the density, chemistry, and topography of nucleation sites as a primary way to change nucleation from a stochastic event to a reliable, reproducible step in a manufacturing process [33]. A variety of empirical and theoretical studies show that the density of nucleation sites is a non-linear function of surface energy variations and adatom mobility. This is why combined in situ diagnostics (for example, high-energy electron diffraction (RHEED), in-vacuo AFM/STM, or real-time optical probes) and kinetic models are essential tools in translating laboratory observations into meaningful process windows for production [34]. From an applied viewpoint, practical methods to guide nucleation consist of intentional surface functionalisation to adjust local contact angles, placement of topography-patterned nucleation arrays at the nanoscale to generate deterministic arrays of islands, and brief modulation of flux/temperature, such that desired adatom lifetimes and capture zones ultimately yield the desired nucleus density and uniformity [13].

Linking thermodynamic nucleation ideas with predictive engineering requires simultaneous quantification of kinetics (arrival flux, surface diffusion coefficients, desorption rates) and local energetics (interface energies, strain relief pathways, and chemical interactions with the substrate), since nucleation is a non-equilibrium multiscale process in thin films and only a combined thermo-kinetic description will yield robust process recipes for high-performance films and nanostructures [12]. In practical recommendations for researchers at the review level, we would advise focusing on (i) measuring or estimating interface energies accurately for the film/substrate pair, (ii) experimentally mapping nucleus density against flux and temperature to extract effective ΔG* trends of interest to the researcher, and (iii) systematically investigating wetting-modifying treatments, such as ultrathin adhesion layers or molecular surfactants, moving the growth mode in a desired way, while keeping the limitations of Gibbs–Thomson curvature for nanoscale stability in mind.

3.2. Growth Modes

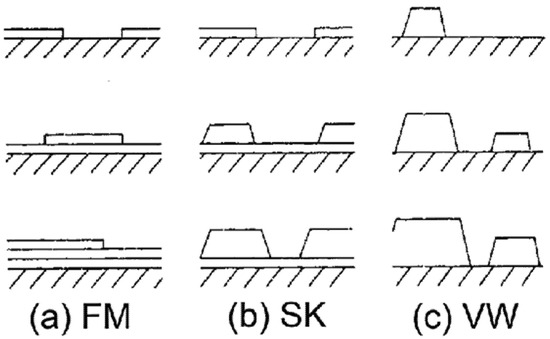

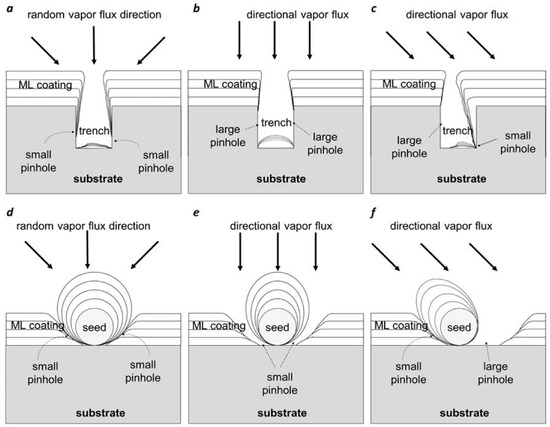

Thin film growth modes represent a compact taxonomy that connects interfacial thermodynamics and surface kinetics with the macroscopic morphology that develops during the deposition process. Understanding them is important as they set the initial route for grain structure, roughness evolution, and defect incorporation within functional films [3]. The traditional categorization of growth as either Volmer–Weber (island), Frank–van der Merwe (layer-by-layer), Stranski–Krastanov (layers + islands), and step flow growth is more than historical names; they capture the balance of energies between film–film, film–substrate, and the substrate surface energies with strain and kinetic limits [35]. When it comes to applied practice, this taxonomy takes on a practical design ability in that changing substrate chemistry, temperature, flux, or surfactant additions could shift a system from one regime to another and thereby tune electronic, optical, or mechanical performance without changing bulk composition [36]. The morphological evolution of epitaxial thin films is fundamentally determined by the balance between the surface and interfacial free energies of the film–substrate system. Depending on these competing energetics, adatom–substrate and adatom–adatom interactions lead to distinct growth regimes that dictate whether the film develops in two dimensions or transitions into three-dimensional island structures. As illustrated in Figure 2, epitaxial growth can proceed through the Frank–van der Merwe (FM), Stranski–Krastanov (SK), or Volmer–Weber (VW) modes.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the three principal epitaxial thin film growth modes as a function of monolayer (ML) surface coverage (θ): (a) Frank–van der Merwe (FM) layer-by-layer growth, (b) Stranski–Krastanov (SK) layer-plus-island growth, and (c) Volmer–Weber (VW) island growth. The diagrams illustrate how the balance between adatom–substrate and adatom–adatom interactions governs the transition from two-dimensional layer formation to three-dimensional islanding. FM growth occurs when the film wets the substrate completely (γ_substrate > γ_film + γ_interface); VW growth arises when adatom cohesion dominates (γ_substrate < γ_film + γ_interface); and SK growth represents an intermediate regime where strain energy accumulation beyond a critical thickness drives island formation [3,37].

In FM growth, the interfacial bonding between the film and the substrate is energetically favorable, resulting in complete wetting and sequential monolayer formation. This mode minimizes surface free energy and yields atomically smooth films, often observed in systems with minimal lattice mismatch. In contrast, the VW mode emerges when cohesive forces between adatoms outweigh their adhesion to the substrate, producing isolated three-dimensional nuclei from the onset of deposition. Such island growth reflects a condition where the substrate surface energy (γ_substrate) is smaller than the sum of the film and interface energies (γ_film + γ_interface), favoring the clustering of adatoms into discrete islands.

The SK growth mode represents an intermediate mechanism, initiating as layer-by-layer deposition but transitioning to island formation once the strain energy—accumulated due to lattice mismatch—surpasses a critical threshold. This strain-driven instability causes the film to relax via the nucleation of three-dimensional islands atop a wetting layer, thus bridging the FM and VW regimes. The framework depicted in Figure 2, therefore, encapsulates the energetic and strain-mediated principles governing epitaxial growth and serves as a foundational reference for interpreting morphological transitions in strained film systems.

3.2.1. Volmer–Weber Growth Mode

Initially, the Volmer–Weber growth mechanism is distinguished by the formation and evolution of three-dimensional islands, as adatom–adatom interactions dominate over adatom–substrate interactions to produce discrete islands, whose density and size distribution depend strongly on the level of supersaturation and surface diffusion lengths [38]. At the microscopic level, this mode causes high initial roughness, island coalescence that occurs in isolation, and a complex evolution of stresses during coarsening. This has been observed for metals on insulating substrates and for weakly wetting adsorbates [39]. From a kinetic engineering approach, we can modulate Volmer–Weber films by varying flux and substrate mobility such that island nucleation density can be controlled—high flux and low surface mobility produce many small islands, and higher mobility and lower flux lead to large, widely spaced islands and different coalescence pathways [38]. Consequently, the wetting angle is significant, and the thermodynamic impetus encourages aggregation over spreading. The balance of interfacial energy can be expressed as:

where represents the substrate–vapor energy, denotes the substrate–film energy, and indicates the film–vapor surface energy. The inequality signifies partial wetting, resulting in three-dimensional nuclei. This growth mode frequently occurs in systems characterized by substantial lattice mismatch or chemical incompatibility, like metal films (Au, Ag, Pt) on oxide substrates. Volmer–Weber growth often leads to uneven surfaces, polycrystalline microstructures, and a high concentration of grain boundaries, which can be beneficial for catalytic uses but harmful to electronic or optical applications that require smooth films [23].

3.2.2. Frank–van der Merwe Growth Mode

Layer-by-layer growth, known as Frank–van-der-Merwe (FM) growth, yields atomically flat and continuous layers when the substrate–adatom binding is greater than the adatom–adatom binding, and this growth is the thermodynamic ideal for having sharp interfaces and low roughness in heterostructures and devices [40]. The physical signature of this mode is the completion of each monolayer before the next one starts, which requires sufficient adatom mobility to find low-energy sites and a wetting function that is positive, or, to the detriment of the film formation, the creation of new substrate–film interface is energetically encouraged compared to the creation of interfaces between films [35]. Practically, persistent Frank–van der Merwe (FM) growth is exploited in oxide superlattices, semiconductor heterostructures, and other systems where abrupt interfaces and two-dimensional confinement are necessary for the intended functionality [40]. This happens when the interaction between the adatom and the substrate is more intense than the adatom–adatom interaction, fulfilling the requirement:

In this case, the surface free energy of the uncoated substrate decreases during film formation, rendering layer completion energetically advantageous before the nucleation of the subsequent layer. This type of growth occurs in systems characterized by minimal lattice mismatch, high chemical affinity, and matching crystal structures, such as the epitaxial growth of semiconductor films like GaAs on GaAs or Si on Si [41]. The FM mode generates atomically smooth surfaces featuring well-organized crystalline structures, rendering it perfect for high-precision uses in microelectronics, optoelectronics, and quantum devices. Nevertheless, it demands precise regulation of deposition conditions and is extremely responsive to substrate cleanliness and temperature [42].

3.2.3. Stranski–Krastanov Growth Mode

Stranski–Krastanov (SK) growth occupies the intermediate, strain-sensitive niche in which an initial wetting layer forms and then, beyond a critical thickness or chemical potential, three-dimensional islands nucleate to relax accumulated elastic energy, producing self-assembled nanostructures such as quantum dots in heteroepitaxy [43]. The SK transition is controlled by the interplay of interface energies, lattice misfit strain, and kinetics: misfit strain raises the energetic cost of further coherent layer growth so that islanding becomes favorable once the incremental strain energy per added layer eclipses the cost of forming island sidewalls and new interfaces [23]. From an engineering standpoint, this mode is especially powerful because the critical thickness, island size distribution, and spatial ordering can be tuned by deposition rate, substrate vicinality, and intermixing, enabling deterministic approaches to quantum-confined device elements when process windows are carefully mapped [43].

3.2.4. Step Flow Growth Mode

Step flow growth is a kinetically driven, morphology-preserving mode that occurs on stepped or vicinal substrates when adatoms incorporate preferentially at step edges, causing steps to propagate across terraces rather than nucleating new islands on terraces, and this yields macroscopically smooth surfaces even at non-zero growth rates [44,45]. To ensure the viability of step flow growth, it is required that the terrace width and adatom diffusion length be commensurate so that adatoms reach step edges before nucleating stable clusters on terraces, and this makes substrate miscut, temperature, and surface diffusion central knobs for achieving persistent step propagation [45]. In strained systems, step flow growth can persist or break down depending on strain-driven step meandering and step bunching instabilities, and controlling these instabilities through miscut selection and flux modulation is a common route for producing defect-sparse epitaxial films.

Transitions between these modes are neither abrupt nor determined solely by equilibrium wetting criteria; rather, they reflect a competition between thermodynamic driving forces (surface and strain energies) and kinetic constraints (adspecies diffusion, desorption, and supply rate), such that the same material pair can show different modes under different growth conditions [3]. As a result, predictive process design requires measuring or estimating effective surface and interface energies, mapping nucleation density and island statistics as functions of flux and temperature, and incorporating strain relaxation models that account for intermixing and finite temperature effects in realistic deposition regimes. Therefore, modern experimental workflows pair in situ surface probes such as RHEED, in-vacuo AFM/STM, and real-time X-ray scattering with kinetic modeling (rate-equation or kinetic Monte Carlo) to extract mechanistic parameters and translate laboratory observations into robust production recipes [38].

From an engineering perspective, controlling growth mode to target a film morphology is accomplished by three practical levers: tune the effective wetting through interfacial engineering (adhesion layers, surfactants, or surface functionalisation), control adatom kinetics via substrate temperature and flux pulsing or shutters, and utilize substrate templating (vicinal miscut or lithographic nucleation seeds) to bias nucleation to desired locations and scales [35]. Each of these levers carries trade-offs—surfactants can modify electronic properties, high mobility can increase interdiffusion, and templating may complicate large-area uniformity—so optimization requires quantitative feedback from both surface diagnostics and device-level tests in the target application environment [38]. The practical upshot for reviewers and process engineers is that documenting the growth mode, presenting nucleation/island statistics as a function of the principal control parameters, and correlating morphology with the targeted property (electrical mobility, optical linewidth, mechanical integrity) yields a reproducible engineering narrative that bridges fundamental physics and applied fabrication [46,47].

3.3. Adatom Kinetics

Adatom kinetics are the living engine of thin film morphology because the fate of each deposited atom—whether it migrates, attaches to an island, is captured by a step, or desorbs—determines nucleation statistics, island growth pathways, and ultimately film continuity and defect content [48]. Surface diffusion is therefore not a single mechanistic label but a family of atomistic processes that include simple hopping between adjacent adsorption sites, concerted exchange with substrate atoms, long correlated jumps, and periphery motions along island edges, where the dominant mechanism depends sensitively on the material pair, surface crystallography, and local adsorbate interactions [49]. From an engineering perspective, recognizing which mechanism is active in a system is essential because different mechanisms produce distinct effective mobilities, temperature dependences, and responses to surfactants or substrate modification [48].

3.3.1. Surface Diffusion Fundamentals

The diffusion length is the practical, experiment-usable summary variable that captures how far a mobile adatom will travel on average before being immobilized by incorporation or loss, and is the single most useful kinetic metric for linking process conditions (flux, temperature) to mesoscale outcomes such as island density and capture-zone statistics [12]. In real deposition systems, diffusion length is a dynamic quantity determined by the competition between surface mobility and the arrival (or supply) rate of new atoms, and thus is the parameter that determines whether growth proceeds in a regime dominated by heterogeneous nucleation on defects, homogeneous island nucleation across terraces, or step flow incorporation at edges [50]. Practically, mapping the diffusion length experimentally—for example, through island density versus flux/temperature series or by analyzing capture-zone distributions—gives a direct route to extract effective kinetic barriers and to design process windows required for target morphologies in device fabrication [51].

Surface diffusion mechanisms themselves can be subtle: “hopping” across the saddle point of the surface potential energy landscape is common on many metal terraces, whereas an “exchange” mechanism (in which the adatom swaps with a substrate atom) can dominate where the exchange pathway lowers the barrier, and concerted multi-atom moves or long correlated jumps are observed in both experiments and atomistic simulations for a range of material [52]. These mechanistic distinctions matter because they change not only the activation energies that control temperature sensitivity, but also the pre-factors and the effective step-capture probabilities that define how adatoms explore terraces and reach nucleation or incorporation sites [53]. For engineers, this means that a change as simple as switching substrate orientation, adding a sub-monolayer surfactant, or alloying the surface layer can switch the dominant microscopic pathway and dramatically modify the diffusion length and resulting film morphology at the same nominal temperature and flux [48]. The diffusivity of adatoms, , is typically expressed through an Arrhenius-type equation:

where denotes the pre-exponential factor associated with the attempt frequency and jump distance, represents the activation energy for surface diffusion, stands for the Boltzmann constant, and indicates the absolute temperature. A low activation energy or a high substrate temperature boosts adatom mobility by raising the chances of surpassing diffusion barriers among adsorption sites. The microscopic jump rate of an adatom usually ranges from 1012 to 1013 Hz (jumps per second), with the jump distance generally being one surface lattice spacing [54].

The energy required for diffusion is greatly influenced by the characteristics of the surface, such as crystallographic alignment, surface imperfections, and the existence of adsorbates. Diffusion barriers tend to be lower on closely packed surfaces (e.g., fcc(111)) than on more open surfaces (e.g., fcc(100)), and surface steps or kinks may function as traps or barriers based on their arrangement. Moreover, the binding energy between adatoms and substrate atoms can differ greatly among various material systems, affecting the thermodynamics and kinetics of diffusion.

3.3.2. Adatom Mobility and Film Morphology

The movement of adatoms is essential for managing film structure during deposition. Increased mobility enables adatoms to traverse wider regions of the substrate surface prior to being trapped by a developing island or step edge, resulting in the creation of larger grains, smoother surfaces, and more consistent coverage [55]. On the other hand, reduced mobility—resulting from low temperatures or significant diffusion barriers—leads to increased nucleation densities, smaller grains, and rougher films. In epitaxial growth, adequate mobility of adatoms is essential for atoms to locate energetically preferable lattice sites, which guarantees high crystalline quality. Nonetheless, high mobility can lead to undesirable effects like desorption or step flow instability, particularly under high-vacuum or elevated temperature circumstances [56].

Besides thermal activation, external elements like electric fields, ion bombardment, or surfactant layers may affect adatom mobility. For instance, ion-assisted deposition can increase surface mobility locally by delivering extra energy via momentum transfer, whereas surfactants can alter surface energy landscapes, reducing the effective diffusion barrier without being integrated into the film. This idea is utilized in methods like surfactant-assisted epitaxy.

3.3.3. Diffusion Length and Nucleation Dynamics

A crucial factor connecting adatom movements to thin film development is the surface diffusion length, , defined as:

where represents the mean residence duration of an adatom prior to its integration into a stable location. Increased diffusion lengths lead to greater nucleation separation distances, producing fewer but larger islands that merge seamlessly. Short diffusion distances result in densely packed nuclei, resulting in quick coalescence but heightened surface roughness. Control of is essential for adjusting grain size, surface texture, and defect concentration in thin films.

3.3.4. Ehrlich–Schwoebel Barriers and Step-Edge Kinetics

The Ehrlich–Schwoebel (ES) barrier is the canonical kinetic asymmetry that arises when an adatom encounters a step edge and finds an extra energetic penalty for descending (or sometimes ascending) the step, and this step-edge barrier biases mass transport and creates instabilities that control mound formation, step meandering, and the breakdown of layerwise growth [57]. In practice, a positive ES barrier reduces interlayer mass transfer and promotes vertical growth (mounding and 3D islands), whereas a negligible or negative ES barrier allows adatoms to cross steps readily and supports layer-by-layer or step flow morphologies, and the magnitude and even sign of the ES effect have been shown experimentally to vary with material, step facet and the presence of adsorbates or impurities [58]. Contemporary studies have also shown that the ES effect is not strictly a two-dimensional construct and that three-dimensional step geometries, kink sites, and facet-dependent energetics can give rise to a spectrum of effective ES barriers that must be accounted for when predicting texture selection or nanostructure evolution [59].

Because the ES barrier couples directly to step dynamics, it is the primary kinetic origin of many mesoscale instabilities observed during epitaxy, including step bunching, step meandering, and the transition from step flow to islanding on vicinal surfaces, and these instabilities are highly sensitive to the interplay between terrace diffusion length, step spacing (vicinality) and the effective interlayer barrier [59]. Consequently, device-oriented engineers exploit substrate miscut, temperature ramps, and transient flux protocols to tune the ratio between diffusion length and terrace width so as to promote step propagation rather than nucleation on terraces, thereby achieving smoother films with fewer coalescence defects [60]. Moreover, recent atomistic and in situ microscopy work shows that ES barriers on oxide and molecular surfaces can be large and chemically complex, which explains frequent surprises when applying metal-surface intuitions to organic or oxide epitaxy and underlines the need for system-specific measurement or computation of the step-edge energetics [61].

Experimentally, adatom mobilities and ES barriers are extracted using complementary approaches that include direct in situ imaging (field-ion microscopy, STM/AFM), time-resolved diffraction or scattering probes that monitor island density and coarsening in real time, and carefully designed temperature/flux series that allow fitting to rate equation or kinetic Monte Carlo models to yield effective activation energies and diffusion lengths [57]. Low-energy electron microscopy (LEEM) and grazing-incidence small-angle X-ray scattering (GISAXS) have become particularly powerful for following interlayer transport and quantifying ES contributions under realistic growth rates, while STM remains the gold standard for atomistic identification of diffusion pathways and direct observation of processes such as island decay and edge diffusion [62]. For rigorous engineering studies, it is therefore best practice to combine at least one real-space microscopy method with a statistical analysis of island size/distribution evolution such that the measured diffusion lengths and effective ES barriers are grounded in both mechanistic insight and mesoscale statistics [12].

On the modeling side, a hierarchy of tools connects atomistic energetics to macroscopic morphology: density functional or embedded-atom calculations provide the elementary barrier heights and exchange pathways; kinetic Monte Carlo captures stochastic adatom motion and emergent island statistics over experimentally relevant timescales; and continuum or rate-equation descriptions map these kinetics to average fields such as adatom density and surface height for process optimization [48]. Modern workflows increasingly integrate machine-learned surrogate models for migration barriers into kMC frameworks so that high-throughput exploration of substrate treatments, surfactant chemistries, and flux protocols becomes tractable for device-scale engineering [63]. Crucially, predictive simulations must include realistic step geometries and kink diffusion channels to capture ES-driven instabilities and facet selection; otherwise, models risk underestimating defect formation pathways that appear during scaled production runs [51].

In conclusion, surface diffusion and adatom mobility are essential kinetic factors that connect atomic-level processes with the properties of macroscopic films. Adjusting deposition temperature, deposition rate, and surface preparation allows for the engineering of adatom kinetics to promote certain growth modes, enhance microstructural quality, and satisfy application-specific performance needs in electronics, optics, catalysis, and protective coatings. Dominating these kinetic principles is crucial for converting the thermodynamic potential for superior film growth into effective, consistent results in thin film technology.

3.4. Strain and Lattice Mismatch

3.4.1. Strain States and Critical Thickness

The distinction between coherent (fully strained) and relaxed (partially or fully strain-relieved) films is therefore practical as well as conceptual, because coherent layers preserve epitaxial registry and low defect density up to a material-dependent thickness, while relaxed layers frequently exhibit dislocation networks and residual strain inhomogeneity that strongly degrade transport and optical performance in many devices [64]. For this reason, the concept of critical thickness—defined as the nominal film thickness at which misfit-relieving dislocations become energetically favorable—is central to epitaxial engineering. It serves as a primary design parameter that governs strain relaxation behavior and provides a benchmark around which growth processes, buffer-layer architectures, and interface engineering strategies are developed to achieve lattice coherence and minimize defect formation [65,66,67]. It is important to emphasize, however, that critical thickness is not a fixed or universal constant for a given material pair; rather, it depends on parameters such as temperature, growth kinetics, substrate orientation, pre-existing defect density, and the available strain-relaxation pathways [68,69]. Variations in deposition rate, adatom mobility, and interfacial energy can further modify this threshold by altering strain accumulation and dislocation nucleation dynamics. Consequently, practical film design integrates theoretical critical-thickness models with experimental thickness-series measurements, defect mapping, and reciprocal-space analyses to accurately capture the onset of strain relaxation and interfacial instability [70,71]. During the initial phases of heteroepitaxial growth, the deposited film may maintain coherent strain to align with the substrate’s lattice, creating a pseudomorphic layer. This coherent state is energetically advantageous only up to a specific thickness, after which the strain energy in the film becomes significant enough to cause relaxation. The critical thickness () is defined as the maximum thickness for preserving coherent strain without the creation of defects. The historical Matthews–Blakeslee energetic balance gives the earliest and still widely used criterion for when interfacial misfit dislocations become favorable, and that framework links the resolved line tension of a threading dislocation, the lattice misfit, and the geometry of the interface to a threshold for dislocation glide and pinning. Subsequent refinements, such as the People–Bean adaptation, introduced kinetics and more realistic energetic accounting for semiconductor strained layers, producing predictions that align much better with measured critical thicknesses in systems like Ge/Si and SiGe/Si used in microelectronics [64]. Because these continuum models are equilibrium or quasi-equilibrium formulations, modern atomistic and mesoscale studies have shown that kinetic limitations, defect nucleation barriers, and metastable trapping can allow films to remain pseudomorphic far beyond the thermodynamic critical thickness or, conversely, to relax earlier than simple models predict when heterogeneous nucleation sites or elevated temperatures are present [70]. The Matthews–Blakeslee model offers an approximate formula for critical thickness related to mismatch strain and dislocation energy [72].

where represents the Burgers vector of the misfit dislocation, denotes Poisson’s ratio, and indicates the mismatch. This relationship emphasizes that greater mismatches significantly decrease , complicating the growth of defect-free thick films.

3.4.2. Strain Relaxation Mechanisms

Misfit dislocations—the primary plastic carriers of strain relief at interfaces—exist in characteristic geometries (for example, 60° mixed dislocations and 90° edge dislocations in cubic systems) and their nucleation, glide, dissociation, and interaction pathways determine both the rate and the spatial pattern of relaxation [73]. Experimental TEM and in-plane diffraction studies have established that initial relaxation often proceeds via the formation of half-loops or surface-initiated 60° segments that can react or convert into sessile 90° misfit dislocations as the film thickens, a process that creates a complex interfacial dislocation network rather than a single uniform relaxation event. Atomistic modeling and minimum-energy path searches have further revealed multi-step transition pathways for misfit dislocation nucleation—for instance, nucleation of a 60° segment followed by a second complementary event that produces an extended 90° segment—which explains why nucleation energies and observed mechanisms can be very sensitive to surface steps, impurities, and local chemical bonding [74].

Threading dislocations, which penetrate the film from the interface into the overlayer, are the mobile carriers that link interfacial misfit reactions to bulk-like defect populations, and their density, glide mobility, and interactions (including reactions that form Lomer locks or sessile junctions) are the microstructural quantities most closely correlated with device degradation [75]. Consequently, graded buffer layers, low-temperature nucleation layers, compliant substrates, and patterned (selective-area) epitaxy have been developed as engineering countermeasures to reduce threading dislocation density and spatially control where misfit is accommodated. These strategies trade processing complexity for dramatically lower defect densities in many practical material systems [76]. Ion-implantation and post-growth anneals, which influence vacancy/interstitial chemistry and provide routes for dislocation climb and annihilation, are further tools used to accelerate or re-distribute relaxation when precise removal of elastic energy is required for device performance [77].

From a measurement standpoint, the onset and degree of relaxation are routinely quantified by a complementary suite of probes: high-resolution X-ray diffraction provides in-plane and out-of-plane lattice parameters and residual strain, TEM visualizes the dislocation network and core structures at the interface, and high-resolution reciprocal space mapping or grazing-incidence scattering can map partial relaxation and mosaic spread across macroscopic areas [73]. In situ techniques such as real-time RHEED, low-energy electron diffraction (LEED), in-vacuo AFM/STM, and synchrotron grazing-incidence X-ray scattering give access to the dynamic evolution of strain and defect nucleation during growth, which is essential for linking process transients (for example, temperature ramps or flux changes) to relaxation pathways that static post-mortem methods cannot resolve [34]. Quantitative evaluation of threading dislocation densities and interfacial misfit spacing from these probes is the only reliable way to relate a theoretical or modeled critical thickness to practical device yield metrics such as carrier mobility, optical linewidths, and mechanical reliability.

3.5. Stress and Failure

Stress and failure in thin films are central reliability challenges because residual stresses—whether tensile or compressive—alter mechanical stiffness, drive morphological instabilities and, when large enough, nucleate cracking or interfacial delamination that can destroy device function [4]. Residual stresses in deposited films arise from multiple origins and can vary widely with process, material, and post-processing, so effective engineering requires treating stress as an inseparable processing outcome rather than an independent material constant [71].

3.5.1. Sources of Stress in Thin Films

Stress in thin films can generally be divided into three types: intrinsic stress, thermal stress, and extrinsic stress.

- Intrinsic stresses originate during film growth from microstructural evolution, atomic incorporation events, and grain coalescence, and these growth-related stresses can be tensile or compressive depending on the deposition mechanism and energy flux to the growing surface [78]. For polycrystalline and columnar films, tensile stresses frequently develop during the coalescence of islands as boundaries “zip” together and trap misfit strains, while compressive stresses commonly accompany high-energy ion incorporation, peening, and atomic insertion into interstitial sites [79]. Atomistic and structural studies of amorphous and hydrogenated films have further clarified how void elimination, bond reconfiguration, and trapped impurities set the sign and magnitude of intrinsic stress in many technologically important layers [80].

- Thermal stress arises from differential thermal contraction between film and substrate after high-temperature growth or during thermal cycling, and this extrinsic component often dominates in heterostructures processed at elevated temperatures or used in variable-temperature environments [81]. The magnitude of the thermal mismatch stress is a function of the coefficient of thermal expansion difference, the film/substrate elastic moduli, and the temperature excursion, which means even modest CTE mismatch can generate stresses large enough to buckle or crack ultrathin brittle films during cooldown [82]. Thermally induced stresses can also drive time-dependent relaxation via creep or dislocation motion at elevated temperatures, so reported stresses at room temperature may represent a frozen, partially relaxed state that depends on the entire thermal history of the sample [71].

- Extrinsic stresses beyond thermal effects—including chemical reactions with ambient species, moisture uptake in organic films, hydrogen embrittlement, and radiation damage—modify both the mechanical state and interfacial toughness of films and can therefore convert a stable film stack into a progressively failing system under service conditions [83]. Environmental species can induce large compressive or tensile changes by causing swelling, phase change, or volumetric expansion, and such chemically driven extrinsic stress transients are often the trigger for buckling-delamination in multilayers and coatings exposed to humidity or reactive atmospheres [84]. Because extrinsic effects are frequently spatially non-uniform (for example, edge ingress of moisture or local corrosion), they also create stress gradients that favor crack nucleation at specific weak points rather than uniform fracture across the surface [71,85].

3.5.2. Strategies to Minimize Stress and Failure

Predicting failure requires quantifying both the driving force (residual strain energy) and resistances (film fracture toughness and interfacial adhesion), as well as recognizing that these quantities are process-dependent and often history-dependent through plasticity, diffusion, and chemical evolution [86]. Contemporary approaches combine wafer curvature tracking, in situ stress monitoring, microscale blister tests, four-point bend delamination tests, and high-resolution imaging (TEM, SEM, AFM, optical interferometry) to provide the multi-modal data required to parameterise coupled fracture–buckling models [71,87]. Finite-element and analytic fracture mechanics frameworks that incorporate mode-mixity at the interface, substrate compliance, and non-linear film behavior have matured to the point that they can reproduce key experimental observables such as buckle curvature, critical crack spacing, and delamination growth rates when supplied with realistic material and interfacial properties.

From an engineering standpoint, practical mitigation strategies fall into three complementary families: (i) process tuning to manage intrinsic stress—for example, by lowering ion energy, adjusting deposition temperature, or using pulsed flux to change microstructure; (ii) interfacial engineering to raise adhesion and interfacial toughness through adhesion layers, graded interfaces or chemical functionalization; and (iii) structural design such as patterning, compliant buffer layers or controlled thickness grading to limit stored elastic energy per debonded area [78]. Each mitigation pathway carries trade-offs—adhesion layers can change electrical or optical properties, compliant buffers can impact thermal conduction, and patterning can complicate large-area uniformity—so optimization must be driven by the target device metrics and validated by both mechanical testing and functional measurement [88]. Emerging approaches that intentionally harness controlled buckling or programmed fracture for stretchable electronics or micro-patterning show that failure modes can be repurposed as fabrication tools when the mechanics are made deterministic [89].

In conclusion, stress is an inescapable yet controllable part of thin film systems. A comprehensive grasp of stress sources, crack formation processes, and delamination mechanisms enables the creation of improved deposition techniques and structural designs. This guarantees the enduring dependability of thin films in challenging applications like semiconductor devices, optical coatings, protective barriers, and MEMS components.

3.6. Importance and Influence of Substrates in Thin Film Growth and Growth Modes

The substrate acts as the essential base upon which thin films are applied, significantly influencing the growth characteristics, microstructural development, and ultimate functional attributes of the film [90]. From the initial phases of nucleation to surface kinetics, strain accommodation, and stress formation, the substrate continually serves as a governing element that determines thermodynamic equilibrium, kinetic behavior, and mechanical integrity in thin film systems [90,91]. Its impact is multifaceted, covering interfacial energetics, lattice compatibility, diffusion dynamics, and adhesion strength, rendering it essential for producing high-quality and dependable thin films [92].

3.6.1. Thermodynamic Influence and Nucleation Control

The energies present at the surface and interfaces of the substrate are essential in the nucleation process [93]. These influence the wetting properties of the arriving atoms and decide if the film develops as uniform layers or distinct islands. The equilibrium of the substrate–vapor, substrate–film, and film–vapor surface energies determines the contact or wetting angle, serving as a definitive signal of adhesion [94]. A minimal wetting angle indicates effective adhesion and robust adatom-substrate interactions, facilitating smooth, two-dimensional layer-by-layer development. In contrast, inadequate wetting and elevated interfacial energy promote the formation of three-dimensional islands, resulting in rougher surfaces characteristic of Volmer–Weber growth [95].

In intermediate scenarios, the interaction between partial wetting and strain energy buildup results in the hybrid Stranski–Krastanov growth mode, characterized by the formation of several monolayers prior to the onset of islanding [23]. The thermodynamics of the substrate-film interface influences the nucleation process, film coherence, and surface structure [96].

In addition, substrate imperfections like steps, dislocations, and impurities serve as sites for heterogeneous nucleation, lowering the energy barrier for nucleus formation and allowing for localized management of nucleation density [97]. Engineers frequently utilize this principle via intentional surface treatment, like plasma cleaning, chemical etching, or oxide elimination, to establish consistent nucleation patterns and uniform film microstructures [98].

3.6.2. Substrate Structure and Kinetic Regulation

Aside from thermodynamics, the substrate significantly influences kinetic control during thin film development. The adatom mobility, diffusion routes, and incorporation locations are governed by its surface topology, crystal alignment, and atomic structure [99]. Vicinal or stepped surfaces encourage step flow growth, where adatoms move towards step edges and incorporate seamlessly, resulting in atomically smooth films. The diffusion characteristics of adatoms, particularly their capacity to navigate step-edge barriers, are closely related to the potential and geometry of the substrate surface [100].

The substrate also influences how energy inputs like temperature or flux impact growth morphology. Elevated substrate temperatures increase adatom mobility and lead to smoother, equilibrium-like films, whereas reduced temperatures limit movement, causing a high nucleation density and uneven surfaces. Thus, the thermal conductivity of the substrate, surface reconstruction, and orientation together influence adatom dynamics and the shift between various growth regimes [101]. Appropriate choice and preparation of substrates enable the controlled alteration of film morphology without altering deposition chemistry [13].

3.6.3. Lattice Mismatch, Strain, and Interface Coherency

The degree of strain during growth is determined by the structural compatibility between the film and substrate. When the lattice constants are well-aligned, epitaxial films can grow cohesively with few defects, allowing for atomically sharp interfaces and enhanced crystalline quality. This coherence promotes steady, two-dimensional development and is crucial for semiconductor heterostructures and quantum devices [102].

Nevertheless, lattice mismatch generates strain energy that builds up as the film thickness increases. When this strain surpasses a certain threshold, the system adapts via misfit dislocations or the formation of islands, resulting in Stranski–Krastanov or partially relaxed growth [103]. In response to this, buffer layers or graded substrates are frequently employed to facilitate a gradual shift between lattice constants, thereby reducing dislocation density and maintaining crystalline structure [104]. Substrate alignment similarly impacts the distribution of strain at the interface, affecting the chances of defect creation and strain-induced surface reconstruction. Consequently, substrate design serves as an essential engineering mechanism for managing film strain and avoiding degradation caused by defects [105].

3.6.4. Substrate Effects on Stress Evolution and Film Integrity

The mechanical and thermal properties of the substrate greatly influence the residual stress and reliability of thin films. Differential thermal expansion between the film and substrate creates thermal stresses during cooling or thermal cycling, potentially leading to cracking, buckling, or delamination. The substrate’s stiffness and adhesion strength dictate how much stress can be absorbed without causing failure [71,106].

The chemical compatibility at the interface between the substrate and film significantly influences adhesion and durability. Surfaces with appropriate chemical properties, or altered with adhesion-enhancing interlayers like titanium, chromium, or silicon oxide, can greatly improve bond strength and reduce environmental damage [107]. Consequently, substrate engineering influences both the film’s microstructure and its durability against operational stresses over time [108].

3.6.5. Engineering Significance and Practical Implications

In practical thin film engineering, the substrate acts as more than just a passive support; it actively influences growth behavior, structure, and performance. By careful choice and surface modification, substrates facilitate:

- Regulation of growth modes through the adjustment of interfacial energies and wetting characteristics [109].

- Enhancement of film consistency and texture through surface designs or tiered shapes [110].

- Decreasing strain and defect densities via lattice-matched or flexible buffer layers [111].

- Enhanced adhesion and longevity through chemical alterations or graded interfacial designs [112].

In conclusion, the substrate is the primary controlling element in the growth of thin films. It governs the thermodynamic environment for nucleation, the dynamic routes of adatom displacement, and the structural basis for stress development. Expertise in substrate characteristics and preparation enables exact regulation of film morphology, quality, and functionality, thereby connecting theoretical growth models with actual device manufacturing.

4. Thin Film Deposition Techniques

Thin film deposition is integral to the development of contemporary electronic, optical, or nanostructured devices. This process involves applying a controlled thickness of material (a few nanometers to a few micrometers). The role of thin films is to improve surface properties such as conductivity, reflectivity, corrosion resistance, and strength [113].

Technologies for deposition processes are expanding and have led to a variety of deposition techniques to satisfy the requirements for advanced applications. Thin film deposition is often classified as physical, chemical, and electrochemical processes, and there are advantages with each type of technique in terms of quality of the film, adhesion, uniformity, and scalability [114]. Different deposition techniques can produce thin films with various structural and electrical properties based on the type of material deposited and the substrate. The material to be deposited will dictate the choice of deposition technique, along with consideration of the substrate, the operating temperature, and the desired properties [115].

4.1. Physical Vapor Deposition Techniques

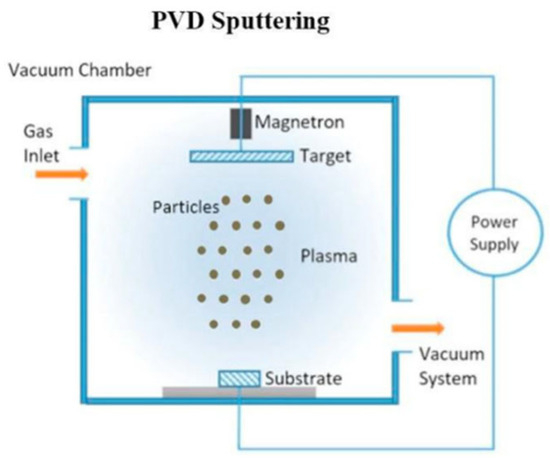

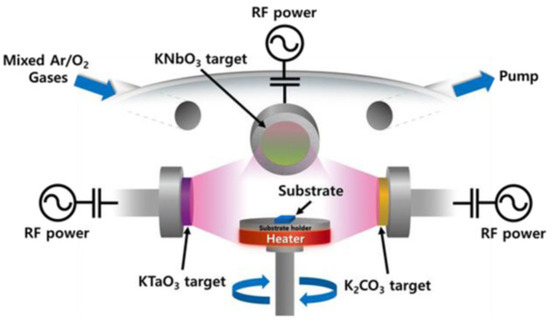

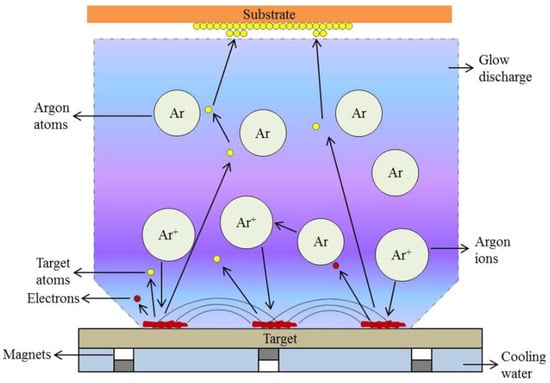

Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) covers a family of vacuum deposition techniques in which a solid material is physically transformed into a vapor state and allowed to condense on a substrate to form thin films [116]. While some techniques involve chemical processes, PVD processes are purely physical processes, such as evaporation, sputtering, or ablation, where material is simply moved to the substrate through transfer [117]. PVD processes are very beneficial for producing coatings that require high purity, high performance, good adhesion, and uniformly thick films for a variety of applications. The technologies are important for areas such as microelectronics, optics, aerospace, and tools in which film thickness and composition require precision control during deposition [118]. The principal PVD techniques typically include thermal and electron beam evaporation, various sputtering techniques, continuous wave and pulsed laser deposition, ion beam deposition, and cathodic arc deposition. Each process can offer specific advantages primarily related to deposition rate, film density (or porosity), and capacity or ability to coat complex parts [118].

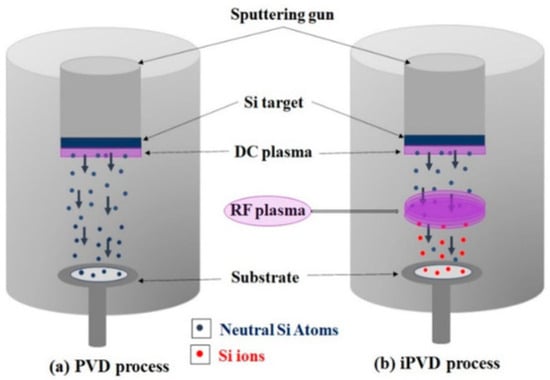

In conventional Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD), material from a solid target is ejected through direct current (DC) magnetron sputtering, and the resulting neutral atoms travel through the vacuum to deposit directly onto the substrate surface. The process is governed primarily by physical collisions between the target and plasma ions, with limited control over the ionization state and directionality of the deposited flux. However, in Ionized Physical Vapor Deposition (iPVD), an additional radio-frequency (RF) powered plasma is introduced between the target and substrate, creating an intermediate plasma zone that enhances the ionization of sputtered silicon species before deposition. This increased ionization allows the film-forming species to be accelerated and guided by the sheath electric field toward the substrate, thereby improving step coverage, adhesion, and film density—even at low or room temperatures [119].

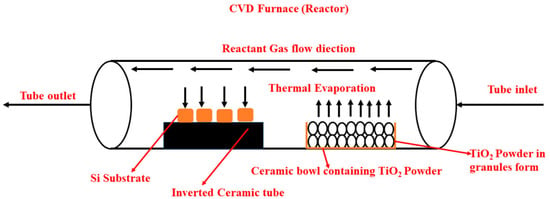

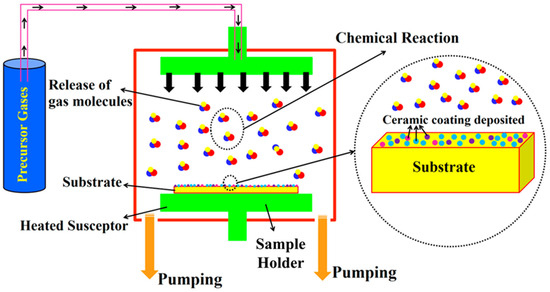

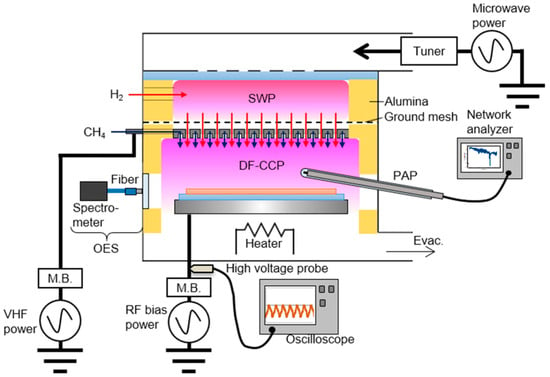

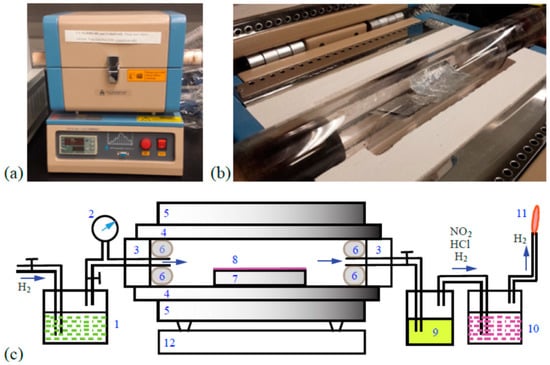

The underlying principle is that the additional RF plasma increases the fraction of ionized atoms relative to neutral species, resulting in a more energetic and directed deposition flux. This enables superior microstructural control, particularly on complex or high-aspect-ratio surfaces, compared with the conventional PVD process, where only neutral atoms contribute to film growth. The comparative schematic shown in Figure 3 illustrates these fundamental distinctions, where panel (a) represents the neutral atom-based PVD process and panel (b) depicts the iPVD configuration featuring an RF-induced plasma region that generates ionized silicon flux for enhanced thin film formation.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of (a) conventional Physical Vapor Deposition and (b) Ionized Physical Vapor Deposition processes [119].

4.1.1. Thermal Evaporation Technique

Thermal evaporation is a basic PVD technique and is typically the one that produces the highest-purity thin films. Thermally vaporized source materials are heated in a vacuum, and the vapors are condensed on a substrate. The ‘thermal’ aspect of the technique relies on the use of resistive heating to raise the source material’s temperature to its vaporization point. Typical resistance heating sources include filament wires, boats, or crucibles made from ‘refractory metal’ sources such as tungsten and molybdenum, which are durable and stable under vacuum due to their mostly high melting points. The source material vaporizes and releases atoms or molecules into the vacuum, usually linearly, due to a lack of collisions (low chamber pressure, typically from 10−5 to 10−7 Torr). The vaporized materials reach a relatively cooler substrate above the source and condense to form a continuous film layer [120].

The rate of deposition is often measured in real-time using a QCM and, of course, will be affected by all of the parameters like source temperature, source vapor pressure of the deposited material, distance from the source to the substrate, etc. In addition to producing thin films which are highly pure, dense, and smooth, because there are no reactive gases present and the kinetic energy of individual particles is quite low during thermal evaporation, allows for high-quality thin film deposition [121].

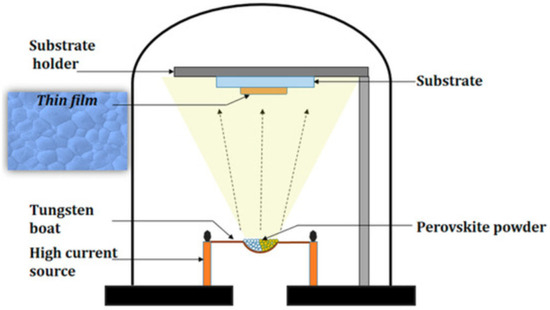

In the Thermal Evaporation Technique, a high-purity solid source material is resistively heated inside a high-vacuum chamber until its vapor pressure becomes sufficient for atomization. The vaporized species then travel through the evacuated environment in a line-of-sight trajectory toward the substrate, where they lose kinetic energy and condense to form a dense, uniform thin film. Because the deposition takes place under low pressures (typically 10−5–10−6 mbar), collisions between vapor atoms and residual gas molecules are minimized, ensuring high-purity film growth with excellent control over thickness, stoichiometry, and surface morphology [122]. The overall working mechanism of this process is depicted in Figure 4, which illustrates the resistive heating of a silicon or metallic source using a tungsten boat, vapor-phase transport through the vacuum chamber, and subsequent condensation and nucleation on the cooled substrate surface. Such controlled physical vapor transport allows the fabrication of films with superior adhesion and uniformity, particularly useful for optoelectronic and dielectric applications.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the Thermal Evaporation Technique [122].

Film uniformity and adhesion are influenced by factors such as substrate temperature, surface cleanliness, vacuum quality, and deposition rate [123]. Poor step coverage is a well-known limitation, as the vapor travels in a line-of-sight path that makes it difficult to coat exposed sidewalls or features in recessed areas on a structured substrate. To improve step coverage, vendors now provide rotary stages, hot/cool rotating stages, and planetary holders.

Additionally, because thermal evaporation is a non-reactive method of deposition, a reactive gas must be used to form compounds (e.g., nitride or oxide) during or after the deposition process. Despite these constraints, thermal evaporation is still a requirement in a number of technology areas because it is easy to operate, low cost, scale-up, and can be performed on sensitive substrates.

Thermal evaporation is widely used for semiconductor fabrication, optical multilayers, photovoltaics, surface passivation, sensor work, and vacuum metallization for decorative or barrier purposes. Even in a research setting, thermal evaporation is a well-understood and practical deposition method that has been used to prototype nanostructured films, deposit quantum dots, and functional coatings in state-of-the-art materials research [124]. Its capability to produce highly uniform films, while maintaining nanometer-level film thickness, in various cleanroom-compatible conditions has ensured that thermal evaporation will continue to play a major role in thin film technologies.

4.1.2. Electron Beam Evaporation

Electron beam evaporation is an advanced PVD process. It is a high-precision technique that deposits high-purity, dense, and uniform thin films. This allows for high-purity deposits because it utilizes a focused high-energy electron beam to thermally evaporate source material instead of resistive heating. The source material is generally provided from a heated element, or tungsten filament, that emits electrons. These electrons are then accelerated using a high-voltage electric field, commonly between 5 and 20 kV, before being affected by magnetic or electrostatic fields to direct the focused energy onto the source material [125]. The source material needed for evaporation is then placed in a copper crucible, often cooled with water, which allows for a large area deposit. This crucible usually allows for multiple “pockets” (multi-pocket configuration) to allow for either sequential or composite/combined evaporation. The high-energy electron beam delivers both high-intensity and localized energy to the source material, which means that source materials with even high melting points (tungsten ~3422 °C, molybdenum ~2623 °C) are melted and evaporated without heating or melting the chamber or crucible, and dramatically reduces thermal stress and possible contamination [125].

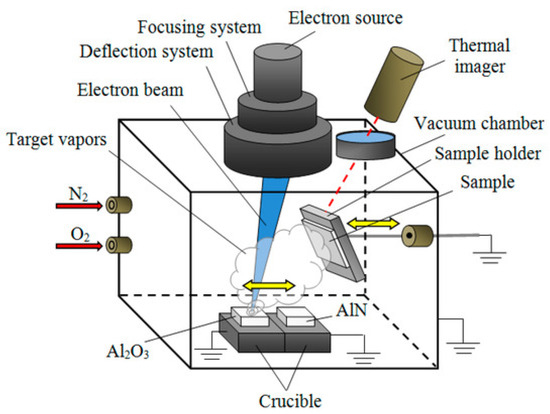

In the Electron Beam Evaporation (EBE) system, as illustrated in Figure 5, a high-energy electron beam generated by thermionic emission from a tungsten filament is accelerated under a high-voltage electric field and magnetically focused onto the source material positioned within a water-cooled copper crucible. Unlike conventional resistive heating, this method enables localized and precisely controlled energy delivery, allowing the evaporation of materials with extremely high melting points such as tungsten (~3422 °C), molybdenum (~2623 °C), and alumina (~2072 °C). The concentrated beam melts and vaporizes the target surface while minimizing thermal load on the surrounding chamber components. The vaporized species then traverse the vacuum space (typically maintained at 10−5–10−6 Torr) in a line-of-sight trajectory before condensing onto the substrate to form a dense, uniform, and adherent thin film. The electron source, focusing–deflection assembly, and crucible geometry are designed to ensure beam stability and deposition uniformity, enabling the fabrication of high-purity coatings with nanometer-level control over film thickness and composition [126].

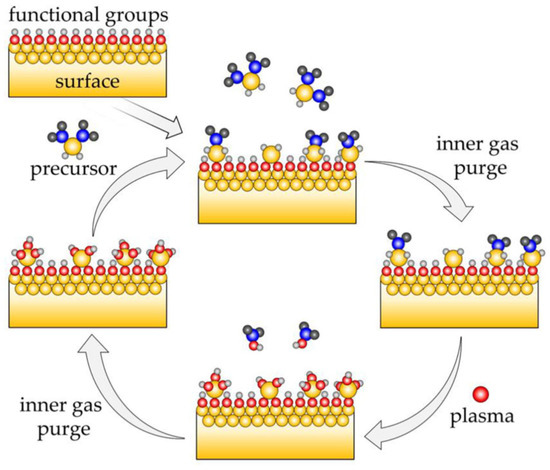

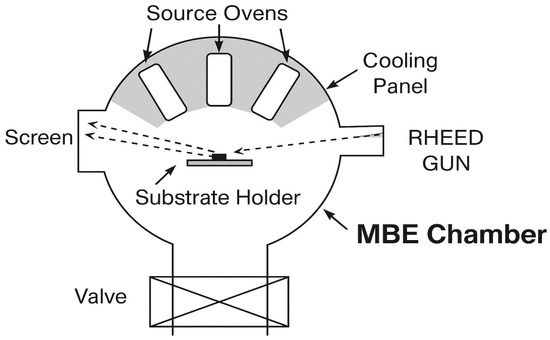

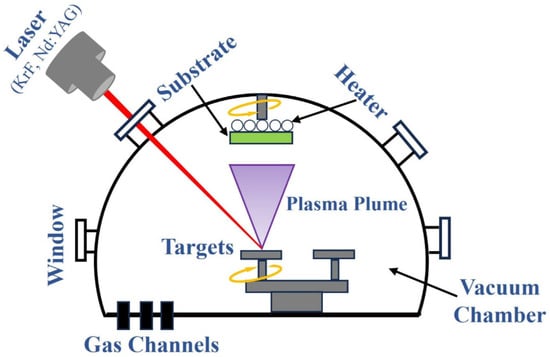

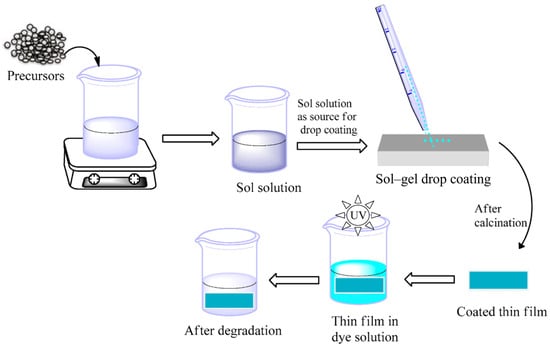

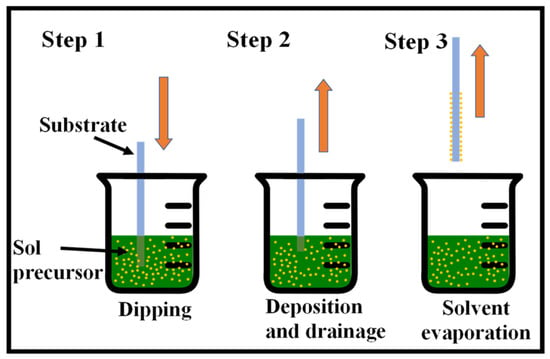

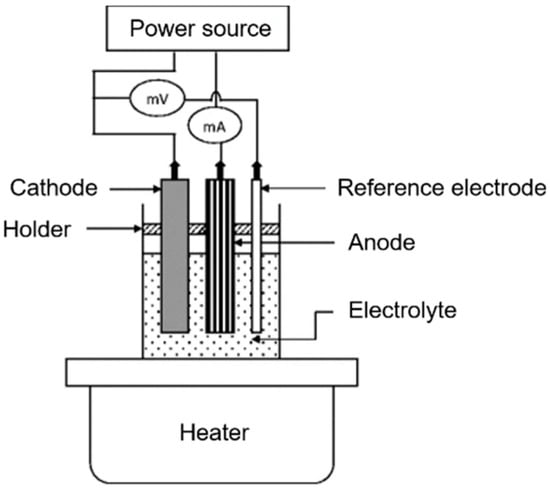

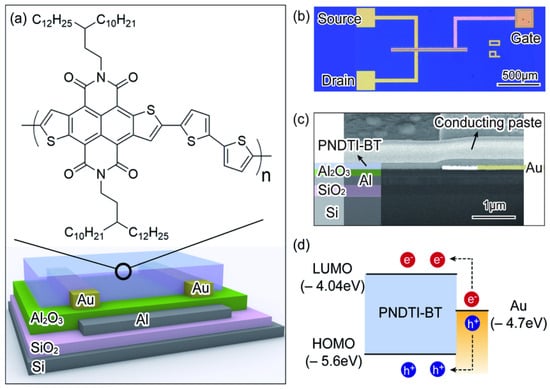

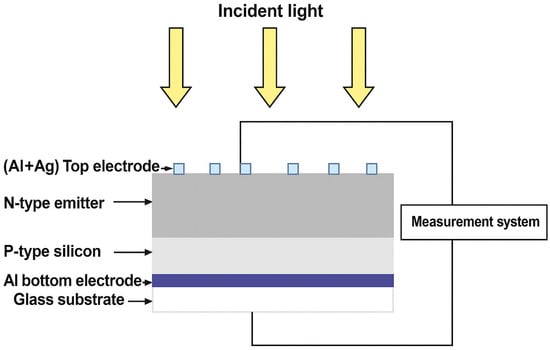

Figure 5.

Electron Beam Evaporation [126].