Abstract

Carbonate reservoirs, which hold a significant portion of the world’s oil reserves, are particularly challenging for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) due to their predominantly oil-wet nature and low permeability. Smart water injection (a low-cost, environmentally friendly EOR method) has demonstrated potential to enhance recovery by modifying rock wettability. While numerous studies have examined smart-water mechanisms, the specific role of initial wettability (including Swi and core preservation state) in controlling its efficiency remains insufficiently quantified. This study addresses this critical gap by systematically investigating how initial wettability affects oil recovery during smart water flooding in a Middle Eastern carbonate reservoir. Core flooding experiments were conducted using brines enriched with potential-determining ions (SO42−, Ca2+, Mg2+) under varying wettability conditions. These tests were performed under controlled initial wettability conditions (Swi and preservation state) to ensure consistent and representative comparison across brine types. Results reveal that initial rock wettability plays a pivotal role in dictating the extent of wettability alteration and oil displacement. In strong oil-wet samples, sulfate-enriched brines induced substantial wettability shifts, significantly enhancing recovery. Conversely, ion saturation effects were observed, limiting further improvement beyond a threshold. Quantitatively, spontaneous water-displacement tests on core 122 at ambient conditions yielded 8.1% of OOIP at Swi = 10%, approximately twice the recovery of the same core in a dry (Swi = 0%) condition. Under reservoir-temperature core-flooding, seawater increased oil recovery from 38.3 to 53.1% OOIP in sample 122 and from 42.2 to 54.1% OOIP in sample 188 relative to formation water, corresponding to incremental gains of about 10–15 percentage points. These findings highlight the critical role of initial wettability characterization in designing effective smart-water EOR strategies. Tailoring brine composition to reservoir-specific wettability conditions enabled recovery improvements of approximately 10–15 percentage points relative to formation water at reservoir temperature. The results provide clear mechanistic insight into ion-specific interactions and offer practical guidance for optimizing smart-water formulation and deployment in carbonate reservoirs.

1. Introduction

Carbonate reservoirs host a large share of the world’s oil reserves and are especially important in regions such as the Middle East, North Africa, and North America, yet they often exhibit complex pore structures, natural fracturing, and predominantly oil-wet surface conditions [1,2,3]. These characteristics, combined with low matrix permeability, make conventional waterflooding relatively inefficient and lead to large volumes of stranded oil. Because wettability controls capillary pressure, relative permeability, and fluid distribution in porous media, shifting carbonate rocks toward more water-wet conditions is a central strategy for improving capillary-driven imbibition and enhanced oil recovery (EOR) [4,5,6].

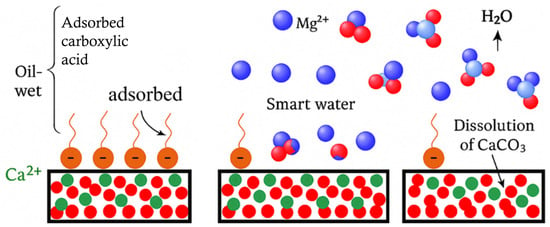

Smart water injection (also referred to as engineered or ion-tuned waterflooding) has therefore emerged as a relatively simple and low-cost EOR option in carbonates. Instead of adding surfactants or polymers, smart water relies on optimizing the ionic composition of the injected brine—typically by tuning the concentration of potential-determining ions (PDIs) such as Ca2+, Mg2+, and SO42−—to promote favorable rock–fluid interactions and wettability alteration. Numerous laboratory and field studies have shown that such PDIs can modify surface charge at the carbonate–brine interface, displace adsorbed polar oil components, and reduce adhesion forces, leading to improved water wetness and higher oil recovery [1,7,8,9,10,11,12]. A simplified schematic of these wettability-alteration mechanisms in carbonate rocks is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of smart-water mechanisms in carbonate reservoirs, highlighting the role of potential-determining ions (Ca2+, Mg2+, SO42−) in modifying surface charge, desorbing polar oil components, and shifting rock wettability toward more water-wet conditions. Green circles represent Ca2+ bound to the carbonate surface; red circles represent negatively charged surface groups; blue circles represent Mg2+/SO42− ions in smart-water brines; orange shapes depict adsorbed carboxylic acids responsible for oil-wet conditions.

Recent state-of-the-art reviews on low-salinity and smart water flooding in carbonates emphasize both the promise and the complexity of the technique. They document significant incremental recovery in many laboratory and field cases, but also highlight non-monotonic and sometimes inconsistent responses as salinity and PDI concentrations are varied, particularly in carbonate rocks where the role of divalent ions remains debated [13,14,15]. A complementary perspective is provided by Rodriguez and Shaffer (2024) [3], who systematically evaluated how invading-fluid (IF) chemistry affects wettability and displacement patterns in model oil-wet carbonate media. Their work showed that dissolved Ca2+ can reduce the magnitude of the negative surface charge and promote more stable displacement fronts, but also underscored that the relationship between IF chemistry, wettability, and recovery in carbonates is still not fully predictable [3]. Representative experimental and field studies on low-salinity and smart-water flooding in carbonate reservoirs, including their rock types, brine recipes, and reported recovery trends, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of previous smart water studies in carbonate reservoirs.

Beyond conventional smart brines, several recent studies have investigated more complex formulations and mechanistic tools. Li et al. (2020) combined contact-angle, adhesion-force, and oil-liberation measurements on carbonate surfaces to demonstrate that low-salinity brines containing SO42−, Ca2+, and Mg2+ can substantially reduce adhesion and enhance crude-oil release, while also showing that not every low-salinity composition is an effective injection water [16].

Pore-scale and mechanistic models based on DLVO theory have likewise been used to link ion exchange, double-layer expansion, and pore-filling sequence to oil recovery in carbonates under low-salinity flooding. In parallel, smart nanofluids and hybrid engineered waters have been proposed, where nanoparticles or ionic liquids are added to tuned brines to further modify wettability, reduce interfacial tension, or stabilize displacement fronts [17].

These efforts collectively confirm that tailoring brine composition can be a powerful EOR lever, but they also reveal a strong sensitivity to rock mineralogy, crude-oil composition, experimental protocol, and flow conditions.

Despite this extensive body of work, two key limitations remain for carbonate reservoirs. First, most smart-water and low-salinity studies are conducted on model rocks or cleaned core plugs whose initial wettability has been artificially established by aging protocols, with limited control or reporting of core preservation and native state. Consequently, the influence of core handling, oxidation, and initial water saturation (Swi) on the apparent smart-water response is often unclear, even though these factors are known to affect Amott indices, capillary forces, and imbibition behavior [9,14,18,19]. Second, there is still a lack of systematic experiments on field carbonate cores that isolate the interplay between (i) initial wettability (including Swi and preservation condition) and (ii) brine chemistry (FW, SW, and ion-modified SW) under true reservoir temperatures. Most prior work focuses either on brine composition at ambient/low temperatures, or on mechanistic measurements (contact angle, zeta potential, thin film stability, Hele-Shaw cells) that are not directly linked to core-scale oil recovery [3,20,21,22].

The present work addresses these gaps by using a set of field carbonate core plugs from a Middle Eastern reservoir to systematically assess how initial wettability conditions govern the efficiency of smart water injection. First, spontaneous imbibition tests were performed on cores with different initial water saturations (Swi = 0 and 10%) and preservation histories to quantify the impact of native wettability and Swi on capillary-driven recovery at ambient and elevated temperatures. Second, high-temperature (113 °C) spontaneous imbibition and forced-imbibition core-flood experiments were conducted using formation water (FW), seawater (SW), and an ion-modified smart brine (SW0NaCl·4SO4) to evaluate the incremental contribution of PDIs under realistic reservoir conditions. Finally, the combined results are interpreted in terms of Amott indices, brine composition, and potential sulfate-saturation effects, providing practical guidance for when seawater alone is sufficient as a smart brine and when further ion modification is unlikely to yield additional recovery. In this way, the study links initial wettability, core preservation, and brine chemistry to smart-water performance in representative carbonate reservoir rocks, offering a more condition-aware framework for screening and designing smart water EOR projects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Core Samples

Five core plugs were obtained from the SA reservoir, including both SA-B, SA-C and the Mishrif formation. The samples were cylindrical and characterized by their depth, diameter, and bulk volume (Table 2). These cores were used for wettability alteration and smart water injection experiments.

Table 2.

Properties of core samples from SA reservoir.

2.2. Core Sample Preparation, Characterization and Aging

Core samples were first cleaned using a Soxhlet extractor with a 70:30 mixture of toluene and methanol until the effluent became clear (approximately two weeks). This was followed by low-rate solvent flooding (0.05–1 mL/min) to ensure deep pore cleaning. After cleaning, the cores were oven-dried at 90 °C to constant weight. Once dry, the cores were fully saturated with deionized water under vacuum, and porosity was calculated from the difference between dry and saturated weights and the bulk volume; results are provided in Table 3. Routine core-analysis data for the reservoir interval from which these plugs were obtained report permeability values in the range of 8–10 mD. The plugs selected for this study are representative of this interval, and this permeability range is used when interpreting the recovery behavior in this work.

Table 3.

Pore volume and porosity of core samples.

Mineralogical characterization using X-ray diffraction (XRD) (XRD; GNR, APD 2000 PRO, Milan, Italy) confirmed calcite (CaCO3) as the dominant mineral phase, while X-ray fluorescence (XRF) revealed high CaO content and low impurity levels. These analyses were conducted using equipment from GNR and Thermo Scientific (XRF; Thermo Scientific, ARL Quant’X, Waltham, MA, USA). BET surface area analysis using the AUTOSORB-1 instrument (Quantachrome, AUTOSORB-1, Boynton Beach, FL, USA) measured a specific surface area of 0.24 m2/g and an average pore size of 18.27 nm, indicating limited available surface area for smart water interaction. Initial water saturation (Swi) was adjusted to 10% using a silica gel-based vapor absorption method, followed by a gravimetric calculation based on pore volume. Low initial water saturations (Swi = 0–10%) were selected because Middle Eastern carbonate reservoirs commonly exhibit Swi values below 10% under oil-wet conditions, and similar Swi ranges have been used in previous imbibition and smart-water studies; this range also enhances the sensitivity of the system to wettability-alteration effects. The cores were equilibrated at low temperatures for at least three days to ensure stability before use. Cores were flooded with 4 pore volumes (PV) of filtered reservoir oil at 0.1 mL/min using a Hassler-type core holder (Vinci Technologies, Nanterre, France). Then, the cores were aged in crude oil at 90 °C for two weeks to restore reservoir wettability conditions. No direct Amott or contact-angle measurements were performed on these specific cores; wettability restoration was inferred from the aging protocol, crude-oil properties, and the spontaneous-imbibition behavior, which is consistent with previously reported oil-wet carbonate systems. A detailed mineralogical summary of the core plugs based on XRD and XRF analysis is provided in Table 4, showing that the samples are dominantly calcite (>99%) with only trace impurities.

Table 4.

Mineralogical composition of the carbonate core plugs based on XRD and XRF analyses.

2.3. Crude Oil Preparation

Crude oil was centrifuged at 4000 rpm and filtered using 2.5 µm paper to remove asphaltenes and particulates. TAN and TBN were measured as 1.3 and 1.93 mg KOH/g, respectively. Density was measured using Anton Paar DMA-4100 (Anton Paar, DMA 4100 M, Graz, Austria) (API = 29.45), and viscosity data confirmed Newtonian behavior at 25 °C. Asphaltene content was 0.46 wt% using a modified ASTM D2007-80 protocol.

2.4. Brine Preparation

In this study, three brine types were used: formation water (FW), synthetic seawater (SW), and a smart brine denoted SW0NaCl·4SO4. FW was synthesized to match the reservoir formation water composition based on the ionic analysis provided by the operating company, so that the laboratory brine would reproduce the in situ connate-water chemistry.

SW was prepared as a synthetic analogue of the seawater planned for injection. Analytical-grade salts (NaCl, CaCl2, MgCl2, Na2SO4, NaHCO3 and minor components) were dissolved in deionized water in a stepwise sequence designed to minimize local supersaturation and precipitation during mixing and subsequent heating. The final ion concentrations for FW and SW are listed in Table 5 and Table 6, respectively.

Table 5.

Salt Masses for 1 L Formation Water Preparation (FW).

Table 6.

Salt Masses for 1 L Seawater (SW).

The smart brine SW0NaCl·4SO4 was derived from the SW composition following the smart-water concept for carbonate reservoirs proposed by Fathi et al. [23]. Starting from synthetic SW, NaCl was removed and Na2SO4 was added such that the sulfate concentration was approximately four times that of the base seawater, while Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations were kept at their SW levels. This formulation had three specific objectives: (i) to reduce overall salinity and the concentration of monovalent Na+, thereby expanding the electrical double layer; (ii) to maximize the availability of SO42− as a potential-determining ion that can promote Ca2+/Mg2+–SO42− surface complexation and desorption of polar oil components from the carbonate surface; and (iii) to remain below known sulfate-scaling thresholds at 113 °C by respecting solubility limits during the stepwise salt-addition procedure. The detailed salt masses and resulting ion concentrations for FW, SW, and SW0NaCl·4SO4 are reported in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7. Based on the weighed salt masses, the total dissolved solids (TDS) were approximately 171,000 ppm for FW, 48,900 ppm for SW, and 31,980 ppm for SW0NaCl·4SO4.

Table 7.

Smart Brine Salt Composition.

The pH of all brines (FW, SW, and SW0NaCl·4SO4) was measured at room temperature and after heating to 113 °C in sealed containers. pH remained stable within ±0.2 units, indicating no significant pH drift or reaction with container materials.

All brines were mixed using a stepwise salt-addition sequence to avoid local supersaturation and prevent precipitation. During heating to 113 °C, each brine was visually inspected for cloudiness or solids, and no precipitation was observed. The sulfate-enriched smart brine was formulated below known CaSO4 and MgSO4 solubility limits at 113 °C to prevent scaling. These procedures ensured that the injected brine compositions remained stable throughout the experiments. Brine compositions were therefore controlled gravimetrically via analytical-grade salt weighing and volumetric preparation rather than by separate ion-chromatography analysis.

2.5. Reproducibility and Experimental Uncertainty

All experiments in this study were conducted on preserved field carbonate core plugs, and each imbibition or core-flooding test is inherently destructive and irreversible. Consequently, it is not possible to repeat the full flooding sequence on the same core under identical initial conditions. To assess internal consistency, the ambient spontaneous imbibition protocol was applied to two cores (122 and 194) at two initial water saturations (Swi = 0% and 10%), yielding four experiments that followed the same workflow and showed consistent trends in recovery versus Swi. Before each high-temperature core-flood test, the flooding system was carefully checked for leakage, and all pressure transducers and the back-pressure regulator were verified to be functioning correctly; a bypass line was used during thermal ramp-up to equalize pressure across the core and avoid unintended flow. Given the limited availability of preserved reservoir cores, the experimental design emphasized coverage of different initial wettability and brine-chemistry conditions rather than statistical replication. The observed recovery trends are monotonic and physically consistent with established imbibition behavior in carbonate rocks, which supports the reliability of the reported results.

Core dimensions were measured with an accuracy of ±0.01 cm, and porosity was determined with an uncertainty of approximately ±0.3 p.u. Brine salinity was controlled within ±0.1 g/L based on calibrated salt masses and checked using a conductivity meter. Pump flow rates were stable within ±0.02 mL/min, and pressure transducers had an accuracy of ±0.1 bar. The oven and pump-heater temperatures were maintained within ±1 °C of the setpoint. These uncertainties are within typical limits reported for carbonate core-flooding experiments and do not affect the qualitative trends discussed in this work.

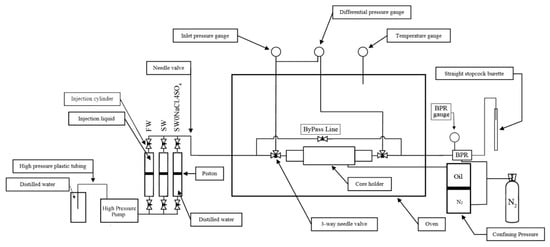

2.6. Core Flooding Equipment and Operating Conditions

Core-flooding experiments were performed using a Vinci Technologies core-flood system (Vinci Technologies, Nanterre, France) equipped with a Hassler-type core holder and high-pressure positive-displacement pumps for brine injection (Figure 2). Each core plug was wrapped with Teflon tape and mounted inside an aluminium sleeve, then confined using nitrogen at approximately 500 psi to ensure radial sealing. A back-pressure regulator (BPR) at the outlet was set to 250 psi to prevent boiling and maintain liquid stability during testing. All core-flooding experiments were conducted at a reservoir-representative temperature of 113 °C. These operating conditions ensured that the injected brines remained in the liquid phase throughout the flooding sequence.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the core flooding system used for forced imbibition tests at reservoir temperature (113 °C).

The system included inlet and outlet pressure transducers, a temperature-controlled oven, and automatic logging of pressure, temperature, and cumulative injection volume. All injections were performed at a controlled flow rate of 0.05 mL/min (≈1 ft/day). Prior to each experiment, a bypass line was opened during heating to equalize pressure across the core and closed only after thermal and pressure equilibration had been achieved.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overview

This study investigates the potential of smart water flooding in a carbonate reservoir by analyzing wettability alteration and its impact on oil recovery. The experimental program included spontaneous and forced imbibition tests under various brine compositions and temperatures to evaluate rock-fluid interactions.

It should be noted that each spontaneous- and forced-imbibition experiment is destructive and cannot be repeated on the same core plug under identical initial conditions. As discussed in Section 2.5, preserved reservoir cores were available only in limited numbers; therefore, the experimental design emphasized coverage of different initial wettability and brine-composition conditions rather than repeated runs. The recovery trends are consistent across cores and Swi states and are in line with established imbibition behavior in carbonate rocks, supporting the reliability of the reported data.

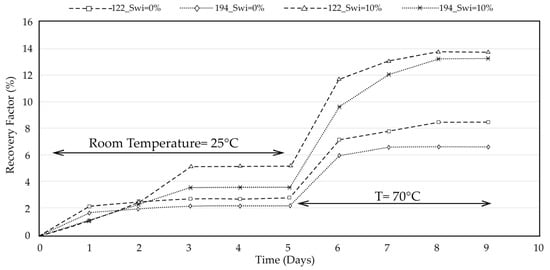

3.2. Spontaneous Imbibition Results

Figure 3 compares spontaneous imbibition recoveries for cores 122 and 194 under two initial water-saturation conditions (Swi = 0% and 10%) at two temperatures (25 °C and 70 °C). At ambient temperature, both cores exhibit low recovery when fully oil-saturated (Swi = 0%), reaching only ~2–3% OOIP after 5 days. Increasing Swi to 10% enhances capillary-assisted imbibition, approximately doubling the recovery to ~4–6% OOIP over the same period, indicating that even small initial water contents promote faster water penetration in oil-wet carbonates.

Figure 3.

Spontaneous imbibition oil recovery curves for core samples 122 and 194 under two initial water saturation conditions (Swi = 0% and 10%) at ambient and elevated temperatures (25 °C and 70 °C).

Raising the temperature to 70 °C accelerates the imbibition process for both cores, with recoveries increasing sharply after day 5. At this elevated temperature, core 122 reaches a maximum recovery of ~14% OOIP at Swi = 10% and ~8% at Swi = 0%, while core 194 exhibits slightly lower but parallel trends, reaching ~13–14% (Swi = 10%) and ~7% (Swi = 0%). The steeper recovery slopes at 70 °C reflect the combined effects of reduced oil viscosity and faster wettability-alteration kinetics.

Overall, the comparison demonstrates that both initial water saturation and temperature exert strong control over spontaneous imbibition, with higher Swi enabling more efficient capillary-driven recovery and elevated temperature amplifying the rate and magnitude of oil displacement.

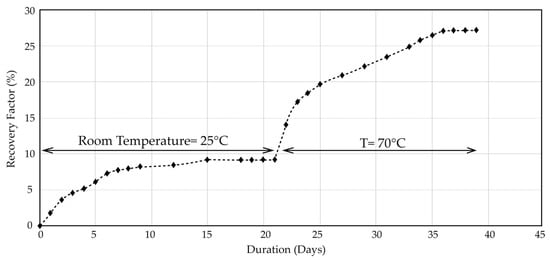

Following this, an additional spontaneous imbibition test was carried out on a core sample 22–91 from the SA reservoir (Figure 4), again using distilled water and Swi = 0%. The test was first performed at room temperature and then extended to 70 °C to assess thermal effects.

Figure 4.

Spontaneous imbibition oil recovery (% OOIP) for core sample 22–91 at ambient (25 °C) and elevated (70 °C) temperatures.

An intermediate temperature of 70 °C was selected to provide a step between ambient (25 °C) conditions and the reservoir temperature of 113 °C. This temperature is commonly used in carbonate smart-water studies to accelerate surface-reaction and wettability-alteration mechanisms while avoiding brine-chemistry changes or sulfate precipitation that may occur at higher temperatures. Because only a limited number of preserved field cores were available, additional temperature levels could not be tested; therefore, a complete recovery-versus-temperature trend could not be constructed.

All recoveries are expressed as % OOIP and thus normalized by pore volume. The three cores have similar permeability (8–10 mD) and porosities in the range 18–23% (Table 2 and Table 3), so the much higher recovery of 22–91 is attributed primarily to differences in initial wettability and preservation rather than to variations in rock quality. This enhanced performance is consistent with the better preservation condition of sample 22–91, which had minimal exposure to air and contaminants. Such handling tends to better preserve native wettability and makes the core more representative of in situ reservoir conditions. The relatively lower recovery from the older cores is therefore interpreted as being influenced by differences in preservation and handling history rather than by porosity or permeability alone, in agreement with previous observations that core handling can significantly affect measured wettability.

3.3. High-Temperature Spontaneous Imbibition (113 °C)

To simulate realistic reservoir conditions spontaneous imbibition experiments were conducted at 113 °C using a stainless steel Amott cell system. At this elevated temperature, imbibition must be performed under pressure to prevent water boiling and ensure system stability. The test apparatus consisted of a pressure-resistant steel cell filled with degassed, 2.5 µm-filtered formation water and pressurized using a piston-cylinder assembly with compressed air at 10–15 bar. This pressure elevates the boiling point of water to approximately 170 °C, enabling stable operation at the test temperature.

Core sample 122 was placed inside the cell, and the oil expelled over time was periodically sampled and measured. To maintain pressure equilibrium, fluid extraction was performed very slowly; rapid withdrawal risks boiling and complete failure of the experiment. The steel cell was designed with a conical top cap, facilitating the efficient collection and upward migration of liberated oil droplets. These droplets slide along the cone surface and exit from a dedicated outlet at the top, ensuring complete recovery of the oil expelled by imbibition.

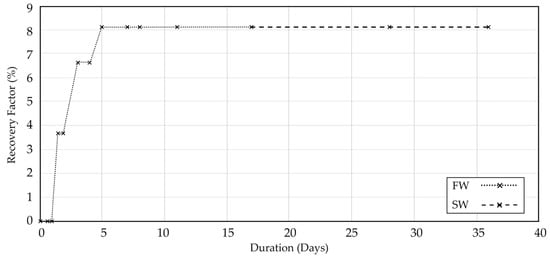

After 17 days, oil recovery reached a plateau, indicating the end of spontaneous imbibition using formation water (FW). At this point, without disturbing system pressure, the fluid inside the cell was carefully replaced with synthetic seawater (SW), and oil recovery was again monitored over time. As illustrated in Figure 5, oil production occurred mostly during the first five days, after which no further recovery was observed, even after fluid replacement and continuation of the experiment up to 38 days.

Figure 5.

Oil recovery curve for core sample 122 during spontaneous imbibition at reservoir temperature (113 °C).

Contrary to expectations based on ambient-temperature imbibition results, no additional oil was recovered after switching to SW. This inconsistency suggests that sample 122 may not have fully retained its native wettability; factors such as post-coring exposure and handling during storage can influence surface conditions and imbibition behavior, as reported in previous wettability studies.

3.4. Core Flooding Results

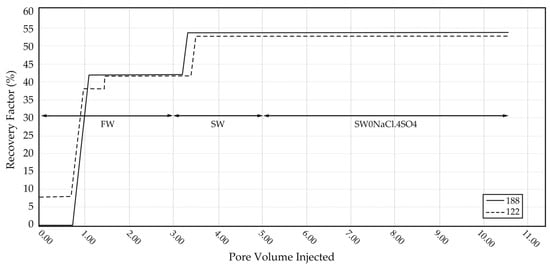

Forced imbibition tests were conducted using a core flooding system at 113 °C, to simulate reservoir conditions. Core samples 122 and 188 were subjected to sequential waterflooding with formation water (FW), seawater (SW), and ion-modified seawater (SW0NaCl·4SO4). The oil recovery versus pore volume injected was continuously recorded (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Oil recovery (% OOIP) versus pore volumes injected during forced-imbibition core-flooding tests at 113 °C for samples 122 and 188.

Key operational requirements included the use of a backpressure regulator (set to ≥250 psi) to avoid boiling, and a bypass line to equalize pressure across the core during thermal ramp-up. Once thermal and pressure equilibrium was achieved, the bypass valve was closed, and injection began at a controlled rate of 1 ft/day (0.05 cc/min).

Experimental Workflow Summary:

- Core sample 188, preconditioned with Swi = 10%, was mounted in the core holder with Teflon tape and an aluminum sleeve, then pressurized to 500 psi.

- Injection began with FW. Oil production started after ~1 PV, stabilizing at 42.2% recovery. Injection continued for 1.5 additional PV before switching to SW.

- SW injection yielded a total recovery of 54.1%, indicating an 11.9% increase due to smart water effects.

- Finally, SW0NaCl·4SO4 was injected (~5 PV), but no further oil recovery was observed, suggesting a saturation limit in sulfate-induced wettability alteration.

The same procedure was repeated for sample 122, following an initial spontaneous imbibition recovery of 8.11%. The recovery trends are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Summary of oil recovery results for core samples 122 and 188 under different flooding stages, including spontaneous imbibition with formation water (FW), and sequential forced flooding with FW, seawater (SW), and ion-modified seawater (SW0NaCl·4SO4).

The oil recovery results from the core-flooding experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of smart water injection in carbonate reservoirs. For sample 122, initial spontaneous imbibition using formation water (FW) yielded an oil recovery of 8.11%. Sub-sequent forced imbibition with FW increased the total recovery to 38.32%, an enhancement of approximately 30.2%. Further improvement was observed upon injection of seawater (SW), which elevated the recovery to 53.06%, indicating the beneficial effects of smart water via wettability-alteration mechanisms. However, no additional oil was recovered when the injection fluid was changed to ion-modified seawater (SW0NaCl·4SO4).

For sample 188, FW flooding alone achieved a recovery of 42.2%. The use of SW increased oil recovery to 54.1%, an incremental gain of 11.9%, again reinforcing the notion of smart-water behavior. Similarly to sample 122, the injection of SW0NaCl·4SO4 did not result in any additional oil recovery. These results collectively highlight the capacity of seawater to enhance oil recovery, while also indicating that further enrichment with sulfate does not provide additional benefit under the conditions studied.

The incremental recovery obtained when switching from FW to SW can be interpreted in terms of ion-specific wettability alteration and double-layer modification. The high-salinity FW is dominated by Na+ and Cl−, whereas SW introduces lower overall salinity and higher concentrations of SO42− together with Ca2+ and Mg2+. This change in brine chemistry is expected to modify the surface charge at the carbonate–brine interface, promote desorption of polar oil components, and partially shift the rock to-ward a more water-wet state, consistent with the observed increase in oil release. The absence of additional recovery during injection of the sulfate-enriched smart brine (SW0NaCl·4SO4) can be explained by saturation of active surface-complexation sites on the carbonate surface: once Ca2+/Mg2+–SO42− surface complexes occupy the available sites, further increases in sulfate concentration do not significantly alter the double layer or drive extra desorption of polar components.

This ion-saturation interpretation is consistent with pore-scale and surface-chemistry studies. Li et al. (2020) reported that SO42−-mediated desorption of polar com-ponents and changes in adhesion in carbonates reach a plateau beyond a certain sulfate level [16]. Araujo and Heidari (2025) [24] similarly showed that ion-exchange reactions on mineral surfaces are limited by finite site density, while Mansouri et al. (2023) [17] observed saturation behavior when tuning smart-brine formulations with nanocomposite additives. The present core-scale results complement these mechanistic studies by quantifying how such chemistry translates into incremental recovery under reservoir-temperature flooding of preserved carbonate cores.

Because cores 122 and 188 have only modest differences in porosity (18.8% vs. 21.1%) and similar permeability (8–10 mD), the OOIP-normalized recovery values in Table 7 can be directly compared. The observed differences are therefore mainly attributed to brine chemistry and initial wettability rather than to heterogeneities in flow capacity.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study demonstrates that the initial wettability condition of preserved carbonate cores plays a decisive role in determining the efficiency of smart water injection. Both initial water saturation (Swi) and core preservation state were found to strongly affect oil recovery under spontaneous and forced imbibition.

Spontaneous imbibition results showed that increasing Swi from 0% to 10% in core 122 enhanced recovery from ~4% to 8.1% OOIP, indicating a two-fold improvement due to greater capillary contribution. Likewise, the better-preserved core 22–91 exhibited substantially higher recovery at both 25 °C and 70 °C, demonstrating that handling and preservation conditions directly influence measured wettability and, consequently, oil displacement behavior.

Core-flooding experiments confirmed that brine ionic composition governs recovery trends at reservoir temperature (113 °C). Seawater (SW), containing SO42−, Ca2+, and Mg2+, consistently improved recovery relative to formation water (FW), with increases of ~10–15 percentage points for both cores 122 and 188. However, further enrichment through ion-modified seawater (SW0NaCl·4SO4) produced no additional oil, suggesting that sulfate-related wettability alteration reaches a saturation limit under standard seawater concentrations. These findings underscore the need to tailor smart-water recipes to reservoir-specific ion-interaction limits.

Based on these observations, the following recommendations are proposed for future studies and field deployment:

- ▪

- Preserve core samples under controlled, low-exposure conditions to maintain representative native wettability for laboratory assessment.

- ▪

- Include Swi control in smart-water studies to capture capillary effects realistically and quantify wettability-dependent recovery.

- ▪

- Investigate ion-interaction saturation limits (e.g., SO42− surface complexation) using spectroscopic or surface-chemistry tools to refine optimal brine formulations.

- ▪

- Evaluate scaling or compatibility risks associated with ion-enriched brines to ensure safe deployment in carbonate reservoirs.

- ▪

- Conduct pilot-scale validation to translate laboratory findings into dynamic field-scale recovery predictions.

Overall, the results emphasize the importance of a condition-aware mechanistic approach when designing smart-water EOR strategies. Integrating rock preservation, initial wettability, and tailored brine chemistry is essential for achieving reliable and efficient oil recovery in carbonate reservoirs.

Author Contributions

A.K.: Conceptualization; Methodology; Investigation; Validation; Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing. M.P.: Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Visualization; Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We confirm that no external funding was received for this research.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting this study are available within the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mahani, H.; Thyne, G. Low-salinity (enhanced) waterflooding in carbonate reservoirs. In Recovery Improvement; Gulf Professional Publishing: Houston, TX, USA, 2023; pp. 39–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, J.; Barnett, A.J.; Burchette, T.; Wright, V.P. An introduction to “Carbonate Reservoirs: Applying Current Knowledge to Future Energy Needs”. Geol. Soc. Lond. 2025, 548, SP548-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bribiesca Rodriguez, P.; Shaffer, D.L. Wettability alteration and enhanced oil recovery in carbonate porous media by tuning waterflood chemistry. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 3586–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, M.; Pourafshary, P.; Hashmet, M.R. Effect of initial wettability on capillary de-saturation by hybrid engineered water/polymer flooding in carbonate reservoirs. In Proceedings of the 8th World Congress on Mechanical, Chemical, and Material Engineering, Prague, Czech Republic, 31 July–2 August 2022; p. 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.I.; Piñerez Torrijos, I.D.; Zhang, M.; Strand, S.; Puntervold, T. Produced water reinjection with polysulphate additive for enhanced oil recovery from carbonate reservoirs. In Proceedings of the SPE Water Lifecycle Management Conference and Exhibition, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 5–7 March 2024; p. D011S002R003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, C.; Li, J.; Meng, X.; Yang, C.; Chen, Z. A study on the residual oil distribution in tight reservoirs based on a 3D pore structure model. Processes 2025, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buriro, M.A.; Wei, M.; Bai, B.; Yao, Y. Descriptive statistical analysis of experimental data for wettability alteration with smart water flooding in carbonate reservoirs. In Proceedings of the SPE Western Regional Meeting, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 16–18 April 2024; p. D011S003R003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaghani, A.H.S.; Daneshfar, R. Experimental investigation of the sequence injection effect of seawater and smart water into an offshore carbonate reservoir for enhanced oil recovery. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirazi, M.; Farzaneh, J.; Kord, S.; Tamsilian, Y. Smart water spontaneous imbibition into oil-wet carbonate reservoir cores: Symbiotic and individual behavior of potential determining ions. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 299, 112102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafur, N.; Mamonov, A.; Khan, M.A.I.; Soto, A.; Puntervold, T.; Strand, S. Evaluation of surface-active ionic liquids in smart water for enhanced oil recovery in carbonate rocks. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 11730–11742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Kubelka, J.; Piri, M. Wettability alteration by smart water multi-ion exchange in carbonates: A molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 332, 115830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Ghalenavi, H.; Schaffie, M.; Ranjbar, M.; Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. Toward mechanistic understanding of wettability alteration in carbonate rocks in the presence of nanoparticles, gelatin biopolymer, and core–shell nanocomposite of Fe3O4@gelatin. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Zheng, C.; Sheikhi, S. Role of ion exchange in the brine–rock interaction systems: A detailed geochemical modeling study. Chem. Geol. 2021, 559, 119992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, E.; Chen, Z.; Sarmadivaleh, M.; Mohammadnazar, D. Applying low-salinity water to alter wettability in carbonate oil reservoirs: An experimental study. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2021, 11, 451–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fani, M.; Al-Hadrami, H.; Pourafshary, P.; Vakili-Nezhaad, G.; Mosavat, N. Optimization of smart water flooding in carbonate reservoir. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 12–15 November 2018; p. D032S198R002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, Z.; Ayirala, S.; Yousef, A. Smartwater effects on wettability, adhesion, and oil liberation in carbonates. SPE J. 2020, 25, 1771–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, M.; Jafarbeigi, E.; Ahmadi, Y.; Hosseini, S.H. Experimental investigation of the effect of smart water and a novel synthetic nanocomposite on wettability alteration, interfacial tension reduction, and EOR. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2023, 13, 2251–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.S. Mechanisms and Consequences of Wettability Alteration by Crude Oils. Ph.D. Thesis, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Buriro, M.A.; Wei, M.; Bai, B.; Yao, Y. Advances in smart water flooding: A comprehensive study on the interplay of ions, salinity in carbonate reservoirs. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 390, 123140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, B.; Jadhawar, P.; Akanji, L. Surface complexation modelling of potential determining ions sorption on oil/brine and brine/rock interfaces. In Proceedings of the SPE Nigeria Annual International Conference and Exhibition, Lagos, Nigeria, 2–4 August 2021; p. D031S015R002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Y.; Kaufman, Y.; Kristiansen, K.; Howard, A.D.; Cadirov, A.; Seo, D.; Schrader, M.; Roberto, C.A.; Alotaibi, M.B.; Subhash, C.A.; et al. New atomic to molecular scale insights into smartwater flooding mechanisms in carbonates. In Proceedings of the SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference, Tulsa, OK, USA, 14–18 April 2018; Society of Petroleum Engineers: Dallas, TX, USA, 2018; p. SPE-190281-MS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, K.; Andresen Eguiluz, R.C.; Chen, S.-Y.; Ayirala, S.C.; Alotaibi, M.B.; Yousef, A.A.; Moskovits, M.; Boles, J.R.; Israelachvili, J.N. Crude oil/brine/rock interactions during SmartWater flooding in carbonates: Novel surface forces apparatus measurements at reservoir conditions. In Proceedings of the SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference, Virtual, 31 August–4 September 2020; p. D021S031R002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, S.J.; Austad, T.; Strand, S. Smart water as a wettability modifier in chalk: The effect of salinity and ionic composition. Energy Fuels 2010, 24, 2514–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, I.S.; Heidari, Z. Elucidating wettability alteration on clay surface contacting mixed electrolyte solution: Implications to low-salinity waterflooding. SPE J. 2025, 30, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).