Abstract

This study presents a comprehensive review of the viability of hydrogen as an energy carrier for offshore wind energy compared to existing electricity carrier systems. To enable a state-of-the-art system comparison, a review of wind-to-hydrogen energy conversion and transmission systems is conducted alongside wind-to-electricity systems. The review reveals that the wind-to-hydrogen energy conversion and transmission system becomes more cost-effective than the wind-to-electricity conversion and transmission system for offshore wind farms located far from the shore. Electrical transmission systems face increasing technical and economic challenges relative to the hydrogen transmission system when the systems move farther offshore. This study also explores the feasibility of using seawater for hydrogen production to conserve freshwater resources. It was found that while this approach conserves freshwater and can reduce transportation costs, it increases overall system costs due to challenges such as membrane fouling in desalination units. Findings indicated that for this approach to be sustainable, proper management of these challenges and responsible handling of saline waste are essential. For hydrogen energy transmission, this paper further explores the potential of repurposing existing oil and gas pipeline infrastructure instead of constructing new pipelines. Findings indicated that, with proper retrofitting, the existing natural gas pipelines could provide a cost-effective and environmentally sustainable solution for hydrogen transport in the near future.

1. Introduction

Offshore wind energy integration into the electrical grid comes with challenges, particularly with regard to transmission over long distances. As offshore wind farms move farther to sea due to the presence of greater wind resources offshore, the selection of a suitable energy carrier becomes vital to its technical and economic growth.

Current research suggests a distance-dependent transition point where hydrogen emerges as a competitive energy carrier for offshore wind applications. However, Distance from shore is not the only driver that demonstrates viability. Other factors such as electricity prices and the weighted average cost of capital are also important.

Despite these promising results, a comprehensive evaluation of technological readiness and economic viability is needed to determine whether hydrogen can replace electricity as the primary energy carrier for offshore wind systems. This paper addresses this gap by assessing the current state-of-the-art wind-to-hydrogen conversion and transmission technologies compared to conventional wind-to-electricity systems, with particular emphasis on their technological maturity and economic feasibility. Through this comparative analysis, we aim to provide insights into the optimal deployment strategies for offshore wind energy transmission infrastructure.

2. Background of the Comprehensive Review

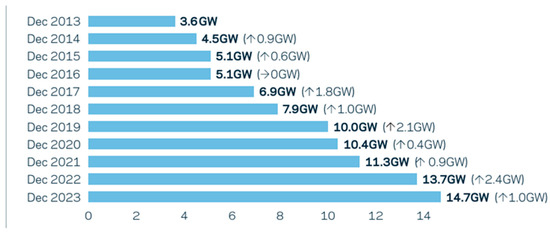

Climate change has brought about a new age of diverse energy sources, including renewables. According to the Crown Estate report for 2023 [1], the United Kingdom has been able to generate enough electricity to power 50 per cent of the homes in the United Kingdom using wind energy. There has also been a steady increase in the establishment of offshore wind farms since 2013, as shown in Figure 1. Offshore wind energy has recently gained more popularity because of its relatively low social impacts compared to onshore wind. Offshore wind energy also allows for the installation of large-capacity wind turbines because there is a much more significant source of wind energy offshore [2]. This rise in offshore wind energy implementation has prompted various studies on wind energy conversion and transmission systems.

Figure 1.

The growth in offshore wind energy from 2013 to 2023 [1].

The conversion of wind energy to electricity for enabling wind energy transmission is one consideration. While alternating current is usually used for wind energy conversion and transmission, the direct current system is slated to aid in harnessing wind energy in far offshore locations, as the alternating current transmission systems become uneconomical after a distance of 150–200 km from shore [3].

Although the erection of several wind farms worldwide has proven successful, some challenges are still noted about offshore wind farm systems. Since the wind farms are stationed far from shore, there are issues like remote system connectivity and the abundant wind resources that can sometimes halt operations or damage equipment [4]. The inclusion of hydrogen in renewable conversion systems can ameliorate the rate at which renewable energy is accepted into the energy space by reducing the need to disconnect the increased renewable electricity from the grid [5].

Conversion and transmission systems are an essential backbone in harnessing wind energy. In addition to the currently used electricity conversion and transmission system, hydrogen is being seen as another way for resilient wind energy conversion and transmission. The conversion of wind energy to clean hydrogen using wind-powered electrolysis can aid in decarbonising many sectors such as transport, heat, and heavy industries. Furthermore, the transmission of hydrogen could potentially reduce the high cost associated with electricity transmission in cables over very long distances [6]. Hydrogen transmission could also reduce the transmission losses associated with electricity transmission. Therefore, hydrogen as an energy carrier can improve wind energy conversion and transmission systems.

The use of hydrogen as an energy carrier for wind energy is still in its development stage and thus is still more expensive than electricity. Table 1 lists some exemplary wind projects utilising hydrogen as an energy carrier at their conception and completed stages.

Table 1.

Exemplar projects using hydrogen as an energy carrier for offshore wind.

3. Materials and Methods

This comprehensive review was conducted using a state-of-the-art methodology. The review aims to synthesise the literature on wind-to-hydrogen systems and wind-to-electricity systems, providing a state-of-the-art overview, and identify the readiness of hydrogen as an energy carrier to replace electricity as a major energy carrier for offshore wind energy. The review also touched on potential technology pathways and economical optimisation options for offshore wind conversion and transmission systems using hydrogen as an energy carrier. The synthesis was performed through searches on ScienceDirect, IEEE, and Google Scholar, beginning in August 2024, using terms such as offshore wind energy, hydrogen, electrolysis, desalination, repurposing pipelines, techno-economic analysis, HVAC, and wind energy transmission and conversion systems. Inclusion criteria for selected articles are

- Focus on wind-to-hydrogen and wind-to-electricity systems;

- Techno-economic studies on hydrogen as an energy carrier for offshore wind;

- Peer-reviewed or industry-recognised sources.

The period selected was from 2005 to 2025. After screening against the listed publications, 129 publications were retained, along with an additional 8 publications obtained from technical reports, such as those from Crown Estate and major demonstration projects on company websites.

The following research questions were also used as the bases for analysis:

RQ1.

What are the current technological advancements in the conversion and transmission of wind energy?

RQ2.

Which energy carrier is more economically preferred relative to the other?

RQ3.

Are there technological advancements that can cut conversion and transmission system cost?

RQ4.

What are the key drivers and assumptions that interpret the cost-effectiveness of hydrogen or electricity as an energy carrier?

4. Comparative State-of-the-Art Literature Review

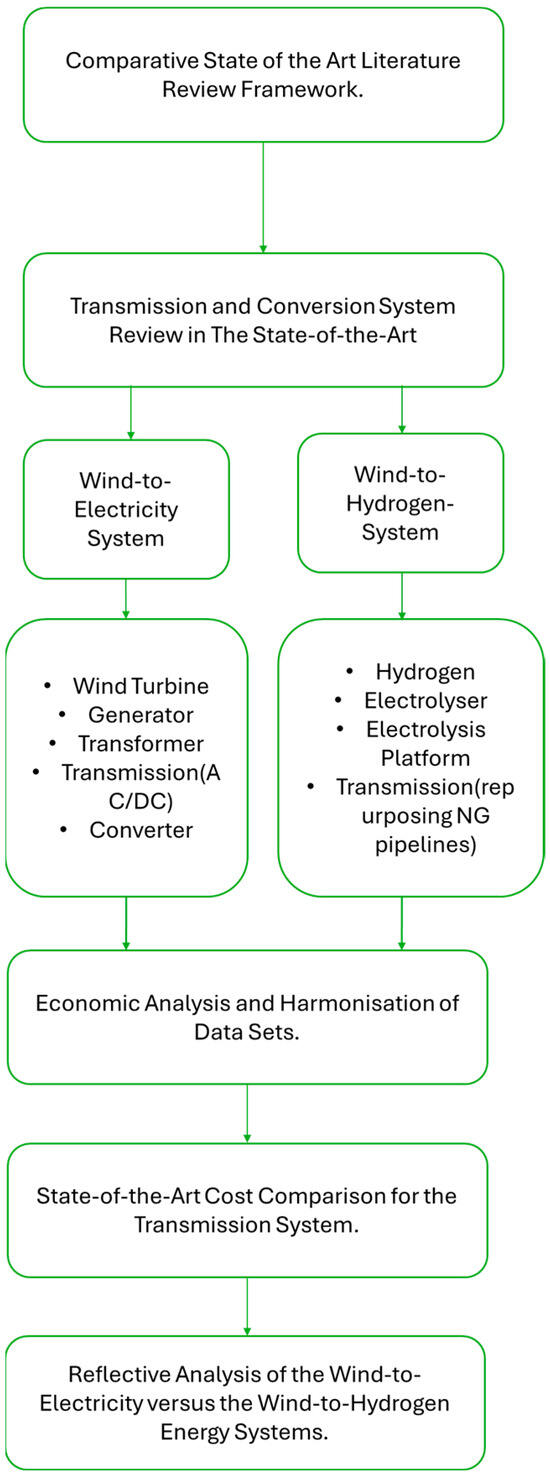

To conduct the comparative state-of-the-art review, a discussion of all the components of the conversion and transmission system for both hydrogen and electricity was carried out as follows. Figure 2 shows the overview of the review.

Figure 2.

Overview of comparative state-of-the-art review.

4.1. Wind Energy Conversion and Transmission System Review

The wind energy conversion and transmission system review for both wind-to-electricity and wind-to-hydrogen is as follows.

4.2. Review of the Wind Energy-to-Electricity Conversion and Transmission Systems

Wind energy conversion to electricity is achieved when the wind rotates the turbine blades, moving the generator’s rotor in the magnetic field, thus generating electricity. Wind energy conversion systems generally comprise wind turbines, gearboxes, electric generators, transformers, and a converter for grid connection. The working principle of wind-to-electricity conversion systems is the capturing of wind mechanical energy to rotate the generator rotor and generate electrical energy. Because wind energy production is hard to predict, studies have been made to understand the nature of wind to aid in the integration of wind turbines into the grid [13,14].

For the grid integration of wind energy, [15] found that this can be configured by using an induction generator, usually linked to the grid without a power exchanger. Machine terminal capacitors were also found to be necessary to combat reactive power. Reference [16] found that the generator used in the wind energy conversion system can be classified based on its rotational speed and its electrical power production. The classification based on the electrical generator’s rotational speed further breaks down into two types, namely fixed-speed and variable-speed systems, while the classification based on the generator’s power production breaks the wind turbine’s capacity into small, medium, and large. Most wind turbines today follow a variable speed scheme and full converters for power production. The fixed-speed conversion systems are mainly used with the squirrel cage induction generators (SCIGs), while the variable speed converters can be used with both synchronous and asynchronous generators. Reference [17] found that fixed-speed systems can attain speeds a little above the synchronous generators, and their electricity output can be directly connected to the grid through a transformer. A capacitor bank is required to account for reactive power issues.

4.3. Review of the Wind-to-Electricity Energy Conversion Systems

The following sub-sections review the components of the wind-to-electricity energy conversion systems.

4.3.1. The Wind Turbine

Wind turbines are classified into horizontal-axis and vertical-axis wind turbines.

- Horizontal-Axis Wind Turbines (HAWTs)

The horizontal-axis wind turbine is featured in one of the largest wind farms in the world, the Hornsea [18]. The horizontal-axis wind turbine (HAWT) has a structural setup where the main rotating shaft of the wind rotor lies parallel to the direction of the wind. A rule of thumb for the HAWT is that more blades will decrease the power factor and the rotation per minute, while solidity will increase [19]. Although employed in many wind farms worldwide, the HAWT has some drawbacks in its structure. While its blade rotation occurs, gravity direction does not change, but inertial force direction changes constantly, which subjects the blade to a continuous alternating load, causing blade fatigue [20]. The HAWT is continually refined by research to optimise its blades’ functioning. Reference [21] employed a systematic approach that uses the particle swarm optimisation (PSO) algorithm in combination with a class or shape transformation method to enhance the convergence speed and accuracy parameters of an NREL WP-Baseline 1.5 MW wind turbine blade. Using a high-performing CFD model and turbulence model, higher wind energy generation was realised for wind speeds greater than 4.5 m/s. This attests to the fact that with constant studies and optimisation, system enrichment can be achieved.

- 2.

- Vertical-Axis Wind Turbine (VAWT)

The vertical-axis wind turbine (VAWT) was first developed in 1930 after the HAWT [22]. The primary axis for the VAWT is perpendicular to the direction of the wind. The wind blades’ working principle classifies the VAWT into drag and lift types. The VAWT is not very economically attractive due to its slow power coefficient and fatigue problems, which stem from the circulation of the aerodynamic loads [22]. However, VAWT has advantages such as long service life, easier operations, and maintenance. A study was performed by [23] to optimise the structural framework of a VAWT by using a combination of finite element analysis and genetic algorithm to reduce the structural mass of the VAWT. Results from this study indicated that the use of carbon-fibre-reinforced plastics in place of glass-fibre-reinforced plastics allows a reduction in the blades and the weight of other structural components. This study shows that material choice and structural design are key influencing factors on the structural mass of the VAWT.

4.3.2. The Generator

Generators are classified into asynchronous (induction) generators and synchronous generators.

- A.

- The Asynchronous (Induction) Generators

- The Wound Rotor Induction Generator (WRIG)The WRIG has its wound rotor windings connected externally using slip rings, brushes, or power electronics equipment. The rotor can be accessed using the slip power recovery configuration, which gives this configuration the advantage of a full generator control using only a fraction of the power required by the power conditioning unit [24]. However, this configuration is disadvantaged by its higher costs compared to squirrel cage induction generators (SCIGs) [15].The WRIG can be configured into the double-fed or the flex-slip induction generator, which is briefly explained as follows:

- The Optislip Induction GeneratorThe Optislip induction generator configuration was introduced in 1990 as a wound-rotor generator configuration with variable rotor resistance connected to the rotor windings. The variable rotor resistance allows a range of dynamic speed control [25].The name Optislip was coined because it has optical converter control on the rotor shaft. Slip rings are not required in this configuration due to optical control presence, which in turn, eliminates the need for brushes and maintenance, thus leading to cost reduction [25]. The disadvantage of this induction generator is that it still requires reactive compensation because of its poor control of reactive and active power.

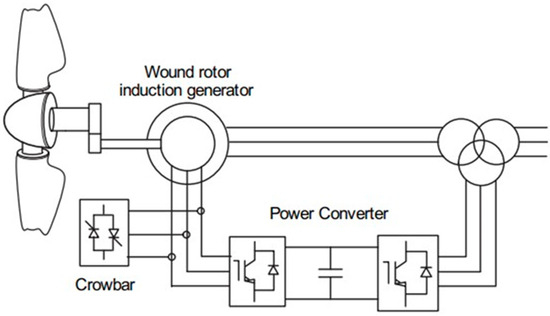

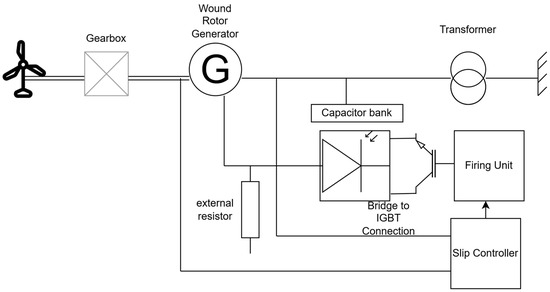

- The Double-Fed Induction Generators (DFIGs)Double-fed induction generators (DFIGs) use partial power converters. The DFIG configuration, shown in Figure 3, requires slip rings, which are considered a disadvantage as they increase costs. The speed and torque control of this type of generator can be achieved by connecting the induction generator to a back-to-back power converter and a static wind channel.Companies that have adopted the DFIG systems are Repower, Sinovel, and 2B Energy.

Figure 3. The DFIG electrical connections for a static wind channel [26].

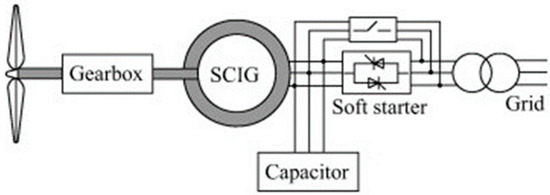

Figure 3. The DFIG electrical connections for a static wind channel [26]. - The Squirrel Cage Induction Generator (SCIG)The SCIG generator is mainly used in smaller and simpler projects, as it has low-speed control and reactive capacitance issues. It is favoured because of its cost-effectiveness, robustness, and simplicity. To reduce its power losses, a capacitor is usually connected to the system, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The SCIG setup [27].The SCIG generator operates based on a reverse induction motor working principle, where the rotor is rotated to exceed the synchronous speed and induce slip in the opposite direction; this action makes the machine convert the mechanical energy into electrical energy.Squirrel-cage induction generators are equipped with full power converters. The use of a full power converter back-to-back can aid in reducing the drawbacks brought on by the presence of multiple gearboxes, and a soft starter can be used to reduce the current rush that occurs during early startup [27].

Figure 4. The SCIG setup [27].The SCIG generator operates based on a reverse induction motor working principle, where the rotor is rotated to exceed the synchronous speed and induce slip in the opposite direction; this action makes the machine convert the mechanical energy into electrical energy.Squirrel-cage induction generators are equipped with full power converters. The use of a full power converter back-to-back can aid in reducing the drawbacks brought on by the presence of multiple gearboxes, and a soft starter can be used to reduce the current rush that occurs during early startup [27].

- B.

- The Synchronous Generators

- Wound Rotor Synchronous Generator (WRSG)This type of generator allows the direct connection of wind turbine generation to the power grid as it enables a fixed rotor speed based on the grid frequency [28].The WRSG is commonly used with large-scale wind turbines. However, because of the harsh offshore environment, maintenance access becomes difficult, giving rise to the use of a permanent magnetic synchronous generator (PMSG) for offshore wind energy conversion as it has a direct drive and no gearbox.

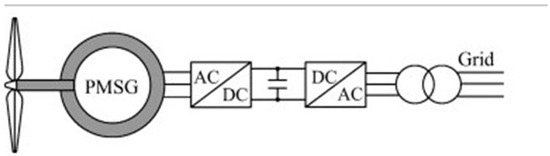

- Permanent Magnetic Synchronous Generator (PMSG)PMSGs are more cost-effective because they do not require an external source of power for creating the magnetic field nor do they need a slip ring. The removal of a slip ring allows for a more compact generator system as shown in Figure 5. The rotor of the PMSG contains permanent magnets that create a constant magnetic field, thus eliminating the electrical energy losses associated with the use of field windings. The PMSG has the advantage of having high-power density, gearless configuration, and no losses at the rotor copper [29]. However, the PMSG does not have a sensor; this fact brings about its disadvantages in terms of reliability and robustness [30].

Figure 5. The PMSG [27].

Figure 5. The PMSG [27].

4.3.3. The Electronic Power Converters

Wind energy generation is unstable due to fluctuating wind speeds; thus, power converters are essential for connecting the wind generation to the grid. Electronic power converters are crucial components in modern wind turbines, enabling the conversion of variable frequency and voltage output from the generator into a stable AC output compatible with the grid. They facilitate variable speed operation, allowing turbines to optimise energy capture across different wind speeds and ensure grid stability. Power converters are the main components used for addressing the wind turbines’ active and reactive power control issues [14].

Because the power converter is placed between the turbine’s generator and the grid, it must satisfy both generator and grid requirements. The responsibility of the power converter on the generator side is to ensure that the turbine rotating speed is regulated such that it is always able to extract the maximum energy from the wind, with a maximum track point consideration [31]. To ensure stable power supply, on the grid side, the power converter must adhere to the grid’s power factor, voltage, frequency, and reactive power [32].

Integrating a power converter with the wind turbine’s generator allows voltage control, active and reactive power control, and power tracking when changes occur in the wind speed and in the load demand.

In harsh environmental conditions, converters with large switch frequencies increase the energy density [33]. The use of the current silicon-based power switches would be less desirable in the future because using a wider range of switching frequencies would foster high reliability (because of increased operating temperature) and high efficiencies.

Since 1980, introducing the power controller into the wind energy production space has been a great advantage. Not only has it reduced the mechanical stress on the blades, generator, and nacelle by controlling the power output and rotational speed, but it allowed grid support while integrating wind generation through controlling the wind turbines [34]. The benchmark method for converter connection and back-to-back converter connection not only makes the state-of-the-art converters used in the industry today, but also makes the perfect benchmark for studies on new converter configurations, such as matrix and multi-level converters [35].

The current market-available power converter can handle increased voltage and current, resulting in less energy losses and a much more reliable device.

Other power control devices that are commonly utilised with wind turbines include the following:

- Soft starters: A soft starter is an electrical device that gradually increases the voltage supplied to an electric motor or a generator during startup to reduce the inrush current. Soft starters are used in wind turbines, particularly in fixed-speed turbines, to allow smooth synchronisation of the generator with the grid and limit rush of current during startup, thus preventing large voltage disturbances and reducing mechanical stress on the turbine’s components. Figure 6 shows a soft starter configuration with the advantage of being cheap and simple in terms of construction and it does not require a synchronisation device. However, one of the challenges is that the turbine must operate at a fixed speed. In contrast, the wind speed is not fixed; it requires a rigid grid for it to operate stably, and because of the high mechanical stress associated with the wind gust, causing torque pulsations on the drive train, the soft starter might need a high-cost mechanical construction to withstand this stress [35].

Figure 6. A soft starter configuration.

Figure 6. A soft starter configuration.

- Capacitor bank: This component sends reactive power to the induction generators of wind turbines [36]. Wind turbines, especially those using induction generators, often require reactive power to maintain voltage levels and ensure stable operation. Capacitor banks help smooth out voltage fluctuations associated with wind variations by absorbing or releasing reactive power as needed. Switching the capacitor banks in and out as needed provides reactive power compensation, thus helping to maintain a stable voltage profile at the wind farm’s connection point to the grid. Capacitor banks also allow a better power factor, meaning the wind farm draws less current for the same amount of absolute power, thus reducing transmission losses and improving overall system efficiency.

4.3.4. The Transformers

Wind turbines utilise transformers to step up the low-voltage electricity generated by the wind turbine to high-voltage electricity suitable for transmission over long distances to the electrical grid. These transformers are crucial for both onshore and offshore wind farms to ensure efficient power delivery. In offshore wind farms, before the generated electricity is sent to the converter for HVAC or HVDC electricity transmission, its low voltage of 0.69–1 kilovolts is first stepped up to 33–66 kilovolts. After collection, the voltage is further stepped up to 220 kV by a larger transformer at an offshore substation to aid in transmission through HVAC or HVDC submarine cables.

During transmission over long distances, a tap-changing transformer is fitted into the offshore converter station to help with voltage control because of the variations in voltage. The tap-changing transformer controls voltage by changing the winding ratio, which in turn allows for the control of the angle of fixing and offsets the voltage variations. The tap change ranges from 25 to 33% [37]. The transformer tap ratio also addresses over- or under-modulation issues that the converters have; these issues have a negative effect on harmonic performance [38].

4.4. Review of the Wind-to-Electricity Energy Transmission Systems

The transmission of wind farm electricity can be performed using one of the following transmission systems.

4.4.1. The Alternating Current (AC) Transmission System

The AC transmission system is a common technique for distributing electrical power in large-scale wind energy installations. The voltage of these installations typically ranges from 36 to 66 kV [39].

Based on the transmission distance from offshore wind farms to onshore, a transformer must be installed at the wind turbine’s nacelle to increase the voltage of the produced electricity to the required transmission voltage, which can be up to 600 kV [40]. The presence of such heavy-duty transformers makes the wind turbine design bulky.

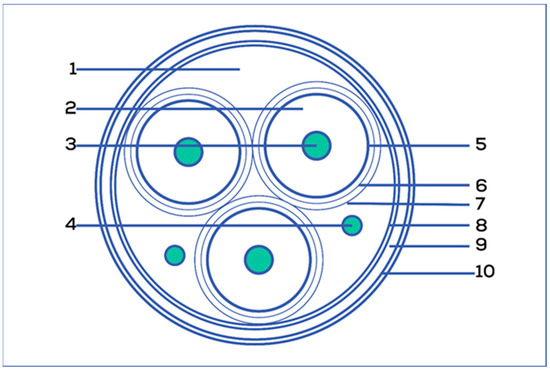

The electricity generated by the offshore wind farm is then transmitted to shore via high voltage submarine cables. A high-voltage submarine cable is made of three cores, outer insulation layers, and a protective armour to protect the electricity carrying cores from the seawater. To stop the seawater from leaking in, each core is composed of water-blocking copper wire with conduction strands, conductor screens, polyethene-insulating layers, lead alloy sheath, corrosion protection, insulation, swelling tape, and a filling layer as shown in Figure 7. The outer cable is made up of a bedding, a layer of armour, and an outer serving; there is also a fibre optic layer to allow for monitoring and communication between the subsea cable and the wind turbine. Figure 7 gives a pictorial view of the cross-sectional area of a typical submarine cable.

Figure 7.

Cross-sectional area of a submarine cable. Conductor (1), polyethene-insulating layer (2), swelling tape (3), metal and pe sheath (4 and 5), filling layer and wrapping tape (6), inner sheath (7), armour layer (8), outer sheath (9), and armour layer (10).

High-voltage alternating current (HVAC) submarine cables are susceptible to issues related to reactive capacitance. The resulting charging current will limit the cable’s ampacity for active power transfer, increase active power losses, and increase the voltage along the line. This charging current is voltage/distance-dependent, so switching a long HVAC cable can cause overvoltage to the grid if not properly compensated [41].

To aid in the regulation of AC cable reactive capacitance power, the following techniques can be used:

- Reactive power compensation, also known as cable compensation, is a technique for controlling reactive capacitance. It involves strategically placing reactive power devices across the AC submarine cables to enable the absorption of reactive power and counter the capacitive effects on the cable [42]. The costs for reactive compensation are predominantly voltage dependent; compensation devices at higher voltages are more expensive than those at lower voltages.

- Smart cables, also known as electronic power cables, manage reactive capacitance issues in AC transmission cables. This technique utilises converters and inverters to regulate reactive power flow as needed, enabling the system to be adjusted in real-time [43].

4.4.2. The Direct Current (DC) Transmission System

In 1954, ABB created the first real functional direct current (DC) transmission system; this year also marked its commercialisation, after being only in research investigations [44].

Wind turbines produce AC electricity. Therefore, to enable the use of DC transmission cables, converters must be used to convert this wind-produced AC electricity into DC for transmission; in turn, inverters are required at the onshore point to invert this DC to AC for enabling its grid integration.

The low electricity losses in long-distance HVDC transmission compensates for its high investment costs. Thus, long distance transmission of offshore wind power is preferred to be performed via DC because of the reduced power losses.

The HVDC will benefit from a new technology known as the voltage-sourced converter, which uses a multi-level converter rather than two-level converters. In power transmission systems, the multi-level converter offers improved performance and increased control [45].

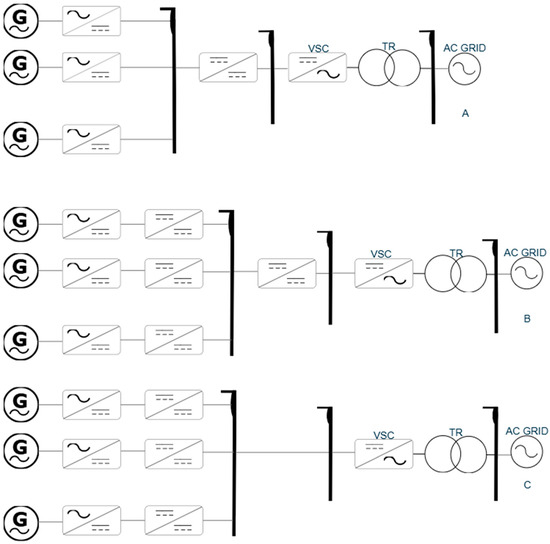

4.4.3. The Collection and Transmission Setups

- A.

- The DC Collection for DC Transmission

Figure 8A shows the DC collection of the wind-farm-generated electricity after being converted from AC to DC. This DC collection system employs a DC-DC converter to step up the voltage of the DC electricity to the transmission level. In this setup, the use of step-up AC transformers is eliminated, thus making the design less complex than that of the AC collection system. This collection system also has the advantage of less losses because of the shorter connection distances within the wind farm. The absence of a transformer would reduce the cost of the DC collection and DC transmission setup [46].

Figure 8.

Setup of the DC collection and transmission systems (A) DC-DC collection and transmission (B) Two step DC-DC collection and transmission (C) Direct DC-DC collection and transmission.

The use of this one-stage DC-DC converter method is limited because of the need for high voltages in long-distance transmission; therefore, a two-step DC-DC converter can be used as seen in Figure 8B to realise this. The use of this DC-DC high-power converter method can significantly reduce the size and weight of the entire system. This reduction will further make the system installation and construction processes more cost-effective. Although the use of an extra DC-DC converter will lead to higher costs and little extra losses, this remains a much better setup because it allows the individual control of voltage [46].

Figure 8C illustrates the DC collection method, which utilises only DC-DC converters directly connected to each wind turbine.

- B.

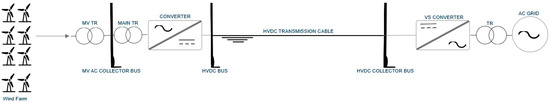

- The AC Collection for DC Transmission

The wind turbines are arranged in clusters, and then AC voltage at variable frequency and magnitude is produced by wind turbine generators. The AC voltage must be processed because the grid is at a fixed frequency and voltage [47]. A direct current link converter consists of a generator, grid-side rectifier, and inverter to process the voltage. In the UK, the voltage is typically stepped up to 690 V using a transformer; the voltage is then further increased to the required level by the collection box, as shown in Figure 9. The voltage is further stepped up and then transmitted through to the HVDC converter for transmission. The DC power is converted back to the AC at the substation so that it can be fed to the grid.

Figure 9.

Setup of the AC collection and DC transmission system.

4.4.4. Comparative Analysis of the AC and the DC Collection and Transmission Systems

In comparison to the AC transmission, DC transmission has many advantages. The cable used for the DC transmission is more cost-effective than that used for AC transmission because AC transmission cables require reactive capacitance devices [48]. The reduction in the DC transmission system’s reactive capacitance compared to that in the AC transmission system provides the advantage of relatively lesser energy losses [49]. Compared to the AC line, the DC transmission line can transmit electricity over long distances of about 3000 km, while the AC line has only been used for distances of about 1049 km [44]. The DC transmission line is compact because it requires fewer cables. For both overhead and underground transmission, the DC cable also has the advantage of requiring less right-of-way space [44].

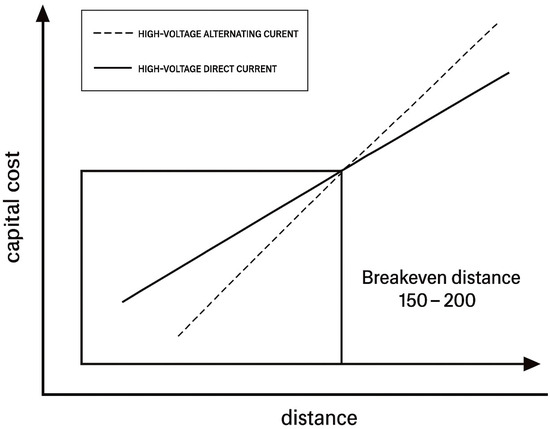

Despite the positives of DC transmission, there are challenges when it is employed in the transmission of offshore wind electricity to the power grid because of the need for AC/DC and DC/AC conversion systems. A break-even distance of 150 to 200 km is always to be considered for the selection of AC transmission lines over DC [50]; this is because AC lines beyond this distance become an economically unwise decision. The DC line only becomes economically wise beyond this break-even distance.

DC transmission lines are the only option for linking the asynchronous power systems of different countries [51]. Countries such as the United States, France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Japan have utilised it as an asynchronous link [51].

Alternating current lines are easily implemented for multiterminal lines if the break-even distances are considered [51]. They are much more prevalent worldwide than direct current lines.

4.5. Review of the Economics of Wind-to-Electricity Energy Conversion and Transmission Systems

The total cost of a project is calculated based on initial investment, as well as operation, maintenance, and decommissioning costs.

4.5.1. Economic Review of the AC and the DC Transmission Systems

- A.

- The Capital Costs

The capital cost for a typical wind farm transmission line is informed by whether AC or DC is used in transmission, which is selected based on distance.

Table 2 demonstrates the capital cost breakdown for AC transmission systems. The capital cost of AC transmission systems involves the costs of the cable trenches, submarine cables, offshore transformers and substations, shunt reactors, and mechanical switchgear. Depending on the distance from shore, the cost of reactive compensation devices is also factored in, and the cost of the submarine cable is affected accordingly.

Table 2.

The capital cost breakdown for AC transmission [38].

Table 3 demonstrates the capital cost breakdown for DC transmission systems. The capital cost of a DC transmission system involves the same costs as those of an AC transmission system, except that the DC system does not require reactive compensation devices; instead, it requires offshore converters and onshore inverters.

Table 3.

The capital cost breakdown for DC transmission [38].

When costing the transmission system for a wind farm, distance dictates the use of either an AC or a DC transmission system. As previously stated, and as shown in Figure 10, the break-even distance for using AC transmission is 150–200 km; afterwards, DC transmission becomes much more economically efficient to utilise [38].

Figure 10.

The break-even distance (Km) for using the HVDC transmission system [38].

- B.

- The Operating and Maintenance (O&M) Costs

Operation and maintenance costs of the transmission system involve energy losses because it influences overall energy system efficiency and profits. The occurrence of transmission losses might make a wind farm fall short of the required energy, and this could accordingly push more production, which could cause the turbine to wear and tear. Furthermore, transmission losses translate to energy loss, reducing the profits made from the energy accrued. Higher transmission losses would mean higher OPEX. Costs like equipment maintenance, docking operations of skilled workers, and equipment lifting during maintenance or repair exercises are also considered for operation and maintenance costs. Operation and maintenance costs can be further broken down into fixed costs and variable costs. Fixed costs are non-negotiable costs, such as insurance, health and safety costs, and checks and tests on equipment, while variable costs would be costs that come up while the wind farm is in operation, such as equipment replacement and possible unscheduled interventions [52].

A study on the economics of using HVAC, low-frequency alternating current (LFAC), and HVDC transmission systems for a 100 MW and 300 MW offshore wind farms located in the Aegean Sea at distances ranging from 50 to 200 km from the shore showed that the transmission losses increase as the capacity factor and line length increase [53].

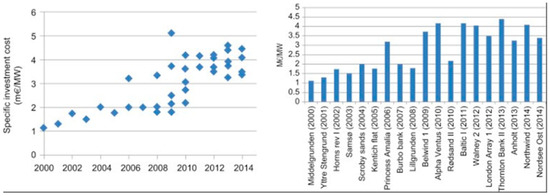

4.5.2. Economic Review of the Offshore Wind-to-Electricity Conversion System

The capital cost to construct offshore wind farms is very high. Currently, building offshore wind farms costs 50% more than building onshore wind farms [54]. Offshore wind farm structures involve higher investment costs due to the complicated logistics associated with their construction. An offshore wind farm, compared to a similar-sized onshore wind farm, is around 20% more expensive in terms of tower, foundation, turbine, installation, and grid connection. The advantage of the availability of high wind resources offshore has pushed the offshore wind farm sites to deeper water depths and far distances from shore. This has hiked the prices of offshore wind farm installations. Figure 11 shows how the installation costs of offshore wind farms have grown over the years due to the increase in their distance from the shore and the consequent increase in water depths.

Figure 11.

Trend of offshore wind farm investment costs [54].

The difference in the wind farms costs can be explained by differences in their age, turbine size, and water depth. The electrical installation costs for offshore wind farms involve collection, integration, transmission, and reactive power compensation system costs. The costs of the offshore substation and other electrical devices are also included. The wind turbine cost includes the cost of the turbine tower, rotor (hub and blades), main shaft and frame, claw and pitch system for stability, turbine transformer, brake system, nacelle house, and gearbox and connector cables. There is also the installation cost for the foundation, cables, and electrical systems. The installation costs also include the transport costs, chartering of vessel costs, and labour costs. The cost of the turbines covers up to 40–60% of the entire offshore wind project cost, making it the most expensive element of the project [55]. Installation costs are usually combined with foundation and cable costs, accounting for an estimated quarter of the investments [56]. The foundation is also cost-intensive and takes up to 20% of the investment [56]. The raw materials, including iron, fibreglass, steel, etc., and the labour costs comprise about a third of the total investments [56]. It is, however, essential to note that the investment costs for different projects vary; so for example, while the wind turbine system investment in both Horns Rev 1 and the Rodsand 1 wind farm projects in Denmark takes up 49% of the total investment costs, the wind turbines at the south of the Oresund bridge, 8 km off the coast of Sweden, take up 51% of the investment. These offshore wind farm projects are more expensive than the onshore projects because of the foundations needed at sea depths. The Horns Rev farm is located approximately 18 km from the shore, which accordingly raises the cost of transporting the turbines to such a remote location offshore.

The collection system starts with the wind turbine’s transformer, which steps up the voltage from about 690 V to 25.40 KV in typical wind turbines [57]. This voltage range is preferred because of the transformer size and the availability of standardised equipment such as switchgear, cables, and monitoring equipment at competitive prices. After the transformer steps up the voltage of the collected electricity, medium voltage submarine cables, buried under the seabed, carry this offshore wind electricity to the onshore grid substation. Due to different manufacturers, the cost of submarine cables is highly variable. A study conducted by [58] reveals that some manufacturers charged twice the prices of others due to factors such as cable demand at the time, inflation in commodity prices, setup costs, and manufacturers’ expenses for tools and company-specific policies.

4.6. Review on the Wind Energy-to-Hydrogen Conversion and Transmission Systems

4.6.1. Hydrogen Overview

Hydrogen is receiving significant recognition as a future energy source. Hydrogen is clean, very low in density in its gaseous state (0.089 kg per cubic metre), and has a high heat of combustion under standard conditions (285.8 kJ/mol) [58,59]. It is colourless, odourless, and tasteless.

Hydrogen is highly flammable, with a minimum ignition energy lower than combustible gases like propane, butane, and methane. Its low density and high flammability make the chances of leaks and subsequent combustion in the presence of a fire source very likely, thus necessitating stringent safety protocols. Hydrogen is not easily ignited when released into the atmosphere; it ignites when it is diffused in an enclosed space. When hydrogen is ignited in an enclosed space, an ignition source can cause the gas to burn quickly. Hydrogen gas, in comparison to natural gas (NG), is more reactive, and this easily reactive nature could result in a much more severe explosive incident [60].

Compared to known fuel sources, hydrogen’s density is the lowest (0.899 g/cm3). Hydrogen is preferred in the fuel cell space due to its high density and light weight. Hydrogen possesses the highest energy content per unit weight (120.7 kg/cm3) compared to gases such as natural gas and propane.

4.6.2. Hydrogen Production

Hydrogen production can be performed using several energy sources, and this dictates its colour coding. The black hydrogen produced from coal gasification and the grey hydrogen produced via steam reforming of natural gas or methane are both associated with high carbon emissions. Blue hydrogen is produced from steam reforming of methane or natural gas while utilising carbon capture and storage to negate emissions with 85–95% efficiency [61,62]. Green hydrogen is produced by powering an electrolyser using renewable energy sources. Green hydrogen is associated with zero-carbon emissions, making it ideal for the net zero energy transition. Pink hydrogen produced using nuclear energy in powering electrolysis also has zero carbon emissions, but it is not well commercialised yet.

4.7. Review of the Wind-to-Hydrogen Energy Conversion Systems

The Wind-to-Hydrogen Energy Conversion (Electrolysers)

The offshore wind-to-hydrogen energy conversion system uses wind energy to power the electrolyser to produce clean hydrogen from water electrolysis. This hydrogen is then used as a clean energy carrier for offshore wind energy.

The cost involved in the electrolysis process involves CAPEX and OPEX, where the CAPEX primarily involves the material and fabrication costs of the electrolyser. The OPEX involves the cost of electricity used to run the electrolyser and the electrolyser’s efficiency. The electrolyser’s complete system efficiency depends on how well it is integrated with the wind turbine and the response times of the turbine and the electrolyser. For a fully efficient electrolyser system, the scale of hydrogen to be created needs to be considered, as well as the activation and ohmic and mass transport overpotentials.

The overpotentials are very important in the electrolyser operation as they guide its efficiency. For example, a reduction in the energy efficiency of a fixed electrolyser cell area can be linked to increased activation and ohmic losses. This example highlights the fact that for the electrolyser efficiency to remain stable, the load must be stable, which is not practical when powered with wind due to the nature of wind energy fluctuations. A balance between efficiency and current density is required for optimum hydrogen production [63]. In Table 4, the SOEC has the lowest overpotentials because of its high operating temperature. All electrolyser types favour lower current densities to avoid high overpotentials, though there is no single optimal value. Optimally selecting the key design features for each electrolyser type would reduce overpotential issues and enable prime hydrogen production via electrolysis. For example, the PEM electrolyser requires low current densities and high flow rates to keep the mass transport overpotential low, but higher current densities reduce overall capital costs [64]. In terms of understanding the key trade-offs associated with design parameters, they are system dependent. An understanding of the system’s peculiarities is vital for determining which design parameters to allocate and how they relate to CAPEX and OPEX.

For electrolyser system control strategies, regulating system parameters is required to optimise hydrogen production. The main electrolyser control parameters are temperature, pressure, current, frequency, and purity control [65]. These values aid in the safe, efficient, and pure production of hydrogen. For off-grid wind energy integration with hydrogen, two main control strategies are currently employed. They are briefly explained below:

- Simple start-and-stop strategy: This control strategy is as simple as its name suggests. It is achieved by arranging electrolysers in an array. The input power supplies energy to the first electrolyser until the electrolyser has optimal energy, at which point the excess power is sent to the second electrolyser. As the power from the renewable energy source continues to increase, it is allocated across the electrolyser array. This system remains in effect until a power overload occurs, at which point the electrolysers enter power overload mode. To prevent the electrolysers from continuously operating in power overload mode, the system periodically turns them off. During a low-wind period, when there is insufficient power to run all the electrolysers, they will shut down sequentially and come back online in the same order when power becomes available. The main disadvantage of the start-and-stop control system is the potential for preferential electrolyser wear, as some electrolysers would always be powered. In contrast, others would only receive power during periods of high renewable energy.

- Rotational Strategy: This strategy balances the issue of preferential electrolyser overload. Control is achieved by dynamic power allocation. The electrolysers are allocated power in time steps (Trs), so at every Tr, the electrolyser power allocation priority order changes. This time step method is also used when allocating overload power.

Electrolyser control strategies can also help reduce hydrogen production costs. Control can be achieved by modelling wind energy availability to forecast hydrogen production based on future conditions and estimating operation conditions to enable the selection of prime design parameters using a heuristic approach to consider all possibilities [66].

An increase in hydrogen output from the electrolyser would reduce the CAPEX and increase produced hydrogen mass; this increase would adversely affect the energy efficiency of the electrolyser and increase the OPEX [67]. Therefore, a balance is required, as there is the risk of paying more during electrolyser’s lifetime due to issues such as heat management issues and ohmic losses [67].

The three most popular types of electrolysers are currently alkaline, polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM), and solid oxide electrolysers. The alkaline electrolyser is the most commercialised of the three but has some system inefficiencies that the PEM electrolyser can rectify, such as achieving a higher current density at the same efficiency as an alkaline electrolyser. A high current density is desired because an electrolyser with a low current density would require more stacks, resulting in higher installation costs but with lower efficiency. Therefore, a balance is important between technology and costs. The solid oxide electrolyser is still in its research phase [68].

Table 4.

Electrolyser overpotential ranges.

Table 4.

Electrolyser overpotential ranges.

| Electrolyser Type | Current Density | Voltage at 1 A/cm3 | Overpotentials | Design Parameters That Affect Overpotentials | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEM | 0.01 A/cm2–5 A/cm2 | 1.8–2.0 v | The PEM electrolyser is mainly affected by ohmic, mass transport, and activation overpotentials. | Current density, charge transfer processes, electrical resistance, and reactant flow rates. | [69] |

| AEL | 1.8 A/cm2–5.0 A/cm2 | 1.88–1.92 V | The AEL electrolyser is mainly affected by the ohmic overpotential and activation potential | Operating temperature and pressure, electrolyte calculation, and membrane resistance. | [70,71] |

| SOEC | 0.3 A/cm2–1.5 A/cm2 | <1.3 V | The SOEC electrolyser is mainly affected by electrolyte, electrode, and ohmic overpotential. | Electrode material, electrolyte material, cell and stack design, impurity mitigation, buffer layers, and microstructure engineering. | [72,73] |

- A.

- The Electrolysis Platform

This system comprises an offshore electrolyser (for energy conversion), a desalination unit (if using seawater), separators, and hydrogen storage. The electrolyser stacks can be directly connected to the wind turbines at a higher cost; however, this expensive connection creates an avenue for flexible maintenance and repair and flexible separation of smaller stacks from the wind farm load, allowing the minimum load requirements to be met. Another way, called the centralised method, is to connect all the wind turbines to the electrolysis plant, and this potentially could reduce costs and foster a balance in the electrolysis plant.

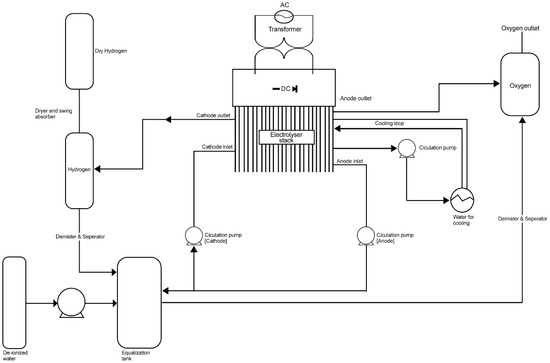

Figure 12 shows the different components that make up an offshore hydrogen production plant which comprises electrolysers, separators, pumps, heat exchanger, and hydrogen storage. The input power to the electrolyser stacks affects the electrolyser’s hydrogen production output because when the electrolyser input power is low, there is a record of significant loss in hydrogen production [74].

Figure 12.

Electrolysis platform [75].

When using the alkaline electrolyser, a large amount of potassium hydroxide will be required to recirculate during electrolysis, and a large separation tank is needed to create hydrogen in large quantities. While the alkaline electrolyser might overheat, requiring the flow of electrolytes to address the overheating issue, the polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) electrolyser may find it harder to regulate intense heat because it has a higher operating current density.

However, the PEM electrolyser makes hydrogen of the highest purity at very high pressure, thus eliminating the need for compression and further purification units [74].

While the electrolyser utilises DC power, wind turbines mainly produce AC power, which is adjusted by a transformer before rectification to feed the electrolyser voltage and cooling and drying systems. The voltage system helps to control internal electrolyser resistance and the thermodynamic potential of water [75]. The cooling system, located left of the electrolyser platform in Figure 12, helps cool the electrolyser stacks and drying system located on the left of Figure 12, just below the dry hydrogen, which helps to purify the hydrogen further because water vapour is formed, and the water is dragged through the membrane with hydrogen. Gravity separation drums are sometimes placed on the electrolyser to facilitate hydrogen and water separation [75].

The hydrogen produced by the electrolyser often requires storage at up to 30 bars, so compression is needed after production. The produced hydrogen may temporarily be stored in metal steel tanks before being injected into a pipeline network or shipped for transportation. Before being transported, hydrogen might require further dehydration for purity and pressure swing absorption.

- B.

- The Desalination Unit for Sea Water

While the use of sea water would be advantageous in terms of cost and convenience offshore, its desalination is essential because if the sodium chloride is not removed, the electrolysis can be negatively affected because the reduction in oxygen evolution will compete with the chlorine to oxidise at the anode; this would reduce oxygen evolution and allow for the oxidation of chloride ions in place of water, thus causing electrodes corrosion at the anode side of the electrolyser [76]. The corrosive nature of seawater is also another primary reason why a desalination process is necessary. The membrane and the electrolyser can also be fouled by seawater because it contains many biological and dissolved solids, which can cause corrosion in the electrolyser system if left unchecked. Finally, with seawater pressure, exchange can occur between the seawater and the proton exchange membranes, giving rise to low conductivity issues. This issue is also replicated in the anion exchange membrane electrolysers.

The use of reverse osmosis for water desalination has reduced the cost involved in seawater desalination [74]. In the 1850s, when desalination was first introduced, cost was not the focus as innovation was needed to provide fresh water on ships. As the years went by and further innovations were made into desalination technologies, the desalinated water prices were reduced to around 0.5 dollars per cubic metre, where production took place at large-scale plants [77]. Prices also varied based on location and the desalination technology used was charged at one dollar per cubic metre [77]. However, not all desalination technologies can be applied to harsh offshore environments.

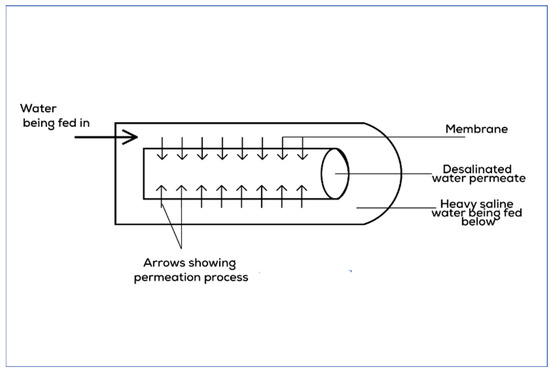

The membrane for the reverse osmosis process shown in Figure 13 would require pretreatment because of fouling from water and biofouling [78].

Figure 13.

Reverse osmosis of desalination unit system.

Fouling reduces the desalination membrane’s life, further increasing maintenance costs and operation shutdowns. An excellent way to minimise the downtime due to fouling is to store fresh water each time a desalination process is completed, anticipating a possible shutdown.

The electricity required to power the desalination unit to produce one cubic metre of water is 3.4 kwhm−3 [74]. The added electrical needs of the desalination unit might increase the process’s cost.

Cost reduction in an offshore desalination unit can be achieved by efficiently designing the intake, drain, and filtration system to reduce the need for pretreatment [79].

When considering the implementation of desalination offshore to produce hydrogen, a vital consideration is to match the costs of offshore and onshore reverse osmosis desalination and make them comparable. As reverse osmosis technology is already proven and mature, there is a need to understand the cost implications when integrated with offshore wind electrolysis. It would also be necessary to consider the disposal of the separated salt ions and their potential environmental impact.

- C.

- The Transformers

A typical electrolyser can operate at high megawatts per unit, but the voltage to start it up is low; thus, a transformer is required to step down the voltage coming from the voltage bus, and then, if needed, a rectifier is used to convert this AC to DC for feeding the electrolyser.

- D.

- Pumps, Compressors, and Separators

Pumps are essential for the circulation of electrolytes used in electrolysers, deionised water, and for cooling. They are crucial to the process of electrolysis, and they help reduce system issues that may arise from overheating using the cooling fluid.

Separators are used to separate the produced hydrogen gas from water using gravity force. The separators utilised are usually referred to as gravity systems. Separators are also responsible for stopping potassium hydroxide electrolysis in the alkaline electrolysers.

Finally, the compressors come in. For hydrogen storage to be possible, it must be compressed from the atmospheric pressure to the pressure required for either storage or transportation. An example is hydrogen compression by 6–14% for storage. For pipeline transportation, compression would range from 30 to 100 bars in pressure; and for fuel cells usage, a range of 700 bars would be required [80].

4.8. Review of the Wind-to-Hydrogen Energy Transmission Systems

There is considerable potential for using the existing oil and gas transmission pipelines in the transmission of the hydrogen produced offshore. The reuse of such infrastructure for clean hydrogen fuel transmission instead of fossil fuels will benefit the environment. A research study by [81] has shown that 48 of the platforms present in the Malaysian Sea have far exceeded their viable lifetime. The repurposing of such infrastructure instead of recycling is a process that would reduce CO2 emissions. For example, 811 megatons of carbon dioxide emissions can be avoided if the recycling of 475 megatons of steel from decommissioned oil and gas platforms does not take place.

The transportation of hydrogen as an energy carrier for offshore wind via the repurposed existing pipeline such as Energie park Bad Lauchstadt is an economical and environmentally sound alternative. The cost for repurposing an existing pipeline is €0.2–€0.6 M/km compared to building a new hydrogen pipeline at €1.4–€3.4 M/km [82].

Many of the current studies involve injecting hydrogen as a mix with natural gas because of the nature of hydrogen, which can adversely affect metals by causing them to be brittle.

To test the suitability of the prospective natural gas pipeline for repurposing, the natural gas pipeline must go through rigorous testing and tolerance assessment to ascertain whether the pipeline is a suitable candidate for repurposing. To test the engineering tolerance of the pipeline steel, non-destructive testing is carried out to ensure pipeline integrity. Tests such as fracture, fatigue, and engineering critical assessment to assess the pipeline and the weld must be carried out. Minimum design criteria as standardised by ASME B31.12 must be met [83].

Hydrogen embrittlement is a significant issue in hydrogen transmission via pipelines [84]. This issue arises because hydrogen atoms can diffuse into metals, destroying metal bonding. The bonding disruption creates an avenue of weakness in the pipeline structure, which eventually can lead to cracking, creating safety concerns as hydrogen is highly flammable in an enclosed space. This issue can also defeat the purpose of reducing transmission losses in the long run. To combat this cracking issue, pipeline bundles can be used instead of using just one pipeline; however, this solution is also challenging as it is not easy to implement because of restrictions such as pipeline diameter. Inhibitors have also been known to be used to reduce the effects of embrittlement; however, this solution comes with the reduction in hydrogen purity, and the inhibitors can potentially make the gas toxic [85]. To avoid hydrogen embrittlement issues according to the ASME pipeline standard, a small diameter X52 steel with 0.562 thickness should be used. Some natural gas pipelines made with X52 steel could be good candidates for retrofitting as they meet some of the material specifications [86].

The use of the NG pipelines for hydrogen transportation has grown over the years, with some implementations such as the Gasunie consumer hydrogen pipeline located in the Netherlands, which employs a 12 km NG pipeline spanning from Dow Benelux to Yara. The pipeline was refurbished to utilise the hydrogen produced as a byproduct from Dow’s cracking plant and used by Yara as feedstock pipeline. Refurbishment was conducted by disconnecting the pipeline and cleaning all the natural gas residue using a pipeline pig. Further modifications were performed to the pumps, valves, compressors, and control units to accommodate hydrogen. The pipeline and compressors were pressure tested, and finally, hydrogen was introduced into the pipeline. After repurposing the natural gas pipeline in 2012 for hydrogen transportation, four kilotons of hydrogen are successfully transported every year. The use of hydrogen in place of natural gas as a feed stock has led to the saving of 10,000 tons of . Another project worth mentioning is the wind-to-gas project in Germany, which employs hydrogen as an energy carrier for wind energy. An alkaline electrolyser is used to generate the hydrogen from the excess in wind energy during high-wind periods. The created hydrogen is then transported as a blend of hydrogen and natural gas at a pipeline operating pressure of 55 bars [86].

While most of the NG pipeline repurposing studies in Europe are in their final stages, Italy has seen great potential in repurposing their NG network pipeline to carry 100% pure hydrogen [82]. Advancements in repurposing natural gas pipelines for hydrogen use will be very advantageous for the transmission of energy from large wind farms located near large decommissioned natural gas pipelines.

Table 5 shows some analysis of assessing the viability of repurposing natural gas pipelines. The consensus is that repurposing pipelines are a cheaper option for hydrogen transmission, but consideration should be given to safety implications of repurposing and the material peculiarities of each pipeline being considered for repurposing.

Table 5.

Key assumptions, key drivers, and costs for pipeline repurposing.

Compressor Station, Metering Station, and Valves for Repurposing Existing Pipelines (Review)

- A.

- The Compressor Stations

The flow of gas over a distance is facilitated by a pressure differential, and the flow is characterised by higher to lower pressure [91]. Compressor stations are therefore used to keep the flow of gas through pipelines going at a steady pressure to avoid issues such as the Joule Thomson effect [92]. The strategic placement of compressor stations at intervals along a pipeline channel is essential for the smooth flow of gas in pipelines. Centrifugal and reciprocal compressors are the main types used [93], and the utilised compressor type depends on how much gas needs to be transmitted.

The compressor stations attached to the existing natural gas pipelines are typically centrifugal because it is characterised by high flow rates and a lower pressure limit relative to the reciprocating compressor; however, the reciprocating compressors are much more suited for hydrogen transportation because they allow for higher pressure ratios at each compression stage relative to the centrifugal compressor [94]. The existing oil and gas pipeline infrastructure is fully fitted with impellers adversely affected by hydrogen because of sulphide stress cracking [95]. Most compressors along the oil and gas pipelines are fuelled by natural gas, and without natural gas, the compressor fuel supply is shortchanged. Efforts are being made to create hydrogen and electrical-powered compressors, and this would increase the repurposing costs. Manufacturers are also creating dedicated compressor stations to enable the transmission of large-scale hydrogen volumes [96,97].

- B.

- The Valves and Metering Stations

Hydrogen in nature has a very low density, making it prone to leakages which are likely to occur where there is a pipe joining. Compressor stations and valves are among the areas where there is an issue of likely leakage occurrence, where extensive pipeline channels have ball valves connected at approximately 48 km [98]. The ability to close a pipeline section is essential in situations with a leak in the pipeline [99]. The valves along the pipeline length make the maintenance and pipeline section isolations possible. The valves existing on the oil and gas pipelines may be unable to detect hydrogen gas leaks because of its nature (its small molecular size and low density 0.899 g/cm3). A study on the limitations of transporting pure hydrogen indicated that the valves existing in oil and gas pipelines would require considerable repurposing if they were to be repurposed for carrying hydrogen [100].

Metering stations are posted at both ends of every pipeline to record how much gas is transported and how much gas is being received to allow management transparency and help calculate any losses that could have occurred during transmission [98]. The existing metering station on the natural gas pipelines utilises volumetric flow management and is regulated based on the energy content of the natural gas [101]. Metering stations would require recalibration if the pipeline were used for pure hydrogen transmission because of the difference in physical properties of hydrogen.

4.9. Review on the Economics of Hydrogen as an Energy Carrier for Offshore Wind

The economics of a project are determined by its total expenditure, which is the sum of the capital cost and the operating cost. The capital expenditure for hydrogen as an energy carrier for offshore wind is the total amount of funds used in the system construction and in any needed repurposing modifications, such as pipeline bundles and coating. The operating costs are the sum of funds put into the project during the operation, which include the costs of fuel, electricity utilities, maintenance, and any taxes accrued during the project’s life.

For the economics of hydrogen as an energy carrier for offshore wind, the electrolyser has the highest economic effect on the system because electrolysis is an energy-intensive process [102]. The electrolyser’s capital cost is the sum of the cost of the electrolyser stacks and all the equipment that supports the plant’s running (balances of plant costs). Its operating costs include labour, energy, tax, insurance, and maintenance.

PEM electrolysers are expensive relative to the alkaline electrolysers because they are not as commercialised and because the electrodes of the PEM electrolyser are made from expensive metals such as platinum and iridium. Reference [103] found out that the capital cost of a PEM electrolyser is up to 348–1071 euro per kilowatt for the electrolyser systems, while the capital cost of an alkaline electrolyser is up to 242–388 euro per kilowatt for the electrolyser systems. The cost per kg of green hydrogen is affected by the cost of the electrolyser that produces it and by the speed of the wind powering the electrolyser, so as wind speed increases, the cost of hydrogen drops. The cost of the hydrogen produced from solid oxide electrolysers is the most expensive, ranging between 3.43 and 4.46 £/unit of hydrogen [104].

The electrolyser plant usually includes desalination units (if seawater is to be used), cooling units, transformers, and inter-array cables for connections. Table 6 demonstrates the capital cost of the main components of an electrolyser plant.

Table 6.

Electrolyser plant cost per unit [13].

The operating cost of the electrolyser plant includes both its operation and maintenance costs (OPEX), and it is calculated as a percentage of the capital expenditure. For the offshore scenario, OPEX is assessed based on the distance from shore.

The type of foundation to be used in offshore installations depends on the seabed’s water depth and geological properties. Floating foundations are usually the best choice for depths above 60 m, which is considered deep water. The foundation’s cost depends on material type, manufacturing, water depth, and geological location [104].

The pipeline costs are also divided into capital expenditures and operating expenditures. For capital expenditures, the breakdown will include the cost of metering stations, compressors, materials, construction labour, and any other logistics involved in construction. The O&M expenditure includes pipeline maintenance, inspection management, repairs, safety regulation compliance costs, and environmental assessment costs [105].

4.10. Economic Analysis and Harmonisation of Data Sets

In this section, to review the state of the art in a techno-economic literature analysis of the conversion and transmission system for wind-to-hydrogen versus wind-to-electricity pathways, a harmonisation of globally calculated LCOH was harmonised based on their key drivers and assumptions. The values for LCOH that were not in $/kg were all converted to $/kg using the following conversion rates of euro = 1.09 and pounds = 1.29 to enable harmonisation. As seen in Table 7 below, there is a wide variation in LCOH values with a range of values between 2.9 and 11.43$/kg. This wide range is because of the differences in key assumptions in each study. Some studies have assumed a single value for design parameters while others have gone with a range for a more robust analysis of how the LCOH changes with respect to the key drivers. Looking at Table 7, majority of the studies have similar key drivers and key assumptions, but the differences appear in terms of the differences in technology used and the differences in scenario selection. For example, some studies have chosen not to add the transmission system to their analysis and focus mainly on conversion. There is also the matter of the differences in electrolyser placement at the wind farms being studied. Some studies have added centralised and decentralised electrolysis options to their analysis, opening new knowledge pathways and further differentiating their LCOH values. It is worth noting that majority of the LCOH values fall in the range of 3–7$/kg except for some outliers; this range signifies a harmonisation of the research globally.

Table 7.

Global LCOH harmonisation.

4.11. State-of-the-Art Cost Comparative Analysis for the Transmission System

Table 8 gives a tabular representation of the literature that has performed techno-economic analysis on transmission systems. According to the literature, various distance thresholds are considered. A trend has been noticed, when the literature being reviewed has a high distance threshold around 1000 km–3000 km, pipeline transmission is concluded as the more economically preferred option, but when lower distance thresholds are in the mix, the cable is selected as more economically viable at a particular threshold of lower distances. This has led to the conclusion that the selection of the right transmission system is not dependent on longer distances alone. The selection of a transmission system is dependent on the distance from shore, electrolyser capacity, electrolyser CAPEX, and hydrogen production rate. The distance from shore alone is not enough to determine the transmission to be selected. The system’s peculiarities must also be considered.

Table 8.

Transmission Distance Threshold Harmonisation.

Some limitations of the studies reviewed were conservative pipeline costing estimates and a gap in studies that have considered the costing implications of using repurposed gas pipelines.

5. A Reflective Analysis of Wind-to-Electricity Versus Wind-to-Hydrogen Energy Systems

When looking into the production of hydrogen within the wind-to-hydrogen energy system, the electrolyser production capacity needs to be scaled up to meet the future increase in wind energy generation. For this scaling up to be achieved without adversely affecting the CAPEX and OPEX, a balance between the electrolyser current density and its cell potential should be found by studying the electrolyser electrochemical properties [112].

Compared to electricity generation, hydrogen generation is more expensive; however, transmission-wise, it can reduce transmission losses, especially as the technology for hydrogen transmission becomes more widely implemented. While both energy carriers have their positives, hydrogen as an energy carrier is a much more versatile gas with applications spanning from being a feedstock for many industries to being a clean fuel for automobile and aviation transport applications, as well as for heating and cooking. While electricity can be directly supplied to the grid, hydrogen provides flexibility and versatility in terms of its end use. The wind-to-electricity system has the advantage of being at a higher technological readiness level, while most of the technologies used for the wind-to-hydrogen systems are in their research and development stage. The opportunities connected to hydrogen are vast and environmentally positive, but electricity is essential too. Therefore, the consensus should be to select the best-suited energy carrier for wind based on the needs.

While producing the hydrogen from seawater electrolysis would eliminate the cost of freshwater transport to offshore platforms and would save our clean water resources, the issue with seawater desalination would be its corrosion effect on the electrolyser.

Looking at hydrogen transmission compared to electricity transmission, hydrogen tackles the issue of transmission losses that occur when electricity is used as the energy carrier for wind. Transporting hydrogen in pipelines would reduce the energy lost during electricity transmission, thus making the wind-to- hydrogen system cost-efficient.

Given their lower transmission losses, many studies investigated the economic viability of wind-to-hydrogen systems. They found that hydrogen as an energy carrier for offshore wind is economically viable mainly when wind farms are far from shore, because the hydrogen system is more expensive than the established electrical system. Based on these assessments and given that hydrogen offers significant benefits, if integrated to offshore wind energy systems, it is essential to create policies that promote its use and make it a more economically viable venture. Table 9 summarises the comparison between the offshore wind-to-hydrogen and the wind-to-electricity systems.

Table 9.

Comparison between offshore wind-to-hydrogen and wind-to-electricity systems.

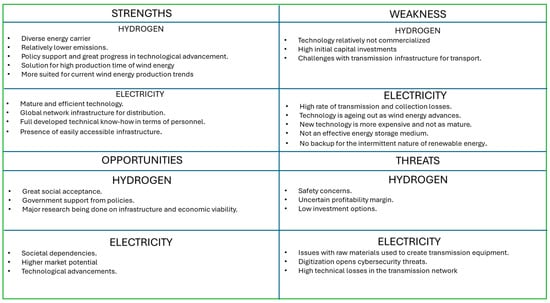

From the performed SWOT comparative analysis on wind-to-hydrogen and wind-to-electricity systems, Figure 14 summarises the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of both systems. Using the hydrogen-based system could potentially address some of the shortcomings of electricity as an energy carrier, especially with the wind farm locations being moved further offshore nowadays. Figure 14 also highlights the strength of hydrogen as an energy storage medium for addressing the intermittent nature of offshore wind energy. The figure also highlights the threats that might arise with the growth of hydrogen conversions and transmission systems, such as leaks, safety concerns, and uncertainty in profit margins because most of the technologies associated with the hydrogen system are still under research for improvements or are not as technologically mature, so they have higher costs.

Figure 14.

SWOT analysis for the comparison of hydrogen and electricity systems [134,135,136].

Currently, the electrical conversion and transmission system has an upper hand over the hydrogen system because of its higher technological maturity. But with the move of the wind farms to far offshore locations and the need to upgrade the electrical systems, hydrogen systems have become more resilient systems with versatility.

To support offshore wind energy growth, future wind energy conversion and transmission systems should be robust with fewer weaknesses and have considerably higher profit margin, and hydrogen systems can allow this.

6. Conclusions

The electrical-based conversion and transmission system is already mature compared to the hydrogen-based system. However, given the future trend of wind energy moving far offshore, it has been found that hydrogen systems are better suited than electrical-based systems. In terms of the technical aspect, hydrogen systems still have some challenges due to a paucity in research. To reduce hydrogen system economic strain, this research investigated utilising resources such as deionised seawater for generating hydrogen instead of transporting clean water from shore and also investigates the repurposing of the existing oil and gas pipeline infrastructure for the transmission of hydrogen.

Hydrogen, in addition to being an energy storage medium for supporting the renewable intermittency, is also a clean energy carrier for renewable energy and can be used as a clean fuel to decarbonise many end-uses, including the transport, heating, and the hard-to-abate industries, thus reducing the need for natural gas.

The main challenge facing the hydrogen-based system is the high capital investments required at the initial stages of the project coupled with other key drivers such as operating costs, electricity prices, distance from shore, and wind energy capacity factor.

In conclusion, the hydrogen-based system will have many benefits over the electricity-based system. But more research is needed to advance the offshore wind-to-hydrogen-based conversion and transmission system technologies as well as the desalination technologies to facilitate the use of seawater for saving clean water resources and eliminating the cost associated with water transmission offshore. To further reduce system costs, research should also assess the feasibility of repurposing the existing NG pipelines for hydrogen transmission. The policies that guide hydrogen transmission should also be revised to give rise to a much more favourable economic situation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: F.A. and D.A. Investigation: F.A. Writing—original draft preparation: F.A. Review and editing: D.A. Supervision: D.A. Funding acquisition: D.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author acknowledges the Robert Gordon University for the award of the Interdisciplinary Scholarship Fund. This study is part of the Comprehensive One Stop Hydrogen Storage Testing Facility (HyOne) Project (Pr. No. EETF/HIS/APP/007—https://www.hy-one.co.uk/) jointly funded by the Robert Gordon University and the Scottish Government under the Emerging Energy Transition Fund, Hydrogen Innovation Scheme, Stream 2.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| HVDC | High Voltage Direct Current |

| HVAC | High Voltage Alternating Current |

| LFAC | Low Frequency Alternating Current |

| H2 | Hydrogen |

| NG | Natural Gas |

| SWOT | Strength Weaknesses Opportunities Threats |

| HAWT | Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| VAWT | Vertical Axis Wind Turbine |

| SCIG | Squirrel cage induction generators |

| WRIG | The Wound Rotor Induction Generator |

| DFIG | The Double-fed Induction Generators |

| WRSG | Wound Rotor Synchronous Generator |

| PMSG | Permanent Magnetic Synchronous Generator |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| OPEX | Operating Expenditure |

| PEM | Polymer Electrolyte Membrane |

| DC | Direct Current |

| AC | Alternating Current |

| AEL | Alkaline Electrolyser |

| SOEC | Solid Oxide Electrolyser Cell |

| WACC | Weighted Average Cost of Capital |

References