1. Introduction

Flexible and wearable electronics have gained growing interest for health monitoring, which creates a strong demand for soft, stretchable materials that maintain reliable electrical performance under mechanical deformation [

1,

2]. Among various promising materials, bottlebrush elastomers (BBEs) have recently received great attention due to their unique architectures, which include the densely grafted side chains along a linear backbone that can minimize polymer entanglements and offer exceptional softness [

3]. Unlike other soft materials like hydrogels, BBEs are solvent-free, offering improved long-term stability for applications across diverse environments [

4].

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-based BBEs are particularly promising for soft electronics, which combine biocompatibility, thermal and chemical stability, and ultra-low elastic moduli [

5]. However, a key limitation of PDMS-based BBEs is their intrinsic electrical insulation [

6]. To address this, conductive nanofillers, such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [

7], graphene [

8], metallic nanowires [

9], or conductive polymers [

10] have been incorporated into the BBEs matrices to create conductive hybrid composites [

11]. Among these, CNTs are especially popular due to their superior electrical conductivity and mechanical resilience [

12]. Early studies have reported the role of CNTs as multifunctional reinforcements that are capable of forming conductive networks even at low filler concentrations [

13].

Recent research has focused on integrating CNTs into soft polymer matrices to develop conductive materials for strain sensing, motion tracking, and bioelectronic interfaces. Xu et al. reported ultrasoft CNT–bottlebrush composites that achieved satisfactory conductivities of 2.68–13.78 S/m while maintaining an ultra-low Young’s modulus of 2.98–10.65 kPa [

11]. This work demonstrates the feasibility of balancing conductivity and elasticity to create a soft conductive elastomer. Similarly, Peng et al. emphasized the importance of filler alignment and percolation pathways for achieving stable electromechanical performance under deformation [

14]. These studies highlight that CNTs not only affect conductivity but also influence viscoelastic behavior and fatigue response. Therefore, understanding how CNTs content and network morphology interact with matrix stiffness is essential for designing high-performance elastomers for wearable strain sensors and soft robotics where both sensitivity and durability are critical.

While the feasibility of CNTs/PDMS-BBEs composites has been demonstrated [

11], most prior studies have focused on synthesis protocols, with limited systematic evaluation of how compositional parameters affect functional properties of the resulting materials. In particular, the effects of variables such as the PDMS-to-crosslinker molar ratio and CNTs’ loading on conductivity, mechanical sensitivity, and fatigue resistance remain underexplored [

15]. These properties are critical for engineering and tailoring soft composites for dynamic applications, where materials are often subjected to continuous deformation such as bending [

16]. Furthermore, material selection frameworks such as the multi-criteria decision-making approach used by Bulut et al. ranked thermoplastic polymers for hybrid-vehicle battery packs [

17]. The framework evaluates both performance and sustainability criteria to balance the engineering design. Similar approaches have been used to rank biobased polymers based on end-of-life pathways, for example, reuse and mechanical recycling, while also meeting functional performance criteria [

18]. Although our present work focuses on mechanical and electrical functionalization, we adopt a comparable mindset by systematically varying composition and evaluating relationships between structure and functionality. Additionally, recent advances in BBEs synthesis, which include solvent-free formulations and organocatalytic polymerization, as well as the development of 3D printable bottlebrush elastomers, have further expanded the design space for functional materials [

19]. However, significant challenges remain. Among them, the integration of electrical functionality into BBEs without compromising mechanical integrity is still a major materials design challenge [

7,

11].

This study addresses these challenges by embedding CNTs into PDMS-based BBEs to fabricate conductive composites. We systematically investigate how variations in material compositions affect the electromechanical and fatigue behavior of the resulting composites. Using a scalable, solvent-free synthesis approach, we collect data to demonstrate how a balance can be achieved between conductivity, sensitivity, and durability. Unlike conventional PDMS hydrosilylation that relies on Pt catalysts, we use a metal-free, AIBN-initiated radical hydrosilylation to eliminate catalyst residues while achieving elastomer curing [

20]. Our findings show a composition-dependent trade-off in performance and provide a framework for tailoring the composites for the next generation of soft electronic devices and health monitoring.

3. Results

3.1. Material Synthesis and Morphology

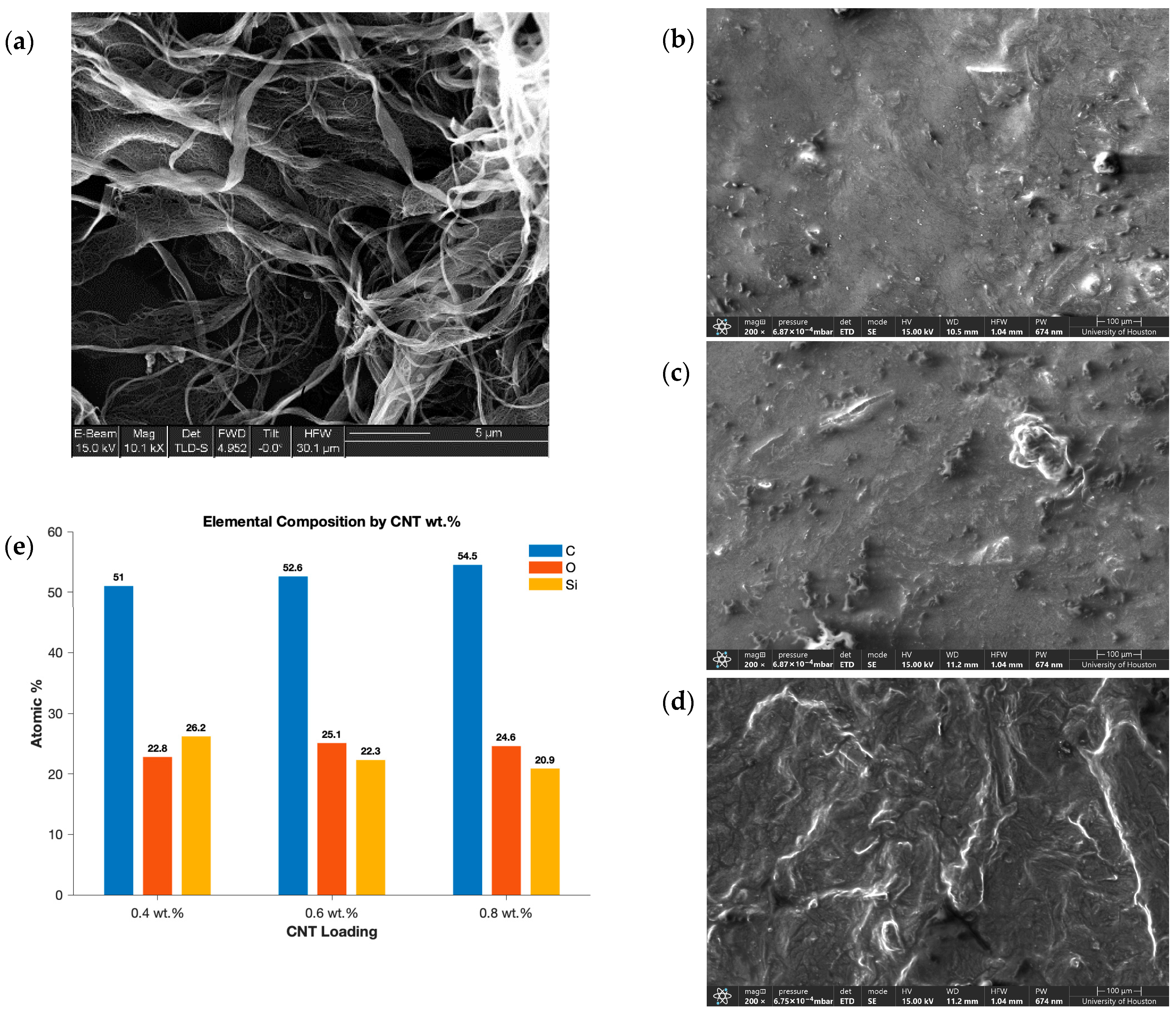

Figure 1a shows an SEM image with magnification of 10.1 kV to demonstrate the SWCNT networks. The image shows the individual tubular morphology of the CNTs, which contributes to their conductivity properties.

Figure 1b–d show SEM images of the cured BBE/CNT composites with a PDMS/crosslinker molar ratio of 600:1 and CNT loadings of 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 wt.%, respectively. At the lowest loading of 0.4 wt.%,

Figure 1b, CNTs appear sparsely distributed, with several isolated bundles visible on the surface. Increasing the CNT concentration to 0.6 wt.% results in a denser and more continuous network as shown in

Figure 1c, indicating improved interconnection between the carbon nanotubes. At 0.8 wt.% in

Figure 1d, the CNTs create an almost fully percolated network, with locally entangled regions that suggests the onset of partial agglomeration. Overall, the change in distribution from 0.4 to 0.8 wt.% demonstrates an increase in CNT connectivity while maintaining a generally uniform dispersion, confirming that the mixing of the CNTs was effective within the BBE matrix.

To further evaluate elemental composition in composites, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was conducted on BBEs samples with different CNTs loadings of 0.4 wt.%, 0.6 wt.%, and 0.8 wt.%. This analysis aims to quantitatively confirm the successful incorporation of CNTs into the BBE matrix and to analyze how increasing the CNTs content in the samples affects that relative atomic distribution of the elements carbon (C), oxygen (O), and silicon (Si). These three elements were chosen for quantification because carbon is a major component of both PDMS and the SWCNTs. This provides insight into the changes in composition due to CNT loading. Oxygen and silicon are native to the PDMS backbone, which help track compositional changes in polymer content with increasing CNT loading.

For characterization, samples of BBE/CNT composites were placed on silicon wafers. As seen in

Figure 1e, EDS quantification revealed an increase in the carbon atomic percentage as the CNT wt.% increased. This confirms successful incorporation of CNTs into the bottlebrush elastomer matrix and is consistent with increased CNT content. The increase in carbon content suggests the CNTs are both physically embedded in the sample and well-distributed across material surface, which aligns with the morphological observations in

Figure 1b–d, where the CNT network becomes denser and more continuous at higher loadings.

Additionally, oxygen levels remained stable for the samples ranging from 22.8% to 25.1%, indicating stable PDMS content. The fluctuations in oxygen might be introduced by surface oxidation due to exposure of the samples to air during handling. The silicon content, on the other hand, showed a decreasing trend with increased CNT loading. This is expected since an increased CNTs content displaces some of the PDMS, which is the main source of silicon. The decrease in silicon with the increase in carbon content emphasizes the inverse relationship between PDMS content and CNT loading and the change in composition. It is also worth mentioning that although the use of silicon wafers may have slightly overestimated the absolute silicon content due to the background signal from the substrate, all samples were characterized under identical preparation and measurement conditions. Therefore, the observed trend of decreasing silicon content with increasing CNT loading remains valid for comparative purposes.

Additionally, elemental carbon (C-K) count maps for the 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 wt.% samples are provided in

Supplementary Figure S6. These maps further confirm the uniform spatial distribution of carbon throughout the elastomer matrix across all loadings, with increasing pixel intensity corresponding to higher CNT concentrations. The consistent dispersion observed across all samples supports the quantitative EDS data and demonstrates effective incorporation of CNTs during synthesis.

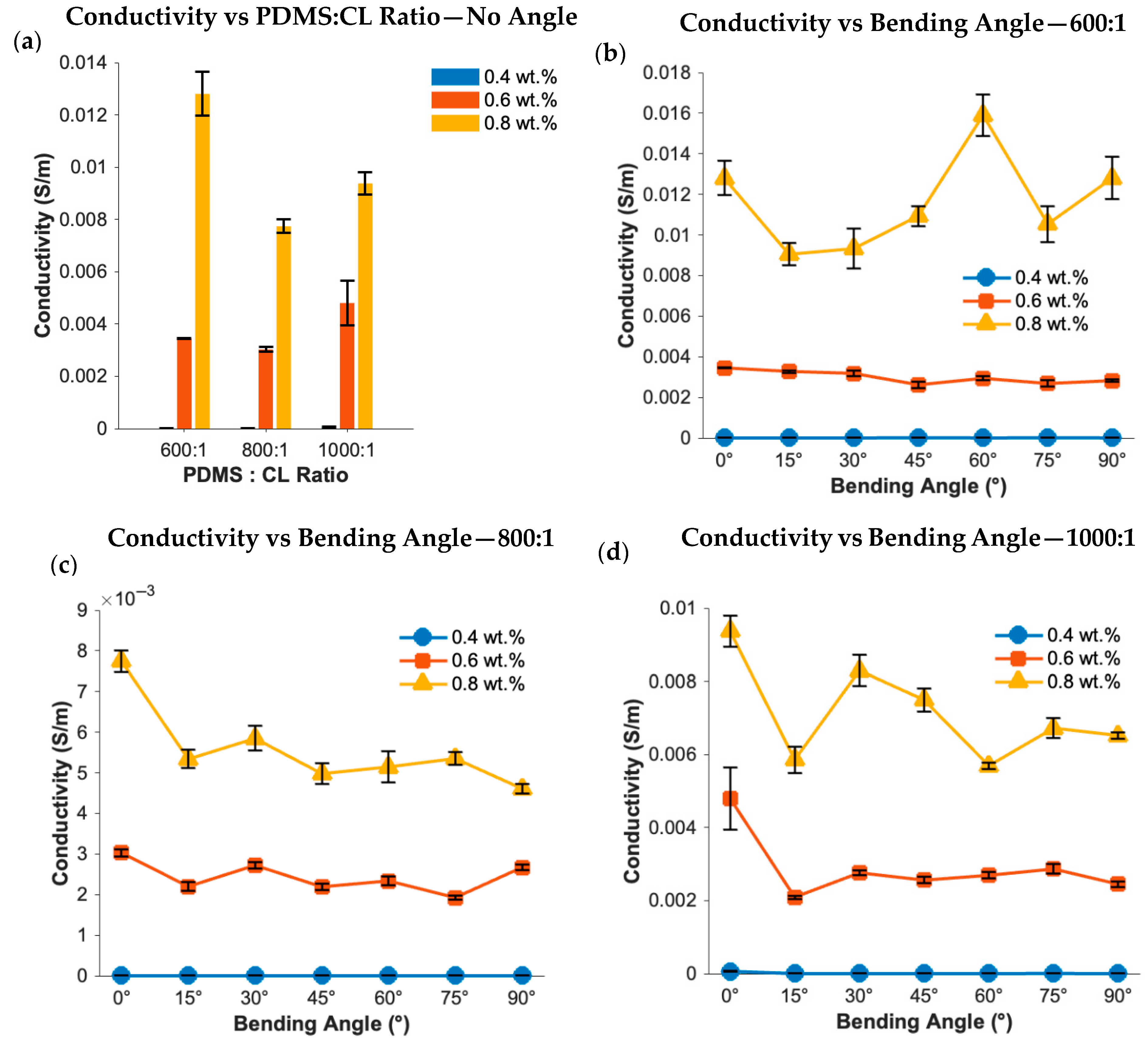

3.2. Electrical Conductivity

Figure 2a shows the conductivity result of samples tested on a flat surface. As seen, for all formulations with different molar ratios between PDMS and crosslinker, conductivity increased as CNT loading increased from 0.4 to 0.8 wt.%. This trend is expected as a higher CNT content can facilitate more interconnected conductive pathways throughout the elastomer matrix.

For different molar ratios between PDMS and crosslinker with a 0.4 wt.% CNT loading, all formulations showed low conductivity (<0.002 S/m) for the four-point probe test. This suggests that at this concentration, the CNTs remain below the percolation threshold, resulting in insufficient conductive pathways similar to a prior report [

31]. The limited interconnectivity at 0.4 wt.% suggests that CNTs are too sparsely distributed to form continuous networks.

For the 0.6 wt.% CNT loading, conductivity significantly improved across all samples with different molar ratios of the PDMS and crosslinker. For example, the samples with a molar ratio of 1000:1 showed the highest conductivity ~0.005 S/m, while samples with ratios of 600:1 and 800:1 reached about 0.003~0.004 S/m, respectively. These results suggest that the 1000:1 formulation likely supports better network formation at low to moderate CNT concentrations, possibly due to a more connected network that preserves conductive paths.

At 0.8 wt.% CNT loading, all the samples exhibited a significant increase in conductivity: 600:1 (0.013 S/m), 800:1 (0.007 S/m), and 1000:1 (0.009 S/m). Interestingly, the 600:1 formulation resulted in the highest conductivity at 0.8 wt.% CNTs. This may be because the denser crosslinking network offers enhance structural stability and promotes a more uniform CNT dispersion. This suggests that above a critical CNT loading, the influence of crosslinking density may have diminished, and all systems can support robust percolated networks.

Overall, this data highlights the compositional interplay between CNT loading and crosslinking density. At lower CNT content, network stability may play a great role. However, once a threshold loading is surpassed (~0.8 wt.%), all samples achieve high conductivity, indicating effective percolation regardless of crosslinking ratio.

3.3. Angle-Dependent Conductivity

Figure 2b–d present the conductivity response of the CNT/BBE composites under bending for PDMS/CL ratios of 600:1, 800:1, and 1000:1. Overall, the conductivity trends reveal composition-dependent electromechanical stability, where both CNT loading and crosslinking density strongly affect how well conductive networks withstand deformation.

For the 600:1 formulation in

Figure 2b, the 0.8 wt.% CNT composite showed the highest conductivity (~0.009–0.016 S/m) but also exhibited noticeable fluctuation across bending angles. This variation suggests that at high CNT loadings, while a dense percolation network ensures high conductivity, local agglomeration and microcrack formation during bending may intermittently disrupt contact between CNT clusters [

32]. These transient resistive changes produce the observed conductivity oscillations. In contrast, the 0.6 wt.% sample showed lower but more stable conductivity values (~0.003 S/m) across all angles, suggesting that a moderately connected CNT network offers a better balance between electrical continuity and elastic compliance. At this intermediate loading, the CNTs are sufficiently interconnected to form a continuous conductive network, while still being sufficiently dispersed to allow the polymer matrix to deform without creating a high-stress concentration [

33]. The conductivity of the 0.4 wt.% sample remained relatively low (<2 × 10

−5 S/m) but still exhibited some variation, as shown more clearly in

Supplementary Figure S8. This fluctuation likely arises from partial reformation and breakage of isolated conductive paths as the sample bends, typical of materials near the percolation threshold [

34,

35].

At the 800:1 ratio in

Figure 2c, the same overall trend of conductivity was observed with the 0.8 wt.% sample, which exhibits the highest conductivity. The 0.8 wt.% sample showed a slight decrease in conductivity as bending increased while the 0.6 wt.% maintained a consistent conductivity around 0.0025 S/m with minimal drift. These results indicate that the softer matrix (from the reduced crosslinking density) accommodated deformation more evenly, minimizing strain that could disrupt conductive networks. However, the 0.4 wt.% samples again showed a low conductivity (<1 × 10

−5 S/m) with small amplitude fluctuations in

Supplementary Figure S8b likely caused by the isolated CNT clusters making and breaking contact under mechanical stress.

For the 1000:1 composite in

Figure 2d, conductivity ranged from ~0.006 to 0.009 S/m for the 0.8 wt.% samples. The 0.8 wt.% sample again showed slightly greater variability compared to the 0.6 wt.% sample, which remained relatively flat apart from a drop at 15°. This sudden decrease is likely caused by localized strain of the conductive junctions. At low bending angles, tensile stress is concentrated near the surface where slight separation of CNT junctions can result in a loss of conductivity [

33]. However, this still suggests that a moderate CNT content produces the most stable and resilient conductive network, as it minimized both filler aggregation and strain-induced detachments. The 0.4 wt.% samples also demonstrated low conductivities, with occasional spikes seen at intermediate angles in

Supplementary Figure S8c, reflecting unstable behavior at low CNT loadings.

Overall, these results reveal a key trade-off. High CNT loading enhances absolute conductivity but introduces greater signal variability, while moderate CNT loading (0.6 wt.%) yields a more stable conductivity under repeatable deformation, which is consistent with previous findings [

28]. Although the 0.4 wt.% samples were below the percolation threshold, they displayed transient conductive variations which highlights the sensitivity of these samples. This composition-dependent behavior highlights the importance of optimizing CNT content to balance conductivity and mechanical reliability in soft conductive composites.

3.4. Sensitivity Performance

Figure 3a–c present the sensitivity of the CNT/BBE composites to compressive loading, represented by the number of paper layers placed on top of these samples for PDMS/CL ratios of 600:1, 800:1, and 1000:1. Using the four-point probe approach, this test evaluated how conductivity changes with externally applied subtle pressure and provides insight into the materials potential for pressure-sensing applications.

For the 600:1 formulation in

Figure 3a, the 0.8 wt.% CNT composite exhibited the highest conductivity (>0.02 S/m) with noticeable fluctuations as the number of paper layers increased. This behavior indicates that dense conductive networks at higher filler loadings experience local compression of CNT junctions under pressure with temporary disruption or reorganization due to uneven stress disruption within the relatively stiff matrix. In contrast the 0.6 wt.% composite displayed significantly lower but more consistent conductivity (~0.005 S/m) across all layers, reflecting a more stable percolation network. The 0.4 wt.% sample showed conductivities below 0.4 × 10

−4 S/m but demonstrated distinct spikes at higher loads as seen in

Supplementary Figure S9a, likely caused by brief conductive links forming between CNTs when the material is compressed.

At the 800:1 ratio in

Figure 3b, the same conductivity hierarch was observed. The 0.8 wt.% samples reached peak conductivities around 0.009 S/m, increasing progressively with additional layers, while the 0.6 wt.% samples exhibited relatively smoother, monotonic increased with a smaller magnitude of change. The linearity of the 0.6 wt.% composite suggest that the softer matrix distributes compressive strain more uniformly, maintaining network connectivity. The 0.4 wt.% sample again displayed low conductivity but a clear upward trend with additional layers as in

Supplementary Figure S9b, which is likely due to realignment of the CNTs or compression that enhances conductive contacts [

32].

For the 1000:1 composite in

Figure 3c, the same overall conductivity trends were observed. The 0.8 wt.% samples maintained high conductivity with oscillations, reflecting a highly compressible yet percolated network. The 0.6 wt.% samples showed very small fluctuations with a stable incremental increase in conductivity with layer count, again confirming its superior stability and repeatability. The 0.4 wt.% sample remained below the percolation threshold, exhibiting irregular peaks at mid-range pressures in

Supplementary Figure S9c, possibly due to CNT reorientation.

Overall, these results reinforce the composition-dependent trade-off between absolute conductivity and stability. Higher CNT concentrations enhance conductivity but are prone to instability due to microstructural rearrangements. Alternatively, moderate CNT loadings yield lower conductivity but greater stability under changing pressure.

3.5. Fatigue Performance

Figure 4a–c show the conductivity changes in the BBE/CNT composites under repeated bending cycles up to 1000 cycles for PDMS/CL ratios of 600:1, 800:1, and 1000:1. This test evaluated how well the conductive network withstands cyclic deformation and fatigue.

For the 600:1 formulation in

Figure 4a, the 0.8 wt.% CNT composite exhibited the highest conductivity but also the largest fluctuations across the cycles. These oscillations imply repeated deformation and breakage of conductive junction during bending, which is typical of dense CNT networks embedded in relatively stiff matrices [

33]. The 0.6 wt.% sample showed a lower but more stable conductivity (~0.004 S/m) throughout the 1000 cycles, indicating a well-balanced network that can deform elastically while maintaining continuous percolation paths. The 0.4 wt.% sample had low conductivity (< 3 × 10

−5 S/m) in

Supplementary Figure S10a and displayed multiple spikes at early cycles, which is likely due to temporary reconnection of the isolated CNT clusters.

For the 800:1 composite in

Figure 4b, the 0.8 wt.% showed a slightly improved stability compared to the 600:1 formulation, where larger oscillations were observed. The reduced fluctuation indicates that the lower crosslinking density provided greater compliance, allowing the network to deform more uniformly without extensive microcracking or localized separation of CNT junctions. However, the 0.6 wt.% sample at this ratio displaced slightly greater variability with spikes in conductivity at 600 and 1000 cycles. This suggests that as the matrix softens, moderate CNT networks may begin to partially reorganize under cyclic strain, leading to local resistive changes. This consequently affects the performance as the bending locations were intentionally changed during the tests to simulate future real-world applications. The 0.4 wt.% sample again showed very low conductivity as presented in

Supplementary Figure S10b with minor intermittent spikes, likely due to temporary reconnection of isolated CNT clusters.

For the 1000:1 formulation in

Figure 4c, the 0.8 wt.% sample exhibited the highest conductivity but with spikes and drift, reflecting less stable network behavior. This instability likely arises from the highly compliant matrix and extensive CNT interconnectivity, which promotes slippage and recontact between conductive networks during bending. In contrast, the 0.6 wt.% samples maintained relatively consistent conductivity throughout cycling, indicating that moderate CNT loading can better accommodate cyclic strain without causing large-scale disruption of the network. The 0.4 wt.% samples remained below the percolation threshold, showing minimal conductivity and many fluctuations in

Supplementary Figure S10c.

Overall, these findings show that the 600:1 formulation offered the highest stability for moderate CNT loadings, while the 800:1 composition improved the stability of the 0.8 wt.% networks by enabling more elastic deformation. However, in the soft matrix (1000:1), both high and moderate CNT loadings experienced decreases in conductivity over cycling. This confirms that both crosslink density and filler concentration must be optimized to balance conductivity, flexibility, and long-term stability in soft electronic materials.

Additionally, post-fatigue SEM analysis of test samples was performed, such as the 600:1 composite in

Supplementary Figure S7, which revealed that the CNT networks remained well dispersed and structurally intact after repeated bending. Although minor surface roughening was observed, no significant cracking was detected.

3.6. Normalized Conductivity Comparison

The normalized conductivity plots (

Figures S11–S16) highlight the strain-dependent response of the CNT/BBE composites under bending, pressure, and cyclic loading, comparing measurements obtained with both the two-point probe and four-point methods. Normalization was performed to eliminate the influence of initial conductivity differences among compositions, allowing visual comparison of relative changes in the trend of electrical performance under deformation rather than quantitative evaluation across different samples.

In the two-point probe data, conductivity decreased steadily with the bending angle, particularly for the 0.4 wt.% and 0.6 wt.% sample, indicating disruption of less connected CNT networks. The 0.8 wt.% composites retained higher normalized conductivity due to denser CNTs. Under pressure (

Supplementary Figure S12), conductivity increased with applied loads, with the 0.4 wt.% sample showing the steepest rise. Fatigue testing (

Supplementary Figure S13) showed a gradual decrease in conductivity for all samples.

The four-point probe method (

Figures S14–S16) revealed sharper variation, particularly at low CNT loadings, as contact resistance effects were eliminated. The 0.4 wt.% samples exhibited large fluctuation due to reformation of the CNTs and sparse conductive networks. Compared to the two-point setup, the four-point method captures intrinsic conductivity changes more accurately, suggesting that apparent stability in two-point data may partly arise from probe contact resistance. Overall, the four-point configuration may better reflect true material performance.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the significant potential of BBEs/CNTs composites as tunable materials for next-generation soft electronic devices and health monitoring. By systematically varying the PDMS/crosslinker ratio and CNTs loading, we demonstrated how electrical conductivity, mechanical flexibility, pressure sensitivity, and fatigue resistance can be tailored to suit specific application requirements. These results offer a foundation for material optimization across diverse use cases. from wearable sensors to soft robotics.

A key outcome of this work is the trade-off between conductivity and electrical stability. Composites with higher CNT content (0.8 wt.%) exhibited the highest conductivities across all formulations (up to 0.016 S/m for the four-point probe method) at 600:1, but these samples demonstrated greater signal fluctuations during bending and cyclic testing. This variability likely originated from local rearrangement of CNT clusters and intermittent junction breakage within dense percolation networks. Conversely, moderate CNT loading (0.6 wt.%) consistently produced lower but more stable conductivity, as the networks were sufficiently connected to maintain conductivity while allowing elastic deformation of the polymer backbone. These characteristics suggest that the 0.8 wt.% composites are best suited for applications requiring higher conductivity and sensitivity to deformation, such as conductive electrode layers, while the 0.6 wt.% composites offer enhanced reliability and reproducibility for wearable pressure sensors and soft robotic systems where stability is critical. The 0.4 wt.% composites remained below the percolation threshold and showed weak but detectable responses, indicating potential utility in low-pressure tactile sensing were subtle changes in contact resistance are desirable.

During fatigue testing, the 600:1 formulation exhibited the most stable performance for moderate CNT loading, whereas the 800:1 formulation improved the deformation tolerance of the 0.8 wt.% networks. However, in the highly flexible 1000:1 formulation, high CNT composition increased fluctuation over different cycles, highlighting that excessive matrix softness can compromise network stability. Importantly, bending location was deliberately changed between fatigue cycles to mimic real-world conditions experienced by soft robotic devices. While this approach provides a realistic evaluation of use conditions, it may also have induced local strain variations. Additionally, the current study was limited to manual bending up to 1000 cycles. Automated flexing with controlled amplitude, frequency, and in situ monitoring will be essential for future work to characterize long-term electrical drift, recovery behavior, and potential temperature effects during repeated deformation. Conducting extended cycling tests would provide a more rigorous assessment of network stability and help establish the reliability of BBE/CNT composites for soft electronic applications. Furthermore, this study explored mechanical fatigue and pressure responsiveness, but other environmental factors such as biocompatibility need to be assessed to determine suitability for wearable devices [

2]. Finally, this study focused on cyclic bending to assess fatigue performance; future work will need to include uniaxial tensile testing to quantitatively evaluate tensile strength, modulus, and elongation at the break. This will enable a direct comparison between mechanical performance, electrical, and morphological properties.

Future research may also focus on enhancing the directional (anisotropic) conductivity of the composites by aligning CNTs during curing, which may further improve performance in stretchable interconnects or directional sensors. Incorporating hybrid nanofillers, such as silver nanowires, may offer a new strategy to further improve conductivity while tailoring mechanical behavior.

Together, the combination of conductivity, sensitivity, and durability results in this work establishes a design framework for BBEs/CNTs composites. By tuning crosslinking density and CNTs content, materials can be custom designed for their intended function, prioritizing sensitivity, flexibility, or durability as needed. This adaptability underscores the versatility of BBEs/CNTs composites for integration into soft, stretchable, and wearable electronics, paving the way for future innovations in human–machine interfaces, soft prosthetics, and flexible health monitoring devices.

While this study focuses on how variations in material compositions affect the electromechanical behavior of the resulting BBE/CNT composites,

Supplementary Table S2 summarizes their performance relative to other reported PDMS-based bottlebrush elastomers [

11,

29,

30]. It is important to note that conductivity in this work was measured using both two-point and four-point probe methods, whereas prior studies employed the two-point approach. Additionally, one set of results is given in

Table S2, which exhibits a good balance between conductivity and signal stability as discussed in the Results above. As seen, the two-point results were consistent with previously reported values, confirming alignment with the literature and supporting the use of the composites for benchmarking and application testing, such as ECG signal acquisition and the development of wearable sensors in the future.