Abstract

Numerous studies have utilized Petri nets for modeling, fault diagnosis, and deadlock control in manufacturing processes and systems. However, most are confined to specific subclasses of Petri nets, thus limiting their applicability. This paper extends the research scope by focusing on generalized Petri nets, analyzing system models from a novel perspective, and demonstrating the complete workflow from modeling to constraint establishment, controller integration, and deadlock avoidance. The methodology begins with an introduction to thread analysis, which involves identifying critical transitions within individual threads to locate resource cycles and minimal siphons corresponding to dead transitions, along with the presentation of a dedicated algorithm for this purpose. Next, optimal constraints are derived based on the thread analysis approach, with generalized patterns summarized for partially parameterized scenarios. Controllers are then incorporated into the system model according to the aforementioned constraints. Finally, derivative issues arising from controller integration are discussed, and pathways based on thread–circuit analysis are synthesized. The entire process described above is substantiated through illustrative case studies.

1. Introduction

In complex resource allocation systems such as automated manufacturing systems, multithreaded parallel programs can enhance system performance, reduce power consumption, and save time. However, they also pose many potential issues, such as race conditions and deadlocks, which hinder system performance, reduce efficiency, and compromise system security. Fault diagnosis, fault repair, and how to handle deadlocks in a system in parallel programs are topics of significant concern [1,2].

To avoid deadlocks, we apply discrete control theory to system modeling and control. Due to their strong expressive power, Petri nets are widely used in modeling automated manufacturing systems [3,4,5], multithreaded software systems [6], and similar applications [7,8,9,10,11]. However, the analysis and control problems of general Petri nets are highly challenging—sometimes even undecidable in certain scenarios. As a result, most prior research has focused on controllable subclasses of Petri nets [12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

Research on deadlocks based on Petri nets primarily proceeds from structural analysis and reachable sets. However, due to the state explosion problem, the reachable set method can only be applied to small-scale net systems. Such as the work in [19], it develops a new deadlock prevention strategy which can decrease the number of constraints and variables in the ILPs, but needs to generate the full RG of a PN model. So, it is hard to apply to large net systems because of high computational complexity. As a result, many control strategies are based on structural analysis, starting with siphons. The foundation of such strategies lies in identifying an appropriate siphon controllability condition. Researchers have developed numerous deadlock control strategies based on siphon control [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. To prevent deadlocks, it is necessary to ensure that every siphon in the net is controllable. Therefore, adding controllers to siphons is a common approach. However, if some siphons are inherently controllable, the added controllers become redundant, leading to unnecessary costs. To avoid redundancy, researchers have attempted to find an optimal control method that achieves the goal of controlling the entire net with as few controllers as possible. In ordinary Petri nets, a siphon is considered controllable if it remains marked under all reachable markings [20,21,28]. Based on this definition, the controllability of all siphons in an ordinary net serves as a necessary and sufficient condition for deadlock-freeness. For certain specialized nets, such as S3PR and L-S3PR, ensuring deadlock-freeness is equivalent to guaranteeing liveness. Most existing control strategies achieve deadlock prevention by adding controllers to make siphons controllable. If the net remains an ordinary Petri net after controller addition, the liveness can still be ensured based on the siphon controllability condition for ordinary nets. However, in practice, adding controllers may introduce weighted arcs, thereby converting the net into a generalized weighted Petri net. In such cases, the controllability conditions and strategies for ordinary nets no longer apply.

A perfect liveness-enforcing supervisor is the one that has a simple control structure, is optimal, and can be compared without prohibitive computational cost. Unfortunately, such a perfect supervisor does not exist in a general large-scale case. In the case of large-scale systems, most existing approaches suffer one or more problems such as structural complexity, behavioral permissiveness, and computational complexity [30]. Uzam [31] proposed a deadlock prevention policy based on a reachability graph analysis of a Petri net model of a given FMS and synthesized a set of new net elements to be added to the Petri net model, using the theory of regions. Its problem is the size of reachability graph when applied to a very large Petri net owing to the “state explosion problem”. In their following work [32], an improved method was proposed by using a Petri net reduction approach. This method is easy to use if the reachable space of a system is small but does not guarantee the optimality of a supervisor. Ref. [33] uses the theory of regions to derive an effective approach since it can definitely find an optimal supervisor if such a supervisor exists. However, it suffers from computational and structural complexity problems. A selective siphon control policy is proposed in [26], which can obtain a small-sized supervisor with highly permissive behavior. However, there is no formal proof to show this policy is maximally permissive in theory. In other words, it reduces the complexity of supervisory structures but cannot minimize them.

The performance of a deadlock prevention policy is always evaluated by considering the following criteria: behavior permissiveness, structural complexity, and computational complexity. To the best of our knowledge, no existing studies, including those mentioned above, have been able to fulfill all three criteria concurrently. This paper proposes a deadlock analysis method for generalized Petri nets from a thread perspective, eliminating the need to enumerate all siphons, which is clearer and more concise. By analyzing threads, we identify the resource cycles associated with dead transitions, locate their corresponding minimal siphons, and establish optimal constraints. A controller is then added to ensure the resulting system remains deadlock-free. Experimental validation revealed that it is both maximally permissive and structurally minimal. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- A thread-based analytical approach for system deadlock is proposed, which is particularly effective in multithreaded application scenarios. And deadlock avoidance pathway based on thread–circuit analysis is summarized.

- (2)

- The correspondence among dead transitions, resource cycles, minimal siphons, and liveness in Petri nets and an algorithm to identify associated resource cycles and minimal siphons based on dead transitions are proposed. By imposing constraints on these elements, the method effectively reduces redundancy compared to controlling all siphons. Experimental results demonstrate that our analytical outcomes are consistent with those derived from other methods.

- (3)

- A method for identifying optimal constraints based on thread and dead transition cycle analysis is proposed, and generalized patterns for scenarios involving partially parameterized systems are summarized.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 proposes the methodology which includes the notations involved in this paper, a thread-based analytical approach for system deadlock, and how to identify optimal constraints. The experimental results about two examples, the comparison of existing methods in other references and the overall path based on thread–circuit analysis, are provided in Section 3. Section 4 concludes the paper.

2. Methodology

2.1. Petri Nets

A Petri net (PN) is a quadruple N = (P, T, F, W), where P is the set of places, T is the set of transitions, is the flow relation of the net, and assigns to each arc a weight. . If for any , N is an ordinary Petri net. Otherwise, it is a general Petri net.

A marking of N is a mapping from P to . represents the number of tokens in place p. If M(p) < W(p, t), , it indicates that p is insufficiently marked under M. A nonempty set is a siphon if . A siphon is minimal if there is no siphon contained in it as a proper subset. The sum of tokens in all places in S is denoted by M(S), i.e., . (N, M0) is called a net system or marked net and M0 is called an initial marking of N.

A transition is enabled under the marking M if and , which can be denoted as . The set of all markings reachable from M0 is called the reachability set represented by R(N, M0). If firing t at M leads to , it is denoted as . A transition is live at M if , . A transition is dead at M if ; t is disabled at . If , t is live at any reachable marking of the net N; then N is live.

Among the many Petri nets that have been proposed, the classic one is the S3PR introduced by Ezepleta. Based on this type of network, many related models have been derived. Much of the prior work has concentrated on a particular class of acyclic Petri nets—S3PR [18,19,20,34]. The S3PR does not contain cycles; when cycles are permitted, it becomes its superclass-S*PR. The Petri net class Gadara is essentially a subclass of S*PR with these two constraints [29]. Gadara nets are very similar to S3PR, but with fewer structural constraints. For instance, they allow the presence of cycles which makes them more general than S3PR [35].

2.2. Thread Analysis of System Models

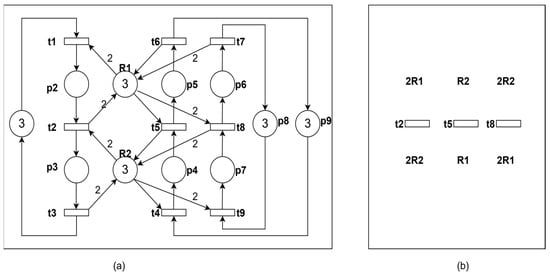

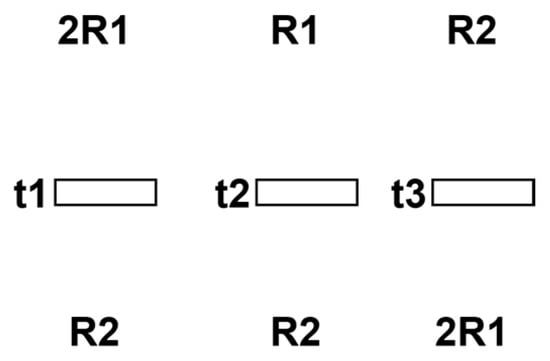

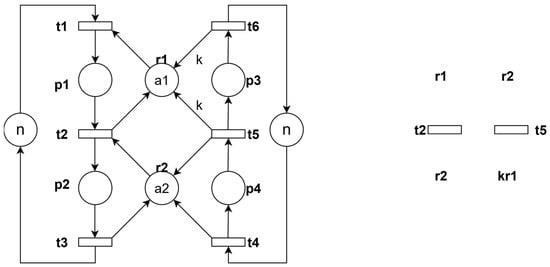

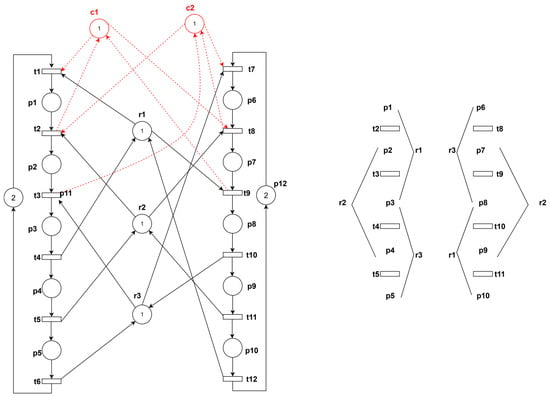

Figure 1 is a general Petri net which has 2 resource places R1 and R2. In order to facilitate analysis of multi-threading, we analyze the liveness and deadlock of the system model from the perspective of threads. According to the order in which each thread uses resources, as shown in the t1 → p2 → t2 → p3 → t3 thread in Figure 1a, it can be represented as the first column on the left in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

(a) A Petri net model; (b) simplified thread diagram.

Taking the leftmost thread of Figure 1b as an example: if t2 is a dead transition, this occurs because the required amount of resource R2 to enable t2 is insufficient (i.e., other threads cannot release ≥2 units of R2). Consequently, t8 in the third thread becomes dead. Following this logic, we can identify a set of input resource places composing dead transitions termed the “resource cycle” corresponding to dead transitions. Conversely, if t2 is enabled, all its input places must satisfy the condition M(p) ≥ W(p,t). In this case, the operational place p2 associated with R1 in the leftmost thread is considered marked.

Let {x1, x2, …, xm} be the threads of a net N and {r1, r2, …, rn} be a set of resources in N. If is non-enabled, is called a resource cycle corresponding to dead transition, referred to as a resource cycle in the subsequent content of this paper.

Theorem 1.

Given a well-marked Petri net (N, M0), if t is dead at , then there must exist a resource cycle Ω and its corresponding siphon is minimal.

Proof.

According to our thread-based analysis method, if is non-enabled under in a thread, this must be caused by insufficient resources. When multiple threads wait for each other’s resources, the input resource places of dead transitions will form a set , namely the resource cycle corresponding to the dead transitions. When are determined, the siphons are consequently determined. By tracing backward from the input transitions of the resource places in resource cycle Ω to incorporate appropriate operational places into the siphon, if Ø, then . The so-called minimal siphon here refers to the minimal siphon among siphons composed of all resource places in Ω. Our research specifically focuses on the resource cycle which is strongly connected. According to Theorem 7 of Reference [17], it can be conclusively demonstrated that the derived siphon is minimal, thereby validating the theorem. □

According to the theorem, we can first identify the minimal siphons corresponding to such dead transitions and impose constraint control on them. The constraint is a restriction imposed on the places in a Petri net to prevent the system from entering a deadlock state, typically expressed in the form of inequalities. This approach partially mitigates the redundancy caused by controlling all siphons. Furthermore, it can be verified that the analytical results based on our methodology are consistent with those obtained through other approaches.

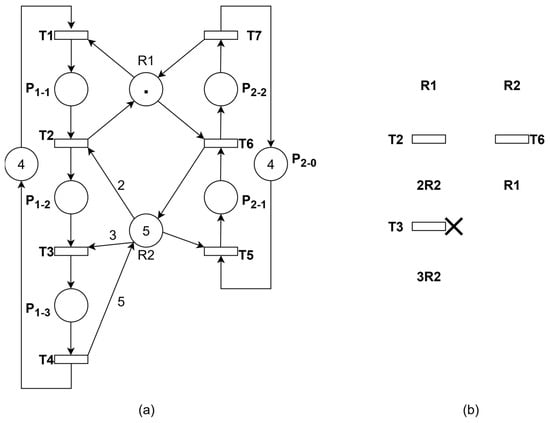

Theorem 2 in [36] describes liveness enforcement and the addition of control strategies from the perspective of siphons, which involves two steps: first, computing the bad siphons and markings that satisfy Theorem 2, and then calculating the controls to be added to the net. As can be seen from the example in Figure 3 of [36], T3 is dead at bad marking . According to our thread-based methodology for analyzing this net model, the thread diagram is shown in Figure 2b. If T3 is a dead transition (denoted by “×” in Figure 2b), it indicates insufficient R2 resources to enable T3. Since the second thread can only release one R2 resource, there is no need to impose restrictions on it. Moreover, R2 doesn’t need to form a resource cycle with other resource places—it constitutes a minimal siphon by itself when combined with its corresponding operation places, which is . Therefore, the bad siphon requiring control constraints is precisely D. This is consistent with the example analysis results of Figure 3 in [36].

Figure 2.

(a) Example in Reference [36]. (b) Thread diagram of Figure 2a.

Theorem 2.

Given a well-marked Petri net (N, M0), if there exists no resource cycle corresponding to dead transitions, then the net is deadlock-free.

Proof.

Proof by contradiction. Assume that the Petri net (N, M0) contains a deadlock, whether partial or global. Clearly, there must exist dead transition t. In a resource allocation system, this situation must arise due to resource competition within threads. Consequently, there exists a resource cycle associated with this deadlock—specifically, the so-called resource cycle corresponding to the dead transitions according to Theorem 1. However, this contradicts the given condition that no such resource cycle exists in the net. Therefore, it can be concluded that (N, M0) is deadlock-free, and the lemma evidently holds. □

Liao et al. [6] proposes that a multithreaded program that can be strictly modeled as a Gadara net is deadlock-free if and only if its associated Gadara net does not contain a certain type of siphon. In this paper, the “certain type” of siphon refers specifically to the minimal siphons corresponding to resource cycles identified through dead-transition-cycle analysis—precisely the “bad siphons” we aim to constrain. Thus, we can focus on detecting whether such siphons exist in the net model. If no such siphons are detected, the original program is proven deadlock-free. Otherwise, we can synthesize control logic to prevent these siphons from becoming reachable, thereby avoiding their associated deadlocks [37].

Based on this, we can derive a straightforward method for determining liveness in the net: assume that a transition t is dead in a given thread, and then search for its corresponding resource cycle. If no such resource cycle exists, t is live. By iterating this process for each thread, we can comprehensively determine the liveness of the net.

The above analysis demonstrates that identifying dead transition cycles constitutes a critical step.

If a dead transition cycle is found, then the siphon containing all resource places in that cycle is a minimal siphon. Notably, the identification of siphons is independent of both the initial marking and arc weights. Once the resource places are determined, the siphons are uniquely determined. We formalize this process into two steps:

- (1)

- Finding all resource cycles corresponding to dead transitions;

- (2)

- For each cycle, construct the minimal siphon containing all its resource places by tracing backward through input transitions of the resource places and incorporating appropriate places into the siphon selectively.

Algorithm 1 constitutes a component of the whole methodology, specifically tasked with identifying the minimal siphons corresponding to each resource cycle. Therefore, it is crucial to first identify the resource places corresponding to dead transitions. Starting from the resource places, all their input transitions are identified. If an input transition is not enabled under the current marking, it is added to the dead transition set T-dead. In this step, the computational complexity is bounded by the number of transitions, resulting in a complexity of O(|T|). Then, add to Ω. Within the strongly connected graph, there is only one such operation place. Therefore, the computational complexity of this step is bounded by the number of places, which is O(|P|). In summary, the overall computational complexity of the algorithm is O(|P| + |T|), meaning it scales linearly with the size of the net model.

| Algorithm 1: Minimal Siphon Identification via Dead Transition Cycles |

| Input: a Petri net N = (P, T, F, W) Output: the set of minimal siphons Ω corresponding to dead transition (1) T-dead = Ø; (2) Ω = Ø; (3) the set of resource places ; the set of operation places ; (4) traverse each thread, for each do (5) if t is non-enabled under M then (6) T-dead = ; (7) ; (8) end if (9) end for (10) While ( Ø) do (11) (12) if Ø then (13) ; (14) end if (15) end while (16) Output: Ω; |

2.3. Optimal Constraint

Building upon the analytical method introduced in the previous section, this section examines the liveness of the net system from the perspective of dead transition cycle detection, and investigates methods for identifying optimal constraints.

2.3.1. Analytical Approach for Identifying Constraints

First, analyze the process and results from some relatively simple examples, and then summarize the rules. The following discussion primarily illustrates constraint derivation methods based on these cases.

Example 1.

Take Figure 1 as an example, the constraints present in the initial state are as follows:

Assuming t2 is a dead transition, the number of R2 resources released by the other two threads cannot be greater than or equal to 2. Therefore, the first and third threads from the left cannot execute simultaneously—that is, t2 and t8 cannot both be live. Hence, the operation places corresponding to these two threads cannot be marked at the same time. Therefore, the states we need to prohibit are those of . Integrating with the initial state constraints, the resulting constraint is .

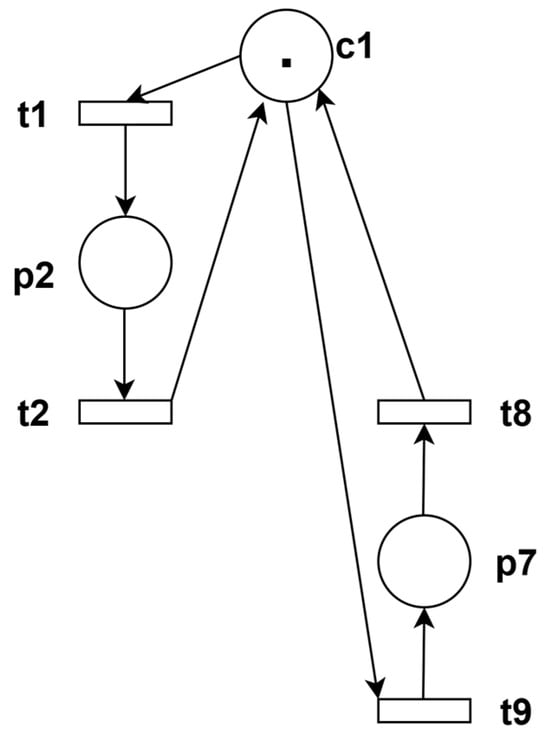

Based on the obtained constraints, a controller is added to the system model to ensure the resulting net system satisfies the aforementioned constraint inequalities. An illustration of the controller added in this example is shown as Figure 3, .

Figure 3.

Add control place c1.

After adding the controller, it is necessary to further verify the liveness of the resulting net system. Again assuming t2 is a dead transition, no corresponding deadlock circuit can be found in this case. Therefore, the assumption does not hold, and t2 is not a dead transition. Similarly, by sequentially examining each transition in the thread diagram, if no deadlock circuit exists for any transition in the net, then the net is live.

Example 2.

The constraints of the initial state are shown as Inequality (1). The possible values of M(p2) are 0, 1, and 2, while M(p7) can take values 0 or 1, resulting in a total of 6 possible combined states. According to thread analysis, the condition where p2 contains 2 tokens and p7 holds 1 token represents an undesirable marking. We need to prohibit this particular state while preserving all other five valid states. Then we derive the constraint .

From the above examples, it can be observed that p1, p2, and p3 are the operation places corresponding to individual threads in the net model. Under the initial state constraints M(p1) ≤ a, M(p2) ≤ b and M(p3) ≤ c, and while preserving all other desirable states, the required constraint is as follows:

M(p1) + M(p2) + M(p3) ≤ a + b + c − 1

2.3.2. Discussion on Constraints for More Complex Nets

The examples mentioned above are still relatively simple network models, involving fewer resources and correspondingly fewer operation places. Moreover, each operation place occupies the resources of only one resource place at any given time. Next, we will discuss more complex network systems that involve more resources and situations where an operation place simultaneously utilizes multiple resources.

Example 3.

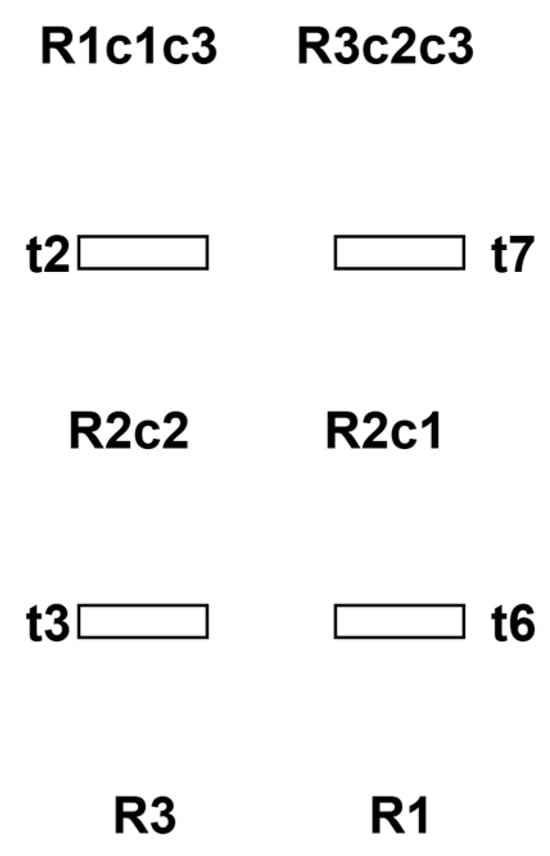

The following presents only the thread schematic diagram for analysis and discussion, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Thread diagram of Example 3.

The initial state of resource places is M(R1) = 4, M(R2) = 1. The operation places corresponding to each thread from left to right are as follows: p1, p2, p3. The constraints of the initial state are defined as M(p1) ≤ 2, M(p2) ≤ 4, and M(p3) ≤ 1.

- (1)

- When p1 is marked once, assuming t1 is a dead transition, then the resource R2 in the third thread cannot be released, so t3 is a dead transition. Since M(p1) = 1 at this time, the remaining number of R1 resources is 2. If t3 is a dead transition, it is necessary to prevent the second thread from releasing an R1 resource, so t2 must also be disabled. Thus, t1, t2, and t3 form a deadlock cycle, meaning the net is non-live. As shown above, the operation places corresponding to the three threads cannot be marked simultaneously. The state where M(p1) = 1, M(p2) = 1, and M(p3) = 1 must be prohibited. Therefore, the constraint can be derived as follows:M(p1) + M(p2) + M(p3) ≤ 2.

- (2)

- When p1 is marked twice, following the same analysis method as above, the states that must be prohibited are M(p1) = 2, M(p3) = 1. Then the constraint can be derived as follows:M(p1) + M(p3) ≤ 2.

- (3)

- Similarly, when M(p2) = 3 or 4 and M(p3) = 1, it also represents a forbidden bad state. The constraint is as follows:M(p2) + M(p3) ≤ 3.In summary, the final overall constraint is as follows:

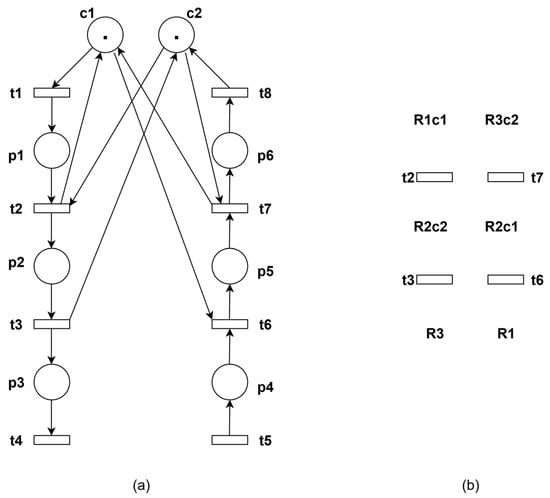

Example 4.

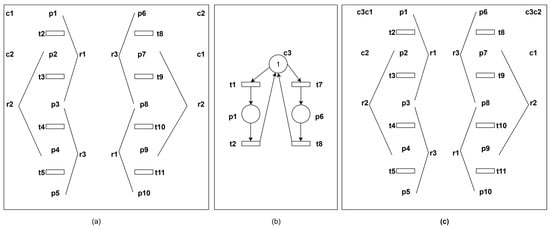

In this example, the initial markings of all resource places are 1, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Example 4 (a Petri net and its thread diagram).

Following the aforementioned analytical approach, the constraints are as follows: M(p1) + M(p5) ≤ 1 and M(p2) + M(p4) ≤ 1.

A scenario where an operation place simultaneously occupies multiple resources can be analyzed as follows: following the constraints obtained in Example 4, control places c1 and c2 are added as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

(a) Add control places c1 and c2; (b) thread diagram after adding c1 and c2.

The schematic diagram of the threaded net model after adding controllers is shown in Figure 6b. When control places are treated as resources, the resulting state corresponds to the case where an operation place simultaneously occupies multiple resources. The analysis method remains similar to the previous approach.

Perform hypothesis testing on transitions in each thread. For instance, assuming t2 is a dead transition, then t7 must also be disabled. Then, the constraint for the deadlock cycle formed by t2 and t7 is M(p1) + M(p4) ≤ 1. Based on the derived constraints, we further introduce a control place c3 to the system to enforce the restriction that operation places p1 and p4 cannot be marked simultaneously. The schematic diagram of threads in the resulting controlled net is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Thread diagram after adding c3.

Next, it is necessary to perform liveness analysis on the controlled net system after adding the control places. Following the dead transition hypothesis testing method described earlier, if we assume each transition in every thread is dead and no corresponding deadlock cycle exists, then the controlled net is guaranteed to be live.

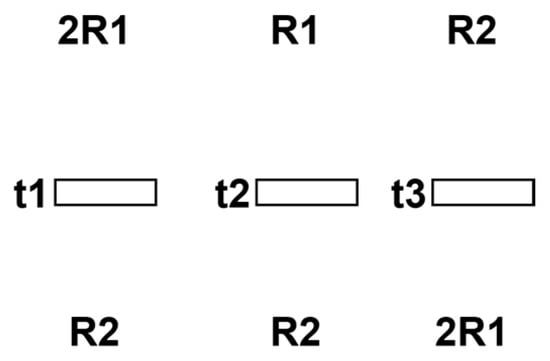

2.3.3. Summary of General Rules for Optimal Constraints

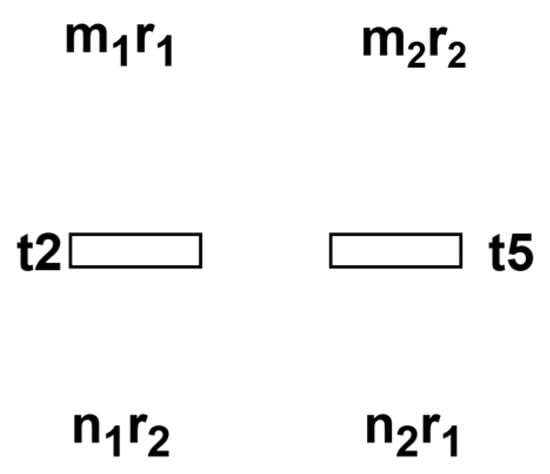

- Partial arcs with weights

In the special case shown in Figure 8, only some arcs have non-unit weights. According to the above thread analysis method, assuming t2 is dead, all units of resource r2 are occupied by the second thread. Consequently, the operation place p4 takes the value a2. In this case, t2 is guaranteed to be unfirable. Under the condition where M(p4) = a2, as M(p1) takes values from 1 to a1, we must identify all bad markings a1 − k + 1 ≤ M(p1) ≤ a1 among these combined states that may potentially lead to deadlocks. These k states must be prohibited. We derive the optimal constraint as follows:

Figure 8.

A Petri net with weighted arcs and its thread diagram.

- 2.

- Parameter Generalization

For the example in Figure 8, this section discusses the generalization of parameters for net systems involving two resources. The thread schematic diagram is shown as Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Parameterized thread schematic diagram.

For clarity in our discussion, we denote the marking values of the operation places M(p1) and M(p4) initially associated with the resource places in the two threads as x1 and x2, respectively. The initial markings are M(r1) = a1 and M(r2) = a2.

Following the dead transition hypothesis analysis method, we proceed as follows: assuming transition t2 is a dead transition, the remaining r2 resources are insufficient for the first thread to proceed, and the remaining r1 resources are also inadequate for the second thread to execute. Therefore, the potentially deadlock-inducing bad states can be characterized as follows:

Namely,

For all unknown parameters in the system of inequalities, summarizing a universal law is indeed highly complex and challenging. We primarily focus on analyzing and discussing specific cases, laying the groundwork for solving more general scenarios in the future. For the four weights m1, m2, n1, and n2, the example in Figure 8 corresponds to the case where m1 = m2 = n1 = 1 and n2 = k. When n1 = 1, the system is guaranteed to be deadlock-free as long as . Conversely, if m2x2 = a2, the system could encounter the following undesirable states which might result in a deadlock: the set of values for (M(p1), M(p4)) is . So, the constraints are as follows:

Future work could involve further discussion and analysis of this constraint under various scenarios, as it is a complex and worthwhile issue that merits in-depth research. Obtaining more generalized parametric constraints would be a highly meaningful contribution.

3. Experimental Results

In this section, we use two examples to discuss the applicability of the proposed method.

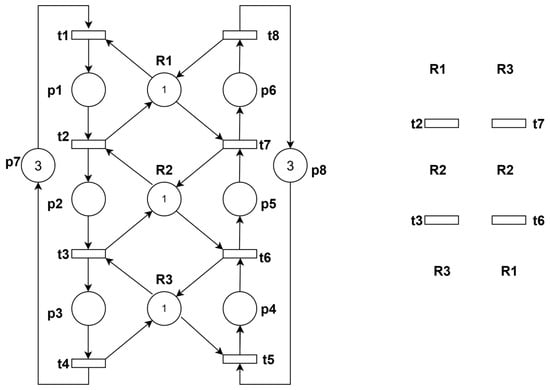

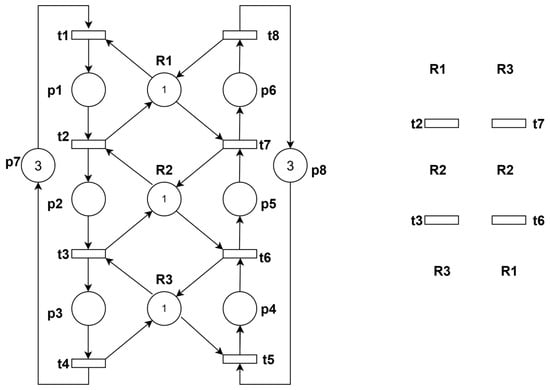

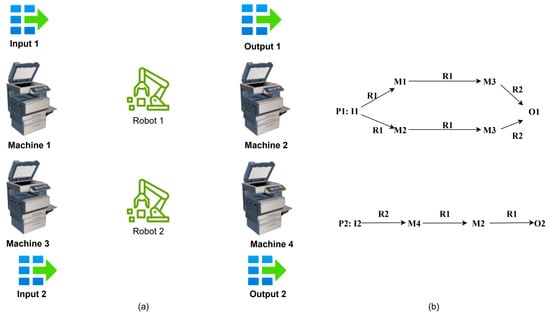

Example 5.

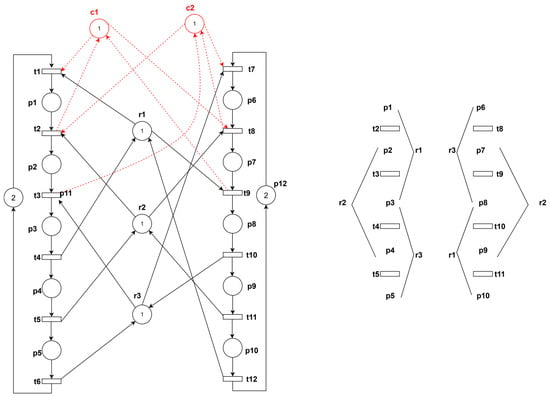

First, we illustrate the general analysis workflow through an illustrative example as shown in Figure 10. The figure shows a Gadara net with a controller added. The solid lines represent the original Gadara net, while the added control part is indicated by dashed lines. It can be observed that, unlike the previous example, one resource is used in at least two operation places within a single thread before being returned.

Figure 10.

A Gadara net and thread schematic diagram of its original net.

The resource r1 shown in the diagram is released after being used by the operation places p1, p2, and p3, and the resource r2 shown in the diagram is released after being used by the operation places p2, p3, and p4. This means that p3 simultaneously utilizes resources r1, r2, and r3. According to the thread-based analysis method, assuming t2 is a dead transition, the resource r2 is occupied by the right thread. Consequently, t9 cannot occur, and p1 and p7 cannot be marked simultaneously. This results in a deadlock cycle corresponding to t2 and t9. Therefore, the constraint derived is M(p1) + M(p7) ≤ 1. Similarly, assuming t3 is a dead transition, the constraint derived is M(p2) + M(p6) ≤ 1. The left thread starts from t4, and the resources occupied earlier are sequentially released without requiring new resources. Therefore, no hypothetical analysis is needed for this thread. The same analysis applies to the right thread, and the constraints obtained are identical to the previous two constraints.

Based on the constraints obtained above, control places c1, c2 are added, as shown by the dashed lines in Figure 10. And its thread diagram is shown in Figure 11a.

Figure 11.

(a) Thread diagram after adding c1 and c2; (b) add control place c3; (c) thread diagram of the net after adding c3.

Then, following the same hypothetical analysis, the constraint derived is M(p1) + M(p6) ≤ 1. A control place c3 is then added. Conducting the above method on it, we can know the net contains no deadlock cycles.

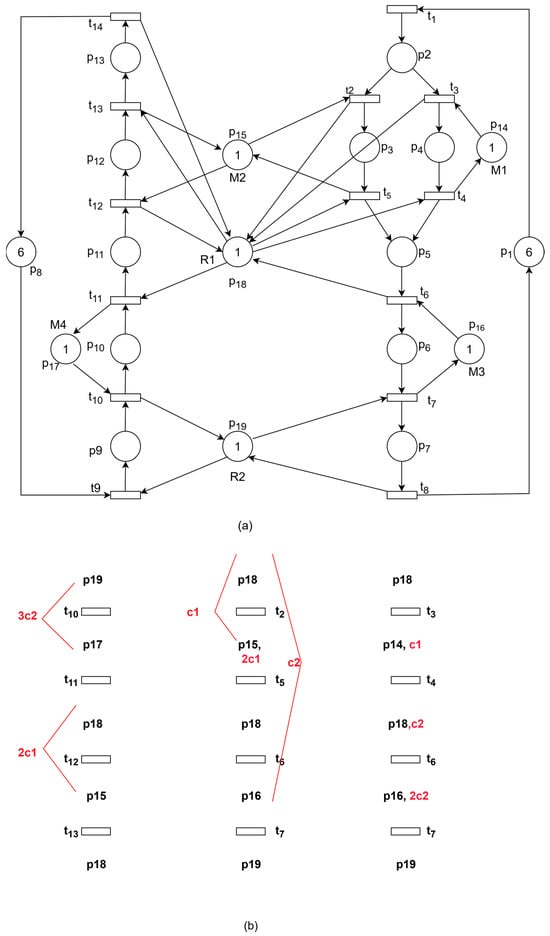

Example 6.

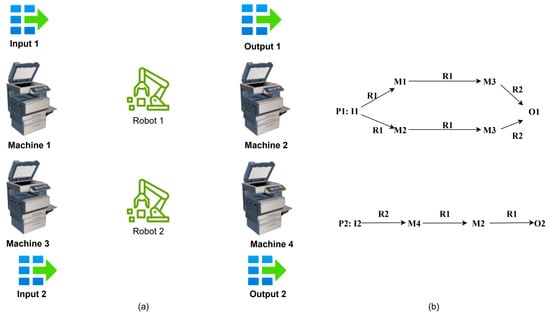

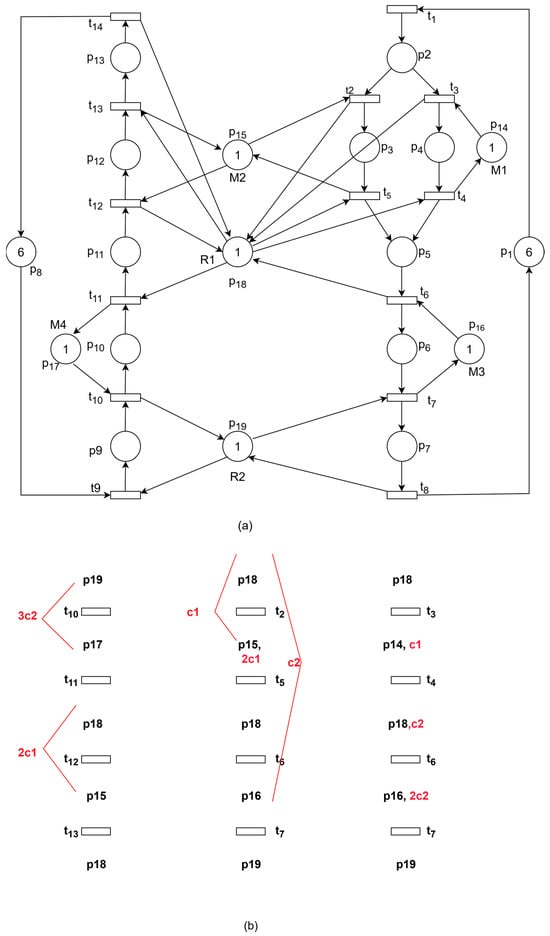

Figure 12a shows an FMS example which has 2 loading buffers (I1, I2), 2 robots (R1, R2), 4 machines (M1, M2, M3, M4), and 2 uploading buffers (O1, O2). It has 2 production sequences as shown in Figure 12b. Its PN model which has been studied in [32] is depicted in Figure 13a. It has 19 places which consist of P0 = {p1, p8}, PR = {p14,…, p19}, PA = {p2,…, p7, p9,…, p13}, and 14 transitions. The initial markings of places in PR are all one, which represents that the robot can hold one part at a time and the machine can process one part at a time.

Figure 12.

(a) An FMS example; (b) its production sequences.

Figure 13.

(a) Petri net model of Example 6; (b) its thread diagram.

We have established a thread diagram of the system based on the PN model, which is presented in Figure 13b as the black part. The red part represents the controller added.

According to the aforementioned thread analysis methodology, the derived comprehensive constraints are as follows: 2M(p11) + 2M(p12) + 2M(p3) + M(p2) + M(p4) ≤ 3, 3M(p9) + 3M(p10) + M(p2) + 2M(p3) + M(p4) + 2M(p5) + 2M(p6) ≤ 9. The added controllers are presented in Table 1. We compared the reachable state analysis of the system before and after adding the controller. Before the system was added, there were 282 reachable markings, including 77 bad markings (of which 16 were deadlocked states, and 61 would evolve into deadlocks). After the controller was incorporated, the number of deadlock states was reduced without diminishing the quantity of good states in the system, as shown in Table 2. The above results are carried out by using the tool TINA (version 3.8.5) on a computer running Windows 10 with an Intel core 2.1 GHz CPU and 8 GB of memory.

Table 1.

Control places added for the PN in Example 6.

Table 2.

Comparison of state space analysis before and after adding controllers.

Compared with the methods in [26,31,38,39], the proposed method in this paper can make the net deadlock-free by adding fewer controllers, without reducing the number of good states, as shown in Table 3. From the point of structural complexity to the system, it performs better than other methods. But its disadvantage is computational complexity. The complexity of the problem becomes NP-hard when the net model has too many constraints. So, it is not applicable for large-scale systems.

Table 3.

Comparison of several methods for Example 6.

The deadlock cycles discussed above are essentially the minimal siphons corresponding to the resource places in the cycle, which is the true focus of the analysis. It is important to note that if two or more controllers are added, interactions between controllers may occur. Thus, siphons containing two or more controllers require further analysis and control.

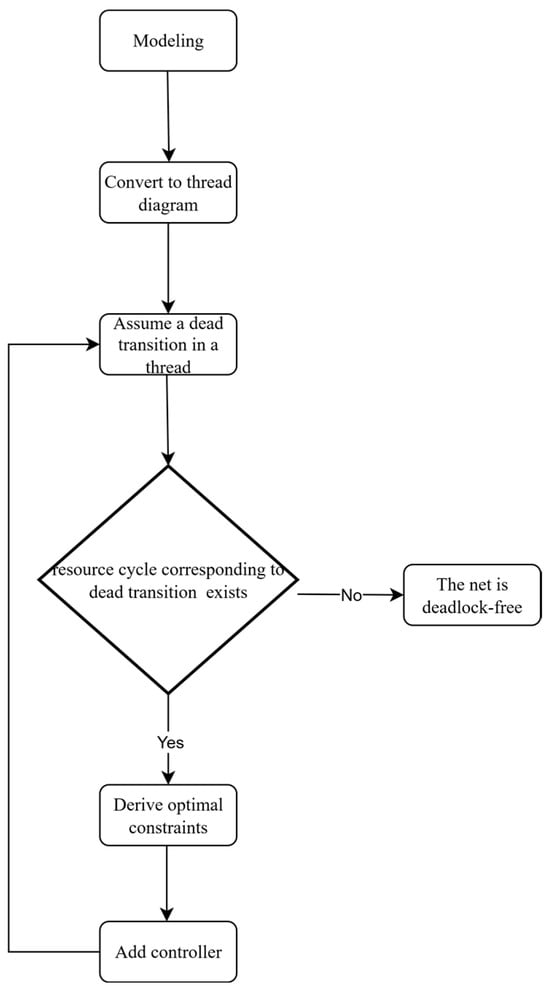

Therefore, we have summarized the overall path based on thread and cycle analysis, as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Thread-circuit analysis path diagram.

4. Conclusions

This paper proposes a thread-based approach for analyzing system deadlocks within the Petri net modeling framework. Particularly, the discussion scope is extended to more general classes of nets rather than being limited to specific subclasses. By examining critical transitions in individual threads, the method identifies resource cycles and minimal siphons associated with dead transitions, determines optimal constraints for controller integration, and ultimately achieves deadlock-free system operation. The effectiveness of the proposed methodology is demonstrated through illustrative case studies. The deadlock handling process in this paper essentially iterates through repeated cycles of the “hypothesis analysis → constraint derivation → controller augmentation → liveness reverification”. During the phase of identifying optimal constraints, the inherent complexity of generalized Petri nets makes it challenging to derive universally applicable parameterized constraints. Consequently, the constraint patterns summarized in this study specifically address partially generalized parameter scenarios. More comprehensive generalizations remain subject to further investigation and analysis.

The performance of a deadlock prevention policy is always evaluated by considering the following criteria: behavior permissiveness, structural complexity, and computational complexity. In this paper, structural complexity is a major concern, given that the behavior permissiveness and computational complexity remain nearly identical. The structural complexity of a supervisor is usually measured by the number of monitors. In the comparative results, the proposed method adds the fewest monitors while achieving equivalent permissiveness, making it both maximally permissive and structurally minimal. But its problem is that its computational complexity becomes NP-hard when the net size is very large and the net model has too many constraints. So, it is inapplicable for large-scale systems.

The computational cost grows exponentially with model size in the worst case. In such cases, future research could focus on, for instance, starting with certain subclasses of Petri nets. Their distinctive properties may render the considered problem more tractable, and these subclasses could be applied to some large-scale FMSs. Alternatively, the entire problem could be decomposed into multiple subproblems and addressed individually. In practice, the method can be readily applied to large-scale FMSs by using modular or hierarchical Petri net decomposition, a standard strategy that allows the independent analysis of each subsystem while preserving global liveness. This hierarchical framework effectively mitigates computational explosion and serves as a complexity reduction strategy without altering the theoretical foundation of the proposed controller design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.G. and Y.N.; methodology, X.G. and Y.N.; software, X.G.; validation, X.G.; formal analysis, X.G.; investigation, X.G.; resources, X.G.; data curation, X.G.; writing—original draft preparation, X.G.; writing—review and editing, X.G. and W.W.; visualization, X.G.; supervision, Y.N.; project administration, X.G. and Y.N.; funding acquisition, X.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Key Scientific Research Project of Suzhou University (2023yzd14, 2023yzd15, and 2024yzd15).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alzalab, E.; Abubakar, U.; E, H.; Li, Z.; El-Meligy, M.; El-Sherbeeny, A. Modeling of fault recovery and repair for automated manufacturing cells with load-sharing redundant elements using Petri nets. Processes 2023, 11, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Chai, B.; Ran, K.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wu, W.; Wang, K.; Ni, Y. Research on a Multi-Dimensional Information Fusion Mechanical Wear Fault-Diagnosis Algorithm Based on Data Regeneration. Sensors 2025, 25, 3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, W.; Tseng, C.; Tan, K.; Pan, Y. Design of a novel transition-based deadlock recovery policy for flexible manufacturing systems. Processes 2025, 13, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, H. Extended Place-Invariant Control in Automated Manufacturing Systems Using Petri Nets. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2020, 52, 1807–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaid, H.; Al-Ahmari, A.; Li, Z.; Davidrajuh, R. Single controller-based colored petri nets for deadlock control in automated manufacturing systems. Processes 2020, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Wang, H.; Chao, H.; Stanley, J.; Kelly, T.; Lafortune, S.; Mahlke, S.; Reveliotis, S. Concurrency bugs in multithreaded soft-ware:Modeling and analysis using Petri nets. Discret. Event Dyn. Syst. 2013, 23, 157–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Feng, Y.; Ren, S.; Cao, Y.; Xing, K.; Yang, Y. Deadlock control for flexible assembly systems with multiple resource requirements and separately-loaded parts. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 9275–9284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z. Design of online supervisors for enforcing diagnosability in Petri nets with unknown initial markings. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 11108–11120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Chi, X. Automatic construction of Petri net models for computational simulations of molecular inter-action network. npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 2024, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhou, M. A Petri net-based discrete event control of automated manufacturing systems with assembly operations. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2015, 23, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, K.; Wang, F.; Zhou, M.; Lei, H.; Luo, J. Deadlock characterization and control of flexible assembly systems with Petri nets. Automatica 2018, 87, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, A.; Li, Z. A fast algorithm to find a set of elementary siphons for a class of Petri nets. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering, Shanghai, China, 7–10 October 2006; pp. 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, M. On siphon computation for deadlock control in a class of Petri nets. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. A. Syst. Hum. 2008, 38, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, M.; Uzam, M. Deadlock control policy for a class of Petri nets without complete siphon enumeration. IET Control Theory Appl. 2007, 1, 1594–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, Z.; Barkaoui, K.; Al-Ahmari, A. Robustness of deadlock control for a class of Petri nets with unreliable resources. Inf. Sci. 2013, 235, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Zhou, M. Controllability condition of resultant siphons in a class of Petri nets. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part A 2012, 42, 1206–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Zhou, M.; Li, Z. A method to compute strict minimal siphons in S3PR based on loop resource subnets. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 2012, 42, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, Z.; Zhou, M. Liveness of extended S3PR. Automatica 2010, 46, 1008–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, X.; Gu, C.; Uzam, M.; Chen, Y.; Al-Ahmari, A.M.; Wu, N.; Zhou, M.; Li, Z. Design of Optimal Petri Net Supervisors for Flexible Manufacturing Systems via Weighted Inhibitor Arcs. Asian J. Control 2017, 20, 511–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, M. Elementary siphons of Petri nets and there application to deadlock prevention in flexible manufacturing systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. A. Syst. Hum. 2004, 34, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jeng, M.; Xie, X.; Chung, S. A deadlock prevention pollicy for flexible manufacturing systems using siphons. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Seoul, Korea, 21–26 May 2001; pp. 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkoui, K.; Pradat-Peyre, J. On liveness and controlled siphons in Petri nets. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Application and Theory of Petri Nets, LNCS, Osaka, Japan, 24–28 June 1996; pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Jeng, M. ERCN-merged nets and their analysis using siphons. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. A 1999, 9, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricas, F.; Garcia-Valles, F.; Colom, J.; Ezpeleta, J. A Petri net structure-based deadlock prevention solution for squential resource allocation system. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Barcelona, Spain, 18–22 April 2005; pp. 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jeng, M.; Xie, X.; Chung, S. Siphon-based deadlock prevention policy for flexible manufacturing systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. A. Syst. Hum. 2006, 36, 1248–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroddi, L.; Cordone, R.; Fumagalli, I. Selective siphon control for deadlock preveention in Petri Nets. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. A. Syst. Hum. 2008, 38, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, K.; Zhou, M.; Hu, H.; Tian, F. Optimal Petri net-based polynomial-complexity deadlock avoidance policies for automated manufacturing systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. A 2009, 39, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezpeleta, J.; Colom, J.; Martinez, J. A petri net based deadlock prevention policy for flexible manufacturing systems. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1995, 11, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, Z.; Zhong, C. New controllability condition for siphons in a class of generalised Petri nets. IET Control Theory Appl. 2010, 4, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo, J.; Colom, J. Resource allocation systems: Some complexity results on the S4PR class. In Proceedings of the Formal Techniques for Networked and Distributed Systems, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Paris, France, 26–29 September 2006; pp. 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzam, M. An Optimal Deadlock Prevention Policy for Flexible Manufacturing Systems Using Petri Net Models with Resources and the Theory of Regions. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2002, 19, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzam, M.; Zhou, M.C. An improved iterative synthesis method for livenessenforcing supervisors of flexible manufacturing systems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2006, 44, 1987–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, A.; Rezg, N.; Xie, X.L. Design of a live and maximally permissivePetri net controller using the theory of regions. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 2003, 19, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, M.; Wu, N. A survey and comparison of Petri net-based deadlock prevention policies for flexible manufacturing systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C 2008, 38, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezpeleta, J.; Tricas, F.; Garcia-Valles, F.; Colom, J. A banker’s solution for deadlock avoidance in FMS with flexible routing and multiresource states. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 2002, 18, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom, J. The resource allocation problem in flexible manufacturing systems. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Application and Theory of Petri Nets, ICATPN, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 23–27 June 2003; pp. 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Wang, Y.; Stanley, J.; Lafortune, S.; Reveliotis, S.; Kelly, T.; Mahlke, S. Eliminating concurrency bugs in multithreaded software: A new approach based on discrete-event control. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2013, 21, 2067–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, M.; Jeng, M. A Maximally Permissive Deadlock Prevention Policy for FMS Based on Petri Net Siphon Control and the Theory of Regions. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2008, 5, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Khalgui, M.; Mosbahi, O. Design of a maximally permissive liveness enforcing Petri net supervisor for flexible manufacturing systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2011, 8, 374–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).