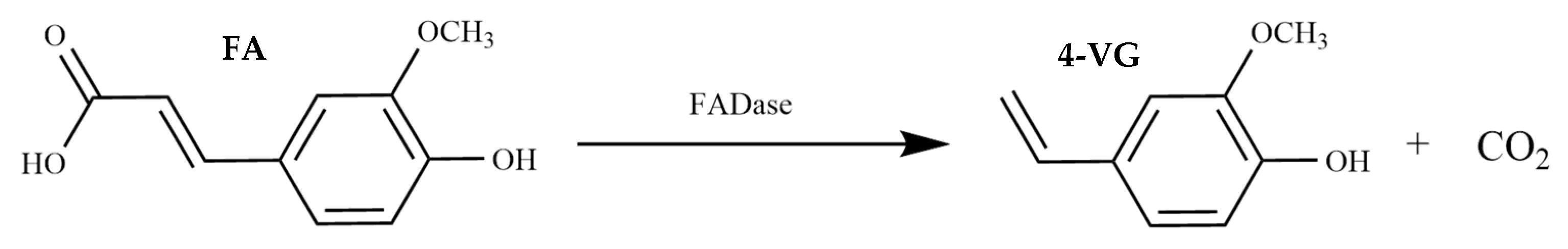

Bioconversion of Ferulic Acid to 4-Vinylguaiacol by Ferulic Acid Decarboxylase from Brucella intermedia TG 3.48

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism

2.2. Culture Medium

2.3. Bacterial Tolerance to FA and Potential Biotransformatio of FA to 4-VG

2.4. Analytical Methods

2.5. FA Decarboxylase Activity (FADase)

- Extracellular crude enzyme: Culture medium was centrifuged at 15,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter and retained as the extracellular enzyme fracture.

- Intracellular crude enzyme: Cell biomass was washed twice with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in the same buffer at a concentration of 0.2 g mL−1 wet biomass (0.2 g wet cell per mL buffer). The resulting cell suspension was sonicated 4 times for 30 s at 20 kHz with 15 s cooling intervals in an ice bath. The lysate was centrifuged at 15,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected and used as the intracellular enzyme fraction.

- Cell wall-associated enzyme: The pellet obtained from the previous centrifugation step was resuspended in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) and centrifuged at 15,000× g and 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet resuspended in the same buffer at a concentration of 0.2 g mL−1 (wet weight), the method was described by dos Santos et al. [2].

2.6. FA Decarboxylase Characterization

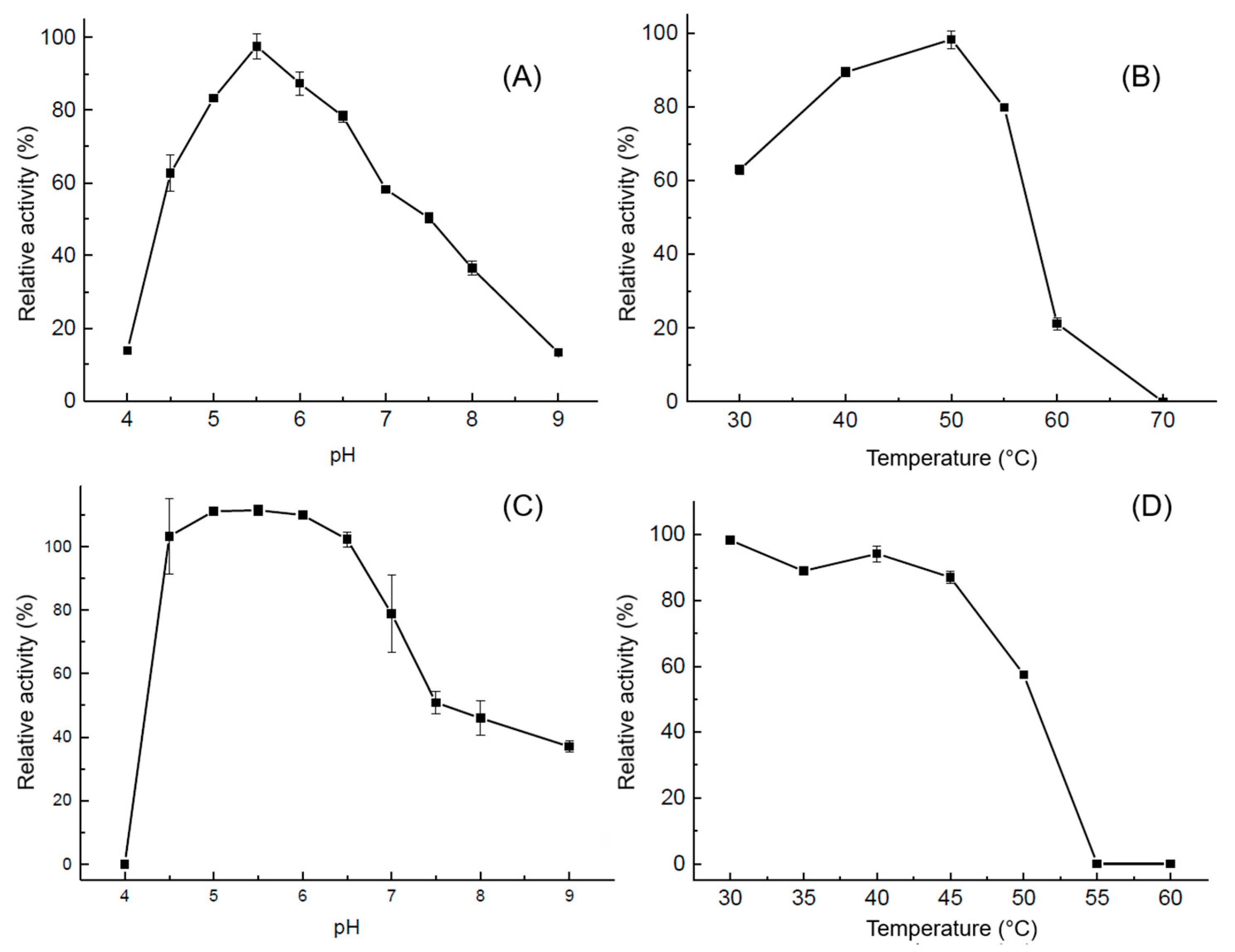

2.6.1. Effect of pH and Temperature on Enzyme Activity and Stability

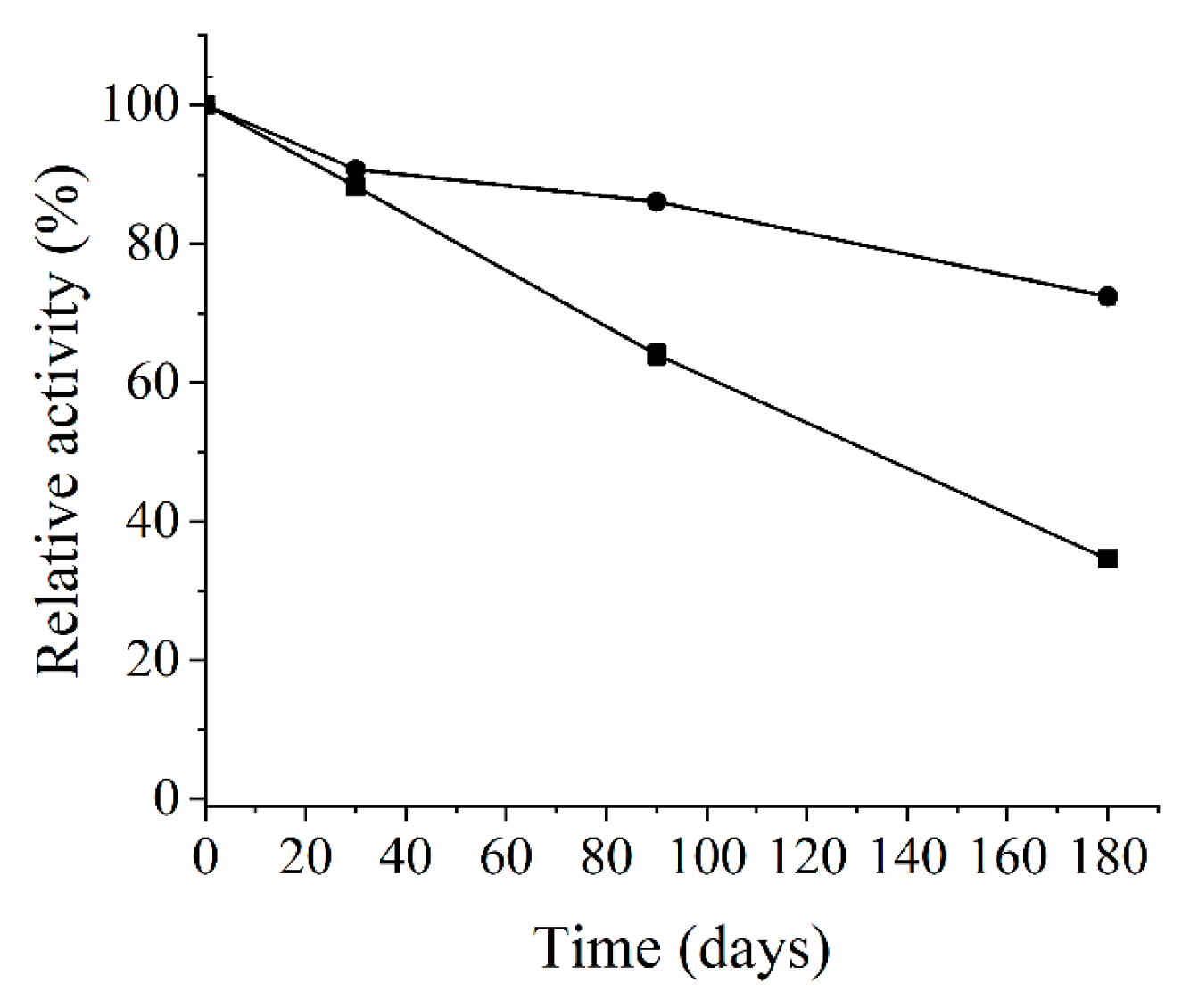

2.6.2. Stability of Enzyme on Storage at Different Temperatures

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

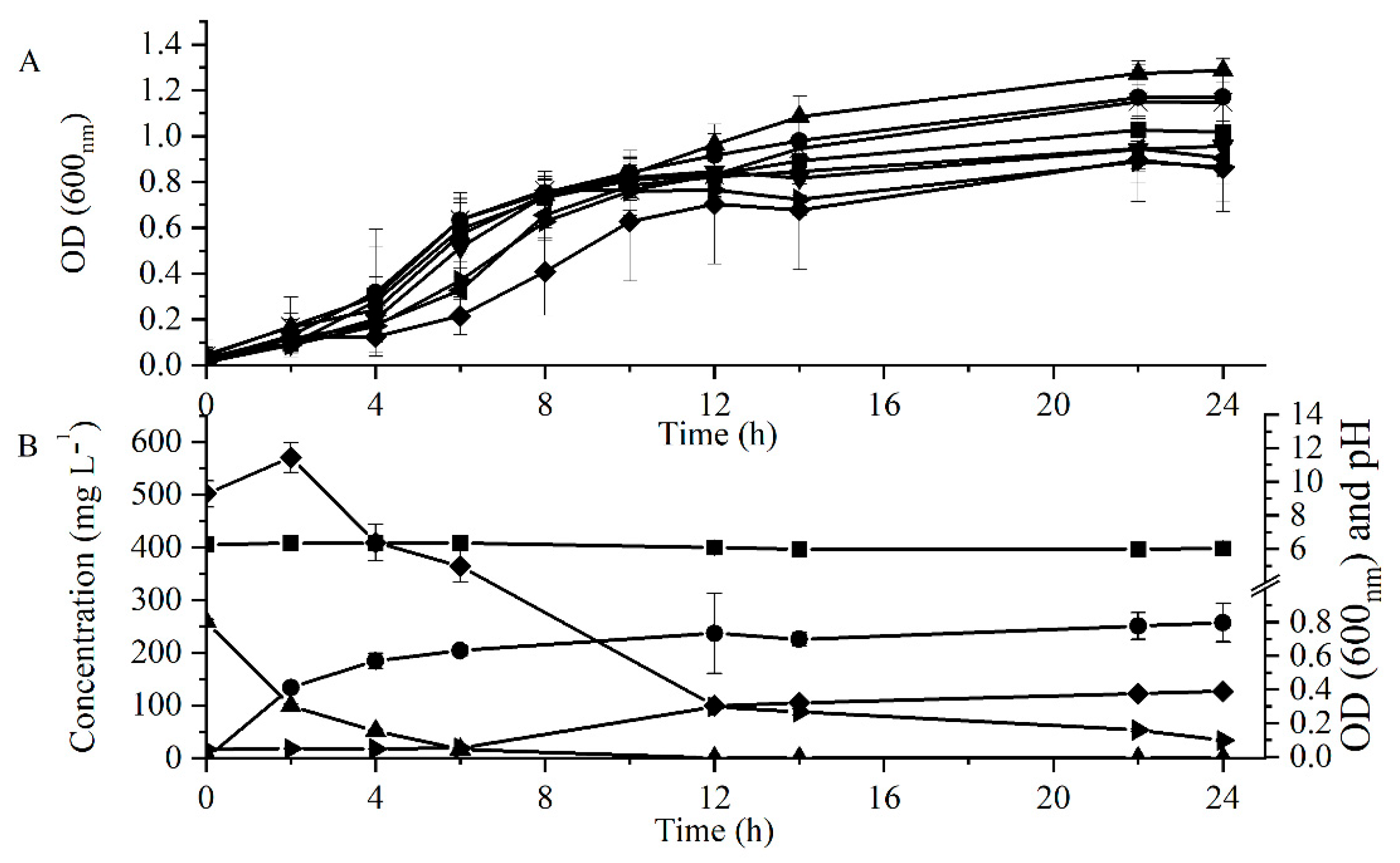

3.1. Studies on Bacterial Tolerance to FA and Its Transformation to 4-VG

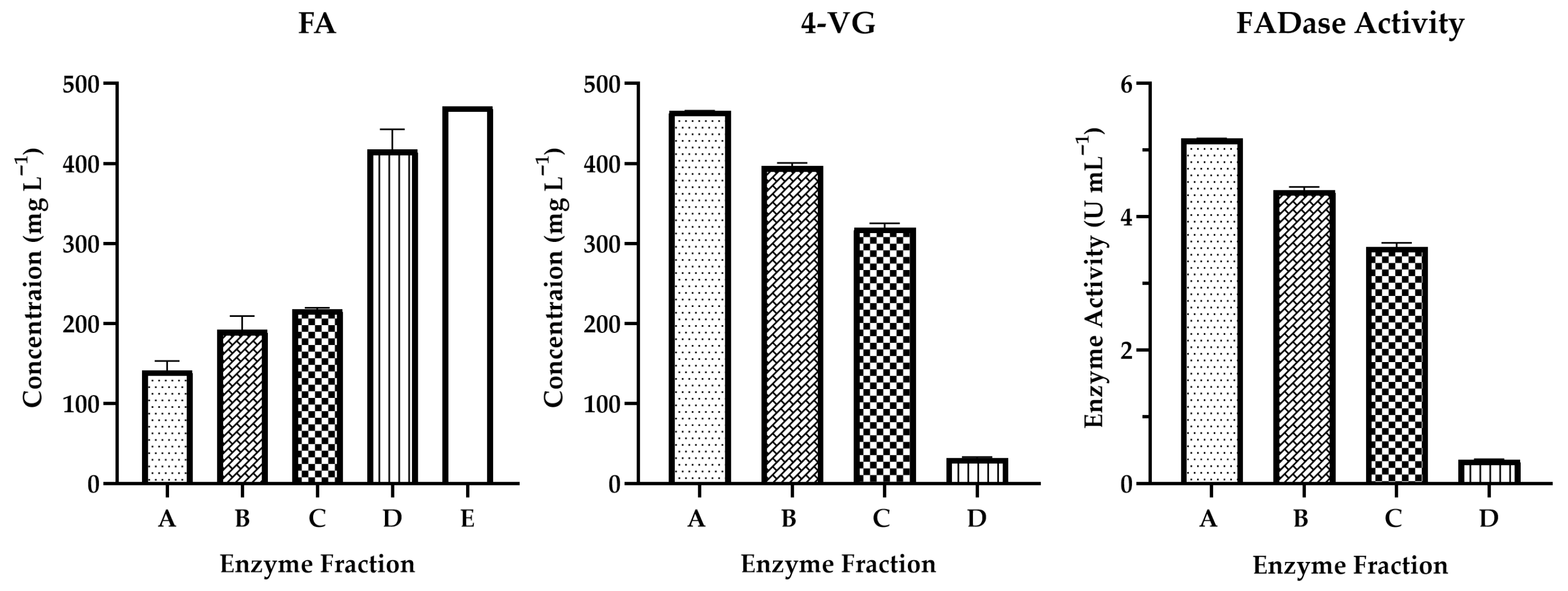

3.2. FA Decarboxylase Activity (FADase)

3.3. Enzyme Characterization

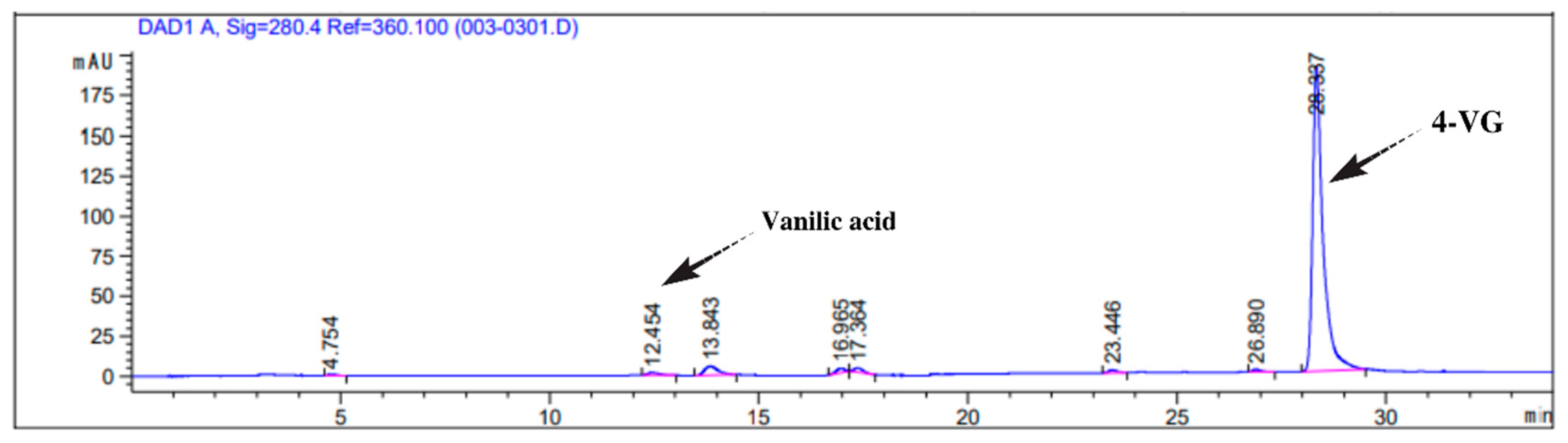

3.4. Products of FADase Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eugenio, M.E.; Martín-Sampedro, R.; Santos, J.I.; Wicklein, B.; Martín, J.A.; Ibarra, D. Properties versus application requirements of solubilized lignins from an elm clone during different pre-treatments. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 181, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, M.B.C.; Scarpassa, J.A.; Monteiro, D.A.; Ladino-Orjuela, G.; Da Silva, R.; Boscolo, M.; Gomes, E. Evaluation of the tolerance and biotransformation of ferulic acid by Klebsiella pneumoniae TD 4.7. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, T.; Wang, G.; Sun, H.; Sui, W.; Si, C. Lignin fractionation: Effective strategy to reduce molecule weight dependent heterogeneity for upgraded lignin valorization. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 165, 113442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, M. The Impact of Simple Phenolic Compounds on Beer Aroma and Flavor. Fermentation 2018, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Long, L.; Ding, S. Bioproduction of high-concentration 4-vinylguaiacol using whole-cell catalysis harboring an organic solvent-tolerant phenolic acid decarboxylase from Bacillus atrophaeus. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfner, R.; Ferge, T.; Kettrup, A.; Zimmermann, R.; Yeretzian, C. Real-Time Monitoring of 4-Vinylguaiacol, Guaiacol, and Phenol during Coffee Roasting by Resonant Laser Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 5768–5773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-K.; Shibamoto, T. Role of Roasting Conditions in the Profile of Volatile Flavor Chemicals Formed from Coffee Beans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 5823–5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Rouseff, R.L. Characterization of Aroma-Impact Compounds in Cold-Pressed Grapefruit Oil Using Time–Intensity GC–Olfactometry and GC–MS. Flavour Fragr. J. 2001, 16, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Li, L. Effect of Drying Methods on Volatile Compounds of Citrus Reticulata Ponkan and Chachi Peels as Characterized by GC-MS and GC-IMS. Foods 2022, 11, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Fadlallah, S.; Gallos, A.; Flourat, A.L.; Torrieri, E.; Allais, F. Effect of ferulic acid derivative concentration on the release kinetics, antioxidant capacity, and thermal behaviour of different polymeric films. Food Chem. 2023, 410, 135395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubbers, R.J.M.; Dilokpimol, A.; Visser, J.; Mäkelä, M.R.; Hildén, K.S.; de Vries, R.P. A comparison between the homocyclic aromatic metabolic pathways from plant-derived compounds by bacteria and fungi. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 107396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detering, T.; Mundry, K.; Berger, R.G. Generation of 4-vinylguaiacol through a novel high-affinity ferulic acid decarboxylase to obtain smoke flavours without carcinogenic contaminants. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.-H.; Lv, S.-W.; Yu, F.; Li, S.-N.; He, L.-Y. Biosynthesis of 4-vinylguaiacol from crude ferulic acid by Bacillus licheniformis DLF-17056. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 281, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramontina, R.; Ciancaglini, I.; Roman, E.K.B.; Chacón, M.G.; Corrêa, T.L.R.; Dixon, N.; Bugg, T.D.H.; Squina, F.M. Sustainable biosynthetic pathways to value-added bioproducts from hydroxycinnamic acids. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 4165–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.L.; Finnigan, W.; France, S.P.; Green, A.P.; Hayes, M.A.; Hepworth, L.J.; Lovelock, S.L.; Niikura, H.; Osuna, S.; Romero, E.; et al. Biocatalysis. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2021, 1, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, P.A.; Gilheany, D.G. The Modern Interpretation of the Wittig Reaction Mechanism. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6670–6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak-Karczewska, M.; Čvančarová, M.; Chrzanowski, Ł.; Kolvenbach, B.; Corvini, P.F.-X.; Cichocka, D. Isolation of two Ochrobactrum sp. strains capable of degrading the nootropic drug—Piracetam. New Biotechnol. 2018, 43, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsivela, E.; Moore, E.R.B.; Kalogerakis, N. Biodegradation of aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons: Specificity among bacteria isolated from refinery waste sludge. Water Air Soil Pollut. Focus 2003, 3, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, S.; Hasnain, S. Reduction of toxic hexavalent chromium by Ochrobactrum intermedium strain SDCr-5 stimulated by heavy metals. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waranusantigul, P.; Lee, H.; Kruatrachue, M.; Pokethitiyook, P.; Auesukaree, C. Isolation and characterization of lead-tolerant Ochrobactrum intermedium and its role in enhancing lead accumulation by Eucalyptus camaldulensis. Chemosphere 2011, 85, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egea, T.C.; Da Silva, R.; Boscolo, M.; Rigonato, J.; Monteiro, D.A.; Grünig, D.; Da Silva, H.; Van Der Wielen, F.; Helmus, R.; Parsons, J.R. Diuron degradation by bacteria from soil of sugarcane crops. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferhat, S.; Alouaoui, R.; Badis, A.; Moulai-Mostefa, N. Production and characterization of biosurfactant by free and immobilized cells from Ochrobactrum intermedium isolated from the soil of southern Algeria with a view to environmental application. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2017, 31, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yan, L.; Wu, Z.; Li, S.; Bai, Z.; Yan, X.; Wang, N.; Liang, N.; Li, H. A Microbial Transformation Using Bacillus subtilis B7-S to Produce Natural Vanillin from Ferulic Acid. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E.T.; Werner, A.Z.; Salvachúa, D.; Singer, C.A.; Szostkiewicz, K.; Rafael Jiménez-Díaz, M.; Eng, T.; Radi, M.S.; Simmons, B.A.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; et al. Adaptive Laboratory Evolution of Pseudomonas Putida KT2440 Improves p-Coumaric and Ferulic Acid Catabolism and Tolerance. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2020, 11, e00143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Ferguson, K.L.; Boyer, D.R.; Lin, X.N.; Marsh, E.N.G. Isofunctional Enzymes PAD1 and UbiX Catalyze Formation of a Novel Cofactor Required by Ferulic Acid Decarboxylase and 4-Hydroxy-3-Polyprenylbenzoic Acid Decarboxylase. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landete, J.M.; Rodríguez, H.; Curiel, J.A.; De Las Rivas, B.; Mancheño, J.M.; Muñoz, R. Gene Cloning, Expression, and Characterization of Phenolic Acid Decarboxylase from Lactobacillus Brevis RM84. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 37, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hördt, A.; López, M.G.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Schleuning, M.; Weinhold, L.-M.; Tindall, B.J.; Gronow, S.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Woyke, T.; Göker, M. Analysis of 1,000+ Type-Strain Genomes Substantially Improves Taxonomic Classification of Alphaproteobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertani, G. Studies on lysogenesis I. J. Bacteriol. 1951, 62, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, L.D.; Haas, H.F. The utilization of certain hydrocarbons by microorganisms. J. Bacteriol. 1941, 41, 653–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Delgado, M.A.; Malovaná, S.; Pérez, J.P.; Borges, T.; García Montelongo, F.J. Separation of phenolic compounds by high-performance liquid chromatography with absorbance and fluorimetric detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2001, 912, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahendhran, K.; Arthanari, A.; Dheenadayalan, B.; Ramanathan, M. Bioconversion of oily bilge waste to polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) by marine Ochrobactrum intermedium. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2018, 4, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Parmar, P.; Goswami, D.; Patel, B.; Saraf, M. Characterization of novel thorium tolerant Ochrobactrum intermedium AM7 in consort with assessing its EPS-Thorium binding. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 388, 122047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, M.; Borges, A.; Teodósio, J.; Araújo, P.; Mergulhão, F.; Melo, L.; Simões, M. The effects of ferulic and salicylic acids on Bacillus cereus and Pseudomonas fluorescens single- and dual-species biofilms. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 86, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.-B.; Wang, J.-L.; Wang, Y.-T.; Zhu, M.-J. Specify the individual and synergistic effects of lignocellulose-derived inhibitors on biohydrogen production and inhibitory mechanism research. Renew. Energy 2019, 140, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.; Saavedra, M.J.; Simões, M. The activity of ferulic and gallic acids in biofilm prevention and control of pathogenic bacteria. Biofouling 2012, 28, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Gu, W.; Huang, J.; Zhang, K.-Q. The metabolism of ferulic acid via 4-vinylguaiacol to vanillin by Enterobacter sp. Px6-4 isolated from Vanilla root. Process Biochem. 2008, 43, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrassi, G.; Polverino De Laureto, P.; Bruschi, C.V. Purification and characterization of ferulate and p-coumarate decarboxylase from Bacillus pumilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, M.; Tokashiki, M.; Tokashiki, M.; Uechi, K.; Ito, S.; Taira, T. Characterization and induction of phenolic acid decarboxylase from Aspergillus luchuensis. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2018, 126, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Dostal, L.; Rosazza, J.P. Purification and characterization of a ferulic acid decarboxylase from Pseudomonas fluorescens. J. Bacteriol. 1994, 176, 5912–5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-K.; Tokashiki, M.; Maeno, S.; Onaga, S.; Taira, T.; Ito, S. Purification and properties of phenolic acid decarboxylase from Candida guilliermondii. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 39, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqueiro-Peña, I.; Rodríguez-Serrano, G.; González-Zamora, E.; Augur, C.; Loera, O.; Saucedo-Castañeda, G. Biotransformation of ferulic acid to 4-vinylguaiacol by a wild and a diploid strain of Aspergillus niger. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 4721–4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.-G.; Dai, C.-C. Degradation of a model pollutant ferulic acid by the endophytic fungus Phomopsis liquidambari. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 179, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girawale, S.D.; Meena, S.N.; Nandre, V.S.; Waghmode, S.B.; Kodam, K.M. Biosynthesis of Vanillic Acid by Ochrobactrum Anthropi and Its Applications. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2022, 72, 117000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado, J.M.; Max, B.; Rodríguez-Solana, R.; Domínguez, J.M. Purification of ferulic acid solubilized from agroindustrial wastes and further conversion into 4-vinyl guaiacol by Streptomyces setonii using solid state fermentation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 39, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Carvalho, S.P.; Zaiter, M.A.; Dantas, K.S.; Pereira, É.J.; da Silva, R.R.; Boscolo, M.; da Silva, R.; dos Santos, M.B.C.; Gomes, E. Bioconversion of Ferulic Acid to 4-Vinylguaiacol by Ferulic Acid Decarboxylase from Brucella intermedia TG 3.48. Processes 2025, 13, 3367. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13103367

de Carvalho SP, Zaiter MA, Dantas KS, Pereira ÉJ, da Silva RR, Boscolo M, da Silva R, dos Santos MBC, Gomes E. Bioconversion of Ferulic Acid to 4-Vinylguaiacol by Ferulic Acid Decarboxylase from Brucella intermedia TG 3.48. Processes. 2025; 13(10):3367. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13103367

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Carvalho, Sylvia Patricia, Mohammed Anas Zaiter, Karine Sousa Dantas, Érike Jhonnathan Pereira, Ronivaldo Rodrigues da Silva, Maurício Boscolo, Roberto da Silva, Maitê Bernardo Correia dos Santos, and Eleni Gomes. 2025. "Bioconversion of Ferulic Acid to 4-Vinylguaiacol by Ferulic Acid Decarboxylase from Brucella intermedia TG 3.48" Processes 13, no. 10: 3367. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13103367

APA Stylede Carvalho, S. P., Zaiter, M. A., Dantas, K. S., Pereira, É. J., da Silva, R. R., Boscolo, M., da Silva, R., dos Santos, M. B. C., & Gomes, E. (2025). Bioconversion of Ferulic Acid to 4-Vinylguaiacol by Ferulic Acid Decarboxylase from Brucella intermedia TG 3.48. Processes, 13(10), 3367. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13103367