Abstract

The increasing quantity and complexity of code in vehicles have imposed a heavy burden on traditional integration testing methods. However, applying new testing methods, such as eliminating redundant test cases, prioritizing based on risk, and optimizing test matching, requires the testing team to possess sufficient information, which entails communication and time costs. In this study, an information management framework is developed for the integration testing phase of automotive software to assess the importance and acquisition difficulty of specific information. The framework mainly includes three core parts: (1) classifying 37 types of test-related information into five hierarchical levels (requirement level, architecture level, function level, component level, and source code level) based on risk theory; (2) designing a scale to evaluate the difficulty of information usage from three dimensions (acquisition, transmission, and evaluation); (3) providing an operational guide for integration testing departments to match information with testing strategies. This framework assists enterprises in making wiser decisions regarding testing methods and provides guidance for future collaboration between original equipment manufacturers and suppliers.

1. Introduction

Modern vehicles have transitioned from traditional mechanical devices to highly intelligent computer systems, with software codebases exceeding one hundred million lines [1]. However, the increasing number of software components and the growing complexity of software architecture pose significant challenges to the integration testing of vehicles [2]. The presence of numerous software defects not only leads to a substantial increase in development costs but also delays the introduction of new products to the market [3]. Furthermore, even after incurring these costs, it remains difficult to avoid software errors once the product is launched [4]. These errors can result in vehicle malfunctions, unstable performance, and even pose serious safety risks to drivers [5]. Therefore, improving the efficiency and accuracy of integration testing is crucial for original equipment manufacturers (OEMs).

To address these challenges, OEMs have had to adopt new testing methods and strategies to predict, detect, locate, and resolve errors more rapidly. Extensive research has been conducted in academia on novel testing methods and strategies, such as automated testing, model-driven testing, and coverage-based testing [6,7,8,9]. However, these methods often encounter difficulties and challenges in practical application [10]. One major reason is that these methods rely on having access to relevant information, which is often lacking in the integration testing department or requires significant effort to use, such as information acquisition, transmission and evaluation [11].

Testing methods can be classified into black-box testing, gray-box testing, and white-box testing based on the comprehensiveness of the information they require. Black-box testing requires the least amount of information and often only involves understanding the software’s requirements or functional design. This makes it efficient for detecting obvious errors but limits its ability to uncover more subtle issues [12]. White-box testing, on the other hand, requires the most information, including access to the source code. This makes it less efficient but capable of uncovering deeper, hidden defects [13]. Gray-box testing attempts to strike a balance between the advantages and disadvantages of both approaches. For example, a coupling between a simulation model running on a hardware-in-loop device enables gray-box testing although no data or measurements were available from the OEM [14]. It does not delve into the binary details of specific source code but instead investigates the software’s architecture through various interfaces, specifications, and documentation, aiming for a balance between efficiency and accuracy.

In traditional automotive development, white-box testing is often applied during the unit testing phase, while black-box testing is typically used during the integration testing phase [15]. However, as OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers) increase their understanding of software and the interactions between software components grow, a significant amount of gray-box testing and even some white-box testing are being applied during the integration testing stage [16]. This means that OEMs now need to acquire more information about the software, which may involve cross-departmental communication within the organization and communication with external suppliers [17].

Hence, this research aims to construct an information management framework to assist the integration testing department in better selecting and applying new testing methods. The core idea of this framework is to organize and classify the information required for various testing methods and evaluate the difficulty of using this information. Through this framework, the integration testing department can gain a better understanding of the resources, skills, and time costs associated with different testing methods, enabling them to make targeted decisions based on their specific circumstances. The specific scope of the research is defined as follows:

- Content boundary: The framework focuses on “information classification and evaluation” for advanced testing strategies, rather than developing specific testing tools or information security technologies.

- Scenario boundary: We provide a universal framework for general automotive software but do not customize it for specific software modules or vehicle types—adaptation to these specific scenarios requires combining enterprise-specific data.

- No application verification: Without unified baseline data, presenting isolated test results would be misleading; instead, we provide an operational guide to enable OEMs to verify effectiveness using their own data in subsequent applications.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the research methodology. Section 3 presents and explains our research results. Section 4 provides an operation guide to use this framework for the integration testing department of OEM. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Methodology

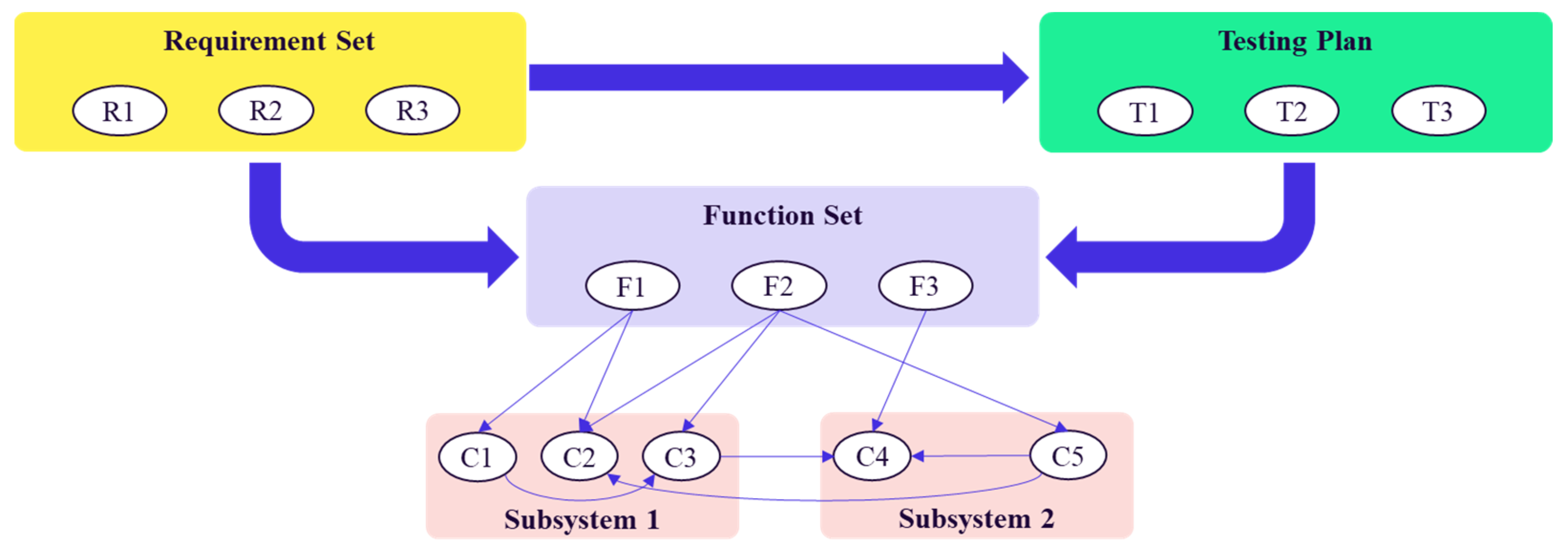

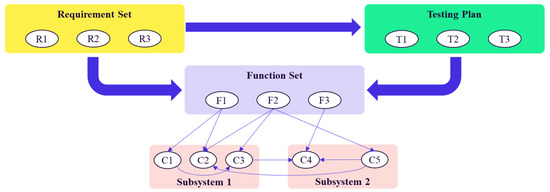

This study employed a two-stage investigation to conduct exploratory research. Prior to the investigation, it was necessary to have a comprehensive understanding of the elements and concepts involved in automotive software integration testing. Figure 1 delineates the hierarchical structure and interdependent relationships among five core elements of automotive software integration testing: Requirement Set, Testing Plan, Function Set, Subsystems, and Components—providing a clear mapping of how testing activities connect to software development fundamentals. Specifically:

Figure 1.

Elements and concepts involved in automotive software integration testing.

- Requirement Set serves as the origin: the requirements analysis department first defines user and product requirements (e.g., functional safety, performance boundaries) and translates these into actionable specifications.

- Testing Plan is derived directly from the Requirement Set [18]. Each test case is designed to verify whether a specific requirement is fulfilled, with priorities assigned based on requirements’ criticality (e.g., safety-related requirements take precedence) [19].

- Function Set is a series of capabilities developed by developers according to requirements documents. A complete function set should be able to meet all the requirements in the requirement set.

- Subsystems & Components: Each function in the Function Set relies on multiple software components distributed across Subsystem 1 and Subsystem 2. For instance, F1 may depend on C1 and C2 from Subsystem 1, while F2 may share C2 with F1 and additionally utilize C3 from Subsystem 2.

During the integration testing phase, a series of test cases are employed to test each function. The emphasis of integration testing for software systems differs from that of unit testing for software components. Unit testing aims to ensure that software components run properly in isolation and focuses on programming defects within the components [20]. On the other hand, integration testing aims to ensure the coordinated operation of software components and subsystems after their interaction, with an emphasis on faults resulting from software interaction [21].

One of the greatest challenges in integration testing lies in the difficulty of identifying the cause of a failed test case, as it may be attributed to a related software component or even other associated functions [22]. Often, a step-by-step examination of each component and its interaction is required, resulting in significant time and financial costs [23]. Therefore, to expedite the identification of the causes of faults, some industry-recognized testing strategies involve conducting preliminary risk assessments on software functions or components before any failures occur [24]. For example, Kugler et al. [25] optimized the test method by evaluating the possibility and loss of failure of functions or components, and reported a 10–40% reduction in test workload in case studies.

2.1. Stage 1: Investigation on Testing Strategies and Required Information

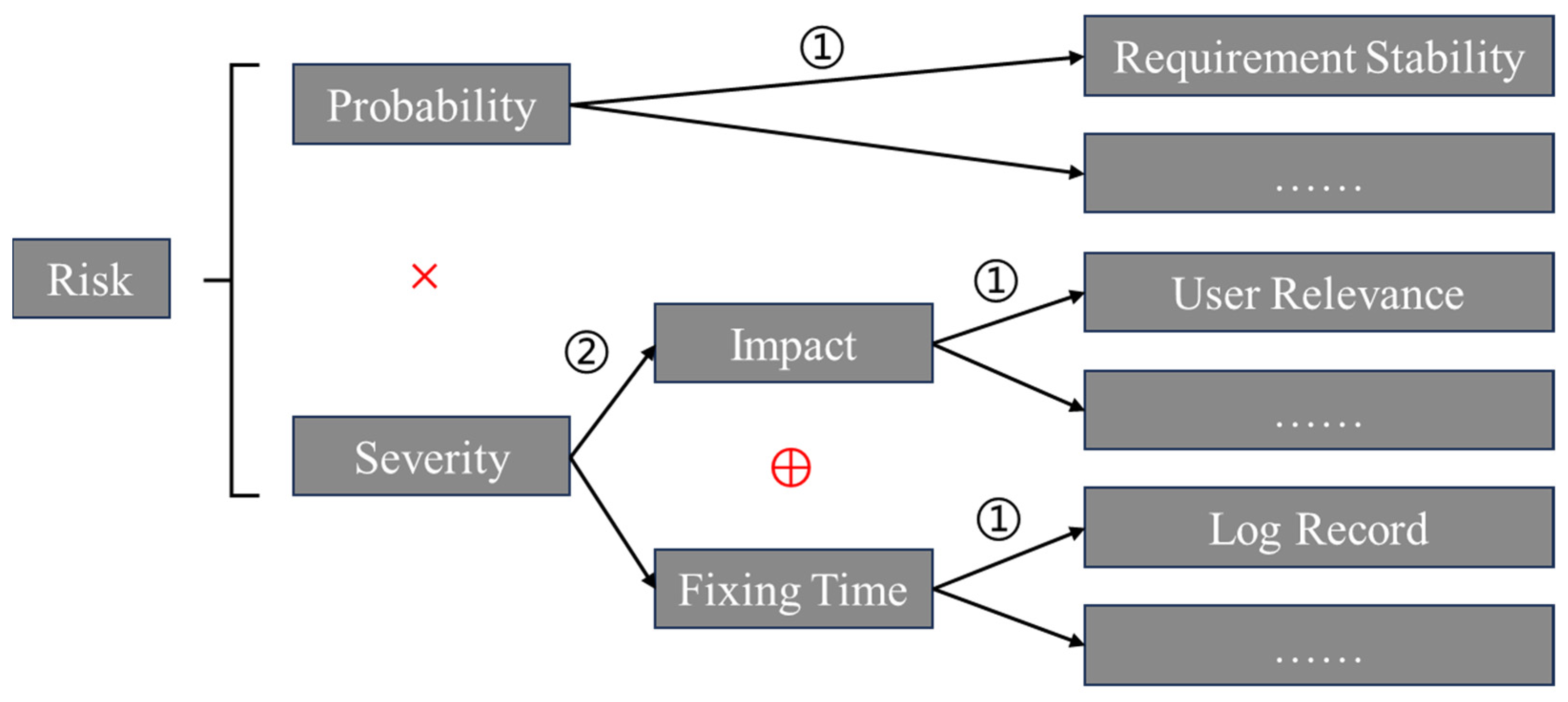

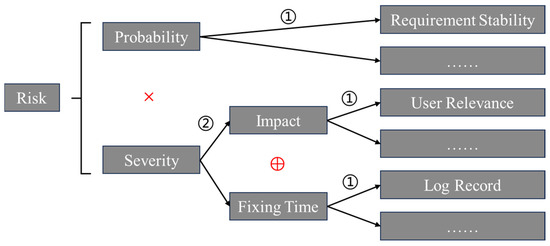

In order to implement the aforementioned testing strategies, it is necessary to rely on certain information. The objective of the first stage of the investigation is to understand the current advanced testing strategies and the required information through a literature review. This information is then organized through structured classification. To conduct a more accurate and scientifically based investigation, this study employs risk theory to define the keywords for literature retrieval; the specific illustration of this definition method is presented in Formula (1), which has been adapted from References [26,27].

refers to the expected loss when an undesired event occurs. indicates the likelihood of the event happening. refers to the loss when the event occurs. For automotive software, is related to its and , where the former pertains to the product and users, and the latter pertains to the development team of the enterprise [28]. The symbol indicates that can be evaluated through some form of positive coupling relationship with the and . For this positive coupling relationship, different studies have applied different calculation methods, which need to be comprehensively considered by the engineering team in combination with the project situation. For example, different projects have different preferences for the definition of . Some projects need to catch up with the deadline, so is more important. And some projects are strongly related to safety, so the is more worthy of attention. In addition, different teams have different types of information, so the calculation methods of their severity and are definitely different. This research is more about making a macro-level summary of information related to , and , so as to establish a thinking framework of management information. As for how to deduce the value of from the information, we don’t provide a specific calculation method. The primary focus of the first stage literature investigation is to determine which information can be used for predicting and analyzing the risks of software functions or components, as well as understanding their underlying mechanisms.

Furthermore, this information will be allocated to different levels of information hierarchy, including the requirement level, architecture level, function level, component level, and source code level. Information from different levels needs to be obtained from various sources, including the internal requirements analysis department, architecture design department, software development department, supplier management department of the OEM, as well as external suppliers [17].

2.2. Stage 2: Evaluation of Information Usage Difficulty

The focus of this study is on the integration testing phase of automotive software, with a perspective from the integration testing department. Through the first stage of the investigation, valuable information has been gathered, but the difficulty of using different types of information varies for the integration testing department. On one hand, interactions that involve cross-departmental or cross-company collaboration often require more time and incur higher costs [29]. If the benefits of using certain information are minimal compared to the associated costs, it may not be necessary to obtain that information. On the other hand, some information in the real world may be difficult to quantify and evaluate accurately, so that engineers can only get one-sided, partial and vague information, and the importance of this information will be greatly reduced.

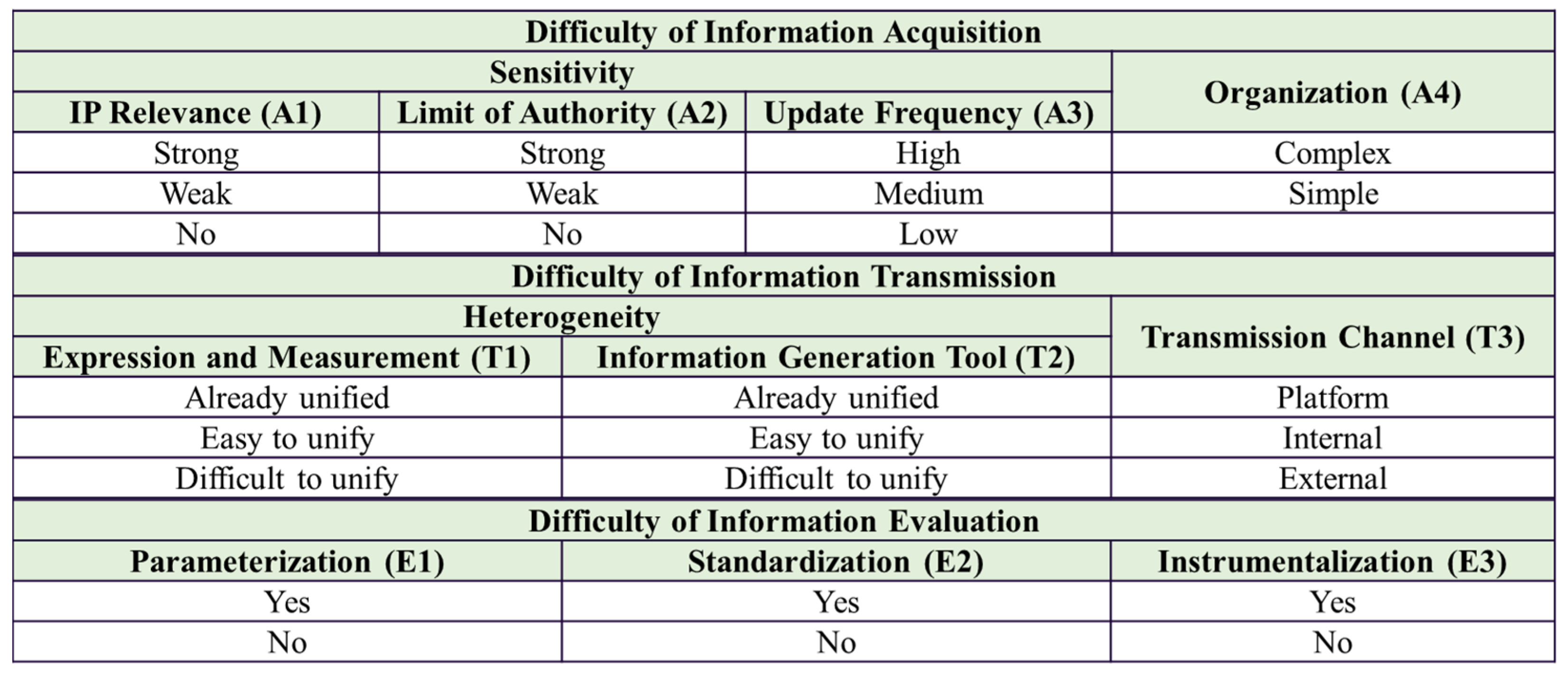

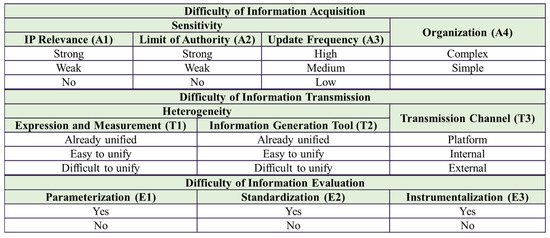

To assist the integration testing department in managing this information, a scale was designed in the second stage of the investigation to assess the difficulty of information acquisition, transmission, and evaluation, as illustrated in Figure 2. Experts were asked to rate the difficulty of using the information.

Figure 2.

Scale of the difficulty in using information.

The difficulty of information acquisition is primarily influenced by sensitivity and organization [30]. Sensitivity refers to factors that may decrease the willingness of information sources to provide information, such as information directly related to a company’s intellectual property or information subject to authorization restrictions due to confidentiality [31]. Sensitivity is also influenced by the frequency of information updates. If the update frequency is high, information sources may be less willing to provide information to reduce frequent communication. Organization refers to the organizational chain or other structure involved in obtaining information. To acquire certain information, the integration testing department may need to go through architectural design departments, supplier management departments, and multiple external suppliers, which significantly increases the difficulty of information acquisition [29].

The difficulty of information transmission is primarily influenced by heterogeneity and transmission channels [32]. Heterogeneity first considers whether there is a unified language and measurement units for expressing this type of information. It then considers whether there are standardized formatting tools within the company or the industry for generating this type of information, similar to the use of Word for text files and Excel for table files in office environments [33]. Transmission channels mainly consider how information is exchanged between different departments or companies. Internal information exchange within a company is generally simpler compared to external information exchange. Furthermore, internal departments may have established information-sharing platforms for certain types of information, which further reduces the difficulty of information transmission [34].

The difficulty of information evaluation is primarily influenced by parameterization, standardization, and instrumentalization. Parameterization refers to whether there are clear and explicit measurement methods for quantifying the information. Vague qualitative judgments undoubtedly reduce the reliability of the information [35]. Standardization considers whether industry-specific evaluation standards have been established, such as ISO 26262 for functional safety in the automotive industry [36]. Instrumentalization considers whether there are automated tools currently available to facilitate more efficient information evaluation.

To create a scale that can be widely applicable to various projects, the value ranges for the 10 indicators were only divided into simple categories, such as high/medium/low and yes/no. Taking IP Relevance as an example, “Strong” means that the information involves core IP, “Weak” means that the information involves general IP, and “No” means that the information does not involve IP. As for the difficulty of information evaluation, because there is no clear definition standard for parameterization, standardization and instrumentalization in the industry, this study only makes a distinction between yes and no. Notably, the “Organization (A4)” in the acquisition difficulty dimension is not universally required: it is only used when the acquisition difficulty is medium or high (e.g., information with high IP sensitivity or frequent updates requires multi-department coordination), while for low-difficulty information (e.g., static public standards), A4 can be omitted to simplify the assessment process. In practical applications, different companies and projects can further refine the value ranges based on their specific circumstances.

The expert investigation consisted of 1 integration testing department head from an OEM, 2 integration testing engineers, 1 supplier representative, and 1 researcher specializing in automotive industry standards. The experts were asked to evaluate the difficulty of information acquisition, transmission, and evaluation based on the information obtained in the first stage of the investigation. The final results were compiled and determined through discussions among the experts. The diverse professional backgrounds and experiences of the experts contribute to the comprehensiveness and reliability of the results [37].

3. Investigation Results

3.1. Testing Strategies and Required Information

After a thorough literature review, this study has identified four effective testing strategies for improving efficiency. These strategies include eliminating low-risk high-level tests, adjusting the test plan based on function risks, troubleshooting based on component risks, and eliminating redundant test cases. The first three testing strategies fall within the scope of risk theory, while the fourth strategy will be discussed separately. From the relevant literature on the first three testing strategies, 35 types of information have been identified that can be used for predicting and analyzing software risks. Table 1 illustrates the impact of each type of information on specific factors in risk theory and indicates the hierarchical level to which the information belongs.

3.1.1. Eliminating Low-Risk High-Level Tests

The integration testing of automotive software function can be further subdivided into three levels: system-level, vehicle-level, and user acceptance level [38]. The system-level focuses primarily on the collaboration among components within the system. Vehicle-level testing primarily emphasizes the collaboration of multiple systems. User acceptance level testing mainly focuses on the user impact generated by the software in the real physical world when it operates without any issues.

Hodel et al. [39] have analyzed a large number of actual test cases and found that when certain parameters of the software meet certain conditions, testing at a specific level becomes necessary, while otherwise, the probability of errors is very low. For example, the file management function is an internal component of software, which will not be affected by the external environment and drivers, so it does not need to be tested at the vehicle level and user acceptance level, and system-level testing is enough to show that it is safe and reliable. By eliminating low-risk high-level tests for different parameter combinations of software functions, time and costs can be effectively reduced. From such testing strategies, eight types of information can be identified:

- Functional Safety is directly related to vehicle safety during operation, and the repair of related issues is more challenging. Its definition and assessment method can refer to ISO 26262 [36].

- Subsystem Complexity describes the number of components and interactions between components within the subsystem. Its quantitative evaluations often use graph theory in mathematics. It is widely agreed in the industry that the more complex a subsystem is, the more likely it is to encounter errors [40].

- Driver/Environment Influence considers whether the software function is affected by environmental or driver factors when performing tasks. Since environmental or driver factors are often uncontrollable, problems may arise during development due to the inability to cover all possible scenarios [39].

- Fault Detection describes whether the software function is designed with runtime fault detection mechanisms. In some cases, fault detection mechanisms can replace certain test cases [41].

- User Relevance, Legal Relevance and Insurance Relevance are used to describe whether the software function is mentioned in user experience design, Legal restrictions, or insurance terms. If relevant, it implies that the software function requires specific dedicated test cases [42].

- Drivability Impact describes whether the software function has a direct impact on drivability. As drivability involves multiple complex evaluation dimensions, including safety, comfort, power, operability, etc., the test cases for the related software function also need to be specifically designed [43].

3.1.2. Adjusting the Test Plan Based on Function Risks

There have been numerous studies that utilize risk theory to assess risks at the software function level based on certain information. The assessment serves two main purposes. Firstly, it prioritizes software functions for testing based on their assessed risk values, ensuring that high-risk functions are tested first to detect as many defects as possible at an early stage [11]. Secondly, it adjusts the threshold for passing tests based on the risk assessment values, with higher risks requiring stricter thresholds for test acceptance [25]. Long-tail testing incurs the highest costs and time investment. Kugler argues that when the risk associated with a software function meets certain conditions, it is unnecessary to execute all the long-tail tests, thus shortening the length of the tail [25]. From such testing strategies, 17 types of information can be identified:

- Requirement Stability primarily considers whether the requirements description of a software function has remained largely unchanged over a long period. The more stable the requirements, the higher the probability of reusing relevant software, leading to a lower probability of errors [25].

- Requirement Complexity can be described by the target parameters defined in requirements and the number of interaction logics. Generally, the more complex the requirements, the more challenging it is to develop the software, resulting in a higher probability of errors [25].

- Maturity primarily considers whether the components utilized in a software function are newly developed or reused. The probability of errors is lower in previously validated mature software [25].

- Number of Variants considers the number of branches in the components used by a software function. Variants often pose potential sources of errors in software development and management [44].

- Redundancy considers whether a software function is designed with redundant backup mechanisms. Functions with good redundancy often have a smaller impact even when issues occur [45].

- Commonality considers whether the components used by a software function are also used by other functions. If a function shares many components with others, errors can propagate to other functions, resulting in more severe consequences [46].

- Encryption considers whether the components used by a software function involve strict encryption. Information security issues can have broader impacts, such as privacy breaches [47].

- Log Record and Structured Decomposition respectively consider whether a software function is designed with logging mechanisms and structured testable units. Comprehensive and detailed logging, as well as structured software architecture, aid developers in quickly identifying and fixing defects [48,49].

- Usage considers the frequency of a software function’s usage or execution. The higher the usage frequency, the greater the probability of errors and the more pronounced the impact [25].

- Deployment to Multi-Environments considers the number of platforms that a software function needs to adapt to. Developing highly universal software for embedded systems, such as in vehicles, is challenging. This implies that the more environments a software function needs to accommodate, the higher the probability of failure and impact [25].

- Part of V2X considers whether a software function uses V2X components. The use of V2X components increases the avenues for error occurrence and propagation [47]. For example, the “V2I (vehicle-to-infrastructure) traffic light information reception function” relies on V2X components to interact with road-side units; if the V2X component fails to receive traffic light signals, the function will be disabled, and the failure may also propagate to the “adaptive cruise based on traffic lights” function.

- Performance includes metrics such as real-time capability, precision, and accuracy. High-performance requirements not only demand a high level of proficiency from developers but also mean that even minor errors can have significant consequences [25]. For example, the “adaptive cruise control function” requires a real-time response to the front vehicle’s speed changes (latency ≤ 100 ms) and speed control precision (error ≤ 1 km/h); even a 200 ms latency may cause rear-end collisions.

- Dependency considers how many other software functions a software function relies on for its operation. Higher dependency implies a need for coordination among more software functions during development and operation, which is related to the probability of errors and the fixing time [50].

- Code Complexity includes metrics such as the number of statements, code line length, number of loop paths, depth of function nesting, recursion depth, number of function calls, parameter count, and comment density. Bryan et al. proposed a gray-box testing algorithm and process that utilizes non-intrusive code analysis tools to detect interaction patterns between functions, thus predicting the probability of errors and the difficulty of fixes [51].

- Requirement Density how many user requirements are associated with a software function. More associated requirements lead to more complex software design and larger error impacts [25].

- Interactivity considers the scale of signals for the input and output of a software function. Muscedere et al., through modeling and case studies, found a clear positive correlation between interactivity and the probability of errors. The scale of signals also reflects the scope and complexity of data propagation, which is similarly associated with impact and fixing time [52].

3.1.3. Troubleshooting Based on Component Risks

Based on function risks, it is possible to further assess the risks associated with software components. In integration testing, a major challenge is identifying which component or components are responsible when an error occurs in the execution of a software function [22]. Conducting a preliminary assessment of component risks can help engineers quickly identify the cause of the problem [53]. From such testing strategies, the following 10 types of information can be identified:

- Interface Complexity considers the difficulty of external interactions with software components. The more complex the interface, the more likely it is to encounter issues when accessing the component externally [54].

- Multidisciplinary Relevance considers the number of disciplines involved in the development of software components. As automobiles are complex products with high levels of mechanical, electrical, and hydraulic coupling, the development of certain software components may require modeling methods from different fields. The probability of errors in such models is relatively high [55].

- Team Capability and Team Complexity consider the background of the component development team, which can be quantitatively described using the Capability Maturity Model Integration. It is generally believed that software quality is higher when developed by more professional teams [56].

- Open Source Code Proportion and Automatically Generated Code Proportion consider the composition of the source code of software components. Due to the risks associated with open source code and automatically generated code that has not undergone rigorous review in practical projects, there may be some unknown errors [57,58].

- Coupling with Hardware considers whether modifications to a software component require knowledge of the hardware. If there is a strong coupling between the component and the hardware, debugging will be complex, and defect fixes will be slow [59].

- Developer Familiarity primarily considers whether the developer responsible for fixing a software component is sufficiently familiar with the code. The more familiar the developer is with the code, the higher the efficiency of fixes. If the software components are not developed in-house, then the developers of OEM will naturally not be familiar with the specific code. Moreover, if the lifecycle of a software component is long, the developer’s familiarity may decrease over time [60].

- Code Readability primarily considers the structure of the source code of software components and the understandability of text comments. The easier it is to read, the easier it is to modify [61].

- Connection Coupling considers the degree of mutual influence between software components through their connections. For uncoupling connection, a change in one component does not affect another component. For a weak coupling connection, a change in one component unidirectionally affects another component. For a strong coupling connection, any change in one component affects another component. Clearly, stronger connection coupling not only leads to error propagation but also increases the effort required for fixes [62].

Table 1.

Overview of information types and risk mechanism.

Table 1.

Overview of information types and risk mechanism.

| Testing Strategy | Factor | Level | Probability | Impact | Fixing Time | Basis/Source Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Level Test Elimination | Functional Safety | Function Level | ✓ | ✓ | ISO 26262 [36] | |

| Subsystem Complexity | Architecture Level | ✓ | Graph theory application in software [40] | |||

| Driver/Environment Influence | Function Level | ✓ | Hodel et al. [39] | |||

| Fault Detection | Function Level | ✓ | Theissler [41] | |||

| User Relevance | Function Level | ✓ | Fabian et al. [42] | |||

| Legal Relevance | Function Level | ✓ | Fabian et al. [42] | |||

| Insurance Relevance | Function Level | ✓ | Fabian et al. [42] | |||

| Drivability Impact | Function Level | ✓ | Schmidt et al. [43] | |||

| Function Risk Assessment | Requirement Stability | Requirement Level | ✓ | Kugler et al. [25] | ||

| Requirement Complexity | Requirement Level | ✓ | Kugler et al. [25] | |||

| Maturity | Component Level | ✓ | Kugler et al. [25] | |||

| Number of Variants | Component Level | ✓ | Antinyan et al. [44] | |||

| Redundancy | Function Level | ✓ | Alcaide et al. [45] | |||

| Commonality | Component Level | ✓ | Vogelsang et al. [46] | |||

| Encryption | Component Level | ✓ | Luo et al. [47] | |||

| Log Record | Function Level | ✓ | Ardimento and Dinapoli [48], Du et al. [49] | |||

| Structured Decomposition | Function Level | ✓ | Ardimento and Dinapoli [48], Du et al. [49] | |||

| Usage | Architecture Level | ✓ | ✓ | Kugler et al. [25] | ||

| Deployment to Multi-Environments | Architecture Level | ✓ | ✓ | Kugler et al. [25] | ||

| Part of V2X | Component Level | ✓ | ✓ | Luo et al. [47] | ||

| Performance | Component Level | ✓ | ✓ | Kugler et al. [25] | ||

| Dependency | Function Level | ✓ | ✓ | Vogelsang et al. [50] | ||

| Code Complexity | Source Code Level | ✓ | ✓ | Muscedere et al. [51] | ||

| Requirement Density | Function Level | ✓ | Kugler et al. [25] | |||

| Interactivity | Function Level | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Muscedere [52] | |

| Risk-Based Troubleshooting | Interface Complexity | Component Level | ✓ | Durisic et al. [54] | ||

| Multidisciplinary Relevance | Component Level | ✓ | Ryberg [55] | |||

| Team Capability | Component Level | ✓ | Sholiq et al. (CMMI) [56] | |||

| Team Complexity | Component Level | ✓ | Sholiq et al. (CMMI) [56] | |||

| Open Source Code Proportion | Requirement Level | ✓ | Kochanthara et al. [57], Waez and Rambow [58] | |||

| Automatically Generated Code Proportion | Requirement Level | ✓ | Kochanthara et al. [57], Waez and Rambow [58] | |||

| Coupling with Hardware | Component Level | ✓ | Hewett and Kijsanayothin [59] | |||

| Developer Familiarity | Source Code Level | ✓ | Wang et al. [60] | |||

| Code Readability | Source Code Level | ✓ | Scalabrino et al. [61] | |||

| Connection Coupling | Component Level | ✓ | ✓ | Lee and Wang [62] |

3.1.4. Eliminating Redundant Test Cases

In addition to using risk theory to assess the risks of functions and components, we have identified in the literature review a testing strategy that utilizes the relationships between requirement specifications to eliminate redundant test cases. Throughout the entire design and development process, requirements, functions, and test cases are interrelated [18]. The dependencies between requirements often imply dependencies between functions and dependencies between test cases. However, this relationship is not always one-to-one, as a test case may correspond to multiple requirements, and a requirement may be covered by multiple test cases. Arlt et al. inferred the dependencies between test cases by utilizing structured requirement specifications and then used successfully executed or failed test cases to eliminate redundant ones [63]. This testing strategy primarily involves two types of information:

- Requirement Types: Requirements are classified into six categories: vehicle function, sub-function, pre-condition, trigger, function contribution, and end-condition. Vehicle function requirements encompass multiple sub-function requirements, while sub-function requirements include pre-condition, trigger, function contribution, and termination condition. This hierarchical structure implies certain logical dependencies between requirements [63].

- Parent Requirement: The parent–child relationship signifies that a parent requirement only needs to be tested if all its child requirements are satisfied; otherwise, the test cases associated with the parent requirement are considered redundant. For example, if engineers know that a test for detecting rainwater using a rain sensor has failed, it can be inferred that the test for automatically closing the sunroof when it rains is redundant since it is already known to fail. Based on the definition of requirement types, there exists a parent–child relationship chain from vehicle function to sub-function to end-condition to function contribution to trigger to pre-condition [63].

With a clear understanding of such structured requirement specifications, redundant test cases can be automatically detected using algorithms. This means that at any given point during the testing phase, redundant test cases can be inferred automatically from the current status of successful and failed tests [63]. By employing this testing strategy, the integration testing department does not need to have knowledge of the functions and components but rather relies on obtaining structured documentation from the requirement design department to improve testing efficiency. The history of redundant test case detection may depend on the order in which test cases are executed, providing an interesting opportunity to optimize the number of redundancies by altering the sequence of test cases. In other words, in the past, when determining the order of test cases in developing a test plan, the focus has often been on improving test coverage for the requirements. However, in the future, we may also need to consider how to increase the inference rate of redundant test cases. Haidry et al.’s research introduces common methods for adjusting the priority of test cases, such as those based on historical data, knowledge-based methods, and model-based methods [64].

3.2. Difficulty of Using Information

A literature review identified 37 types of information that contribute to advanced testing strategies. For the integration testing department, the ideal scenario would be to have access to all this information and use its specific values to select the most appropriate testing strategies and develop the most efficient testing plans. However, the reality falls short of this ideal because the integration testing department does not have a god’s-eye view, and the utilization of many pieces of information is highly challenging. Table 2 presents the difficulties in information acquisition, transmission and evaluation obtained through expert surveys.

Table 2.

Difficulty of information acquisition, transmission and evaluation.

It should be noted that this study assesses the overall average level of the industry through expert investigation, rather than focusing on a specific company or project. Therefore, the values in Table 2 are suggested as default values for the information management framework. In practical applications, many factors at the enterprise and project levels can influence the difficulty of using information.

At the enterprise level, there are three main factors:

- Technical research and development capability: Information within the company is generally easier to access and more reliable than information from external suppliers. Therefore, OEMs with more in-house software development capabilities have a greater advantage in terms of information availability and efficiency [65]. In industry practice, it is not difficult to observe that new automakers who invest heavily in software development have faster product release and iteration cycles compared to traditional OEMs.

- Supply chain bargaining power: Even when obtaining information from the same supplier, OEMs with stronger supply chain bargaining power tend to acquire more information more quickly [66]. Sometimes, dominant supplier giants may refuse to provide relevant information to smaller-scale OEMs with weaker bargaining power.

- Internal management system: Cross-departmental communication within the enterprise has always been a challenge for OEMs, particularly during periods of industry transformation [67]. The use of certain information may appear to be a simple request and response relationship, but in reality, it may involve the division of power, responsibilities, and interests among departments.

At the project level, there are two main factors:

- Platformization for the project: A high level of platformization for a project indicates that many cross-organizational collaborations around the project have become more stable, and there is a wealth of historical data and mature experience to serve as references. This undoubtedly reduces the information usage difficulty.

- Supplier collaboration models around the project: Current automotive software delivery is no longer a turnkey engineering process for black-box software as it used to be [1]. OEMs and suppliers have adopted various new collaboration models. For example, OEMs and suppliers establish joint ventures to jointly develop core technologies. Alternatively, suppliers may deploy a team to work within the OEM, collaborating with the internal development team. Additionally, suppliers may provide open technology licenses, allowing OEMs direct access to source code. Different collaboration models result in varying levels of difficulty in accessing relevant information.

4. Operating Guide

4.1. Potential Application Fields

This subsection demonstrates how the integration testing department can use the information management framework and highlight important considerations throughout a complete vehicle development process.

After the requirements analysis and function design phases, the integration testing department can obtain structured requirement documents (including Requirement Types, Parent Requirements, and other relevant information) from the relevant departments. Based on this, they can design integration test cases and analyze the dependencies between test cases [63].

During the software development phase, the integration testing department should conduct a comprehensive assessment of the remaining 35 categories of information, considering the specific circumstances of the enterprise and project. They should eliminate information categories that are either unusable or have excessively high usage difficulty. It is important to note that when assessing information usage difficulty, OEMs should consider not only the current project but also future related work. For example, the procurement of toolchains and development platform technologies may be expensive and time-consuming for an individual project, but it can provide long-term benefits.

After the latest version of a software component or function is developed and before it is integrated into the system, the integration testing department should obtain all the necessary information from the internal development team and external suppliers. They should then reasonably assess and classify the risks associated with various software functions and components based on risk theory. Based on the risk assessment results, the integration testing department can match necessary test cases to each software function [39], set reasonable test pass thresholds [25], and adjust the order of test cases based on the combined function risk and redundancy test case inference rate [11].

During the integration testing phase, the integration testing department can infer redundant test cases in real-time based on the current status of successful and failed tests and the implicit logical dependencies in the structured requirement specifications [63]. It is worth noting that, in addition to inference methods based on requirement information, scholars have recently proposed new methods that leverage information such as functional dependencies, component connections, and code complexity to infer redundant test cases [68]. These pieces of information are also considered within our framework. Therefore, besides their utility in risk assessment, they can also be used to identify redundant testing scenarios.

After the integration testing phase, the integration testing department compiles a list of software functions and components that did not pass the tests. They prioritize the investigation of the causes of failures based on risk, focusing limited resources on resolving issues that have the greatest impact and longest fixing time [53]. Furthermore, the identified causes of failures are saved as historical error data, along with the independent variables used to evaluate risk within the framework. This data can be utilized in software defect prediction methods such as causal models, correlation regression models, and software reliability growth models to assist in future unit testing and integration testing [69].

4.2. Application Outlook

The previous discussion has only highlighted the benefits of using this framework, but utilizing this framework itself also incurs costs. When applying this framework, people often need to rely on expert knowledge to manually assess the weights of different information indicators to explicitly determine which information is more important, which can be time-consuming and subject to potential biases. As mentioned in Section 2.1, for different components and different projects, these weights may vary, so the assessment of indicator weights is also a complicated task. This paper looks ahead to the prospect of having a more automated or simpler weight allocation method in the future, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Weight allocation hierarchy of information management framework.

The first-level weight allocation of the whole framework is to synthesize three intermediary indicators: probability, impact and fixing time from information indicators. This level of weight allocation can introduce the entropy weight method to achieve automation. The entropy weight method is a widely used objective weighting technique in multi-criteria decision-making, which is based on the concept of information entropy from information theory [70]. It can measure the degree of disorder or uncertainty in a system. Table 2 provides the value ranges of various information indicators, but in the real world, the values of many projects may be quite similar. If an indicator has the same or similar values for all projects, it means this indicator has little guidance value for risk assessment, and engineers should prioritize those indicators with significant differences. The core idea of the entropy weight method is to assign higher weights to the indicators with greater information entropy. Its main advantage is the simplicity of the calculation process, which can easily achieve data-driven automation. The integration testing department can establish a continuously accumulating database, constantly importing the values of various information indicators from historical projects, and then automatically calculating the weights using a fixed formula. This allows for a more systematic and objective weight allocation process, reducing the reliance on manual expert assessments.

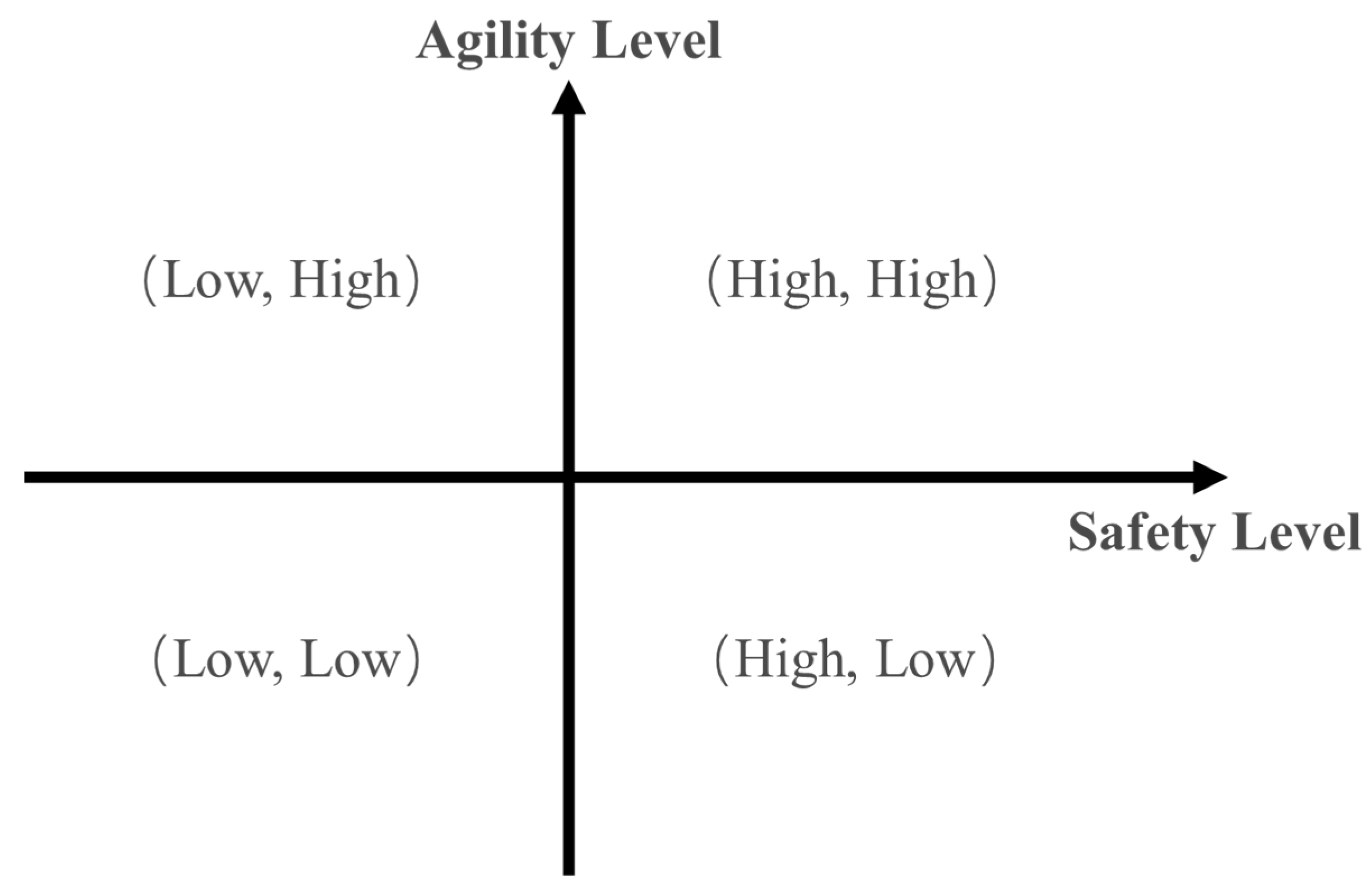

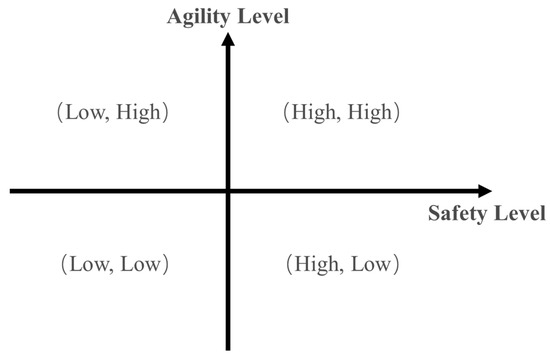

The second level of weight allocation is to synthesize the impact and fixing time into severity. In risk theory, the two main indicators considered are probability and severity, and severity is positively correlated with impact and fixing time [26]. The probability of error is a universal indicator, but as mentioned in Section 2.1, different projects or components have different preferences for defining severity. Some may emphasize safety-related impacts, while others may emphasize fixing time related to agile development. This level of weight allocation process can adopt a classification management approach to standardize it. As shown in Figure 4, the integration testing department can define project safety levels based on functional safety and information security, and project agility levels based on user usage frequency and operational continuity difficulty [71]. This can at least divide the two dimensions into four quadrants, with each quadrant assigned a fixed weight. Of course, the specific number of quadrants and the weights within each quadrant can be defined by the enterprise itself. By classifying projects based on safety and agility characteristics, the second-level weight allocation can be streamlined and standardized. This helps ensure consistent and objective risk assessment, especially for organizations with diverse project portfolios. The fixed weight allocation within each quadrant also makes the process more efficient and scalable.

Figure 4.

Risk classification management of automotive software projects.

It is important to note that the two-level weight allocation aims to emphasize the relative importance of each indicator, thereby helping managers to coordinate more efficiently across the organization. This does not mean that the actual risk value calculation is simply the weighted sum of the values at each level. The specific method of calculating the actual risk value still depends on the testing strategy adopted by the engineers. In the future, with the use of AI agents and similar tools in integration, the system can automatically invoke information interfaces from different departments or even different suppliers based on the weights and testing strategies, and then conduct risk assessments, thereby executing the work required for integration testing more efficiently [72,73].

5. Conclusions

Facing the increasing complexity of automotive software, efficient testing strategies for automotive integration are urgently needed to be implemented within OEMs. This study helps the industry recognize the gap between advanced testing strategies in terms of technical advancements and their practical implementation. It also provides a flexible and practical technical management tool for the integration testing departments of OEMs.

Firstly, this study conducts a comprehensive investigation and analysis of efficient integration testing strategies and the required information, enabling companies to gain a deeper understanding of the value of information. Since the potential value of different types of information varies, some may play a crucial role in improving testing efficiency, while others may be optional. Therefore, further exploration is needed to assess the importance of various types of information, helping companies strike a balance between the benefits and costs of using information.

Secondly, based on risk theory, this study summarizes the mechanisms through which various types of information improve integration testing efficiency from the dimensions of probability, impact, and fixing time. It also associates different types of information with their corresponding development levels and sources. This structured classification facilitates integration testing departments in clarifying the purpose and sources of information, serving overall integration management, and ensuring the adjustability of the information management framework. This framework is not to collect information within a limited scope, but to be open to new testing strategies and new information. Even if new integration testing strategies emerge in the future, the required types of information can be incorporated into this framework. We also anticipate that this tool will soon truly assist OEMs in reducing testing costs, shortening time to market, improving product quality, and enhancing customer satisfaction.

Lastly, this study proposes analysis dimensions and indicators for the difficulties related to information acquisition, transmission, and evaluation. It designs a dedicated scale aimed at inspiring the automotive industry to accelerate consensus formation, organizational transformation, and digitalization. We recommend that key participants in the automotive industry jointly establish standardized interfaces and toolchains for information generation, storage, transmission, and analysis. We also suggest that OEMs and suppliers explore deeper and more comprehensive collaboration models and establish information-sharing mechanisms to facilitate the circulation of information that contributes to product development iterations. Furthermore, we recommend that OEMs drive internal integration of technology and information, constructing development infrastructure and platforms for software-defined vehicles.

While this study provides an actionable information management framework, it also has inherent limitations and potential risks:

- In terms of research methods, although the expert survey participants in the second stage cover multiple roles, the small sample size may limit the universality of the default difficulty values in Table 2. In addition, the information difficulty evaluation focuses on the industry average, regardless of the differences between enterprise types or project scales.

- In terms of framework implementation, the weight distribution of the framework depends on the accumulation of historical project data. OEMs with limited data reserves may face difficulties in implementation, leading to over-reliance on human expert judgment and potential subjectivity. In addition, the framework assumes that information sharing across departments and organizations is technically feasible, but it does not fully consider the non-technical obstacles that may hinder information flow.

- In terms of information security, the framework encourages obtaining detailed supplier information. If there is no strict data security protocol, this may lead to the disclosure of the supplier’s core technology or the OEM’s internal testing strategy, which may lead to legal disputes or competitive disadvantages.

Future work can focus on three areas: (1) expanding the expert sample size to include small and medium-sized OEMs, tier-1 suppliers, and cross-regional participants, to refine the information difficulty assessment and improve generalizability; (2) developing a simplified version of the framework for data-scarce OEMs, including pre-set weight templates for common project types; (3) collaborating with industry alliances to establish standardized information security protocols that balance information availability and IP protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z. and L.R.; methodology, W.Z. and M.S.; validation, W.Z., M.S., X.L. and L.R.; formal analysis, W.Z. and M.S.; investigation, W.Z. and M.S.; resources, W.Z., M.S., X.L. and L.R.; data curation, W.Z. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.S.; visualization, W.Z. and M.S.; supervision, X.L. and L.R.; project administration, X.L. and L.R.; funding acquisition, X.L. and L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Project for Cooperation between Chinese Academy of Engineering and Local Governments, grant number Z025-AHYJY-01, and grant number 2024-03.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated or used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The first author would like to acknowledge the support received at CARIAD, Volkswagen Group China. The company provided practical industry guidance, which was crucial for the completion of this research. Special thanks go to Hao Wu, Vadym Finn Cemmasson and Dariusch Deermann for their valuable advice and support.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Wang Zhang, Xinglong Liu, and Linjie Ren were employed by the Anhui Emerging Intelligent Connected New Energy Vehicle Innovation Center. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, F. Impact, challenges and prospect of software-defined vehicles. Automot. Innov. 2022, 5, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Azimi, S.; Moramarco, A.; Sabena, D.; Parisi, F.; Sterpone, L. An automated continuous integration multitest platform for automotive systems. IEEE Syst. J. 2021, 16, 2495–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Ryu, D.; Baik, J. Predicting just-in-time software defects to reduce post-release quality costs in the maritime industry. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2021, 51, 748–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Staron, M.; Berger, C.; Hansson, J.; Nilsson, M. Analysing defect inflow distribution of automotive software projects. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Predictive Models in Software Engineering, Turin, Italy, 17 September 2014; pp. 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Matloob, F.; Ghazal, T.M.; Taleb, N.; Aftab, S.; Ahmad, M.; Khan, M.A.; Abbas, S.; Soomro, T.R. Software defect prediction using ensemble learning: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 98754–98771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, A.; Timo, O.N.; Ramesh, S. Model-based testing of automotive software: Some challenges and solutions. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Design Automation Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 7–11 June 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kriebel, S.; Markthaler, M.; Salman, K.S.; Greifenberg, T.; Hillemacher, S.; Rumpe, B.; Schulze, C.; Wortmann, A.; Orth, P.; Richenhagen, J. Improving model-based testing in automotive software engineering. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering in Practice, Gothenburg, Sweden, 27 May–3 June 2018; pp. 172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Lita, A.I.; Visan, D.A.; Ionescu, L.M.; Mazare, A.G. Automated testing system for cable assemblies used in automotive industry. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 24th International Symposium for Design and Technology in Electronic Packaging (SIITME), Brasov, Romania, 22–25 October 2018; pp. 276–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, D.; Baek, J.; Kim, M. MAESTRO: Automated test generation framework for high test coverage and reduced human effort in automotive industry. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2020, 123, 106221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobaj, J.; Macher, G.; Ekert, D.; Riel, A.; Messnarz, R. Towards a security-driven automotive development lifecycle. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2023, 35, e2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadwal, A.; Washizaki, H.; Fukazawa, Y.; Iida, T.; Mizoguchi, M.; Yoshimura, K. Prioritization in Automotive Software Testing: Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Quantitative Approaches to Software Qualityco-Located with 25th Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference (APSEC 2018), QuASoQ, Nara, Japan, 4–7 December 2018; pp. 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Utesch, F.; Brandies, A.; Pekezou Fouopi, P.; Schießl, C. Towards behaviour based testing to understand the black box of autonomous cars. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2020, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.; Quante, J.; Woehrle, M. Experience report: White box test case generation for automotive embedded software. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Ninth International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation Workshops (ICSTW), Chicago, IL, USA, 11–15 April 2016; pp. 269–274. [Google Scholar]

- Konzept, A.; Reick, B.; Pintaric, I.; Osorio, C. HIL Based Real-Time Co-Simulation for BEV Fault Injection Testing; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Loyola-Gonzalez, O. Black-box vs. white-box: Understanding their advantages and weaknesses from a practical point of view. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 154096–154113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moukahal, L.J.; Zulkernine, M.; Soukup, M. Vulnerability-oriented fuzz testing for connected autonomous vehicle systems. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2021, 70, 1422–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, K.; Côté, I.; Frese, T.; Hatebur, D.; Heisel, M. A structured and systematic model-based development method for automotive systems, considering the OEM/supplier interface. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2017, 158, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, A.; Ding, K.; Chen, T.; Janschek, K. Test suite prioritization for efficient regression testing of model-based automotive software. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Software Analysis, Testing and Evolution (SATE), Harbin, China, 3–4 November 2017; pp. 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Juhnke, K.; Tichy, M.; Houdek, F. Challenges concerning test case specifications in automotive software testing: Assessment of frequency and criticality. Softw. Qual. J. 2021, 29, 39–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enisz, K.; Fodor, D.; Szalay, I.; Kovacs, L. Reconfigurable real-time hardware-in-the-loop environment for automotive electronic control unit testing and verification. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag. 2014, 17, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sini, J.; Mugoni, A.; Violante, M.; Quario, A.; Argiri, C.; Fusetti, F. An automatic approach to integration testing for critical automotive software. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th International Conference on Design & Technology of Integrated Systems in Nanoscale Era (DTIS), Taormina, Italy, 9–12 April 2018; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Amalfitano, D.; De Simone, V.; Maietta, R.R.; Scala, S.; Fasolino, A.R. Using tool integration for improving traceability management testing processes: An automotive industrial experience. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2019, 31, e2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.Y.; Lee, J.W. Fault Localization by Comparing Memory Updates between Unit and Integration Testing of Automotive Software in an Hardware-in-the-Loop Environment. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, K.; Holling, D.; Côté, I.; Hatebur, D. A structured hazard analysis and risk assessment method for automotive systems—A descriptive study. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2017, 158, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugler, C. Systematic Derivation of Feature-Driven and Risk-Based Test Strategies for Automotive Applications; RWTH Aachen University: Achen, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Grandell, J. Aspects of Risk Theory; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bühlmann, H. Mathematical Methods in Risk Theory; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- De Almeida, C.D.A.; Feijó, D.N.; Rocha, L.S. Studying the impact of continuous delivery adoption on bug-fixing time in apache’s open-source projects. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 18–20 May 2022; pp. 132–136. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.W. The cost and benefit of interdepartmental collaboration: An evidence from the US Federal Agencies. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019, 43, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.M.; Maxwell, T.A. Information-sharing in public organizations: A literature review of interpersonal, intra-organizational and inter-organizational success factors. Gov. Inf. Q. 2011, 28, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markos, E.; Milne, G.R.; Peltier, J.W. Information sensitivity and willingness to provide continua: A comparative privacy study of the United States and Brazil. J. Public Policy Mark. 2017, 36, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Rui, Z. Study on the Integration Framework and Reliable Information Transmission of Manufacturing Inte-grated Services Platform. J. Comput. 2013, 8, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sandmann, G.; Seibt, M. Autosar-Compliant Development Workflows: From Architecture to Implementation-Tool Interoperability for Round-Trip Engineering and Verification and Validation; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Riasanow, T.; Galic, G.; Böhm, M. Digital Transformation in the automotive industry: Towards a generic value network. In Proceedings of the 25th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Guimaraes, Portugal, 5–10 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg, S.; van der Vleuten, C.P.M.; Eva, K.W. The hidden value of narrative comments for assessment: A quantitative reliability analysis of qualitative data. Acad. Med. 2017, 92, 1617–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, J.; Rivett, R.; Habli, I.; Bradshaw, B.; Botham, J.; Higham, D.; Jesty, P.; Monkhouse, H.; Palin, R. Safety cases and their role in ISO 26262 functional safety assessment. In Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security, Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference, SAFECOMP 2013, Toulouse, France, 24–27 September 2013; Proceedings 32; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 154–165. [Google Scholar]

- Döringer, S. ‘The problem-centred expert interview’. Combining qualitative interviewing approaches for investigating implicit expert knowledge. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2021, 24, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vöst, S. Vehicle level continuous integration in the automotive industry. In Proceedings of the 2015 10th Joint Meeting on Foundations of Software Engineering, Bergamo, Italy, 30 August–4 September 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1026–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Hodel, K.N.; Da Silva, J.R.; Yoshioka, L.R.; Justo, J.F.; Santos, M.M.D. FAT-AES: Systematic Methodology of Functional Testing for Automotive Embedded Software. IEEE Access 2021, 10, 74259–74279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, T.; Nagappan, N. Predicting subsystem failures using dependency graph complexities. In Proceedings of the 18th IEEE International Symposium on Software Reliability (ISSRE’07), Trollhattan, Sweden, 5–9 November 2007; pp. 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Theissler, A. Detecting known and unknown faults in automotive systems using ensemble-based anomaly detection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2017, 123, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, P.Ü.T.Z.; Murphy, F.; Mullins, M.; Maier, K.; Friel, R.; Rohlfs, T. Reasonable, adequate and efficient allocation of liability costs for automated vehicles: A case study of the German Liability and Insurance Framework. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2018, 9, 548–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Buettner, K.; Prokop, G. Methods for virtual validation of automotive powertrain systems in terms of vehicle drivability-A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 27043–27065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antinyan, V. Revealing the complexity of automotive software. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, Online, 8–13 November 2020; pp. 1525–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaide, S.; Kosmidis, L.; Hernandez, C.; Abella, J. Software-only based diverse redundancy for asil-d automotive applications on embedded hpc platforms. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Defect and Fault Tolerance in VLSI and Nanotechnology Systems (DFT), Frascati, Italy, 19–21 October 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Vogelsang, A. Feature dependencies in automotive software systems: Extent, awareness, and refactoring. J. Syst. Softw. 2020, 160, 110458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, M.; Feng, W. Cybersecurity testing for automotive domain: A survey. Sensors 2022, 22, 9211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardimento, P.; Dinapoli, A. Knowledge extraction from on-line open source bug tracking systems to predict bug-fixing time. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Web Intelligence, Mining and Semantics, Amantea, Italy, 19–22 June 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Ren, X.; Li, H.; Jiang, F.; Yu, X. Prediction of bug-fixing time based on distinguishable sequences fusion in open source software. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2023, 35, e2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelsang, A.; Teuchert, S.; Girard, J.F. Extent and characteristics of dependencies between vehicle functions in automotive software systems. In Proceedings of the 2012 4th International Workshop on Modeling in Software Engineering (MISE), Zurich, Switzerland, 2–3 June 2012; pp. 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Muscedere, B.J.; Hackman, R.; Anbarnam, D.; Atlee, J.M.; Davis, I.J.; Godfrey, M.W. Detecting feature-interaction symptoms in automotive software using lightweight analysis. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 26th International Conference on Software Analysis, Evolution and Reengineering (SANER), Hangzhou, China, 24–27 February 2019; pp. 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Muscedere, B.J. Detecting Feature-Interaction Hotspots in Automotive Software Using Relational Algebra. Master’s Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pett, T.; Eichhorn, D.; Schaefer, I. Risk-based compatibility analysis in automotive systems engineering. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM/IEEE International Conference on Model Driven Engineering Languages and Systems: Companion Proceedings, Montreal, QC, Canada, 18–23 October 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Durisic, D.; Staron, M.; Nilsson, M. Measuring the size of changes in automotive software systems and their impact on product quality. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Product Focused Software Development and Process Improvement, Torre Canne, Italy, 20–22 June 2011; pp. 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ryberg, A.B. Metamodel-Based Multidisciplinary Design Optimization of Automotive Structures; Linköping University Electronic Press: Linkoping, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sholiq, S.; Sarno, R.; Astuti, E.S.; Yaqin, M.A. Implementation of COSMIC Function Points (CFP) as Primary Input to COCOMO II: Study of Conversion to Line of Code Using Regression and Support Vector Regression Models. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 2023, 16, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanthara, S.; Dajsuren, Y.; Cleophas, L.; van den Brand, M. Painting the landscape of automotive software in GitHub. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 18–20 May 2022; pp. 215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Waez, M.T.B.; Rambow, T. Verifying Auto-generated C Code from Simulink. In Formal Methods, Proceedings of the 22nd International Symposium, FM 2018, Held as Part of the Federated Logic Conference, FloC 2018, Oxford, UK, 15–17 July 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 10951, pp. 312–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hewett, R.; Kijsanayothin, P. On modeling software defect repair time. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2009, 14, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Huang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, B. Examining the effects of developer familiarity on bug fixing. J. Syst. Softw. 2020, 169, 110667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalabrino, S.; Linares-Vásquez, M.; Oliveto, R.; Poshyvanyk, D. A comprehensive model for code readability. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2018, 30, e1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Wang, L. A method for designing and analyzing automotive software architecture: A case study for an autonomous electric vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computer Engineering and Artificial Intelligence (ICCEAI), Shanghai, China, 27–29 August 2021; pp. 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Arlt, S.; Morciniec, T.; Podelski, A.; Wagner, S. If A fails, can B still succeed? Inferring dependencies between test results in automotive system testing. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 8th International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation (ICST), Graz, Austria, 13–18 April 2015; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Haidry, S.-e.-Z.; Miller, T. Using dependency structures for prioritization of functional test suites. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2012, 39, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsalou, M.; Perkin, R. Statistical problem-solving teams: A case study in a global manufacturing organization in the automotive industry. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2024, 40, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodendorf, F.; Lutz, M.; Franke, J. Valuation and pricing of software licenses to support supplier–buyer negotiations: A case study in the automotive industry. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2021, 42, 1686–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustinza, O.F.; Lafuente, E.; Rabetino, R.; Vaillant, Y.; Vendrell-Herrero, F. Make-or-buy configurational approaches in product-service ecosystems and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, R.; Ejigu, S.K.; Gay, G.; Filipovikj, P. Identifying Redundancies and Gaps Across Testing Levels During Verification of Automotive Software. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation Workshops (ICSTW), Dublin, Ireland, 16–20 April 2023; pp. 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, R.; Staron, M.; Hansson, J.; Nilsson, M. Defect prediction over software life cycle in automotive domain state of the art and road map for future. In Proceedings of the 2014 9th International Conference on Software Engineering and Applications (ICSOFT-EA), Vienna, Austria, 29–31 August 2014; pp. 377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Z.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, G. A security risk assessment method of website based on threat analysis combined with AHP and entropy weight. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering & Service Science, Beijing, China, 24–26 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Heeager, L.; Nielsen, P. A conceptual model of agile software development in a safety-critical context: A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2018, 103, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchler, C.; Khatiri, S.; Bosshard, B.; Gambi, A.; Panichella, S. Machine learning-based test selection for simulation-based testing of self-driving cars software. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2023, 28, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.F.I.; Mahmud, F.U.; Hoseen, A.; Masum, A.K.M. A new approach of software test automation using AI. J. Basic Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 559–570. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).