Abstract

The dynamic evolution of collective emotions across the news dissemination life-cycle is a powerful yet underexplored signal in affective computing. While phenomena like the spread of fake news depend on eliciting specific emotional trajectories, existing methods often fail to capture these crucial dynamic affective cues. Many approaches focus on static text or propagation topology, limiting their robustness and failing to model the complete emotional life-cycle for applications such as assessing veracity. This paper introduces C-STEER (Cycle-aware Sentiment-Temporal Emotion Evolution), a novel framework grounded in communication theory, designed to model the characteristic initiation, burst, and decay stages of these emotional arcs. Guided by Diffusion of Innovations Theory, C-STEER first segments an information cascade into its life-cycle phases. It then operationalizes insights from Uses and Gratifications Theory and Emotional Contagion Theory to extract stage-specific emotional features and model their temporal dependencies using a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM). To validate the framework’s descriptive and predictive power, we apply it to the challenging domain of fake news detection. Experiments on the Weibo21 and Twitter16 datasets demonstrate that modeling life-cycle emotion dynamics significantly improves detection performance, achieving F1-macro scores of 91.6% and 90.1%, respectively, outperforming state-of-the-art baselines by margins of 1.6% to 2.4%. This work validates the C-STEER framework as an effective approach for the computational modeling of collective emotion life-cycles.

1. Introduction

In the era of digital communication, social networks have become the central hub of global information circulation. Their capacity for immediate content creation and dissemination improves the speed of access to information, while also providing fertile ground for the emergence and spread of fake news. Beyond distorting information, fake news can disrupt social order, interfere with public decision-making, and even threaten public safety; thus, the development of efficient and accurate detection techniques is of substantial practical significance [1,2,3].

Mainstream detectors suffer from two limitations. First, text-driven methods rely on pretrained language models such as BERT and RoBERTa to capture semantic and stylistic cues and often report strong results on standard benchmarks. However, they operate largely on static text and make no explicit use of user interactions or propagation paths, making them brittle when semantics appear plausible but diffusion is anomalous [4,5]. Second, graph-structure methods construct user–news interaction graphs to extract topological features (e.g., retweet centralization, influence of core nodes) and can be robust in some datasets, yet they typically ignore the temporal evolution of emotions and the mechanism of emotional contagion during propagation, which hampers their ability to distinguish emotion-driven from fact-driven diffusion [6,7]. For example, the SA-HyperGAT model of Dong et al. (2022) misclassifies up to 18% of real breaking news (e.g., natural disaster updates) because their propagation graphs resemble those of fake news [8]. One reason is the absence of an emotion dimension, although emotion is a key driver of fake news diffusion [9]. This raises a central scientific question: Can we model such emotional dynamics from the intrinsic regularities of information propagation? Communication theories provide a solid foundation for doing so [6,10,11].

To address these challenges, we characterize stage-wise emotion dynamics over the news life-cycle through the lens of communication theory. Following diffusion theory, we partition the propagation process into three stages—initiation, burst, and decay—corresponding, respectively, to small-scale exploratory spread, rapid large-scale amplification, and a subsequent waning of attention. Within each stage, the polarity and intensity of emotions in comments/retweets, the composition of emotions, and their consistency/divergence evolve systematically: initiation is dominated by low-arousal emotions such as curiosity and verification; burst sees rising proportions and stronger consistency of high-arousal emotions (e.g., anger, fear); decay features more skepticism, debunking, and sarcasm, trending toward divergence. This operationalizes “stage-wise emotion dynamics” and offers cues for disentangling different propagation drivers [9,12,13].

Building on this insight, we propose C-STEER. C-STEER segments the life-cycle per diffusion theory [10]; extracts stage-wise emotion features under Uses and Gratifications [14]; constructs a heterogeneous interaction graph grounded in social network theory [7,15]; and, inspired by Emotional Contagion Theory, employs a bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) to learn the temporal dependencies of collective emotions [6,16]. Finally, these signals are fused with textual semantics and graph topology for classification [17,18,19].

On the implementation side, we translate abstract mechanisms—“emotion–need matching,” “structural anomalies in networks,” and “temporal dependencies of emotional contagion”—into quantifiable features: emotion time-series features under life-cycle segmentation [9,10]; graph features based on emotional synchrony and similarity [20]; and semantic features capturing textual differences. An attention-weighted multi-feature fusion model then enables precise fake news detection. Beyond addressing fragmentation at the theory level, the approach exhibits broad cross-platform and cross-lingual adaptability, validated on two real-world datasets, Weibo21 and Twitter16 [4,5,17,18].

To further assess effectiveness, we conduct ablation studies showing that theory-guided emotion features grounded in diffusion theory yield significant performance gains, outperforming methods that rely solely on graph structure or that lack theory-informed emotion modeling [9,21].

2. Related Work

Research on fake news detection has evolved along two axes: (i) expanding the feature space from pure text to interaction structures and multi-modal signals, and (ii) deepening the modeling granularity from static representations to temporal dynamics and mechanism/causal perspectives. Accordingly, existing approaches can be grouped into four families—traditional machine learning, text-driven deep learning, graph-based modeling, and temporal-dynamics modeling—with a growing trend toward content–structure–time fusion [1,22,23,24,25].

Traditional machine learning: Early studies relied on hand-crafted features combined with classical classifiers, focusing on surface writing style and basic interaction statistics. Typical setups include TF–IDF + SVM, stylometry/syntactic metrics + Random Forest, and lexicon-based sentiment (e.g., VADER/LIWC) + Naïve Bayes (often used as baselines in 2021–2023). These methods are interpretable and require limited labeled data, but they struggle to capture deep semantics and dynamic propagation and generalize poorly across platforms.

Deep learning driven by text: With the rise of Transformers and pretrained language models (PLMs), text-centric methods have become mainstream, learning deep semantic and stylistic features without manual engineering. Representative works include SSE-BERT (injecting dependency syntax and sentiment resources into BERT for early detection) [19], FOREAL (adding emotion supervision/transfer on RoBERTa) [1], and domain/language-specific models such as MARBERT/AraBERT-Twitter [2,3]. However, content-only approaches typically ignore propagation structure and stage-wise dynamics, making them brittle when “semantically plausible but propagation-abnormal” cases arise [26]. Motivated by this gap, we augment content modeling with diffusion life-cycle segmentation and stage-wise emotion modeling [16,26,27].

Graph-based modeling: This line makes the user–news–interaction relations explicit as graphs, leveraging Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs)/Graph Attention Networks (GATs)/hypergraph variants to learn topological patterns such as core nodes, centralized resharing, and communities. Recent examples include SA-HyperGAT (sentiment hypergraph/hyperedges, 2022), MDE (Mining Dual Emotion) (jointly modeling publisher emotion vs. social emotion, 2021) [23], and propagation-structure-aware graph Transformers (2024) [15,28]. While powerful for structural patterns, these methods often treat emotion as a static attribute and underplay temporal aspects, making them hard to couple with propagation stages. Consequently, we use graph structure as a lightweight support, emphasizing the fusion of stage-wise emotions with textual semantics [14,23,28,29].

Temporal-dynamics modeling: Here, interactions are viewed as time series or cascades, modeled via Rerrent Neural Network (RNN)/Gate Recurrent Unit (GRU)/LSTM, snapshot graphs, and recursive/tree structures to learn diffusion rhythms, with notable benefits for early detection. Examples include TDEI (temporal snapshot graphs + GRU, 2021) [20,26] and extensions based on dynamic hypergraphs/multi-view learning (2023–2024) [8,20,30]. However, global averaging of emotions often masks stage differences, and link-level emotional contagion, synchrony, and convergence speed remain under-modeled [6,9,12,13]. To this end, we adopt a BiLSTM with attention and an emotional-contagion perspective to capture bidirectional temporal dependencies and synchrony across interaction nodes [6,24,26].

Summary and gap: The field has progressed from hand-crafted features to deep semantics, and further to structure/temporal fusion. Each paradigm contributes a distinct strength: traditional methods favor interpretability, text methods excel at semantic capture, graph methods characterize propagation topology, and temporal methods trace evolutionary regularities. Yet three gaps persist: (i) lack of a unifying communication-theory constraint, limiting cross-scenario adaptability; (ii) emotion is largely treated as static, overlooking life-cycle phase differences [9,10]; and (iii) insufficient explicit modeling of link-level contagion, synchrony, and convergence speed [6,8,20,31].

Our approach: We propose C-STEER (Cycle-aware Sentiment-Temporal Emotion Evolution for Fake News Detection), which organizes content, structure, and time under communication theory: (1) guided by diffusion theory, we segment the life-cycle by propagation rate and coverage into initiation–burst–decay [10]; (2) drawing on Uses and Gratifications, we construct stage-wise emotion features (polarity/intensity/composition/consistency, etc.) and, via an emotional-contagion lens, use BiLSTM to model bidirectional temporal dependencies of group emotions [6,14,24,26]; (3) under social-network theory, we build a heterogeneous interaction graph and fuse it with textual semantics and stage-wise emotions through attention for final classification [7,15]. Experiments on Twitter and Chinese Weibo provide overall comparisons and ablations, demonstrating advantages in accuracy, robustness, and cross-platform/cross-lingual adaptability [15,23,24,28].

3. Model Details

3.1. Overall Framework

We present C-STEER, a communication-theory-guided pipeline that progresses from life-cycle segmentation, through stage-wise emotion modeling and BiLSTM-with-attention temporal encoding, to graph-structural modeling and final multi-feature fusion [6,9,10,15,24,28].

The remainder of this section details each component: Section 3.2 describes the heterogeneous graph construction; Section 3.3 and Section 3.4 explain the core contribution—life-cycle segmentation and stage-wise emotion extraction; Section 3.5 presents the text encoder; and Section 3.6 outlines the final multi-modal fusion and classification layer.

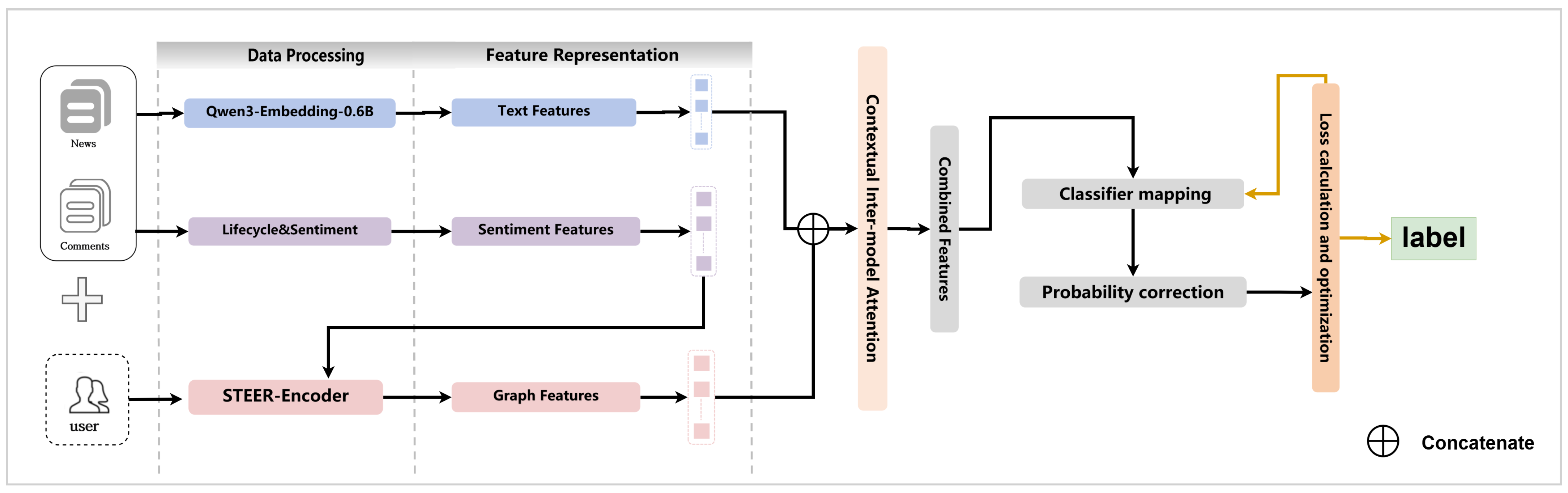

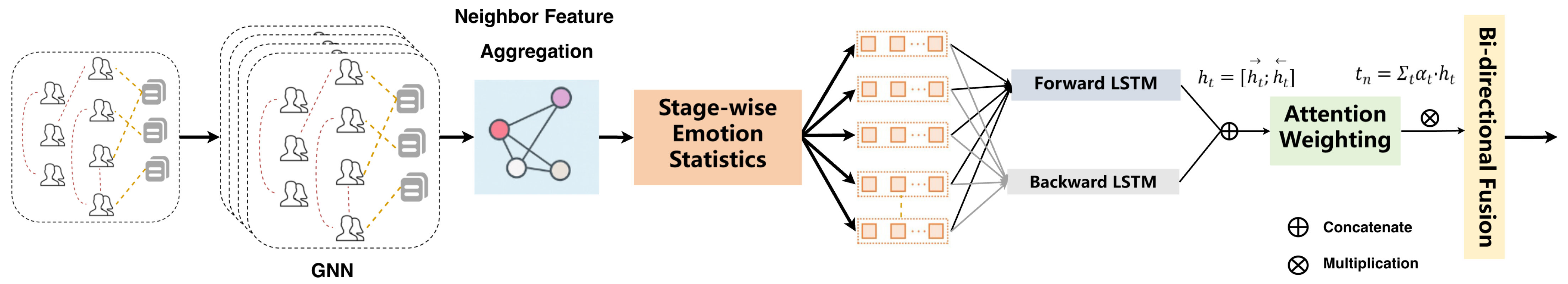

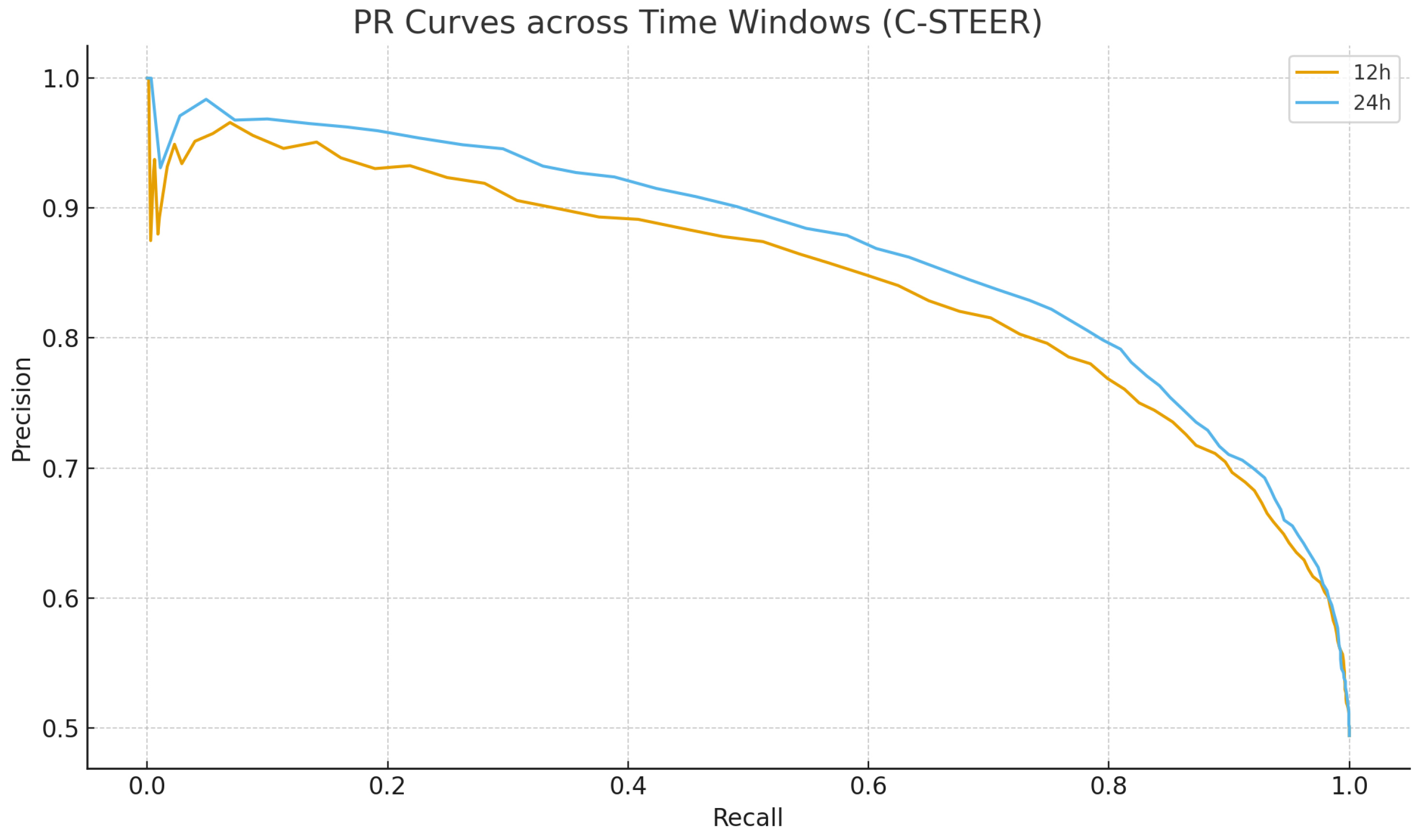

Grounded primarily in diffusion theory, and synergizing social network theory, Uses and Gratifications, and Emotional Contagion Theory, C-STEER builds a tightly coupled theory–module–feature framework to fuse textual semantics, dynamic emotions, and basic structural signals for fake news detection [6,7,10,14]. As illustrated in Figure 1, the architecture progresses from data preprocessing and theory-guided feature extraction to multi-feature fusion and final classification [21,32].

Figure 1.

Overview of the C-STEER architecture.

The correspondence between communication theories and model modules is summarized in Table 1, ensuring theory-grounded design and technically accountable implementation.

Table 1.

Mapping between communication theories and model components.

The pipeline comprises three phases:

- Data preprocessing: The data preprocessing phase involves two main steps. First, user–news interaction records are cleaned via deduplication and timestamp completion, and user stances are annotated (support, denial, neutral, retweet). Second, news text is preprocessed using standard tokenization and stopword removal.

- Parallel feature extraction: The graph module constructs a heterogeneous graph and derives structural features [7,15]. The life-cycle module partitions propagation into stages based on interaction signals [10]. The emotion–temporal module extracts stage-wise dynamic emotions and models temporal dependencies [6,9,24,26]. The text module obtains semantic representations using a pretrained language model [33,34].

- Feature fusion and classification. All feature streams are projected to 64 dimensions and then fused via concatenation and linear transformations to enable cross-feature interaction. The classifier outputs the probability that a news item is fake; we adopt a decision threshold of 0.5, i.e., the item is predicted as fake if > 0.5 [18,21].

3.2. Graph Construction

Guided by social network theory (heterogeneous ties and the strength-of-weak-ties in user interaction networks) and Emotional Contagion Theory (convergence and amplification of emotions in group interactions) [6,7], we build a user–news heterogeneous graph that captures propagation structure and the backdrop of emotional synchrony. The goal of graph-based features is to characterize association patterns between user–news and user–user pairs [6,7,8,15,20,28].

- Nodes: We include news nodes and user nodes.

- News nodes: initial features comprise publication time and the global mean emotion.

- User nodes: initial features comprise the historical stance distribution and interaction activeness.

- Edges and weights (emotion-driven design): We instantiate two edge types:

- User–news interaction edges: if a user engages with a news item at time t (retweet, comment, like, etc.), an edge is created. Its weight is jointly determined by time decay, the emotion intensity of the interaction text, and the emotional similarity (synchrony) to the news item’s current mean emotion.

- User–user co-occurrence edges: if two users co-engage with the same news item, an edge is created. Its weight is obtained by normalizing a combination of co-occurrence frequency and emotional similarity [8,20,23,30].

- Structural feature learning: We adopt a lightweight neighbor sampling and aggregation scheme to preserve topology while remaining efficient:

- Neighbor sampling: To mitigate degree-induced bias, each layer samples a fixed number of neighbors per node [31]. If the neighborhood size exceeds the threshold, we sample without replacement; if it falls short, we allow sampling with replacement to avoid information loss [31].

- Neighbor aggregation: Sampled neighbor features are aggregated via a weighted mean that emphasizes neighbors with higher emotional synchrony and stronger emotion intensity. The aggregated vector is then concatenated with the node’s own features and passed through a linear transformation plus activation to yield updated node representations.

Finally, news-node structural features are forwarded to subsequent modules, whereas user nodes serve only as intermediate auxiliaries. This design balances efficiency and accuracy on large-scale user–news networks. As reported in Section 4.3, when using only graph-structure features as input to the classifier on Weibo21, accuracy remains below 90%, markedly lower than that of the full model with emotion and text features. This corroborates our “light graph, heavy emotion dynamics” design choice: graph structure acts as an auxiliary in multi-feature fusion, providing relational context for emotion and semantic signals [8,15,20,28].

3.3. Life-Cycle Segmentation of News

Diffusion of Innovations (Rogers, 1962) [10] posits that news, as an informational innovation to be diffused, typically follows an S-shaped adoption curve—from awareness among a few, to mass diffusion, to saturation. This pattern differs markedly between fake and real news: fake news, relying on emotional arousal, often exhibits a burst-like onset and rapid decay with pronounced stage-specific emotional differences, whereas real news, driven by factual information, tends to show a stable onset and gradual decay (Liu et al. 2024) [9,21,26].

Rationale and Scope: While information propagation can exhibit complex patterns, empirical studies on large-scale cascades (Zhao et al. [35], Pfeffer et al. [36]) demonstrate that misinformation typically follows a dominant “activation–peak–decay” trajectory. Our model targets this dominant dynamic. Crucially, our segmentation is not rigid; by employing the adaptive sliding window (detailed in Section 3.3.1) and main-peak detection, the framework dynamically adjusts to the specific tempo of each event, maintaining robustness even in scenarios with secondary fluctuations.

Building on this theory, we use propagation rate (diffusion speed) and diffusion scope (coverage scale) as core quantitative indicators, and—considering social media propagation characteristics—partition the news life-cycle into three stages: initiation, burst, and decay. Table 2 details the theoretical definitions and computable criteria for these stages, ensuring verifiable boundaries and avoiding subjective segmentation bias [10,21].

Table 2.

Stage definitions and quantitative criteria for life-cycle segmentation.

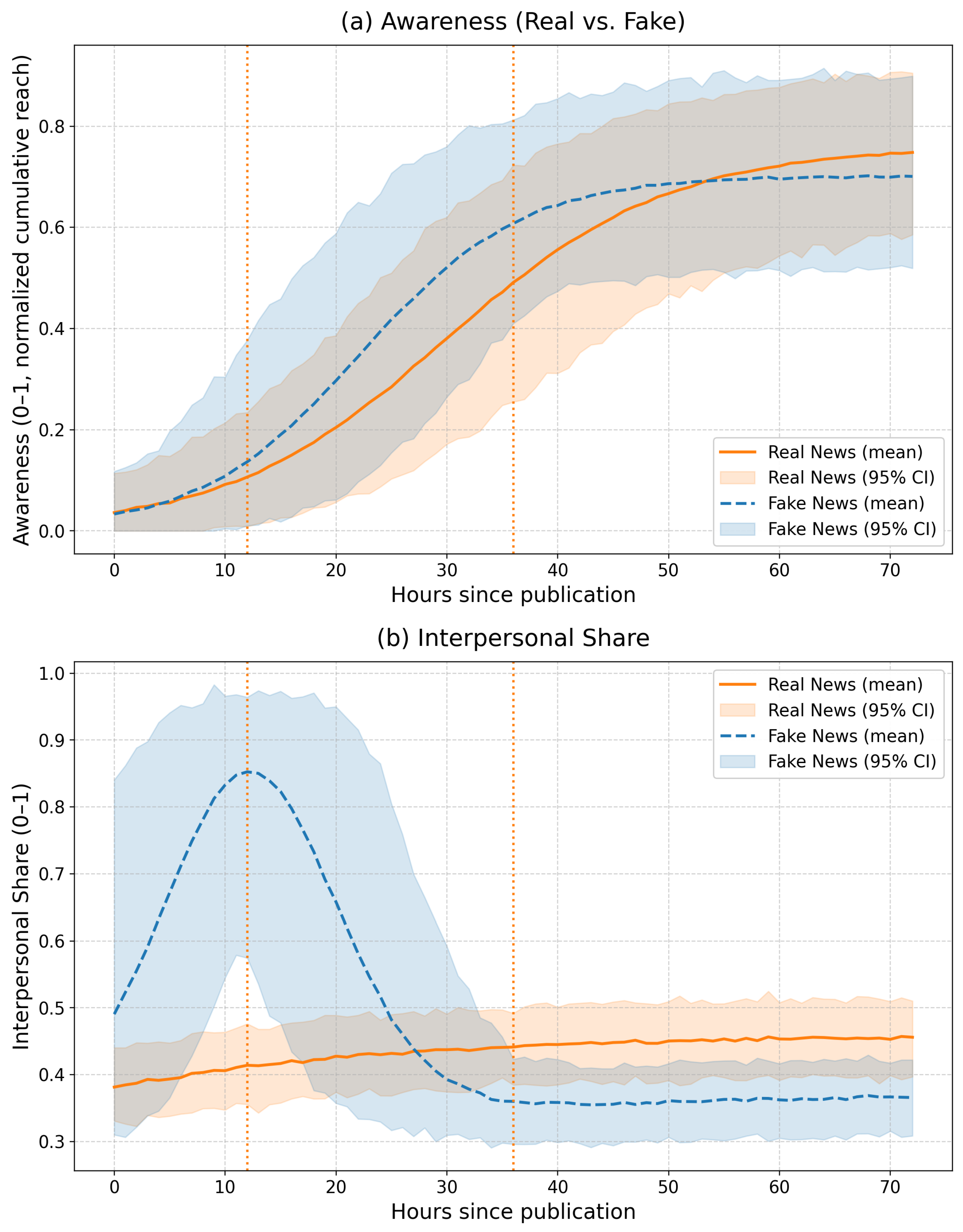

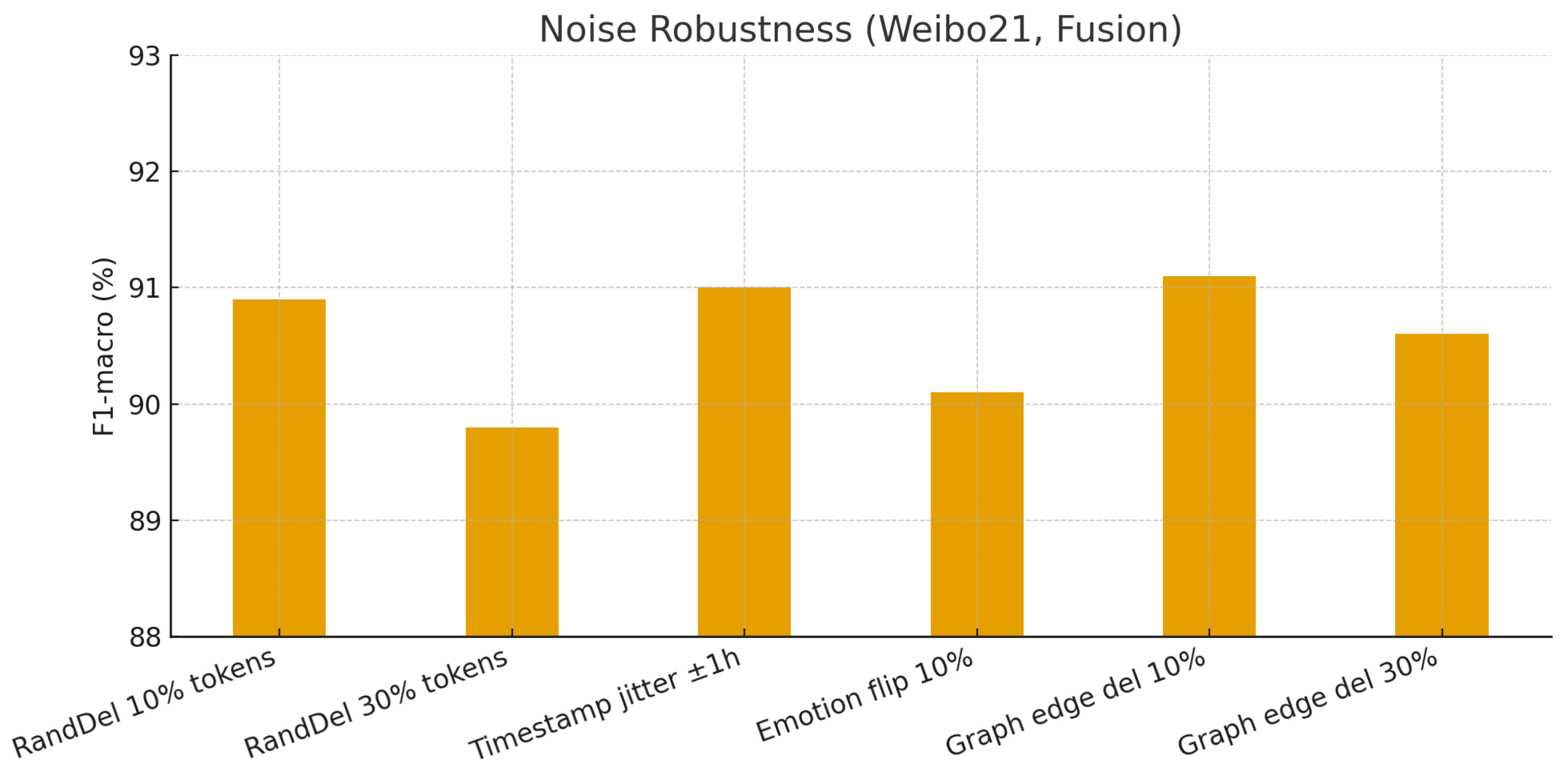

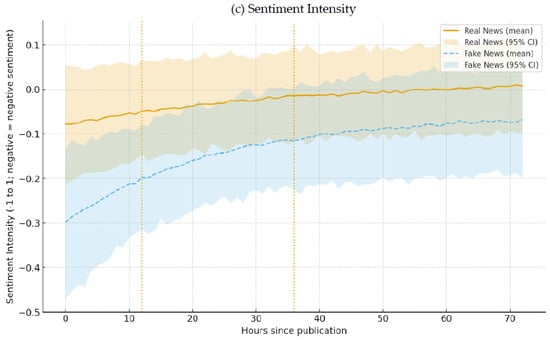

We validate the rationality of the stage segmentation through a pilot study on Weibo21 (4488 fake; 4640 real) and Twitter16 (818 items, including 205 fake rumors). For each news item, we track over time: (i) awareness rate (normalized cumulative coverage), (ii) the share of interpersonal propagation, and (iii) emotion intensity using BERT-Emotion (range [−1, 1]; negative values denote negative valence). We then aggregate items within the same class to obtain mean trajectories with 95% confidence intervals. Results are shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

(a) Awareness, (b) interpersonal share, (c) sentiment intensity (real vs. fake).

- (1)

- Awareness exhibits a typical cumulative pattern, with fake news growing faster in the early stage;

- (2)

- The interpersonal propagation share in fake news rises first and then recedes, whereas real news remains overall more stable;

- (3)

- In terms of emotion intensity, fake news is more negative during the initiation and burst stages, and gradually reverts toward neutrality thereafter.

These trends accord with the initiation–burst–decay staging and support the interpretability of our segmentation.

3.3.1. Life-Cycle Segmentation

Building on the above theoretical criteria, we implement adaptive life-cycle segmentation by first estimating propagation rates, then detecting peaks, and finally determining phase boundaries, so that the resulting phases conform to real diffusion dynamics. The steps are as follows.

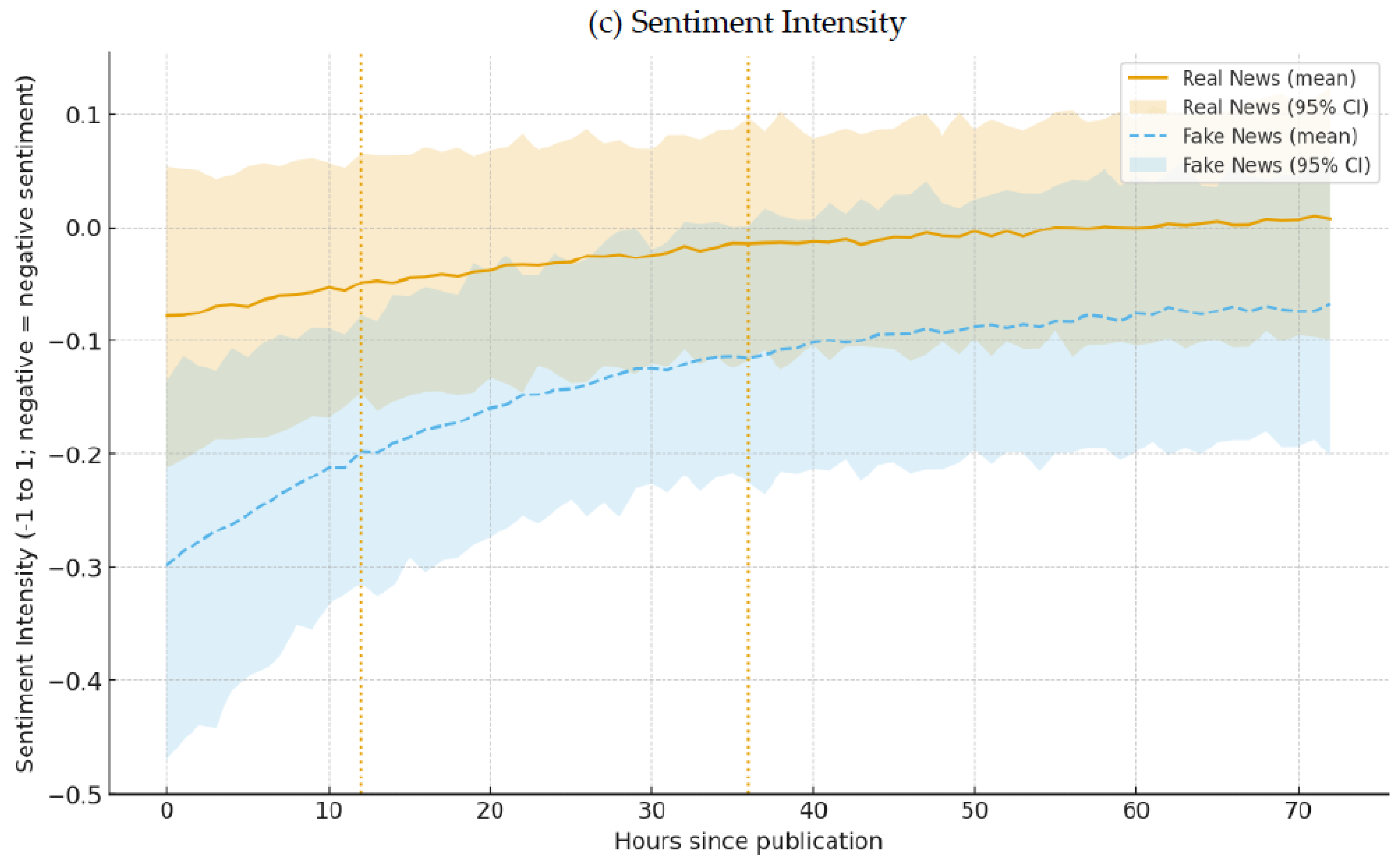

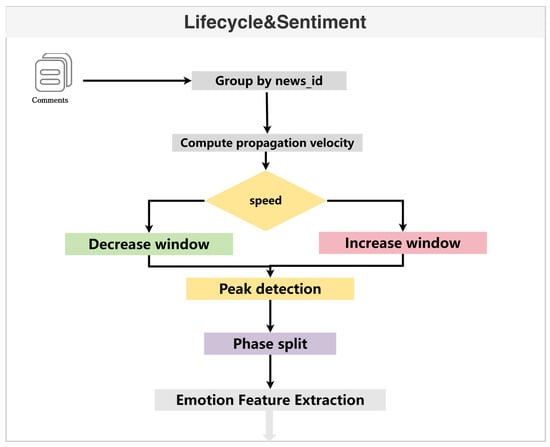

Propagation rate is the core indicator of diffusion speed and directly determines the accuracy of phase boundaries. Fixed-size windows are prone to bias during the burst stage (dense interactions) and the decay stage (sparse interactions). We therefore adopt a sliding window with adaptive window length, designed as follows [21]. The adaptive segmentation pipeline is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Adaptive life-cycle segmentation and stage-wise emotion feature extraction.

Let the interaction timestamp sequence of news item n be (with K total interactions sorted in ascending time). We compute the propagation speed using a sliding window with dynamic window size:

- (1)

- Sliding-window configuration.

Window length : adaptively adjusted according to the current propagation speed to avoid the bias introduced by a fixed window in the burst (interaction-dense) or decay (interaction-sparse) periods.

Let denote the propagation speed in the previous window, and use the smoothing function . When diffusion is fast (large ), the window length is lower-bounded at 600 s (10 min) to capture rapid changes in the burst stage; when diffusion is slow (small ), is upper-bounded at 3600 s (1 h) to avoid empty windows that would yield zero speed estimates. The sliding step is set to , balancing temporal resolution and computational efficiency [20,26].

Rationale. This strategy adaptively senses changes in propagation speed: it uses higher temporal resolution in the rapidly varying burst phase and increased smoothing in the more gradual decay phase, thereby improving the accuracy and robustness of rate estimation.

- (2)

- Instantaneous propagation speed.

For each sliding window with (), let be the total count of user interactions (summing retweets, comments, and likes) within the sliding window . The instantaneous speed at the window midpoint is

The factor 3600 converts the unit to events per hour, facilitating cross-item comparison.

3.3.2. Phase Segmentation Algorithm

Given the propagation-speed sequence (with M sliding windows), peaks serve as the key marker for the burst phase. We detect peaks using scipy.signal.find_peaks, with parameters set under diffusion-theory guidance to retain only salient peaks and suppress noise. The procedure is as follows:

- (1)

- Peak-detection parameterization

Using scipy.signal.find_peaks, we set the key parameters under diffusion-theory guidance to retain only salient peaks and suppress noise:

- Prominence: Set to the 50th percentile (median) of the non-zero values in the speed sequence, ensuring only significant peaks are detected;

- Width: Set to (where denotes the floor function), ensuring that each detected peak corresponds to a sustained high-speed interval;

- Distance: Set to , preventing adjacent windows from being repeatedly flagged as peaks.

If the detected peaks are (with q peaks), we select the one with the largest prominence, as the main peak (the core stage of propagation). If no peak is found (e.g., few interactions or no clear onset), we determine phase boundaries via cumulative-sum change-point detection.

- (2)

- Phase-boundary determination

Let denote the speed at the main peak and its time (the midpoint of window ). Based on the quantitative criteria from diffusion theory, we set the three boundaries as follows:

- Initiation: Starts at the first interaction time and ends at the time corresponding to the window 20% before the main peak:

Here, returns the midpoint time of the x-th window. The 20% lead captures the accelerating pre-peak interval.

- Burst: Starts at , and ends at the time corresponding to the window 30% after the main peak, which includes the post-peak plateau:

- Decay: Starts at , and ends at the last interaction time , with the additional requirement that the propagation speed in this stage stays below 20% of the peak

- (3)

- Special cases

If the total number of interactions K < 3: no life-cycle segmentation is performed; we mark the item as “no phase”, and downstream emotion features fall back to global statistics.

If no peak is detected, compute the cumulative sum

where is the mean speed; take the time corresponding to the maximum absolute cumulative deviation as the change point . The life-cycle is then split into Initiation [,] and Decay [,], with the Burst stage left empty.

3.4. Stage-Wise Emotion Feature Extraction Under the Life-Cycle

The core proposition of Uses and Gratifications (Katz, 1974) is that users actively select, engage with, and disseminate information to satisfy psychological needs [11,14]; on social media, behaviors such as retweeting and commenting are essentially need-driven emotional expressions [9,27]. This regularity is especially salient in the diffusion of fake news:

- Initiation: Users participate primarily to vent emotions, expressing initial stances toward the news via comments (e.g., anger, surprise and other negative emotions). Emotional expressions tend to be individualized and strongly polarized [9,27].

- Burst: Dense interactions arise from needs for social identity and crisis response. Collisions among users holding opposing stances intensify emotional volatility, with a marked rise in extreme emotions (e.g., strong anger, panic) [9,12,13,27].

- Decay: As needs are gradually satisfied, expression shifts from heated engagement to rational observation; the share of neutral emotion increases, and overall emotional intensity shows a steadily declining trend [9,23].

In summary, these twelve static features furnish a comprehensive emotional profile for each propagation stage from four perspectives: central tendency (mean, ), dispersion (standard deviation, ), polarity distribution (share of negative valence), and participant structure (user entropy), as summarized in Table 3 [9,22,23].

Table 3.

Stage-wise and cross-stage emotion features.

Building on the above theory and the three-stage segmentation (initiation–burst–decay), we extract static emotion features (capturing within-stage distributions) and dynamic emotion features (capturing cross-stage evolution), yielding a 13-dimensional emotion feature vector [20,26]. The static features reflect the emotion manifestation of stage-specific user needs, whereas the dynamic feature reflects need-driven emotional shifts across stages. Each feature is tightly coupled with user behavioral logic and has a clear quantitative definition.

3.4.1. Extraction of Stage-Wise Static Emotion Features

To bridge the gap between communication theory and computational modeling, we operationalize abstract theoretical constructs into quantifiable vectors. Based on Uses and Gratifications Theory, we map the user’s ‘need for venting’ to the Negative-Valence Ratio, and the ‘diversity of user needs’ to User Entropy. Similarly, drawing from Emotional Contagion Theory, the volatility of collective sentiment is measured via Emotion Standard Deviation. Specifically, for each stage of the life-cycle—initiation, burst, and decay—we computed four static features (emotion mean, emotion standard deviation, negative-valence ratio, and user entropy), totaling 12 dimensions. We then add one cross-stage emotion change rate, forming a 13-dimensional stage emotion feature vector . For clarity in the subsequent experimental analysis, we refer to this specific 13-dimensional feature set capturing stage-wise dynamics as LifeCycle-Emotion. All features are computed from user interactions (comment and retweet texts) [9,22,23].

Stage emotion mean: This statistic reflects the overall emotional tendency within a stage and corresponds to the common expression of user needs in Uses and Gratifications—for example, fake news in the initiation stage often skews negative due to venting needs, whereas real news tends to be more neutral due to information-seeking needs. We compute the time-weighted mean emotion score within the stage:

where is the set of interactions in stage s, is the stance/emotion score of interaction i, and the time weight is

with the interaction time, and , the first and last interaction times within the stage. Table 4 further compares the stage-wise emotion features between fake and real news.

Table 4.

Comparative statistics of stage-wise emotion features.

Stage emotion standard deviation: This metric captures within-stage volatility and corresponds to the “collision of differentiated needs” in Uses and Gratifications. During the burst stage of fake news, needs for social identity intensify clashes among opposing stances, yielding a significantly larger standard deviation than for real news; in the initiation and decay stages, needs are more aligned and the variance is lower. Empirically, the mean emotion standard deviation for fake news in the burst stage is 0.40, exceeding 0.27 for real news—a relative gap of +48%—making it a discriminative stage-specific feature. Formally,

where is the interaction set of stage s, is the stance/emotion score of interaction i, is the time weight (as in Equation (5)), and is the stage mean.

Stage negative-valence ratio: This measures the proportion of negative-stance users in a stage and reflects the concentration of negative needs. Fake news often leverages negative emotions (e.g., anger, fear) to attract interactions, leading to a markedly higher early-stage negative ratio than real news, which emphasizes factual statements. We define

where is the indicator function (1 if < −0.5, i.e., denial or negative support; 0 otherwise). On Weibo21, the initiation-stage negative ratio averages 62% for fake news versus 41% for real news (≈+51%), indicating a stronger early aggregation of negative affect.

Stage user entropy: This characterizes the diversity of interacting users and maps to user-need structure in Uses and Gratifications. Fake news propagation is often dominated by a few highly active or homogeneous clusters, yielding lower entropy; real news engages a more dispersed user set, yielding higher entropy. In the initiation stage, the mean entropy for fake news is 1.80, below 2.40 for real news (≈−25%), suggesting stronger dominance by a few homogeneous clusters:

where is the set of users active in stage s and is user u’s interaction set in stage s. Lower indicates higher concentration among few users.

Cross-stage emotion change rate: Beyond the 12 static features, we add one dynamic feature to capture the shift from venting (initiation) to reversion/neutrality (decay), reflecting the life-cycle evolution of user needs. Because fake news is more affectively charged, it starts with concentrated negativity and then reverts toward neutrality faster once needs are satisfied; real news is more stable. A positive indicates movement from negative toward neutral/positive. On average, is 0.34 for fake news versus 0.22 for real news (≈+55%), evidencing faster reversion for fake news:

3.4.2. Temporal Encoding of Interaction Sequences with BiLSTM

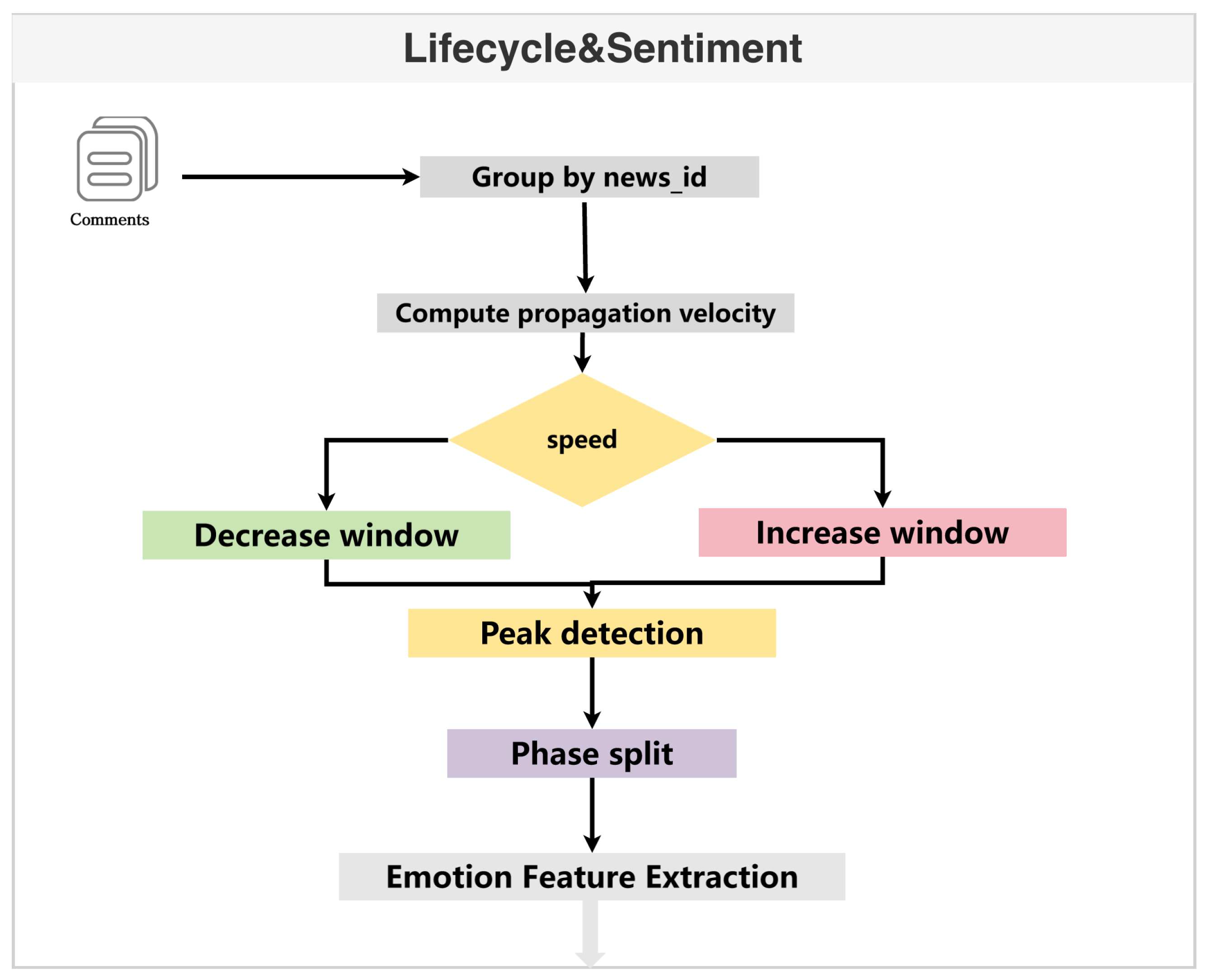

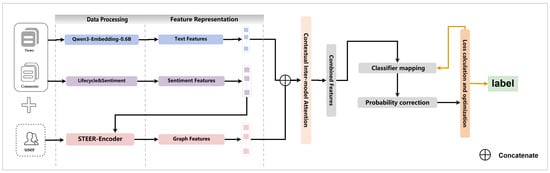

User interaction sequences carry both temporal and stance information. A uni-directional LSTM captures only past dependencies, whereas a bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) learns dependencies from both the past and the future, aligning better with the cause–effect nature of news propagation (e.g., an interaction is influenced by prior ones and, in turn, influences subsequent ones) [17,24,26]. Within each life-cycle window, we use BiLSTM to explicitly model emotional autocorrelation and lagged cross-correlation, and apply an additive attention mechanism to highlight salient timesteps so that the synchrony/convergence of emotional contagion is reflected in the temporal representation [6,24,26]. The internal structure of the STEER-Encoder, which combines graph neighbor aggregation, stage-wise emotion statistics, and BiLSTM-based temporal encoding with attention, is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Internal structure of the STEER-Encoder for graph and emotion sequence encoding.

Sequence construction. For each news item n, we build a fixed-length interaction sequence

where is the feature vector at timestep tconsisting of a normalized timestamp

with the time of the t-th interaction (scaled to [0, 1]), and a 4D one-hot stance vector [, , , ] (where : denial, : negative support, : report, : neutral support).

If the number of interactions , we zero-pad the tail (all-zero feature vectors) and create a mask (1 for valid steps, 0 for padded steps). If , we keep the most recent T interactions (recent context is more informative for temporal dependencies).

BiLSTM encoding: The BiLSTM has a forward LSTM and a backward LSTM that propagate from t = 1 and t = T, respectively, to capture bidirectional temporal dependencies. The forward hidden state summarizes information from 1 to t:

where , , are the input/forget/output gates controlling information inflow, retention, and output; is the cell state, ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication; is the sigmoid; and , are learnable parameters. The backward hidden state aggregates information from T to t; its recurrence mirrors the forward LSTM, with separate parameters:

Bidirectional fusion: For each timestep t, we concatenate the forward and backward states to obtain the full temporal feature:

where ⊕ denotes concatenation (2 = 128).

Additive attention with masking: Since different timesteps contribute unequally (e.g., interactions near the peak are more indicative than those in the decay), we apply additive attention over :

where (with = 64), , and are learnable. To exclude padded steps when , we set their attention logits to a large negative value via the mask:

Temporal aggregation: The news-level temporal feature is the attention-weighted sum:

3.5. Text Feature Extraction

News text (headline and body) encodes key semantic and stylistic cues: fake news often uses hyperbolic rhetoric and affect-laden words with looser discourse structure, whereas real news emphasizes factual narration. This module combines a pretrained language model with a feature-mapping layer to derive deep semantic representations and make them dimensionally compatible with structural and temporal features [33,34].

Normalization: To reduce noise, we standardize headlines and bodies. For headlines, remove special symbols (e.g., “#”, “@”) and redundant spaces, and unify character casing where applicable (not needed for Chinese). For bodies, truncate overly long text (keep the first 8192 characters; MAX_LENGTH = 8192), strip meaningless characters (HTML tags, garbled tokens), and preserve complete sentence boundaries.

Encoding. We use Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B for both headline and body, leveraging its strong performance on Chinese–English understanding and support for long contexts. For news item n with headline and body , we obtain two 1024-dimensional embeddings:

Batch processing is adopted for efficiency. If a headline or body is missing, we pad with a zero vector for the corresponding embedding.

Dimensionality alignment and layer normalization: Since the 1024-D text embeddings are much higher-dimensional than the structural (64-D) and temporal (128-D) streams, we linearly project the concatenated text embedding to 64-D and apply LayerNorm:

where (2048 = 1024 + 1024) and are learnable.

Layer normalization is

where , are learnable scale and bias, and avoids division by zero. The output is the news-level text feature.

3.6. Multi-Feature Fusion and Classification

Multi-feature fusion is central to our model: we first perform dimension alignment, then concatenate features, apply nonlinear fusion, and finally conduct classification to tackle mismatched dimensions, unequal importance, and redundancy [21,32]. We choose concatenation followed by a linear transform, which preserves modality-specific information and supports learnable low-order interactions, yielding a strong accuracy–efficiency balance.

- Dimension alignment: All module outputs are mapped to 64-D:

- Graph: (already 64-D).

- Emotion/temporal:

- Text: (from Section 3.5).

- Feature fusion: We then integrate the streams by concatenation followed by a linear layer:

- Classifier: A two-layer MLP with Dropout and LeakyReLU outputs the fake probability:

- Loss with class imbalance: We employ weighted binary cross-entropy:

4. Experiments and Results

Guided by a theory–features–decision causal chain, this section structures the experiments as a tightly knit argument demonstrating the core value of C-STEER. We begin by benchmarking against strong baselines to show that C-STEER achieves state-of-the-art performance (Section 4.2). We then conduct ablation studies to show that its superiority stems from our theory-driven module design (Section 4.3). Next, we provide key validation for the framework’s theoretical cornerstone—life-cycle emotion dynamics (Section 4.4). Finally, we demonstrate that C-STEER is not only theoretically sound but also practically valuable, with strong early-detection capability, cross-platform generalization, and robustness, suggesting high potential for real-world deployment (Section 4.5, Section 4.6 and Section 4.7). Unless otherwise noted, all reported numbers are mean ± standard deviation over five random seeds, with significance testing performed.

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Datasets and Splits

We evaluate on two widely used real-world datasets: Weibo21 and Twitter16. They represent two major linguistic contexts (Chinese vs. English) and differ in social mechanics (e.g., comment/retweet on Weibo vs. quote-tree structures on Twitter) and cultural background. Achieving success on both offers strong evidence for the generality of C-STEER.

- Weibo21: 4488 fake/4640 real; includes headline, body, user interactions (retweet/comment/like), timestamps, and user IDs.

- Twitter16: 205 fake/613 real (total 818 items); includes source tweets, comment trees, timestamps, and user metadata.

We enforce strict event-level deduplication: all posts and their interactions that reference the same underlying news item are grouped as a single event and placed in exactly one split (train, dev, or test) to prevent cross-split leakage. We use a 70/10/20 split (train/dev/test). Reported results are the mean ± standard deviation over five random seeds (42, 2021, 3407, 614, 10,086).

We acknowledge that Weibo21 and Twitter16 are relatively dated compared to the rapidly evolving landscape of modern social media. However, they serve as established benchmarks in the fake news detection community [4,17,23], ensuring fair and direct comparisons with a wide range of baselines. While our model shows robust performance on these standard datasets, future work will extend validation to newer, multilingual, and cross-platform datasets (e.g., MM-COVID, GossipCop) to further test generalization capabilities.

4.1.2. Experimental Settings

Given class imbalance—especially in Twitter16, where fake news is the minority—we prioritize F1-macro as the primary metric, which balances performance across the majority (real) and minority (fake) classes and avoids the misleading conclusions that can arise from accuracy alone. We also report Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-micro, and AUC as auxiliary metrics.

For reliability, we apply the McNemar test. References to “significant differences” indicate p < 0.05; unless otherwise specified, p < 0.01 (p < 0.05 marked with *, p < 0.01 with **).

Optimizer: AdamW; learning rate: 1e-4; batch size: 64; epochs: 30; early stopping: patience = 5 on dev F1-macro. Text encoding: Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B; 1024-D for headline and 1024-D for body, linearly projected to 64-D with LayerNorm. Feature fusion: Text, emotion/temporal, and graph features are each aligned to 64-D, concatenated, and fused linearly. Environment: Ubuntu 22.04, Python 3.10, PyTorch 2.3, CUDA 12.1; single NVIDIA RTX 4090 (24 GB).

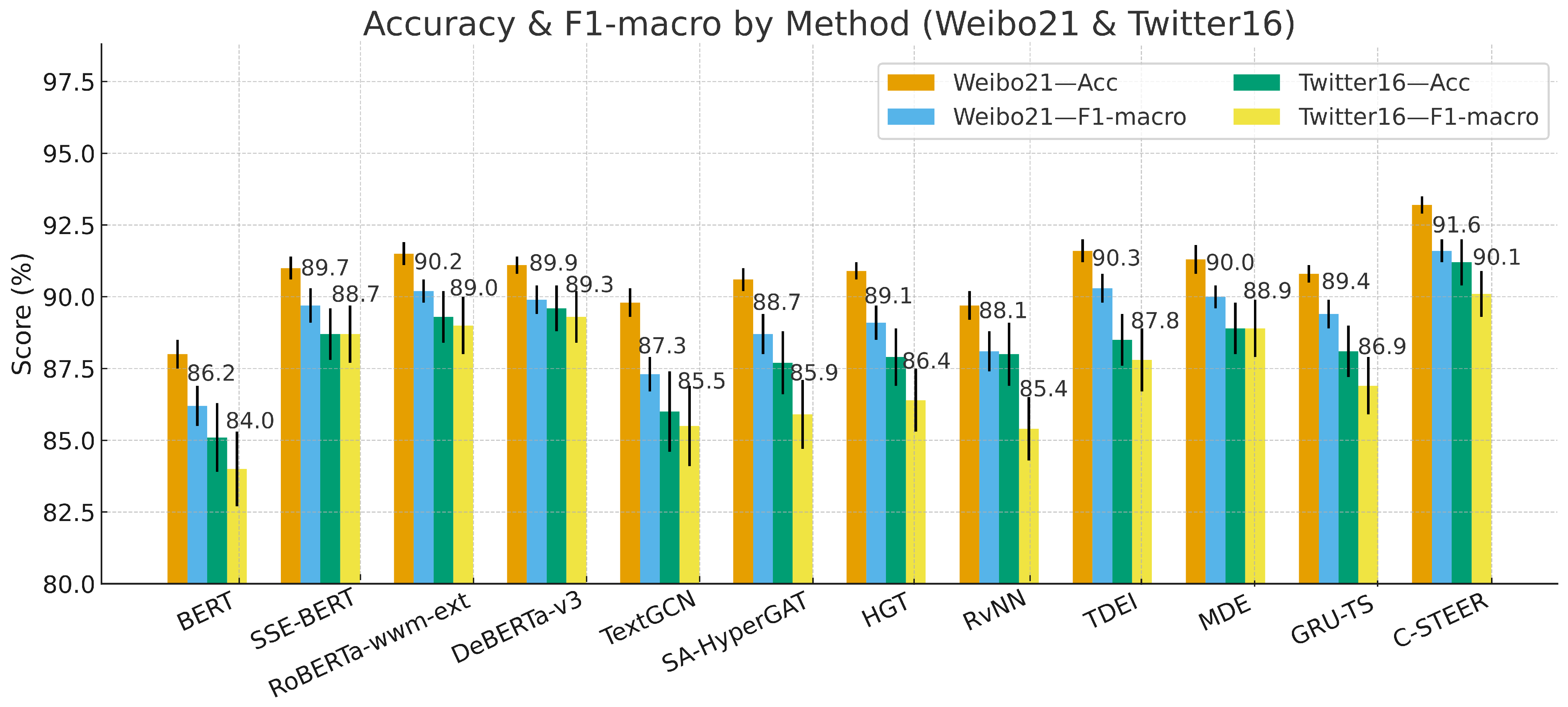

4.2. Baselines and Overall Results

To comprehensively evaluate performance, we select representative baselines spanning text, graph, and temporal perspectives:

- Text-centric baselines: BERT, SSE-BERT, RoBERTa, DeBERTa-v3 [19,33,34];

- Graph-centric baselines: TextGCN, SA-HyperGAT, HGT [8];

- Temporal/affective baselines: RvNN, TDEI, MDE, GRU-TS [17,23,26];

- Our method: C-STEER (text semantics + life-cycle emotions + BiLSTM with attention + lightweight graph).

Table 5.

Overall performance of different methods on Weibo21 (%; mean ± standard deviation).

Table 6.

Overall performance of different methods on Twitter16 (%; mean ± standard deviation).

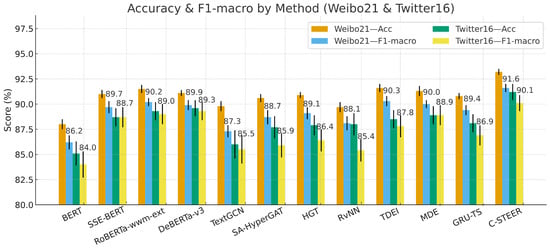

The results clearly show that C-STEER achieves the best F1-macro on both datasets and is significantly better than every next-best model. A deeper look clarifies where the gains come from:

- Versus text-centric baselines: On Weibo21, C-STEER outperforms strong text-centric models such as SSE-BERT (and the text-heavy temporal detector TDEI) with a notable margin (F1-macro: 91.6% vs. 89.7%). This highlights the limitation of relying solely on static semantics: by integrating temporal dynamics and propagation structure, our model captures anomalous diffusion signals that pure-text methods cannot sense [20,26].

- Versus graph-based baselines: Crucially, C-STEER surpasses the advanced graph model SA-HyperGAT, reinforcing our core hypothesis. As argued in the introduction, models like SA-HyperGAT can be confused by viral real breaking news whose propagation graphs resemble those of fake news. By introducing life-cycle-aware emotional dynamics, C-STEER supplies the missing decision axis to disambiguate emotion-driven misinformation from fact-driven hot events, directly remedying a key shortcoming of existing graph approaches [8,9,13], as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Accuracy and macro-F1 comparison of different methods on Weibo21/Twitter16.

Figure 5. Accuracy and macro-F1 comparison of different methods on Weibo21/Twitter16.

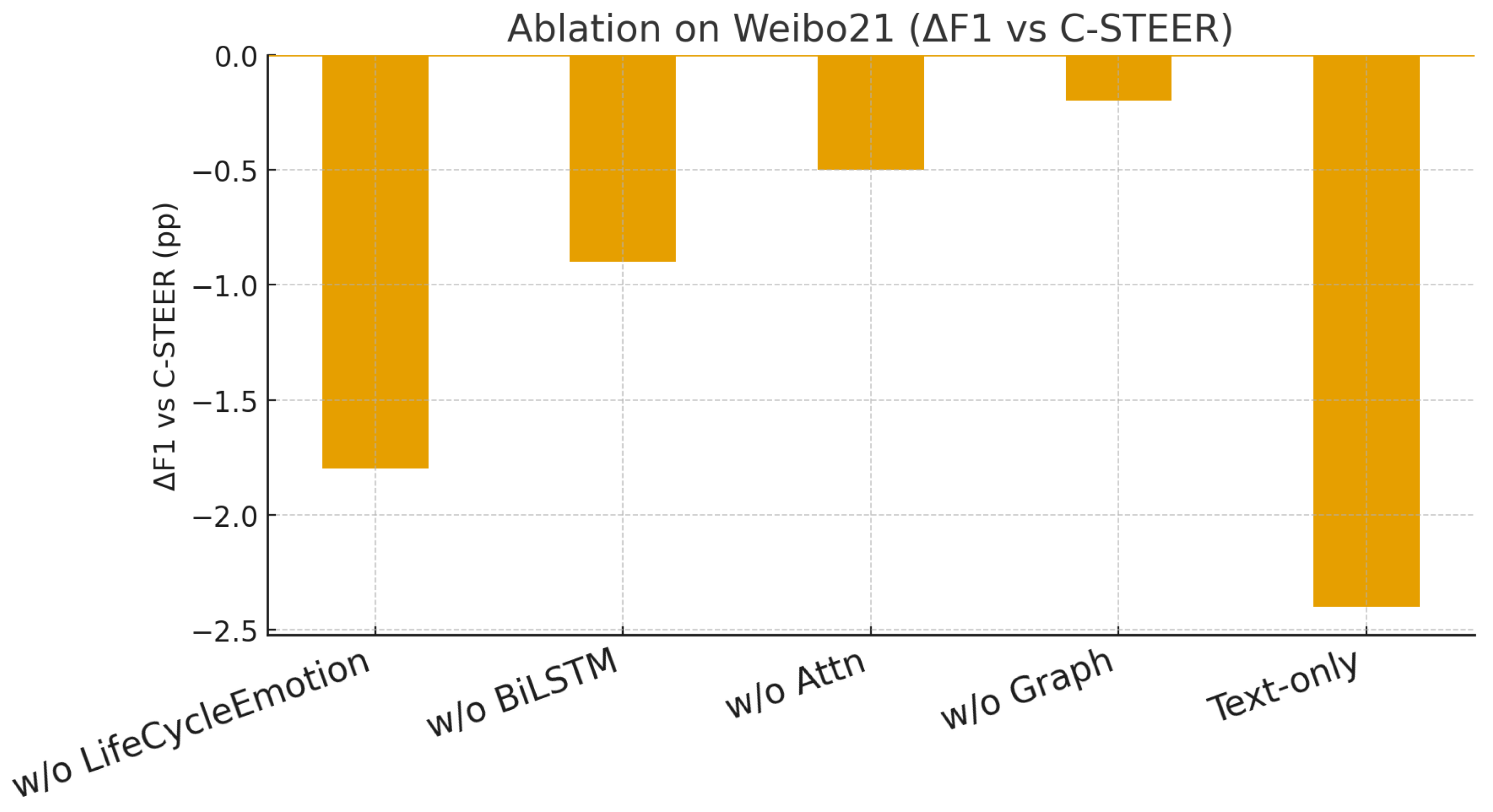

4.3. Ablation Study

To quantify the marginal contribution of each component, we construct six ablated variants on Weibo21 [8,23,28]:

- w/o LifeCycle-Emotion: remove the 13-dimensional stage-wise emotion feature vector (defined in Section 3.4) and use global emotion statistics instead;

- w/o BiLSTM: drop sequence dependence; keep only stage-wise emotion statistics;

- w/o Attn: keep BiLSTM but remove attention (uniform averaging over timesteps);

- w/o Graph: exclude graph features entirely;

- Text-only: keep the text module only.

Table 7.

Ablation study (Weibo21, %; mean ± standard deviation).

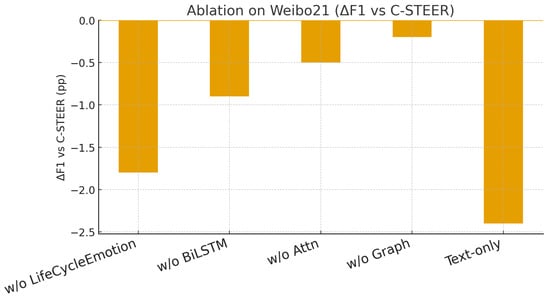

Figure 6.

Ablation on Weibo21 (ΔF1 vs. Full).

Ablation findings: The ablation results not only quantify the contribution of each module but also substantiate our design philosophy.

Primary contributor: life-cycle emotion module. Removing the entire life-cycle emotion component (w/o LifeCycle-Emotion) leads to the largest drop (−1.9 pp in F1-macro), empirically confirming that the communication-theory-driven life-cycle emotion design is the principal driver of success.

Validation of the light-graph design: When excluding graph features (w/o Graph), performance decreases only 0.2 pp, and the gap is not statistically significant. This is not a weakness of the graph branch but a validation of our “emotion-centric, graph-as-auxiliary” philosophy (Section 3.2): the graph offers a stable, complementary relational backdrop for the core emotional and temporal signals without dominating the model, achieving an efficient–effective balance [15,20,28].

Inside the emotion module: A finer-grained look separates stage-wise statistics from temporal dynamics. Keeping the static stage features but removing BiLSTM (w/o BiLSTM) yields a −0.9 pp drop. Further removing the static stage features (i.e., w/o LifeCycle-Emotion) incurs an additional −0.7 pp (1.8 − 0.9 = 0.9). Thus, merely segmenting the life-cycle and extracting stage “emotion portraits” already delivers substantial gains; on top of that, the BiLSTM models within-stage temporal dependencies to amplify their discriminative value [9,22,23,26].

4.4. Validating Life-Cycle Segmentation

To directly test our core hypothesis—that life-cycle-based dynamic emotion analysis outperforms a static, globally aggregated view—we conduct a head-to-head comparison between our LifeCycle-Emotion feature extractor and a strong baseline Global-Emotion (which computes the same emotion statistics over the entire propagation period without staging). As shown in Table 8, the results provide decisive, statistically significant evidence for our theory [9,20,26]:

Table 8.

Life-cycle vs. global sentiment (Weibo21, %).

- Global-Emotion: no stage segmentation; global statistics only;

- LifeCycle-Emotion (ours): stage-wise (initiation/burst/decay) statistics plus a cross-stage dynamic feature [9].

Life-cycle emotions vs. global statistics: Relative to global aggregation, LifeCycle-Emotion improves F1-macro by 1.3 percentage points (p < 0.01). This provides strong evidence that partitioning propagation into initiation–burst–decay enables the model to capture stage-specific emotional signatures aligned with distinct phases of user adoption and interaction—critical dynamics that a global view entirely overlooks [9,20,26].

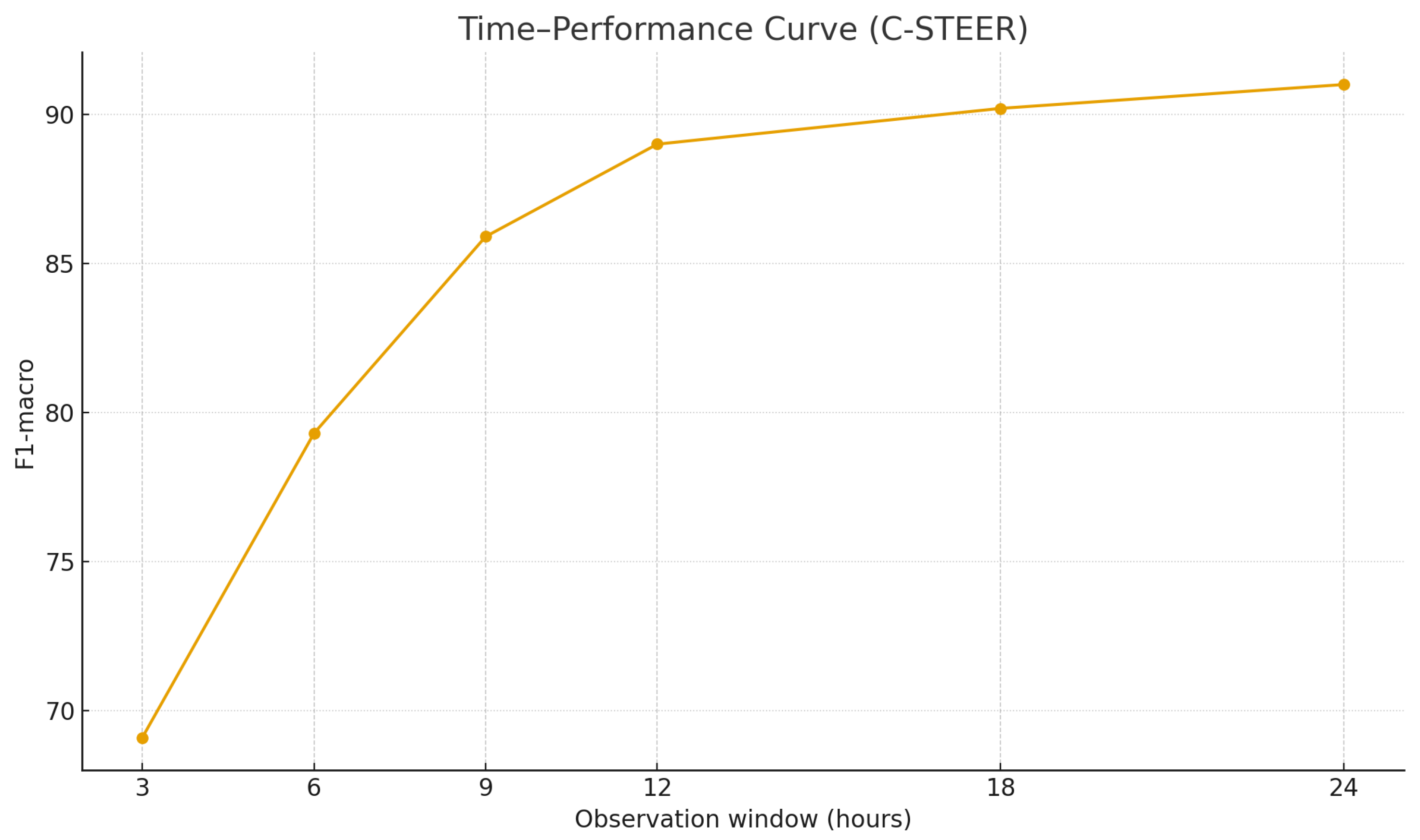

4.5. Early Detection Capability

To assess real-world deployability, we evaluate performance when only early portions of the interaction stream are available [17,19,20,26,37], as summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Early detection performance on Weibo21 (%).

These results indicate that C-STEER maintains competitive accuracy even with partial observations: by 12 h, performance is within 3.2 pp of the full-cycle F1-macro, and by 24 h, the gap narrows to 1.2 pp, underscoring strong early-detection utility.

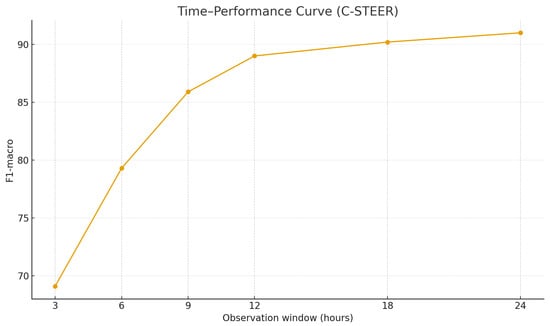

As shown in Figure 7, the time–performance curve saturates rapidly: by 12 h, C-STEER attains 96.5% of the full-cycle F1 (88.4 vs. 91.6), and the marginal gain beyond 16 h is small. This indicates that most discriminative temporal/affective cues emerge early in the diffusion process, supporting practical deployment with short observation windows.

Figure 7.

Time–performance curve of C-STEER on Weibo21. F1-macro versus observation window.

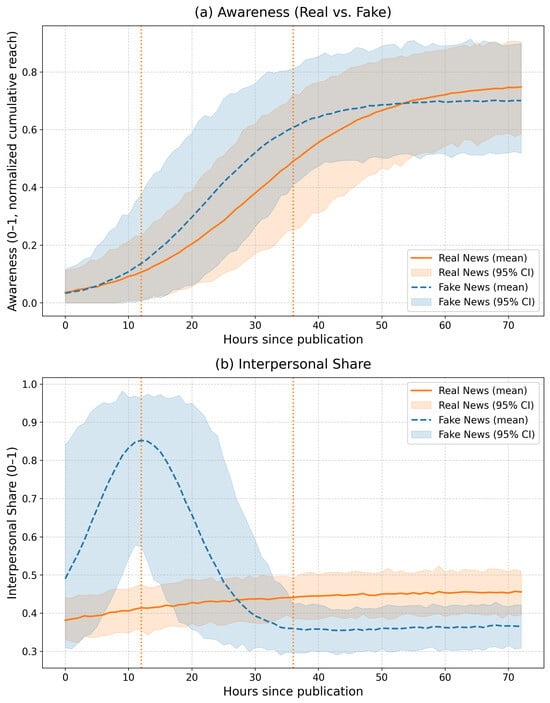

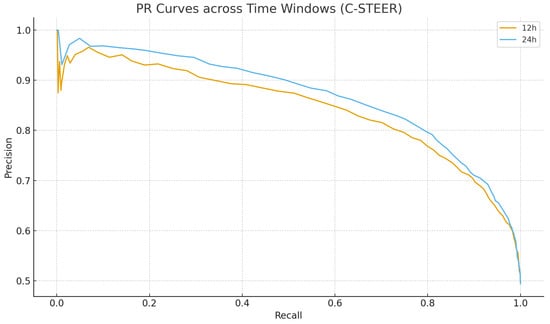

Figure 8 compares Precision–Recall (PR) profiles at 12 h and 24 h. The 24 h curve consistently dominates the 12 h curve, implying fewer false positives at matched recall. For recall-oriented monitoring (e.g., target recall ≈ 0.80–0.90), the 12 h window remains competitive with only a modest precision drop; thus, we first select a target recall per scenario from the PR curve and then set the operating threshold accordingly.

Figure 8.

Precision–Recall curves at 12 h vs. 24 h.

4.6. Cross-Platform Generalization and Robustness

We evaluate generalization by training on Weibo21 and testing on Twitter16 (and vice versa). Results are summarized in Table 10. Training on Weibo21 and transferring to Twitter16 yields F1-macro = 86.4%, a −3.7 pp drop relative to Twitter16 in-domain testing (90.1%). Conversely, training on Twitter16 and transferring to Weibo21 yields F1-macro = 89.6%, a −2.0 pp drop versus Weibo21 in-domain (91.6%) [14,17,38,39,40].

Table 10.

Cross-platform generalization of C-STEER (%).

Module-wise contrasts reveal that emotion–temporal features degrade the least under cross-domain transfer, compared with text and graph features. This suggests that although linguistic style and network topology are platform-specific, the core emotional evolution patterns of human communities facing misinformation are more universal. By grounding itself in communication-theory-guided emotional dynamics, C-STEER achieves strong generalization and is well-positioned for emerging social platforms [9,13,27,38].

4.7. Robustness and Sensitivity Analyses

We further assess stability via hyperparameter sensitivity and noise-injection studies on Weibo21. We vary fusion weights, the leader threshold, and stage-boundary perturbations [8,23,28]. The best configuration is // = 0.4/0.4/0.2 (F1-macro = 91.6%); a Top-10% leader threshold outperforms Top-5% and Top-20% (91.2% and 91.3%); and perturbing stage boundaries by ±10% yields 91.5% and 91.4%, very close to the unperturbed 91.6% (Table 11).

Table 11.

Hyperparameter sensitivity.

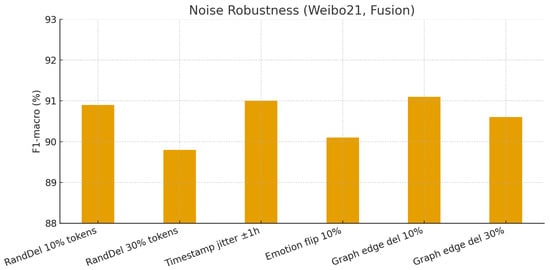

We inject noise by deleting tokens at 10% and 30%, applying timestamp jitter of ±1 h, flipping 10% of emotion labels, and deleting graph edges at 10% and 30% (Table 12).

Table 12.

Noise robustness (F1-macro, %).

As shown in Figure 9, C-STEER is insensitive to mild hyperparameter perturbations (e.g., fusion weights, stage boundaries) and exhibits graceful degradation under text, temporal, affective, and structural noise, demonstrating stability in complex real-world conditions.

Figure 9.

Noise robustness of C-STEER under different perturbations (Weibo21, Fusion).

4.8. Computational Efficiency and Scalability

Unlike large language model (LLM)-based detectors that require massive computational resources for inference, C-STEER is designed to be lightweight. The graph module utilizes a simplified neighbor sampling strategy, and the text encoder projects high-dimensional embeddings into a compact 64-dimensional space. In our experiments (NVIDIA RTX 4090), the average inference time per event for C-STEER is approximately 100 ms, which is significantly faster than LLM-based approaches (often >3 s per query). This efficiency makes C-STEER highly scalable for real-time monitoring of high-throughput social media streams.

4.9. Experimental Summary

Through a series of rigorous studies, we systematically validate the effectiveness of the C-STEER framework.

First, comparisons against strong baselines establish state-of-the-art performance on two real-world datasets—Weibo21 and Twitter16—with F1-macro scores of 91.6% and 90.1%, respectively (Section 4.2). Second, comprehensive ablation analyses unpack these gains and empirically confirm that the communication-theory-driven life-cycle emotion module is the primary contributor to the model’s success (Section 4.3) [23,26]. Third, we provide direct evidence for the framework’s theoretical cornerstone, showing that stage-wise emotion analysis across the life-cycle significantly outperforms a traditional global static perspective (Section 4.4) [9,20,26]. Finally, by demonstrating strong early-detection capability, cross-platform generalization, and robustness under noisy data, we show that C-STEER is not only theoretically advanced but also highly deployable in real-world settings (Section 4.5, Section 4.6 and Section 4.7) [19,20,38].

Taken together, these results form a coherent body of evidence that modeling the dynamic, stage-wise evolution of emotions in news propagation is an effective path toward more accurate, interpretable, and robust fake news detection.

4.10. Ethical Considerations

While modeling emotional dynamics enhances detection accuracy, it raises ethical concerns regarding user privacy and potential bias. All data used in this study (Weibo21 and Twitter16) are anonymized public benchmarks. No private user information was crawled or de-anonymized. Furthermore, we acknowledge that emotion detection algorithms may exhibit bias across different cultural or linguistic groups. In real-world deployment, human-in-the-loop auditing is recommended to prevent the misclassification of legitimate emotional expression (e.g., activism) as misinformation.

5. Conclusions

Targeting dynamic social propagation scenarios, we propose C-STEER, guided by Diffusion of Innovations theory, which segments the propagation process into three stages: initiation, burst, and decay. Drawing on Uses and Gratifications and Emotional Contagion theories, we extract stage-specific emotion features and define edge weights. A BiLSTM with attention then learns the temporal dependencies of these emotional signals. Finally, we fuse all signals—stage-wise emotions, a lightweight graph structure, and textual semantics—in a unified feature space for classification. Section 3 details a reusable adaptive life-cycle segmentation (dynamic sliding windows + main-peak detection) and a multi-feature fusion pipeline. Experiments demonstrate the following:

- Time-aware emotion dynamics are the key gain driver. Removing life-cycle emotions or temporal attention yields the most pronounced performance drops, validating the discriminative value of stage differences + temporal dependencies.

- The results confirm the effectiveness of multimodal complementarity. Integrating textual semantics (“what is said”), graph structures (“how it spreads”), and emotional/temporal dynamics (“when and why it fluctuates”) yields a more robust model than any single modality alone [21,37,41].

- Practicality and generalization: With a 12 h early window, performance approaches the full cycle; cross-platform transfer and noise-injection tests show controlled degradation, indicating deployment feasibility [19,26,38].

Theory–module–feature alignment. Diffusion stages, Uses and Gratifications, and Emotional Contagion are grounded in life-cycle segmentation, stage-wise emotion and edge design, and temporal modeling, improving interpretability and transferability [6,10,11]. Stage-wise emotion + temporal attention. We combine static within-stage statistics (mean/variance/negative-share/entropy) with a dynamic cross-stage change rate, and use BiLSTM + attention to capture synchrony and lagged relations [6,23,24,26]. An engineering evaluation paradigm. We provide an adaptive segmentation procedure and a unified fusion implementation, and validate them systematically on Weibo21 and Twitter16 via overall comparisons, ablations, early detection, and cross-domain studies [21].

Limitations and Future Work

Despite the promising results, this study has limitations. First, the reliance on heuristic thresholds for stage segmentation may not fully capture complex propagation patterns, such as multi-peak events or pulse-like bursts. Second, the datasets used (Weibo21 and Twitter16) are relatively dated, potentially limiting the model’s direct applicability to emerging content forms like short videos. In future work, we plan to address these issues by (1) developing learnable segmentation methods and causal models to replace heuristic windows; (2) integrating domain adaptation techniques to handle cross-platform linguistic shifts; and (3) exploring lightweight structural encoding to better capture high-order topological patterns without compromising efficiency.

Overall, C-STEER unifies life-cycle cues, graph-based diffusion structure, and emotion-driven time-series signals in a single detector—enhancing accuracy and robustness while maintaining interpretability and practical deployability—and offers a reusable recipe and evaluation baseline for communication-theory-guided fake news detection [20,21,26].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z.; Methodology, Z.Z.; Software, Z.Z.; Validation, Z.Z.; Formal analysis, Z.Z.; Investigation, Z.Z.; Writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.; Writing—review and editing, Z.Z. and Y.L.; Supervision, Y.L.; Project administration, Y.L.; Funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were used in this study. Weibo21: the benchmark split (train/val/test) is available from the MDFEND-Weibo21 repository (https://github.com/kennqiang/MDFEND-Weibo21, accessed on 22 December 2025); Twitter16: available as part of the RumDetect2017 package (https://www.dropbox.com/s/7ewzdrbelpmrnxu/rumdetect2017.zip?dl=0, accessed on 22 December 2025); a public mirror/processed version is available at https://github.com/gszswork/Twitter15_16_dataset, accessed on 22 December 2025. No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kolev, V.; Weiss, G.; Spanakis, G. FOREAL: RoBERTa Model for Fake News Detection based on Emotions. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2022), Online, 3–5 February 2022; Volume 2, pp. 429–440. [Google Scholar]

- Nassif, A.B.; Elnagar, A.; Elgendy, O.; Afadar, Y. Arabic fake news detection based on deep contextualized embedding models. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 16019–16032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yahya, M.; Al-Khalifa, H.; Al-Baity, H.; AlSaeed, D.; Essam, A. Arabic Fake News Detection: Comparative Study of Neural Networks and Transformer-Based Approaches. Complexity 2021, 2021, 5516945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Ding, Y.; Qi, S.; Wang, X.; Liao, Q. Multi-depth graph convolutional networks for fake news detection. In CCF International Conference on Natural Language Processing and Chinese Computing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 698–710. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Sun, Y.; Hsu, S.; Li, Y.; Wong, R.C.W. Fake news detection with heterogeneous transformer. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.03100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Rapson, R.L. Emotional Contagion. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1993, 2, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The Strength of Weak Ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Lin, F.; Li, G.; Liu, B. Sentiment-aware fake news detection on social media with hypergraph attention networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Prague, Czech Republic, 9–12 October 2022; pp. 2174–2180. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Yang, K.; Thompson, P.; Yu, Z.; Ananiadou, S. Emotion detection for misinformation: A review. Inf. Fusion 2024, 107, 102300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M.; Singhal, A.; Quinlan, M.M. Diffusion of Innovations. In An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 432–448. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, E. Utilization of mass communication by the individual. In The Uses of Mass Communications: Current Perspectives on Gratifications Research; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1974; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.; Hong, D. Emotional contagion: Research on the influencing factors of social media users’ negative emotional communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 931835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Song, W.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, T.; Chiang, Y.C. Emotional contagion on social media and the simulation of intervention strategies after a disaster event: A modeling study. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Nawi, H.M.; Naeem, S.B. The uses and gratifications (U&G) model for understanding fake news sharing behavior on social media. J. Acad. Libr. 2024, 50, 102938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, X.; Wu, J.; Yang, J.; Fan, H. Heterogeneous Subgraph Transformer for Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024 (WWW ’24), Singapore, 13–17 May 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xu, W.; Liu, Q.; Wu, S.; Wang, L. Adversarial contrastive learning for evidence-aware fake news detection with graph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 36, 5591–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Gao, W.; Wong, K.F. Rumor Detection on Twitter with Tree-Structured Recursive Neural Networks; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, K.; Kobti, Z. Debertnext: A multimodal fake news detection framework. In International Conference on Computational Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 348–356. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, X.; Rao, D.; Jiang, Z. Syntax and sentiment enhanced bert for earliest rumor detection. In CCF International Conference on Natural Language Processing and Chinese Computing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 570–582. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.; Wu, B.; Xiang, A.; Zhu, Y.; Song, C. DGTR: Dynamic graph transformer for rumor detection. Front. Res. Metrics Anal. 2023, 7, 1055348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdali, S.; Shaham, S.; Krishnamachari, B. Multi-modal misinformation detection: Approaches, challenges and opportunities. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 57, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luvembe, A.M.; Li, W.; Li, S.; Liu, F.; Xu, G. Dual emotion based fake news detection: A deep attention-weight update approach. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cao, J.; Li, X.; Sheng, Q.; Zhong, L.; Shu, K. Mining dual emotion for fake news detection. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021 (WWW ’21), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3465–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padalko, H.; Chomko, V.; Chumachenko, D. A novel approach to fake news classification using LSTM-based deep learning models. Front. Big Data 2024, 6, 1320800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amer, E.; Kwak, K.S.; El-Sappagh, S. Context-based fake news detection model relying on deep learning models. Electronics 2022, 11, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhou, B.; Tu, H.; Liu, Y. Rumor detection on social media using temporal dynamic structure and emotional information. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Sixth International Conference on Data Science in Cyberspace (DSC), Shenzhen, China, 9–11 October 2021; pp. 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, B.E. Emotion, Digital Media, and Misinformation. In Emotions in the Digital World: Exploring Affective Experience and Expression in Online Interactions; Nabi, R.L., Myrick, J.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 422–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Gao, C.; Yin, Z.; Li, X.; Kurths, J. Propagation structure-aware graph transformer for robust and interpretable fake news detection. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 August 2024; pp. 4652–4663. [Google Scholar]

- Farhoudinia, B.; Ozturkcan, S.; Kasap, N. Emotions unveiled: Detecting COVID-19 fake news on social media. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanos, N.; Leonidou, P.; Laoutaris, N.; Sirivianos, M.; Aspri, M.; Paraschiv, M. HyperGraphDis: Leveraging hypergraphs for contextual and social-based disinformation detection. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 2024, 18, 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Sinnott, R.O.; Qi, J.; Paris, C. Fake news detection through graph-based neural networks: A survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.12639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, M.; Arshad, N.I.; Ali, A.; Alhussian, H.; Saeed, F.; Da’u, A.; Nafea, I. A systematic review of multimodal fake news detection on social media using deep learning models. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.; Gao, J.; Chen, W. Debertav3: Improving deberta using electra-style pre-training with gradient-disentangled embedding sharing. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.09543. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhao, J.; Sano, Y.; Levy, O.; Takayasu, H.; Takayasu, M.; Li, D.; Wu, J.; Havlin, S. Fake news propagates differently from real news even at early stages of spreading. EPJ Data Sci. 2020, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Matter, D.; Jaidka, K.; Varol, O.; Mashhadi, A.; Lasser, J.; Assenmacher, D.; Wu, S.; Yang, D.; Brantner, C.; et al. Just another day on Twitter: A complete 24 hours of Twitter data. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 2023, 17, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Liao, Q.; Zhou, B. A multi-modal prompt learning framework for early detection of fake news. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 2024, 18, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, J.; Wu, S.; Wang, L. Out-of-distribution evidence-aware fake news detection via dual adversarial debiasing. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 6801–6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfänder, J.; Altay, S. Spotting false news and doubting true news: A systematic review and meta-analysis of news judgements. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2025, 9, 688–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quelle, D.; Cheng, C.Y.; Bovet, A.; Hale, S.A. Lost in translation: Using global fact-checks to measure multilingual misinformation prevalence, spread, and evolution. EPJ Data Sci. 2025, 14, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Huang, M.; Hu, Z.; Cai, S.; Zhou, T. Multimodal Fake News Detection with Contrastive Learning and Optimal Transport. Front. Comput. Sci. 2024, 6, 1473457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.