Abstract

The excessive and inappropriate use of the internet by children and young people increases their exposure to risky situations, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. This study analyzes risky situations on social media among children and adolescents. The objective of this work was to identify the risks associated with the use of social media. A comparative analysis of five clustering algorithms was applied to a dataset developed by eBiz Latin America in collaboration with La Salle University of Arequipa and the Institute of Christian Schools of the De La Salle Brothers of the Bolivia-Peru district. Among the results, it was shown that children around 11 years old display a high prevalence of digital risk behaviors such as adding strangers, followed by pretending to be someone else; adults around 43 years old exhibit a tendency to follow strangers and, even more so, to take photographs without permission; adolescents with an average age of 11 show a heavy use of YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram. It is concluded that among digital risks in children and adults, the clusters highlight shared vulnerabilities, such as the addition of strangers and exposure to requests for personal data, which persist throughout the life stages but intensify in early adulthood. These findings emphasize the urgency of preventive policies addressing generational differences in social network use to promote proactive responses to digital harassment.

1. Introduction

Social media use among children and adolescents is becoming increasingly common, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. This excessive increase and inappropriate internet use by young people increases their exposure to risky situations. Analyzing these risks from multiple perspectives is vitally important to propose different solutions. In addition to risk, there are other consequences, such as decreased academic performance and an increase in psychological/emotional problems such as depression, anxiety, or stress [1].

Secondary school students primarily use social media platforms like Twitter, TikTok, Telegram, and Discord in various communities of interest. In these communities, most users upload self-produced material. This results in a significant amount of information being produced and consumed. Regulation is only possible if schools and families collaborate to monitor access to this digital content. Some social media platforms can contribute to student learning; however, the content consumed influences this process [2].

Among users aged 10 to 19, Instagram, WhatsApp, YouTube, and Facebook are the most frequently used social media platforms. New friendships are made on these social networks; however, they are exposed to certain risks due to sharing their personal data. These opportunities for privacy invasions have led to cyberbullying, distorted photos, threats, offensive messages, and the receipt of inappropriate content. These adolescents reported feeling primarily embarrassed and, at times, experiencing negative consequences for their mental health. This study was conducted in Brazil, and its results are consistent with the Brazilian Media Survey, confirming that adolescents use the internet seven days a week [3].

In Ecuador, young people between the ages of 15 and 24 use social media between 3 and 4 h a day, extending up to 14 h [4]. This behavior is evident and often demanded by schools themselves. The authors explore socialization to mitigate the risks to which elementary and secondary school students are exposed. These discussions should address responsibilities regarding privacy protection and the security of personal data. Specific settings must be implemented and available on these social media platforms to address these risks [5,6].

Children and adolescents are using social media excessively, especially since the pandemic. This situation exposes them to various risks, resulting in diverse consequences. Online platforms can be helpful in learning, but appropriate use and/or supervision are necessary, both in schools and within families. Above all, socialization with parents and children should be encouraged through educational talks about privacy protection and appropriate use. Much can be achieved if families, schools, the government, and the media work together. Therefore, all the studies conducted contribute enormously to establishing strategies and actions to protect children and adolescents from the risks they face when online [7].

From a Latin American regional perspective, previous studies have documented high levels of online risk among adolescents in cyberbullying, sexting, and exposure to inappropriate content and have highlighted gender and cultural variations in the perception and management of these risks. In Latin America, research with teachers and adolescents from countries such as Peru, Chile, Argentina, Colombia, and Ecuador has identified links between online harassment and reduced well-being, underscoring that the digital risk environment transcends national borders [8].

Therefore, the clustering method applied to the Peruvian youth context allows for comparison with regional patterns and the identification of subgroups, such as urban/rural location or device usage. Given the high access to mobile phones, variable parental mediation, and socioeconomic diversity in Peru, this study offers an opportunity to connect data-driven segmentation with the design of relevant public policy interventions. In summary, this research is situated at the intersection of rigorous computational techniques and the socially rooted understanding of risk perception in Latin American youth digital culture [9].

In the Peruvian context, the growing internet access and social media use among young people demand detailed studies on how children and adolescents perceive and respond to risks in digital environments. For example, the study in [10] found that the expansion of internet access in Peruvian homes had significant impacts on child development, demonstrating the rapid growth of digital connectivity in the country and thus providing fertile ground for examining risk perception on social media. The fact that Peruvian children are increasingly participating in online activities implies that their understanding of risks is likely conditioned by their sociocultural and technological environment. A cluster-based approach to identifying risk perception among Peruvian youth fills a fundamental gap by aligning methodological innovation with Peru’s unique trajectory of digital adoption [11]. In this way, the study allows for the generation of locally relevant perspectives that may differ from those of other countries, given Peru’s specific characteristics regarding connectivity, education, and media consumption. Furthermore, the study’s relevance is reinforced by evidence linking intensive internet use to adverse mental health consequences for adolescents in Peru. It is reported that adolescents in one Peruvian region with higher levels of internet addiction exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of anxiety, highlighting that online behaviors are not only widespread but can also be potentially harmful in the Peruvian context [12].

In recent years, the role of artificial intelligence applied to specific types of information and contexts has gained significant importance. The applications are highly diverse, and the analyzed information is presented in various formats. These range from the use of neural networks for classification and prediction, which would allow the identification of groups for decision-making [13], to the use of clustering algorithms to obtain real-time behavioral data on social networks, which would allow timely solutions to different situations on these platforms with significant user activity [14].

This research analyzes the perception of risk situations related to social media use among children and adolescents in school. Several unsupervised machine learning clustering models are used for this purpose. The structure of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 comprehensively reviews previous studies on digital risk perception and social media behavior among adolescents. Section 3 details the materials and methods employed in this research, encompassing the theoretical background (Section 3.1), tools and technologies (Section 3.2), dataset description (Section 3.3), and the proposed methodology for the analysis of risk perception in social networks (Section 3.4). Section 4 presents the experimental results obtained from the clustering models, followed by Section 5, which offers an in-depth discussion and interpretation of the findings. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the main conclusions derived from this study, and Section 7 outlines this study’s limitations and future research directions.

2. Related Works

In 2025, a study on excessive social media use was conducted among 7184 adolescents from two Chinese cities. The study links smartphone use and problematic online behaviors. POBs include excessive use of smartphones, video games, and social media. The study was cross-sectional and used validated psychometric tools. Network analysis was applied to assess symptom associations for each of the POBs. The symptoms found were escapism, withdrawal, and loss of control. The results are significant for psychologists, clinicians, and policymakers to address these mental health problems in this digital age [15].

Another study analyzed the values and countervalues perceived by adolescents when interacting on the social media platforms YouTube and Instagram. Fourteen focus groups were used in three communities in Spain. Content was analyzed using the software ATLAS.TI v25. The most perceived value was friendship for women, while fun was present for men. The countervalue present in all groups and for both genders is disrespect for human rights. The gender difference focuses on the values of prestige over image for women and achievement and success for men. Similarities between the two genders include play/recreation, education/knowledge, and friendship/relevance; for countervalues, they are rights/respect and control/order/discipline [16].

In 2024, a study identified characteristics and patterns within 674 labeled private messages on the social media platform Instagram, intending to investigate risk. In this context of anonymity, hurtful opinions affecting the person involved were found. Five types of media content were analyzed: memes, screenshots, images of natural people, natural images of objects, and artistic illustrations. The question was whether comments on the content represented a risk or could be considered humorous. This work allowed for an extensive analysis of the conversations, separating acceptable interactions from those that harm users. Risk is highly subjective, especially in private interactions, but understanding risks on social media is vital [17].

In 2023, another study analyzed the risk of 15,547 private messages on the social media platform Instagram from adolescents aged 13 to 21. To do so, a machine learning approach was used to create risk-detection classifiers. The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model and the random forest performed best for risk identification. An innovative framework was generated to apply artificial intelligence to online interactions. A total of 44,099 messages from participants were about unsafe sexual conversations. These conversations contained negative emotions such as anger and profanity that made the participant uncomfortable or insecure [18].

In 2022, another study applied correlations and meta-regression models using the R language and the robumeta package, analyzing the impact of social media on psychological well-being. For this purpose, they compiled empirical publications from up to twelve years that examined information on social media use and psychological well-being. The relationship between social media use and six dimensions of psychological well-being was quantified through a meta-analysis of 226 empirical studies. They used a random-effects model that calculates the effect size between social media use and well-being. Small positive associations were found with anxiety, depression, and social well-being. The authors conclude that there is a trade-off between the increase in depression and anxiety and the improvement in social well-being associated with social media use [19].

Another study conducted in 2022 proposed a feature extraction method that used a clustering algorithm. Social media behavioral feature extraction was performed on university students in the sports field to obtain real-time social behavior data. Processing was quantitative and standardized for data formatting, removal of abnormal data, error correction, and elimination of duplicate data. Weights were used for feature extraction on both words and sentences. Friendship relationships and the degree of similarity between users were used for the experimental process. The work had high application value in recognizing the behavior of university students on their social networks [14].

In 2021, an exploratory and descriptive quantitative study was conducted with 560 parents of school-aged children between the ages of 6 and 17. The information collected included information about the use of social media, the internet, and the risk of online bullying. Ninety-seven percent of participants took the research seriously, and 50% were unfamiliar with “online grooming.” Eighty-nine percent of respondents did not know where to report cybercrimes. Awareness was raised about the risks of internet use, mainly social media use. Finally, the study encourages reflection among parents, teachers, and adolescents on detecting and responding to risky situations [20].

In 2020, another study collected data from Instagram’s social media platform to analyze risk perception among adolescents aged 13 to 17. They used semi-structured interviews with 10 students beginning their university studies to consider sensitivity in data collection. They used a methodology that combines machine learning techniques to analyze social media interactions with guided discussions between adolescents and parents about identified risk situations. This helped balance the tensions between parents and children when discussing sensitive social media messages. This work promotes adolescent-centered solutions for online safety [21].

In 2017, a literature review categorized the risks affecting the orphan population. This analysis examined the online activity of adolescents in foster care who engage in risky behaviors. The work was conducted by professionals dedicated to designing technology that improves child well-being, establishing the need for online safety systems through parental mediation. However, it is commonplace that this population of adolescents in orphanages is often not considered in risk protection plans. Therefore, this article motivates other researchers to propose social media solutions for protecting these young people in risk situations [22].

In 2016, online personal diaries were promoted to 68 adolescents, who spent two months reflecting on their weekly experiences. They reported 207 risk events, including data breaches, online harassment, sexual solicitation, and exposure to explicit content. A qualitative structural analysis was conducted with the collected data, characterizing risk dimensions such as severity and level. Ways were found to empower adolescents to protect themselves in risky situations. The need for parents and adolescents to discuss all risk situations on social media was reinforced [23].

Overall, the reviewed studies highlight that risk perception among adolescents on social media is a multidimensional phenomenon that cannot be understood through a single disciplinary lens. While psychological approaches shed light on emotional responses and coping mechanisms, computational techniques provide scalable ways to detect and classify risk patterns. The integration of these perspectives allows for a more holistic understanding of digital interactions, especially among vulnerable youth. However, many of these studies remain limited by cross-sectional designs and reliance on self-reported data, which constrain causal interpretations. Future research should therefore adopt longitudinal and mixed-method approaches to capture the evolving dynamics of online risk perception. Furthermore, interdisciplinary collaboration between psychologists, data scientists, and educators remains essential to translate these findings into effective digital safety policies.

In summary, the literature demonstrates clear progress toward identifying and mitigating online risks, yet the gap between detection and prevention persists. Technological tools such as machine learning classifiers or network analyses offer promise but must be complemented by ethical and educational frameworks. Adolescent voices should also be incorporated more actively to ensure that interventions align with their lived experiences and cultural contexts. Importantly, the findings emphasize that risk on social media is not only a matter of exposure but also of interpretation and agency. Recognizing adolescents as active participants rather than passive victims reshapes the narrative around digital safety. This critical shift can guide future research and policy toward more inclusive and adaptive strategies for safeguarding young people online.

3. Materials and Methods

This section presents the materials and methods used in the research. First, it presents the theoretical framework that supports the study’s central concepts, including risk situations, social networks, and unsupervised machine learning techniques. It then describes the tools and technologies used to implement the clustering algorithms. The dataset used is then detailed, highlighting its characteristics and statistical specifics. Finally, it explains the research method, specifying the phases and steps applied to analyze the perception of risk situations on social networks.

3.1. Theoretical Background

This subsection presents the essential concepts underlying this research. First, risk situations and their manifestations in the digital environment are defined. Then, the main risks associated with social media use for children and adolescents are described. The most commonly used platforms and their specificities are also detailed, considering their impact on young people’s daily lives. The fundamentals of machine learning and unsupervised learning are then introduced. Finally, this study’s clustering concepts and main algorithms are reviewed. This conceptual foundation allows us to articulate the research problem with the techniques used in data analysis.

Risk situations can compromise a person’s physical, emotional, or psychological safety. In the case of children and adolescents, these situations have a greater impact due to their developmental stage and the influence of their social environment. Recent studies highlight factors such as isolation, exposure to negative emotions, and unstable family environments as triggers of risks in using digital media [24]. These factors increase vulnerability to victimization and deterioration of emotional well-being. The literature emphasizes that these risks should be understood as multifactorial processes rather than isolated events. Recognizing this complexity is essential for designing prevention and psychological support measures.

Social media risk situations are those threats derived from digital interaction platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, or YouTube. These include cyberbullying, exposure to harmful content, grooming, and sextortion. Scientific evidence has shown that such risks affect both the mental health and general well-being of adolescents and young people [25]. The characteristics of social media, such as the immediacy of communication and anonymity, exacerbate these threats. Furthermore, the perception of digital security is often low, increasing younger users’ vulnerability. The need for educational strategies and parental supervision to reduce these risks has been highlighted [26].

Social media is the digital space where children and adolescents interact most frequently. Platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, and WhatsApp stand out for their widespread penetration into young people’s daily lives. Furthermore, there is a growing use of interactive environments such as Roblox, which combines gaming and socializing dynamics, as well as messaging apps and communities such as Discord and Snapchat. Recent research indicates that intensive use of these platforms can be associated with psychological risks such as depression, anxiety, and changes in self-esteem [3].

The visual appeal, real-time interaction, and immersive dynamics encourage constant and prolonged exposure. This situation increases the likelihood of facing negative experiences such as cyberbullying, grooming, or overexposure of personal data. Understanding the specific role of each network allows for preventive strategies tailored to the dynamics of adolescent use [27].

The use of social media by children and adolescents entails specific risks that have been widely documented. These include cyberbullying, grooming, loss of privacy, digital addiction, and exposure to harmful content. Studies indicate that risk perception in this group is often limited, making it difficult to identify threats and increasing exposure [28]. The literature shows that this lack of perception increases the likelihood of negative consequences for mental health and academic and social well-being. Research in contexts in the Global South highlights that such risks are intensified in environments with lower digital literacy and social inequalities [9]. Therefore, it is essential to consider contextual and cultural factors when analyzing the vulnerability of minors on social media.

Machine learning is the set of techniques that allow machines to learn patterns from data without being explicitly programmed for each task. These techniques are applied to model relationships, predict behaviors, and segment populations in social and public health studies. Applied research emphasizes the need to select algorithms and metrics that respond to the nature of the data and the study’s objectives. Furthermore, reproducibility and transparency of the process are considered current best practices [29]. Recent literature summarizes advances and challenges in applying ML to complex and large data. Therefore, its incorporation into studies on risk perception in social media is justified by its ability to discover non-obvious typologies and patterns [30].

Unsupervised learning encompasses techniques that search for structures in unlabeled data. These techniques are helpful when the target variable is undefined or when exploring heterogeneity in the population is desired. Their applications include subgroup detection, identification of emerging patterns, and dimensionality reduction prior to exploratory analyses [31]. The choice of technique depends on assumptions about density, cluster shape, and the type of variables (numerical, categorical, mixed). Validation in unsupervised learning requires multiple internal indices and qualitative assessment of interpretability. Recent reviews offer practical guidelines for selecting and combining methods for applied problems [32].

Clustering is grouping similar observations into coherent sets without using prior labels. Its primary objective is to reveal typologies or natural segments in the data that facilitate interpretation and decision-making. There are different methodological families—partitional, hierarchical, density-based, and graph-based—each with advantages and limitations depending on the data type [33]. Evaluating results requires compactness/separation indices, stability analysis, and special attention to interpretability. In social applications, clustering allows subgroups with differential perceptions or behaviors to be profiled. Therefore, this study adopts a comparative approach across several algorithms to ensure interpretive robustness [34]. The clustering algorithms used in this research are described below.

K-Means (KM) is a partitional clustering method that iteratively assigns observations to k centroids. Its strength lies in its computational simplicity and interpretability. However, it requires specifying k a priori and is sensitive to the initialization and scale of the variables. The algorithm works well when clusters are approximately spherical and of similar size. In practice, robust initializations (e.g., k-means++) and validation using internal indices and stability analysis are recommended. A review and recent work discuss variants and improvements for large and noisy data [35,36].

The Affinity Propagation (AP) clustering algorithm clusters data using a peer-to-peer message exchange scheme that identifies representative examples. It does not require an explicit fix for the number of clusters; instead, it relies on a preference parameter that influences the number of examples selected. The method can detect clusters of varying shapes and sizes, but its computational cost and sensitivity to the preference parameter are practical limitations. In modern applications, variants have been proposed that automate preference selection and improve scalability. For these reasons, Affinity Propagation is useful when extracting representative elements without imposing a fixed k [37,38].

Mean Shift (MS) is a nonparametric algorithm based on density gradient estimation that converges to local modes of the distribution. It does not require specifying the number of clusters, but rather a window parameter (bandwidth) that controls the sensitivity to local density. It is robust to nonconvex cluster shapes and can separate multimodal structures, although its performance critically depends on the choice of bandwidth. In high-dimensional or noisy data scenarios, it can be computationally expensive and require acceleration techniques. Recent studies review its use for modal clustering and recommend automatic bandwidth selection procedures [39,40].

The Spectral clustering (SC) algorithm transforms data into a similarity graph and performs partitioning in the spectral space derived from the Laplacian. It is particularly effective at detecting nonconvex clusters and complex connected structures that other algorithms fail to separate adequately. However, its performance depends on constructing the similarity graph and selecting parameters (e.g., kernel and number of neighbors). Furthermore, scalability is challenging for large data sets, which has motivated developments in graph structure learning and anchor approximations. Recent literature offers guidelines for choosing the graph construction and optimizing the procedure for realistic data [41,42].

Hierarchical clustering (HC) constructs a hierarchy of clusters by successively merging observations or groups. It does not require an initial fix for the number of clusters and produces a dendrogram that facilitates multi-scale interpretation. Its disadvantage is the computational cost for large samples and its dependence on the linkage criterion and the similarity measure. It is frequently used as an exploratory tool to identify candidate partitions and to be combined with validation measures. Recent work describes scalable variants and hybrid techniques that mitigate its cost in large datasets [43,44]. Some metrics used to evaluate clustering algorithms are described below.

The Silhouette Index (SI) assesses clusters’ internal cohesion and external separation, assigning a value between −1 and +1, with values close to 1 indicating well-defined groups. Its use has become widespread in validating clusterization results due to its intuitive interpretation and availability in standard libraries [45]. The metric does not require prior knowledge of the number of clusters and allows different configurations to be compared objectively. However, it can be sensitive to imbalances in cluster size and nonconvex shapes, which requires caution in its interpretation [46]. Its graphical representation makes it easy to detect poorly grouped points and adjust the optimal number of clusters.

The Calinski–Harabasz Index (CHI) measures clustering quality as the ratio of inter-cluster variance to intra-cluster variance, adjusted for the degrees of freedom. High index values indicate coherent and well-separated clusters, making it an efficient and frequently used option in comparative studies [47]. Furthermore, due to its rapid convergence and ease of computation, the index has been shown to be well-suited to automatic cluster selection in evolutionary and optimization methods. Its application is beneficial in large and structured datasets, where a robust evaluation is required without high computational cost [48]. Despite this, in the presence of non-spherical clusters or irregular distributions, it could overestimate the ideal number of clusters, so using it together with other measures is recommended.

The Davies–Bouldin Index (DBI) assesses clustering quality by calculating a ratio of internal dispersion to cluster separation; low values indicate well-constrained clusters. Its main advantage is that it does not assume specific cluster shapes, giving it flexibility in various applications, including those with clusters of heterogeneous sizes and densities [49]. It is commonly used with metrics such as CHI and SI to obtain a more complete view of clustering quality. DBI is especially useful for identifying configurations with high relative separation, but like other internal metrics, it may not reflect the actual structure in noisy or complex-shaped data. Its interpretation is facilitated by considering relative comparisons between different clustering models [50].

3.2. Tools and Technologies

The key technologies used in this study are described below. The primary programming language, which facilitates data manipulation and analysis, is introduced first. The basic libraries that enable efficient processing and data visualization are then presented. Finally, the advanced libraries that automate and optimize modeling processes using machine learning are discussed.

The Python v3.11 programming language has a straightforward syntax and a robust and extensible ecosystem. Its multi-paradigm design and large community make it ideal for research and engineering. Furthermore, it has proven to be the preferred language in data science and machine learning contexts due to its versatility and productivity [51]. Python allows for the integration of numerical processing, visualization, and modeling in a single environment, which reduces code complexity. Its ability to scale to high-performance computing, even with GPUs, makes it suitable for large volumes of data. These characteristics reinforce the choice of implementing clustering techniques in this study.

The NumPy v1.20.3, Pandas v1.3.5, and Matplotlib v3.5.1 libraries are at the core of data processing in Python. NumPy provides efficient array structures for fast numerical operations and interoperability between scientific components [52]. Pandas facilitates structured data manipulation using DataFrames, allowing for data cleansing, transformation, and label-based organization. Matplotlib offers robust visualization tools, enabling the creation of highly customizable static plots in scientific contexts [53]. These libraries allow for adequate data preparation and representation before applying clustering algorithms.

Libraries such as scikit-learn v0.23.2 and PyCaret v2.2.3 are used for modeling and clustering. Scikit-learn offers a wide range of supervised and unsupervised learning algorithms, with a consistent interface and detailed documentation used in multiple disciplines [54]. PyCaret, for its part, allows automating ML workflows, from model cleaning to evaluation, with just a few lines of code [55]. These tools accelerate experimentation, allow rapid algorithm comparisons, and facilitate reproducible and efficient research. In particular, PyCaret facilitates the systematic comparison of different clustering algorithms, fitting well with the study’s comparative approach.

3.3. Dataset

The dataset used in this study comes from an applied research project [56] developed by eBIZ LATIN AMERICA in collaboration with La Salle University of Arequipa and the Institute of Christian Schools of the Brothers of La Salle in the Bolivia-Peru district. This research aimed to understand the perceptions and uses of social media among Peruvian schoolchildren. The data collection included questions related to behaviors, risks, and perceptions regarding the use of social media. This dataset constitutes an empirical basis for analyzing exposure to digital risk situations in children and adolescents. It also offers relevant input for applying clustering algorithms to study risk patterns.

The dataset contains information that allows us to characterize the sociodemographic and educational profile of the participants. The school of origin is included, which makes it possible to differentiate geographic and social contexts. The type of participant is also recorded, distinguishing between teachers and students, which provides a comparative view of perceptions in different roles. For students, variables such as grade level and educational level (elementary or secondary), age, and sex are detailed. These variables constitute the basis for segmenting the data and analyzing specific patterns according to age groups, gender, or educational level. Their inclusion allows us to contextualize exposure and perception of digital risk in relation to key sociodemographic characteristics.

Additionally, dimensions linked to social media use and risk situations are addressed in the data collected in the dataset. One of these variables includes the platforms used, encompassing popular networks such as Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube, as well as less conventional spaces among schoolchildren, such as Discord, PSN, ChatRoulette, and Roblox. Other variables identify behaviors experienced, including interaction with strangers, identity theft, and unauthorized image sharing. Additionally, students’ perceptions of situations considered dangerous are incorporated, such as requests for information, sexual advances, or threats. Finally, the study examines whether participants know which institutions to turn to if faced with these situations, with options ranging from family to official bodies such as the police, the prosecutor’s office, or Hotline 100. These columns provide a comprehensive overview of the relationship between digital use, experiences, and adolescent responses to online risks. Table 1 shows the columns, their descriptions, and possible values.

Table 1.

Description of dataset variables and possible values.

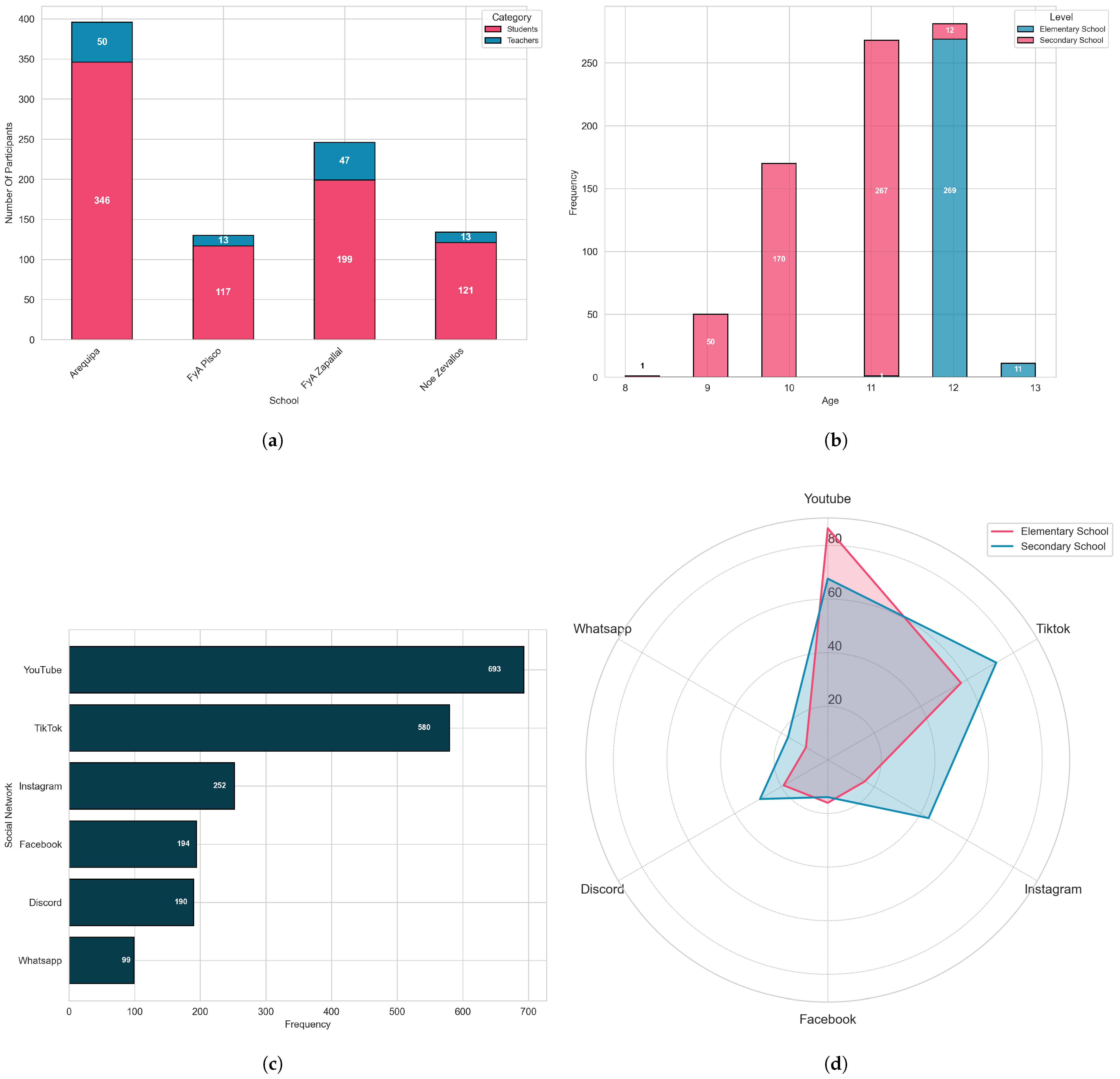

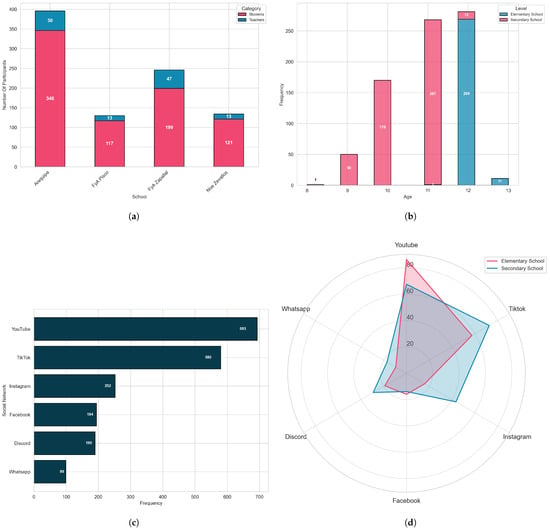

The initial descriptive analysis of the dataset focuses on the sample composition. The database includes 906 participants, of which 781 are students and 125 are teachers. The distribution by school reveals diverse participation among educational institutions in Pisco, Ica, Arequipa, and Lima. Regarding gender, the students are balanced, although there is a slight female majority. The age range of the students varies between elementary and secondary education levels, allowing for generational differences in social media use and perceptions of digital risk to be observed. These elements provide an overview to contextualize subsequent analyses. Regarding social media use, the results show that Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube account for the highest adoption rates among schoolchildren. However, other platforms such as Discord, Roblox, and PSN are also emerging strongly, gaining greater relevance among younger age groups. This finding highlights the diversification of the digital environments in which adolescents interact and provides insight into how the type of social media used can influence exposure to risky situations. Figure 1 show the number of participants by school level and most used social networks.

Figure 1.

Chart showing the number of participants by school level and most used social networks: (a) Number of participants per school (Students and Teachers). (b) Age distribution of students by educational level. (c) Most used social networks by frequency. (d) Most used social networks by educational level.

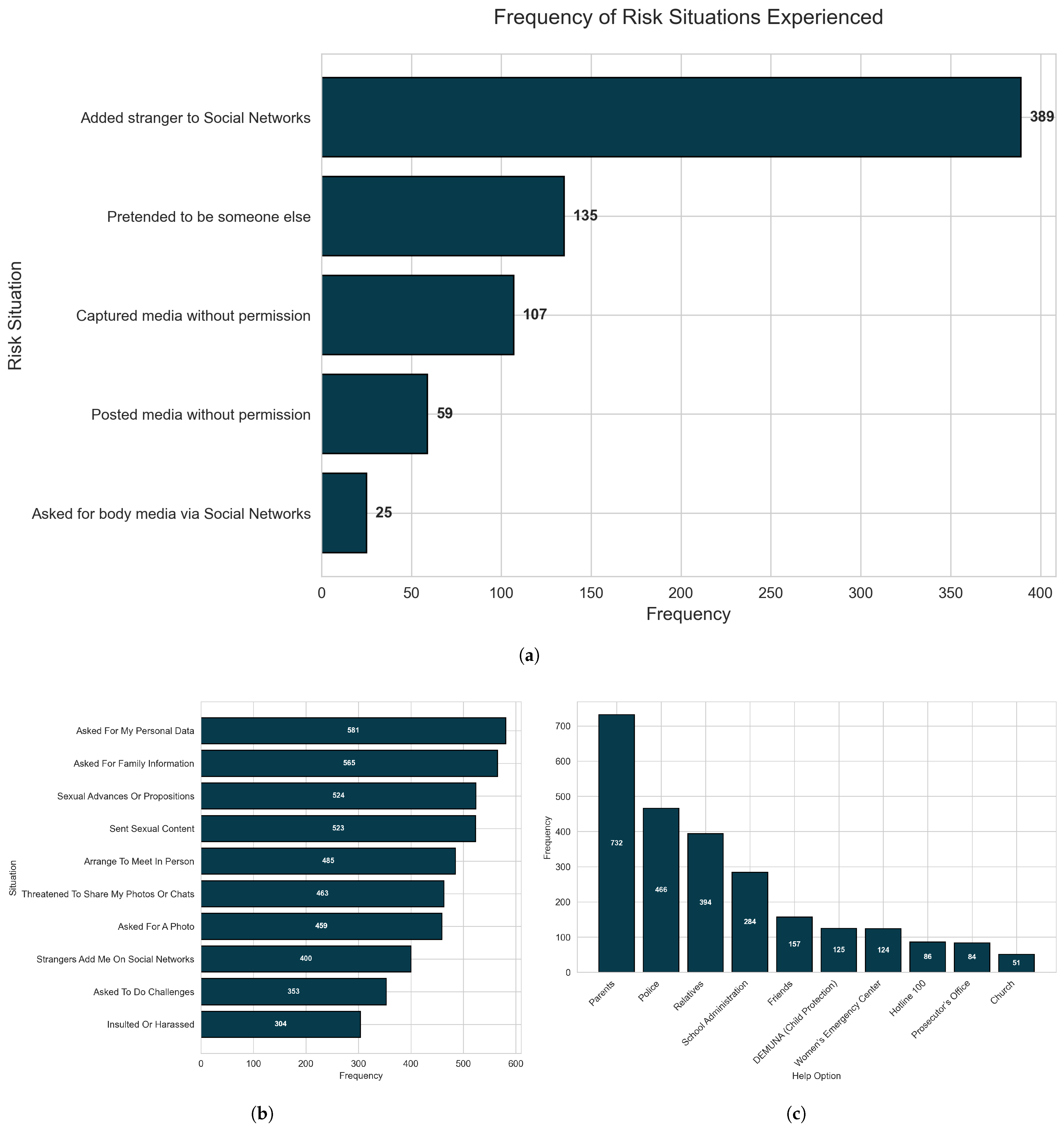

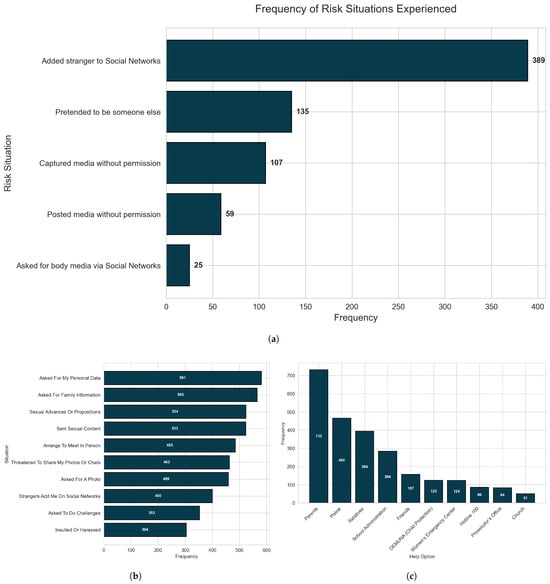

On the other hand, the dataset includes variables associated with the situations experienced, risk perception, and knowledge of support resources. A significant presence of behaviors such as adding strangers, impersonating others, or receiving inappropriate online requests is reported. Risk perception focuses on scenarios related to privacy, digital harassment, and sexual advances. It also identifies whether participants, including parents, family members, teachers, the police, or specialized agencies, know where to go in the event of these situations. These aspects are essential for analyzing adolescents’ vulnerability and coping strategies in the face of digital risks. Figure 2 shows information regarding the situations participants have experienced, their risk perception, and where respondents go.

Figure 2.

Chart showing information regarding the situations participants have experienced, their risk perception, and where respondents go: (a) Frequency of risk situations experienced (all items phrased as “I have…” from the respondent’s perspective; shortened aliases used for readability). (b) Frequency of situations considered dangerous. (c) Frequency of places to get help.

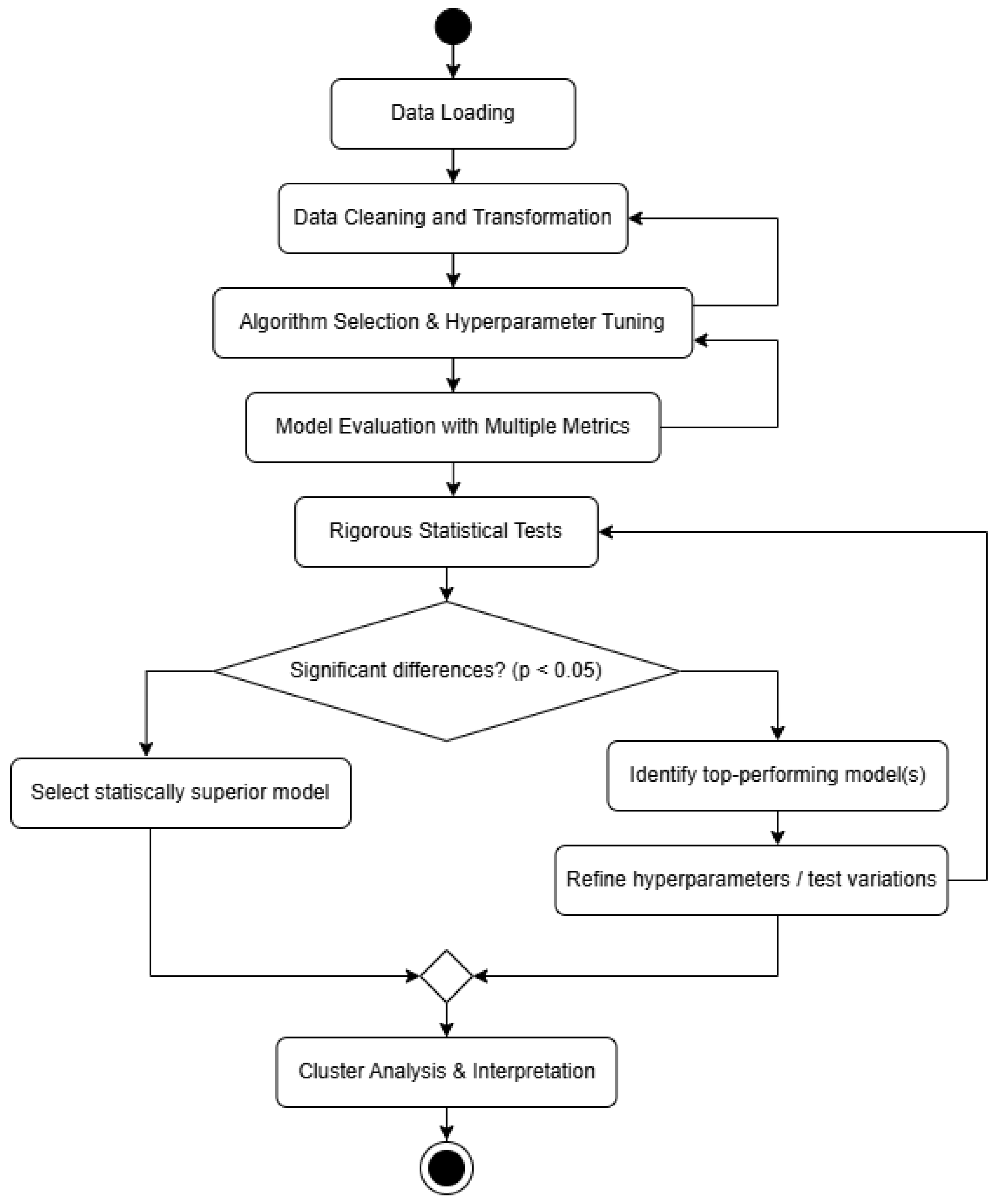

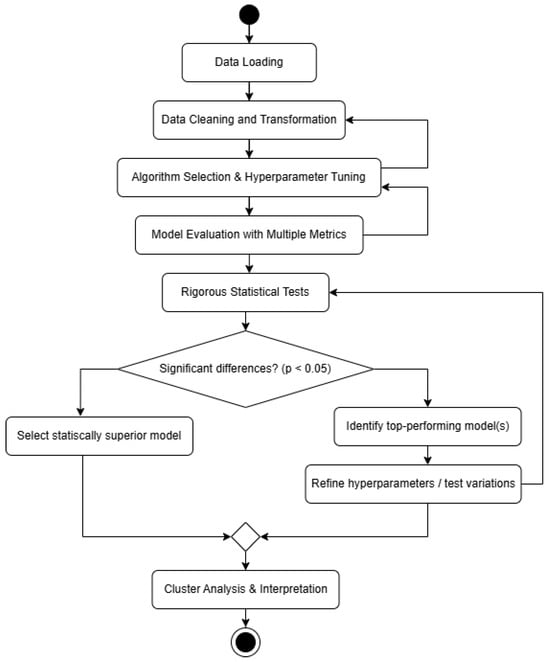

3.4. Proposed Methodology for the Analysis of the Perception of Risk Situations in Social Networks

The proposed methodology consists of six steps, as shown in Figure 3. It begins with loading the raw dataset, followed by a cleaning and transformation phase. To handle missing information on key demographic variables such as age and sex, contextual imputation techniques were applied; age was completed using the mean of the group defined by the participant’s school and grade, while the mode of the same group was used for sex. A crucial step was feature selection, focusing on the most relevant social media platforms. A quantitative filter retained only the platforms used by at least 10% of the respondents, combining data from predefined columns and free text fields. Finally, the data were transformed into a numerical format suitable for modeling: the selected platforms were converted into binary variables (one-hot encoded), and all markers were standardized to ensure dataset consistency.

Figure 3.

Proposed methodology for the analysis of risk perception using clustering.

Once the data were preprocessed, a systematic and exhaustive search for the optimal clustering algorithm was undertaken. To this end, a grid search strategy explored a wide range of algorithms, including K-Means, Affinity Propagation, Mean Shift, Spectral Clustering, and Hierarchical Clustering. Each algorithm was evaluated with multiple combinations of its respective hyperparameters. The performance of each generated model was quantified using a set of three standard metrics for unsupervised clustering: the Silhouette Coefficient, which measures cluster cohesion and separation; the Calinski–Harabasz Index, which assesses the relationship between inter-cluster and intra-cluster dispersion; and the Davies–Bouldin Index, which measures the average similarity between clusters. The results of each experiment were systematically recorded for comparative analysis.

To ensure that the selection of the final model was supported by statistical evidence, a validation phase was implemented. Within this group, the models were ranked according to their performance on the three evaluation metrics. The Davies–Bouldin score was inverted to standardize the ranking, ensuring that a higher score always indicates better performance. The Friedman test was then applied to determine statistically significant differences between the models. When these differences were confirmed (p-value < 0.05), Nemenyi’s post hoc test performed pairwise comparisons. This final step made it possible to precisely identify which model performed significantly better than the others, thus validating its final selection. If no significant differences are found (p-value ≥ 0.05), the process identifies the top-performing model(s) based on the average ranking across metrics and refines them further by conducting additional targeted tests on that specific algorithm—such as expanding its hyperparameter grid, testing variations in the number of clusters, or incorporating hybrid approaches—before reapplying the statistical tests to confirm superiority. Additionally, if a change in algorithm is proposed, a feedback loop returns to the data cleaning and transformation phase to adjust for any new transformations required. If the model evaluation yields very low metrics, another feedback loop adjusts the hyperparameters by returning to the algorithm selection and hyperparameter tuning phase.

4. Results

This section presents the results of evaluating clustering algorithms applied to our dataset. Five algorithms were tested: K-Means, Affinity Propagation, Mean Shift, Spectral Clustering, and Hierarchical Clustering. These algorithms represent varied approaches: centroid-based, graph-based, density-based, and hierarchical-based. Several configurations per algorithm were evaluated, varying hyperparameters and the number of clusters. The rationale for using clustering techniques follows previous research that leveraged unsupervised methods to identify latent behavioral patterns on social media. In particular, Wang (2022) [14] applied clustering to extract social behavioral features among university students, showing how algorithmic groupings can reveal underlying social tendencies that are not evident through direct observation. Similarly, our study employs clustering as a data-driven strategy to uncover behavioral structures within adolescent online interactions. Table 2 summarizes the results, showing the algorithm, configuration, number of clusters, and metrics.

Table 2.

Comparison of clustering algorithms, configurations, and evaluation metrics.

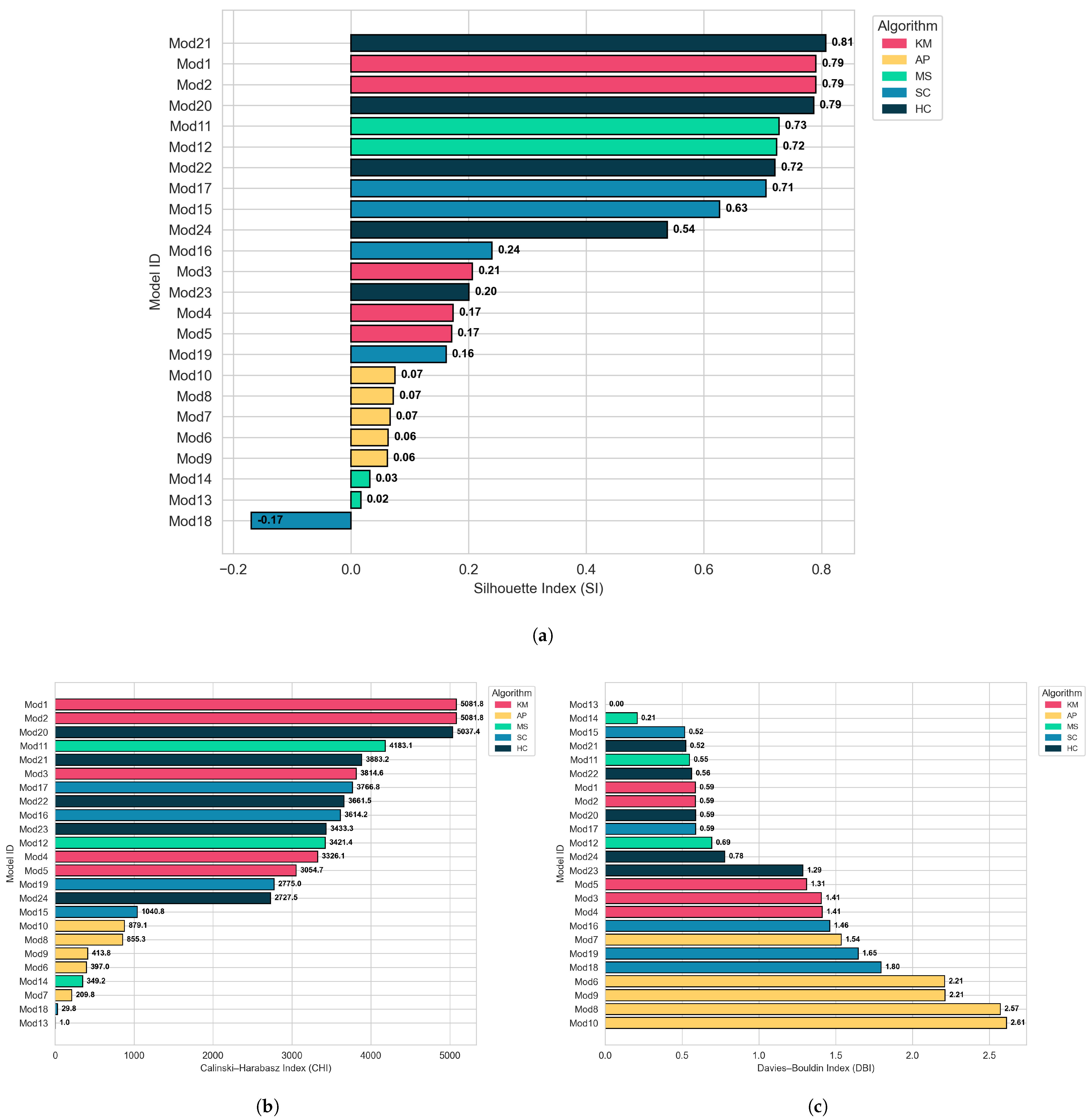

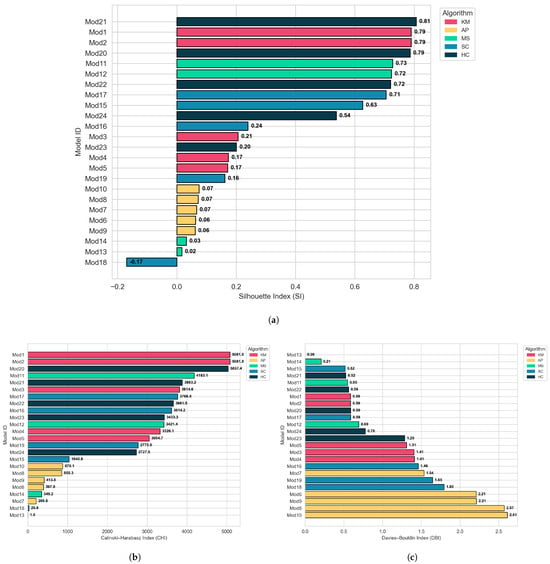

HC with complete linkage and K-Means with three clusters achieved the best Silhouette scores (0.8071 and 0.7905). This indicates well-defined clusters. Configurations with more clusters, such as SC with five clusters, showed negative metrics. Mean Shift excelled with the default bandwidth but failed with high values. It is observed that parameter optimization is key to improving results.

Configurations with more clusters, such as SC with five clusters, showed negative metrics. Mean Shift excelled with the default bandwidth but failed with high values. It is observed that parameter optimization is key to improving results. However, the weaker performance of Affinity Propagation and Spectral Clustering suggests that purely algorithmic partitioning may overlook the psychological and contextual dimensions influencing online behavior. As highlighted by [16,19], social media interactions are shaped not only by structural relationships but also by emotional and value-based factors, such as identity, friendship, or perceived respect. This reinforces that computational clustering must be complemented by interpretive frameworks to fully capture the complexity of digital social dynamics.

Figure 4a shows a bar chart for the Silhouette metric. The highest values are in HC (complete, three clusters) and K-Means (multiple with three clusters). Configurations such as SC with five clusters fall into negative territory, while AP and Mean Shift with many clusters have low values. This highlights that fewer clusters favor cohesion. The bars decrease with increasing parameter complexity. Figure 4b presents the graph for Calinski–Harabasz. K-Means and HC dominate with values over 5000 in three clusters. Mean Shift with bandwidth None reaches 4183. Configurations with many clusters, such as Mean Shift with 898, drop to 1.0. SC varies from 3766 to 29. This indicates better separation in simple setups. Figure 4c illustrates Davies–Bouldin with bars. Low (best) values are for SC (0.5166) and Mean Shift (0.0 at the extreme). HC and K-Means are around 0.5–0.6 at the optimal level. Poor configurations rose to 2.611 for AP. Mean Shift with bandwidth 0.5 reaches 0.0, but with many clusters. This indicates sensitivity to noise. Low bars favor density in specific cases.

Figure 4.

Chart showing the internal validation metrics: (a) Silhouette Index. (b) Calinski–Harabasz Index. (c) Davies–Bouldin Index.

Hypothesis tests were applied to the internal validation metrics (Silhouette, Calinski–Harabasz, and Davies–Bouldin) to compare all models and identify the most prominent ones. The Friedman test was appropriate for nonparametric comparisons with multiple treatments [57]. The analysis yielded a statistic of 49.76 with a p-value of 0.0009, confirming the existence of significant differences between configurations (p < 0.05). Subsequently, Nemenyi’s post hoc test was used to perform pairwise comparisons [58], identifying which models exhibited statistically significant differences in performance, with p-values indicating significant differences (e.g., Mod21 vs. others often <0.01).

The results show that Hierarchical Clustering (HC) in the Mod21 configuration achieved the best overall performance, with an average rank of 3.33. K-Means, in the Mod1 and Mod2 configurations, followed closely, both obtaining an average rank of 3.83. In fourth place was Mean Shift (Mod11) with 4.67, and in fifth place HC (Mod20) with 5.33. The average rank values derive from the Friedman test, which assigns ranks to each configuration based on the evaluated metrics-lower ranks indicating better overall performance. The Nemenyi post hoc test further confirmed that the first three configurations (Mod21, Mod1, and Mod2) are significantly superior (p < 0.01) to the lower-performing ones, reinforcing the robustness of the hierarchical and K-Means approaches. Full comparative results for all 24 configurations are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Average ranks obtained by all models.

These findings reinforce that, under a three-cluster configuration, models based on HC (Mod21 and Mod20) and K-Means (Mod1 and Mod2) are positioned as the most consistent. At the same time, alternative approaches such as Spectral Clustering or Affinity Propagation exhibit inferior performance. More broadly, these outcomes align with the theoretical perspective emphasized in recent literature-that risk perception and digital behavior are inherently multidimensional phenomena. As discussed in prior studies, integrating computational and psychological approaches enables a deeper understanding of how adolescents interpret and respond to online risks [16,19]. Thus, our results not only validate the technical robustness of clustering-based analysis but also contribute to the interdisciplinary effort to connect algorithmic insight with behavioral meaning in digital contexts.

These findings reinforce that, under three clusters, the configurations based on HC (Mod21 and Mod20) and K-Means (Mod1 and Mod2) are positioned as the most consistent. At the same time, alternative approaches such as Spectral Clustering or Affinity Propagation show inferior performance in comparison.

5. Discussion

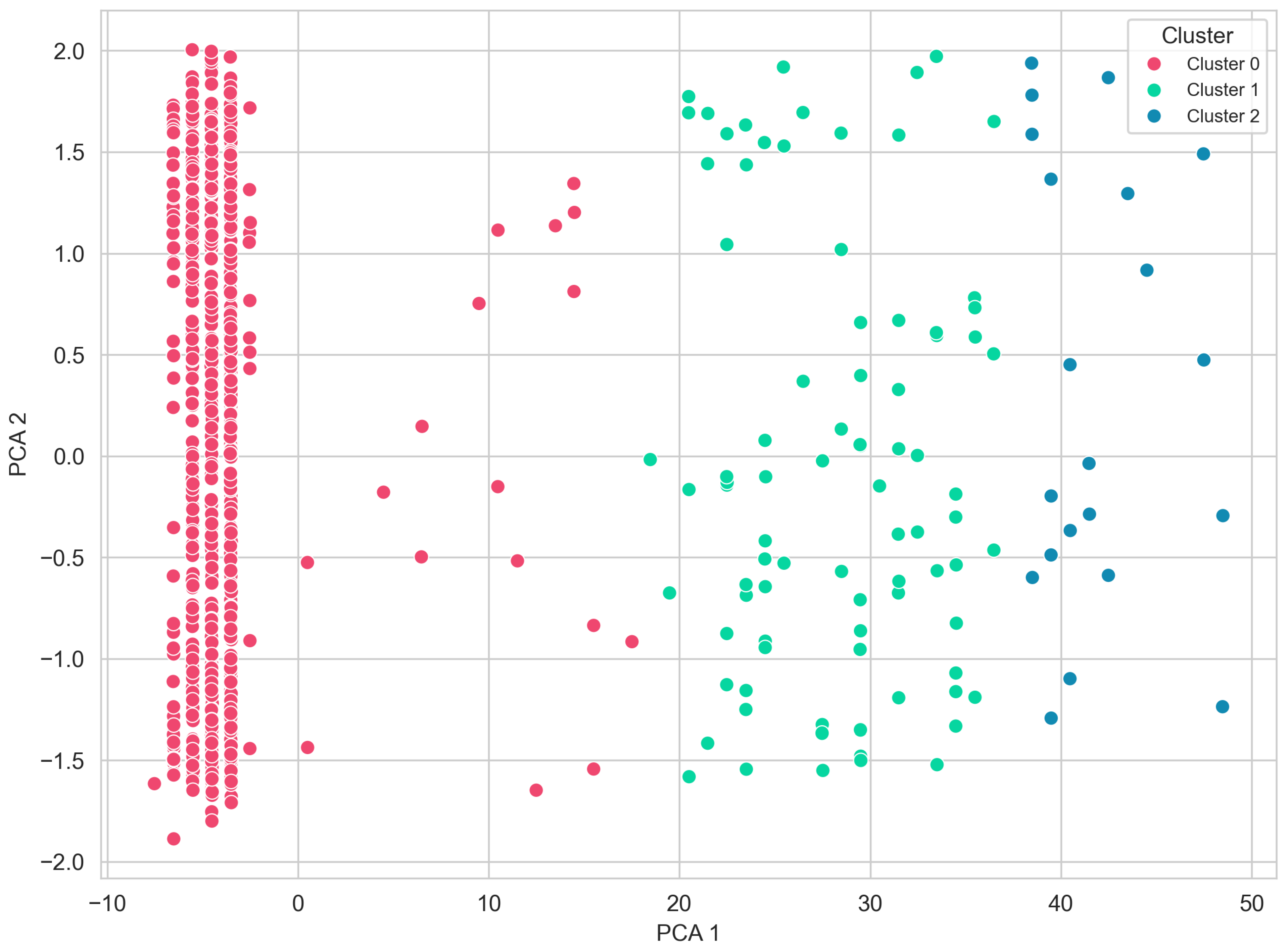

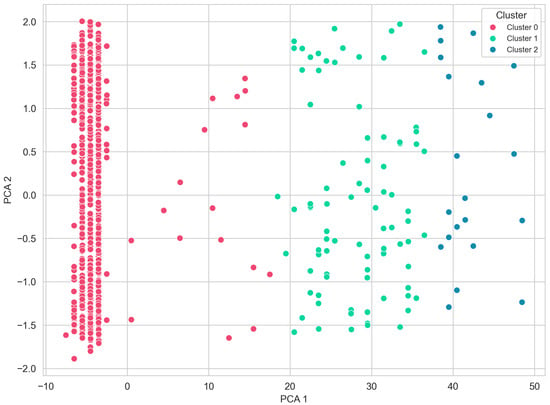

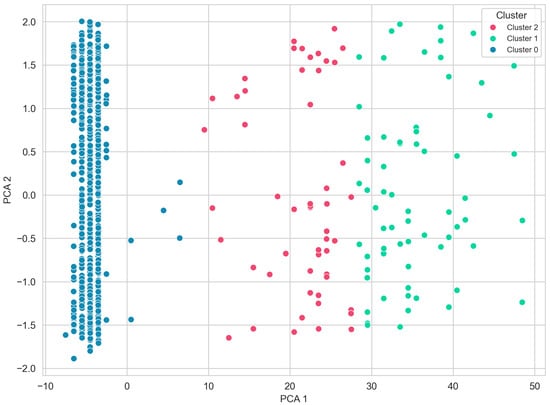

Three well-differentiated groups were identified on the PCA plane in the configuration obtained with HC (Mod21). Cluster 0, composed mainly of children around 11 years old (n = 787), shows a high prevalence of digital risk behaviors such as following strangers (60%), followed by pretending to be someone else (20%). Cluster 1, composed chiefly of adults around 43 years old (n = 87), maintains the tendency to follow strangers, although taking photographs without permission is more prevalent in this group. On the other hand, Cluster 2, made up of adults over 57 years old (n = 21), stands out for the presence of practices linked to the publication of photographs without consent as the second most reported behavior. As shown in Figure 5, the clusters generated with this algorithm are presented visually.

Figure 5.

PCA representation for hierarchical clustering (Mod21).

Across all three groups, the main perceived experiences of digital harassment are receiving requests for personal data and experiencing advances, which suggests a typical pattern of vulnerability at different stages of life. Regarding responses to these situations, seeking help from parents remains the first option in all three clusters, followed by the police; however, some significant nuances are evident: while in Clusters 0 and 1, family members appear as the third source of support, in Cluster 2, a shift toward friends emerges as the predominant alternative, reflecting a generational difference in the construction of networks of trust and support.

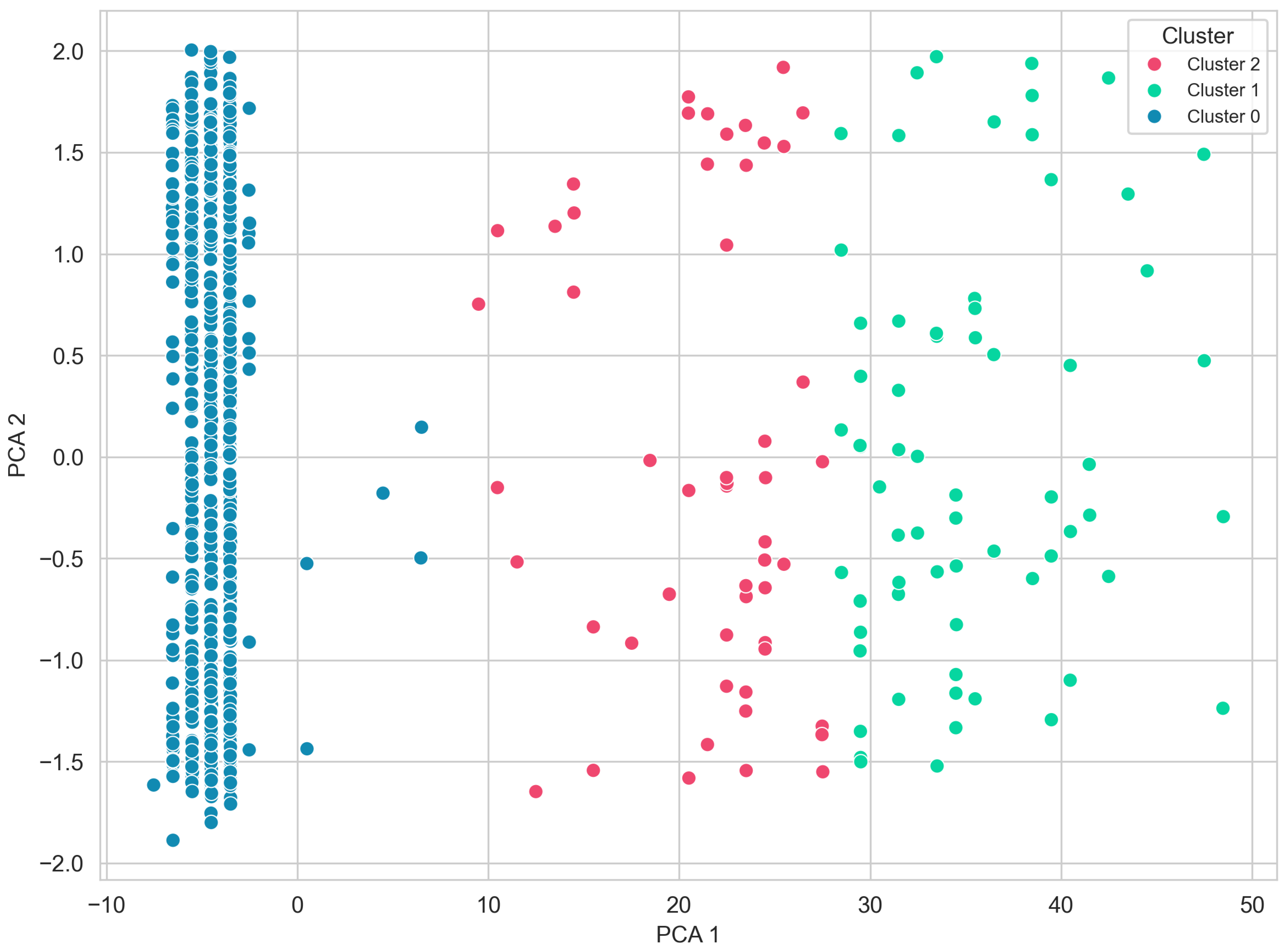

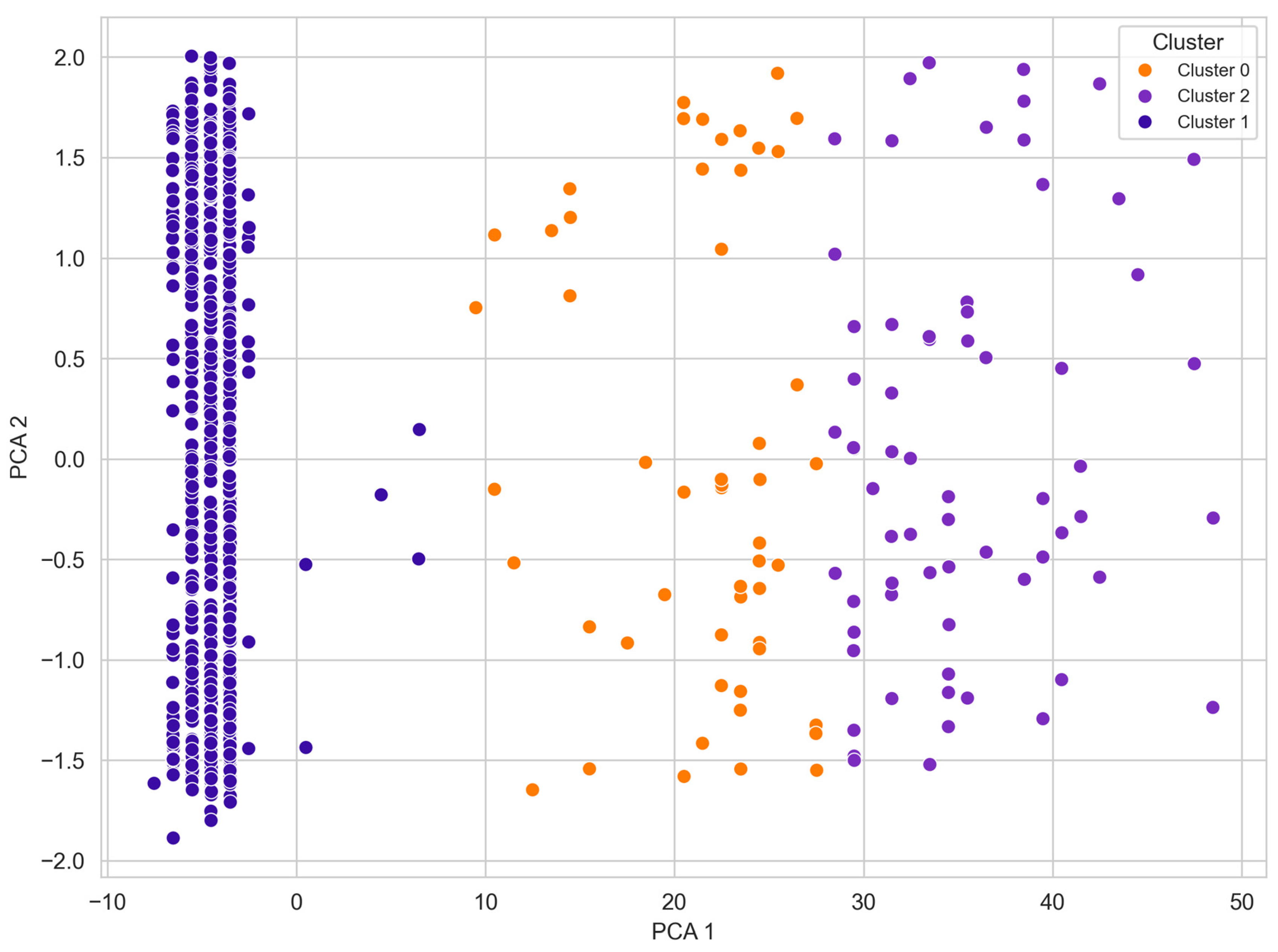

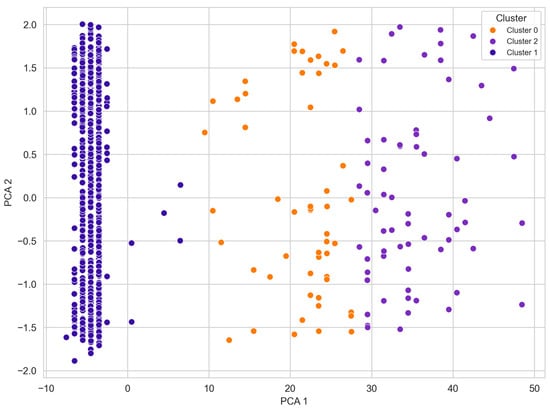

In the configuration obtained with K-Means (Mod1 and Mod2), the clusters show clear differentiation in terms of age and social media usage patterns. Cluster 0, composed of young people with an average age of 11, represents the entire student population and reflects a strong use of platforms such as YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram, which coincides with trends typical of the child and adolescent population. Cluster 1, made up of adults approximately 51 years old, prioritizes TikTok, followed by YouTube and Facebook, demonstrating an adaptation to emerging networks while maintaining an established platform like Facebook. Cluster 2, made up of young adults with an average age of 36, shows a digital consumption pattern centered on TikTok, Facebook, and YouTube, suggesting a balance between recreational social networks and more formal interaction. As shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7, the clusters generated with this algorithm are presented visually.

Figure 6.

PCA representation for K-Means clustering (Mod1, initialization = k-means++).

Figure 7.

PCA representation for K-Means clustering (Mod2, initialization = random).

These results directly inform Peru’s ongoing efforts toward digital safety and education. The identification of a cluster of children (around 11 years old) with high-risk online behaviors underscores the need for preventive digital education at an early age, before secondary school. While national initiatives have strengthened technical safeguards—such as centralized authentication in educational platforms—there is a parallel need to embed digital-citizenship training that addresses behavioral dimensions inside the social media and apps students use daily.

Regarding reported risk situations, a worrying pattern is observed across all three groups: 41.5% of children admit to having invited strangers representing the Cluster 0, a figure that rises to 46.27% in Cluster 1 and reaches 58.49% in Cluster 2, demonstrating that exposure to unsafe practices is not limited to early childhood but increases in early adulthood. Finally, when analyzing responses to situations of digital harassment or risk, it is observed that in all three clusters, parents remain the primary source of support, even among adults, suggesting that trust in the family environment continues to be the central axis of support networks in all age groups analyzed.

At the policy level, these findings are aligned with Peru’s Digital Transformation Policy toward 2030, which prioritizes inclusion, digital skills, and security. The presence of digital risks across different stages of life demonstrates that digital literacy is a continuous requirement, extending beyond the school environment into workplaces and community contexts. Public institutions that offer training in digital and cybersecurity topics for local authorities can incorporate modules designed for specific age groups, such as basic digital safety for children in early primary education, privacy and digital resilience for working adults, and consent and responsible media use for older adults. Schools can integrate behavioral indicators, including reports of being followed online or sharing personal information, to support adaptive policy evaluation and informed decision making. Awareness initiatives for families and communities also play a key role, since many adults seek support from relatives when facing online harassment or misuse of personal data. Programs that encourage community ambassadors and intergenerational dialogue can serve as culturally appropriate strategies to strengthen digital resilience across diverse social contexts.

6. Conclusions

The comparative analysis of clustering algorithms reveals that hierarchical and centroid-based approaches exhibit the best performance in terms of cluster cohesion, separation, and robustness when configured with three clusters. These configurations consistently outperform alternative methods such as Affinity Propagation or Spectral Clustering, which show sensitivity to lower hyperparameters and metrics in scenarios with a larger number of clusters. Statistical validation using the Friedman–Nemenyi test confirms significant differences, highlighting the importance of parametric optimization and the preference for simple models for datasets with age and behavioral patterns, suggesting their applicability in similar unsupervised analysis studies.

Regarding digital risks in children and adults, the identified clusters highlight shared vulnerabilities, such as stranger addiction and exposure to requests for personal data, which persist throughout life but intensify in early adulthood. Even among adults, the predominant dependence on family support highlights the need for educational interventions that strengthen trust networks beyond the family nucleus, especially for children around 11 years old, representing the largest group exposed to platforms like TikTok and Instagram. These findings emphasize the urgency of preventive policies that address generational differences in social media use and promote proactive responses to digital bullying.

7. Limitations and Future Works

This study presents valuable insights into risk perception among Peruvian children and adolescents. However, it has some limitations. The dataset is cross-sectional, so it does not allow causal inference or the analysis of changes over time. The research relies on self-reported survey data, which may be affected by recall bias or socially desirable responses. In addition, the sample represents specific educational contexts in Peru, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other regions or school settings. Future studies should address these limitations to strengthen the evidence and applicability of the findings.

Future work will address these challenges and extend the current approach. Longitudinal data collection will allow monitoring changes in digital-risk perception and evaluating the effects of training and prevention programs. Advanced machine learning methods, including deep clustering models, will help improve the identification of risk-perception groups in diverse datasets. Collaboration with schools and educational authorities will support designing and evaluating targeted digital-literacy interventions based on the identified profiles. Finally, expanding the analysis to other Latin American countries will make it possible to compare regional risk patterns and inform public policy across broader educational and cultural contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.P.V.; methodology, Y.P.V.; software, P.A.R.S.; validation, Y.P.V. and R.S.E.Q.; formal analysis, Y.P.V., R.S.E.Q. and P.A.R.S.; investigation, Y.P.V., R.S.E.Q. and P.A.R.S.; data curation, P.A.R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.P.V., R.S.E.Q. and P.A.R.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.P.V.; visualization, P.A.R.S.; supervision, Y.P.V. and R.S.E.Q.; funding acquisition, Y.P.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad La Salle Arequipa, Peru grant number P-01-CFI-2024 and the APC was funded by Universidad La Salle Arequipa, Peru.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article would like to acknowledge Universidad La Salle Arequipa, Peru, for funding this study. We also acknowledge to eBIZ LATIN AMERICA, a company based in Lima, Peru, for conducting the study that collected the data for this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mandić, S.; Ricijaš, N.; Dodig Hundrić, D. Effects of Gender and Social Network Use on High School Students’ Emotional Well-Being during COVID-19. Psychiatry Int. 2024, 5, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez García, A.; Gutiérrez-Arenas, M.P.; Ruiz-Calzado, I. Social networks: Influence on the deep learning of secondary school students. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2025, 46, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira De Freitas, R.J.; Oliveira, T.N.C.; Melo, J.A.L.D.; do Vale e Silva, J.; de Oliveira e Melo, K.C.; Fernandes, S.F.F. Percepções dos adolescentes sobre o uso das redes sociais e sua influência na saúde mental. Enfermería Glob. 2021, 20, 324–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Guillén, B.; Chávez-Vera, M.D. El uso de las redes sociales: Una perspectiva de género. Maskana 2021, 12, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astorga-Aguilar, C.; Schmidt-Fonseca, I. Peligros de las redes sociales: Cómo educar a nuestros hijos e hijas en ciberseguridad. Rev. Electrónica Educ. 2019, 23, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkovic, R.; Vejmelka, L.; Kljucevic, Z. Use of security settings on social networks of elementary and high school students in the Split-Dalmatia County. In Proceedings of the 2020 43rd International Convention on Information, Communication and Electronic Technology (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 28 September–2 October 2020; pp. 1476–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcelén-García, S.; Díaz-Bustamante Ventisca, M.; Galmes-Cerezo, M. Young People’s Perception of the Danger of Risky Online Activities: Behaviours, Emotions and Attitudes Associated with Their Digital Vulnerability. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, J.J.; Álamos, P.; Guzmán, P.; Marsollier, R.; Exposito, C.; Romo, F.; López, C.; Miranda, R. Cyberbullying against teachers in Latin America during the pandemic: The negative effects on their Levels of Well-Being through Burnout. J. Sch. Violence 2025, 24, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, S.; Magis-Weinberg, L.; Stoilova, M.; Livingstone, S.; Orben, A. Social media and adolescent well-being in the Global South. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 46, 101318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamud, O.; Cueto, S.; Cristia, B.; Beuermann, D. Do children benefit from internet access? Experimental evidence from Peru. J. Dev. Econ. 2019, 138, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado Chamorro, M.; Medina Gamero, A.; Tello Cabello, R. La salud mental en adolescentes: Internet, redes sociales y psicopatología. Atención Primaria 2022, 54, 102487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Oyola, J.C.; Walter-Chavez, D.M.; Zila-Velasque, J.P.; Pereira-Victorio, C.J.; Failoc-Rojas, V.E.; Vera-Ponce, V.J.; Valladares-Garrido, D.; Valladares-Garrido, M.J. Internet addiction and mental health disorders in high school students in a Peruvian region: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontalvo-Herrera, T.J.; Vega-Hernández, M.A.; Mejía-Zambrano, F. Método de clustering e inteligencia artificial para clasificar y proyectar delitos violentos en Colombia. Rev. Científica Gen. José María Córdova 2023, 21, 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, H. Behavior feature extraction method of college students’ social network in sports field based on clustering algorithm. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 31, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tao, S.; Zhang, Y.L.; Zhou, J.; Wei, J.; Chen, M.; Hu, Q.; Zheng, H.; Wang, Z.L. Examining the spectrum of problematic online behaviors in Chinese adolescents: A network analysis of smartphone, gaming, and social media use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2025, 167, 108611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korres Alonso, O.; Elexpuru-Albizurii, I.; Moro Inchaurtieta, Á.; Aran-Ramspott, S. Redes sociales y valores percibidos: Diferencias de género en adolescentes y jóvenes. Aloma Rev. De Psicol. Ciències De L’Educació I De L’Esport 2025, 43, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Gracie, J.; Alsoubai, A.; Razi, A.; Wisniewski, P.J. Personally Targeted Risk vs. Humor: How Online Risk Perceptions of Youth vs. Third-Party Annotators Differ based on Privately Shared Media on Instagram. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual ACM Interaction Design and Children Conference, Delft, The Netherlands, 17–20 June 2024; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi, A.; Alsoubai, A.; Kim, S.; Ali, S.; Stringhini, G.; De Choudhury, M.; Wisniewski, P.J. Sliding into My DMs: Detecting Uncomfortable or Unsafe Sexual Risk Experiences within Instagram Direct Messages Grounded in the Perspective of Youth. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2023, 7, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.; Liu, S.X.; Luo, M.; Mieczkowski, H. Psychological Well-Being and Social Media Use: A Meta-Analysis of Associations between Social Media Use and Depression, Anxiety, Loneliness, Eudaimonic, Hedonic and Social Well-Being. 2022. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4053961 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Sani, A.I.; Vieira, A.P.; Dinis, M.A.P. Social Networks, the Internet, and risks: Portuguese parents’ perception of online grooming. Rev. Avaliação Psicológica 2021, 20, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi, A.; Agha, Z.; Chatlani, N.; Wisniewski, P. Privacy Challenges for Adolescents as a Vulnerable Population. 2020. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3587558 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Badillo-Urquiola, K.; Harpin, S.; Wisniewski, P. Abandoned but Not Forgotten: Providing Access While Protecting Foster Youth from Online Risks. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Interaction Design and Children, Stanford, CA, USA, 27–30 June 2017; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, P.; Xu, H.; Rosson, M.B.; Perkins, D.F.; Carroll, J.M. Dear Diary: Teens Reflect on Their Weekly Online Risk Experiences. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 3919–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazdur, M.; Tutus, D.; Haag, A.C. Risk Factors for Problematic Social Media Use in Youth: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2025, 10, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzola, E.; Spina, G.; Agostiniani, R.; Barni, S.; Russo, R.; Scarpato, E.; Di Mauro, A.; Di Stefano, A.V.; Caruso, C.; Corsello, G.; et al. The Use of Social Media in Children and Adolescents: Scoping Review on the Potential Risks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vismara, M.; Girone, N.; Conti, D.; Nicolini, G.; Dell’Osso, B. The current status of Cyberbullying research: A short review of the literature. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2022, 46, 101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Haykal, H.A.; Youssef, E.Y.M. Child Sexual Abuse and the Internet—A Systematic Review. Hum. Arenas 2023, 6, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Gómez, P.; Larrañaga, K.P.; Rangel, C.; Ortega-Mohedano, F. Critical Analysis of the Risks in the Use of the Internet and Social Networks in Childhood and Adolescence. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 683384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, F.; Chen, T.; Pan, L.; Beliakov, G.; Wu, J. A Brief Survey of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques for E-Commerce Research. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 2188–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, A.A. Comprehensive analysis of clustering algorithms: Exploring limitations and innovative solutions. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uelwer, T.; Robine, J.; Wagner, S.S.; Höftmann, M.; Upschulte, E.; Konietzny, S.; Behrendt, M.; Harmeling, S. A survey on self-supervised methods for visual representation learning. Mach. Learn. 2025, 114, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moujahid, A.; Dornaika, F. Advanced unsupervised learning: A comprehensive overview of multi-view clustering techniques. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Singh, D. A comprehensive review of clustering techniques in artificial intelligence for knowledge discovery: Taxonomy, challenges, applications and future prospects. Adv. Eng. Informatics 2024, 62, 102799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitafi, S.; Anwar, T.; Sharif, Z. A Taxonomy of Machine Learning Clustering Algorithms, Challenges, and Future Realms. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikotun, A.M.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L.; Abuhaija, B.; Heming, J. K-means clustering algorithms: A comprehensive review, variants analysis, and advances in the era of big data. Inf. Sci. 2023, 622, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Iqbal, M.A.; Shil, A.; Chowdhury, M.J.M.; Moni, M.A.; Sarker, I.H. An Improved K-means Clustering Algorithm Towards an Efficient Data-Driven Modeling. Ann. Data Sci. 2024, 11, 1525–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Wang, L.; Pan, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, M. Affinity Propagation Based on Structural Similarity Index and Local Outlier Factor for Hyperspectral Image Clustering. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulah, S.; Atwa, W.; Abdelmoniem, A.M. Active clustering data streams with affinity propagation. ICT Express 2022, 8, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; He, L.; Diao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, G.; Chen, Y. A Novel Neighborhood Granular Meanshift Clustering Algorithm. Mathematics 2022, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumaila, M.N. A Comparison of K-Means and Mean Shift Algorithms. Int. J. Theor. Appl. Math. 2021, 7, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Li, C.; Jin, D.; Ding, S. Survey of spectral clustering based on graph theory. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 151, 110366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berahmand, K.; Saberi-Movahed, F.; Sheikhpour, R.; Li, Y.; Jalili, M. A Comprehensive Survey on Spectral Clustering with Graph Structure Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.13597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.X.; Dwyer, D.; Zhu, Y.; Smith, C.L.; Du, L.; Filia, K.M.; Bayer, J.; Menssink, J.M.; Wang, T.; Bergmeir, C.; et al. An overview of clustering methods with guidelines for application in mental health research. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 327, 115265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezugwu, A.E.; Ikotun, A.M.; Oyelade, O.O.; Abualigah, L.; Agushaka, J.O.; Eke, C.I.; Akinyelu, A.A. A comprehensive survey of clustering algorithms: State-of-the-art machine learning applications, taxonomy, challenges, and future research prospects. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 110, 104743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasi, O.; Bel, O.; Manzano, J.; Barker, K. The Landscape of Modern Machine Learning: A Review of Machine, Distributed and Federated Learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.03120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias Vázquez, F.; Zseby, T. Temporal silhouette: Validation of stream clustering robust to concept drift. Mach. Learn. 2024, 113, 2067–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.; Aupetit, M.; Shin, D.; Cho, A.; Park, S.; Seo, J. Sanity Check for External Clustering Validation Benchmarks using Internal Validation Measures. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.10042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampolo, R.F.; Lopes, F.H.R.; de Oliveira, R.M.S.; Fernandes, M.F.; Dmitriev, V. Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering Strategies for Label Propagation in Partial Discharge Data Sets. Energies 2024, 17, 5936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashari, I.F.; Nugroho, E.D.; Baraku, R.; Yanda, I.N.; Liwardana, R. Analysis of Elbow, Silhouette, Davies-Bouldin, Calinski-Harabasz, and Rand-Index Evaluation on K-Means Algorithm for Classifying Flood-Affected Areas in Jakarta. J. Appl. Informatics Comput. 2023, 7, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, F.; Riad, R.; Guillaume, S. PDBI: A partitioning Davies-Bouldin index for clustering evaluation. Neurocomputing 2023, 528, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, O.; Bruneau, P.; Sottet, J.S.; Torregrossa, D. Landscape of High-performance Python to Develop Data Science and Machine Learning Applications. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.03307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; Van Der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, K.; Mankoff, J.; Potluri, V. MatplotAlt: A Python Library for Adding Alt Text to Matplotlib Figures in Computational Notebooks. Comput. Graphics Forum 2025, 44, e70119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A. Machine learning in materials research: Developments over the last decade and challenges for the future. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2024, 33, 101189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe, J.O.Q.; Quispe, A.C.F.; Calvo, N.C.L.; Toledo, O.C. Analysis and Selection of Multiple Machine Learning Methodologies in PyCaret for Monthly Electricity Consumption Demand Forecasting. Mater. Proc. 2024, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez Espejo, F.; Toche Vega, F.L.; Zúñiga Izquierdo, C.E.; Iriarte Ahon, E.A. Percepción y Uso de las Redes Sociales en Escolares en el Perú, 2024. Available online: https://ebiz.pe/noticias/ebiz-presento-estudio-sobre-riesgos-a-menores-peruanos-en-internet/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Liu, J.; Xu, Y. T-Friedman Test: A New Statistical Test for Multiple Comparison with an Adjustable Conservativeness Measure. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2022, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, W. A SAS macro for testing differences among three or more independent groups using Kruskal-Wallis and Nemenyi tests. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. [Med. Sci.] 2012, 32, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.