Abstract

In social virtual reality (VR) and metaverse platforms, users express their identity through both avatar appearance and on-avatar textual cues, such as speech balloons. However, little is known about how the harmony between these cues influences self-representation and social impressions. We propose that when avatar appearance and text design, including color, font, and tone, are consistent, users experience a stronger self-expression fit and elicit greater interpersonal affinity. A within-subject study () in VRChat manipulated the social context, color harmony between avatar hair and text, and style or content consistency between tone and font. Questionnaires provided composite indices for perceived congruence, self-expression fit, and affinity. Analyses included repeated-measures ANOVA, linear mixed-effects models, and mediation tests. Results showed that congruent pairings increased both self-expression fit and affinity compared to mismatches, with mediation analyses indicating that self-expression fit fully mediated the effect. These findings integrate theories of avatar influence and computer-mediated communication into a framework for metaverse design, highlighting the value of consistent avatar and text styling.

1. Introduction

Communication in online environments has shifted from text-based exchanges to embodied interactions using avatars in social VR and the metaverse. Avatars act as digital bodies, while speech balloons and text provide an additional channel for identity cues. Prior research has shown that avatar appearance influences self-perception and the impressions formed by others, a phenomenon often called the Proteus effect [1]. Similarly, research on computer-mediated communication has demonstrated that consistency across communication channels amplifies impressions, as explained by the hyperpersonal model [2]. Despite these findings, the combined effect of avatar appearance and on-avatar text design has not been systematically examined.

Recent commercial social VR platforms, including VRChat, Cluster, and Rec Room, now attract millions of users. These platforms are used not only for entertainment but also for education, professional meetings, and collaboration. In such contexts, the clarity and naturalness of self-representation become essential. Previous studies in human–computer interaction suggest that inconsistencies across modalities disrupt presence and rapport, while coherence across channels supports trust and smooth interaction. The present study positions avatar and text harmony as a key component of self-presentation, arguing that the ability to maintain a coherent identity is fundamental for sustainable communication in the metaverse.

Beyond entertainment and social activities, the metaverse is increasingly used for industrial applications such as remote collaboration, medical training, and educational instruction. For instance, enterprises deploy VR platforms for distributed teamwork, while universities adopt immersive classrooms that allow students to engage through avatars. In such domains, coherent identity projection is not merely aesthetic but instrumental to credibility, efficiency, and inclusivity (e.g., [3,4]).

Furthermore, self-presentation theory emphasizes that individuals strategically manage impressions in order to achieve social goals. When visual and textual signals conflict, this impression management is disrupted, potentially leading to reduced trust and less willingness to collaborate. Therefore, understanding avatar–text harmony is not only a theoretical challenge but also a practical necessity for ensuring effective interaction in professional metaverse contexts (e.g., [2]).

In addition, theoretical perspectives from psychology offer further motivation. Gestalt principles of perception highlight that humans interpret stimuli holistically, and fluency theory proposes that stimuli which are easier to process are evaluated more positively [5,6,7]. Taken together, prior evidence suggests a principled bridge from theory to hypotheses. Proteus-effect findings imply that visual appearance can shape self-perception, color and typography studies imply that textual styling conveys warmth/competence, and multimodal-coherence and processing-fluency accounts imply that cross-channel consistency enhances authenticity and interpersonal judgments. Therefore, we derive: H1 (harmony elevates self-expression fit and affinity), H2 (the effect on affinity is mediated by self-expression fit), and H3 (effects increase with immersion where cue coupling tightens).

This work tests three hypotheses stated verbatim in Section 3.

Contribution and Scope

We formalize a theory-driven account that links cross-modal harmony to self-expression fit and interpersonal affinity; operationalize harmony with jointly controlled color, font, and tone; evaluate effects across immersion levels with reliability/sphericity/effect-size and model-based robustness; and derive metaverse interface implications while restricting claims to the tested settings (within-subject, ).

2. Related Work

2.1. Avatar-Mediated Behavior and Impressions

Avatars serve as transformed self-representations that can alter user behavior and shape how others respond. Studies have demonstrated that variations in avatar appearance, such as height, attractiveness, and clothing, can shift dominance, confidence, and perceived warmth. These effects show that the visual channel is powerful for signaling identity traits and is interpreted rapidly by observers. This pattern accords with the Proteus effect and related evidence that avatar appearance shapes anthropomorphism, credibility, and attraction [1,8,9,10,11,12].

2.2. Textual Expressivity in Online Communication

Textual features, including font, length, and positivity, also influence impression formation. The hyperpersonal account emphasizes that senders manage cues to achieve desired impressions, especially in environments that allow careful self-presentation. In metaverse settings, on-avatar text functions as a coupled presentation channel that can either reinforce or contradict visual signals from avatars. Work in color psychology and typography also demonstrates that seemingly subtle choices affect perceived warmth, competence, and trust [2,13,14,15,16,17].

2.3. Multimodal Coherence

Research on multimodal perception highlights that coherence across channels supports presence and reduces cognitive dissonance. When avatar appearance and text style align in meaning, the combination is processed more fluently and judged more positively; deliberate mismatches may draw attention but can undermine comfort and authenticity [5,18,19].

2.4. Metaverse Identity Work

Recent studies document how users explore gender and identity in VRChat [4] and how organizations value avatar customization [3]. These developments underscore the practical importance of coherent avatar and text design for self-presentation and social interaction in immersive spaces.

2.5. Gap and Positioning

Prior work has rarely treated avatar and on-avatar text as a unified semiotic package in immersive settings. The present work positions harmony as the bridge that unifies these channels in social VR, links it to perceived authenticity and affinity, and specifies conditions under which harmony matters most.

3. Theory and Hypotheses

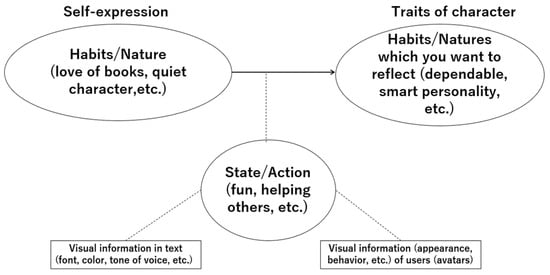

Figure 1 depicts the hypothesized structure in this study. Solid arrows represent causal paths from avatar–text harmony to self-expression fit and from self-expression fit to interpersonal affinity. Dashed lines represent the moderating role of immersion (2D < VR < social VR). Because moderation does not imply an additional causal direction, dashed lines are drawn without arrowheads.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model illustrating causal and moderating relations among variables. Solid arrows denote hypothesized causal paths (Harmony → Self-expression fit → Interpersonal affinity). Dashed lines denote moderation by immersion (2D → VR → Social VR); they do not indicate causal direction and therefore have no arrowheads.

We posit that avatar–text harmony—defined as the congruence of color, font, and tone with avatar appearance—enhances self-expression fit, which in turn increases interpersonal affinity. Perceived congruence is treated as a proximal check that the harmony manipulation is noticed, whereas self-expression fit captures the deeper identity-relevant appraisal that we expect to drive affinity. We further predict a graded moderation by immersion (2D < VR < social VR), consistent with embodiment and telepresence accounts. Higher immersion increases embodiment and telepresence, which tighten sensorimotor coupling and the integration of visual and textual cues; as a result, cross-modal congruence becomes more diagnostic of identity and more consequential for judgments.

Based on the above theoretical considerations, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1.

Harmonious compared to mismatched avatar–text combinations produce a higher self-expression fit and higher interpersonal affinity.

H2.

The effect of avatar–text harmony on affinity is mediated by self-expression fit.

H3.

Effects strengthen with immersion, with greater embodiment and tighter cue coupling in social VR compared with VR and 2D.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Overview of Approach

We test H1–H3 in a within-subject design from a fixed third-person vantage in a private VRChat world (standardized lighting/camera; free chat disabled). After each scene, participants rate perceived congruence, self-expression fit, and interpersonal affinity. Text-focused stimuli are included to isolate textual design (tone × style), while retaining the scene context; participants evaluated only the text stimulus in this group.

4.2. Participants and Ethics

Twenty-one adults from a university community took part in the study with informed consent. The protocol was approved by the ethics board of the University of Electro-Communications (approval no. H25019). All participants reported normal or corrected vision and basic familiarity with VR. Participants were university students/graduate students aged 18–30; 20 were male and 1 was female; and regarding metaverse experience, 7 participants reported prior metaverse experience whereas 14 reported no prior experience.

4.3. Apparatus and Platform

The study used a Meta Quest 2 headset tethered to a PC [20]. A private VRChat world was created with controlled lighting and fixed viewing angles to standardize experience across participants. Speech balloons with predesigned fonts and colors were displayed above avatars. Chat input was disabled to prevent uncontrolled variation.

4.4. Sessions and Immersion Levels

We operationalized immersion at three levels: (i) a 2D desktop session (non-embodied viewing on a standard monitor), (ii) a VR session (single-user embodied viewing via HMD), and (iii) a social VR session (multi-user, in-world viewing in a private VRChat world). Scene content, camera angle, and timing were matched as closely as possible across sessions; order was counterbalanced at the block level.

4.5. Task

Across all conditions, participants always evaluated the presenter-side avatar (or the text stimulus in text-focused conditions) as the single focal target.

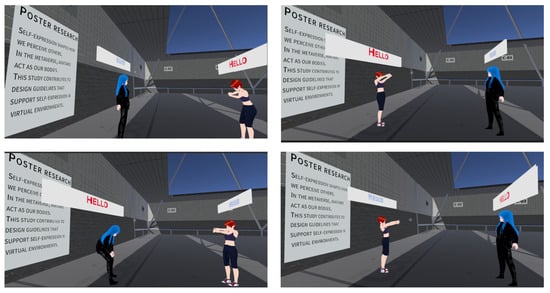

On each trial, participants observed a scene in which a single target avatar (the presenter avatar standing in front of the poster) was shown from a fixed third-person viewpoint in a private VRChat world. Even in scenes where another avatar appeared for contextual purposes, instructions clarified that participants must evaluate only the presenter-side avatar. Participants never role-played this avatar; instead, they evaluated the target avatar strictly as observers. In Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, the presenter-side target is the avatar standing in front of the poster; any other avatar shown is contextual. Participants evaluated only the designated target (or only the text stimulus in the Text-content group), as instructed.

Figure 2.

Experimental conditions in the metaverse study (Harmony group). Top-left: congruent warm avatar with warm text; Top-right: congruent cool avatar with cool text; Bottom-left: mismatched cool avatar with warm text; Bottom-right: mismatched warm avatar with cool text. (The in-world text is displayed in Japanese for ecological validity; the conceptual contrasts are warm vs. cool. In each screenshot, the presenter-side target avatar is the one standing in front of the poster; the other avatar, if present, is contextual. These screenshots are illustrative examples of the experimental conditions; minor overlaps or partial occlusions of avatars and UI elements do not affect the operational definition of the conditions or the interpretation of the experimental results).

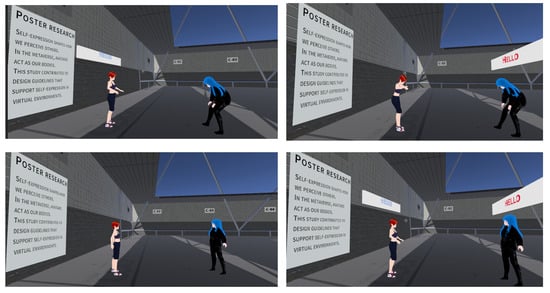

Figure 3.

Avatar-focused control conditions used in the experiment. These screens illustrate the appearance-only baseline in which no experimental speech-balloon text manipulation was introduced. Any constant platform UI elements visible in the scene were not evaluated. These screenshots are illustrative examples of the experimental conditions; minor overlaps or partial occlusions of avatars and UI elements do not affect the operational definition of the conditions or the interpretation of the experimental results.

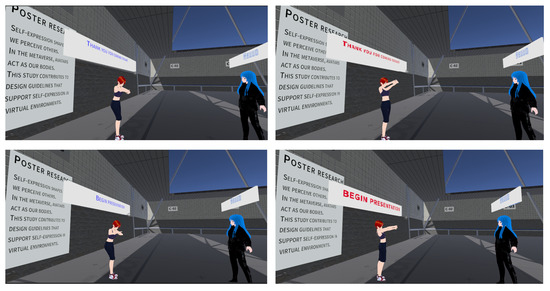

Figure 4.

Text-focused stimuli for evaluating text design (tone × style). The scene retains metaverse context for consistent presentation, but participants evaluated only the text stimulus as instructed. These screenshots are illustrative examples of the experimental conditions; minor overlaps or partial occlusions of avatars and UI elements do not affect the operational definition of the conditions or the interpretation of the experimental results.

After each scene, participants rated three constructs using 5-point Likert scales: (1) perceived harmony (congruence between the text balloon and the target avatar when text was present), (2) self-expression fit (two items; whether the target avatar represented an authentic and suitable identity), and (3) interpersonal affinity (six items: willingness to talk, friendliness, trust, warmth, positive impression, and satisfaction).

Two practice trials using non-experimental screenshots ensured comprehension. Trials were randomized with breaks. Free chat, gestures, and motion were disabled, and avatar poses were fixed to avoid additional cues.

4.6. Stimuli and Manipulations

We designed warm vs. cool manipulations following prior associations in color and typographic form, and validated all stimuli via manipulation checks before testing main effects. To avoid stereotype assumptions, cultural and individual differences are acknowledged in the Limitations; claims are restricted to the tested setting. Avatar clothing, facial expression, pose, and camera angle were held constant across appearance conditions; only hair color varied to manipulate warm vs. cool appearance. Stimulus screenshots removed extraneous text (e.g., in-world labels) to avoid unintended cues.

We used Rounded M+ 1c for the warm style and Roboto Condensed for the cool style, with size/letter-spacing/line-height/placement/contrast held constant; see Table 1 and Table 2 for licensing and theoretical justification.

Table 1.

Stimulus font and justification (Warm; added).

Table 2.

Stimulus font and justification (Cool; added).

4.6.1. Fonts and Typographic Mapping

Figure 2 summarizes the four Harmony conditions (congruent warm, congruent cool, and two mismatches) used in the metaverse study. To instantiate the “warm” (rounded) vs. “cool” (angular/condensed) text styles, we used Rounded M+ 1c for warm and Roboto Condensed for cool. These choices align with typographic findings that link rounded curvature and higher perceived warmth/approachability vs. angularity/condensation and higher perceived competence/professionalism. To avoid confounds beyond warm/cool, font size, letter-spacing, line height, placement, and contrast ratios were held constant across conditions. The exact font names, licenses, and versions are listed in Table 1 and Table 2.

As Table 3 shows, twelve conditions were organized into three independent groups (Harmony, Presence, Text-content).

Table 3.

Twelve experimental conditions structured as 4 × 3 groups.

Figure 2 summarizes the four Harmony conditions used in the metaverse study.

4.6.2. Avatar-Focused Control (Figure 3)

To estimate impressions attributable to avatar appearance without experimental manipulation of speech-balloon text content, we included an avatar-focused control group. The screenshots were captured under the same lighting and camera settings as the main stimuli. As shown in Figure 3, the scene may still contain constant on-screen UI elements used by the platform; however, no experimental balloon/text manipulation was introduced in this control group, and participants were instructed to evaluate the target avatar rather than any constant UI elements.

4.6.3. Text-Focused Stimuli (Figure 4)

To isolate the contribution of textual design (tone × style) while keeping the presentation format consistent with the metaverse scenes, we included a text-focused condition group. As illustrated in Figure 4, the scene may retain avatar and spatial context for ecological validity and consistent anchoring; however, participants were explicitly instructed to evaluate only the text stimulus (its color, font, and tone) rather than the avatar. This design enables assessment of text design effects while keeping the viewing context comparable to other conditions.

4.7. Measures

We targeted three constructs: perceived congruence (1 item), self-expression fit (2 items), and interpersonal affinity (6 items). All item wordings (English translations; original Japanese in Supplementary Materials) are listed in Table 4. Composites were formed by averaging items on 5-point Likert scales; reliability was typically . Cronbach’s is reported for internal consistency and is distinct from hypothesis testing. Note that, while Table 4 describes the constructs in terms of an “avatar–text pair” for brevity, in the Presence (avatar-only) conditions participants applied the same questions to the target avatar alone, in the Text-content (text-focused) conditions they applied them to the text stimulus alone.

Table 4.

Survey items for each construct (English translation).

Post-Experiment Structured Interview (Qualitative)

After completing the questionnaire for all conditions, participants took part in a short structured interview. The interviewer asked participants to briefly explain (i) what made the avatar–text pairing feel harmonious or disharmonious and (ii) what visual cues influenced their impressions (e.g., color matching, readability, or perceived appropriateness). Responses were recorded as written notes (or transcripts) and summarized using an inductive coding approach. Two researchers reviewed the responses and consolidated themes through discussions; disagreements were resolved by consensus. This qualitative component is reported as complementary, exploratory evidence given the modest sample size.

4.8. Procedure

Each scene was displayed for 10–15 s. Trials were presented in a randomized order, with short breaks between sessions to reduce fatigue. Two practice trials using non-experimental screenshots preceded the main block. Participants completed all assigned conditions within a single session.

4.9. Evaluation Framework and Statistical Plan

Primary analyses used repeated-measures ANOVA (Mauchly’s test; Greenhouse–Geisser corrections) with planned contrasts and effect sizes (partial , ). Complementary linear mixed-effects models included random intercepts for participants (and random slopes for Harmony where identifiable). Mediation (harmony → self-expression fit → affinity) was examined with bootstrap confidence intervals; indirect effects were considered significant if 95% CIs excluded zero. Exclusion rules, diagnostics, and sensitivity checks (e.g., removal of low-attention trials, subject-wise z-normalization, and one-item-drop analyses) are reported to avoid duplication elsewhere. Cronbach’s indexes internal consistency and is distinct from hypothesis testing. The analysis plan and reporting follow internal statistical guidance to ensure appropriate corrections and effect-size interpretation.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

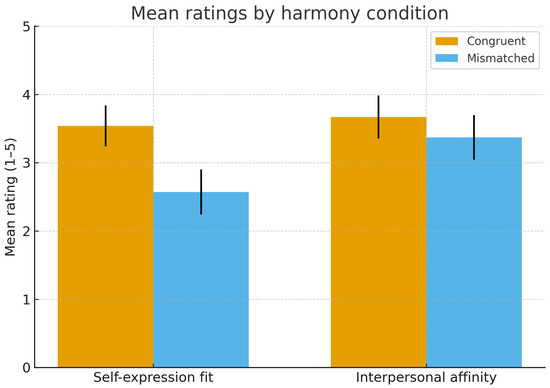

Across participants, composite reliability was high for affinity (Cronbach’s ) and acceptable for self-expression fit (). Means indicated a clear advantage for congruent conditions. For self-expression fit, the average rating was higher for congruent pairs (M = 3.54, SD = 0.68) than for mismatched pairs (M = 2.57, SD = 0.75). Affinity ratings were also higher for congruent pairs (M = 3.67) than mismatched pairs (M = 3.37). Distributions were unimodal and showed no severe skew.

As visualized in Figure 5, both self-expression fit and interpersonal affinity were higher in congruent than mismatched conditions, with non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals, consistent with the ANOVA results. As summarized in Table 5, descriptive statistics confirmed that congruent conditions yielded higher mean ratings than mismatched ones.

Figure 5.

Mean ratings of self-expression fit and interpersonal affinity by harmony condition. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Congruent conditions yielded significantly higher scores than mismatched conditions, supporting H1.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics for key outcomes by Harmony condition (collapsed across sessions). Means, standard deviations, and 95% CIs are reported.

5.2. Manipulation Checks

Color and tone manipulations were recognized as intended. Ratings of congruence were significantly higher in matched conditions compared to mismatched ones, confirming that the manipulation was effective. For tone, cheerful wording was judged significantly more positive than neutral wording, (, , ).

5.3. ANOVA Results

Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of Harmony on self-expression fit, (, , ), indicating that congruent conditions supported stronger self-expression. A smaller but significant effect of Session suggested that immersion enhanced self-fit. The Harmony × Session interactions were not significant for self-fit () nor affinity (; Table 6). Although the descriptive pattern was in the predicted direction, H3 was not supported and is treated as exploratory.

Table 6.

Repeated-measures ANOVA summaries. Greenhouse–Geisser corrections applied where required.

Regarding H3 (immersion-based moderation), the Harmony × Session interaction did not reach statistical significance for either self-expression fit (, partial ) or affinity (, partial ; Table 6). Thus, H3 was not supported in the current dataset and is interpreted as exploratory. Although the descriptive pattern was broadly consistent with stronger Harmony effects under more immersive conditions, these trends are non-confirmatory and require higher-powered replication.

For affinity, the main effect of Harmony was also significant, (, , ). Session effects were weaker but again consistent with stronger effects under immersive conditions.

5.4. Linear Mixed-Effects Models

Mixed-effects models with random intercepts for participants confirmed the main effects of Harmony on both self-expression fit and affinity. Inclusion of random slopes for Harmony did not qualitatively change conclusions.

5.5. Qualitative Summary

Across participants, qualitative comments frequently attributed perceived harmony to (a) color consistency between avatar appearance and on-avatar text, (b) semantic/tone appropriateness of the balloon style to the avatar’s perceived character, and (c) readability and visual salience in the scene. Conversely, disharmony was often described as a mismatch in “character impression” (e.g., cool-looking avatar paired with warm/casual balloon styling) or as visual incongruity that drew attention away from the presenter. These comments align with the quantitative pattern that harmony increased perceived self-expression fit and, indirectly, interpersonal affinity. The full summary is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

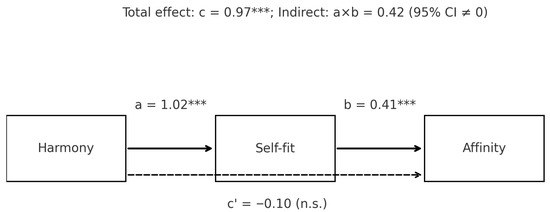

5.6. Mediation Analysis

Regression-based mediation analyses tested whether self-expression fit explained the link between Harmony and Affinity. As summarized in Figure 6, Harmony significantly predicted affinity in the total model (, ). When self-expression fit was added, the direct effect of Harmony became nonsignificant (, ), while the path from self-expression fit to affinity remained significant (, ). Bootstrapped confidence intervals for the indirect effect excluded zero, indicating that self-expression fit fully carried the effect of Harmony on affinity. This mediation pattern confirms H2. Note that the total effect (c) estimates the overall association between Harmony and Affinity, whereas the direct effect () estimates the residual association after accounting for the mediator (self-expression fit). Therefore, it is expected that can shrink (and occasionally change sign) when the mediator captures most of the shared variance between the predictor and outcome. In our data, the non-significant together with a bootstrap-supported indirect effect indicates that Harmony influences Affinity primarily through self-expression fit, rather than through an additional direct pathway.

Figure 6.

Mediation model depicting the relationship between harmony, self-expression fit, and interpersonal affinity. Solid arrows indicate significant standardized paths (, , *** ), whereas the dashed arrow indicates a non-significant direct path (, n.s.). The total effect was , and the indirect effect was significant (bootstrap 95% CI excluded zero), confirming H2.

The corresponding standardized coefficients and significance levels for the mediation analysis are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Mediation summary with standardized coefficients. The indirect effect (a × b) was significant by bootstrap CI.

5.7. Exploratory Analyses

Exploratory comparisons showed that warm–warm avatar–text pairs produced the highest affinity scores (around 4.2 on a 5-point scale), while reserved–reserved pairs yielded the lowest (around 1.9). Cross-pair conditions fell in between. Additional analyses of attention, memory, and preference subscales revealed higher attention ratings than memory or preference, (, , ).

5.8. Robustness and Additional Checks

Results were stable after excluding low-attention trials and after subject-wise z-normalization. Alternative composite definitions that dropped one affinity item at a time did not change the pattern of significance. Mixed-effects models with random slopes for Harmony, where identifiable, yielded qualitatively similar estimates to the ANOVA effects.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

The results confirm H1: Harmony between avatar and text enhances both self-expression fit and affinity. These effects align with the Proteus effect and with the hyperpersonal model, which highlights the amplification of impressions through coherent multimodal cues. Mediation analyses supported H2 by showing that self-expression fit explained the effect of harmony on affinity. In addition, the strong association between Harmony and perceived congruence indicates that perceived congruence functions as a proximal indicator of the harmony manipulation. Because perceived congruence and Harmony exhibited tightly aligned patterns across conditions, using Harmony as the independent variable in the mediation model is justified; Harmony effectively captures the same variance that would otherwise be modeled through perceived congruence. This supports the interpretation that Harmony is an appropriate operational variable for testing the hypothesized pathway. The descriptive pattern suggested larger harmony effects in more immersive contexts; however, the Harmony × Session interaction was not significant (Table 6). Therefore, H3 was not supported and is treated as exploratory. Importantly, the mediation results consistently indicate full mediation for H2, whereas immersion-related moderation (H3) is treated as exploratory, as no significant Harmony × Session interaction was observed in the current dataset.

From a theoretical perspective, these findings extend personality impression research by demonstrating that text cues embedded in avatars function similarly to visual appearance cues [6,21]. Harmony may work by increasing perceptual fluency, which enhances judgments of authenticity. Moreover, the results suggest that avatar–text harmony can be seen as a special case of the Gestalt principles, where the whole impression exceeds the sum of parts [22]. Presence-based models in virtual environments [18,19] also predict stronger consequences under higher immersion.

While our theoretical motivation predicted stronger cross-modal coupling under higher immersion, the present data do not provide confirmatory evidence for moderation by immersion. The observed descriptive trend should not be interpreted as establishing that immersion strengthens the Harmony pathway. Instead, it suggests a plausible direction for follow-up studies with larger samples and designs optimized for detecting interactions (e.g., more trials per cell and a priori power analysis for Harmony × Session effects).

From a practical design standpoint, platforms could implement adaptive systems that harmonize text style with avatar appearance (e.g., palette-aware defaults and accessibility-aware contrast), with user controls to lock/relax harmony for emphasis.

6.2. Limitations and Future Work

The sample size () was modest and limited to university participants. However, the study employed a tightly controlled within-subject design with twelve experimental conditions, which increases statistical power relative to between-subject designs. In addition, perceived congruence was assessed using a single-item manipulation check in the present study. Although this approach was sufficient to verify that the harmony manipulation was noticed, future studies will implement a short multi-item congruence scale (2–3 items) with reliability indices (e.g., Cronbach’s or McDonald’s ) to better capture perceived harmony and to further separate manipulation checks from mechanistic mediators. The present results therefore establish internal validity and mechanism-level effects rather than population-level prevalence. Larger and more diverse samples will be required to test demographic moderation (e.g., age, gender, VR experience) and improve generalizability. Additionally, perceived congruence was assessed using a single-item manipulation check (“The text matches the avatar”; Table 4), which does not allow reliability estimation. Future work should adopt a short multi-item congruence scale (e.g., 2–3 items) and report internal consistency (e.g., Cronbach’s or McDonald’s ), further clarifying the separation between manipulation checks and mechanistic mediators to prevent over-interpretation. Although we collected structured post-experiment qualitative interviews from all participants, the qualitative component was exploratory in nature and based on a modest sample size. The interviews were intended to complement the quantitative findings by providing contextual explanations for perceived harmony and impressions, rather than to serve as an independent qualitative analysis. Future work should employ richer qualitative protocols (e.g., longer interviews, open-ended responses, or mixed-method designs) with larger and more diverse samples to further validate and extend the present findings. The qualitative interview component is exploratory and based on a modest sample; future work should replicate with larger and more diverse samples and report more systematic qualitative analyses.

Manipulations focused on color, font, and tone; expanding to voice prosody, gesture, and movement would broaden the test of harmony. Longitudinal studies could assess persistence and adaptation.

6.3. Conclusions

Harmony between avatar appearance and on-avatar text significantly enhances both self-expression fit and interpersonal affinity in social VR. Congruence supports users in feeling authentic and fosters positive impressions among others.

6.4. Contribution Recap

This article (i) formalizes a theory-driven account linking avatar–text harmony to interpersonal outcomes via self-expression fit; (ii) isolates harmony with jointly controlled color, font, and tone; (iii) demonstrates robust effects across immersion levels using ANOVA, mixed-effects models, and mediation with bootstrap inference; and (iv) translates findings into design guidance for metaverse interfaces.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/informatics1010000/s1, Supplementary Materials: Interview_ Results_Summary_EN.xlsx, Post_Experiment_Congruence_Evaluation_EN.csv, and Avatar_ Attention_Questionnaire_EN.csv.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G.; methodology, Y.G.; formal analysis, Y.G.; investigation, Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.G., T.N., K.H. and S.S.; visualization, Y.G.; supervision, T.N., K.H. and S.S.; project administration, Y.G.; funding acquisition, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Electro-Communications (H25019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. A written informed consent form was distributed to all participants in accordance with the approved ethics protocol, and each participant provided signed consent prior to participation.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized quantitative data and analysis scripts supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request. Summary files of the structured qualitative interviews are provided as Supplementary Materials. The original Japanese questionnaire items and full qualitative interview responses are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request due to ethical and privacy considerations.

Acknowledgments

We thank colleagues and student participants at the University of Electro-Communications for their support with pilot testing and study logistics. All individuals acknowledged here provided their consent.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yee, N.; Bailenson, J.N. The Proteus Effect: The Effect of Transformed Self-Representation on Behavior. Hum. Commun. Res. 2007, 33, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, J.B. Computer-Mediated Communication: Impersonal, Interpersonal, and Hyperpersonal. Commun. Res. 1996, 23, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Ratan, R.A.; Foxman, M.; Meshi, D.; Liu, H.; Hales, G.E.; Lei, Y.S. An Avatar’s Worth in the Metaverse Workplace: Assessing Predictors of Avatar Customization Valuation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 158, 108309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Juvrud, J. Gender Expression and Gender Identity in Virtual Reality: Avatars, Role-Adoption, and Social Interaction in VRChat. Front. Virtual Real. 2024, 5, 1305758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, S.E. Forming impressions of personality. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1946, 41, 258–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Wan, Z.; Xia, Q.; Feng, Y.; Gu, W.; Yang, L.; Zhou, Z. Fairy Tale Situation Test for Implicit Theories of Personality. Am. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 9, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.; Maier, M.; Moller, A.; Friedman, R.; Meinhardt, J. Color and Psychological Functioning: The Effect of Red on Performance Attainment. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2007, 136, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, K.L.; Rauh, C. The Influence of the Avatar on Online Perceptions of Anthropomorphism, Androgyny, Credibility, Homophily, and Attraction. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2005, 11, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Kim, H.K. My avatar and the affirmed self: Psychological and persuasive implications of avatar customization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 112, 106446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aseeri, S.; Interrante, V. The influence of avatar representation on interpersonal communication in virtual social environments. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2021, 27, 2608–2617. [Google Scholar]

- Fabri, M.; Moore, D.J.; Hobbs, D.J. Designing avatars for social interactions. In Animating Expressive Characters for Social Interaction; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Koda, T.; Ishida, T.; Rehm, M.; André, E. Avatar culture: Cross-cultural evaluations of avatar facial expressions. AI Soc. 2009, 24, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.A.; Horgan, T.G.; Murphy, N.A. Nonverbal Communication. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepperle, D.; Purps, C.; Deuchler, J.; Bruder, G. Aspects of visual avatar appearance: Self-representation, display type, and uncanny valley. Vis. Comput. 2022, 38, 1227–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekdahl, D.; Osler, L. Expressive Avatars: Vitality in Virtual Worlds. Philos. Technol. 2023, 36, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, J.T.; Dunham, P.J. Impression formation in computer-mediated communication revisited: An analysis of the breadth and intensity of impressions. Commun. Res. 2001, 28, 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.D.; Chaparro, B.S.; Fox, D. Perception of Fonts: Perceived Personality Traits and Uses. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 16–20 October 2006; Volume 50, pp. 1277–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M. Place Illusion and Plausibility Can Lead to Realistic Behaviour in Immersive Virtual Environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2009, 364, 3549–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biocca, F. The Cyborg’s Dilemma: Progressive Embodiment in Virtual Environments. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 1997, 3, JCMC324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meta. Meta Platforms Inc.: Oculus Release Notes. 2021. Available online: https://developer.oculus.com/ (accessed on 4 January 2026).

- Tshivhase, M. On the possibility of authentic self-expression. Communicatio 2015, 41, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertheimer, M. Untersuchungen zur Lehre von der Gestalt II. Psychol. Forsch. 1923, 4, 301–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.