Abstract

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure has gained global prominence, yet its implementation in emerging markets particularly in environmentally intensive sectors remains fragmented. In Indonesia’s energy industry, ESG transparency still struggles to meet rising global expectations, especially amid increased foreign investment flows and sustainability demands following the country’s G20 presidency. While prior research has separately examined financial performance and ownership structure, fewer studies have explored their combined impact on ESG disclosure within this institutional context. This study investigates how financial risk indicators and ownership composition influence ESG disclosure levels among publicly listed energy firms in Indonesia during the 2020–2024 period. Drawing on 98 firm-year observations, ESG performance is measured using the Nasdaq ESG Reporting Guide, and multiple linear regression is used to assess the influence of return on assets, liquidity, and various ownership types (managerial, institutional, and foreign), controlling for firm age and COVID-19 impact. The findings reveal that institutional ownership significantly enhances ESG disclosure, while other predictors such as return on assets, liquidity, managerial, and foreign ownership show no meaningful effect. The results underscore the role of institutional investors as key drivers of ESG adoption, offering insights into how ownership structures shape sustainability reporting in a high-impact sector of an emerging economy.

1. Introduction

In recent years, financial markets around the world have increasingly recognized the importance of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors in shaping investment decisions (Almeyda and Darmansya 2019). ESG considerations have emerged as critical benchmarks for both institutional and retail investors in assessing corporate sustainability and risk exposure. This shift has prompted companies to strengthen their ESG profiles, driven by the need to meet stakeholder expectations and secure long-term capital. Today, investment institutions such as asset managers and pension funds routinely integrate ESG performance into their decision-making processes.

Many scholars now recognize that ESG is not merely a matter of social conscience, but is closely tied to an organization’s financial health and risk management (Kim and Li 2021). The Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX) has responded by launching the ESG Leader Index, designed to highlight firms that demonstrate strong ESG practices alongside financial stability and market liquidity. Within this framework, the energy sector stands out not only as a key pillar of Indonesia’s resource-driven economy but also as a major source of environmental pressure. In 2019 alone, 11 oil and gas companies were sanctioned for environmental violations (Amelia 2019), reinforcing public perception that energy firms often conflict with sustainable development goals (Baraputri 2023).

ESG has increasingly served as a strategic tool for managing these risks, providing transparency around a firm’s social, ethical, and environmental responsibilities (Kim and Li 2021). In Indonesia, ESG disclosures are found to increase firm visibility and legitimacy, especially in non-financial sectors (Chairani and Zuraida 2021). Cross-country studies affirm that board independence and sustainability reporting positively influence ESG transparency (N. Elafify 2021), while in India, ESG performance correlates with firm efficiency and executive compensation (Lunawat and Lunawat 2022; Rath et al. 2020).

Ownership structure has likewise been recognized as an important factor shaping firms’ ESG disclosure practices. While managerial ownership may diminish transparency to protect self-interests (Juhmani 2013), institutional ownership is often linked with enhanced compliance and governance oversight (Velte 2020). Foreign investors, guided by global sustainability standards, often press firms for greater transparency in their ESG disclosures.

The COVID-19 pandemic acted as a major shock to market dynamics, heightening the importance of firm-level risk management and organizational resilience. Sembiring (2023) demonstrate that anomalies in market behavior during the pandemic were influenced by firm size and risk, suggesting ESG disclosures may similarly respond to external crises. Similarly, Istianingsih and Suraji (2020) underline the role of strategic resource management and intellectual capital in improving business outcomes under challenging conditions.

Recent studies in the BMEE (Business, Management, Economics, and Engineering) literature have increasingly turned their focus to the link between financial risk and sustainability. González-Bueno et al. (2025) model portfolio optimization under ESG and volatility considerations in Colombia, revealing the interdependence between financial risk exposure and ESG frameworks. Survilaitė-Venskienė and Stankevičienė (2024) analyze sectoral credit risk under ESG disclosure regimes, finding that ownership concentration moderates disclosure sensitivity. Kozhuharov et al. (2024) demonstrate that foreign ownership and institutional pressure are key triggers for ESG transparency, particularly in transitional economies. Building on this literature, the present study examines whether financial risk and ownership structurenamely managerial, institutional, and foreign ownership, significantly influence ESG disclosure in Indonesia’s energy sector, where regulatory enforcement and sustainability standards are still evolving.

Although research on ESG disclosure has expanded considerably, most prior studies have tended to examine financial risk and ownership structure as separate dimensions rather than integrating them into a unified explanatory model. Much of the existing scholarship has concentrated on governance mechanisms, board attributes, or the adoption of sustainability reporting frameworks, leaving the interaction between financial vulnerabilities and ownership configurations relatively underexplored (M. G. Elafify 2021; Velte 2020), while neglecting operational indicators such as ROA or liquidity that reflect firm-level financial risk. Moreover, prior research has seldom situated ESG behavior within the realities of high-risk environments such as emerging markets, especially in sectors that are environmentally sensitive like energy. Even fewer studies have explicitly focused on the post-pandemic context, a period in which financial pressures and stakeholder scrutiny escalated in tandem. Accordingly, a gap persists in understanding how financial distress and ownership structures jointly shape ESG disclosure when examined through the lens of legitimacy theory. This study addresses that gap by employing ROA and the Current Ratio as proxies for financial risk, and by analyzing their interplay with managerial, institutional, and foreign ownership, using Nasdaq ESG indicators for Indonesian energy firms from 2020 to 2024. In doing so, the research offers a novel contribution by framing ESG disclosure as a strategic response to both governance pressures and financial vulnerabilities within a transitioning economy.

This study contributes timely empirical evidence on the dynamics of ESG disclosure in emerging markets, contexts often characterized by institutional fragility and heightened financial risk that remain insufficiently examined in the literature. By incorporating ownership structures alongside firm-specific risk factors, the research generates strategic insights that are particularly valuable for both investors and regulators seeking to navigate environments marked by volatility and limited transparency.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Legitimacy Theory

Legitimacy Theory posits that organizations continually seek to ensure that they operate within the bounds and norms of their respective societies. As articulated by Suchman (1995), legitimacy is “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions.” From this perspective, firms engage in voluntary disclosure, including on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues as a way to justify their continued existence and secure social acceptance. In environments marked by growing public scrutiny, rising regulatory demands, and more vocal stakeholder activism, ESG reporting serves not merely as compliance but as a deliberate strategy to manage legitimacy and demonstrate alignment with evolving societal expectations. According to legitimation theory, firms operate under a “social contract” with society, whereby their continued existence depends on acting within the bounds and norms of societal expectations (Shocker and Sethi 1974).

Legitimacy Theory offers a robust conceptual lens for understanding how financial risk, ownership structure, and firm characteristics shape ESG disclosure practices. Firms with substantial institutional or foreign ownership often encounter heightened demands for accountability and transparency. To safeguard their legitimacy in the eyes of global investors, such firms are more likely to strengthen ESG reporting, positioning disclosure as both a compliance mechanism and a strategic response to stakeholder expectations (Al Amosh and Khatib 2022). Similarly, older firms generally enjoy greater public visibility and long-standing relationships with stakeholders, which heighten their exposure to legitimacy pressures and motivate them to engage in more consistent ESG disclosure (Yustin and Suhendah 2023). From a financial perspective, firms facing distress or liquidity constraints may turn to ESG disclosure as a strategic signal to restore trust and reassure stakeholders, reflecting underlying legitimacy motives (Al-Matari 2025). Therefore, ESG transparency is not only a reflection of internal governance but also a response mechanism to societal expectations in pursuit of sustained legitimacy.

2.2. Institutional Theory

This study is grounded in both legitimacy theory and institutional theory to explain the dynamics of ESG disclosure in Indonesia’s energy sector. While legitimacy theory suggests that firms disclose ESG information to gain social approval and ensure organizational survival, this perspective alone may not fully capture the institutional complexity within an emerging market context. Therefore, we incorporate institutional theory, as introduced by (DiMaggio and Powell 1983), which emphasizes that organizations conform not only due to efficiency but also because of institutional pressures such as regulations, professional norms, and cultural expectations.

Institutional theory helps contextualize why firms in Indonesia may behave differently compared to those in developed markets, particularly when responding to ESG demands. For instance, foreign ownership may not significantly influence ESG disclosure in Indonesia due to weak enforcement of global ESG standards or the limited influence of foreign stakeholders in decision-making processes. Institutional ownership, on the other hand, may serve as a stronger source of coercive or normative pressure, encouraging ESG compliance aligned with international best practices. Managerial ownership might reflect internal priorities rather than institutional expectations, which could explain its weak association with ESG transparency. Furthermore, financial risk indicators such as return on assets and liquidity can be interpreted within institutional settings, where firms under higher scrutiny or regulatory pressure may use ESG disclosure as a tool to signal long-term resilience and reduce legitimacy gaps in less mature markets.

2.3. Climate-Driven Financial Risk in the ESG Context

Financial risk refers to the possibility that a firm’s financial performance may deviate from expectations due to factors such as market volatility, leverage, or liquidity pressures. In today’s sustainability context, however, financial risk extends beyond these traditional measures to include exposures linked to environmental regulation, social demands, and governance shortcomings. As stakeholders pay closer attention to ESG performance, financial risk is shaped not only by conventional indicators like earnings volatility but also by the potential costs of non-compliance or involvement in ESG-related controversies (Shi and Dow 2025). Financial performance indicators such as Return on Assets (ROA) are widely employed as proxies for financial risk, particularly in empirical studies that examine how a firm’s operational and strategic vulnerabilities affect its stability (Qayoom and Chisti 2025). Firms facing greater financial risk are often more motivated to disclose ESG information, using it both as a means of safeguarding their reputation and as a tool for managing risk (Tian and Zhao 2025). Additionally, in developing countries that have weak capital structures, strong ESG transparency would be considered a strategic response to high risk premiums (Survilaitė-Venskienė and Stankevičienė 2024). Moreover, liquidity measures such as the current ratio are increasingly viewed as important proxies for financial risk, especially in evaluating a firm’s capacity to meet short-term obligations. Recent research indicates that, when considered alongside ESG disclosure, the current ratio offers meaningful insights into a company’s financial resilience and its broader risk mitigation strategies (Rosalika et al. 2024).

Environmental pressures, including climate-related disasters, regulatory shifts toward sustainability, and rising stakeholder expectations, are increasingly shaping firms’ financial risk exposure. Research shows that climate risk can both undermine a company’s financial stability and directly affect its ESG performance. For instance, Erhemjamts et al. (2022) found that climate-related sentiment significantly affects ESG scores and financial outcomes in U.S. banks. Similarly, Naseer et al. (2023) demonstrated that climate risk and financial flexibility are both key drivers of ESG performance and firm value. Yin et al. (2024) provided evidence from China showing that firms exposed to climate risk tend to enhance ESG disclosure as a strategic response. Moreover, (Yang and Shi 2024) emphasized that integrating ESG considerations is essential to optimize financial outcomes under climate-related uncertainties.

2.4. Ownership Structure

Alternative perspectives highlight that a firm’s ownership structure, specifically who its shareholders are, plays a critical role in shaping corporate transparency and governance. High levels of managerial ownership can foster entrenchment and information concealment, particularly when executives hold significant control, thereby reducing their incentives to voluntarily disclose ESG information (Juhmani 2013). On the other hand, the institutional ownership typically applies positive governance pressure, inducing firms to embrace transparent practices for satisfying investors’ and regulatory requirements (Velte 2020). In particular, firms with foreign ownership often demonstrate higher levels of ESG compliance, as international investors typically demand adherence to global sustainability standards (Kozhuharov et al. 2024). This association between concentrated ownership and ESG performance has also been found to differ between industries and governance systems, emphasising the need for context-specific examination when considering the impact of ownership on disclosure practices (Dasilas and Karanović 2025). Firms with dispersed ownership structures or noncontrolling blockholders tend to be more responsive to stakeholder demands and are therefore more likely to align their disclosures with established sustainability frameworks.

2.5. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure

ESG disclosure represents a company’s commitment to transparency regarding its environmental impact, social responsibility, and governance practices. Beyond informing stakeholders, it functions as a tool to build legitimacy and reduce information asymmetry (da Cunha et al. 2025). ESG reporting has evolved from a voluntary act of corporate citizenship into a strategic necessity, particularly within the expanding landscape of global frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), and sector-specific indices like the Nasdaq ESG Disclosure Standards. High-quality ESG disclosure not only lowers the cost of capital and strengthens investor confidence but also signals a firm’s competence in managing risk (Jafar et al. 2024). While firms in high-impact industries such as energy face mounting pressure to disclose ESG information, the extent of their actual disclosure is often shaped by internal governance, financial conditions, and patterns of external ownership. To explain why companies report ESG information in ways that align with societal expectations and mitigate reputational risks, scholars frequently draw on stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory (Chairani and Zuraida 2021; N. Elafify 2021). In less developed economies, ESG transparency is often viewed as a way for firms to differentiate themselves in increasingly competitive markets, where regulatory enforcement remains uneven but market pressures continue to intensify.

In recent years, ESG disclosure practices have undergone a global transformation, shaped by regulatory reforms and evolving investor expectations. Within the European Union, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) has introduced more comprehensive and comparable sustainability requirements across member states. Central to this framework is the principle of double materiality, supported by the integration of the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), which together aim to enhance transparency and accountability in corporate reporting (Scamans 2024). Similarly, global frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) have become reference points for firms seeking legitimacy and transparency in ESG reporting (Bednárová 2025). These frameworks are designed to standardize reporting and enable firms to convey their ESG risks and strategies to increasingly discerning stakeholders. Yet, in emerging economies such as Indonesia, ESG disclosure tends to remain voluntary and fragmented. This regulatory gap highlights the importance of examining how firms navigate institutional and market pressures within such environments, positioning the Indonesian energy sector as a compelling case for inquiry through the lens of legitimacy theory. Integrating both global and local perspectives offers a more nuanced understanding of ESG practices across diverse regulatory settings.

2.6. Financial Risk on ESG Disclosure

Financial risk refers to the potential instability in an organization’s financial condition, particularly in relation to liquidity, profitability, and solvency. Elevated financial risk can trigger reputational damage, erode investor confidence, and increase the cost of borrowing. To mitigate these challenges, companies often employ ESG disclosure as a strategic signaling mechanism, aimed at reducing risk perceptions and strengthening transparency (Shi and Dow 2025). Stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory suggest that when firms face financial risk, they have a strong incentive to demonstrate social and environmental responsibility. By doing so, companies aim to preserve their legitimacy in the eyes of stakeholders and strengthen their ability to attract long-term capital (da Cunha et al. 2025).

Qayoom and Chisti (2025) found that firms facing higher financial risk are more inclined to disclose greater amounts of ESG information as a way to build trust with stakeholders and reduce the perceived opacity of their operations. It is also in accordance with Tian and Zhao (2025) that companies with a high level of risk exposures to climate change and financial risk manage to increase their ESG behaviour as part of their integrated overall risk management. Disclosure functions as a cushion against volatility by enabling stakeholders to develop a clearer and more accurate perception of risk. In this light, it is reasonable to propose that higher financial risk may drive firms to increase the extent of their ESG disclosure as a means of reinforcing transparency and investor confidence.

Liquidity, measured by the current ratio, is a critical indicator of financial risk as it reflects a firm’s short-term solvency and operational resilience. Recent research suggests that firms with stronger liquidity positions tend to provide more extensive ESG disclosures, using them as a proactive strategy to build investor confidence and reduce the perceived risk of financial distress (Khalid et al. 2022; Sunani et al. 2024). From the perspective of institutional theory, this behavior can also be seen as a strategic response to institutional pressures, both formal (regulatory requirements) and informal (investor and societal expectations). Firms with higher liquidity are better equipped to meet these pressures by adopting more comprehensive ESG disclosures, which serve not only to legitimize their operations but also to align with broader institutional norms regarding corporate responsibility and transparency.

H1.

Financial risk (ROA) has a positive effect on the level of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) disclosure.

H2.

Financial risk (CR) has a positive effect on the level of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) disclosure.

2.7. Managerial Ownership on ESG Disclosure

Managerial ownership refers to the proportion of shares held by a firm’s internal managers, which may influence ESG disclosure practices. From the perspective of agency theory, managerial ownership is expected to align the interests of managers and shareholders, thereby enhancing transparency and reducing opportunistic behavior in ESG reporting (Sunani et al. 2024). Accordingly, higher managerial ownership may reduce agency conflicts and encourage more comprehensive disclosure practices. Managerial stock ownership can motivate executives to disclose more ESG information as a way to maintain investor confidence, secure long-term financing, and minimize potential agency conflicts.

More recent studies question the neutrality of managerial ownership and even suggest a potential negative impact on the quality of ESG disclosure. For example, (Bayong et al. 2024) found that in emerging markets, managerial ownership exerts a stronger influence on ESG disclosure scores compared to blockholders or even state directorship. Similarly, Sunani et al. (2024) found that the higher managerial ownership firms are likely to reduce financing disregard by proactively improving ESG disclosure and reducing capital costs. These results indicate that managerial ownership functions as an internal governance mechanism that promotes ESG transparency, especially in contexts where external regulatory oversight is still limited or emerging. Building on prior research, the third hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H3.

Managerial ownership has a significant positive effect on the level of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) disclosure.

2.8. Institutional Ownership on ESG Disclosure

Institutional ownership is widely regarded as an important factor influencing a firm’s environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure. Firms with higher levels of institutional shareholding are typically subject to greater scrutiny and stronger stakeholder pressure, which in turn fosters a stronger commitment to transparency. Empirical evidence suggests that institutional investors tend to support sustainable practices and demand higher ESG performance from firms they invest in (Khalid et al. 2022). Furthermore, Martínez-Ferrero and Lozano (2021) highlight a nonlinear relationship between institutional ownership and ESG performance, particularly in emerging markets, where an increase in institutional ownership initially improves ESG outcomes up to a certain threshold. These findings suggest that institutional investors can play a crucial role in encouraging firms to provide more comprehensive ESG disclosure (Velte 2020; Jafar et al. 2024; Kozhuharov et al. 2024). It is important to note that institutional ownership, particularly by financial institutions, is subject to oversight from regulatory authorities such as the Financial Services Authority (OJK) in Indonesia. This creates a dual-layered obligation for firms: they must comply not only with general capital market regulations but also with the stricter standards imposed by financial industry oversight. Such dual compliance pressures encourage stronger ESG disclosure as part of a broader commitment to transparency and accountability. Building on prior research, the fourth hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H4.

A higher level of institutional ownership is associated with an increase in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure.

2.9. Foreign Ownership on ESG Disclosure

Research that examines the effect of foreign ownership on ESG disclosure was conducted by Ould Daoud Ellili (2020), showing that it has a significant and positive effect on ESG disclosure. This study’s results align with research conducted by (Al Amosh and Khatib 2022) that foreign ownership has an important role in ESG disclosure. ESG practices are largely shaped by international conventions, which emphasize the importance of sustainability standards. Accordingly, when a firm’s ownership structure includes foreign investors, it is expected that awareness and adoption of ESG practices will also increase. Foreign investors, particularly those from countries with stringent ESG frameworks, contribute not only financial capital but also governance expectations that reflect international standards. They frequently call for greater transparency and accountability as a way to reduce reputational and financial risks linked to weak ESG practices. As a result, firms with higher levels of foreign ownership are more inclined to adopt and disclose ESG-related initiatives to meet these expectations and secure long-term foreign investment. This mechanism illustrates how the presence of foreign shareholders can act as a channel for institutionalizing ESG disclosure practices. The positive relationship suggests that the greater the proportion of shares held by foreign investors, the higher the level of ESG disclosure. Drawing on prior studies, the fifth hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H5.

A higher level of foreign ownership is found to positively influence the extent of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure.

3. Research Method

For the period 2020–2024, this study employs secondary data obtained from the annual reports of energy companies listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX) to conduct a quantitative analysis. The energy sector was selected due to its considerable environmental impact and its critical role in ESG disclosure. Firms were identified through a purposive sampling method, with inclusion determined by specific eligibility criteria. This study covers the entire population of energy-sector firms listed on the IDX within the observation period, resulting in an initial sample of 103 firm-year observations. However, 5 firm-year observations were excluded due to missing or incomplete data, particularly the unavailability of key financial indicators or ESG-related disclosures in annual or sustainability reports. Additional exclusions were made for firms that were delisted during the period or presented extreme outliers that could bias regression estimates. Applying these criteria resulted in a final sample of 98 firm-year observations, comprising firms that were consistently listed and had publicly available, complete disclosures necessary for the analysis. This approach ensures the sample remains representative of the Indonesian energy sector while minimizing survivorship and selection bias.

This study examines the influence of ownership structure and financial risk, treated as independent variables, on the extent of ESG disclosure through multiple linear regression analysis. This analytical method is appropriate when the objective is to estimate the relationship between a single dependent variable and several independent variables simultaneously (Gujarati and Porter 2009; Wooldridge 2013). This method also enables the adjustment of potential confounding variables, allowing them to vary independently. The model is estimated using SPSS version 26.0, and the multiple regression equation is specified as follows:

The regression model in this study is designed to analyze how financial risk and ownership structure relate to ESG disclosure. In this framework, ESG disclosure (Y) serves as the dependent variable, while α0 represents the constant or intercept of the model. The study employs a multiple regression analysis approach, which is widely used in ESG-finance literature to examine the simultaneous effects of multiple explanatory variables (Hair et al. 2019). This statistical technique allows for controlling the influence of other variables in the model and detecting the unique contribution of each independent variable (e.g., ROA, CR, managerial ownership, institutional ownership, foreign ownership, etc.) to the variation in ESG disclosure. The use of multiple regression is particularly appropriate when the aim is to assess the net effect of several predictors while accounting for possible multicollinearity or confounding factors, both of which are common in ESG research (Velte 2020). Therefore, the model specification aligns with established quantitative standards in ESG disclosure studies, especially in emerging market contexts.

The independent variables include X1 (ROA) and X2 (CR) as proxies for financial risk, X3 (Managerial Ownership), X4 (Institutional Ownership), and X5 (Foreign Ownership). The control variables are X6, a dummy variable for the COVID-19 period (assigned a value of 1 for the years 2020 and 2021, and 0 otherwise), and X7 (Firm Age), which captures period effects. The coefficients β1 to β7 denote the partial regression coefficients, which estimate the unique contribution of each independent variable to explaining variations in ESG disclosure. The error term (ε) captures the effect of other unobserved factors that are not explicitly included in the model.

As presented in Table 1, the variables in this study were operationalized using measurement approaches that are well established in prior research. The dependent variable, ESG disclosure, is evaluated using 30 indicators adapted from the Nasdaq ESG Reporting Guide, with an equal focus on environmental, social, and governance dimensions. Each indicator is assessed using a dichotomous scale, assigning a score of 1 when the item is disclosed and 0 when it is not. The main independent variable, financial risk, is proxied by Return on Assets (ROA), calculated as a percentage ratio of net income to total assets (Kumar and Firoz 2022).

Table 1.

Variable Measurements.

Ownership structure is assessed through three key indicators. The first is institutional ownership, which refers to the proportion of a firm’s shares that are held by institutional investors (Velte 2020); managerial ownership, representing the percentage of shares owned by internal management (Al Amosh and Khatib 2022); and foreign ownership, calculated as the proportion of shares held by non-domestic investors (Al Amosh and Khatib 2022). To account for the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, a control variable is included in the model. This variable is represented by a dummy code, where the year 2020 is assigned a value of 1 and all other years are assigned a value of 0 (Tampakoudis et al. 2021). Firm age is measured as the number of years from the company’s establishment year up to the year of observation (Abdi et al. 2021).

Based on Table 2 shown above, the ESG disclosure index used in this study is adapted from the Nasdaq (2019), which consists of 30 indicators equally distributed across three dimensions: environmental, social, and governance. Each ESG dimension is represented by ten disclosure items that serve as concrete indicators of corporate practices. For the environmental aspect, these include greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, energy intensity, and climate risk mitigation. The social aspect covers measures such as CEO pay ratio, gender diversity, and respect for human rights. Meanwhile, governance indicators encompass board independence, ethics and anti-corruption policies, as well as the use of external assurance. Taken together, these indicators provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating corporate sustainability efforts and offer a structured basis for assessing the level of ESG transparency across firms.

Table 2.

ESG Itmes Disclosure from Nazdaq 2019.

4. Result and Discussion

This section presents and discusses the empirical findings derived from the regression analysis. The discussion is structured around each independent variable and its relationship to ESG disclosure, as tested in the proposed hypotheses. Descriptive statistics and visual illustrations are also provided to support interpretation and contextualize the results within the Indonesian energy sector. The analysis begins with an overview of ESG disclosure trends over the study period.

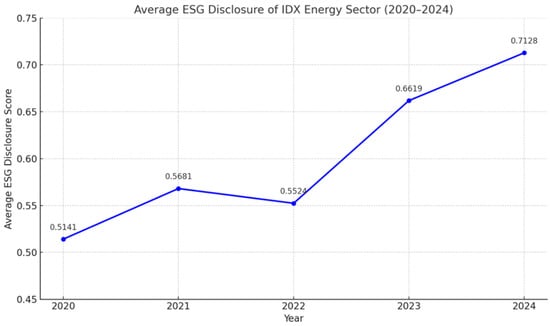

Figure 1 illustrates the upward trend in average ESG disclosure scores among IDX-listed energy sector firms over the period 2020–2024. The level of disclosure rose consistently from 0.5141 in 2020 to 0.7128 in 2024, reflecting a strengthening commitment to transparency in environmental, social, and governance practices. A significant increase is evident between 2022 and 2023, suggesting that regulatory pressures, market expectations, or stronger stakeholder engagement may have prompted firms to enhance their reporting practices. This steady progress signals a positive movement toward alignment with global ESG standards, although full convergence will likely depend on stronger enforcement mechanisms and more effective incentives.

Figure 1.

Average ESG Disclosure of IDX Energy Sector (2020–2024).

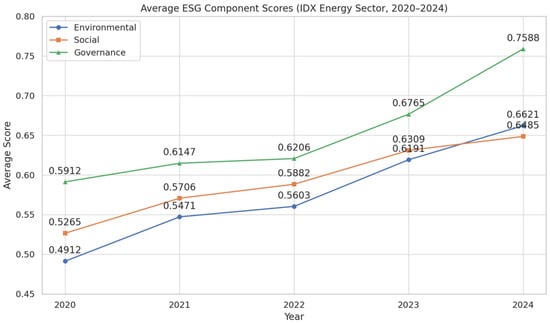

Figure 2 illustrates the annual average scores of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) disclosure among energy sector firms listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX) from 2020 to 2024. The results show a clear upward trend across all three dimensions, reflecting steady progress in sustainability reporting. Governance stands out as the strongest component each year, increasing from 0.59 in 2020 to 0.76 in 2024, highlighting the sector’s consistent emphasis on structural oversight. Meanwhile, both Environmental and Social scores show an upward trend, with Environmental disclosure rising notably after 2022. These patterns suggest a growing awareness of sustainability issues and a stronger institutional alignment with global ESG standards in Indonesia’s energy sector.

Figure 2.

Annual Average Scores of ESG Disclosure Components in IDX-Listed Energy Firms, 2020–2024.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Based on the descriptive statistics in Table 3, the sample includes 98 observations. Return on Assets (ROA) has an average of 0.098 with a standard deviation of 0.1193. The first quartile is 0.0239 and the third quartile is 0.1079, suggesting modest profitability that is largely concentrated within a relatively narrow range. The current ratio averages 0.667 with a standard deviation of 1.0815. The first quartile is 0.0163 and the third quartile is 1.2180, reflecting considerable variation in firms’ liquidity positions. Managerial ownership is relatively low, averaging 0.045 with a standard deviation of 0.1508. By contrast, institutional ownership is higher, with a mean of 0.356, a standard deviation of 0.3056, and a third quartile value of 0.6118. Foreign ownership averages 0.201 with a standard deviation of 0.2843, indicating considerable variation across firms. On average, firms in the sample are 32.37 years old, with a standard deviation of 12.429. The first quartile is 20 years and the third quartile is 42 years, indicating that most firms are relatively mature. ESG disclosure has a mean score of 0.583 with a standard deviation of 0.1252. The first quartile is 0.5000 and the third quartile is 0.6667, suggesting that most firms report between half and two-thirds of the ESG indicators.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics.

4.2. Correlation Pearson

As shown in the Spearman correlation results in Table 4, several variables display significant relationships with ESG disclosure. The current ratio, for instance, has a negative correlation with ESG reporting (ρ = −0.189, p = 0.063), significant at the 10% level. This suggests that firms with weaker liquidity positions are more likely to increase their ESG disclosure, potentially as a way to compensate for financial vulnerability. Managerial ownership shows a negative correlation (ρ = −0.180, p = 0.076), significant at the 10% level, indicating that higher insider ownership may lessen the motivation for transparent ESG reporting. In contrast, institutional ownership has a positive correlation with ESG disclosure (ρ = 0.341, p = 0.001), significant at the 1% level, highlighting the influential role of institutional investors in promoting greater transparency. The COVID-19 dummy variable exhibits a strong negative correlation (ρ = −0.352, p < 0.01), indicating that firms scaled back their ESG disclosure during the pandemic period. In contrast, firm age shows a strong positive correlation with ESG disclosure (ρ = 0.501, p < 0.01), suggesting that older firms are more inclined to report on sustainability, likely due to heightened stakeholder scrutiny and their greater organizational maturity.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics.

4.3. Coefficient of Determination (R2) Model

Since this study employs multiple linear regression analysis, the Adjusted R Square value is reported. The table below presents the results of the test for the coefficient of determination.

As shown in Table 5, the Adjusted R Square value is 0.368, meaning that 36.8% of the variation in ESG disclosure, the dependent variable, can be explained by the independent variables ROA, CR, managerial ownership, institutional ownership, foreign ownership, the COVID-19 dummy, and firm age. The remaining 63.2% is influenced by other factors not examined in this study.

Table 5.

Deteminance (R2) Model.

Model Fit (Test F). The results of testing the hypothesis using the F test can be seen in the following table.

Based on Table 6, it can be seen that the significance value is 0.000. This indicates that 0.00 < 0.05. It can therefore be concluded that the independent variables ROA, CR, managerial ownership, institutional ownership, foreign ownership, the COVID-19 dummy, and firm age collectively influence the dependent variable, namely ESG disclosure. Moreover, the variables used in this study are deemed appropriate and fit for inclusion in the research model.

Table 6.

F Test.

4.4. Partial Test Results (t Test)

All classical assumption tests, including normality, heteroskedasticity, multicollinearity, and autocorrelation, were performed to ensure that the regression model meets the criteria of Best Linear Unbiased Estimators, confirming the reliability and validity of the results. The results of testing the hypothesis using the partial coefficient test (t-test) can be seen in the following table.

Based on Table 7, the collinearity diagnostics reveal that all independent variables have VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) values ranging from 1.036 to 2.123, with tolerance values well above 0.10. These results confirm that multicollinearity is not a major issue in the regression model, as the VIF values lie well within the commonly accepted safe range of 1 to 10 for regression analysis (Hair et al. 2019). In sum, the explanatory variables employed in this study show no signs of problematic collinearity, meaning they can be considered reliable in explaining the variation in ESG disclosure without causing inflated standard errors.

Table 7.

t Test.

Based on Table 7, the regression results provide the following conclusions.Variable X1 (Return on Assets) has a significance p-value of 0.281, which is greater than 0.05, and a coefficient of 0.107. The findings show that ROA, used as a proxy for financial risk, does not exert a statistically significant influence on ESG disclosure. Similarly, the current ratio (X2), another measure of financial risk, is also insignificant (p = 0.422). Therefore, both Hypothesis 1 and 2 are not supported.

Variable X3 (Managerial Ownership) yields a significance value of 0.380, which is above the 0.05 threshold. Despite its negative coefficient (−0.070), the result is statistically insignificant, suggesting that managerial ownership has no meaningful effect on ESG disclosure. As a result, Hypothesis 3 is not supported.

Variable X4 (Institutional Ownership) shows a significance value of 0.033, which falls below the 0.05 threshold, along with a positive coefficient of 0.105. These results indicate that institutional ownership has a statistically significant positive influence on ESG disclosure. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is supported.

Variable X5 (Foreign Ownership) records a significance value of 0.556 with a coefficient of 0.030. Because the significance level is above the 0.05 threshold, the analysis indicates that foreign ownership has no meaningful effect on ESG disclosure. Accordingly, Hypothesis 5 is not supported.

The COVID-19 dummy variable (X6), employed as a control factor, shows a significance value of 0.000 with a coefficient of −0.085. This suggests that the occurrence of the pandemic year (2020) had a statistically significant negative effect on ESG disclosure among the firms studied. In contrast, firm age (X7), also included as a control variable, has a significance value of 0.000 with a coefficient of 0.003. This indicates that older firms are more likely to engage in ESG reporting, which may reflect their accumulated experience, organizational stability, and heightened stakeholder expectations.

4.5. Financial Risk on ESG Disclosure

The regression analysis reveals that financial risk, measured through return on assets (ROA) and the current ratio (CR), has no significant effect on ESG disclosure. This result contrasts with earlier studies suggesting that financially vulnerable firms are more inclined to disclose sustainability information as a way to manage external perceptions and pressures. For instance, Shi and Dow (2025) and da Cunha et al. (2025) emphasize that firms often utilize ESG disclosure as a strategic tool to mitigate reputational and financial risks during times of instability. Similarly, firms with higher financial and climate-related risk exposure tend to enhance their ESG transparency as part of integrated risk management strategies (Qayoom and Chisti 2025; Tian and Zhao 2025)

The divergence in findings may be explained by contextual factors. In emerging markets such as Indonesia, ESG frameworks are still underdeveloped, and market actors may not yet view ESG transparency as an effective tool for risk mitigation. Moreover, the financial distress experienced by the sampled firms may not have reached a level critical enough to trigger strategic ESG responses. Firms under financial strain are also likely to concentrate their limited resources on survival and core operations rather than on voluntary reporting. As a result, this study does not align with prior evidence, indicating that within Indonesia’s energy sector, financial risk alone is insufficient to drive ESG disclosure practices.

It is also important to acknowledge that another potential source of divergence lies in how financial risk is conceptualized and measured across studies. This study employs ROA and current ratio as proxies, reflecting profitability and liquidity dimensions, respectively. In contrast, prior studies often adopt broader constructs of financial risk, including financial vulnerability, reputational pressure, or exposure to climate-related uncertainty, which are conceptually closer to ESG-related legitimacy strategies. Therefore, the differences in findings may not necessarily indicate theoretical contradictions but rather stem from distinct measurement approaches. Recognizing this definitional gap strengthens the interpretability and nuance of the present results.

4.6. Managerial Ownership on ESG Disclosure

The regression results show that managerial ownership does not have a significant influence on ESG disclosure, a finding that is consistent with previous studies by Al Amosh and Khatib (2022), Juhmani (2013). Viewed through the lens of Legitimacy Theory, ESG disclosure serves mainly as a strategic response to external pressures and stakeholder expectations, rather than being shaped by internal ownership structures. In firms where managerial ownership dominates but public scrutiny and institutional oversight are limited, managers are less likely to regard ESG transparency as essential for maintaining legitimacy. This dynamic is especially evident in emerging markets such as Indonesia, where ESG regulations are still evolving and investor demand for non-financial disclosure remains uneven. In the absence of strong external incentives, legitimacy pressures are weak, and managerial ownership by itself does little to drive comprehensive ESG reporting. The descriptive statistics from this study further show that managerial ownership levels in the sample are relatively modest, which likely reduces its influence on strategic disclosure practices even further. Thus, the insignificant effect of managerial ownership indicates that ESG transparency in this setting is shaped more by external legitimacy pressures such as the presence of foreign investors, institutional shareholders, or evolving regulatory frameworks than by the equity stakes held by managers themselves.

In emerging markets such as Indonesia, where ESG enforcement remains in its early stages, managerial discretion often operates with limited oversight. Consequently, in the absence of formal ESG mandates or pressure from shareholders, managers may not view sustainability disclosure as a pressing concern. This implies that managerial ownership, when not reinforced by strong governance structures or aligned incentives, is unlikely to exert a meaningful influence on ESG transparency.

The sharp increase in ESG disclosure observed between 2022 and 2023 suggests that evolving domestic regulatory efforts and heightened stakeholder scrutiny may have begun to offset the effects of weak managerial oversight. This shift indicates that ESG transparency in Indonesia is likely shaped more by external institutional pressures such as compliance expectations and reputational concerns than by internal ownership structures alone. Future studies could further unpack these dynamics by differentiating between regulatory-driven disclosures and those influenced by ownership or investment characteristics.

4.7. Institutional Ownership on ESG Disclosure

The regression results indicate that institutional ownership exerts a significant positive influence on ESG disclosure, underscoring the pivotal role institutional investors play in fostering greater transparency within firms. This result is consistent with Velte (2020), who suggested that institutional investors (mutual funds, insurance companies, pension funds) are sensitive to external governance regulation and that these investors monitor more carefully firms that engage in E, S, and G practices. This finding is also consistent with prior studies that identify institutional ownership as a key driver of voluntary disclosure, given that institutional shareholders are bound by fiduciary duties and typically adopt a long-term investment horizon (Jafar et al. 2024; Kozhuharov et al. 2024). This finding aligns with foundational studies in the ESG-finance literature. Clarkson et al. (2008) emphasize that firms with greater environmental disclosure tend to be more responsive to stakeholder demands, particularly those from institutional investors. Dhaliwal et al. (2011) further demonstrate that institutional investors promote ESG transparency to reduce firms’ cost of capital. Supporting this, Friede et al. (2015) aggregate evidence from over 2000 empirical studies, reporting a predominantly positive relationship between ESG performance and financial outcomes. Together, these studies suggest that institutional investors act as key enablers of ESG disclosure, both through direct monitoring and via market-based incentives for greater transparency.

Moreover, the positive effect of institutional ownership found in our analysis aligns with the theoretical view that firms in highly regulated sectors act as channels through which policy expectations and stakeholder demands are transmitted, particularly in industries like energy, where environmental concerns are especially pressing. For institutional investors, the drive for ESG disclosure stems not only from regulatory compliance but also from its role as a strategic tool for managing risks and safeguarding long-term value creation. Firms with higher levels of institutional ownership tend to be more proactive in disclosing their ESG activities, which not only enhances their legitimacy but also strengthens their relationships with stakeholders, particularly in markets where sustainability performance has become increasingly critical.

These findings also carry broader implications for both regulatory and investment environments. Policymakers could leverage the role of institutional investors as catalysts for sustainable corporate behavior by formulating incentives or regulatory requirements that strengthen expectations for transparency. Similarly, investment strategies that embed ESG metrics can be more firmly institutionalized through mechanisms such as stewardship codes or sustainable finance regulations, thereby strengthening the alignment between capital allocation and environmental and social priorities. In this context, institutional ownership plays a dual role: it influences firm-level disclosure practices while also serving as a bridge that connects financial markets with regulatory aspirations for long-term ESG integration.

4.8. Foreign Ownership on ESG Disclosure

The test results indicate that foreign ownership does not exert a significant influence on ESG disclosure. This is contrary to the anticipation of previous research, such as Al Amosh and Khatib (2022), which emphasized that foreign investors bring home international standards of sustainability and encourage ESG reporting behaviour. The absence of a significant relationship in this study may be attributed to the relatively low average level of foreign ownership among the sampled firms, which limits its influence on strategic decisions such as sustainability disclosure. When foreign investors hold only minor stakes, their capacity to shape governance expectations or to push for stronger sustainability practices is considerably diminished. Moreover, in regulatory environments where ESG enforcement is relatively weak, foreign investors may place greater emphasis on financial returns, portfolio diversification, or risk management, rather than actively pushing for stronger ESG disclosure. From the perspective of Legitimacy Theory, the insignificant effect of foreign ownership suggests that the mere presence of foreign investors does not create sufficient legitimacy pressure when institutional frameworks are underdeveloped. In the absence of strong regulatory reinforcement or active investor engagement, firms may not view ESG disclosure as essential for maintaining their social license to operate, particularly when foreign ownership levels are relatively marginal. These findings suggest that, within Indonesia’s energy sector, foreign ownership by itself is insufficient to drive ESG disclosure unless it involves substantial shareholding or is supported by regulatory frameworks that enhance the influence of foreign investors.

4.9. Control Variable: Dummy COVID and Firm Age

The findings highlight a nuanced dynamic in ESG disclosure behavior during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The negative and statistically significant coefficient of the COVID-19 dummy variable (–0.085) indicates that firms were less inclined to provide ESG disclosures in the pandemic year, reflecting the disruptive impact of the crisis on corporate sustainability practices. This outcome may be explained by a shift in corporate priorities toward financial survival, operational continuity, and immediate crisis management, which in turn sidelined ESG initiatives. In addition, regulatory relaxations during the pandemic, such as the Financial Services Authority (OJK)’s extension of the 2020 fiscal year sustainability reporting deadline and eased submission requirements, may have further contributed to the decline, independent of managerial discretion. These combined factors help explain the temporary reduction in ESG transparency observed in 2020–2021.

By contrast, the positive and significant effect of firm age (coefficient = 0.003) suggests that more established firms are better equipped to sustain ESG practices, supported by their institutional maturity, stronger accountability to stakeholders, and greater accumulated resources. This contrast underscores the critical role of organizational resilience in sustaining ESG reporting. For policymakers and stakeholders, the findings point to the importance of providing support for younger or less mature firms in maintaining disclosure practices during periods of crisis, while also encouraging the long-term integration of ESG principles into corporate strategy, irrespective of economic shocks.

4.10. Channel Test: Sensitivity Analysis of the Moderating Effects of Ownership Structure on ESG Disclosure

Channel tests are presented through the addition of a sensitivity analysis, particularly in cases where a moderating variable is involved. This approach is consistent with prior studies that emphasize the importance of robustness checks to validate moderating effects (Ahmed and Anifowose 2024). Foreign ownership, as a proxy for ownership structure, has been identified as a factor that can moderate the relationship between firm age and ESG disclosure. This can be attributed to the tendency of firms with higher levels of foreign ownership to align more closely with international ESG standards, largely driven by the need to satisfy global investor expectations and strengthen their legitimacy. This observation is consistent with legitimacy theory, which posits that firms with substantial foreign ownership face stronger incentives to improve ESG transparency as part of their broader global strategic positioning. The moderating role of foreign ownership helps to illuminate how external governance pressures shape the influence of firm age on ESG disclosure. As shown in Table 8 (F-test for model fit) and Table 9 (t-test for moderation), the results provide evidence of a significant moderating effect of foreign ownership on the relationship between firm age and ESG disclosure.

Table 8.

F Test, Channel Test: Sensitivity Analysis of Moderating Effects.

Table 9.

t Test, Channel Test: Sensitivity Analysis of Moderating Effects.

Based on the F-test results reported in Table 8, the model demonstrates strong overall significance, with an F-statistic of 7.862 and a p-value of 0.000 (<0.05). The results suggest that, collectively, the independent variables Return on Assets (ROA), Current Ratio (CR), managerial ownership, institutional ownership, foreign ownership, firm age, the COVID-19 dummy, and the interaction term between firm age and foreign ownership (Age × ForOwn) are jointly significant in explaining variations in ESG disclosure. Accordingly, the regression model demonstrates a good overall fit for evaluating the moderating role of foreign ownership within the broader ownership structure framework.

Table 9 presents the results of the sensitivity analysis through a moderation test, specifically examining whether foreign ownership moderates the effect of firm age on ESG disclosure. The coefficient for the interaction term (Age × ForOwn) is −0.001 with a significance value of 0.773 (>0.05). The results indicate that foreign ownership does not significantly moderate the relationship between firm age and ESG disclosure. In other words, the presence of foreign investors neither amplifies nor diminishes the influence of organizational maturity on ESG reporting practices. This outcome may reflect the relatively limited role of foreign investors within Indonesia’s energy sector, where institutional frameworks and regulatory enforcement remain fragmented. Consequently, foreign ownership on its own may not generate the external legitimacy pressures necessary to alter the disclosure behavior of more established firms.

5. Conclusions, Implications, Limitations and Further Research

The purpose of this research is to investigate how the COVID-19 environment, ownership structures (managerial, institutional, and foreign ownership), and financial risk (measured through ROA and CR) influence ESG disclosure among firms in Indonesia’s energy sector. The findings indicate that institutional investors exert a positive effect on ESG disclosure, which may reflect their greater exposure to regulatory oversight and their stronger commitment to sustainability standards. This suggests that such investors are likely to exert pressure on corporations to disclose their sustainability initiatives more transparently. By contrast, management ownership, financial risk, and foreign ownership were found to be statistically insignificant, indicating that the ESG practices of the sampled firms are not substantially shaped by internal managerial incentives or the composition of foreign shareholders. The findings reveal that the COVID-19 pandemic exerted a significant negative impact on ESG disclosure, indicating that many firms scaled back their sustainability reporting during the crisis. In contrast, firm age demonstrated a significant positive effect, suggesting that more established companies maintained stronger commitments to ESG disclosure, likely driven by their accumulated experience, institutionalized practices, and greater accountability to stakeholder expectations.

This study adds to the expanding literature on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure by underscoring the pivotal roles of institutional ownership and firm age. The results indicate that higher levels of institutional ownership are positively associated with greater ESG transparency, suggesting that long-term investors act as catalysts for more rigorous sustainability reporting, particularly in environmentally sensitive sectors such as energy. Similarly, older firms demonstrate a stronger tendency to disclose ESG information, a pattern that may be attributed to their accumulated experience, more established governance structures, and heightened accountability to diverse stakeholders.

The scholarly contribution of this study can be further strengthened by engaging with recent literature and deepening the discussion of policy implications. In particular, it provides timely insights into the Indonesian context, where, under President Joko Widodo and continuing with President-elect Prabowo, the government has significantly expanded avenues for large-scale foreign investment. Indonesia’s leadership at the 2022 G20 Summit in Bali, marked by the promotion of blended finance mechanisms to attract sustainable investment, has further reinforced the expectation that investors committed to ESG principles will be prioritized and welcomed (UNSDSN 2024). This strategic condition is closely reflected in our foreign ownership proxy, which illustrates the influence of international investors on corporate ESG disclosure. By framing ESG disclosure simultaneously as an institutional mandate and a market-driven response, this study offers a distinctive contribution that is globally relevant while firmly grounded in the context of an emerging economy.

For regulators, the findings highlight the need to design policies that actively encourage institutional investor participation in ESG engagement, for example, through stewardship codes or disclosure-based incentives aimed at firms demonstrating high-quality ESG reporting. For companies, particularly those with relatively low ESG visibility, cultivating long-term partnerships with institutional investors and leveraging organizational maturity to institutionalize ESG frameworks can strengthen both legitimacy and investor confidence. From the investors’ perspective, ESG transparency functions as a valuable screening mechanism for identifying opportunities for long-term value creation, especially in emerging markets where regulatory systems are still developing. Ultimately, clearer disclosure requirements, combined with sustained investor pressure, can help align corporate behavior more closely with global sustainability standards.

Recent studies further emphasize these implications, indicating that ESG disclosure is influenced not only by stakeholder expectations but also by the dynamics of evolving regulatory frameworks, particularly within emerging markets (Bolognesi et al. 2025; Del Gesso and Lodhi 2025). ESG transparency is closely associated with enhanced corporate sustainability performance and greater resilience in the face of financial or environmental shocks (Duan et al. 2025; Lajili et al. 2024). Moreover, linking ESG practices with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can not only enhance corporate legitimacy but also reinforce alignment with internationally recognized sustainability benchmarks (Nicolo et al. 2024).

While this study advances the understanding of ESG disclosure, several limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, the measurement of ESG disclosure relied on Nasdaq’s 2019 binary scoring system (1 = disclosed; 0 = not disclosed), which, while practical, may not adequately capture the richness, quality, or credibility of the reported information. This binary method only reflects the presence or absence of disclosure and does not assess its depth, specificity, or alignment with material ESG standards. Future research is encouraged to adopt more fine-grained approaches, such as content analysis based on sentence counts, disclosure intensity, or advanced text analytics, to provide a more comprehensive and nuanced assessment of ESG reporting practices. Furthermore, as the ESG reporting landscape continues to evolve rapidly with the global adoption of standards such as IFRS S1 and S2 issued by the IFRS Foundation, future studies may consider incorporating these frameworks to ensure alignment with international disclosure expectations. This study utilizes ROA and Current Ratio as proxies for financial risk; while relevant, these indicators do not fully capture the multidimensional nature of financial risk, such as leverage, earnings volatility, and solvency.

Future research may consider incorporating these additional proxies to provide a more comprehensive risk assessment. This study did not employ panel regression techniques due to the unbalanced nature of the dataset; future research is encouraged to apply panel data approaches (e.g., fixed effects or random effects) to enhance the robustness of the findings. Finally, this study did not include additional control variables such as firm size or market capitalization, primarily due to sample size constraints in the Indonesian energy sector, which limits the number of observations available. Future research with larger or multi-sectoral datasets is encouraged to explore these variables, which may provide further explanatory power in understanding ESG disclosure behavior.

Although this study extends its observation period to five years and incorporates internal control variables such as firm age, certain limitations remain. The analysis is confined to publicly listed companies within selected sectors, which restricts the extent to which the findings can be generalized to privately held firms or other industries. Moreover, the current model focuses on quantitative measures and does not capture the qualitative dimensions of ESG practices, for instance, the authenticity of initiatives or the strategic intent underlying disclosure. Future research could address this gap by employing qualitative content analysis or by integrating third-party evaluations, such as those provided by ESG rating agencies. In addition, subsequent studies may consider external moderating factors such as political stability, adherence to international ESG frameworks (e.g., GRI, TCFD), or pressures from stakeholders, including NGOs and civil society, to better reflect the broader institutional and cultural contexts that shape ESG disclosure behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition—A.H.M.; Methodology, Software, Data curation, Writing—review and editing, Visualization, Project administration—O.T.E.; Validation—A.H.M., O.T.E. and O.I.B.H.; Writing—original draft preparation—A.H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. APC Funding: The APC was funded personally by Aloysius Harry Mukti.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdi, Yaghoub, Xiaoni Li, and Xavier Càmara-Turull. 2021. Exploring the impact of sustainability (ESG) disclosure on firm value and financial performance (FP) in airline industry: The moderating role of size and age. Environment, Development and Sustainability 24: 5052–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Abubakar, and Mutalib Anifowose. 2024. Corruption, corporate governance, and sustainable development goals in Africa. Corporate Governance 24: 119–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amosh, Hamzeh, and Saleh F. A. Khatib. 2022. Ownership structure and environmental, social and governance performance disclosure: The moderating role of the board independence. Journal of Business and Socio-Economic Development 2: 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Matari, Ebrahim Mohammed. 2025. Ownership structure and earnings management: The role of environmental sustainability as moderator variable. A Further analysis. Saudi evidence. Cogent Business & Management 12: 2504131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeyda, Raisa, and Asep Darmansya. 2019. The Influence of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure on Firm Financial Performance. IPTEK Journal of Proceedings Series 5: 278–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelia, Anggita Rezki. 2019. Perusahaan Migas dan Tambang Terkena Sanksi Pencemaran Lingkungan. Katadata.Co.Id. Available online: https://katadata.co.id/arnold/berita/5e9a55526efa2/11-company-migas-dan-tambang-terkena-sanksi-pencemaran-environment (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Baraputri, Valdya. 2023. The rush for nickel: “They are destroying our future”. BBC News Indonesia, July 10. [Google Scholar]

- Bayong, Desmond, Bernard Bawuah, and Elizabeth Amoah. 2024. Advancing environmental, social, and governance disclosure in emerging economies: Does regulatory envi-ronment and ownership structure matter? Future Business Journal 5: 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednárová, Michaela. 2025. ESG Reporting and Communication. In Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Investment and Reporting. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-84235-1_8 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Bolognesi, Enrica, Alberto Burchi, John W. Goodell, and Andrea Paltrinieri. 2025. Stakeholders and regulatory pressure on ESG disclosure. International Review of Financial Analysis 103: 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairani, Rizki, and Zuraida Zuraida. 2021. Effects of Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosures on Organizational Visibility: Empirical Study of Non-Financial Companies Listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange. Indonesian Journal of Sustainability Accounting and Management 5: 354–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, Peter M., Yue Li, Gordon D. Richardson, and Florin P. Vasvari. 2008. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society 33: 303–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, Ícaro Guilherme Félix, Renata Veloso Santos Policarpo, Paula Cristina Senra de Oliveira, Etienne Cardoso Abdala, and Daisy Aparecida Do Nascimento Rebelatto. 2025. ESG disclosures in high-pollution industries: The role of board structure and ownership. Future Business Journal 11: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasilas, Apostolos, and Goran Karanović. 2025. ESG disclosures in high-pollution industries: The role of board structure and ownership. The Journal of Risk Finance 26: 410–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Gesso, Carla, and Rab Nawaz Lodhi. 2025. Theories underlying environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure: A systematic review of accounting studies. Journal of Accounting Literature 47: 433–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, Dan S., Oliver Zhen Li, Albert Tsang, and Yong George Yang. 2011. Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. The Accounting Review 86: 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, Paul J., and Walter W. Powell. 1983. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review 48: 147–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Kai, Chuan Qin, Shenglin Ma, Xue Lei, Qianqian Hu, and Jinhuika Ying. 2025. Impact of ESG disclosure on corporate sustainability. Finance Research Letters 78: 107134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elafify, Mohamed Gamal. 2021. Determinants of Corporate Sustainability Disclosure: The Case of the S&P/EGX ESG Index. Indonesian Journal of Sustainability Accounting and Management 5: 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elafify, N. 2021. Corporate sustainability disclosure: Determinants and governance mechanisms in Egypt. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 19: 487–504. [Google Scholar]

- Erhemjamts, Otgontsetseg, Kershen Huang, and Hassan Tehranian. 2022. Climate Risk, ESG Performance, and ESG Sentiment for U.S. Commercial Banks (November 12). Global Finance Journal, Forthcoming. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4275638 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Friede, Gunnar, Timo Busch, and Alexander Bassen. 2015. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 5: 210–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Bueno, Jairo, Rima Tamošiūnienė, Camilo Gómez Morales, and Gladys Rueda-Barrios. 2025. ESG-oriented portfolio optimization in an emerging market: A bi-objective mean–variance approach. Business, Management and Economics Engineering 23: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, Damodar N., and Dawn C. Porter. 2009. Basic Econometrics, 5th ed. Columbus: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2019. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed. Boston: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Istianingsih, and Robertus Suraji. 2020. The Impact of Competitive Strategy and Intellectual Capital on SMEs Performance. Jurnal Manajemen 24: 427–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafar, Rosmiati, Basuki Basuki, Windijarto Windijarto, Rahmat Setiawan, and Zulnaidi Yaacob. 2024. ESG disclosure and the cost of equity capital: Evidence from emerging markets. Cogent Business & Management 11: 2429794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhmani, Omar Issa. 2013. Ownership structure and corporate voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Bahrain. International Journal of Accounting and Financial Reporting 3: 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, Fahad, Asif Razzaq, Jiang Ming, and Ummara Razi. 2022. Firm Characteristics, Governance Mechanisms, and ESG Disclosure: How Caring About Sustainable Concerns? Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sang, and Zhichuan Li. 2021. Understanding the Impact of ESG Practices in Corporate Finance. Sustainability 13: 3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhuharov, V., E. Mitrofanova, and P. Zlateva. 2024. Ownership structure, ESG disclosure, and capital inflows in transitional economies. Business, Management and Economics Engineering 22: 91. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Praveen, and Mohammad Firoz. 2022. Does Accounting-based Financial Performance Value Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Disclosures? A detailed note on a corporate sustainability perspective. Australasian Accounting Business & Finance Journal 16: 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lajili, Kaouthar, Tie Mei Li, Lamia Chourou, Michael Dobler, and Daniel Zéghal. 2024. Corporate risk disclosures in turbulent times: An international analysis in the global financial crisis. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting 35: 261–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lunawat, Ajay, and Dipti Lunawat. 2022. Do Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance Impact Firm Performance? Evidence from Indian Firms. Indonesian Journal of Sustainability Accounting and Management 6: 133–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ferrero, Jennifer, and María-Belén Lozano. 2021. The nonlinear relation between institutional ownership and environmental, social and governance performance in emerging countries. Sustainability 13: 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasdaq. 2019. ESG Reporting Guide 2.0: A Support Resource for Companies. Available online: https://www.nasdaq.com/docs/2019/11/26/2019-ESG-Reporting-Guide.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Naseer, Mirza Muhammad, Muhammad Asif Khan, Tanveer Bagh, Yongsheng Guo, and Xiaoxian Zhu. 2023. Firm climate change risk and financial flexibility: Drivers of ESG performance and firm value. Borsa Istanbul Review 24: 106–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolo, Giuseppe, Giovanni Zampone, Serena De Iorio, and Giuseppe Sannino. 2024. Does SDG disclosure reflect corporate underlying sustainability performance? Evidence from UN Global Compact participants. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting 35: 214–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ould Daoud Ellili, Nejla. 2020. Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure, Ownership Structure and Cost of Capital: Evidence from the UAE. Sustainability 12: 7706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayoom, Ifra, and Khalid Chisti. 2025. Earnings transparency and ESG reporting: An empirical investigation. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 23: 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, Chetna, Florentina Kurniasari, and Malabika Deo. 2020. CEO Compensation and Firm Performance: The Role of ESG Transparency. Indonesian Journal of Sustainability Accounting and Management 4: 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalika, Dina Nilam, Nurul Fauziah, and Martdian Ratna Sari. 2024. Financial Ratios on Reducing Financial Distress Moderated by ESG Disclosure. Jurnal REKSA: Rekayasa Keuangan, Syariah Dan Audit 11: 122–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scamans, Sophie. 2024. Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive’s (CSRD) Impacts on Stakeholders: An Analysis of the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). LUT University. Available online: https://lutpub.lut.fi/handle/10024/167556 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Sembiring, Ferikawita M. 2023. Firm Size, Market Risk, and Return Reversal Anomalies During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Jurnal Manajemen 28: 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Yuwei, and Sandra Dow. 2025. Corporate Governance Under Climate Change: Ensuring Strategic Cohesion from Today to 2100. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shocker, Allan D., and S. Prakash Sethi. 1974. An Approach to Incorporating Social Preferences in Developing Corporate Action Strategies. New York: Melville Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, Mark C. 1995. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review 20: 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunani, Avi, Ulfa Puspa Wanti Widodo, R. Muh, Syah Arief Atmaja Wijaya, and Nanda Wahyu Indah Kirana. 2024. Environmental Disclosure Analysis of Manufacturing Companies to Realize Sustainable Green Economy. Jurnal Ilmiah Manajemen Forkamma 7: 321–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Survilaitė-Venskienė, S., and J. Stankevičienė. 2024. Sectoral sensitivity of credit risk and financial distress prediction in ESG-integrated models. Business, Management and Economics Engineering 22: 123. [Google Scholar]

- Tampakoudis, Ioannis, Athanasios Noulas, Nikolaos Kiosses, and George Drogalas. 2021. The effect of ESG on value creation from mergers and acquisitions. What changed during the COVID-19 pandemic? Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 21: 1117–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Ye, and Mengyang Zhao. 2025. Does managerial climate risk perception improve environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance? International Review of Financial Analysis 91: 102961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network (UNSDSN). 2024. Historic Launch of the G20 Bali Global Blended Finance Alliance to Unlock Green Investment for the Global South. Available online: https://www.unsdsn.org/news/historic-launch-of-the-g20-bali-global-blended-finance-alliance-to-unlock-green-investment-for-the-global-south/ (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Velte, P. 2020. Institutional ownership and voluntary sustainability reporting: Empirical evidence from Europe. Management Research Review 43: 123. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey M. 2013. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 5th ed. Boston: South-Western Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Xingyu, and Yunan Shi. 2024. Optimising corporate financial performance through ESG integration faced by climate change. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences 128: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]