1. Introduction

Cryptocurrencies are increasingly used in decentralised financial transactions, ensuring authenticity and uniqueness through cryptographic functions, as stated in

Farell (

2015). Due to these characteristics, cryptocurrencies have drawn considerable attention regarding their potential use in illicit activities, such as money laundering, as noted in

Blockchain.com (

n.d.). According to chain analysis in

Chainalysis (

2024), the amount involved in money laundering with cryptocurrencies reached

$31.5 billion in 2022, representing a 72.13% increase compared to 2021, when the value was

$18.3 billion. In 2023, the amount laundered was approximately

$22.2 billion, a 29.5% decrease attributed by the authors to the general decline in cryptocurrency transactions during that year.

Recent research on the use of cryptocurrencies in illicit activities—particularly money laundering—has been focused on the associated risks, scalability, and evolving regulatory frameworks, see

Burgess (

2024);

Song et al. (

2024). Also, most of these studies examine specific money laundering contexts without thoroughly assessing the broader spectrum of techniques employed. Our previous work in

Almeida et al. (

2023) describes a set of cryptocurrency-based money laundering methods. However, the methods are neither comprehensively analyzed nor quantified across their multiple dimensions.

This paper addresses these research gaps by providing a thorough analysis of money laundering methods based on cryptocurrencies and from a standard user perspective, with particular attention to the critical factors that influence their implementation and detection. It also provides a comprehensive categorisation and quantification of these methods across multiple dimensions, such as duration, actors, contextual requirements, difficulty, traceability, and cost.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work, highlighting key contributions to the literature on money laundering through cryptocurrencies, revisiting different stages, compliance frameworks, regulations, and the evolution of laundering methods.

Section 3 presents the evaluation model for categorising methods by different strategies and defines the analysis dimensions, such as duration, stakeholders, contextual requirements, difficulty, traceability, and cost.

Section 4,

Section 5, and

Section 6 provide a detailed analysis of each method according to these dimensions.

Section 7 discusses the results, exploring practical implications and challenges in terms of regulation, technological implementation, and risk mitigation. Finally,

Section 8 concludes this work and outlines future research directions aimed at improving detection and prevention strategies against money laundering through cryptocurrencies.

2. Related Work

Cryptocurrencies have been analysed over the years, emphasising the characteristics that allow them to function as tools for illicit actions whose monetary dimension works essentially through digital channels. As stated in

Almeida et al. (

2023), these characteristics are mainly decentralised architecture, common absence of a controlling authority, mobility, and pseudo-anonymity, completed with irreversibility and immutability of their state.

2.1. Processes and Stages of Cryptocurrency Money Laundering

Money laundering is the method of transforming the state of money value from an illegal origin into an asset or currency perfectly integrated into the legal financial circuit without apparently any suspicion. These actions become necessary when the owners of illicit money want to spend their illegal profits in the regular economy. Profits from illegal businesses present their owners with the challenge of being able to make use of large amounts of physical money while guaranteeing its trustworthiness, as described in

Kramer et al. (

2023).

Although cryptocurrencies do not face traditional physical and logistical constraints associated with tangible currencies, they are traded within financial systems that increasingly apply regulatory frameworks similar to those used for conventional assets. Thus, money laundering using cryptocurrencies commonly adopts the same stages as traditional money laundering, i.e., placement, layering, and integration. Research works such as in

Almeida et al. (

2023);

Mooij (

2024a,

2024b);

Wu et al. (

2024), detail these different stages. The placement stage aims to remove all connections between the illicit funds and their source or ownership. The layering stage involves moving the funds through various applications or accounts to obscure the source of the money. The Integration stage is the final part of the process, where these funds are assimilated into the legitimate economy, thereby acquiring a semblance of legitimacy.

More recently, the research work in

Gilmour et al. (

2024) has revisited the classical three-stage money laundering framework, stating that in contemporary, technology-enabled money laundering schemes, the traditional model has important limitations since the boundaries between stages are often blurred.

2.2. Regulatory and Compliance Challenges

The rapid expansion of cryptocurrencies has transformed the global financial landscape, creating both opportunities and new regulatory challenges. While these technologies have enabled faster and more accessible financial transactions, they have also introduced mechanisms that can be exploited for illicit purposes. In particular, cryptocurrencies offer unprecedented levels of pseudonymity, making them highly attractive to individuals and organisations seeking to conceal criminal proceeds and bypass traditional financial controls.

It has been noted that a significant volume of money now circulates online and that the proceeds of cybercrime rarely leave the digital realm. As discussed in

Wronka (

2021a), the use of cryptocurrencies allows cybercriminals to enhance their privacy by creating multiple layers of transactions, thereby achieving a high degree of anonymity. Research has also examined the compliance risks associated with cryptocurrencies, focusing on their potential misuse for money laundering, as noted in

Teichmann and Falker (

2020). Drawing on interviews with compliance officers and alleged criminals, as well as questionnaires distributed to 200 compliance experts, these studies found that many professionals perceive cryptocurrencies as well-suited for money laundering and that detection risks are relatively low. Cryptocurrencies pose significant challenges for Anti-Money Laundering (AML) frameworks due to their minimal identification requirements and limited regulatory oversight. Although illicit use demands some technical knowledge, the required tools and resources are widely available, and the laundering techniques employed range from simple, low-risk methods to complex, high-risk schemes.

The authors in

Gabbiadini et al. (

2024) highlight that in Centralised Finance (CeFi) it is possible to identify entities on which to impose anti-money laundering obligations similar to those in traditional finance. This is the direction in which European legislation is evolving, but in this case, Decentralised Finance (DeFi) presents multiple challenges with regard to the possibility of introducing mechanisms to protect legality. To balance privacy needs with the control of illicit use risk, the market is developing technological solutions that, in the absence of intermediaries and other entities, attempt to codify the necessary controls into smart contracts. Overall, they conclude that, in its current form, decentralised technology cannot yet replace the active role of intermediaries in AML and that any future DeFi safeguards will create additional challenges for regulators and supervisory authorities.

Other studies have highlighted how cryptocurrencies and new payment technologies are reshaping the way people interact with finance. While these innovations provide significant benefits to consumers, they also unintentionally create new risks for money laundering and terrorist financing. Through systematic analysis, these works identify emerging trends that facilitate illicit activities and propose risk assessment frameworks to anticipate their potential consequences, see

Akartuna et al. (

2022).

The authors of

Verma (

2024) examine how the diffusion of cryptocurrencies reshapes money laundering practices, discussing changes in offender behaviour and regulatory responses and highlighting both the challenges and the opportunities associated with emerging analytical techniques. Their findings suggest that, although cryptocurrencies pose a significant challenge, innovative technology solutions coupled with international cooperation can play a vital role in mitigating the risks associated with cryptocurrency-based money laundering.

2.3. Impact of Recently Implemented Regulatory Measures

Regulatory measures are a well-studied topic and, like blockchains, are constantly evolving.

Wronka (

2021b) mentions that the fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD) did not cover crypto exchanges, wallet providers, or mixer/tumbler services within its scope. As a result, these entities were not required to comply with identification obligations. In this regard, Fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD5)

European Union (

2018a) expanded the regulatory framework to include custodial wallet providers and service providers engaged in the exchange between virtual and fiat currencies. Regulation in Sixth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD6),

European Union (

2018b), further strengthens the legal framework through Article 1, which outlines the intention to more effectively combat money laundering; Article 3, which defines money laundering offences regardless of the context or environment in which they occur; and Article 5, which broadens the applicable criminal sanctions, establishing the criminalisation of money laundering activities, including operations involving cryptocurrencies related to illicit assets.

In this context, we are witnessing the enforcement of the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA) Regulation, which aims to provide a unified regulatory framework for European Union (EU) member states concerning cryptocurrencies. According to

Legal Nodes (

2024);

Zhang (

2022), the key objectives of MiCA are (1) to replace individual regulations found in several EU nations with a single, unified, and comprehensive framework; (2) to establish rules for crypto-asset service providers and token issuers; and (3) to provide greater legal certainty in areas not covered by existing financial regulations. Among the services covered by MiCA are Crypto-Asset Service Providers (CASPs), which include (1) custodial wallets; (2) exchanges for crypto-to-crypto or crypto-to-fiat transactions; (3) crypto-trading platforms; and (4) crypto-asset advisory firms and portfolio managers.

The EU Regulation 2023/1114, known as MiCA,

European Union (

2023), was published in the Official Journal of the EU on 9 June 2023 and entered into force twenty days later, on 29 June 2023. The rules on Asset-Referenced Tokens (ARTs) and E-Money Tokens (EMTs) have applied since 30 June 2024, while all remaining provisions became mandatory on 30 December 2024, thereby subjecting every EU crypto-asset service provider to the new regulatory framework.

Beyond the EU context,

Zhou (

2025) provides a broader assessment of how existing AML frameworks and regulatory responses are adapting to crypto money laundering, focusing on Financial Action Task Force (FATF) standards and on the approaches adopted in the United States, the European Union, and Singapore, and arguing that current regimes remain fragmented and largely reactive. The authors consider two modes of technology-based regulatory intervention that could help address these gaps: a “stop and freeze” approach, relying on institutionalised blockchain analytics and blacklisting technologies, and an “opt-in” approach, leveraging zero-knowledge proofs and blockchain oracles to develop a digital identity verification mechanism that maximises user privacy.

The regulatory tools discussed in this work were selected because of their importance. These instruments are a part of the core of the current frameworks regarding anti-money laundering regulations applied to crypto assets in the European Union. A full comparison between the world’s regulatory instruments would fall beyond the scope of this study, but the European context is especially relevant regarding its influence on international standards.

2.4. Technological Evolution and Sophisticated Laundering Methods

According to

Calafos and Dimitoglou (

2022), traditional money laundering has evolved naturally into cyberspace. Since traditional money laundering involves the cleansing of physical currency, it is exposed to a high risk of detection and multiple points of failure. To avoid being detected, criminals typically enlist multiple associates to move illicit physical funds through various financial instruments or assets repeatedly. However, the detection of even a single transaction within this circuit by legal authorities can lead investigators back to the source of criminal activity.

Cyberlaundering, by contrast, represents a different reality that requires new skills and approaches to address the challenges posed by online tools and cryptocurrencies. Risk points still exist, but they are significantly lower, largely due to the inherent characteristics of blockchain technology, such as pseudonymity. Moreover, cybercriminals engaging in cyberlaundering do not need to rely on a large number of associates or intermediaries to complete the process successfully.

More sophisticated money laundering methods have also emerged as described in

Almeida et al. (

2023). These include tumblers or mixing services, decentralised exchanges, chain hopping (i.e., moving funds across different blockchains), and even cryptocurrency-based online casinos.

The authors of

See (

2024) provide a focused review of Bitcoin mixers, examining how mixing services facilitate money laundering and assessing the effectiveness and limitations of current detection techniques.

Additionally, advanced obfuscation techniques have been documented by

Wu et al. (

2024). One example is the use of Decentralized Exchange (DEX) token swaps to exchange stolen tokens for others that are more difficult to track or freeze, while simultaneously enabling their transfer across multiple blockchains. Another example is the deployment of counterfeit tokens, in which cybercriminals create fake tokens and trade them while posing as legitimate market participants. Furthermore, they may sell stolen Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) at lower prices to rapidly convert them into other cryptocurrencies, making the tracing of stolen funds more difficult.

Although this overview is conceptual, the methods described in this subsection reflect techniques documented in research reports and enforcement actions in which crypto assets are moved in order to disguise illicit proceeds, often combining several of these methods in the same money laundering scheme. These observations guided the selection and qualitative characterisation of the techniques analysed in the following sections.

3. Methodology

To structure the methodological analysis, this study first outlines the general framework used to evaluate cryptocurrency-based money laundering techniques, adopting the classical three-stage money laundering framework—placement, layering, and integration—as the structural basis for analysing cryptocurrency-based laundering techniques. The methods considered in each stage and their qualitative classification draw on the existing academic literature, technical reports issued by international entities, and industry-available support materials that document how cryptocurrencies are used in multiple practices with money laundering in mind. Foundational taxonomy outlined in

Almeida et al. (

2023) was used among other scientific, academic, and technical sources spanning approximately the last decade up to early 2025, starting from the most recent publications and moving backwards. The analysis systematically details these methods and distributes them according to their alignment with the primary objectives of that stage, taking into account that the boundaries between these stages are often faded as noted in

Gilmour et al. (

2024).

The selected methods are composed of in-person transactions, Cryptocurrency Automated Teller Machine (ATM) (Crypto ATMs), Peer-to-Peer (P2P) transactions, prepaid or gift cards, NFT transactions, mixing services or tumblers, chain hopping, DEXs, online crypto casinos, and investments through cryptocurrencies. The selected methods and their categorisation per the defined stages are presented in

Table 1, where the symbol “•” means that the method is included in a particular stage, “∘” means that the method is included in multiple stages, and “–” means that the method is not included.

The selected methods range from simple, low-volume transactions to more elaborate and multifaceted processes and demonstrate differing levels of complexity, thereby illustrating the variety of tactics that challenge AML measures. The NFT transactions method is included in all three stages of money laundering, and may use blockchains with more advanced anonymisation features, such as Ethereum. Specifically, it functions as a placement method when a selected NFT is purchased using illicit funds. It also serves as an integration method because of the symmetrical nature of selling or exchanging the NFT for legitimate currency. Finally, it can serve as a layering method due to the repeated buying and selling of various NFTs in markets that employ high levels of anonymity and complexity, making transaction tracing significantly more difficult.

The selected money laundering methods rely on cryptocurrency transactions. Although multiple cryptocurrencies exist with distinct features—including privacy-focused coins such as Monero and Zcash—evaluating their traceability and other relevant dimensions would require separate, coin-specific analyses regarding privacy. Therefore, this study adopts a more general, agnostic approach to currency-specific features.

The consequent evaluation follows a parametric approach: each method was assessed against a set of predefined dimensions. The selected dimensions were duration, actors, contextual requirements, difficulty, traceability, and cost. Each dimension was scored in a range of 1 to 5, and its description and respective score details are presented in

Table 2.

The application of these dimensions was based on a user profile with average internet and computing skills, drawing on scenarios and statistical means gathered from publicly available scientific literature and web resources. In defining the “contextual requirements” and “difficulty” scales, the assessment is calibrated to the user profile mentioned, as those are the minimal skills required for everyday use of online banking and digital platforms—rather than to a highly specialised cybercriminal. This assumption is intended to approximate how accessible each technique would be for the majority of potential offenders. Draft scores and qualitative descriptions were first developed independently and then discussed until consensus was reached, so that the resulting profiles reflect a consistent interpretation across the three stages and can be replicated or refined in future work. Thus, from a research perspective, this is an exploratory and qualitative study based on secondary sources and structured empirical judgement rather than on transaction-level data. The output of the analysis and the discussion provided serves as the basis for the study’s conclusions and recommendations.

The following sections assess each technique in the three stages of money laundering: placement, layering, and integration.

4. Placement Stage

The placement stage assessment follows the same six-dimensional framework introduced in the methodology, with the methods selected for this stage, using the same evaluation criteria.

4.1. Duration

The duration of the placement stage varies depending on the method used. In-person transactions typically last between 1 and 3 h on average, assuming the buyer seeks options located nearby. Similarly, transactions through ATMs are generally short, with the main variable being the distance to the selected machine. However, the limited availability of ATMs that meet specific anonymity requirements can increase this duration, with up to 3 h being acceptable in most situations.

P2Ps transactions and prepaid card purchases follow similar structures and processes. Although the actual transaction is brief, the overall duration depends on the availability of suitable selling offers and the time required to evaluate them, usually extending the total time to around 1 h.

In contrast, NFT transactions tend to be more time-consuming due to several factors, including identifying the specific NFT to be purchased and the method of acquisition. If an auction is involved, the process can extend from several hours to multiple days, depending on when the auction closes. Additional elements, such as the search for a desired item or counterparty, variations in blockchain performance, and the buyer’s level of experience, can further affect the duration. As a result, NFT transactions may range from approximately 6 h to one or more days.

4.2. Actors

In an in-person transaction, assuming the software used is not a financial tool, nor a participant, but a tool to provide communication to set up the transaction, two known actors meet face-to-face. Regarding crypto ATM, the process is very one-sided, involving only the buyer and the machine. For the remaining methods in the placement stage, the primary actor (the buyer) interacts directly with the platform and, indirectly, with the seller. As a result, each transaction involves at least one to three actors.

4.3. Contextual Requirement

The resources required for placement methods vary depending on the type of transaction, but share several common elements. An in-person purchase involves relatively few resources: a means of communication (via phone or the internet), a cryptocurrency wallet, and physical presence. Transactions through crypto ATMs require a similar set of resources, with the addition of a smartphone equipped with a QR code reader and internet access, as well as a digital wallet to receive and store the cryptocurrency.

P2P transactions and prepaid card purchases rely on an internet connection, a digital wallet, and a web browser to access the chosen trading platform. Finally, NFT transactions have similar technical requirements to P2Ps and prepaid card methods. However, they generally demand a more advanced level of user knowledge to navigate marketplaces, manage smart contracts, and complete transactions securely.

4.4. Difficulty

The difficulty associated with each placement method depends primarily on the level of user knowledge and familiarity required to complete the transaction. In-person purchases are the simplest, involving basic human interaction and minimal technical skills.

Crypto ATMs are designed to be user-friendly and intuitive. Although some basic understanding and preparation are needed—such as identifying a suitable machine and ensuring access to the necessary tools—the process itself is straightforward once the information has been gathered.

The remaining methods require a higher level of user knowledge, as the procedures vary across platforms. For P2P transactions, once the user has completed the registration process, the steps are generally clear and easy to follow. Prepaid card purchases vary slightly between platforms but largely mirror the process of P2P transactions, and both methods are often available on the same platforms.

NFT transactions, however, typically involve a more complex process. While several P2P platforms exist for NFTs, selecting and purchasing an asset requires gathering and analysing more information, making it less straightforward than the other methods.

4.5. Traceability

This is a central feature of the work carried out by the authors in this field. All methods have their variations, and at this stage, the possibility of tracing through methods such as person-to-person investigation or the verification of Know Your Customer (KYC) procedures will be analysed. The face-to-face method exhibits a low level of traceability, assuming that both parties have a vested interest in keeping the transaction discreet. This approach can involve a direct exchange of cash for cryptocurrency using a digital wallet, which minimises recorded evidence and makes the transaction difficult to trace.

In terms of crypto ATMs, they are difficult to trace due to the absence of stringent identity verification processes. These machines are spread across many countries and come in various models that either only sell or buy cryptocurrencies, or both. Some ATM networks explicitly opt for anonymity, as highlighted on their websites with demonstrations. In contrast, other models or networks may require additional steps to maintain anonymity, such as creating virtual mobile phone numbers and using anonymous wallets to manage transactions. However, non-KYC crypto ATMs are becoming increasingly difficult to find due to tightening regulations, making low traceability more challenging to achieve. Furthermore, despite the lack of KYC procedures, all blockchain transactions are publicly recorded, which can potentially allow tracking through advanced analytics, as noted in

Sharma (

2023).

P2P transactions can offer a certain level of anonymity using decentralised platforms and without mandatory KYC procedures and anonymous wallets.

As for prepaid gift cards, they can be bought and sold relatively cheaply through decentralised platforms or in person. However, while these transactions are relatively common, their overall volume tends to be low, limiting their usefulness for larger sums. In addition, there is significant logistical complexity associated with handling a large number of cards, whether digital or physical. Regarding transactions with NFTs, their traceability tends to be high due to the authenticity of the goods in question, and transactions with cryptocurrencies are public, but the pseudo-anonymity of the blockchain and some preventive measures with the use of decentralised platforms and anonymising wallets tend to lower their level of traceability. However, the fact that it is a high-profile asset may counter the interest in anonymity at this stage.

4.6. Cost

The costs associated with different placement methods vary significantly depending on the transaction type and the platforms involved. For in-person transactions, there are no additional costs beyond the agreed purchase price. If the transaction occurs at market value, no extra cost is incurred; however, in many cases, the seller charges a premium, which increases the total cost.

In contrast, crypto ATMs are typically associated with high costs. Transaction fees can exceed 20%, including both network fees and the fees charged by the ATM itself, as discussed in

Huffman (

2024);

Mae (

2024). This makes them one of the most expensive options for acquiring cryptocurrency.

P2P transactions occupy a middle ground, with costs that are highly variable and largely dependent on the platform used. Some platforms charge a fixed fee per transaction, others apply a percentage-based fee, and network transaction fees must also be considered. Similarly, gift card transactions reflect the nature and complexity of the underlying processes. Purchasing at resale, particularly in large quantities, can be cumbersome and is often reflected in higher prices.

Finally, NFT transactions can involve substantial costs, not only due to the potentially high value of the assets exchanged but also because of the “gas fees” required on networks such as Ethereum. These factors combined make NFT transactions one of the more expensive methods within the placement stage.

4.7. Summary

This analysis of the placement stage was conducted using the following methods: in-person transactions, crypto ATMs, P2P transactions, prepaid gift cards, and NFT transactions.

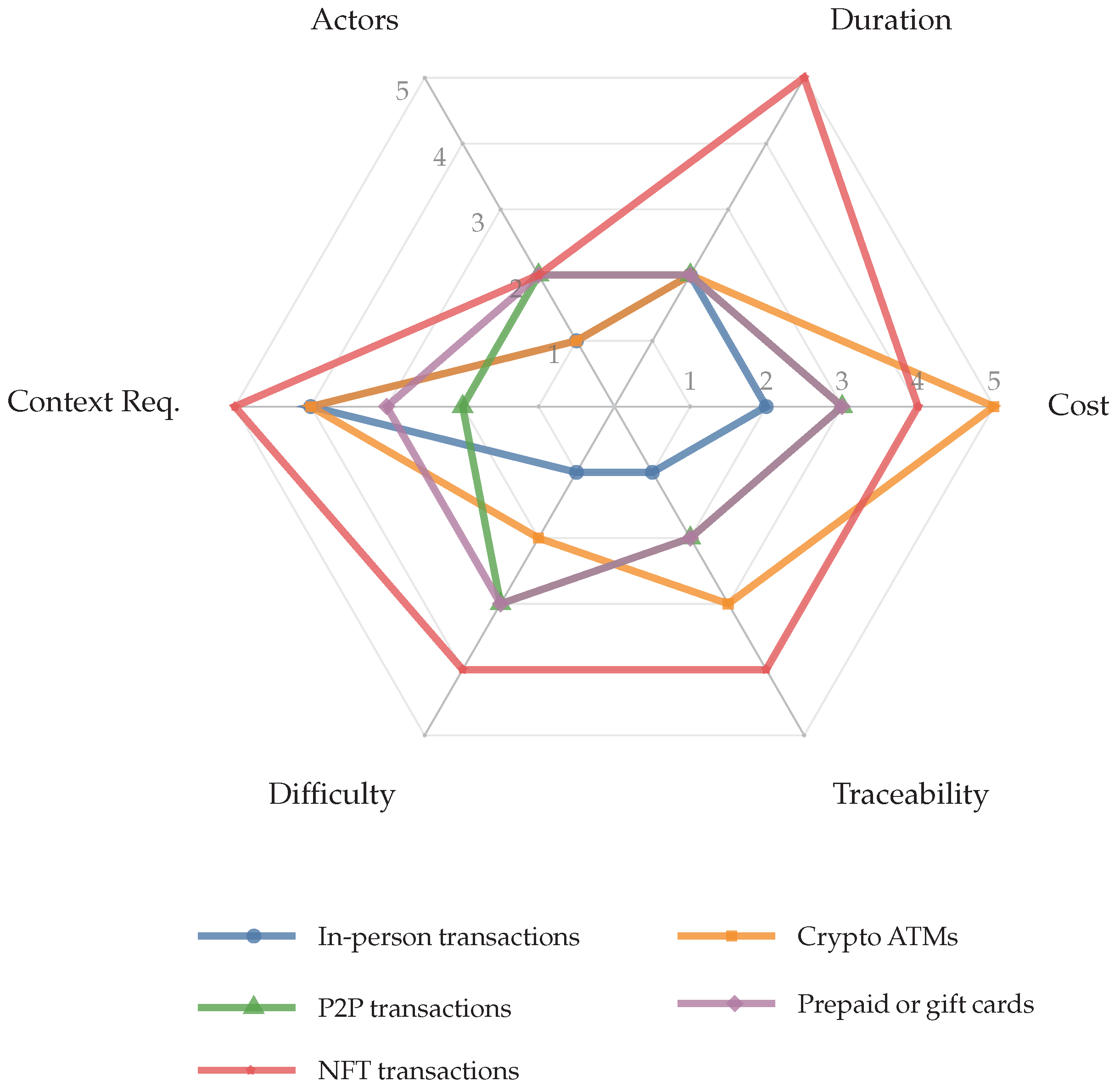

Figure 1 provides a graphical summary of the results across six dimensions: duration, actors, contextual requirements, difficulty, traceability, and cost.

Two distinct profiles emerge from the analysis. The first comprises low-impact methods—in-person transactions, P2P transactions, and prepaid gift cards—which are characterised by short duration (2), few actors (1–2), relatively low difficulty (1–3), low to moderate traceability (1–2), and intermediate costs (2–3). The second profile includes more demanding methods—crypto ATMs and NFT transactions—where both costs (4–5) and contextual requirements are higher. Within this group, NFT transactions show particularly high contextual requirements and duration (5), along with high traceability (4), whereas crypto ATMs are fast (2) but very costly (5). In both profiles, the number of actors remains low, confirming the limited participation typical of these methods.

5. Layering Stage

The layering stage assessment follows the same six-dimensional framework introduced in the methodology, with the methods selected for this stage, using the same evaluation criteria.

5.1. Duration

Since layering with NFTs requires carrying out a larger number of transactions to create additional layers, the overall duration increases proportionally with the number of transactions performed. This includes the time spent on research and selection, choosing whether to buy or sell, and configuring the necessary parameters. When auctions are used for specific NFTs, the process can exceed 10 h. Consequently, if multiple NFTs are involved, the total time required becomes considerable. The duration of tumblers or mixing services varies considerably and depends on several factors. Different services operate at different speeds, and in general, the more elaborate the operation, the longer it takes—and the greater the level of anonymity achieved. Many tumblers also introduce delays and randomness into the output times and transactions to further obscure the relationship between input and output cryptocurrencies. Depending on these factors, as well as the types of cryptocurrencies, blockchains, and transaction amounts involved, the duration can range from a few minutes to several hours, or in some cases, one or more days,

Oliyaee (

2024).

A related technique, known as chain hopping, involves transferring digital assets between different blockchains. This practice may be motivated by factors such as transaction speed, fees, or privacy, as each additional hop increases the difficulty of tracing the flow of funds. On average, a single exchange can take between 5 and 60 min, depending on the specific conditions of the blockchain networks involved. In worst-case scenarios, the total duration can be estimated as the number of hops multiplied by an average of one hour. To enhance privacy, it is reasonable to assume that more than three, and possibly more than six, hops may be used, resulting in a minimum total duration of approximately six hours, as reported in

Merkle Science (

2023);

SimpleSwap (

n.d.).

The duration of different layering methods varies considerably depending on the techniques employed and the characteristics of the networks involved. Tumblers or mixing services, for example, display high variability due to differences in service design and operational complexity. In general, the more elaborate the operation, the longer it takes—and the greater the level of anonymity achieved. Many tumblers also introduce deliberate delays and randomness into output times and transactions to further obscure the relationship between input and output cryptocurrencies. As a result, depending on these factors, as well as the types of cryptocurrencies, blockchains, and transaction amounts involved, the duration can range from a few minutes to several hours, or in some cases, one or more days, as noted in

Oliyaee (

2024).

Another commonly used method in the layering stage involves DEXs, which enable users to exchange cryptocurrencies directly without relying on a central authority, as described in

Coinbase (

n.d.). Most DEX transactions occur within the same blockchain, although some platforms support cross-chain exchanges, cf.

Coincarp (

2023). The duration of these transactions depends on several factors, including network congestion, the blockchain used, and the gas fees selected. While certain transactions may be completed within minutes, particularly on faster networks such as Binance Smart Chain, the processing time can increase significantly under congested network conditions or when users choose lower gas fees to reduce costs, see

Coincarp (

2023);

Groves (

2024). On average, Ethereum transactions take between 1 and 5 min

Hendy (

2024b), whereas Bitcoin transactions typically range from 30 min to 2 h

Draper (

2024). These times vary depending on the network state and the specific DEX platform used, as in

Coinbase (

n.d.). When multiple operations are performed as part of the layering process, the total duration can extend to several hours. For instance, assuming at least three transactions, the expected duration would range between 3 and 6 h, as estimated in

Coincarp (

2023);

Draper (

2024).

Finally, regarding crypto online casinos, deposit and withdrawal times are generally perceived to be fast, see

Bitcoin.com (

2024). However, an examination of the terms of use of platforms that do not explicitly implement extensive KYC procedures reveals that withdrawal times can often be longer than advertised, see

Betpanda (

2024b). Many casinos indicate that the average processing time for most cryptocurrencies is only a few minutes. Nevertheless, if a transaction requires additional review, withdrawals can be delayed for up to 24 h, as noted in

Lucky Block (

2024). In some cases, according to

Betpanda (

2024b), platforms also reserve the right to postpone withdrawals in situations such as insufficient cryptocurrency reserves. While the typical withdrawal duration remains within a few minutes, these exceptions show that under certain circumstances, such as manual reviews, the processing time can be significantly extended, reaching up to 24 h, as noted in

Bitcoin.com (

2024).

5.2. Actors

The number and type of actors involved in layering methods vary depending on the technique employed. In the context of NFT transactions, a typical operation involves a buyer and a seller interacting through a platform. However, when multiple transactions are carried out, the buyer may also assume the role of the seller in subsequent exchanges.

For mixers or tumblers, the number of participants can be significantly higher. This process involves the initial user, other users whose cryptocurrencies are pooled together, and the entity operating the service, which is responsible for ensuring the efficiency and security of the mixing process. Although there is no centralised regulation, the operation of these services relies on secure practices to protect transaction privacy and ensure the effective mixing of funds, cf.

Cervantes (

2023);

Jafery and Nelson (

2022).

Similarly, chain hopping involves only the user and the associated services, resulting in a relatively low number of participants. DEX transactions follow a similar structure to those previously described, typically involving between three and five actors per transaction. Overall, these methods meet the criteria for low participation.

Finally, in the case of crypto online casinos, the primary actors involved are usually two: the user, who owns the cryptocurrency wallet, and the casino itself. However, intermediaries may sometimes participate, particularly during the withdrawal process, to facilitate specific aspects of the transaction. These intermediaries may handle blockchain confirmations, currency conversions, or security checks. In some cases, they temporarily hold funds or perform additional verification for large withdrawals to prevent suspicious activity, ensuring smooth and secure transactions, as noted in

Crypto News (

2024);

Lang (

2023).

5.3. Contextual Requirements

The contextual requirements for layering methods are relatively similar across different techniques, typically involving a computational device, internet access, and a digital wallet as the basic prerequisites. For NFT transactions, these elements are essential: a digital wallet for storage, a device for accessing the platform, and a stable internet connection. Although these constitute the minimum requirements, additional measures may be implemented to enhance privacy during transactions.

Mixing services or tumblers require the same basic setup—a device, internet connection, and digital wallet—to initiate and complete the mixing process. Similarly, chain hopping relies on identical prerequisites to execute transfers between different blockchains effectively.

When using DEXs, users must also have a computational device, internet connection, and digital wallet, as these platforms typically do not provide built-in storage solutions. As with mixing services and chain hopping, optional privacy-enhancing measures may be adopted to strengthen anonymity.

Finally, participating in cryptocurrency casinos requires internet access, a device, and a digital wallet to conduct direct transactions in cryptocurrencies. Although physical presence is not required, additional security tools may be used to ensure greater anonymity and protection during the process.

5.4. Difficulty

The level of difficulty associated with different layering methods varies considerably depending on the technical knowledge required and the complexity of the operations involved. Conducting a single NFT transaction typically requires a moderate level of understanding, depending on the user’s general profile. However, engaging in multiple NFT transactions across different platforms and using various sales methods is considerably more demanding, resulting in an above-average difficulty level.

Using a mixing service or tumbler presents a moderate level of difficulty. Users must first understand how the service operates, including its transaction flow and privacy mechanisms. Once this understanding is achieved, the overall difficulty largely depends on the platform’s usability and the user’s familiarity with it.

In contrast, chain hopping is considered a highly complex technique, rated at the greatest difficulty level. This method requires a comprehensive understanding of multiple blockchains and cryptocurrencies, as well as the ability to operate on non-KYC platforms. Users must be familiar with different fee structures, including gas fees, transaction fees, and wallet fees, which can vary significantly across networks and services. Furthermore, chain hopping demands the ability to strategically select blockchains and services that align with specific objectives such as cost minimisation and anonymity maximisation. This requires deep knowledge of service credibility, functionality, and operational procedures. Consequently, only users with advanced expertise in blockchain technology and digital finance can effectively execute chain hopping, as discussed in

Merkle Science (

2023).

Using DEXs is generally accessible for users with a basic understanding of cryptocurrencies. However, the level of difficulty increases significantly when more complex operations are carried out during the layering stage of money laundering. This stage requires more advanced knowledge of key aspects such as cryptocurrency or token pairing, slippage adjustments, and the management of various transaction fees. Each of these elements must be carefully configured and repeated multiple times to achieve an acceptable level of privacy, increasing the overall complexity of the process.

Similarly, for users with basic knowledge of cryptocurrencies, interacting with online casinos is relatively straightforward. These platforms typically offer user-friendly interfaces and often do not require KYC verification, which simplifies the process and reduces entry barriers. Their accessible design and the lack of stringent regulatory requirements make them an attractive option for those seeking to obscure the origin of funds. However, the withdrawal process may occasionally involve vaguely defined conditions, which can require patience and a certain level of skill, for instance, when securely providing identity documents upon request.

5.5. Traceability

The traceability of layering methods depends on the degree of anonymity provided by each technique and the transparency of the underlying blockchain. While blockchain transactions are inherently public, the extent to which flows can be traced varies significantly across methods.

For NFT transactions, traceability is generally considered average. Although transactions occur on public blockchains, which provide inherent transparency, the pseudonymous nature of blockchain identities and the repeated use of multiple transactions can complicate tracing efforts.

Mixing services are specifically designed to enhance privacy by dissociating transaction records from user identities, making transactions difficult to trace. These services use algorithms to break the link between senders and recipients, thereby protecting against hacks, scams, and data leaks, as noted in

Cervantes (

2023);

Jafery and Nelson (

2022). As a result, their traceability is typically low.

Chain hopping also presents substantial traceability challenges. Despite the development of advanced analytical tools, see

Chainalysis (

2022);

TRM (

2022), and increasing regulatory efforts, the inherent differences between blockchains and cryptocurrencies make tracing cross-chain movements complex. Consequently, chain hopping currently exhibits low traceability, which can be rated at level 2.

The traceability of DEX usage during layering is considered moderate. Although DEXs do not enforce KYC, wallet addresses and transactions remain publicly visible on the blockchain, cf.

Financial Crime Academy (

2024b). Transactions occur directly between users via smart contracts, and most platforms do not adhere to AML standards, complicating full traceability, as in

Benson et al. (

2023). However, the public nature of blockchain records provides a certain degree of transparency, and repetitive transaction patterns can be detected by advanced blockchain analysis tools such as Chainalysis and Elliptic. While linking wallets to real-world identities remains a challenge, increasing regulatory pressure may improve traceability in the future as some jurisdictions move to enforce AML and KYC standards on DeFi platforms, see

Financial Crime Academy (

2024a).

For cryptocurrency online casinos without KYC requirements, traceability ranges from high for decentralised platforms to moderate for centralised ones. Decentralised casinos operate through autonomous protocols and do not directly hold user funds, allowing blockchain analysts to follow fund movements through DeFi protocols with relative ease. In contrast, centralised casinos exert greater control over user funds; once a deposit is made, funds are internally mixed and redistributed, making ownership tracing more difficult, as discussed in

Chainalysis (

2020,

2024).

Despite the absence of mandatory identity verification at registration, all deposits and withdrawals remain publicly accessible on the blockchain. Analytical tools, such as

Chainalysis (

2025);

Elliptic (

2025);

TRM (

2025), enable the detection of patterns and the flagging of suspicious activity, as noted in

Divyasshree (

2024);

Shishkanov (

2024). While linking wallet addresses to real-world identities remains challenging in less regulated jurisdictions, as noted in

Illicit Finance Initiative (

2024), many casinos include clauses in their terms of service allowing identity verification if suspicious activity is detected, as in

Betpanda (

2024a);

TG Casino (

2024). Moreover, growing regulatory pressure has led some jurisdictions to require no-KYC casinos to implement strict identity verification procedures for withdrawals, see

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (

2024). As a result, although deposits and withdrawals can be traced, the internal fund management mechanisms of centralised casinos continue to limit full traceability.

5.6. Cost

The costs associated with layering methods vary depending on the technique, the blockchain used, and the specific tools and market conditions at the time of the transaction.

In the case of NFT transactions, fees differ considerably across blockchains, as discussed in

Hendy (

2024a). Ethereum is generally more expensive, sometimes exceeding USD 10 per transaction

Webisoft (

2024), whereas on Solana, a typical transaction costs approximately USD 0.00025

Solberg (

2022). These fees fluctuate depending on network congestion and transaction complexity. In addition, platforms typically charge listing fees, currently around 2.5% of the sale price

Coindesk (

2021);

Davis (

2024), which can significantly increase the total cost.

By contrast, mixing services are comparatively cost-effective, as noted in

Cryptopolitan (

2024). Although not free, most currently charge between 0.1% and 1.5% of the amount processed

Cryptmixer (

2023);

Mixero (

2024), with some retaining a small fixed value (e.g., 0.0003 Bitcoin Token (BTC)) for each address used

Blender (

2023). Discounts are sometimes available for larger amounts

Knowledgebase (

2022), which can make this method relatively inexpensive compared to other techniques.

Chain hopping represents an intermediate case. It generally offers a favourable cost–benefit ratio when low-fee blockchains are used

Multichain (

2022), but minimising costs requires advanced knowledge and careful planning regarding tools

ApeSwap (

2023), cryptocurrencies, blockchains, and transaction timing. Tests were conducted using three hops and three different cryptocurrencies (ETH, BNB, TRX) across several non-KYC platforms, including

ApeSwap (

2023),

Multichain (

2022), and Bisq

Wiki (

2024). For operations starting with a base value of USD 1,000 in USDT on Ethereum, the final cost after three hops fell in the moderate range (2–4%), corresponding to level 3 on the cost dimension. Notably, timing plays a critical role: ETH transaction fees have decreased significantly to around USD 0.28

Caymaz (

2024), lowering overall costs compared to previous years. Nonetheless, fees remain volatile, and selecting the optimal combination of hops, blockchains, currencies, platforms, and wallets is essential to manage costs and avoid traceability.

Similarly, the cost of transactions on DEXs depends on the network, congestion levels, and platform-specific fees, as reported in

Heinrich (

2023);

Stader Labs (

2024). For example, Uniswap v3 charges 0.05%, 0.30%, or 1% depending on the selected fee tier

Docs (

n.d.), while PancakeSwap offers fees of 0.01%, 0.05%, 0.25%, and 1% depending on trading pairs and liquidity

Docs (

2022). Slippage must also be considered: this is the difference between the expected price and the execution price, typically ranging from 0.1% to 1% under normal conditions

Owl (

2021);

Stader Labs (

2024). Gas fees add further costs, especially on Ethereum during periods of high congestion, see

Heinrich (

2023);

Pepi (

2024). When executing at least three swaps in the layering stage, total costs typically fall between 2% and 4%, due to the cumulative effect of swap fees, slippage, and gas fees. For instance, three swaps on Uniswap v3 at 0.3% per swap yield 0.9% in swap fees; adding slippage of approximately 1.5% and gas fees brings the total to within this range

Docs (

n.d.);

Owl (

2021).

Finally, when considering cryptocurrency casinos, and excluding unpredictable gambling gains or losses, transaction costs are relatively low. Most non-KYC casinos charge no additional fees for deposits or withdrawals, apart from a standard 0.1% transaction fee. Some may apply additional mining or conversion fees depending on the blockchain and coin type used. Others impose special fees to deter suspicious transactions, such as 8% or a fixed minimum charge (e.g., 4 euros) for unplayed deposits. For example, a USD 1000 withdrawal with a 0.1% casino fee (USD 1), plus low-priority Bitcoin network fees of approximately USD 0.57 per deposit and withdrawal, results in a total of USD 2.14—less than 1% of the total amount. These values are dynamic and may vary depending on blockchain conditions, timing, and additional privacy measures, such as the use of privacy wallets.

5.7. Summary

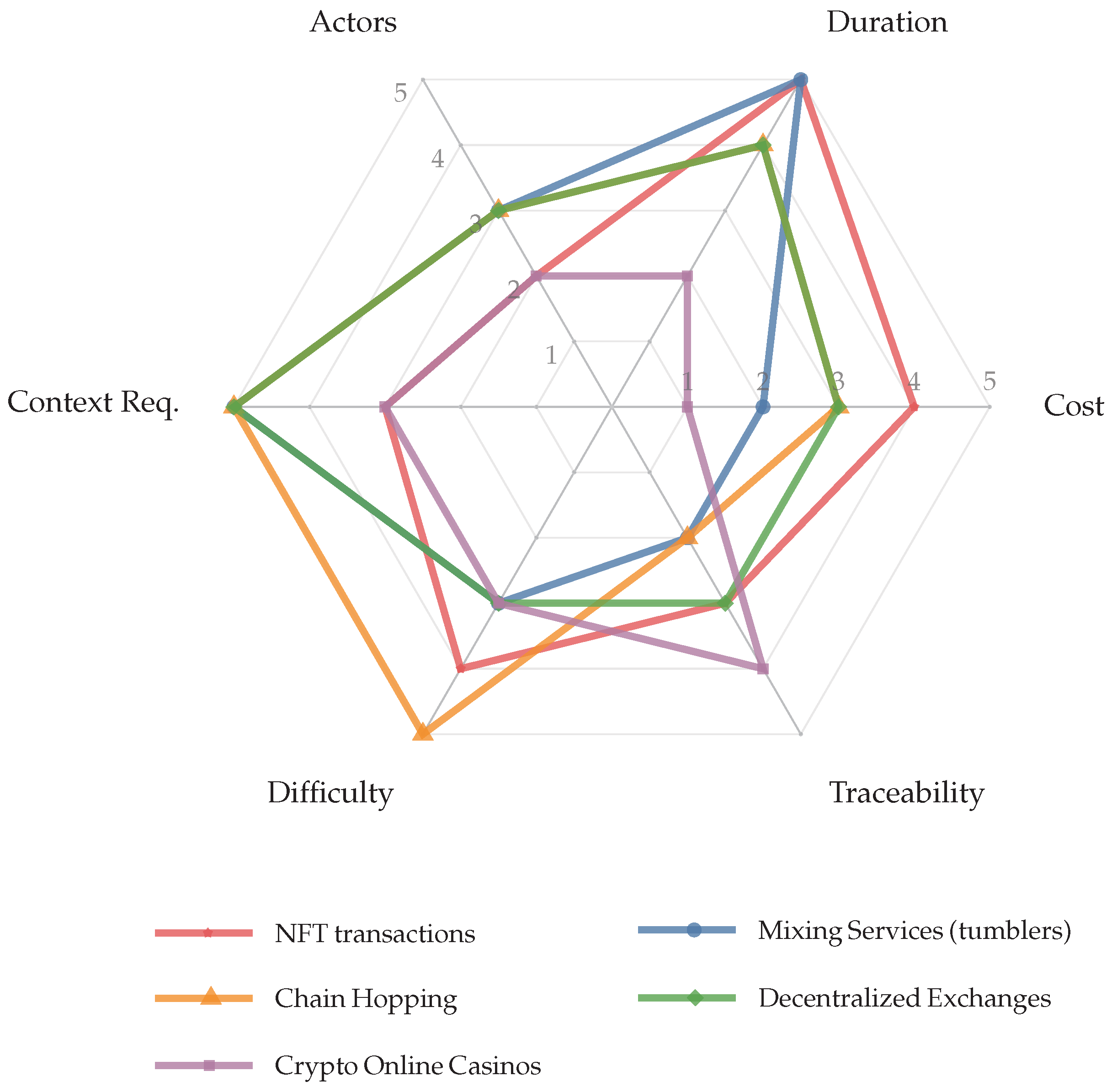

Figure 2 summarises five layering methods for money laundering (ML) involving cryptocurrencies: NFTs, mixing services (tumblers), chain hopping, DEXs, and crypto online casinos.

Among these, chain hopping stands out as the most difficult method (5), while simultaneously exhibiting low traceability (2). NFTs and mixing services are the most time-consuming (5) and require a high level of contextual knowledge (3–5), reflecting the technical and operational complexity associated with their use.

DEXs occupy an intermediate position across most dimensions (duration 4, context 5, difficulty 3, traceability 3, cost 3), primarily due to the repetition of exchange sequences during the layering process. In contrast, crypto online casinos represent a simpler option: they are fast (2) and very cheap (1), though this comes at the expense of higher traceability (4), particularly in the case of centralised services.

Across all methods, the number of actors remains relatively low (2–3), reinforcing the “lean” structure that characterises effective layering techniques.

6. Integration Stage

The layering assessment follows the same six-dimensional framework introduced in the methodology. The assessment focuses on selected integration techniques while maintaining the underlying criteria and scores to ensure comparability.

6.1. Duration

The duration of integration methods varies depending on the technique used, the platform, and the contextual factors involved. In-person transactions can typically be completed in a relatively short timeframe, usually within one hour. However, this duration may increase depending on travel distance, the time spent locating a suitable counterpart, and the necessary preparations for the transaction. Consequently, the estimated total time for an in-person transaction ranges between one and three hours.

As previously mentioned, despite their growing popularity, crypto ATMs remain geographically limited. This scarcity is particularly acute for non-KYC ATMs, especially in jurisdictions with stricter regulations, making them difficult to locate. Although the transaction itself is quick, the required research and validation efforts generally push the total duration to over one hour, as noted in

Radar Coin (

n.d.).

Similarly, decentralised P2P platforms tend to have lower liquidity than centralised ones, as discussed in

Bitget (

2023);

Ccoins (

2024). They can also be harder to locate, and once identified, finding a suitable partner and transaction of interest may take time, see

Ebonex (

2023). Additional factors, such as the negotiation of terms, procedural requirements, and configuration of external transaction parameters, further contribute to extending the overall duration. For these reasons, P2P transactions are classified at level 3 in terms of time requirements, cf.

ZoneBitcoin Editorial (

2023).

In the case of cryptocurrency conversion into prepaid or gift cards, the duration depends on factors such as the selected platform, the transferred amount, and the associated network fees, as can be inferred from

Bitrefill (

2021b);

Mempool (

n.d.). Specialised tools can expedite this process, as seen in

Bitrefill (

2021a);

Support (

2024), and higher network fees typically result in faster confirmations, cf.

Bitrefill (

2021b);

Mempool (

n.d.). Most conversions are completed within one to three hours, although in exceptional cases, the process may extend over several days, as in

Bitrefill (

2021a);

Support (

2024).

During the integration stage, converting cryptocurrency into NFTs is generally a quick process. Under normal conditions, transactions are not time-consuming, particularly when funds have been preloaded into a wallet. This method is attractive to criminals because NFTs can be sold pseudo-anonymously via online platforms, avoiding the need for the physical transfer of assets

Liu et al. (

2023). Factors such as network congestion, gas fees, and transaction confirmation times can influence duration. Direct transactions usually take between one and three hours, but auctions or congested networks may extend this to one or more days

Song et al. (

2023).

Finally, in cryptocurrency-based investments involving real-world assets (e.g., real estate or vehicles), transaction duration depends on both blockchain confirmation times and external procedural requirements. Taking Bitcoin as an example, high-value transfers typically require six confirmations, with each taking around 10 min, resulting in a total duration between 30 and 80 min under normal network conditions, as discussed in

Bitbo.io (

2020);

Lopp (

2023);

McDougall (

2024). Authors in

Buchko (

2024);

Souza (

2024) state that this interval may vary depending on network congestion or the use of second-layer settlement solutions. In addition, asset purchases often involve legal documentation, research, and negotiation, which can extend the overall process by several hours or even days.

6.2. Actors

Such as in the placement stage, in-person transactions at the integration stage typically involve only two actors: the buyer and the seller. This minimal number of participants reduces both the complexity of the transaction and the likelihood of information leakage. If a platform is used to find a buyer, however, an additional level of participation should be considered.

Similarly, transactions involving crypto ATMs are limited to the user and the machine itself, with no intermediaries or third parties required.

In truly decentralised P2P platforms, transactions occur directly between two parties—buyer and seller—without intermediaries that hold funds or control the process. Instead, the software functions as an open-source protocol rather than a central authority, resulting in a scenario with a minimal number of actors.

The conversion of cryptocurrencies into gift cards follows a similar pattern. It primarily involves the cryptocurrency holder and the entity or individual supplying the cards, generally limiting the number of participants to one or two and avoiding the need for additional intermediaries.

As in the placement stage, NFT transactions during the integration stage typically involve three actors: the NFT holder, the buyer, and the platform facilitating the exchange. Although the purpose differs at this stage—mainly the consolidation of illicit assets into the formal economy—the transactional structure remains essentially the same.

Finally, as noted in

Alli (

2024);

Cryptomus (

2024), cryptocurrency-based investments in real-world assets (e.g., real estate or vehicles) generally involve more than two actors. In addition to the buyer (investor) and the seller (or intermediary), notaries or public registry offices often participate to formalise ownership transfers, as in

Homeia (

2024);

Idealista (

2022), increasing the number of participants and, consequently, the procedural complexity.

6.3. Context Requirement

For in-person transactions, actors require internet access and a device, such as a smartphone or laptop, to facilitate cryptocurrency transfers through digital wallets. Physical presence is essential for the face-to-face exchange, introducing logistical considerations such as travel and coordination between parties.

Similarly, transactions carried out via crypto ATMs require a smartphone with a QR code reader to manage the digital wallet and access the internet. While physical presence at the ATM is mandatory, the overall technical requirements remain moderate.

In contrast, the operation of decentralised P2P platforms entails more demanding contextual requirements. Users must download and run a dedicated client, often through the Tor network, to ensure privacy, manage private keys, understand multi-signature mechanisms, and store transaction data locally. These steps go beyond merely possessing an internet connection and a wallet, requiring advanced technical skills and careful configuration to guarantee security and privacy, as shown in

Wiki (

2016).

The conversion of cryptocurrencies into gift cards presents simpler requirements. A computer or smartphone with internet access and a digital wallet is generally sufficient, and the entire procedure can be performed remotely without the need for physical presence.

Similarly, NFT transactions during the integration stage require internet access, a computing device (such as a smartphone or personal computer), and a compatible digital wallet. Physical presence is unnecessary, as the full process—from listing to sale—occurs online. Nonetheless, completing these operations securely demands above-average knowledge of the transaction process and associated tools.

Finally, cryptocurrency-based investments in physical assets typically require physical presence for on-site inspections and the signing of legal documents, see

Alli (

2024);

Cryptomus (

2024). Although digital-signature technologies can sometimes remove this requirement, attending in person generally facilitates the transaction and improves the likelihood of identifying suitable sellers, as in

Homeia (

2024);

Idealista (

2022). However, this also reduces anonymity. As a result, the contextual requirement for this method remains at level 4.

6.4. Difficulty

In-person transactions involve straightforward technical procedures, making them relatively simple to execute. However, arranging a secure meeting location and time introduces logistical challenges that require practical judgement. Moreover, meeting unfamiliar individuals for high-value currency exchanges entails additional precautions, many of which rely on everyday common sense and situational awareness.

Similarly, operating crypto ATMs is technically simple, as demonstrated by user experiences and available tutorials (

Mae 2024). The main difficulty lies in identifying genuinely non-KYC machines, which is increasingly challenging in certain jurisdictions, as shown in

Sharma (

2023).

In contrast, conducting cryptocurrency transactions on decentralised P2P platforms involves a significantly higher level of complexity, as discussed in

Bitget (

2023);

Ebonex (

2023). Users must assess counterparties’ reputations, follow secure transaction procedures, understand the underlying technologies, implement anonymity measures, compare prices and assess liquidity, and often apply additional privacy layers, cf.

Ccoins (

2024);

ZoneBitcoin Editorial (

2023). Collectively, these factors make P2P platforms more demanding than centralised alternatives, which are typically more user-friendly.

By comparison, converting cryptocurrencies into gift cards requires only a basic understanding of digital wallets and standard transaction procedures. The main considerations involve verifying the reliability of the trading partner and the trustworthiness of the platform used for partner selection. Overall, this method presents a low level of difficulty.

Converting previously layered assets into NFTs during the integration stage typically involves a moderate level of difficulty. Users must address technical considerations such as validating compatible wallet configurations, bridging across different blockchains when necessary, and understanding marketplace listing procedures. While modern platforms provide increasingly user-friendly interfaces, the need to maintain anonymity, navigate potential auctions, and manage fees and royalties adds to the complexity. Although this process is less intricate than some advanced layering techniques, it still requires sufficient knowledge of blockchain operations and NFT-specific protocols, justifying a moderate difficulty rating.

Finally, acquiring high-value physical assets with cryptocurrencies demands an intermediate level of expertise, as mentioned in

Alli (

2024);

Cryptomus (

2024). In addition to understanding wallet operations and network fees, users must navigate legal procedures, including KYC/AML verification and contractual obligations, especially for assets such as real estate or vehicles, as outlined in

Homeia (

2024);

Idealista (

2022). Although user-friendly platforms are becoming more common, accessible tools alone do not eliminate the complexity of ensuring legal compliance, mitigating fraud risks, and managing transaction-related uncertainties. As a result, the overall difficulty remains at a moderate level.

6.5. Traceability

In-person transactions offer a relatively high degree of anonymity. While blockchain records the transfer of cryptocurrencies, linking these transactions to identifiable individuals is difficult without supplementary data. The cash component remains largely untraceable unless specific AML triggers are activated, further complicating attribution.

Similarly, non-KYC ATMs hinder traceability due to the absence of identity validation mechanisms, as transfers are typically conducted through QR codes generated between the ATM and the user’s wallet, as noted in

Morgen (

2022). However, these machines are increasingly scarce, and even when they are available, they are often monitored by CCTV cameras, significantly reducing privacy levels as noted in

Radar Coin (

n.d.);

Sharma (

2023). Moreover, many non-KYC ATMs now impose ID verification for transactions exceeding certain thresholds, see

Mae (

2024).

It is important to note that blockchain transactions are never entirely anonymous. Although personal information is not collected during the transaction, all operations are permanently and publicly recorded (

Huffman 2024). Advances in forensic analysis enable the tracing and potential linking of specific transactions to individuals, particularly when blockchain data is combined with external sources such as CCTV footage or exchange records, as discussed in

Huffman (

2024);

Morgen (

2022). As a result, the traceability level for ATMs is best characterised as medium rather than low.

In contrast, decentralised P2P platforms are explicitly designed to maximise privacy, as in

Bisq Platform (

2024). Connections are typically established via privacy-enhancing networks, and no formal identification is required. Although the underlying blockchain transactions remain public, the absence of central registries or custodial intermediaries increases anonymity (

Schar 2021). Nevertheless, external factors such as payment methods or the transaction approach may reduce overall privacy in practice.

Gift card purchases generally exhibit low traceability at the point of acquisition. When specific or P2P platforms that do not enforce KYC are used, transactions can proceed with minimal identification requirements,

Elder (

2024). As discussed in

Yanik (

2024), the level of traceability depends on the policies of the issuing platform and the terms associated with the prepaid card itself. Some services, for instance, accept only an email address for low-value cards, further reducing the possibility of linking transactions to real-world identities, as shown in

Investor Ideas (

2024). However, this landscape is evolving as regulatory frameworks tighten.

For NFT transactions during the integration stage, traceability remains moderate. Although all transactions are permanently recorded on the blockchain, the pseudonymous nature of the technology requires correlating wallet addresses with real identities to establish definitive links. This typically demands access to off-chain data, such as records from centralised marketplaces or KYC procedures, as blockchain observation alone rarely suffices.

Finally, cryptocurrency-based investments in real-world assets exhibit higher levels of traceability. All such transactions are recorded on blockchains, which are pseudonymous rather than fully anonymous, and advanced forensic tools can often correlate addresses with real entities. Moreover, purchases of assets such as real estate or vehicles usually require public registration and compliance with KYC/AML regulations. These legal procedures not only verify ownership but also directly associate cryptocurrency transactions with personal identities, reinforcing traceability. To obscure this link, additional steps—such as using intermediaries or shell companies—may be taken, though these substantially increase operational complexity.

6.6. Cost

In-person transactions generally incur minimal direct costs, such as stated in

Khaliq (

2024). However, users may overlook certain additional expenses associated with cryptocurrency transactions, see

Heinrich (

2023). While transfers between wallets do not involve intermediaries or financial institutions, even for privacy-focused wallets such as Exodus, which does not charge for receiving, sending, or storing coins, as stated in

Wallet (

2023), according to

Heinrich (

2023), it is still necessary to pay the network’s transaction fees to miners or validators. Moreover, the value of the currency itself can introduce indirect costs. As depicted in

LocalBitcoin (

n.d.);

Paxful (

2024a), on platforms such as LocalBitcoins or Paxful, sellers typically pay a 1% service fee, which is reflected in the negotiated sale price.

By contrast, non-KYC ATMs, when available, are convenient but can incur exceptionally high transaction costs, often exceeding 20% of the transferred amount, see

Huffman (

2024);

Mae (

2024). This makes them one of the most expensive methods in the integration stage.

For decentralised P2P platforms, transaction costs vary with market conditions and liquidity. For instance, on Bisq, combined trading fees for BTC average around 1.3% (0.15% for makers and 1.15% for takers), with a minimum fee of 0.00005 BTC, while Bisq Token (BSQ) trading fees average 0.65% (0.075% for makers and 0.575% for takers), with a minimum of 0.03 BSQ, cf.

Wiki (

2024). Although lower than the fees charged by some non-KYC ATMs, they are generally higher than those on centralised exchanges. Furthermore, according to

Stadelmann (

2023), constrained liquidity often leads to buy and sell orders being priced below the reference market value, as illustrated by trades where BTC/USD rates were observed to diverge from the spot price due to limited liquidity and user-specific conditions. These factors can result in effectively higher costs compared to centralised platforms, even if nominal fees appear moderate.

Gift card purchases typically involve moderate costs. In addition to blockchain transaction fees, which influence confirmation times depending on fee levels, price discrepancies between the cryptocurrency’s spot value and the actual amount charged for the card must be considered. For example, in tests conducted in December 2024, with BTC/EUR valued at EUR 89,010.53, two offers were less than 1% above market rate, as reported by

Offerings (

2024a;

2024b), while others reached up to 13%, as in

Paxful (

2024b);

Vender (

2024). These variations depend on factors such as platform policies, promotional campaigns, liquidity shortages, and volatility. Overall, observed costs typically range from 2% to 4%, though more extreme cases are possible. This variability means that cost estimates for gift card conversions should be treated as indicative and subject to change as market conditions evolve.

For NFT transactions at the integration stage, costs vary significantly depending on the blockchain and platform selected. On Ethereum, gas fees can exceed 10 USD per transaction during periods of congestion, as discussed in

Solberg (

2022);

Webisoft (

2024), whereas Solana transactions typically cost around USD 0.00025,

Hendy (

2024a). Listing fees, commonly around 2.5% of the final sale price, and royalties to creators, as mentioned in

Coindesk (

2021);

Davis (

2024) further increase total expenses. Although integration usually involves fewer transactions than layering, the overall cost can escalate rapidly, particularly for high-value assets or during periods of network congestion.

Finally, when cryptocurrencies are used to acquire high-value physical assets, such as real estate, total costs often exceed 4% of the transaction value, as noted in

Associação dos Profissionais e Empresas de Mediação Imobiliária de Portugal (

2024);

Pires and Madeira (

2021). These figures include not only on-chain expenses such as gas fees—which may rise substantially during congestion, as noted in

Günen (

2024) but also off-chain costs like transfer taxes, stamp duty, registration fees, and intermediary commissions, as discussed in

Cryptomus (

2024);

Idealista (

2022). In large transactions, legal and administrative costs scale proportionally with asset value, making this one of the more expensive integration methods overall, as shown in

Arch Lending (

2025);

Homeia (

2024).

6.7. Summary

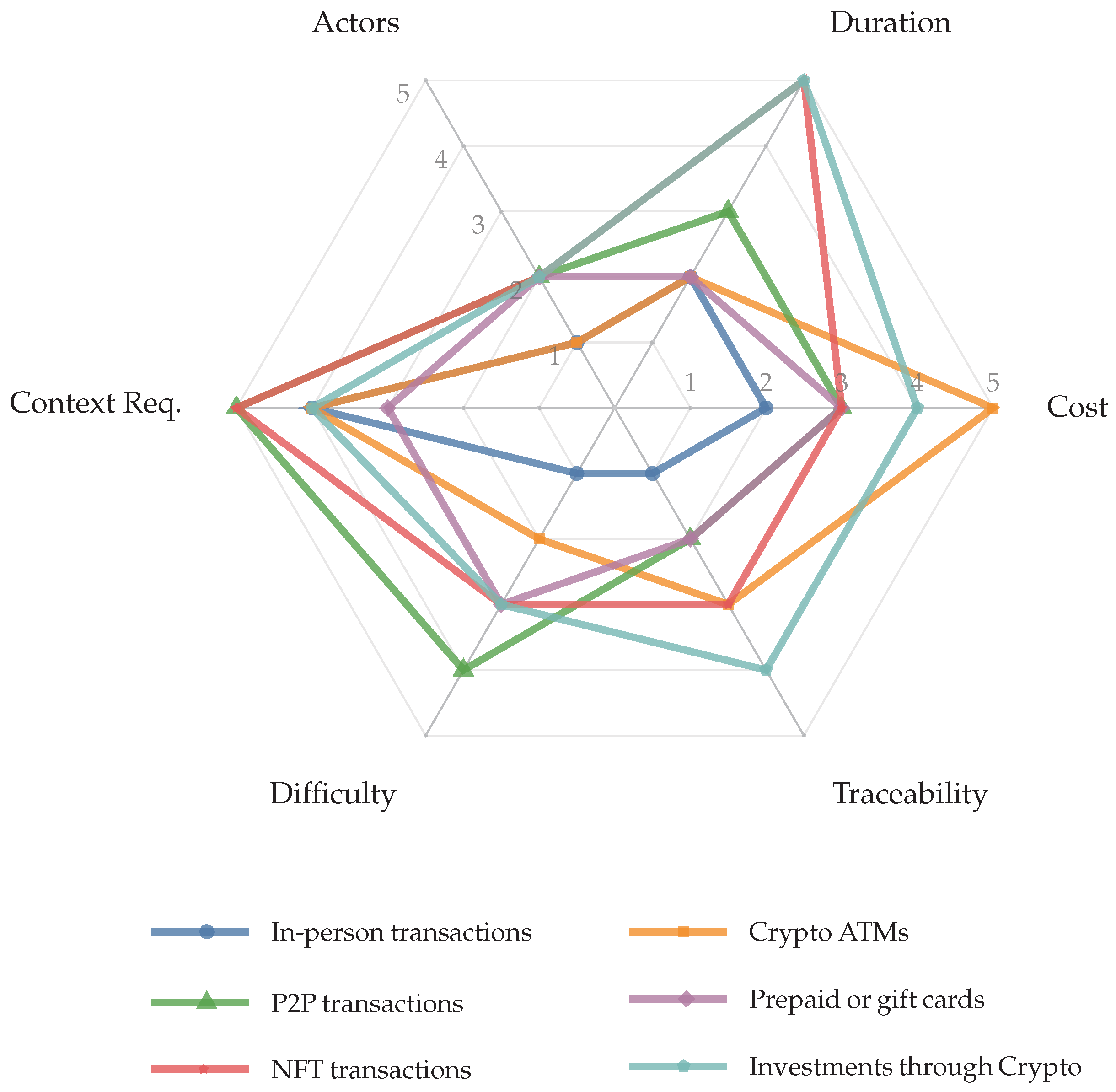

Figure 3 presents the six methods used during the integration stage—namely, in-person transactions, crypto ATMs, P2P exchanges, prepaid/gift cards, NFTs, and investments through cryptocurrency, evaluated according to the same six dimensions employed in the previous stages.

As observed in the placement stage, two distinct profiles emerge. On the one hand, there are fast, low-cost methods (in-person transactions and gift cards), characterised by short duration (2), relatively low costs (2–3), and low traceability (1–2). On the other hand, more formal and visible methods (NFTs and investments through cryptocurrency) involve a longer duration (5), higher contextual requirements (4–5), and increased traceability (3–4), particularly when off-chain records and KYC/AML procedures are involved.

Within the first group, crypto ATMs stand out as a hybrid case: they offer fast execution (2) but are associated with very high costs (5) and medium levels of traceability (3). P2P transactions, meanwhile, demand greater contextual understanding and technical expertise (5 and 4, respectively) while maintaining a moderate cost (3) and a comparatively high degree of privacy (2).

Across all methods, the number of actors tends to remain low (1–2), although investments through cryptocurrency may involve additional participants depending on the asset type and the applicable legal framework.

7. Discussion

From the overall analysis on the methods surveyed, it is possible to recognise differences in each dimensions and stages.

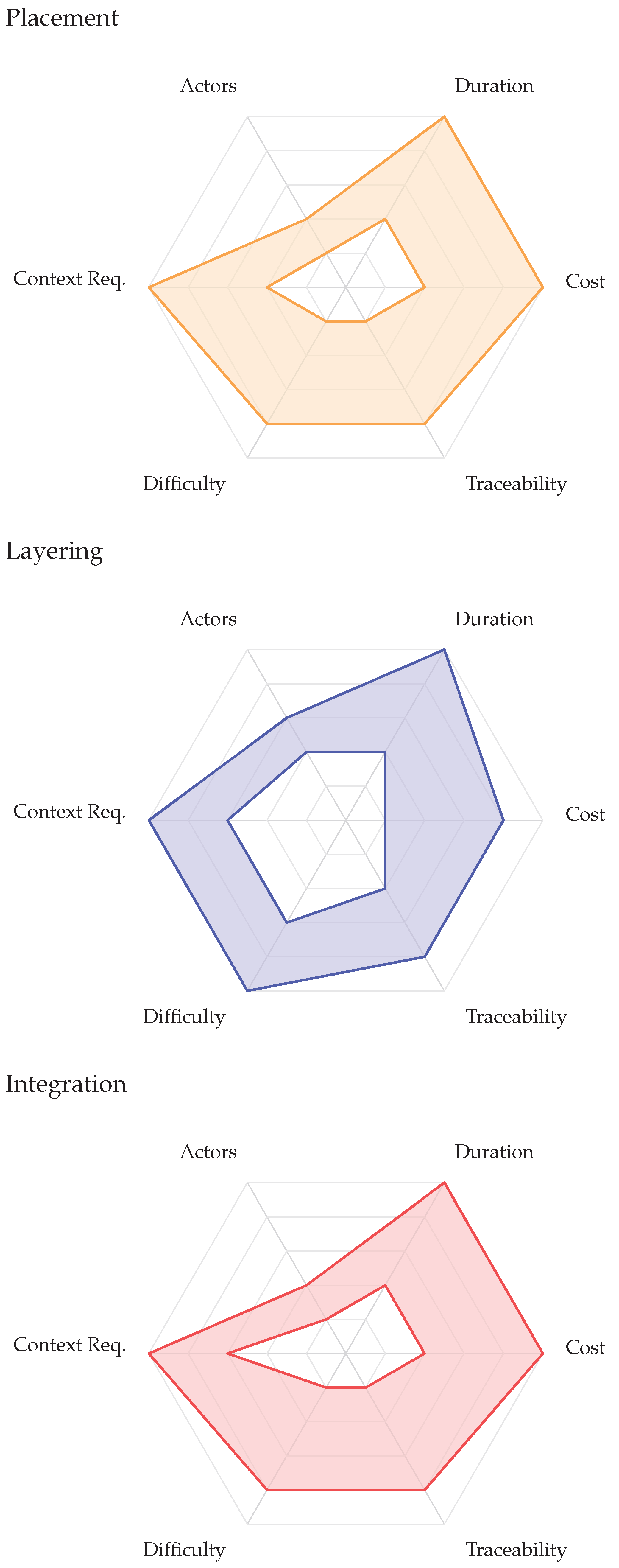

Figure 4 groups the methods per stage, using the range from the minimum and the maximum scores obtained.

From the results, it is possible to conclude that some dimensions present wider bands, which indicate more variability among methods, while others present more consistency. In the placement stage, all dimensions, except the authors, present the same variability. In the layering stage, the maximum variability is presented by duration and cost dimensions. In the integration stage, the maximum variability is achieved in all dimensions except actors and context requirements. This greater variability in some dimensions may be understood as wider options on methods to deploy the money laundering illicit activities.

In the placement stage, the methods reach the maximum of the score for duration, cost, and context requirements dimensions. The actors dimension presents more consistency, presenting scores ranging from 1 to 2. In the layering stage, the methods present less dimension variability, with a maximum achieved in duration, difficulty, and context requirements. The dimensions reaching the maximum of the score are the following: duration, cost, and context requirements. The actor dimension presents the same consistency as in the placement stage; however, in this case, it presents scores ranging from 2 to 3. The analysis reveals that layering stage techniques, such as mixers/tumblers and chain hopping, offer enhanced privacy, albeit requiring a high level of technical expertise. Conversely, non-KYC crypto ATMs tend to be easier to use, but they charge high fees and are increasingly subject to AML-related restrictions. In the integration stage, and following the results of the placement stage, the methods reach the maximum of the score for duration, cost, and context requirement dimensions. This similarity was expected since all methods, except investments through cryptocurrencies, from the placement stage are symmetric to the ones on the integration stage. However, these results present less variability in the context requirement dimension. The actor dimension presents the same consistency as in the previous stages, in this case, with scores ranging from 1 to 2.

Also, it can be concluded that the choice for a method in each stage is a trade-off between convenience (speed and simplicity) and the risk of exposure (heightened traceability, higher fees, and potential KYC requirements). Thus, methods that seem simpler might, in practice, lead to greater exposure, whereas more technically advanced solutions can better conceal the origin of funds but demand more effort, planning, and knowledge.

The restrictions introduced by legislation such as AMLD directives and the MiCA Regulation have intensified the scrutiny of money laundering methods. This is evident, for instance, in how most of the platforms and entities surveyed, namely online casinos and crypto ATM networks, have implemented AML controls in their terms of service.

Nonetheless, increasingly sophisticated data analysis tools, artificial intelligence, pattern detection, and continuous monitoring are becoming ever more essential in identifying suspicious activity and illicit transactions involving cryptocurrencies. These technologies complement regulatory obligations and help mitigate criminal uses of the crypto ecosystem.

The rapid evolution of the cryptocurrency ecosystem poses a constant challenge. The emergence of new DeFi technologies, privacy protocols, and regulations may render certain findings obsolete if more disruptive innovations appear. Such shifts in context often necessitate revisiting the collected data and updating analyses accordingly.

Although the study does not introduce a new dataset of transaction records, the patterns highlighted by the six-dimensional assessment are in line with descriptions found in publicly available typology reports, scientific works, and other important sources involving cryptocurrencies. These sources frequently refer to the use of exchanges, mixing and tumbling services, cross-chain transfers, and gambling platforms in ways that reflect the same trade-offs between accessibility, cost, and exposure to detection identified in our profiles. This alignment suggests that the comparative results capture salient aspects of how different laundering techniques operate in practice.

8. Conclusions

This study proposed a parametric assessment of various money laundering techniques using cryptocurrencies, covering the three common stages of money laundering (placement, layering, and integration). The following six dimensions were defined: actors’ involvement, duration, cost, traceability, difficulty, and context requirements. This dimension-based analysis aims to bring to light how the methods are spread by these dimensions, with a structured understanding of the main characteristics and risks associated with each method.

By objectively comparing methods, from simpler, low-volume ones such as gift card transactions, to those more complex and technically demanding, such as chain hopping, this work aims to provide useful indicators of where monitoring efforts might be best prioritised. Additionally, some regulatory influence has been observed, particularly in methods and platforms like online casinos or crypto ATMs, which are more directly exposed to oversight.

The assessment should therefore be seen as a snapshot of the state of practice and regulation as of early 2025. Given the rapid evolution of decentralised finance, second-layer solutions and stablecoins, an important avenue for future work is to reapply and extend this framework at different points in time and in specific jurisdictions, combining it with empirical transaction data to study temporal trends in difficulty, traceability, and risk.