Abstract

This study investigates the relationship between emission performance, environmental disclosure, and firm value in Southeast Asia, where climate-related risks are increasingly shaping corporate strategies and investor decisions. Using a sample of 206 listed firms from Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand over 2022–2023, the analysis applies a 12-item environmental disclosure index and emission scores from Refinitiv LSEG, with firm value measured by the price-to-book ratio. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is employed to test causal pathways, complemented by ANOVA to explore cross-country and cross-industry differences. The results show that emission performance significantly enhances environmental disclosure, consistent with signaling theory and the resource-based view, where superior performance motivates firms to communicate credibility and differentiate themselves. However, environmental disclosure does not exert a significant direct effect on firm value, highlighting a disclosure–value gap in emerging markets where reporting remains heterogeneous and less valued by investors. Country-level differences suggest stronger performance in Indonesia, Singapore, and Thailand compared to Malaysia, while industry-level analysis shows that health care, energy, and financial firms lead in both emission management and disclosure. The findings provide implications for regulators, firms, and investors by underscoring the need for stronger ESG reporting frameworks and more credible disclosure practices to strengthen value relevance.

1. Introduction

Climate-related risks are projected to become the most critical global risks in the coming decade, occupying the top four positions in the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report: extreme weather events, biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse, changes in Earth systems, and natural resource shortages (Auerswald et al. 2017). The principal driver of climate change is greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from human activities, with carbon dioxide (CO2) being the most dominant contributor. Rising GHG emissions accelerate global warming, which in turn intensifies climate variability and amplifies risks to economic and social systems. For firms, these emissions represent not only an environmental concern but also a critical climate risk that threatens business continuity, financial stability, and long-term corporate value (Kalogiannidis et al. 2024).

Global awareness of these risks underpins major international initiatives such as the Paris Agreement, adopted in 2015 under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Paris, France. Effective since 4 November 2016, the agreement aims to strengthen global resilience by limiting the rise in global temperature to well below 2 °C, and preferably to 1.5 °C (Huang et al. 2024). Countries are required to submit and periodically update their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) every five years. In the same year, the United Nations also introduced the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with objectives that include eradicating poverty and inequality, addressing climate change, and fostering sustainable development worldwide (Preston 2020). Building on these global commitments, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) introduced IFRS S1 and IFRS S2 in 2023 to establish a standardized global framework for sustainability and climate-related disclosures. IFRS S1 provides general requirements for sustainability-related financial information, while IFRS S2 specifically focuses on climate risks and opportunities. These standards aim to ensure that companies disclose consistent, comparable, and decision-useful information on how climate risks affect business performance and value creation (Pratama et al. 2024). Their adoption represents a crucial step in translating the objectives of the Paris Agreement and SDGs into corporate-level accountability, thereby promoting greater transparency and risk awareness in global and regional markets, including ASEAN.

Southeast Asia is at a pivotal point in the global response to climate change. The region faces increasing GHG emissions due to fossil fuel–dependent industrial growth and large-scale deforestation. Projections indicate that global emissions under current NDC targets may continue rising until 2030, potentially increasing global temperatures by 2.1–3.9 °C by 2100 (Suwandaru et al. 2024). The ASEAN Centre for Energy estimates that energy sector emissions in Southeast Asia could increase by 34–147% between 2017 and 2040, with climate damages likely to far exceed the cost of prevention (Derouez and Ifa 2025). The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (IPCC6AR) highlights Southeast Asia as one of the most vulnerable regions, facing risks such as sea-level rise, heat waves, droughts, and intensified extreme rainfall (Handayani et al. 2022). Despite slower warming compared to the global average, the region is experiencing faster sea-level rise, endangering coastal areas home to approximately 450 million people. Alarmingly, nearly 75% of the 25 cities most at risk from sea-level rise are located in Asia, many of them in Southeast Asia (Beirne et al. 2021). These dynamics underscore the urgent need for adaptation and mitigation policies.

Southeast Asian governments have made varying commitments to net-zero emissions, although implementation challenges remain (Bakker et al. 2017; Overland et al. 2020). Indonesia, the largest economy in the region, has set a net-zero target for 2060 while continuing to rely on coal for around 60% of its electricity generation. Malaysia has committed to a 45% reduction in emission intensity by 2030, while simultaneously planning further coal expansion. Singapore, warming 80% faster than surrounding regions over the past seven decades, targets net-zero emissions in the second half of the century. Thailand has only recently developed its net-zero strategy in preparation for COP26. These commitments signal growing regional awareness of sustainability, yet the transition is constrained by financial limitations and ongoing fossil fuel dependence (Tangang et al. 2018).

At the corporate level, firms face mounting pressure to align with sustainability agendas through environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices. Corporate sustainability has emerged as a central theme in business and management research, with firms increasingly incorporating environmental and social considerations into their operations and disclosures (Kourula et al. 2017). ESG practices are now viewed as both legitimacy strategies and sources of competitive advantage in global markets (Abdul Rahman and Alsayegh 2021). Legitimacy theory suggests that environmental disclosure helps firms secure social support and operational continuity (Hamad et al. 2023), while signaling theory highlights disclosure as a mechanism for sending positive signals of commitment to stakeholders (Rudyanto and Pirzada 2021). Institutional pressures have further accelerated disclosure practices; for example, Singapore mandates annual ESG reporting, reflecting growing global and regional regulatory demands (Liu et al. 2019).

Nevertheless, environmental disclosure practices remain uneven across countries. Prior studies attribute this to inconsistent reporting frameworks, limited readability, weak stakeholder pressure, governance shortcomings, regulatory gaps, and structural constraints such as limited awareness, high costs, lack of training, and insufficient government initiatives (Laskar and Maji 2016; Adhariani and de Villiers 2019; Adhariani and du Toit 2020; Thomson et al. 2015; Tran and Ha 2023; Wichianrak et al. 2022; Dissanayake et al. 2021). Evidence from Southeast Asia suggests that sustainability reporting is highly variable and often weak due to limited regulatory enforcement and low corporate understanding of ESG issues (Kono et al. 2023).

Empirical findings on the determinants and consequences of environmental disclosure are also inconsistent. For instance, Amidjaya and Widagdo (2020) argue that family ownership weakens the effectiveness of governance in enhancing disclosure, while Qosasi et al. (2022) find that family firms are more sustainability-oriented, consistent with stewardship theory. Sumarta et al. (2023) show that foreign and state ownership matter, whereas family ownership does not. Differences in corporate characteristics, weak stakeholder pressure (Adhariani and de Villiers 2019), and variations in legal and cultural contexts (Tran and Beddewela 2020) contribute to these mixed results. From an agency theory perspective, disclosure reduces information asymmetry between managers and stakeholders (Jamil et al. 2021). However, in many Southeast Asian contexts, weak external and internal pressures raise questions about what truly drives firms to improve disclosure.

Among the possible determinants, the emission score represents a particularly important and underexplored factor. As an externally verified measure of corporate performance and transparency in managing emissions, it captures both actual environmental management and disclosure practices. From a resource-based view (RBV), superior emission scores reflect valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN) capabilities such as technological innovation in emission reduction and efficient production processes (Mailani et al. 2024). These capabilities not only mitigate environmental risk but also create long-term competitive advantages. From a signaling theory perspective, firms with higher emission scores are more likely to disclose environmental information extensively as a means of signaling their superior environmental management and reducing risk perceptions.

The impact of disclosure on firm value is also debated. Some Indonesian studies show that disclosure has little direct effect on firm value (Utomo et al. 2020; Noor and Ginting 2022), whereas others emphasize its positive role in markets with higher ESG awareness (Al-Tuwaijri et al. 2004; Cahan et al. 2016; Gerged et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2020; Aboud and Diab 2018; Cai et al. 2024). These findings collectively suggest that disclosure acts as a mechanism for mitigating reputational and market risks, improving investor confidence, and enhancing firm value (Orlitzky et al. 2003).

Building on these gaps, this study analyzes the relationship between emission scores, environmental disclosure, and firm value in four ASEAN countries—Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand—during 2022–2023. There are arguments that emission performance represents a critical form of climate-related risk management, while disclosure serves as both a signaling and legitimacy mechanism to reduce uncertainty and risk perceptions in capital markets. By employing Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), this research provides empirical evidence on how climate-related emission risk and environmental disclosure jointly influence firm valuation in emerging economies.

This study contributes in several ways. First, it extends climate-risk literature by showing how corporate emission management and disclosure serve as mechanisms for mitigating climate-related risks. Second, it offers insights for investors by linking transparency and emission performance to reduced investment risk and enhanced firm value. Third, it informs regulators by providing empirical evidence to support stronger environmental reporting frameworks. Finally, it benefits broader society by demonstrating the role of corporate disclosure in accountability and sustainability.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and theoretical background. Section 3 outlines the research methodology, including sample selection, variable measurement, and analytical techniques. Section 4 presents the empirical results. Section 5 discusses the findings in relation to theory and practice, and Section 6 concludes with implications, limitations, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Sustainability Risks Theory

Building on complementary lenses from stakeholders, agencies, resource-based view (RBV), and signaling theories, we conceptualize sustainability as a multi-dimensional risk domain that shapes firms’ exposure to climate-related uncertainty and their strategic responses. From the stakeholder perspective, corporate survival depends not only on creating shareholder value but also on managing relationships with diverse stakeholder groups—investors, creditors, employees, customers, suppliers, regulators, communities, media, and NGOs—whose claims vary by power, legitimacy, and urgency (Pedrini and Ferri 2019). Traditional financial reporting is insufficient for these heterogeneous information needs; sustainability reporting emerges to address social and environmental dimensions. As public awareness of ESG grows, stakeholder pressure for transparency and accountability intensifies, prompting broader non-financial disclosure (Friedman and Miles 2006; Eccles and Serafeim 2013). Responsiveness to stakeholder expectations helps firms secure social legitimacy, reputational capital, and long-term support (Carroll and Shabana 2010; Du et al. 2010).

Agency theory adds that sustainability disclosure mitigates information asymmetry between managers and stakeholders by credibly communicating environmental performance and risk management (Jamil et al. 2021). In settings where monitoring and external pressures are weak, agency problems heighten uncertainty around environmental risks, raising the value of verifiable disclosure to reduce monitoring costs and perceived risk (Bae et al. 2018).

From Legitimacy Theory, disclosure functions as an internal strategic response aimed at aligning corporate conduct with prevailing social norms to sustain socio-political acceptance and operational continuity (Del Gesso and Lodhi 2024). When public, regulatory, or media scrutiny rises around ESG, firms disclose not merely to comply but to reaffirm congruence with societal expectations, thereby buffering reputational and regulatory risks (Deegan 2002; O’Donovan 2002; Omran and Ramdhony 2015).

The RBV reframes sustainability capabilities—such as low-emission operations and high-quality disclosure—as strategic, intangible assets that can satisfy VRIN criteria: valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (Tehseen and Sajilan 2016). Effective emissions management (e.g., cleaner technologies, efficient processes) signals process excellence and operational resilience, while comprehensive, credible environmental disclosure builds distinctive reputation and investor trust that rivals struggle to replicate (Orlitzky et al. 2003; Eccles et al. 2014; Kurnia et al. 2020). Such capabilities can attract ESG-aware investors and support higher firm value.

Finally, signaling theory explains how firms reduce market uncertainty around sustainability risks: organizations with superior private information about environmental performance transmit credible signals through more extensive, decision-useful disclosure (Bae et al. 2018). In capital markets, these signals help investors reprice climate-related risk, potentially lowering perceived risk premia and improving valuation (Moussa and Elmarzouky 2024). Taken together, these perspectives position environmental performance and disclosure as integral mechanisms of risk mitigation—managing stakeholder and legitimacy risks, agency frictions, and market uncertainty while developing inimitable capabilities that underpin long-run resilience.

2.2. GHG Emissions as a Source of Corporate Risk

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions—principally CO2 alongside CH4 and N2O—are central to global climate change and constitute a direct business risk through physical impacts, transition pressures, and tightening regulatory scrutiny (Homroy 2022). Emissions management is therefore a salient indicator of a firm’s environmental commitment and operational preparedness amid accelerating decarbonization (Cadez et al. 2018). In empirical settings, the emission score operationalizes this construct as part of the environmental pillar within the LSEG (formerly Refinitiv) ESG framework, capturing both performance in managing GHG emissions and the transparency of related disclosures (Tamimi and Sebastianelli 2017; Arif et al. 2023). The score aggregates 22 indicators (e.g., CO2 emissions, reduction policies, targets) drawn from publicly verifiable sources—annual and sustainability reports, corporate websites, CSR reports, exchanges and regulators, and media/NGOs—collected by dedicated ESG analysts. Methodologically, quantitative metrics (e.g., total CO2) are percentile-ranked within industries (lower emissions → higher score), while Boolean indicators (e.g., presence of policies) are scored as 1/0 with polarity settings and sector-materiality weights; the composite is scaled 0–100 and mapped to D− to A+ grades. The framework emphasizes transparency, verifiability, materiality, and data-driven assessment while attenuating size bias and weighting for disclosure quality.

Interpreted through RBV and signaling lenses, higher emission scores reflect VRIN-consistent capabilities—process efficiency, cleaner technology adoption—and constitute credible signals of lower climate risk exposure, enhancing stakeholder confidence and market assessments. In contrast, weak emission performance elevates transition, regulatory, and reputational risks, potentially increasing the firm’s risk premium in capital markets (Singhania and Saini 2021; Kalyani and Mondal 2024).

2.3. Corporate Environmental Disclosure

Corporate environmental disclosure encompasses public reporting on environmental impacts, performance, policies, and strategies across channels such as annual and sustainability reports (Clarkson et al. 2008). Typical content areas include energy use, GHG emissions, waste, resource utilization, compliance, conservation initiatives, and targets (Cho and Patten 2007; Deegan 2002; Raimo et al. 2022). Theoretically, disclosure supports legitimacy by evidencing alignment with societal norms satisfies stakeholder information demands, and fulfills accountability obligations to a wider public. Empirically, more transparent and comprehensive disclosure can operate as a risk-mitigation tool by reducing information asymmetry and reputational uncertainty, with downstream implications for firm value (Al-Tuwaijri et al. 2004; Saraite-Sariene et al. 2019). In line with Stakeholder, Legitimacy, RBV, and signaling arguments, broader, credible disclosure is expected to reduce perceived sustainability risk, enhance investor confidence, and support higher valuations, especially where market participants increasingly integrate ESG into risk assessment (Eccles et al. 2014).

In measurement, content analysis of corporate reports is a well-established approach for quantifying disclosure extent (Unerman 2000; Pratama 2017; Miras-Rodríguez et al. 2018). Consistent with this tradition, the present study evaluates disclosure using a 12-item index covering: Environmental Data Assurance Standard; Environmental Data Independent Verification; Environmental Materials Sourcing; Environmental Supply Chain Management; Environmental Supply Chain Monitoring; Environmental Restoration Initiatives; Environmental Expenditures Investments; Environmental Investments Initiatives; Environmental Partnerships; Environmental Products; Environmental Assets Under Management; and Environmental Project Financing. The index records item presence (1) or absence (0) for each fiscal year, yielding a percentage score that enables firm-year comparisons of disclosure breadth.

The 12-item environmental disclosure index provides a structured way to assess how far companies integrate environmental responsibility into their strategies and operations. The first two items, environmental data assurance standards and independent verification, reflect the credibility and reliability of the information reported, showing that firms are willing to subject their data to external scrutiny (Li 2024). Items related to materials sourcing, supply chain management, and supply chain monitoring capture how companies extend environmental responsibility beyond their internal operations to the wider value chain, acknowledging that sustainability risks and impacts are interconnected (Mageto 2021).

Disclosure on restoration initiatives, environmental expenditures, and investment programs highlights the extent to which companies allocate resources to mitigate environmental impacts and develop long-term solutions (Alsayegh et al. 2020). These items demonstrate not only compliance but also commitment to proactive risk management and ecological improvement. Meanwhile, disclosure on partnerships and environmentally friendly products illustrates how firms collaborate with stakeholders and innovate in product offerings to align with sustainability goals (Donkor et al. 2024). Finally, information on environmental assets under management and project financing shows the financial dimension of sustainability, where companies channel funds into initiatives with positive environmental outcomes (Galeone et al. 2023).

2.4. Influence of Emission Score on Environmental Disclosure

The emission score is a rating of a company’s performance and transparency in managing emissions, calculated from publicly reported and verifiable data, thereby reflecting both actual actions to reduce emissions and the degree of openness in reporting (Arian and Sands 2024). A higher emission score therefore signals stronger emissions performance and greater transparency, which together constitute a positive signal to the market (Saka and Oshika 2014). This research adopts the emission score as a primary indicator because GHG emissions have become the most salient and urgent environmental issue globally—central to climate change—and thus a focal point for investors and policymakers; accordingly, emissions performance is an increasingly material component in ESG assessments.

Consistent with signaling theory, firms exhibiting superior performance tend to communicate credible positive signals to stakeholders through broader and more granular disclosure (Forcadell et al. 2022). Companies that effectively manage and reduce GHG emissions typically invest in technological innovation, operational efficiency, and regulatory compliance (Hetze 2016). Such investments credibly indicate proactive, forward-looking management capable of addressing environmental challenges. In turn, these firms are incentivized to employ extensive environmental disclosure as a strategic instrument to communicate superior performance to the market, strengthen reputation, and attract investors attentive to environmental and social dimensions (Boura et al. 2020).

Prior empirical evidence largely aligns with this view. Ifada and Saleh (2022) and Giannarakis et al. (2017) find that stronger environmental performance contributes to greater environmental disclosure. Divergent findings also exist: Aboagye-Otchere et al. (2019) report a significant but negative association in Ghana—consistent with a legitimacy-driven response—and Liu et al. (2023) argue that high carbon emitters tend to increase disclosure as a legitimization process. Despite such variation, we contend that the emission score—because it reflects both verified performance and transparency—functions as a particularly strong signal.

Accordingly, higher emission scores should be associated with stronger incentives to expand the breadth and depth of environmental disclosure, as a means to reinforce reputation, differentiate from peers, and demonstrate serious, ongoing commitments to sustainability to investors and other stakeholders (Thijssens et al. 2015). Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

Emission Score positively affects Environmental Disclosure.

2.5. Influence of Environmental Disclosure on Firm Value

Several studies suggest that environmental disclosure has not consistently exhibited a direct, significant effect on firm value—often attributed to voluntary or non-standardized disclosure practices—as well as mixed evidence in Noor and Ginting (2022). There are some arguments, however, that within the broader regional market context (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand) and amid rising ESG awareness, environmental disclosure plays a critical role. Firms that pair superior environmental performance with transparent disclosure can secure competitive advantages that translate into enhanced firm value (Yu et al. 2017).

Comprehensive disclosure serves as more than compliance; it is a strategic asset that bridges information gaps between firms and capital-market stakeholders. As investors increasingly consider ESG factors in decision-making, they tend to prefer firms that proactively manage environmental risk while demonstrating credible sustainability prospects (Tran and Beddewela 2020). From a stakeholder theory perspective, comprehensive environmental disclosure helps satisfy heterogeneous information demands, especially among increasingly selective investors. Transparency reduces investor risk, builds trust, and signals sound governance. From a legitimacy theory perspective, broad and transparent disclosure helps firms attain and maintain social and operational legitimacy, thereby mitigating reputational losses and attracting ESG-oriented capital (Istianingsih et al. 2020).

Under the resource-based view (RBV), the capability to manage and credibly disclose environmental information can meet VRIN criteria. Such capabilities foster a distinctive reputation among investors, broaden the investor base, including sustainable funds, and ultimately support the creation of higher economic value (Taylor et al. 2018). In other words, superior environmental disclosure is not merely compliance; it is an intangible asset that generates competitive advantage and contributes to higher firm value (Orlitzky et al. 2003).

Global evidence generally supports a positive association. Seminal work by Al-Tuwaijri et al. (2004) shows a significant positive relationship between environmental disclosure and market-based performance. Cahan et al. (2016) corroborate a positive ESG–value link, stronger in countries with robust investor protection. Gerged et al. (2020) find a significant positive association between corporate environmental disclosure and firm value in GCC countries. Similarly, Yang et al. (2020) document significant impacts of environmental information disclosure on the value of Chinese manufacturing firms, while Aboud and Diab (2018) report higher valuations for firms included in Egypt’s ESG index. A systematic review by Cai et al. (2024) concludes that ESG disclosure’s relationship with firm value is heterogeneous but operates through channels such as enhanced stakeholder trust. Giannarakis et al. (2017)—though focused on climate performance and disclosure—remain consistent with signaling theory, wherein higher disclosure intensity indicates superior corporate performance. Consequently, comprehensive environmental disclosure should act as a positive signal that improves market perceptions and thereby influences firm value. Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2.

Environmental Disclosure positively affects Firm Value.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives

Table 1 below presents the descriptive statistics of the variables employed in this study.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics.

The emission score (X1) has an average of 57.82 with a standard deviation of 26.23, ranging from 0.00 to 99.92. This distribution suggests considerable heterogeneity across firms, with some demonstrating strong performance in greenhouse gas management and disclosure, while others exhibit almost no engagement. Firm size (X2) shows a mean of 21.34 with values ranging from 17.17 to 27.05, indicating that the sample includes both relatively small and very large firms. Leverage (X3) has an average of 32.78, with a wide dispersion (standard deviation 19.81) and values spanning from 3.04 to 124.00. This indicates that while some firms maintain conservative capital structures, others rely heavily on debt financing. Profitability (X4), measured by return on assets, records a mean of 0.05 with a standard deviation of 0.07, ranging from −0.43 to 0.51. These values suggest that most firms operate with relatively low profitability, with some even experiencing negative returns. Firm age (X5) has an average of 1.94 with values between 0.08 and 18.96, reflecting the inclusion of both younger and more mature firms in the sample. Environmental disclosure (Y) shows a mean of 0.44, implying that on average firms disclosed around 44% of the environmental items considered. The variation (standard deviation 0.19) and the range between 0.08 and 0.92 highlight significant cross-firm differences in disclosure practices. Finally, firm value (Z), measured by the price-to-book ratio, has an average of 2.74 with a relatively high standard deviation of 5.84. The range between 0.14 and 55.58 suggests that while many firms exhibit moderate market valuations, a few are priced at substantial premiums, potentially due to strong financial fundamentals or robust ESG practices.

To provide a deeper understanding of environmental disclosure (Y), a descriptive analysis was conducted across countries and across the individual components of variable Y, as presented in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Environmental Disclosure per Country.

The descriptive analysis of environmental disclosure reveals notable variations both across countries and across disclosure components. Singaporean firms tend to disclose more comprehensively in areas such as environmental data assurance, independent verification, and product-related initiatives. This stronger performance may be attributed to Singapore’s relatively advanced regulatory environment and its position as a regional financial hub, where international investors exert significant pressure for transparency and standardized reporting (Mahmud et al. 2024). Similarly, firms in Thailand demonstrate higher levels of disclosure in materials sourcing and product categories, reflecting the country’s growing emphasis on sustainable production and export-oriented industries that are increasingly exposed to global supply chain requirements (Kuasirikun and Sherer 2004).

By contrast, Indonesian companies emphasize supply chain management, supply chain monitoring, and restoration initiatives. This pattern indicates that firms in Indonesia are highly responsive to operational sustainability practices and local environmental concerns, particularly given the country’s natural resource dependency and increasing scrutiny from domestic and international stakeholders (Husnaini and Basuki 2020). Nevertheless, Indonesian firms disclose less in areas related to environmental asset management, highlighting a gap in reporting on long-term financial aspects of environmental strategies. Malaysia shows comparatively weaker disclosure overall, especially in environmental expenditures and investment-related items. This may reflect differences in regulatory enforcement, the predominance of family-owned business structures, and relatively lower external pressure from capital markets compared to Singapore and Thailand (Joseph et al. 2023).

When examined across disclosure components, the results suggest that environmental supply chain management and supply chain monitoring are the most consistently reported items across all four countries. This finding underscores the regional priority placed on supply chain transparency, likely driven by both regulatory developments and the expectations of global business partners. Conversely, the least disclosed items are environmental assets under management and project financing, indicating that firms remain hesitant to provide detailed reporting on the financial commitments underlying their environmental initiatives.

Overall, these findings suggest that while companies in ASEAN capital markets have made progress in disclosing operational aspects of sustainability, substantial gaps remain in the disclosure of financial dimensions. The differences observed among countries reflect not only variations in institutional and regulatory pressures but also the degree of international integration of their capital markets. Firms operating in more globally connected markets, such as Singapore and Thailand, appear more responsive to international stakeholder expectations, while firms in Malaysia and Indonesia remain relatively less comprehensive in reporting on certain financial and investment-oriented aspects of environmental disclosure.

3.2. ANOVA

The results of the ANOVA test can be seen in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

ANOVA test results.

The ANOVA results indicate statistically significant differences across both countries and industries for emission scores (X1) and environmental disclosure (Y), with p-values below the 1% significance threshold. This demonstrates that variations in corporate environmental performance and reporting cannot be attributed to chance but are systematically associated with country- and sector-specific factors.

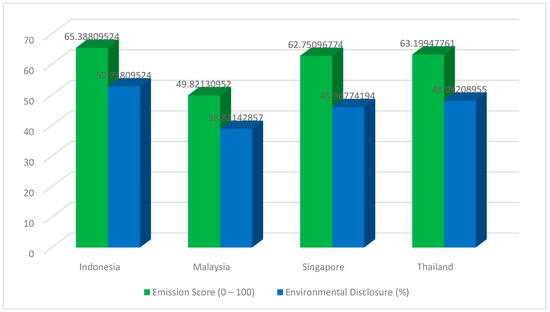

From a country perspective, Indonesian firms record the highest average emission score, suggesting relatively strong performance in managing and reporting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Singapore and Thailand follow closely with comparable averages, reflecting their integration into global markets and the associated pressures for improved climate-related performance. In contrast, Malaysian firms report the lowest emission score, underlining comparatively weaker emission management and disclosure practices. The pattern for environmental disclosure is similar: Indonesia again emerges as the strongest performer with the highest average disclosure score, while Malaysia lags behind, highlighting both cross-national differences in regulatory pressure and market expectations (Amran et al. 2017).

Sectoral results further emphasize the heterogeneity in sustainability practices. Health care firms achieve the highest average emission score, closely followed by energy companies, both of which also record the strongest levels of environmental disclosure. This pattern reflects the sensitivity of these industries to environmental and social scrutiny, particularly regarding carbon emissions in the energy sector and public trust in health-related industries (Broadstock et al. 2017). Financials also perform strongly, ranking among the top sectors in both emission scores and disclosure levels, which may reflect increasing regulatory and investor pressure on financial institutions to incorporate ESG risk management (Downar et al. 2021). At the opposite end of the spectrum, materials and information technology firms report the lowest emission scores, suggesting weaker progress in reducing or reporting carbon emissions. Real estate and information technology firms also record the lowest levels of environmental disclosure, consistent with prior findings that disclosure practices in these sectors are less standardized and subject to weaker external pressure (Córdova et al. 2018).

Overall, the results underscore two key insights. First, both country-level institutions and industry-specific dynamics play a decisive role in shaping firms’ environmental performance and reporting. Firms in countries with stronger international exposure (Indonesia, Singapore, and Thailand) and in sectors with higher ESG sensitivity (health care, energy, and financials) tend to achieve better outcomes. Second, the lowest performers—particularly Malaysian firms and those in materials, information technology, and real estate sectors—highlight persistent gaps in both emission management and environmental disclosure, pointing to areas where regulatory intervention and market pressure may need to be strengthened. To illustrate the cross-country variation, Figure 1 presents the average emission scores and environmental disclosure levels for firms in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand during 2022–2023. To further capture sectoral heterogeneity, Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of emission scores and environmental disclosure across industries, revealing that environmentally sensitive sectors such as energy, utilities, and materials demonstrate higher performance and disclosure levels compared to service-oriented industries.

Figure 1.

Average Emission Score and Environmental Disclosure by Country (2022–2023).

Figure 2.

Distribution of Emission Scores and Environmental Disclosures Across Industries.

3.3. SEM—Path Analysis

Before conducting the SEM analysis, the results of the model fit test are presented as shown in Table 4. The results of the model fit test indicate that all fit indicators show a good fit, which suggests that the established model can be further interpreted and can answer the research hypotheses being tested.

Table 4.

SEM Goodness of Fit test for Main Model.

The results of the SEM Path analysis are presented in Table 5 below.

Table 5.

SEM Path Results for Main Model.

The model explaining environmental disclosure achieves an R2 of 0.55, indicating that emission score, firm size, and firm age explain 55% of the variance in disclosure, while the residual variance remains at 0.45. The model for firm value records an R2 of 0.20, showing that environmental disclosure, firm size, firm age, profitability, and leverage explain 20% of the variance, with a residual variance of 0.80.

The path coefficients show that emission score exerts a strong and significant positive effect on environmental disclosure with a coefficient of 0.42 and t-value of 10.73. Firm size also contributes significantly and positively with a coefficient of 0.40 and t-value of 9.92, while firm age has a smaller but significant effect with a coefficient of 0.10 and t-value of 2.64. In the model for firm value, the direct path from environmental disclosure is positive but not significant with a coefficient of 0.08 and t-value of 0.83. Profitability with a coefficient of 0.33 and t-value of 3.27 and leverage with a coefficient of 0.34 and t-value of 3.96 both show significant positive effects, while firm size demonstrates a significant negative effect with a coefficient of −0.34 and t-value of −2.89. Emission score shows a marginal effect with a coefficient of 0.10 and t-value of 1.96, and firm age is not significant.

The first hypothesis, which states that emission score positively affects environmental disclosure, is supported. The results confirm that firms with higher emissions performance and transparency are more likely to provide broader and more detailed disclosure, consistent with signaling theory and the resource-based view. The second hypothesis, which states that environmental disclosure positively affects firm value, is not supported. Although the coefficient is positive, it is not statistically significant, indicating that disclosure does not yet translate directly into enhanced market valuation in the sample. This finding suggests that while disclosure practices are expanding, capital markets in the region may not fully integrate such information into valuation decisions, with profitability and leverage remaining stronger determinants of firm value.

3.4. Robustness Test

Before estimating the regression models, several diagnostic tests were performed to ensure that the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) assumptions were met. Table 6 presents the results of the classical assumption tests. These diagnostics assess whether the regression residuals and explanatory variables satisfy the fundamental statistical requirements for reliable estimation.

Table 6.

Classical Assumption Test for Equation (3), (4) and (5) Results.

The results show that Equation (3) satisfies all classical assumptions. This suggests that the regression residuals are normally distributed and homoscedastic, and that no serious multicollinearity exists among predictors, making the OLS estimates efficient and unbiased. In contrast, Equations (4) and (5) exhibit deviations from normality and heteroscedasticity (p < 0.05), though they pass the VIF and autocorrelation tests. This indicates that while the parameter estimates remain consistent, their standard errors may be less reliable, implying potential efficiency loss in these models. To mitigate such issues, robust standard errors are applied in subsequent estimations to ensure that statistical inferences remain valid even under mild violations of the homoscedasticity or normality assumptions.

Before estimating the regression models, panel data specification tests were conducted to determine the most appropriate estimation approach for Equations (3)–(5). The results, presented in Table 7, show that the Chow test yields a p-value of 0.0000 across all equations, indicating that the pooled OLS model is not suitable and that panel data estimation is preferred. Subsequently, the Hausman test results produce p-values greater than 0.05 for Equation (3) (0.2228), and marginally above the 0.05 threshold for Equations (4) and (5). These outcomes suggest that the random effects model is the most appropriate estimator for all three equations, as the null hypothesis of no systematic difference between fixed and random estimators cannot be rejected. Accordingly, all regression models in this study—covering the relationships between emission performance, environmental disclosure, and firm value—were estimated using the Random Effects Generalized Least Squares (EGLS) method.

Table 7.

Panel Data Regression Method Selection.

To ensure the consistency and reliability of the main model’s findings, a series of robustness tests were performed using panel regression analysis as shown in Table 8. The robustness models (Equations (3)–(5)) replicate the causal structure of the SEM analysis, with Equation (3) testing the relationship between emission score and environmental disclosure, and Equations (4) and (5) examining the effect of environmental disclosure on firm value, including market performance controls in the final model.

Table 8.

OLS Regression Results.

The results of the robustness estimations are broadly consistent with the main SEM model. In both approaches, emission score (X1) exhibits a significant and positive association with environmental disclosure (Y) (SEM path coefficient 0.42, t = 10.73; regression coefficient 0.0031, p = 0.0229), confirming that firms with stronger emission management performance tend to disclose more comprehensively. This supports the robustness of H1 under both analytical frameworks.

Meanwhile, the effect of environmental disclosure (Y) on firm value (Z) remains positive but statistically insignificant across all models (SEM: t = 0.83; regressions: p = 0.0587–0.0609), indicating that disclosure does not yet have a measurable direct impact on firm valuation. The direction and magnitude of the coefficients remain consistent between the SEM and regression results, reinforcing the conclusion that while disclosure contributes to transparency, it has not been fully priced by the market in the short term.

The inclusion of market controls, market return (M1) and trading volume (M2)—slightly improves model stability but does not materially alter the results. Both variables are statistically insignificant, suggesting that firm-specific fundamentals remain the primary drivers of firm value rather than external market fluctuations.

The second robustness analysis was conducted to verify whether the structural relationships observed in the main SEM model remain stable when the sample is divided based on industry environmental sensitivity. Table 9 below presents the results of the SEM goodness-of-fit tests for environmentally sensitive and non-sensitive industries. Both models show consistent goodness-of-fit outcomes across most incremental and parsimony indices, including GFI, NFI, CFI, IFI, PGFI, PNFI, AIC, and CAIC—all of which meet acceptable fit thresholds. This indicates that, despite differences in environmental exposure, the models demonstrate satisfactory overall stability and comparability.

Table 9.

SEM Goodness of Fit test for Robustness Check.

However, several absolute fit indices (Chi-square and RMSEA) indicate weaker model fit in both subsamples, suggesting a potential influence of smaller subsample sizes and increased model complexity when sectoral segmentation is applied. Similarly, AGFI and Critical N values remain below ideal thresholds, implying that the environmental and disclosure structures in each sector may vary in scale or maturity. Nevertheless, the consistency of the key incremental and parsimony indicators relative to the main model—where all indices achieved a strong fit—supports the robustness of the primary results.

Following the assessment of model fit, the second robustness analysis was conducted to examine whether the relationships among emission performance, environmental disclosure, and firm value remain stable across industries with differing levels of environmental exposure.

The results, presented in Table 10, show that the direction and significance patterns of the key paths are consistent with the main model, confirming the overall stability of the relationships. In both groups, emission score (X1) continues to have a strong and positive effect on environmental disclosure (Y), reinforcing the validity of H1 and indicating that better emission management consistently drives broader disclosure, regardless of industry type. The explanatory power of the disclosure model (R2 = 0.53 and 0.57, respectively) remains comparable to the main model (R2 = 0.55), further supporting the robustness of this relationship.

Table 10.

SEM Path Results for Robustness Check.

Conversely, the path from environmental disclosure to firm value remains statistically insignificant across both groups, mirroring the main SEM results where this relationship was also non-significant. This suggests that environmental disclosure, although informative, has not yet been fully integrated into market valuation processes across sectors in Southeast Asia.

Notably, the coefficients of firm-specific controls (size, profitability, and leverage) remain directionally consistent with the main model, though their magnitude varies slightly—particularly for leverage (negative in sensitive industries, weakly positive in non-sensitive ones), reflecting sectoral differences in capital structure effects on valuation.

Taken together with the goodness-of-fit outcomes, these results indicate that while model fit weakens somewhat under subsample estimation (likely due to smaller sample sizes), the key structural relationships remain directionally and statistically robust. This consistency reinforces confidence in the validity of the main findings, showing that the positive link between emission performance and disclosure is stable across contexts, while the effect of disclosure on firm value remains limited regardless of environmental exposure.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study provide several important insights into the relationship between emission performance, environmental disclosure, and firm value in the Southeast Asian context. First, the results confirm that emission score has a significant and positive effect on environmental disclosure. This suggests that firms with stronger performance in managing greenhouse gas emissions are more likely to engage in broader and more transparent reporting practices (Gnanaweera and Kunori 2018). Such evidence aligns with signaling theory, as well-performing firms use disclosure as a strategic communication tool to differentiate themselves from weaker performers (Shao and He 2022). It also reinforces the resource-based view, highlighting that superior emissions management represents a distinctive capability that encourages firms to disclose more comprehensively in order to consolidate reputational and strategic benefits (Truant et al. 2017).

By contrast, the study does not find support for the direct effect of environmental disclosure on firm value. While the coefficient is positive, it is not statistically significant, suggesting that current disclosure practices in the region may not yet be sufficiently standardized, credible, or valued by investors to translate into measurable market premiums (Wasara and Ganda 2019). This finding resonates with prior studies in emerging markets, where voluntary and heterogeneous disclosure often limits its informational relevance (Pratama 2022). From a stakeholder and legitimacy theory perspective, firms may engage in disclosure primarily to satisfy external expectations and maintain legitimacy, but the capital market may not fully reward these practices (Jain et al. 2016). This highlights a disclosure–value gap, where the act of reporting itself is not yet a decisive driver of valuation, unlike financial fundamentals such as profitability and leverage, which remain dominant factors in explaining firm value (Ozata Canli and Sercemeli 2025).

The robustness analyses substantiate the reliability of these findings. The panel regression robustness check, employing random-effects models with market performance controls, produces results consistent with the primary SEM model. Emission performance continues to exhibit a positive and significant association with environmental disclosure, affirming the stability of H1, while the path from disclosure to firm value remains positive but statistically insignificant. The inclusion of market return and trading volume controls enhances model stability without altering the direction or significance of the relationships, indicating that structural relationships are driven by firm-level sustainability behavior. The multi-group SEM robustness test, which segregates firms into environmentally sensitive and non-sensitive industries, provides additional support. In both subsamples, the association between emission performance and environmental disclosure remains positive and significant, whereas the disclosure–value path remains weak and insignificant. These results demonstrate that the relationship between emission performance and disclosure is structurally stable, irrespective of sectoral environmental exposure. However, leverage effects differ between groups—negative among environmentally sensitive industries and weakly positive among non-sensitive ones—suggesting that capital structure decisions may interact with environmental risk exposure in firm valuation. These findings confirm that key relationships are robust across econometric methods and industry subsamples, thereby strengthening the study’s empirical validity.

Cross-country analysis provides further nuance. Firms in Indonesia, Singapore, and Thailand generally exhibit stronger emission performance and disclosure compared to Malaysia. These differences can be attributed to variations in regulatory frameworks and institutional pressures. Singapore’s mandatory sustainability reporting requirements and Thailand’s integration into global supply chains have likely contributed to higher disclosure practices, while in Malaysia, where disclosure remains more voluntary, firms demonstrate relatively weaker performance (Siregar et al. 2024). Sectoral differences also emerge: health care, energy, and financial firms score higher in both emissions management and disclosure, reflecting the heightened scrutiny and institutional expectations in these industries. In contrast, materials, IT, and real estate firms tend to lag behind, likely due to weaker regulatory oversight or less investor demand for disclosure in these sectors (Setiarini et al. 2023).

The results also have theoretical implications. The support for first hypothesis underscores the explanatory power of signaling theory and the resource-based view in the environmental disclosure context. Firms with superior emissions performance are not only motivated but also capable of signaling credibility through enhanced transparency. However, the lack of support for second hypothesis suggests that stakeholder and legitimacy theories remain relevant in Southeast Asia, where disclosure may still be driven by social and regulatory pressures rather than direct capital market rewards. This underscores the transitional stage of ESG integration in emerging markets, where disclosure practices are expanding but their value relevance is still limited.

From a practical perspective, the findings carry implications for regulators, investors, and firms. Regulators in ASEAN countries need to strengthen ESG reporting frameworks to ensure comparability, consistency, and credibility of disclosure. Investors should prioritize verified performance metrics, such as emission scores, which currently serve as more reliable indicators of corporate sustainability than disclosure alone (Ibishova et al. 2024). For firms, the results highlight the strategic importance of integrating robust emissions management with transparent disclosure to position themselves for long-term value creation, even if immediate capital market recognition is not yet apparent (Jayarathna et al. 2021). Over time, as global standards such as IFRS S1 and S2 are implemented, it is expected that the value relevance of environmental disclosure will increase, bridging the current gap between reporting and firm valuation. Their implementation will enhance the consistency, comparability, and credibility of ESG information, enabling investors to better assess how firms manage transition and physical climate risks. In ASEAN, where disclosure practices remain fragmented, the convergence toward ISSB-based standards may narrow the current gap between sustainability reporting and market valuation by embedding climate-risk transparency into the broader assessment of firm performance and value creation (Kusuma and Gani 2024).

5. Methods

This study adopts a quantitative approach to examine the causal relationships between emission score, environmental disclosure, and firm value in Southeast Asia. A quantitative method is considered appropriate because it enables the testing of objective theories by measuring relationships among variables with numerical data and applying statistical techniques (Creswell and Creswell 2018). Specifically, the research follows a causal design to assess how one variable influence another, consistent with Neuman’s (2014) assertion that causal research aims to demonstrate whether independent variables truly affect dependent variables. The focus of the analysis is twofold: first, to examine the effect of emission score on environmental disclosure, and second, to assess the impact of environmental disclosure on firm value.

The study’s population encompasses all firms listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX), Bursa Malaysia, Singapore Exchange (SGX), and the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) during the 2022–2023 period. The selection of these countries enables a cross-country comparison within ASEAN, where regulatory frameworks, investor awareness, and levels of ESG adoption exhibit significant variation. Purposive sampling was employed to ensure the inclusion of only those firms with complete data for all variables. Initially, the population comprised 3019 listed firms. Following the exclusion of firms with missing price-to-book value (PBV) data, incomplete environmental disclosure scores (based on 12 indicators), or unavailable financial and emission score information, the final sample consists of 406 firm-year observations, representing 203 listed firms from four ASEAN countries over the 2022–2023 period. Specifically, the sample includes 42 observations from Indonesia, 168 from Malaysia, 62 from Singapore, and 134 from Thailand.

The period 2022–2023 was deliberately chosen for three reasons. First, it coincides with a sharp increase in the adoption of sustainability reporting standards in the Asia-Pacific region, where firms were increasingly expected to provide more transparent ESG data. Second, it captures the crucial transition surrounding the release of IFRS S1 and S2 by the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) in mid-2023, which marked a turning point for global sustainability disclosure practices. By covering both 2022 and 2023, the study observes reporting practices before and after these international developments. Third, at the time of research, complete company-level data for 2024 were not yet available, as many firms had not released their annual reports. Therefore, 2022–2023 represents the most recent period with comprehensive and reliable data across all required variables.

The variables and their operational definitions are presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

Variable Operationalization.

Control variables were included to isolate the effects of the main variables. Firm size is controlled because larger firms often possess greater resources and face stronger stakeholder pressure to disclose environmental information (Adeniyi Olubunmi et al. 2025). Firm age is controlled as older firms may have more mature disclosure practices, whereas younger firms may demonstrate greater responsiveness and innovation (Ding et al. 2022). Profitability is controlled because more profitable firms are generally associated with higher firm value (Nguyen et al. 2022). Finally, leverage is controlled as high levels of debt increase financial risk and may negatively affect firm valuation (Ammer et al. 2020).

The study relies entirely on secondary data collected from LSEG Data & Analytics, a comprehensive and globally recognized provider of financial and ESG data. Information was sourced from annual and sustainability reports, company websites, CSR reports, regulatory filings, stock exchange disclosures, and third-party organizations including media and NGOs. The LSEG methodology ensures that the data are standardized, verified, and consistently updated, making it suitable for empirical research on ESG practices.

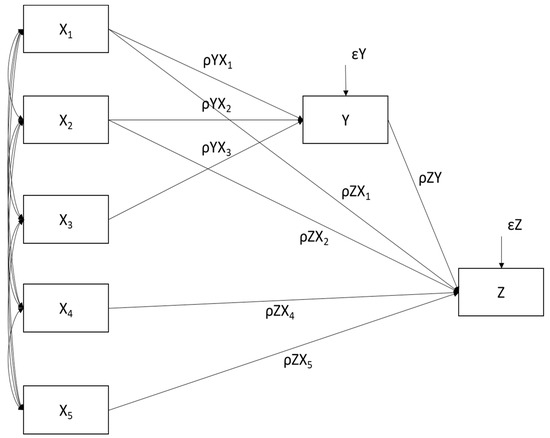

For data analysis, the study employs path analysis within the framework of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Path analysis is appropriate because all variables are directly observed rather than latent constructs. SEM is particularly advantageous as it enables the simultaneous estimation of multiple causal relationships and provides diagnostic tests for model fit. Model estimation is conducted using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), with model fit assessed using absolute, incremental, and parsimony fit indices. Hypotheses are tested using one-tailed significance tests at the 5% level, where coefficients are expected to be positive in accordance with the hypothesized relationships. In addition, complementary statistical tests are conducted to provide deeper insights into the data. Descriptive statistics are used to summarize the distribution of all variables across firms, while one-way ANOVA is applied to test whether significant differences exist in emission scores (X1) and environmental disclosure (Y) across countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand) and across industries classified under the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS). This approach not only evaluates the hypothesized causal relationships but also provides evidence on cross-country and cross-industry variation in climate risk management and disclosure practices within ASEAN. Below is the proposed path diagram (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Path Diagram.

The path equations are presented as follows:

where

: Path Coefficient from to Y

: Path Coefficient from to Y

: Path Coefficient from to Y

: Path Coefficient from to Z

: Path Coefficient from to Z

: Path Coefficient from to Z

: Path Coefficient from to Z

: Path Coefficient from Y to Z

: Error term Y

: Error term Z

To enhance the reliability of the empirical findings, two additional robustness checks are conducted. First, we control for country-level market conditions that may affect firm value beyond firm-specific characteristics. Because firm value, measured by PBV is inherently sensitive to overall stock market performance and trading activity, we re-estimate the structural relations using ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions in two stages. In the first stage, we estimate the baseline firm-level model:

In the second stage, we augment the firm-value equation with market control variables capturing country-year stock index returns and average trading activity.

where

= Environmental Disclosure

= Firm Value

= Emission Score

= Firm Size

= Firm Age

= Profitability

= Leverage

= Country Stock Index Return (market performance)

= Average Trading Volume (market liquidity)

= Intercept terms

= Estimated coefficients for firm-level variables

= Coefficients for market-level controls

= Error terms representing unexplained variance

Market return and average trading volume are incorporated as market-level control variables to account for external market conditions that may influence firm value beyond firm-specific characteristics. Market return reflects the overall performance and sentiment of the national equity market, which can affect investors’ valuation of firms regardless of their internal performance. Average trading volume, on the other hand, captures market liquidity, indicating how easily shares are traded; more liquid markets generally support higher firm valuations due to lower transaction costs and stronger investor confidence. Following prior studies in capital market research, market return is measured as the annual percentage change in the main stock index of each country (IDX Composite for Indonesia, FTSE Bursa Malaysia KLCI, Straits Times Index for Singapore, and SET Index for Thailand), while average trading volume is calculated as the geometric mean of monthly trading volume during the fiscal year. Comparing the baseline and extended models allows us to assess whether the main relationships among X1, Y and Z remain stable after accounting for market-wide movements in valuation.

Second, we examine whether the results are influenced by industry composition, particularly differences in environmental exposure across sectors. Firms are classified into two groups based on their environmental sensitivity following the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS). The environmentally sensitive industries include Energy, Materials, Industrials, Utilities, and Real Estate, while the non-sensitive industries comprise Financials, Information Technology, Health Care, Consumer Discretionary, Consumer Staples, and Communication Services. We then re-estimate the original SEM model separately for each group to assess whether the structural relationships differ across sectors with distinct levels of exposure to climate and environmental risks. This multi-group analysis allows for testing whether emission performance and environmental disclosure are more relevant for firms operating in high-emission sectors, while ensuring that the main conclusions are not driven by heterogeneity in industry characteristics or environmental materiality.

6. Conclusions

This study provides new evidence on the nexus between emission performance, environmental disclosure, and firm value in the Southeast Asian context. The findings show that firms with higher emission scores tend to disclose more environmental information, underscoring the role of signaling and resource-based perspectives in explaining disclosure practices. By contrast, environmental disclosure itself does not exert a significant influence on firm value, suggesting that current reporting in the region is still fragmented and not yet fully appreciated by capital markets. Cross-country and sectoral variations further reveal the importance of institutional pressures, regulatory environments, and industry-specific scrutiny in shaping both emission management and disclosure behavior. These results highlight a disclosure–value gap, where the act of reporting alone is insufficient to generate market premiums, while fundamentals such as profitability and leverage remain dominant drivers of valuation.

Despite these contributions, the study has several limitations. The analysis covers only a two-year period (2022–2023), which may not capture the long-term trajectory of ESG integration in the region. The sample is limited to four Southeast Asian countries—Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand—thus caution should be exercised in generalizing the results to other contexts. Moreover, the reliance on Refinitiv LSEG data provides consistency and comparability, but it may not fully reflect the qualitative richness or credibility of company reports. Methodologically, the path analysis approach emphasizes direct causal links and does not incorporate moderating or mediating factors, such as governance mechanisms or investor protection regimes, which could further explain the disclosure–value relationship.

These limitations open avenues for future research. Longer observation periods are needed to assess whether the disclosure–value gap narrows as global standards such as IFRS S1 and S2 become entrenched. Expanding the scope to include other ASEAN and emerging-market economies could also shed light on institutional diversity and its influence on disclosure effectiveness. Finally, combining quantitative approaches with qualitative assessments of disclosure credibility, or extending the model to include governance, cultural, and investor-related variables, would enrich understanding of how sustainability practices are internalized by firms and valued by markets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P. and A.R.M.; methodology, A.P.; software, A.P.; validation, A.P. and A.R.M.; formal analysis, A.P.; investigation, A.P.; resources, A.P.; data curation, A.P. and A.R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.M.; writing—review and editing, A.P. and A.R.M.; visualization, A.P. and A.R.M.; supervision, A.P.; project administration, A.P. and A.R.M.; funding acquisition, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia. Funding Number: SK 1715 Year 2025.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to proprietary restrictions from Refinitiv LSEG Data & Analytics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdul Rahman, Roszaini, and Mohammad Faisal Alsayegh. 2021. Determinants of Corporate Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) Reporting among Asian Firms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboagye-Otchere, Francis Kwasi, Samuel Nii Simpson, and Joseph Ato Kusi. 2019. The influence of environmental performance on environmental disclosures: An empirical study in Ghana. Business Strategy & Development 3: 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Aboud, Ahmed, and Ayman Diab. 2018. The impact of social, environmental and corporate governance disclosures on firm value: Evidence from Egypt. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 8: 442–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi Olubunmi, Felicia, Oladipo Sunday, and Gbenga Adeniran Busari. 2025. Does Sustainability Reporting Influence Firm Value of Emerging Economies? International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology 10: 2425–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhariani, Desi, and Charl de Villiers. 2019. Integrated reporting: Perspectives of corporate report preparers and other stakeholders. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 10: 126–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhariani, Desi, and Estelle du Toit. 2020. Readability of sustainability reports: Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 10: 621–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayegh, Mohammad Faisal, Samaneh Homayoun, and Roszaini Abdul Rahman. 2020. Corporate Economic, Environmental, and Social Sustainability Performance Transformation through ESG Disclosure. Sustainability 12: 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tuwaijri, Saud A., Theodore E. Christensen, and K. E. Hughes, II. 2004. The relations among environmental disclosure, environmental performance, and economic performance: A simultaneous equations approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society 29: 447–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidjaya, Prima Gusti, and Antonius Kurniawan Widagdo. 2020. Sustainability reporting in Indonesian listed banks: Do corporate governance, ownership structure and digital banking matter? Journal of Applied Accounting Research 21: 231–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammer, Mohammed A., Mohammed A. Alyahya, and Majed M. Aliedan. 2020. Do Corporate Environmental Sustainability Practices Influence Firm Value? The Role of Independent Directors: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 12: 9768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, Azlan, Dato’ Mohd Amir Naim, Mohd Mohid Zain, Faizah Darus, Mehdi Nejati, Yuli Purwanto, Haslinda Yusoff, and Hasan Fauzi. 2017. Social responsibility disclosure in Islamic banks: A comparative study of Indonesia and Malaysia. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 15: 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arian, Ali Gheisari, and John Sands. 2024. Do corporate carbon emissions affect risk and capital costs? International Review of Economics & Finance 93: 1363–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Muhammad, Hasan Al-Bataineh, and Christopher Gan. 2023. Global evidence on the association between environmental, social, and governance disclosures and future earnings risk. Business Strategy and the Environment 33: 2497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerswald, Heike, Marcel Thum, and Kai A. Konrad. 2017. Adaptation, mitigation and risk-taking in climate policy. Journal of Economics 124: 269–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Sung Min, Jong Dae Kim, and Md Abdus Salam Masud. 2018. A Cross-Country Investigation of Corporate Governance and Corporate Sustainability Disclosure: A Signaling Theory Perspective. Sustainability 10: 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Sjoukje, Duncan Liefferink, Martine van Maarseveen, Nguyen Thi Tuan, Gerda Gunthawong, Kristine Dematera Contreras, Monica Kappiantari, Mark Zuidgeest, and Manuel Guillen. 2017. Low-Carbon Transport Policy in Four ASEAN Countries: Developments in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. Sustainability 9: 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirne, John, Nuobu Renzhi, and Ulrich Volz. 2021. Bracing for the Typhoon: Climate change and sovereign risk in Southeast Asia. Sustainable Development 29: 537–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boura, Maria, Spyridon Lioukas, and Dimitris A. Tsouknidis. 2020. The Role of pro--Social Orientation and National Context in Corporate Environmental Disclosure. European Management Review 17: 1027–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, David C., Alan Collins, Lester C. Hunt, and Konstantinos Vergos. 2017. Voluntary disclosure, greenhouse gas emissions and business performance: Assessing the first decade of reporting. The British Accounting Review 50: 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadez, Simon, Achim Czerny, and Peter Letmathe. 2018. Stakeholder pressures and corporate climate change mitigation strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment 28: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahan, Steven F., Charl de Villiers, David C. Jeter, Vic Naiker, and Chris J. van Staden. 2016. Are CSR Disclosures Value Relevant? Cross-Country Evidence. European Accounting Review 25: 579–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Chen, Samer A. Hazaea, Mohammed Hael, Emad M. Al-Matari, Abdullah Alhebri, and Ahmad M. Alfadhli. 2024. Mapping the Landscape of the Literature on Environmental, Social, Governance Disclosure and Firm Value: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review. Sustainability 16: 4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Archie B., and Kareem M. Shabana. 2010. The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice. International Journal of Management Reviews 12: 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Charles H., and Dennis M. Patten. 2007. The role of environmental disclosures as tools of legitimacy: A research note. Accounting, Organizations and Society 32: 639–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, Peter M., Yue Li, Gordon D. Richardson, and Florin P. Vasvari. 2008. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society 33: 303–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova, Carlos, Pedro Merello, and Ana Zorio-Grima. 2018. Carbon Emissions by South American Companies: Driving Factors for Reporting Decisions and Emissions Reduction. Sustainability 10: 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W., and J. David Creswell. 2018. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan, Craig. 2002. Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures—A theoretical foundation. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 15: 282–311. [Google Scholar]

- Del Gesso, Cristina, and Rab Nawaz Lodhi. 2024. Theories underlying environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure: A systematic review of accounting studies. Journal of Accounting Literature 47: 433–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derouez, Fouad, and Atef Ifa. 2025. Assessing the Sustainability of Southeast Asia’s Energy Transition: A Comparative Analysis. Energies 18: 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Xi, Yuxin Yang, Olga Efimova, Anna Steblyanskaya, Liang Ye, and Jing Zhang. 2022. The Impact Mechanism of Environmental Information Disclosure on Corporate Sustainability Performance—Micro-Evidence from China. Sustainability 14: 12366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, Dammika, Suren Kuruppu, Wei Qian, and Carol Tilt. 2021. Barriers for sustainability reporting: Evidence from Indo-Pacific region. Meditari Accountancy Research 29: 264–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkor, Anthony, Tita Trireksani, and Handan G. Djajadikerta. 2024. Incremental value relevancies in the development of reporting of sustainability performance. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance 35: 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downar, Benjamin, Stefan Schwenen, Jens Ernstberger, André Zaklan, and Stefan Reichelstein. 2021. The impact of carbon disclosure mandates on emissions and financial operating performance. Review of Accounting Studies 26: 1137–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Shuili, Chitrabhan B. Bhattacharya, and Sankar Sen. 2010. Maximizing Business Returns to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of CSR Communication. International Journal of Management Reviews 12: 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, Robert G., and George Serafeim. 2013. The Performance Frontier: Innovating for a Sustainable Strategy. Harvard Business Review 91: 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, Robert G., Ioannis Ioannou, and George Serafeim. 2014. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Management Science 60: 2835–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcadell, Francisco Javier, Elena Aracil, and Ana Lorena. 2022. The firm under the spotlight: How stakeholder scrutiny shapes corporate social responsibility and its influence on performance. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 30: 1258–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Andrew L., and Samantha Miles. 2006. Stakeholders: Theory and Practice. Oxford: OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Galeone, Giuseppe, Giuseppe Dicuonzo, Maria Shini, and Sergio Ranaldo. 2023. Sustainability Reporting: Evidence from Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs). Journal of Financial Management, Markets and Institutions 11: 2350011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerged, Ali Mohammed, Ehesan Beddewela, and Christopher J. Cowton. 2020. Is corporate environmental disclosure associated with firm value? A multicountry study of Gulf Cooperation Council firms. Business Strategy and the Environment 30: 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarakis, Grigoris, Eleni Zafeiriou, and Nikos Sariannidis. 2017. The Impact of Carbon Performance on Climate Change Disclosure. Business Strategy and the Environment 26: 1078–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanaweera, K. A. Keshan, and Naoki Kunori. 2018. Corporate sustainability reporting: Linkage of corporate disclosure information and performance indicators. Cogent Business & Management 5: 1423872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, Shakir, Foo Wei Lai, Muhammad Kashif Shad, Sidra Farooq Khatib, and Shahid Ehsan Ali. 2023. Assessing the implementation of sustainable development goals: Does integrated reporting matter? Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 14: 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, Kharina, Putra Anugrah, Farid Goembira, Indra Overland, Beni Suryadi, and Ahmad Swandaru. 2022. Moving beyond the NDCs: ASEAN pathways to a net-zero emissions power sector in 2050. Applied Energy 311: 118580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetze, Katharina. 2016. Effects on the (CSR) Reputation: CSR Reporting Discussed in the Light of Signalling and Stakeholder Perception Theories. Corporate Reputation Review 19: 281–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homroy, Swarnodeep. 2022. GHG emissions and firm performance: The role of CEO gender socialization. Journal of Banking & Finance 148: 106721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Zhiqi, Shuo Zhang, and Yi Huang. 2024. The Possibility and Improvement Directions of Achieving the Paris Agreement Goals from the Perspective of Climate Policy. Sustainability 16: 4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husnaini, Wiwi, and Bambang Basuki. 2020. ASEAN Corporate Governance Scorecard: Sustainability Reporting and Firm Value. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 7: 315–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibishova, Bektur, Bent Misund, and Roar Tveterås. 2024. Driving green: Financial benefits of carbon emission reduction in companies. International Review of Financial Analysis 96: 103757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifada, Laily Maisa, and Nur Masykur Saleh. 2022. Environmental performance and environmental disclosure relationship: The moderating effects of environmental cost disclosure in emerging Asian countries. Management of Environmental Quality 33: 1553–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]