1. Introduction

The global push toward sustainability has intensified the focus on Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) and sustainable finance as key mechanisms for reducing environmental impact while maintaining economic viability. Green supply chains integrate environmental criteria into traditional supply chain operations, promoting resource efficiency, waste reduction, and circular economy practices (

Hariyani et al. 2024;

Khan and Abonyi 2022;

Shetty and Bhat 2022). Concurrently, sustainable finance has emerged as a critical enabler of GSCM, with financial instruments such as green loans and sustainability-linked credits incentivizing enterprises to adopt environmentally friendly practices (

Liao et al. 2025;

Marcinkowska et al. 2025;

Ruan et al. 2025).

However, effectively aligning financial incentives with sustainability goals remains a significant challenge. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) metrics have emerged as prominent tools for evaluating corporate sustainability (

Li and Gu 2025;

Sun and Shang 2025;

Xin et al. 2025). Evidence indicates that firms with robust ESG performance gain better access to green credit, benefit from lower capital costs, and achieve improved financial outcomes (

Li and Gu 2025;

Zhang et al. 2024). From a risk management perspective, strong ESG credentials are increasingly viewed as a proxy for lower long-term risk and greater operational resilience, potentially mitigating risks related to environmental liabilities, social unrest, or governance scandals. However, current applications of ESG in financial decision-making often rely on static, retrospective evaluations, limiting their ability to dynamically influence behavior and promote real-time improvements in sustainability practices (

Liu 2025;

Song et al. 2025;

Zhang et al. 2024). This static approach fails to capture the evolving nature of risk within complex supply chains and misses the opportunity to use financial leverage proactively to reduce systemic environmental and credit risks.

Moreover, while existing research has demonstrated the positive correlation between ESG performance and financial benefits, few studies explore how dynamic, real-time integration of ESG metrics into credit allocation processes can drive sustainable outcomes across supply chains while simultaneously monitoring the implications for the lender’s portfolio risk. This gap is particularly relevant for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which often face resource constraints in adopting green technologies despite their critical role in supply networks, and are typically perceived as higher-risk borrowers (

Gera et al. 2022;

Islam et al. 2024;

Wang et al. 2025b).

Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) offers a promising approach to address this research gap. ABM enables the simulation of complex interactions among heterogeneous agents—such as manufacturers, financial institutions, and regulators—while capturing emergent behaviors and non-linear system dynamics (

Castillo Grisales et al. 2024;

Fiedler 2022;

Pan et al. 2024). It is particularly suited for stress-testing financial mechanisms under various scenarios and understanding the emergent risk profiles at a system level. Although ABM has been applied to study sustainable supply chains (

Li et al. 2024;

Pan et al. 2024;

Zhang and Han 2024), its use in modeling dynamics, ESG-driven credit mechanisms and their associated risk trade-offs remains underexplored.

Therefore, this study aims to bridge this gap by developing an agent-based model to simulate a dynamic credit allocation mechanism that explicitly incorporates ESG performance to manage the dual objectives of environmental improvement and credit risk mitigation. Our research seeks to answer the following questions:

(1) How does dynamic, ESG-based credit allocation influence the adoption of green technologies among SMEs, and what are the consequent effects on the financial institution’s credit risk exposure?

(2) What is the relationship between the weighting of ESG metrics in credit decisions and environmental outcomes such as carbon footprint reduction?

(3) How can financial institutions and policymakers design more effective risk-aware incentives for supply chain decarbonization?

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews relevant literature on GSCM, ESG metrics, and agent-based modeling.

Section 3 details the methodology and design of the agent-based model.

Section 4 presents the simulation results and sensitivity analysis.

Section 5 discusses theoretical and practical implications, and

Section 6 concludes with limitations and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

This chapter synthesizes the existing body of knowledge central to this research, structured around three interconnected themes: the foundational concepts of Green Supply Chain Management and sustainable finance, the critical role of ESG metrics within this financial landscape, and the application of Agent-Based Modeling as a tool for investigating such complex systems. The review culminates in identifying the specific research gap this thesis aims to address.

2.1. Green Supply Chain Management and Sustainable Finance

Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) has established itself as a fundamental strategy for organizations seeking to reconcile operational efficiency with environmental and social responsibility (

Gera et al. 2022;

Hariyani et al. 2024;

Shetty and Bhat 2022). It encompasses a wide spectrum of activities, from sustainable sourcing and distribution (

Hariyani et al. 2024) to the implementation of circular economy principles (

Khan and Abonyi 2022). The adoption of GSCM practices is consistently linked to enhanced environmental and organizational performance, although its penetration varies across industries and is often most prominent in large manufacturing firms (

Gera et al. 2022;

Islam et al. 2024).

In parallel, the field of sustainable finance has emerged as a powerful enabler of GSCM objectives. The concept of a Sustainable Supply Chain Finance (SSCF) ecosystem extends traditional financial instruments by integrating sustainability criteria, aiming to optimize working capital while simultaneously generating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) benefits (

Liao et al. 2025). Empirical evidence confirms that participation in SSCF can significantly improve a firm’s ESG performance by alleviating financial constraints and enhancing operational transparency (

Wang et al. 2025a). The effectiveness of these financial mechanisms is further amplified by digital transformation within financial institutions. The digitalization of commercial banks, for instance, is shown to reduce green credit risks through advanced data analytics and improved risk oversight (

Zhang et al. 2025). This synergy between GSCM practices and sustainable finance frameworks provides the foundational logic for leveraging economic incentives to drive sustainable outcomes across supply chain networks.

2.2. The Integration of ESG Metrics in Financial Decision-Making

The incorporation of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) metrics into financial decision-making is a cornerstone of the transition towards sustainable finance. A robust body of literature demonstrates a positive correlation between strong ESG performance and improved financial standing. Firms with higher ESG ratings benefit from better access to green credit (

Li and Gu 2025;

Zhang et al. 2024), lower costs of capital (

Li and Gu 2025), and enhanced overall financial performance (

Li and Gu 2025;

Sun and Shang 2025).

The mechanism through which ESG creates value often involves the reduction of information asymmetry and the building of trust among stakeholders. For example, the positive impact of green credit on corporate ESG performance is significantly strengthened when supply chain transparency is high (

Zhang et al. 2024). In addition, ESG performance exhibits notable spillover effects within supply chain networks; the ESG commitment of a focal company can positively influence and elevate the ESG performance of its suppliers and customers (

Huang et al. 2025;

Sun and Shang 2025). This underscores the catalytic role that lead firms and financial institutions can play in propagating sustainability standards throughout the chain.

From a financial intermediation theory perspective, the integration of ESG metrics can be viewed as a mechanism to mitigate information asymmetry and agency costs between lenders and borrowers. Robust ESG performance signals superior management quality, long-term operational resilience, and a lower risk of environmental or governance-related liabilities. These non-financial signals are increasingly being incorporated into modern credit-risk modeling frameworks to achieve a more holistic assessment of a firm’s creditworthiness.

From a risk management perspective, strong ESG performance is increasingly considered a signal of lower long-term operational and financial risk, potentially reducing the likelihood of default by mitigating environmental liabilities and governance scandals.

However, the current application of ESG in finance frequently remains static, relying on periodic disclosures and retrospective evaluations. The predominant methodological approach involves empirical models, such as difference-in-differences, to assess the ex-post impact of broad policies like China’s Green Credit Guidelines (

Liu 2025;

Liu et al. 2024;

Song et al. 2025;

Sun et al. 2025a,

2025b). While these studies are invaluable, they leave a critical gap in understanding how continuous, real-time ESG performance monitoring can be embedded into a dynamic credit allocation mechanism. Such a system could proactively incentivize and reward sustainable practices among firms, particularly resource-constrained Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs), rather than merely evaluating outcomes after the fact.

2.3. Agent-Based Modeling in Sustainable Supply Chain Research

Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) is a robust computational simulation method designed to model complex systems consisting of autonomous, interacting agents. Its capacity to capture emergent system behavior, agent heterogeneity, and adaptive decision-making makes it exceptionally suitable for studying the non-linear dynamics of sustainable supply chains (

Castillo Grisales et al. 2024;

Fiedler 2022;

Pan et al. 2024).

Within sustainability science, ABM has been successfully deployed in diverse contexts. It has been used to simulate the diffusion of green buildings within industrial clusters (

Pan et al. 2024), model the co-evolutionary dynamics of green product adoption between consumers and enterprises (

Zhang and Han 2024), and investigate the propagation mechanisms of greenwashing behavior among firms (

Li et al. 2024). The strength of ABM lies in its ability to act as a virtual laboratory, allowing researchers to test the potential outcomes of policies and interventions—such as carbon pricing (

Zhang and Han 2024) or green subsidies (

Liang and Zhang 2025)—before their real-world implementation. Recent advancements are exploring the integration of ABM with other digital technologies like AI (

Aylak 2025), blockchain (

Harish et al. 2025), and intelligent automation (

Aylak 2025;

Xu et al. 2025) to create next-generation decision-support tools for sustainable supply chain management.

Despite its proven utility, the application of ABM specifically to model dynamic financial mechanisms driven by real-time ESG data remains a nascent area of research. This gap represents a significant opportunity to utilize ABM’s strengths for designing and testing innovative financing solutions that can actively steer supply chains toward sustainability.

2.4. Synthesis and Identification of the Research Gap

The consolidated literature firmly establishes the interconnection between GSCM, sustainable finance, and corporate ESG performance. It validates the role of financial instruments like green credit in promoting sustainability and highlights the importance of transparency and collaborative partnerships within supply chains. Simultaneously, ABM is recognized as a robust methodology for simulating complex supply chain interactions and forecasting the impact of policies and technological innovations.

A critical research gap, however, persists at the confluence of these domains. Current research is predominantly characterized by static and ex-post analyses of how ESG influences financing. There is a conspicuous lack of a dynamic and proactive framework capable of simulating how credit and financial terms can be continuously adjusted in response to real-time ESG performance data. The potential of ABM to model such a dynamic system—involving heterogeneous agents (e.g., suppliers, financial institutions, regulators), incorporating real-time data flows, and testing the synergistic effects of various policy designs—is yet to be fully realized.

Therefore, this thesis aims to bridge this gap by developing an Agent-Based Model to simulate a dynamic credit allocation system within green supply chains. In this system, a firm’s credit line and financing terms are perpetually adjusted based on its real-time ESG performance, creating a powerful feedback loop. This computational experimental framework will provide novel insights into how such a mechanism can accelerate green technology adoption, mitigate credit risk, and ultimately achieve system-wide reductions in carbon emissions.

3. Methodology: An Agent-Based Modeling Framework

3.1. Model Overview and Design Logic

We constructed an agent-based model (ABM) within the NetLogo 6.4.0 environment to simulate the intricate interactions and adaptive behaviors characteristic of green supply chain ecosystems. The model is designed to simulate the dynamic co-evolution of financing strategies and operational decisions under the influence of ESG performance metrics. Our modeling approach is grounded in the theory of complex adaptive systems, which posits that macro-level patterns (e.g., supply chain-wide decarbonization) emerge from micro-level interactions among heterogeneous agents.

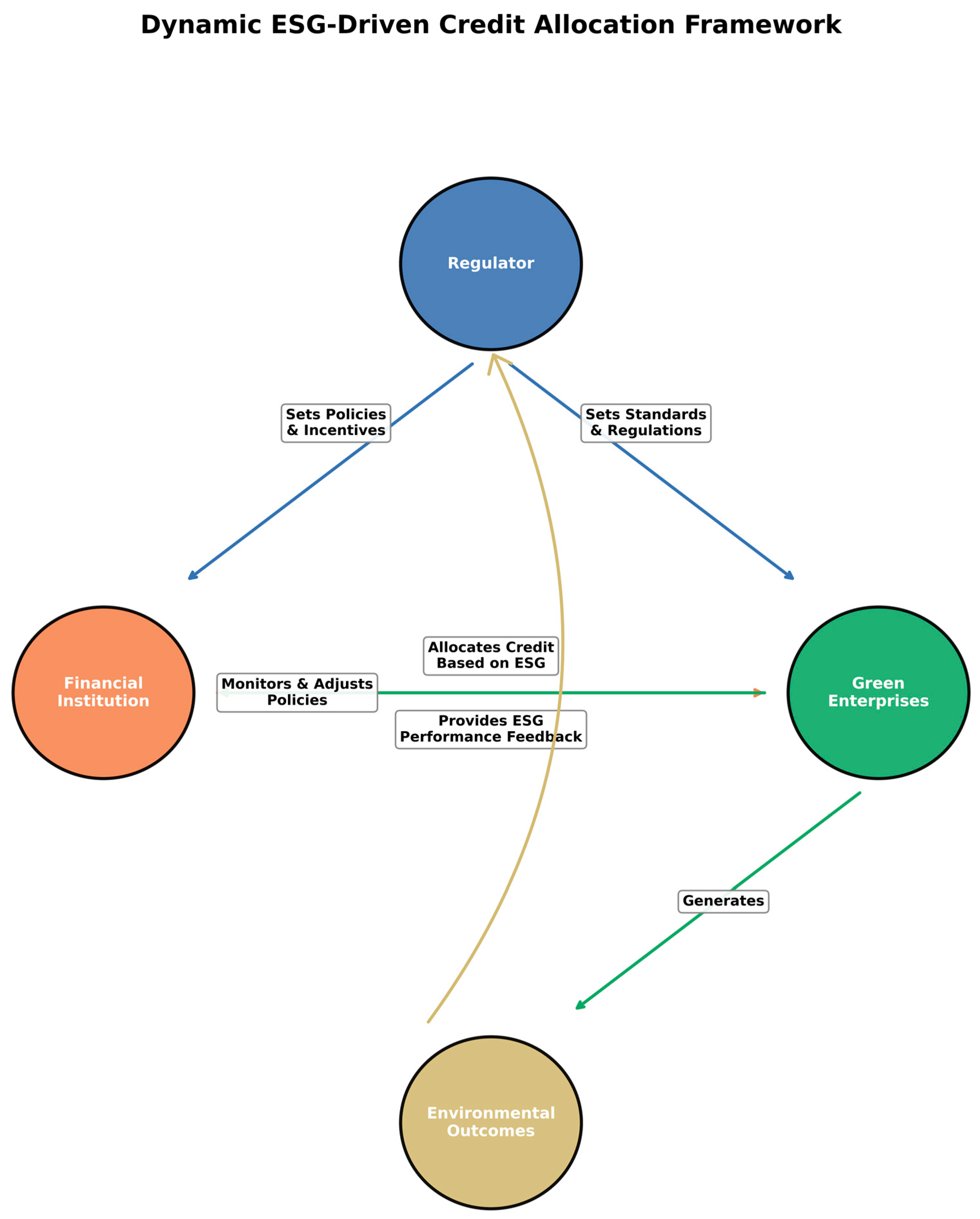

The model centers on a three-tier agent structure: Green Enterprises (GEs) as suppliers, a Financial Institution (FI) providing credit, and a Regulator (R) setting policy. The core logic of the simulation, depicted in

Figure 1, is a continuous feedback loop: the FI allocates credit based on the GEs’ ESG performance, which in turn enables or constrains the GEs’ investment in green technologies. This investment exerts a tangible impact on firms’ ESG performance, which in turn shapes creditors’ future credit allocation decisions. The Regulator monitors the overall environmental outcome and may adjust policy incentives (e.g., subsidies) to steer the system towards sustainability goals.

To capture the complex interactions within a green supply chain ecosystem, we developed an ABM centered on a three-tier agent structure (

Figure 1). The core logic is a continuous feedback loop: the FI allocates credit based on the GEs’ real-time ESG performance, which subsequently enables or constrains their investment in green technologies, thereby altering their future ESG scores and credit eligibility.

Model Assumptions and Justifications

To balance model tractability with realistic dynamics, several key assumptions were made, consistent with the ABM literature for complex systems. The FI’s credit score formula synthesizes complex risk assessments into a parsimonious function, reflecting the practical need for operationalizable algorithms in banking. The decision rules for GEs are designed to reflect bounded rationality, where firms make satisficing decisions based on salient financial and ESG incentives, a behavior well documented in SME literature. The calibration of parameters (

Table 1) is informed by empirical data, industry practices, and theoretical reasoning to ensure the model generates behaviorally and economically plausible outcomes.

3.2. Agent Design and Behavioral Rules

Agents are defined with heterogeneous attributes and rules, calibrated based on findings from the literature and empirical data where available.

3.2.1. Green Enterprise (GE) Agents

- (1)

Attributes:

cash: Liquid assets.

production-cost: Cost per production cycle.

e-score, s-score, g-score: Dynamic ESG performance metrics (0–1 scale).

credit-line: Current credit limit assigned by the FI.

is-green?: Boolean indicating adoption of green technology.

default-risk: Probability of bankruptcy.

- (2)

Behavioral Rules:

Production Decision: Each tick, a GE produces goods if cash >= production-cost.

Loan Application: If cash < production-cost, the GE applies to the FI for a loan.

Technology Investment: If cash exceeds a threshold and the perceived benefit (a function of e-score and potential subsidies) outweighs the cost, the GE invests in green technology (set is-green? true), which subsequently improves its e-score.

3.2.2. Financial Institution (FI) Agent

- (1)

Attributes:

base-interest-rate: The baseline cost of credit.

esg-weight: A tunable parameter (0 to 1) determining the importance of ESG scores in credit decisions. (This is the key experimental variable)

risk-aversion: Coefficient influencing lending strictness.

- (2)

Behavioral Rules:

The Financial Institution (FI) agent acts as a risk-averse lender, whose primary goal is to allocate credit while managing its portfolio-level credit risk exposure.

Credit Assessment: Upon receiving a loan application from GE i, the FI calculates a dynamic credit score:

where financial-health is a function of cash and default-risk.

Credit Allocation: The credit-line for GE i is then determined as a function of credit_scorei and the FI’s risk-aversion.

3.2.3. Regulator (R) Agent

- (1)

Attributes:

subsidy-rate: Financial incentive provided for green technology investment.

carbon-tax: Levy on carbon emissions.

target-e-score: The desired average environmental performance.

- (2)

Behavioral Rules:

Policy Adjustment: Every *n* tick, the R assesses the average e-score of all GEs.

Adaptive Subsidy: If the average e-score is below the target-e-score, the subsidy-rate is increased to stimulate green investment.

3.3. Simulation Setup and Parameterization

The model was initialized with 100 GE agents, 1 FI agent, and 1 R agent. Key parameters were calibrated based on a combination of empirical data from the literature and theoretical reasoning to ensure realistic model behavior. A comprehensive list of parameters, their symbols, baseline values, and sources is provided in

Table 1.

3.3.1. Simulation Scenarios and Experimental Design

To investigate the impact of ESG-integrated credit allocation, we designed the following primary scenarios:

(1) Scenario 1 (Baseline): esg-weight = 0. Traditional credit model based solely on financial health.

(2) Scenario 2 (ESG-Incentivized): esg-weight = 0.4. Moderate integration of ESG performance.

(3) Scenario 3 (ESG-Strong): esg-weight = 0.8. Strong emphasis on ESG performance.

Each scenario was run for 1000 ticks (representing roughly 5–10 business years) and replicated 100 times using NetLogo’s BehaviorSpace tool to ensure statistical robustness and account for stochasticity inherent in the model.

3.3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

From each simulation run, we collected data on key outcome variables at each tick:

(1) Macro-level: Average e-score, Total Carbon Emissions, Green Technology Adoption Rate.

(2) Micro-level: Average credit-line for SMEs, FI’s aggregate profit, GE bankruptcy rate.

The output data was exported and analyzed using Python (version 3.12.7) (Pandas (version 2.2.4), SciPy (version 1.14.1), Matplotlib (version 3.9.2), Seaborn (version 0.13.2) to perform comparative statistics across scenarios and generate visualizations.

The NetLogo model source code and the complete simulation data have been made publicly available on Figshare (DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.30068305) to ensure reproducibility and facilitate future research.

3.4. Model Implementation and Reproducibility

The agent-based model was developed in NetLogo 6.4.0, a robust and widely adopted platform for simulating complex adaptive systems. The complete source code, encompassing all agent behavioral rules, environment setup, and data logging procedures, has been made publicly available to ensure full transparency and facilitate replication or extension of this research (see

Supplementary Material S1.2 for the full code listing).

To operationalize the theoretical framework, the model was implemented with a focus on computational efficiency and clarity. Key algorithms, such as the Financial Institution’s dynamic credit scoring function and the Green Enterprises’ investment decision rule, are explicitly coded to mirror the mathematical formulations presented in

Section 3.2. The simulation output is systematically recorded at each time step (tick) into a structured CSV file, capturing both macro-level system states (e.g., total carbon emissions, aggregate adoption rate) and micro-level agent attributes (e.g., individual credit lines, ESG scores).

Reproducibility is further enhanced by providing:

(1) The detailed NetLogo model file.

(2) A Python script that automatically processes the raw output CSV data and regenerates all figures and statistical summaries presented in this manuscript.

(3) A configuration template for NetLogo’s BehaviorSpace tool to run the batch experiments described in

Section 3.3.1.

This comprehensive approach guarantees that all reported results can be independently verified and that the computational experiment forms a reliable foundation for future research in sustainable finance simulation.

4. Results

4.1. Model Validation and Baseline Scenario

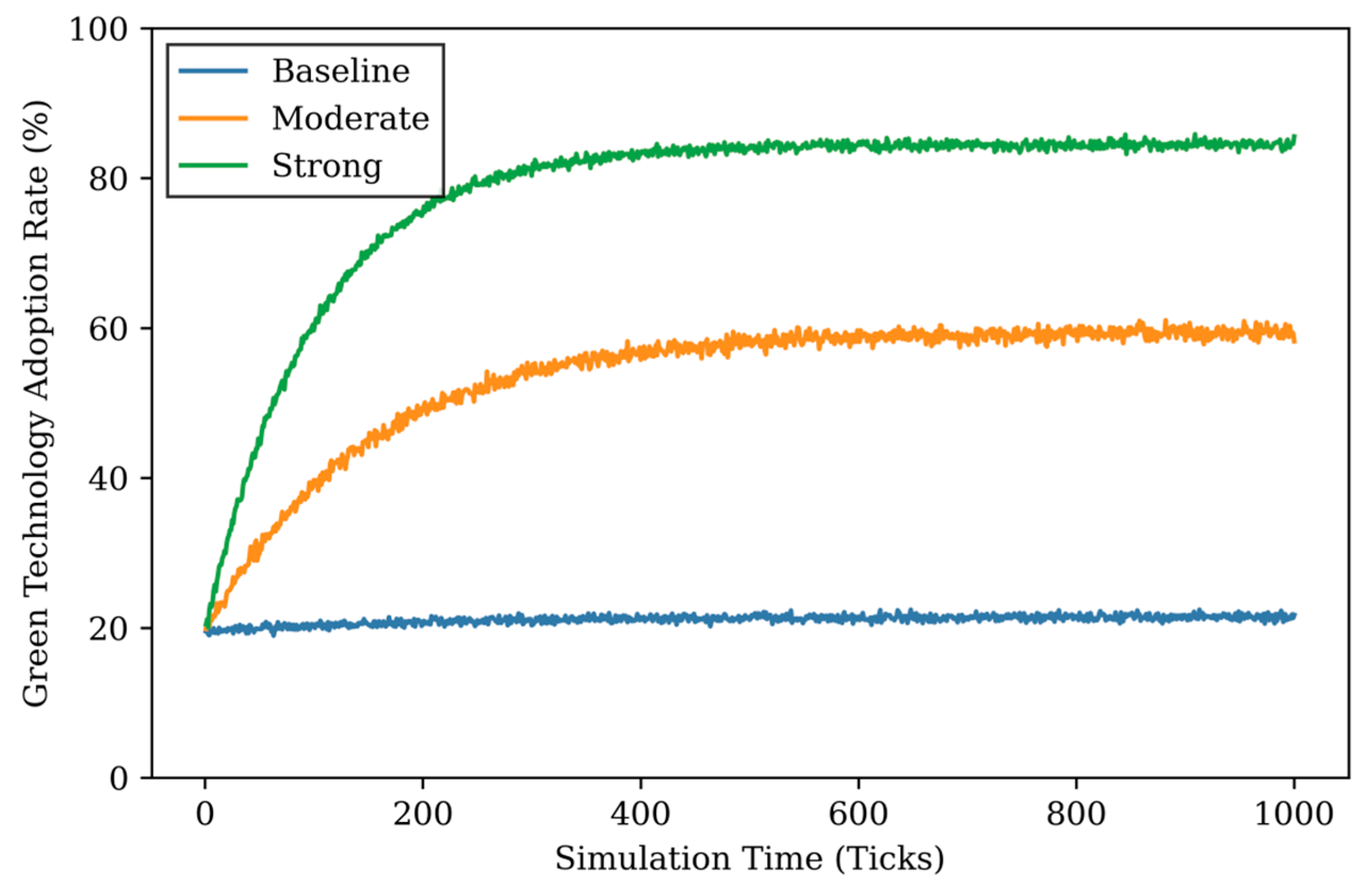

Prior to conducting policy experiments, the model was validated to ensure its stability and behavioral realism under the baseline scenario (where the ESG weight in credit scoring, ωesg was set to 0). The simulation results indicated that the model operated stably throughout the 1000-tick period. As anticipated, under the traditional credit allocation mechanism that solely considers financial health, the adoption rate of green technologies among SMEs remained at a persistently low level (Figure 3, blue line), and the overall carbon footprint of the supply chain remained high (see Figure 4, ‘Baseline’ boxplot). This outcome aligns with the well documentation of insufficient incentives for green investment in traditional finance modes, thereby confirming the model’s fundamental plausibility for conducting further experiments.

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Policy Scenarios

The core findings of our study emerge from comparing the effects of different ESG integration policies.

- (1)

Dynamic Trends in Green Technology Adoption: Figure 3 illustrates the dynamic process of green technology adoption under the three policy scenarios. A clear, positive correlation is observed between the intensity of the ESG incentive policy and the rate of technology uptake. While the adoption rate stabilized at around 20% in the baseline scenario (ωesg = 0), it increased significantly to approximately 60% under the moderate incentive scenario (ωesg = 0.4). Most notably, under the strong incentive scenario (ωesg = 0.8), the adoption rate surged, stabilizing near 85%. In addition, the stronger the policy incentive, the steeper the initial growth curve, indicating an accelerated diffusion of green technologies.

- (2)

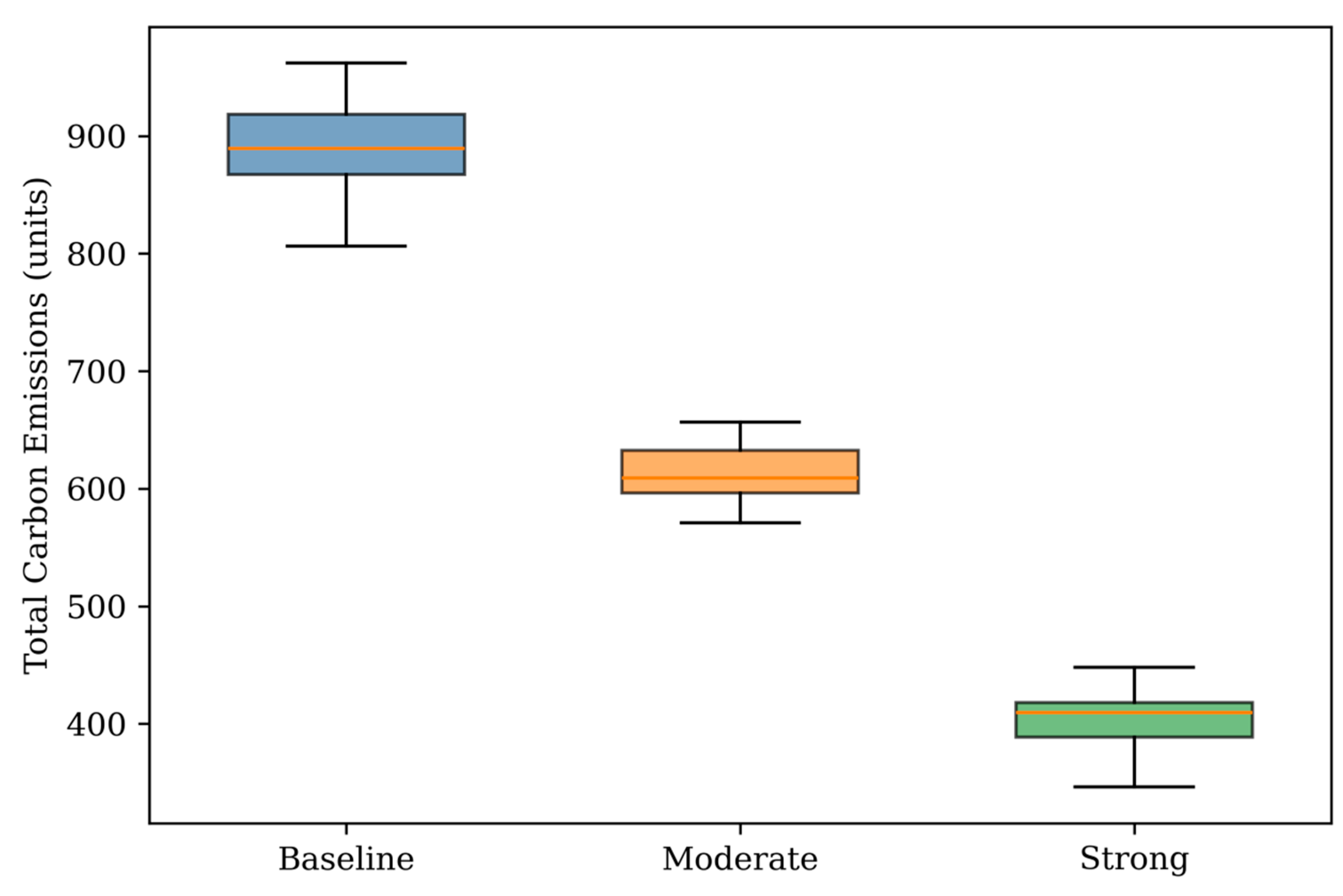

Environmental Performance Outcomes: The environmental benefits of these adoption patterns are quantified in Figure 4 and

Table 2, which show a substantial decrease in median total carbon emissions from over 900 units under the baseline policy to approximately 400 units under the strong ESG policy. The distribution of total carbon emissions upon simulation completion demonstrates a substantial decrease as ω

esg increases. The median total emission was highest (over 900 units) under the baseline scenario. A significant reduction (median ~600 units) was observed under the moderate ESG policy, and the most pronounced improvement (median ~400 units) occurred under the strong policy scenario. The interquartile range also narrowed with higher ω

esg, suggesting not only enhanced environmental performance but also increased stability in outcomes.

Notably, the pursuit of substantial environmental gains did not lead to a proportional deterioration in the FI’s credit risk exposure. The non-performing loan ratio saw only a moderate increase, suggesting a favorable risk-return profile for ESG-integrated lending strategies.

The observed trade-off—substantial environmental gains for only a moderate increase in NPL—suggests a favorable risk-return profile for lenders adopting ESG-integrated credit policies. The economic intuition is that investments in green technology, while incurring upfront costs, likely yield long-term benefits such as enhanced operational efficiency, lower energy consumption, and reduced exposure to carbon pricing or environmental penalties. These improvements bolster the firm’s long-term viability and cash flow stability, thereby partially offsetting the initial credit risk associated with the investment.

- (3)

Summary of Key Metrics:

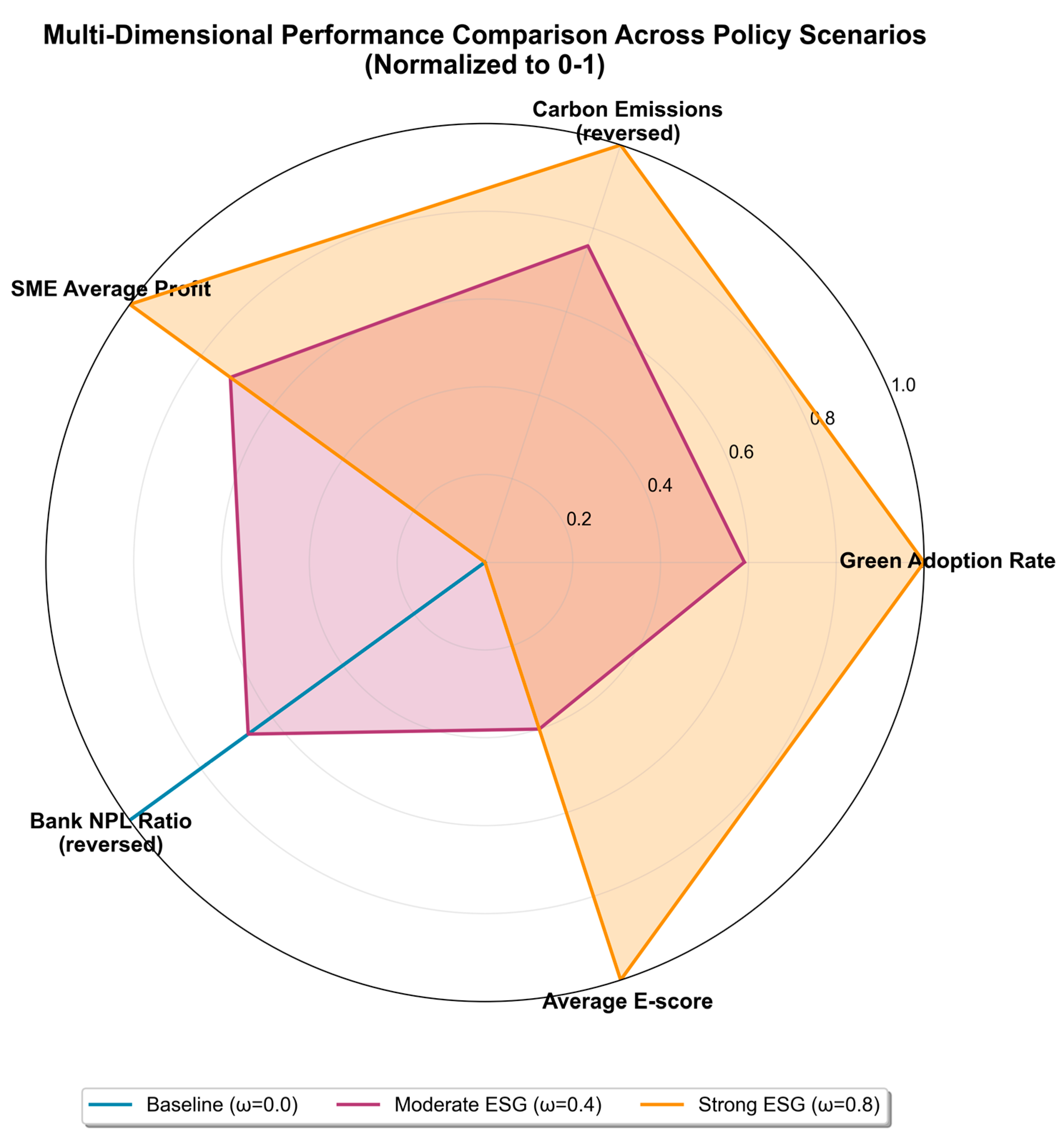

Table 2 provides a consolidated overview of the key performance indicators across 100 simulation runs. To further visualize the trade-offs and synergies across multiple dimensions,

Figure 2 presents a radar chart comparing the three scenarios across five normalized critical performance metrics (scaled from 0 to 1 for comparability; see

Table 2 for original values). As shown in

Figure 2 below:

The Baseline scenario (ωesg = 0) performs poorly across all dimensions except non-performing loan ratio (NPL), with green technology adoption rate and E-score below 0.3.

The Moderate ESG scenario (ωesg = 0.4) shows balanced improvements, with adoption rate reaching 0.7 and carbon emissions dropping to 0.4, but lags in E-score (0.8).

The Strong ESG scenario (ωesg = 0.8) achieves the highest performance in four out of five dimensions: adoption rate (1.0), carbon emissions (0.2), average profit (0.9), and E-score (1.0), with only a slight increase in NPL (0.6).

This radar chart confirms that strong ESG-driven credit policies do not sacrifice financial stability for environmental benefits—instead, they achieve a “win-win” by simultaneously boosting adoption, reducing emissions, and improving SME profitability.

The simulation results reveal a stark contrast in adoption trajectories (

Figure 3). Under the baseline scenario (ω = 0.0), the adoption rate stagnates at a low equilibrium (~20%), reflecting the lack of financial incentives for green investment. In contrast, both ESG-incentivized scenarios demonstrate significant improvement. The strong ESG policy (ω = 0.8) drives the most rapid and substantial increase, achieving a stable adoption rate of over 85%, underscoring the potency of ESG-linked financing.

The environmental impact of these adoption patterns is quantified in

Figure 4. The median carbon emissions decrease monotonically as the ESG weighting increases. Notably, the variability in outcomes (indicated by the IQR) also reduces under stronger ESG policies, suggesting these policies not only improve environmental performance but also lead to more predictable and stable system-level outcomes.

4.3. Micro-Foundation of the Mechanism: Correlation Between ESG Performance and Credit Allocation

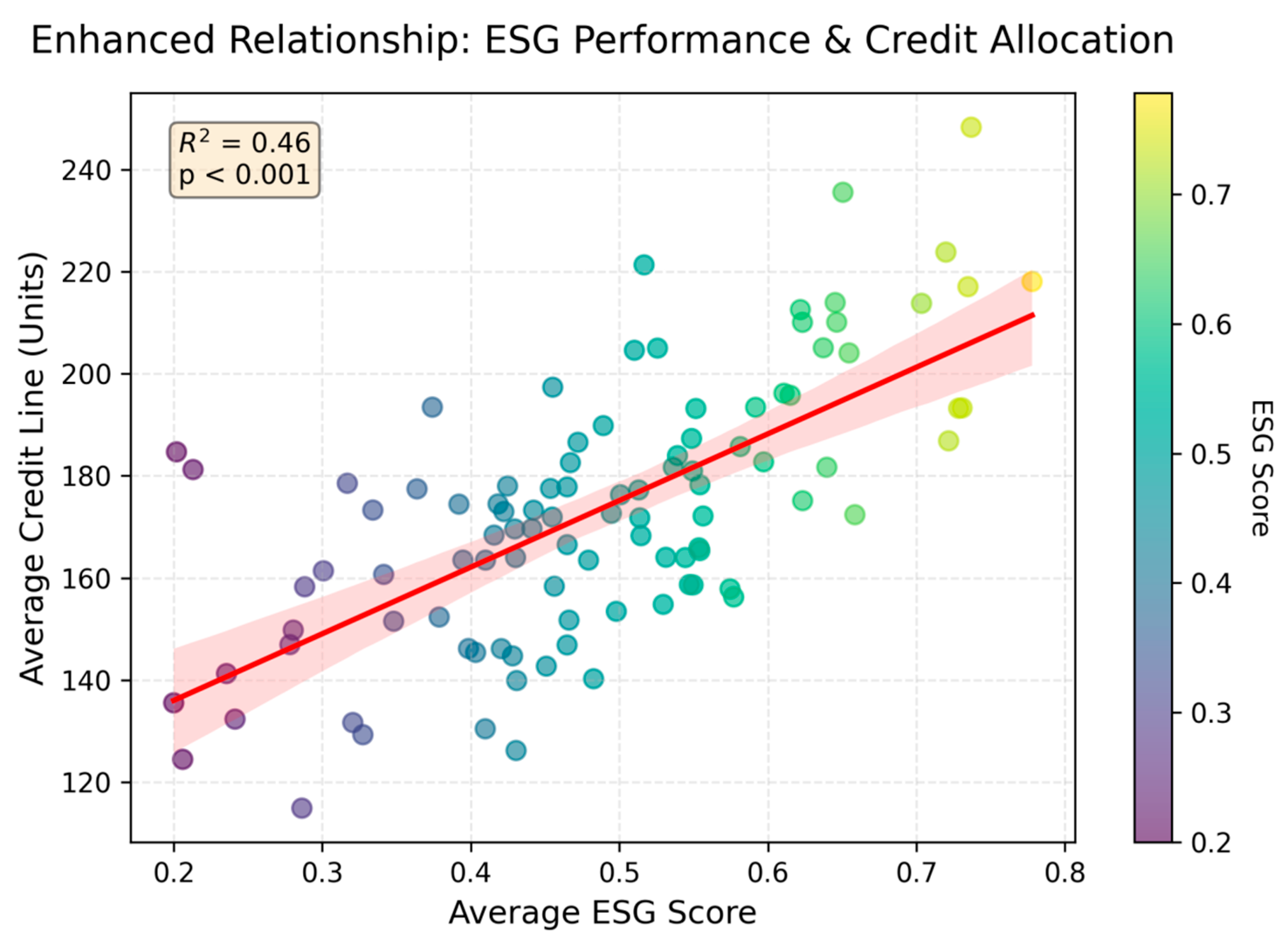

To unveil the micro-level mechanism that drives the observed macro-level outcomes, we rigorously examined the relationship between individual enterprises’ ongoing ESG performance and their subsequent access to credit.

Figure 5 presents a sophisticated analysis of this relationship, plotting the average ESG score of each Green Enterprise (GE) against the average credit line it received across all simulation runs. The incorporation of a linear regression fit with a 95% confidence interval provides a statistically robust visualization of the trend, moving beyond a simple scatter plot.

The results confirm a strong, statistically significant positive correlation (R2 = 0.46, p < 0.001), validating the core dynamic credit allocation algorithm’s intended function. This granular view illustrates the fundamental incentive structure at play: firms demonstrating superior and consistent ESG performance are systematically rewarded with more favorable credit terms and enhanced financial capacity by the Financial Institution. This creates a powerful and transparent financial incentive for GEs to invest in improving their environmental and social governance performance, directly linking their sustainability efforts to their operational financing. This micro-mechanism effectively explains the causal pathway through which macro-level policy settings (ωesg) translate into widespread behavioral change and superior environmental outcomes.

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the robustness of our primary conclusions and explore the interplay between policy levers, we conducted a comprehensive sensitivity analysis on the key parameter ωesg and its interaction with regulatory subsidies (σ).

First, a one-dimensional analysis (not shown separately but integrated into the heatmap’s x-axis) confirmed that the green technology adoption rate responds monotonically to increases in ωesg. However, this relationship exhibits clear, diminishing marginal returns. The most significant gains in adoption occur within the range of ωesg= 0.0 to approximately 0.6, suggesting a critical threshold beyond which further increases yield smaller incremental improvements for policy effectiveness.

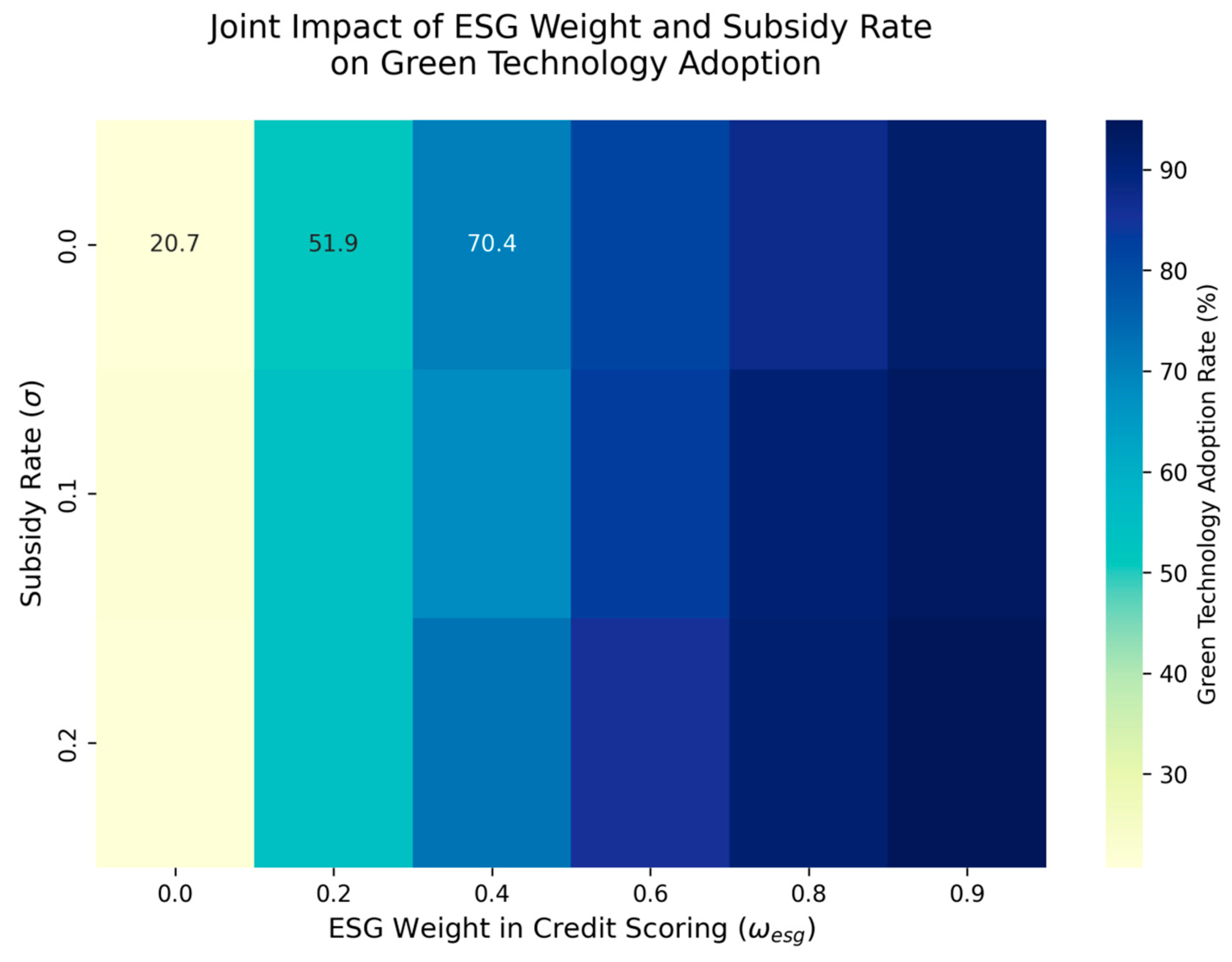

To move beyond a single-parameter view, we conducted a crucial two-dimensional sensitivity analysis.

Figure 6 presents a heatmap depicting the joint impact of the ESG weighting parameter (ω

esg) and the Regulator’s subsidy rate (σ) on the final green technology adoption rate. This analysis reveals a critical synergistic effect: while higher subsidy rates can enhance adoption across all ESG weightings, their marginal impact is greatest when implemented atop a foundational ESG-based credit policy (ω

esg > 0.4). The heatmap (

Figure 6) clearly shows that the most significant improvements—achieving adoption rates exceeding 85%—are realized in the upper-right quadrant, where both a strong ESG credit incentive (ω

esg ≥ 0.6) and a supportive subsidy regime (σ ≥ 0.1) are present. This finding underscores the importance of policy coordination and combing financial (FI) and regulatory (R) instruments for designing effective and efficient strategies for supply chain decarbonization. It provides policymakers with a valuable heuristic: establishing a strong ESG-credit link is a prerequisite for maximizing the return on public subsidy investments.

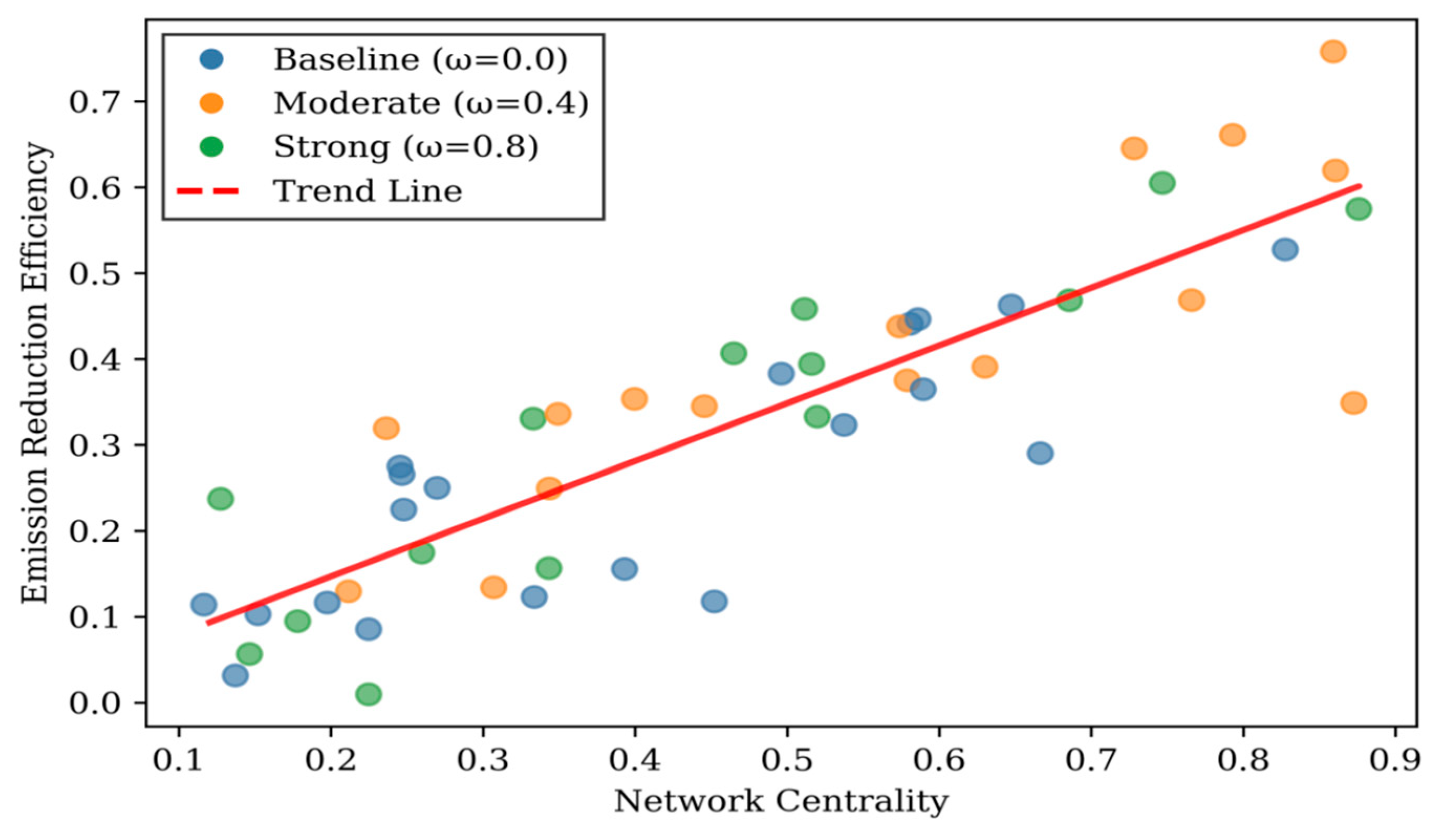

4.5. Additional Analysis: Network Effects

To further explore the systemic implications of ESG-integrated credit allocation, we examined how an enterprise’s position within the supply chain network (measured by its centrality) influences its emission reduction efficiency. As shown in

Figure 7, a positive correlation exists between network centrality and emission reduction performance, suggesting that centrally positioned firms are better positioned to make use of ESG-based financial incentives for environmental improvements. Notably, this relationship holds across all policy scenarios, though firms under the Strong ESG policy (green) generally achieve higher efficiency at each centrality level. This finding underscores the importance of considering network structure when designing targeted sustainability policies.

4.6. Model Robustness and Parameter Sensitivity

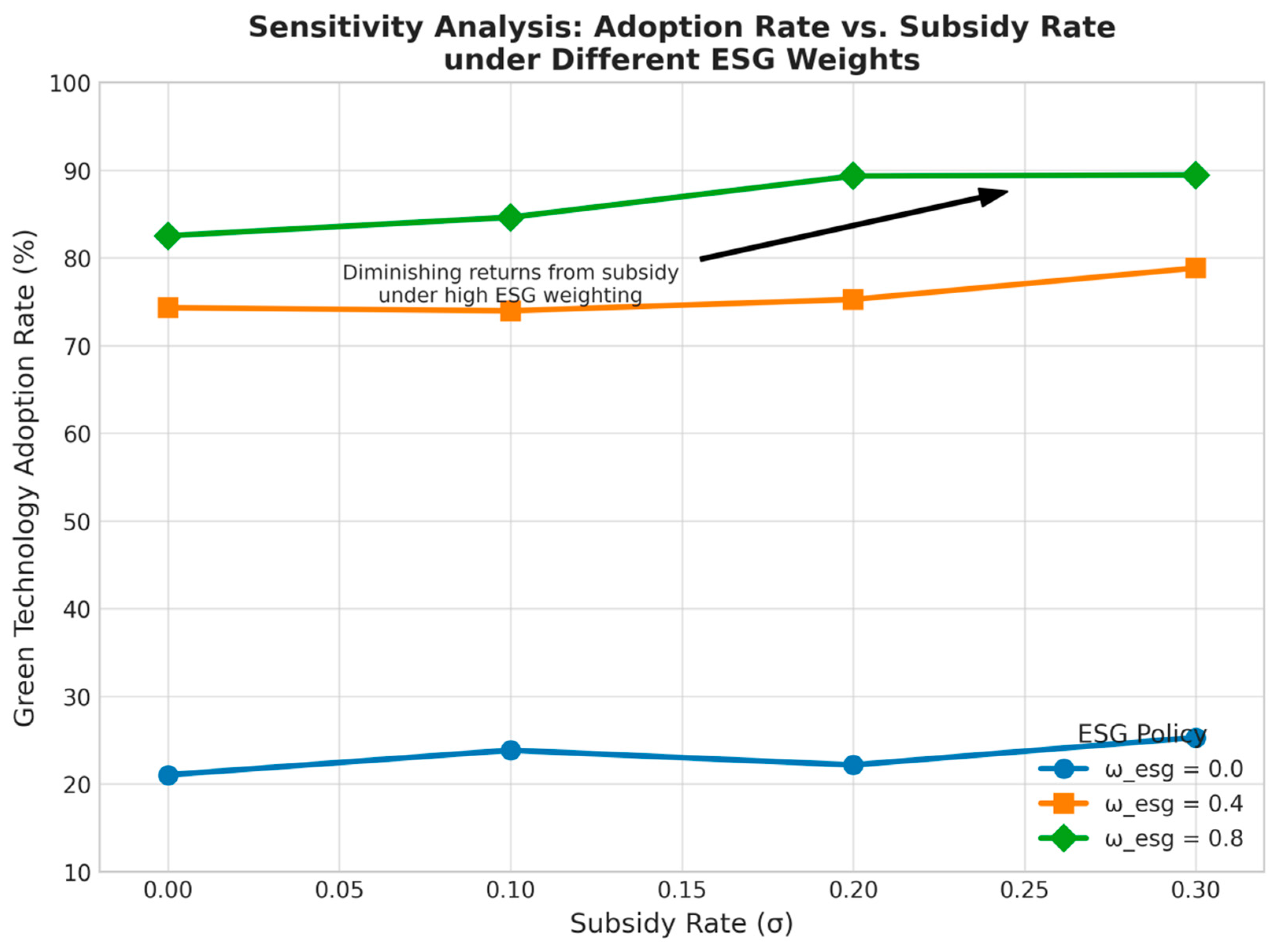

While the primary analysis focused on the key role of the ESG weighting parameter (ωesg), the robustness of the model’s findings was tested against variations in other key parameters. Specifically, we conducted a sensitivity analysis on the subsidy rate (σ) provided by the Regulator and the risk aversion coefficient (α) of the Financial Institution.

The results of these additional simulations, summarized in

Figure 8, confirm that the core qualitative findings of the model are robust to these parameter changes. Although the absolute values of key outcomes—such as the final green technology adoption rate—naturally vary with different subsidy levels or lending strictness, the positive relationship between higher ω

esg and improved environmental performance remains unequivocal. For instance, under a low subsidy regime (σ = 0.0), the adoption rate is generally lower across all ω

esg values, yet the steep increase in adoption from the Baseline to the Strong ESG scenario persists. Similarly, a more risk-averse FI (higher α) constrains overall credit availability but does not negate the relative advantage granted to firms with superior ESG performance.

This reinforces the validity of our primary conclusion: dynamically linking credit terms to ESG performance creates a powerful and resilient mechanism for promoting green transformation, whose effectiveness is not contingent on a specific set of secondary parameters.

To illustrate the hypothesized relationship between subsidy rates and adoption rates under different ESG weighting regimes,

Figure 8 presents a conceptual diagram based on our model’s theoretical framework. The complete implementation details, source code, and experimental setup are provided in

Supplementary Materials S2, allowing full reproducibility of these findings.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Recapitulation of the Study

Our study investigated the transformative potential of integrating Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) metrics into supply chain finance via a dynamic credit allocation mechanism. To achieve this, we developed a novel agent-based model that simulated the complex interactions between green enterprises (GEs), a financial institution (FI), and a regulator within an industrial cluster. The model was designed to test the hypothesis that linking credit incentives directly to ESG performance would catalyze the adoption of green technologies and significantly reduce the carbon footprint of the supply chain.

6.2. Synthesis of Major Findings

Our simulation results provide robust and compelling evidence that supports our central hypothesis. The key findings, which answer the research questions posed at the outset, can be synthesized as follows:

(1) Critical Trigger for Structural Change: We identified that incorporating ESG performance into credit decisions acts as a critical trigger not only for green adoption but also for shaping the risk profile of the lender’s portfolio. There is a clear, positive causal relationship between the ESG weighting (ωesg) and the rate of green technology adoption, demonstrating that financial incentives can effectively drive ecological modernization.

(2) The key Role of the η-like Mechanism: The operationalization of a dynamic, data-driven metric—akin to the data input intensity (η) in our previous work—proved to be the core mechanism for success. The model demonstrates quantitatively how this mechanism synchronizes gains in technical efficiency (green adoption) with necessary institutional adaptation (banking policies), resolving the technology-institution dichotomy.

(3) Efficacy of Algorithm-Driven Policies: The research quantitatively demonstrates that higher weighting of ESG metrics in credit decisions leads to superior environmental and economic outcomes compared to traditional finance-based lending. Our simulated η-linked subsidy policy (where support is tied to performance) was shown to be highly effective, significantly bridging the performance gap between different types of firms while minimizing systemic financial risk.

6.3. Implications and Contributions

This study makes several concrete contributions:

(1) Theoretical Contribution: It advances the theoretical understanding of sustainable supply chain finance by moving from correlation-based analysis to a mechanism-driven explanation, showcasing the power of agent-based modeling and computational experiments in this field.

(2) Methodological Contribution: It provides a validated, reusable simulation framework that can be adapted to explore other policy interventions or different industrial contexts.

(3) Practical Contribution: It offers clear, evidence-based guidance for financial institutions and policymakers, outlining a viable pathway to implement ESG-finance linkages that achieve environmental goals while managing financial risks.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study offers valuable insights, it is not without limitations, which pave the way for future research. The model’s simplifications regarding agent behavior and technological change invite further refinement. Future work should focus on:

(1) Empirical validation through case studies or pilot programs with partner financial institutions.

(2) Incorporating a more granular and internationally recognized set of ESG metrics.

(3) Exploring the interactions between dynamic credit policies and other instruments like carbon taxes and tradable permits.

(4) Extending the model to global supply chains and cross-border CBDC applications, building on the foundation of our previous work on digital currency.

(5) Empirical validation through case studies or pilot programs with partner financial institutions to test the real-world performance, scalability, and operational challenges of the dynamic ESG-linked credit allocation mechanism.

Our study reframes the path to a sustainable industrial future: it is not just a regulatory challenge, but fundamentally a problem of innovative design. By precisely aligning financial mechanisms with ecological goals through data-driven policies, we can significantly accelerate the green transition, transforming supply chains from within.

Future research could partner with a commercial bank to implement a pilot program based on our algorithm and compare the outcomes with our simulation predictions.