Abstract

This study examines the portfolio optimization problem of an insurance company that issues an annuity, receives the associated premiums as a lump sum, and invests in a financial market. The insurer’s objective is to determine an investment strategy that minimizes the likelihood of defaulting on annuity payments before ceasing operations, where default occurs if the portfolio value, net of the annuity liability, becomes negative. Unlike the previous work, here the mortality intensity is stochastic and follows a Cox–Ingersoll–Ross (CIR) process. Dynamic programming is employed, and the value function is characterized by a Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) equation, and the former is linearized through the Legendre transform. Numerical results show that default probability declines with higher initial wealth and mortality intensity, while stochastic mortality volatility has little impact—though slightly higher volatility marginally reduces default risk. Optimal stock investment falls with increasing wealth and mortality intensity, and is nearly constant for low wealth levels. Mortality volatility has minimal influence, but a higher Sharpe ratio raises optimal investment, underscoring the role of risk-adjusted returns.

1. Introduction

The foundations of dynamic portfolio management in continuous stochastic settings were laid by Merton (1969) and Merton (1971), with Karatzas (1989) providing a comprehensive treatment of continuous-time portfolio choice. The problem of minimizing the probability of ruin was first addressed in discrete time by Ferguson (1965) and later extended to continuous-time diffusion models by Browne (1995), who showed that the strategy minimizing ruin probability also maximizes exponential utility. In the non-life insurance context, the portfolio selection problem, aimed at minimizing ruin probability and encompassing consumption, investment, and reinsurance decisions, has been studied extensively, including in Bayraktar et al. (2008); Liang and Young (2018); Luo and Taksar (2011); Promislow and Young (2005); Schmidli (2002).

Our work builds on the framework of Browne (1995) but introduces two key innovations. First, we incorporate required benefit payments to annuitants directly into the portfolio dynamics. Second, we model mortality intensity as a stochastic process, specifically in continuous time, within the portfolio selection problem of a life insurer.

For life insurers, sustaining the ability to meet long-term obligations, particularly the timely payment of claims and benefits, is of paramount importance. Regulatory frameworks such as Solvency II and risk-based capital (RBC) regimes require insurers to hold reserves that ensure solvency with high probability, accounting for both market and longevity risks. This motivates our portfolio-wide perspective, in contrast to works such as Christiansen and Fahrenwaldt (2016) and Hinkkanen (2022), which focus on individual contracts and solvency considerations related to contract design.

The study most closely related to ours is Cahyaningtias et al. (2023), which examines the portfolio problem of an insurer issuing an annuity, receiving the premium as a lump sum, and investing in a financial market. In their model, mortality intensity is assumed to be either constant or a Brownian motion with drift. In contrast, we adopt a more realistic specification in which mortality intensity follows a Cox–Ingersoll–Ross (CIR) process. The aim of this paper is to analyze how introducing a realistic stochastic mortality intensity model, articulated by a Cox–Ingersoll–Ross process, affects the insurer’s optimal investment strategy and solvency outcomes compared to the framework of Cahyaningtias et al. (2023).

In continuous-time mortality modeling, the CIR process serves as a model for the instantaneous mortality intensity. It captures both time dependence and stochastic variability in mortality trends while, unlike the Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process, guaranteeing non-negativity. The use of the CIR process in mortality modeling was first explored by Dahl (2004), Luciano and Vigna (2005, 2008), and has since been applied in various contexts, including Blackburn and Sherris (2013); Jevtić and Regis (2019, 2021); Luciano et al. (2012), and De Rosa et al. (2021). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to apply the CIR process in the portfolio optimization problem of a life insurer.

Incorporating stochastic mortality introduces additional realism and complexity into the insurer’s portfolio optimization problem. Unlike an additional stochastic interest rate factor, stochastic mortality directly determines the timing and magnitude of insurance liabilities, altering both asset and liability dynamics, a dimension that, to our knowledge, has not been previously analyzed in this optimization context. From a technical perspective, it increases the dimensionality of the stochastic control system, making the corresponding Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) equation analytically intractable. To address this, we apply a duality approach in which the problem is reformulated through a dual value function that satisfies a linear partial differential equation. Other approaches such as Markov chain approximations (see Bayraktar et al. 2011) may be employed to tackle this problem as well.

Our main contributions are threefold. First, we derive appropriate boundary conditions for this dual formulation and prove that the dual value function is concave, allowing recovery of the original value function through the Legendre transform. Second, we introduce a numerically stable and convergent scheme for solving the resulting PDE. Third, we demonstrate that the CIR-based framework yields quantitatively different and more realistic predictions than deterministic or Brownian mortality models, with direct implications for capital adequacy and optimal investment under longevity uncertainty. The framework provides a theoretical foundation for understanding prudential investment behavior and state-dependent reserve requirements in life insurance portfolios.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the model setup, while Section 3 introduces the research objective and formulates the optimization problem. Section 4 describes the numerical analysis approach, and Section 5 reports the results of various numerical experiments. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Model Setup

Let be a two-dimension Brownian motion on a probability space The filtration is the completed filtration generated by Without loss of generality, we consider a simple financial market consisting of a savings account with interest rate This can be achieved by taking the zero-coupon bond as numéraire. Another financial instrument available for trading is a stock whose dynamics are driven by a geometric Brownian motion to model the underlying uncertainty of this risky asset with drift and volatility as follows

Suppose that an insurance company issues an annuity with payment rate i.e., at time t, the insurance company has to pay out , where denotes the proportion of clients who are alive at time t. The premiums are collected as a lump-sum at a time prior to and from this time onward, we only consider payout phase with no restriction of time horizon for the sake of simplicity. Without loss of generality, we assume that initially there is a unit mass of insureds with identical characteristics (one cohort) that buy one unit of annuity. Following Luciano and Vigna (2005), and other works in continuous time mortality modeling, we assume that the stochastic mortality intensity follows a CIR process

for some positive parameters A and The Brownian motion is used to model the underlying uncertainty of mortality intensity. A strictly positive and exponentially increasing mortality intensity means that as a life ages, the instantaneous hazard rate, i.e., the probability of dying in the next infinitesimal time interval, increases over time. This is not only biologically plausible but necessary: without an increasing hazard rate, individuals would have a positive probability of surviving indefinitely, which is clearly unrealistic.

Let be the proportion of insureds who are alive at time t, hence

Let x be the initial wealth that the company holds to service future payment. Then, the payment fund is maintained by a portfolio consisting of risky and risk-free assets. Its dynamics are given by

where denotes the proportion of wealth invested in the stock at time The wealth dynamics when parameterized through i.e., the number of stocks held at time t in the portfolio is

Let then by the stochastic product rule we have that

Suppose that is the random time when the company stops operating. This time can also represent the switching of managers, random default time, new regulations, etc. Also, assume that is exponentially distributed with intensity . Finally, let us denote as the first time when the insurance company cannot meet its obligation, i.e.,

3. Objective and Optimization Problem

We are ready at this point to formulate our objective. The company tries to select a portfolio to minimize the probability of being unable to make payments before it stops operating, i.e.,

Remark 1.

Let us point out that this portfolio problem is scaling invariant. Indeed, let be the wealth process of (1) and be the wealth with for some positive constant M and i.e., the number of stocks held in the portfolio scaled by a factor M. Then if the annuity is also scaled, i.e., , then it is clear that ; thus, Moreover

Also, let us note that given the dynamics of and this problem is time homogeneous, i.e.,

regardless of time s.

3.1. HJB Equation

By using the Dynamic Programming Principle (DPP) we obtain the following Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) equation for the value function

with boundary condition Indeed, since is exponentially distributed with intensity it follows that

We employ the martingale optimality principle (see Pham 2009, p. 102) to characterize the value function. The HJB Equation (3) states that is a submartingale, and a martingale for the optimal Indeed, Itô’s Lemma applied to yields

where the operator is defined by having

The claim follows since and .

Thus,

whence the optimality,

The optimizer in (3), given the convexity of V in x, is

The HJB equation is then rewritten as

with boundary condition Thus, the optimal proportion to be invested in the stock is

and the optimal amount invested in the stock is

3.2. Fenchel–Legendre Transform

Let us introduce the Fenchel–Legendre transform of denoted by

The function w is sometimes referred to as the dual function, and the following duality relationship holds

In our analysis we work with the dual function w which is proved to be concave, and as such, the value function is obtained through (7) and it is convex.

The following first-order and second-order conditions hold

Moreover, by differentiating with respect to in (6) and (7), and using differentiation of the value function of an optimization problem, one gets

Thus, we arrive at the following PDE for w

with the boundary conditions Let us justify these boundary conditions. It is clear that Let us argue that It is obvious that by sending x to 0 in (6). For every there is a sufficiently large such that so Thus The boundary condition when is

where and it follows from Theorem 4.2 of Cahyaningtias et al. (2023). The existence of a solution for this elliptic PDE can be argued as in Chapter 4 of Krylov (1997).

The following theorem establishes the concavity in y for the dual value function w, which in turn yields the convexity of V in (through (7)), and as such the candidate of (4) is indeed the optimizer.

Theorem 1.

The map is concave.

Proof.

Let us introduce the stochastic process given by the SDE

In fact

□

Then, the process

is a martingale. Let be the first time the process hits 0. Let us denote the function as , i.e.,

which is a concave function in Let us denote ; then, the martingale property of yields

The concavity of w in y yields from the concavity of F and the multiplicative dependence on the initial condition of the process of (10). This completes the proof.

In light of the dual relationships, we can express in terms of the dual function.

4. Numerical Analysis

We discretize the linear PDE in (9), with and :

using second-order accurate central differences (see LeVeque 2007), where and . Also, the original boundary conditions are

where . Note that the important range of is .

Computationally we will take and where and , with and . The boundary conditions become

We label , with . Then the discrete equations for the linear PDE are

Stacking the unknowns for into a vector for , we write the discrete equations as , where b incorporates the boundary conditions. Due to the five-point stencil for second-order accurate central differences, M will be a banded matrix with five diagonals (main, sub- and super-diagonals, and sub- and super-fringes). This linear equation is then solved using a banded-matrix direct solve; LeVeque (2007).1

5. Numerical Experiments

In this section, we computed and plotted the probability of default and the corresponding optimal investment by using the following parameters: , , , , , , , , , , and .

Our choice of drift and volatility parameters for the risky asset are stylized but intentionally chosen to represent an insurance company’s diversified investment portfolio rather than a single stock. Insurance portfolios typically consist of a dominant proportion of fixed income securities and equities, resulting in substantially lower aggregate volatility than individual assets. Our volatility parameter of 5% aligns well with diversified insurer portfolios, while the drift parameter reflects a portfolio with higher equity allocation during favorable market conditions and is consistent with an insurer pursuing enhanced returns through strategic allocation to growth assets and alternative investments.

For the CIR mortality intensity parameters, we set and . While these values are stylized middle-aged life (or healthier retiriment age cohort), they are in line with the empirical findings of Luciano and Vigna (2005), who estimate non-mean-reverting CIR processes for mortality intensity using UK population data from the Human Mortality Database.

Our parameter represents a stylized aggregate intensity that captures the low but non-zero probability of regime change. Given that the expected time to regime change is years, our assumption is that the company will be a going concern with no short- or medium-term breaks due to regulatory changes, management turnover, strategic restructuring, etc. Finally, the finite difference discretization employs grid points in the wealth direction , yielding a spatial resolution of , and grid points in the dual variable and mortality intensity directions, giving and , respectively. The ten-fold refinement in the x-direction relative to y is motivated by the need to accurately capture the steep value function gradients near the bankruptcy boundary, where and must be computed with sufficient precision to determine the optimal investment fraction.

5.1. The Value Function

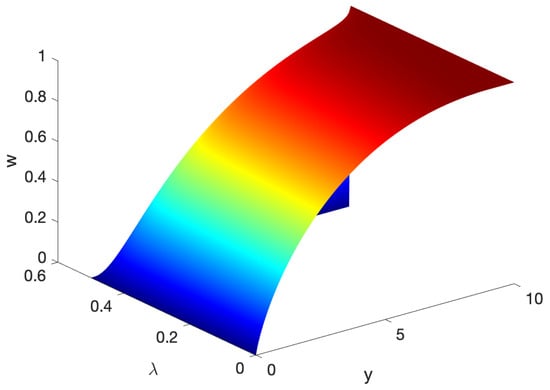

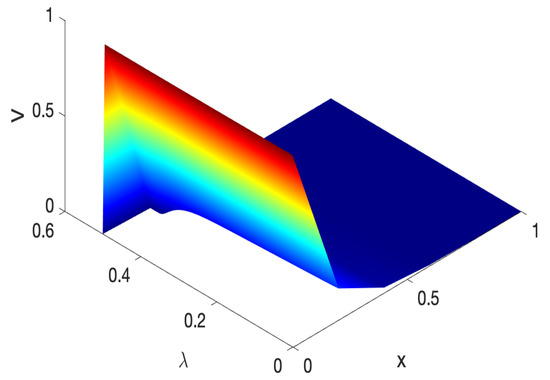

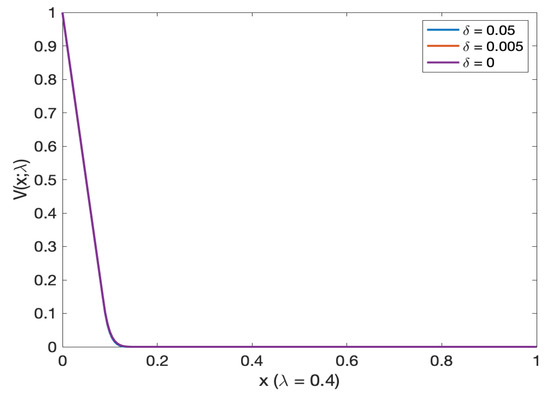

By using the parameters above, we plotted the dual value function. As we see in Figure 1, the dual value function is increasing and concave in the dual variable. We also see from Figure 2 that the value function is decreasing and convex in the initial wealth.

Figure 1.

Dual value function (see Equation (6)).

Figure 2.

The probability of default as a function of mortality intensity and initial wealth.

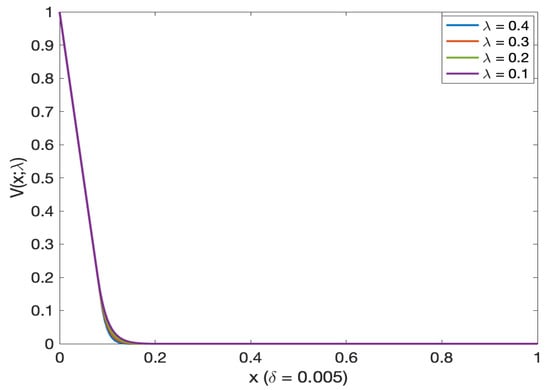

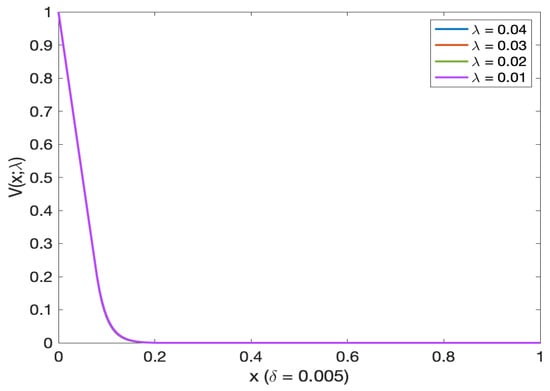

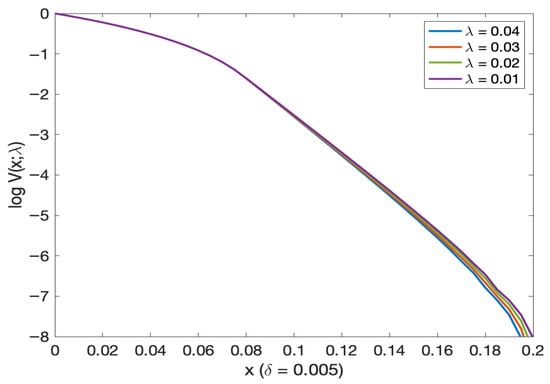

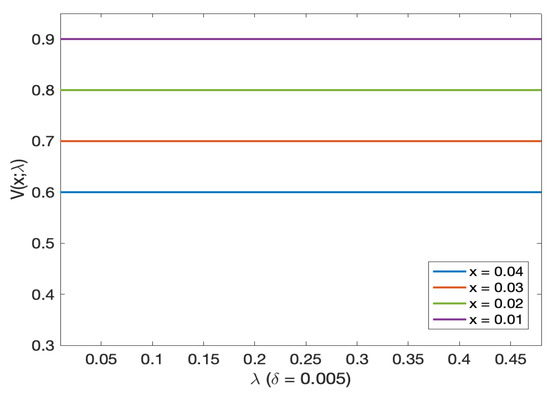

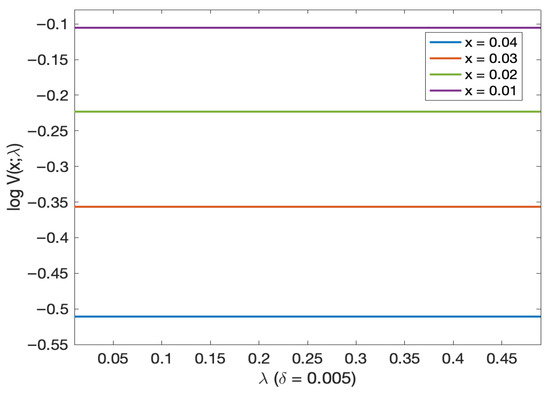

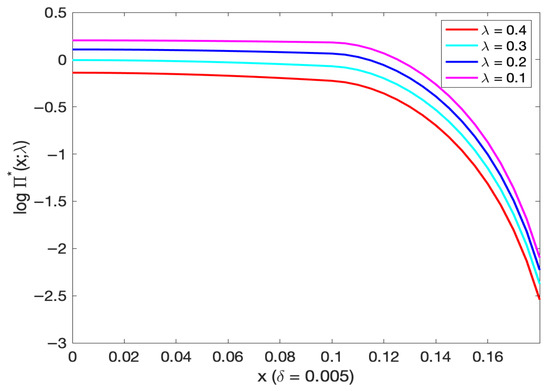

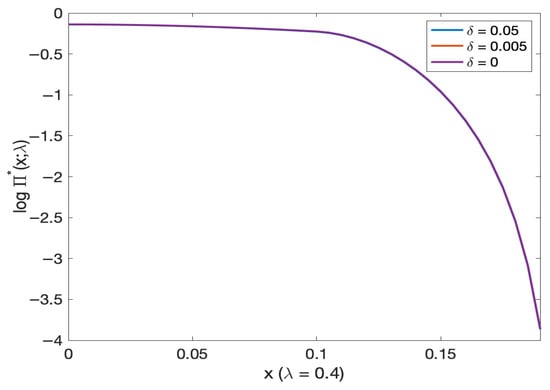

Figure 3 (log probability of default in Figure 4) and Figure 5 (log probability of default in Figure 6) illustrated the probability of default (and, respectively, log probability of default in Figures as a function of initial wealth for different mortality intensity levels). We see that the probability of default decreases as we increase the initial wealth (this is true for all different initial mortality intensities). This probability approaches 0 as the initial wealth exceeds 0.15. From Figure 5 (and Figure 6) we see that the probability of default is almost the same for very small levels of initial mortality intensity. From Figure 7 (and Figure 8 on log scale) for very small initial wealth levels, the probability of default does not change with mortality intensity.

Figure 3.

Probability of default as a function of initial wealth for different mortality intensity levels. Note: All lines almost visually overlap.

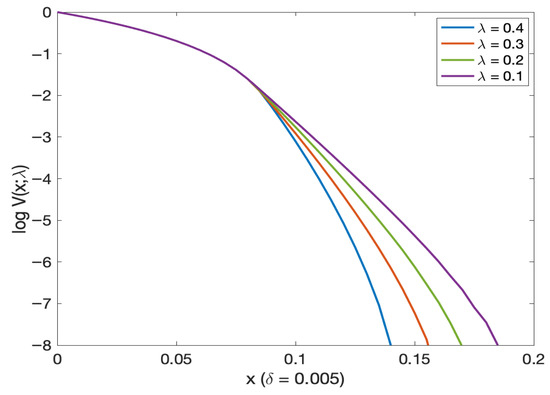

Figure 4.

Log of the probability of default as a function of initial wealth for different mortality intensity levels.

Figure 5.

Probability of default as a function of initial wealth for different mortality (small) intensity levels. Note: All lines visually overlap.

Figure 6.

Log of the probability of default as a function of initial wealth for different (small) mortality intensity levels.

Figure 7.

Probability of default as a function of mortality intensity levels for different initial wealth levels.

Figure 8.

Log of the probability of default as a function of mortality intensity levels for different initial wealth levels.

Additionally, we see from Figure 9 that the probability of default decreases as the mortality intensity increases, as expected. Suppose the initial mortality intensity is higher than 0.1. The probability of default is very close to zero. In addition, the curves corresponding to , , and are identical to zero.

Figure 9.

Probability of default as function of mortality intensity levels for different initial wealth levels.

We notice that the probability of default is lower in stochastic intensity models and this effect is more pronounced if the volatility of mortality intensity is increased. Let us provide a theoretical justification for this result; for this, consider two models for the stochastic intensity

with Then, by Theorem 4.1 in Hajek (1985), dominates in the following sense

for every convex nondecreasing function The lower probability of default is then explained by a higher expected drift in Equation (2).

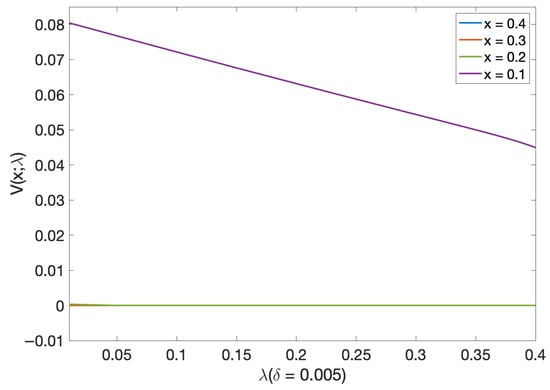

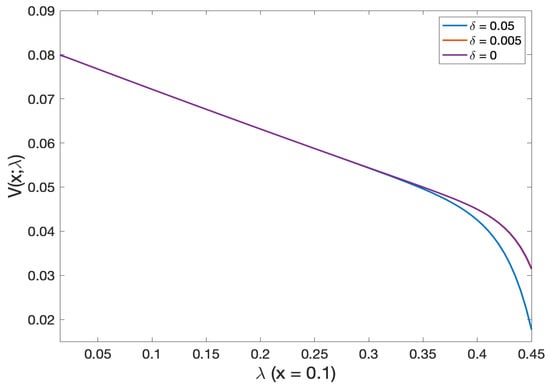

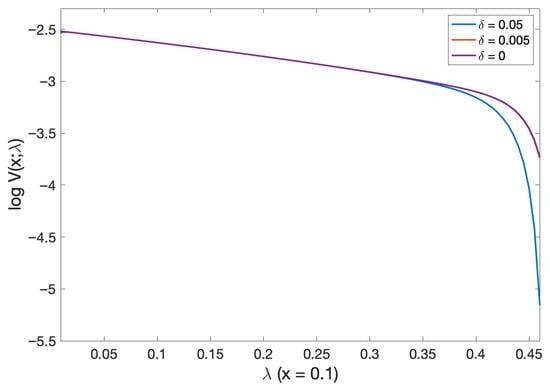

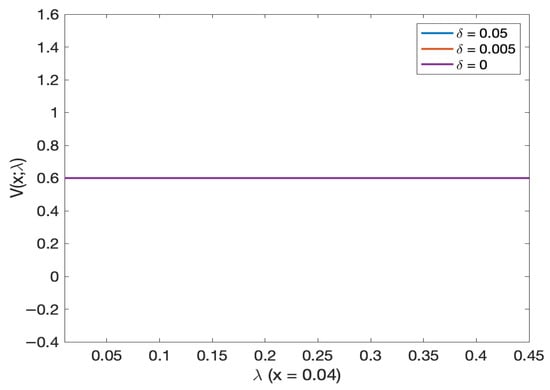

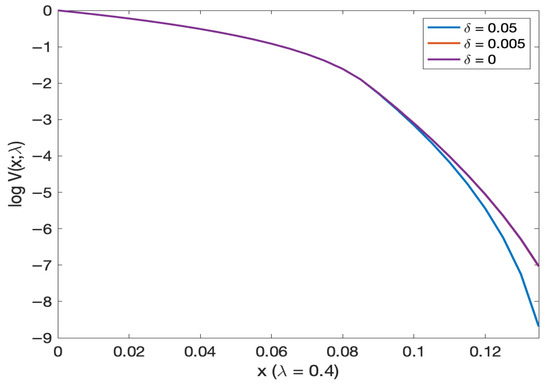

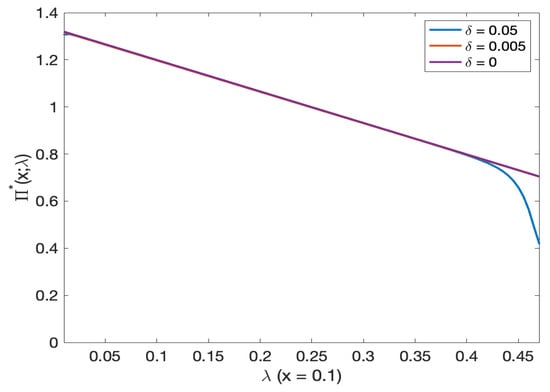

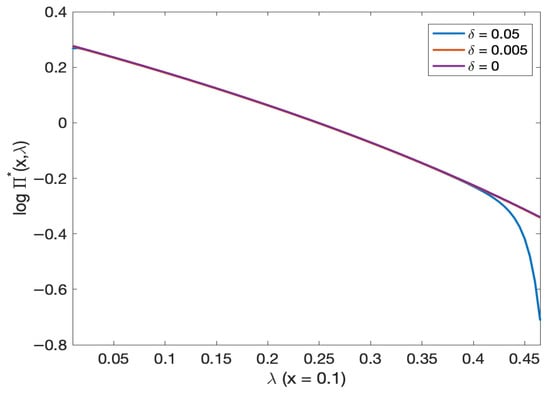

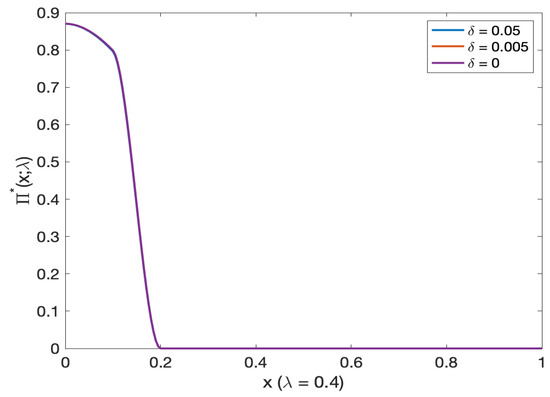

We see from Figure 10 that the probability of default (or log probability of default in Figure 11) is more negligible for the higher volatility of the stochastic mortality intensity (see Lemma 2 for an intuition of this result). Meanwhile, from Figure 12, we found that for very small initial wealth, the probability of default is the same for all different values of volatility intensity. Then from Figure 13 the probability of default (and, log probability of default in Figure 14) shares is approximately the same for varying volatility of stochastic models. Moreover, we see that the probability of default decreases as we increase the initial wealth and gets very close to zero.

Figure 10.

Comparison of probability of default as a function of wealth in deterministic versus stochastic mortality intensity models. Note: Red and purple line almost overlap.

Figure 11.

Comparison of log of the probability of default as a function of wealth in deterministic versus stochastic mortality intensity models. Note: Red and purple line almost overlap.

Figure 12.

Comparison of probability of default as a function of wealth in deterministic versus stochastic mortality intensity models. Note: All lines almost overlap.

Figure 13.

Comparison of probability of default as a function of mortality in deterministic versus stochastic mortality intensity models. Note: All lines almost overlap.

Figure 14.

Comparison of log of probability of default as a function of mortality in deterministic versus stochastic mortality intensity models. Note: Red and purple lines almost overlap.

5.2. The Investment Strategy

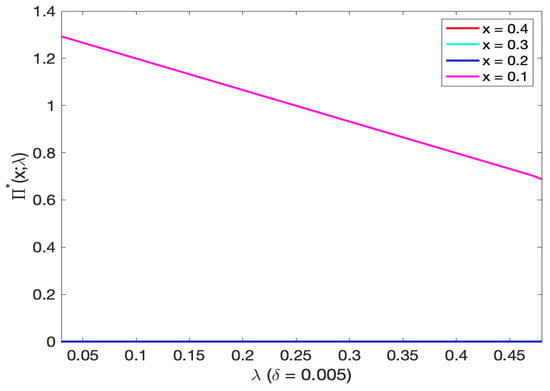

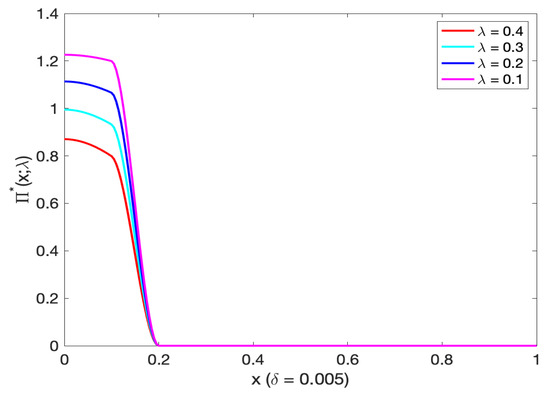

From Figure 15, we see that the optimal investment decreases as the mortality intensity increases. The optimal investment is nearly zero if the initial wealth is higher than 0.1. When and , the curves of the optimal investment are zero. From Figure 16 (and Figure 17 on log scale) we found that the optimal investment decreases as both the initial wealth and mortality intensity increase. The optimal investment approaches zero after exceeding 0.19.

Figure 15.

The optimal investment and initial wealth for different mortality intensity levels. Note: Aside from pink line, remaining lines visually overlap with the blue line.

Figure 16.

The optimal investment and mortality intensity for different initial wealth levels.

Figure 17.

The optimal investment and mortality intensity for different initial wealth levels (log scale).

5.2.1. Comparison with Deterministic Intensity Model

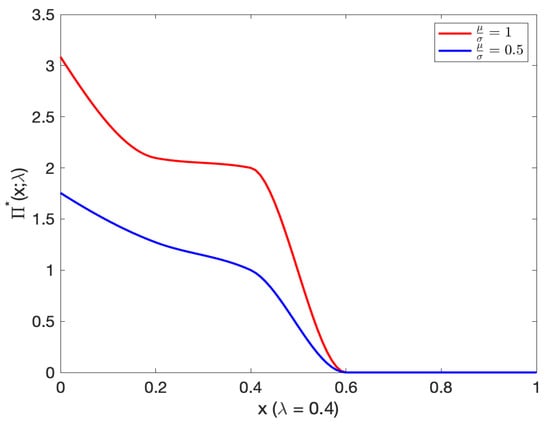

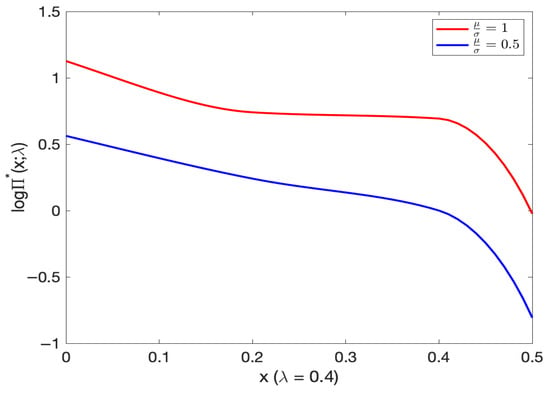

For varying volatility of stochastic models, the optimal investment decreases by increasing the initial mortality intensity (see Figure 18 and on a log scale Figure 19). In addition, the optimal investment for is slightly lower than other stochastic model volatility. The amount invested in the stock decreases with the initial wealth (see Figure 20 and Figure 21).

Figure 18.

Comparison of optimal investment and initial wealth in deterministic versus stochastic mortality models. Note: Red and purple lines visually overlap.

Figure 19.

Comparison of optimal investment and initial wealth in deterministic versus stochastic mortality models (log scale). Note: Red and purple lines visually overlap.

Figure 20.

Comparison of optimal investment and mortality intensity in deterministic versus stochastic mortality models. Note: All lines visually overlap.

Figure 21.

Comparison of optimal investment and mortality intensity in deterministic versus stochastic mortality models (log scale). Note: All lines visually overlap.

5.2.2. Dependence on Sharpe Ratio

The optimal investment decreases as initial wealth increases for varying Sharpe ratios, (See Figure 22 and Figure 23). Moreover, the optimal investment with (, ) was slightly higher compared with (, ).

Figure 22.

Comparison of optimal investment and initial wealth in varying Sharpe ratio.

Figure 23.

Comparison of optimal investment and initial wealth in varying Sharpe ratio (log scale).

5.3. Interpretation in Terms of Reserves and Capital Requirements

In our work, the value function represents the probability that a life insurance company with initial wealth x and current mortality intensity defaults (ruins) before the random termination time . In actuarial terms, thus links an insurer’s capital position to its probability of default. It therefore provides the key ingredient needed to determine risk-based reserves, i.e., the level of assets required to guarantee that the company remains solvent with a prescribed probability.

Regulatory and internal solvency frameworks (e.g., Solvency II or RBC in the U.S.) specify a target level of tolerable default probability , typically between and over the planning horizon. Given this safety level, the minimal initial wealth that achieves it under our model conditions is defined as the required reserve

Because is continuous and strictly decreasing in x (as shown in our numerical results), there exists a unique solution to (15) for each . Thus, the value function computed from the dual PDE, in a purely numerical procedure, can be directly inverted along the x-axis to obtain the reserve function for any desired tolerance .

Equation (15) thus establishes a one-to-one mapping between the level of available capital and the associated solvency probability. Higher initial wealth reduces the likelihood of default, while higher mortality intensity (which corresponds to shorter expected lifetime of the insured population) also decreases the probability of default because future annuity obligations become smaller in expectation. Hence, a mortality improvement (lower ) requires higher reserves, whereas greater mortality volatility increases capital needs due to higher uncertainty about future liabilities. Our numerical results confirm these qualitative patterns.

The comparative analysis between deterministic and stochastic mortality models reveals that introducing CIR stochastic mortality reduces across the entire domain of x, indicating lower default probabilities for the same initial wealth. Consequently, the reserve required to achieve a fixed solvency target is lower under stochastic mortality than under deterministic assumptions. This implies reduction in required reserves purely due to the more realistic stochastic representation of longevity dynamics. Ignoring mortality stochasticity can therefore lead to overly conservative reserve estimates and inefficient capital allocation.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

We conclude by summarizing the main findings, outlining the main contributions of this work, and elucidating directions for future research.

First, the probability of default decreases with both initial wealth and initial mortality intensity. This relationship also holds for different volatilities of stochastic intensity. The volatility of stochastic intensity has little effect on the probability of default; however, higher volatility yields slightly lower default probabilities. Higher values of stochastic mortality intensity also result in marginally lower default risk, while for very small initial mortality intensities, the probability of default remains essentially unchanged.

Thus, in the more realistic stochastic intensity model developed in this paper, we obtain the opposite result relative to the constant or Brownian mortality assumptions in Cahyaningtias et al. (2023): the probability of default is lower in stochastic intensity models, and this effect becomes more pronounced as the volatility of mortality intensity increases. Hence, compared to Cahyaningtias et al. (2023), the results show that incorporating a CIR-based stochastic mortality process provides new quantitative insights.

Second, the optimal amount invested in the stock is decreasing in the initial wealth and the initial mortality intensity; it is nearly constant for small values of initial wealth. The volatility of stochastic intensity has little effect on the optimal investment; for higher values of stochastic mortality intensity, we see slightly lower values for the optimal amounts invested in stock. We see higher values for the optimal amount invested in stock as Sharpe ratio gets larger.

Thus, in the context of a realistic mortality intensity model, the insight of decreasing pattern of the optimal allocation to the risky asset with respect to wealth and mortality intensity represents the paper’s main economic insight. It formalizes a prudential, solvency-preserving behavior that arises endogenously from the optimization framework. When the insurer’s wealth (capital) increases, the marginal benefit of taking additional market risk declines relative to the potential cost of default, leading to a reduction in risky investment. Likewise, when mortality intensity (liability risk) rises, the model prescribes a more conservative portfolio to preserve liquidity and solvency.

This behavior is consistent with the risk-sensitive principles underlying Solvency II and risk-based capital (RBC) regimes. Specifically, our model derives from first principles why prudent insurers would endogenously reduce risky asset allocation as capital increases or liability risk rises. The model thus provides a theoretical foundation for understanding the economic rationale behind capital-sensitive investment behavior.

From a technical perspective, the computed value function not only determines the optimal investment policy but also yields an operational measure of capital adequacy. The reserve function derived from can be viewed as the insurer’s state-dependent solvency threshold. Our findings imply that (i) reserves decrease with mortality deterioration (higher ), (ii) reserves increase with volatility of mortality intensity, and (iii) stochastic mortality models lead to smaller, yet more accurate, reserve estimates than deterministic approaches. This interpretation establishes a clear practical link between the theoretical optimization framework and real-world solvency management under longevity uncertainty.

In addition, the model serves as a quantitative tool for evaluating the appropriate level of risky investment given an insurer’s solvency position or liability structure. It enables stress testing of default probabilities and optimal allocations under regulatory-like scenarios such as mortality shocks, capital erosion, or market downturns. Finally, it establishes a basis for future extensions, such as multi-cohort portfolios, to assess diversification and longevity-hedging effects within solvency capital modeling.

Specifically, starting from De Rosa et al. (2021), one may extend the framework first to two cohorts, with mortality modeled through their respective stochastic intensities as

for some positive parameters and , . Here and denote independent Brownian motions, though the model can easily be generalized to allow for correlated Brownian motions.

Our setting naturally admits a straightforward extension to multiple cohorts. Let denote the proportion of individuals in cohort i who are alive at time t,

Under this two-cohort structure, the wealth dynamics of the insurer are given by

where, as before, denotes the proportion of wealth invested in the stock at time t.

Let represent the random time at which the company ceases operations, assumed to be exponentially distributed with intensity , and define the bankruptcy time

The insurer’s optimization problem is then to minimize the probability of default before cessation:

The associated value function satisfies a Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) equation. The analytical challenge arises because the value function depends on the cumulative mortality intensity processes , , which increases the effective dimensionality by three relative to the single-cohort case. Consequently, the dual value function also satisfies a higher-dimensional partial differential equation. Thus, developing a numerically stable and convergent scheme for solving this PDE represents an important direction for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.J. and T.A.P.; Methodology, S.C., C.G. and T.A.P.; Software, S.C. and C.G.; Validation, S.C.; Formal analysis, S.C., P.J., C.G. and T.A.P.; Writing—original draft, C.G., P.J., C.G. and T.A.P.; Writing—review & editing, S.C., P.J., C.G. and T.A.P.; Visualization, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Traian A. Pirvu declares funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) grant 5-36700.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Our central-difference discretization is second-order accurate. Since we have a consistent discretization if we prove stability, the Lax-Richtmyer Equivalence Theorem (see LeVeque 2007, chap. 9) implies convergence as well. The direct solve is stable as long as 16 decimal digits of precision for arithmetic in IEEE double precision, since up to decimal digits may be lost in the course of Gaussian elimination (Wilkinson’s Theorem on Roundoff Error in Gaussian Elimination—see Moler 2004, chap. 2). In this context, cond(M) represents the condition number of the matrix M, quantifying the sensitivity of the solution w to minor perturbations in the input b or rounding errors during the solution procedure. A higher cond(M) signifies a more ill-conditioned system, implying that minor inaccuracies or rounding errors may result in significant discrepancies in. For a grid, , so we are losing at most 6.2 decimal digits in Gaussian elimination, leaving almost 10 decimal digits of precision (the finer the grid, the higher the condition number). As a further check, the norm of the residual . |

References

- Bayraktar, Erhan, Kristen S. Moore, and Virginia R. Young. 2008. Minimizing the probability of lifetime ruin under random consumption. North American Actuarial Journal 12: 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, Erhan, Xueying Hu, and Virginia R. Young. 2011. Minimizing the probability of lifetime ruin under stochastic volatility. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 49: 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, Craig, and Michael Sherris. 2013. Consistent dynamic affine mortality models for longevity risk applications. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 53: 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, Sid. 1995. Optimal investment policies for a firm with a random risk process: Exponential utility and minimizing the probability of ruin. Mathematics of Operations Research 20: 937–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyaningtias, Sari, Petar Jevtic, Traian A Pirvu, and Tuan Tran. 2023. Minimizing bankruptcy probability of a life insurer-some analytical considerations. University Politehnica of Bucharest Scientific Bulletin-Series A-Applied Mathematics and Physics 85: 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, Marcus C., and Matthias Albrecht Fahrenwaldt. 2016. Dynamics of solvency risk in life insurance liabilities. Scandinavian Actuarial Journal 2016: 763–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Mikkel. 2004. Stochastic mortality in life insurance: Market reserves and mortality-linked insurance contracts. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 35: 113–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, Clemente, Elisa Luciano, and Luca Regis. 2021. Geographical diversification and longevity risk mitigation in annuity portfolios. ASTIN Bulletin: The Journal of the IAA 51: 375–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, Thomas S. 1965. Betting systems which minimize the probability of ruin. Journal of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics 13: 795–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, Bruce. 1985. Mean stochastic comparison of diffusions. Zeitschrift für Wahrscheinlichkeitstheorie und Verwandte 68: 315–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkkanen, Onni. 2022. Backward Stochastic Differential Equations in Dynamics of Life Insurance Solvency Risk. Master’s thesis, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Jevtić, Petar, and Luca Regis. 2019. A continuous-time stochastic model for the mortality surface of multiple populations. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 88: 181–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevtić, Petar, and Luca Regis. 2021. A square-root factor-based multi-population extension of the mortality laws. Mathematics 9: 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzas, Ioannis. 1989. Optimization problems in the theory of continuous trading. SIAM Journal on Control and Optimization 27: 1221–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krylov, Nikolaĭ Vladimirovich. 1997. Lectures on Elliptic and Parabolic Equations in Hölder Spaces. Providence: American Mathematical Society. [Google Scholar]

- LeVeque, Randall J. 2007. Finite Difference Methods for Ordinary and Partial Differential Equations: Steady-State and Time-Dependent Problems. Philadelphia: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Xiaoqing, and Virginia R. Young. 2018. Minimizing the probability of ruin: Two riskless assets with transaction costs and proportional reinsurance. Statistics and Probability Letters 140: 167–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, Elisa, and Elena Vigna. 2005. Non Mean Reverting Affine Processes for Stochastic Mortality. Technical Report. Rochester: SSRN. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano, Elisa, and Elena Vigna. 2008. Mortality risk via affine stochastic intensities: Calibration and empirical relevance. Belgian Actuarial Journal 8: 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano, Elisa, Luca Regis, and Elena Vigna. 2012. Delta–gamma hedging of mortality and interest rate risk. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 50: 402–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Shangzhen, and Michael Taksar. 2011. On absolute ruin minimization under a diffusion approximation model. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 48: 123–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, Robert C. 1969. Lifetime portfolio selection under uncertainty: The continuous-time case. The Review of Economics and Statistics 51: 247–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, Robert C. 1971. Optimum consumption and portfolio rules in a continuous-time model. In Stochastic Optimization Models in Finance. Technical Report. Cambridge: Academic Press, pp. 621–61. [Google Scholar]

- Moler, Cleve B. 2004. Numerical Computing with MATLAB. Philadelphia: SIAM. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Huyên. 2009. Continuous-time Stochastic Control and Optimization with Financial Applications. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, vol. 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promislow, S. David, and Virginia R. Young. 2005. Minimizing the probability of ruin when claims follow brownian motion with drift. North American Actuarial Journal 9: 110–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidli, Hanspeter. 2002. On minimizing the ruin probability by investment and reinsurance. The Annals of Applied Probability 12: 890–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).