1. Introduction

China’s capital market has grown rapidly but remains highly volatile, with sharp swings in stock prices undermining investor confidence and threatening systemic stability. A particular concern is stock price crash risk, sudden, severe declines in firm value often linked to the accumulation and delayed disclosure of bad news by insiders (

Bao et al. 2021;

Liu et al. 2017;

Habib et al. 2018). Prior research identifies a wide range of antecedents, including information opacity, weak internal controls, executive characteristics, and equity pledging by controlling shareholders, as well as external factors such as anti-corruption campaigns, government consistency, and institutional herding (

Callen and Fang 2015;

Chen et al. 2018;

Lee and Wang 2017;

Fu et al. 2021). More recent studies extend this line of inquiry by incorporating environmental and governance dimensions. For example,

Yu et al. (

2024) show how Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) uncertainty interacts with investor attention to influence crash risk, while

Zhang and Phua (

2024) find that ESG performance is negatively related to crash risk in Chinese listed firms, highlighting the growing importance of non-financial governance factors.

Beyond China, similar mechanisms have been observed globally. For instance,

Hutton et al. (

2009) and

An and Zhang (

2013) document that managerial bad-news hoarding predicts stock price crashes in U.S. and international markets, while

Kim et al. (

2014) show that stronger corporate transparency and board independence mitigate crash risk. These findings suggest that crash-risk determinants reflect universal governance dynamics rather than country-specific anomalies.

Yet, one critical stakeholder group “employees” has received little attention in this literature (

Ali et al. 2022). Although there is emerging work in this direction, such as

Li et al. (

2019), which documents an association between ESOP announcements and reduced crash risk, subsequent research remains limited. More recent scholarship, including

Quang (

2025), emphasizes how ESOP policy design and transparency shape the risk-mitigating potential of ESOPs. Nevertheless, comprehensive evidence on the mechanisms and boundary conditions of ESOPs in China is still lacking.

ESOPs align employee wealth with firm performance, potentially encouraging monitoring, improving information flows, and fostering a longer-term orientation (

Xiao 2023). While common in Western markets, ESOPs only became prominent in China after the 2014 Guiding Opinions on the Pilot Implementation of ESOPs by Listed Companies. In mature markets such as the United States and the United Kingdom, long-established employee-ownership systems have been shown to enhance firm resilience and reduce opportunistic behavior (

Blasi et al. 2017), providing an international benchmark for understanding how ESOPs can promote stability in emerging economies.

However, prior studies report mixed evidence on the risk-mitigating effects of ESOPs, partly because many focus on short-term market reactions or treat employee ownership merely as compensation rather than governance. For instance, while (

Li et al. 2019) find a negative link between ESOP announcements and crash risk, other studies show insignificant or reversed results when participation is concentrated among executives or disclosure is weak. These inconsistencies suggest that ESOP effectiveness depends on design, transparency, and institutional context.

Drawing on stewardship theory and stakeholder theory, this study views ESOPs as participatory governance mechanisms. Stewardship theory posits that employee-owners act as stewards who align personal and firm interests through shared trust (

Davis et al. 1997), while stakeholder theory emphasizes that shared ownership broadens accountability and enhances firm stability (

Freeman 2010). Together, these perspectives explain how ESOPs can mitigate managerial opportunism and improve information integrity.

This reform provides a valuable opportunity to investigate whether ESOPs mitigate crash risk in China’s institutional setting, characterized by concentrated ownership, evolving governance, and heterogeneous regional development. Recent studies such as

Quang (

2025) explicitly address how ESOP policy design and transparency affect crash risk, reinforcing the importance of disclosure regimes in ESOP effectiveness. Similarly,

Huang et al. (

2025) bring in non-financial external signals, such as investor sentiment, as predictors of performance in ESOP settings, hinting at broader external moderators relevant to crash risk.

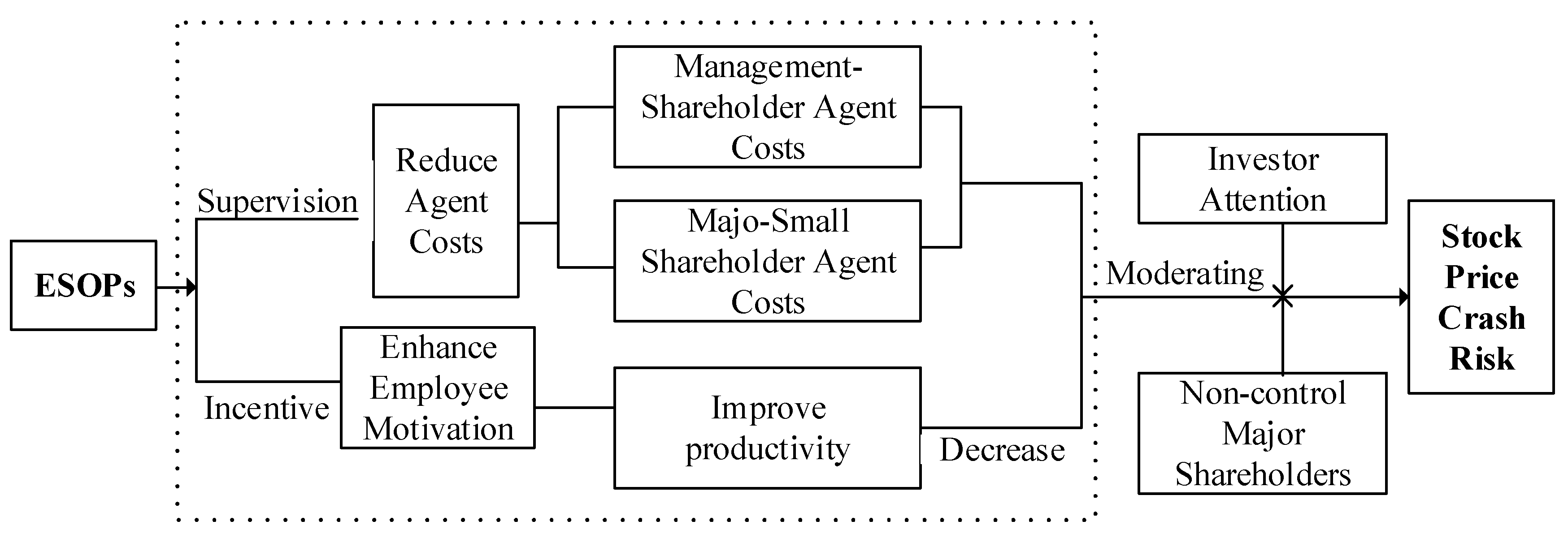

This study examines the relationship between ESOPs and stock price crash risk using panel data on A-share firms from 2014 to 2022. It makes three contributions. First, it introduces employees into the crash-risk discussion by showing that ESOPs are robustly associated with lower crash risk across multiple estimation techniques. Second, it identifies the mechanisms through which ESOPs reduce crash risk, namely by lowering agency costs both between managers and shareholders and between controlling and minority shareholders, and by improving productivity. Third, it demonstrates that ESOP effectiveness depends on external oversight, strengthening when firms face high investor attention and greater exit threats from non-controlling major shareholders. By combining internal and external perspectives, this study not only extends existing literature but also provides practical insights for managers, investors, and policymakers on how ESOPs can enhance market stability in emerging economies. Building on recent advances in the literature on crash risk and governance (e.g.,

Yu et al. 2024;

Quang 2025), this study extends the analysis by focusing specifically on employees as active governance participants and by providing one of the longest observation windows studied to date.

6. Research Conclusions and Management Implications

6.1. Findings

This study examines the role of ESOPs in enhancing market stability through a longitudinal analysis of their impact on stock price crash risk in China’s volatile capital market. Extending the data window to 2014–2022, it provides one of the longest longitudinal analyses to date. While prior studies have focused mainly on announcement effects or short-term informational efficiency (

Yu et al. 2024), this research advances the literature by demonstrating

that implemented ESOPs, not merely announced ones, consistently reduce crash risk through verifiable governance mechanisms. The results are robust across fixed effects, propensity score matching, and instrumental variable tests, with mechanism analysis confirming that ESOPs lower agency costs and enhance productivity. Moreover, the effectiveness of ESOPs is amplified by higher investor attention and stronger exit threats from non-controlling blockholders, and is most pronounced in non-SOEs, eastern regions, and firms with greater employee participation and secondary-market share sourcing. These results differ from findings in some developed markets, where ESOPs have shown weaker or even negative governance effects due to leverage concerns or managerial entrenchment. This comparison suggests that China’s institutional environment, characterized by concentrated ownership and higher information asymmetry, may strengthen the governance role of ESOPs, supporting the external validity of our conclusions. Collectively, these findings reframe employees as active governance agents and expand the theoretical understanding of ESOPs’ stabilizing role in capital markets.

6.2. Managerial Implications

For managers, this study contributes by highlighting that the governance value of ESOPs depends on their substantive design rather than symbolic implementation. While earlier works primarily viewed ESOPs as signaling tools, our findings show that programs with broader employee participation and secondary-market share sourcing exert stronger motivational and monitoring effects that directly reduce crash risk. Managers in non-SOEs and eastern regions, where marketization and institutional support are stronger, can leverage ESOPs to enhance accountability and transparency. By contrast, firms in weaker governance environments should complement ESOPs with timely disclosure and internal control mechanisms to prevent bad-news hoarding. Integrating employee incentives with transparent reporting processes ensures that ESOPs function not just as ownership tools but as strategic governance mechanisms that sustain long-term market stability.

6.3. Investor Implications

For investors, this research enriches the understanding of ESOPs as credible long-term governance signals rather than temporary announcement effects. Firms with well-structured ESOPs, featuring extensive employee involvement and secondary-market share sourcing, display stronger internal oversight and lower downside risk, offering investors a meaningful indicator of governance quality. However, ESOP effectiveness is contingent on context: it is greatest when investor attention is high and when active blockholder oversight reinforces internal incentives. These findings suggest that investors should evaluate ESOPs in conjunction with firm transparency, ownership structure, and information environment, as such interactions determine whether ESOPs genuinely strengthen corporate governance or serve merely as symbolic gestures.

6.4. Policy Implications

For policymakers and regulators, this study extends the literature by identifying design-level and contextual determinants that ensure ESOPs effectively reduce crash risk. While previous studies (

Quang 2025) emphasized transparency, our results demonstrate that meaningful employee participation and secondary-market share sourcing are equally vital for ensuring governance integrity. Regulators should promote broader ESOP adoption through simplified procedures and lower participation barriers while enforcing mechanisms that prevent superficial implementation. Strengthening disclosure standards, protecting non-controlling shareholders, and improving market information transparency can amplify the external oversight that enhances ESOPs’ benefits. These policy directions would transform ESOPs from firm-level incentive instruments into systemic stabilizers that support sustainable market confidence and financial resilience.

6.5. Limitations and Future Research

The main limitation of this study lies in its data coverage, which concludes in 2022. Although this extended window provides a comprehensive view across more than a decade, encompassing various policy shifts, market reforms, and economic cycles, it does not capture potential long-term effects that may emerge beyond 2022 as new regulatory and market dynamics unfold. Future research could build on this foundation by incorporating post-2022 data to examine the durability of the observed relationships under evolving ESOP regulations, corporate governance reforms, and broader capital market transformations.

Second, this study relies on publicly available firm-level data, which restricts the measurement of certain internal governance mechanisms. For example, the dataset cannot fully capture informal monitoring, internal communication flows, or unobservable incentive structures that may influence how ESOPs shape managerial behavior. Future work could integrate survey data, textual analysis, or proprietary internal datasets to provide a more granular understanding of how ESOPs affect information disclosure and bad-news hoarding at the micro level.

Third, although the study controls for a wide range of firm and market characteristics, the empirical design cannot completely rule out all forms of endogeneity. While fixed effects, PSM, and IV methods reduce bias, unobservable time-varying factors may still affect both ESOP adoption and crash risk. Future research may employ natural experiments, regulatory shocks, or difference-in-differences designs to better establish causal identification. Further research might also explore alternative disclosure shocks, undertake cross-market comparisons, or examine the full life cycle of ESOPs from initiation to termination. Given that institutional environments differ markedly across countries, comparative studies could clarify how ownership structures, investor protection, and labor market systems condition the effectiveness of ESOPs. Micro-level studies of information flows within firms could provide valuable insight into how employee ownership discourages bad-news hoarding and strengthens transparency.