Abstract

This study is devoted to investigating the asymmetric effects of geopolitical risks (GPRs) on Vietnam’ exports during the period from January 2010 to December 2024. Using a nonlinear Autoregressive Distributed Lag (NARDL) bounds testing model, the study documented that in the short-run, GPRs have asymmetric effects on Vietnam’s exports. Specifically, negative changes in GPRs have a significantly negative influence on the exports while positive changes in the GPRs have no significant effects on exports. In the long-run, the same effects of GPRs on exports are also found from the NARDL model. Specifically, negative changes in GPRs have a significantly adverse effect on exports, while positive changes in GPRs have no significant influence on exports in the long-run. Moreover, the empirical findings reveal that, in the long-run, the real exchange rate (RER) has a significantly positive impact on exports, suggesting that the depreciation of the VND (Vietnamese Dong) boosts Vietnam’s exports. Finally, the findings obtained from the error correction model show that 34.82 percent of the divergence from the long-run equilibrium caused by a shock in month n will be corrected and adjusted back toward equilibrium in month n + 1.

1. Introduction

Geopolitical risks (GPRs) are defined as the threat, realization, and escalation of adverse events related to wars, terrorism, and tensions among states and political actors that impact the peaceful course of international relations (Caldara and Iacoviello 2022). In addition, according to Hossain et al. (2024), GPRs encompass uncertainties and potential disruptions in international relations, politics, and global security, which can influence economic stability and the operation of commodity and financial markets. In an increasingly integrated global economy, GPRs have emerged as significant factors influencing international trade dynamics. GPRs impact trade flows through several key mechanisms, such as supply chain disruptions, trade barriers, investment flows, and consumer behavior. The effects of GPRs on international trade have received considerable attention from scholars over the last few decades. Most empirical studies have reported that GPRs have negative effects on trade flows between countries (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2018; Gupta et al. 2019; Goswami and Panthamit 2020; Wang et al. 2021; Singh et al. 2023; Kim and Jin 2024; Leitão 2023; Wang et al. 2024; Liu et al. 2024; Liu and Fu 2024; Zehri et al. 2025). It is noted that these studies have assumed that the effects of GPRs on international trade are symmetric, meaning that a decrease in GPRs has the same impact on international trade as an increase in GPRs of the same magnitude. However, the effects of GPRs on international trade could be asymmetric for the following reasons. First, negative geopolitical events tend to have immediate and pronounced adverse effects on international trade, while positive changes may not lead to equivalent benefits, as they often take time to influence trade dynamics. Second, international traders could be risk-averse in the face of geopolitical instability. Therefore, they could react to negative geopolitical events in a different way compared to positive ones (Dada 2021; Truong et al. 2022a).

Over the past few decades, Vietnam’s economy has undergone a transitional period marked by extensive integration into the global economy (Truong et al. 2024). Events like the Russia–Ukraine conflict and the U.S.—China trade war have disrupted Vietnam’s exports through sanctions, logistical bottlenecks, and shifts in global supply chains. In this context, Vietnam’s international trade is very vulnerable to shocks from geopolitical events. Although the effects of GPRs on international trade have been investigated in both developed and developing countries, very little is known about the effects of GPRs on Vietnam’s international trade. Therefore, the objective of the research is to investigate the asymmetric effects of GPRs on Vietnam’ exports.

This study contributes to the literature covering the effects of GPRs on international trade as follows. First, Vietnam, as a transitional economy with extensive integration into the world economy, provides a unique context for examining the effects of GPRs on export performance. The effects of GPRs on exports in this economy can differ from both fully developed economies and less integrated developing ones. In addition, Vietnam’s exports are heavily reliant on foreign investment, component imports, and export processing. Adverse shocks in GPRs can disproportionately disrupt inputs or market access. Second, while most empirical studies have investigated the symmetrical effects of GPRs on international trade (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2018; Gupta et al. 2019; Goswami and Panthamit 2020; Wang et al. 2021; Singh et al. 2023; Kim and Jin 2024; Wang et al. 2024; Liu et al. 2024; Liu and Fu 2024), this study explores the asymmetric effects of GPRs on Vietnam’s exports. Understanding asymmetric effects is crucial for policymakers, as it highlights the need for tailored strategies rather than q one-size-fits-all approach. Third, by using the NARDL bounds test approach to estimate the short-run and long-run relationships, this study provides comprehensive insights into the mechanisms through which GPRs influence export dynamics.

Using the NARDL bounds testing approach, the study found that in the short-run, GPRs have asymmetric effects on Vietnam’s exports. Specifically, negative changes in GPRs have a significant negative influence on exports, while positive changes in GPRs have no significant effects on exports. In the long-run, the same effects of GPRs on exports are also found from the NARDL model. Moreover, the findings obtained from the error correction model show that 34.82 percent of the divergence from the long-run equilibrium caused by a shock this month will be corrected and adjusted back toward equilibrium in the following month.

2. Literature Review

The gravity model of trade is a fundamental framework used to explain and predict international trade flows between countries. According to the gravity model, exports from one country to another are generally determined by the size of their economies and the geographical distance between them. The model can be extended to explain for the effects of GPRs on export performance in several ways. First, GPRs often lead to increased regulatory barriers, tariffs, or trade restrictions, which can hinder export performance (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2018). Second, distance in the gravity model is not only physical but can also represent perceived risk. Countries perceived to have high GPRs can face an increase in effectively distancing countries in terms of their trade relationships, making foreign trade less attractive. In addition, GPRs can disrupt supply chains, increasing costs and complexities for exporters, which can further reduce trade volumes (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2018; Singh et al. 2023). Many empirical studies have utilized the gravity model to examine the effect of geopolitical risks on international trade flows between countries over the last few decades. Specifically, based on the gravity model, Bandyopadhyay et al. (2018) developed a model to determine the effects of terrorism on trade, highlighting that firms in trading nations face varying costs due to both domestic and transnational terrorism. The empirical findings derived from the model revealed that domestic and transnational terrorism have little or no significant effect on the overall trade of primary products, but both forms of terrorism significantly diminish the overall trade of manufactured goods. In addition, both domestic and transnational terrorism negatively impact manufactured imports. Moreover, domestic terrorism decreases manufactured exports and stimulates primary exports, whereas transnational terrorism leads to a decrease in primary exports. Similarly, Gupta et al. (2019) employed a GPR index in a gravity model to investigate the effect of geopolitical risks (GPRs) on trade flows between 164 developing and developed countries from 1985 to 2013. This study found that GPRs have a negative influence on trade flows. Additionally, using a gravity model framework, Goswami and Panthamit (2020) determined the effect of political risk on bilateral trade flows between Thailand and its trading partners for the period from 1984 to 2015. The study reported that increases in political risk substantially diminish bilateral trade flows, highlighting the importance of political stability in promoting foreign trade relationships. In addition, Singh et al. (2023) employed a gravity model to examine the effect of GPRs on trade patterns for seven of the largest economies in Latin America from 2000 to 2020. This study also found a negative effect of GPRs on trade flows between countries, with some countries being more vulnerable than others. Moreover, Kim and Jin (2024) determined the effect of GPRs on South Korea’s international trade for the period from 1991 to 2020. This study documented that an increase in geopolitical tension results in a decrease in South Korea’s international trade. Additionally, the adverse effects of GPRs differ among trading partners, primarily depending on the relative importance of each country. Furthermore, Leitão (2023) explored the effect of country risks on Portuguese exports to 11 main trading partners from 1990 to 2021. This study documented that partner country risk is negatively associated with Portuguese exports, implying that countries with lower risks experience reduced trade costs, which enhances competitiveness among countries.

Recently, some studies have investigated the effect of GPRs on the foreign trade of China, the second-biggest economy in the world. Specifically, Wang et al. (2021) examined the effect of country risk on foreign trade for the Belt and Road (BRI) countries for the period from 2003 to 2018. This study documented that a decrease in country risk results in an increase in bilateral trades between China and these countries. Similarly, Wang et al. (2024) determined the effect of GPRs on China’s bilateral trade flows with its key trading partners, considering the moderating impact of the BRI for the period from 2014 to 2022. The results confirmed that GPRs have negative effects on China’s bilateral trade flows. However, the effects differ between BRI and non-BRI countries. In fact, the negative effect generally holds for non-BRI economies, while China’s economic ties with BRI countries tend to strengthen in the face of rising GPRs. Moreover, Liu et al. (2024) investigated the impact of GPRs on China’s exports and its specific internal mechanisms during the period from 2003 to 2021. The study reported that GPRs have a significantly negative effect on China’s exports. In particular, the researchers found that China’s outward foreign direct investment plays a crucial role in alleviating the negative impact of GPRs on exports. Additionally, the findings revealed that GPRs have a more pronounced impact on China’s exports in non-BRI economies compared to BRI members. Moreover, Liu and Fu (2024) explored the effect of GPRs on China’s agricultural exports from 1995 to 2020. The empirical results show that China’s agricultural exports decline when its trading partners face GPRs, and the agricultural land of trading partners plays a key role in reducing the negative impact of GPRs on China’s agricultural exports. Similar to the findings of Liu et al. (2024), this study confirmed that the effect of GPRs on China’s agricultural exports is stronger in non-BRI countries than in BRI economies.

Additionally, other studies have examined the effect of GPRs on energy trade. Li et al. (2021) discovered the effect of GPRs on energy trade of 17 emerging economies during the period from 2000 to 2020. Based on empirical evidence, the authors asserted that GPRs have a negative influence on energy trade, with the effect on exports being more pronounced than on imports. Recently, Zehri et al. (2025) explored how GPRs impact energy trade differently in 55 emerging and advanced economies for the period from 1990 to 2023. The study documented that GPRs generally hinder energy trade, with long-term effects outweighing temporary shocks. However, emerging economies tend to be more vulnerable to GPRs, experiencing greater disruptions in energy trade compared to their advanced counterparts due to their significant dependence on energy exports and weaker institutional capacity.

From a different perspective, Atacan and Açık (2023) examined the relationship between GPRs and international trade, proxied by container volumes. Employing a data set of 15 countries from 2000 to 2020, the researchers discovered that positive shocks in GPRs lead to negative shocks in container volumes. Using data from 119 countries for the period from 1985 to 2022, Yan and Piao (2025) investigated the effect of GPRs on national trade openness. The empirical findings revealed that GPRs have a significantly negative effect on trade openness. In addition, enhanced fiscal freedom and stable fiscal conditions are shown to effectively mitigate this negative effect, emphasizing the importance of strong fiscal institutions in bolstering national resilience to external shocks. Moreover, the results indicated that the detrimental impact of GPRs is more significant in countries with lower government integrity and weaker monetary freedom.

In summary, the reviewed literature generally supports the notion that GPRs adversely affect international trade. Key findings indicate that increased geopolitical tensions lead to disruptions in trade flows, altering established trade patterns. However, there are discrepancies regarding the extent of these effects across different countries and sectors. Vietnam is a highly export-driven economy, with key export items including electronics, machinery, textiles, and agricultural products. Its major trading partners—such as the United States, China, and South Korea—account for a substantial share of export revenue, exposing the country to geopolitical tensions among global powers. Additionally, the dominance of foreign-invested enterprises in export production highlights Vietnam’s deep integration into global supply chains, making it particularly sensitive to external shocks. These characteristics underscore the relevance of examining how geopolitical risks asymmetrically impact Vietnam’s export performance. Based on the reviewed evidence, it is hypothesized that GPRs have a negative effect on Vietnam’s exports.

3. Data and Research Methodology

3.1. Data Sources

The data used in the study consist of monthly series for the GPR Index, Vietnam’s exports, real exchange rate (RER), and industrial production index (IPI) covering the period from January 2010 to December 2024. The data are obtained from various reliable sources, namely the Geopolitical Risk Index Report, the General Statistics Office (GSO), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It is noted that this study utilizes the GPR index proposed by Caldara and Iacoviello (2022). Specifically, the data sources are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data sources of the study.

3.2. Research Methodology

To investigate the asymmetric effects of GPRs on Vietnam’s export, the following baseline regression model is employed:

where

- -

- LNEX is the natural logarithm of Vietnam’s exports;

- -

- is the partial sum of positive changes in ln(GPR);

- -

- is the partial sum of negative changes in ln(GPR);

- -

- LNRER is the natural logarithm of the real exchange rate of USD/VND. The real exchange rate (RER) is computed by Equation (2) as follows:

where

- NER is the nominal exchange rate of USD/VND.

- is Vietnam’s consumer price index.

- is the United States’s consumer price index.

- LNIPI is the natural logarithm of Vietnam’s industrial production index.

To examine the short-run and long-run asymmetric effects of GPRs on Vietnam’s exports, this research applies the nonlinear Autoregressive Distributed Lag (NARDL) bounds testing approach proposed by Shin et al. (2014), which extends the ARDL method proposed by Pesaran et al. (2001). In this approach, the ln(GPR) is decomposed into the partial sums of negative and positive changes series. This research utilizes the NARDL model because the model has serveral main advantages over other alternative cointegration methods. First, a key advantage of the model compared to other cointegration methods is that it allows for the derivation of an error correction model (ECM) from the NARDL model, enabling the simultaneous estimation of both short-run and long-run asymmetric effects of independent variables on the dependent variable (Bahmani-Oskooee and Gelan 2012; Bahmani-Oskooee et al. 2018; Truong et al. 2022b; Xu et al. 2022;Truong et al. 2024). Second, all variables in the NARDL model are not required to have the same order of integration;it only requires that the integration order of all variables in the model is less than 2 (Arize et al. 2018; Bahmani-Oskooee and Arize 2019;Chandio et al. 2019; Truong et al. 2022b; Xu et al. 2022; Truong et al. 2024). However, this technique has some disadvantages. First, since this approach decomposes independent variable(s) into positive and negative changes separately, it requires a relatively large sample size to reliably estimate asymmetric effects compared to the ARDL (Li et al. 2025; Khurshid et al. 2025). Second, this approach cannot be used for models in which any of the variables are integrated of order two (Truong et al. 2024).

As mentioned previously, the NARDL bounds test for cointegration requires all studied variables in the model to be either I(0) or I(1). Therefore, unit root tests should be performed prior to conducting the NARDL bounds test. In this study, the augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and Phillips–Perron tests are utilized to determine the stationarity of the variables in the model.

Before estimating the short-run and long-run asymmetric effects of GPRs on exports, a cointegration test should be conducted as a required condition. In this study, the NARDL bounds test for cointegration between variables in the model is represented by the following equation:

where

- -

- Δ is the first difference in the variables;

- -

- k1, k2, k3, k4, k5 represent the optimal number of lags for the variables under consideration, as determined by the Akaike information criterion (AIC) technique.

The null hypothesis of the bounds test estimated by Equation (3) is that there is no cointegration among the variables in the long-run. If the null hypothesis is rejected, it can be concluded that a long-run relationship exists between the variables in the model. In this case, the short-run and long-run asymmetric effects of the GPR on exports are estimated by Equations (4) and (5), respectively.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

Based on the data collected, descriptive statistics of the sample are computed and summarized in Table 2. Table 2 indicates that the average of Vietnam’s exports during the studied period is USD 18,765.5 million, ranging from USD 3717.3 million to USD 38,085.6 million. In addition, it is shown in Table 2 that the GPR Index had highly fluctuated over the sample period. Specifically, the average of GPR Index is 91.5 points, while the lowest score and highest score are 28.5 and 251.0 points, respectively. Moreover, it is found in Table 2 that the mean of real exchange rate of USD/VND (RER) is 28,951. The real exchange rate (RER) has increased significantly during the studied period, meaning that the Vietnamese Dong had depreciated over that period. In addition, Table 2 reveals that the average of IPI for the period from January 2010 to December 2024 is 94.3 points, ranging from 57.0 points to 124.7 points.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the sample.

4.2. Results of the Unit Root Tests

As previously noted, this study utilizes the augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and Phillips–Perron tests to determine whether all variables in the model meet the stationarity condition required for the ARDL bounds test. These tests are conducted for both constant-only and constant-with-time-trend cases. The results of the tests are presented in Table 3. Specifically, the results derived from the ADF indicate that the LNEX, , , and LNRER variables are I(1), whereas the LNIPI variable is I(0). In addition, the results of the Phillips–Perron test confirm that the LNEX, , and variables are I(1), while the LNRER variables are I(0). The results indicate that all studied variables meet the condition for conducting the ARDL bounds test (Bahmani-Oskooee and Arize 2019; Truong et al. 2022b; Xu et al. 2022; Truong et al. 2024).

Table 3.

Results of the unit root tests.

4.3. Results of the ARDL Bounds Test

The study employs the bounds test developed by Pesaran et al. (2001) to determine the long-run relationship among the studied variables. Based on the AIC technique, the best model for the bounds test is ARDL (3,0,0,3,4). The results presented in Table 4 indicate that the null hypothesis of no cointegration in the long-run among the variables in the model is rejected at the one percent significance level. This finding confirms the existence of a long-run equilibrium relationship between Vietnam’s exports and the independent variables.

Table 4.

Results of the bounds test.

4.4. Short-Run and Long-Run Influences of GPRs on Vietnam’s Exports

Given the evidence of a long-run relationship among the variables in the model, the short-run and long-run asymmetric effects of GPRs on Vietnam’s exports are determined by using the NARDL (3,0,0,3,4) model. The empirical findings shown in Table 5 reveal that in the short-run, GPRs have asymmetric effects on Vietnam’s exports, suggesting that positive and negative changes in GPRs have a distinct effect on Vietnam’s exports. Negative changes in GPRs have a significantly negative impact on exports at the ten percent level. Specifically, a one percent increase in negative changes in GPRs immediately results in a 0.0234 percent decrease in Vietnam’s exports. However, positive changes in GPRs have no significant impact on exports. In addition, the findings shown in Table 5 reveal that the real exchange rate (RER) has a positive influence on exports at the five percent significance level for the one-month lag, suggesting that the depreciation of VND (Vietnamese Dong) boosts Vietnam’s exports. Specifically, a one percent depreciation of the VND from the previous month results in a 2.3197 percent increase in exports in the current month. Moreover, it is observed from Table 4 that the IPI has a significantly positive effect on exports in the short-run at the five percent level. Specifically, a one percent increase in the IPI leads to a 1.1798% contemporaneous increase in exports and a 0.1092 percent increase in exports for the three-month lag. Moreover, the coefficient of the error correction term is −0.3482, suggesting that 34.82 percent of the divergence from the long-run equilibrium caused by a shock this month will be corrected and adjusted back toward equilibrium in the following month.

Table 5.

Estimated short-run and long-run coefficients using the NARDL approach.

Similarly, in the long-run, the estimated results presented in Panel B of Table 5 indicate that negative changes in GPRs have a negative impact on Vietnam’s exports at the ten percent significance level. A one percent increase in negative changes in GPRs is associated with 0.0672% decrease in exports. However, the results confirm that in the long-run, positive changes in GPRs have no impact on exports. In addition, the empirical findings reveal that, in the long-run, the RER has a significantly positive impact on exports. Specifically, a one percent depreciation of the VND leads to a 0.5748 percent increase in Vietnam’s exports. However, there is no evidence to be found about thelong-run effect of IPI on exports.

Generally, the study finds that GPRs have asymmetric effects on Vietnam’s exports both in the short-run and the long-run. Specifically, negative changes in GPRs have a significantly negative effect on exports, while positive changes in GPRs have no significant impact on exports. This evidence partially aligns with the previous findings of Bandyopadhyay et al. (2018); Gupta et al. (2019); Goswami and Panthamit (2020); Singh et al. (2023); Kim and Jin (2024); Leitão (2023); Wang et al. (2024); Liu et al. (2024); and Liu and Fu (2024), who found that GPRs have a significantly negative impact on trade flows between countries. In addition, previous studies, including those by Gupta et al. (2019); Goswami and Panthamit (2020); and Kim and Jin (2024), highlighted that export-oriented economies are particularly vulnerable to GPRs. The findings of our study support this view, demonstrating that Vietnam’s exports are significantly influenced by GPRs. However, these studies are based on the assumption that the effect of GPRs is symmetric, meaning that positive and negative changes in GPRs have the same effect on trade flows. Contrary to these findings, our findings confirm that only negative changes in GPRs negatively impact Vietnam’s exports, while positive changes in GPRs have no impact on exports. The asymmetric effects of GPRs on Vietnam’s exports could be explained by several reasons. First, increased negative changes in GPRs can significantly disrupt supply chains and increase trade costs, leading to a decline in exports (Jawadi et al. 2024; Hou et al. 2024; Yan and Piao 2025). This is especially relevant for Vietnam, that is heavily dependent on specific trade partners. In addition, an increase in negative changes in GPRs can lead to tariffs and other trade barriers, which negatively affects export volumes by driving up the prices of goods (Singh et al. 2023; Shen and Yang 2024; Yan and Piao 2025). Although positive changes in GPRs can create favorable conditions for boosting exports, their actual effects on Vietnam’s exports are less significant compared to the negative impact of adverse events due to various factors. Specifically, positive changes in GPRs could not lead to immediate increases in exports as businesses need time to adjust strategies, expand operations, or explore new markets. In addition, since Vietnam’s exports are predominantly agricultural and labor-intensive products, even with positive changes in GPRs, the potential for increasing exports is also limited by production capacity.

This study extends the existing literature on the impact of GPRs on international trade, particularly in transitional economies. While most empirical studies have documented that GPRs have symmetric effects on international trade, meaning that a decrease in GPRs has the same impact on international trade as an increase in GPRs with the same magnitude, this study finds asymmetric effects of GPRs on export performance. Specifically, negative changes in GPRs have a significantly negative impact, while positive changes in GPRs have no significant impact on the exports. In addition, the findings underscore the importance of contextual factors, such as market structure and economic resilience in shaping the effects of GPRs. This enriches the theoretical discourse by suggesting that the impact of GPRs cannot be fully understood without considering the economic context of the affected country.

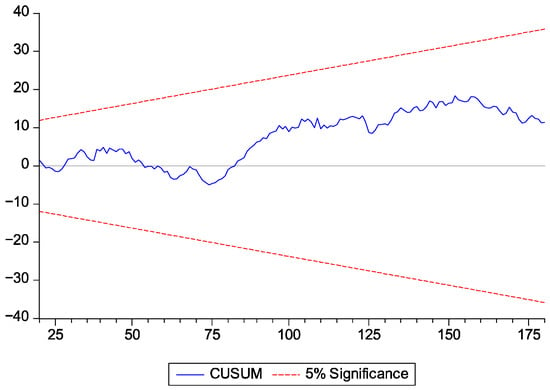

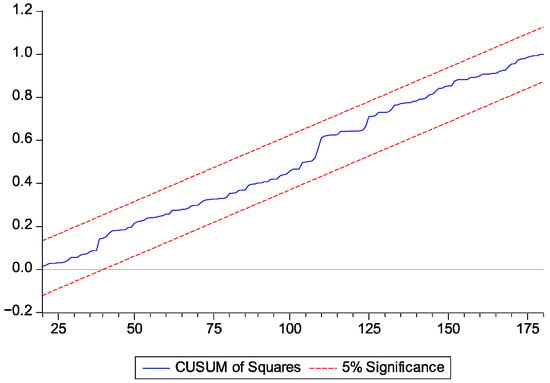

4.5. Diagnostic and Structural Stability Tests

The results of Breusch–Godfrey test shown in Table 6 reveal that the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation in the model cannot be rejected at the significance level of 5%, suggesting that there is no autocorrelation among the residuals. Moreover, the results of the Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey test indicate that the residuals of the model are homoscedastic. Furthermore, Figure 1 and Figure 2 show that the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ plots remain within the critical bounds at the five percent significance level. These results ensure the reliability and validity of the estimated results.

Table 6.

Results of Breusch–Godfrey and ARCH tests.

Figure 1.

Results of CUSUM test.

Figure 2.

Results of CUSUMSQ test.

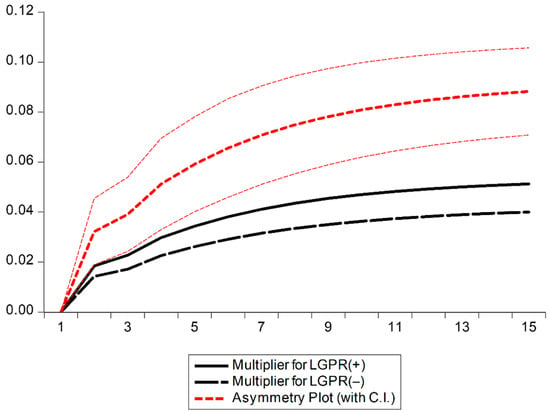

4.6. Cumulative Dynamic Multiplier

The dynamic multiplier graph for GPRs (Figure 3) presents the impact of positive and negative shocks in GPRs on exports over time. The black solid line in the figure reflects the response of exports to positive shocks in GPRs (an increase in GPRs). The initial increase in GPRs leads to a rise in exports, and the impact tends to increase in the long-term. In addition, the black dashed line indicates the effect of negative changes in GPRs (a decrease in GPRs) on exports. Negative shocks to GPRs also lead to an increase in exports, but the impact is slightly smaller than the effect of positive shocks. Moreover, the red dashed line in Figure 3 highlights the asymmetry between positive and negative changes in GPRs. As the zero line is not located between the lower and upper bounds, the asymmetric effects of GPRs on exports are significant at the 5% level.

Figure 3.

NARDL dynamic multiplier graph for GPRs.

5. Conclusions

While most empirical studies have investigated the systematic effects of GPRs on trade flows between countries, this research examines asymmetrically short-run and long-run effects of GPRs on Vietnam’s exports. Using the NARDL bounds testing model, this study found that in both the short-run and the long-run, GPRs have asymmetric effects on exports. Specifically, negative changes in GPRs have a significantly negative impact on Vietnam’s exports, while positive changes in GPRs have no significant impact on exports. This evidence is partially in line with the findings of Bandyopadhyay et al. (2018); Gupta et al. (2019); Goswami and Panthamit (2020); Singh et al. (2023); Kim and Jin (2024); Leitão (2023); Wang et al. (2024); Liu et al. (2024); and Liu and Fu (2024), who found that GPRs have symmetrically adverse effects on trade flows between countries. Moreover, the empirical results revealed that the real exchange rate has a significantly positive influence on Vietnam’s exports, meaning that the depreciation of the Vietnamese Dong enhances Vietnam’s exports.

Based on the empirical findings, several policy implications can be suggested for Vietnamese policymakers to mitigate the adverse effect of GPRs on exports. First, the government should promoteexisting free trade agreements with other countries so that businesses can take advantage of opportunities to mitigate the negative impacts of GPRs. In addition, the government should actively pursue and negotiate new free trade agreements to expand market access and reduce the negative effects of GPRs on Vietnam’s exports. These new agreements should ideally be with countries that have not exhibited instability in terms of GPRs. Second, the government should enhance diplomatic ties with a diverse range of countries to diversify markets for exporters. This can help secure stable export markets and mitigate risks. Finally, the government should establish robust monitoring and early warning systems to regularly assess GPRs in trading partner countries, facilitating timely adjustments to trade strategies.

While this study has enriched the literature on the impact of GPRs on exports in a transition economy, it still has several limitations that need to be addressed in future studies. First, the effect of GPRs can vary significantly across different sectors, but this study does not explore these sector-specific variations, which could offer more nuanced insights. Second, the study does not account for other external factors, such as global economic conditions or pandemics, that could interact with GPRs and influence exports.These limitations could be interesting topics for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D.T. and D.T.N.; methodology, L.D.T. and N.T.N.; software, L.D.T. and N.T.N.; validation, D.T.N.; formal analysis, L.D.T. and D.T.N.; investigation, N.T.N.; resources, N.T.N.; data curation, D.T.N.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.T.; writing—review and editing, D.T.N. and N.T.N.; visualization, L.D.T.; project administration, L.D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arize, Augustine, Ebere Ume Kalu, and Nelson N. Nkwor. 2018. Banks versus markets: Do they compete, complement or co-evolve in the Nigerian financial system? An ARDL approach. Research in International Business and Finance 45: 427–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atacan, Can, and Abdullah Açık. 2023. Impact of geopolitical risk on international trade: Evidence from container throughputs. Transactions on Maritime Science 12: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, and Abera Gelan. 2012. Is there J-curve effect in Africa? International Review of Applied Economics 26: 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, and Augustine C. Arize. 2019. U.S.-Africa trade balance and the J-curve: An asymmetry analysis. The International Trade Journal 33: 322–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, Niloy Bose, and Yun Zhang. 2018. Asymmetric cointegration, nonlinear ARDL and the J-curve: A bilateral analysis of China and its 21 trading partners. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 54: 3131–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, Subhayu, Todd Sandler, and Javed Younas. 2018. Trade and terrorism: A disaggregated approach. Journal of Peace Research 55: 656–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldara, Dario, and Matteo Iacoviello. 2022. Measuring geopolitical risk. American Economic Review 112: 1194–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandio, Abbas Ali, Yuansheng Jiang, and Abdul Rehman. 2019. Using the ARDL-ECM approach to investigate the nexus between support price and wheat production: An empirical evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies 26: 139–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, James Temitope. 2021. Asymmetric effect of exchange rate volatility on trade in SubSaharan African countries. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences 37: 149–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, Gour Gobinda, and Nisit Panthamit. 2020. Does political risk lower bilateral trade flow? A gravity panel framework for Thailand vis-à-vis her trading partners. International Journal of Emerging Markets 17: 600–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Rangan, Giray Gozgor, Huseyin Kaya, and Ender Demir. 2019. Effects of geopolitical risks on trade flows: Evidence from the gravity model. Eurasian Economic Review 9: 515–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Ashrafee T., Abdullah-Al Masum, and Samir Saadi. 2024. The impact of geopolitical risks on foreign exchange markets: Evidence from the Russia–Ukraine war. Finance Research Letters 59: 104750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Yulin, Wenjun Xue, and Xin Zhang. 2024. The Impact of geopolitical risk on trade costs. Global Economic Review 53: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawadi, Fredj, Philippe Rozin, Yacouba Gnegne, and Abdoulkarim Idi Cheffou. 2024. Geopolitical risks and business fluctuations in Europe: A sectorial analysis. European Journal of Political Economy 85: 102585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, Nabila, Nabila Akram, and Gulnaz Hameed. 2025. Asymmetric variations in economic globalization, CO2 emissions, oil prices, and economic growth: A nonlinear analysis for policy empirics. Environment, Development and Sustainability 27: 11419–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Chi Yeol, and Hyungsuk Jin. 2024. Does geopolitical risk affect bilateral trade? Evidence from South Korea. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 29: 1834–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, Nuno Carlos. 2023. The impact of geopolitical risk on Portuguese exports. Economies 11: 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Cai, Hazrat Hassan, and Talat Mehmood Khan. 2025. “How effectively does the NARDL approach analyze and interpret the modern dynamics of entrepreneurship, financial inclusion, and environmental sustainability?” A new look at China’s economy. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 27: 3927–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Fen, Cunyi Yang, Zhenghui Li, and Pierre Failler. 2021. Does geopolitics have an impact on energy trade? Empirical research on emerging countries. Sustainability 13: 5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Ke, and Qiang Fu. 2024. Does geopolitical risk affect agricultural exports? Chinese evidence from the perspective of agricultural land. Land 13: 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Ke, Qiang Fu, Qing Ma, and Xiang Ren. 2024. Does geopolitical risk affect exports? Evidence from China. Economic Analysis and Policy 81: 1558–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. Hashem, Yongcheol Shin, and Richard J. Smith. 2001. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics 16: 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Meng, and Mengjia Yang. 2024. Are geopolitical risks fuelling trade protectionism? Defence and Peace Economics 35: 1120–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Yongcheol, Byungchul Yu, and Matthew Greenwood-Nimmo. 2014. Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ARDL framework. In Festschrift in Honor of Peter Schmidt: Econometric Methods and Applications. Edited by Robin C. Sickles and William C. Horrace. New York: Springer, pp. 281–314. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Vikkram, Henrique Correa da Cunha, and Shivanie Mangal. 2023. Do geopolitical risks impact trade patterns in Latin America? Defence and Peace Economics 35: 1102–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Loc Dong, Ha Hoang Ngoc Le, and Dut Van Vo. 2022a. The asymmetric effects of exchange rate volatility on international trade in a transition economy: The case of Vietnam. Bulletin of Monetary Economics and Banking 25: 203–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Loc Dong, H. Swint Friday, and Anh Thi Kim Nguyen. 2022b. The effects of index futures trading volume on spot market volatility in a frontier market: Evidence from Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange. Risks 10: 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Loc Dong, H. Swint Friday, and Tan Duy Pham. 2024. The effects of geopolitical risk on foreign direct investment in a transition economy: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 17: 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Chao, Xiaoxia Yao, and Chi Yeol Kim. 2024. Is a friend in need a friend indeed? Geopolitical risk, international trade of China, and Belt & Road Initiative. Applied Economics Letters 32: 1021–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Zhengwen, Yunxiao Zong, Yuwan Dan, and Shi-Jie Jiang. 2021. Country risk and international trade: Evidence from the China-B&R countries. Applied Economics Letters 28: 1784–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Jia, Mohsen Bahmani-Oskooee, and Huseyin Karamelikli. 2022. On the asymmetric effects of exchange rate uncertainty on China’s bilateral trade with its major partners. Economic Analysis and Policy 73: 653–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Xianglin, and Longguo Piao. 2025. The effect of global geopolitical risks on trade openness. International Review of Economics and Finance 102: 104366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehri, Chokri, Abdullah Alsadan, and Latifa Saleh ben Ammar. 2025. Asymmetric impacts of geopolitical risks on energy Trade: Divergent vulnerabilities in emerging vs. advanced economies. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries 32: e00427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).