Abstract

Background/Objectives: Fetal growth restriction (FGR), formerly known as intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), is defined as a fetus’ failure to reach its genetically predetermined growth potential. FGR has also been implicated in the development of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), though strong supporting literature has yet to be published. This study aims to review the existing associations between FGR and autism spectrum disorder or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder as studied in relevant literature, as well as the mechanisms that provide explanation of that association. Methods: We used a combination of the terms ‘Autism spectrum disorder’ OR ‘Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder’ OR ‘neurodevelopmental disorders’ AND ‘intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR)’ OR ‘fetal growth restriction (FGR)’ in an electronic search of PubMed/MEDLINE and Scopus databases. Results: After evaluating the existing literature, we found only a few studies assessed the risk of developing ASD or ADHD in IUGR/FGR children. Neurodevelopmental disorders have generally been linked to very low birth weight, small for gestational age neonates (SGA), prematurity, somatic mutations, and intrauterine caffeine and alcohol exposure. While available evidence supports the notion that IUGR/FGR is related to cognitive impairment and behavioural disorders, the association with ASD or ADHD remains elusive due to the marked variability in the reported outcomes. Few studies have reported a respective higher risk for autism spectrum disorders, yet most of them have failed to identify a statistically significant correlation. Conclusions: While autism spectrum disorders and attention deficiency disorder have been generally associated with FGR children, the existing body of literature offers limited evidence to support this theory.

1. Introduction

Fetal Growth Restriction (FGR), formerly known as intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), is defined as a fetus’ failure to reach its genetically predetermined growth potential, usually identified as (a) an estimated fetal weight or abdominal circumference below the 3rd percentile; or (b) an estimated fetal weight or abdominal circumference below the 10th percentile in combination with abnormal fetal Doppler velocimetry; or (c) a significant decline in fetal growth on serial assessments [1]. FGR is typically diagnosed via ultrasound, particularly when fetal biometric parameters fall below expected norms [1]. The condition affects approximately 5–10% of pregnancies and has a multifactorial etiology, including fetal, maternal, and uteroplacental causes [2,3]. It can be symmetrical or asymmetrical, late or early (32 weeks of gestation), and it predisposes to severe perinatal morbidity and possibly mortality. On the contrary, the term small for gestational age (SGA) does not refer completely to FGR neonates, as SGA refers to neonates born with a birthweight less than the 10th percentile. Those two conditions—which are similar, but not identical—have been associated with severe impairment of fetal brain development, consequently leading to neurobehavioral, motor, and cognitive dysfunction, among other conditions [1,4].

More specifically, FGR has also been implicated in the development of two common neurodevelopmental disorders—autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). ASD is characterized by communication difficulties, impaired social interaction, and repetitive or unusual behaviour, and has an estimated prevalence up to 1% [5,6]. In addition, ADHD is a condition defined by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, with approximately 4% worldwide prevalence and unclear etiology [7].

FGR is believed to be associated with neurodevelopmental disorders due to mechanisms of suboptimal growth, hypoxic stress, brain sparing, etc. However, the association is yet to be confirmed because of a paucity of data in the existing literature and failure to prove the exact mechanisms and etiology behind this remark; furthermore, FGR overlaps with several maternal–fetal conditions such as pre-eclampsia, prematurity, low birth weight, etc., that are also thought to raise the probability of impaired neurodevelopment in neonates [8,9]. This study aims to review the existing associations between FGR and autism spectrum disorder or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder as studied in the relevant literature, as well as the mechanisms that provide explanation of that association.

For the purposes of this article, and since most of the available literature was published before the 2016 consensus on FGR, both terms (FGR and IUGR) will be used interchangeably.

2. Materials and Methods

For the aforementioned purposes, a narrative review was conducted using studies of various complexity and design. We conducted a systematic search of the literature to identify eligible studies elaborating on the relation between FGR and autism or attention-deficit disorder using the following terms for PubMed: (All terms) (“Autism spectrum disorder” OR neurodevelopmental OR attention-deficit) AND (“Fetal growth restriction” OR IUGR). Filters: 2005–2025. Results: 699. For Scopus, the following search terms were used: (TITLE-ABS-KEY) ((“Autism spectrum disorder” OR autism OR neurodevelopmental OR attention-deficit) AND (“Fetal growth restriction” OR IUGR). Filters: 2005–2025. Results: 37).

An electronic search of PubMed/MEDLINE and Scopus was carried out between 1 July 2025 and 14 August 2025, reviewing all relevant literature published in the English language regarding intrauterine growth retardation and its association with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. We used a combination of the terms ‘Autism spectrum disorder’ OR ‘Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder’ OR ‘neurodevelopmental disorders’ AND ‘intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR)’ OR ‘fetal growth restriction (FGR)’. Both original articles and review articles that involved patients with FGR/IUGR and an autism spectrum diagnosis or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnosis, without a publication frame, were deemed eligible. Twin studies and studies conducted in animals were excluded. All articles that studied the effect of a substance, e.g., alcohol, on neurodevelopmental disorders were also excluded. The article selection procedure and data extraction were assessed by two independent authors. Any areas of disagreement were resolved on an individual basis through a case-by-case discussion.

3. Results and Discussion

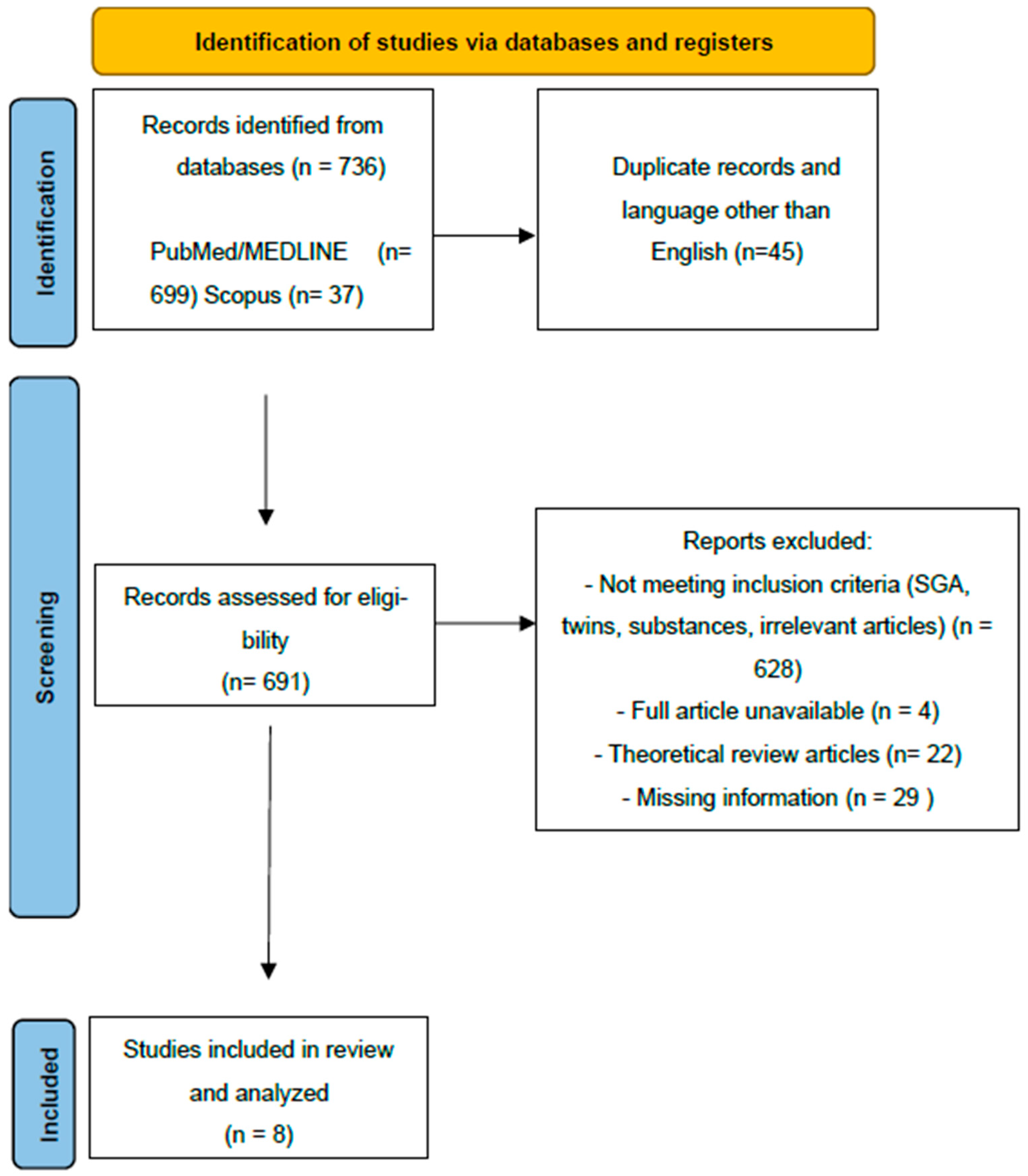

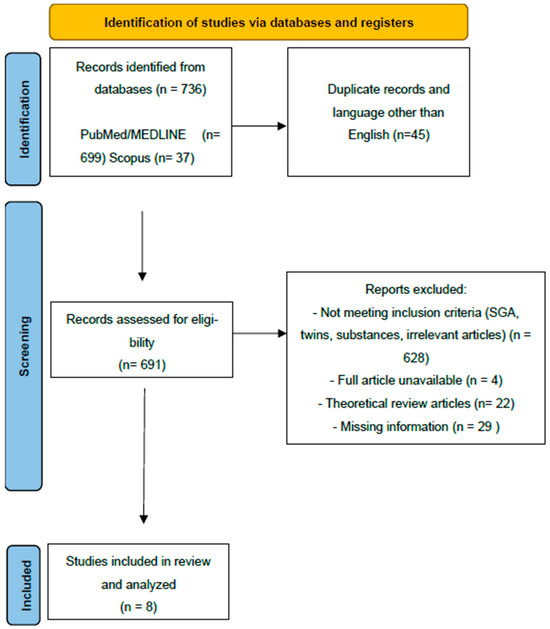

The study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Prisma flow chart.

Briefly, 736 articles were identified through a systematic search of the PubMed/MEDLINE and Scopus databases. (Figure 1). After the removal of duplicates and all studies in languages other than English, 691 articles were screened for potential inclusion. The articles excluded and the reasons for exclusion are also presented. Ultimately, eight articles were included and underwent further analysis in this review article. All articles screened by the research team (A.K. and M.P.) were put through Covidence, where further abstract and full-text screening took place, until the final list of included articles was agreed upon by all authors. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Eligible studies about FGR’s association with ASD or ADHD.

Fetal growth restriction, formerly known as intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), is defined as a fetus’ failure to reach its genetically determined growth potential. It has an incidence of up to 9% of pregnancies in high-income countries and rates can increase dramatically in low-income countries and reach almost 30%. The factors associated with FGR are fetal, maternal, and placental. Overall, the most common cause is placental insufficiency and abnormalities in the placental blood flow, resulting in limited oxygen transfer and nutrition for the fetus. FGR is typically diagnosed via ultrasound, particularly when fetal biometric parameters fall below expected norms. It can be symmetrical or asymmetrical, late or early (32 weeks of gestation), and it is thought to be associated with perinatal morbidity and mortality [1].

On the other hand, SGA refers to infants that are born with a birthweight less than the 10th percentile, likely because they are genetically small. In 2016, a consensus of FGR definition was reached and included placental dysfunction parameters and biometric measures, emphasizing that FGR refers to infants with suboptimal growth due to pathological changes during pregnancy. Those conditions, which have previously been mistaken for one another, are thought to be associated with neurodevelopment disorders, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [1,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

Autistic spectrum disorder is characterized by impaired social interactions, communication difficulties, and stereotypical behavioural patterns, affecting up to 1% of the global population [16]. One person per one thousand births will be diagnosed with autism disorder at some point in their lifetime [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. While the etiology is thought to be genetic, environmental factors associated with autism include exposure to rubella, thalidomide, or valproate during pregnancy [16]. Until today, there has been no specific etiology for ASD. Proposed maternal conditions and perinatal factors include threatened abortion, maternal diabetes, pre-eclampsia, preterm birth, low birth weight, intrauterine growth retardation, and low Apgar scores [5].

Simultaneously, up to 75% of children with ASD are also diagnosed with intellectual disability. ASD and ID are frequently combined, but also share some manifestations. Children with these conditions present with developmental delay, abnormal verbal communication, and social difficulties.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Its worldwide prevalence is approximately 3.4–7.2%. Its etiology is still unknown [18].

FGR, as mentioned before, has shown increased occurrence in tandem with neurodevelopmental disorders. Suboptimal in utero growth is thought to play an important role in the development of the cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems of the developing fetus, which continues after birth and into adulthood. Hypoxic stress can elicit many physiological responses to the developing fetus, including brain sparing, a response which aims to preserve the development of vital organs [19]. The brain sparing response includes redistribution of blood flow to essential vascular beds, e.g., the brain, heart, and adrenal glands, and decreased blood flow to non-essential vascular beds, e.g., the liver and skeletal muscle. The consequences for the fetus include, in addition to many vascular and endothelial changes, decreased head circumference and total brain weight, decreased grey and white matter volume and cell number, loss of cerebral vasoreactivity, impaired neuro-vascular units, and regional perfusion alteration [19]. A brain sparing diagnosis is established with the use of a Doppler ultrasound to visualize the flow through the middle cerebral artery (MCA) and a pulsatility index calculation which is indicative of downstream vascular resistance [20].

Initially, when brain sparing begins, blood flow preferentially supplies the frontal brain region. Later on, perfusion is shifted towards the basal ganglia, where nuclei responsible for motor control, learning, behaviours, and emotions are located.

As mentioned above, the fetus responds to hypoxia with brain sparing, i.e., vasodilation of the cerebral vasculature, in order to protect and preserve brain growth. However, it has been shown that brain sparing may lead to cerebrovascular remodelling, loss of cerebral vasoreactivity, and neurodevelopment dysfunction [21,22].

After an evaluation of existing literature, it was found that only a few studies assessed the risk of developing ASD or ADHD in FGR children.

In general, neurodevelopmental disorders have been associated with very low birth weight, SGA neonates, prematurity, somatic mutations, intrauterine caffeine and alcohol exposure, and SGA neonates, a particular population commonly mistaken as FGR neonates [23]. Variability in definitions and lack of biological mechanistic data and studies only conducted in animal models are confusing factors and weaken association strength [6,14,15,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

While many studies examine, either retrospectively or prospectively, the neurodevelopment dysfunctions of FGR children, the results are most often focused on IQ measures or, in general, on the motor, language, and speech function of children, most of them without including a diagnosis of a certain neurodevelopmental disorder. Authors have highlighted the heterogeneity of primary outcomes and assessment tools and variability in FGR definition and the lack of a control population [31]. To our knowledge, this is the first review article examining the association between autism spectrum disorders and ADHD with FGR children.

In 1988, Matilainen et al. compared IUGR children with appropriate-for-gestational-age and full-term children by measuring their general intelligence quotient (IQ) and deficiencies in intellectual function such as perceptuomotor functions, language, and social maturity at preschool. IUGR children were found to have lower IQ scores than full-term controls and were more commonly diagnosed with developmental disabilities [32].

Inappropriate intrauterine growth was considered to be associated with intellectual disability in a retrospective study examining 2.277 Caucasian children and 348 Aboriginal children in Western Australia. In this study, infants with excessive intrauterine growth (POBW > 124 percentile) were more likely to be diagnosed with intellectual disability associated with autism spectrum disorders (odds ratio 2.36 95% CI (0.93–6.03) [33].

In a retrospective univariate and multivariate analysis of 383.153 births in Western Australia between 1984 and 1999, maternal conditions, including a poor intrauterine environment, were associated with elevated risks of intellectual disability and autism disorders with ID were associated with threatened abortion before 20 weeks of gestation and poor fetal growth [5].

Twin studies like the Roots of Autism and ADHD Twin Study in Sweden (RATSS) support birth weight effects beyond a shared genetic predisposition. The findings of that recent study suggest an association between low birth weight and neurodevelopmental conditions, but they also acknowledge the importance of genetics because the associations observed were only statically significant among monozygotic twins. Twin studies were not included in our analysis due to altered and specific factors including maternal, fetal, and placental parameters [34].

The association between IUGR, postnatal energy restriction, and neurodevelopment was examined using multivariate logistic regression techniques in a recent article by Uberos et al. [8]. IUGR was associated with behavioural disorders (OR 2.60; 95% CI 1.25, 5.40) and delayed cognitive development (OR 2.64; 95% CI 1.34, 5.20). In very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants, IUGR was associated with behavioural disorders. On the other hand, postnatal energy restriction was significantly associated with motor disorders, infantile cerebral palsy and sensory disorders [8].

In a 2021 retrospective cohort study in Taiwan, where all births between 2000 and 2010 were recorded and 517 cases of ASD were found, the adjusted odds ratio in IUGR children was 8.6 [13].

In a review from 2016, in which cognitive data from 15 studies and behavioural data from 6 studies were analyzed, children with IUGR and SGA had lower cognitive scores compared with controls 0.38 p < 0.00001, but ADHD incidence was not significantly different between the two groups [35]. Data from this particular study was not evaluated in our review due to its misconception and differentiation between IUGR neonates and SGA neonates.

A few studies showed special interest in premature IUGR. Korzeniewski et al., in a multicenter prospective observational study, evaluated 889 10-year-old children who had been born before 28 weeks of gestation for the presence of ASD. Extremely preterm infants with severe FGR were found to have an increased risk of behavioural dysfunctions, including ASD, but that did not reach statistical significance [11]. Similarly, a retrospective cohort study evaluating very preterm infants with IUGR and appropriate-for-gestational-age (AGA) infants concluded that the former were more likely to have a positive result according to the Modified Checklist for Autism (OR 2.12) [14]

A remarkable study in FGR research was a prospective multicenter unblinded randomized trial conducted from 2005 to 2010 in European centres, the Trial of Randomized Umbilical and Fetal Flow in Europe (TRUFFLE) in singleton pregnancies at 26–32 weeks of gestation with FGR diagnosis; this was the first wide study that, while monitoring management strategies in FGR children, also revealed interesting correlations after following up with these children [36]. In the study, five hundred and three women were randomized to deliver according to short-term variation and umbilical artery Doppler criteria. The purpose of this was to evaluate survival without cerebral palsy and neurosensory impairment or with a Bayley-III developmental score of < 8.5 at 2 years of age. The TRUFFLE study found neurodevelopmental impairment in 10% of the study population [37,38]. That research study continued in TRUFFLE study 2, a randomized controlled trial that compared the timing of delivery in FGR children with or without the use of the umbilical cerebral ratio (UCR) with the children’s neurodevelopmental outcomes. The study is still ongoing [38]. Due to the physiology of FGR neonates, their gestation is often complicated by prematurity. Since prematurity alone is considered to increase the probability of an ASD or ADHD diagnosis, a few studies tried to evaluate preterm neonates with and without FGR. In a 2011 study by Morsing et al., very preterm IUGR neonates had an increased risk of cognitive impairment compared to other preterm neonates. However, tests that evaluated ADHD likelihood did not differ [10]. More recently, Check et al. found significantly lower Bayley-III Scores in FGR children in a group of preterm neonates born before 30 weeks of gestation [9].

Interestingly, many studies attempted to identify an association between magnetic resonance features and neurodevelopmental disorders in FGR infants. A study found ten common resting-state networks involving cortical and subcortical regions and the cerebellum. FGR infants showed patterns of increased connectivity in the visual network and decreased connectivity in the auditory/language and dorsal attention networks. Yet no significant differences between groups were found after using a seed-based correlation analysis [12]. In a retrospective study conducted in 2019, T2-weighted images were obtained from IUGR and AGA infants. Smaller total intracranial volume and altered Jacobian determinants in anatomical regions such as the Rolandic operculum, gyrus rectus, hippocampus, thalamus, etc., were noticed in IUGR infants [14].

Some important limitations need to be mentioned. First of all, the number of included studies is relatively small and that most of them were of a retrospective design and had small sample sizes. Residual confounding, due to maternal health or various socioeconomic factors, etc., may have introduced additional bias and hampered the generalizability of the results. Additionally, there was significant heterogeneity and variability among studies with regard to the definitions and measures used to correlate IUGR/FGR and autism spectrum disorders or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Finally, the included studies lacked biological mechanistic data that could shed light on the precise underlying etiologic factors. Future large-scale prospective population studies are needed to strengthen the current level of evidence.

4. Conclusions

While autism spectrum disorders end attention deficiency disorder have been generally associated with FGR children, the existing body of literature offers limited evidence to support this theory. More well-designed studies are needed, including an in-depth analysis of the possible underlying mechanisms and factors responsible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.; methodology, M.P. and I.M.; software, A.K.; validation, A.K. and I.M.; formal analysis I.M.; investigation, A.K. and M.P.; resources A.K.; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, A.K. and I.M.; visualization, M.P.; supervision, A.K.; project administration, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Alexandros Sotiriadis for his expert advice and encouragement throughout this difficult project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gordijn, S.J.; Beune, I.M.; Thilaganathan, B.; Papageorghiou, A.; Baschat, A.A.; Baker, P.N.; Silver, R.M.; Wynia, K.; Ganzevoort, W. Consensus definition of fetal growth restriction: A Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 48, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froen, J.F.; Gardosi, J.O.; Thurmann, A.; Francis, A.; Stray-Pedersen, B. Restricted fetal growth in sudden intrauterine unexplained death. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2004, 83, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardozza, L.M.; Caetano, A.C.; Zamarian, A.C.; Mazzola, J.B.; Silva, C.P.; Marçal, V.M.G.; Lobo, T.F.; Peixoto, A.B.; Júnior, E.A. Fetal growth restriction: Current knowledge. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 295, 1061–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, W.; Liu, J. Neurodevelopment in children with intrauterine growth restriction: Adverse effects and interventions. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016, 29, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langridge, A.T.; Glasson, E.J.; Nassar, N.; Jacoby, P.; Pennell, C.; Hagan, R.; Bourke, J.; Leonard, H.; Stanley, F.J. Maternal conditions and perinatal characteristics associated with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e50963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E.; Pearson, R.; Fernandes, M.; Santos, I.S.; Barros, F.C.; Victora, C.G.; Stein, A.; Matijasevich, A. Are fetal growth impairment and preterm birth causally related to child attention problems and ADHD? Evidence from a comparison between high-income and middle-income cohorts. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillberg, C.; Wing, L. Autism: Not an extremely rare disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1999, 99, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uberos, J.; Jimenez-Montilla, S.; Machado-Casas, I.; Laynez-Rubio, C.; Fernández-Marin, E.; Campos-Martínez, A. The association between restricted intra-uterine growth and inadequate postnatal nutrition in very-low-birth-weight infants and their neurodevelopmental outcomes: A 50-month follow-up study. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Check, J.; Shuster, C.; Hofheimer, J.; Camerota, M.; Dansereau, L.M.; Smith, L.M.; Carter, B.S.; DellaGrotta, S.A.; Helderman, J.; Kilbride, H.; et al. Preeclampsia, Fetal Growth Restriction, and 24-Month Neurodevelopment in Very Preterm Infants. JAMA Netw. Open. 2024, 7, e2420382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsing, E.; Asard, M.; Ley, D.; Stjernqvist, K.; Marsál, K. Cognitive function after intrauterine growth restriction and very preterm birth. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e874–e882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzeniewski, S.J.; Allred, E.N.; Joseph, R.M.; Heeren, T.; Kuban, K.C.; O’shea, T.M.; Leviton, A.; ELGAN Study Investigators. Neurodevelopment at Age 10 Years of Children Born < 28 Weeks with Fetal Growth Restriction. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20170697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla, N.; Fransson, P.; Donaire, A.; Figueras, F.; Arranz, A.; Sanz-Cortés, M.; Tenorio, V.; Bargallo, N.; Junqué, C.; Lagercrantz, H.; et al. Intrinsic Functional Connectivity in Preterm Infants with Fetal Growth Restriction Evaluated at 12 Months Corrected Age. Cereb. Cortex 2017, 27, 4750–4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.C.; Wang, Y.H.; Chiou, J.Y.; Wei, J.C. Perinatal Factors in Newborn Are Insidious Risk Factors for Childhood Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Population-based Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacchi, C.; O’Muircheartaigh, J.; Batalle, D.; Counsell, S.J.; Simonelli, A.; Cesano, M.; Falconer, S.; Chew, A.; Kennea, N.; Nongena, P.; et al. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes following Intrauterine Growth Restriction and Very Preterm Birth. J. Pediatr. 2021, 238, 135–144.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.A.; Williams, S.; Patrick, M.E.; Valencia-Prado, M.; Durkin, M.S.; Howerton, E.M.; Ladd-Acosta, C.M.; Pas, E.T.; Bakian, A.V.; Bartholomew, P.; et al. Prevalence and Early Identification of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 4 and 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 16 Sites, United States, 2022. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2025, 74, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryson, S.; Smith, I. Epidemiology of autism: Prevalence, associated characteristics, and implications for research and service delivery. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 1998, 4, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musullulu, H. Evaluating attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A review of current methods and issues. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1466088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, C.R.; White, T.A.; Piscopo, B.R.; Sutherland, A.E.; Miller, S.L.; Camm, E.J.; Allison, B.J. Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Implications of Growth Restriction: Mechanisms and Potential Treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geipel, A.; Gembruch, U. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynaecology; Evaluation of Fetal and Uteroplacental Blood Flow; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 209–227. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Melendez, M.; Yawno, T.; Allison, B.J.; Jenkin, G.; Wallace, E.M.; Miller, S.L. Cerebrovascular adaptations to chronic hypoxia in the growth restricted lamb. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2015, 45, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polglase, G.R.; Allison, B.J.; Coia, E.; Li, A.; Jenkin, G.; Malhotra, A.; Sehgal, A.; Kluckow, M.; Gill, A.W.; Hooper, S.B.; et al. Altered cardiovascular function at birth in growth-restricted preterm lambs. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 80, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.Q.; Li, H.B.; Zhai, D.S.; Yang, L.Q. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder diagnosis by birth weight, gestational age, and size for gestational age: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 2035–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang-Karlsson, S.; Räikkönen, K.; Pesonen, A.K.; Kajantie, E.; Paavonen, E.J.; Lahti, J.; Hovi, P.; Heinonen, K.; Järvenpää, A.-L.; Eriksson, J.G.; et al. Very low birth weight and behavioral symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in young adulthood: The Helsinki study of very-low-birth-weight adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sucksdorff, M.; Lehtonen, L.; Chudal, R.; Suominen, A.; Joelsson, P.; Gissler, M.; Sourander, A. Preterm Birth and Poor Fetal Growth as Risk Factors of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Pediatrics 2015, 136, e599–e608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumberland, A.; Hale, N.; Azhan, A.; Gilchrist, C.P.; Chincarini, G.; Tolcos, M. Excitatory and inhibitory neuron imbalance in the intrauterine growth restricted fetal guinea pig brain: Relevance to the developmental origins of schizophrenia and autism. Dev. Neurobiol. 2023, 83, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, B.; Luo, M.; Xie, L.; Lu, M.; Lu, X.; Zhang, S.; Wei, L.; Zhou, X.; Yao, B.; et al. Microbiota-indole 3-propionic acid-brain axis mediates abnormal synaptic pruning of hippocampal microglia and susceptibility to ASD in IUGR offspring. Microbiome 2023, 11, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, S.; Luo, M.; Lu, M.; Wei, L.; Zhou, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, D. Prenatal caffeine exposure induces autism-like behaviors in offspring under a high-fat diet via the gut microbiota-IL-17A-brain axis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 269, 115797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, M.; Moster, D.; Wilcox, A.J. Term Birth Weight and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes. Epidemiology 2021, 32, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.M.; Hernández-Díaz, S.; Bateman, B.T.; Park, Y.M.; Desai, R.J.; Gray, K.J.; Patorno, E.M.; Mogun, H.; Huybrechts, K.F. Placental Complications Associated with Psychostimulant Use in Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 130, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, T.A.; Grunau, R.E.; McAuliffe, F.M.; Pinnamaneni, R.; Foran, A.; Alderdice, F.A. Early childhood neurodevelopment after intrauterine growth restriction: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilainen, R.; Heinonen, K.; Siren-Tiusanen, H. Effect of intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) on the psychological performance of preterm children at preschool age. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 1988, 29, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, H.; Nassar, N.; Bourke, J.; Blair, E.; Mulroy, S.; de Klerk, N.; Bower, C. Relation between intrauterine growth and subsequent intellectual disability in a ten-year population cohort of children in Western Australia. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 167, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, P.; Bo, T.; Luo, K. Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes of Intrauterine Growth Restriction School-Age Children. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20153868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaksson, J.; Ruchkin, V.; Ljungström, T.; Bölte, S. Evaluation of Birth Weight and Neurodevelopmental Conditions Among Monozygotic and Dizygotic Twins. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2321165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pels, A.; Knaven, O.C.; Wijnberg-Williams, B.J.; Eijsermans, M.; Tollenaer, S.M.-D.; Aarnoudse-Moens, C.; Koopman-Esseboom, C.; van Eyck, J.; Derks, J.; Ganzevoort, W.; et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes at five years after early-onset fetal growth restriction: Analyses in a Dutch subgroup participating in a European management trial. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 234, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frusca, T.; Todros, T.; Lees, C.; Bilardo, C.M.; TRUFFLE Investigators. Outcome in early-onset fetal growth restriction is best combining computerized fetal heart rate analysis with ductus venosus Doppler: Insights from the Trial of Umbilical and Fetal Flow in Europe. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, S783–S789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, C.C.; Marlow, N.; van Wassenaer-Leemhuis, A.; Arabin, B.; Bilardo, C.M.; Brezinka, C.; Calvert, S.; Derks, J.B.; Diemert, A.; Duvekot, J.J.; et al. 2 year neurodevelopmental and intermediate perinatal outcomes in infants with very preterm fetal growth restriction (TRUFFLE): A randomised trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2162–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylrea-Foley, B.; Thornton, J.G.; Mullins, E.; Marlow, N.; Hecher, K.; Ammari, C.; Arabin, B.; Berger, A.; Bergman, E.; Bhide, A.; et al. Perinatal and 2-year neurodevelopmental outcome in late preterm fetal compromise: The TRUFFLE 2 randomised trial protocol. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e055543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.