Toward a Dynamic Follow-Up Protocol in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Six-Month Out-of-Brace Evaluation as the Key Predictor of Treatment Success

Highlights

- The six-month out-of-brace radiographic evaluation is the most reliable predictor of long-term brace treatment success in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis.

- Lumbar and single-curve patterns show significantly better and more stable correction compared to thoracic or multiple-curve deformities.

- Clinical follow-up in AIS should focus on dynamic, time-dependent assessment rather than relying solely on initial in-brace correction.

- The six-month out-of-brace spine radiograph should be considered as an integral part of the standard clinical protocol for brace treatment evaluation to ensure more accurate assessment of treatment outcomes.

- Patients with thoracic or complex curve patterns require intensified monitoring and individualized treatment protocols to optimize outcomes.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

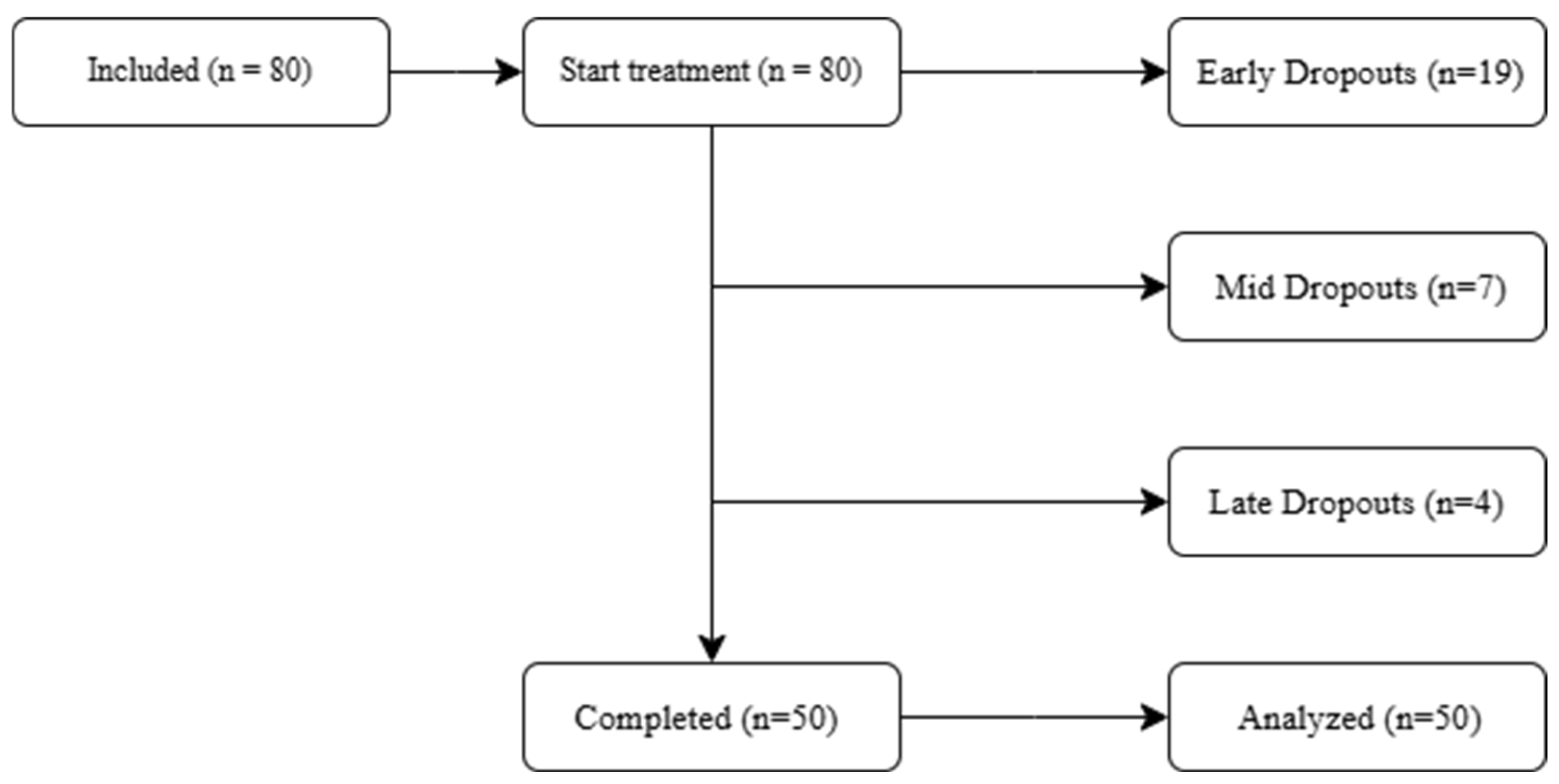

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Outcomes and Measurements

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Curve Type and Correction Outcomes

3.3. Longitudinal Cobb Angle Analysis

3.4. Regional Differences

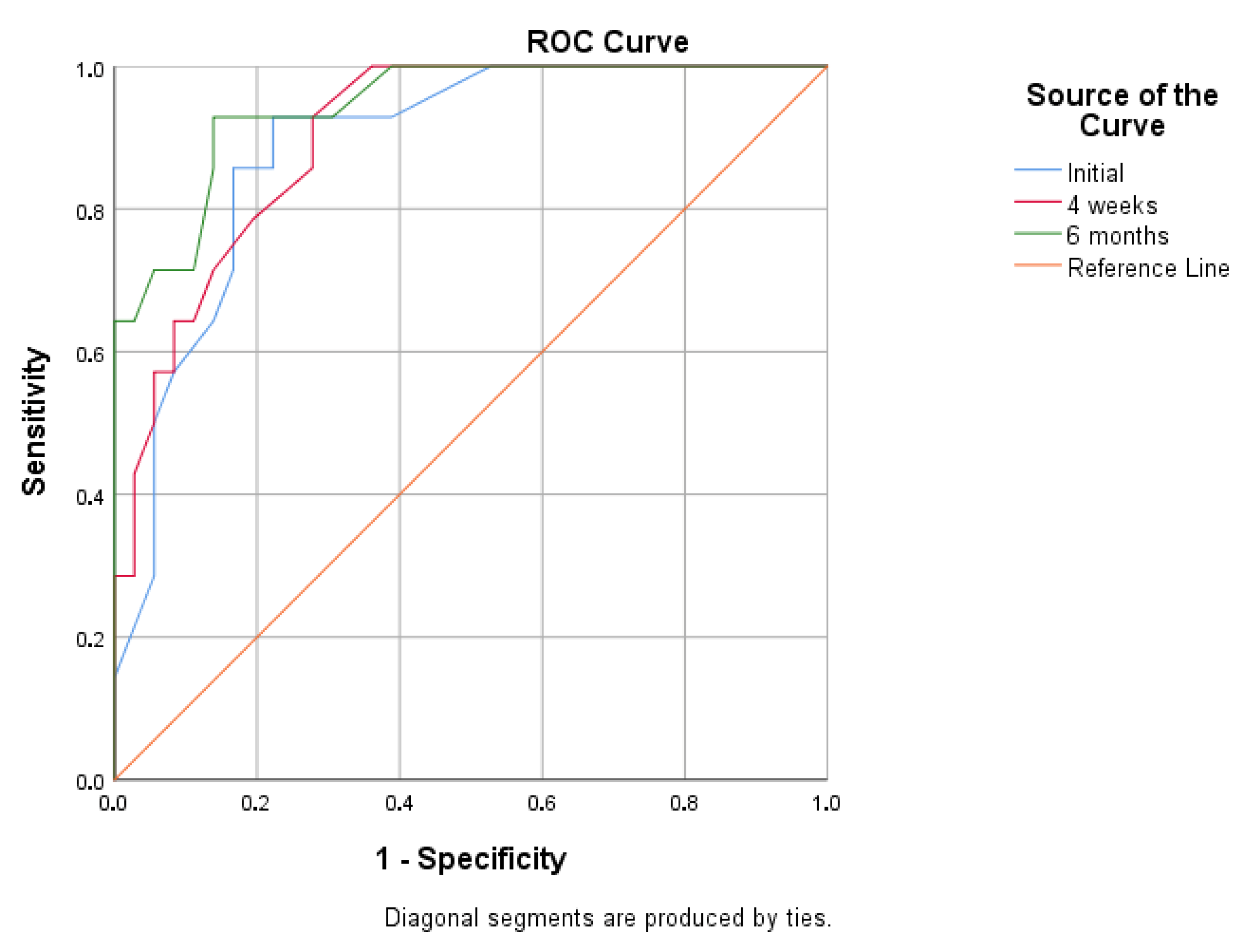

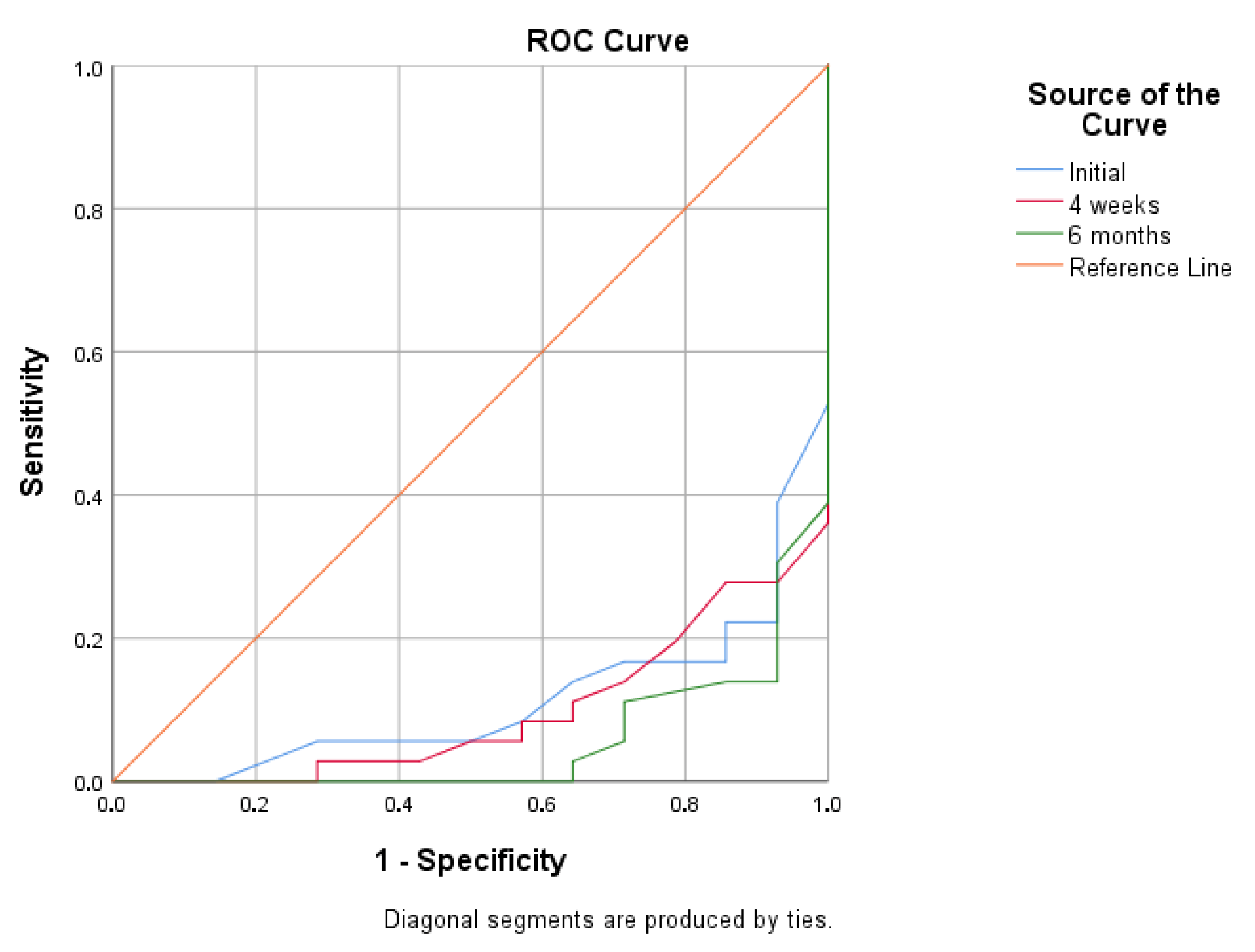

3.5. Predictors of Treatment Success

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Results

4.2. Clinical Implications

4.3. Scientific Significance

4.4. Previous Research

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

4.6. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | three-dimensional |

| AIS | adolescent idiopathic scoliosis |

| AP | anteroposterior |

| ATR | angle of trunk rotation |

| BSPTS | Barcelona Scoliosis Physical Therapy School |

| CAD/CAM | computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing |

| CMB | Chêneau modified brace |

| CI | confidence interval |

| FAMA | Functionally Aware Motoric Activity |

| OOB | Out of brace |

| OMC | Osaka Medical College (brace) |

| OR | odds ratio |

| PRM | Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine |

| PSSE | physiotherapeutic scoliosis-specific exercises |

| SEAS | Scientific Exercises Approach to Scoliosis |

| SRS | Scoliosis Research Society |

| SOSORT | Society on Scoliosis Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation Treatment |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| XR | X-ray |

| BrAIST | Bracing in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Trial |

References

- Weinstein, S.L.; Dolan, L.A.; Cheng, J.C.Y.; Danielsson, A.; Morcuende, J.A. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Lancet 2008, 371, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konieczny, M.R.; Senyurt, H.; Krauspe, R. Epidemiology of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Child Orthop. 2013, 7, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.; Castelein, R.M.; Chu, W.C.; Danielsson, A.J.; Dobbs, M.B.; Grivas, T.B.; Gurnett, C.A.; Luk, K.D.; Moreau, A.; Newton, P.O.; et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, S.L.; Dolan, L.A.; Wright, J.G.; Dobbs, M.B. Effects of bracing in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1512–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, H.R.; Moramarco, M.M.; Borysov, M.; Ng, S.Y.; Lee, S.G.; Nan, X.; Moramarco, K.A. Postural rehabilitation for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Asian Spine J. 2016, 10, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, S.; Piazzolla, A.; Tafuri, S.; Borracci, C.; Martucci, A.; De Giorgi, G. Chêneau brace for AIS: Long-term results. Eur. Spine J. 2013, 22, S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, F.; Trieb, K. Scoliosis: Brace treatment—From the past 50 years to the future. Medicine 2022, 101, e30556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaina, F.; De Mauroy, J.C.; Grivas, T.; Hresko, M.T.; Kotwizki, T.; Maruyama, T.; Price, N.; Rigo, M.; Stikeleather, L.; Wynne, J.; et al. Bracing for scoliosis in 2014: State of the art. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2014, 50, 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Zaina, F.; Cordani, C.; Donzelli, S.; Lazzarini, S.G.; Arienti, C.; Del Furia, M.J.; Negrini, S. Bracing interventions for AIS with surgical indication: A systematic review. Children 2022, 9, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; Donzelli, S.; Aulisa, A.G.; Czaprowski, D.; Schreiber, S.; de Mauroy, J.C.; Diers, H.; Grivas, T.B.; Knott, P.; Kotwicki, T.; et al. 2016 SOSORT guidelines: Orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment during growth. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2018, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticone, M.; Ambrosini, E.; Cazzaniga, D.; Rocca, B.; Ferrante, S. Active self-correction reduces deformity and improves quality of life in mild AIS. Eur. Spine J. 2014, 23, 1204–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdishevsky, H.; Lebel, V.A.; Bettany-Saltikov, J.; Rigo, M.; Lebel, A.; Hennes, A.; Romano, M.; Białek, M.; M’hango, A.; Betts, T.; et al. Physiotherapy scoliosis-specific exercises—A comprehensive review. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2016, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, A.; Hasserius, R.; Ohlin, A.; Nachemson, A.L. HRQoL in untreated vs. brace-treated AIS. Spine 2010, 35, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, J.O.; Newton, P.O.; Browne, R.H.; Katz, D.E.; Birch, J.G.; Herring, J.A. Bracing for idiopathic scoliosis: Number needed to treat. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2014, 96, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, H.R. The method of Katharina Schroth. Scoliosis 2011, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulisa, A.G.; Toniolo, R.M.; Falciglia, F.; Giordano, M.; Aulisa, L. Long-term results after brace treatment with Progressive Action Short Brace in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 57, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenssinck, M.L.B.; Frijlink, A.C.; Berger, M.Y.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; Verhagen, A.P. Effectiveness of bracing and conservative interventions. Phys. Ther. 2005, 85, 1329–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karavidas, N. Bracing In The Treatment Of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Evidence To Date. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2019, 10, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misterska, E.; Glowacki, M.; Latuszewska, J.; Adamczyk, K. Stress, appearance, body function in females with AIS. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicki, J.A.; Alman, B. Scoliosis: Review of diagnosis and treatment. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2007, 19, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.O.; Khoury, J.G.; Kishan, S.; Browne, R.H.; Mooney, J.F.; Arnold, K.D.; McConnell, S.J.; Bauman, J.A.; Finegold, D.N. Predicting scoliosis progression from skeletal maturity: A simplified classification. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2008, 90, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, Y.P.; Daures, J.P.; De Rosa, V.; Dimeglio, A. Progression risk of idiopathic juvenile scoliosis during pubertal growth. Spine 2006, 31, 1933–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, B.S.; Bernstein, R.M.; D’Amato, C.R.; Thompson, G.H. Standardization of criteria for AIS brace studies. Spine 2005, 30, 2068–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mauroy, J.C.; Lecante, C.; Barral, F. The Lyon approach to conservative treatment. Scoliosis 2011, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Zhang, D.; Yuan, F.; Peng, Q.; Lv, C.; Qi, H.; Zhao, M.; Chen, G.; Ye, H.; Gao, G.; et al. Efficacy of computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing-based braces for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Discov. Med. 2025, 2, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobetto, N.; Aubin, C.-É.; Parent, S.; Barchi, S.; Turgeon, I.; Labelle, H. 3D correction of AIS with CAD/CAM and FEM-designed braces: RCT. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2017, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijević, V.; Rašković, B.; Popović, M.P.; Viduka, D.; Jevtić, N.; Pjanić, S. Treatment of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis with the Conservative Schroth Method: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare 2025, 13, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijević, V.; Šćepanović, T.; Jevtić, N.; Rašković, B.; Milankov, V.; Milošević, Z.; Ninković, S.S.; Chockalingam, N.; Obradović, B.; Drid, P. Schroth method in idiopathic scoliosis: Systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijević, V.; Viduka, D.; Šćepanović, T.; Maksimović, N.; Giustino, V.; Bianco, A.; Drid, P. Schroth method and core stabilization in idiopathic scoliosis: Meta-analysis. Eur. Spine J. 2022, 31, 3500–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijević, V.; Rašković, B.; Popović, M.; Viduka, D.; Nikolić, S.; Drid, P. Treatment of idiopathic scoliosis with conservative methods based on exercises: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donzelli, S.; Zaina, F.; Negrini, S. In Defense of Adolescents: They Really Do Use Braces for the Hours Prescribed, If Good Help Is Provided. Results from a Prospective Everyday Clinic Cohort Using Thermobrace. Scoliosis 2012, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donzelli, S.; Zaina, F.; Negrini, S. The three-dimensional importance of the Sforzesco brace correction. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2017, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gstoettner, M.; Sekyra, K.; Walochnik, N.; Winter, P.; Wachter, R.; Zweymüller, K. Reliability of Cobb angle: Manual vs digital tools. Eur. Spine J. 2007, 16, 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, J.D.; Tosteson, T.D.; Tosteson, A.N.; Zhao, W.; Morgan, T.S.; Abdu, W.A.; Herkowitz, H.; Weinstein, J.N. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: Eight-year results for the spine patient outcomes research trial. Spine 2014, 39, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, G.C.; Hill, D.L.; Le, L.H.; Raso, J.V.; Lou, E.H.; Moreau, M. Vertebral rotation measurement: A summary and comparison of common radiographic and CT methods. Spine 2008, 33, E510–E515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basques, B.A.; Golinvaux, N.S.; Bohl, D.D.; Yacob, A.; Toy, J.O.; Varthi, A.G.; Grauer, J.N. Use of an operating microscope during spine surgery is associated with minor increases in operating room times and no increased risk of infection. Spine 2014, 39, 1910–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Donzelli, S.; Poma, S.; Balzarini, L.; Borboni, A.; Negrini, S. Consistent and regular daily wearing improve bracing results: A case-control study. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2018, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fregna, G.; Rossi Raccagni, S.; Negrini, A.; Zaina, F.; Negrini, S. Personal and clinical determinants of brace-wearing time in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. Sensors 2023, 24, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donzelli, S.; Fregna, G.; Zaina, F.; Donzelli, A.; D’Amico, M.; Negrini, S. Predictors of clinically meaningful results of bracing in a large cohort of adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis reaching the end of conservative treatment. Children 2023, 10, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrtovec, T.; Pernuš, F.; Likar, B. Methods for quantitative evaluation of spinal curvature. Eur. Spine J. 2009, 18, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; Di Felice, F.; Negrini, F.; Rebagliati, G.; Zaina, F.; Donzelli, S. Predicting final results of brace treatment: First out-of-brace radiograph is better than in-brace—SOSORT 2020 Award Winner. Eur. Spine J. 2022, 31, 3519–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aulisa, A.G.; Giordano, M.; Falciglia, F.; Marzetti, E.; Guzzanti, V.; Aulisa, L. Compliance and brace treatment in juvenile and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Scoliosis 2014, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courvoisier, A.; Drevelle, X.; Dubousset, J.; Miladi, L.; Skalli, W. 3D analysis of brace treatment in idiopathic scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2013, 22, 2449–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovadia, D.; Eylon, S.; Mashiah, A.; Wientroub, S.; Lebel, E.D. Factors associated with the success of the Rigo System Chêneau brace in treating mild to moderate AIS. J. Child Orthop. 2012, 6, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, F.; Wimmer, C.; Behensky, H. Estimating final outcome of brace treatment for thoracic idiopathic scoliosis at 6-month follow-up. Pediatr. Rehabil. 2003, 6, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroki, H.; Inomata, N.; Hamanaka, H.; Higa, K.; Chosa, E.; Tajima, N. Predictive factors of Osaka Medical College (OMC) brace outcome in AIS. Scoliosis 2015, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.E.; Durrani, A.A. Factors influencing outcome in bracing large curves in AIS patients. Spine 2001, 26, 2354–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mauroy, J.C.; Pourret, S.; Barral, F. Immediate in-brace correction with the new Lyon brace (ARTbrace): Results of 141 cases. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 59, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournavitis, N.; Çolak, T.K.; Voutsas, C. Chêneau-style braces and vertebral wedging in AIS. S. Afr. J. Physiother. 2021, 77, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuru Çolak, T.; Akçay, B.; Apti, A.; Çolak, İ. Schroth Best Practice program and Chêneau-type brace: Long-term follow-up in AIS. Children 2023, 10, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; Donzelli, S.; Negrini, A.; Parzini, S.; Romano, M.; Zaina, F. Specific exercises reduce the need for bracing: Clinical trial in AIS. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 62, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulisa, A.G.; Guzzanti, V.; Falciglia, F.; Giordano, M.; Marzetti, E.; Aulisa, L. Lyon bracing in adolescent females with thoracic AIS: Prospective study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015, 16, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivas, T.B.; Negrini, S.; Aubin, C.-É.; Aulisa, A.G.; De Mauroy, J.C.; Donzelli, S.; Hresko, M.T.; Kotwicki, T.; Lou, E.; Maruyama, T.; et al. Nonoperative management of AIS using braces. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2022, 46, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.; Schlosser, T.P.C.; Jimale, H.; Homans, J.F.; Kruyt, M.C.; Castelein, R.M. Effectiveness of different bracing concepts in AIS: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huo, Z.; Hu, Z.; Lam, T.P.; Cheng, J.C.Y.; Chung, V.C.-H.; Yip, B.H.K. Which Interventions May Improve Bracing Compliance in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlösser, T.P.C.; van Stralen, M.; Brink, R.C.; Chu, W.C.; Lam, T.P.; Wong, K.K.Y. Three-dimensional characterization of torsion and asymmetry of the intervertebral discs versus vertebral bodies in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine J. 2014, 14, 1856–1863. [Google Scholar]

- Kuklo, T.R.; Potter, B.K.; Lenke, L.G. Vertebral rotation and thoracic torsion in AIS: Best radiographic correlate? J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2005, 18, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Mean ± SD (Min–Max) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed (n = 50) | Dropouts (n = 30) | p Value | |

| Age (years) | 13.5 ± 1.4 (10–16) | 13.2 ± 1.6 (10–15.5) | 0.326 a |

| Sex (female/male) | 40/10 | 25/5 | 0.941 b |

| Curve Location | thoracic (n = 15) | thoracic (n = 8) | 0.967 b |

| thoracolumbar (n = 7) | thoracolumbar (n = 4) | ||

| lumbar (n = 28) | lumbar (n = 18) | ||

| Risser sign Initial | 1.47 ± 1.18 (0–3) | 1.25 ± 1.23 (0–3) | 0.378 c |

| Initial Cobb angle | 28.7± 7.1 (20–44) | 29.2 ± 9.0 (20–45) | 0.805 a |

| Variables | Mean ± SD (Min–Max) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 13.5 ± 1.4 (12.5–16) |

| Height Initial (cm) | 166.83 ± 9.45 (140.5–193.5) |

| Height Final (cm) | 172.96 ± 8.57 (153–203) |

| Weight Initial (kg) | 52.75 ± 12.35 (28–91) |

| Weight Final (kg) | 61.52 ± 12.41 (38–110) |

| Sex (female/male) | 40/10 |

| Curve Location | thoracic (n = 15) |

| thoracolumbar (n = 7) | |

| lumbar (n = 28) | |

| Risser sign Initial | 1.47 ± 1.18 (0–3) |

| Risser sign Final | 4.7 ± 0.39 (4–5) |

| Total duration of treatment (months) | 48.29 ± 9.36 (29.77–71.47) |

| Variable | n | Correction (Mean ± SD, Min–Max) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Curves | 0.014 | ||

| Single curve scoliosis | 11 | 11.4 ± 6.1° (2–24) | |

| Multiple curve scoliosis | 39 | 5.3 ± 7.2° (−10–23) | |

| Compensatory Curves | 0.023 | ||

| Present | 40 | 5.5 ± 7.2° (−10–23) | |

| Absent | 10 | 11.3 ± 6.5° (2–24) |

| Time | Cobb Angle (Mean ± SD) | Comparison | Mean Difference ± SE | CI 95% | η2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 28.7 ± 7.1 | Initial vs. 4 weeks | 15.96 ± 0.92 | (13.44, 18.48) | 0.000 | |

| Initial vs. 6 months | 7.92 ± 0.81 | (5.68, 10.16) | 0.000 | |||

| Initial vs. Final | 6.64 ± 1.04 | (3.79, 9.50) | 0.87 | 0.000 | ||

| 4 weeks | 12.8 ± 9.1 | 4 weeks vs. 6 months | −8.04 ± 0.94 | (−10.63, −5.45) | 0.000 | |

| 4 weeks vs. Final | −9.32 ± 1.06 | (−12.22, −6.42) | 0.000 | |||

| 6 months | 20.8 ± 10.5 | 6 months vs. Final | −1.28 ± 0.95 | (−3.89, 1.33) | 1 | |

| Final | 22.1 ± 10.5 | |||||

| ATR (Mean ± SD) | ||||||

| Initial | 9.00 ± 3.49 | Initial vs. Final | 3.9 ± 0.56 | (2.78, 5.02) | 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Final | 5.1 ± 3.22 |

| Region (n) | Time Comparison | Cobb Angle (Mean ± SD) | Mean Difference ± SE | CI 95% | η2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thoracic (15) | Initial vs. 4 weeks | 30.47 ± 8.18 → 16.67 ± 9.21 | 13.80 ± 1.66 | (9.238, 18.362) | <0.001 | |

| Initial vs. 6 months | 30.47 ± 8.18 → 24.13 ± 11.37 | 6.33 ± 1.49 | (2.231, 10.436) | 0.001 | ||

| Initial vs. Final | 30.47 ± 8.18 → 26.93 ± 10.53 | 3.53 ± 1.85 | (−1.562, 8.629) | 0.62 | 0.373 | |

| 4 weeks vs. 6 months | 16.67 ± 9.21 → 24.13 ± 11.37 | −7.47 ± 1.73 | (−12.240, −2.693) | <0.001 | ||

| 4 weeks vs. Final | 16.67 ± 9.21 → 26.93 ± 10.53 | −10.27 ± 1.92 | (−15.565, −4.969) | <0.001 | ||

| 6 months vs. Final | 24.13 ± 11.37 → 26.93 ± 10.53 | −2.80 ± 1.75 | (−7.616, 2.016) | 0.696 | ||

| Thoracolumbar (7) | Initial vs. 4 weeks | 27.43 ± 8.42 → 12.29 ± 8.12 | 15.14 ± 2.42 | (8.465, 21.820) | <0.001 | |

| Initial vs. 6 months | 27.43 ± 8.42 → 18.14 ± 8.86 | −9.29 ± 2.18 | (−15.291, −3.281) | 0.001 | ||

| Initial vs. Final | 27.43 ± 8.42 → 17.86 ± 10.45 | −9.57 ± 2.71 | (−17.030, −2.113) | 0.48 | 0.006 | |

| 4 weeks vs. 6 months | 12.29 ± 8.12 → 18.14 ± 8.86 | −5.86 ± 2.54 | (−12.845, 1.131) | 0.152 | ||

| 4 weeks vs. Final | 12.29 ± 8.12 → 17.86 ± 10.45 | −5.57 ± 2.82 | (−13.327, 2.184) | 0.322 | ||

| 6 months vs. Final | 18.14 ± 8.86 → 17.86 ± 10.45 | 0.29 ± 2.56 | (−6.764, 7.336) | 1 | ||

| Lumbar (28) | Initial vs. 4 weeks | 28.11 ± 6.17 → 10.79 ± 8.88 | 17.32 ± 1.21 | (13.983, 20.660) | <0.001 | |

| Initial vs. 6 months | 28.11 ± 6.17 → 19.68 ± 10.30 | 8.43 ± 1.09 | (5.426, 11.431) | <0.001 | ||

| Initial vs. Final | 28.11 ± 6.17 → 20.54 ± 9.93 | 7.57 ± 1.35 | (3.842, 11.301) | 0.82 | <0.001 | |

| 4 weeks vs. 6 months | 10.79 ± 8.88 → 19.68 ± 10.30 | −8.89 ± 1.27 | (−12.387, −5.399) | <0.001 | ||

| 4 weeks vs. Final | 10.79 ± 8.88 → 20.54 ± 9.93 | −9.75 ± 1.41 | (−13.628, −5.872) | <0.001 | ||

| 6 months vs. Final | 19.68 ± 10.30 → 20.54 ± 9.93 | −0.86 ± 1.28 | (−4.382, 2.668) | 1.000 |

| Pearson Correlation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 4 Weeks | 6 Months | Final | ||

| Initial | 1 | 0.705 | 0.865 | 0.717 | |

| 4 weeks | 0.705 | 1 | 0.778 | 0.72 | |

| 6 months | 0.865 | 0.778 | 1 | 0.795 | |

| Final | 0.717 | 0.72 | 0.795 | 1 | |

| Correlation of Cobb Differences and Later Measurements | |||||

| Initial–4 weeks | Initial–6 months | Initial–Final | |||

| Initial–4 weeks | 1 | 0.412 | 0.424 | ||

| Initial–6 months | 1 | 0.496 | |||

| Initial–Final | 1 | ||||

| OR for Final Cobb Angle < 30° | |||||

| Variable | OR | SE | p-value | 95% CI | Pseudo R2 |

| Initial | 0.759 | 0.078 | <0.001 | 0.651–0.885 | 0.36 |

| 4 weeks | 0.784 | 0.07 | <0.001 | 0.684–0.899 | 0.393 |

| 6 months | 0.726 | 0.093 | 0.001 | 0.605–0.870 | 0.485 |

| OR for Improvement > 5° Cobb angle | |||||

| Change Type | OR | SE | p-value | 95% CI | Pseudo R2 |

| Initial to 4 weeks | 1.084 | 0.048 | 0.092 | 0.987–1.192 | 0.06 |

| Initial to 6 months | 1.183 | 0.065 | 0.009 | 1.042–1.344 | 0.159 |

| OR for Improvement by Correction Rate | |||||

| Correction Rate | OR | SE | p-value | 95% CI | Pseudo R2 |

| 4 weeks (%) | 1.028 | 0.012 | 0.022 | 1.004–1.053 | 0.113 |

| 6 months (%) | 1.037 | 0.015 | 0.017 | 1.007–1.069 | 0.144 |

| Multiple Linear Regression for Final Cobb Angle | |||||

| Variable | Crude Coefficient | p | Adjusted Coefficient | p | VIF |

| Cobb angle—Initial | 1.063 | <0.001 | 0.295 | 0.193 | 4.062 |

| Cobb angle—4 weeks | 0.832 | <0.001 | 0.235 | 0.1 | 2.575 |

| Cobb angle—6 months | 0.797 | <0.001 | 0.508 | 0.004 | 4.952 |

| ATR—Initial | 0.322 | 0.46 | −0.997 | <0.001 | 1.279 |

| ATR—Final | 1.547 | 0.001 | 0.612 | 0.004 | 1.281 |

| Measurement Time | AUC (Cobb > 30° = Positive) | AUC (Cobb < 30° = Positive) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 0.888 | 0.112 | (0.795, 0.980) | <0.001 |

| 4 weeks | 0.903 | 0.097 | (0.821, 0.985) | <0.001 |

| 6 months | 0.944 | 0.056 | (0.882, 1.000) | <0.001 |

| Predictor | OR (95% CI)—Complete Case | p (CC) | OR (95% CI)—Pooled MI | p (MI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Cobb angle | 0.759 (0.651–0.885) | <0.001 | 0.799 (0.670–0.954) | 0.017 |

| 4-week Cobb angle | 0.784 (0.684–0.889) | <0.001 | 0.827 (0.739–0.925) | 0.002 |

| 6-month Cobb angle | 0.726 (0.605–0.870) | 0.001 | 0.742 (0.607–0.905) | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pjanić, S.; Dimitrijević, V.; Rašković, B.; Obradović, B.; Jevtić, N.; Grivas, T.B.; Golić, F.; Talić, G. Toward a Dynamic Follow-Up Protocol in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Six-Month Out-of-Brace Evaluation as the Key Predictor of Treatment Success. Children 2026, 13, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010010

Pjanić S, Dimitrijević V, Rašković B, Obradović B, Jevtić N, Grivas TB, Golić F, Talić G. Toward a Dynamic Follow-Up Protocol in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Six-Month Out-of-Brace Evaluation as the Key Predictor of Treatment Success. Children. 2026; 13(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010010

Chicago/Turabian StylePjanić, Samra, Vanja Dimitrijević, Bojan Rašković, Borislav Obradović, Nikola Jevtić, Theodoros B. Grivas, Filip Golić, and Goran Talić. 2026. "Toward a Dynamic Follow-Up Protocol in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Six-Month Out-of-Brace Evaluation as the Key Predictor of Treatment Success" Children 13, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010010

APA StylePjanić, S., Dimitrijević, V., Rašković, B., Obradović, B., Jevtić, N., Grivas, T. B., Golić, F., & Talić, G. (2026). Toward a Dynamic Follow-Up Protocol in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Six-Month Out-of-Brace Evaluation as the Key Predictor of Treatment Success. Children, 13(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010010