Abstract

Background: Endometritis, maternal fever and wound infection represent the most frequent post-cesarean complications. The aim of the present research was to evaluate the incidence of post-cesarean infections after vaginal cleansing. Materials and methods: The databases analyzed were MEDLINE, Scopus, EMBASE, CENTRAL, Google Scholar, Clinicaltrials.gov and the Register of Controlled Trials. No language or geographical restrictions were applied. We included only randomized controlled trials that analyzed various vaginal antiseptic solutions to reduce postpartum endometritis. The terms employed were as follows: vaginal solution, cesarean section, endometritis, wound infection, chlorhexidine, povidone, metronidazole, cetrimide, and pregnancy. The PICO categorization was as follows: P—population: pregnant women; I—intervention: vaginal antiseptic; C—control: hands-off or routine care; O—outcome: post-cesarean endometritis, wound infection and postoperative fever; S—study design: randomized controlled trials. Results: A total of 32 articles, including 13,853 participants, were selected. The vaginal cleansing group showed a low incidence of endometritis. The chlorhexidine group had an OR of 0.56 (95% CI 0.45–0.70, p = 0.010). The povidone group had an OR of 0.47 (95% CI 0.37–0.59, p = 0.002). Considering maternal fever, 2598 patients from 5 studies in the chlorhexidine group were analyzed, alongside 6965 patients from 18 trials in the povidone group. The povidone group presented an Odds ratio of 0.47 (95% CI 0.38–0.57, p = 0.0001). A reduction in wound infection incidence was observed in the povidone group (OR = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.42–0.82, p < 0.05). Conclusions: Vaginal cleansing before cesarean section, particularly with povidone solutions, reduces the incidence of postoperative endometritis and maternal fever.

1. Introduction

Cesarean section (CS) is a surgical procedure associated with various complications [1]. Complication rates vary between 6 and 29 percent, dependent upon the study design, definitions and populations [2,3,4]. The most common post-cesarean complications are endometritis (6–27%), maternal fever (5–24%) and wound infection (2–9%) [5]. In comparison to vaginal births, these complications are considerably higher [6]. The implementation of CS antibiotic prophylaxis has reduced endometritis incidence by 75%; however, CS continues to have an important role in postoperative cesarean endometritis development [7,8,9]. The consequences of endometritis are bacteremia, peritonitis, intraabdominal abscess, and sepsis [10]. In addition, seroma and hematoma are wound morbidities [11]. They cause discomfort and prolonged hospitalization for patients [11]. It is hypothesized that abnormal vaginal bacteria flora, which can occur in association with fever, pelvic abscess, and sepsis, is the primary cause [12]. Research on vaginal bacterial alteration after antibiotic prophylaxis is limited [13,14,15]. Over the past two decades, several RCTs have been carried out to explore the association between preoperative vaginal disinfection and postoperative infection [16]. In addition, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) suggests aqueous iodine vaginal preparation before performing CS on a pregnant patient whose delivery is complicated by the preterm rupture of membranes [17]. Aqueous chlorhexidine vaginal preparation can be used if aqueous iodine vaginal preparation is unavailable or not recommended [18]. Different preparations for vaginal cleansing have been suggested to prevent the risk of post-cesarean infection [11]. Aqueous iodine vaginal preparations have also been shown to lower endometritis risk in women with ruptured membranes [18]. Higher efficacy was shown with iodine vaginal formulations [18]. Endometritis prevention solutions based on povidone and chlorhexidine are the most readily available, with the latter most active against anaerobic microorganisms [19,20]. In contrast, alternative solutions provide no a clear benefit in accordance with scientific evidence [21].

Our meta-analysis aims to investigate whether vaginal cleansing alongside prophylactic antibiotics would be a feasible option for decreasing the incidence of post-cesarean endometritis by evaluating data from published randomized controlled trials (RCTs). It is postulated that vaginal cleansing reduces the bacterial load in the vagina and reduces the incidence of postoperative infectious morbidity. As secondary outcomes, we analyze whether the addition of vaginal cleansing may reduce the incidence of maternal fever and wound infection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria and Inclusion Criteria

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [22] and the methods outlined in Mbuagbaw et al. [23]. The research protocol was recorded in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database (CRD42023465294). We evaluated RCTs that aimed to reduce postpartum endometritis using different vaginal antiseptic solutions, comparing them to each other or to a placebo or no treatment, in pregnant patients who had received antibiotics prior to or during the CS. The prespecified primary outcome was endometritis, defined as a maternal temperature > 38 °C (100.4 °F) with uterine tenderness and/or foul-smelling vaginal discharge. Secondary outcomes were wound infection and postoperative fever. Wound infection was defined most often as swelling, erythema, discharge, seroma, hematoma, or disruption of the incision line. Fever was defined as a temperature greater than 38 °C (101.2 °F) at least 24 h after delivery. The PICO categorization was as follows: P—population: pregnant women; I—intervention: vaginal antiseptic; C—control: hands-off or routine care; O—outcome: post-cesarean endometritis, wound infection and postoperative fever; S—study design: randomized controlled trials. We included only studies with pregnant women who had received antibiotic prophylaxis before or during their cesarean section and had received a vaginal antiseptic solution to prevent postpartum endometritis. Quasi-randomized and non-randomized trials, studies in which women did not receive antibiotic prophylaxis, or study interventions that did not target vaginal antisepsis were excluded. Letters, editorials, comments, and opinions were also excluded.

2.2. Search Strategy

We conducted an extensive review of the MEDLINE (accessed through PubMed), Scopus, EMBASE and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases from their origin to 23 January 2024. The search strategy included words from related texts regarding vaginal solutions, cesarean section, endometritis, wound infection, chlorhexidine, povidone, metronidazole, cetrimide, and pregnancy. A filter for randomized controlled trials only was applied to the search results (Appendix A). To reduce publication bias Google scholar was also searched. Moreover, the gray literature (NTIS, PsycEXTRA) was screened to search for the abstracts of international and national conferences. We also reviewed the references of the included studies and the related reviews for additional papers not captured during the original search. No language or geographic location restrictions were applied. Commentaries, letters to the editor, editorials, and reviews were excluded from the review. Other exclusion criteria included the following: quasi-randomized trials and trials without randomization and studies including patients undergoing cesarean section without antibiotic prophylaxis.

2.3. Study Selection

The abstracts were systematically evaluated and classified by two authors (I.I. and L.M.) independently. Agreement on possible relevance was accomplished by consensus. The full texts of the selected studies were evaluated by the same two authors, who extracted relevant data regarding the study details and the outcomes of interest in an autonomous manner. Upon consulting a third author (M.L.V.), the authors established a consensus after deliberating on every disagreement. Following the data screening process, the full texts of the selected abstracts were collected. Full texts, titles and abstracts that lacked adequate information according to the inclusion criteria were also acquired. Full-text articles were selected that complied with the inclusion criteria by the two reviewers using a data extraction form.

2.4. Data Extraction and Statistical Analysis

The data analysis was performed by R Studio version 4.1.3 (2022-03-10). The data extracted from the included articles for further analysis were as follows: demographic information (title, authors, journal and year), the characteristics of the sample (age, gestational age, delivery number, inclusion and exclusion criteria and number of participants), study-specific parameters (study type, form of application of perineal massage, duration of massage, time of application and use of lubricants), the follow-up and dropout rates of participants, and the results obtained (variables analyzed, instruments used, and results throughout the follow up). The characteristics of the trials and the extracted data were both presented in tables. Non-randomized or quasi-randomized studies were excluded. We also excluded studies if the outcome measures were inconsistent with our criteria or the intervention was not related to antiseptic vaginal wash. The meta-analysis was performed using the random-effects model, because of the observed heterogeneity. For each sub-study, the Odds ratios (OR) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated from the summary data provided. Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q test, with a p-value < 0.05 considered indicative of significant heterogeneity. Although I2 statistics are commonly used to quantify heterogeneity, in our analysis only the Q test was applied, as the reporting of between-study variance was limited in several included studies. Due to the limited number of studies in some subgroup analyses, a formal assessment of publication bias (e.g., funnel plot asymmetry or Egger’s test) was not feasible. Therefore, potential bias remains a limitation. Only complete outcome data were used for the synthesis.

2.5. Assessment of Risk of Bias

The assessment of the risk of bias in every study included was conducted in accordance with the standards delineated in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [24]. Each included trial underwent a critical examination of the following seven domains, as it became apparent that these concerns were associated with biased estimates of the effects of treatments: (1) random sequence generation; (2) allocation concealment; (3) the blinding of participants and personnel; (4) the blinding of outcome assessment; (5) incomplete outcome data; (6) selective reporting, and (7) other bias. The authors classified the evaluation of their judgements as having a “low risk”, a “high risk”, or an “unclear risk” of bias [24]. The risk-of-bias assessment was independently judged by 3 authors (I.I., L.M., C.M.). Disagreement was resolved by discussion with a fourth reviewer (M.L.V.).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

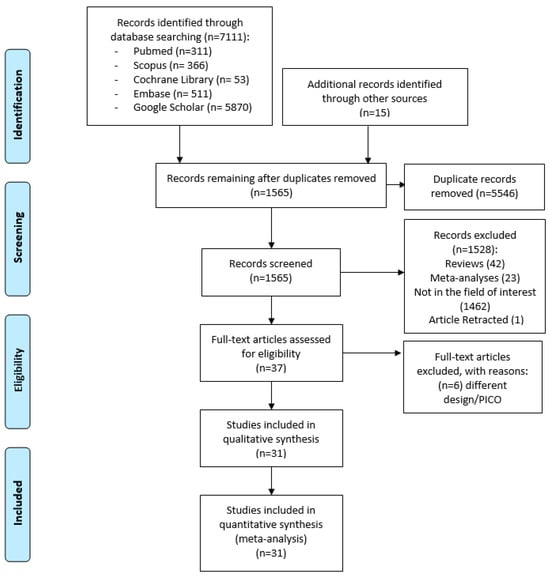

Of the 7126 total results identified, 5546 records were duplicates, so 1565 underwent title and abstract screening to see if they met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of these, 38 were then excluded according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of the 37 articles screened, 31 were finally selected (Figure 1). In total, 31 studies, including 13,627 participants, were included in the quantitative synthesis and network meta-analysis (Figure 1) [5,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the database search from the database origin to 23 January 2024.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The studies were conducted between 1997 and 2023. All studies included women with a diagnosis of endometritis, defined as a maternal temperature > 38 °C (100.4 °F) associated with uterine tenderness and/or foul-smelling vaginal discharge. A full list of the studies included is reported in Table 1 with the study information (year, country, number of participants, intervention and control groups, primary outcomes). Our meta-analysis included 32 RCTs with a total of 13,853 subjects [5,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. A total of 10 studies adopted vaginal cleansing with chlorhexidine [5,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] and included 6230 patients: 3089 in the treatment group and 3141 subjects in the control group. Different chlorhexidine solution concentrations were adopted: 0.05% [29], 0.20–0.25% [25,26,27], 0.4% [5], 1% [32], 4% [28,31], and 7.5% [33]. A total of 20 studies out of 32 evaluated povidone solution [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] and included 7399 patients: 3638 in the treatment group and 3651 subjects in the control group. The povidone iodine solution was applied at 1% [11,47,52], 5% [41,43,45] or 10% [35,37,38,39,42,44,46,48,50]. Two studies [37,51], in addition to a povidone and a control group, included a third group, in which participants were treated with a saline vaginal solution, for a total of 110 patients. Only one study [53] adopted metronidazole vaginal gel, with 112 patients in the treatment group and 112 in the control group. Vaginal preparation with cetrimide solution was adopted in only one study, with 100 patients in the treatment group and 100 in the control group [54]. The control groups of several studies included no vaginal cleansing or sterile saline solution or placebo vaginal gel.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of trials included in meta-analysis.

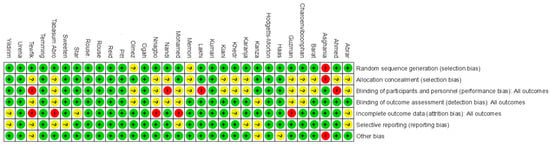

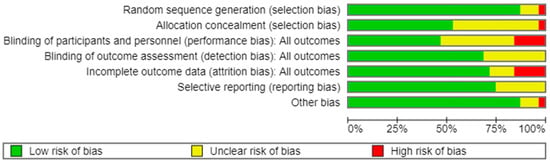

3.3. Risk of Bias of Included Studies

Figure 2 displays the methodological quality of each trial, and a summary of the quality of methodologies, expressed in percentages across all trials, is represented in Figure 3. The majority of the research included presented a low risk of bias. Data about random sequence generation were reported for 28 out of 31 trials.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias: summary. Green (+) indicates low risk of bias, red (−) indicates high risk of bias, and yellow (?) indicates unclear risk of bias.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias: graph. Green indicates low risk of bias, yellow indicates unclear risk of bias, and red indicates high risk of bias.

3.4. Synthesis of Results

3.4.1. Endometritis

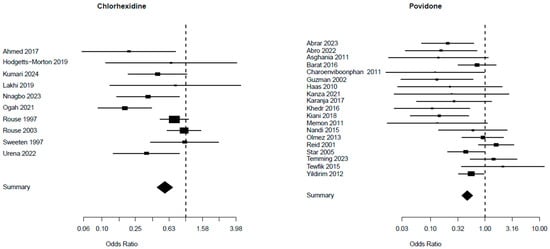

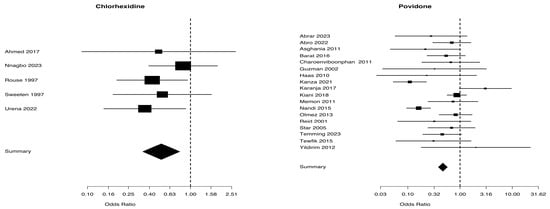

A comparison of the risk of endometritis between the two vaginal solutions (chlorhexidine and povidone) and the control group is presented in Table 2: the chlorhexidine group involved 10 trials with a total of 6230 patients, whereas the povidone group included 19 studies with a total of 7173 patients. The chlorhexidine group presented a Mantel–Haenszel Odds ratio of 0.56 (95% CI 0.45–0.70) and a test of heterogeneity value of 21.63, with a p = 0.010. The Mantel–Haenszel Odds ratio was 0.47 (95% CI = 0.38–0.60) and the test of heterogeneity value was of 41.00, p = 0. 0015, in the povidone group (Figure 4). The I2 values for endometritis were 47.3% in the chlorhexidine group and 54.5% in the povidone group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes analyzed.

Figure 4.

Risk of endometritis from studies [5,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] for chlorhexidine and [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] for povidone.

3.4.2. Maternal Fever

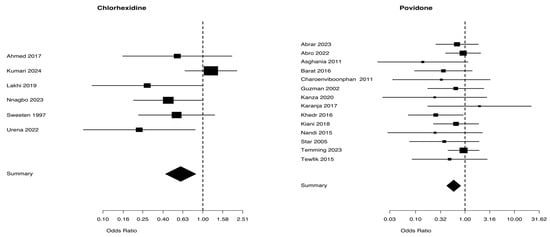

A total of 2598 patients from five studies were included in the chlorhexidine group, whereas 6965 patients from 18 trials were included in the povidone group, considering the difference in maternal fever between the two groups, as shown in Table 2. The Mantel–Haenszel Odds ratio was 0.52 (95% CI 0.34–0.79) and the test of heterogeneity was especially notable at 2.44, with a p-value of 0.656, for the chlorhexidine group. The Mantel–Haenszel Odds ratio was 0.47 (95% CI = 0.38–0.57) and the test of heterogeneity value was of 57.72, p = 0.0001, in the povidone group (Figure 5). The I2 values for maternal fever were 0% in the chlorhexidine group and 70.5% in the povidone group (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Maternal fever from studies [5,25,27,30,31] for chlaorhexidine and [34,35,36,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] for povidone.

3.4.3. Wound Infection

Figure 6 presents a comparison of the use of chlorhexidine and povidone for treating wound infection. The analysis included 3661 patients from 6 trials in the chlorhexidine group and 4797 patients from 14 trials in the povidone group. The Mantel–Haenszel Odds ratio was 0.6 (95% CI 0.42–0.98) and the test of heterogeneity value was especially notable at 9.28, p = 0.098, for the chlorhexidine group. The Mantel–Haenszel Odds ratio was 0.59 (95% CI = 0.42–0.82) and the test of heterogeneity value was of 9.39, p = 0.743, in the povidone group. The I2 values for wound infection were 46.1% in the chlorhexidine group and 0.0% in the povidone group (Table 2).

Figure 6.

Wound infection from studies [5,25,28,30,31,33] for chlaorhexidine and [35,36,37,38,40,41,43,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] for povidone.

4. Discussion

We conducted an updated meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of vaginal cleansing before cesarean section in reducing postoperative endometritis. Our analysis included 31 randomized controlled trials encompassing 13,627 cesarean sections. Vaginal preparation was found to significantly decrease the risks of endometritis and postoperative fever. Specifically, povidone- and chlorhexidine-based disinfectants notably decreased the likelihood of endometritis. In addition, maternal fever incidence decreased when povidone disinfectants were used; however, a smaller effect was shown in the chlorhexidine group that in the control group. The decreased endometritis, maternal fever, and wound infection incidence indicate that preoperative vaginal cleansing should routinely be adjunct to antibiotic prophylaxis for cesarean section. These findings support the consideration of vaginal antiseptic cleansing as part of a hospital’s perioperative care. In accordance with earlier meta-analyses [16,55,56], our findings indicate reduced post-cesarean infection after vaginal cleansing [16,55,56]. Caissutti et al. [16] demonstrated that vaginal cleansing is effective in decreasing postoperative endometritis, particularly in women who are in labor or have ruptured membranes. Roeckner et al.’s findings showed a reduced rate of endometritis after the application of iodine solution in 22 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [55]. In 2020, the Cochrane Systematic Review analyzed 20 trials and found that preoperative vaginal treatment with antiseptic solutions decreased the occurrence of post-cesarean endometritis from 7.1% to 3.1% [11]. Both iodine- and chlorhexidine-based solutions were effective in this reduction [11]. A recent meta-analysis by Liu et al. including 23 trials with 10,026 cesarean delivery patients concluded that preoperative vaginal preparation can significantly reduce the risk of post-cesarean infectious diseases (endometritis, postoperative fever, and wound infection); the results produced by 1% povidone vaginal solution were especially significant [56].

Our meta-analysis did not find a significant reduction in wound infection after vaginal cleansing, while Roeckner et al. and Liu et al. discovered a statistically significant decrease in wound infection with only the use of povidone solution [55,56]. The effectiveness of cetrimide and metronidazole as vaginal disinfectants before cesarean delivery shows varying results and a significant absence of comprehensive information. One RCT found that using cetrimide as an antiseptic for vaginal cleansing before a cesarean section reduced postpartum morbidities like fever and endometritis but did not decrease postoperative wound infections [54]. However, the data is limited, as the analysis only included one trial with 200 women [54]. In the case of metronidazole, a study involving a total of 224 patients found that of those who had received metronidazole, 7% developed post-cesarean endometritis, compared 17% of those who had received the placebo gel [53]. Administering 5 g of intravaginal metronidazole gel before surgery may decrease the occurrence of post-cesarean endometritis. This trial including only 224 women showed an OR of 1.70 for metronidazole gel in preventing wound infection [53]. Finally, a cost analysis of possible approaches applied in clinical practice for vaginal cleansing reported that the application of povidone iodine or chlorhexidine represented a low-cost intervention, and it appears to be applicable in all clinical settings [57].

The prevalence of scientific articles related to vaginal cleansing and the prevention of post-cesarean endometritis has increased substantially in recent years. The interest in this topic can be ascribed to various elements, including the cost-efficiency and effectiveness of pre-operative vaginal cleansing. The first strength of our meta-analysis is related to the number of patients included (13,627 patients) and the high number of RTCs included compared to the most recent meta-analysis by Liu et al. [56]. Second, we conducted an extensive systematic review of the literature, including the gray literature, to reduce selection bias. Third, we conducted a comprehensive analysis that included not only post-cesarean endometritis. Our meta-analysis has different limitations that mainly result from the difficulties in handling potential confounding variables and selection biases that are present in the included RCTs. Another significant limitation is the absence of stratification in subgroup analysis. Several trials involved both intrapartum and elective cesarean births, including events with ruptured and intact membranes, without specific subgroup analyses. The absence of stratification may obscure significant variations in outcomes across these various clinical settings. In addition, the lack of adjunctive data, such as serological markers, limits the accuracy of the outcome evaluation. The majority of the RCTs included in this meta-analysis did not compare multiple treatments, which represents a limitation. In addition, the socio-economic status of pregnant patients, the characteristics of the population under investigation, and the technique of placental removal, in addition to the timing and types of antibiotics administered, exhibited variation among the included studies. This variability may have a substantial impact on the results of the meta-analysis. Finally, the current comprehension of the vaginal cleansing effect is significantly limited by the absence of comprehensive research on the microbiome, specifically how it is altered after cleansing. It has been hypothesized that vaginal cleansing decreases vaginal bacteria, which reduces postoperative endometritis incidence. Nevertheless, the overall impact on the vaginal microbiota remains partially unknown. Additional research to examine the vaginal microbiome following vaginal cleaning is needed. This research is crucial for comprehending the complete range of its effects, including any possible long-term repercussions on the vaginal flora. Insufficient data necessitates a thorough evaluation of the benefits and drawbacks of vaginal cleansing prior to cesarean delivery.

5. Conclusions

This meta-analysis comprehensively examined the efficacy of combining vaginal cleansing with prophylactic antibiotics in the prevention of post-cesarean endometritis. The integration of data from multiple randomized trials provided a robust framework for assessing this intervention. Our findings underscore the necessity for further investigation across all vaginal disinfectant solution and procedures that can reduce post-cesarean infective complications.

Author Contributions

M.L.V. and M.D. conceptualized the study. M.T. and B.G. designed the study. M.L.V., I.I., A.C. and R.M. drafted the initial manuscript. I.I., M.C., L.M. and C.M. designed the data collection instruments and collected data. M.F. performed the initial analyses, M.D. and M.M.M. critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the AI-RITM interdepartmental project for its support in this research, and the Department of Woman, Child and General and Specialized Surgery, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CS | Cesarean Section |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| PICO | Population, Intervention, Control, Outcome |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Detailed search strategy for systematic review.

Table A1.

Detailed search strategy for systematic review.

| Variable | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| Database searched | MEDLINE (accessed through PubMed), Scopus, EMBASE, Google scholar and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) from their origin until 23 January 2024 |

| Search strategy for Pubmed | ((((((Caesarean delivery) OR (cesarean section)) AND (endometritis)) OR (postoperative infection)) OR (fever)) AND (vaginal preparation)) OR (vaginal cleansing) |

| Scopus | ((((((caesarean delivery OR cesarean section) AND endometritis) OR postoperative infection) OR fever) AND vaginal preparation) OR vaginal cleansing) |

| CENTRAL | ((((((caesarean delivery OR cesarean section) AND endometritis) OR postoperative infection) OR fever) AND vaginal preparation) OR vaginal cleansing) |

| Google scholar | (“caesarean delivery” OR “cesarean section”) AND (“vaginal preparation” OR “vaginal cleansing”) AND (endometritis OR “postoperative infection” OR fever) |

| EMBASE | (‘caesarean delivery’/exp OR ‘cesarean section’/exp) AND (‘vaginal preparation’/exp OR ‘vaginal cleansing’/exp) AND (‘endometritis’/exp OR ‘postoperative infection’/exp OR fever/exp) |

| Other sources | The reference lists of selected articles and reviews were hand searched to identify any relevant articles. |

References

- Häger, R.M.; Daltveit, A.K.; Hofoss, D.; Nilsen, S.T.; Kolaas, T.; Øian, P.; Henriksen, T. Complications of cesarean deliveries: Rates and risk factors. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 190, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, I.; Nicholson, W.; Theron, G.; Childbirth, F.; Committee, P.H.; Beyeza, J.; Nassar, A.; Chandran, R.; Riethmuller, D.; Begum, F.; et al. FIGO good practice recommendations on surgical techniques to improve safety and reduce complications during cesarean delivery. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 163, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.S.; Nelson, G.; Wood, S.L.; Metcalfe, A. Surgical errors and complications following cesarean delivery in the United States. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2020, 2, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroz, L.; Wright, J.; Ananth, C.; Friedman, A. Hospital variation in maternal complications following caesarean delivery in the United States: 2006–2012. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 123, 1115–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeten, K.M.; Eriksen, N.L.; Blanco, J.D. Chlorhexidine versus sterile water vaginal wash during labor to prevent peripartum infection. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 176, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNoble, A.E.; Heine, R.P.; Dotters-Katz, S.K. Chorioamnionitis and infectious complications after vaginal delivery. Am. J. Perinatol. 2019, 36, 1437–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, S.A.; Smith, T.; Chang, E.; Hulsey, T.; Vandorsten, J.P.; Soper, D. Administration of cefazolin prior to skin incision is superior to cefazolin at cord clamping in preventing postcesarean infectious morbidity: A randomized, controlled trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 196, 455.e1–455.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelmow, D.; Ruehli, M.S.; Huang, E. Prophylactic use of antibiotics for nonlaboring patients undergoing cesarean delivery with intact membranes: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 184, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, K.E.; Yee, L. Applying surgical antimicrobial standards in cesarean deliveries. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 416.e1–416.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoe, D.S.; Christiansen, C.L.; Johnson, R.; Sands, K.E.; Livingston, J.; Shtatland, E.S.; Platt, R. Epidemiology of and surveillance for postpartum infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001, 7, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, D.M.; Morgan, S.; Contreras, K.; Kimball, S. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 26, CD007892. [Google Scholar]

- Mackeen, A.D.; Packard, R.E.; Ota, E.; Speer, L. Antibiotic regimens for postpartum endometritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD001067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, D.; Hillier, S.L.; Eschenbach, D.A. Upper genital tract isolates at delivery as predictors of post-cesarean infections among women receiving antibiotic prophylaxis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1991, 77, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, R.; Blanco, J.; Clair, P.S.; Castaneda, Y. Vaginal colonization with resistant aerobic bacteria after antibiotic therapy for endometritis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1982, 142, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.M.; Blanco, J.D.; Oshiro, B.T.; Magee, K.P.; Monga, M.; Eriksen, N. Single-dose ampicillin prophylaxis does not eradicate enterococcus from the lower genital tract. Obstet. Gynecol. 1993, 81, 115–117. [Google Scholar]

- Caissutti, C.; Saccone, G.; Zullo, F.; Quist-Nelson, J.; Felder, L.; Ciardulli, A.; Berghella, V. Vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 130, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK, National Guideline Alliance. Methods to Reduce Infectious Morbidity at Caesarean Birth; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- NICE Guideline NG192: Caesarean Birth. 2021. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng192 (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Duignan, N.; Lowe, P. Pre-operative disinfection of the vagina. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1975, 1, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haeri, A.; Kloppers, L.L.; Forder, A.A.; Baillie, P. Effect of different pre-operative vaginal preparations on morbidity of patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy. S. Afr. Med. J. 1976, 50, 1984–1986. [Google Scholar]

- Göymen, A.; Şimşek, Y.; Özdurak, H.İ.; Özkaplan, Ş.E.; Akpak, Y.K.; Özdamar, Ö.; Oral, S. Effect of vaginal cleansing on postoperative factors in elective caesarean sections: A prospective, randomised controlled trial. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 30, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, W-65–W-94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbuagbaw, L.; Rochwerg, B.; Jaeschke, R.; Heels-Andsell, D.; Alhazzani, W.; Thabane, L.; Guyatt, G.H. Approaches to interpreting and choosing the best treatments in network meta-analyses. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley-Blackwell: Chicester, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Aref, N.K.; Sayed Ahmed, W.A.; Arain, F.R. Chlorhexidine vaginal wipes prior to elective cesarean section: Does it reduce infectious morbidity? A randomized trial. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 30, 1484–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, D.J.; Hauth, J.C.; Andrews, W.W.; Mills, B.B.; Maher, J.E. Chlorhexidine vaginal irrigation for the prevention of peripartal infection: A placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 176, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouse, D.J.; Cliver, S.; Lincoln, T.L.; Andrews, W.W.; Hauth, J.C. Clinical trial of chlorhexidine vaginal irrigation to prevent peripartal infection in nulliparous women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 189, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhi, N.A.; Tricorico, G.; Osipova, Y.; Moretti, M.L. Vaginal cleansing with chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine prior to cesarean delivery: A randomized comparator-controlled trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2019, 1, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgetts-Morton, V.; Hewitt, C.A.; Wilson, A.; Farmer, N.; Weckesser, A.; Dixon, E.; Brocklehurst, P.; Hardy, P.; Morris, R.K. Vaginal preparation with chlorhexidine at cesarean section to reduce endometritis and prevent sepsis: A randomized pilot trial (PREPS). Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020, 99, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnagbo, E.J.; Obi, N.S.; Umeh, A.U. Effectiveness of Chlorhexidine vaginal cleansing in reducing post-caesarean endometritis at two tertiary hospitals in Enugu, Nigeria: A randomized controlled trial. Trop. Dr. 2023, 53, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urena, N.; Reyes, O. Preoperative vaginal cleansing with chlorhexidine vs. placebo in patients with rupture of membranes: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-control study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2022, 4, 100572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogah, C.O.; Anikwe, C.C.; Ajah, L.O.; Ikeotuonye, A.C.; Lawani, O.L.; Okorochukwu, B.C.; Ikeoha, C.C.; Okoroafor, F.C. Preoperative vaginal cleansing with chlorhexidine solution in preventing post-cesarean section infections in a low resource setting: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Suri, J.; Bharti, R.; Pandey, D.; Bachani, S. Preoperative vaginal cleansing with chlorhexidine and cetrimide solution for reduction of postoperative infectious morbidity at a tertiary care center in North India: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 164, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, D.M.; Pazouki, F.; Smith, R.R.; Fry, A.M.; Podzielinski, I.; Al-Darei, S.M.; Golichowski, A.M. Vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery to reduce postoperative infectious morbidity: A randomized, controlled trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 310.e1–310.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barat, S.; Bouzari, Z.; Ghanbarpour, A.; Zabihi, Z. Impact of preoperative vaginal preparation with povidone iodine on post cesarean infection. Casp. J. Reprod. Med. 2016, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, M.A.; Prien, S.D.; Blann, D.W. Post-cesarean related infection and vaginal preparation with povidone–iodine revisited. Prim. Care Update Ob/Gyns 2002, 9, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, N.F.H.; Fadel, E.A. Effect of prophylactic preoperative nursing interventions on prevention of endometritis among women undergoing elective caesarean delivery. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2016, 6, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, S.A.; Zafar, M.; Yasmin, S.; Mazhar, S.B. Vaginal cleansing prior to cesarean section and post-operative infectious morbidity. J. Soc. Obstet. Gynaecol. Pak. 2018, 8, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, S.; Qazi, R.A.; Bibi, S.; Parveen, N. Effect of preoperative vaginal cleansing with an antiseptic solution to reduce post caesarean infectious morbidity. JPMA-J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2011, 61, 1179. [Google Scholar]

- Karanja, D.M. Effect of Preoperative Vaginal Cleansing with Povidone Iodine on Post-Caesarean Maternal Infections at Kenyatta National Hospital; a Randomized Controlled Trial. Master’s Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nandi, J.; Saha, D.; Pal, S.; Barman, S.; Mitra, A. Antiseptic vaginal preparation before cesarean delivery to reduce post operative infection: A randomised controlled trial. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Res. 2015, 3, 4310–4315. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, V.C.; Hartmann, K.E.; MCMahon, M.; Fry, E.P. Vaginal preparation with povidone iodine and postcesarean infectious morbidity: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 97, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, R.V.; Zurawski, J.; Ismail, M. Preoperative vaginal preparation with povidone-iodine and the risk of postcesarean endometritis. Obs. Gynecol 2005, 105, 1024–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, G.; Güngördük, K.; Asicioğlu, O.; Basaran, T.; Temizkan, O.; Davas, İ.; Gulkilik, A. Does vaginal preparation with povidone–iodine prior to caesarean delivery reduce the risk of endometritis? A randomized controlled trial. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012, 25, 2316–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ölmez, H.; Duğan, N.; Sudolmuş, S.; Fendal Tunca, A.; Yetkin Yıldırım, G.; Gülkılık, A. Does Vaginal Preparation with Povidone-Iodine Prior to Cesarean Delivery Reduce the Risk of Endometritis? Compr. Med. 2013, 5, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewfik, H.; Ibrahim, A.; Hanafi, S.; Fahmy, A.; Khaled, M.A.; Abdelazim, I.A. Preoperative vaginal preparation using povidone iodine versus chlorhexidine solutions in prevention of endometritis in elective cesarean section. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2015, 4, 486–492. [Google Scholar]

- Charoenviboonphan, P. Preoperative vaginal painting with 1% povidone-iodine before cesarean delivery to reduce postoperative febrile morbidity: A randomized control trial. วารสาร แพทย์ เขต 4–5 2011, 30, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Asghania, M.; Mirblouk, F.; Shakiba, M.; Faraji, R. Preoperative vaginal preparation with povidone-iodine on post-caesarean infectious morbidity. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 31, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abro, S.T.; Sohail, F.; Sheikh, E.M.; Kaleem, R.; Fazal, K. Effectiveness of Preoperative Vaginal Cleansing with an Antiseptic Solution among Cesarean Patients: Effectiveness of Vaginal Cleansing among Cesarean Patients. Pak. J. Health Sci. 2022, 3, 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Abrar, S.; Sayyed, E.; Hussain, S.S. Vaginal cleansing before emergency cesarean section and post-operative infectious morbidity; clinical trial in a low resource setting. J. Postgrad. Med. Inst. 2023, 37, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kanza, D. The effect of vaginal cleansing performed with normal saline solution or povidone-iodine before elective caesarean section on postoperative maternal morbidity and infection; A prospective randomized controlled study. Marmara Med. J. 2021, 34, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temming, L.A.; Frolova, A.I.; Raghuraman, N.; Tuuli, M.G.; Cahill, A.G. Vaginal cleansing before unscheduled cesarean delivery to reduce infection: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, 739.e1–739.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, C.; Sanchez-Ramos, L.; Kaunitz, A.M. Adjunctive intravaginal metronidazole for the prevention of postcesarean endometritis: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 98, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.; Hassan, S.; Hemida, R. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for reducing post partum morbidity. OSR-JNHS 2015, 4, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Roeckner, J.T.; Sanchez-Ramos, L.; Mitta, M.; Kovacs, A.; Kaunitz, A.M. Povidone-iodine 1% is the most effective vaginal antiseptic for preventing post-cesarean endometritis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 261.e1–261.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Liang, J.; Bai, L.; Dou, G.; Tan, K.; He, X.; Zhang, J.; Ma, X.; Du, X. Different methods of vaginal preparation before cesarean delivery to prevent postoperative infection: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.; Agarwal, R.K.; Lee, B.Y.; Fishman, N.O.; Umscheid, C.A. Systematic review and cost analysis comparing use of chlorhexidine with use of iodine for preoperative skin antisepsis to prevent surgical site infection. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010, 31, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).