Abstract

Background: Circulating sphingolipids have been implicated in central nervous system degenerative disorders, but their relationship with peripheral neuropathy remains unclear. Objectives: To evaluate associations between plasma sphingolipid levels and subsequent loss of vibration and light pressure sensation in the lower limbs of older adults. Methods: Plasma concentrations of 11 ceramide (Cer) and sphingomyelin (SM) species were measured in stored samples from 4612 participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Vibration sensation was assessed 4–6 years later in 2208 individuals using tuning fork testing, and light pressure sensation was evaluated 11–13 years later in 815 participants using monofilament testing. Sensory impairment was graded on a 3-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater loss. Ordinal logistic regression models examined associations between a doubling of sphingolipid levels and sensory decline, with stratification by diabetes status. Results: In primary models, no sphingolipid species showed significant associations with sensory outcomes. However, after adjusting for inflammatory markers, higher SM-16 levels were linked to increased odds of vibration sensation loss (OR 2.08; 95% CI: 1.11–3.90), while higher SM-24 levels were associated with reduced odds (OR 0.68; 95% CI: 0.46–0.998). Significant interactions with diabetes status were observed for light pressure sensation: SM-14 was associated with increased odds of sensory loss in participants with incident diabetes (OR 5.22; 95% CI: 1.58–17.29), and Cer-18 was associated with increased odds in those with prevalent diabetes (OR 2.38; 95% CI: 1.18–4.78). Conclusions: Elevated levels of specific ceramide and sphingomyelin species may be predictive of future peripheral sensory loss in older adults, with diabetes status influencing these associations.

1. Introduction

Peripheral neuropathy (PN) is a prevalent condition among older adults, with population-based studies indicating that 27–39% exhibit sensory impairments, particularly those with diabetes [1,2]. PN contributes significantly to pain, increased risk of injury and infection, diminished mobility, and elevated mortality rates, independent of diabetes status and traditional cardiovascular risk factors [3].

PN encompasses a group of disorders with multiple etiologies, including metabolic derangements, nutritional insufficiencies, immune-mediated and autoimmune mechanisms, infectious agents, exposure to toxins, and mechanical trauma. Despite diagnostic evaluation, approximately 25% of cases remain idiopathic, underscoring the potential involvement of other pathogenic factors in the development and progression of peripheral nerve dysfunction [4].

Sphingolipids (SLs) constitute approximately 5% of the plasma lipidome and include several hundred species, primarily sphingomyelins (SMs) and a smaller proportion of ceramides (Cers) [5]. These lipids are structural components of cell membranes enabling cells to respond to external stimuli through pathways that regulate apoptosis, inflammation, and stress responses [6]. SL produced inside a cell are incorporated into cell membranes or transported into the circulation via plasma lipoproteins such as apoB or apo-AI [7]. Circulating SLs are synthesized mainly in the liver and their production is influenced by hepatic lipid accumulation, obesity, and insulin resistance [8].

Ceramides are intermediates of SL metabolism which can promote mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines impairing cellular energy metabolism [9]. In contrast, SMs–especially those with very-long-chain fatty acids–help maintain membrane integrity by forming platforms (lipid rafts) that stabilize receptor signaling and protect against cellular stress [10]. Dysregulation of these pathways has been implicated in chronic metabolic disorders, cancer, and cardiovascular disease [11,12,13,14].

Our previous research has linked specific SL species—particularly SM-16 and Cer-16, which contain acylated palmitic acid—to increased risk of all-cause dementia in older adults [15]. These species have also been associated with elevated levels of neurofilament light chain, a marker of axonal injury [16]. Additional studies have implicated SLs in neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory processes, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and psychiatric disorders [17,18,19].

Given the association of SLs with central nervous system disorders, the current study investigates whether circulating plasma SL species are associated with peripheral sensory impairment, specifically vibration and light pressure sensation, in the lower extremities of older adults. We further examine whether these associations are modified by diabetes status.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

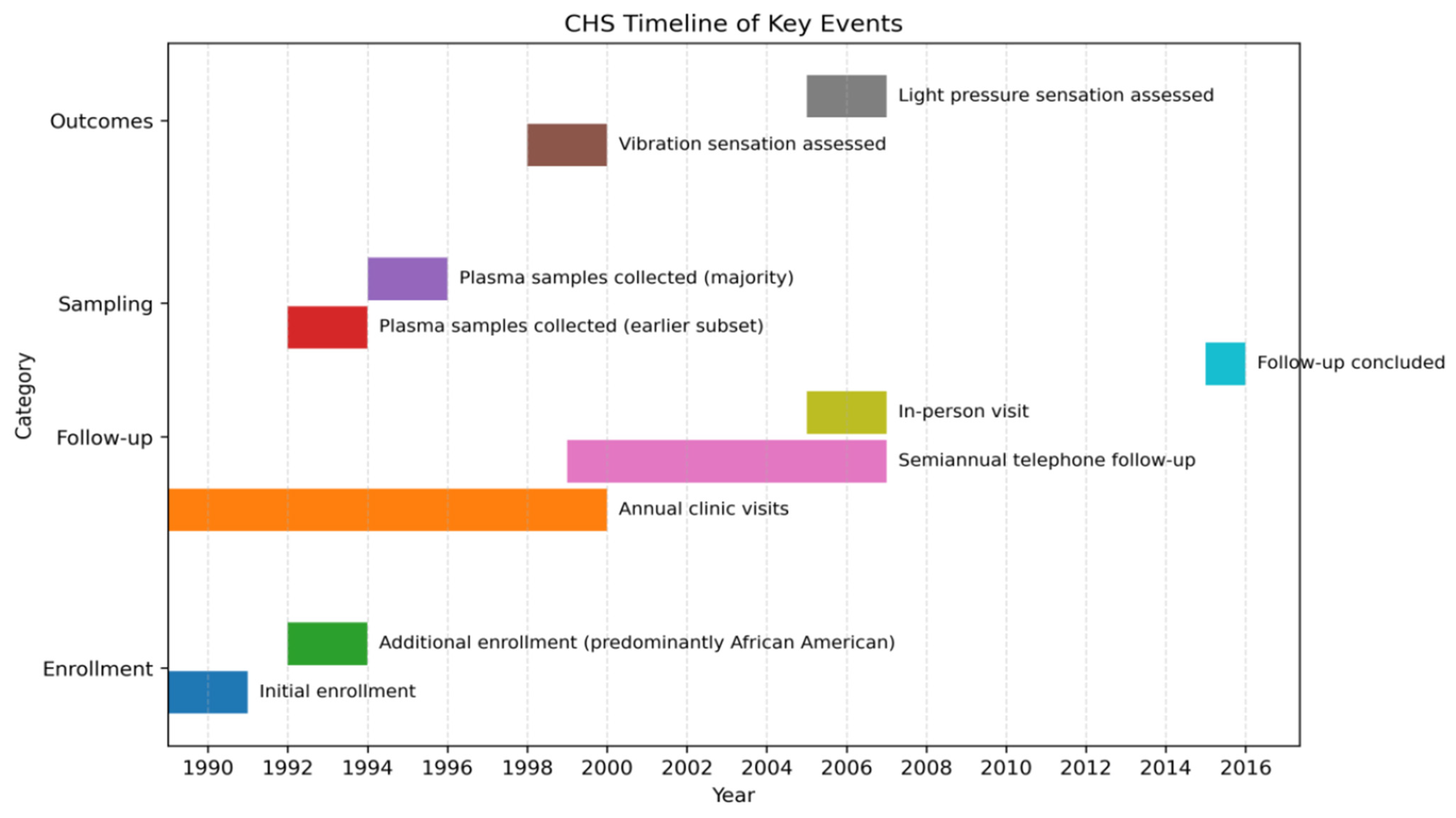

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) is a prospective, community-based cohort study of adults aged 65 years and older, recruited from Medicare eligibility lists in four U.S. communities [20]. Initial enrollment included 5201 participants between 1989 and 1990, followed by an additional 687 predominantly African American participants in 1992–1993. All participants provided informed consent, and institutional review board approval was obtained at each study site. Annual clinic visits were conducted through 1998–1999, with semiannual telephone follow-up thereafter, including an in-person visit in 2005–2006. A timeline of the events of this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of Key Cardiovascular Health Study Events.

2.2. Sphingolipids

Plasma samples were collected from 4612 participants—87.3% during the 1994–1995 visit and 12.7% during the 1992–1993 visit—which served as the baseline for this analysis.

Sphingolipid species containing saturated fatty acid chains were quantified using EDTA plasma stored at −70 °C. Lipid extraction and quantification were performed via liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry [14]. Eleven sphingolipid species were measured: five ceramides (Cer-16, -18, -20, -22, -24) and six sphingomyelins (SM-14, -16, -18, -20, -22, -24). SL levels were assayed in 1996–1997 and have been used in prior CHS studies [13,14,15,16] related to heart disease and cognition.

2.3. Vibration Sensation Testing

In 1998–1999, foreleg vibration sensation was measured. A handheld 128 Hz tuning fork was struck and held sequentially on the left and right big toes. If no vibration was sensed on either side, the process was repeated over the left and right medial malleoli. If no vibration sensation was detected on either side, the process was repeated over the left and right tibial tuberosities. A participant received a value of 1 if vibration was first detected in either big toe; a value of 2 if vibration was first detected in either malleolus but not below; a value of 3 if vibration was first detected in either tibial tuberosity but not below; and a value of 4 if vibration was not perceived in either tibial tuberosity or below. Vibratory sensation was based on the better of the two lower extremities to mitigate unilateral causes of sensory impairment, such as lumbar radiculopathy.

2.4. Pressure Sensation Testing

In 2005–2006, participants were tested for light pressure sensation in the dorsum of the great toe. The response to monofilament testing was classified as: (1) “yes” to 4.17 (1.4 g force) monofilament; (2) “no” to the 4.17 but “yes” to the 5.07 monofilaments; and (3) “no” to both 4.17 and 5.07 monofilaments. “Yes” was defined by feeling the filament in at least 3 of 4 trials with each monofilament.

2.5. Covariates

Factors self-reported at the baseline included age, health (excellent or very good vs. worse), any Activity of Daily Living (ADL) difficulty, smoking status (never, former, current), alcohol consumption (>7 drinks per week), and ever diagnosis of cancer. Race, sex, and education (>12th grade) were self-reported at enrollment into the CHS cohort. Weight was measured at the time of SL blood draw and height and waist circumference were measured in 1992–1993. Diabetes status was a three-level variable defined as: never at the time of sensation testing (never); incident after the time of the SL blood draw and before sensation testing (incident); and prevalent at the time of SL blood draw (prevalent). Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg or use of anti-hypertensive medication along with reports of hypertension. Estimated glomerular filtration based on cystatin C levels (eGFRcyst), C reactive protein (CRP), interleukin 6 (IL-6), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and triglycerides were measured from blood taken at the baseline visit. A history of coronary heart disease (CHD), myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or heart failure (HF) was determined at baseline. ApoE4 genotype was measured from blood drawn at enrollment in CHS. Exercise was assessed by response to the question: “During the last week, about how many city blocks or miles did you walk?” Walking is the predominant form of exercise in the age group of the cohort.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Sphingolipid concentrations were log2-transformed to assess the effect of a doubling in levels. Ordinal logistic regression models evaluated associations between sphingolipid levels and sensory impairment. Due to small sample sizes and proportional odds assumption violations, the most impaired vibration categories were combined. Analyses of SM-14, -16, and -18 were adjusted for SM-22; SM-20, -22, and -24 were adjusted for SM-16, with analogous adjustments for ceramides.

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, field center, and year of blood draw.

Model 2 (primary model) added education, smoking, alcohol use, waist circumference, hypertension, diabetes status, height, ApoE4, and eGFRcyst.

Model 3 further adjusted for inflammatory markers (CRP and IL-6).

Sensitivity analyses included inverse probability weighting (IPW) to account for participant attrition and interaction terms between diabetes status and sphingolipid species. The proportional odds assumption was validated for Model 2. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed p-value < 0.05. No correction for multiple comparisons was applied due to the exploratory nature of the study, so as not to miss a possible significant association. Analyses were conducted using Stata 18.0.

3. Results

Among the 2208 participants who underwent vibration sensation testing, 69.2% demonstrated intact sensation at the toes, 18.2% at the ankles but not below, and 12.7% had diminished sensation at or above the tibial tuberosities. For light pressure sensation testing in 815 participants, 57.9% responded to the 4.17 monofilament, 28.7% to the 5.07 monofilament, and 13.4% failed to respond to either.

The distribution of covariates across quartiles of Cer-16 in participants with vibration sensation testing is shown in Table 1. Compared with the other quartiles, the fourth quartile was characterized by the highest waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, triglyceride and CRP levels; the lowest eGFRcyst levels; the least number of blocks walked in the prior week; and the highest prevalences of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. For the cohort with light pressure sensation testing (Supplemental Table S1) the highest quartile of Cer-16 had the lowest prevalence of self-reported very good or excellent health; the highest prevalence of hypertension; the least number of blocks walked in the prior week; the highest amount of prevalent and incident diabetes; the highest total and LDL-cholesterol and CRP and IL-6 levels; and the lowest eGFR levels.

Table 1.

Baseline descriptive characteristics of participants from the Cardiovascular Health Study with data on vibration sensation by quartile of plasma Ceramide-16 *.

3.1. Vibration Sensation

In primary ordinal logistic regression models, no sphingolipid species were significantly associated with vibration sensation loss (Table 2). However, after adjusting for inflammatory markers (Model 3), higher SM-16 levels were associated with increased odds of vibration loss (OR 2.08; 95% CI: 1.11–3.90), while higher SM-24 levels were linked to reduced odds (OR 0.68; 95% CI: 0.46–0.998).

Table 2.

Odds of loss of one level of vibration sensation associated with a doubling of a SL species and p values.

Sensitivity analyses using inverse probability weighting (IPW) to account for participant attrition revealed a significant association between Cer-16 and vibration loss across all models (Table 3). In Model 3, a doubling of Cer-16 levels was associated with increased odds of vibration impairment (OR 2.14; 95% CI: 1.16–3.93). SM-16 also remained significantly associated with vibration loss in this model (OR 2.46; 95% CI: 1.05–5.76).

Table 3.

Odds of loss of one level of vibration sensation associated with a doubling of a SL species using inverse probability weighting to account for participant attrition from the time of blood draw to the time of vibration testing.

No significant interactions were observed between sphingolipid species and diabetes status in relation to vibration sensation loss.

3.2. Light Pressure Sensation

In both primary and IPW-adjusted models, no sphingolipid species showed significant associations with light pressure sensation loss (Supplemental Tables S2 and S3). However, significant interactions with diabetes status were identified (Table 4). Among participants with incident diabetes, higher SM-14 levels were associated with increased odds of light pressure sensation loss (OR 5.22; 95% CI: 1.58–17.29). For those with prevalent diabetes, higher Cer-18 levels were associated with increased odds of sensory impairment (OR 2.38; 95% CI: 1.18–4.78).

Table 4.

Odds of loss of one level of light pressure sensation in the great toe associated with a doubling of a sphingolipid (SL) species in diabetes categories * calculated from model 2 with the interaction of diabetes and SL species added.

4. Discussion

In this exploratory study of older adults, we examined whether baseline sphingolipid (SL) species predicted future peripheral neuropathy, assessed by vibration and light pressure sensation. In primary models, no SL species were significantly associated with vibration loss. However, after adjusting for inflammatory markers, higher SM-16 levels were linked to increased odds of vibration loss, whereas SM-24 was associated with reduced odds. Sensitivity analyses using inverse probability weighting (IPW), strengthened the SM-16 findings and revealed a significant association between Cer-16 and vibration loss. These results suggest that SM-16 and Cer-16—both derived from palmitic acid—may play a role in sensory loss. Adjustments for CRP and IL-6 amplified these associations, indicating that inflammation may confound or mediate the relationship between these SLs and nerve dysfunction.

For light pressure sensation, no direct associations were observed, even with IPW. However, diabetes status modified the effect of certain SL species: SM-14 was associated with sensory loss in participants with incident diabetes, and Cer-18 in those with prevalent diabetes. These findings, though exploratory, highlight potential metabolic pathways linking SLs, diabetes, and neuropathy. Given multiple comparisons and modest sample sizes, replication in independent cohorts is essential.

The mechanisms relating SLs to PN sensation loss or protection are necessarily speculative in an observational study. Palmitic acid–derived SLs may contribute to neuropathy through pathways involving inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction, all of which impair neuronal energy metabolism [21,22,23,24,25]. Long sensory axons, which convey vibration and light touch sensation, may be sensitive to this disruption. The protective association of SM-24 with vibration sensation may reflect its role in stabilizing membrane integrity and cellular signaling [26,27]. Previous CHS studies have reported similar protective effects of SM species on cognitive decline [15], suggesting shared mechanisms between central and peripheral nervous system health.

Most studies of SL species with nerve function have been done in relation to cognition [15,16,17,18,19]. Only a few studies have examined the association of SL species with diabetic PN, and none with non-diabetic PN. Lopes-Virella et al. investigated the associations between plasma levels of glycosphingolipid species with the presence of symptomatic neuropathy in a type 1 diabetes cohort [28]. Levels of deoxy-C24:0-ceramide, C24:0, and C26:0 ceramide were higher in participants with neuropathy compared to those without neuropathy. In a metabolomic study, Song et al. [29] observed that markers of SL metabolism were related to diabetic PN. Feldman et al. [30] identified 15 metabolomic species, including sphingolipid intermediate product, that differed in diabetic people with and without PN. Other studies have identified phospholipids to be associated with susceptibility to diabetic PN [31,32]. Our findings extend the literature by identifying potential links between SL species and sensory decline independent of diabetes.

Strengths of these analyses include the measurement of SL analytes in a large, well-characterized prospective cohort. The outcomes of vibration and light pressure are complementary to each other and of clinical relevance to older adults. Importantly, the inclusion of participants without diabetes allows for broader generalizability. Limitations of this study include its observational nature, the large number of comparisons, and residual confounding by unmeasured variables, such as vitamin B12 levels. We did not determine when symptoms of PN began, nor did we do electrophysiological studies to detect subclinical nerve dysfunction. The gap of time between obtaining blood samples and sensation testing was long and may have biased the results. Analyses were performed in older adults, and the results may not apply to younger individuals. Finally, we did not have a food frequency questionnaire concurrent with the time of the SL blood draw, thereby preventing assessment of dietary lipid intake (e.g., saturated fatty acids) and its association with circulating SL levels.

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest that specific sphingolipid species may contribute to future peripheral sensory loss in older adults. Associations were strongest for SM-16 and Cer-16 with vibration sensation loss and for SM-14 and Cer-18 in individuals with diabetes. These results highlight potential metabolic pathways underlying PN and warrant further investigation using contemporaneous and repeated measurements to confirm these associations and clarify their clinical implications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biomedicines13122995/s1. Table S1: Characteristics of the Cardiovascular Health Study cohort with light pressure sensation testing by quartile of Ceramide-16 (2005–2006, year 18 of CHS). Table S2: Odds of loss of one level of light pressure sensation in the great toe associated with a doubling of SL species. Table S3: Odds of loss of one level of light pressure sensation associated with a doubling of a SL species using inverse probability.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the research and preparation of the manuscript. J.I.B., R.N.L., W.T.L.J. and K.J.M. helped with the intellectual content, analyses and writing of the paper. T.M.B. did the data analysis. E.S.S. and D.S. critically appraised the manuscript and its contents. A.N.H. performed assays of the sphingolipid levels. R.N.L. obtained funding for the sphingolipid assays and oversaw this project. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by contracts HHSN268201200036C, HHSN268200800007C, HHSN268201800001C, N01HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083, N01HC85086, 75N92021D00006, and grants U01HL080295, U01HL130114, and R01HL172803 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Additional support was provided by R01AG023629 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at CHS-NHLBI.org. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study protocol was reviewed by the Cardiovascular Health Study Publications & Presentations Committee and by the Cardiovascular Health Study Steering Committee. It was approved. Study number 9519, 1 April 2024. All participants provided written informed consent upon study entry.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants gave informed consent prior to study entry.

Data Availability Statement

With approved data distribution agreements and institutional review board approval, the data on which this study was based are available from the CHS Coordinating Center at www.chs-nhlbi.org (accessed on 27 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hicks, C.W.; Wang, D.; Windham, B.G.; Matsushita, K.; Selvin, E. Prevalence of peripheral neuropathy defined by monofilament insensitivity in middle-aged and older adults in two US cohorts. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilay, J.I.; Buzkova, P.; Longstreth, W.T., Jr.; Lopez, O.; Bleich, D.; Siscovick, D.; Newman, A.; Sarma, S.; Mukamal, K.J. The Association of Impaired Vibration Sensation in the Lower limb with Tests of Cognition in Older People. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2025, 54, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, C.W.; Wang, D.; Matsushita, K.; Windham, B.G.; Selvin, E. Peripheral Neuropathy and All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in U.S. Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J.C.; Dyck, P.J. Peripheral Neuropathy: A Practical Approach to Diagnosis and Symptom Management. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelnik, I.D.; Kim, J.L.; Futerman, A.H. The complex tail of circulating sphingolipids in atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. J. Lipid Atheroscler. 2021, 21, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riboni, L.; Viani, P.; Bassi, R.; Prinetti, A.; Tettamanti, G. The role of sphingolipids in the process of signal transduction. Prog. Lipid Res. 1997, 36, 153–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Walsh, M.T.; Hammad, S.M.; Mahmood Hussain, M. Sphingolipids and Lipoproteins in Health and Metabolic Disorders. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 28, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Berrada, S.; Guitton, J.; Tan-Chen, S.; Gyulkhandanyan, A.; Jajduch, E.; He Stunff, H. Circulating Sphingolipids and Glucose Homeostasis: An Update. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 24, 12720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Larrauri, A.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Martín, C.; Gomez-Muñoz, A. The critical roles of bioactive sphingolipids in inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 110475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barisch, C.; Holthuis, J.C.M.; Cosentino, K. Membrane damage and repair: A thin line between life and death. Biol. Chem. 2023, 404, 467–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, S.M.; Lopes-Virella, M.F. Circulating Sphingolipids in Insulin Resistance, Diabetes and Associated Complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, G.; Moorthi, S.; Luberto, C. Role and Function of Sphingomyelin Biosynthesis in the Development of Cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2018, 140, 61–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.N.; Fretts, A.M.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Sitlani, C.M.; McKnight, B.; King, I.B.; Siscovick, D.S.; Psaty, B.M.; Heckbert, S.R.; Mozaffarian, D.; et al. Plasma Ceramides and Sphingomyelins in Relation to Atrial Fibrillation Risk: The Cardiovascular Health Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e012853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.N.; Fretts, A.M.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Sitlani, C.M.; McKnight, B.; King, I.B.; Siscovick, D.S.; Psaty, B.M.; Heckbert, S.R.; Mozaffarian, D.; et al. Plasma Ceramides and Sphingomyelins in Relation to Heart Failure Risk. Circ. Heart Fail. 2019, 12, e005708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseholm, K.F.; Cronjé, H.T.; Koch, M.; Fitzpatrick, A.L.; Lopez, O.L.; Otto, M.C.d.O.; Longstreth, W.T.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Mukamal, K.J.; Lemaitre, R.N.; et al. Circulating sphingolipids in relation to cognitive decline and incident dementia: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Alzheimer’s Dementia: Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2024, 16, e12623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moseholm, K.F.; Horn, J.W.; Fitzpatrick, A.L.; Djoussé, L.; Longstreth, W.T.; Lopez, O.L.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Jensen, M.K.; Lemaitre, R.N.; Mukamal, K.J. Circulating sphingolipids and subclinical brain pathology: The cardiovascular health study. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1385623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, M.D.R.; Jin, H.K.; Bae, J.S. Diverse Roles of Ceramide in the Progression and Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kruining, D.; Luo, Q.; van Echten-Deckert, G.; Mielke, M.M.; Bowman, A.; Ellis, S.; Oliveira, T.G.; Martinez-Martinez, P. Sphingolipids as prognostic biomarkers of neurodegeneration, neuroinflammation, and psychiatric diseases and their emerging role in lipidomic investigation methods. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 159, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Vega, S.; Garcia- Juarez, M.; Camacho-Morales, A. Contribution of ceramides metabolism in psychiatric disorders. J. Neurochem. 2023, 164, 708–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, L.P.; Borhani, N.O.; Enright, P.; Furberg, C.D.; Gardin, J.M.; A Kronmal, R.; Kuller, L.H.; Manolio, T.A.; Mittelmark, M.B.; Newman, A. The Cardiovascular Health Study: Design and rationale. Ann. Epidemiol. 1991, 1, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, A.; Imperlini, E.; Nigro, E.; Montagnese, C.; Daniele, A.; Orrù, S.; Buono, P. Biological and nutritional properties of palm oil and palmitic acid: Effects on health. Molecules 2015, 20, 17339–17361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Feldman, E.L. Insulin resistance in the nervous system. Trends Endocrinol. Metabol. 2012, 23, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czubowicz, K.; Strosznajder, R. Ceramide in the molecular mechanisms of neuronal cell death. The role of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Mol. Neurobiol. 2014, 50, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbecki, J.; Bajdak-Rusinek, K. The effect of palmitic acid on inflammatory response in macrophages: An overview of molecular mechanisms. Inflamm. Res. 2019, 68, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, B.; Lee, H.K.; Querfurth, H.W. Oleate prevents palmitate-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, insulin resistance and inflammatory signaling in neuronal cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, A.E.; Smith, D.A.; Hooper, N.M. Sphingomyelin chain length influences the distribution of GPI-anchored proteins in rafts in supported lipid bilayers. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2007, 24, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milhas, D.; Clarke, C.J.; Hannun, Y.A. Sphingomyelin metabolism at the plasma membrane: Implications for bioactive sphingolipids. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, S.M.; Baker, N.L.; El Abiad, J.M.; Spassieva, S.D.; Pierce, J.S.; Rembiesa, B.; Bielawski, J.; Lopes-Virella, M.F.; Klein, R.L.; DCCT/EDIC Group of Investigators. Increased Plasma Levels of Select Deoxy-ceramide and Ceramide Species are Associated with Increased Odds of Diabetic Neuropathy in Type 1 Diabetes: A Pilot Study. Neuromolecular Med. 2017, 19, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Han, R.; Yin, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Bai, J.; Guo, M. Sphingolipid metabolism plays a key role in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Metabolomics 2022, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumora, A.E.; Guo, K.; Alakwaa, F.M.; Andersen, S.T.; Reynolds, E.L.; Jørgensen, M.E.; Witte, D.R.; Tankisi, H.; Charles, M.; Savelieff, M.G.; et al. Plasma lipid metabolites associate with diabetic polyneuropathy in a cohort with type 2 diabetes. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2021, 8, 1292–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshinnia, F.; Reynolds, E.L.; Rajendiran, T.M.; Soni, T.; Byun, J.; Savelieff, M.G.; Looker, H.C.; Nelson, R.G.; Michailidis, G.; Callaghan, B.C.; et al. Serum lipidomic determinants of human diabetic neuropathy in type 2 diabetes. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2022, 9, 1392–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Q.; Qiao, H.; Yin, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Shao, X. Causal relationships between plasma lipidome and diabetic neuropathy: A Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 15, 1398691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).