Hyperglycemia Impairs the Expression of Mediators of Axonal Regeneration During Diabetic Wound Healing in Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tissue Collection and Processing

2.2. Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

2.3. Trichrome Staining

2.4. Immunostaining

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

2.6. Cell Culture and In Vitro Studies

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

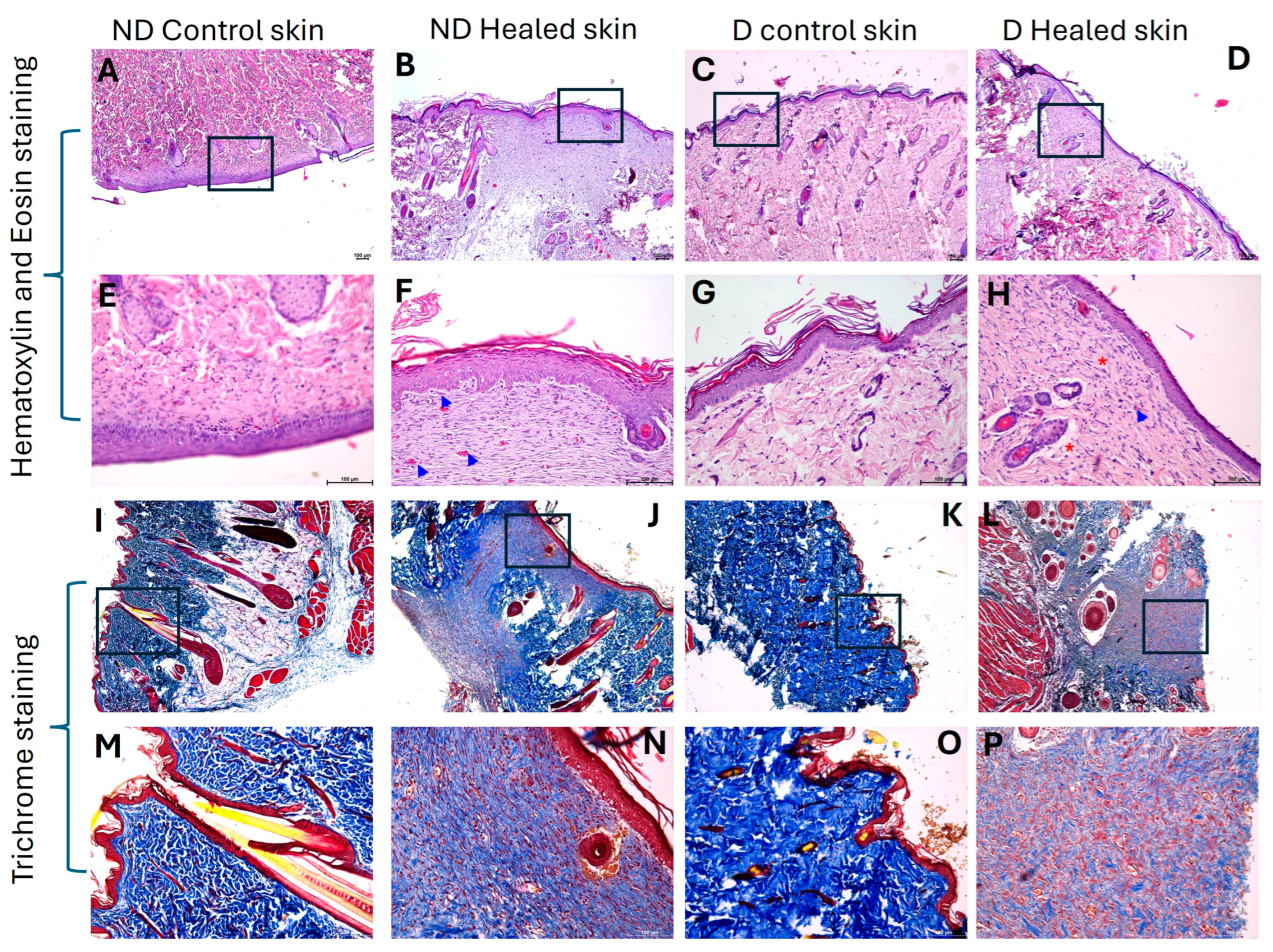

3.1. Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining Showed Healing with Scar

3.2. Trichrome Staining Revealed Decreased Collagen in Diabetic Healed Tissue

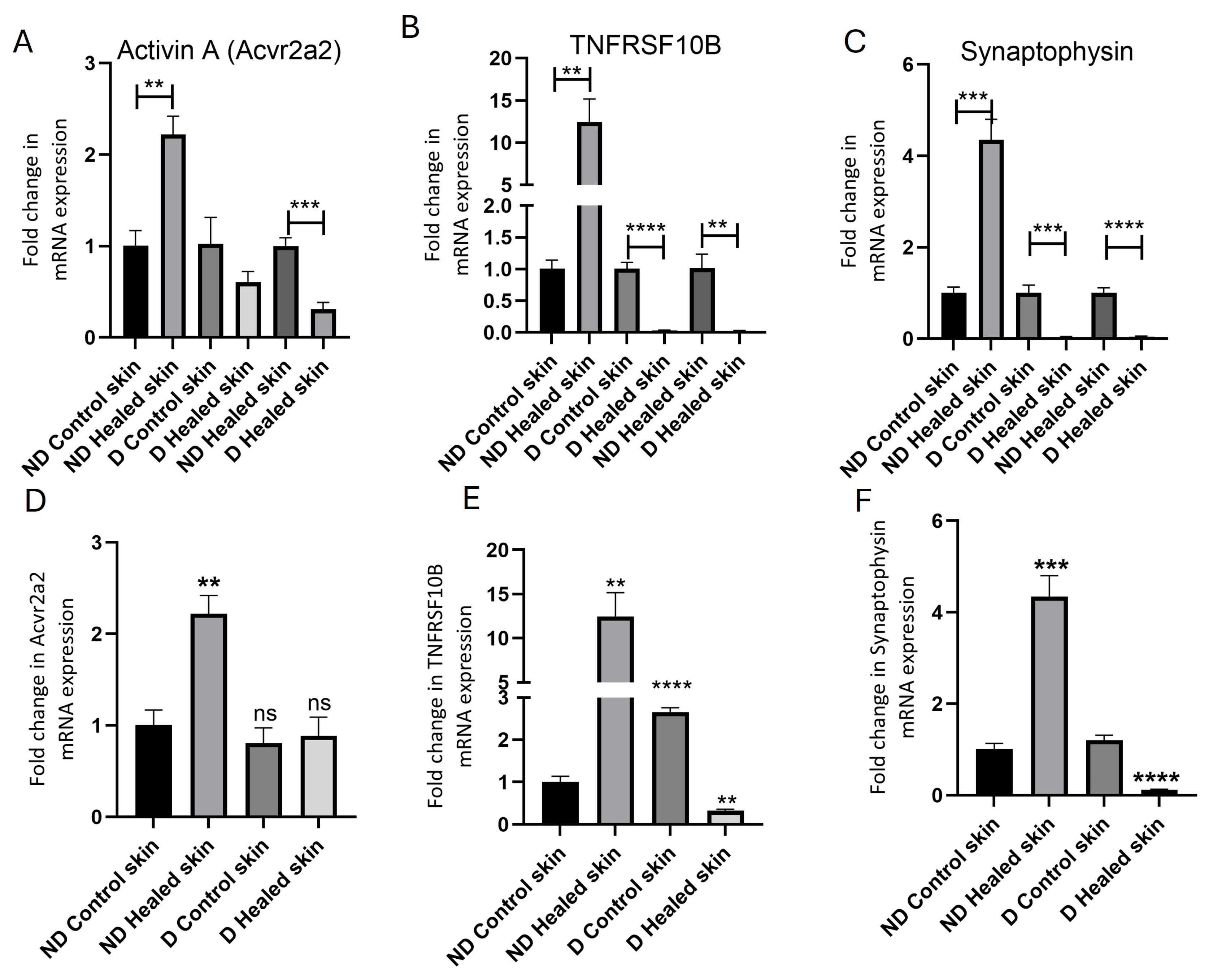

3.3. Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

3.4. Immunohistochemistry

3.5. In Vitro Studies Revealed Effects of Hyperglycemia on the Expression of Activin A and TNFRSF10B

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNA | Central nervous system |

| DFU | Diabetic foot ulcer |

| DR5 | Death Receptor 5 |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NFG | Nerve growth factor |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa beta |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| TRAIL | TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand |

| TNFRSF10B | Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Superfamily, Member 10B |

References

- Sapra, A.; Bhandari, P.; Wilhite Hughes, A. Diabetes (nursing); StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, K.; Fang, M.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Selvin, E.; Hicks, C.W. Etiology, Epidemiology, and Disparities in the Burden of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, H.; Huang, S. Role of NGF and its receptors in wound healing (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Chen, B.; Qin, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, S.; Yuan, K.; Zhao, R.; Qin, D. The role of neuropeptides in cutaneous wound healing: A focus on mechanisms and neuropeptide-derived treatments. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1494865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, K.; Matsuda, H. Nerve growth factor and wound healing. Prog. Brain Res. 2004, 146, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Song, B.; Zhu, Y.; Dang, J.; Wang, T.; Song, Y.; Shi, Y.; You, S.; Li, S.; Yu, Z.; et al. Peripheral nerve-derived CSF1 induces BMP2 expression in macrophages to promote nerve regeneration and wound healing. NPJ Regen. Med. 2024, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerson, E. Efficient Healing Takes Some Nerve: Electrical Stimulation Enhances Innervation in Cutaneous Human Wounds. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 543–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yan, L.; Li, Y.; Guo, H.; Su, W.; Wang, H.; Ni, D. Recovering skin-nerve interaction by nanoscale metal-organic framework for diabetic ulcers healing. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 42, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littig, J.P.B.; Moellmer, R.; Estes, A.M.; Agrawal, D.K.; Rai, V. Increased Population of CD40+ Fibroblasts Is Associated with Impaired Wound Healing and Chronic Inflammation in Diabetic Foot Ulcers. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, V.; Moellmer, R.; Agrawal, D.K. The role of CXCL8 in chronic nonhealing diabetic foot ulcers and phenotypic changes in fibroblasts: A molecular perspective. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 1565–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shofler, D.; Rai, V.; Mansager, S.; Cramer, K.; Agrawal, D.K. Impact of resolvin mediators in the immunopathology of diabetes and wound healing. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 17, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, C.J.; Cullen, S.P.; Tynan, G.A.; Henry, C.M.; Clancy, D.; Lavelle, E.C.; Martin, S.J. Necroptosis suppresses inflammation via termination of TNF- or LPS-induced cytokine and chemokine production. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 1313–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, M.; Yan, L.; Yu, H.; Chen, C.; Xie, Y. TNFRSF10B is involved in motor dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease by regulating exosomal alpha-synuclein secretion from microglia. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2023, 129, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, A.M.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Bai, J.; Mifflin, R.C.; Ernst, P.B.; Mitra, S.; Crowe, S.E. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha-induced IL-8 expression in gastric epithelial cells: Role of reactive oxygen species and AP endonuclease-1/redox factor (Ref)-1. Cytokine 2009, 46, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, D. TRAIL receptor mediates inflammatory cytokine release in an NF-kappaB-dependent manner. Cell Res. 2009, 19, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Guo, S.; Meng, Z.; Gan, H.; Wu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S.; Dou, G.; Gu, R. Advances in the study of death receptor 5. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1549808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiu, G.; He, Z. Glial inhibition of CNS axon regeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, D.; Xia, Y.; Ding, Z.; Qian, J.; Gu, X.; Bai, H.; Jiang, M.; Yao, D. Inflammation in the Peripheral Nervous System after Injury. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omura, T.; Omura, K.; Tedeschi, A.; Riva, P.; Painter, M.W.; Rojas, L.; Martin, J.; Lisi, V.; Huebner, E.A.; Latremoliere, A.; et al. Robust Axonal Regeneration Occurs in the Injured CAST/Ei Mouse CNS. Neuron 2015, 86, 1215–1227, Erratum in Neuron 2016, 90, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Yin, Z.; Huang, R.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Song, S.; Wang, Z.; He, X.; Bai, Y.; et al. Activin A enhances neurofunctional recovery following traumatic spinal cord injury by inhibiting autophagy. Neural Regen. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudi, V.; Gai, L.; Herder, V.; Tejedor, L.S.; Kipp, M.; Amor, S.; Suhs, K.W.; Hansmann, F.; Beineke, A.; Baumgartner, W.; et al. Synaptophysin Is a Reliable Marker for Axonal Damage. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 76, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiya, K.; Kubo, T. Neurovascular interactions in skin wound healing. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 125, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malicevic, U.; Smith, J.; Agrawal, D.K.; Rai, V. Sex-based differences in streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetes rat models. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2025, 025170020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangkrama, M.; Wietecha, M.; Werner, S. Wound Repair, Scar Formation, and Cancer: Converging on Activin. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antsiferova, M.; Werner, S. The bright and the dark sides of activin in wound healing and cancer. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 3929–3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, S.; Ding, F.; He, Q. Activin A Secreted From Peripheral Nerve Fibroblasts Promotes Proliferation and Migration of Schwann Cells. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 859349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, G.O.; Ueland, T.; Knudsen, E.C.; Scholz, H.; Yndestad, A.; Sahraoui, A.; Smith, C.; Lekva, T.; Otterdal, K.; Halvorsen, B.; et al. Activin A levels are associated with abnormal glucose regulation in patients with myocardial infarction: Potential counteracting effects of activin A on inflammation. Diabetes 2011, 60, 1544–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.S.; Lu, Y.W.; Hsu, C.Y.; Chang, C.C.; Chou, R.H.; Liu, L.K.; Chen, L.K.; Huang, P.H.; Chen, J.W.; Lin, S.J. Increased activin A levels in prediabetes and association with carotid intima-media thickness: A cross-sectional analysis from I-Lan Longitudinal Aging Study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Nam, K.M.; Choi, H.R.; Huh, C.H.; Park, K.C. Interactive Roles of Activin A in Epidermal Regeneration. Ann. Dermatol. 2018, 30, 755–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaden, B.C.; Wang, Y.X.; Wilson, J.M.; Culver, A.E.; Milner, A.; Datta-Mannan, A.; Shetler, P.; Croy, J.E.; Dai, G.; Krishnan, V. Inhibition of activin A ameliorates skeletal muscle injury and rescues contractile properties by inducing efficient remodeling in female mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2014, 184, 1152–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latres, E.; Mastaitis, J.; Fury, W.; Miloscio, L.; Trejos, J.; Pangilinan, J.; Okamoto, H.; Cavino, K.; Na, E.; Papatheodorou, A.; et al. Activin A more prominently regulates muscle mass in primates than does GDF8. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valtorta, F.; Pennuto, M.; Bonanomi, D.; Benfenati, F. Synaptophysin: Leading actor or walk-on role in synaptic vesicle exocytosis? Bioessays 2004, 26, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okajima, S.; Mizoguchi, A.; Masutani, M.; Tomatsuri, M.; Tamai, K.; Hirasawa, Y.; Ide, C. Synaptophysin immunocytochemistry in the regenerating sprouts from the nodes of Ranvier in injured rat sciatic nerve. Brain Res. 1993, 631, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Warn, J.D.; Fan, Q.; Smith, P.G. Relationships between nerves and myofibroblasts during cutaneous wound healing in the developing rat. Cell Tissue Res. 1999, 297, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Q.; Jin, A.; Cui, M.; Liu, X. E3 ubiquitin ligase Siah-1 downregulates synaptophysin expression under high glucose and hypoxia. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2015, 7, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, J.W.; Kan, B.H.; Shi, H.Y.; Yang, L.P.; Liu, X.Y. Acupuncture accelerates neural regeneration and synaptophysin production after neural stem cells transplantation in mice. World J. Stem Cells 2020, 12, 1576–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.L.; Thams, S.; Lidman, O.; Piehl, F.; Hokfelt, T.; Karre, K.; Linda, H.; Cullheim, S. A role for MHC class I molecules in synaptic plasticity and regeneration of neurons after axotomy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17843–17848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokotos, A.C.; Harper, C.B.; Marland, J.R.K.; Smillie, K.J.; Cousin, M.A.; Gordon, S.L. Synaptophysin sustains presynaptic performance by preserving vesicular synaptobrevin-II levels. J. Neurochem. 2019, 151, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, M.A.; Grisanti, L.A. A Dual Role for Death Receptor 5 in Regulating Cardiac Fibroblast Function. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 699102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Hu, J.; Su, H.; Yu, Q.; Lang, Y.; Yang, M.; Fan, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhao, Y.; et al. TRAIL induces podocyte PANoptosis via death receptor 5 in diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2025, 107, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, H.; Cheng, J.; Willicut, A.; Dell, G.; Breckenridge, J.; Culberson, E.; Ghastine, A.; Tardif, V.; Herro, R. TNF superfamily control of tissue remodeling and fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1219907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|

| Activin A | Forward: 5′-GGGGATTGTCATTTGTGCGT-3′ Reverse: 5′-GTGGTCCAGGGTCCTGAGTA-3′ |

| TNFRSF10B | Forward: 5′-CCAGGATAGCCTACAACTCAAG-3′ Reverse: 5′-AGGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGA-3′ |

| Synaptophysin | Forward: 5′-ACTTTCTCTCCTTCCTCCTCTC-3′ Reverse: 5′-TCCACTCAGTCTACTGCTCTAC-3′ |

| 18S | Forward: 5′-GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT-3′ Reverse: 5′-CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patel, J.; Ho, V.; Tran, T.; Teshome, B.; Rai, V. Hyperglycemia Impairs the Expression of Mediators of Axonal Regeneration During Diabetic Wound Healing in Rats. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2994. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122994

Patel J, Ho V, Tran T, Teshome B, Rai V. Hyperglycemia Impairs the Expression of Mediators of Axonal Regeneration During Diabetic Wound Healing in Rats. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2994. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122994

Chicago/Turabian StylePatel, Jaylan, Vy Ho, Tommy Tran, Betelhem Teshome, and Vikrant Rai. 2025. "Hyperglycemia Impairs the Expression of Mediators of Axonal Regeneration During Diabetic Wound Healing in Rats" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2994. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122994

APA StylePatel, J., Ho, V., Tran, T., Teshome, B., & Rai, V. (2025). Hyperglycemia Impairs the Expression of Mediators of Axonal Regeneration During Diabetic Wound Healing in Rats. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2994. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122994