Abstract

Background/Objectives: As bioactive extracellular vesicles, exosomes participate in cellular communication and disease mechanisms, yet their structural complexity continues to challenge standard analytical methodologies. This review summarizes published studies reporting exosome concentrations in human plasma, serum, and platelet-rich plasma from healthy individuals and highlights methodological differences. Methods: A comprehensive PubMed search (1986–31 August 2025) was performed using terms related to exosomes and their quantification, excluding cancer- and disease-related studies. Eligible articles reported exosome concentrations in plasma, serum, or platelet-rich plasma using particle-counting techniques such as nanoparticle tracking analysis, flow cytometry, or tunable resistive pulse sensing. Results: Twenty-two articles, including 167 healthy donors, met the inclusion criteria. The following mean concentration ranges were reported: plasma (n = 18), ranged from 4.50 × 108 to 6.70 × 1011 particles/mL with differences by quantification method; serum (n = 10), from 5.30 × 108 to 2.13 × 1011 particles/mL; non-activated platelet-rich plasma (n = 1), 7.52 × 109 particles/mL; activated platelet-rich plasma (n = 3), 4.87 × 1010 to 7.16 × 1010 particles/mL; and preconditioned platelet-rich plasma with photothermal biomodulation (n = 2), 2.53 × 1011 to 2.99 × 1011 particles/mL. Conclusions: Isolation and quantification methods exhibit high variability, which strongly influences the overall quantity and quality of the exosomes obtained. Characteristics, including cargo composition, purity, and exosome integrity, must be considered when developing validated methods. Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that PTBM preconditioning can increase exosome release from cells. In summary, rigorous standardization of protocols is essential to advance the scientific understanding and the clinical potential of exosome-based therapies.

1. Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are spherical phospholipid bilayers ranging in size from 30 to 2000 nm [1]. Nearly all cell types secrete EVs, which are found in most biological fluids, including blood, urine, saliva, breast milk, bronchial lavage, cerebrospinal fluid, and amniotic fluid [2]. EVs can be categorized into exosomes, microvesicles (MVs), and apoptotic bodies based on size, origin, composition, and function [3]. Exosomes participate in both normal biological functions and disease, directly contributing to processes such as cell communication [4], immune response [5], and tumor dissemination [1].

Exosomes contain bioactive substances, including proteins, lipids, and genetic information, such as mRNA and non-coding ribonucleic acids (RNAs), including microRNAs (miRNAs), and their outer layers display additional proteins [6]. The process of biogenesis and exosome delivery occurs when multivesicular bodies fuse with the plasma membrane [7]. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism underlying this process remains unclear [8]. Exosome release is influenced by several physical and chemical factors, as well as cellular conditions, including lipopolysaccharide, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interferon-gamma, low oxygen levels, calcium, exposure to chemotherapy drugs, temperature, and oxidative stress [9].

1.1. Exosome Clinical Applications

Due to their biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, and ability to cross the blood–brain barrier [10], exosomes have garnered significant interest for clinical applications [11,12]. One of the principal areas of research is for regenerative medicine, where promising outcomes have been reported in tissue repair and regeneration [13], including in cancer [14], orthopedics [15], lung regenerative medicine [16], ophthalmology [17], hair regeneration [18], and brain disorders [19]. Exosomes also hold potential for diagnosis and prognosis in cancer [20], cardiovascular [21], neurological [22], autoimmune [23], and infectious diseases [24], through minimally invasive procedures [25]. Moreover, their ability to deliver specific biomarker cargo and modulate immune responses makes them potential therapeutic agents [10,26]. Exosomes can deliver targeted therapeutics to specific cells or tissues, overcoming the limitations of traditional delivery methods [27]. For instance, they are being explored for the development of exosome-based vaccines [28].

Despite these advances, several challenges remain. Key issues include optimizing isolation and purification methods, as well as concerns about the stability and bioavailability of exosomal cargo [11,12]. In addition, the regulatory environment related to exosome-based diagnostics and therapeutics is still evolving [29].

Given these considerations, accurate detection and quantification are essential. However, their complexity in size and structure poses a challenge even for gold-standard methodologies. Variability in isolation and RNA purification techniques often results in inconsistent data, hindering the comparability of findings across studies [2].

1.2. Exosome Isolation Methods

The current methods for exosome isolation include ultracentrifugation (UC), ultrafiltration (UF), precipitation, immunoaffinity-based capture (IAC), and microfluidic techniques.

Ultracentrifugation (UC): UC separates exosomes from biological samples based on size and density through sequential centrifugation. Initial low-speed spins remove cells and debris, followed by ultracentrifugation (>100,000× g) to pellet exosomes for further analysis [30].

Ultrafiltration (UF): UF uses membranes with defined pore sizes to isolate exosomes based on size. Typically, larger pores remove debris, while smaller ones (50–200 nm) retain exosomes and exclude smaller molecules [31].

Precipitation: This technique uses polymers, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), to reduce exosome solubility, thereby inducing aggregation. After incubation at 4 °C, exosomes are collected by low-speed centrifugation [32].

Immunoaffinity-based capture (IAC): IAC uses antibodies targeting specific exosomal surface proteins, enabling selective, high-purity isolation of cell type-specific subsets, including tumor-derived exosomes [30].

Microfluidic techniques: These methods isolate exosomes based on size, affinity, or a combination of both. Size-based isolation includes techniques such as microfiltration, which uses micropores to separate larger particles from exosomes; size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), which separates exosomes by passing them through a microfluidic channel; and viscoelasticity, which utilizes the elastic properties of a fluid to separate particles, pushing larger debris away from exosomes [33].

1.3. Exosome Quantification Methods

The primary methods for a rapid and efficient quantification of exosomes include nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), flow cytometry (FCM), tunable resistive pulse sensing (TRPS), electron microscopy, dynamic light scattering (DLS), microfluidics-based detection, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and the single-particle interferometric reflectance imaging sensor (SP-IRIS).

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA): NTA quantifies exosomes by tracking their Brownian motion in a laser-illuminated liquid sample. Scattered light is recorded, and software calculates particle size and concentration based on individual trajectories [34].

Flow cytometry (FCM): FCM analyzes fluorescent-labeled exosomes and microvesicles using specialized flow cytometers, enabling multiparametric detection and quantification [35].

Tunable resistive pulse sensing (TRPS): TRPS measures changes in electrical resistance as individual exosomes pass through a nanopore, enabling determination of particle size, concentration, and charge [36].

Electron microscopy (EM): EM, especially transmission electron microscopy (TEM), provides a high-resolution image to count individual vesicles and assess their morphology. TEM confirms sample purity and structural integrity. To improve its effectiveness, it is often used in conjunction with other techniques, such as NTA or FCM, which provide population-level quantification [36].

Dynamic light scattering (DLS): DLS quantifies exosomes by illuminating a sample with a laser and measuring fluctuations in scattered light resulting from the Brownian motion of the vesicles [37].

Microfluidics-based detection: Microfluidic devices isolate and analyze exosomes from small liquid samples using integrated on-chip assays. Separation can be performed using SEC, immunoaffinity, or dielectrophoresis, enabling the selective detection of 30–150 nm vesicles [38].

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR): SPR quantifies exosomes by detecting changes in the refractive index when exosomes bind immobilized antibodies [39].

Single-particle interferometric reflectance imaging sensor (SP-IRIS): SP-IRIS quantifies exosomes using a specialized chip with functionalized antibodies to capture individual vesicles from a fluid sample [40].

When selecting an exosome isolation or quantification method, it is essential to consider cost, time required, and the specific advantages and disadvantages of each approach [41]. For example, some methods may include particles in their counts that are not exclusively exosomes, which could affect the accuracy of the results [11]. Some shortcomings of these techniques are outlined in Table 1 [11,32,37,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

Table 1.

Potential disadvantages of exosome isolation and quantification techniques, including the number, integrity, and specificity of the particles obtained.

Aside from the natural biogenesis of exosomes, different methods have been studied to alter their production. These methods are based on electrical stimuli, pharmacological agents, electromagnetic waves, sound waves, shear stress, cell starvation, alcohol, pH, heat, and genetic manipulation [54,55]. However, many of these strategies may alter exosome properties and functionalities, and the exact mechanisms responsible for this increase are generally unknown. Improving exosome production and biological function is critical for promoting their clinical applications.

Given the variability in reported exosome concentrations across studies in human plasma, serum, and platelet-rich plasma from healthy individuals, this review aims to summarize available data and highlight methodological differences that underscore the need for standardized operating procedures (SOPs) and for accurate protocols.

2. Materials and Methods

The literature search was conducted in the PubMed database, covering studies from 1986, when the first article on exosomes in humans was published, to 31 August 2025 (Table 2). Search queries included keywords such as “exosomes” or “extracellular vesicles,” combined with terms like “particles” or “particles/mL” (to identify quantification data), along with “concentration” or “quantification” and sample type descriptors (“plasma,” including platelet-rich plasma, or “serum”). To focus on healthy donors, records associated with terms such as “cancer” or “metastasis” were excluded. Terms were adjusted according to the terminology for this search type, and articles on cancer, diseases, or pregnancy without data from healthy volunteers were excluded. The complete list of search strings and translation into PubMed format is provided in Supplemental Table S1.

Table 2.

PubMed search strategy (1 January 1986–31 August 2025).

After obtaining the search results by term, they were crossed with the search for “exosomes or extracellular vesicles.” Following this search, the database was manually cleaned to remove studies not aligned with the study’s objective. Inclusion criteria were limited to data from human samples from healthy donors with exosome quantification in blood plasma, serum, or PRP, expressed as particles/mL. Following the compilation of articles obtained through the systematic literature review, an additional set of publications was gathered via a targeted Google search to capture relevant works that had not appeared in the initial search.

3. Results

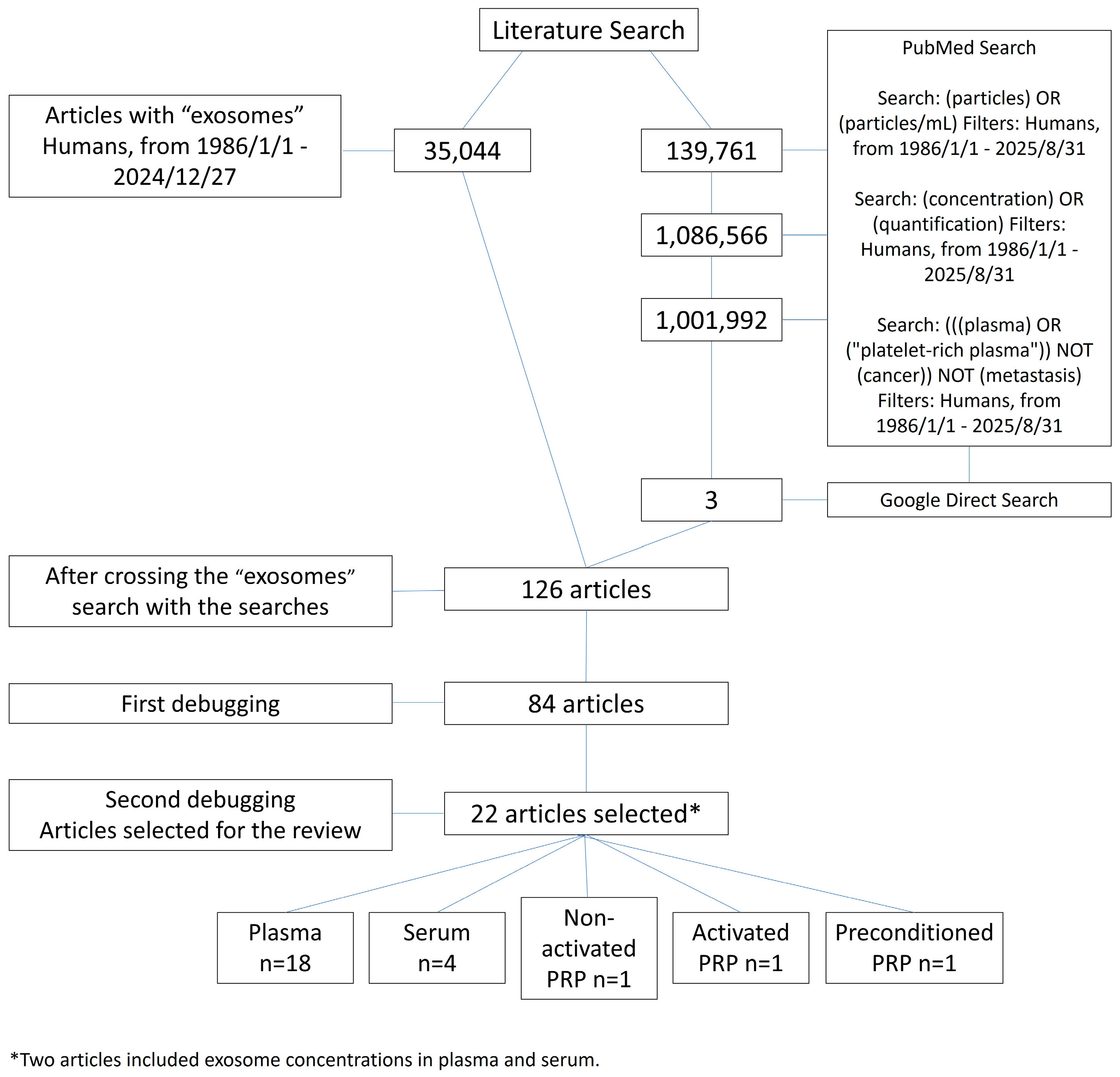

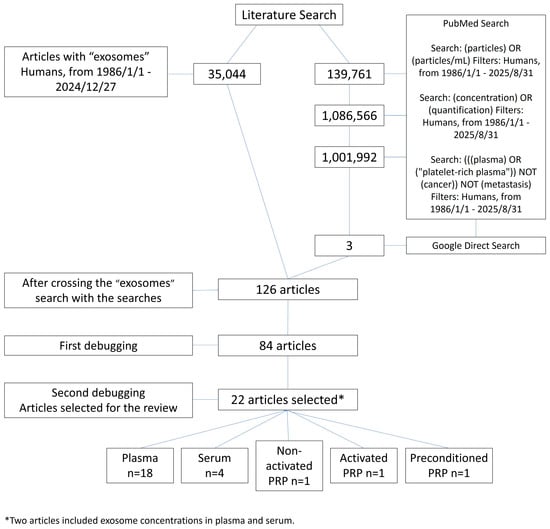

The search for “exosomes” or “extracellular vesicles” yielded 35,044 articles. The details of the search are listed in Supplemental Table S1. After crossing the search results of the terms “serum”, “plasma”, or “platelet-rich plasma”, “concentration”, or “quantification”, and “particles” or “particles/mL” with the search for “exosomes” or “extracellular vesicles”, a total of 126 articles were obtained. In the direct Google search, three articles were included. After removing articles with out-of-scope titles, 84 articles were selected for final review. After the second screening, in which the main text was analyzed in-depth, 22 articles were selected, involving around 167 healthy donors with 29 exosome quantifications in plasma from 18 articles [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73], 10 in serum from 4 articles [60,62,74,75], 1 in non-activated PRP from 1 article [76], 3 in PRP activated with different activators (calcium gluconate, thrombin, and thrombin and calcium gluconate) from 1 article [76], and 2 in preconditioned PRP (blue light 467 nm, 1.0 J/cm2, 37 °C; and blue light 467 nm, 2.0 J/cm2, 37 °C) [77] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature review process used to identify clinical research papers reporting exosome concentrations in plasma, serum, non-activated PRP, activated PRP, and preconditioned PRP.

The mean exosome concentration in plasma ranged from 4.50 × 108 to 6.70 × 1011 particles/mL. Stratified by quantification method, the mean concentration ranged from 3.50 × 106 to 1.50 × 1010 particles/mL for FCM, from 4.50 × 108 to 6.70 × 1011 particles/mL for NTA, and from 9.05 × 108 to 4.36 × 1010 particles/mL for TRPS. In serum, the mean exosome concentration, assessed by NTA, ranged from 5.30 × 108 to 2.13 × 1011 particles/mL. The nanoflow analysis exosome mean concentration was 7.52 × 109 particles/mL for non-activated PRP. For activated PRP samples (including all activation methods—calcium gluconate, thrombin, and thrombin plus calcium gluconate), the exosome mean value ranged from 4.87 × 1010 to 7.16 × 1010 particles/mL, and for preconditioned PRP, it ranged from 2.53 × 1011 to 2.99 × 1011 particles/mL; all were assessed by NTA. Detailed measurement data and study-specific values are provided in Table 3 (plasma), Table 4 (serum), and Table 5 (PRP: activated, non-activated, and preconditioned).

Table 3.

Reported exosome concentrations in human plasma samples from healthy donors.

Table 4.

Reported exosome concentrations in human serum samples from healthy donors.

Table 5.

Data from articles with exosome quantification in human platelet-rich plasma samples from healthy donors.

4. Discussion

Exosome analysis remains challenging [78]. Although concentration is often emphasized, it is not a reliable indicator of exosome quality or biological relevance. Other parameters, such as sample purity, exosome integrity, and the functional significance of the cargo, are likely more critical [79] and vary widely across sample types and methodological approaches. This methodological variability complicates comparisons across studies and underscores the need for SOPs that define not only isolation and quantification strategies but also criteria for assessing exosome quality, ensuring reproducible and meaningful results to support future clinical applications.

Determining the optimal dose of therapeutic EVs is essential to maximize therapeutic effects and support their successful clinical application. Accordingly, dose-definition strategies for therapeutic EVs must consider not only vesicle concentration but also the preparation’s qualitative attributes. Sample parameters to consider include the isolation technique, viscosity, temperature, and the time of day the sample was collected, among others. Moreover, ensuring consistent physiological production and proper storage of exosomes will be critical for future clinical applications, particularly when patient-derived exosome quality or quantity may decline with disease progression.

Existing exosome isolation and quantification methods have advantages, such as high purity (SEC), rapid processing (polymer precipitation, microfluidic techniques), sensitivity (DLS, SPR), and direct counting (NTA, FCM), but also suffer from technical limitations (Table 1) or high cost (IAC, SPR). These limitations may lead to under- or overestimation of counts, or even to accurate counts with exosomes of compromised functional integrity [11]. For instance, in plasma samples, NTA often reports higher counts than TRPS or FCM [80]. Methods such as NTA and FCM count particles, while DLS measures light-scattering intensity. Thus, caution is required when interpreting reports on exosome quantification presented in scientific research or by commercial brands. The ideal standardized isolation method for exosome research and production should be easy and rapid, with high throughput, high purity, high recovery rates, and low procedural cost [30].

One alternative to minimizing quantification variation across studies is to combine different methods to leverage their strengths and mitigate their weaknesses [81]. For example, combining UC with SEC to improve results [82,83]. The combination of various methods can effectively reduce the presence of nanoscale contaminants, thereby improving purity without altering exosomes’ natural properties. Other researchers have proposed new strategies, such as dichotomic size-exclusion chromatography, for exosome isolation, achieving the best performance with higher isolation yields [84]. Exosomes can also be isolated by CD9-HPLC-IAC [85] and untouched isolation [86]. Nevertheless, purity, yield, and recovery remain ongoing challenges, and protocols should preserve exosomes’ native physicochemical environment.

Beyond methodological optimization, exosome production can be enhanced prior to isolation through cell activation or preconditioning techniques, such as photobiomodulation (PBM) and photothermal biomodulation (PTBM). A study on mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exo) confirmed that blue light enhances angiogenesis, likely through modulating specific miRNAs [87]. Regarding preconditioned PRP samples subjected to PTBM, exposure to visible light in the 455–470 nm range (blue light) effectively increases exosome secretion rates [87], aligned with the data obtained from PTBM PRP samples, which exhibited the highest exosome concentrations, particularly compared with activated PRP, the most similar product. This observation is supported by several studies demonstrating that PBM enhances exosome secretion from dermal papillae [88], promotes endothelial cell regeneration [89], and significantly increases EV yield [90]. Cordero et al. reported that a lower fluence (1.0 J/cm2) significantly increased exosome counts [77]. These interventions highlight the potential to maximize yield while preserving vesicle characteristics, although further studies are needed to determine optimal sample types, treatment conditions, and quality control metrics.

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting these findings. First, there are currently no established reference values for exosome concentrations in healthy human plasma, serum, or PRP. Second, the included studies exhibited high heterogeneity in isolation and quantification techniques and sample processing. Moreover, even when the same method, such as ultracentrifugation, is used, the specific protocols differ. This variability complicates direct comparison across studies and may partly explain the wide range of reported exosome counts. Third, the relatively small number of studies, most with limited sample sizes, reduces the robustness and generalizability of the conclusions. Fourth, publication bias cannot be excluded, as studies reporting null or inconsistent results may be underrepresented. Finally, only articles published in English and indexed in PubMed (with complementary Google searches) were included, potentially leading to the omission of relevant studies.

5. Conclusions

Isolation and quantification methods exhibit high variability, which strongly influences the overall quantity and quality of the exosomes obtained. Characteristics, including cargo composition, purity, and exosome integrity, must be considered when developing validated methods. Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that PTBM preconditioning can increase exosome release from cells. In summary, rigorous standardization of protocols is essential to advance the scientific understanding and the clinical potential of exosome-based therapies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biomedicines13122970/s1, Table S1: PubMed strategy searches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: E.S.-V.M., L.C. and H.P.; data acquisition: E.S.-V.M.; analysis: E.S.-V.M.; writing—original draft preparation: E.S.-V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author, E.S.-V.M. on request.

Conflicts of Interest

L.C., E.S.-V.M. and H.P. are members of the Scientific Department at Meta Cell Technology; however, they did not receive any additional fees for conducting this study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| EM | Electron Microscopy |

| FCM | Flow cytometry |

| IAC | Immunoaffinity-based capture |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MSC-Exo | Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome |

| MV | Microvesicle |

| NTA | Nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| PBM | Photobiomodulation |

| PRP | Platelet-rich plasma |

| PTBM | Photothermal biomodulation |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SEC | Size-exclusion chromatography |

| SOPs | Standardized operating procedures |

| SP-IRIS | Single-particle interferometric reflectance imaging sensor |

| SPR | Surface plasmon resonance |

| TRPS | Tunable resistive pulse sensing |

| UC | Ultracentrifugation |

| UF | Ultrafiltration |

References

- Momen-Heravi, F.; Getting, S.J.; Moschos, S.A. Extracellular Vesicles and Their Nucleic Acids for Biomarker Discovery. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 192, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witwer, K.W.; Buzás, E.I.; Bemis, L.T.; Bora, A.; Lässer, C.; Lötvall, J.; Nolte-‘t Hoen, E.N.; Piper, M.G.; Sivaraman, S.; Skog, J.; et al. Standardization of Sample Collection, Isolation and Analysis Methods in Extracellular Vesicle Research. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2013, 2, 20360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.; Wang, M. Overview of Extracellular Vesicles, Their Origin, Composition, Purpose, and Methods for Exosome Isolation and Analysis. Cells 2019, 8, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, C.; Raimondo, S.; Chiesi, A.; Ciccia, F.; De Leo, G.; Alessandro, R. Exosomes as Intercellular Signaling Organelles Involved in Health and Disease: Basic Science and Clinical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 5338–5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrie, A.; Colombo, M.; Raposo, G.; Théry, C. Exosome Secretion: Molecular Mechanisms and Roles in Immune Responses. Traffic 2011, 12, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomar-Alonso, N.; Lee, M.; Kim, M. Exosomes: Membrane-Associated Proteins, Challenges and Perspectives. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 37, 101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, R.M.; Adam, M.; Hammond, J.R.; Orr, L.; Turbide, C. Vesicle Formation during Reticulocyte Maturation. Association of Plasma Membrane Activities with Released Vesicles (Exosomes). J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 9412–9420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Niel, G.; Porto-Carreiro, I.; Simoes, S.; Raposo, G. Exosomes: A Common Pathway for a Specialized Function. J. Biochem. 2006, 140, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.-G.; Wang, J.-L.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Li, L.; Reza, A.M.M.T.; Gurunathan, S. Biogenesis, Composition and Potential Therapeutic Applications of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived Exosomes in Various Diseases. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 3177–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EL Andaloussi, S.; Lakhal, S.; Mäger, I.; Wood, M.J.A. Exosomes for Targeted SiRNA Delivery across Biological Barriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Corbett, A.L.; Taatizadeh, E.; Tasnim, N.; Little, J.P.; Garnis, C.; Daugaard, M.; Guns, E.; Hoorfar, M.; Li, I.T.S. Challenges and Opportunities in Exosome Research—Perspectives from Biology, Engineering, and Cancer Therapy. APL Bioeng. 2019, 3, 011503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, N.; Whiteside, T.L.; Reichert, T.E. Challenges in Exosome Isolation and Analysis in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Takakura, Y. Possibility of Exosome-Based Therapeutics and Challenges in Production of Exosomes Eligible for Therapeutic Application. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 41, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, I.-M.; Rajakumar, G.; Venkidasamy, B.; Subramanian, U.; Thiruvengadam, M. Exosomes: Current Use and Future Applications. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 500, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitha, A.E.; Kollefrath, A.W.; Huang, C.-Y.C.; Garcia-Godoy, F. Characterization and Therapeutic Uses of Exosomes: A New Potential Tool in Orthopedics. Stem Cells Dev. 2019, 28, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popowski, K.; Lutz, H.; Hu, S.; George, A.; Dinh, P.; Cheng, K. Exosome Therapeutics for Lung Regenerative Medicine. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1785161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghani, A.; Andriesei, P.; Kafetzis, K.N.; Tagalakis, A.D.; Yu-Wai-Man, C. Advances in Exosome Therapies in Ophthalmology–From Bench to Clinical Trial. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022, 100, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kost, Y.; Muskat, A.; Mhaimeed, N.; Nazarian, R.S.; Kobets, K. Exosome Therapy in Hair Regeneration: A Literature Review of the Evidence, Challenges, and Future Opportunities. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 3226–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salarpour, S.; Barani, M.; Pardakhty, A.; Khatami, M.; Pal Singh Chauhan, N. The Application of Exosomes and Exosome-Nanoparticle in Treating Brain Disorders. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 350, 118549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, C. Exosome Cancer Diagnostic Reaches Market. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, A.B.; Ahmed, S.; Johnson, M.; Saeedullah, U.; De Leon, J. Exosomes in Cardiovascular Disease: From Mechanism to Therapeutic Target. Metabolites 2023, 13, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Shang, X.; Guo, M.; Su, L.; Wang, J. Exosomes in the Diagnosis of Neuropsychiatric Diseases: A Review. Biology 2024, 13, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, L.; Lin, W.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, L.; Xiao, J.; Wang, H.; Pang, S.; Wang, H.; Sun, D.; Gong, Y.; et al. Exosomes in Autoimmune Diseases: A Review of Mechanisms and Diagnostic Applications. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2025, 68, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, B.J.; Sims, B.; Matthews, Q.L. Biological Function of Exosomes as Diagnostic Markers and Therapeutic Delivery Vehicles in Carcinogenesis and Infectious Diseases. In Nanomedicines; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Wu, L.-F.; Deng, F.-Y. Exosome: An Emerging Source of Biomarkers for Human Diseases. Curr. Mol. Med. 2019, 19, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cully, M. Exosome-Based Candidates Move into the Clinic. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Gu, Y.; Du, Y.; Liu, J. Exosomes: Diagnostic Biomarkers and Therapeutic Delivery Vehicles for Cancer. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 3333–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.; Almeida, F. Exosome-Based Vaccines: History, Current State, and Clinical Trials. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 711565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Shao, J.; Sun, J.; Hu, L.; Yun, X.; Liuqing, C.; Gong, L.; Wu, S. Exploring Regulatory Frameworks for Exosome Therapy: Insights and Perspectives. Health Care Sci. 2025, 4, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilsiz, N. A Comprehensive Review on Recent Advances in Exosome Isolation and Characterization: Toward Clinical Applications. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 50, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Kaslan, M.; Lee, S.H.; Yao, J.; Gao, Z. Progress in Exosome Isolation Techniques. Theranostics 2017, 7, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeringer, E.; Barta, T.; Li, M.; Vlassov, A.V. Strategies for Isolation of Exosomes. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2015, 2015, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanzadeh-Barforoushi, A.; Sango, X.; Johnston, E.L.; Haylock, D.; Wang, Y. Microfluidic Devices for Manufacture of Therapeutic Extracellular Vesicles: Advances and Opportunities. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2025, 14, e70132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, N.; Cai, K.; Bloomquist, T.R.; Strait, M.D.; Ferrante, A.W., Jr.; Baccarelli, A.A. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis for the Quantification and Size Determination of Extracellular Vesicles. J. Vis. Exp. 2021, e62447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.; Tang, V.A.; Lannigan, J.; Jones, J.C.; Welsh, J.A. Quantitative Flow Cytometry Enables End-to-End Optimization of Cross-Platform Extracellular Vesicle Studies. Cell Rep. Methods 2023, 3, 100664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koritzinsky, E.H.; Street, J.M.; Star, R.A.; Yuen, P.S.T. Quantification of Exosomes. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017, 232, 1587–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Anand, S.; Deshmukh, S.K.; Singh, S.; Singh, A.P. Determining the Size Distribution and Integrity of Extracellular Vesicles by Dynamic Light Scattering. In Cancer Biomarkers: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Luo, X.; Huang, Y.; Xie, T.; Pilarsky, C.; Dang, Y.; Zhang, J. Microfluidic Technology for the Isolation and Analysis of Exosomes. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafadar, A.; Nayerain Jazi, N.; Eghtesadi, M.; Ehtiati, S.; Movahedpour, A.; Savardashtaki, A. Exosome Biosensors for Detection of Ovarian Cancer. Mol. Cell. Probes 2025, 84, 102051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Ratri, A.; Deighan, C.; Daaboul, G.; Geiger, P.C.; Christenson, L.K. Single-Particle Interferometric Reflectance Imaging Characterization of Individual Extracellular Vesicles and Population Dynamics. J. Vis. Exp. 2022, 179, e62988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurian, T.K.; Banik, S.; Gopal, D.; Chakrabarti, S.; Mazumder, N. Elucidating Methods for Isolation and Quantification of Exosomes: A Review. Mol. Biotechnol. 2021, 63, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Hvam, M.L.; Primdahl-Bengtson, B.; Boysen, A.T.; Whitehead, B.; Dyrskjøt, L.; Ørntoft, T.F.; Howard, K.A.; Ostenfeld, M.S. Comparative Analysis of Discrete Exosome Fractions Obtained by Differential Centrifugation. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 25011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ma, Z.; Kang, X. Current Status and Outlook of Advances in Exosome Isolation. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 7123–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarovni, N.; Corrado, A.; Guazzi, P.; Zocco, D.; Lari, E.; Radano, G.; Muhhina, J.; Fondelli, C.; Gavrilova, J.; Chiesi, A. Integrated Isolation and Quantitative Analysis of Exosome Shuttled Proteins and Nucleic Acids Using Immunocapture Approaches. Methods 2015, 87, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imanbekova, M.; Suarasan, S.; Lu, Y.; Jurchuk, S.; Wachsmann-Hogiu, S. Recent Advances in Optical Label-Free Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles. Nanophotonics 2022, 11, 2827–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libregts, S.F.W.M.; Arkesteijn, G.J.A.; Németh, A.; Nolte-’t Hoen, E.N.M.; Wauben, M.H.M. Flow Cytometric Analysis of Extracellular Vesicle Subsets in Plasma: Impact of Swarm by Particles of Non-interest. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 16, 1423–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W.; Lane, R.; Korbie, D.; Trau, M. Observations of Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing for Exosome Analysis: Improving System Sensitivity and Stability. Langmuir 2015, 31, 6577–6587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daaboul, G.G.; Gagni, P.; Benussi, L.; Bettotti, P.; Ciani, M.; Cretich, M.; Freedman, D.S.; Ghidoni, R.; Ozkumur, A.Y.; Piotto, C.; et al. Digital Detection of Exosomes by Interferometric Imaging. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Cheng, W.; Wu, T.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Bai, H.; Ding, S.; Li, X.; et al. Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for Exosome Detection Based on Reformative Tyramine Signal Amplification Activated by Molecular Aptamer Beacon. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, A.; Hu, J.; Feng, L.; Liu, L.; Shen, Z. Recent Developments in Isolating Methods for Exosomes. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 10, 1100892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Sharma, A.; Moulick, M.; Gavande, P.V.; Nandy, A.; Xuan, Y.; Sen, C.K.; Ghatak, S. Labeling, Isolation and Characterization of Cell-Type-Specific Exosomes Derived from Mouse Skin Tissue. Nat. Protoc. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, T.E.; Nagelkerke, A.; Nele, V.; Kauscher, U.; Stevens, M.M. Experimental Artefacts Can Lead to Misattribution of Bioactivity from Soluble Mesenchymal Stem Cell Paracrine Factors to Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1807674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, D.; Bathini, S.; Badilescu, S.; Ghosh, A.; Packirisamy, M. Microfluidic Platforms for the Isolation and Detection of Exosomes: A Brief Review. Micromachines 2022, 13, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, H. Regulating the Production and Biological Function of Small Extracellular Vesicles: Current Strategies, Applications and Prospects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erwin, N.; Serafim, M.F.; He, M. Enhancing the Cellular Production of Extracellular Vesicles for Developing Therapeutic Applications. Pharm. Res. 2023, 40, 833–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Upadya, M.; Wong, A.S.W.; Dalan, R.; Dao, M. Isolating Small Extracellular Vesicles from Small Volumes of Blood Plasma Using Size Exclusion Chromatography and Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation: A Comparative Study. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, K.B.; Gudbergsson, J.M.; Andresen, T.L.; Simonsen, J.B. What Is the Blood Concentration of Extracellular Vesicles? Implications for the Use of Extracellular Vesicles as Blood-Borne Biomarkers of Cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Rev. Cancer 2019, 1871, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragovic, R.A.; Gardiner, C.; Brooks, A.S.; Tannetta, D.S.; Ferguson, D.J.P.; Hole, P.; Carr, B.; Redman, C.W.G.; Harris, A.L.; Dobson, P.J.; et al. Sizing and Phenotyping of Cellular Vesicles Using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis. Nanomedicine 2011, 7, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mørk, M.; Pedersen, S.; Botha, J.; Lund, S.M.; Kristensen, S.R. Preanalytical, Analytical, and Biological Variation of Blood Plasma Submicron Particle Levels Measured with Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis and Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 2016, 76, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares Martins, T.; Catita, J.; Martins Rosa, I.; da Cruz e Silva, O.A.B.; Henriques, A.G. Exosome Isolation from Distinct Biofluids Using Precipitation and Column-Based Approaches. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, K.D.; Wadey, R.M.; Mathew, D.; Johnson, E.; Rees, D.A.; James, P.E. Evidence for Adipocyte-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in the Human Circulation. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 3259–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Takeuchi, T.; Takeda, A.; Mochizuki, H.; Nagai, Y. Comparison of Serum and Plasma as a Source of Blood Extracellular Vesicles: Increased Levels of Platelet-Derived Particles in Serum Extracellular Vesicle Fractions Alter Content Profiles from Plasma Extracellular Vesicle Fractions. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamaly, S.; Ramberg, C.; Olsen, R.; Latysheva, N.; Webster, P.; Sovershaev, T.; Brækkan, S.K.; Hansen, J.-B. Impact of Preanalytical Conditions on Plasma Concentration and Size Distribution of Extracellular Vesicles Using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Bruce, T.F.; Huang, S.; Marcus, R.K. Isolation and Quantitation of Exosomes Isolated from Human Plasma via Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography Using a Polyester, Capillary-Channeled Polymer Fiber Phase. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1082, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božič, D.; Sitar, S.; Junkar, I.; Štukelj, R.; Pajnič, M.; Žagar, E.; Kralj-Iglič, V.; Kogej, K. Viscosity of Plasma as a Key Factor in Assessment of Extracellular Vesicles by Light Scattering. Cells 2019, 8, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S.; Hutchinson, K.A.; da Silva, D.F.; Bhattacharjee, J.; McInnis, K.; Burger, D.; Adamo, K.B. Circulating Small Extracellular Vesicles Increase after an Acute Bout of Moderate-Intensity Exercise in Pregnant Compared to Non-Pregnant Women. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelibter, S.; Marostica, G.; Mandelli, A.; Siciliani, S.; Podini, P.; Finardi, A.; Furlan, R. The Impact of Storage on Extracellular Vesicles: A Systematic Study. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, e12162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woud, W.W.; Hesselink, D.A.; Hoogduijn, M.J.; Baan, C.C.; Boer, K. Direct Detection of Circulating Donor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, B.; Henrich, D.; Schindler, C.R.; Marzi, I.; Leppik, L. Release of Exosomes in Polytraumatized Patients: The Injury Pattern Is Reflected by the Surface Epitopes. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1107150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichá, K.; Pastorek, M.; Repiská, G.; Celec, P.; Konečná, B. Investigation of the Presence of DNA in Human Blood Plasma Small Extracellular Vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, K.H.W.; Krzyzaniak, O.; Al Hrout, A.; Peacock, B.; Chahwan, R. Assessing Extracellular Vesicles in Human Biofluids Using Flow-Based Analyzers. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 2301706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marić, I.; Žiberna, K.; Kolenc, A.; Maličev, E. Platelet Activation and Blood Extracellular Vesicles: The Influence of Venepuncture and Short Blood Storage. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2024, 106, 102842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, L.M. Application of EXODUS System Combined with Allosteric DNA Nanoswitches in the Detection of MiR-107 among Plasma Exosomes of Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2024, 58, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małys, M.S.; Aigner, C.; Schulz, S.M.; Schachner, H.; Rees, A.J.; Kain, R. Isolation of Small Extracellular Vesicles from Human Sera. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helwa, I.; Cai, J.; Drewry, M.D.; Zimmerman, A.; Dinkins, M.B.; Khaled, M.L.; Seremwe, M.; Dismuke, W.M.; Bieberich, E.; Stamer, W.D.; et al. A Comparative Study of Serum Exosome Isolation Using Differential Ultracentrifugation and Three Commercial Reagents. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rui, S.; Yuan, Y.; Du, C.; Song, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Fan, Y.; Armstrong, D.G.; Deng, W.; Li, L. Comparison and Investigation of Exosomes Derived from Platelet-Rich Plasma Activated by Different Agonists. Cell Transplant. 2021, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordero, L.; Domingo, J.C.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno Mengual, E.; Pinto, H. Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma Exosome Quantification after Two Thermo-Photobiomodulation Protocols with Different Fluences. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2025, 29, 100267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.A.; Chan, L.K.W.; Hung, L.C.; Phoebe, L.K.W.; Park, Y.; Yi, K.-H. Clinical Applications of Exosomes: A Critical Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.V.T.; Witwer, K.W.; Verhaar, M.C.; Strunk, D.; van Balkom, B.W.M. Functional Assays to Assess the Therapeutic Potential of Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 10, e12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, W.; Xu, W.; Qian, H.; Ji, C. Advances of Extracellular Vesicles Isolation and Detection Frontier Technology: From Heterogeneity Analysis to Clinical Application. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, G.R.; Kourembanas, S.; Mitsialis, S.A. Toward Exosome-Based Therapeutics: Isolation, Heterogeneity, and Fit-for-Purpose Potency. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 4, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergauwen, G.; Tulkens, J.; Pinheiro, C.; Avila Cobos, F.; Dedeyne, S.; De Scheerder, M.; Vandekerckhove, L.; Impens, F.; Miinalainen, I.; Braems, G.; et al. Robust Sequential Biophysical Fractionation of Blood Plasma to Study Variations in the Biomolecular Landscape of Systemically Circulating Extracellular Vesicles across Clinical Conditions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, S.L.; Allen, C.L.; Benjamin-Davalos, S.; Koroleva, M.; MacFarland, D.; Minderman, H.; Ernstoff, M.S. A Rapid Exosome Isolation Using Ultrafiltration and Size Exclusion Chromatography (REIUS) Method for Exosome Isolation from Melanoma Cell Lines. In Melanoma: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Wu, C.; Lin, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, W.; Wang, T.; Cui, Y. Establishment of a Simplified Dichotomic Size-exclusion Chromatography for Isolating Extracellular Vesicles toward Clinical Applications. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, J.; Ji, X.; Tan, Z.; Lubman, D.M. Column-Based Technology for CD9-HPLC Immunoaffinity Isolation of Serum Extracellular Vesicles. J. Proteome Res. 2021, 20, 4901–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Liu, X.; Wu, M.; Shi, S.; Fu, Q.; Jia, J.; Chen, G. Untouched Isolation Enables Targeted Functional Analysis of Tumour-cell-derived Extracellular Vesicles from Tumour Tissues. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, e12214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Li, D.; Wang, M.; Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, Q.; Sun, W.; Li, J.; Gong, Y.; Liu, D.; et al. Exposure to Blue Light Stimulates the Proangiogenic Capability of Exosomes Derived from Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, J.; Ma, K.; Li, H.; Fu, X.; Zhang, C. Photobiomodulation Promotes Hair Regeneration in Injured Skin by Enhancing Migration and Exosome Secretion of Dermal Papilla Cells. Wound Repair Regen. 2022, 30, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri, H.S.; Mousavi, M.; Rezabakhsh, A.; Rezaie, J.; Rasta, S.H.; Nourazarian, A.; Avci, Ç.B.; Tajalli, H.; Talebi, M.; Oryan, A.; et al. Low-Level Laser Irradiation at a High Power Intensity Increased Human Endothelial Cell Exosome Secretion via Wnt Signaling. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 1131–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-Y.; Aviña, A.E.; Chang, C.-J.; Lu, L.-S.; Chong, Y.-Y.; Ho, T.Y.; Yang, T.-S. Exploring the Biphasic Dose-Response Effects of Photobiomodulation on the Viability, Migration, and Extracellular Vesicle Secretion of Human Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2024, 256, 112940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).