Abstract

In this work, a potentiometric sensor for the detection of biogenic amines (BAs) in food samples was developed and characterised. The sensor employs a home-fabricated electrode incorporating a cucurbit[6]uril-modified polyvinyl chloride membrane as the sensing element. The working principle, system behaviour, and optimal operational conditions for BA monitoring were systematically investigated. The developed sensor demonstrated excellent analytical performance, showing a linear response in the concentration range of 3.0 × 10−5 to 1.0 × 10−2 mol L−1, with a low limit of detection of 2.4 × 10−5 mol L−1. Among the tested analytes, the sensor exhibited the highest sensitivity toward tyramine. These results highlight the potential of the proposed cucurbit[6]uril-based potentiometric sensor as an effective and reliable tool for monitoring BAs in complex food matrices, contributing to improved food safety, quality control, and spoilage prevention in the food industry, while also demonstrating its new application as a low-cost, easily constructed platform for rapid tyramine screening in food products.

1. Introduction

Until now, the impact of high levels of consumption of biogenic amines (BA) on human health has yet to garner relevance and focus. Apart from histamine, considered the most toxic among all the BAs, none of the others are regulated. However, the ingestion of high-BA-content foods (>900 mg kg−1) is correlated with some symptoms, including cardiovascular, neurological, and gastric disorders [1]. A tyramine (TYR) concentration of 125 mg kg−1 is considered potentially toxic in humans [2]. Paulsen et al. reported the maximum TYR levels tolerable in different food products [3,4], with cheese and fermented sausage being the ones with the highest values, which present TYR concentrations of 1000 mg kg−1 and 2000 mg kg−1, respectively. These values are relatively high since some reports indicate that the consumption of TYR levels higher than 1080 mg kg−1 to be toxic [4].

As the BAs are obtained by decarboxylation reactions promoted by microorganisms, the content of BAs in foods can also serve as a food spoilage indicator. Several authors have proposed different formulations to establish an index for use as a tool for product rejection [5,6,7]. For these reasons, the assessment of BA levels is an important factor in the food sector.

Currently, the determination of BA content is accomplished mostly using chromatographic or capillary electrophoresis methods, which are complex and expensive techniques [8,9]. Other methods, such as optical and electrochemical sensors, have been considered for this purpose [5,10,11]. However, the absence of optical or electrochemical activity in certain BAs poses a significant challenge for their direct quantification. In this scenario, potentiometry emerges as a reliable alternative to determine non-electroactive BAs. Compared to other electrochemical techniques, potentiometry is based on measuring the potential difference within an electrochemical cell and can be used for the determination of non-electroactive BAs. This technique offers several advantages, such as fast analysis, minimal training required to operate the instrumentation, and low equipment cost [12]. Potentiometric membranes can be prepared using compounds which specifically interact with amines [13]. Upon binding of an amine to the membrane, the measured potential changes, with the magnitude of this response being proportional to the logarithm of the analyte concentration.

Cucurbit[n]urils are a family of supramolecular host molecules consisting of glycoluril units bridged by methylene groups that can represent a valid option for chemosensor development [14]. Due to their rigid structure, selectivity, and the capacity of host–guest molecules and ions, different cucurbits can be considered depending on the target molecule to develop tailored sensors. Cucurbit[7]uril was already studied as a drug delivery system for atropine to increase drug bioavailability, increase targeting, and diminish the systemic toxicity of the drug [15]. In this respect, Ferreira et al. developed a cucurbit[6]uril-based supramolecular potentiometric sensor for the detection of atropine [16]. The sensor demonstrated high selectivity and sensitivity for atropine, presenting potentiometric selectivity coefficients of 0.01 to 0.6, with benzalkonium chloride being the most interferent species, which can be attributed to the strong host–guest interactions between cucurbituril and atropine. A limit of detection (LOD) of 6.3 × 10−7 M was reached, in a linear range from 1.0 × 10−6 to 1.0 × 10−2 M. The obtained slope was 56.2 mV/decade, which is close to a Nernstian response of 59.1 mV/decade for a one-electron transfer reaction.

Using poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC)-based ion-selective membranes (ISMs) and incorporating cucurbiturils for amine detection seems to be a promising strategy for chemical sensing, especially for environmental, biomedical, or food applications. Cucurbit[n]urils can host–guest amines (primary, secondary, tertiary) to form complexes with the macrocycle via hydrogen bonding and ion–dipole interactions. In the cucurbit[n]uril-containing ISM, this interaction affects the membrane potential, measurable by potentiometric methods. The selectivity depends on several factors such as amine size, charge state, and cucurbit cavity size. For a good measurement, amine molecules should be protonated for better interaction with the macrocycle molecules.

In this regard, Amorim et al. [17] have applied cucurbit[n]urils-incorporated sensing membranes to the determination of etilefrine. By incorporating cucurbit[6]uril as an ionophore in a polymeric membrane, and potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate as an additive, the authors obtained a Nernstian slope of 58.7 mV/decade over a 6.30 × 10−7 to 1.52 × 10−6 mol L−1 concentration range and a limit of detection of 6.30 × 10−7 mol L−1 for etilefrine at their potentiometric sensor.

Recently, Pereira et al. reported a histamine-selective electrode based on cucurbit[6]uril proposed for the analysis of biological samples [18]. Using a potentiometric sensor incorporating cucurbit[6]uril as an ionophore in a PVC membrane, high stability constants with histamine were achieved (log β = 4.33), ensuring selective binding with the sensor. It exhibited a rapid response (~13 s), showing a Nernstian slope of 30.9 mV/decade (standard deviation 1.2 mV/decade), a two-electron transfer reaction, over a 3 × 10−7–1 × 10−2 mol L−1 linear range, and a detection limit of ~3 × 10−7 mol L−1 for histamine.

A novel method for detecting tetracycline derivatives in milk was also developed using a polymeric membrane containing cucurbit[8]uril as a host molecule [19]. The potentiometric sensor was coupled to high-performance liquid chromatography to enhance the sensitivity and accuracy of the detection method. The obtained limits of detection ranged from 1.3 × 10−7 to 4.3 × 10−7 M for the different studied antibiotics. The linear ranges were established from 3.0 × 10−7 to 1.0 × 10−3 M. The use of cucurbit[8]uril instead of cucurbit[6]uril seemed to be more appropriate, since the target molecule was bigger and a large cavity was necessary to host–guest this molecule.

In this work, PVC-based potentiometric membranes were developed, using cucurbit[6]uril as a sensing element for the determination of different BAs. These membranes were produced in a disposable home-made electrode based on pipette tips. These electrodes operate on the same principles as conventional electrodes but offer a low-cost and disposable alternative which requires a small sample volume, making them well-suited for rapid on-site analyses. The potentiometric response for six different BAs was assessed, and the analytical parameters were established. As a proof-of-concept regarding the practical application, the developed sensor was applied to determine TYR content in commercial soy sauce samples, introducing a new, low-cost, and easily constructed platform for rapid tyramine screening.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

For the ISM preparation, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and carboxylated PVC (PVC-COOH) were used as a membrane matrix. Dioctyl sebacate (DOS) and 2-nitrophenyl octyl ether (2-NPOE) were applied as solvent mediators, and potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate was used as an additive. Cucurbit[6]uril was used as the ionophore for amine sensing. All the above-mentioned chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Gallen, Switzerland) and used as received.

The 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid hydrate (MES) was also obtained from Sigma Aldrich and used to prepare the buffer solutions. All the sensor formulations were prepared in anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF) from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

Cadaverine (CAD, 97%+ Sigma), putrescine (PUT, 98% Aldrich), tyramine (TYR, Aldrich), histamine dihydrochloride (HIS, 99% Acros Organic, Janssen Pharmaceuticalaan 3A, Geel, Belgium), spermidine trihydrochloride (SMD, 99+% Acros Organic), and spermine tetrahydrochloride (SPM, 99% Alfa Aesar, Haverhill, MA, USA) were the amines used in this study.

The organic acids tartaric acid (AcTar) and citric acid (AcCit) were acquired from Sigma Aldrich and used in the selectivity tests.

2.2. Sensor and ISM Preparation

The poly(vinyl chloride)-based ISMs were obtained by mixing the solvent mediator DOS or 2-NPOE with PVC in THF. Cucurbit[6]uril and potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate were added in concentrations of 1.5% (w/w) and 0.2% (w/w), respectively, considering the final membrane composition. The composition of the prepared ISMs is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Membrane composition (% w/w).

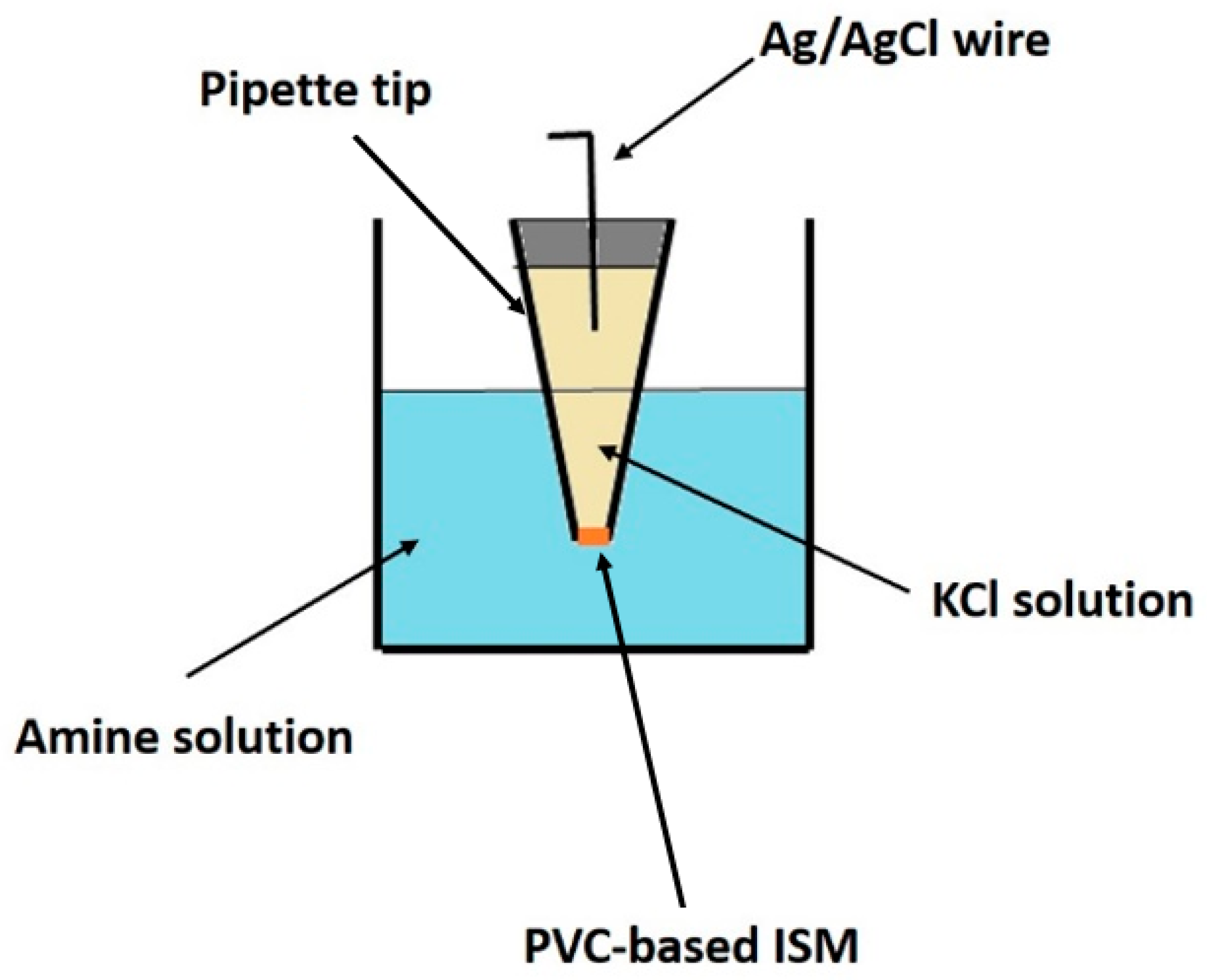

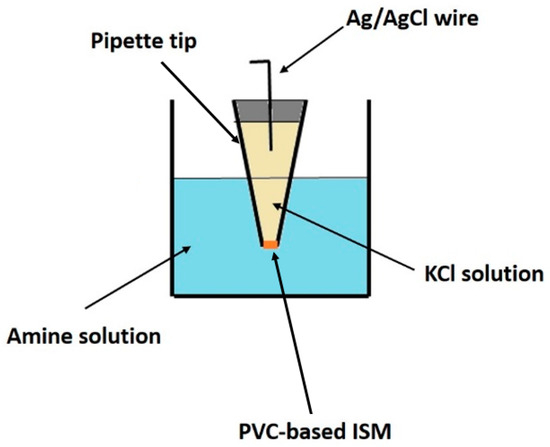

By placing commercially available micropipette tips (1000 μL) in each formulation (Table 1), capillary action drove the liquid into the tips. They were then left to dry at room temperature overnight. After that, the pipette tips were washed with distilled water. Then, a 0.1 mol L−1 KCl solution was introduced into the tip, along with a AgCl-coated Ag wire and sealed. During this step, the presence of air bubbles inside the tip should be avoided. To prepare the AgCl-coated Ag wires, the Ag wires were immersed in a sodium hypochlorite solution for 30 min. Before use, the ISMs were conditioned in a 5 × 10−4 mol L−1 solution of the targeted amines to equilibrate the membrane concentration gradient and achieve a more stable potentiometric response. A schematic representation of the produced sensor is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the developed sensor.

2.3. Potentiometric Measurements

The potential difference (i.e., electromotive force, EMF) was measured at room temperature with a precision electrochemistry EMF 16 Interface from Lawsons Labs (Malvern, PA, USA). The external reference electrode was a double-junction-type Ag/AgCl electrode with a standard internal solution from ORION® and a 0.01 mol L−1 MES buffer solution (pH = 5.5) as the external solution. The calibration curves were obtained by successive injections of BA standard solutions into the MES buffer while stirring with a magnetic stir bar. Upon injection, the EMF readings were continuously recorded and, after the potential reached a stable value, the next standard was added. To increase the ionic strength and obtain a stable potentiometric response, NaCl 0.01 mol L−1 was also added to the MES buffer.

2.4. Selectivity

Potentiometric selectivity coefficients for TYR were determined for different interferent compounds (PUT, CAD, HIS, AcTar, and AcCit) according to the IUPAC recommendations, by a mixed-solution method [20], using the fixed interference method. For this, 0.5 mmol L−1 TYR was used as a background solution. All potentiometric selectivity tests were performed by measuring the EMF between the developed sensor and the Ag/AgCl electrode as a reference. The selectivity coefficients were evaluated using the Nikolsky–Eisenman equation [20].

Using the fixed interference method, the potential difference was measured for solutions of constant activity of the interfering species, aB, and varying activity of the primary species, aA (in this case, TYR). The EMF values obtained were plotted vs. the logarithm of the activity of the primary species, and the intersection of the extrapolated linear portions of this plot indicated the value of aA that was used to calculate KA,Bpot from the following equation (Equation (1)).

where zA and zB are the corresponding charge numbers of the primary and interfering species [21].

KA,Bpot = aA/aBzA/zB

2.5. Real-Life Sample Analysis

To evaluate the sensor performance, the TYR concentrations in two commercial soy sauce brands, Paladim® and Pingo Doce®, were evaluated using the standard addition method, i.e., by sequentially spiking 100 and 600 μL of the 0.01 M TYR standard solution into 10 mL MES buffer (0.01 M) containing a 20 μL aliquot of each soy sample. The potential difference was measured before and after addition of TYR.

2.6. Chromatographic Analysis

The samples of soy sauce were degassed in an ultrasonic bath for 30 min, and then the derivatisation of the soy sauce samples was performed following a procedure previously described [22]. The TYR standard solutions were also derivatised using the same method. Briefly, 5 mL of soy sauce or TYR standard was mixed with 200 µL of NaOH 10 M and 1 mL of 0.5 M carbonate-hydrogen carbonate buffer (pH 10.5). After that, 1 mL of the obtained mixture was mixed with 2 mL of the dansyl chloride solution 0.5% (w/v). The mixture was left in a thermo-block (J.P. SELECTA) at 40 °C for 15 min and then cooled down to room temperature for 30 min, protected from light. Afterwards, 50 µL of ammonium hydroxide (25% (v/v)) was added to remove the surplus of dansyl chloride. Then, the mixture was restored to 5 mL with acetonitrile and centrifuged (5 min, 3000 rpm, 4 °C). The resulting supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 µm poly(tetrafluoroethylene) filter.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with a Fluorescence Detector (HPLC-FLD) was performed with an LC Shimadzu LC-20AD Prominence equipped with a SIL-20 AHT autosampler, a CTO-10 AS VP oven, and an RF-20 AXS fluorescence detector, all from Shimadzu Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). The HPLC method was based on the one previously described [23].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Membrane Composition Optimisation

One of the key components is the ISM, which is designed to selectively interact with the target (principal ion). This interaction generates a potential difference across the membrane, which can be measured in a potentiometric electrochemical cell [24]. The obtained potential difference is directly related to the activity (concentration) of the target ion. The relationship between the measured potential and target concentration can be assessed by the Nernst equation (Equation (2)).

where E is the measured potential (V), K is a constant potential contribution that includes the junction potentials in the cell, R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature (K), F is the Faraday constant, and ai is the activity in the sample for ion i, with charge zi.

Amines are basic compounds and can accept protons to form protonated amine cations (R-NH3+). These cations can then be potentiometrically measured using ion-selective electrodes.

As the concentration of protonated amine increases, the electrode potential shifts positively (cationic response). For monovalent cations like TYR+, according to Nernstian behaviour, the potentiometric response should be linear with the logarithm of the TYR concentration. However, some sensors exhibited deviations from ideal Nernstian behaviour (≈59.1 mV/decade) [25]. This can be due to different factors, such as slow electrode kinetics or surface effects [26,27]. In the case of PVC-based membranes, due to the membrane ageing over time, changes in the ion-selective properties can occur. This results in a non-linear response or a reduced slope in the observed potential. Also, membrane diffusion and ion-exchange kinetics may not be perfectly reversible, leading to a delay in reaching equilibrium and thus a deviation from the expected Nernstian behaviour.

For ISM optimisation, several factors were considered, such as the solvent mediator and the type of PVC. Regarding the solvent exchange mediator, between DOS and 2-NPOE, highly sensitive responses to amine, presenting higher slopes, were achieved using the latter [11,12].

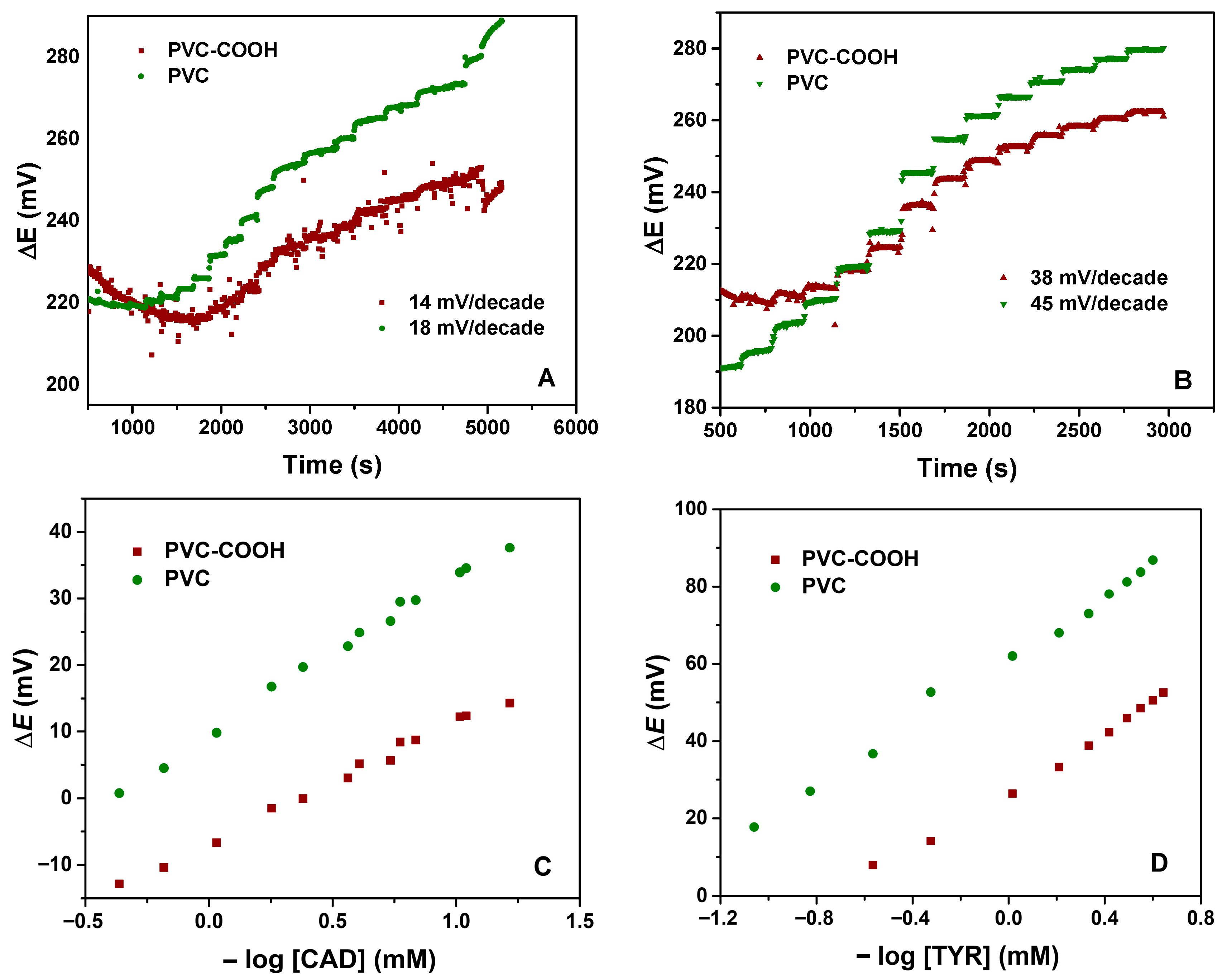

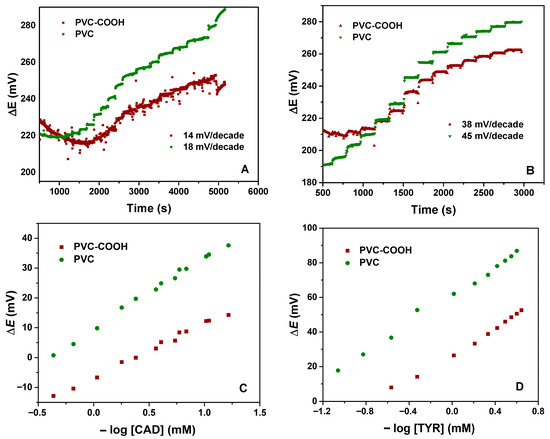

The second aspect to be considered was the use of PVC or functionalized PVC. Figure 2 shows the potentiometric response to CAD and TYR, representing the potential difference as a function of time, by increasing the amine concentration in solution, obtained for electrodes with PVC and carboxylated PVC ISMs. These two amines were selected because, along with histamine, they are the most commonly found in foods.

Figure 2.

Potentiometric response for (A) CAD and (B) TYR using ISM with PVC and PVC-COOH, and corresponding calibration plot for (C) CAD and (D) TYR.

As can be observed, the membranes with COOH groups present a lower slope, of 14 mV/decade for CAD and 38 mV/decade for TYR, compared to the corresponding 18 mV/decade and 45 mV/decade for the PVC membrane, respectively. The slope values were computed from the calibration plots.

Cucurbit[6]uril has a hydrophobic cavity and polar carbonyl-laced portals. It can form host–guest complexes through non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, ion–dipole interactions, and hydrophobic effects. The interaction of carboxylic acid groups from the carboxylated PVC with cucurbit[6]uril depends on their ionisation state. For example, in a protonated condition, a system containing molecules with positive charges (e.g., amines) and a carboxylic group can form bifunctional interactions with cucurbit[6]uril [28]. The carboxylated molecules can interact with the portal region, enhancing binding stability. For this reason, the use of PVC without carboxyl acid groups and of 2-NPOE as a solvent exchange mediator was considered for the next steps.

Overall, the sensors showed a fast response with an average of less than 30 s for the different amine concentrations (Figure 2A,B). These sensor systems have shown the potential to detect biogenic amines, such as CAD and TYR, in aqueous solution in a wide range of concentrations (from 5 × 10−5 to 1 ×10−2 M).

From Figure 2A,B, the slope of the ΔE versus time plot for TYR is more than twice that for CAD, either for PVC or carboxylated PVC, indicating a higher sensitive response for TYR. The fact that CAD is an aliphatic diamine decreases the slope for less than the typical Nernstian value for divalent species (29.6 mV/decade). However, the obtained values are lower than that. Regarding the sensitivity of the sensor for the different amines, the slope values are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Analytical parameters of the developed potentiometric sensor.

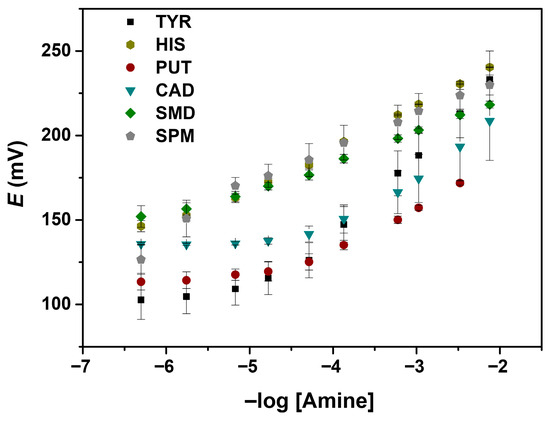

3.2. Analytical Performance of the Sensor

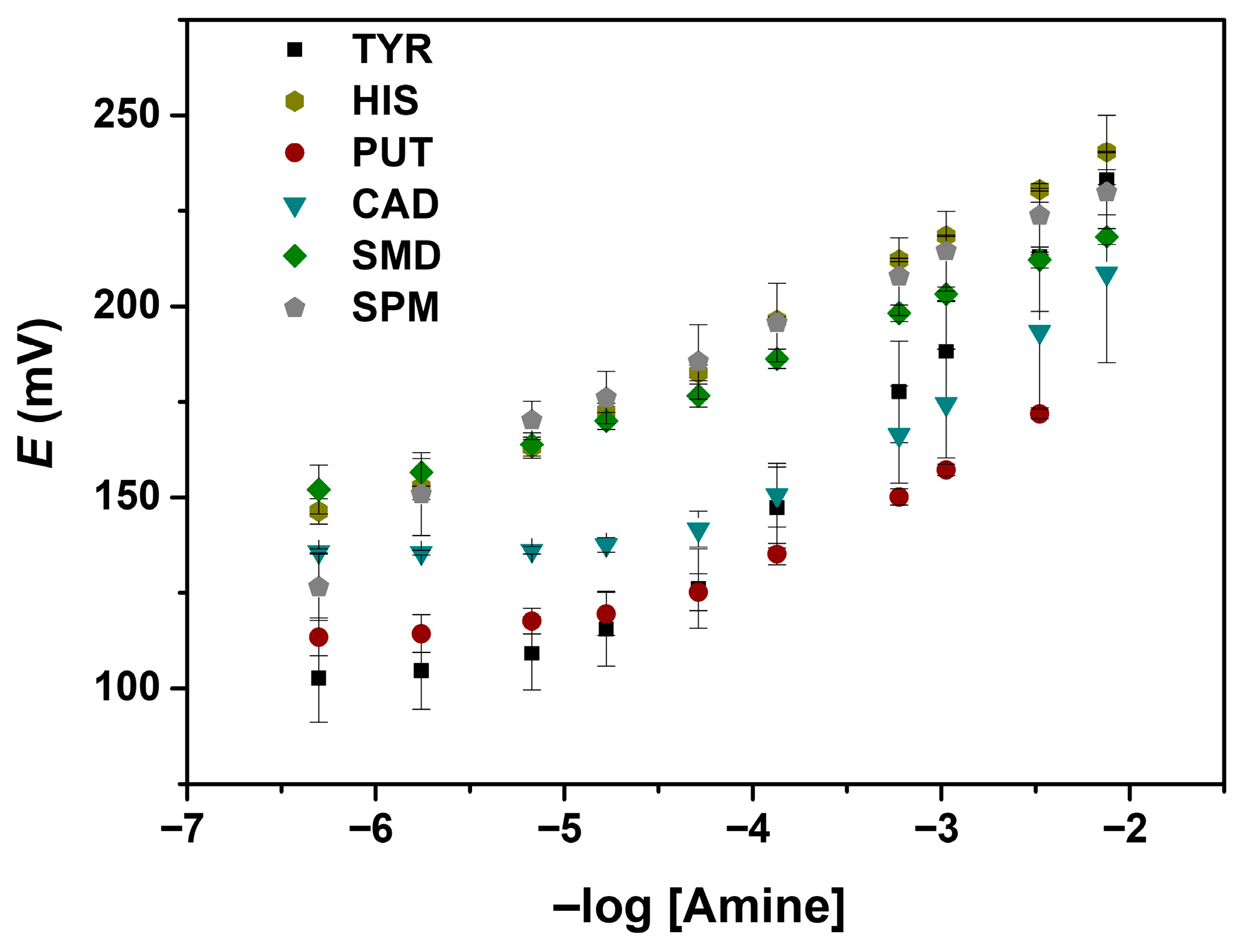

The analytical performance parameters of the developed sensor for several BAs are presented in Figure 3 and Table 2, including sensitivity, limit of detection (LOD), and linear range. These aspects are fundamental for evaluating the sensor’s performance, reliability, and effective usability. The LODs were calculated using the intersection of extrapolated linear portions (IUPAC method) [29].

Figure 3.

Calibration curves for the different BAs in 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) 0.01 M solution, with a pH of 5.5: tyramine (TYR), putrescine (PUT), cadaverine (CAD), spermidine (SMD), spermine (SPM), and histamine (HIS).

Regarding the sensor sensitivity to the studied amine, a higher slope (48.6 mV/decade) was obtained for tyramine (TYR), suggesting that the sensor is more responsive to this analyte, while SMD shows the lowest value (17.8 mV/decade). A higher slope value indicates a more sensitive detection (Table 2). For this reason, TYR was taken as the main analyte to be studied in this work.

The obtained LOD values ranged from 2.8 × 10−6 mol L−1 (HIS) to 5.5 × 10−5 mol L−1 (SMD), indicating that the sensor can detect low concentrations of these amines. The obtained LOD values are useful for the detection of trace amounts, which is critical in food safety applications. The reported LODs are comparable to those reported in the literature for other methods (Table 3), which often range from micromolar to nanomolar levels, depending on the detection method [30,31,32]. High sensitivity and low LODs are crucial for the early detection of food spoilage and for monitoring amines in clinical or environmental samples.

Table 3.

Comparison of LOD and linear range obtained in this work with other methods for TYR detection.

Most of the amines have a linear range of -log [amine] from −4.5 to −2 (Figure 3), corresponding to concentrations from approximately 3.2 × 10−5 to 1 × 10−2 mol L−1, with HIS, SMD, and SPM having slightly wider ranges, starting from 1 × 10−5 mol L−1. Wide linear ranges offer some advantages, as the possibility of quantifying analytes across different sample types and concentrations.

Using an amperometric biosensor, TYR was detected with a LOD as low as 0.62 μmol L−1 [33]. Other works regarding biosensors for histamine in fish extracts report LODs of ca. 4.5 × 10−6 mol L−1 [11]. Linear intervals in these biosensors often range from μmol L−1 up to 1–10 mmol L−1, depending on the analyte and the method used [31,33].

Lange and Wittmann developed an enzyme-based sensor array for the detection and determination of the different BAs [34]. For HIS, PUT, and TYR, LODs of 9 × 10−5, 5.7 × 10−5 and 7.3 × 10−5 mol L−1 were reported, respectively, with linear ranges up to 1.8 × 10−3 mol L−1 [34].

Regarding optical sensing, a colorimetric sensor containing an amine-reactive chromogenic probe and fluorescein was developed by Steiner [31]. For tyramine, an LOD of 2 × 10−5 mol L−1 was achieved in a linear range from 4 × 10−5 to 1 × 10−3 mol L−1. In the case of PUT, the LOD was established as 4 × 10−5 mol L−1 with a linear range from 0.05 to 1.0 mmol L−1.

Taking the example of chromatography methods, the most used technique for the determination of BAs, Ai et al. reported LODs for biogenic amines in the range of 1.5 to 7.5 × 10−8 mol L−1, depending on the amine, with linear ranges up to 5 × 10−6 mol L−1 [35]. This demonstrates the superior sensitivity of chromatographic methods; however, the cost and complexity are far higher, and there is no easy portability for on-site inspections in this case.

The sensor developed in this work achieves LODs in the low micromolar to sub-micromolar range (10−6 to 10−5 mol L−1), which is comparable to or better than several published electrochemical and chromogenic sensors. While HPLC methods can reach lower LODs, they are less suited for easy and on-site analysis. The linear ranges of the provided sensor (approx. 10−5 to 10−2 mol L−1) are suitable for practical applications such as food safety monitoring, matching or exceeding the ranges reported for other sensors. The sensor performance is completely capable of detecting TYR levels below the potential toxic value, which is approximately 9 × 10−4 mol L−1 [36].

In Figure 3, the potential difference as a function of the amine concentration (range from 5 × 10−7 M to 7.5 × 10−2 mol L−1) is observed for all the studied amines. All the experiments were performed in MES buffer. Under these conditions, all the amine groups are protonated, resulting in a positive charge of the amines and, consequently, the observed cationic response.

As depicted in Figure 3, among the amines studied, TYR showed the largest ΔE, followed by CAD. The developed potentiometric sensor membrane also showed good potential for other BAs determination, in particular histamine, for which a lower LOD and a wider linear range were achieved, despite the decreased slope observed (Table 2). The larger ΔE responses observed for TYR and CAD arise from their stronger binding affinities toward cucurbit[6]uril in the membrane. Their molecular size, protonation state, and geometry enable more favourable inclusion within the cucurbit[6]uril cavity, leading to greater changes in interfacial ion distribution and, consequently, larger potential shifts.

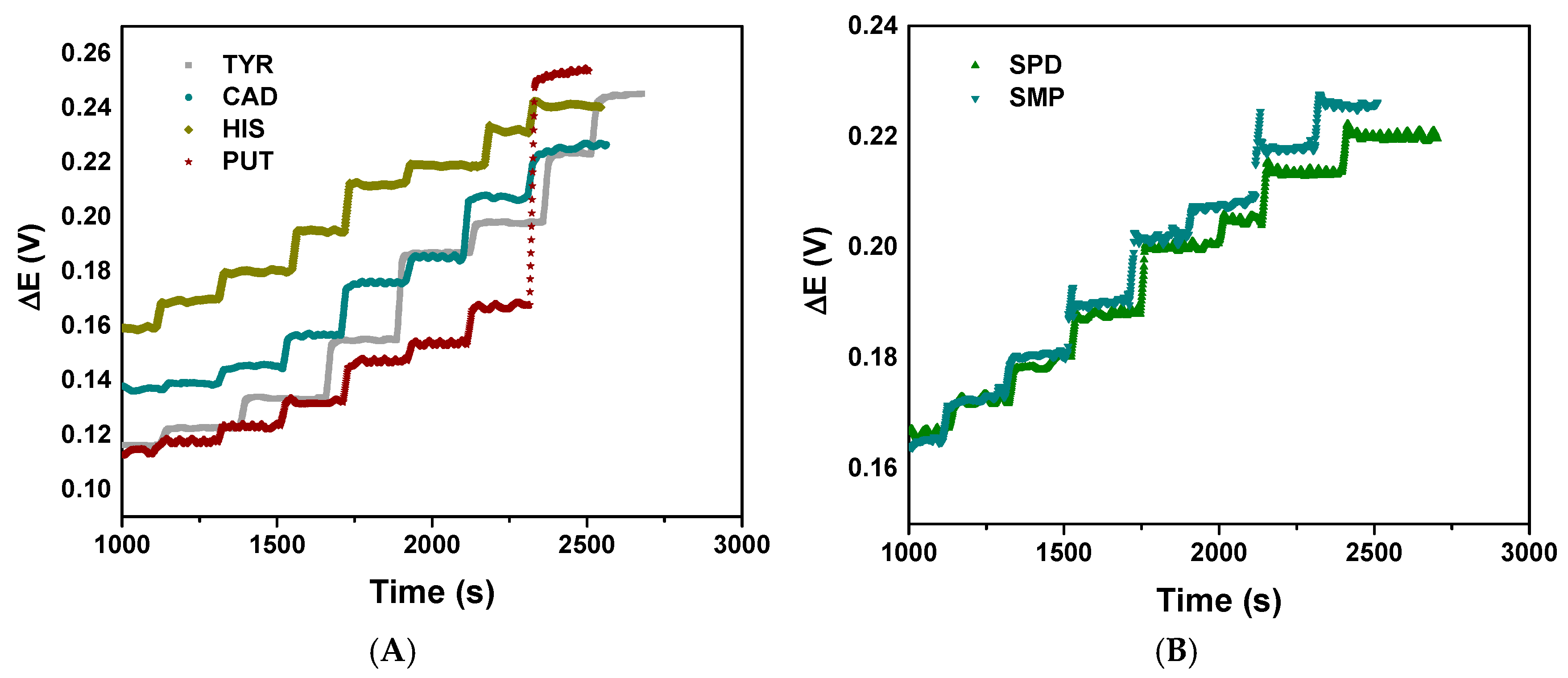

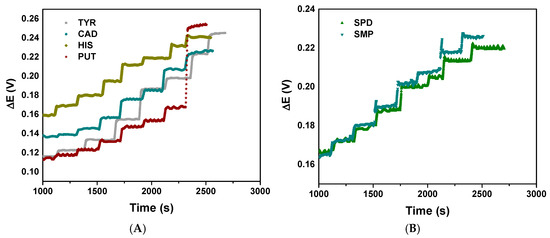

Regarding the sensor response time and stability, the potentiometric sensor demonstrates excellent analytical performance with distinct response patterns for different analytes (Figure 4). Differences in response times usually reflect different chemical kinetics and binding affinities at the sensor interface.

Figure 4.

Potentiometric response time and stability for the studied amines: (A) for TYR, CAD, HIS and PUT and (B) for SPD and SMP.

The most stable complexes tend to be formed with diamines whose molecular size is similar to the receptor. In that case, both amino groups interact with the carbonyl groups [37]. Different BAs interact with cucurbit[6]uril molecules; however, each amine class behaves differently depending on the number of amine groups, chain length, and the ability to thread through the macrocycle cavity. Monoamines, such as HIS and TYR, can lead to low-to-moderate strength since, with only one protonated amine, they can form ion–dipole interactions with one portal. Also, the aromatic or cyclic structures usually prevent complete insertion into the cucurbit[6]uril cavity. On the other hand, diamines (e.g., cadaverine and putrescine) form a strong interaction. When protonated, diamines carry two positive charges, which match perfectly with cucurbit[6]uril portals. The linear chain of these amines can enter through the cavity, giving a highly stabilised inclusion complex. In the same way, polyamines (e.g., spermidine and spermine) also interact very strongly with the macrocycle. Linear polyamines have multiple protonation sites and can adopt different conformations to maximise interaction [38].

The stable and reproducible signals indicate reliable sensor fabrication and consistent surface chemistry, making this sensor suitable for quantitative analysis of these biologically relevant compounds. All the compounds have demonstrated relatively linear potential changes over time, indicating good sensor stability (Figure 4A,B). The response time for all the BAs was less than 15 s, which is a relatively fast response from a practical point of view. The absence of erratic fluctuations or sudden potential changes suggests stable electrode–analyte interactions.

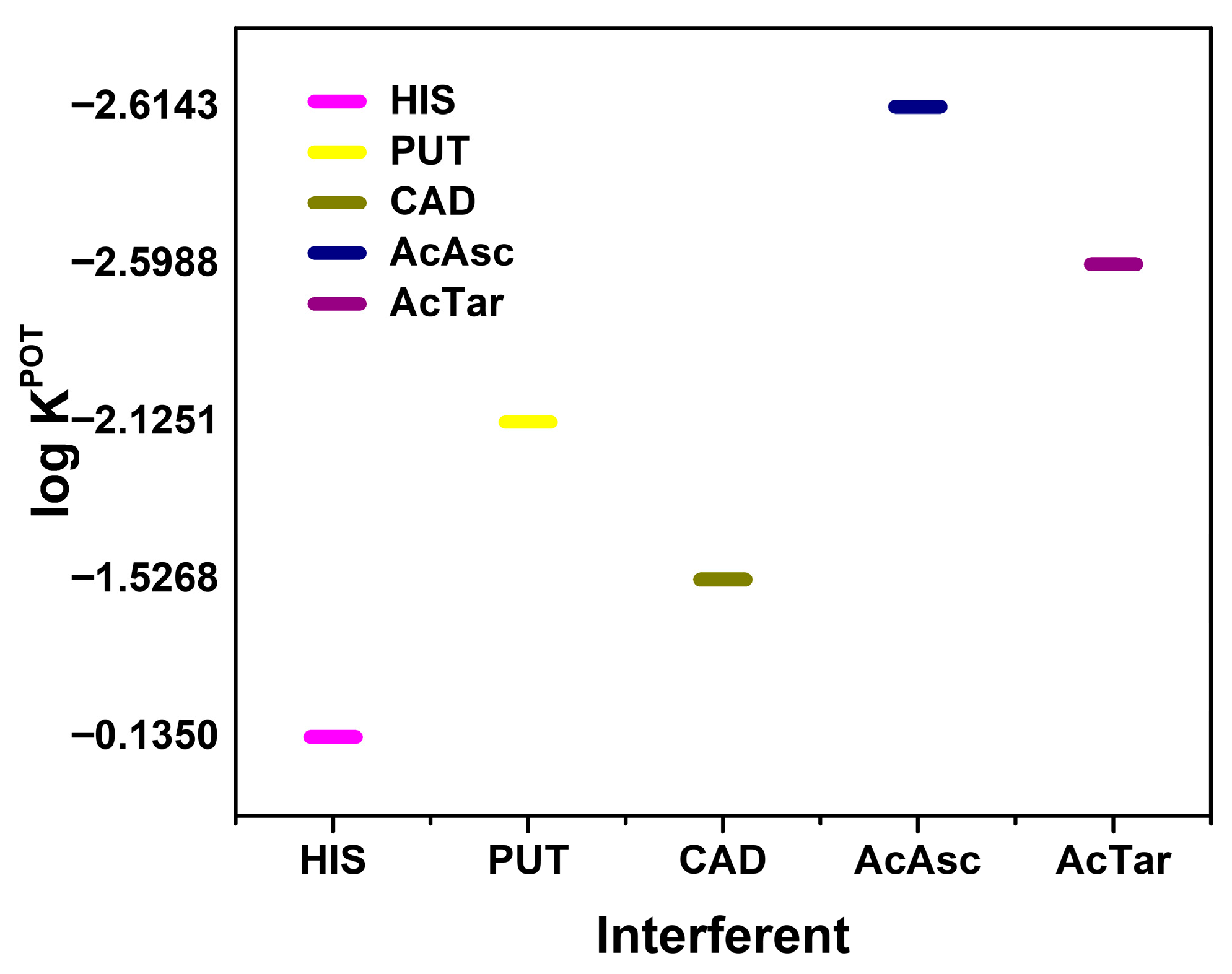

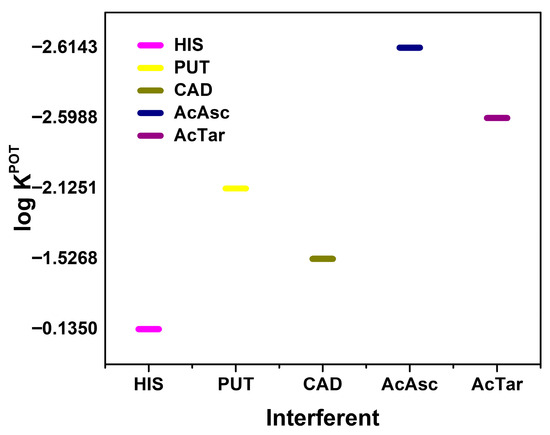

Concerning the sensor selectivity, in a real-life scenario, there are many possible interfering agents present in food samples which can potentially interact with the BA determination. The selectivity of an ISM is one of the most important performance parameters that will determine the usability of the sensor. To ensure the reliability of the developed sensor for TYR detection, selectivity studies were performed using the fixed interference method (Figure 5) [39].

Figure 5.

Selectivity coefficients for different interferences toward TYR.

A mixed solution method was performed with HIS, PUT, CAD, citric acid, and tartaric acid as interfering agents. These species were chosen as they are likely to be present in many food samples along with TYR. A final concentration of 5 × 10−4 mol L−1 for each interference species was used. According to the results in Figure 5, HIS has the most influence on TYR response, presenting a potentiometric selectivity coefficient (logKPOT) of −0.14, followed by the presence of CAD with a logKPOT of −1.53. These results showed that the presence of different BAs in the same sample has a competitive effect regarding the interaction with the cucurbit macrocycle.

3.3. Performance of the Sensor for Real-Life Samples

To demonstrate the applicability of the developed sensor in a real-life scenario, the cucurbit[6]uril-PVC-optimised membrane composition was used to determine the concentration of TYR in two commercial soy sauce brands, using the standard addition method. The obtained values, along with those determined by HPLC, are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

TYR determination of commercial soy sauce samples using HPLC-FLD and the developed Cu[6]uril-PVC sensor.

The obtained values are within the values found in the literature for soy sauce [40]. However, the Cu[6]uril-PVC sensor overestimated TYR levels in soy sauce samples compared to HPLC-FLD, indicating significant matrix interference. This overestimation is consistent with the presence of other BAs, such as HIS, CAD, and PUT, also detected in the samples. In both soy sauces, using HPLC-FLD, concentrations around 40 mg kg−1, 5 mg kg−1, and 450 mg kg−1 were found for HIS, CAD, and PUT, respectively.

These findings, supported by the selectivity data previously discussed, suggest that the sensor is more suitable for rapid screening than for precise quantification.

4. Conclusion

In this work, a potentiometric sensor for BAs with selectivity to TYR was developed. The obtained results demonstrated that the sensor exhibits strong analytical performance for the detection of several BAs, with high sensitivity for TYR. LODs as low as 6.2 × 10−6 to 6.8 × 10−5 and broad linear response ranges (from 2.8 × 10−6 to 1 × 10−2) were achieved for the studied amines (Table 2). For TYR, an LOD of 2.4 × 10−5 mol L−1 was obtained in a linear response range from 3 × 10−5 to 1 × 10−2 mol L−1, which places the developed sensor at a competitive level compared to the other techniques used to determine TYR.

For all the studied amines, a fast response was observed (less than 15 s), indicating that the charge transfer process across the membrane is efficient.

The obtained selectivity coefficients (Figure 5) suggest reasonable discrimination among other BAs and common interferents found in food matrices, enhancing the practical application of the sensor in complex matrices, such as food or biological samples.

Competitive to those reported in the literature, the developed sensor offers a significant advantage in simplicity, speed, and suitability for field or routine laboratory purposes.

Regarding the determination in soy sauces, the developed sensor overestimated TYR levels, suggesting that the sensor is more suitable for rapid screening than for precise quantification; however, it can be used for fast and routine daily quality control operations.

Future research should focus on evaluating the sensor for the determination of TYR in different types of real-food samples (alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages), as well as extending its applicability to other relevant BAs as histamine. Integration with portable readout systems could further improve its suitability for on-site monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.M.R.A. and J.M.C.S.M.; manuscript validation, C.M.R.A., J.M.C.S.M., M.F.B., and L.D.; investigation, C.M.R.A., J.L.A.M., and M.M.M.; data curation, C.M.R.A., J.L.A.M., and M.M.M.; writing—original draft, C.M.R.A.; writing—review and editing, C.M.R.A., J.L.A.M., M.M.M., J.M.C.S.M., M.F.B., and L.D.; supervision, J.M.C.S.M., M.F.B., and L.D.; funding acquisition, C.M.R.A., J.M.C.S.M., M.F.B., and L.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Cláudio M. R. Almeida acknowledges the PhD grant SFRH/BD/150790/2020 by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. (FCT, Portugal), funded by national funds from MCTES (Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior) and, when appropriate, co-funded by the European Commission through the European Social Fund. Manuela M. Moreira is thankful for her contract financed by FCT/MCTES—CEEC Individual Program Contract (DOI: 10.54499/2023.05993.CEECIND/CP2842/CT0009) and to REQUIMTE/LAQV. The work developed at CERES and LAQV-REQUIMTE was supported from the PT national funds (FCT/MECI, Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia and Ministério da Educação, Ciência e Inovação) through the projects https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/00102/2025, https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/PRR/00102/2025 and https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/50006/2025.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Özogul, Y.; Özogul, F. Biogenic Amines Formation, Toxicity, Regulations in Food; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ladero, V.; Calles-Enríquez, M.; Fernández, M.; A Alvarez, M. Toxicological effects of dietary biogenic amines. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2010, 6, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, P.; Bauer, S.; Bauer, F.; Dicakova, Z. Contents of polyamines and biogenic amines in canned pet (dogs and cats) food on the Austrian market. Foods 2021, 10, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulsen, P.; Grossgut, R.; Bauer, F.; Rauscher-Gabernig, E. Estimates of maximum tolerable levels of tyramine content in foods in Austria. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2012, 51, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, C.M.; Magalhães, J.M.; Barroso, M.F.; Durães, L. Biogenic amines detection in food: Emerging trends in electrochemical sensors. Talanta 2025, 292, 127918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mietz, J.L.; Karmas, E. Polyamine and histamine content of rockfish, salmon, lobster, and shrimp as an indicator of decomposition. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 1978, 61, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Herrero, A.M. Impact of biogenic amines on food quality and safety. Foods 2019, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moniente, M.; Botello-Morte, L.; García-Gonzalo, D.; Pagán, R.; Ontañón, I. Analytical strategies for the determination of biogenic amines in dairy products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 3612–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tırıs, G.; Yanıkoğlu, R.S.; Ceylan, B.; Egeli, D.; Tekkeli, E.K.; Önal, A. A review of the currently developed analytical methods for the determination of biogenic amines in food products. Food Chem. 2023, 398, 133919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.M.; Magalhães, J.M.; Barroso, M.F.; Durães, L. Latest advances in sensors for optical detection of relevant amines: Insights into lanthanide-based sensors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 15263–15276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, H.; Coelho, L.C.; Matias, A.; Saraiva, C.; Jorge, P.A.; de Almeida, J.M. Biosensors for Biogenic Amines: A Review. Biosensors 2021, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, K.; Sharma, N.; Gautam, P.B.; Sharma, R.; Mann, B.; Pandey, V. Potentiometry. In Advanced Analytical Techniques in Dairy Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Poels, I.; Nagels, L. Potentiometric detection of amines in ion chromatography using macrocycle-based liquid membrane electrodes. Anal. Chim. Acta 2001, 440, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, K.I.; Nau, W.M. Cucurbiturils: From synthesis to high-affinity binding and catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 394–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdarova Karasova, J.; Mzik, M.; Kucera, T.; Vecera, Z.; Kassa, J.; Sestak, V. Interaction of cucurbit [7] uril with oxime K027, atropine, and paraoxon: Risky or advantageous delivery system? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Palmeira, A.; Sousa, E.; Amorim, C.G.; Araújo, A.N.; Montenegro, M.C. Supramolecular atropine potentiometric sensor. Sensors 2021, 21, 5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes Amorim, C.; Araújo, A.; da Conceição Montenegro, M. Use of cucurbit [6] uril as ionophore in ion selective electrodes for etilefrine determination in pharmaceuticals. Electroanalysis 2019, 31, 2171–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.; Araújo, A.; Montenegro, M.; Amorim, C.G. A simpler potentiometric method for histamine assessment in blood sera. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 3629–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, R.L.; Amorim, C.M.; Montenegro, M.d.C.B.; Araújo, A.N. Cucurbit [8] uril-based potentiometric sensor coupled to HPLC for determination of tetracycline residues in milk samples. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezawa, Y.; Umezawa, K.; Sato, H. Selectivity coefficients for ion-selective electrodes: Recommended methods for reporting KA, Bpot values (Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 1995, 67, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezawa, Y.; Bühlmann, P.; Umezawa, K.; Tohda, K.; Amemiya, S. Potentiometric selectivity coefficients of ion-selective electrodes. Part I. Inorganic Cations (Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2000, 72, 1851–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, M.F.; Flores, M.; Aranda, M.; Henriquez-Aedo, K. Fast and selective method for biogenic amines determination in wines and beers by ultra high-performance liquid chromatography. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 125689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, C.M.; Barroso, M.F.; Moreira, M.M.; Magalhães, J.M.; Durães, L. Direct Electrochemical Detection of Tyramine in Beer Samples Using a MWCNTs Modified GCE. Sensors 2025, 25, 3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, E.; Pretsch, E. Potentiometric sensors for trace-level analysis. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2005, 24, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdrachek, E.; Bakker, E. Potentiometric sensor array with multi-nernstian slope. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 2926–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Labastida, M.F.; Yaroshchuk, A. Transient membrane potential after concentration step: A new method for advanced characterization of ion-exchange membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 585, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandifer, J.R. Implications of ion-exchange kinetics on ion-selective electrode responses and selectivities. Anal. Chem. 1989, 61, 2341–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuéry, P. Supramolecular assemblies built from lanthanide ammoniocarboxylates and cucurbit [6] uril. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 8128–8136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechhold, W.; Liska, E.; Grossmann, H.; Hagele, P. Recommendations for nomenclature of ion-selective electrodes. Pure Appl. Chem. 1976, 48, 10.1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, R.S.; Mercante, L.A.; Facure, M.H.; Sanfelice, R.C.; Fugikawa-Santos, L.; Swager, T.M.; Correa, D.S. Recent progress in amine gas sensors for food quality monitoring: Novel architectures for sensing materials and systems. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 2104–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, M.-S.; Meier, R.J.; Duerkop, A.; Wolfbeis, O.S. Chromogenic sensing of biogenic amines using a chameleon probe and the red− green− blue readout of digital camera images. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 8402–8405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Park, J.H.; Choi, A.; Hwang, H.-J.; Mah, J.-H. Validation of an HPLC analytical method for determination of biogenic amines in agricultural products and monitoring of biogenic amines in Korean fermented agricultural products. Toxicol. Res. 2015, 31, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyap, S.; Tehri, N.; Verma, N.; Gahlaut, A.; Hooda, V. Recent advances in development of electrochemical biosensors for the detection of biogenic amines. 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, J.; Wittmann, C. Enzyme sensor array for the determination of biogenic amines in food samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002, 372, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, Y.; Sun, Y.N.; Liu, L.; Yao, F.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, F.Y.; Zhao, W.J.; Liu, J.L.; Zhang, N. Determination of biogenic amines in different parts of Lycium barbarum L. by HPLC with precolumn dansylation. Molecules 2021, 26, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Mohammed, G.; Al-Eryani, D.; Saigl, Z.; Alyoubi, A.; Alwael, H.; Bashammakh, A.; O’Sullivan, C.; El-Shahawi, M. Biogenic amines formation mechanism and determination strategies: Future challenges and limitations. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2020, 50, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buschmann, H.-J.; Mutihac, L.; Jansen, K.; Schollmeyer, E. Cucurbit [6] uril as ligand for the complexation of diamines, diazacrown ethers and cryptands in aqueous formic acid. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2005, 53, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Kan, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, F.; Xiao, X. Study on the binding interaction of the α, α’, δ, δ’-tetramethylcucurbit [6] uril with biogenic amines in solution and the solid state. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, E.; Pretsch, E.; Bühlmann, P. Selectivity of potentiometric ion sensors. Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, K.I.; Walker, S.E. Refining the MAOI diet: Tyramine content of pizzas and soy products. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1999, 60, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.