Creatinine Sensing with Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based Field Effect Transistors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Measurement Set-Up

2.3. Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Modification of the Graphene Semiconductor Channel

2.4. Improved Structural Stability

2.5. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Spectroscopy

2.6. Measurements in Simulated Urine

3. Results and Discussion

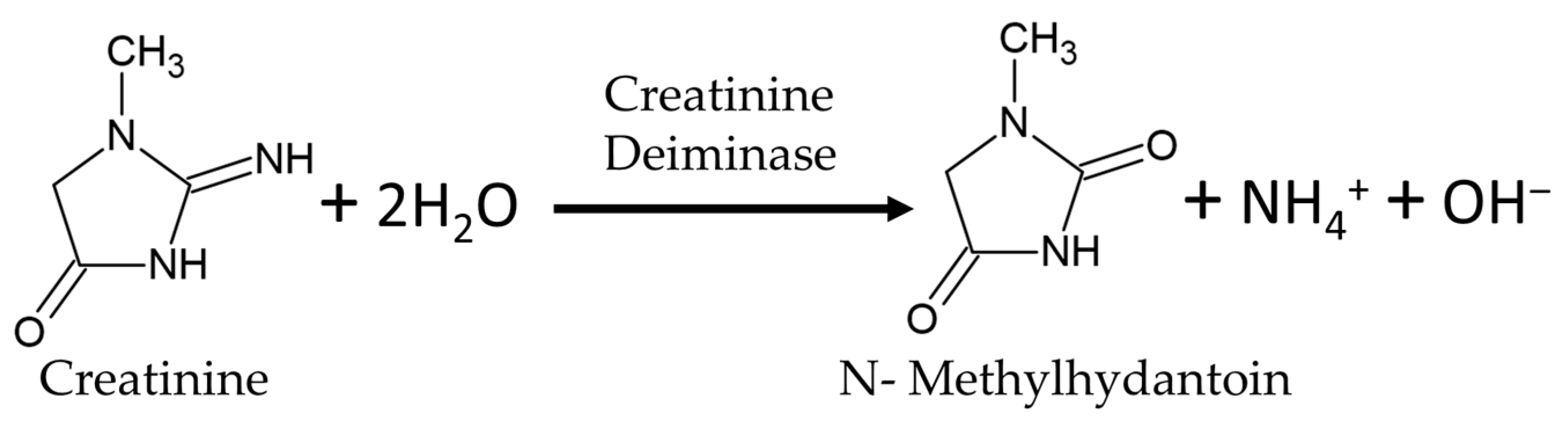

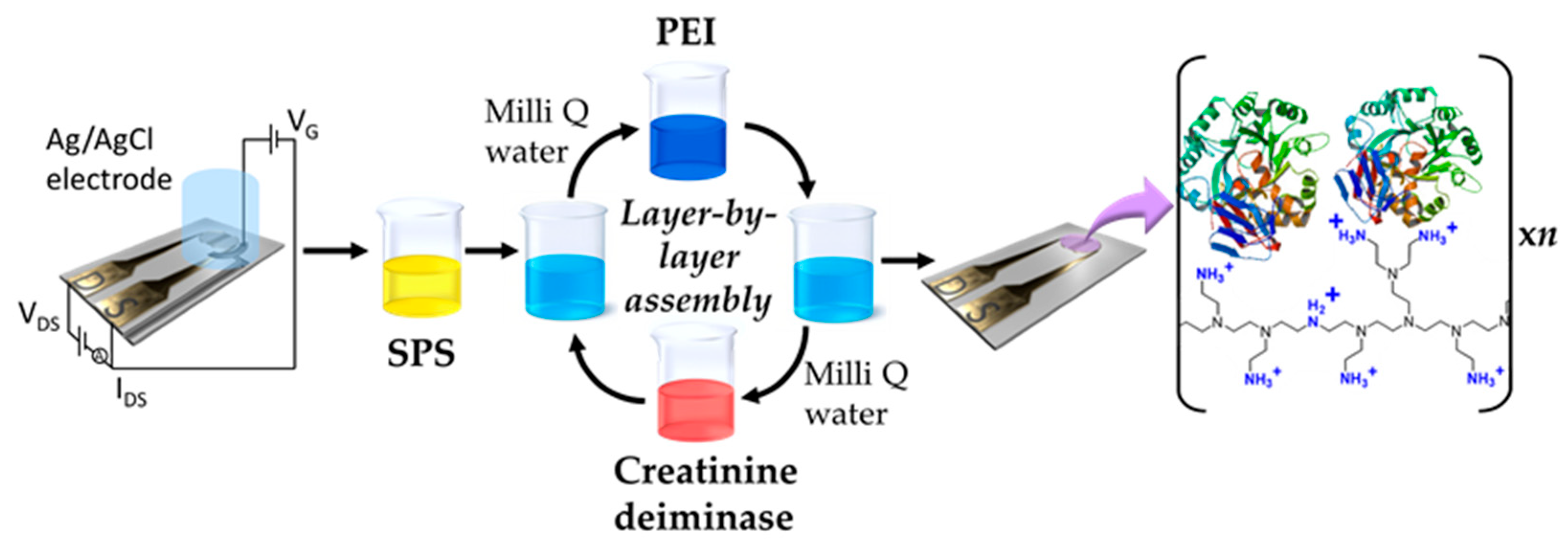

3.1. Construction of rGO FET Biosensors for Creatinine Detection

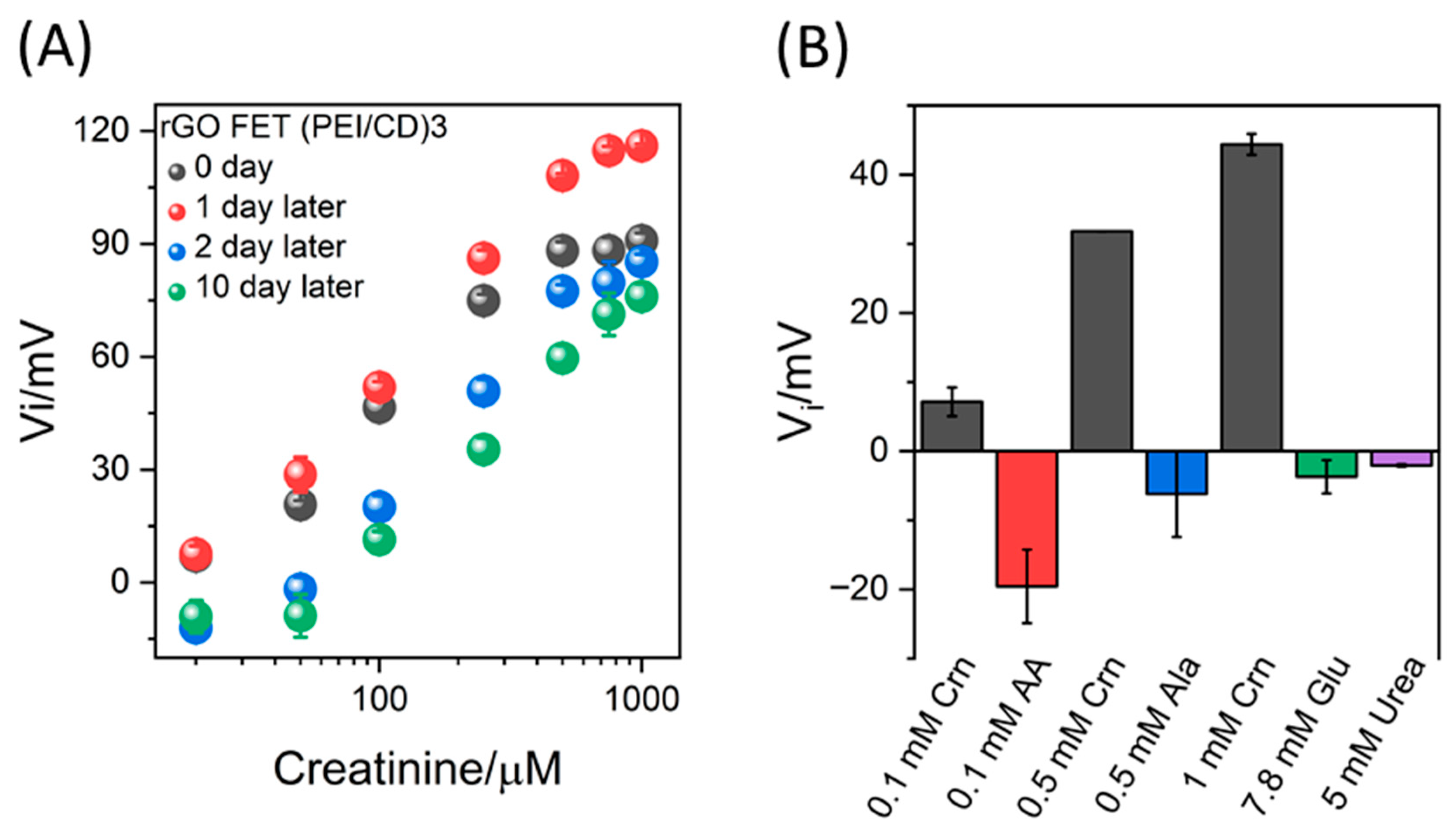

3.2. Reproducibility, Selectivity, and Stability

3.3. Incorporation of Protective Coating

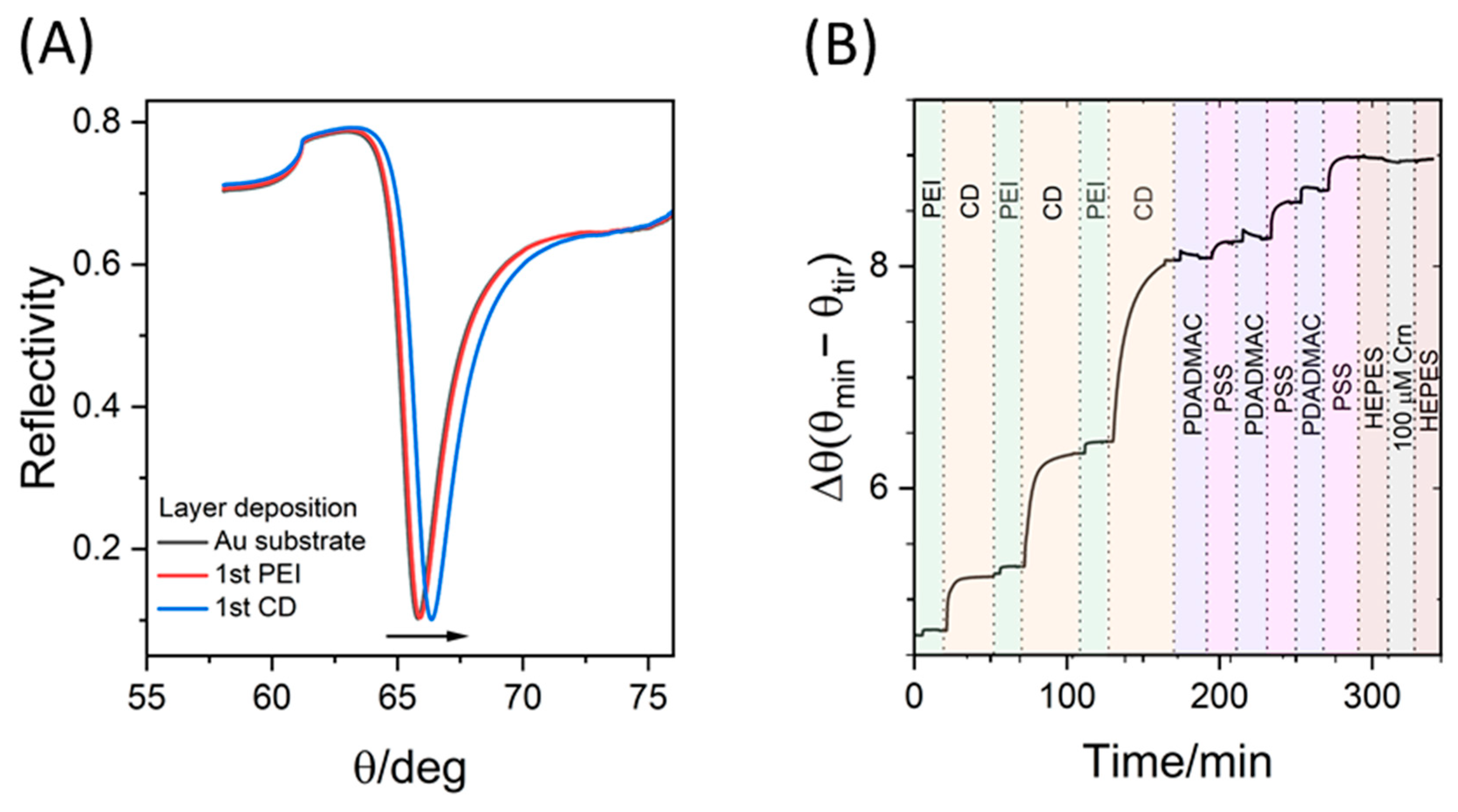

3.4. SPR Study of the Assemblies

3.5. Comparison with Other Creatinine Detection Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| rGO FETs | reduced graphene oxide-based field-effect transistors |

| CD | Creatinine deiminase |

| Crn | Creatinine |

| PEI | Poly(ethylenimine) |

| PDADMAC | Poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) |

| PSS | Poly(4-styrenesulfonate) sodium |

| SPR | Surface Plasmon Resonance |

References

- Augustin, S.M.; Deshpande, R.P.; Shanthaveeranna, G.K. To Compare Creatinine Estimation by Jaffe and Enzymatic Method. CHRISMED J. Health Res. 2022, 9, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, K.; Rosner, M.H.; Ostermann, M. Creatinine: From physiology to clinical application. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 72, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cánovas, R.; Cuartero, M.; Crespo, G.A. Modern creatinine (Bio)sensing: Challenges of point-of-care platforms. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 130, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, P.E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancıoğlu, R.; et al. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, A.C.; Nagler, E.V.; Morton, R.L.; Masson, P. Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet 2017, 389, 1238–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; He, W.; Aydin, Z. Determination of uric acid and creatinine in human urine using hydrophilic interaction chromatography. Talanta 2011, 83, 1707–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Li, M.; Jiang, Y.; Fang, X. Accurate quantification of creatinine in serum by coupling a measurement standard to extractive electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, M.J.; Cohen, A.; Hertz, H.S.; Ng, K.J.; Schaffer, R.; Van Der Lijn, P.; White, E. Determination of serum creatinine by isotope dilution mass spectrometry as a candidate definitive method. Anal. Chem. 1986, 58, 1681–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakesh Kumar, R.K.; Shaikh, M.O.; Chuang, C.-H. A review of recent advances in non-enzymatic electrochemical creatinine biosensing. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1183, 338748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Palmer, T. Clinical Analysis|Sarcosine, Creatine, and Creatinine. In Encyclopedia of Analytical Science; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Pundir, C.S.; Kumar, P.; Jaiwal, R. Biosensing methods for determination of creatinine: A review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 126, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syme, N.R.; Stevens, K.; Stirling, C.; McMillan, D.C.; Talwar, D. Clinical and Analytical Impact of Moving from Jaffe to Enzymatic Serum Creatinine Methodology. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2020, 5, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimohammadzadeh, E.; Hedley, J. Advances in Graphene Field Effect Transistors (FETs) for Amine Neurotransmitter Sensing. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cheng, B.; Zhang, Y. Room-Temperature Operable, Fully Recoverable Ethylene Gas Sensor via Pulsed Electric Field Modulation. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2500389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, I.-Y.; Kim, D.-J.; Jung, J.-H.; Yoon, O.J.; Nguyen Thanh, T.; Tran Quang, T.; Lee, N.-E. pH sensing characteristics and biosensing application of solution-gated reduced graphene oxide field-effect transistors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 45, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinini, E.; Fenoy, G.E.; Knoll, W.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Polyelectrolyte-Enzyme Assemblies Integrated into Graphene Field-Effect Transistors for Biosensing Applications. In Graphene Field-Effect Transistors; Azzaroni, O., Knoll, W., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Dong, S. Graphene nanosheet: Synthesis, molecular engineering, thin film, hybrids, and energy and analytical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jing, Q.; Ao, S.; Schneider, G.F.; Kireev, D.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, W. Ultrasensitive Field-Effect Biosensors Enabled by the Unique Electronic Properties of Graphene. Small 2020, 16, e1902820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinini, E.; Bliem, C.; Reiner-Rozman, C.; Battaglini, F.; Azzaroni, O.; Knoll, W. Enzyme-polyelectrolyte multilayer assemblies on reduced graphene oxide field-effect transistors for biosensing applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 92, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Park, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, K.S.; Hong, B.H.; Cho, K. Control of Graphene Field-Effect Transistors by Interfacial Hydrophobic Self-Assembled Monolayers. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 3460–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geim, A.K. Graphene: Status and Prospects. Science 2009, 324, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Jiang, L.; van Geest, E.P.; Lima, L.M.C.; Schneider, G.F. Sensing at the Surface of Graphene Field-Effect Transistors. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1603610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, G.; Lee, G.; Kim, M.J.; Baek, S.-H.; Choi, M.; Ku, K.B.; Lee, C.-S.; Jun, S.; Park, D.; Kim, H.G.; et al. Rapid Detection of COVID-19 Causative Virus (SARS-CoV-2) in Human Nasopharyngeal Swab Specimens Using Field-Effect Transistor-Based Biosensor. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 5135–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Her, J.-L.; Pan, T.-M.; Lin, W.-Y.; Wang, K.-S.; Li, L.-J. Label-free detection of alanine aminotransferase using a graphene field-effect biosensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 182, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Sohn, I.Y.; Jung, J.H.; Yoon, O.J.; Lee, N.E.; Park, J.S. Reduced graphene oxide field-effect transistor for label-free femtomolar protein detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 41, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohno, Y.; Maehashi, K.; Matsumoto, K. Chemical and biological sensing applications based on graphene field-effect transistors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 26, 1727–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, I.; Chatoor, S.; Männik, J.; Zevenbergen, M.A.G.; Dekker, C.; Lemay, S.G. Influence of electrolyte composition on liquid-gated carbon nanotube and graphene transistors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 17149–17156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvo, P.; Melai, B.; Calisi, N.; Paoletti, C.; Bellagambi, F.; Kirchhain, A.; Trivella, M.G.G.; Fuoco, R.; Di Francesco, F. Graphene-based devices for measuring pH. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 256, 976–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Mackin, C.; Weng, W.-H.; Zhu, J.; Luo, Y.; Luo, S.-X.L.; Lu, A.-Y.; Hempel, M.; McVay, E.; Kong, J.; et al. Integrated biosensor platform based on graphene transistor arrays for real-time high-accuracy ion sensing. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candia, M.L.; Piccinini, E.; Azzaroni, O.; Marmisollé, W.A. Digitalization of Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay with Graphene Field-Effect Transistors (G-ELISA) for Portable Ferritin Determination. Biosensors 2024, 14, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, R.A.; van Pelt, S. Enzyme immobilisation in biocatalysis: Why, what and how. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6223–6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasubramaniam, A.; Selhorst, R.; Alon, H.; Barnes, M.D.; Emrick, T.; Naveh, D. Combining 2D inorganic semiconductors and organic polymers at the frontier of the hard–soft materials interface. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 11158–11164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandanapalli, K.R.; Mudusu, D.; Lee, S. Functionalization of graphene layers and advancements in device applications. Carbon 2019, 152, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Caruso, F.; Dähne, L.; Decher, G.; De Geest, B.G.; Fan, J.; Feliu, N.; Gogotsi, Y.; Hammond, P.T.; Hersam, M.C.; et al. The Future of Layer-by-Layer Assembly: A Tribute to ACS Nano Associate Editor Helmuth Möhwald. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 6151–6169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisdat, F. Trends in the layer-by-layer assembly of redox proteins and enzymes in bioelectrochemistry. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2017, 5, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berninger, T.; Bliem, C.; Piccinini, E.; Azzaroni, O.; Knoll, W. Cascading reaction of arginase and urease on a graphene-based FET for ultrasensitive, real-time detection of arginine. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 115, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.; Xie, D.; Zhao, H.; Li, G.; Xu, J.; Ren, T.; Zhu, H. Tunable transport characteristics of p-type graphene field-effect transistors by poly(ethylene imine) overlayer. Carbon 2014, 77, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Parra, L.M.; Laucirica, G.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Marmisollé, W.; Azzaroni, O. Sensing creatinine in urine via the iontronic response of enzymatic single solid-state nanochannels. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 268, 116893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albesa, S.; Giménez, E.; Piccinini, J.M.; Vizoso-Pinto, M.G.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Piccinini, E.; Azzaroni, O. Machine Learning-Augmented Graphene Transistor Biosensing: Quantitative Platform Validation and Immunotesting of Hepatitis E. ACS Sens. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Jiménez, M.; Neyra Recky, J.R.; Azzaroni, O.; Scotto, J.; Marmisollé, W.A. Simultaneous Multiparameter Detection with Organic Electrochemical Transistors-Based Biosensors. Chemosensors 2025, 2025120526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenberg, E.; Persson, B.; Roos, H.; Urbaniczky, C. Quantitative determination of surface concentration of protein with surface plasmon resonance using radiolabeled proteins. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1991, 143, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Brown, P.H.; Schuck, P. On the Distribution of Protein Refractive Index Increments. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 2309–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinini, E.; Fenoy, G.E.; Cantillo, A.L.; Allegretto, J.A.; Scotto, J.; Piccinini, J.M.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Biofunctionalization of Graphene-Based FET Sensors through Heterobifunctional Nanoscaffolds: Technology Validation toward Rapid COVID-19 Diagnostics and Monitoring. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lv, J.; Yang, L.; Cui, Y. Advancements in Amperometric Biosensing Instruments for Creatinine Detection: A Critical Review. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 4006915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narimani, R.; Esmaeili, M.; Rasta, S.H.; Khosroshahi, H.T.; Mobed, A. Trend in creatinine determining methods: Conventional methods to molecular-based methods. Anal. Sci. Adv. 2021, 2, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parviz, D.; Das, S.; Ahmed, H.S.T.; Irin, F.; Bhattacharia, S.; Green, M.J. Dispersions of Non-Covalently Functionalized Graphene with Minimal Stabilizer. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 8857–8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virgen-Ortíz, J.J.; dos Santos, J.C.S.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Barbosa, O.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Polyethylenimine: A very useful ionic polymer in the design of immobilized enzyme biocatalysts. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 7461–7490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scouten, W.H.; Luong, J.H.T.; Stephenbrown, R.; Stephen Brown, R. Enzyme or protein immobilization techniques for applications in biosensor design. Trends Biotechnol. 1995, 13, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, E.M.; Hippe, H.; Patzke, F. Creatinine deiminase (EC 3.5.4.21) from bacterium BN11: Purification, properties and applicability in a serum/urine creatinine assay. Clin. Chim. Acta 1991, 204, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Rocha-Martin, J.; Moreno-Gamero, D. Enzyme immobilization strategies for the design of robust and efficient biocatalysts. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 35, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argaman, O.; Ben-Barak Zelas, Z.; Fishman, A.; Rytwo, G.; Radian, A. Immobilization of aldehyde dehydrogenase on montmorillonite using polyethyleneimine as a stabilization and bridging agent. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021, 212, 106216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Sudibya, H.G.; Yin, Z.; Wu, S.; Li, H.; Boey, F.; Huang, W.; Chen, P.; Zhang, H. Micropatterns of Reduced Graphene Oxide Films: Fabrication and Sensing Applications. Am. Chem. Soc. Nano 2010, 4, 3201–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Jańczewski, D.; Ma, Y.; Hempenius, M.; Xu, J.; Vancso, G.J. Disassembly of redox responsive poly(ferrocenylsilane) multilayers: The effect of blocking layers, supporting electrolyte and polyion molar mass. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 405, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, M.; Izquierdo, A.; Decher, G.; Voegel, J.-C.; Schaaf, P.; Ball, V. Layer by Layer Self-Assembled Polyelectrolyte Multilayers with Embedded Phospholipid Vesicles Obtained by Spraying: Integrity of the Vesicles. Langmuir 2005, 21, 7854–7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diforti, J.F.; Piccinini, E.; Allegretto, J.A.; von Bilderling, C.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Empowering Bioelectronics with Supramolecular Nanoarchitectonics: PEDOT-Based Organic Electrochemical Transistors with Tunable Electronic Properties. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 1211–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Jimenez, M.; Lugli-Arroyo, J.; Fenoy, G.E.; Piccinini, E.; Knoll, W.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Transduction of Amine–Phosphate Supramolecular Interactions and Biosensing of Acetylcholine through PEDOT-Polyamine Organic Electrochemical Transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 16, 61419–61427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.I.; Mukherjee, K.; Shoukat, R.; Dong, H. A review on pH sensitive materials for sensors and detection methods. Microsyst. Technol. 2017, 23, 4391–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.-H.; Lin, C.-F.; Juang, Y.-Z.; Wang, I.-L.; Lin, Y.-C.; Wang, R.-L.; Lin, H.-Y. Multiple type biosensors fabricated using the CMOS BioMEMS platform. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 144, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premanode, B.; Toumazou, C. A novel, low power biosensor for real time monitoring of creatinine and urea in peritoneal dialysis. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 120, 732–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busono, P. Development of Amperometric Biosensor for Creatinine Detection. In Proceedings of the 7th WACBE World Congress on Bioengineering 2015, Singapore, 6–8 July 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 52, pp. 134–137. ISBN 9783319194516. [Google Scholar]

- Marchenko, S.V.; Kucherenko, I.S.; Soldatkin, O.O.; Soldatkin, A.P. Potentiometric Biosensor System Based on Recombinant Urease and Creatinine Deiminase for Urea and Creatinine Determination in Blood Dialysate and Serum. Electroanalysis 2015, 27, 1699–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchenko, S.V.; Soldatkin, O.O.; Kasap, B.O.; Kurc, B.A.; Soldatkin, A.P.; Dzyadevych, S.V. Creatinine Deiminase Adsorption onto Silicalite-Modified pH-FET for Creation of New Creatinine-Sensitive Biosensor. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhoff, M.E.; Robins, R.H. Disposable Potentiometric Ammonia Gas Sensors for Estimation of Ammonia in Blood. Anal. Chem. 1980, 52, 2383–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, M. A Systematic Approach to Standard Addition Methods in Instrumental Analysis. J. Chem. Educ. 1980, 57, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diforti, J.F.; Cunningham, T.; Zegalo, Z.; Piccinini, E.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Piccinini, J.M.; Azzaroni, O. Transforming Renal Diagnosis: Graphene-Enhanced Lab-On-a-Chip for Multiplexed Kidney Biomarker Detection in Capillary Blood. Adv. Sens. Res. 2024, 3, 2400061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Diagnosis | Type of the Transistor | Immobilization Method | Enzymes | Linear/ Calibration Range | Sensitivity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecularly imprinted polymers | ISFET | EVAL/DMSO and creatinine on the ISFET | - | 12–500 µM | - | [58] |

| NH4+ sensitive | ISFET | Covalent | CA/CI/Urease | 0–20,000 µM | 55 mV/pH | [59] |

| H2O2 sensitive | AuNP/Calix arene | Covalent | CA/CI/SOx | 5–1000 µM | 65 mV/pA | [60] |

| pH-sensitive FETs | MOSFET | UV-photopolymerization | CD | 2–2000 µM | 40 mV/pH | [61] |

| pH-sensitive FETs | silicalite-coated pH-FET | Covalent | CD | 5–2000 µM | 40 mV/pH | [62] |

| pH-sensitive FETs | rGO FET | LbL | CD | 20–500 µM | 42.78 ± 4.07 mV/decade | this work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Candia, M.L.; Piccinini, E.; Azzaroni, O.; Marmisollé, W.A. Creatinine Sensing with Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based Field Effect Transistors. Chemosensors 2026, 14, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010003

Candia ML, Piccinini E, Azzaroni O, Marmisollé WA. Creatinine Sensing with Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based Field Effect Transistors. Chemosensors. 2026; 14(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleCandia, Melody L., Esteban Piccinini, Omar Azzaroni, and Waldemar A. Marmisollé. 2026. "Creatinine Sensing with Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based Field Effect Transistors" Chemosensors 14, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010003

APA StyleCandia, M. L., Piccinini, E., Azzaroni, O., & Marmisollé, W. A. (2026). Creatinine Sensing with Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based Field Effect Transistors. Chemosensors, 14(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010003